CHAPTER 14

*

McCabe & Mrs. Miller (1971)

Andrew Sarris, review in The Village Voice, July 8, 1971: McCabe & Mrs. Miller confirms the impression of striking originality that goes beyond the Beetle Bailey mechanics of M*A*S*H to the more controlled horror and absurdism of That Cold Day in the Park and Brewster McCloud. … McCabe succeeds almost in spite of itself, with a rousing finale that is less symbolic summation than poetic evocation of the fierce aloneness in American life. I can’t remember when I have been so moved by something that has left me so uneasy to the marrow of my aesthetic. Unlike so many of his contemporaries, Altman tends to lose battles and win wars. Indeed, of how many other films can you say that the whole is better than its parts? [Warren] Beatty’s reluctant hero and [Julie] Christie’s matter-of-fact five-dollar whore are nudged from bumptious farce through black comedy all the way to solitary tragedy imbedded in the communal indifference with which Altman identifies America. However, Altman neither celebrates nor scolds this communal indifference but instead accepts it as one of the conditions of existence.

* * *

DAVID FOSTER (producer): I had been in Paris meeting with an agent named Ellen Wright, who was the widow of the famous African-American author Richard Wright. She represented a guy, an American novelist named Edmund Naughton, who wrote a novel called McCabe. She said, “You ought to take this book and read this.” She started throwing names around to direct—John Huston, Roman Polanski. It was a great book. I read it on the plane home, over the pole, from Paris to L.A. I got off the plane and called my neighbor and attorney and best friend, Frank Wells. I said, “I’ve got to get it.”

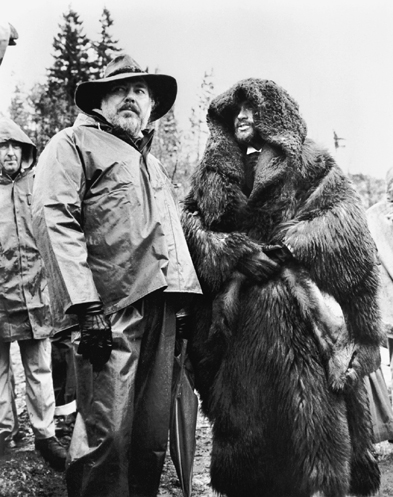

Listening to bearskin- wrapped Warren Beatty while making McCabe & Mrs. Miller

We bought the book. Now what do I do with it? John Huston—he was off doing some picture. And Polanski I really didn’t know. Fabulously talented guy. Through connections I got word to him that I optioned this book called McCabe. I never heard back. I had a friend named George Litto. Crazy son of a bitch. A madman but I loved him. He said, “I have a client who wants to do a Western but not a traditional Western.” M*A*S*H was in the can but no one had seen it yet. He said, “His name is Robert Altman.” I said, “Who’s Robert Altman?” Nobody knew who he was.

I got a call from George saying Bob was going to show M*A*S*H to the composer Johnny Mandel. He could sneak me in if I sat quietly. Which I did, and I fell in love with it. Afterwards I met Bob. Litto looked at us and said, “Are you guys committing to each other to do this movie?” I said, “I am.” Bob said, “I am.” George says, “Okay, you’ve got to sit still for the next three or four months. If this movie is as good as you think it is, everybody will want Bob Altman.” That’s what happened. Everybody wanted Bob Altman at that point because M*A*S*H put him on the map. And I had him.

M*A*S*H was going to be screened in New York for Darryl Zanuck. Fox wouldn’t pay for Bob to go. I’m not a studio. I’m scratching for money. I scraped up enough money for both of us to go to New York, and Darryl Zanuck didn’t know what they had. He thought it could be interpreted as anti-American. Honest to God. We get to the hotel—I was paying for all this—and Fox wouldn’t pay for shit. The phone rings and it’s one of the executives at Fox in New York. “Bobby! Bobby!”—nobody called him Bobby—“we got a great advance in The New York Times!” Now suddenly he’s Bobby. It was a fucking joke, and on the Sunday that it opened, we went back to L.A.

People who had passed on it earlier suddenly wanted McCabe because it was Bob Altman. He was the flavor of the week. There was an agent at William Morris, a guy named Stan Kamen. He was a phenomenon. He had Steve McQueen, Warren Beatty, all these guys. Warren was in London when Stan called him, “Got this script, it’s called McCabe & Mrs. Miller. It’s going to be directed by Bob Altman. This is going to be the new giant director. You’ve got to see this picture, M*A*S*H.” Warren flew from London to New York, got off the plane, went to a theater on Third Avenue. Got back on the plane and flew to L.A., met with us, and committed to do it. He committed for himself and for Julie Christie, who he was living with.

* * *

JOAN TEWKESBURY: I went to his office and I simply asked for a job. I had directed Michael Murphy in a one-act play that Bob came to see. He barely remembered who I was. He said that he was going to Canada to shoot McCabe & Mrs. Miller. He said, “You can’t just come and observe.” He said that’s like being a groupie. But he said the script girl he was planning to use was now one of the hookers in McCabe. Bob wanted this chorus of accents. Nobody spoke English English. The reason he wanted the script girl to be one of the hookers was because she was from Australia and she had the accent. Basically he was developing this town full of people who were all from someplace else. It was all part of his idea about how to make a Western that wasn’t a Western.

ROBERT ALTMAN: They were all first-generation Europeans. There wasn’t anybody who spoke Texas: “Howdy, pardner.” That didn’t exist.

JOAN TEWKESBURY: So, if I wanted to, I could be the script girl. By the time I got there, he had forgotten who I was, as only Bob can do.

Bob’s idea about the script was that the church was the focus of the town—the town’s name was Presbyterian Church. The film was originally going to be called The Presbyterian Church Wager. At the end of the movie, he knew he was going to burn the church and what people would discover was that there was nothing in the church. It wasn’t a sacred place. There was just this guy, the preacher character, who was half crazy, living inside this shell.

