Chapter 2

Before Rome could unite Italy or create a Mediterranean-wide empire, the primitive villages from which it grew had to become a city and a state. The emergence in Italy of complex urban communities and organized states must be seen in the context of developments that began with the collapse of high Bronze Age civilizations in the eastern Mediterranean and the Aegean between 1200 and 1000 b.c.e. The first important developments took place on the coast of the Levant in several commercial cities inhabited by people known in English as the Phoenicians. They carried on much of what post-collapse trade remained in the eastern Mediterranean world. As peace and stability returned between 1000 and 800 b.c.e., an increase in population and commerce promoted the growth and spread of complex urban societies. They appeared among the Phoenicians first and then the Greeks, who were heavily influenced by contact with the Phoenicians and other Near Eastern people between 800 and 600 b.c.e.

By 800 b.c.e., Phoenician traders looking for metals like silver, copper, lead, tin, and iron were active along the west coast of Italy. They found significant sources in Etruria and on the island of Elba (Ilva). Greek traders soon joined the Phoenicians. Not long afterward, Greek settlers established numerous colonies in southern Italy and Sicily. Both the Phoenicians and the Greeks brought the native peoples of Italy into contact with the advanced cultures and economies of the eastern Mediterranean. That contact stimulated the growth of correspondingly complex societies in Italy, particularly in Etruria, Latium, and Campania. Its impact was strongest on those who inhabited the region of Etruria and came to be known in English as Etruscans.

The Phoenicians

The Phoenicians were those whom the Greeks called Phoinikes and the Romans called Poeni. From the noun Poeni comes the Latin adjective Punicus (Punic) in reference to the Phoenicians who settled Carthage. They were descendants of the Canaanites described in the Hebrew Bible. During the second millennium b.c.e., the Canaanites inhabited the Syro-Palestinian coast of the Levant. It stretched from just above the city of Ugarit to the Egyptian frontier in the South, near the city of Gaza (see map, p. 17). The Canaanites spoke one of the Semitic languages, which include ancient Akkadian, Assyrian, and Amorite (Babylonian); biblical and modern Hebrew; and Arabic. Just as Indo-European and Indo-European-speaking people are cultural and linguistic terms with no biological or racial significance, so are Semitic and Semitic-speaking people. They merely indicate people who speak one of a number of linguistically similar languages.

Under Egyptian hegemony from 1900 to 1200 b.c.e., Canaanite ports prospered as vital entrepôts. They linked together Egypt, Crete, Cyprus, Mycenaean Greece, Anatolia, Syria–Palestine, and Mesopotamia in a vast network of international trade. Between 1500 and 1100 b.c.e., Canaanite traders benefited from the creation of a purely alphabetic form of writing instead of the cumbersome Egyptian hieroglyphic and Mesopotamian cuneiform writing systems. The Canaanite system was based on twenty-two consonantal signs. The names of the first two signs, aleph (alpha in Greek) and bayt or bet (beta in Greek), are the roots of the word alphabet. After the collapse of the Bronze Age in the eastern Mediterranean ca. 1200 b.c.e., the Canaanites’ Phoenician descendants continued to write in what is now called the Phoenician alphabet. By the eighth century b.c.e., the Greeks had borrowed that alphabet and made certain modifications to represent vowels. This modified Phoenician alphabet, in turn, became the basis of all subsequent Western alphabets, including Rome’s.

