At this time, A. D. 62-3, the reigning Emperor was the infamous Nero, one of the strangest and most incomprehensible tyrants who has ever occupied a perfectly irresponsible position of well nigh boundless authority. The pitiful historian, in attempting the impossible task of explaining the growth and development of the character of this inhuman master of the world, dwells on the foolish partiality of his evil mother, who through a series of bloody intrigues gained at last the Imperial purple for her beautiful boy.

This mother, Agrippina, is painted by Tacitus in the darkest colors, as a woman of daring schemes, of reckless cruelty, a princess who suffered no scruple ever to stand in the way of her merciless and shameless intrigues. Nero was but seventeen years old when, thanks to her successful plotting, he became the uncontrolled master of the world. Bent on selfish pleasure, he regarded his mighty empire as existing only to supply material for his evil passions. As years passed he grew more cruel, more vain. In the gratification of his passions and lusts he spared none; his mother, his wife, his intimate friends and companions, some of them the noblest by birth and fortune of the Roman patricians, were all in turn murdered by his orders. To his disordered fancy, the circus, with its games—games, many of them of the most degraded character, cruel, bloody, pandering to the lowest passions of the people—were the center of Roman life. The whole world he looked on as only existing to minister to the evil pleasures of Rome. For several years he was adored by the mixed crowds of various nationalities which composed the people of the Queen City; these irresponsible masses rejoiced in the wicked tyrant who from day-to-day amused them by the strange and wonderful spectacles of the circus and the amphitheatre. The populace loved him, the soldiers of the all-powerful Praetorian guard, whom he flattered, bribed, and cajoled, for a long period supported and upheld him. For his treachery, cruelty, and faithlessness affected the mercenary-soldiers and the populace but little. It was only the great, the rich, the noble who trembled for their lives. The irresponsible mass of the people, the hireling Praetorian guards, delighted in a master who made their lives a perpetual holiday, who amused them with spectacles that in the world had never been matched before, so brilliant, so attractive, but of a character calculated only to debase and to lower the ignorant crowds who thronged the vast theatres where the marvelous and awful games were played. Often as many as fifty thousand, or even more, of this degraded populace would assemble in one of the great circus buildings to look, hour after hour, on scenes where cruelty, obscenity, and vice were idealized; at times the lord of the Romans deigned to join in the shameful sports, as charioteer, as singer, as buffoon, and would receive with gratification the noisy and tumultuous applause of the delighted thousands who hailed him as Emperor, and even worshipped him as divine.

Under Nero the whole tone of Roman society, from its apex down to the lowest ranks, was corrupted. The terms been heedlessly squandered, and darker and ever darker expedients to replenish an exhausted exchequer were resorted to;—that the cup of wickedness of the Emperor Nero was tilled, the legions of the provinces revolted, and the tyrant found himself, even in the Rome which he had so basely flattered and corrupted, without a friend. Then the end came, and Nero escaped the penalty of his nameless crimes by self-murder; but even the supreme hour of the infamous Emperor was marred by cowardice and unmanly fear.

It was in the July of the year 64, a memorable date never forgotten, that the terrible fire broke out which reduced more than half of Rome to ashes; it began among the shops filled with wares, which easily fell a prey to the flames, located in the immediate neighborhood of the great circus hard by the Palatine Hill. For six days and seven nights the fire raged; whole districts filled with the wooden houses of the poorer inhabitants of the city were swept away; but besides these, numberless palaces and important buildings were consumed.

Of the fourteen regions of Old Rome, four only remained uninjured by the flames. Three were utterly destroyed, while the other seven were filled with wreckage, with the blackened walls of houses which had been burnt; but the irreparable loss to the Roman people after all was the utter destruction of those more precious monuments of their past glorious history, on which every true Roman was accustomed to gaze with patriotic veneration. The cruel flames spared few indeed of these. When the fire gradually, after the dread week, died away, only blackened, shapeless rums stood on the immemorial sites of the Temple of Luna, the work of Servius Tullius, the Ara Maxima, which the Arcadian Evander had raised in honor of Hercules, the ancient Temple of Jupiter Stator, originally built after the vow of Romulus; the little royal home of Numa Pompilius, the houses of the ancient captains and generals, adorned with the spoils of conquered peoples, indeed well nigh all that the reverent love of the great people held dear and precious, had disappeared in this awful calamity. Such a loss was simply irreparable. Rome might be rebuilt on a grand scale, but the old Rome of the kings and the Republic was gone forever.

