Chapter 34

The fourth century is one of the most culturally rich periods in Roman history. A revival of Classical Greco-Roman traditions followed the disruptions of the previous fifty years. There was also a creative interaction with the diverse traditions of native cultures that had been overshadowed in the period when Rome and Italy had dominated the life of the Empire. Christianity, having been freed from persecution and even enjoying imperial favor, became a major factor in that process.

Christianity and the expansion of Classical culture

Eusebius in his Greek Ecclesiastical History and Rufinus, who translated it into Latin, loudly proclaimed the total victory of Christianity over the old gods of Classical pagan culture between Constantine and Theodosius. For obvious reasons, that became the accepted position of the Christian Church, and it is still widely repeated. St. Augustine, however, rightly rejected this smug triumphalism. As Augustine himself was living proof, Christianity and Classical pagan culture interacted and influenced each other in countless ways (see Box 34.1). The worldviews of pagan and Christian thinkers had begun to converge under the influence of Neoplatonism (p. 554).

34.1 The codex calendar of 354 c.e.

An elegant example of the interaction between Christianity and classical pagan culture was created in the year 354 c.e. by the most famous Latin calligrapher of the day, Furius Dionysius Filocalus. He created a richly illustrated book (codex) that was then presented as a gift to a wealthy aristocrat named Valentinus. The original was lost by the early medieval period, but several copies survive.

The codex, created by one Christian for another, presents a blend of pagan and Christian material that appears to reflect the relatively peaceful coexistence of these two major religious groups in Rome at the time the book was created, and it reinforces the idea of parallels between Christian and imperial institutions. The book’s centerpiece is a month-by-month calendar of festivals, games, and other events celebrated in the city – the official Calendar of Rome for 354 c.e. This includes only pagan holidays and anniversaries, as these were the most important items in the communal calendar. The other sections of the codex preserve information important for every Roman aristocrat of the day: a brief history of the city; chronological lists of emperors, consuls, city prefects, martyrs, and bishops; a list of dates for the Easter holiday up to the year 411 and another recording imperial birthdays. The codex also includes astrological plans, important to both pagans and Christians in the mid-fourth century c.e.

In the end, Christianity did more to spread Classical culture to those previously excluded from it than to destroy it. Although Classical culture had spread far and wide over the Roman Empire, it had done so like a net, not a blanket. It had been restricted largely to those who had acquired traditional paideia, the educated Latin- and Greek-speaking elites of the Empire’s cities. The Mediterranean Sea lanes and Rome’s famous roads were the threads that tied together the urban knots into a strong net of imperial control. Often, neither Latin nor Greek was the native language of the poorly educated peasants of the countryside and lower classes of the cities. They constituted a large mass of “inner barbarians” who were excluded from the dominant culture of the urban elites.

Christianity had grown precisely because of its appeal to the excluded populations of the Empire. Christians believed that God had sent Jesus to save the souls of the poor and the humble just as much as those of the rich and powerful. The Christian Church actively sought to include the excluded through its missionary activities, charitable works, inexpensive rituals, and communal worship. Unfortunately, as Christians grew in power after Constantine, zealots and builders of personal empires also forcibly converted people who had not succumbed to gentler methods of persuasion.

Ironically, the original language of the Church was the premier language of the Empire’s educated classes—Greek. St. Paul, the writers of the Gospels, and the other authors of the New Testament all spoke and wrote Greek. Even the Jewish Scriptures used by Paul and other Hellenized Jews, who constituted many of Christianity’s early converts, was the Greek translation of the Hebrew Bible known as the Septuagint. One had to have a certain level of elite education to be able to read and study the texts that were the basis of Christian doctrine if one were to become an authoritative Christian leader. Translations, culminating with the great Vulgate Bible of St. Jerome (ca. 385), eventually made these texts available in Latin, the dominant language of the elites in the West.

Therefore, Christianity gave the formerly excluded populations access to elite culture through the Greek and Latin of its fundamental texts, teachings, and preachings. That may explain in part the attractiveness of Christianity to Constantine. He and his third-century predecessors had come from rough frontier provinces along the Danube. To the civilian population of the Mediterranean provinces, they and the rest of the Roman army were hardly different from the attackers whom they were supposed to fight. In the process of converting to Christianity and settling in Constantinople, Constantine sought to shed his uncouth military image and appear as a champion of the more civilized, civilian elements in Roman society. In the West, he promoted the recovery of the landed aristocracy, and in the East he gave the notables of the Greek cities extensive access to power in his new regime. Under Constantine and his Christian successors, political success lay open not just to military officers but once more to the cultivated men of civilian virtues.

The traditional paideia of civilian elites fostered a common code of cultured civility. That civility allowed them to create a system in which those religious issues that did divide them did not lead to constant conflict and intolerance. Pagan and Christian symbols were combined in ways that were acceptable to many in both camps. Constantine, for example, kept the title pontifex maximus, which indicated the emperor’s care of religious matters. After Gratian ceased to use it, it became a title of the bishop of Rome. Images of the old pagan deities in exquisite Neoclassical style were used to represent the power, peace, and prosperity of the restored order, which was also protected by the Christians’ God. His cross now appeared on such things as the foreheads of statues honoring Rome’s first emperor, Augustus, and his wife Livia outside the city hall of Ephesus and on the milestones along Roman roads.

Appealing to the educated urban elites, Christian apologists argued that their religion was the guarantor of civilization against the “barbarism” that seemed to be pressing in from all sides. As the “sublime philosophy,” Christian revelation was called the ultimate source of truth for the best teachings of the Classical philosophers. It was the firm foundation of the high ethical standards imparted by traditional paideia. Only the Christian God, they said, had saved the tottering edifice of the Roman Empire from collapsing during the shocks of the third century; through Christ, the solid steel of true philosophy could reinforce it for the future. In visual art aimed at elite audiences (frescoes, mosaics, elaborately carved sarcophagi, and expensively crafted small objects), Jesus is no longer the simple carpenter’s son of the Gospels who preaches to equally humble disciples and people of the countryside. He is now the Divine Schoolmaster dressed in a philosopher’s robe, seated on a professor’s cathedra (official chair), holding a book, and lecturing to similarly dressed well-bred men of philosophic visage. The classical figure of the cultured man seated in his study and holding a scroll of some famous author is transformed into a similarly seated Christian saint or evangelist with a book open before him.

Talented and ambitious men had acquired elite paideia in order to become part of the restored Empire’s new ruling class in the fourth century. Many had come from Christian homes or had converted to Christianity. Accordingly, they often ended up as leaders of the growing Church, which had intertwined itself tightly with the dominant culture of the restored Empire. By continuing to include the “inner barbarians,” Church leaders also could mobilize an impressive number of supporters and become powerful forces in their local communities and even imperial politics. Through thousands of sermons, hymns, pastoral letters, inspirational writings, and devotional books in Greek and Latin, they inculcated into their flocks the languages and many other attributes of their own Classical educations. Thus, Greek penetrated even more deeply into the populations of the eastern provinces, and Latin replaced the languages of the countryside in the western.

