![]()

![]()

AT FIRST THERE WAS only a small cloud on the horizon. There was a growing sense of fear, as though everyone knew that disasters were fast approaching, but no one knew from which direction they would come. Moscow was suffering from famine, the July massacres on the Red Square were still vividly remembered, and Ivan was still issuing commands from the guarded seclusion of his palace at Alexandrova Sloboda. Nothing more was being heard about Prince Magnus’s elevation to the throne, and it appeared that the Tsarevich was in the Tsar’s good favor and therefore Prince Magnus was unlikely to be his successor. The threat to uproot and then trample the Russian people underfoot was not being carried out, but the people were too exhausted to care. The terrible Emperor was on the throne: lightning might strike out of a cloudless sky.

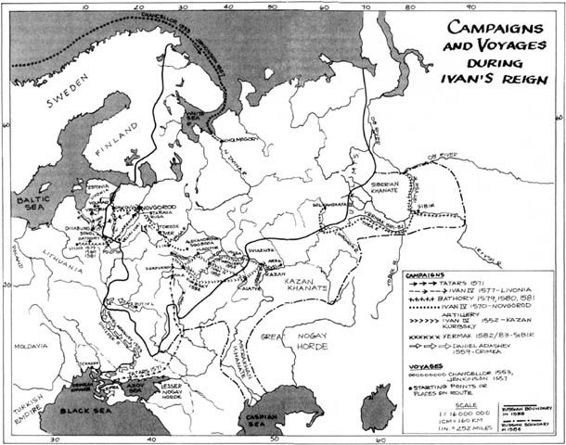

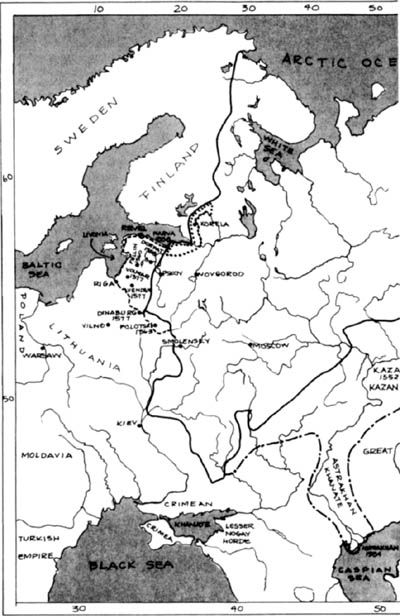

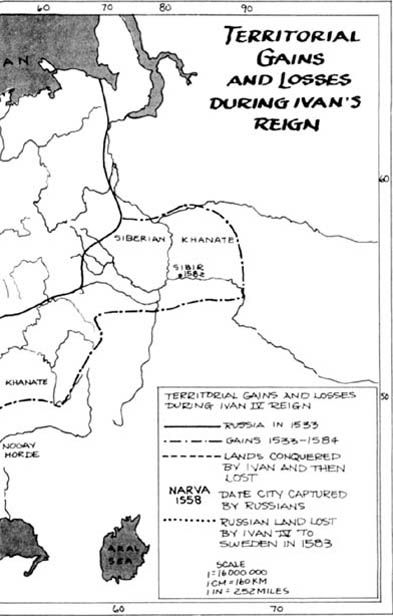

Early in September 1570 there came rumors that a large Tatar army was on the march. Since the Russians had ambassadors and agents in the various Tatar courts and usually knew in advance what they were up to, these rumors were treated seriously and Prince Ivan Belsky led an army to the Oka River. About ten days later, on September 16, Ivan himself set out from Alexandrova Sloboda at the head of an army of oprichniki, marching toward the fortress of Serpukhov, which lay on a tributary of the Oka River. Serpukhov was built of white stone and belonged to that chain of fortresses, mostly built of wood, which stretched along the Oka River and its tributaries. Kashira, Kaluga, Tarusa, Alexin, and Serpukhov were all minor fortresses compared to Kolomna, where the main army was concentrated. Russian territory extended far to the south, and beyond the Russian frontiers lay the dikoye pole, the wild plain, the no-man’s-land where the tribesmen wandered. When the Tatars drove up from the south they encountered no real opposition until they reached the Oka River. Now, as in previous years, their aim was not conquest but the capture of loot and young Russians to sell in the slave markets of Kaffa and Constantinople. If by chance they captured members of the Russian nobility, they were ransomed; and there existed a fixed scale of ransom payments according to their rank.

But once the Tsar arrived at Serpukhov, it became clear that this was not the large Tatar army which had been expected, but a scouting force of about 6,000 men. This small army arrived at the frontier town of Novosil, which belonged to Prince Mikhail Vorotynsky, and after pillaging the town the Tatars withdrew. The military commanders on the Oka River concluded that there was little danger of any further attacks that year, but for safety’s sake it was decided that the Zemshchina Army should retain its positions along the Oka River for two more weeks and that special efforts should be made to reinforce the southern defenses. Prince Vorotynsky was placed in charge of all the defense works, fortresses, guard posts, and scouting operations. He was chosen because he was an experienced general and also because he was the owner of vast estates on the southwest frontier and could therefore be expected to put his heart into defending the entire frontier. The decree, appointing him to this new position, was not signed until early the following year, but it is clear that he was given full powers by Ivan during his brief visit to Serpukhov. The decree mentions defense lines, guard posts, ramparts made of earth and balks of timber, and lookout posts deep in no-man’s-land. If the Tatars were going to invade Russia, the defense was in good hands.