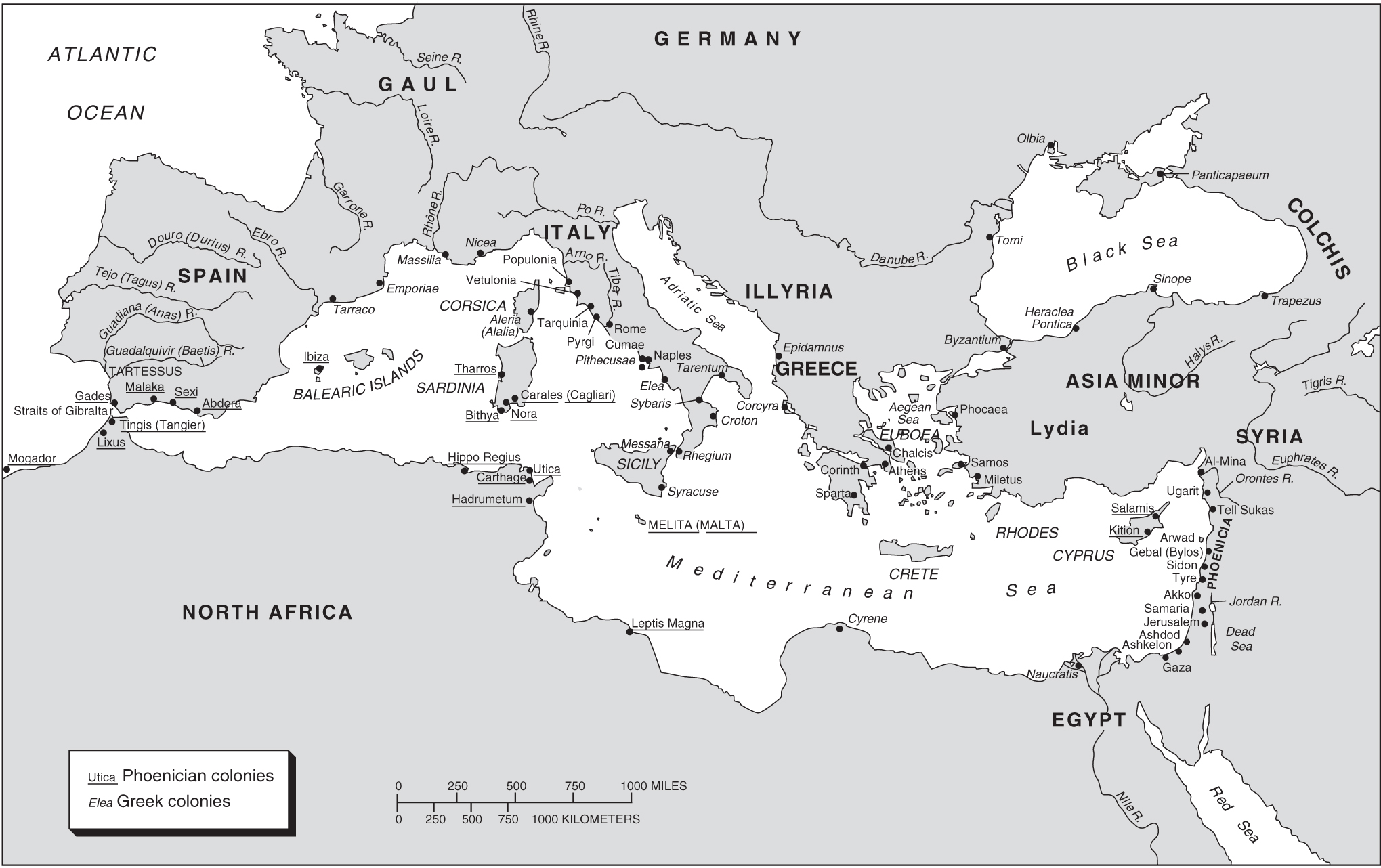

FIGURE 2.1 The Mediterranean, ca. 600 b.c.e.

The cities identified as Phoenician occupied that part of old Canaanite territory roughly equal to modern Lebanon. They included Byblos, Sidon, and Tyre. Hemmed in by the Aramaeans, Israelites, and Philistines, the Phoenicians had little choice but to exploit their narrow hinterland and the sea. The fertile, well-watered river valleys provided enough food to sustain a critical mass of urban residents in the early part of the first millennium b.c.e. The mountains provided great forests of cedar, pine, and cypress for building ships and supplying foreign markets with timber. They also contained increasingly valuable deposits of iron, which the Phoenicians used to make ships’ fittings or traded for other goods. The sea yielded fish that could be eaten or salted and exchanged in trade. The most valuable sea creature was the murex, a shellfish that secretes a purple dye when left to ferment in the sun. The Phoenicians used this dye to create expensive purple cloth. It was so eagerly sought as a mark of high status that it became the symbol of luxury and royalty throughout the ancient World and continues to be so today.

Phoenician ships brought back raw materials like cloth, leather, lead, copper, tin, silver, gold, glass, ebony, and ivory. Skilled craftsmen turned them into luxury goods. Those goods, as well as slaves acquired by purchase or capture, could be exchanged for food and more raw materials to support growing populations and thriving workshops. The products of these workshops reflected the styles and tastes of the customers in their biggest markets, Egypt and Mesopotamia. They eventually inspired the “Orientalizing Period” in the art of the Greeks and Etruscans, with whom the Phoenicians also traded.

Tyre and its colonies

By the early ninth century b.c.e., the Phoenician city of Tyre had emerged as the head of a combined kingdom of Sidon and Tyre and came to dominate the rest of the Phoenician cities. Tyre’s location—just offshore on a small island—rendered it practically impregnable. Diplomacy and the establishment of commercial enclaves and trading posts during the ninth century made it powerful. First, Tyre gained control of trade in metals and slaves in much of the Near East. Then it exploited new sources of supply in Italy, Spain, and elsewhere in the western Mediterranean. These western sources became particularly important late in the ninth century as the struggles between the Aramaeans and the expanding Assyrian Empire blocked Tyre’s access to metals from lands farther east.

To compensate, Tyre began establishing strategic Phoenician outposts to reinforce its maritime access to metals and to open up new sources in the West. It strengthened its position on the island of Cyprus, from which Near Eastern people had obtained copper for centuries. Tyre founded Citium (Kition) on the southeastern part of the island and established firm control over its valuable copper deposits. Tyrian colonies in the western Mediterranean opened up and controlled access to the rich metallic ores of Italy, Sardinia, Spain, and Morocco. Probably the oldest ones were Gadir (Gades, Cadiz), on the Atlantic coast of Spain just north of the Straits of Gibraltar; Lixus, south of the Straits on the Atlantic coast of Morocco; and Utica, in North Africa on the northwest shore of the Gulf of Tunis. During the eighth century b.c.e., a dense pattern of Phoenician settlements appeared on the south coast of Sardinia at sites such as Sulcis, Bithia, Nora, and Cagliari. Phoenicians also occupied Motya, Panormus (Palermo), and Solus (Solunto) on the western end of Sicily and the small island of Melita (Malta), between Sicily and North Africa.

The greatest of Tyre’s colonies in the West was Carthage. The traditional date of its foundation is 814/813 b.c.e., but 750 b.c.e. has more archaeological support. Carthage was situated in North Africa just west of Cape Bon, at the head of the Gulf of Tunis. It had a fertile hinterland that supported a large population and produced surplus grain for trade. Its deep, well-protected harbors provided a safe halfway stop for ships bringing gold, silver, copper, and tin from Gades and other Atlantic ports back to Tyre. Carthage’s own ships could easily trade with the rest of the western Mediterranean basin and block Tyre’s competitors from entering through the narrow waters between North Africa and Sicily. Indeed, when Tyre went into decline after incurring the active hostility of Assyria and Babylon in the seventh century b.c.e., Carthage took control of Tyre’s western colonies and trade. It became the primary competitor of first the Greeks and Etruscans and then the Romans for domination in the West for over 250 years.

Earlier, Phoenician traders and merchants had brought increased economic activity and the influences of the advanced Near Eastern cultures to the western coast of Italy. They were searching for metals and slaves in return for wine, olive oil, and manufactured products. Thus, they helped to stimulate the growth of wealthy social elites and complex urban centers in Etruria, Latium, and Campania in the eighth and seventh centuries b.c.e. Under the leadership of Carthage in the sixth century, the Poeni, the Phoenicians’ Punic descendants, even occupied trading posts on the coast of Etruria and established close relations with the Romans. The Greeks, of course, eventually surpassed the Phoenicians in terms of influence on Rome, but the Phoenician role in shaping the world that produced Rome and that Rome eventually took over should not be ignored.

Greek colonization

About 825 b.c.e., Greeks from the island of Euboea took up residence beside Phoenician and other traders at the Syrian port of Al Mina, near the mouth of the Orontes River. Around 770–750 b.c.e., Euboean Greeks even established a commercial outpost on the island of Pithecusae (Ischia, Aenaria) off the coast of Italy in the Bay of Naples. Perhaps the Euboeans were even advised by Phoenician colleagues. A Phoenician presence at Pithecusae is supported by graves, pottery, and other artifacts excavated from the early settlement.

