CHAPTER FOUR

In the first decade of the twentieth century, immigrant traffic between Europe and the United States reached its peak, with 1,285,349 immigrants arriving in 1907 alone, a number that stunned Americans at the time and has never been equaled since. A typical day in those high-volume years could see over three thousand immigrants pass through Ellis Island, most ferried to the mainland within two to three hours. Roughly ten percent, however, were detained as captive guests of the immigration authorities. Among them were eight members of the Rogarshevsky family, two adults and six children. The Rogarshevskys immigrated to the United States from Telsh, Lithuania, a town famous in the nineteenth century as a center of Jewish learning. Abraham and Fannie Rogarshevsky, their five children, along with an orphaned infant niece, sailed from Hamburg, landing at Ellis Island on July 19, 1901. Here, they were briefly detained. The reason given in the official documents was very simply “no money.” The problem was most likely resolved by a relative who came to Ellis Island to vouch for the family, promising to support the Rogarshevskys until they found steady employment.

The Rogarshevskys were held for only a couple of days, but thousands of new arrivals found themselves stuck on Ellis Island for weeks and even months. The detainees fell into three basic groups. Women traveling alone were held on Ellis Island until a male relative came to fetch them, most often a husband or a brother. Another group contained the family members of immigrants held in the Ellis Island hospital. The final and most amorphous group was made up of immigrants who were “not clearly and beyond a doubt entitled to land.” Deportees were also held on Ellis Island pending their return to whatever country they had come from. The vast majority of deportees were rejected as “paupers.”

Detainees were housed in dormitories large enough to accommodate three thousand people. As the newspapers pointed out, that was more than the Waldorf-Astoria and Astor hotels combined. Unlike the Waldorf, however, the immigrant “hotel” on Ellis Island was a strictly no-frills operation. Guests slept on three-tiered bunks with wire mattresses, the bunks enclosed in pens that resembled oversized birdcages. Each morning, the pens were unlocked and disinfected to prevent the spread of typhus, cholera, and lice.

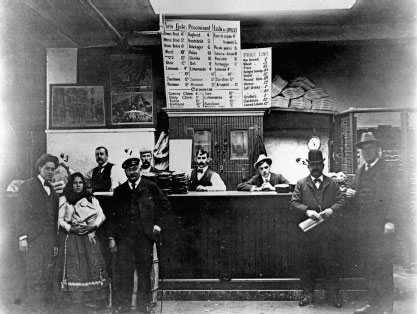

Along with shelter, Ellis Island provided new arrivals with nourishment: three meals a day served in a vast hall—the “world’s largest restaurant,” as one visitor described it. Diners sat at long bench-lined tables draped in sheets of white paper. In the interest of conserving space, the aisles between the tables were just wide enough for a grown man to squeeze through sideways. Even so, the immigrants ate in shifts, a thousand at a time, the first meal of the day served at half past five in the morning. Waiters in white jackets brought the immigrants their food. For many diners, it was the first time they had ever eaten food prepared and served by strangers.

Visitors to the mess hall were shocked by the immigrants’ disregard for table etiquette: They dove into their food like birds of prey and tossed the scraps—the bones and potato peels—onto the floor. When the dining room was expanded in 1908, easy clean-up was factored into the new design. The entire space was covered in white tile and enamel paint, with every sharp angle or edge softened into a curve to prevent dirt from settling into the corners and crevices. The dining-room floor was sloped toward half a dozen drains, so the room could be easily hosed. “It is doubtful,” one visitor concluded, “if the guests of any hotel in the country have their meals served under more satisfactory conditions of cleanliness, healthfulness, and good cheer.”1 As to the quality of the food, opinions were decidedly mixed.

The immigrants’ dining room at Ellis Island, date unknown.

National Archives

Like the baggage-handlers and money-changers, the Ellis Island food purveyors were private contractors granted the privilege of doing business on government property, hence their generic title: “privilege holders.” Of all the island’s concessions, feeding the immigrants was the most lucrative, and local caterers competed for the job in public auctions. The results were announced in the local papers, like the final score in a sporting event. Along with running the dining room, the food concessionaire operated a lunch stand, where immigrants paid cash for bread, sausage, tins of sardines, fruit, and other portable items. In the dining room, the immigrant ate for free, the food paid for by the steamship companies that brought them to America. In 1902, that came to 35 cents a day for breakfast, lunch, and dinner, a small sum that added up quickly. During the high-volume years, feeding the immigrants detained on Ellis Island cost the steamship companies half a million dollars annually, but the money came out of the terrific profits they made on their steerage passengers, the golden goose of the shipping industry.

The immigrants’ first lesson in American food ways, however, took place before they had even landed. Once their ship had docked, the immigrants were loaded onto barges that ferried them to Ellis Island. It was here that each passenger was handed a cup of cider and a small round pie, the quintessential fast food of turn-of-the-century America. The two foods that most impressed the new immigrants were bananas (many tried to gnaw through the skin) and sandwiches. As they waited their turn in the Ellis Island registry line, sometimes a thousand people long, waiters snaked through the crowd, distributing coffee and ham or corned-beef sandwiches. The immigrants munched appreciatively, marveling over the sweetness of American white bread.

The regimen in the Ellis Island dining room was meager and repetitive, a step up from prison fare. For breakfast, there was bread and bowls of coffee with milk and sugar. At lunch, the immigrants were given soup, boiled beef, and potatoes. For supper, more bread, this time with the addition of stewed prunes. Unscrupulous caterers and crooked officials conspired to winnow the big-ticket items (the meat and the dairy) from the immigrants’ diet until all that was left was bread, coffee, and prunes. As a result, thousands of immigrants sustained themselves on an innovation of the Ellis Island kitchen: the prune sandwich.

In 1903, President Roosevelt launched an investigation into corruption on Ellis Island, which ended with a thorough overhaul of the reigning administration. One beneficiary of the regime change was the immigrant dining room. Menus tell the story best. The one below is from a later period, but captures the reformers’ culinary mandate:

SUNDAY, JULY 1, 1917 BILL OF FARE FOR THE IMMIGRANT DINING ROOM

BREAKFAST

Rice with Milk and sugar

served in soup plates

Stewed Prunes

Bread and butter

Coffee (tea on request)

Milk and crackers for children

DINNER

Beef Broth with Barley

Roast Beef

Lima Beans-Potatoes

Bread and Butter

Milk and crackers for children

SUPPER

Hamburger Steak, Onion Sauce

Bread and butter

Tea (Coffee or Milk)

Milk and crackers for children2

The immigrants also dined on pork and beans, beef hash, corned beef with cabbage and potatoes, Yankee pot roast, and boiled mutton with brown gravy. These were the sturdy foods of the American working person served in accordance with the nutritional wisdom of the day. Cooked cereals, cheap but nourishing, were routine at breakfast, while the midday meal, the most substantial of the day, was built around protein and starch. Milk, the all-American wonder food, was available at every meal for immigrant children, and was freely dispensed between meals as well. Vegetables were more or less limited to peas, beans, and cabbage.

Given the very limited diets the newcomers were accustomed to, the great quantities of food that materialized each day in the Ellis Island dining room was cause for euphoria. The fact that it was free of charge was literally beyond belief. To reassure the immigrants, signs were posted in the dining hall in English, German, Italian, French, and Yiddish: “No charge for food here.” Milk, bread and butter, coffee with sugar, all of it free and in endless supply. And the meat! A single day’s ration on Ellis Island was more than many immigrants consumed in a month. The bounty of Ellis Island hinted at the edible riches that waited on the mainland. At the same time, the island also fed tens of thousands of waiting deportees, people who would never reach the mainland but were granted a fleeting taste of American abundance. Deportees spent their days locked up in holding pens, but the food they received on the island was wholesome and plentiful. According to one island official, the thick slabs of buttered bread and hot stews were so much better than any food the deportees had ever known that they wept at the thought of leaving Ellis Island, even if staying meant a lifetime of confinement.

Each year, on the last Thursday of November, detainees celebrated American abundance at a Thanksgiving banquet that featured roast turkey, cranberry sauce, and sweet potatoes. Whether or not they grasped the meaning behind the meal, the immigrants were clearly swept up in the festive spirit of the day. In place of flowers, the women bedecked themselves with sprigs of celery plucked from the tables, while the children feasted on candy and oranges. After the dinner was served, the men puffed on cigars, a habit acquired just for the occasion. The meal itself lasted for several hours, the waiters instructed to keep filling the plates until every diner was fully sated. When it was over, the immigrants were serenaded by a hundred members of a German singing society. Their final number was the Star-Spangled Banner, a song the audience had never heard before, sung in a language it couldn’t comprehend. Nonetheless, the immigrants caught on quickly and rose to their feet, their heads bowed.

