CHAPTER SIX

5th KOSBs clear Flushing’s New Town

Brigadier McLaren wanted to push ahead before it was light and the 5th KOSBs had deployed in the streets south of ‘Bexhill’ overnight. Lieutenant-Colonel William Turner’s men would cross the junction under cover of smoke and begin to clear the northern outskirts of the town. A Company, led by Major James Henderson, would cross first, tackling the houses lining Badhuisstraat codenamed ‘Cod’. C Company would follow, under Major Thomas Kennedy-Moffat, clearing ‘Grouse’, the maze of streets east of Badhuisstraat. B and D Companies could then advance into the streets east of Scheldestraat code named ‘Pike’ and ‘Partridge’ and the De Schelde Shipyard beyond. Lieutenant-Colonel Turner hoped to have cleared the whole area west of the Middelburg Canal by nightfall.

The supporting artillery opened fire from across the estuary at 4:45am, shelling the buildings north of ‘Bexhill’. As the 5th KOSB’s waited for zero hour, disaster struck the 4th Battalion; shells were falling short onto B Company and the Carrier Company. Although steps were taken to extend the range of the artillery, the 4th KOSBs suffered more than a dozen casualties before the message reached the gun crews. Meanwhile, the local underground leader had paid a visit to Lieutenant-Colonel Christian Melville. He protested that shells had fallen on St Joseph’s Hospital, setting the building on fire and further shelling of the area would endanger the hundreds of civilians sheltering inside. In spite of the risk, Melville sent the following uncompromising message back after conferring with his Brigade’s headquarters:

5th KOSBs objectives west of the Middelburg Canal

Unless the Germans surrendered unconditionally, we could take no responsibility for civilian casualties.

At 5:30am Second Lieutenant Malcolm Nisbet guided A Company of the 5th KOSBs across Coosje Buskenstraat under cover of smoke. Although ‘Dover’s guns had fired high, accurate mortar fire targeted Major Henderson’s men as they formed up along Badhuisstraat. Fourteen men were hit and in the chaos that followed, Second Lieutenant Nisbet was killed trying to rescue a wounded man. Despite the setback, Major Henderson managed to reorganise his company and before long, his men began clearing the houses along Badhuisstraat.

C Company had crossed Coosje Buskenstraat at the same time, under covering fire from 4 Commando machine-gun section. For a second time mortar shells accurately targeting the company forming up position, wounding more than a dozen men. Three officers, Major Thomas Kennedy-Moffat, the company CO, Lieutenant Eric Tullett of No 14 Platoon and Lieutenant E T Place of No 15 Platoon were among the injured. C Company’s senior able officer, Lieutenant George Carmichael, reorganised the survivors leading them into ‘Grouse’, working east from Hobeinstraat towards Scheldestraat. Lieutenant Carmichael was later awarded the Military Cross for taking command at a critical time in the battle.

As the advance continued, Captain Robin Marshall RA, witnessed twenty Germans taking cover in a pillbox near ‘Bexhill’. Realising that they could bring the junction under fire, Marshall ordered one of his gun teams forward. Sergeant Stewart Walker’s men wheeled their 3.7″ mountain gun behind a house overlooking the bunker and set about dismantling it. Piece by piece, some weighing up to 1/4 tonne, the gunners manhandled their equipment up the stairs, reassembling the gun in one of the bedrooms. After twenty minutes of hard work, the gun was ready and Walker gave the order to fire:

A 3.7″ Mountain Gun on Uncle Beach. Zeeland Library

The first bang brought the ceiling down on us and made us look like millers. Our second round hit two Germans who had decided to leave the fort at that precise moment and they were not seen again.

After eight shots had been fired, the outer wall of the house was in danger of collapsing and parts of the gun had gone through the floor. However, the pillbox had been destroyed; Sergeant Walker’s men had, for the time being, made Bexhill a little safer.

While A and C Companies battled on, their medics set about ferrying the wounded to safety. Dover pillbox was still firing on anyone crossing Coosje Buskenstraat so the Scots resorted to using their prisoners as stretcher-bearers. Soldiers often choose their own nick-names and Bexhill was known to many as ‘Hellfire Corner’.