COREY FISCHER: He gave me the role of the preacher, the Reverend Elliot. The preacher was clearly nuts, a fanatic, an obsessive. He was like McCabe’s shadow, something from McCabe’s unconscious rearing up.

I think Bob was disappointed with me because the biggest moment for that character was when he hauled that cross up to the church, that tremendous shot. That wasn’t me. That was a stuntman. I have a terrible fear of heights. No way was I going up there. Bob had a macho side. He tried to shame me into getting up there, but no way. Nobody knew the difference, certainly not the audience, but he knew. I know he was disappointed. I always joked that after that I was replaced by Jeff Gold-blum as the tall young Jew. I never really saw Bob again.

KEITH CARRADINE (actor and songwriter): I was told there was a role for a young cowboy. He was supposed to play the banjo and Robert Altman was going to be directing it. Did I play the banjo? As all young actors will say, I said, “Absolutely.” Well, I didn’t play the banjo. I played the guitar and piano and harmonica, but I’d never picked up a banjo. Immediately I went out and bought this really cheap Kent banjo and a banjo book, and I started learning to play. I was told I was going to have a meeting with Robert Altman and I was told to go to his offices, which were the Lion’s Gate offices in Westwood. And they occupied this little office suite off of Westwood Boulevard, south of Wilshire Boulevard.

I went over there and I went to the main reception and they told me, “Oh yes, Mr. Altman is upstairs.” So I went up the stairs and I knocked on the door, and at this point I had done one part. I had done my first movie, which was a gunfight with Kirk Douglas and Johnny Cash, but I was still sporting my long hair because I had just come off of a year in Hair on Broadway. So my hair was probably about eighteen inches long at that point. I was a hippie. And I walked into Bob’s office. It was actually an apartment that he had where he would stay if he decided not to drive home at night. I opened the door and he was standing at the foot of his bed and he was unwrapping this brown-wrapped package, and he was wearing a bathrobe and a T-shirt.

He said, “Hi, you’re Keith.”

And I said, “Yeah.”

He said, “I’m just unwrapping this—I just came back from the Cartagena Film Festival in Colombia.”

And I’m thinking, “He’s unwrapping a bale of dope.” But in fact it wasn’t dope. He was unwrapping some pre-Columbian art that he had bought down there and had shipped back. He sort of looked at me as he was looking at his stuff.

He said, “So, we’re going to do this movie.”

And I said, “Yeah.”

He said, “We’re going to shoot it up in Vancouver and it’s a Western and there’s a part for this kid who comes into town. Basically he comes into town because he’s heard there’s a whorehouse.”

And I said, “Yeah, yeah. I heard about it.”

He said, “So, do you want to do it?”

I looked at him like, “You’re asking me if I want to do the part?” I didn’t say that. I said, “Sure.”

And he said, “Okay. I don’t know about the hair. Maybe we’ll keep the hair. I think the hair is good.”

Which was a great relief to me, because at that point I was nineteen, twenty years old and my long hair was my identity. It was my badge.

That was the beginning of my working relationship, friendship, love affair with Robert Altman. That was how he worked. He cast essence. He wanted pure behavior and he wanted the essence of people and that was his genius. You didn’t have to audition for him to know if you were the right person for the part. He didn’t really cast actors so much as he cast people. He loved actors and he stood in awe of actors. He didn’t understand how they could do what they did and he found it a baffling mystery and a wondrous thing and he just loved to create an environment where he could take people who did that and give them the freedom to do that in their own inimitable way.

Thank goodness that’s the way he worked because that really was the beginning of my validation in Hollywood terms. He validated me because I was chosen by Robert Altman. That gave me a credibility in the community that I could not have gotten any other way, a particular kind of credibility.

When I first got there, they had a big trailer set up, a makeup trailer, and Bob came over to me and he said, “Come on, let’s go in here.” He put me in the makeup trailer, he sat me down and he said, “Cut his hair off.” He saw my look in the mirror, you know? And he said, “Kid, if that’s where your ego is, it’s in the wrong place.” I’ve never forgotten that.

* * *

RENÉ AUBERJONOIS: I learned a big lesson there about Bob and why you should never read a script of a film that Bob is about to direct. It’s a waste of time and it’s counterproductive to you as an actor. In the script, my character, the bar owner, Sheehan, was supposed to come upon Warren Beatty’s McCabe and find him wounded and finish him off. I remember Bob taking me aside and saying, “We’re not going to do that.” That was deep into the film. I was deeply disappointed because I thought that completed the arc of the character. I was heartbroken, but that was stupid. I think it’s his best film.

JOAN TEWKESBURY: Ideas were discussed with Julie or with Warren and they would go off on drives or would come over for dinner. Everybody would come over for dinner. And members of the chorus—who were really members of the repertory company—they would be included. Half of Bob’s work was always done over dinners or, in quotes, parties or those kinds of preparatory things, where everybody would get to meet one another or talk to each other. As those relationships would form they would inform the story they would tell. Julie had one of her friends there, and she and Julie were rewriting dialogue for Julie. There would be Saturdays where I would go to the house and Bob would dictate scenes, and that would be the work we were gonna do the next day or the following Monday. Then Warren would bring in his stuff and then there would be times when Bob and Warren would come together and do stuff.

MICHAEL MURPHY: When you weren’t in his movies it was upsetting because you knew there were a lot of people out there having a hell of a good time and you weren’t. That was the big draw. In the usual manner, I get a call from Bob one day.

“Murphy, you want to be in this film, this movie?”

And I said, “Yeah.”

He says, “Okay, I need my car up here. I’ll give you six hundred fifty a week.”

