In 1837 Major Henry Creswicke Rawlinson, then in the employ of the Persian War Ministry, was lowered, with the help of block and tackle, down the face of a high cliff near Behistun. His purpose was to copy some inscriptions hewn into the rock. He is the second diplomat to combine Assyriology with professional political and worldly interests.

Rawlinson’s career was as adventurous as Grotefend’s was conventional. The seed of his interest in Old Persian was sown by a chance acquaintance. When seventeen, Rawlinson was a cadet aboard a vessel bound around Cape Horn for India. To relieve the monotony of the long months of the voyage, he edited and published a ship’s paper. One of the passengers, Sir John Malcolm, Governor of Bombay and prominent Orientalist, was much taken by the wide-awake seventeen-year-old soldier editor. He engaged the boy in long conversations, which naturally were dominated by Sir Malcolm’s main interest. The Governor of Bombay was a passionate student of Persian history, language, and literature. These talks were to influence Rawlinson’s avocational interest until the end of his days.

Born in 1810, Rawlinson entered the military service of the East India Company in 1826, and by 1833 was a major on duty in Persia. The year 1839 saw him employed as political agent in Kandahar, Afghanistan. By 1843 he had become British consul in Baghdad, and by 1851 consul-general with the military rank of lieutenant-colonel. In 1856 he returned to England, was elected to Parliament, and in the same year appointed to the board of the East India Company. In 1859 he became British Minister to the Persian court at Teheran. From 1865 to 1868 he was again a member of Parliament.

When he first took up the study of cuneiform writing he used the same tablets that Burnouf had worked with. An amazing thing now came to pass. In complete unwareness of Grotefend’s, Burnouf’s, and Lassen’s contributions, he deciphered, by a method very similar to Grotefend’s, the names of the three Persian kings that in English are written Darayawaush (Darius), Khshayarsha, and Vishtaspa. Beyond this he deciphered four other names, and some words as well, though he was not sure about the last. When, in 1836, he discovered Grotefend’s writings, comparison revealed that in many significant respects he had improved on the schoolmaster of Göttingen. Now he needed more inscriptions, with names and still more names.

Since time immemorial a steep, double-peaked, cliffy mountain has dominated the land of Bagistana, “landscape of the gods,” and the ancient road, passing by its foot, from Hamadan to Babylon by way of Khermansha. Here, about twenty-five hundred years ago, Darius, King of the Persians—Darayawaush, Dorejawosch, Dara, Darab, Dareios are variation of his name in different languages—had reliefs and inscriptions carved in the cliff face in celebration of his own person, deeds, and victories. This memorial stands some 160 feet above the valley floor.

On a great beam of stone are carved large figures that stand out boldly from the cliff. Here, poised in the glittering air, the great Darius is shown leaning on his bow, his right foot placed on the prostrate Gaumata, the magician, who had incited the kingdom to rebellion. Behind the King stand two Persian nobles, with bows, quivers, and lances. Before him, their feet bound, ropes at their necks, cower the nine “kings of lies,” now brought to heel. At the sides and beneath this monument are fourteen columns of writing, recording, in three different languages, the accomplishments of Darius. Grotefend had recognized the bare fact that there were three variations of the cuneiform script at Behistun, but of course lacked the means to identify them for what they were—Old Persian, Elamite, and Babylonian. Among the records that Darius caused to be chiseled in the solid rock for the edification of posterity was an announcement that ran as follows:

King Darayawaush gives notice thus:

You who in future days

Will see this inscription by order

Writ with hammer upon the cliff,

Who will see these human figures here—

Efface, destroy nothing.

Take care, so long as you have seed,

To leave them undisturbed.

Dangling from the rope secured above, Rawlinson copied down the Old Persian version of the writing. It was only some years later that he tackled the Babylonian version, an operation that required enormous ladders, long cables, and hooks, equipment hard to come by in the Middle East. Despite these difficulties, in 1846 he laid the first exact copy of the famous inscription before the Royal Asiatic Society, and a complete translation with it. It was the first great British triumph of Assyriological decipherment.

Meanwhile other scholars had not been idle. The Franco-German Oppert and the Englishman Hincks in particular had made important advances. Comparative linguistics had proved especially effective in making use of the increasingly exact knowledge of Zend and Sanskrit—indeed, of the whole Indo-European family of languages—to clarify the grammatical structure of Old Persian. By a cooperative effort of truly international scope, sixty characters of the Old Persian cuneiform writing were gradually identified.

By this time, however, Rawlinson and others had got well into the study of the Behistun inscriptions, which provided a much greater range of material than had obtained heretofore. Rawlinson made a discovery that seemed to deal a severe blow to the hope of attaining a complete cryptology of the ancient languages of the Middle East, in particular of the inscriptional specimens collected by Botta.

As we recall, the Persepolitan and Behistun inscriptions were in three different languages. Grotefend had levered some meaning from them at a point of least resistance, where the cuneiform words were closest in time to their counterparts in known languages. The most vulnerable part of the inscription, the part, that is, on which Grotefend had concentrated, was the middle column. Even before Grotefend’s time the type of cuneiform characters found in the middle column had been designated as Class I.

Most of the problems of Class I writing having been solved, the cryptologists turned to the other two types. The credit for laying the foundation of a method for deciphering the cuneiform writing of Class II belongs to the Dane Niels Westergaard, whose results were first published in Copenhagen in 1854. And the honor of deciphering Class III must be divided between Oppert and Rawlinson, the latter at this time consul-general at Baghdad.