Ivan spent only a few days in Serpukhov. On September 22 he returned to Alexandrova Sloboda.

What the Russians did not know until later was that the force of 6,000 men who reached as far north as Novosil had been sent to test the Russian defenses in advance of a massive attack that was being prepared by Devlet Guirey, the Khan of the Crimea, whoselast invasion had taken place in 1565. He was an old man suffering from the infirmities of old age. Two years earlier the Russian envoy to the Khan’s court reported that “the insides were falling out of him and sometimes he cannot sit on a horse and during the farewell audience he leaned back,” by which the envoy meant that he leaned back on the cushions and appeared to be exhausted. But the Khan was not so ill that he was incapable of organizing a vast army, leading it and inflicting terrible defeats on the Russians. It seemed to him and to all the enemies of Russia a good time to attack. Sultan Selim II, who attempted to capture Astrakhan in 1569 but failed miserably, was encouraging him. The Poles and Lithuanians were complaining that for the past three years the Tatars had inflicted no damage on Russia and therefore could not expect the customary gifts. Old as he was, the Khan decided to attack, with all the forces he could muster.

His army consisted of about 120,000 men, mostly from the Crimea but including recruits from the Great Nogay Horde, who roamed the steppes east of the Volga, and from the Lesser Nogay Horde, who were established on the shores of the Sea of Azov between the Don and the Kuban. There were other smaller detachments of Tatars and a contingent of Turkish soldiers. On April 5, 1571, the Khan led his two sons and his army across the narrow isthmus of Perekop, which joins the Crimea to the mainland, and marched north. His intention was to sack Moscow and put it to the flames.

On the journey across the steppes the Tatars encountered some Russian nobles who had fled from Russia to avoid execution. From them the Tatars learned that the Tsar was at Alexandrova Sloboda, that Moscow was suffering from famine, and that the bulk of the Russian forces were in Livonia. They advised the Khan to press on to Moscow. A certain Kudiyar Tishenkov, a member of the Russian provincial nobility, said he had heard that the Tsar was expected to arrive shortly at Serpukhov but his army was so small that it would provide no effective opposition. He offered to act as the guide of the Tatars, and when he saw that one of the Tatar captains distrusted him, he replied, “If you fail to reach Moscow, then you can impale me! There is nothing standing in your way!” Then two recently baptized Tatars were brought into the Khan’s presence and they too said that there was nothing to prevent him from arriving before the gates of Moscow. Accordingly it was decided to march on Moscow with Kudiyar Tishenkov acting as the guide.

Although the Russian envoy at the Khan’s court was able to send a message to Moscow with the warning that the Khan’s army had left Perekop and was advancing to the north, the news did not reach Ivan until too late. Suddenly the Tatars appeared at Tula, burned the town, and sped on toward Serpukhov. The Zemshchina forces on the Oka River consisted of about 50,000 men and were therefore heavily outnumbered by the enemy. The main army was stationed at Kolomna under Prince Ivan Belsky, the right wing was commanded by Prince Ivan Mstislavsky at Kashira, and the vanguard was at Serpukhov, where Prince Mikhail Vorotynsky had his headquarters. On May 16 Ivan set out with his oprichniki from Alexandrova Sloboda for Serpukhov, riding ahead with about 6,000 troops while the rest of his army, hastily organized, followed at a more leisurely pace. He knew that Tula had been attacked but did not know how large the Tatar armies were. He decided to pitch his camp some miles away from Serpukhov, and he was still in camp when he received one of the greatest shocks of his life, for he learned that a large Tatar army had crossed the Oka River and was only twenty miles away to the west.

Ivan was one of those men who find no difficulty in massacring defenseless civilians but he could not command armies, or fight, or show courage in adversity. He was inclined to lose his nerve whenever he was confronted with danger. So now, realizing that the Tatars were almost within earshot, he fled, stopping for only one night at Alexandrova Sloboda to collect his treasure chests full of jewels and gold and silver plate. The treasure represented wealth and power, an insurance against all emergencies; with it he could pay the expenses of his court, purchase military equipment from abroad, and perhaps—for his ultimate intentions are unknown—secure safe passage to England and live passably well on English soil.

He had no difficulty in justifying his flight. He complained later to the Polish ambassador that he had been led into a trap. “No one warned me about the Tatar army,” he said. “My own subjects led me straight to them. There were 40,000 Tatars, while I had only six thousand of my own troops.”