So I drove his car up to Vancouver from L.A. It was a nice trip, too, up that coast. I went up to work on McCabe & Mrs. Miller for a few days and I stayed for months just hanging around. He cast me as this young guy who comes into town with the older man, a partner in the business, to offer McCabe money. We want to buy him out. We represent the industrialists, the movers and shakers. We offer him, I don’t know, fifteen hundred dollars or something and he passes. He’s bluffing. He wants more money, and so then we send in the killers, to wipe him out. We were just talking one night and I said to Bob, “What do you think about this guy?”

He said, “He’s somebody’s nephew” [laughs]. That was all the direction he gave me. It was perfect. I knew exactly what he was talking about. You know, send the kid on this job, see how he does dealing with this rube out in the middle of nowhere.

JULIE CHRISTIE (actress): He gives you a little clue—like when I had to say a whole lot of stuff about numbers and money. I couldn’t remember it because I’m innumerate. He made me look for something I’d lost on the ground. He solves his problems with actors quite practically, very often with physical stuff.

ROBERT ALTMAN: I sent to Warner Brothers for wardrobe. I told them to send up a truckload of clothes and things for a Western for that period. I told the actors, “Okay, everybody, go to the wardrobe truck and pick out your clothes. You can have one pair of pants, you can have two coats of different weight—one that you can put over the other. You can have one shirt, a pair of boots, a pair of pants.” Of course the smart ones picked out the most distressed stuff, the clothes that had the most character. And then I said, “Now, you’ve got to live in these clothes in this fucking weather, so you’d better get out there and sew those holes up.” So they all went out and repaired their own clothing. And they picked out little artifacts that made their characters more real. I said, “These are yours. And you can’t have anything else in the picture, and you can’t get rid of these. You have to take care of this stuff.” So the cast and the wardrobe were terrific because there was a reality to it.

Speaking with Julie Christie, as Mrs. Miller

The set designer, Leon Ericksen, was a genius. He was a big, big influence on me in terms of how to approach that kind of reality. Just to walk on the set and have there be trash in the trash can. He’d have stuff in the drawers, whether or not those drawers were going to be opened. There was a museum quality to it. He was the purest of all the people that I worked with, other than occasionally actors. He taught me how to deal with artifice, with sets. I was doing these films inside this reality that Leon created. In McCabe, we shot the film in sequence as the town was built. All of the carpenters, all the workmen, lived there. They actually lived in the place and they were all hippies. They were all Leon’s friends.

JOHN SCHUCK: You walked through these two wooden gate doors and you were back in the 1800s. There was no question about it. We got behind schedule in building the town—it grew as the movie went along—because the guys were throwing away their power tools and wanted to do everything by hand.

KEITH CARRADINE: The sets for that movie in West Vancouver were up above a housing development. It was right around the corner from where the newly built houses stopped and the road sort of turned to the left and there was a little gatehouse and there was all this parking out there. You left your car, you walked through this gate, and about twenty or thirty feet after you walked through the gate, you went around the bend and it was 1901. It was absolutely magical.

He had all these carpenters and craftspeople and artisans from Vancouver that came up to work on the set and build the place, and they were invited to stay. All you had to do was put on period clothing and you could hang out here and keep working on the building you’re building and that’s how he had this incredible atmosphere of a town sort of rising out of the mud. It was a living place. People would spend the night there. They would sleep in their tents or their tepees.

MICHAEL MURPHY: So then the actors come to town and they wanted to live in it, too. René wants to live in a saloon. The crew guys are like, “Goddamn actors.” They had to go find another place to live. The actors would live in the place two nights and decide they don’t want to do that anymore, they want to go back to the Hilton [laughs]. Then you’d go to work. You’d shoot and the next day you’d go to work and the whole town would be framed. Every time you’d come to work the set looked different—fifty new townspeople had moved in. I don’t think there are a whole hell of a lot of guys that could shoot a picture that quickly and keep that working as well as Bob did. When you have those big changes on a location, it really freaks people out. The reason he could move the way he did was he always had the picture cut in his head.

* * *

VILMOS ZSIGMOND (cinematographer): That was the luck of my life, actually, to do McCabe & Mrs. Miller. I was shooting in Santa Fe, and he calls me up and says he had this movie, it’s an old Western. He described it in images, very old, like antique photographs and faded-out pictures, not much color.

ROBERT ALTMAN: I had seen something. I think it’s in my dreams. Or I’d seen a Western in which the way the buildings were built or the way the people walked looked real. And I don’t know when I saw it, or where I saw it, or even if I saw it. But I had that look in my mind.

VILMOS ZSIGMOND: I said, “Bob, I have the right thing to do. I just read an article about it and I will make tests about flashing the film.” He said, “How is that done?” I described flashing the film and what does that do to the film. It makes it sort of grayish, very grainy, especially if you underexpose it and push the film, and you are going to get this old look that way. He said, “Yeah, that’s fine, that’s great. We are going to do that.”

He made the test before I even got to Vancouver. I described what to do, and then he actually hired the standby, and told him how to flash five percent, ten percent, fifteen percent on the test. That’s how we decided fifteen percent of flashing would be just perfect for the movie. But he loved this whole process.

The studio hated it. It was Warner Brothers. Some executives said, “This guy doesn’t know how to expose film! Everything is underexposed, it’s grainy, we have to reshoot everything!” And Bob said, “No, no, no, understand something. We have a new lab here in Vancouver. They don’t know what they are doing. The film is going to get to Hollywood, it’s going to be great. You’ll love it.” So they left us alone. He was conning them. He didn’t want interference from anybody. Any studio executive, he could not stand them to come on the set and watch what he was doing because he would not let that happen. So this way we basically escaped letting the studio correct us and go back and reshoot things to make it look like all those movies in those days with Technicolor, saturated colors. We loved so much the way it looked, but the studio hated it. They didn’t want anything new.