About a generation later, knowledge gained from Phoenician and Greek traders familiar with Italy and Sicily pointed the way for a flood of permanent Greek settlers. They hoped to gain strategic commercial outposts and find relief from a growing shortage of agricultural land and associated problems in their home cities. The colonists usually maintained sentimental, religious, and commercial ties with their mother cities. Still, each new colony became a completely independent city-state just like the autonomous mother cities in the Greek homeland. Therefore, the same divisiveness and lack of unity that characterized the mother cities also characterized their colonies.

Greek colonies in Italy

The chief sponsor of the Greek settlement of Pithecusae was the Euboean city of Chalcis. Its name means “copper” in Greek. It was a center of metalworking and had been trading and working with Phoenician merchants and metalworkers for over a century. The island of Pithecusae gave the first Greek settlers access to Italy’s copper and a safe place to live. Along with the Chalcidians came some people from Eretria and two other neighboring Euboean towns, Cumae and Graia. A generation later, some Pithecusans, probably joined by newcomers from Euboea, moved across to the Italian mainland. They established Cumae, named for the town of Cumae in Euboea. Later, a little farther east on the bay, they founded a separate port town. When they outgrew those two places, they established another city, Naples (Neapolis, “New City”), to handle the overflow.

All of these towns left their marks on the Romans. It is probable that from Cumae, either directly or through Etruscan intermediaries, the Romans derived the Latin alphabet, in which the words of this book are written. Through Cumae, many Greek gods became familiar to neighboring Italic tribes—Herakles (Hercules), Apollo, Castor, and Polyduces (Pollux), for example. The oracle of the Sibyl at Cumae won great renown, and a collection of her supposed sayings, the Sibylline Books, was consulted for guidance at numerous crises in Roman history.

Although the Greeks called themselves Hellenes, the Romans called them Greeks, after the Graians (Graioi, Graei), whom they first met among Euboean settlements around the Bay of Naples. The port for Cumae became Puteoli (Pozzuoli), the most important trading port in Italy throughout most of Roman history. Naples became the most populous city in the rich district of Campania. It opposed Roman expansion there for many years. After the Romans took control of it, however, wealthy Romans built sumptuous seaside villas all around its bay. Many Romans, including Vergil, learned Greek literature and philosophy from Naples’ poets and philosophers.

Numerous other Greek settlers soon followed the founders of Cumae. Greeks established so many cities in southern Italy and Sicily that the Romans called the whole area Magna Graecia, Great Greece. Attracted by fertile soil, Greeks from Achaea (a region in the northeast of the Peloponnese) settled on the western shore of the Gulf of Tarentum at Sybaris around 720 b.c.e. and Croton around 710 b.c.e. Sybaris was so famous for luxurious living that the term sybarite is still used to refer to a pleasure-loving person. Croton was the home of a series of famous athletes who competed and often won at the Olympic Games in Greece. To the north of Croton and Sybaris, the Spartans founded Taras (Tarentum, Taranto), also about 710 b.c.e. It became a great manufacturing center and gave its name to the whole gulf on which it was located. In 444/443 b.c.e., Athenians founded Thurii near the site once occupied by Sybaris, which Croton had destroyed during a bitter war in 510 b.c.e.

Sicily

Across from Italy, on the fertile island of Sicily, the Greeks founded even more cities than in Italy proper. There, they were the rivals of the Phoenicians, who settled on the western end (p. 17). The Greeks eventually occupied most of the rest of the island at the expense of the older, native inhabitants. The oldest of the Greek cities there, as in Italy proper, was established under the leadership of Chalcis. Founded about 730 b.c.e., it was named Naxos for some fellow settlers from the island of Naxos. It was located at the base of Mt. Aetna, where it guarded the Straits of Messana (Messena, Messina), between Sicily and Italy.

Dorian Greek cities predominated on the southeastern and southern coasts of Sicily. Of them, Syracuse, founded by Corinthian settlers around 730 b.c.e., was the most important. Syracuse grew even larger than Athens and rivaled it in wealth, power, and culture. Athens, with disastrous results for itself, attacked Syracuse in 415 b.c.e. during the Peloponnesian War. In the fifth, fourth, and early third centuries b.c.e., several powerful tyrants and kings ruled Syracuse. They vied with Punic Carthage and various Sicilian Greek cities for dominance in Sicily. Some even tried to take over Greek cities in Italy.

Decline of the Greek cities in Italy and Sicily

Greek city-states founded in Italy and Sicily achieved a high level of prosperity, culture, and political sophistication. Nevertheless, they failed to stop the Roman conquest of Italy in the fourth and third centuries b.c.e. The individual Italian and Sicilian Greek cities were unable to find a middle ground between uncooperative independence and predatory imperialism. Rather, they perpetuated the fierce independence and predatory rivalries of Greek city-states everywhere. Therefore, their alliances were weak and their empires unstable. While borrowing heavily from their artists, writers, and philosophers, the Romans ended their independence one by one.

The Etruscans

The Phoenicians and Greeks who traded and settled in Italy had an enormous impact on the social, economic, political, and cultural development of its native peoples, especially on those people known as Etruscans. The Greeks called them Tyrsenoi or Tyrrhenoi, and the Romans called them Tusci or Etrusci, but they seem to have called themselves Rasenna. The question of where the Etruscans originated has been generating speculation and controversy for at least 2500 years. According to Herodotus the earliest Greek writer of history (fifth century b.c.e.), the earliest Etruscans were Lydians who had migrated from Asia Minor to find a new homeland when their own was suffering from famine. About 450 years later, Dionysius of Halicarnassus (Herodotus’ birthplace) took the opposite view in his Roman Antiquities (Book 1.25–30). He claimed that the Etruscans were native to Italy.

FIGURE 2.2 Temple of Concordia, Acragas (Agrigentum), Sicily, fifth century b.c.e.

