ARNOLD ROTHSTEIN LAY IN HIS GRAVE, but the inevitable questions remained: Who killed him? Why? And what, if anything, were New York's duly elected authorities going to do about it?

George "Hump" McManus, having rented Room 349 and summoned A. R. to it, remained suspect number one. But no witnesses placed A. R. in the room, said Big George fired the shot, or connected him to the murder weapon.

McManus remained in hiding, as did his bagman, Hyman Biller, and his chauffeur, Willie Essenheim. District Attorney Banton rounded up what supporting characters he could, Sidney Stajer and Jimmy Meehan, the Boston brothers, and Nate Raymond. They didn't know a thing.

Or so they said.

On Friday night, November 17, cops arrested three hoodlums associated with the dead man: Fats Walsh, Charles Lucania (Lucky Luciano), and Charles Uffner. Detained in connection to an October 1928 payroll robbery, the charges were mere pretext. Police focused their questions on A. R.'s murder. Luciano and Uffner were prominent narcotics dealers, Walsh, Arnold's former bodyguard. Walsh pled ignorance regarding Rothstein. He didn't know a thing about A. R.'s losing money at cards. Hadn't seen him since the Thursday before the shooting. "Rothstein," he said with a straight face, "never was the associate of gangsters, as has been reported. It is silly to say that he was connected with any drug smuggling ring."

A few days later, A. R.'s old crony, judge Francis X. McQuade, dismissed all of the robbery charges against the trio.

Another early suspect was Broadway character Willie "Tough Willie" McCabe, alternately nicknamed "The Handsomest Man on Broadway." Nate Raymond told investigators that he had "let McCabe in" on a share of his $300,000 winnings from Rothstein, and the district attorney's office suspected that McCabe had threatened A. R. to pay up. It was believed that shortly after the game at Meehan's, McCabe twice visited A. R.'s West 57th Street offices, staying the last time for an hour and a half.

McCabe denied everything. Raymond hadn't promised him anything. Providing an airtight alibi, he hadn't even been in New York between September and Election Day. He had been in Savannah, Georgia, trying to start a dog track.

"It's Raymond's word against McCabe's," said District Attorney Banton to the press, "-which are you going to believe." He believed McCabe.

Cops searched everywhere for Rothstein's killer, everywhere except where George McManus hid. Detroit authorities questioned two men originally held on robbery charges. The reason: They drove a car with New York plates. The duo had actually been in Detroit for the past two months. In Philadelphia cops arrested a Frankie Corbo, wanted for a 1924 New York pool-hall murder, and seriously pondered whether to grill him in regard to Rothstein's death. Briefly, New York police suspected Legs Diamond's involvement; but, like Willie McGee, Diamond possessed an airtight alibi: he was in California in early November.

While police grilled the wrong people and pursued their slow motion search for Hump McManus, Banton's office began building a circumstantial case against him. Their strongest evidence was beautiful in its simplicity. Sunday night, November 4, 1928, was cold and damp. Arnold Rothstein walked from Lindy's to the Park Central, clad in a blue chesterfield overcoat. When he appeared in the hotel's service corridor, he had none. It was never found. In the closet of Room 349, detectives discovered another overcoat-not Rothstein's, but remarkably similar to it. Same color. Same fabric. Even the same tailor. But it belonged to George McManus; his name was sewn into its lining. The following conclusion appeared inescapably: A. R. went to Room 349, removed his coat, was shot and, in the ensuing confusion, a drunk and panic-stricken George McManus grabbed the wrong overcoat-Arnold Rothstein's-and fled.

But police possessed little else. No one saw Arnold Rothstein in Room 349, or entering it, or even entering the hotel itself. He had lost a significant amount of blood-but, remarkably, none externally. Thus, no blood could be found in Room 349, in the third-floor corridor, or in the stairwell.

Police possessed the murder weapon but couldn't connect it to McManus, his bagman, Hyman Biller, his chauffeur, Willie Essenheim, or indeed, any living human being. They possessed no fingerprints of value. Most had been obliterated. What few prints existed failed to match any on file. However, the official investigation reported that police had compared the prints to those of hotel or police department personnel only. It did not mention comparing them to those of the actual suspects.

Of course, police might also have compared Rothstein's fingerprints to the one pristine print they possessed, thus placing A. R. in the room. They didn't. Said the official police report on the investigation:

The only fingerprint which was not compared with the impression found upon the [drinking] glass was that of Arnold Rothstein, which might have resulted in definitely establishing that he had been in Room 349. During his lifetime, the fingerprints of Rothstein were not obtained [despite shooting three policemen!]. After his death, it was the duty of the Homicide Squad, under the regulations of the department, to have obtained these fingerprints. This, however, was not done and the body of Rothstein was buried, without his fingerprints ever having been secured.

And, of course, the victim had not talked-or if he had, those he confided in maintained their own discreet silence.

On Monday, November 19, a mystery witness appeared before the grand jury that District Attorney Joab Banton had assembled to investigate A. R.'s death, the best sort of witness as far as the city's newspapers were concerned-a blonde. "She appears to be a natural blonde," Banton observed, "about twenty-five years old, maybe less. She has light blue eyes."

Ruth Keyes was a twenty-three-year-old "freelance clothing model" married to an Illinois Central Railroad brakeman, visiting Manhattan on a "shopping trip," and registered in Room 330 of the Park Central. Husband Floyd conveniently remained in Chicago.