I don’t think we ever really had a real argument. I loved him so much. I listened to him and I learned a lot from him. I learned how to use the zoom, because he really used the zoom way before anybody else was using the zoom—the way he used it in McCabe, for example. Because he loved to dolly and zoom at the same time he could actually create live, dramatic moves. I mean that was the whole idea. He showed me a couple of times, the very first week I was there to learn what he wanted. After the week was over, he let me do it. He realized that I learned what he wanted—to tell me what it should look like as far as composition goes, as far as the camera moves go, and then from that point he hardly ever even looked into the camera.

Afterwards I used the zoom lens all the time because it’s convenient, it’s fast, you get everything that you want. Yes, it’s not as sharp as regular lenses, but who wants sharpness anyhow? I was always on the soft side of things. I liked it not as brutally sharp as many cinematographers do.

* * *

ALAN RUDOLPH (director): Bob wants everybody to come to dailies for the collective energy, the collective thrill. But it’s more than that. He wanted a democratic sense where everybody was rooting for everybody else, where you didn’t bring your ego to dailies. If you’re sitting there and you watch some minor character doing something—’cause Bob’s camera would find that person doing something kind of clever—even if you were the big star you’d support it, you’d love it because you knew it was going to be part of the fabric. There was this camaraderie, this spirit, so that nobody felt more important than anybody else. He really wanted it to be a team rooting for each other instead of about me and mine.

VILMOS ZSIGMOND: He always liked to have a lot of people see dailies. Sometimes he had forty people. Everyone from the actors to the crew to the extras. And their children. Dogs, cats, roaming around in the screening room. It was like a happening every night. And we had drinks, you know. Some people were smoking. Bob was into Scotch and everything. Those were really, really glorious days. It was the end of the sixties, basically.

KEITH CARRADINE: He expected you to be there. That was a part of the communal experience of filmmaking as far as he was concerned. You’d show up on the set and you do your work and also you come and you watch everyone else’s work. They’re going to watch your work and you’re going to watch their work and we’re all going to watch each other’s work and it’s all going to be great. Julie didn’t go. She didn’t like to look at herself. Somehow she got away with that. I know there are people who would not go to dailies because they just—they were afraid it would affect how they approached their work, and Bob would grudgingly accept that, but he didn’t really buy it.

JULIE CHRISTIE: I don’t like parties, for a start, especially when everybody is more or less congratulating themselves. These are congratulatory parties. I can’t bear watching me do things all wrong. I can’t bear it. He’s someone whose approval everybody sought. I think he made it clear when his approval wasn’t wholly there. I think I could have sucked up to him more by being at the rushes. But I just hate them, so there’s no point in doing that.

* * *

JULES FEIFFER (writer and cartoonist): Within a few miles of each other, these two marvelous films were being shot at the same time—McCabe & Mrs. Miller and Carnal Knowledge. As different styles as possible, because Mike Nichols organizes everything and knows everything that’s going to happen and plans it all; that’s the way he thinks and that’s the way he works. Altman works in a pigpen.

Altman loved parties and he loved to party. He invited me to a party one weekend and I invited everybody from the company. Jack Nicholson and Artie Garfunkel were the only two that wanted to come along. We stood outside the party and I still remember Jack looking at Warren Beatty and saying, “He’s the right height for a movie star.” He said, “I’m too short.” And I introduced them.

* * *

RENÉ AUBERJONOIS: I couldn’t believe when Bob said he was going to use Leonard Cohen for the score. I thought he would be using fiddle music and flute music. That was the genius of it. Now it’s unimaginable that that wouldn’t be part of that film.

LEONARD COHEN (singer and songwriter): The first time I heard from him I was recording a record in a studio in Nashville. I was living in Tennessee, a little town outside Franklin called Big East Fork. I had come into Nashville early one day and gone to a movie called Brewster McCloud. It was a grand movie, as you know. There was a phone call. Somehow he tracked me down to the Columbia studios in Nashville.

He said, “This is Bob Altman. I’d like to use your songs in a movie I’m making.”

I said, “Okay, that sounds good. Is there any movie you’ve done I might have seen?”

He said, “M*A*S*H.” I told him I hadn’t seen it. But I heard it had done well. Then he said, “I also did a small movie that nobody saw—Brewster McCloud.”

I told him, “I just saw it this afternoon—I loved it. You can have anything you want.”

I saw McCabe under very bad circumstances, and he warned me that the circumstances were bad. He invited me to a screening in New York and it was for some executives of a large studio. The atmosphere was tense and the projection was bad and the sound was very bad. And I didn’t have a positive feeling about it. Then, later, I went to a theater and it was glorious. I phoned him—I felt that I had to rush to a phone to tell him.

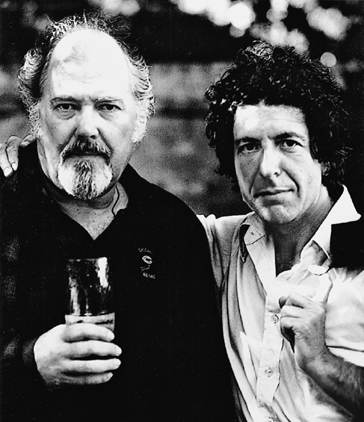

With Leonard Cohen, several years after Cohen’s music became the sound track for McCabe

* * *

RENÉ AUBERJONOIS: When M*A*S*H opened, Bob and I were walking down Eighth Avenue and he said, “Did you hear that?” He was talking about the people who were walking uptown as we were walking downtown. The conversations that we would hear pieces of—“and she needs a hysterectomy” … “his brother-in-law.” He said, “That’s the key to it. You don’t need to hear everything people are saying to know the world they’re living in.” That’s what he was always looking for, and that’s what he did in McCabe & Mrs. Miller. That drove critics crazy. And now it’s recognized as a breakthrough.

VILMOS ZSIGMOND: The sound track was very, very courageous because he deliberately made the sound so too many people are talking at the same time. I even questioned him myself. I said, “Robert, the sound mix, I can’t understand what they’re saying.” He said, “But have you ever been in a bar where there’s so much noise, so many people arguing, do you hear everything that they say three tables away? Well, that’s what I try to do. That’s exactly what I want to have, the feeling of reality. Not that clear, perfect, beautiful sound recorded on a sound-stage.”