Despite sensationalistic claims, DNA research published in the early 2000s does not confirm Herodotus’ account. Genetic links between both ancient and modern people and cattle in Tuscany and modern people and cattle in Turkey (ancient Anatolia, including Lydia) are not conclusive. They may merely reflect a much earlier spread of pre-Indo-European, Neolithic farmers from Anatolia to Italy, people whose descendants could have formed the bulk of the non-Indo-European-speaking population of ancient Etruria and whose genetic traces would remain in the modern populations of both Tuscany and Turkey.

Contemporary scholars also find no support for a modern theory that the Etruscans migrated from central Europe before 1000 b.c.e. and settled in the Po valley and later in Etruria. In fact, the most tenable modern hypothesis still is one that can be compared with Dionysius’. Extensive archaeological research indicates that Etruscan towns and cities evolved from villages that were part of the Villanovan culture during the late Bronze and early Iron Ages in Italy (p. 8).

This evolution began after the Phoenicians and Greeks started trading and settling along Italy’s western shore. Most early Etruscan towns appear on or near earlier Villanovan sites without any radical break in the archaeological record to indicate an invasion of new people. For example, as at Tarquinia (Tarquinii), one of the earliest Etruscan cities, different styles of burial and the kinds of objects found in graves appear to result from progressive development: first, early Villanovan cremation and burial in simple urns; then either cremation and burial or inhumation (burial of the whole body) in trench graves (with more luxurious grave goods in each case); and finally, the general practice of inhumation in elaborately decorated and furnished rock-cut chamber tombs.

The early Orientalizing Period of Etruscan civilization in the late eighth and early seventh centuries b.c.e. shows many Near Eastern and Aegean influences in art, jewelry, dress, and weaponry. These influences were not limited to the Etruscans, but were part of a more general cultural development among the peoples of central Italy. They are rightly seen as the result of initial trade and contact with Phoenician and Greek intermediaries. There was no wholesale influx of outsiders. Although Greeks did begin to settle in Campania with the establishment of the colonies at Pithecusae (Aenaria, Ischia) and Cumae on the Bay of Naples around 770–750 b.c.e., they did not settle farther north nor even move into the interior of Campania. The indigenous communities already may have been numerous and well organized enough to resist Greek incursions.

Greek colonies were the primary vehicles of trade and contact. For example, the Etruscan alphabet quite clearly seems to have been borrowed from the Greek alphabet used at Cumae. There is no evidence of Etruscan literacy before contact with the Greeks, and the Greek colonies along the Bay of Naples remained resolutely Greek while sites elsewhere in Campania became Etruscan. There was no significant mixing of populations. A few individual Greeks and Phoenicians may have been resident in various early Etruscan cities and taken native wives. More than that cannot be said. Even in questionable historical legends, there is no hint of anything more than that for the Greeks. There is no evidence for any presence of Phoenician residents until the seventh century b.c.e.

By that time, evidence of small enclaves of Phoenician–Punic merchants and craftsmen begins to appear in the archaeological record from some of the port cities on the coast of Etruria. A major find from Pyrgi, the port city of Caere, comprises three gold-leaf tablets. Two have inscriptions in Etruscan and one in the Punic dialect of Phoenician. They refer to the dedication at Pyrgi of a temple to the Phoenician goddess Astarte and date to ca. 500 b.c.e. That was long after the Etruscans had developed the characteristics that mark them as Etruscan.

The land of the Etruscans

Early Etruscan centers have been found at such places as Capua in Campania, Praeneste (Palestrina) in Latium, Veii and Volaterrae (Volterra) in Etruria, and Marzabotto and Felsina (Bononia, Bologna) in the Po valley. By 400 b.c.e., however, the expansion of other peoples had limited the Etruscans to a triangular area between the coast of the Tyrrhenian Sea, which still echoes their Greek name, and the Arno and Tiber rivers. Called Etruria in ancient times and Tuscany today, this region of Italy continues to recall the Etruscans’ Roman name, Tusci.

Geographically, Etruria falls roughly into northern and southern halves. Northern Etruria possesses fertile river valleys, plains, and rolling sandstone or limestone hills with metal-bearing strata. The southern part is wilder and rougher, shaped by the actions of volcanoes, wind, and water. The soft, volcanic stone, called tufa, has been carved into deep valleys or gullies that are surmounted by peaks or small mesas, on which many of the earliest Etruscan cities are found.

At a time when village life predominated in the largest part of Italy, Etruscan sites had already become towns, and some of the towns were becoming cities that appear in the story of Rome and Italy. These cities were often built on or near Villanovan sites, sometimes on the coast or near it on a river—Caere (Cerveteri), Tarquinia (Tarquinii), Vulci, and Populonia (Populonium)—and sometimes inland—Volsinii (Orvieto), Clusium (Chiusi), Perusia (Perugia), Arretium (Arezzo), and Volaterrae (Volterra). They and some other major cities found a place in written history by fighting the Romans. Archaeologists sometimes find forgotten towns, some of them important.

Ancient sources say that the Etruscan people at their height were organized into a federation of twelve major cities. It is, however, not easy to list the twelve. The various sources do not agree on the names. Probably the membership changed as some cities rose in importance and others fell. Perhaps, more than one league existed. One of them may have been centered on a complex discovered in 1966 at Murlo, south of Siena. It was a rich and important site: large buildings have been found highly decorated with large terracotta (baked clay) statues and plaques depicting banquet scenes, a procession, a ritual scene, and a horse race. Substantial amounts of fancy pottery and even expensive jewelry have also been recovered. Later on, in Roman times, the city of Volsinii was said to have headed a league of twelve cities. When the Romans wiped out Volsinii in 264 b.c.e., they transferred its patron deity, Voltumnus, to Rome as the god Vertumnus—an early instance of the Romans’ willingness to absorb powerful gods belonging to other peoples.

Sources for Etruscan history

Most modern knowledge of the Etruscans is derived from the ruins of their cities and, more particularly, their tombs. Tombs of various sizes, shapes, and types—pit graves and trench tombs from Villanovan times, tumuli (great mushroom-shaped, grass-covered mounds with bases of hewn stone), circular stone vaults built into hillsides, and corridor tombs cut out of rock—no matter whether they contain pottery, metal ware, furniture, jewelry, or wall paintings all help to reveal the cultural life of the Etruscan people.