As to the food, it was also unfamiliar. The great majority of the guests had never seen a cranberry or an orange-fleshed potato, but the dish that perplexed them most was mince pie. A reporter from the New York Sun who visited Ellis Island in 1905 witnessed the immigrants’ first tentative bite of this holiday classic:

Mince pie was a novelty as to form if not to contents to everyone who sat down to his first Thanksgiving dinner. Half a pie was served to each, but it was some minutes before the diners could make up their minds as to what they were getting and as to whether they would risk it.

But then:

When once they buried their teeth in the spicy filling, it was easy to see that they would be willing converts to the great American practice of pie-eating.3

The implications were clear. In that moment of conversion, their taste buds adjusting to the fruity richness, a future American was born.

Images of Ellis Island as a floating cornucopia contrasted sharply with the “island of tears” portrayed in the immigrant press, among the institution’s most vocal critics. Foreign-language newspapers condemned Ellis Island for its overcrowding, its callous handling of new arrivals, and its overzealous implementation of immigrant law. When the complaints grew loud enough, government commissions were convened to investigate the charges. (Roosevelt’s 1903 investigation was in response to a series of condemnatory articles that ran in the German-language newspaper, the New York Staats-Zeitung.) While some claims were exaggerated, many charges leveled by foreign-born reporters were essentially true. Immigrants were denied entrance to the United States on petty technicalities; they were treated with gruff indifference by island employees and wedged into bug-infested dormitories. The deeper truth, however, is that the brutal efficiency of the Ellis Island machine somehow coexisted with genuine attempts at humane handling of the alien masses.

Detention on Ellis Island was a dreary, physically demanding, and anxiety-ridden experience. During that first busy decade, the immigrants’ dining room was among the island’s only bright spots. (Another was the roof garden complete with boxes of flowering geraniums, awnings for shade, benches for resting, and a children’s playground.) Over time, however, the men who ran Ellis Island looked to the immigrant depot as the first all-important point of contact between the United States government and its future citizens, developing a near-mystical belief in the power of that first encounter. Frederick Wallis, immigration commissioner from 1920 to 1921, summed up the new thinking this way: “You can make an immigrant an anarchist overnight at Ellis Island, but with the right kind of treatment you can also start him on the way to glorious citizenship. It is first impressions that matter most.”4 In his efforts to ensure the best possible impression, the commissioner introduced a series of reforms, imposing higher standards of cleanliness and courtesy. He established a baby nursery for young mothers, a playroom for children, and a recreation hall for adults. On weeknights, the immigrants attended lectures and motion-picture showings, while Sunday afternoons were set aside for live concerts. In the dining room, the new spirit of hospitality meant a more inclusive kitchen pantry, an attempt to satisfy the immigrants’ diverse culinary needs. One of the most important additions to the Ellis Island regimen was pasta—or “macaroni,” as it was listed on the menu. As the officials in charge of Ellis Island grew more attuned to the immigrants’ native food customs, the job of feeding them grew more complex. But while each group traveled with its own set of culinary biases and food taboos, no group arrived with more stringent and elaborate dietary restrictions than the Jews.

According to government records, 1,028,588 Jews immigrated to the United States between 1900 and 1910. Of that number, the great majority came from the “Pale of Jewish settlement,” a geographic designation created by Catherine the Great in 1791. Catherine established the Pale in an effort to corral and isolate the Jews living within the newly expanded Russian Empire. On a map, the territory corresponds to modern-day Ukraine, Poland, Latvia, Lithuania, Moldova, and Belarus. Russian Jews were well acquainted with anti-Semitism, but the Jewish mass migration that began in the 1880s was sparked by a wave of pogroms that heightened the Jews’ perennial status as outsiders. They began in 1881 in what is now Ukraine, as rioting mobs destroyed millions of rubles’ worth of Jewish property, killing dozens of Jews in the process. Small-scale pogroms continued for the next twenty years, erupting in full force in the city of Kishinev on Easter Day, 1903, when fifty Jews were killed during several days of uncontrolled violence. America promised Jews a safe harbor and political and religious freedom, along with unbounded economic opportunity.

Russian and Eastern European Jews lived primarily in small market towns known as shtetlach. Once a week, Gentile farmers from the surrounding countryside would converge on the shtetl to sell their goods and buy supplies from the Jewish shopkeepers, though shtetl Jews worked in many other occupations as well. The distinct folk culture that developed in the shtetlach found expression in language, music, and religion. Unlike their German brothers and sisters, shtetl Jews practiced an unambiguously traditional version of Judaism. Where men expressed their piety through study and prayer, women spoke through the language of food. The sacred responsibility of the shtetl homemaker was to keep a kosher home, celebrating the holidays with all the required ritual dishes. On the Sabbath, and other holy days, she distributed food to the poor. Landing on Ellis Island, these same Jews found a profusion of food, but, with a few exceptions, none of it was kosher.

Actually, the Jews’ culinary problems started at sea. Though the steamship companies were legally obliged to feed their passengers, only a fraction served kosher meals. Some fulfilled the requirement with a single food: herring. Others went through the trouble of installing kosher kitchens but hired cooks who were kashruth-illiterate, unfamiliar with the full sweep of Jewish dietary law. Jewish travelers who knew what to expect traveled with their own survival rations. One very common food was thick slices of zwieback-like bread that had been dried in the oven to keep it from spoiling. Travelers also preserved their bread by dipping it in vinegar and sugar then baking it. For protein, they packed dried fish and salami. The chief problem with home-packed food was that it often ran out before the ship reached America, leaving the immigrant with nothing but water and perhaps some tea for the last leg of the journey. Between the rampant seasickness and the germ-infested quarters, no one in steerage—Jew or Gentile—fared particularly well. The Jews, however, faced the added challenge of finding kosher nourishment, an often impossible task, and many arrived at Ellis Island stooped with exhaustion, colorless, and malnourished. Unfortunately for them, the relief of standing on solid ground was quickly followed by another realization: there was still nothing to eat.

The one place freshly landed Jews could find nourishment was at the Ellis Island lunch stand, which carried tinned sardines and kosher sausages. But the stand was only accessible to Jews who had already passed inspection. For Jews detained on the island, the food situation was grim. There was nothing kosher about the immigrants’ dining room, which left devout Jews with a choice: they could either go hungry and possibly starve, or break the food commandments and eat. (The Rogarshevsky family faced this precise dilemma in 1901, though only briefly.) The one time of year Jews were assured of a good kosher meal was at Passover, the springtime feast commemorating the Hebrew exodus. Under the headline “Passover at Ellis Island,” in 1904, the New York Times ran this short but evocative story on the immigrants’ seder:

The food counter at Ellis Island, 1901.

“Food counter in railroad ticket department at Ellis Island,” Terence Vincent Powderly Photographic Prints, The American Catholic History Research Center and University Archives, The Catholic University of America, Washington, D.C.

The Feast of the Passover was celebrated in due form last night at Ellis Island by 300 Jewish immigrants, detained there awaiting inspection. Commissioner Williams gave them permission to celebrate the rites of their church and the great dining hall was turned over to them, and there, dinner was served in keeping with the occasion.

The tables were covered with snowy linen and new dishes right from the storeroom. In the kitchen, the utensils were all new, and the dinner was cooked under the supervision of the immigrants themselves. The dinner was rather more sumptuous than is usually served to incomers—chicken soup, roast goose and apple sauce, mashed potatoes, ground horseradish, matzoth, black tea, and oranges.5

A gastronomic retelling of the Jews’ escape from slavery, the Passover meal held special significance for the immigrants. The parallels were perfectly clear: Russia was their Egypt, the czars were their pharaohs, while America was their modern-day Canaan. But Passover came just once a year.

Relief for the kosher food drought on Ellis Island arrived in 1911, when the Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society finally convinced the authorities to give the depot its own kosher kitchen. HIAS, as it was known, was just one of the many immigrant aid societies with offices on Ellis Island, each one serving the needs of a particular ethnic or national group. Founded on the Lower East Side in 1902, HIAS was formed with a single mandate: to provide any Jew unlucky enough to die on Ellis Island with a proper Jewish burial. From that narrow focus, the mission quickly broadened to helping new arrivals gain a firm foothold in their adopted country. HIAS representatives wearing blue caps with the HIAS acronym embroidered in Yiddish met the incoming ferries and distributed pamphlets (also in Yiddish) on the inspection process. They helped steer immigrants through the island’s bureaucratic maze and advocated for immigrants condemned to return to “the country from whence they came.”