On Saturday, November 3 she made new friends. "Saturday night," she told Chicago reporters, "the night before the shooting. I went into the hall to find a maid. In the hall I met a man who had a room on the same floor. He seemed to be quite nice and, I suppose, I flirted with him a little. His name was Jack, he said, and he wore a blue suit.

"Along about 4:30 Sunday afternoon Jack called my room and asked me to join him and another man in his room, No. 349, and have a drink. I don't seem to remember what the other man looked like. At about 6 o'clock I left them there."

Nothing about Mrs. Keyes's new acquaintances indicated they planned anything significant-or fatal. "Jack" (i.e., McManus) repeatedly begged her to stay and peeled $50 bills off his bankroll to encourage her. He did what he could to please-dancing, singing, catching ice cubes in his drinking glass. "It was," giggled Ruth, "all quite silly." She checked out of her room at approximately 7:00 P.M. on Sunday night, November 4, 1928-about three-and-a-half hours before Arnold Rothstein's arrival.

Mrs. Keyes promised investigators she'd do all she could to help, though positive identifications were difficult. "Everyone had had a lot of drinks," she said, "and that makes them look different." She was sure Arnold Rothstein had not been among her new acquaintances. She met a lot of men in her line of work; A. R. was never among them.

Meanwhile, police had proceeded in slipshod fashion from the beginning of their work. When detectives arrived in Room 349 on the night of the evening, the phone rang. They allowed house detective Burdette N. Divers to answer-and to obliterate any fingerprints upon the instrument. Leaving the room, they posted no guard, potentially allowing anyone to enter, remove evidence, or wipe clean any remaining prints. Detectives delayed searching McManus' twelve-room apartment at 51 Riverside Drive until November 16-almost a full eleven days after the shooting. On arrival, they found it stripped of every photograph of the suspect. They also learned that sometime after 11:00 P.M. on November 4, McManus and his chauffeur, Willie Essenheim, had stopped by the apartment. Essenheim ran upstairs-and returned with a heavy winter overcoat for his boss.

While police halfheartedly sought A. R.'s murderer, others scrambled for his cash. The last will and testament Maurice Cantor placed under Arnold's feeble hand amply provided for Cantor and coadministrators Bill Wellman, and Samuel Brown, but was less generous to Rothstein's family or his widow. On March 1, 1928 a still-very-coherent Arnold Rothstein had employed attorney Abraham H. Brown to draw up a will leaving half his estate to his wife. The will he signed as he lay dying reduced Carolyn's share to one-third-and left the income from one-sixth of the estate for a ten-year period to Inez Norton. After ten years, Inez's one-sixth reverted to Cantor, Wellman, and Brown. The idea pleased neither Inez nor Carolyn. Inez wanted more, wailing: "He said everything would be mine!" Carolyn wanted Inez shut out completely. "We will find no trouble ... in cutting Miss Norton off without a penny," her attorney Abraham I. Smolens threatened. "She got enough from him when he was alive, without trying to horn in on a widow's share."

Abraham and Esther Rothstein, and Arnold's surviving sister, Edith Lustig, got nothing. Brothers Edgar and Jack received just $50,000 each. On November 14, 1928, Abraham Rothstein petitioned Surrogate Court Judge John P. O'Brien to overturn Rothstein's deathbed will.

Left • Heavyeight champion Gene Tunney (center) with his manager Billy Gibson (left) and legendary boxing promoter Tex Rickard. Rothstein won $500,000 on the first Dempsey-Tunney fight. Did he and Abe Attell plot to make it a "sure thing"?

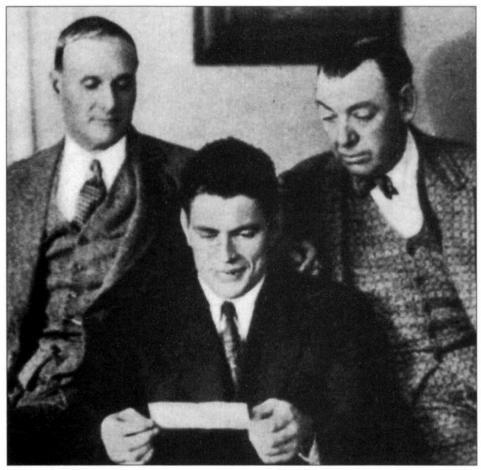

Below • Lindy's Restaurant on Broadway served as A. R.'s unofficial office. On the night of Sunday, November 4, 1928, a call to Lindy's summoned Rothstein to the Park Central Hotel and his death.

Above • Rothstein's mistress, showgirl Bobbie Winthrop, committed suicide in 1927.

Right • Arnold Rothstein's longsuffering wife, Carolyn Green Rothstein, filed for divorce prior to his death.

Right • Rothstein's last mistress, showgirl Inez Norton, stood to profit from his revised will.

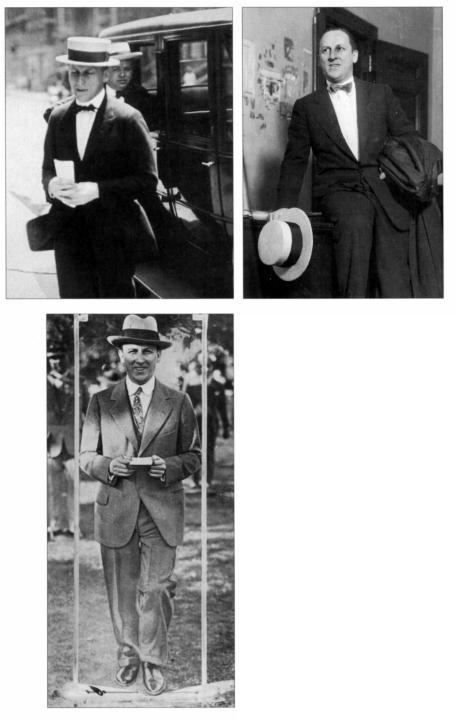

The Many Faces of Arnold Rothstein

Above left • Arnold Rothstein, all business, circa 1920. Courtesy of Transcendental Graphics.