Nearly 13,000 Etruscan inscriptions dating from the seventh century b.c.e. to the first century c.e. have been found. Only about a dozen contain more than thirty words. Most are only lists of proper names, religious formulae, dedications, or epitaphs. Because Etruscan is written in an alphabet borrowed from the Greeks, the texts can be transliterated, and much progress has been made in translating them. Because Etruscan is not related to any other known language, however, the longer, more complex texts cannot be fully translated or understood without a bilingual key (such as the Rosetta Stone provides for ancient Egyptian). Unfortunately, the Punic and Etruscan inscriptions on the Pyrgi tablets (discussed above, pp. 22–3) were not equivalent enough to each other or long enough for that purpose. Still, advances in understanding and deciphering the language are being made, particularly as new material is found. In 1992, the Tabula Cortonensis, a large bronze tablet from Cortona (near Lake Trasimene), came to light. Its forty lines of text have added to scholars’ understanding of the meanings and grammatical forms or functions of Etruscan words. Useful social, religious, and cultural inferences also can be made from the stylistic and statistical patterns of words recurring in various inscriptions.

Unfortunately, surviving historical accounts of the Etruscans were all written by their Greek and Roman enemies. To the Greeks, the Etruscans, whatever their origins, are infamous as pirates and immoral lovers of luxury. Livy and later Latin historians describe a period of supposed Etruscan domination of Rome in the sixth century b.c.e. and concentrate mainly on Rome’s wars with Etruscan cities. Cicero and other Roman writers also comment on Etruscan religion and its influences. The result is a biased and very incomplete historical record.

Etruscan economic life

Etruscan civilization could not have existed without the natural wealth of its territory. The fertility of the soil and the mineral resources of the region were major economic assets (pp. 2–3). The Etruscans exploited them on a large scale through agriculture, mining, manufacturing, lumbering, and commerce.

The alluvial river valleys produced not only grain for domestic use and export but also flax for linen cloth and sails. Less fertile soils provided pasture for cattle, sheep, and horses. The hillsides supported vineyards and olive trees. As the population expanded, an ingenious system of drainage tunnels (cuniculi) and dams won new land by draining swamps and protected old areas by checking erosion.

The Etruscans energetically exploited the rich iron mines on the coastal island of Elba (Ilva) and the copper and tin deposits on the mainland. Many Etruscan cities exported finished iron and bronze wares, such as helmets, weapons, chariots, urns, candelabra, mirrors, and statues, in return for other raw materials and luxury goods. They also made linen and woolen clothing, leather goods, fine gold jewelry, and pottery. Virgin forests of beech, oak, fir, and pine fueled the fires of Etruscan smelters; supplied wood for fine temples, houses, and furniture; and provided timber for warships and commerce.

Trade kept Etruscan Italy in close contact with the advanced urban cultures of the Mediterranean world. It led ultimately to the introduction of money and a standard coinage. The earliest coins found in Etruria were minted by Greek cities. After 480 b.c.e., Etruscan cities began to issue their own silver, bronze, and gold coins.

Etruscan foreign trade was mainly in luxury goods and high-priced wares. It enriched the trading and industrial classes and stimulated among the upper class a taste for elegance and splendor. That explains the Etruscans’ reputation for excessive luxury among contemporary Greeks.

Etruscan cities and their sociopolitical organization

In the late ninth and early eighth centuries b.c.e., competition among neighboring chiefdoms for control of resources and trade in high-status goods probably stimulated the earliest Etruscan state formation. By the end of the seventh century b.c.e., the Etruscans had developed several strong states, each centered on a rich and powerful city. For economic reasons, they located some cities within fertile valleys or near navigable streams; for military reasons, they built others on hilltops whose cliffs made them easily defensible. At first, they fortified their cities with wooden palisades or earthen ramparts and then with walls of masonry, often banked with earth.

Inside the walls, the Etruscans seem to have laid out some of their cities on a regular grid plan, as the Greeks had begun to do. In some cases, they appear to have centered the plan on two main streets intersecting at right angles, like the cardo and decumanus (main thoroughfares) of the later Roman military camp. The first monumental buildings to go up were temples for the gods and palaces for the kings. Then, as the population increased, side streets were paved, drains dug, and places for public entertainment built. These cities, as in Greece, were the political, military, religious, economic, and cultural centers of the various Etruscan states. As already noted, groups of cities formed themselves into leagues primarily for the joint celebration of religious festivals. The mutual jealousy of the member cities and their insistence on rights of sovereignty prevented the formation of any federal union that might have acted to repel the aggression of the Romans, who defeated them one by one. When events at last forced some cities to put up a united defense, it was too late.

Evidence from Etruscan inscriptions, Etruscan tombs, and later Greek and Roman writers reveals the broad outline of Etruscan political history. The executive power of each early Etruscan city-state was in the hands of a king. He was elected for life and assisted by a council of aristocratic chiefs. The king was the symbol of the state, commander-in-chief of the army, high priest of the state religion, and judge of his people. He wore purple robes and displayed other symbols of status and power. At least some kings had attendants who carried fasces (bundles of rods) and double-bitted axes, symbols of judicial, military, and religious authority. Later, lictors attended high public officials at Rome with these same symbols.

In many cities during the sixth or fifth century b.c.e., the nobles stripped the kings of their powers and set up republics governed by aristocratic senates and headed, as in Rome, by magistrates elected annually. The real power in the state was at all times in the hands of a small circle of landowning families. Having acquired or seized large tracts of the best land, they became a landed elite and enjoyed all the privileges of a warrior aristocracy and priestly class. In some cities, they were later forced to share power with a small group of wealthy outsiders who had won wealth and social standing through mining, craftsmanship, or commerce. The middle and lower classes consisted of small landowners, shopkeepers, petty traders, artisans, foreign immigrants, and the serfs or slaves of the wealthy.

Women and the Etruscan family

Women and the family played prominent roles in Etruscan life. Etruscans came to have two or three names corresponding to the Roman praenomen, nomen (gentilicium), and cognomen (pp. 60–1). The first indicated the individual, the second the family at large, and the third a particular branch of the family. Those who could afford the expense built large family tombs capable of holding many individuals. Epitaphs frequently recorded both the father and the mother of the deceased; the inclusion of a matronymic is distinctly Etruscan. Romans and Greeks only recorded their fathers’ names. Tomb paintings and sarcophagi (coffins) often portrayed husbands and wives reclining or seated together in mutual respect and affection.