He recorded on sixteen tracks. He needed the separation of the tracks, because in the mixing stage, he could actually bring one forward and leave the others in the back. So he would select which voice should be dominating and the other ones secondary. That was brilliant, and nobody else used the sixteen tracks in those days, only music recording did.

JOAN TEWKESBURY: Warren was used to clean, Hollywood sound, and Bob was encouraging a mess. And yes, there were drawbacks to that. But there was also Bob fighting—literally fighting—with the mixer to pull stuff out, and he couldn’t do it. It was frustrating for him too, but I think probably more frustrating for Warren because he was used to a whole different kind of technology.

JULIE CHRISTIE: The sound? I thought that was how Robert liked it. I know that the sound is on top of other sound, all multilayered. It’s not doing what films have done more or less, which is each person talking after another so the audience can hear every word. Robert was into creating more of a tapestry sound. It never mattered what anybody said. It gets the atmosphere. So when you’re in a bar you really get it.

KEITH CARRADINE: Bob was developing his style, a sort of cinema verité approach to the way people actually talked to one another. People don’t stop and listen, people talk over one another all the time. He mastered that technique and there is a heightened sense of reality you get when you see one of Bob’s movies because of that. I think Warren was very, very mistrustful of what he was doing in that regard. He was afraid that no one would be able to hear, no one would be able to understand the movie.

* * *

JOAN TEWKESBURY: During McCabe, I remember Aljean Harmetz coming to do an article about Bob for The New York Times. We were in the car and Bob was railing on about something involving her. I can’t remember exactly, but it wasn’t very complimentary about her—and she was in the backseat! When he realized, Bob was like, “Oh shit.” And she still was worshipful in that article.

KATHRYN REED ALTMAN: Joan’s got that wrong. That wasn’t Bob. That was Tommy Thompson. He was the one driving the car.

Aljean Harmetz, story headlined “The 15th Man Who Was Asked to Direct ‘M*A*S*H’ (and Did) Makes a Peculiar Western,” The New York Times, June 20, 1971: It is 4:30 on a Friday afternoon in late December, and the Canadian darkness has fallen like a stone. Water pours down Robert Altman’s Mephistophelean beard, and an incongruously thin string of love beads circles his massive neck. At 2 a.m. the preceding night he lurched to bed, a last glass of Scotch in one hand, a last joint of marijuana in the other. But the indulgences of the night have no claim over the day. He was the first man on the set in the winter darkness of 7 a.m. He will be the last man to leave in the slippery frozen twilight. …

In the few hours of daylight, he has completed 34 camera setups. He is pleased with himself, and he does not try to hide it. Later tonight, swacked on Scotch, grass, red and white wine, he will announce, “I was so good today it was fabulous. I embarrassed myself.”

At 46, Robert Altman is Hollywood’s newest 26-year-old genius. The extra 20 years are simply the time he had to spend, chained and toothless, in the anterooms of power—waiting for Hollywood to catch up to him. While he was waiting, he made a million dollars as a television director and spent two million; fathered four children on three wives; gave up the last remnants of Catholicism for hedonism; and occasionally lost $2,000 in a single night in Las Vegas without losing half an hour’s sleep over the money. Eighteen months ago, Hollywood caught up—with a vengeance.

* * *

DAVID FOSTER (producer): Warren and Bob started to work together about the character. Bob and Warren got along and then something went astray. Warren was very bright and is still a bright guy. We got him at a time when he was a writer, producer, director, star, marketing maven, and he wasn’t going to do that in this picture. We had a director, and we had two producers, me and my partner, Mitch Brower. He wasn’t going to do any of that. It was hard for him to accept. In his mind he was doing everything—he thinks that he directed himself. It’s just a load of bullshit. I just don’t know why a guy would say that. Even if it was true. Bob’s great facility as a director is he would get the actors to do the things he wanted them to do, but they thought they came up with the idea themselves.

I was trying to be a peacemaker. Bob was so smart—whatever was going on he would never show it to Warren. With me he would say, “That son of a bitch, I’m the director.” Bob was the director. Make no bones about that. The only actor he ever had a problem with was Warren Beatty.

RENÉ AUBERJONOIS: When Bob and Warren met he was really on the ascendancy. M*A*S*H had announced him as a major talent. Warren was at his peak as a major Hollywood star. It was like a meeting of two titans. Bob in his later films worked with a lot of celebrities. In the beginning he invented actors. His work with Warren Beatty was like a grain of sand making this pearl. There was a lot of tension there.

ALAN LADD, JR. (producer): He wouldn’t take Warren Beatty’s bullshit. Warren wanted to discuss every scene—Warren wants to negotiate over everything. Bob just wanted to get on with it.

JOHN SCHUCK: My experience with Warren was he was a perfectionist all right, but he’s such a subtle actor that there were lots of differences, you know? But I found him very, very easy. What I did sense overall was for some reason I don’t think they trusted each other.

JOHNNIE PLANCO (agent): Julie was always best on the first take. It took Warren fifteen, twenty takes to warm up. Julie would get a little less fresh. One night at three a.m. Bob said, “That’s it.” Julie was wiped out. Warren kept saying, “One more, Bob, one more.” Bob went over to Warren and said, “Look, Warren, I have to get up in three hours and I think we got the shot. But if you want, I’ll leave the cinematographer here and you can keep shooting.” Bob told me later, what Warren didn’t know was that there was no film in the camera.

Julie Christie and Warren Beatty at the premiere of McCabe & Mrs. Miller

VILMOS ZSIGMOND: I know that Warren for some reason didn’t like to work with Robert. Robert was probably too good, too strong, maybe, for him. He always thought about himself, Warren, that he’s the director, he’s a producer, he knows about everything. Maybe that was the conflict. I don’t know.