From their vantage point on Ellis Island, it was plain to the HIAS workers that the kosher-food shortage diminished the immigrant’s chance of passing inspection. The Ellis Island doctors sorted all new arrivals into classes, admitting most but barring anyone with tuberculosis, epilepsy, or any other “loathsome and dangerous disease.” In their decrepit post-voyage state, a high percentage of Jews fell into the catchall category “LOPD,” bureaucratic shorthand for “lack of physical development.” It was a vague diagnosis, and not especially loathsome, but serious enough to block the immigrant from entering the country. The reason was purely economic. According to the Ellis Island calculus, physical weakness diminished the individual’s earning power, a most serious consideration. Along with “pauper,” the single largest class of unwanted foreigners, the languishing Jews were officially rejected with another catchall label, LPC, or “likely to become a public charge,” when all they really needed was a few square meals and a good night’s rest.

In 1911, a New Yorker named Harry Fishel took this argument to Washington and presented it to President Taft. An immigrant himself, Fishel was a Donald Trump–like figure who made his fortune in the New York real estate market, purchasing and developing large tracts of land. Many of his holdings were on the Lower East Side, including one entire block of tenements on Jefferson Street. Fishel was also an Orthodox Jew who had channeled his wealth into yeshivas, hospitals, and assorted charities, including HIAS, where he served as treasurer for over half a century.

Harry Fishel’s crusade to feed the immigrants was doubly motivated. An act of compassion on behalf of the helpless foreigner, it was also an act of self-preservation. The way Fishel saw things, the kosher-food predicament on Ellis Island served as a roadblock to the kind of Jews America needed most, the rabbis and scholars who were so essential to the future survival of Orthodox Judaism in secular America. Here was a cause the mogul was ready to fight for. Face-to-face with the president, Fishel pleaded his case with the urgency of a condemned man. He returned to New York the following day with a firm pledge that the United States government would do what it could to fill the kosher gap.

The food served in the kosher dining room was instantly recognizable to the immigrant palate. There were kippered herring, noodle and potato kugels, barley soup, and dill pickles. American specialties also made regular appearances. The following menus from 1914 are the earliest on record:

MONDAY

BREAKFAST:

Boiled eggs (2)

Bread and butter

Coffee

DINNER:

Potato soup

Hungarian goulash

Vegetables

Bread

SUPPER:

Pickled herring

Fresh fruit

Bread and butter

Tea

TUESDAY

BREAKFAST:

Fresh fruit

American cheese

Bread and butter

Coffee

DINNER:

Vegetable soup

Pot roast

Potatoes

Bread

SUPPER:

Bologna

Dill pickles or sauerkraut

Stewed fruit

Bread and tea

WEDNESDAY

BREAKFAST:

Fruit

American sardines

Bread and butter

Coffee

DINNER:

Barley soup

Roast meat

Vegetables

Bread

SUPPER:

Beans (baked by Mrs. Paley)

Cakes

Bread and tea6

The size of the crowd in the dining room rose and fell depending on that day’s shipping schedule. The room might be empty for breakfast, but if a ship arrived that afternoon filled with Russians or Hungarians or Poles, the kosher kitchen went into high alert, capable of feeding six hundred mouths at a single sitting. One interesting footnote to the Ellis Island kitchen’s history is the leading role played by women. During World War I, a woman known to us only as Mrs. Paley (first initial “S”) was in charge, but in later years the job of head cook fell to another woman, whom we know much more about.

When Sadie Schultz came to work on Ellis Island in 1929, she was forty-six years old with a long culinary résumé. Born in Canada in 1882, Sadie Citron Schultz was the daughter of Polish immigrants who had returned to Europe when Sadie was still a young girl and then re-emigrated to the United States, settling on the Lower East Side. According to family legend, Sadie’s mother earned the family’s passage working as a cook for one of the steamship companies, which helps explain the zigs and zags in their route to America. The young Sadie Schultz entered the New York food economy at twelve years old with a waitressing job in an East Side restaurant. She worked steadily from that point on, with only two interruptions. The first was in 1906, the second in 1910, the years her children were born. As soon as the babies were old enough, she put them into the free nursery at the Educational Alliance on East Broadway and returned to the restaurant. At some point in her career, she traded in waitressing for a job behind the stove, and this is where she remained for the rest of her professional life.

Under Mrs. Schultz’s command, the kosher dining room functioned like a home kitchen writ large. Despite the institutional scale of her work, Mrs. Schultz worked without the benefit of written recipes. Recipes would, in fact, have been useless to her, as she could neither read nor write. The dishes she prepared for her immigrant clients were the same ones she made for her own family, the standard offerings of the Jewish home cook. Even more, Mrs. Schultz learned the regional food preferences of each national group and tailored her cooking to suit their tastes, the same way mothers adapt their cooking for a finicky child. So, for example, if she learned that Ellis Island was expecting a boatload of Hungarians, she prepared her stuffed cabbage with raisins and sugar, to satisfy the Hungarian sweet tooth. For Lithuanians, she omitted the sugar and added vinegar.

The following stuffed-cabbage recipe comes to us from Frieda Schwartz, born on the Lower East Side in 1918. Her special touch is the addition of grated apple to the filling.

STUFFED CABBAGE

1 lb beef

1 egg

3 cups canned tomatoes

½ tsp pepper

Beef bones

1 peeled and grated apple

3 tbsp rice

3 tbsp cold water

4 tbsp grated onion

3 tsp salt

1 cabbage

Pour boiling water over cabbage. Let stand 15 minutes. Separate the leaves. Remove the thick stem from the outside of each leaf. Prepare the sauce in a heavy saucepan by combining tomatoes, salt, pepper, and bones. Cook 30 minutes, covered. Mix beef, rice, onion, egg, apple, and water. Place a heaping tablespoon of the mixture in a cabbage leaf. Roll leaf around mixture and add to sauce. Season with lemon juice and brown sugar. Cook 2 hours.7

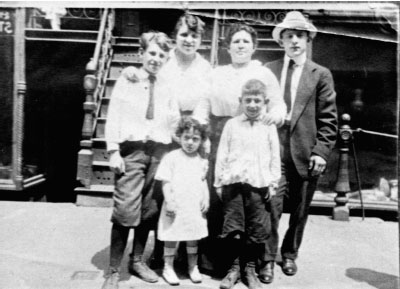

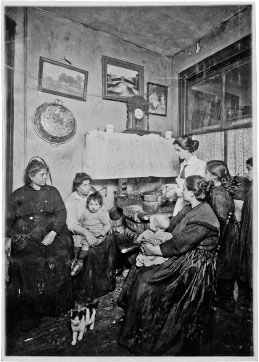

Fannie Rogarshevsky and her son Philip, circa 1917.

Courtesy of the Tenement Museum

Fannie Rogarshevsky gave birth to two more children in America, bringing the total to six: two girls and four boys. For a time, the Rogarshevskys lived at 132 Orchard Street, moving down the block to number 97 sometime around 1908. The building was also home to Fannie’s parents, Annie and Joseph Beyer, who had adopted their orphaned granddaughter. According to the 1910 census, the sixty-four-year-old Mr. Beyer earned his living as a street peddler. During the 1920s, another set of relatives, the Bergmans, lived directly across the courtyard from the Rogarshevskys, the two buildings connected by a clothesline. Mrs. Rogar shevsky occasionally used the clothesline as a delivery system, sending the Bergmans pots of cholent, a Sabbath stew.

At the time of the 1910 census, all six of the Rogarshevsky children were still living at home. Ida, age eighteen, was employed as a “joiner” in a garment factory; Bessie, age sixteen, was a sewing-machine operator; and Morris, age fifteen, worked as a shipping clerk. Sam and Henry, ages twelve and seven, were in school, and three-year-old Philip was at home with his mother. The four Rogarshevsky boys slept in the parlor room on a jury-rigged bed, their heads resting on the sofa, their feet supported by four kitchen chairs. The two girls shared a folding cot, while their parents slept in the “dark room,” on the other side of the kitchen. The Rogarshevsky boys spent their free time haunting the front stoop and getting into street fights. (One of them, Sam, trained in a local boxing gym with the hopes of going professional, a career many East Side boys dreamed about and some achieved.)