The darkest suspicions were entertained as to the mysterious origin of this overwhelming calamity. Men's thoughts naturally were turned to the half insane master of the Roman world; was ho not the author of the tremendous fire? It was known that he had for a long time viewed with dislike the tortuous, narrow streets, the piles of squalid, ancient buildings which formed so large a portion of the metropolis of the Empire; that he had formed plans of a great reconstruction, on a vastly enlarged scale, of the mighty capital; that he had dreamed of the new, enormous palace surrounded by immense gardens and pleasantries, which soon arose under the historic name of "Nero's Golden House." Had not the evil dreamer, who exercised such irresponsible power in the Roman world, chosen this method, sudden, sharp, and swift, of clearing away old Rome, and thus making room for the carrying out of his grandiose conceptions of the new capital of the world? The truth of this will never be known. Serious historians chronicle the suspicions which filled men's minds; they tell us how the marvelous popularity which the wicked Emperor had hitherto enjoyed among the masses of the people was gravely shaken by the tremendous calamity of which he was more than suspected to have been the author. All kinds of sinister rumors were in the air; it was said no stringent and effective measures had been adopted by the Government to stay the progress of the flames. Men even said that the Emperor's slaves had been detected with torches and inflammable material helping to spread the fire. The only plea that the friends of Nero were able to advance when that dark accusation gathered strength and force was that when the fire broke out the Emperor was at Antium, far away from Rome, and that he only arrived on the scene of desolation on the third day of the great fire.

At all events, when all was over Nero found himself generally suspected as the author of the tremendous national calamity. It was in vain that he provided temporary dwellings for the tens of thousands of the homeless and ruined poor; that he threw open the Campus Martins and even his own vast gardens for them, erecting temporary shelter for them to lodge in, supplying these homeless ones at a nominal cost with food. All these measures were of no avail—the Emperor, so lately the idol of the masses, as we have said, found himself at once unpopular, even hated, as the contriver of the awful crime.

It was then that the dark mind of Nero conceived the idea of diverting the suspicions of the people from himself, and of throwing the burden of the crime upon others who would be powerless to defend themselves. His police pretended that they had discovered that the Christian sect had fired Rome.

What now were his reasons for fixing upon this harmless, innocent, comparatively speaking little known group of Christians as his scapegoat? What induced the bloody, half-insane tyrant to choose out the poor Christian community for his, shameful, cowardly purpose, and to accuse such a loyal, quiet, peace-loving company of the awful crime which had resulted in the destruction of more than half the' metropolis of the world? What had they done to excite his wrath? Never a word had been uttered by the leaders of the Christian sect which could be construed into treason against himself or even into discontent with the Imperial Government. For the Christian sect all through the ages of

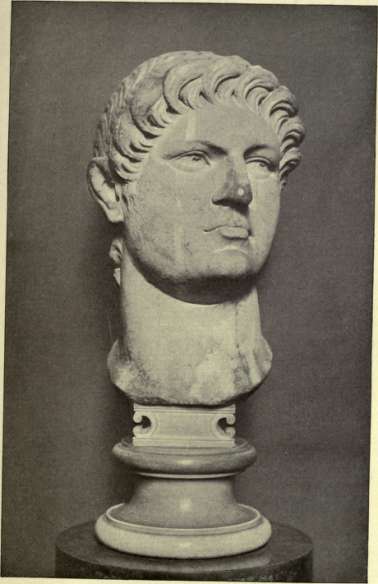

NERO. From a Bast found at Athens, now in the British Museum.

persecution were not only a peace-loving body — they remained ever among the most loyal subjects of the Pagan Emperor who proscribed the religion they loved better than life, and who allowed them to be done to death unless they chose to purchase life by denying the "Name" they believed in with so intense a faith. From the days of Nero in the 'sixties to the days of Diocletian, when the sands of the third century were fast running out, the loyalty of the Christians was never called in question. In their ranks no conspirator against the laws and Government of the Empire was ever known to exist.