In the cities, learned bishops exposed their congregations to sermons that displayed the highest standards of Greco-Roman rhetoric. The logic and metaphysical speculation of the Greek philosophical schools informed the theological debates surrounding the Trinity, the nature of Christ, and the status of the Virgin Mary. By incorporating the legal and administrative system of Rome into the Church’s institutional structure, these bishops reinforced the political and social values of the old Greek and Roman elites at the grassroots level. For Christians as well as pagans, therefore, education in the Greek and Latin Classics remained the key to cultural literacy and success in both secular and ecclesiastical careers (see Box 34.2).

34.2 The Classical education of Saint Jerome

Saint Jerome (see p. 703) played a central role in the creation of the Latin version of the Bible (the Vulgate), but he was also a man steeped in the classical tradition. Born about the year 347 c.e. to a wealthy Christian family in the province of Dalmatia, Jerome (Hieronymus, in Greek) received his early childhood education in his hometown of Stridon. At around the age of eleven or twelve, he and his close friend, Bonosus (who would grow up to become a famous hermit), were sent to Rome to further their education. It was here, under the tutelage of Aelius Donatus, the most important grammarian of the day, that Jerome laid the foundations of his own Latin style and honed his skills at interpretation and exegesis—all on pagan texts. Donatus’ influence on readers of Latin literature extended for centuries, well into the medieval period. This came directly through his own widely popular treatises on grammar and style, as well as through his commentaries on Terence and Vergil, authors central to the education of young students. Donatus also influenced readers indirectly through Jerome’s revision of older Latin translations of the Christian Bible into its canonical form and his original translation of certain books of the Old Testament into Latin directly from the original Hebrew and Aramaic, or from Greek intermediaries.

Monks, holy men, and Christian paideia

Of course, Christians who came from humble origins did not have the resources to attain the highest levels of elite paideia. For them, Christian baptism and revelation provided an alternative route to the virtue and wisdom claimed by the educated elites. Through such claims, the poor and uneducated people of low status in society could assert their worth as moral and intellectual equals, nay, even superiors, to the culturally dominant upper classes. By ostentatiously rejecting the trappings of cultured life that the upper-classes held dear, ordinary Christians could, paradoxically, claim to have beaten their “betters” in what traditionally mattered most, moral excellence and wisdom.

That attitude was manifest to the extreme in the great growth of Christian asceticism (from the Greek asketikos, characterized by rigorous training) during the fourth century. Great numbers of Christian men and women sought to live alone as monks (from the Greek monachos, solitary) and hermits (from the Greek eremites, dweller in the desert [eremos, eremia]) or anchorites (from the Greek anachorites, one who has withdrawn to the countryside). As already noted in the earlier discussion of virginity and celibacy (p. 619), during the fourth century, there was a growing interest in the ascetic rejection of the body and physical world in favor of spirituality. The ideal of the solitary holy or wise person living a pure life apart from the world became especially attractive to Christians: Jesus is said to have told people to give up their worldly goods in order to enter the kingdom of heaven. This ideal had had its counterpart for centuries in that of the pagan philosopher who dressed in a simple cloak and gave up the pursuit of worldly fame and riches for that of goodness, beauty, and truth. If Christianity was the sublime philosophy, then Christians who gave up the comforts of a civilized community and struggled to pursue holy wisdom in their desert cells became the sublime philosophers.

Those who took up such an arduous task became popular heroes. People saw in them superhuman concentrations of wisdom and spiritual power similar to those of the old pagan oracles and miracle workers. Many sought their advice and their healing power. Others, who hoped to emulate their example, set up camp nearby. Soon the surrounding desert became as crowded and busy as the society that they had left behind. If one wished to remain free of the distractions of human society, it was necessary to strike out farther into the desert.

Early Christian monasticism is illustrated by St. Anthony, the son of a moderately well-to-do Coptic farmer near Thebes in Upper Egypt. He took literally Jesus’ reported challenge to give up everything and follow him. Anthony became a hermit on the outskirts of his village around 270. By 285, he had moved his cell much farther into the desert proper, away from the nearest habitation. Even there, however, he attracted others, and by 305 he had organized them into a loose community called a laura. The monks remained completely autonomous. They met together for common worship once a week but were not bound by formal rules or institutions. This movement gained further momentum from a highly fictionalized Greek biography of St. Anthony. Ascribed to St. Athanasius of Alexandria, it achieved wide popularity and quickly appeared in the West via Latin translations.

Soon some monks began to live together and share a common life under fixed regulations and the directions of a leader. They came to be known as cenobites from the Greek words meaning common life (koinos bios). Their leaders were eventually called abbots from the Aramaic word for father (abba). In 326, St. Pachomius founded the first known such community at Tabennisi, near Thebes in Egypt. He enforced strict discipline and physical labor under the abbot’s direction.

Both eremitic and cenobitic monasticism spread rapidly among men and women in the East. In 360, St. Basil of Caesarea (Cabira, Niksar) in Pontus set up a new form of cenobitic monastery. His rules were more elaborate and humane than those of Pachomius. He prescribed more study and communal labor rather than excessive asceticism. Basil’s rule was widely imitated and became the model for Greek monasticism.

Monasticism did not spread so rapidly or become so popular in the West as in the East. St. Martin of Tours pioneered the movement in Gaul at Poitiers about 360, but only two or three other Gallic monasteries existed by 400. It was also around 400 when St. Ambrose brought monasticism to Italy and St. Augustine introduced it into North Africa.

Ostensibly cut off from the outside world, those who followed the ascetic life were kept in touch with what was going on through many letters and visitors. They also had to go to neighboring villages and towns to get their grain ground and exchange produce or handicrafts for the bare necessities that even they occasionally needed. Many monks hired themselves out as seasonal laborers to acquire the meager rations of grain needed to sustain them. In the East, the ascetics who settled on marginal lands, particularly in the Egyptian, Syrian, and Judean deserts, helped to pioneer the settlement of those areas for the region’s expanding population. In the West, monasteries more often were associated with the activities of urban bishops and were founded as communities in or near their cities. The ascetic rejection of the civilized ideals embodied in the traditional pagan concept of paideia took particularly striking forms in Syria. Asceticism had already been popularized there by Gnostic sects (p. 533), Manichees (pp. 550–1), and Marcionite Christians (p. 493). In the mid-fourth century, the Syriac Christian writer Ephrem of Nisibis popularized an extreme brand of asceticism that inspired truly bizarre behavior in many Syrian holy men. Some lived for years on small platforms atop columns as stylites (from stylos: column in Greek), some literally became wild men who dressed in a few skins and ate grass and roots as “grazers,” and others immobilized themselves in chains under the most deprived circumstances.