Warren was happy because he was in love with Julie Christie in those days. But he was not happy about himself I think, because Julie was such a great actor. She did it the first time like this—perfect. And the second time was still good. The third time, she gets bored by the thing. She doesn’t like to repeat. And Warren gets bored only after take ten. But he did a great job. I mean a fantastic job. With Robert’s help, of course.

I remember once Warren went something like forty-five takes. He started in the morning. It’s a long scene and he’s in his room and he’s talking to himself and he’s going on for like seven minutes, without a cut, actually. And we shot it with two cameras, and we shot it and we printed I don’t know how many times, but I know that we shot from eight o’clock in the morning until like ten o’clock at night. That one scene. Then after, I don’t know, forty-five takes, Warren said, “Let’s do one more.” And Robert said, “No, Warren, I think we got it on take seven. And if not, definitely on take nine. I’m not going to do any more shots. If you want to do some more, go ahead, but I’m going home.” Bob told people that Warren kept shooting? No, Warren actually got the message. He was ashamed, really. He wasn’t going to do it without Robert. See, Robert’s memories are, well …

But Julie was so great. My God, Julie was unbelievably beautiful and I was in love with her, but the terrible guy Warren was with her [laughs]. There’s this one shot when Warren is coming into bed, and before he goes in the bed Julie points to the money. Warren gets up and Julie puts the cover up to her eyes, and you see those eyes laughing, smiling. It’s such great acting, those eyes, you know? That’s why I fell in love with her like that.

JULIE CHRISTIE: Warren liked to be perfect. I liked to get the hell on with it. It’s all too painful—let’s get out of here.

You had two very different types of ego working in a small area. I’m not going to go any further than that. To my mind it’s Bob’s best film. It needed the tightness that Warren brought to it and it needed the expansiveness that Robert brought to it.

I think he’s a great director, a great, unique, adventurous, experimental, confrontational, provocative director.

JOAN TEWKESBURY: The thing that I watched that happened between them—which I thought was pretty good for both of them—was that Warren presented Bob with a kind of discipline and Bob presented Warren with a looseness and an ability to stretch or grow or have a sense of humor about some things that possibly Warren hadn’t been able to have before. It was really kind of lovely to watch that unfold.

Shelley Duvall, to Patricia Bosworth, from Show, April 1971: How’d I like working with Warren Beatty? No comment. ’Cept he’s difficult. “Pirate” and he didn’t get along at all. It was terrible. Warren shouting and cussing. Julie was nice. Warm. “Pirate” told me once, “You’ll make out OK in this business as long as you don’t take yourself seriously. If you do—you’re lost.”

ROBERT ALTMAN: We shot the whole picture in sequence…. I remember calling for a coat—it got chilly out there—and I thought, “Jeez, what’s the temperature?” And it was twenty-eight degrees and I just started seeing these snowflakes. I said, “Get the guys out here with the water hoses.” And these guys were out in their black slick raincoats spraying that water. The next day we’re up there and crystals were frozen on the trees, on the wagons, and it was just beautiful, fantastic, and it was just starting to snow softly. I ran to Warren’s trailer and he was sitting there in his makeup chair and I said, “Warren, get ready—this is beautiful.”

And he said, “We’re not going to shoot today.”

I said, “What are you talking about?”

He said, “Well, it’s snowing.” And he laughs and said, “What happens if it doesn’t continue?”

I said, “We don’t have anything else to shoot, so let’s just do it.” And it kept snowing and snowing and snowing.

VILMOS ZSIGMOND: This was the part at the very end when he decided to not flash the film. In the snow. Think about it—the whole movie basically is like a pipe dream, a fantasy, and now we are real, now McCabe is in danger. And that’s what happened. It becomes very stark, not hazy anymore, not foggy. It’s real.

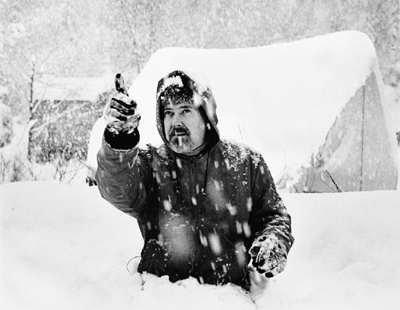

Directing on his knees in the snow during McCabe

JOAN TEWKESBURY: It made the movie. What would have been a gun-fight, just another gunfight in the town of Presbyterian Church, became this event in the snow. They were like animals tracking each other, and it’s fascinating to watch. This was when Bob was truly in his element the most, because he could just go out and make images. Warren’s death in McCabe, you know, sitting in the snow and freezing to death, never would have happened if the snowstorm hadn’t occurred.

* * *

MICHAEL MURPHY: Warren got mad because he thought the picture was too dark or something, and he yelled at Kathryn one night.

KATHRYN REED ALTMAN: When we had the premiere in Vancouver, Bob for some reason couldn’t go back up for that. Mike Murphy accompanied me and it was important that the actors show, because it was a fund-raiser, it was a big deal that we’d been committed to. We were up in the balcony of this big old beautiful theater and it was completely sold out. The sound was not good and it hadn’t been refined as I guess it was to some degree later. And Warren had been difficult, as his reputation had preceded him—with many, many takes and lots of controversy and wanted it done his way. The party was tented next door to the theater. The lights went up and we stood up in the balcony and were waiting to get out. I guess Julie had to be with Warren. Anyhow, they were coming down the stairs and I was coming out of the aisle and before he even got down to me he hollered and pointed his finger and waved it in my face when I got out. “You can tell your fucking husband …” Some very profane stuff, I can’t give it to you exactly. But it was all about the sound. And it was all so hurtful and it was so loud and it was so embarrassing and it was so tasteless, it was so thoughtless. And he just considered himself such a bon vivant.

ROBERT ALTMAN: Warren was terrific in the film. He had an attitude about it that I liked, and I thought he was right for it. … I don’t know why he and I didn’t get along too well.