Above right • Man about town.

Left • Sportsman at the track; note pressman's crop marks on photo and A. R.'s painted pants.

Above left • A. R. gave small time Broadway gambler Jimmy Meehan his gun before he walked to the Park Central Hotel-and his death. Above right Attorney Maurice Cantor drew up A. R.'s last will and got Rothstein's signature on it while A. R. was on his deathbed. Below • The first floor service corridor of the Park Central, where the mortally wounded A. R. was discovered.

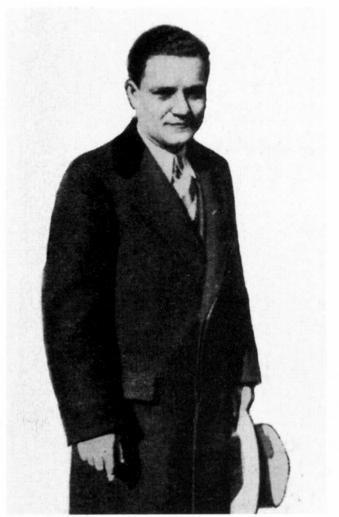

Excitable Park Central chamber maid Bridget Farry saw George McManus in Room 349 on the night of the murder.

Mayor James J. "Gentleman Jimmy" Walker knew A. R.'s murder "meant trouble from here on in."

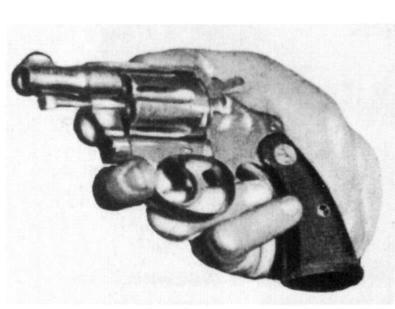

The Colt .38 "Detective Special" revolver that killed Rothstein-"the most powerful arm that can be carried conveniently in a coat side pocket."

Left • Cab driver Al Bender-he found the murder weapon lying on Seventh Avenue.

Above • Mayor Walker's mistress Betty Compton was with him when he got the news of Rothstein's death.

Above • The Park Central Hotel-"A" marks Room 349, "B" marks the spot on Seventh Avenue where the murder weapon was found. Courtesy Library of Congress.

In late 1929 George McManus (at right; shown with his attorney James D.C. Murray) faced trial for Arnold Rothstein's murder.

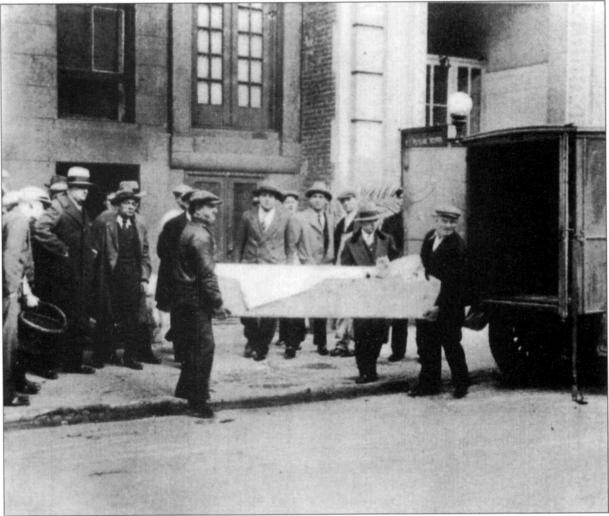

Rothstein's lifeless body being carried from the Polyclinic Hospital on the morning of November 5, 1928. Courtesy Library of Congress.

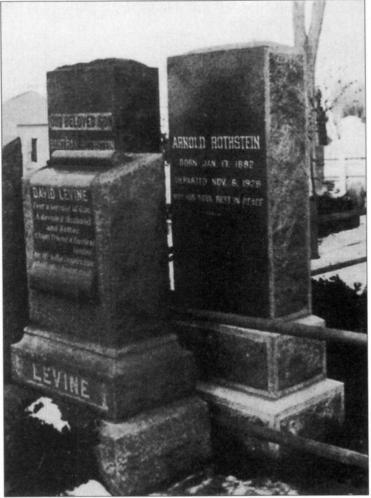

Arnold Rothstein's grave, Union Field Cemetery, Queens. To the left is his brother Harry's.

Thus began the financial scrambling. City and federal investigators pawed through A. R.'s home, his office, and through a series of safetydeposit boxes, expecting to uncover millions in cash, in jewels, in bonds. Trustees of Nicky Arnstein's bankruptcy, hoping to finally recover $4 million in still-missing Liberty Bonds, initiated their own search through A. R.'s effects.

Not surprisingly A. R. hid his cash in a wide variety of ways, hiding assets in accounts and holdings using twenty-one separate proxies: his wife Carolyn, his late girlfriend Bobbie Winthrop, Sidney Stajer, Tom Farley, Fats Walsh, Sam Brown, attorney Isaiah Leebove, drug smuggler George Ufner, fight promoter Billy Gibson, and assorted other goons and stooges.