As the 5th KOSBs fought their way though the northern outskirts of the town, the commander of the 4th KOSBs had other pressing matters to deal with. Lieutenant-Colonel Michael Melville needed to evacuate the civilians from St Joseph’s Hospital before the 5th Battalion reached it. Brigadier McLaren wanted the civilians to leave via the dockyards and be taken to a safe area east of Uncle Beach. A Company of the 4th KOSBs soon found themselves overwhelmed shepherding hundreds of civilians to safety. At the same time they were forced to guard a number of Germans, eager to surrender. As the civilians made their way through the dockyard, snipers fired into the crowd from the tops of the cranes. In response, Lieutenant-Colonel Melville called forward a number of 3.7″ mountain guns. Firing directly at their high targets, in what some described as a ‘rook shoot’, the gunners dealt with the snipers one by one.

Civilians make their way to Uncle Beach, ready to be evacuated. IWM BU1263

Prisoners gather on the seafront. Zeeland Library

By 11:00 am ‘Grouse’ was clear and B and D Companies crossed over Bexhill making for their start line. Shortly after noon Major David Haig and Major David MacDonald ordered their men across Scheldestraat to begin clearing ‘Pike’ and ‘Partridge’. Throughout the afternoon the 5th KOSBs made slow progress, gradually clearing block after block. ‘Pike’ and ‘Partridge’ were reported clear at 2:00 pm and B and D Companies continued east into the huge machine-shops and carpenters sheds on the north side of the dock. Many Germans had withdrawn during the morning with civilians, but some remained behind determined to fight on. Under accurate mortar and machine-gun fire, the Scots winkled out the German strong points and by 5:00 pm the factory was reported to be safe.

Finally, A Company reported that ‘Cod’ had been cleared; it meant that the 5th KOSBs held the entire area west of the Middelburg canal. For the loss of only thirty-seven casualties, Lieutenant-Colonel Turner’s men had taken all their objectives.

4 Commando’s Battle for ‘Dover’

While the 5th KOSBs tackled the New Town, 4 Commando still faced stiff opposition along the seafront. Commandant Phillipe Kieffer MC had taken over responsibility for the area codenamed ‘Eastbourne’ overnight, forming a strong cordon behind the sea front promenade with three troops. The plan was to attack at first light, clearing several strong points along the Boulevard de Ruyter.

Captain Thorburn’s Troop attacked as the first streaks of grey appeared in the sky, working methodically through ‘Hove’, a German naval barracks. They advanced quickly and it appeared that the main garrison had fled overnight leaving behind a handful of medics to care for the wounded. A few hundred metres north, the rest of the troop entered the bombproof barracks known as ‘Worthing’. They, too, found their objective empty except for a few wounded.

Detailed map of the area surrounding Dover strongpoint.

Street fighting proved to be dangerous and frustrating. IWM B11634

No 1 Troop’s advance across Boulevard de Ruyter had alerted the Germans manning ‘Dover’ pillbox and its machine-guns could sweep the full length of the sea front. Heavy fire prevented Captain Thorburn’s troops reaching the bombproof tower next to ‘Worthing’ and for the present time progress along Boulevard de Ruyter was at a standstill.

During the search that followed the commandos discovered a stash of documents and papers, including Colonel Reinhardt’s intelligence log. It gave an interesting insight into the state of German morale in Flushing. One entry noted that Colonel Reinhardt issued an arrest warrant against an anti-tank platoon commander after he had withdrawn his men from their positions ‘in spite of repeated official warnings that this on no account be done’. The papers also detailed unit strengths, reporting that 1019th Grenadier Regiment’s companies were below half strength.

As No 1 Troop fought its way along the seafront, Commandant Kieffer had taken steps to engage ‘Dover’ from another direction. At 7:00 am No 5 Troop began to work its way along Coosje Buskenstraat. By breaking holes through the garden walls, a technique known as ‘mouse-holing’, Captain Alexandre Lofi’s men advanced unseen towards ‘Dover’. Progress was painfully slow, however, one section eventually stationed a PIAT team on the roof of a cinema, overlooking the strong point. As they drew closer to their objective Captain Lofi ordered No 1 Section to cross over Coosje Buskenstraat and under heavy fire his men made the suicidal run. Now it was possible for both sections to advance under cover to within assaulting distance.

However, as the commandos prepared to assault the pillbox, they were ordered to withdraw; Battalion headquarters had managed to obtain air support. From a safe distance the commandos watched in awe as the Typhoons swept in over the sea, targeting ‘Dover’ with their rockets and cannons.