The analysis of Class III quickly revealed a disturbing discovery. Class I was an alphabetical script in which, as in European writing, each sign equaled a sound. Not so in Class III script. Here a single sign might stand for a syllable, again for a whole word. Even worse, there were instances—and these multiplied as time went on—where the same sign, or polyphone, might represent several different syllables, or even several different words. Conversely, several signs, or homophones, could be used to express the same word. Eventually it was clearly established that changeability of meaning was the rule in the script of Class III. Total confusion reigned.

At first no one had the least idea how to go about cutting a path through this thicket of multiple meanings. And as these disenchanting revelations were published—especially by Rawlinson—there was great excitement among the scholars, and a storm of anger among the laity. The experts, of course, never entirely discounted the possibility that the characters might sometime become readable. Professionals and nonprofessionals engaged in heated arguments. Were they seriously expected to believe—authors known and unknown, specialists and laymen, asked in the scientific and literary supplements—that writing so hopelessly confused could ever have been actually used for purposes of communication? Were they expected, moreover, to swallow assurances that such a hodge-podge would sometime be read? There were loud protests; the experts were vigorously bludgeoned. Rawlinson in particular was raked over the coals for playing “unscientific jokes.” Desist, he was warned.

A simple example—taken out of its context, which is too complicated to reproduce here—will serve to show just how maddening this Class III script could be. The sound r was expressed by six different signs, according to whether the intent was to indicate the syllables ra, ri, ru, ar, ir, or ur. But supposing one wished to reproduce the sound ram, or mar—that is, to add a consonant to ra, or ar—then an entirely new ideogram resulted from the new phonetic situation. Moreover, the pronunciation of the new ideogram could not be deduced from its component parts. In sum, the ambiguity of the script rested on the fact that when several signs were united into one ideogrammatic group to express something, the pronunciation of the whole could not be derived from the pronunciation of the constituent single signs. For example, the Class III group of characters for the name of the famous King Nebuchadnezzar (Nebuchadrezzar), if pronounced according to the discrete phonetic values, would be An-pa-sa-du-sis. But in actual fact the name was pronounced Nebukudurriussur.

About this time, when to the uninformed the muddle seemed complete, at Kuyunjik, where Botta had excavated, nearly a hundred clay tablets were found in rapid succession. These tablets, later identified as dating back to around the middle of the seventh centuryB.C., might have been deliberately designed as aids to the scholars of posterity, for they contained long listings in which the different phonetic values and meanings of the ideogrammatic script were correlated with those of the alphabetical script.

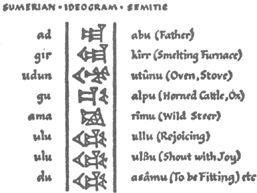

This was a tremendously important find. The cryptologists now had “dictionaries” to work with! The comparative listings had evidently served the beginner studying cuneiform writing at a time when the older pictographic and syllabary scripts were becoming simplified into an alphabetic version. Gradually whole “instruction manuals” and “dictionaries” were pieced together from the tablets. In the dictionaries the Sumerian name was given with its Semitic equivalent. Finally a prototype of the encyclopedic dictionary was discovered, containing pictures of various objects arranged in rows, these—at least the ones used in religious and legal rites—labeled with their Sumerian and Semitic names.

This example gives some idea of the syllabaries, or signaries, used by students of cuneiform writing in the seventh century B.C. These syllabaries were found at Kuyunjik. A device that once benefited the student, more than two thousand years later helped the Assyriologist decipher cuneiform texts.

But important as this find was, it was still too fragmentary to provide more than a good toehold. Only the specialist can appreciate the difficulties, the roundabout paths and culs-de-sac that had to be laboriously explored before the cryptologists were able to read any cuneiform inscription, however complicated or ambiguous.

When Rawlinson issued a public claim that he could read the most difficult of the cuneiform scripts—like all great intellectual pioneers he was constantly beset and reviled—the Royal Asiatic Society in London did something seldom or never heard of in the history of scholarship.

To the four greatest cuneiform experts of the day—unknown to each of the others—the society sent a sealed envelope containing a newly discovered, lengthy Assyrian inscription, with a note urgently requesting its decipherment.

The four experts were Rawlinson, Talbot, Hincks, and Oppert. All went to work on the project about the same time, none knowing about the others, and each working according to his private methods. Finally all four returned their results in sealed envelopes, whereupon a commission examined the texts. The claims that had been so vociferously scoffed at by the public were brilliantly vindicated; it was definitely possible to read this supremely complicated syllabic writing. For all four texts agreed on essential points.

Many Assyriologists undoubtedly resented this extraordinary experiment and felt they had been grossly duped. Such a method of checking, they felt, was beneath science, however much the laity might approve.

No matter; in 1857 in London appeared An Inscription by Tiglath-Pileser, King of Assyria, translated by Rawlinson, Talbot, Dr. Hincks, and Oppert. There could not have been a more convincing proof of the scientific accuracy of the results, even though a diversity of approaches over paths heavily strewn with obstacles had been used.

Assyriology continued to develop apace. Ten years later the first elementary grammar of the Assyrian language appeared. Presently scholars undertook to unravel the mysteries of the spoken tongue. Today countless students are able to read cuneiform writing. Imperfectly inscribed or incomplete tablets pose the only difficulties, and of course material defects can be expected after three thousand years of wind and rain and sun beating on the ancient clay.