Investigators learned that A. R.'s financial empire had degenerated into a finely tuned, but ultimately unstable house of cards. While he lived, it had its tensions-millions of dollars tied up in real estate, drug deals, and high-interest loans to shady characters. But despite increasing difficulties, A. R. managed to hold it all together. With his death, the wheels fell off. Mortgages came due. Drug runners went off on their own, taking narcotics shipments with them. Gambling debts owed A. R. suddenly didn't have to be repaid. Loans, recorded only in indecipherable symbols in Arnold's little black account books, could safely be forgotten.

Mortgage payments of $115,000 were payable on the Fairfield. The Rothmere Mortgage Corp owed banks $140,000. Judgments and mortgage foreclosures against the juniper Holding Corp. amounted to another $42,000. A. R.'s numerous employees were owed $152,000 in unpaid salaries.

Herbert Bayard Swope's paper, the World had an explanationgreed:

The irony of it is, according to one of Rothstein's associates, that in an effort to pyramid his fortune, an effort that took the semblance of greed within the last few years, he fairly wrecked it. To capture the highest possible interest on his loans he accepted friendship for collateral. Now that he is dead, it seems the particular friendship upon which Rothstein relied will yield scant dividends to his heirs.

Political interests appeared on all sides. There was, of course, Assemblyman Cantor himself. Cantor, Bill Wellman, and Inez Norton hired State Senator Thomas I. Sheridan, a Democrat from Manhattan's 16th District, to protect their interests in Rothstein's estate. Another state senator, Elmer E Quinn, from Jimmy Walker's old 12th District, represented Fats Walsh. Estate coadministrators Cantor, Wellman, and Samuel Brown engaged attorney Nathan Burkan, Tammany's leader in the 17th Assembly District.

The most significant political ties belonged to George McManus, whose Tammany connections approached those of Rothstein himself. At one point Big George even operated games out of City Clerk Michael J. Cruise's East 32nd Street political club. His best relations, however, lay with West Harlem's Tammany chieftain, James J. Hines, now the organization's most powerful and corrupt local leader.

Hines's father had been a blacksmith and Tammany captain, and Jimmy followed both professions, shoeing over 40,000 horses (160,000 hooves; 1.28 million nails) and, at age seventeen, taking over his father's election district. He became alderman at age thirty, and 11th Assembly District leader at 35. Hines ruled through usual Tammany methods-both good (hard work and charity), and bad (vote fraud and graft). He awoke early, spending mornings listening to constituents' woes. Each afternoon (when not at the track) he did what he could to help:

A man comes to me, any man. A man I never saw before or heard of. I don't know whether he's Republican or Democrat, but he wants something, and even before he's through talking, I am trying to see if there isn't some way I can satisfy him. Well, I do satisfy him. He votes for us. So do all his relatives. You know they do. He's grateful. He feels good toward us. We give him something he wanted.

Some voters just wanted cash. Hines provided that too, especially on election day. The Amsterdam News, one of the city's two black papers, explained:

Of the 35,000 votes in Mr. Hines' district, nearly 5,000 are colored. They loved Hines dearly for the most part because he always looked after members of the district club [the Monongahela Democratic Club on Manhattan Avenue] ... For years, during his heyday, Boss Hines, as he was called, gave out $1 bills two nights a week at the clubhouse.

Whites also lined up for Jimmy's largesse. In November 1932, thousands assembled outside Hines's Monongahela Club. Each received a dollar and the advice. "Vote every star"-cast your vote for every candidate on the Democratic line.

Such beneficence required immense amounts of nontraceable cash. True, Hines owned a firm, which occasionally did city business, but payoffs were his main source of income. With the advent of Prohibition-and, later, the Harlem numbers racket-his haul became enormous.

Virtually every mobster in town paid tribute to Hines. Big Bill Dwyer, Frankie Uale, Owney Madden, Legs Diamond, Lepke Buchalter, Gurrah Shapiro, Lucky Luciano, Dandy Phil Kastel, Frank Costello, Joe Adonis, Frank Erickson, Meyer Lansky, and Larry Fay-as well as dozens of lesser-known and less-powerful punks-did business with him. Arnold Rothstein operated the gambling concession above the Monongahela Club.

With immense wealth at his disposal, Hines's power stretched far beyond West Harlem. Even the most powerful learned to fear him. Early in 1918, one Louis N. Hartog needed a source of glucose for British beer brewers. Hines suggested that Tammany overlord Charles Francis Murphy could assist in securing the necessary government permits. Murphy not only helped, he invested $175,000 in Hartog's North Kensington Refinery. The partnership soon soured, and lawsuits and countersuits followed. Murphy blamed Hines, and attempted unsuccessfully to drive him from power.

Hines possessed labyrinthine connections, especially regarding the selection of juries, and soon retaliated. Through Hines's machinations, a grand jury investigating wartime subversion turned its attention to wartime profiteering and indicted Murphy.

Murphy counterattacked when Jimmy sought the Manhattan Borough Presidency. Hines engaged scores of gangsters to harass opponents and repeat-vote, but the ostensibly statesmanlike Murphy played even rougher. Murphy's ally, district leader William P. Ken- neally, brutally beat Hines's top henchman and closest friend, attorney Joseph Shalleck. Two policemen stood nearby, doing nothing to stop him.