No 5 Troop resumed its advance on ‘Dover’ in the afternoon taking up positions overlooking the end of Boulevard Bankert. A furious gun battle followed, and before long a group of Germans evacuated the house next to ‘Dover’ pillbox. Many were shot down as they ran down the street towards the Grand Hotel Britannia. No 1 Section moved forward next, taking cover behind an anti-tank wall at the end of Coosje Buskenstraat. Although the wall had been built to stop vehicles entering the town, it now provided useful cover for the commandos’ PIAT team. The final suicidal dash involved placing a ‘made-up charge’ against the door of the bunker:

Flushing seafront, devastated during the attack on ‘Dover’.

Corporal Lapont volunteered to carry out this hazardous task. Just as he was about to dash forward, a white flag appeared from the embrasure, and the battle for DOVER had been won.

Captain Lofi’s men warily entered the strong point and found three officers and fifty-four men, many of them wounded.

As the prisoners were escorted from the pillbox, heavy fire along the seafront temporarily panicked the senior German officer, but as the danger passed the commandos were amused by an arrogant request:

The Company Commander himself, although slightly wounded and badly shaken, soon recovered the typical brand of self-assertiveness and arrogance and demanded an escort to take him back to DOVER for his best trousers and his service dress.

Not surprisingly, the commandos had seen and heard enough over the course of the day, to refuse the request. During the battle Captain Lofi’s men had been surprised to discover a member of No 6 Troop, cut off since the previous morning. While he hid, the commando witnessed a barbaric act:

The Germans had re-entered this house after our troops left it, and, finding British equipment lying in it, had taken the entire family who lived there outside and shot them in cold blood.

It had been a stern reminder that there were still fanatical elements at large in the town.

The Nolle Gap

With ‘Dover’ clear, No 4 Commando had secured the sea front and made ‘Bexhill’ crossroads safe to cross. There was, however, little time to rest. As the commandos prepared to hand over their sector to the 7/9th Royal Scots, new orders came through from Brigade. Brigadier McLaren instructed Lieutenant-Colonel Dawson to prepare to move to the northern outskirts of the town.

It was known that the rest of 4 Special Service Brigade was moving rapidly south along the dunes. 47 Commando was approaching Dishoek, only two miles from Flushing, but they still faced a number of coastal batteries. Brigadier Leicester wanted assistance, if 4 Commando could advance north west along the coast, they could attack the German strong points from an unexpected direction.

The plan involved 4 Commando crossing the Nolle Gap, one of the breaches in the dike, north of the town. The gap posed many problems, huge slabs of concrete and broken beach obstacles left over from the bombing littered the gap. At low tide the channel was a torrent of fast flowing water, far too strong for the Buffaloes. It was hoped the current would subside at high tide allowing the LVTs to swim over the debris.

Lieutenant-Colonel Dawson did not receive the order to withdraw and reform until late and in the maze of ruined streets, platoon and section commanders struggled to assemble their men together. 4 Commando’s report despairs over the situation:

It was, of course, dark long before the order to withdraw could be sent out, and there were no facilities for briefing troops, and no time even for the normal careful check of weapons. Eventually we had to contemplate the unpleasant prospect of priming grenades by moonlight in the LVT whilst ploughing through a rather choppy sea.

Lieutenant-Colonel Dawson was completely against the operation, acutely aware that his men were tired and hungry. He was also concerned by the shortage of small arms ammunition.

As high tide approached 4 Commando gathered in Gravestraat alongside a line of waiting Buffaloes. With trepidation the men waited for the order to mount up, while their officers worked frantically to cobble a plan together. However, at the last moment the operation was postponed; 4 Commando’s report sums up the episode:

The inability of the artillery to co-operate on this occasion gave the coup-de-grace to a plan which could only have succeeded if all the Gods had been whole-heartedly with us… In this manner a remarkable and somewhat inexplicable incident was satisfactorily terminated.

Commandos study the Nolle Gap. Zeeland Library

Troops of 4 Commando make their way along Coosje Buskenstraat H Houterman

At long last, No 4 Commando was able to have a well-earned rest. Their speed and tenacity during the clearing of Flushing had prevented the loss of many lives, both soldiers and civilians.