Robert Altman, to David Thompson, from Altman on Altman: I don’t think Warren would be happy with anybody’s methods. That’s him. He wasn’t happy with McCabe: he didn’t like the way I mixed it, that you couldn’t hear every word, with a lot of lights. It was scary for him, because he hadn’t done that before and he wasn’t used to it. Yet he was the one who sought me out for the film. He chased the picture; I didn’t go after him to do it. He was great in McCabe—the film would not be what it is without him. … But he just isn’t much fun to work with. He’s kind of a control freak and he can’t let go because he’s a director, a producer, and was the last movie star of an era. The best thing he did was to bring Julie Christie in. These affairs of the heart help. Sometimes they’re better than the film, you know—“I got to do the picture, but I had to use the girl.” But this girl was better than he was.

DAVID FOSTER: I would say part of it was that Julie got nominated for an Academy Award and it drove Warren mad.

Dialogue from McCabe & Mrs. Miller:

JOHN MCCABE (Played by Warren Beatty): If a man is fool enough to get into business with a woman, she ain’t going to think much of him.

KEITH CARRADINE: You look at that movie now, it’s absolutely brilliant. I’d love to know if Warren can look at it now and go, “You know what? I was wrong.” It would take a huge man to say it, but Warren’s a big guy in many ways. He has room to admit that he was mistaken about that. I wonder if he will.

WARREN BEATTY (actor/producer/writer/director): Julie Christie and I were going to make Shampoo together, but we couldn’t get to a script. So I sort of gave myself a deadline and said, “If we don’t have a script by that date, Julie and I are going to do another movie.” I was offered a movie called McCabe. I didn’t know who Bob Altman was. I couldn’t have chased the film. I talked to Stan Kamen, who said, “He’s done a very good movie, M*A*S*H. You should go see it.” I had come back from London that day and I went to see it in New York and I thought it was terrific. I thought he did a terrific job. I went to the hotel and said, “Say yes, we’ll do the movie.” With all due respect, Bob Altman didn’t have the reputation at that point that he quite deservedly acquired. The picture was kind of me and Julie, on the basis of what we’d done. This thing that I chased the movie is quite an invention.

The movie came out of whatever Bob brought to it. It was extremely relaxed. Sometimes extreme relaxation can bite you in the tail. In the sound mix of the first two reels, it bit.

I attribute the whole making of the movie to the art direction with Leon Ericksen and the whole thing to Bob’s approach to work. And what I have called his flexibility. He immediately saw in Julie Christie—who was totally enamored of him—that he had a great thing here. “Let’s make her English and go with the Cockney rhyming slang.” I always felt that one of Bob’s greatest gifts, maybe his greatest gift, was that he knew talent when he saw it, and you can see it throughout his movies.

That’s the fun part—having the freedom to be loosey-goosey—and so I felt a little bit required to be structural and conventional in the circumstance, which I didn’t mind being. I felt it was very respectful of him to sort of defer to me in that area. And when I say defer to me, I mean welcome my contributions. Together we had a really constructive relationship. I felt he knew how to deal with me in the most constructive way possible, and out of the dialectic in a situation like that comes quite a bit of creativity.

I couldn’t agree more about Leon Ericksen. It was a brilliant job on the part of Leon and Bob to have built that town the way it was and have it come to fruition the way it did. I think that Bob was an extremely talented man who was really gifted at seeing what actors brought to him. Same with a cinematographer in the case of Vilmos or the other cinematographers he worked with. I thought Bob’s flexibility was wonderful. There were times when that flexibility, I felt, needed to be pinned down a little bit. I thought that the dynamic, the end result, was good. I thought it was very intelligently cast on his part.

I didn’t control that movie. I participated actively. When they wanted to flash the film, they flashed the negative. I said, “Why flash the negative? You can never retrieve it. Why don’t you do it in the printing?” They said they wanted to flash the negative—okay, do what you want to do. It seems strange to me. You want to get rid of information on the negative that you might someday want?

Why would I say something to Kathryn Altman, who is just the loveliest thing? Why would I do that? I’m a nice, polite boy, particularly with an innocent bystander.

That screening was not in Vancouver. It was in Los Angeles. And that’s just not my style. I can’t imagine saying that to Kathryn Altman. Why would I do that to Kathryn Altman? That just seems totally rude. It’s just not possible, and had I done that Julie Christie would have hit me over the head with a hammer. It’s just not possible. What I said was directly to Bob Altman.

It was at the end of the screening. I remember we were in a balcony and I said, “I can’t hear”—I might have said “a fucking word”—“in the first or second reel.” There were lines, particularly in the beginning, that needed to be clear so people will know what is going on. I didn’t want to really hear the background dialogue over the foreground dialogue. I said, “Is there any way you can change it before it goes into theaters?” He said he didn’t think so but he would check into it. I was very angry with Bob Altman and it’s the only time that I ever did that with him.

It seemed it was an irretrievable situation and I thought it was—he was a relatively new director. I don’t know that the picture’s financing was dependent on me, but I was an established producer. It was careless. I don’t think that he meant to do that. I think it simply slipped through the cracks. There’s no question he would have remedied it if there had been time. I thought it was complacent to not show it to me or somebody else earlier than he showed it. And I probably overreacted because I was so fond of the picture and we had all worked very hard on the picture. In the long run when you mix the sound in a picture everything you’ve done for a lot of months is dependent on a couple of days.

If you have dialogue and people can’t hear it, it makes people crazy. If you do that, then you have to let the audience off the hook—put music over it so they know they don’t have to work on it. You couldn’t understand the dialogue in the first two reels, and that’s quite a bit of time, and that’s certainly enough time for the audience to give up on the movie. It wasn’t that you couldn’t hear every word. I thought you couldn’t hear any word. I don’t want to denigrate the job that Bob did. I thought he did a wonderful job. But I thought that the mix was extremely unfortunate because people would quit on the movie after a reel or two or three.