An Etruscan wife often appeared in public with her husband. She went to religious festivals with him, and, unlike her Greek counterpart, she reclined beside him at public banquets. The common practice of decorating women’s hand mirrors with words indicates a high degree of literacy among those who could afford these expensive items. Many Etruscan women also took a keen interest in sports, either as active participants or as spectators. Their presence at public games, where male athletes sometimes contended in the nude, was scandalous to the Greeks, who usually forbade their women to witness such exhibitions.

FIGURE 2.3 Clay sarcophagus from Cerveteri (Caere), Etruscan, sixth century b.c.e.

Etruscan culture and religion

Etruscan as a spoken language persisted as late as the second century c.e. Enough written material survived until the first century c.e. to enable the Emperor Claudius I (41–54 c.e.) to write an Etruscan history in twenty volumes. Nevertheless, all Etruscan literature is now lost. There probably were many works on religion and the practice of divination and, perhaps, annals of individual families and cities. There were also some rustic songs and liturgical chants. If the Etruscans composed poetry, dramas, or sophisticated works of philosophy, history, or rhetoric, no trace of them has been preserved or recovered.

Music and dancing brightened the lives of the Etruscans. They liked the flute, whose shrill strains accompanied all the activities of life—banquets, hunting expeditions, athletic events, sacrifices, funerals, and even the flogging of slaves. As flutists, trumpeters, and lyre players, they were renowned in Rome and throughout Greece. Tomb paintings, decorated bronze vessels, and painted pottery show them dancing at banquets, religious festivals, and funerals.

FIGURE 2.4 A wall painting (ca. 475 b.c.e.) in the Tomb of the Lionesses at Tarquinia showing a ritual dance.

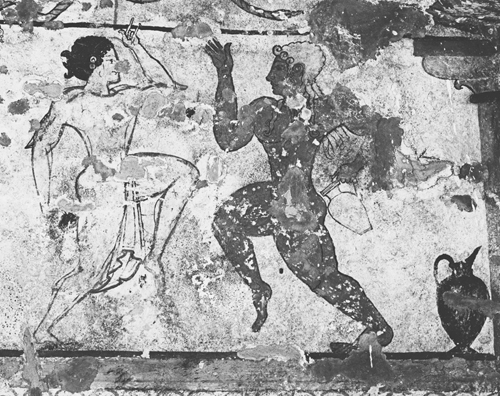

FIGURE 2.5 A wall painting (ca. 500 b.c.e.) in the Tomb of the Augurs, showing wrestlers.

Sports

Tomb paintings also show that outdoor sports assumed an important place in Etruscan life. Because of their association with religion and rites for the dead, sports were serious affairs. To neglect them was considered a sacrilege. There were also sociological reasons for the popularity of games. The growth of cities, the expansion of industry and commerce, and the rise of a wealthy leisured class gave the time, opportunity, and money for indulgence in sports of all kinds. Hunting and fishing, which for prehistoric people had been a labor of necessity, became a form of recreation for the Etruscan rich. Next to hunting, riding and chariot racing were favorite sports.

Organized athletic competitions, such as were common in Greece, were especially popular. They gave upper-class youths a chance to display their skill and prowess; they served also as a source of entertainment for the masses. Most illuminating in this regard is the great painted frieze inside the Tomb of the Chariots at Tarquinia. It shows a vast stadium and a large number of spectators of both sexes applauding and cheering the charioteers, runners, boxers, wrestlers, and acrobats. Several paintings reveal the popularity of the equivalent of the Roman gladiatorial contest, which formed part of extravagant funeral games.

Religion

Many modern writers have asserted that the religion of the early Etruscans was pervaded with fear and gloom and dominated by a superstitious and authoritarian priesthood. Yet, wall paintings found in early tombs reveal that those who could afford such luxuries were joyous, life-accepting people. Like ancient Egyptians, they expected this life to continue in an afterlife.

Etruscans of all classes believed that the deities ruling the universe manifested themselves in every living thing: in human beings, in trees, in every flash of lightning, in lakes and streams, in the mountains and the sea. To penetrate the divine mysteries, to make the deities speak, to wrest from them their secrets called for elaborate ritual. Once discovered, divine will had to be obeyed and executed with meticulous care. As time went on, Etruscan religion does seem to have become more and more formal, theological, and legalistic in the struggle to guarantee the goodwill of powerful deities.

The Etruscan gods paralleled those of the Greeks and Romans. First among them was Tinia, who, like Zeus and Jupiter, spoke in thunder and hurled his lightning bolts across the sky. He executed the decrees of destiny. With him were associated two goddesses of Italic origin, Uni (Hera, Juno) and Menrva or Menerva (Athena, Minerva). Together, they formed a celestial triad whose temple (kilth) stood in every Etruscan city and on the Capitoline Hill at Rome.

The most striking aspect of Etruscan religion was the so-called Disciplina Etrusca (Etruscan Learning). It was an elaborate set of rules that aided the priests in the practice of divination. That entailed the study and interpretation of natural phenomena to forecast the future, know the will of the gods above, and turn away the wrath of the malignant spirits beyond the grave. There were several kinds of divination. The most important was hepatoscopy, the inspection of the livers from sheep and other animals slaughtered for sacrifice by special priests (haruspices). In fact, archaeologists have discovered several bronze and terracotta models of sheep’s livers that may have been used for training priests. Thunder, lightning, and numerous other omens were also studied as tokens of the divine will (see Box 2.1). The flight of birds, which the Romans studied with scrupulous care before battles, elections, or other affairs of state, was of secondary importance to the Etruscans.