The 7/9th Royal Scots attack on the Grand Hotel Britannia

As D+1 drew to a close, Lieutenant-Colonel Michael Melvill, the commanding officer of the 7/9th Royal Scots, was called into Brigadier McLaren’s headquarters where he was given orders to capture the Grand Hotel Britannia on the western outskirts of the town. The hotel was suspected of housing the headquarters of the Flushing garrison and the Royal Scots were expected to attack it while 4 Commando made its way to the Noelle Gap. Even though the commando’s operation was cancelled at the last minute, McLaren still wanted the German headquarters cleared.

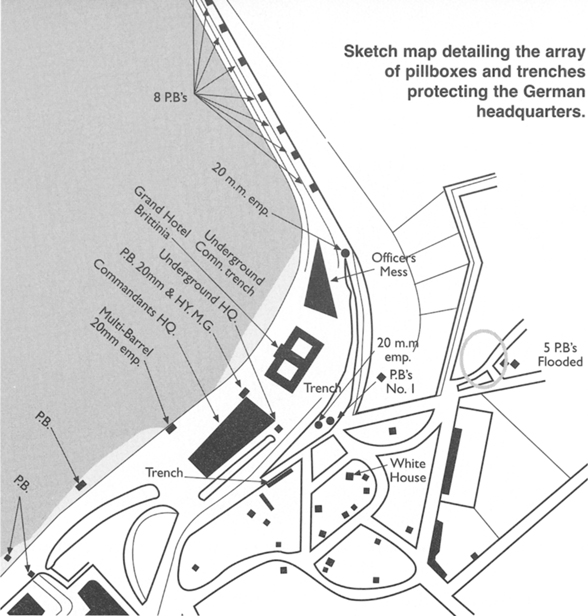

The hotel stood on a wide embankment, forming part of the sea wall and although the position was protected by a maze of trenches and bunkers, the garrison had been estimated at no more than fifty men. A frontal approach, along the Boulevard de Bankert, had been ruled out as too dangerous. Fortified hotels and pillboxes covered the sea front and after the experiences with ‘Dover’, McLaren was sure that the cornered Germans would fight to the last. The plan was to approach from the rear, in the hope of taking the garrison by surprise.

The approach to the Grand Hotel Britannia, the flooding extended as far east as the water tower.

At first Lieutenant-Colonel Melvill instructed D Company, under Major Arnaud Chater, to make the attack. As a precaution, Major Hugh Rose’s B Company was added later in case there were more Germans than expected. C Company, under Captain Gordon Thomson, and half the Carrier platoon, under Captain Kenneth Buchanan, also joined the assault force to provide supporting fire. It was a fortunate afterthought; the Germans were not the only ones in for a surprise. The approach to the hotel would involve wading through floodwaters of unknown depth and Melvill arranged for ‘Mae West’ lifejackets. For troops who had spent months training for mountain warfare, their first battle was going to be an unforgettable experience.

At 1:45 am the Royal Scots set off through the darkened streets and as they passed warily down Badhuisstraat, fires cast an eerie glow across the town. Making their way forward, the Scots were dismayed to feel cold water splashing over the tops of their boots, the floodwater had risen far higher than expected. In front they could just make out a huge lake of sea water.

As the lead company approached a dangerous bottleneck, the bridge over the Waterweg canal, shots rang out, wounding several men. A machine-gun post stationed in the water tower overlooking the bridge barred the way forward. As men dived for cover and returned fire, others dealt with the wounded. One of the injured, CSM John Young, was in danger of being swept away by the floodwater until Private Andrews came to the rescue.

While the stretcher bearers went to work, Major Rose sent Sergeant Sandy’s section forward to deal with the Germans holding the tower. They quickly stormed the water tower and before long seven prisoners were being escorted to the rear. Although one problem had been dealt with, the Royal Scots faced another danger as shells began crashing down on their positions. They appeared to be part of the supporting barrage, however, problems with the radio sets meant that there was no way of contacting the artillery. All the men could do was find cover in doorways and wait for the barrage to end but as the minutes ticked by the casualties began to mount. and by the time the shelling ceased, a large number, including over half the Carrier platoon, had been wounded.