I pretty much like everything else about the movie. I thought it was a brilliant choice on Bob’s part to have Leonard Cohen’s songs. Bob did all that. Bob was a very, very collaborative filmmaker. He was spectacularly collaborative. That’s why I really enjoyed working with him. I thought he wanted to get the best—he wanted to get it up on the screen. He wanted the result to be as good as it could be. And I felt that truly Bob was asking me to be as active as I could. And I responded. I worked very hard on that movie. I worked at night on that movie.

I think it’s a very, very good movie. John Huston once said to me he thought it was the best Western he had ever seen.

* * *

DAVID FOSTER: The picture’s coming out. We’re in New York at the Regency Hotel. Warren and Julie and Kathryn and Bob and my wife and I, we have a big screening at the Criterion Theater in Times Square—and the sound is a disaster. We reserved a table at the Russian Tea Room. Bob was beside himself. This is going to sound like a joke—he ran out into Fifty-seventh Street and said, “I’m going to get a cab and I’m going to JFK and I’m going home to Kansas City to see my mother.”

I said, “C’mon, get back in here. We’re having a party, for God-sakes.”

I must confess, the sound was fucked up. I kept saying, “What did he say? What did he say?” But that’s what Bob wanted.

ALAN RUDOLPH: When we were doing California Split, Bob said, “Listen, I’ve got a lot of phone calls from Warner Brothers. Warren Beatty wants them to remix, he thinks McCabe should be rereleased, and they want to remix it. I won’t have anything to do with this but I’m going to send you to watch the movie with Warren Beatty and then report back.”

So I sat in the Warner Brothers screening room with Warren Beatty, the first time I’d ever met him in my life, and that may be the last time, watching McCabe & Mrs. Miller with him. And he kept saying, “I don’t understand that. I can’t hear that. Can you?”

And I said, “That’s what I like about it.”

He said, “The footsteps are louder than the dialogue.”

I said, “Yeah, but that’s kind of good. I don’t know if it’s important to hear what they’re saying.” I was Bob’s party line, you know, and Beatty was all frustrated with me.

I think Bob would never admit that he wished that the sound quality was better, but what he loved about it was it felt real. It certainly didn’t detract from the heart and soul of that movie except it made it annoying for ears that weren’t in tune to that.

* * *

MICHAEL MURPHY: Look at all his pictures, ninety-nine percent of them are American society, Americana, these subtle moments when everybody moves into McCabe’s town and you see like six Indians leaving. It’s all the human condition, I guess. But he was very much like that. Julie at the end of McCabe goes down and gets on the pipe, you know? I think you see it again and again. He always sort of finds that place to go.

KEITH CARRADINE: Why did Cowboy have to die on the bridge? Well, that was the core of the movie. The movie is really about loss of innocence and the savagery of the natural world, and I think it was a human reflection of the savagery of nature. I mean, wolves go out and kill because they’re hungry. People kill for the same reason, it’s just a different kind of hunger or fear. That moment where my character is an innocent victim of random and arbitrary violence, that was the denouement of the film, really, that’s where the whole film turned.

VILMOS ZSIGMOND: It’s an incredible movie. If you watch it today, it’s as good today if not better than in the old days. If you really look at it politically, the message is there for all times. Capitalistic society, whoever is the power and buyer of things, is in control. The little people don’t have much chance. McCabe tries to believe they do, to be a hero, but you know how it ends.

MARTIN SCORSESE: McCabe gave you a different point of view completely of what the American experience was at that time. It was, in other words, very different from the Westerns we had grown up viewing.

Here you have a movie coming into the American mainstream and the hero winds up dead, killed by a bully and a Western gangster, so to speak. And the heroine of the film, the last time you see her she’s in an opium den and she’s floating away. It’s very moving. We’d never really seen the West that way.

DAVID FOSTER: Pauline Kael was so insistent on making people aware of this picture. She went on The Dick Cavett Show. He said, “Seen any good movies lately?” She went off for like ten minutes on network television. People were raving about it.

Peter Schjeldahl, essay headlined “McCabe & Mrs. Miller: A Sneaky-Great Movie,” The New York Times, July 25, 1971: To say that McCabe & Mrs. Miller is no ordinary Western is to put it very mildly. It is no ordinary movie. As a Western, it rather seems to have been made by someone, a sensitive and ambitious artist, who never saw a Western before, who had no idea how such a thing should be done and who thus had to put the genre together from scratch.

Julie Christie, as Mrs. Miller, in the opium den

This can be confusing until you get the hang of it, which a lot of critics haven’t. Only Pauline Kael in The New Yorker, of those I’ve read, has zeroed in on Altman’s studied avoidance of convention and has identified it as a key to the film’s wonderful, bemusing power. The result of this audacious strategy is a brilliant work of art about the American past, a work to which “a slightly dazed reaction is,” as Miss Kael concludes, “the appropriate one.”…

It is a film which seems to have, in addition to sound and image tracks, a kind of “feeling track,” a continuous sequence of fugitive emotional tones that must be laid to the extraordinary sensibility of Altman, whose mind looms in his work like the Creator’s in a sunset.

* * *

DAVID FOSTER: It didn’t do much business. It was so disappointing.

Dialogue from The Player:

GRIFFIN MILL (Played by Tim Robbins): It lacked certain elements that we need to market a film successfully.

JUNE GUDMUNDSDOTTIR (Played by Greta Scacchi): What elements?

GRIFFIN MILL: Suspense, laughter, violence. Hope, heart, nudity, sex. Happy endings. Mainly happy endings.

JUNE GUDMUNDSDOTTIR: What about reality?

ROBERT ALTMAN: It was a very unsuccessful movie. The studio was wrong about the marketing when they put it out. The audience had to catch up. It was ahead of its time, as they say. Later it became what they call a cult film. To me, a cult means not enough people to make a minority.