On the 1901 ship’s manifest, Abraham Rogarshevsky described himself as a “merchant.” In New York, however, he worked as a presser in a garment factory, a job held exclusively by men. Mr. Rogarshevsky was paid “by the piece,” his salary dependent on the number of garments completed per week, a common point of contention between factory workers and managers. By 1917, Mr. Rogarshevsky had been diagnosed with tuberculosis, which was then known as the “tailor’s disease,” and died the following year. After her husband’s death, Fannie supported her family by taking in boarders, a common recourse of East Side widows. At the same time, she became the building’s janitor, a job that offered no wage but allowed her to live there rent-free. Between her two jobs, the income of her older children, and the kindness of her neighbors, the single mother of six cobbled together a decent existence. Among her allies were the East Side peddlers, so indispensable to neighborhood homemakers, who provided a wide array of edible goods at the lowest prices in the city.

For Eastern European Jews, the city’s pushcart markets were a reminder of home. The shtetlach that the immigrants had left behind had one key feature in common: an outdoor food market where, once a week, Jewish homemakers shopped for their supplies. Some of what they needed could be found in stores, but they relied on the market for their produce, their poultry, fish, milk, cheese, and butter, as well as household goods like candles, pots, and pans. When they arrived in New York, they found themselves perfectly at home in the tumult of the East Side pushcart markets that had been created by their immigrant predecessors.

To uptown visitors, the East Side pushcart markets were garbagestrewn streets aswirl with foreigners, women in tattered wigs, baskets over one arm, haggling at top volume over third-rate merchandise. In other words, retail mayhem. The more Bohemian of the uptown visitors swooned over the romance of the pushcarts. They came to the markets as sightseers (never as customers) to drink in the Old World atmosphere and observe the local customs. Whenever the city threatened to close down the markets, which it did at regular intervals, they mourned the impending loss, mostly on aesthetic grounds. The pushcart markets on Hester, Orchard, and Essex streets were among the most picturesque spots in New York, and the city would be a much grayer place without them. The point that seemed to elude them was the usefulness of the markets to the people they served. For the tenement housewife, the pushcarts were America’s antidote to hunger. They provided her with a wide assortment of familiar foods at the lowest possible prices, and allowed her to buy them in the quantities she desired. Where else in New York could she buy half a parsnip or a handful of barley, not a single ounce more than she needed? The minuscule purchases possible at the pushcarts surprised uptown New Yorkers, who wondered why anyone would buy a single egg, but to the tenement housewife, it was eminently practical. She had no pantry to store her provisions and no ice box to keep foods from spoiling. More compelling still, small purchases were the only kind she could afford.

Tenement housewives like Fannie Rogarshevsky shuttled between the pushcart and the kitchen at least twice a day. In the mornings, before the children were awake, they bought their breakfast supplies, some hard rolls and maybe a cup of pot cheese. In the afternoon, they returned to the market for their dinner ingredients. To the uptown city-dweller, the idea of shopping meal-by-meal was hopelessly inefficient. The tenement housewife saw things differently, treating the pushcarts as an extension of her own kitchen. For Mrs. Rogarshevsky, who lived directly above the Orchard Street market, this was almost literally the case, and the same was true for thousands of other East Side women.

The pushcart market was a boon to East Siders on both sides of the equation, shopper and peddler alike. A line of work familiar to the Eastern European Jew, peddling was the fallback occupation of new immigrants. It required little capital, no special work skills, and scant knowledge of English. All immigrants needed were a basket and a few dollars to invest. Many started with dry goods—suspenders, collar buttons, sewing pins, and the like—which they peddled door to door. The pushcart, a larger retail venue, demanded more capital and a deeper knowledge of the workings of the city. Pushcart peddlers rented their carts for 10 cents a day from one of the many East Side garages or pushcart stables. They began work each morning around four a.m., wheeling the carts to a wholesale produce market on Catherine Slip along the East River, which catered specifically to the pushcart trade. By five a.m., carts loaded, they were on the street and ready for business. At some point in the afternoon, the peddlers’ wives took over the cart so the men could rest up for the next day’s early start. (Actually, a fair percentage of peddlers were women, and only some were partners with their husbands.) The chief attraction of peddling for the Eastern European Jews was the independent nature of the work. The sweatshop worker had precise hours to keep, quotas to meet, and supervisors to appease. The peddler, by contrast, was his own boss. As one East Sider put it, “the peddler was a man who had seen the sweatshops and thought they were for someone else.” There was dignity in peddling, but, even more to the point, the peddler was free to set his own hours and keep the Sabbath. To observant Jews, this was a crucial advantage over the sweatshops, which followed the Gentile business week and stayed open Monday through Saturday.

Beginning in the 1890s, the pushcart market became a regular destination for New York journalists, who were lured by its literary possibilities. They came in search of good copy and found it in characters like the Polish fishmonger with her barrels of two-penny herrings, or the horseradish peddler, bent over his mechanical grinder, literally reduced to tears by the rising fumes. A more quantitative rendering of the pushcart market was provided by New York mayor George B. McClellan, who presided over City Hall from 1904 to 1909. Pressured by public concern over the quickly growing number of pushcarts, Mayor McClellan appointed a commission to investigate what some New Yorkers referred to as “the pushcart evil.” Their complaints were many. The pushcarts, they said, were a threat to public health. They generated garbage and interfered with proper street-cleaning. They sold contaminated food—moldy bread, worm-ridden cheese, rotten produce—to New York’s most vulnerable citizens. Even more pressing, the pushcarts interfered with the free flow of traffic in a rapidly expanding metropolis, a matter of great concern to city officials.

To establish a common body of facts, Mayor McClellan ordered a systematic “pushcart census,” and on May 11, 1905, a small army of police officers fanned out over the Lower East Side, each one armed with a stack of questionnaires. To some measure, the census confirmed what everybody already knew. The one neighborhood with more pushcarts than any other was unequivocally the Jewish ghetto. Of the four thousand pushcarts counted in Manhattan, two thousand five hundred were on the Lower East Side, with the highest concentration on Hester, Orchard, and Essex streets. The census also brought surprises. The pushcart peddlers earned a better living than anyone suspected, and stayed in their jobs longer than anticipated. Peddling was not just a stepping-stone job, as most people believed, but a destination. Another surprise was the high quality of the goods. Contrary to expectation, more than 90 percent of the fruits, vegetables, eggs, butter, cheese, and bread sold from the pushcarts was declared fresh and wholesome, of better quality than the same items found in a store. The public world of the market offers a rare glimpse into the private realm of the kitchen. Thanks to the mayor’s census, we know precisely what foods were available to the tenement housewife and which she relied on most.

Health workers who studied the immigrants’ eating habits in the early part of the twentieth century bemoaned the shortage of vegetables on the Jewish dinner table. The ghetto market, however, abounded with vegetable peddlers. Of course, there were potatoes, but there were also beets, cabbage, carrots, eggplant, parsnip, parsley, rhubarb, onions, peppers, peas, beans, cucumbers, radishes, and a food listed as “salad greens.” One reason the health workers may have overlooked Jewish vegetable consumption is that so much of it came in the form of soup.

There’s an old Yiddish proverb that goes: “Poor people cook with a lot of water.” The truth of the proverb was borne out on a daily basis in the immigrant soup pot. In the winter months, Jewish cooks like Mrs. Rogarshevsky prepared tangy, magenta-colored borschts; cabbage soup; chicken soup with carrots, celery, and parsnip; potato soup enriched with milk; and, most economical of all, bean soup, a dish found throughout the tenement district regardless of the cook’s religion or country of origin. Lima beans, fava beans, white beans, lentils, chickpeas, and dried peas both yellow and green were cheap, nutritious, and easy to cook. Jewish cooks liked to combine their beans with onion, carrot, celery, and barley, producing soups that were deeply flavored and slightly chewy. They called the soup krupnik, a dish traditionally served to impoverished yeshiva students. In its simplest form, krupnik was indeed a spartan dish, nothing more than lima beans, a handful of barley, and maybe a chunk of potato. Adding a marrow bone was one way to make it more substantial. For meatless krupniks, the cook might add a splash of milk or maybe some dried mushrooms, an ingredient that mimicked the savoriness of meat.