The Tatars, aided by Kudiyar Tishenkov, crossed the Oka River, quickly defeated a force of oprichniki, and continued to advance in great secrecy, carrying everything before them. Ivan was now completely cut off from the Russian armies on the Oka River. All he knew was that some dreadful calamity must have occurred. From Alexandrova Sloboda, with his two young sons, his treasure, his guards, and his household servants, he fled first to Rostov, then to Yaroslavl, and then to the Oprichnina stronghold at Vologda, surrounded by stone walls and permanently guarded by five hundred musketeers. There, planning to seek even greater safety, although he was already far in the north, he ordered the construction of river boats to carry him and his entourage to the White Sea by way of the Dvina River, and once he had reached the coast it would be a comparatively easy matter for him to arrange for one of the English ships to take him to England. Meanwhile he ordered the defenses of Vologda to be strengthened, apparently fearing that the Tatars would seek him out in this northern country or perhaps as Giles Fletcher suggested in his book because he feared that the Russian nobility and the officers of the army would hand him over to the Tatars.

Long before Ivan reached Vologda, the Tatars reached Moscow. Serpukhov, where they crossed the Oka River, was only a day’s ride or about sixty miles from Moscow. As soon as they heard about the crossing, the Russian army turned right about and raced for the city, which it reached only a few hours before the Tatars. Prince Ivan Mstislavsky threw his troops into the western suburbs inside the loop formed by the Moskva River. Prince Ivan Belsky’s army occupied the northern bank of the river from the Kremlin to the Yauza. Further east, across the Yauza, was the army of Prince Mikhail Vorotynsky, whose task was to guard the eastern approaches, while the Oprichnina quarter of Moscow was commanded by an army of oprichniki under the command of Prince Vasily Temkin-Rostovsky. He was one of those who took an active part in the July massacres and was seen to jump off his horse and cut off the heads of a man, his wife, and two sons, then he solemnly dragged the headless bodies and laid them before Ivan. Although the Princes were in a desperate situation, their armies far outnumbered by the Tatars; they had made a sensible distribution of their forces on the assumption that the battle for Moscow would be fought somewhere on the outskirts of the city. The fords nearest Moscow were well-guarded. The Kremlin itself, with the heavy cannon mounted on the walls, was virtually impregnable. Here and there, and especially in the Oprichnina quarter, wooden walls had been erected on the earthen ramparts, while the walls of the Kremlin and the Kitay Gorod with their towers and defense posts served as a powerful bulwark against the enemy.

The Tatars, driving up from the south, had not the least intention of fighting a pitched battle. Their intention was to destroy the city, acquire as much plunder as possible, and then return to their homeland. But in order to destroy the city it was necessary to come very close to it. Belsky’s army took up positions south of the river on the edge of the region known as the Great Field and offered battle. There was some savage fighting. Belsky was severely wounded, and the Russians were forced back. Meanwhile the Tatars pressed closer to the city not only in the south but also in the west, where a whole army crossed the ford near the Novodevichy Monastery to attack the Oprichnina quarter, which they stormed and set on fire. There had been little rain for some weeks, a strong west wind was blowing, and the flames spread to the Kremlin. Soon nearly all the palaces and churches within the Kremlin walls were burning. The small wooden churches exploded; the iron girders supporting the walls of the Granovitaya Palata melted away; the bell towers caught fire and the bells melted; and afterwards the Russians remembered that all the church bells of Moscow were ringing and one by one the sound of the bells died away.

On the morning of May 24, 1571, the heart of Moscow perished, and only a few charred buildings survived the fire by a miracle. The flames from the Oprichnina quarter spread eastward and threatened to engulf the whole city. For a few hours it seemed that the Kitay Gorod would be spared, but a gun foundry caught fire and the flaming roof sailed into the air and fell over the walls of the Kitay Gorod, which was soon in flames. Whole streets burst into flame. People who took refuge in the cellars were suffocated to death. Others, who ran to the river for safety, carrying their valuables with them, were killed by the Tatars or drowned. A few survived by standing in the river up to their necks. So great was the fury of the fire that about sixty thousand people, half the population of Moscow, perished.

Prince Ivan Belsky was among those who took refuge in a cellar. He died of suffocation. Heinrich Staden was luckier; he found a cellar already occupied, forced half of the people out at sword-point, brought in his own servants, and then locked the iron door until the fire had abated. He survived unharmed.

“The entire city was burned down in three hours,” says the Piskarevsky Chronicle. The chronicler relates that the first flames were seen three hours after sunrise and the fire had burned itself out by the early afternoon.

Devlet Guirey, the Khan of the Crimea, watched Moscow in flames from a safe vantage point on the Sparrow Hills. When it seemed that the fire might reach his encampment he sensibly took the precaution of moving away. He had seen what he had come to see. He had achieved two things which gave him immense satisfaction—he had humbled the Tsar and shown that the Russian army was no match for his Tatars. The armies of Mstislavsky, Belsky, and Temkin-Rostovsky had shown themselves to be incompetent; only Vorotynsky’s army, which had not yet engaged the Tatars, threatened him. But it was a small threat, he could take it in his stride, and at the most Vorotnysky would be able to mount skirmishes against the Tatar rear guard. The Khan moved on to the Tsar’s palaces at Kolomenskoye, which were pillaged and burned to the ground. Two days later, on May 26, 1571, the Khan ordered a general withdrawal. He plundered and took prisoners along the way, set fire to the wooden fortress of Kashira on the Oka River, devastated Kolomna and the entire province of Ryazan, and returned safely to the Crimea. Vorotynsky pursued him for a little way but soon gave up the fight. The Tatars had taken over 100,000 prisoners, who would bring good prices on the slave market.