Not all of them were so uneducated as stereotypical, pious biographies indicate. A number were educated people of a fairly privileged background. They had decided to abandon their previous ways of life for an ascetic one as the path to true wisdom and virtue. On the one hand, they ostensibly rejected the trappings of the cultured life that paideia fostered. On the other, as writers, orators, and thinkers, they used the skills that it had inculcated to promote the ascetic ideal and advocate their own positions on theological issues.

Many monks and holy men in the East became embroiled in the religious and theological disputes of neighboring cities and towns. They often engaged in fanatical actions against Jews, pagans, and Christians whose views differed from theirs. For example, in 386, bands of Syrian monks attacked the temples of local villages. In 388, one group destroyed the house of worship used by Valentinian Christians (who were labeled heretics because their founder, Valentinus, held certain Gnostic beliefs) and even burned down the Jewish synagogue at Callinicum (p. 605). In 391, under the urging of Bishop Theophilus at Alexandria, a mob of monks tore down the Serapeum, the great temple of Serapis that had been at the heart of the city’s pagan identity for centuries.

In these and many other episodes, powerful Christian bishops and zealous monks made Christianity the dominant religion of the Empire. Often they had the tacit consent of Theodosius, who could not risk openly attacking shrines and practices dear to many of his subjects. Christian leaders were satisfied, however, with banishing the pagan gods and sacrifices from public life. As yet, they made no concerted moves against educated and influential pagans, with whom they shared much else in common and who continued to express themselves in art and literature in traditional ways. In fact, both Christians and pagans contributed to a fourth-century cultural flowering that was pollinated from many sources in the Empire’s diverse landscape.

The educated world of letters

The return of stability under Diocletian and Constantine and their expansion of the imperial bureaucracy created a heavy demand for education. Many leading families throughout the Empire felt the need to reestablish continuity with Rome’s glorious past after the disruptions of the previous half-century. Members of the newly risen ruling elite needed to become better acquainted with the core culture of the Empire and acquire the refinements appropriate to their new status. For example, even Germans who achieved military and political importance in imperial service sought the education of Roman aristocrats. Therefore, generous public salaries were once more provided to teachers of rhetoric and philosophy, and students flocked back to their schools from all corners of the Empire.

Minor secular Latin literature in the fourth century

Recovering and reconstructing the elite culture of the Latin West was particularly difficult. It had not been so deeply rooted outside of Italy as elite Greek culture had been in the Greek-speaking cities of the East. Therefore, during the first half of the fourth century, demand for basic textbooks, reference works, commentaries, and technical handbooks was particularly great in the Latin West. Besides grammar and rhetoric, topics like medical and veterinary science, military science, agriculture, practical mathematics, and geography all found their fourth-century muses. Geographical subjects were particularly popular among Latin writers. Latin was still the language of administration throughout the Empire, and the elite needed to have an idea of the vast and diverse regions under their control. One of the geographical works is a treatise of unknown authorship written in about 360 and entitled Expositio Totius Mundi et Gentium (A Description of the Whole World and of Nations). What it says about non-Roman peoples is often fantastical. The descriptions of Roman provinces and their cities are cursory but give a sense of the Empire’s extent and the principal products available in each part.

Furthermore, pious Christians from the Latin West who made pilgrimages to the holy shrines of the Greek East wanted to know what to expect along the way. Various maps, handbooks, and travelers’ accounts called itineraries survive from the fourth century. Pilgrimages are the subjects of two interesting itineraries. One is a trip by an anonymous author to Jerusalem in 333, the Itinerarium Hierosolymitanum, which starts in Burdigala (Bordeaux) and returns to Milan via Rome. The other is the Itinerarium Egeriae (or Peregrinatio Aetheriae) by an aristocratic woman named Egeria (or Aetheria). Probably from Spain, she traveled on her own to Sinai, Palestine, and Mesopotamia in the late fourth century.

There was also a great demand for brief summaries of Roman history among the numerous officials and emperors who came from provinces not steeped in the traditions of Rome. The North African Aurelius Victor sketched the lives of the emperors through Constantius II in his Liber de Caesaribus. Shortly after the death of Theodosius (395), someone summarized Victor in the Epitome de Caesaribus and extended his account to 395. Another unknown writer also included Victor in a collection known as the Tripartite History to create a complete summary of Roman history by including the Origo Gentis Romanae (Origin of the Roman Nation), which covered the mythological past from Saturn to Romulus, and the De Viris Illustribus Urbis Romanae (Concerning the Illustrious Men of the City of Rome), sketches of famous men from the Alban kings to Mark Antony.

Two minor historians were members of the Emperor Valens’ court. One was Eutropius, who had served in Julian’s Persian campaign. He wrote the Breviarium ab Urbe Condita (Summary from the Founding of the City), which covered everything from Romulus to the death of Jovian (364) in ten short books. Clearly written and concise, it became very popular, was translated into Greek, and was often used in schools. Rufius (or Rufus) Festus wrote a similar summary that competed for the attention of Valens, to whom he dedicated it. Called the Breviarium Rerum Gestarum Populi Romani (Summary of the Deeds of the Roman People), it, too, extended from Romulus to 364 c.e., but it gave greater stress to wars of conquest.

The revival of the great tradition of Latin literature

The work of reconstruction and recovery during the first half of the fourth century led to a reflourishing of Latin literature among the great senatorial landowners during the second half of the century. Not all of them were pagan, but they wanted to link themselves firmly to the great traditions of Rome’s glorious past. They wanted to reinforce their power and influence in the Latin West by fostering a sense of community and renewal, a true Reparatio Saeculi (Restoration of the World) as even Christian emperors advertised on their coins. One of the central figures in this group was Quintus Aurelius Symmachus (ca. 340–ca. 402). His family took a special interest in preserving copies of Livy’s history, and he became the most famous Roman orator of his day. Holding many high offices, he fought St. Ambrose over removing the Altar of Victory from the senate (p. 603). Ten books of letters survive along with fragments of his speeches. They present a vivid picture of the life of the wealthy senatorial class in fourth-century Rome.

Ambrosius Theodosius Macrobius, who straddles the fourth and fifth centuries, presents a similar picture. As a young man, he was acquainted with the circle of Symmachus. His major work, the Saturnalia, purports to be the learned conversations of Symmachus and his friends at a banquet held during the Saturnalian festival. Their discussions about the festival, Roman antiquities, grammar, and literary criticism preserve a wealth of ancient scholarship otherwise lost. Macrobius also wrote a commentary on the “Dream of Scipio” from Cicero’s Republic. The idealized view of the Roman statesman and the Platonized Stoicism that underlay Cicero’s thought at that point were attractive to the Neoplatonic antiquarian pagans of Macrobius’ day.