2.1 The brontoscopic calendar

The longest extant Etruscan document is not preserved in the Etruscan language. The sixth-century c.e. Byzantine scholar John the Lydian translated into Greek an earlier Latin translation of an Etruscan brontoscopic calendar that was the work of P. Nigidius Figulus, one of the great Roman experts in divination who lived at the end of the Republic in the first century b.c.e. Cicero, a contemporary of Nigidius and the greatest orator of his day, referred to Nigidius as “the most learned and most venerable of all men”; Nigidius is known as the author of numerous works on natural history and religion, especially divination, all of which are now lost. Brontoscopy is the science of determining the will of the gods and predicting the future through the study of thunder, an important element in the Disciplina Etrusca. The calendar is arranged by twelve lunar months, beginning with June, and contains terse statements like “13 July: If it should thunder, very poisonous reptiles will appear,” and “29 March: If it thunders, women will lay claim to a better reputation.” The calendar reveals a society with many worries, most significantly diseases of man and beast, agricultural disasters, and civil unrest.

Etruscan art and architecture

Early Etruscan art developed under the influence of ancient Near Eastern models as mediated by Phoenician and Greek merchants and craftsman. Later, Etruscan artists adopted aspects of archaic, classical, and Hellenistic Greek art. Still, Etruscan art is not merely derivative. It reveals its own lively spirit that sets it apart from its models. There is an emphasis on individual particulars rather than abstract types. It is full of movement, emotions, and the enjoyment of life.

Sculpture

Etruscan stone sculpture was not highly developed. Soft stone like limestone, travertine, and tufa were easily and often carelessly carved. Many examples come from graves and tombs. Some places marked graves with statues of sphinxes, lions, and rams. Others used squared pillars, cippi (sing. cippus), carved with vertical reliefs; still others used horseshoe-shaped slabs, stelae (sing. stele or stela), decorated with reliefs in horizontal bands. Stone funerary urns and caskets, sarcophagi (sing. sarcophagus), were also decorated with lively reliefs. Some featured half-length busts or complete standing, sitting, or reclining figures.

Terracotta was popular for votive plaques. Terracotta relief panels often sheathed the exposed wooden parts of temples and important buildings. Some workshops produced large terracotta sarcophagi in the shape of couches with full-sized figures of men and women reclining separately or together on them (p. 26, Figure 2.3). Archaic temples in southern Etruria exhibited large statues of deities on their roofs. One of the most famous is a standing Apollo from the Portonaccio temple at Veii (p. 36, Figure 2.11) Despite archaic Greek elements, it is characteristically Etruscan in the vigor of the god’s stride and the tenseness of his muscular legs.

Many Etruscan cities produced bronze statuary. Small figures of deities, worshipers, warriors, and athletes were popular. A few magnificent large bronzes have also survived. It is disappointing that scientific analysis has now cast doubt on the Etruscan origin of the iconic Capitoline Wolf, which appears instead to have been crafted in the medieval period. Still, genuine works like the Chimaera of Arretium (fifth century b.c.e.) and the Mars of Todi (fourth century b.c.e.) are great achievements (pp. 32–2, Figures 2.7 and 2.8).

Painting

Etruscan painting is preserved on pottery and wall paintings from many tombs. The drawing is bold and incisive; the colors are bright and achieve fine effects through juxtaposition and contrast. The themes, usually taken from life, are developed with direct and uncompromising realism. They are often brutally frank. In the Tomb of the Augurs at Tarquinia (sixth century b.c.e.), one painting shows two wrestlers locked together in struggle (p. 28, Figure 2.5). Another depicts a burly, thickset man with a sack over his head as he tries to knock down a savage dog held on a leash by an opponent.

The festive side of life is a favorite theme in tomb paintings. In the Tomb of the Lionesses, men and women are depicted reclining at a banquet. Everybody is in high spirits. In one scene, a massive bowl is wreathed with ivy, and musicians are playing. To the right of the bowl, a couple is performing a lively dance (p. 27, Figure 2.4).

FIGURE 2.6 The Capitoline Wolf (probably not a sixth-century b.c.e. Etruscan bronze, but apparently medieval [twin babes added in the Renaissance]).

FIGURE 2.7 The Chimaera, fifth-century b.c.e. Etruscan bronze. (The Wounded Chimera of Bellerophon.)

FIGURE 2.8 Mars of Todi. Etruscan (fourth century b.c.e.). Bronze (Scala/Art Resource, NY).

Minor arts

From ca. 650 to 400 b.c.e., Etruscan potters produced black pottery known as bucchero. A very shiny, thin-walled variety called bucchero sottile copied Greek shapes and resembled more expensive bronze vessels. Pieces were often decorated with incised pictures or geometric designs. Some had stamped or molded reliefs. A heavier, less graceful, matte-finished, and more elaborately decorated buchero called bucchero pesante appeared at Clusium (Chiusi) around 500 b.c.e. Etruscan potters also imitated sixth-century b.c.e. Greek black-figure ware. They could not, however, compete with the excellent Attic red-figure pottery that flooded Etruria in the fifth century b.c.e.

Etruscan smiths were very skilled at making beautifully decorated bronze ware for daily use, such as tripods, basins, and candelabra. Fancy bronze containers and mirrors were elaborately engraved with domestic scenes, stories from Greek and Etruscan mythology, and religious rituals. Even more impressive are the products of Etruscan goldsmiths. Intricate gold bracelets, necklaces, pendants, earrings, and pins show amazing levels of craftsmanship and design.

Architecture

The remains of houses and cities in which people lived are scarce. Buildings were made largely of perishable wood and mud brick. Some cities were completely destroyed in ancient times. The rest have been continuously inhabited and rebuilt so that their ancient remnants are difficult to find or excavate. Cities of the dead, necropoleis (sing. necropolis), have fared much better. They were cemeteries outside the inhabited areas of ancient Etruscan cities. Their tombs were built of durable stone slabs or cut out of living rock.

By the late seventh century b.c.e., wealthy Etruscans were building large chamber tombs for family burials. In some places, large round or square tombs were topped with mounds to create round tumuli (sing. tumulus). At southern sites, tombs came to be carved out of solid tufa. Many chambers resembled the interior rooms of houses and contained furniture, tools, weapons, pottery, jewels, food, and walls painted or carved with scenes and articles of daily life. Tombs came to be lined up like houses on formal streets. Gradually, they began to resemble the outsides of houses, too.