Ivan’s flight to Vologda showed that he was deathly afraid of falling into Tatar hands. He had also come to some serious conclusions about the oprichniki, who had demonstrated their total incompetence and therefore deserved severe punishment. He said later that he only heard about the destruction of Moscow ten days after it happened, but since horsemen were known to have made the journey from Moscow to Vologda in four days of hard riding, he may not have been telling the truth. Moscow had perished, but not all was lost. He was still the Tsar and Grand Prince of Russia, and he could detect no feeling against himself among the long-suffering population. He decided to return to Alexandrova Sloboda and there, toward the end of the first week in June, he learned for the first time the full extent of the disaster. He immediately summoned the Metropolitan, the bishops, and members of the “ancient nobility” to a council. There is some significance in the fact that he called upon the long-established noble families for advice, since previously he had declared war on them and had founded the Oprichnina in the hope of destroying them.

The most urgent task was the rebuilding of Moscow, but first the dead bodies had to be cleared away, all the more since it was high summer and nothing had been done to remove them. Most of the survivors fled in fear of the pestilence. The rivers were choked with bodies, and there were more to come, for Ivan gave orders to throw all the dead bodies found in the ruins into the river. The cure proved worse than the disease. With more and more bodies thrown into it, the Moskva River was no longer a river; it changed its course; and the likelihood of pestilence only increased. The wells were dry, there was no fresh water, and the situation was desperate.

The Muscovites who had fled were ordered back; people from far-off towns and villages were ordered to go to Moscow to dig graves and help to rebuild the city. Masons, carpenters, and craftsmen of all kinds were pressed into service and promised freedom from all taxes and customs duties while the work was going on. It took four years to repair the damage. When the four years had passed, there was a new white wall of stone around the Kremlin and the Kitay Gorod, and where there had been thousands of gutted houses there was a new city.

Ivan refused to take any of the blame for the disaster. The fault, as he saw it, lay largely with the oprichniki who had not covered themselves with glory during the fighting and were unworthy of him. Although they had sworn absolute loyalty to him, they had completely failed him. In the past he refused to listen to any criticisms of them; if they attacked, imprisoned, raped, or murdered anyone, they had only to claim that the person was disloyal to the Tsar to be relieved of all responsibility. Simply by being oprichniki they were permitted the utmost license to commit as many crimes as they pleased. Now at last it was becoming evident that they had committed altogether too many crimes; and from being the Tsar’s chief defenders they became his chief liability.

Another bloodbath began: this time the oprichniki were the victims. Ivan appears to have begun this bloodbath cautiously and circumspectly, for there were now few public executions. Peter Zaitsev, one of the original oprichniki, was “hanged from the court gates opposite his bedroom.” Prince Vasily Temkin-Rostovsky, who had shown himself to be so pathetically incompetent when the Tatars attacked the Oprichnina Palace in Moscow, was summarily executed. Another commander of the palace forces was Prince Mikhail Cherkassky, the brother of the Tsar’s second wife, Maria Temriukovna, who had died two years earlier, but his close relationship to the Tsar did not save him from execution. Some high oprichnik officers were simply clubbed to death, and over a hundred died of the poisons administered by Ivan’s doctor, Eliseus Bomelius.

Bomelius, too, met the fate he deserved. He came originally from the town of Bomel in the Netherlands. At various times he was a Lutheran preacher in Westphalia, a doctor of medicine with a degree from Cambridge University, a practicing astrologer in London, and a convicted felon in the King’s Bench prison. He was by all accounts a quack, a mischief-maker, a man learned in many arts and unscrupulous in all of them. He came to Russia in the train of the Russian ambassador to England and immediately set about working on Ivan’s weaknesses. He claimed to foretell the future, to be able to cure all diseases and to possess magical powers. The Tsar was impressed and rewarded him handsomely. He was able to send his wealth to the town of Wesel in Westphalia, where he intended to retire. He was a superb poisoner. Taube and Kruse report that when Ivan returned to Alexandrova Sloboda he began to rid himself of many highly placed oprichniki. “The Tsar,” they reported, “gave written instructions to the doctor on the length of time the poison should take effect. Sometimes he wanted it to take effect in half an hour, at other times he wanted it to take effect in one, two, three, or four hours.” The doctor performed these tasks to Ivan’s complete satisfaction. Four years later he decided to leave Russia secretly, lined his pockets with gold, and reached Pskov, where he was recognized and placed under arrest. Brought back to Moscow, he was accused of intriguing with the Kings of Poland and Sweden, tortured on the rack until his limbs were out of joint, whipped with iron wires, and finally bound to a spit and roasted. When he was taken down, there was still some life in him. Jerome Horsey, visiting the Kremlin at the time, suddenly saw the roasted wreck of a man being driven away in a sleigh. “I pressed among many others to see him; cast up his eyes naming Christ; cast into a dungeon and died there.” Thus, graphically, Horsey described the end of a man whom the Pskov chronicler described many years later as a ferocious magician who “completely turned the Tsar away from the faith, made him hate the Russian people, and caused him to love foreigners.”