Aerial view of the seafront after the battle, the Royal Scots approached the hotel from the right. H Houterman

The barrage eventually came to an end at 3:15am and leaving the Battalion MO, Captain Peter Clothier, and the padre, Rev James Wood, behind to evacuate the wounded, Melvill decided to push on. By now the water level has risen to alarming depths and before long the men were waist deep in freezing cold sea water. The men did their best to move forward, carrying their equipment above their heads, but progress was slow. Eventually the water rose up to the men’s armpits, making it difficult to keep their balance. Holding arm in arm, those with heavier weapons had to be steadied by others in the chain. Occasionally a man would slip and disappear briefly beneath the water, before his comrades rescued him.

While his men edged closer to the objective, Lieutenant-Colonel Melvill established his tactical headquarters on Vrijdomweg. Soon afterwards he received a strange request from B Company; a request that nearly led to disaster:

Major Rose asked for permission to work forward to find a shallower FUP [forming up point]. In doing so, the Battalion ‘Snake’ formation found themselves almost on to their objective, and ‘asked for permission to assault now’. This was agreed to by Colonel Melvill and instructed that all command ‘tie-up’ at this point and organise the assault forward.

Rose’s company had stumbled onto a pillbox covering the rear of the hotel in the darkness. With no time or space to manoeuvre, Lieutenant Joseph Cameron’s Platoon attacked the bunker with ‘tremendous cheers and cries of “Up the Royals”’, while the Carrier Platoon gave supporting fire. Although the pillbox was taken, the rattle of machine-guns and rifles had aroused the main garrison in the hotel.

As Cameron’s men took thirty-six dazed prisoners in the bunker, a number of machine-guns and four-barrelled flak cannon opened fire. The flak cannon was sited on the roof of the German headquarters and it possessed a commanding view of the area. Although many of the Royal Scots ran forward, taking shelter at the foot of a steep embankment behind the hotel, the tail end of B Company, were caught in the open and had to fall back. They took cover in a nearby house, disturbing the German occupants. After driving off the counter-attack with his Bren gun, Corporal Chisholm led the sections across to the embankment to rejoin the rest of the company.

The German view of the Royal Scots approach to the hotel, the area was flooded during the attack. H Houterman

The Royal Scots were now in a predicament. Although they were hidden from view while they stayed at the foot of the embankment, any move forwards or backwards would bring them under fire. Pillboxes, linked by a trench covered the top of the slope, blocking the way forward. Major Rose tried to find a way to outflank the headquarters, but his search proved fruitless; snipers and machine-guns covered every approach to the hotel.

Having no other options, Major Rose and Major Chater decided to rush the back door of the hotel, in the hope of getting some men inside. After targeting a door with PIAT shells, Lieutenant Harold George led a dozen men across to the building through the gauntlet of bullets while the rest of B Company provided covering fire. After breaking through the damaged door, George’s party began to explore the ground floor of the hotel. After a nerve-racking search it became apparent that the Germans had withdrawn to the upper floors. Having established a foothold in the hotel, Major Rose decided to send more troops across to reinforce Lieutenant George. Following a pre-arranged signal, Lieutenant Cameron’s platoon made the mad dash across the driveway while the rest of the Royal Scots targeted the roof of the hotel.

Sketch map detailing the array of pillboxes and trenches protecting the German headquarters.

While the search of the hotel continued, the Germans had recovered sufficiently to make a counter-attack. As Major Rose and Major Chater waited on the embankment for news from the hotel, the Germans made several attempts to drive the Scots from their precarious position. One party established themselves in a house overlooking the embankment [labelled the White House on the map], bringing the Royal Scots under fire. Meanwhile, a determined counter-attack from the north almost overran Lieutenant John Widdowson’s platoon. Even Lieutenant-Colonel Melvill’s headquarters came under attack from a hidden sniper.

As he relocated his headquarters under cover of smoke, Melvill was rapidly coming to the conclusion that he faced far more than fifty Germans. He realised that he was greatly outnumbered and in danger of being overrun. As soon as it became light the Germans would be able to drive his men from the embankment, leaving the Hotel Britannia firmly in German hands. The Battalion war diary sums up the Royal Scots predicament:

Fire devastated the Grand Hotel Britannia. H Houterman

20mm in such a position that it completely dominated the situation, and was not approachable. Two platoons in the hotel, which was burning furiously. Ammunition short. Enemy in considerable strength. Only communication to Bde HQ via Gunner 22 set. Casualties - appeared to be very high.