Jimmy lost the primary, and relations with Murphy remained hostile. But both still had business to do with the other. Their go-between was Arnold Rothstein. Of course, Rothstein's dealings with Hines went far beyond acting as his intermediary. As Hines performed favors for his constituents, Rothstein assisted Hines and his associates. It might have been as simple as allowing Hines's wife, Geneva, to entertain friends at A. R.'s Hotel Fairfield-at no charge. Or pestering John McGraw for Giants season passes for Hines and his three sons. Or paying Hines's $34,000 gambling debt to bookmaker Kid Rags-one I. O. U. that A. R. never collected. However, their most ongoing connection was Maurice Cantor. Jimmy Hines owned A. R.'s last attorney lock, stock, and barrel.

When Murphy died, and the ineffectual judge George W. Olvany assumed Tammany leadership, Rothstein's power only increased, as Hines and a new rival, Albert J. Marinelli, battled for power behind the scenes. And something else was happening. While Murphy lived, politicians held sway over gangsters; but with both labor racketeering and Prohibition pumping money into mob pockets, power shifted from men with votes to men with money and guns. A. R. became more-not less-significant to men like Hines.

But now A. R. was gone, and in the minutes following Rothstein's shooting, Hump McManus needed Jimmy Hines more than ever. From a pay phone on the corner of 57th Street and Eighth Avenue, McManus called Hines. Jimmy didn't turn his back on his protege. Hell, he'd known and liked Big George since he was a boy. No, he wouldn't turn away. It just wasn't in him.

Hines ordered McManus to stay put. In due time, a Buick sedan pulled up. "Get in," called Bo Weinberg, Dutch Schultz's closest henchman. Weinberg drove McManus to an apartment on the Bronx's Mosholu Parkway, where he'd remain until Jimmy Hines decided on his next move.

Hines would expend a lot of cash to keep his friend afloat-some to cops, some to witnesses, some to McManus himself. As the New York Sun reported in December 1928:

The police were looking for McManus. They found out that his money was in the Bank of America. They watched the bank. Regularly, once a week, a check for $1,000, signed by McManus and made out to [Hines attorney Joe] Shalleck, came into the bank for payment. The police shadowed Mr. Shalleck, believing he must be in touch with McManus. Mr. Shalleck said he wasn't, but they called him before the Grand jury to explain. He did.

He said that along in last October McManus was pressed for money and came to him to borrow $20,000. He lent him that amount, and McManus gave him twenty signed checks for $1,000 each, predated, spaced a week apart, for payment. As the weeks came along Mr. Shalleck sent in the checks in rotation, and that's all there was to it. Nothing, as Mr. Shalleck pointed out, to do with who killed Arnold Rothstein.

Detective John Cordes was assigned to the Rothstein case the morning after the shooting, a logical choice as he knew McManus, Hyman Biller, and Willie Essenheim by sight. Cordes was among the NYPD's best detectives, the only officer twice awarded the departmental medal of honor. The first time he had foiled an armed robbery, while off duty, unarmed (he rarely carried a gun), and was shot four times (once by another off-duty officer who mistook him for a robber). Cordes was tough as nails. He was, however, yet another old chum of Jimmy Hines-as a boy Cordes had brought brewery horses to Hines's blacksmith shop.

On Tuesday evening, November 27, 1928, Cordes received an anonymous call summoning him the next morning to a barbershop at West 242nd Street and Broadway to "arrest a man." The caller didn't mention any names, but Cordes believed in tips. He'd be there.

Inside the barbershop, Cordes found a man getting a shave. Another fellow sat nearby.

"Hello, George," Cordes said to the man under the lather.

"Hello," McManus snorted.

"What'ryeh doin', George?"

"Why, I'm getting' a haircut and a shave. Have one?"

"I just had a shave, a close one," Cordes demurred. "How about you going downtown with me? You know you're in a pretty tough spot."

Of course, McManus would go downtown. After all, it had all been arranged.

"Sure," George responded. "I'll go with you in a minute; wait 'til I get a haircut and shave."

At headquarters, a well-groomed McManus admitted to entertaining Ruth Keyes in Room 349 on the night of the murder, but denied being there when A. R. was shot. He ducked out for fresh air-a bit of cold, wet air-without his topcoat. Learning of the shooting, he decided against returning for his coat. That was his story; he was sticking to it.

In the Tombs, he acted as if he were on vacation. In a sense, he was. Things were being taken care of. A story in the Sun reported on the accused killer's relaxed schedule:

With his alibi all polished up, he sits waiting in Cell 112, reading all the newspapers in town, because the prison rules won't permit him his books. He is in excellent health. He goes to the prison barber shop every morning to be refreshed by a shave, and bay rum and sweet scented talcum-to stretch out in the barber's plush chair. He eats three meals a day of the best there is in the prison larder-and that is quite good. He pays for special meals prepared by the prison chefs from the prison's full pantries. None of the bill of fare "slum" for him.

But perhaps Big George surrendered too soon. The prosecution possessed a witness he hadn't counted on: Park Central chambermaid Bridget Farry-who had previously worked for Rothstein at the Fairfield. She remembered A. R. and recalled him kindly. Hearing of his death, she mourned, "A decenter, kinder man I never knew, and I'll be lightin' a candle for him this very night."

Farry told police about Room 349 and the people in it: "I saw that the room hadn't been made up during the day and so I went there and knocked at the door. A big feller, Irish as Paddy's pig, comes to the door and says to me, `And what is it you want?' I tell him I'm the maid and I want to clean up the room. `It needs no cleanin',' he says.

"My eyes tell me different. There's these glasses and the dirty ashtrays and also there is a woman in the room. But it's none of my business and if he ain't wantin' the room cleaned up, it's less work for me and the better off I am for it."

When police showed the voluble Miss Farry a photo of the suspect, she did not hesitate: "Sure, he's the one. I'd know him anywhere."