That Bomelius exercised considerable powers over Ivan’s mind is not in doubt, but it may be questioned whether he succeeded in completely turning the Tsar away from the faith. Eliseus Bomelius had many uses as a doctor and prognosticator. As doctor and poisoner he seems to have been as good as any in his time; as prognosticator he failed as often as he succeeded. According to Jerome Horsey he prophesied that Queen Elizabeth would eventually marry Ivan and thus encouraged him to persist in his suit. Horsey, who knew him well, said “he lived in great favor and pomp, a skillful mathematician, a wicked man, and practicer of much mischief.”

There were other practicers of mischief: among them was Devlet Guirey, Khan of the Crimea, who sent his ambassador to Ivan on June 15, 1571. Ivan was in no mood to receive the ambassador and his entourage, but had no alternative. At all costs he was determined to delay as long as possible another encounter with the armies of the Khan, who now demanded the cities of Astrakhan and Kazan as the price of peace. To forestall the surrender of these two large jewels in his crown, Ivan was prepared to pay a high price. A new army was being sent to the Oka River, careful plans were being made by the military, and to avoid a war on two fronts Ivan was preparing to sign a treaty of friendship with the Swedes, who occupied part of Livonia. The ambassador, who was a prince of the Crimean Khanate, arrived with an escort of nobles and guards armed with bows and arrows and “curious rich scimitars.” They rode up to Ivan’s palace at Bratashino on the road between the Troitsa-Sergeyevsky Monastery and Moscow. At first Ivan treated them roughly, feeding them on stinking horseflesh and water, depriving them of proper sleeping quarters. He was obviously attempting to provoke them, but “they endured, puffed and scorned” this base usage, for they were very sure of themselves and knew that Ivan would eventually grant them an audience. They had nothing to lose; the Tsar had much to gain.

The Tatars wore long black sheepskin kaftans and carried themselves with grave dignity. The ambassador was a man of consummate ugliness with a harsh, penetrating voice. He was taken into the throne room alone, guarded by four Russian soldiers, and the Tatar nobles who had accompanied him were allowed to look on through an iron grille. Ivan sat on a throne, wearing cloth of gold, with three of his crowns beside him. Probably they were the crowns of Muscovy, Astrakhan, and Kazan, which was especially beautiful with its curving petal-shaped leaves of gold. The ambassador wore a gown of cloth of gold and a rich cap given to him by the Tsar. He had much to say in his penetrating voice, and Ivan would have preferred not to listen to it.

The ambassador declared that he was the envoy of the Khan of the Crimea, “who rules over all the kings and kingdoms the sun shines upon.” It was the Khan’s pleasure to inquire about Ivan’s feelings now that he had felt “the scourge of the Khan’s displeasure by sword, fire and famine.” It was a taunting speech, deliberately conceived to infuriate Ivan. The princely ambassador produced a rusty gold-handled knife, which had belonged to the Khan, and he suggested that there was a sovereign remedy for all the ills that had befallen Russia. He gave Ivan the knife, hinting that he might like to cut his own throat with it.

“My Lord wanted to send you a horse,” the ambassador went on, when Ivan declined the knife. “But all our horses have become exhausted after riding so far across Russia.”

Ivan succeeded in keeping his self-control. He commanded the ambassador to read the letter from the Khan of the Crimea. The ambassador began reading:

“I came to Russia, devastated the land and put it to the flames to avenge Kazan and Astrakhan. I desire neither money nor treasure, for they are of no use to me. As for the Tsar, I searched for him everywhere. I searched for him in Serpukhov and in Moscow, desiring his head and his crown. But you did not come to meet us, you fled from Serpukhov, you fled from Moscow, and still you dare to call yourself Tsar of Muscovy. You have no shame and are completely without courage. If you desire our friendship, then giveus back Kazan and Astrakhan, and swear an oath on behalf of yourself, your children and your grandchildren that you will do as I command. And if you do not do these things, beware! I have seen the roads and highways of your kingdom and I know the way!”

The Tsar remained silent, in a mortal rage. The guards hustled the ambassador out of the throne room, attempting to remove the gold gown and rich cap which he wore so insolently, but he was able to take care of himself until his retinue came to the rescue. We are told that Ivan went into a state of shock. “He fell into an agpny, sent for his ghostly father, tore his own hair and beard.” The captain of the bodyguard offered to cut the ambassador and his entire retinue to pieces, but Ivan made no answer and the captain wisely concluded that it would be altogether too dangerous to kill the Tatars on his own responsibility.