It was so from the first. In what we may term the State papers, which contain undoubtedly the official pronouncements of the honored chiefs of the earliest Christian communities—Peter, Paul, and John—we find the most solemn charges to the believers under all circumstances to maintain a strict, unswerving loyalty to the Caesar, and to the Roman Government of which the Caesar was the representative. The charges are even peremptory in their directness. So Paul wrote to the brethren at Rome from Corinth in the year 58:

"Let every soul be subject unto the higher powers . . . the powers that be are ordained of God. Whosoever therefore resisteth the power resisteth the ordinance of God, and they that resist shall receive to themselves damnation. For rulers are not a terror to good works, but to the evil ... He beareth not the sword in vain, for he is the minister of God, a revenger to execute wrath upon him that doeth evil. Wherefor ye must needs be subject . . . also for conscience' sake . . . Render therefore to all their dues, tribute to whom tribute is due; fear to whom fear; honor to whom honor."— Romans xiii. 1-7.

In truth a very noble definition of authority, a sublime ideal of loyalty, was thus set before the little congregations of the rising sect. So Peter, too, in his first epistle—an epistle received with respect and reverence in all the Churches as an inspired pronouncement from the very beginning—writing from Rome, under the shadow of that fearful persecution we are going to relate in detail, repeats with even greater emphasis his brother Paul's directions:

"Dearly beloved . . . submit yourselves to every ordinance of man for the Lord's sake, whether it be to the king as supreme, or unto governors as unto them that are sent by him for the punishment of evil doers, and for the praise of them that do well: for so is the will of God, that with well-doing ye may put to silence the ignorance of foolish men; as free, but not using your liberty for a cloke of maliciousness, but as the servants of God. honor all men. Love the brotherhood. Fear God. honor the king."—1 Peter ii. 13-17.

What Paul wrote in a period of comparative quietness in A. D. 58, Peter repeats a few years later, circa A. D. 65-6, in the days of one of the most cruel persecutions that perhaps ever weighed upon the Church; while John, who, after Peter and Paul had passed away, somewhere about A. D. 67-8, was regarded by the Church as its most honored and influential leader, in his Gospel—probably put out in the latter years of the first century—when giving the account of the trial of Jesus Christ before Pilate, quotes one of the sayings of his Master addressed to the Roman magistrate; in which the Lord clearly states that the power of the Imperial ruler was given him from above—that is, from God (John xix. 11); thus emphasizing, some quarter of a century later, the words and charges of Peter and Paul, ordering the Christian communities to be loyal and obedient to the constituted powers of the State, and to the Sovereign who wielded this authority as the chief officer of the State, because such powers were given "from above."

This spirit of unswerving obedience and perfect loyalty which we find in the official writings of Peter, Paul, and John, lived in the Church all through the three centuries of the oppression. It was ever its guiding principle of action in all its relations with the Empire.

Thus we come again to the question: What then provoked the first cruel persecution? What determined Nero to proscribe so loyal and harmless a sect? It has been suggested, nor is the suggestion by any means baseless, that the proscription of the Christians by the Emperor was in consequence of a dark accusation thrown out by the Jews. Not improbably the first idea of Nero and his advisers was to fasten the crime upon the Jews themselves. Their loyalty to the State was ever questionable. The condition of the Hebrew mother-country was just then restless and uneasy. The threatenings of the great revolt, which culminated in the Jewish war and destruction of Jerusalem in A. D. 70, were already plainly manifest. It is indeed highly probable that to avert the suspicion of many a Roman who too readily looked on the Jewish colony as the authors of the great calamity, the Jews themselves suggested to the Emperor that in the hated Christian sect he would find the true authors of the fire of Rome. Nor were the Jews without friends at Court, who were able and willing to press home the false and evil accusation. Poppsea, the beautiful Empress, at that time high in the favor of Nero, who had taken her from her husband, was deeply interested in the Hebrew religion; some even think she had absolutely joined the ranks of the chosen people and had become a "Proselyte of the Gate." Other friends, too, of the Jews, besides the profligate Empress, were in the inner circle of Nero.

But still the historian of Christianity is loth to charge the Jews with this crime of a false accusation, which led in the case of the Christians to such fearful consequences. It is possible, certainly, that other reasons may have induced Nero to turn his thoughts to the followers of Jesus of Nazareth. In the year 64 it is clear that they were no secret or inconsiderable community, and it is likely that they were already looked upon by many of the superstitious and jealous Romans with dislike and even with hatred. Christianity was beginning to make rapid progress. Its votaries, while loyal to the State and the magistrates, made no secret of their dislike and contempt for the Deities whose shrines were the object of such intense veneration. These considerations would at least suggest to Nero that in this sect he would easily find an object of popular hatred.