The time of her visit: 10:20 P.M.-according to the New York Sun. This virtually cornered McManus. Ruth Keyes placed him in Room 349 before the 10:12 P.M. call to Lindy's. Farry put him there just eight minutes later. Her actions took courage. "I'm afraid they will kill me," Farry told reporters. "I've been hounded to death since the day of the murder. Strange men have stopped me in the hotel corridors, on the sidewalk and even at the entrance to my home. All of them tell me to keep my mouth shut, or I'll die.

"One man told me to grab a train for Chicago and be quick about it. Another reminded me of what happens to a `squealer.' "

The case was clearly shaping up. "Circumstantial evidence is the strongest kind in the absence of direct witnesses to the actual shooting... ," District Attorney Banton said cheerily. "There is no weak link at all. Every link is a strong one, a sound one."

George McManus didn't care what Joab Banton said. On November 30, the district attorney's office brought Hump into court to formally be charged with murder. Unfortunately, their case was not quite ready, and no charges were actually pressed. McManus didn't mind. He might have demanded his freedom, but that might have embarrassed his captors. There was no need for acrimony. After all, everyone was in this together. The tabloid New York Daily Mirror caught the spirit of the moment:

And McManus, who might have seriously embarrassed his prosecutor by forcing him to show on what grounds he was being charged with the capital crime, smiled and agreed to the delay.

He also smiled 20 or 30 times, nodded his head at his friends and even waved familiarly at detectives who are supposed to be trying to send him to the chair.

And of course, District Attorney Banton smiled, the detectives smiled, and all in all it was quite a happy occasion even though nothing happened.

Nothing happened for the longest time. True, in early December 1928, Banton indicted McManus, Hyman Biller, and "John Doe" and "Richard Roe" for first-degree murder, but police never located Biller, never identified "Roe" or "Doe." Yet, while McManus (a former fugitive from justice) gained his freedom on $50,000 bail on March 27, 1929, Bridget Farry languished in the Tombs. Someone clearly didn't like what she had to say about George McManus. So while an accused murderer walked city streets freely, she-unaccused of any crime-remained behind bars as a material witness. In April 1929 she finally got the message-and obtained her freedom on $15,000 bond.

McManus used his freedom to repay Jimmy Hines, working with Dutch Schultz, to reelect Hines's puppet 13th Assembly District leader Andrew B. Keating. McManus could sympathize with Keating. After Keating failed to shake down newly nominated Magistrate Andrew Macrery for a $10,000 bribe, he had campaign worker Edward V. Broderick beat the judge to death. Keating won his primary.

Meanwhile, investigators continued to sift gingerly through A. R.'s private financial files. District Attorney Banton assigned Assistant District Attorney Albert B. Unger and a police lieutenant Oliver to examine Rothstein's file, but soon Banton realized he wanted no part of their contents. There was too much there. Too many transactions. Too many names. Too many politicians. Too many cops. Too many celebrities.

Too much trouble.

Within two days, he announced to the press he was pulling Unger and Oliver off the case: "Mr. Unger called me up today and said it was a dreary job and would take at least three weeks."

This stunned reporters. "But," they asked, "you yourself told us ... it would take three weeks to sift the files."

Banton possessed a remarkable ability to remain unembarrassed. "I know ... ," he answered. "Mr. Burkan and his accountants have promised to turn over to me anything that is important."

Nathan Burkan, one of the city's better lawyers, was also among the nation's finest theatrical and intellectual-property attorneys. His clientele included major movie studios, as well as celebrities Victor Herbert, Charlie Chaplin, Flo Ziegfeld, and Mae West. More significantly, Burkan was also a Tammany leader and a member of Tammany's finance and executive committees-and served as an attorney for the Rothstein estate. Nathan Burkan's job would keep any incriminating documents from seeing the light of day, anything that might embarrass Tammany and its friends.

The case dragged on. Nineteen twenty-nine was a mayoral election year, and while Jimmy Walker appeared unbeatable, he didn't believe in taking unnecessary chances. McManus's trial was scheduled for October 15, but blueblood judge Charles C. Nott cooperated by announcing he would not allow a trial before the election, moving it to November 12.

Gentleman Jimmy's mistress Betty Compton was busy at rehearsals of Cole Porter's new play, Fifty Million Frenchmen. On election night, a cop appeared backstage. He lifted Betty into his arms and carried her outside. Walker and Police Commissioner Whelan sat in a parked car, grinning with excitement. Walker told her the news: He had crushed LaGuardia 865,000 votes to 368,000, carrying every assembly district in the city. It seemed safe to be bold, safe to finally bring George McManus to trial.

People v. McManus began on Monday, November 18. The trial was a farce. District Attorney Banton, by now a lame duck, never appeared in court. He delegated the case to his chief assistant, Ferdinand Pecora, and two other subordinates. James D. C. Murray-he was the one who had phoned Cordes to arrange Big George's surrender-represented McManus. Murray, brother of Archbishop of St. Paul-Minneapolis Gregory Murray, wasn't flashy, but he was brilliant-"as clever as a cat," an associate once remarked, "and will jump like a flash the minute he spots an opening. You can't turn your back on Murray for a second." Brilliance-plus Jimmy Hines's money and muscle-was a tough combination to beat.

Especially when facing a prosecution that lacked the will to connect the considerable number of dots they possessed-or that downplayed their significance. Call Ruth Keyes to the stand to paint a word picture for the jurors as to just how drunk and out of control George McManus was that night? Nah. Jim Murray already conceded their presence in Room 349-no need to summon Mrs. Keyes from Chicago.