Thereafter the Tatars were treated more tenderly. They were given good food and the best accommodation available, while the Tsar labored over the message to be sent back to the Khan of the Crimea. Finally the Tsar summoned the ambassador and gave him a message which Jerome Horsey has recorded in vigorous Elizabethan English:

Tell the miscreant and unbeliever, thy master, it is not he; it is for my sins and the sins of my people against my God and Christ; he it is that has given him, a limb of Satan, the power and opportunity to be the instrument of my rebuke, by whose pleasure and grace I doubt not of revenge and to make him my vassal or long be.

Ivan was saying, as he had said so often, that God would grant him the ultimate victory before long, but meanwhile he was being made to suffer for his sins and the sins of the Russian people. Soon the Crimean Khan would become his vassal; the tables would be turned; the vanquished would become the victors. The ambassador in his thundering voice replied that he absolutely refused to give such a message to the Khan. There were no further incidents. He left the throne room and returned to the south.

Ivan’s message, as recorded by Horsey, conveys exactly the tone of furious piety favored by him. It was inconceivable to him that the Khan was really responsible for so many disasters to Russia. Suffering arose from sin and from the wrath of God; the Khan was merely “the instrument of my rebuke.” By prayer and pilgrimage he hoped to direct God’s wrath upon the enemy.

Meanwhile Ivan employed all his diplomatic skills against the Khan. Afanasy Nagoy, one of his best ambassadors, was sent to the Crimean court with instructions to speak softly and to prolong the negotiations as long as possible. The Khan would be offered Astrakhan, but only provisionally; if he sent his son to be Khan of Astrakhan, there must also be a Russian governor and the Russians in Astrakhan must be given full liberty to practice their trades and their religion as before. Ivan manufactured conditions and exulted in making them unacceptable. Afanasy Nagoy was instructed to ask whether the Khan of the Crimea would permit Ivan to place the crown of Astrakhan on his son’s head, thus making him a vassal. By concentrating on Astrakhan Ivan hoped that the subject of Kazan would not be raised.

By October 1571 the Crimean Khan had grown impatient. He wrote: “You offer Astrakhan, but Astrakhan is only part of what we want. We want Kazan as well. Otherwise you will have the upper part of the river and we shall have only the lower part. This is intolerable.”

Since it was clear that the Khan would not yield, Ivan continued to temporize. Letters from the Khan remained unanswered; the ambassadors were kept in seclusion and told that Ivan was engaged in pressing business. In fact he was very busy. On December 24, 1571, he reached Novgorod with an army which he intended to throw against the Swedes. Happily there was no fighting and he was able to secure a truce with Sweden. He was back in Alexandrova Sloboda toward the end of January 1572. When a Tatar ambassador arrived on February 5, Ivan said he had just vanquished the Swedish army in battle. As for the question of Kazan, this was not a matter which could be discussed lightly. High plenipotentiaries would have to meet, a peace treaty would have to be concluded, an offensive alliance against Poland and Lithuania would have to be signed. “The sword remains sharp only for a little while,” Ivan reminded the ambassador. “Too much use blunts it, and it is possible that the blade might break.” The Khan demanded immense gifts, and the Tsar replied: “Our land is barren and we have nothing to give.” All the time reinforcements were being hurried toward the Oka River.

On October 28, 1571, the Tsar married for the third time. The bride, selected from among two thousand beautiful girls from all parts of the country, was Marfa Sobakina from an ancient noble family of Tver. A week later the Tsarevich was also married. His bride was Evdokia Saburova of a well-known boyar family in Moscow.

When Ivan married Marfa Sobakina, she was ailing. He knew she was ill but believed that with God’s help he could cure her sickness. Instead her illness grew worse and she died on November 13, 1571, sixteen days after her marriage, to the consternation of Ivan who believed that this was another sign of God’s wrath. He would say that Anastasia died because evil persons cast a spell on her and poisoned her; that his second wife was also poisoned; that the third died as a result of evil spells. He thought of becoming a monk and putting the world behind him, but decided against it, saying that “Christians are being enslaved, Christendom is being destroyed, and my children are not yet grown up.” In March 1572 he convoked a Church Council to advise on whether it was permissible to marry for a fourth time, having chosen Anna Koltovskaya, who belonged to the minor court nobility, as a prospective bride. The bishops deliberated and agreed to permit the marriage on condition that he did penance for a year. The Tsar always enjoyed doing penance and faithfully obeyed the bishops, who ruled that during the course of a year he would not be permitted inside the church to receive the Holy Sacraments but must remain outside.

The marriage to Anna Koltovskaya brought him no children. Four years later he abruptly divorced her and ordered her to spend the rest of her days in a nunnery in Tikhvin in the far north.

The Tatar invasions usually took place in the spring or early summer. The negotiations with the Crimean Khan had broken down and it was now evident that the Khan would attempt another massive invasion, and this time the consequences might be even more disastrous. In fact, the Khan was determined to reduce Russia to the status of a Tatar province. He intended to capture Ivan alive and bring him in triumph to the Crimea. Already the Tatar princes were being assigned principalities and the Sultan of Turkey had been promised “a huge gift of treasure” from Ivan’s treasury for his help in providing heavy guns. This time the Khan intended to “advance like a bloodthirsty lion, his ferocious jaws wide open to devour the Christians.”