In the mid-1930s, the Daily Forward, the East Side’s leading Yiddish newspaper, began a regular cooking feature edited by Regina Frishwasser. The recipes that appeared in the column were sent in by readers—home cooks with limited time and limited budgets as well. In the 1940s, Frishwasser collected the recipes into Jewish American Cook Book. The purpose of the book, she writes in her preface, “is not to bring glamour to a menu, but rather to bring our foods in the easiest way possible to those who want them.” Here is her recipe for a krupnik that used dried mushrooms, barley, lima beans, and yellow split peas.

KRUPNIK

Bring 2 quarts water to a boil, and add 1 cup yellow split peas, ½ cup minute barley, ½ cup lima beans, and 1 teaspoon salt. Simmer 1 hour and add 1 ounce broken dried mushrooms, 1 minced onion, 1 diced carrot, and 1 diced parsley [root]. Cook until the vegetables are tender. Fry 1 minced onion in 2 tablespoons butter until golden brown, then add to the soup.8

Come summer, Jewish cooks turned to chilled soups, like meatless borscht served with sour cream and boiled egg, just one of the many mouth-puckering foods consumed by the immigrants, a taste preference they had acquired on the other side of the ocean. Back in Europe, the traditional souring agent in borscht was home-fermented beet juice otherwise known as rossel. Once in America, cooks turned to a store-bought product called sour salt (tartaric acid) to give their borscht the required zing. Like lemonade, it was the sourness of borscht that made it so refreshing. Schav was another cold and sour soup that the Jews consumed as a summer tonic. Murky green in color, it was made from boiled and chopped sorrel leaves, a plant loaded with vitamin C. The appearance of sorrel on the East Side pushcarts signaled that spring had come to the ghetto. Tenement housewives prepared their first batch of schav sometime in mid-May, and served it “the old Ghetto way,” with sour cream, bits of chopped egg, cucumber, and scallion, so it was part soup and part salad. Schav was also popular in the East Side cafés, where customers sipped it from a glass like iced tea.

In warm weather, as pushcarts filled with summer vegetables, the Jews became avid salad-eaters, though not the leafy green kind favored by the Italians that we are most familiar with today. Instead, they chopped cucumber, radish, scallion, and pepper into bite-size chunks and sprinkled them with a little salt and pepper. In a more luxurious version, the raw vegetables were crowned with a scoop of cottage cheese or sour cream, a dish once referred to as “farmer’s chop suey.” This classic Jewish creation was reportedly the food that Harry Houdini (a Hungarian-born Jew) requested on his deathbed.

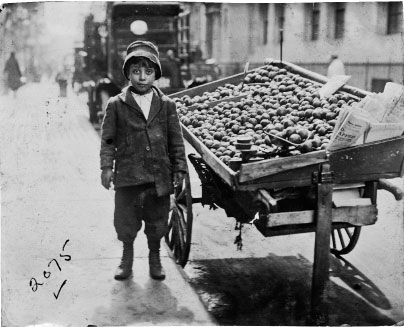

When the first pushcart survey was taken in 1905, fruit peddlers held sway over the market, occupying more curb space than vendors of any other food. On the far side of the ocean, Jewish fruit consumption was more or less limited to whatever grew locally, including apples, peaches, cherries, berries, and, above all, plums, which grew on the outskirts of the shtetls and which Jewish cooks made into a thick, dark preserve called pavel, a kind of plum butter. Plums were also dried along with apples and used in cooking. Jewish cooks added prunes to festive dishes like tzimmes (sweet glazed carrots) and cholent, or used it as a filling for hamantaschen, the triangle-shaped Purim cookie. When crushed and left to ferment, plums were the foundation for slivovitz, a kind of Eastern European firewater. At the pushcart market, immigrant Jews discovered an Eden of melons, citrus, stone fruits, and tropical wonderments like pineapple, banana, and even coconut, which the vendor sold, pre-cracked, the white oily shards floating in jars of cloudy water. In fact, many kinds of fruits—melons, pineapple, even oranges—were sold presliced and hawked as street food, a practice that city officials frowned on. (According to the New York sanitary police, the consumption of bad fruit purchased from street peddlers was a leading cause of death among East Side children.) Where other vendors packed up by dinnertime, the fruit vendors remained on the street long after the sun went down, their carts illuminated by flaming torches. Fathers coming home from work would stop by the fruit peddler for penny apples to give to the kids. On summer nights, when tenement-dwellers poured into the streets for a breath of fresh air, strolling East Siders paused at the fruit carts for a cool slice of watermelon. Fruit was the great affordable luxury of the tenement Jews.

Family members often took turns at the pushcart. Children peddled in the afternoon when school let out.

CSS Photography Archives, Courtesy of Community Service Society of New York and the Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Columbia University

In the early 1920s, a Boston dietician named Bertha Wood conducted a multiethnic study of immigrant eating habits, eventually published as a book, Foods of the Foreign-Born in Relation to Health. As the title suggests, the book was written for health-care professionals—visiting nurses, settlement workers, and dispensary doctors—who served the immigrant community. Though well versed in current medical practice, they knew very little about the immigrants’ foodways, a tremendous handicap in treating the immigrant patient. For each group in her study, Wood identified the leading food deficiencies and most harmful tendencies. She was also ready, however, to point out where the immigrant cook was superior to her native-born counterpart.

At less than a hundred pages, Foods of the Foreign-Born is a curious little book. Ms. Wood approaches her immigrant subjects with a degree of culinary open-mindedness unusual for the 1920s, a particularly anxious period in American political history. At the same time, she is firmly moored in the food wisdom of her day, with a deep faith in the value of bland, unadorned cooking like creamed soups and boiled vegetables. Her 1920s perspective helps explain Wood’s two most persistent concerns with the immigrant kitchen: too much seasoning and too little milk. Ms. Wood declared the Jews guilty of both preparing highly seasoned foods (one reason the Jews were so nervous) and depriving their children of sufficient milk, “nature’s most perfect food.”

Red Cross workers distributing milk, “nature’s most perfect food,” to newly landed immigrants.

Library of Congress

Among the foods that Ms. Wood objected to most was a much-loved Jewish staple: the pickle. “Perhaps no other people,” Wood observed, “have so many ‘sours’ as the Jews. In the Jewish sections of our large cities,” she continued,

There are storekeepers whose only goods are pickles. They have cabbages pickled whole, shredded, or chopped and rolled in leaves; peppers pickled; also string beans; cucumbers, sour, half sour, and salted; beets; and many kinds of meat and fish. This excessive use of pickled foods destroys the taste for milder flavors, causes irritation, and renders assimilation more difficult.9

More alarming still was the pickle habit among Jewish school kids, who spent their lunch money on pickles and nothing else, their appetites ruined for more appropriate foods like milk and crackers. The taste of the standard Jewish pickle was so aggressive—briny, garlicky, sour—and so foreign to the native palate that Americans like Ms. Wood wondered how anyone, children especially, could eat them by choice. Instead, they saw pickle-eating as a kind of compulsion. The undernourished child was drawn to pickles the same way an adult was drawn to alcohol. More than a food, the pickle was a kind of drug for tenement children, who were still too young for whiskey.

At the pushcart market, the pickle stand was a rendezvous for shoppers. Here, standing among the barrels, hungry East Siders could buy a single pickle and eat it on the spot, then continue with their errands. Pickles were also sold in bulk, dished from the barrel with a sieve and packed into jars supplied by the shopper. Uptown visitors to the market were shocked by the size of Jewish pickles, some “large enough to kill a baby.” These overgrown sours were cut into thick rounds that sold for a penny a piece and placed between bread to make a pickle sandwich, a typical East Side lunch.