Or consider this. The murder weapon, a vital link to Room 349, was thrown through a window screen in that room and found in the street below. Assistant District Attorney George N. Brothers deliberately cast doubt on his own train of evidence, saying in his opening argument: "whether this pistol was thrown out of the window or thrown in the street by some one in flight we don't know [emphasis added].

Or thrown in the street by some one in flight? The revolver had not been tossed away by anyone on foot or in a speeding automobile. It landed with such force-thrown as it were from a third-story window-that police ballistics experts had to straighten out its barrel before test firing it.

In any murder case, it is solicitous to establish motive, all the more so in one relying so highly on circumstantial evidence. In his halfhour, frequently interrupted, opening statement, Assistant District Attorney Brothers promised to "show that ill feeling resulting from this game [at Jimmy Meehan's] was the cause of the shooting of Arnold Rothstein."

Reasonable enough, except that every witness he produced-Nate Raymond, Sam and Meyer Boston, Martin Bowe, Titanic Thompsonnow swore there were no hard feelings. Meyer Boston portrayed his friend George as a cheerful loser, who laughed at setbacks and never displayed the slightest hint of anger. So spake them all, especially Red Martin Bowe:

MURRAY: Was the loss of this money anything to McManus?

BOWE: An everyday occurrence.

MURRAY: And was this a large sum for him to lose at one time?

BOWE: Well, I never knew him to lose over $100,000 at once, but he lost over $50,000 on a race once, I remember. . He always paid his losses with a smile.

So much for motive.

Banton's office managed to produce one surprise witness, Mrs. Marguerite Hubbell, a Montreal "publicity agent." She registered in Room 357, just five or six doors from McManus. Around 10:00 P.M., she heard a very loud noise, much like a gunshot, followed by excited voices in the hall. She convinced herself it was just a truck backfiring and returned to her newspaper. Well-spoken, conservatively dressed in a dark suit, she was a credible witness. Murray did little to challenge her story.

Gray-haired Mrs. Marian A. Putnam of Asheville, North Carolina, occupied Room 310. Leaving her room to buy a magazine she, too, heard a terribly loud noise, as well as loud, profane arguing. In the corridor she saw a man clutching his abdomen, his face contorted in pain, looking "mad." He didn't ask for help. Trying to avoid him, she offered none.

Murray crucified Mrs. Putnam. His investigators had peered into every aspect of her life-and there were a lot of aspects to peer into. The forty-seven-year-old triple-divorcee had officially registered at the Park Central with a "Mr. Putnam." But no current "Mr. Putnam" existed, only a Mr. Perry-and he was not her husband. Murray entered that into the record and raised questions of liaisons with other men, alleged larceny, and Volstead Act violations back in Asheville.

Detective Dan Flood testified that Mr. and Mrs. Sydney Orringer, a young honeymooning couple in Room 347, heard no shots. The unreliability of Flood's police work was proven the following day, when Sydney Orringer testified. Yes, he and his bride heard no shots-they hadn't been present when they rang out, not returning until 2 A.M. the next morning.

A fairly significant-but ignored-witness was young Walter J. Walters, former doorman at McManus's 51 Riverside Drive apartment house. He testified that shortly after 11:00 P.M. on the night of the shooting (A. R. was first noticed in the service corridor at 10:47), he saw Willie Essenheim enter the building, rush upstairs to his boss's apartment, and return with a heavy new overcoat.

The prosecution actually possessed a reasonable circumstantial case against McManus-or, at least, thought they had. Room 349 was McManus's room. A call from there summoned Rothstein to his death. Lindy's cashier Abe Scher could identify George McManus as the voice on the other end of the phone. Jimmy Meehan told investigators that A. R. showed him a note confirming that fact. Chambermaid Bridget Farry placed McManus and Biller in Room 349 at 9:40, just an hour before Rothstein was found shot and more significantly just thirty-two minutes before Abe Scher picked up the phone-and according to the New York Sun's account eight minutes after the call. The switching of the nearly identical overcoats placed both Rothstein and McManus in Room 349 at the time of the shooting. The murder weapon, found by cabbie Al Bender on Seventh Avenue outside Room 349, helped tie the weapon to that room. McManus's and Essenhelm's visit to McManus's apartment to retrieve a new overcoat-just half an hour after the shooting-simply reinforced everything else.

But the prosecution's case crumbled rapidly. Key witnesses recanted previous testimony. Park Central telephone operator Beatrice Jackson, who previously had identified McManus's call as occurring at precisely 10:12 P.M., now could no longer pinpoint its time. Abe Bender had informed Detective Dan Flood that the revolver he found on Seventh Avenue was still hot when he picked it up. On the stand he denied stating anything of the sort.

It was a small point, just enough to cast doubt on the prosecution's timeframe. What followed was far worse. Lindy's cashier Al Scher refused to identify the voice on the other end of the phone as McManus's.

Wednesday, December 4 saw two of history's worst prosecution witnesses testify. Jimmy Meehan told a patchwork of lies-about not fearing prosecution for weapons possession (his lawyer, Isaiah Leebove, had obtained immunity), about never having talked with Murray (Murray admitted it to Assistant D.A. Pecora), about A. R. showing him a slip of paper about seeing McManus at the Park Central.

