5

Within the first decade of the pastoral invasion, human-induced transformations were clearly occurring in the landscape surrounding Gariwerd. On the plains, soil compaction by stock on the wet, clayey soils around the south and west was evident, as was clearing in forested areas. In the mountains, native animals were hunted and new ones introduced, while in the ranges and on the plains, cycles of burning and regrowth had been altered. The land and natural resource management regimes employed by Djab wurrung and Jardwadjali people had been replaced by intensive European pastoralism. The most direct environmental impacts in the mountains would occur in the later nineteenth century and throughout the twentieth century as people found new ways to make use of Gariwerd’s natural resources in their growing economy. This was accompanied by the growth of major western Victorian townships around Gariwerd from the 1850s onwards, including Ararat and Stawell to the east, Horsham to the north and Hamilton to the south-west. To serve its hinterland, the forests of Gariwerd were harvested, its stones and minerals quarried, and new agricultural industries were developed to make use of its soils and open lands. For farming communities to the north of the mountains, Gariwerd’s water resources were to become integral to their livelihood. Across all of this was an abiding fascination with the botanical resources and aesthetic values of the ranges.

Botany and plant collectors

While resource uses and values have changed over time, one constant point of interest since the middle of the nineteenth century has been Gariwerd’s distinct plant communities, particularly its wildflowers. Thomas Mitchell’s plant collector, John Richardson, had been thorough during the party’s expedition through the area in 1836. When they returned from the peak of Mount William in July, Richardson and Mitchell brought with them ‘various interesting plants, which we had seen nowhere else’. These included the ‘most beautiful downy-leaved’ Grampians common heath (Epacris impressa var. grandiflora), ‘the “most remarkable” notched phebalium (Leionema bilobum), ‘a new Cryptandra remarkable for its downy leaves’ (prickly cryptandra, Cryptandra tomentosa), ‘a beautiful species of Baeckea’ (rosy baeckea, Euryomyrtus ramosissima), ‘a new species of Bossiaea which had the appearance of a Rosemary bush, and differed from all the published kinds’ (Grampians bossiaea, Bossiaea rosmarinifolia), snow myrtle (Calytrix alpestris), ‘several species of Grevillea, a particularly remarkable kind’, including variable prickly grevillea (Grevillea aquifolium) and cat’s claws (G. alpina), and ruddy beard-heath (Leucopogon rufus).1 Through the expedition, Richardson collected around 150 species, which Mitchell sent to John Lindley at the University of London. About 40 of these specimens were new to Western science, including the Grampians thryptomene (Thryptomene calycina) and the Grampians gum (Eucalyptus serraensis), ‘a new species of eucalyptus with short broad viscid leaves, and rough-warted branches’ (Fig 5.1).2

Fig. 5.1. A Grampians gum (Eucalyptus serraensis), photographed on a high, subalpine peak in the ranges during the nineteenth century. Photo: AJ Campbell. Museums Victoria.

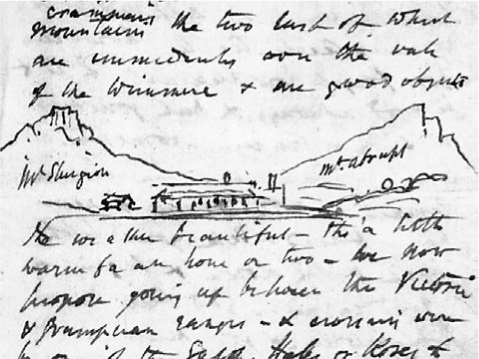

After Mitchell, the next significant plant collecting expedition to Gariwerd was undertaken in November 1853 by the Victorian government botanist Ferdinand von Mueller as part of his broader project to document the flora of the colony comprehensively. Mitchell and Richardson had been in the ranges in winter, while Mueller planned to be there in late spring or summer. Mueller wrote to the governor of the colony, Charles La Trobe, in August 1853, laying out his ‘plan for a new botanical investigation of this colony during the next season … I would propose to start at the end of September or in the beginning of October in a westerly direction, examine all the low country between here and the Glenelg, where already some interesting botanical discoveries have been made by Sir Th. Mitchell, proceed thence to the Grampians for the purpose of adscending the most elevated points of that range … This exploring line … would enable me to accumulate to a certain degree the materials for the Flora of this province.’3 La Trobe himself had visited the ‘Grampians & Victoria ranges’, and stayed at the homestead near Mount Sturgeon in early 1850 (Fig 5.2). Upon La Trobe’s request, Mueller’s expedition commenced in November 1853.