The following recipe is adapted from Jennie Grossinger’s The Art of Jewish Cooking:

DILL PICKLES

30 Kirby cucumbers of roughly the same size

½ cup kosher salt

2 quarts water

2 tablespoons white vinegar

4 cloves garlic

1 dried red pepper

¼ teaspoon mustard seed

2 coin-sized slices fresh horseradish

1 teaspoon mixed pickling spice

20 sprigs of dill

Wash and dry cucumbers and arrange them in a large jar or two smaller jars, alternating a layer of cucumbers with a layer of dill. Combine salt and water and bring to boil. Turn off heat. Add vinegar and spices and pour liquid over cucumbers. They should be immersed. If necessary, add more saltwater. Cover and keep in a cool place for 1 week. If you like green pickles, Mrs. Grossinger recommends you try one after 5 days.10

Though pushcarts formed the backbone of the immigrant food economy, East Siders also patronized neighborhood shops: butchers, groceries, delicatessens, and dairy stores. This last group, a type of business that no longer exists, included Breakstone & Levine, sellers of milk, butter, and cheese, formerly located on Cherry Street, and forerunner to the modern-day Breakstone brand. But inside the tenements, hidden from the casual observer, immigrants trafficked in a shadow food economy in which neighbors took responsibility for feeding each other. Transactions within the tenement were most often cashless. Neighbors exchanged gifts of food as part of an improvised bartering system in which the poor gave to the truly destitute, or, in many cases, to families struck by tragedy: a death, sickness, a lost job. In return for her edible gifts, the tenement homemaker received the same consideration whenever her luck was down—and no one in the tenements was immune from a run of bad luck. Mrs. Rogarshevsky, a widow with six kids, was certainly eligible, and edible charity must have streamed into the apartment during and after her husband’s long illness, when she adjusted to her new role as breadwinner.

The continuous give-and-take that carried food from one apartment to another was a strategy for survival among tenement-dwellers sustained by the tenement itself. In buildings where apartment doors were hardly ever locked or even closed, where stairways were used as vertical playgrounds, rooftops functioned as communal bedrooms, and front stoops were open-air living rooms, the business of daily life was an essentially shared experience. Tenement walls, thin to begin with, were riddled with windows, windows between rooms, between apartments, and windows that opened onto the hallway. As a result, sounds easily leaked out of one living space and into another. Or, if they were loud enough, ricocheted through the central stairwell. During summer, when East Siders hungered for fresh air, and windows to the outside world were open wide, voices were broadcast through the building via the airshaft. In the brownstones and apartment houses above 14th Street, New Yorkers lived more discreetly, sealed off from the larger world in their own domestic sanctuary. In the tenements, the people who lived above and below you were often blood relatives, but even if they weren’t, you were fully briefed on their domestic status down to the most intimate details, and vice versa.

Fannie Rogarshevsky (back row, second from right) and three of her children posing in front of 97 Orchard, circa 1920. (The two children in the front row are unidentified.)

Courtesy of the Tenement Museum

The communal nature of tenement-living was unavoidable and frequently unbearable. (Tenement-dwellers craved two things that many took for granted: privacy and quiet.) At the same time, it encouraged neighbors to look after each other in ways unheard of in other forms of urban housing. Visitors to the tenements, settlement workers, sociologists, and social reformers, were struck by the generosity of the poorest New Yorkers, recounting their many acts of kindness in memoirs and studies. In fact, their writing became so cluttered with examples of tenement compassion that Lillian Wald, founder of the Henry Street Settlement, was moved to write, “it has become almost trite to speak of the kindness of the poor to the poor,” by way of introducing her own extended list.

The acts of kindness took many and varied forms. Between 1902 and 1904, a sociology student named Elsa Herzfeld carried out a study of family life in the tenements, which outlined some of them:

The readiness to share seems to me to be one of the chief traits in the relation of neighbor to neighbor. The aid given is of a simple kind. It satisfies an immediate need. Above all it is spontaneous…. When a mother has to go out for the day, she “leaves” the children with her neighbor or asks her to go in “and have a look at them.” The neighbor comes in when the children are sick, she offers her blankets, makes some soup, suggests her own physician, or brings cakes and goodies to the sick child. She visits a neighbor patient in the hospital and brings her ice cream and candy or flowers. If a mother dies suddenly, a neighbor takes the children to her own room. If a child is neglected, she takes her “for months and asks no board.” The young girl on the same floor is given a place in the home “to keep her from fallin’ into low company.” If your husband gets “drunk,” a neighbor opens her door to you. If you get separated or dispossessed, “she has always room for one more.”11

As a rule, East Siders avoided taking handouts from the established charities because of the stigma it carried. Even the trip to the charity office, oftentimes located in alien neighborhoods, was a much-dreaded exercise in humiliation. In a coming-of-age memoir set on the Lower East Side, Bella Spewack, who later went on to a successful career as a Broadway playwright, describes her mother, pregnant at the time and with two kids already at home, abandoned by her husband, trying to convince the charity officer that she was worthy of $14 in rent money. “To get help from that place…you must cry and tear your hair and eat the dirt on the floor,” Spewack writes. But seeking help from a neighbor was another story entirely. In the tenements, there was no need to explain or plead your case. Passengers on the same proverbial boat, the people around you grasped your situation with perfect clarity and gave what they could, with no probing questions or edifying lectures.

Sharing food with neighbors was standard practice among immigrants of every nationality, and in some cases, between nationalities. So, for example, an Italian housewife fed minestrone to the Irish kids who lived on the second floor, while Russians brought honey cake to the old Slovak lady across the airshaft. Widespread though it was, food-sharing loomed especially large among Jewish immigrants, who arrived in the tenements with their own long history of culinary charity. Fridays just before sundown, in the towns and cities they had come from, a woman who could afford the extra expense prepared a little more food than her own family needed and distributed it to less well-off neighbors. The sight of women carrying loaves of challah through the streets, or covered pots of stewed fish was a regular Friday-night occurrence. A second option was to invite a poor stranger to join the family Sabbath table, an old widower or beggar, or maybe a peddler who was miles from his own home. Public feasts were held for the poor in honor of weddings and brisses, the circumcision ceremony held on the infant’s eighth day of life. Food-sharing, in short, was a built-in feature of the Jewish kitchen.

Fannie Cohen was an immigrant homemaker from Poland, who arrived in New York in 1912, a married woman with two young kids. Her husband was already here, having immigrated a full eight years earlier, and was working on the East Side as a carpenter. The family lived at 154 Ridge Street on the Lower East Side, in a tenement much like 97 Orchard, where Mrs. Cohen gave birth five more times, though one of the children died at fourteen months from contaminated milk. Mrs. Cohen had received a classic Jewish culinary education. Friday nights, she made gefilte fish (her standard formula combined whitefish, carp, and onion), which she chopped in a large wooden bowl and simmered along with the fish bones, wrapping them first in cheesecloth to prevent the kids from choking on one. She also made roasted carp, the whole fish rubbed with peanut oil, chopped garlic, and paprika, then baked until the skin was varnished-looking and slightly crisp. On Shavuot, the holiday in late spring that celebrates God’s gift of the Ten Commandments, she made yellow pike, the fish sliced crosswise into meaty steaks then simmered with lemon, bay leaves, pepper, and a pinch of sugar. The main culinary attraction on the Purim table was goose and, for dessert, hamantaschen. On Passover she made brisket, fruit compote, and chremsel, dainty pancakes made from matzoh meal that were eaten with jam or dipped in sugar.

Whatever the holiday, it was Mrs. Cohen’s habit to prepare more food than her own family could ever consume. Friday mornings at three a.m., she mixed up a batch of dough for the Sabbath challah, using twenty pounds of flour, forty eggs, and five cups of oil. The only vessel large enough to hold it was a freestanding baby’s bathtub. Once mixed and kneaded, the dough was left to rise in its metal tub, covered by a wool blanket, until mid-morning, when it was sectioned off into loaves and left to rise again. By afternoon, Mrs. Cohen had twenty braided loaves cooling by the window. Some she gave to the neighbors, and some to the local rabbi, who always received the two largest loaves, each one the size of a placemat. Two loaves she kept for the family, but the rest she packed up and delivered to the newly landed immigrants at Battery Park, ferried there directly from Ellis Island. Knowing that some of them were stranded for the night—a tragedy on the Sabbath, when every Jew should be celebrating—she also came with soup, conveyed across town in metal canisters with screw-on tops.

In America, the newly arrived immigrant became the main recipient of the Jew’s edible charity, while the tenement became the new shtetl. On Shavuot, Mrs. Cohen made hundreds of blintzes—some blueberry, some cheese, some potato—and sent them through the building, delivered by one of her kids. For Passover, she sent around tins of flourless sponge cake. But sometimes, there was no holiday at all and Mrs. Cohen still fed the building, handing a plate of stuffed cabbage or a square of kugel to one of the children with the instruction, “Bring up Mrs. Drimmer some food” or “Take this to Mrs. Sipelski,” depending on which of the neighbors was sick or jobless or otherwise in need. These food deliveries always involved a round trip, since the child was later sent back to retrieve the now-empty dish. And sometimes the charity extended beyond the tenement to the larger neighborhood, like on Passover, when Mrs. Cohen invited strays, down-and-out characters whom her husband had rounded up on the way back from the synagogue, to eat from her own Seder table.