The Imperial order went forth. It was about the middle of the year 64. The first martyrology of the Church was written by no fervid Christian, by no ecclesiastical historian living years after the dread events happened of which he was the perhaps partial chronicler; it was compiled by no admirer of martyrdom, too anxious it may be to draw a great lesson, and to point to a noble example of faith and fortitude. The teller of the story of the martyrs of Nero was a Roman, a Pagan, a scholarly and eloquent admirer of Rome and of her immemorial traditions; and withal one who lived only a little more than half a century after the date at which the memorable events he related took place. No one certainly can suspect the Pagan historian Tacitus of exaggeration. He tells the story with his usual cold brilliancy of style; but no one can charge him with undue partiality for the sufferers whose fate he so graphically depicts. In his eyes the hapless victims deserved the severest punishment, though even for them, guilty though they were, the punishment meted out was perhaps too cruel, the sufferings excessive. They excited pity, Tacitus tells us; the horrors which accompanied their punishment gave rise to a suspicion that this great multitude of condemned ones who died thus were rather the victims of the cruelty of an individual (Nero) than merely ordinary offenders against the State.

The result of Nero's proscription was the immediate arrest of many prominent and well-known members of the Christian community. These, Tacitus says, confessed; but their confession was evidently not their share in the burning of Rome, not that they had been incendiaries, but simply that they were Christians; for the huge multitude of Christians who, as the investigation of the Government broadened out, were subsequently arrested, were presently convicted on the general charge, not of firing the great city, but simply of "hatred against mankind." The procedure seems to have been terribly simple. Nero, intensely anxious to divert from himself the indignation which it was evident had been universally aroused against him as the author of the conflagration which had destroyed a great part of Rome, and particularly its cherished monuments of the past, used for his purpose the popular dislike of the new sect of Christians.

Many were sought out. They were well known and easily found. They at once confessed that they were Christians. Then on the information elicited at their trial, perhaps too on the evidence of writings and papers seized in their houses, many more were involved in their fate. All pretence of their connection with the late tremendous fire was probably soon abandoned, and they were condemned simply on their confession that they were Christians. Their punishment was turned into an amusement to divert the general populace, and thus Nero thought he would regain some of his lost popularity. His fiendish desire no doubt was partly successful. For the games were on a stupendous scale, and were accompanied by scenes hitherto unknown even to the pleasure-loving crowd accustomed to applaud these cruel and degrading spectacles.

The scene of this theatrical massacre was the Imperial garden on the other side of the Tiber, on the Vatican Hill. The spot is well known, and is now occupied by the mighty pile of St. Peter's, the Vatican Palace, and the great square immediately in front of the chief Church of Christendom and the vast palace of the Popes.

Whether the awful and bloody drama in the Vatican Gardens lasted more than one day is not made certain by the brief though graphic picture of Tacitus. Enormous destruction of human life, we know from other "amphitheatre" recitals, could be compassed in a long day's proceedings, especially under an Emperor like Nero, who had all the resources of the Roman world at his disposition.