It was probably in the same circle depicted by Macrobius that the strange biographical pastiche of fact and fancy known as the Historia Augusta was composed. It covers the emperors from Hadrian to the accession of Diocletian. It was written allegedly by six different authors in the reigns of Diocletian and Constantine. Computerized stylistic analysis, however, confirms the theory that it was really written by one person. That such a hoax could be perpetrated at all, however, indicates the existence of a bold and confident spirit at the time.

The more serious history of Ammianus Marcellinus (ca. 330–ca. 400) reveals a similar spirit, although its substance contrasts markedly with that of the Historia Augusta. The last great Roman historian, Marcellinus boldly took up the mantle of Livy and Tacitus by carrying the history of Rome from where Tacitus left off in 96 c.e. to the Battle of Adrianople in 378. Born probably a pagan at Antioch, he was a native speaker of Greek, but he retired to Rome after a successful military career and wrote in Latin. He used good sources and exercised a well-balanced judgment even though he had a definite agenda of his own. He seems to have hoped that a tolerant and enlightened pagan would provide the leadership necessary to block what he saw as a tyrannical partnership between the emperor and the Christian Church. Devoting over one-third of the work to the lifetime of Emperor Julian, he showed approval for the idea of a revived paganism. Nevertheless, he was critical of Julian’s overzealous hostility to Christianity. He also censured the moral failings of the great senatorial aristocrats.

Julius Obsequens sought to bolster the pagan cause in the little treatise De Prodigiis (On Prodigies). He summarized the prodigies recorded by Livy from 196 to 12 b.c.e. and showed how the Romans had avoided the calamities that they portended. He wanted to emphasize, therefore, that the old reliable rites should not be abandoned in favor of the Christianity that condemned them.

Any well-educated person was expected to be able to turn out a competent poem. Some fourth-century authors produced work that, if not equal to those of the Golden Age, at least measured up to the Silver. The most prolific and well-known poet of the fourth century is the Christian Decimus Magnus Ausonius (ca. 310–ca. 394). A member of the provincial aristocracy from Burdigala (Bordeaux) in Gaul, he received a rigorous education in the Classics. He then became a professor of rhetoric in his hometown, which had become a thriving educational center. His connections led to a successful political career at court and the coveted honor of a consulship in 379. Much of Ausonius’ poetry reveals the life and outlook typical of his class. His longest work, the Mosella, is an epyllion (little epic) celebrating the delights of the Moselle River valley with its lovely landscapes and prosperous estates. Although he was a Christian, Ausonius delighted in the recovery and preservation of Rome’s Classical heritage, which he skillfully reworked in carrying on a centuries-old literary tradition. What mattered most was whether something furthered the image of Rome’s lasting greatness, not whether it was pagan or Christian.

Hellenism in the fourth century

During the fourth century, the educated upper classes of the Greek-speaking East were firmly attached to Hellenism, the elite Greek culture fostered by traditional paideia. In the schools that flourished once more, Hellenism became closely linked with Neoplatonic philosophy, which blurred even further the distinctions – rarely very clear in earlier centuries – among magic, religion, rhetoric, science, and philosophy. Of the vast body of writings by fourth-century Neoplatonic teachers and scholars, however, only a fraction survives.

Iamblichus (ca. 250–ca. 325) stands out as one of the most influential men of the century. Born at Chalcis in southern Syria, where he received his early education, he ultimately studied Neoplatonic philosophy under Plotinus’ successor Porphyry. He then used Neoplatonism, particularly its Pythagorean elements, to support the ritualistic magic and superstitions of traditional paganism. Establishing his own school at Apamea in Syria, he spent his life trying to counteract the growth of Christianity and restore paganism. He created a vast synthesis of mystery religions and pagan cults centered on Mithras and buttressed with elaborate symbolism, sacrifices, and magical spells. He became a renowned theurge. His followers claimed that he caused spirits to appear, glowed as he prayed, and levitated from the ground.

Iamblichus’ writings, several of which survive, and the work of his students, inspired Emperor Julian to abandon the Christianity of Constantine’s dynasty and put the full weight of the imperial office behind revitalizing paganism in opposition to Christianity. When Julian became emperor, Iamblichus’ former student Eustathius, husband of the famed Sosipatra (p. 621), joined his circle at court. Except for a letter from Eustathius to Julian, the only writings to survive from that circle are the essays and letters of Julian himself.

The contemporaries to whom Julian wrote and often referred would not be so well known if it were not for Eunapius of Sardis (ca. 354–ca. 420). Eunapius was a relative and student of one of Julian’s former teachers. He shared Julian’s hatred of Christianity and zeal for pagan Hellenism. His Lives of Philosophers and Sophists are full of fascinating details that reveal the social, political, and intellectual life of the educated class. They also contain many absurd tales of mystical powers, magic, and miracles as Eunapius tries to create the pagan counterparts to the pious biographies of Christian saints. Unfortunately, Eunapius’ Universal History, which continued the work of Dexippus (p. 558) from 270 to 404, is lost. Although it was heavily biased in favor of Julian, it was based on much good information and was a valuable source to later historians.

Science and mathematics

Like many of the Neoplatonic philosophers and sophists, Eunapius also had scientific interests. One of his interests was in medicine, which he shared with his friend Julian’s doctor, Oribasius of Pergamum (ca. 320–ca. 400). Oribasius produced a collection of extracts from the great second-century physician Galen and an even more ambitious collection of excerpts in seventy or seventy-two books from medical writers as early as 500 b.c.e. Although the first is lost, most of the latter survives in whole or in summaries that he made for Eustathius and Eunapius.

Alexandria flourished again in the fourth century as a center of medicine and science. With public support, Magnus of Nisibis founded a thriving school of medicine there. He was a close contemporary of Theon of Alexandria (ca. 335–ca. 400), a famous Neoplatonic teacher of mathematics and astronomy, and father of Hypatia (ca. 355–415 [p. 621]). Several of Theon’s scientific essays and commentaries survive. Hypatia gained an even greater reputation than her father in mathematics and astrology, which in her teaching she combined with an interest in Hermetic and Orphic religious ideas. As a result, she was very popular and attracted many students. Her influence with the imperial prefect of Egypt so frightened the partisans of the violent and aggressive Bishop Cyril of Alexandria that they ambushed her one night, dragged her into a church courtyard, stripped her, and hacked her to death with potsherds.