Most significantly, he lied when he said A. R. had another gun the night of the murder. To investigating police and the grand jury, he told a simple story. A. R. gave Meehan his pistol and traveled unarmed to meet McManus. Now, Meehan told an exasperated prosecution team that Rothstein had two revolvers (Q: "Isn't this the first time you ever mentioned a short-barreled gun?" A: "I believe it is."). Meehan now claimed A. R. gave him a long-barreled gun but carried a short-barreled revolver, much like the murder weapon, to the Park Central.

Surpassing Meehan's performance was Bridget Farry's. She not only denied seeing McManus in Room 349-odd, since he admitted being there-but refused to admit identifying him in the Tombs lineup. Worse, she now swore McManus had checked out of the hotel, just after 10:00. She exhibited a furious, if comic, hostility to the prosecution-at one point accusing it of tendering her a $10 bribe (for cab fare after she had vociferously complained about the cost of riding down from the Bronx). Trying to avoid photographers as she left the Criminal Courts Building, Farry tripped in her green chiffon dress, and rolled down the steps into a parked car.

Farry's perjury caused Chief Assistant District Attorney Ferdinand Pecora to snap:

But take this matter of hostility on the part of our witnesses. That's the sort of thing we're up against all the time. We've got to put them on the stand to prove certain things. When they testify we can't very well control them. The men we've had up here so far, the two Bostons, Martin Bowe, Titanic Thompson all spoke with marked esteem of the defendant and seemed hostile to us. That's the way they've been all the time-even when they talked to me in my office last winter. It isn't that they're afraid of McManus, who sits twenty feet in front of them. They are his friends. They all like him. They think he's a pretty good fellow. And in that crowd I suppose he was-in his bluff way. And yet I believe he killed Rothstein.

Assistant District Attorney Brothers announced that his remaining witnesses would be police officers testifying regarding McManus's flight (placing in the jury's mind the question of why he fled), and police firearms expert Detective Henry Butts testifying about the murder weapon (making the point that the murder weapon had most likely been tossed from a room rented by the defendant; i.e., that Rothstein had not been shot in the service corridor). Judge Nott threw Brothers a double roadblock:

If the defense denies the flight of the defendant the State can put in its evidence on this point, through the police officers, on rebuttal. It now appears, however, sufficiently clear that this defendant was absent from his home between Nov. 4 and Nov. 27. Unless this absence is denied there does not seem to be any reason for the testimony of the police officers, since testimony on his absence has already been introduced.

Now as to the pistol experts. To be very frank with you, I am at a loss to see that you can get very far even if you prove that the bullet found in the deceased was discharged from a revolver which was found in the middle of Seventh Avenue. There is no doubt that the deceased was shot by a bullet from some gun.

It all seemed neatly choreographed. Both judge and prosecutor were striving mightily to convey to the public that they were really, really, really trying their best to serve justice. Now, the next morning, it was Assistant D.A. Brothers' turn. As George McManus leaned forward to listen, Brothers threw in the towel:

If the court please, the adjournment was taken until this morning to allow us to determine the advisability of calling certain experts as to the identity of the bullet as compared with the weapon found in the street. We have concluded not to call the witness.

We think your Honor's opinion, which coincides with ours is sound. It would not throw any light at this time upon the identity of the assassin, so the people rest.

The great ballet continued. James Murray sprang to his feet, striding toward Nott to announce: "Your Honor, please. I move that your Honor direct a verdict of acquittal on the ground that the People failed to make a case." Nott looked to Brothers, who drew himself up to say:

In a case of this character, if the court please, depending solely upon circumstantial evidence it is necessary for the People to prove such a chain of circumstances that are not only consistent with guilt but exclude all reasonable hypothesis of innocence. I am frank to say that we have not covered the second point.

When we started this prosecution it was based upon evidence which has not been forthcoming. From the beginning of this trial until we rested the People's case, with very few exceptions, witnesses were hostile. It was apparent that they did not tell the truth. Many of them refrained and refused to state the evidence which they had sworn to before the grand jury, which has left us where we are now.

I do not say this in criticism, but in justification of the conduct of the case from the inception. We have done our best. We fought against odds which we could not overcome.

Nott, alleging sympathy for the prosecution's plight, nonetheless instructed the jury to acquit. They did as told. "Not guilty," announced jury foreman Herman T. Sherman. A murmur ran through the courtroom, an odd, loud rumble, indistinct yet clearly approving of the verdict. No one there seemed to care about justice for Arnold Rothstein-or perhaps they'd long ago concluded that Arnold had received justice. After Nott gaveled the farce to its end, McManus blew a kiss to his wife, then turned to his four brothers. "Buddy," said older brother Stephen. "I wouldn't go through with this again for a million dollars. You are the idol of my heart and the idol of your mother's heart. We all know you wouldn't hurt a hair on the head of any one or shoot anything."

"That's right Steve," George replied. "I never hurt anyone. Now go and tell mama."

George fought through the crowd in the corridor, pausing to shake hands with Red Martin Bowe. Outside police (and Bowe) escorted Mr. and Mrs. McManus to a limousine, which took them to Hump's mother up on University Avenue in the Bronx. Reporters followed the car, and when McManus emerged, he handed them a note scrawled on a sheet of yellow paper:

I was innocent of shooting Arnold Rothstein and am naturally happy that it all turned out as it did. Details I cannot give, because I have no personal knowledge of the occurrence. This is all I have to say, outside of wishing everybody a merry Christmas.

How fixed was the case? How orchestrated? How involved was judge Nott? Consider this: On November 22, a Cecelia Kolsky, on trial in an unrelated case, appeared before Nott, who informed her to return on December 6, when the schedule would be clear.Nott dismissed charges against George McManus on December 5.