The Zemshchina forces on the Oka River had been working frantically for many months to improve the defense works. For a length of about 250 miles earthworks were being erected along the river banks, cannon were mounted wherever the Tatars might be expected to cross, the fortresses south of the river were strengthened, and trees were being cut down to delay the advance of the Tatar cavalry. The Russians had made careful plans to signal the approach of the Tatars long before they reached the Oka River and they were making plans to set fire to the steppes. Thanks to an improved system of reconnaissance the Russian commanders on the river bank believed they would be able to foretell exactly where the Khan would attempt to cross the river and crush him.

Although a Tatar invasion was expected for the early summer, Ivan refused to take command of the army in the south, but instead took the precaution of retreating to Novgorod with all the treasure he could lay his hands on. It was estimated that 10,000 puds, corresponding to 180 tons, of treasure were sent to Novgorod, where he arrived on June 1, 1572, to be greeted by Archbishop Leonid with the customary fanfare. The Tsar lived quietly in his palace. He attended services in the Cathedral of St. Sophia which he had despoiled two years earlier and prayed for deliverance from the Tatars. On July 2 a great storm arose and the crosses on many churches, including the church attached to Ivan’s palace, were blown down. This was a bad omen.

Ivan was devoured with anxiety. He knew the Tatars were determined to capture him alive and take his treasure, and he congratulated himself that he was now out of their reach and his treasure was safe, but his future as Tsar depended upon a Russian victory. It was doubtful whether he could continue on the throne if there was another disaster like the last. The generals on the Oka River sent him regular reports, but he half-distrusted them and preferred to have his own independent sources of information. Thus we find him writing to Evstafy Pushkin, the governor of Staritsa, on July 17:

Tell me when the Khan is going to reach the river, and where he will cross, and in what direction he will be coming. You must let me know this without fail. You are not permitted to keep us waiting without news. Information should be sent to us by a courier with two horses. You should also see that one or two people at Tver should be ready to bring us news of the coming of the Khan. At all costs keep us informed.

From Novgorod he sent his closest aide Prince Osip Shcherbatov to the Oka River, encouraging the army to hold fast and promising abundant rewards to the generals if they succeeded in destroying the Tatars. In this way, offering bribes and sunk in misery, he waited for the coming of the Tatars.

How deeply miserable he was we know from the will he wrote while in Novgorod. He was forty-two years old, but wrote like a man in extreme old age. Much of the will is concerned with advising his sons Ivan and Fyodor about their future behavior. They should love one another and the younger should loyally serve the older, the future Tsar. Remembering Christ’s injunction, “This I command, that you love one another,” he urged them to love all those who returned their love and to punish implacably all traitors. They must not punish in fury, as he had done. On the contrary they should sift the evidence cautiously and without rancor. They must learn statecraft, study the people, advise themselves about foreign affairs, and be well-informed about matters of Church and state, for others will snatch the power from them unless they are knowledgeable. They must especially study military affairs. “You should learn all those things that need to be learned, whether they pertain to the monasteries, the army, justice and the government of Moscow, and the daily life of the people. Then they will not tell you what to do, but instead you will tell them what must be done, and thus you will acquire mastery over your realm and your people.” He seemed to be thinking of the days when his actions were guided by the Chosen Council and especially by Sylvester and Adashev, before he had taken full power in his own hands.

He also warned his sons against making the wrong friends. “You should love and favor those people who serve you loyally,” he wrote. “Protect them from everyone so that no harm shall befall them, and they will serve you with greater loyalty.” Nor should they strike in anger. Punishments, he explained, should be administered only after all the facts had been ascertained, not in a moment of rage. It was very late in the day for such discoveries.

The testament of Ivan is remarkable for the mood of somber self-questioning. He was evidently fearful about the future and the fate reserved for his physical body and for his immortal soul. He was deeply aware that he had committed crimes so vile that they cried out for punishment. Self-pity, self-abasement, fear of the wrath of God all had their place in his confession. He wrote:

My body has grown feeble, my spirit is sick, and the ills of my body and spirit have increased, but no doctor can cure me. I looked for someone to grieve with me, but found no one. I received evil for good, and my love was answered with hatred. For my many sins God’s wrath descended upon me, and the boyars in their wilfulness deprived me of my inheritance, and now I roam from place to place as God wills.

He went on to accuse himself of lascivious speech, unjustifiable rages, drunkenness, debauchery, thievery, murder, even fratricide, for had he not committed the “sin of Cain” when he killed Vladimir of Staritsa? He had committed so many crimes that “although I am a living person, yet in the eyes of God my evil deeds have made me more putrid and more hideous than a corpse, and because of this I am hated by everyone.”

There remained the grant of the succession which went to his elder son Ivan, while the younger son Fyodor was to receive a huge principality which included whole provinces and the cities of Yaroslavl, Volokolamsk, Suzdal, and Kostroma.