The Sophists

Of the many men who concentrated on the teaching of rhetoric in the fourth century, only three are still represented by extant works: Himerius of Bithynia (ca. 310–ca. 390), Themistius of Paphlagonia (ca. 317–ca. 388), and Libanius of Antioch (314–ca. 393). Of the three, Libanius is the most important. Without his writings, our knowledge of the fourth century would be far poorer than it is now. He was the most famous literary figure in the Greek-speaking East. From all of Greco-Roman Antiquity, only Aristotle and Plutarch are comparable to him in the sheer volume of surviving work. His speeches, rhetorical exercises, and approximately 1600 letters take up twelve volumes of standard Classical text and span the years from 349 to 393. They are gold mines of social, political, and cultural history because Libanius was one of the central figures of his time and place. His vast correspondence linked him with emperors, prefects, governors, and many other prominent men of his day, such as Themistius, Himerius, and even the Jewish Patriarch Gamaliel.

A vigorous defender of pagan Hellenism, Libanius attracted talented and ambitious young men of the eastern provinces to his school in Antioch. Although he eagerly supported Julian’s attempt to restore Hellenic paganism to cultural and religious dominance, he advocated tolerance toward Christians. Indeed, a number of leading Eastern Christians, such as St. John Chrysostom, St. Basil, and St. Gregory of Nazianzus (pp. 638–9), were his students and friends. Julian’s death almost drove Libanius to suicide. He lived in constant fear of reprisals under the militantly Christian Emperor Valens. Still, his courage revived after Valens’ death at the Battle of Adrianople. He became influential again under Theodosius, who appointed him honorary praetorian prefect in 383.

Christian literature of the fourth century

Christian writers of the fourth century basically came from the same social and intellectual milieu as their pagan counterparts. In fact, they had often studied together at the same schools and exhibited the same Neoplatonic influences and rhetorical styles. Many Christian writers had not even become Christians until they were adults when Christianity began to penetrate the upper classes in greater numbers under Christian emperors.

Christian Latin authors

A good example of an upper-class convert in the Latin-speaking West is Arnobius (ca. 250–ca. 327). He had been a pagan rhetorician at Sicca Veneria in the North African province of Numidia. He suddenly converted to Christianity around 295 and became a powerful critic of pagan beliefs in his Adversus Nationes (Against the Nations). One of the greatest Latin Church Fathers, however, was Arnobius’ student and fellow North African, Lactantius (Lucius Caecilius Firmianus Lactantius [ca. 250–ca. 325]). He taught rhetoric at Diocletian’s court in Nicomedia. After converting to Christianity, he surpassed even Tertullian as the Christian Cicero. He argued that Christianity had absorbed and confirmed what was best in the old pagan world and would usher in an even better one through God’s salvation. In the De Mortibus Persecutorum (On the Deaths of the Persecutors), Lactantius’ stress on the triumph of Christianity and the glorification of Constantine became the hallmark of much subsequent Christian historiography. Two of Lactantius’ greatest successors in style and substance are St. Jerome and St. Augustine near the end of the fourth century and in the early fifth (pp. 703–4).

Hilary of Poitiers (Hilarius Pictaviensis [ca. 315–367]) started out as a well-to-do pagan in Gaul. He converted to Christianity and ended up as bishop of Poitiers around 350. He strongly opposed the Arian heresy in his De Trinitate (On the Trinity) and is the first known author of Latin hymns.

An even greater writer of hymns from Gaul was St. Ambrose (339–340 to 397), who became bishop of Milan. He came from a wealthy Christian family related to the great pagan traditionalist Symmachus at Rome. Ambrose himself was sent to Rome, where his family connections allowed him to pursue the finest education and a major political career. As governor of northern Italy, he was so successful that the people insisted on making him bishop of Milan in 374. Despite his initial reluctance, he became a zealous voice for orthodoxy against Arianism. He also used his powerful bishopric to overshadow popes, browbeat emperors, and oppose Symmachus over the issue of restoring the Altar of Victory to the Senate House (pp. 633–4). Too numerous to list here, his hymns, sermons, essays, and letters are invaluable for understanding the history of his time.

Another great Christian hymnist was Prudentius (ca. 348 to after 405), an advocate from Spain in the imperial administration at Ravenna. His two collections of hymns, Hymns for Every Day and The Martyrs’ Crowns, have had a great influence on western Christian hymnology. He also supported the removal of the Altar of Victory from the senate house in his essay Against Symmachus.

The writing of hymns in the fourth century paralleled the growth of Christian poetry in general, which reflected Classical models. The Christian poet Proba (ca. 310–380) provides a good example. She was a convert from the high aristocracy. Her knowledge of Vergil was so thorough that she was able to weave together different lines and partial lines from his works into a type of poem called a cento to express Christian ideas. Unfortunately, her epic on the civil war between Magnentius and Constantius II is lost.

Christian writers in the Greek East

With the victory of Constantine and the building of Constantinople as a primarily Christian city, ecclesiastical writers raised their rhetorical trumpets throughout the Greek-speaking East. The man who contributed most to the paean of the Church triumphant in the fourth century was Bishop Eusebius of Caesarea in Palestine (ca. 260–ca. 340). He was a learned student of Pamphilus, the student to whom Origen had bequeathed his library (p. 560). He had sought a compromise between Arians and anti-Arians at the Council of Nicaea (pp. 588–9). An ardent admirer of Constantine, he lauded the emperor and his sons in his Praise of Constantine and unfinished Life of Constantine. He also produced several apologetic works refuting attacks on Christianity and arguing for the truth of Christian beliefs.

Eusebius is remembered primarily as the first Christian historian. His Chronicle, preserved in Armenian and Latin translations, summarized the history of the world from Abraham to 327/328 c.e. His Ecclesiastical History is an innovative work that detailed the growth of what he considered the true Church from Christ’s birth to 324. In it, he abandoned the exclusively rhetorical approach used by most ancient historians and relied on extensive direct quotations from documents and his other sources to support his narrative.

Rhetoric, however, still shaped much of Eusebius’ work, as it did that of many other Greek Church Fathers. For example, St. Athanasius (ca. 295–373), bishop of Alexandria, had received a good Classical education in grammar and rhetoric. He utilized it against pagans and heretics in a vociferous defense of orthodoxy. As a deacon at the Council of Nicaea (325), he had played a major role in rejecting Eusebius’ attempt to reach a compromise position on the Trinity in the Arian controversy. Three years later, he was made bishop of Alexandria. Bitter political and theological conflicts there caused his exile five times. Twice he spent his exile in the West, where he introduced monasticism. He has left behind a large body of apologetic, dogmatic, ascetic, and historical writings along with numerous letters, which are all essential for understanding the crucial religious dispute of the century.

St. Basil of Caesarea in Cappadocia (330–379) and his fellow Cappadocian St. Gregory of Nazianzus (329–389) studied at Athens and probably with Libanius at Antioch. Basil is famous as the author of two sets of regulations, Long Rules and Short Rules, that formalized the monastic practices of the Eastern Orthodox Church (p. 631). He also wrote a very influential work entitled An Address to Young Men. In it, he discussed ways of adapting the traditional Classical curriculum to the needs of Christians. Made bishop of Caesarea in 370, he has left an impressive body of sermons, essays, and letters. The latter, numbering over 350, provide a fascinating look into his life and times.