Here is Mrs. Cohen’s challah recipe, scaled down to yield two good-size loaves:

CHALLAH

2 ½ lbs or 7 ½ cups bread flour

2 ounces fresh yeast or 4 teaspoons instant yeast

1 ½ cups warm water

½ cup peanut oil or other vegetable oil

4 eggs, room temperature

½ cup sugar

3 tablespoons salt

Dissolve yeast in warm water and let stand until mixture looks foamy, 5 to 10 minutes. Combine with remaining ingredients, stirring to form a dough. Knead dough for 10 minutes, then place in a lightly greased bowl. Cover with a damp cloth and let rise until doubled in volume, 1 to 2 hours. Punch down dough, knead ten times and divide in two. Separate each half into thirds. Roll each section into a rope about 18 inches long. Braid ropes, pinching the ends and turning them under. Place on a lightly greased baking tray and cover with a damp cloth. Let rise until doubled in size. Preheat oven to 375ºF. Before baking, brush challah with one egg yolk mixed with 1 teaspoon water. Bake for 45 minutes to 1 hour, or until brown.12

Though food items of one kind or another dominated the pushcart trade, the market also provided East Siders with a sweeping array of nonedible goods. Pots, pans, dishes, scissors, soap, clothing, hats, and eyeglasses are just a minute sampling. In short, any useful item from mattresses to sewing thimbles was available at the pushcart market. But East Side vendors also trafficked in more fanciful goods, including the decorative objects known in Yiddish as tchotchkes, figurines, wax fruit, and mass-produced wall prints. The subject matter of pushcart artwork was often inspirational, the immigrant drawn to portraits of heroic figures from the worlds of literature and politics. There were postcard-size prints of William Shakespeare, Henrik Ibsen, Leo Tolstoy, Sholem Aleichem (the Yiddish Mark Twain), and President Lincoln, the great hero of the ghetto. Another revered figure was Christopher Columbus and, in later years, Franklin Roosevelt. Fannie Rogarshevsky kept a plaster bust of Columbus on the parlor mantel.

The market also supplied East Siders with intellectual stimulation in the form of books. Browsing the pushcarts for reading material was, to put it mildly, a hit-or-miss venture. The carts carried a grab bag of mostly secondhand volumes, many of them reference books. On the same cart, the shopper might come across a history of railway statutes, a yearbook from the Department of Agriculture, a collection of Hebrew prayer books, and an assortment of dictionaries. More discerning readers skipped the carts and shopped from the profusion of book stands scattered through the neighborhood. The stands were semipermanent structures, urban lean-tos supported by the tenements on one side, with counters and shelves improvised from discarded doors, window shutters, and stray planks of wood. Unlike the pushcarts, the book stands dealt mostly in new merchandise, books that were published by immigrants for immigrants, often produced in small local print shops.

Sometime in 1901, the same year the Rogarshevskys landed in New York, a skinny paperbound volume made its first appearance on the East Side book stands. The Text Book for Cooking and Baking by Hinde Amchanitzki was America’s first Yiddish-language cookbook, a photograph of the author, her wig neatly parted, gracing its cover. Very little is known about the author’s own immigration history, though in her foreword she shares details from her culinary past. Amchanitzki’s career as a professional cook started in Europe and continued in America. Her recipes, she writes, are based on forty-five years of experience working in both private homes and restaurants, including an extended stint in a New York establishment that catered to “the finest people.” Amchanitzki’s intended readers were women much like Mrs. Rogarshevsky—seasoned homemakers trained in one culinary tradition, now ready, in their own cautious way, to take on another. Accordingly, the recipe index skips between the Old and New World kitchens, with stuffed spleen, chopped chicken liver, and sponge cake alternating with breakfast pancakes, tomato soup, and banana pie. A third group of dishes, however, falls somewhere between the two kitchens, an amalgam of New World ingredients and Old World techniques. Included in this category is Amchanitzki’s recipe for cranberry strudel:

CRANBERRY STRUDEL

Take a quart of good cranberries, a half pound of sugar, and a bit of water. Cook until thick and put aside to cool. Take a glass of fat, a glass of sugar, 2 eggs, and stir together. Add a glass of water and mix well. Take two glasses of flour, two and a half teaspoons baking powder, mix them together, and stir into batter. Take a sheet and grease it well. Pour in half the batter and spread it evenly over the entire sheet with a spoon. Spread the cranberries evenly over the dough and pour the remaining dough over the cranberries, covering them completely. Sprinkle sugar on top and bake thoroughly. When done, let cool and cut into pieces. This is a very good strudel.13

Early twentieth-century cookbooks brought news from the American kitchen to immigrants with limited access to the food habits of mainstream America. One place where contact was possible was the settlement house. The idea behind the settlement house, a British invention of the 1850s, was to bring together the educated and laboring classes for the benefit of both parties. It was always assumed, however, that the educated person had more to give, the laborer more to gain. America’s first settlement house, the Neighborhood Guild (later known as the University Settlement), opened in 1887 on Eldridge Street on the Lower East Side, followed by Hull House in Chicago two years later. By 1910, the number of settlement houses in the United States had reached four hundred.

The settlement house aspired to elevate the working person to “a higher plane of feeling and citizenship.” Most offered classes in literature, music, theater, and dancing, with kindergartens for the youngest children, clubs and gymnasiums for the older ones, and reading rooms for the adults. Some offered vocational training—more for women than men—providing instruction in millinery, sewing, and nursing. In immigrant-dense neighborhoods, where settlement houses assumed the job of Americanizing the foreign-born, there were also English-language classes, classes in civics, and American history. At the Educational Alliance, for example, immigrants could enroll in a lecture course that covered federal and state history, geography, government, and American customs and manners. Students who completed the course received copies of both the Constitution and Declaration of Independence printed in English and Yiddish.

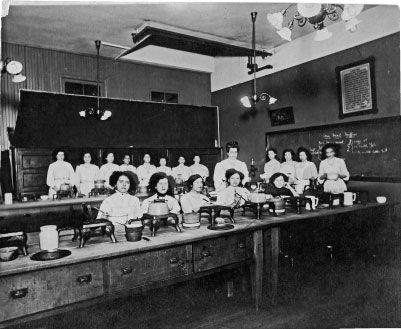

Similar efforts to Americanize the immigrant took place in settlement cooking classes. The class curriculum was shaped by a relatively new approach to housework, known as domestic science, a movement that gained ground with American homemakers in the final decades of the nineteenth century. The women who led the domestic science charge set out to ennoble the homemaker’s daily grind of cooking and cleaning by grounding it in scientific theory and method. They envisioned the home as a kind of domestic laboratory in which women applied their knowledge of chemistry, sanitation, dietetics, physiology, and economics to the everyday work of cooking and cleaning. To help spread their gospel, they established cooking schools in New York, Philadelphia, Boston, and Chicago, and domestic science programs in colleges and universities, including the Pratt Institute in Brooklyn and Columbia University in Manhattan. The Russian-American writer Anzia Yezierska was granted a scholarship to study at the Columbia School of Household Arts, but private cooking programs were generally beyond the means of working-class women. The domestic-science movement reached the working class through charitable institutions like churches, YMCAs, and settlement houses, where classes were offered for free or at prices scaled to the working person’s budget.

The classes focused on the simplest and plainest American foods, beginning with a lesson on how to make toast and brew coffee in a freshly scoured coffee pot. Students learned how to properly boil oatmeal, rice, and potatoes, how to make pea soup, mutton stew, creamed codfish, biscuits, and gingerbread. Settlement houses that catered to Jews adapted the standard lesson plan so it conformed to Jewish dietary law, but only because they had no choice. The people who ran the settlement houses were Reform Jews, many from German families, who had immigrated to the United States in the mid-nineteenth century. In other words, oyster-eaters. In their desire to Americanize the immigrant, they would have preferred to dispense with kosher laws—and some, in fact, tried—but their students wouldn’t allow it. As one settlement worker explained it, “There are some kosher laws that have to be followed, else the teaching would go no further than the classroom and would never show practical results.”

A cooking class for immigrant girls at the Educational Alliance. The girls here are learning how to make corn muffins.

From the Archives of the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research, New York

Of the eight thousand East Siders that passed through the doors of the Educational Alliance each day, the vast majority came to take advantage of the free legal aid, use the public baths, or let their children loose on the rooftop garden. The cooking classes were only a modest success. The reason was simple: the Jewish homemaker already knew how to cook.