Ivan wrote his testament in abject fear—fear of the Tatars, fear of betrayal by those around him, fear of the army which might hand him over to the enemy, and always the fear of God. He was writing in a city where he had murdered countless numbers of Russians. Hourly he expected news of defeat. Instead there came news of a resounding victory. On August 6 two noblemen sent by Prince Vorotynsky rode into Novgorod with the news that the Crimean army had been defeated at a small village halfway between Serpukhov and Moscow. As trophies they brought two Tatar swords and two bows and quivers captured from the enemy. The Tsar ordered that all the church bells should ring and that a solemn service should be held in the Cathedral of St. Sophia. The stern and saintly Archbishop Leonid presided over the service.

The Tsar rewarded the two noblemen and sent one of his closest advisers, Afanasy Nagoy, to the Russian Army with gifts and gold medals.

He learned that towards evening on July 26 a huge Tatar army had appeared on the south bank of the Oka River. Throughout the next day, a Sunday, they were held off by heavy cannon fire, but in the darkness of Sunday night the main Tatar army succeeded in crossing the river at Kashira. The Crimean Khan then led his troops toward Moscow, the Russians in hot pursuit. The Khan’s progress was slowed up by his heavy cannon; the Russian vanguard caught up with the Tatar rear guard near the village of Molodi; and soon the main Russian army joined it and hastily threw up earthworks and palisades. Divey Mirza, the commander in chief of the Tatar army, hesitated between advancing on Moscow, now only fifteen miles from his advance forces, or turning back.

Finally Divey Mirza decided to give battle in Molodi. There were skirmishes, three thousand Russian musketeers in an advance position were wiped out by Nogay cavalrymen, but Divey Mirza was captured when his white horse stumbled and threw him. According to the Anonymous Chronicle he was not immediately recognized, but when the captured Tatar prince Shirinbak was being interrogated and asked about the plans of his commander in chief, he replied, “All our plans are with you, because you have captured Divey Mirza, who knows everything.” The Russians then set about finding Divey Mirza among their captives. At last he was found and taken to Vorotynsky’s tent, and when Prince Shirinbak threw himself down at Divey Mirza’s feet, the Russians knew that the battle was half over.

Skirmishes continued through the week, but on Saturday, August 2, the Crimean Khan threw his army against the Russian palisades in an effort to rescue Divey Mirza. The Tatars, who fought best on horseback, were ordered to dismount before they reached the palisades. When they attempted to climb the wooden walls, their hands were chopped off. Meanwhile Prince Vorotynsky had succeeded in taking most of the main army out of his hastily erected fortress and moving it through a hidden valley to the rear of the Tatar forces. Then he pounced and simultaneously the heavy cannon inside the fortress opened fire on the Tatars, who broke and fled. Many, caught between two fires, were slaughtered. The Crimean Khan fled with his guards, in the words of the popular song, “not by the roads and not by the highways.” The Novgorod Chronicle relates that a hundred thousand Tatars were left dead on the battlefield. Heinrich Staden, who claims to have been in the thick of the fighting, wrote that “every corpse that had a cross round its neck was buried at the monastery that lies near Serpukhov, while all the rest were left to be eaten by the birds.” Soon people all over Russia were singing a song about the triumph of the Russian army over the Tatars:

No mighty cloud covered the heavens,

No mighty thunder roared from the sky.

Where is he going, the dog, the Crimean Tsar?

He is going to the mighty Tsardom of Muscovy.

“Today we shall conquer stone-built Moscow:

On the way back we shall take Ryazan.”

And when they reached the Oka River

They pitched their white tents.

“Now ask yourselves the keenest questions:

Who shall sit in stone-built Moscow?

Who shall sit in the city of Vladimir?

Who shall sit in the city of Suzdal?

Who shall keep old Ryazan?

Who shall sit in the city of Zvenigorod?

Who shall sit in the city of Novgorod?”

Then Divey Mirza, son of Ulan, stepped forward:

“Listen, our Lord Khan of the Crimea,

You, our Lord, shall sit in stone-built Moscow,

And your son shall sit in Vladimir,

Your nephew shall sit in Suzdal,

Your cousin shall sit in Zvenigorod,

Your Master of the Horse shall sit in old Ryazan,

But to me, O Lord, grant Novgorod:

There in Novgorod lies my good fortune!”

The voice of the Lord cried out from heaven:

“Listen, you dog, Crimean Khan!

Know you not the Tsardom of Muscovy?

There are in Moscow seventy Apostles

Beside the three Holy Fathers,

And there is still in Moscow an Orthodox Tsar.”

And you fled, you dog, you Crimean Khan,

Not by the roads and not by the highways,

And without your banners, the black flags!

Rarely in the past had the Russians enjoyed so complete a victory over their enemies. So heavily punished were the Crimean Tatars that they mounted no further full-scale attacks for the rest of Ivan’s reign. At the battle of Molodi the Russian army recovered its full strength and prestige. The news of the victory traveled all over Europe; the chronicles acclaimed it; and Ivan realized at last that the army was more important than the Oprichnina, which was now doomed.