Basil and Gregory of Nazianzus were both staunch defenders of orthodoxy against Arianism. Gregory has left forty-five excellent orations on topics ranging from the Trinity and love for the poor to eulogies. His lively letters also provide many details of interest to the historian. More astonishing are the 17,000 lines of poetry that employ all of the forms of Classical verse on a myriad of theological, moral, and personal topics.

St. Gregory of Nyssa (ca. 330–395) was the younger brother of Basil, who made him bishop of Nyssa in 371 or 372. He combined deep philosophical learning with genuine pastoral care and faith in the ability of people to develop their inner spirituality. His Against Eunomius offers one of the best defenses of orthodoxy against Arianism. His dialogue On the Soul and Its Resurrection rivals Plato’s Phaedo. One of his most interesting works is a biography of his sister Macrina, whom he presents as the ideal of Christian womanhood (p. 621).

John Chrysostom (ca. 354–407), whose last name means “Golden-Mouthed,” was the greatest orator among the fourth-century Greek Church Fathers. Born to a leading family at Antioch, Chrysostom studied first with the great Libanius, who would have chosen him as a successor had he not converted to Christianity under the influence of his second teacher, Meletius, bishop of Antioch. After six years as a monk in the Syrian Desert, Chrysostom was ordained a deacon at Antioch and preached his first sermon in 386. In 387, he made his mark in twenty-one sermons On the Statues. By them, he counseled and comforted his parishioners while Theodosius threatened harsh punishment for the destruction of his statues during riots over increased taxes that year (p. 611). His skill won him great admiration. For the next ten years, he was the greatest preacher in the greatest church at Antioch.

In 397, Chrysostom became bishop of Constantinople. His preaching made him an instant celebrity but aroused the enmity of other bishops, high officials, and the Empress Eudoxia (p. 663). Other bishops did not like the increased prominence of the bishop of Constantinople. The Empress Eudoxia and many members of the court resented his moral crusade against vice, luxury, and corruption. They also resented the great popularity that he gained from his charitable work with the poor, sick, and oppressed. Eudoxia eventually obtained his exile to Armenia, where he died. Almost a thousand of his impressive and moving sermons survive.

Many Greek-speaking Christian authors adopted the pagan forms of biography and the novel to write hundreds of hagiographies (lives of saints) and martyrologies (accounts of martyrdoms). Their fictions often overpower facts, but they still have historical importance by providing insight into the values and ideals being communicated. The most famous such work is the Life of St. Anthony (p. 630).

Fourth-century art and architecture

The establishment of the Tetrarchy under Diocletian and his colleagues ushered in a new era in Roman art and architecture. New styles developed alongside the Greco-Roman Classical traditions. They served the needs of imperial propaganda and, from the time of Constantine, the rapidly expanding Christian population and Church. In an increasingly spiritual and religious age, the hieratic traditions of Near Eastern art became more and more prominent in the arts of painting, mosaic, and sculpture. That tradition de-emphasized worldly full-bodied, three-dimensional naturalism. It strove for a flatter, transcendent, spiritual quality. Human figures were often posed in a rigidly frontal manner in order to focus on the full face. Facial features were frequently rendered schematically to de-emphasize the mortal person in favor of some greater reality, particularly through the treatment of the eyes as the “windows of the soul.” The rest of the body was hidden under simple drapery. The use of flat, perspectiveless presentations emphasized detachment from the world by making figures “float” on the surface of a relief, fresco, or mosaic. The importance of a figure like the emperor or Jesus was emphasized by making it bigger than the surrounding figures and reducing humbler folk to small, schematized, even crude figures.

FIGURE 34.1 Figures at St. Mark’s in Venice are thought to represent Diocletian and the other three tetrarchs.

Imperial portraiture and relief

In the official art of the emperors, many of those stylistic devices are often used to focus on the emperors’ extraordinary power, the permanence of their rule, and the subordination of themselves as individuals to higher things.

A perfect illustration is a group portrait of the four tetrarchs that probably once stood in Constantinople but is now built into an outside corner of St. Mark’s Cathedral in Venice. It is made out of dark-purple Egyptian porphyry, an extremely hard, durable stone reserved for imperial use. The four are divided into two pairs with arms clasped around each other’s shoulders to indicate the loyalty of each Caesar to his Augustus. Aside from a beard to indicate the older Augustus in each pair, the four are indistinguishable from each other to symbolize their unity and the primacy of their office over themselves as individuals. Their solid, squared-off shapes give the impression of the firmness and uniformity of their rule, while their wide-open eyes, deeply drilled pupils, and furrowed brows show their vigilance, commitment, and care. Similar features can be seen in imperial portraits on fourth-century coins.

Depictions of Constantine underscore his supremacy as a ruler. That is strikingly evident in the eight-and-one-half-foot-high head from a colossal marble statue of the seated Emperor Constantine. It was originally placed in the apse of the great Basilica of Maxentius and Constantine (p. 647). Enough fragments of the rest remain to show that it reached to a height of thirty feet and had the same heavy, square proportions that give the tetrarchs’ statues their powerful effect. The left hand probably held an orb to symbolize the emperor’s worldwide rule, whereas the right arm was held straight out from the side and bent ninety degrees upward at the elbow, with the index finger pointing to the heavenly source of that rule.

As that statue was meant to dwarf everyone in the presence of the divinely appointed, all-powerful emperor, so were the depictions of Constantine on the famous friezes that adorned his triumphal arch in Rome. One panel shows an enthroned Constantine in a pose much like that of his colossal statue. He towers over ranks of poor citizens reaching out to receive donations of money that officials, as depicted in four small panels above the crowd, were giving out in his name.

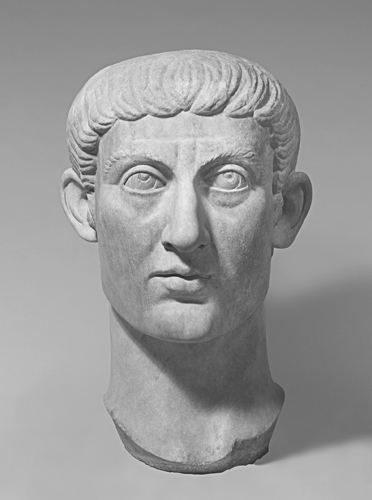

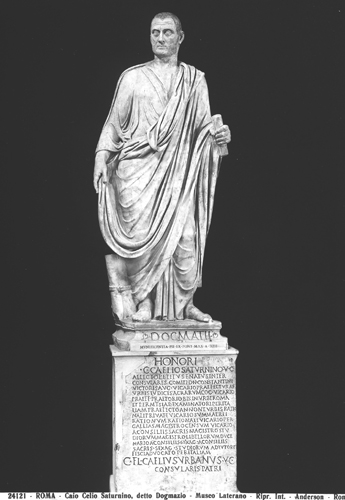

The continuation of the Classical style

Despite the very un-Classical elements found in fourth-century imperial sculpture and portraiture, much of the Classical tradition survived. For example, the portrait of C. Caecilius Saturninus Dogmatius, who rose to praetorian prefect under Constantine, clearly shows the traditions of realism in Roman portraiture (p. 643, Figure 34.3). Another larger-than-lifesize head of Constantine (above) maintains the squared-off look of the tetrarchs and the upraised look of the eyes, but the modeling of the chin, mouth, and nose is very Classical, reminiscent of the Augustus from Prima Porta (p. 393). Indeed, the slight tilt of the neck and the prominence of the ears enhance that resemblance.