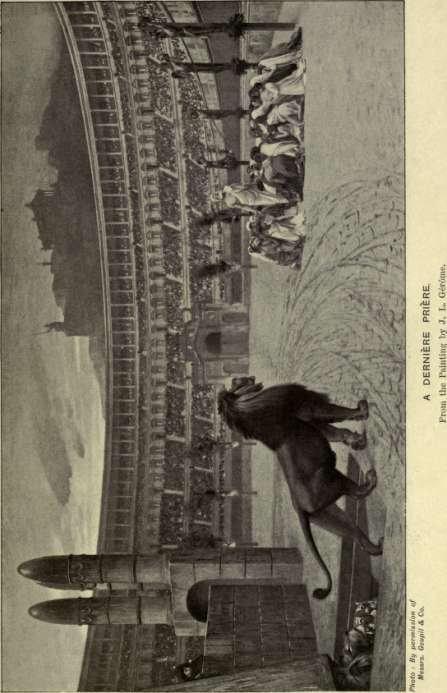

If the whole were comprised, as seems probable, in one day's long performance, it is clear that the hideous games were prolonged far into night. It began with a long and pathetic procession of the condemned, made up of all ages and of both sexes, round the great amphitheatre erected and enlarged for the show. This was followed by the "Venatio" or hunting scene, a spectacle in which wild beasts—lions, tigers, wild bulls, wolves, and dogs—bore a prominent part; to add to the horrors of the scene, some of the victims would be partially clothed in skins of different animals, to whet the ferocity of the dogs and other beasts specially trained for fighting. By a strange refinement of cruelty, the Roman mob in the course of these savage games was regaled with some dramatic spectacles, the scenery of which was drawn from well-known mythological legends. A Hercules was carried to the funeral pyre and then burnt alive, amid the frantic applause of the spectators; an Icarus was made to fly, and then fall and be dashed to death. The hand of a Mutius Scaevola was held in the burning brazier till the limb of the tortured sufferer was consumed; a Pasiphae was gored by a bull; a Prometheus was chained to the rock where he underwent his terrible punishment; a Marsyas was flayed alive; an Ixion was tortured on his wheel; an Actaeon was actually torn by his dogs. This dread realism formed part of the cruel amusements of Nero's show in his Vatican Gardens. To these pieces of real sorrowful tragedy were added on this occasion other scenes out of the legendary history of the past, so degrading and demoralizing that the historian must pass them over in silence. At last, night threw its pitiful veil over the bloodstained arena. During the long hours of the Italian summer day, the fierce, excited multitude, numbering many thousands, had been gazing on these unheard-of tortures, and watching the dying agonies of the crowd of the first Christian martyrs of various ranks and orders, slaves and freedmen, soldiers and traders, mostly poor folk, but here and there one of higher rank and standing,

Clement of Rome, writing some few years after the "dread stow," parts of which he probably witnessed, tells us how " unto these men of holy lives was gathered a vast multitude of the elect, who, through many indignities and tortures, being the victims of jealousy, set a brave example among ourselves . . . Women being persecuted after they had suffered cruel and unholy insults . . . safely reached the goal in the race of Faith, and received a noble reward, feeble though they were in body."—S. Clement of Rome: Upist. to Cor. 6.

some old men, others in the prime and vigor of life, tender girls, women of varied ages, some even children in years; but all, as it seems, enduring the nameless agonies with calm, brave patience, asking for no mercy, offering no recantation of their faith in the Name for which they were suffering, some even smiling in their pain. . . . But the night which followed that August day, so memorable in the Christian annals, brought in its train no merciful silence into the grim garden of death and horror, where Nero was entertaining his Roman people. The games still went on, but the spectacle on which the crowds were invited to gaze was changed. The broad arena was strewn with fresh sand, blotting out the dark stains left by the long-drawn-out tragedy of the day. Perfumes were plentifully sprinkled to freshen the heavy, blood-poisoned atmosphere, and the arena was lit up for the concluding acts of the Imperial drama. Here, however, the Emperor had devised a new and original spectacle to delight the fierce crowd whose applause he so loved to evoke. The principal amusement of the night was to consist in chariot racing, in which the Lord of the World himself was to bear a leading part; for Nero was a skilful and courageous charioteer, and it was his habit now and again to show himself in this guise to his people, coming down from his gold and ivory throne into the arena. And as the torches, plentifully scattered on that vast arena, gradually flamed up, the bystanders were amazed, and it seems from Tacitus' words, were even struck with horror at the sight, and for the first time in that day of death and carnage, pitied as they gazed; for every torch was a human being, impaled or crucified on a sharp stake or cross. The "torches" quickly flared up, for every human form was swathed in a tunic steeped in oil, or in some inflammable liquid. Such was the ghastly illumination of the arena on that never-to-be-forgotten night of the late summer of the year 64, when the chariot races were run. It was a novel form of lighting the amphitheatre, and we have no record that it was ever repeated. It seems to have been too shocking even for that demoralized and bloodthirsty populace, whose chief delight, whose supreme pleasure, was in those sanguinary and impure spectacles so often provided for the people by the Emperors of the first, second, and third centuries.

The number of victims sacrificed in this persecution of Nero is uncertain; it was undoubtedly very large. Clement of Rome, writing before the close of the first century, describes them as "a great multitude." Tacitus, a very few years later, uses a similar expression (ingens multitibdo); and when it is remembered what vast numbers on different occasions were devoted to the public butcheries in the arena for the amusement of the populace, it may be assumed without exaggeration that the Christian victims who were massacred at that ghastly festival we have been describing probably numbered many hundreds.