In the absence of a radio link, Melvill sent Lieutenant Joseph Brown, the intelligence officer, back to Brigade headquarters. He was to request assistance and arrange for the re-supply of ammunition. Once at Brigade HQ, McLaren made it clear to Lieutenant Brown that the Royal Scots must immediately pull back from the area around the hotel. Typhoons would be called in to deal with the flak cannon once the Scots had withdrawn. In the meantime, McLaren would arrange reinforcements for a larger attack.

However, as Lieutenant Brown returned to his Battalion headquarters, the situation at the hotel had taken a new turn. As it began to get light, Major Rose and Major Chater were increasingly concerned by the lack of contact with the men in the hotel. Although shots had been heard, no one knew if Lieutenant George and Lieutenant Cameron were still active. Smoke and flames from the hotel windows indicated that the hotel was well alight and before long the building would have to be evacuated.

Captain Thomson ordered Lieutenant Beveridge’s platoon forward to reinforce B Company on the embankment but he soon found his position under fire. With Major Rose’s permission, Beveridge led his men across to the hotel to join the men inside. Major Chater followed in the hope of joining his men but he was killed as soon as he broke cover; Thomson was also fatally wounded as he made the dash to the hotel.

Meanwhile, C Company had completed its search of the hotel and although they had cleared the first two floors, steel reinforced doors prevented access to the roof where German snipers were still holding out. With the building ablaze and no way onto the roof the three Lieutenants, George, Cameron and Beveridge, were forced to evacuate. As they left the building, Lieutenant George spotted a machine-gun team moving its weapon onto the embankment. Realising the imminent danger, George rushed the three-man team, shooting them down with his pistol.

The Scots found themselves trapped. The flak cannon on the roof of the building next to the Grand Hotel Britannia covered the rear of the burning building, making it impossible to reach the embankment. Not to be deterred, Lieutenant Beveridge began to scale the outer wall of the building. By clinging to drainpipes and window ledges, he climbed several floors before scrambling onto the roof. The startled flak gun crew ran to safety as the officer threw himself over the parapet. It seemed that nothing could stop the determined Scots.

With the main threat to his platoon eliminated, Beveridge returned to his men and they set about clearing the pillboxes behind the hotel. As Lieutenants Beveridge and Cameron fought their way through the trenches, they stumbled on the entrance to an underground bunker. After shooting the sentry the two officers broke down the door and once inside they were astonished to find dozens of Germans seeking refuge from the fighting. They had stumbled across the main German command centre. The headquarters staff of 1019th Regiment, including its commander, Oberst Eugen Reinhardt, and 130 officers and men surrendered to the surprised Scots.

Oberst Reinhardt considers his future in captivity

While the battle continued at the hotel, Lieutenant-Colonel Melvill was anxious to discover the truth about his Battalion’s position. After climbing out of upper storey window and shinning down a rope, Melvill managed to escape the notice of the German snipers targeting his headquarters. As he made his way towards the hotel, Lieutenant-Colonel Melvill could see Major Rose’s men pinned to the embankment. Ignoring warnings to take cover, Melvill waded forward through the receding floodwater to join his men. He was soon spotted and a burst of machine-gun fire wounded the CO and killed his signaller. Unable to move, Lieutenant-Colonel Melvill lay in the floodwater and with his cries of ‘On the Royal’s’ ringing in their ears, the incensed Scots charged over the top of the embankment. In Major Rose’s words:

When we saw the CO drop, we went hot with rage. Every Jock on that embankment was out to avenge him.

Lieutenant Widdowson led the assault on the officers’ mess, north of the hotel, hurling grenades into pillboxes and through windows, while C Company cleared the buildings along to the south. In the face of this furious onslaught, the Germans around the hotel soon capitulated.

With Oberst Reinhardt’s assistance, a cease-fire was arranged and Lieutenant-Colonel Melvill watched in amazement as his men rounded up their prisoners. Six hundred dazed Germans eventually surrendered; it was rather more than the fifty men quoted in the original orders. Another fifty were found lying dead in their bunkers.

The battle had cost the Royal Scots dearly; over twenty had been killed and dozens more had been wounded. Major Hugh Rose was awarded the Distinguished Service Order for leading the battle, while Lieutenant Joe Cameron received the Military Cross for his part in clearing the hotel.