FIGURE 34.2 Large portrait head of Constantine I, ca. 325–370 c.e.

Those parallels reinforced the idea that the age of Rome’s greatness had been restored (Reparatio Saeculi [p. 633]). Constantine further linked himself with the great age of the Empire at its height by reusing reliefs and sculptures from the monuments of Trajan, Hadrian, and Marcus Aurelius. Therefore, the Classical and newer, hieratic styles were found side by side on his triumphal arch.

FIGURE 34.3 C. Caecilius Saturninus Dogmatius, 326–333 c.e. Gregorian Profane Museum.

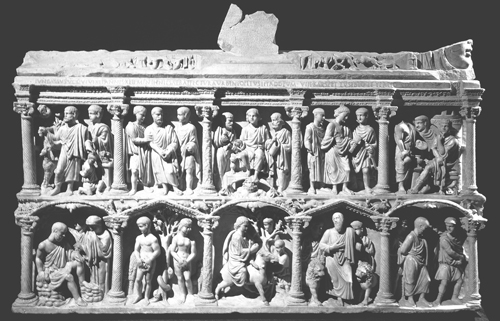

Constantine’s own hieratic friezes probably had been executed by sculptors who were used to carving the reliefs that decorated late third-century sarcophagi (p. 561). The wealthy new ruling elite of the fourth century linked itself to Rome’s glorious past through the Classical style of these elaborate funerary monuments just as it did through the revived study of Classical history, rhetoric, and literature. Even as Christian members of the new elite took over much from Classical literature, rhetoric, and philosophy to express their new faith, so they adopted Classical symbols, motifs, and styles in the visual arts for their sarcophagi.

The richly carved marble sarcophagus of the Roman aristocrat Junius Bassus (p. 644, Figure 34.4) who was urban prefect when he died in 359, spectacularly portrays Christian subjects in high Classical style. The front is divided into ten equal bays, five on top and five below. Each bay is framed by Corinthian columns, which support a straight entablature across the top row and alternating arches and pediments across the bottom. The scenes depicted in the bays are from the Old and New Testaments. Yet, the sculpting of the figures and clothes in each scene is clearly in the same tradition as the Parthenon frieze in Athens or the Ara Pacis of Augustus (p. 392). In the center of the top row, Jesus sits enthroned like a Roman emperor between Saints Peter and Paul. The two bays to his right depict Abraham preparing to sacrifice Isaac and St. Peter being arrested. The two to the left of Jesus show him facing charges before Pontius Pilate. Below, the central scene presents Jesus riding on a donkey to Jerusalem. To his right are Job on a dung heap and the naked Adam and Eve flanking the serpent and the Tree of Knowledge. To his left are Daniel being brought into the lion’s den and St. Paul being led to execution.

Many other works of art produced for wealthy Christians and pagans reflect the Classical revival of the fourth century. The fact that a work of art depicted a purely pagan scene did not mean that it belonged to a pagan any more than the owner of a copy of the Iliad or the Aeneid had to be a pagan. A great silver dish commemorating Theodosius’ tenth anniversary as emperor in 388 combines elements of the hieratic and Classical styles, while it also combines Christian and pagan motifs. It depicts Theodosius flanked by his son Arcadius and the western Emperor Valentinian II. They are all presented in the standard frontal hieratic, though not excessively rigid, pose, and each, like a Christian saint, has a nimbus projecting a divine aura around his head. Theodosius’ seniority in status and age is indicated by his greater size, and the armed guards are simply placed on different levels without any use of perspective to convey depth.

On the other hand, the three enthroned figures are depicted within a Classical architectural framework that closely resembles the entrance to Diocletian’s palace at Split (Spalatum, Spalato [pp. 646–7]). In the space below the enthroned figures, a fluidly curved partially draped Mother Earth figure reclines amid stalks of ripened grain in a scene reminiscent of the Ara Pacis of Augustus (p. 392).

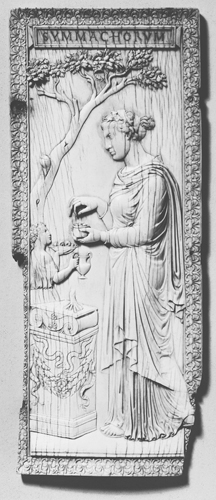

More purely Classical is a scene from the panel of a carved ivory diptych on p. 646. Such diptychs became popular among the wealthy elite to commemorate important events like marriages and consulships. This one seems to commemorate a marriage between two families associated with support of traditional paganism at Rome, the Symmachi and Nicomachi. The modeling of the figures and clothing is very Classical, and there is an attempt to portray depth, although the decorations on the altar are rather flatly incised instead of being carved in the round. Because a pagan sacrifice is depicted, the person who ordered it probably was making a religious statement, but it clearly became appreciated as a work of art to survive during the centuries after all members of the elite had embraced Christianity.

FIGURE 34.4 Marble sarcophagus of Junius Bassus.

FIGURE 34.5 Ceremonial silver dish depicting Theodosius I (The Great), Valentinian II, and Arcadius (end of the fourth century).

Mosaics and wall paintings

The great traditions of decorating the homes of the wealthy and well-to-do with mosaics and wall paintings continued in the fourth century. Many superb examples have been found all around the Empire. The painting of walls in an architectural style in the fourth century is indicated by the surviving interior walls of houses at Ephesus. Figured wall painting is known mainly from tombs whose owners probably were not rich enough to afford mosaics. Frontality, the lack of perspective, and the upraised eyes seen in other media are apparent in both pagan and Christian tomb paintings. Christians also increasingly decorated their churches with mosaics and wall paintings. Unlike pagan temples, which served primarily to house cult statues and dedicatory offerings, Christian churches were houses of worship, where congregational activities took place inside. Therefore, once they were secure and increasingly wealthy after Constantine’s rise to power, Christians began to build elaborate churches and decorate them in the tradition of fine homes and public buildings such as baths.

FIGURE 34.6 Ivory diptych of the Symmachi, 388–401 c.e.