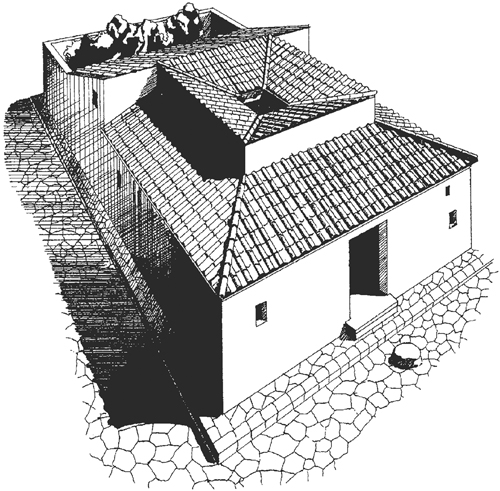

Models found in early graves show that Etruscan houses in the eighth century b.c.e. were similar to the small oval huts of wattle and daub with thatched roofs common in Villanovan villages (p. 12, Figure 1.4). Rectangular houses with terracotta-tiled roofs and rear courtyards appeared during the sixth century, and atrium houses evolved by the fourth. An atrium house had an unroofed central court around which the living rooms were arranged. It might also have a walled colonnaded courtyard off the back (accompanying illustration).

FIGURE 2.9 Drawing and plan of a Roman atrium house with a peristyle and hortus (garden) off the back, drawing and plan of. From Nancy and Andrew Ramage, Roman Art, 2d ed., Upper Saddle River, Prentice Hall (Pearson), 1996. Reproduced with permission.

Temples were a major feature of Etruscan architecture. They had the low, squat, top-heavy look of Italic temples in general (bottom of page). Often set on a hill, an Etruscan temple was also raised up on a stone base mounted in front by a broad flight of walled-in steps. The walls of the temple itself were built of mud brick. Wooden columns held up a deep porch in front. The solid walls of the cella (main chamber) were directly behind the porch. The cella, almost square in shape, was subdivided into three smaller chambers, one for each of a triad of gods. Each chamber had its own door at the front of the temple. Topping the whole structure was a long, low-pitched wooden roof protected by terracotta tiles. The wooden gable, ridge, and eaves were adorned and protected with brightly painted terracotta friezes and statuary of gods and mythical scenes.

FIGURE 2.10 Artist’s reconstruction of Portonaccio temple at Veii.

FIGURE 2.11 Apollo of Veii. Etruscan (ca. 500 b.c.e.). Painted terracotta. Height ca. 5 ft., 10 in. (1.8 m).

The role of the Etruscans in Roman history

As will be seen, Roman art, architecture, and social life shared much with Etruscan civilization. These similarities are often explained as cultural “borrowing,” particularly during a supposed period of Etruscan domination of Rome in the sixth century b.c.e. Indeed, sixth-century b.c.e. Roman archaeological remains look very much like what has been found from the same time in Etruria. The most recent research, however, indicates that Rome and the Etruscan cities were similar in this period not because of any externally imposed Etruscan takeover of Rome. Rather they shared in the development of a common central Italian culture. That culture was evolving from the interaction of native peoples with each other and with Phoenician and Greek traders and colonists.

The fate of the Etruscans

By 600 b.c.e., the Etruscan cities had become the most powerful in Italy. In the Po valley, they battled the Ligurians on the west and expanded eastward to take advantage of trade coming into northern Italy through the Adriatic Sea. In fact, the Adriatic takes its name from Atria (Adria), a city originally founded by Greeks at the mouth of the Po and taken over by Etruscans in the fifth century b.c.e. Many rich and powerful independent cities had risen in Etruria. Some joined in one or more leagues for common religious celebrations, but they do not seem to have developed any strong common political or military institutions.

Etruscan expansion and conquests in new areas stemmed not so much from the concerted drive of any expanding state as from the uncoordinated efforts of individual war chiefs and their retainers. On land, Etruscan warriors had begun to adopt the Greek hoplite style of warfare, in which soldiers wore metal helmets, breastplates, and greaves (shin guards) and fought in ranks instead of as individual “heroes.” Etruscan seafarers had also adopted the latest advances in naval architecture. In 540 b.c.e., a combined Etruscan and Carthaginian fleet won a naval battle over the Phocaean Greeks near Corsica and forced them to withdraw to Massilia (Marseille), a powerful Phocaean colony on the southeast coast of what is now France. In 525/524 b.c.e., however, the Greek colony of Cumae, on the Bay of Naples, repulsed an Etruscan attack. In 504, Cumae and some Latin allies defeated an army of the Etruscan adventurer Lars Porsenna at Aricia, sixteen miles southeast of Rome. In 474 b.c.e., Cumae joined forces with the Greek tyrant Hieron I of Syracuse and won a great naval victory over an Etruscan fleet. From that point, the Etruscan cities’ fate as independent states was sealed: the Gauls were moving into the Po valley, the Samnites began to take over Campania, the Romans soon started expanding into Etruria, and the Etruscan cities were too disunited to save themselves.

Overview

Rome originated in the context of wider developments in the Mediterranean and Italy. Phoenician explorers and traders reconnected post-Bronze-Age Italy with the greater Mediterranean world in the ninth century b.c.e. The Greeks soon followed. The Phoenicians, principally led by Tyre and Carthage, did not establish independent settlements in mainland Italy. The Greeks, however, planted so many colonies in southern Italy and Sicily that the two became known collectively as Magna Graecia, Great Greece.

Phoenician and Greek trade and contact stimulated the growth of both the cluster of native villages that became Rome and the communities that grew into the Etruscan city-states. Significant mineral and agricultural resources enabled the Etruscan cities to prosper. They were ruled by kings or oligarchies. Their wealthy elites created a distinctive society, particularly in regard to the status of women. They also developed a fairly uniform culture that combined earlier native traditions with influences from the Phoenicians and Greeks. The cities even joined together in one or more leagues to celebrate common religious festivals and public events. Like the Greeks, however, they remained politically fragmented and engaged in bitter rivalries. The disunity of both the Greeks and the Etruscans in Italy contributed to their eventual takeover by the Romans.

Suggested reading

Aubet , M. E. The Phoenicians and the West: Politics, Colonies, and Trade. Trans. M. Thurton . Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press, 1993.

Haynes , S. Etruscan Civilization: A Cultural History. Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, 2000.

Markoe , G. E. Phoenicians. Avon: British Museum Press, 2000.

Ridgway , D. The First Western Greeks. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press, 1992.