In 1916, the New York Board of Health issued a recipe booklet of cheap and nutritious foods intended for the East Side homemaker. Distributed by neighborhood settlement houses, How to Feed the Family was something of a flop among its intended audience. A reporter curious about the East Sider’s reaction found out why. (The interview is transcribed in dialect, a common practice in period newspapers when dealing with working-class subjects.) The Board of Health, one woman explained,

ain’t got no right to say what I should cook and how. Y’understand? Already when I was little I knew how oatmeal it should be cooked. You do it with a double boiler. I ain’t got no use for peoples what teaches me how to cook things that a long time before I done better as what they did.

Her neighbor concurred. “The East Side is the East,” she told the reporter. “I make like my Grossmutter Selig and my mother Gefullte fish and stuffed helzel [poultry neck]. What I care for the Board of Health?”14 But if the Board of Health failed to impress them, immigrant cooks felt the pressure to Americanize from other sources. The most persuasive were the cook’s own children.

No single institution exerted more influence on the culinary lives of immigrant children than the American public school. Here, beginning in 1888, immigrant daughters were taught the fundamentals of American cookery in a then-experimental course based on the principles of domestic science. Declared a success by city educators, the experiment in “manual training” (the classes also gave instruction in sewing, housekeeping, and nursing) became a permanent fixture of the New York public schools. Over the next decades, it expanded and evolved along with the changing profile of the city. For poor students, classes in manual training opened up employment opportunities, but middle-class girls could benefit too. The classes taught them discipline, neatness, and organization, the qualities that would help them manage their own future households.

The program’s original audience was native-born American girls, but the focus shifted as immigrants continued to descend on New York. To reach their foreign-born students, educators hit upon a novel teaching strategy. They replaced the conventional classroom with “model flats,” simulated tenement apartments that mimicked the students’ own tenement homes. In their stage-set kitchens, the girls learned how to maintain the highest sanitary standards, every dish and utensil neatly stowed in its rightful place. They were taught the importance of established mealtimes, the family sitting down together at a properly set table, the food “served” rather than “grabbed.” Finally, they were tutored in the science of cooking with lessons on food chemistry, kitchen mechanics, and human physiology.

Model flats were the brainchild of Mabel Kittredge, a domestic scientist who worked with Lillian Wald at the Henry Street Settlement. The first model flat opened in 1902 in a tenement building in the heart of the Jewish ghetto. Before long, they were scattered through the tenement district, some housed in actual tenements, others in school buildings, including P.S. 7 on Hester Street. Miss Kittredge developed a housekeeping curriculum based on the model flats, which she compiled into a textbook. Today, Practical Homemaking provides a detailed picture of the public school cooking class circa 1914, when the book was published. The recipes in Practical Homemaking, hand-selected for the tenement population, were centered around three core ingredients: milk, cereals, and potatoes. Miss Kittredge saw little use for vegetables, with the exception of beans, the only form of plant life rich in “nutritive value.” She was equally unimpressed by fruit, which, after all, was composed mostly of water. The immigrants’ first cooking lesson was devoted to nature’s most perfect food, milk, from which the girls were taught to make cocoa. Future lessons were devoted to white sauce, boiled cereals like oatmeal and Wheatena, boiled potatoes, and cooked apples. Promoting the foods that Kittredge felt were best suited to the East Sider, the lessons were also designed to wean immigrants away from their less desirable culinary habits. For Jews, that meant forsaking their over-spiced pickles and delicatessen meats, while Italians were asked to cut back on their beloved macaroni and olive oil. Returning to their real-life tenement flats, the girls shared what they had learned, teaching their mothers how to poach eggs, or cook vegetables in boiling water rather than goose schmaltz. Teachers also made home visits to reinforce the lessons and monitor their students’ progress. As one contemporary described it, the girls served as missionaries to their foreign-born parents, a role that the public schools exploited for all it was worth.

Dieticians from local schools and settlement houses paid visits to the tenements. The dietician pictured is teaching immigrant women how to cook hot cereal in a double boiler.

CSS Photography Archives, Courtesy of Community Service Society of New York and the Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Columbia University

A second powerful influence on the food habits of immigrant children was the school lunchroom. Up until the twentieth century, most city kids returned from school each day for a home-cooked meal. That began to change as more and more women found work outside the home, leaving their kids to fend for themselves. With no one to feed them, the kids were given two or three pennies to buy lunch from a local pushcart or delicatessen. In 1908, a group of private citizens, alarmed by this new development, founded the New York School Lunch Committee, a charity that provided three-penny lunches to undernourished children. In place of pickles and candy—the typical pushcart meal—the committee provided hot soups and stews for two cents a serving, and one-penny treats like rice pudding or baked sweet potato. The school lunch committee lasted through World War I, but in 1920, responsibility for feeding the city’s children shifted to the Board of Education. As it happens, the shift coincided with a groundswell of anti-immigrant thinking in the United States, which culminated in the Johnson Reed Act, a far-reaching immigrant quota system passed by Congress in 1924. Calls to Americanize the foreign-born reverberated through government offices and monopolized the editorial pages of the nation’s leading newspapers. With so much attention on the immigrant threat, the Board of Education looked to the school lunchroom to Americanize the immigrant palate. Below is a typical school lunch menu circa 1920:

MONDAY: Cocoa, buttered roll, stewed corn, stewed prunes

TUESDAY: Cream of pea soup, peanut and cottage cheese sandwich, Brown Betty with lemon sauce, fruit tapioca

WEDNESDAY: Vegetable soup, baked beans, vanilla cornstarch with chocolate sauce

THURSDAY: Lima bean and tomato soup, buttered roll, cream tapioca, rice pudding

FRIDAY: Cocoa, salmon sandwiches, sliced fruit, oatmeal cookies15

To extend the lunchroom’s influence, mothers were invited to eat with their kids. During the meal, domestic-science teachers would point out the benefits of the particular dishes served, urging them to prepare similar foods in their own homes. Across America, educators seized on the lunchroom’s educational possibilities, establishing similar programs of their own. A domestic-science teacher named Emma Smedley summed up the new awareness most succinctly. “No branch of the school activities,” she wrote, “offers greater opportunity of fitting in with the Americanization plan than the school lunch.”16 The process was gradual, but in the school lunchroom, kids of diverse backgrounds found a culinary common ground, one tentative bite at a time.

In 1884, a new entry made its debut in Trow’s New York Business Directory, ancestor to the modern-day Yellow Pages. Sandwiched between “Deeds (Acknowledgement of)” and “Dental Equipment” now appeared “Delicatessens.” These specialized groceries had existed in New York for at least thirty years, most of them clustered along First and Second Avenues. Even so, 1884 was a kind of birthday for this immigrant food shop, the year it captured the attention of the Trow’s editors, asserting its place in the city’s food economy.

If the New York Tribune is correct, the city’s first “delicatessen handler,” or deli man, for short, was an immigrant named Paul Gabel, who landed in New York in 1848, the year of revolution in Europe and the start of the great German migration. (Gabel made a good living in America. By 1870, he had moved his store and his family to stately Brooklyn Heights, his fortune now worth $20,000, a substantial amount by the standards of the day.) Shops like Mr. Gabel’s carried a limited stock of sausages, cheeses, and sweets, but as the century progressed, delicatessens added “made dishes” to their lineup of provisions—foods that were cooked and ready to eat, prepared by the owner’s wife in a small kitchen behind the store. Hungry city-dwellers visiting their local delicatessen could choose among the following: meat pies, smoked beef shoulder, smoked tongue, smoked fowls, roast fowls, smoked, pickled, and salted herring, fresh ham, baked beans, potato salad, beet salad, cabbage, parsnip, and celery salads, in addition to all the usual wursts, breads, and cheeses. Though still in the hands of German New Yorkers, the delicatessens’ clientele had now widened to include the city’s growing population of Irish immigrants, along with native-born Americans. By the 1890s, delicatessens were “as common as bricks in a building” the great majority, however, could be found on the Lower East Side. Rich New Yorkers, with their live-in servants and private cooks, had little real need for the delicatessen. But among the tenements, delicatessens assumed the role of a poor person’s catering shop. Bachelors, shopgirls, boarders and lodgers, working mothers, people with little time for the kitchen, some with no kitchens at all, relied on the delicatessens to cook for them. Their ser vices were particularly indispensable during the hot summer months, when firing up the kitchen stove turned the tenement apartment into a sweatbox.