Minor arts

Minor arts flourished in the fourth century. Ivory carvers produced not only commemorative ivory diptychs but also small, elegant, round lidded boxes, hair combs, and jewelry. Gem carvers and goldsmiths fashioned rings and jewelry of all kinds for the rich and powerful. Glassblowers and molders mass-produced bowls, cups, pitchers, and vases in many colors, shapes, and sizes for larger numbers of people. An interesting art that developed in the fourth century was the striking depiction of minor scenes and portraits by engraving glass with gold leaf, often on the bottoms of bowls or dishes or on round medallions.

Architecture

Diocletian and the tetrarchs revived the Severan policy of constructing massive public buildings and palaces to celebrate their power and the restored Empire. Diocletian’s baths in Rome were the biggest ever constructed. Today, Michelangelo’s great church of Santa Maria degli Angeli occupies only the central hall, whereas much of the rest is occupied by the Museo Nazionale Romano delle Terme. The only other Diocletianic building of note in Rome is the small senate house that he built on the site of earlier senate houses in the Forum.

Diocletian poured much money into construction at Nicomedia, his imperial residence in the East, and at his great fortified retirement palace on the Dalmatian Coast at Split (Spalatum, Spalato). The latter was laid out like a great military camp surrounded by thick walls between square towers. In the middle of the three landward walls were gates fortified with projecting octagonal towers. They entered onto colonnaded streets corresponding to the cardo and decumanus of Roman camps and planned towns. The walls enclosed almost eight acres containing not only the living quarters along the seaward wall but also barracks, exercise grounds, a temple, and an octagonal mausoleum.

Maximian expanded Milan (Mediolanum) for his imperial residence, and Galerius built up Thessalonica for his. Little survives at Milan, but part of Galerius’ complex survives at Thessalonica. His triumphal arch with its marble reliefs was really a four-sided gateway. There, the colonnaded road leading to his palace from his mausoleum intersected with a colonnaded section of the Via Egnatia, the main military road from Italy to the East. The palace has totally disappeared, but the round, domed mausoleum, which is reminiscent of the Pantheon, survives as the church of St. George. In Rome, Constantine restored monuments such as the Circus Maximus and built new ones such as the triumphal arch that bears his name. He also finished the huge basilica begun by Maxentius. Three of its six massive side vaults still soar 114 feet into the air. Originally, a vaulted clerestory rose another 40 feet above them. It covered an area approximately 350 feet by 220 feet and housed the colossal seated statue of Constantine (p. 642, Figure 2) in an apse projecting off the back. Both he and his mother, Helena, also built large baths for the people of Rome.

Constantine continued the tradition of round or polygonal buildings like the mausolea of Augustus, Hadrian, Diocletian, and Galerius. His mother was buried in the round mausoleum originally built for himself near the Via Casilina. The octagonal baptistry built for his original cathedral of St. John Lateran still survives. The round mausoleum of his daughter Constantina (Constantia) was built about ten years after his death and is now the church of Santa Costanza.

Constantine spent much money on construction and reconstruction in Italy, North Africa, and along the Rhine frontier in Gaul. Of course, his greatest concentrated program of public construction was at Constantinople. Unfortunately, nothing of it remains there. It has all been replaced by centuries of later building. The remains of his work in Gaul, however, are significant for the development of medieval Western architecture. The crenelated walls and round towers of his great fortified camp at Divitia (Deutz) across the Rhine from Cologne (Colonia Agrippina) even look like the bailey of a medieval castle. The buildings that he built for his imperial residence at Augusta Treverorum (Trier, Trèves) in Gaul foreshadowed the Romanesque architecture of early medieval Europe. Their style is discernible from the ruins of his great baths and from the large audience hall of his palace, which still survives as a Lutheran church.

Constantine’s most notable contribution to architecture was his program of building impressive Christian churches all over the Empire, not just in Constantinople. The amount of money, men, and material mobilized for this effort was enormous. Constantine himself gave personal attention to the choice of architects and designs. At Rome alone, he sponsored the building of two major churches inside the walls and at least a half dozen at the sites of major martyr cults outside the walls. The first of Constantine’s churches was the great cathedral of St. John Lateran, built inside the walls on the site of the former Lateran palace. St. Peter’s Basilica was the last and greatest of Constantine’s Roman churches. It was located across the Tiber on the slope of the Vatican Hill where an ancient tradition said St. Peter was buried. Begun around 332, it took over sixty years to complete. Although it was razed to make way for the present St. Peter’s in the late fifteenth century, pictures and descriptions survive.

At Antioch, Constantine began a great octagonal church surmounted by a gilded dome. It was located on an island in the middle of the Orontes River. Subsidiary buildings and courtyards surrounded it, and it was connected to the imperial palace. Many other cities, like Tyre and Nicomedia, received major churches, but Jerusalem and the Holy Land, of all places besides Rome and its vicinity, benefited most from Constantine’s church-building activities. Constantine’s mother, Helena, went to Jerusalem on a pilgrimage in 326 to identify the sites associated with Christ’s birth, crucifixion, resurrection, and ascension. Constantine then supported the building of major churches at these sites. By 333, in amazingly short order, four basilica churches had been completed.

Pagan temples, particularly in the countryside, continued to be built or rebuilt throughout the fourth century despite the lack of imperial patronage. The revived prosperity of cities in the East prompted the restoration of many temples and other public buildings as well as the construction of some new ones. Valens, for example, gave Antioch a new forum, and a proconsul restored a temple dedicated to Hadrian at Ephesus. Large lavishly decorated villa complexes sprouted up all over the Empire.

After the reign of Julian, however, the pace of building slowed for the rest of the fourth century. Unfortunately, Theodosius’ strictures against paganism led to the destruction of a significant portion of the Empire’s architectural heritage because of the zealous destruction of pagan temples by increasingly militant Christians. Nevertheless, the eventual conversion of some major pagan temples such as the Pantheon at Rome and the Parthenon at Athens to Christian churches preserved a few great monuments of Classical architecture. They symbolize the way in which Christianity and Classical culture creatively interacted during the late Empire despite the tensions that also existed. Although Christianity became more dominant and more intolerant from Theodosius onward, it could not eliminate or escape the cultural context that shaped it.

FIGURE 34.7 Christian Rome.

Suggested reading

Elsner, J. Imperial Rome and Christian Triumph: The Art of the Roman Empire A.D. 100–450. Oxford History of Art. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998.

Grubbs , J. E. Law and Family in Late Antiquity: The Emperor Constantine’s Marriage Legislation. Oxford and New York: Clarendon Press, 1995.

MacMullen , R. The Second Church: Popular Christianity A.D. 200–400. Atlanta: Society of Biblical Literature, 2009.

Watts , E. J. The Final Pagan Generation. Transformation of the Classical Heritage, 53. Oakland: University of California Press, 2015.