Once he had reached Victoria Range, Mueller wrote to William Hooker, the director of the Royal Botanic Gardens in Kew, on 21 November. He informed Hooker: ‘I have met, to my great delight, with all of Sir Thomas Mitchell’s rarities of the Grampians, beside some which, during Sir Thomas’s visit to this locality (June), were not in flower; so that I hope to be enabled to add amply to your great herbarium. Myosurus australis I found here again — the second locality which I know of this most interesting plant; Marianthes [sic] bignoniaceus and Eriostemon Hillebrandi occur also in the Grampians, as well as a beautiful subalpine Bauera, several Melaleucæ, Mitrasacme, Stylidium, Stenanthera, Styphelia, etc.. Most of them are new to me, and many, I presume, also new to science.’4 Writing from Mount Sturgeon two days later, Mueller told La Trobe that he had been ‘engaged in examining the Grampians and the Victoria ranges. I adscended many of the highest mountains, and found the subalpine vegetation of Mount William particularly interesting. The Victoria-Flora has been enriched during this part of the journey with about 70 species of plants, of which the fourth part appears to be yet undescribed. The Government-herbarium received besides numerous additions in those species, which Sir Thomas Mitchell previously discovered and which seem to be confined to these ranges.’5 Later, in January 1854, Mueller sent Hooker an update, his first since November: ‘I have since that time examined the neighbourhood of Mount Zero (already favourably known by Sir Thomas Mitchell’s researches), and I had here the gratification of adding a considerable number of undescribed or rare plants to my last botanical stores, amongst them a most handsome new genus of Myrtaceae (Scarymyrtus hexamera)’.6 In his report of October 1854, Mueller summarised his impression of the ranges:

Fig. 5.2. Charles La Trobe’s sketch of Mount Sturgeon, Mount Abrupt, and the Mount Sturgeon homestead. Source: La Trobe CJ (1850) Letter – 12 March 1850, Mount Sturgeon. H15618, Box 78/1. La Trobe Australian Manuscripts Collection, Melbourne.

The low land between Melbourne and Mount Sturgeon offered but very few novelties to the collections formed during the previous season, but in the Grampians, the Serra, and the Victoria Ranges, I had an opportunity, by ascending the most prominent heights, to increase considerably the series of plants already discovered in these localities by Sir Thomas Mitchell during his exploration of this country. Many of these plants belong not only exclusively to this Colony, although interspersed with such as inhabit the mountains of New South Wales, Van Diemen’s Land, and South Australia, but are even in some instances restricted to solitary heights, an observation confirmed by similar instances of isolation of certain species occurring at the Table Mount of the Cape of Good Hope, in the mountains of North America, and other parts of the globe. The subalpine summit of Mount William proved in this respect to be exceedingly interesting.7

By 1857, one of Mueller’s assistants, Carl Wilhelmi, had returned to Gariwerd, where, said Mueller, ‘he procured an extensive collection of seeds, particularly valuable as containing many species hitherto nowhere under cultivation. Chiefly of this supply collections have been transmitted for interchange to the Royal Gardens of Kew, to the Melbourne University Garden, to the Botanic Gardens of Hobart Town, Sydney, Brisbane, Adelaide, Paris, Mauritius, Cape Town, Calcutta, Boston, and Hamburg.’8 Wilhelmi would be the first to publish a detailed botanical account of Gariwerd.9 From the late 1850s, another of Mueller’s collectors, John Dallachy, was active in the mountains.10 In his 1858 report on the Botanic Gardens in Melbourne, Mueller said that Dallachy had ‘carried out very successfully this part of the service’ in collecting ‘for interchange, and for enriching our own establishment, seedlings of the remarkable and rare plants of the Grampians’ for the gardens.11 Dallachy’s collections were also destined for Kew, and Mueller told Hooker in 1858 ‘I despatched Mr Dallachi from this establishment two months ago to the Grampians, and now he is just returned with a lot of living plants in an excellent state … plants restricted mostly to that range, and of which I hope to establish a great many for Kew.’12

During his journey through the mountains, Mueller had met with local residents, including the D’Alton family at Glenbower.13 He maintained these relationships, and Mueller would eventually name the narrow-leaf trymalium (Trymalium d’altonii) for St Eloy D’Alton, who had sent him a specimen of this ‘Halls Gap shrub’, and would become an important contributor of specimens to Mueller’s collection.14 As late as 1894 Mueller was sending seeds of ‘economic plants’ to D’Alton for distribution to people in and around the mountains, who had in return sent ‘two specimens, one of an acacia rather rare in this part and the other a Cryptandra I presume, which is only to be met with in one locality in this district It grows 4 and 5 feet high, and the leaves are not the same shape as the others I have collected here and at the Grampians.’15

Daniel Sullivan, a schoolteacher from Moyston, was another of Mueller’s plant collectors and a lifelong enthusiast for the ranges. After a trip to the Australian Alps in 1884, Sullivan told Mueller that his ‘remarks that I would see much that was new to me were correct, but not to the extent I expected. We travelled over a great extent of country the vegetation of which was certainly luxuriant’, but, nevertheless, ‘that I find no mountains in my travels equal to the Grampians for the number and variety of its plants.’16 Sullivan published his Complete Census of the Flora of the Grampians and Pyrenees in 1890, which included 35 plants he said were new to Western science; Mueller had a hand in helping Sullivan to identify the plants he had collected in the ranges.17 Another schoolteacher, Marmaduke Fisher from Dunkeld, collected for Mueller from the late 1850s.18

Mueller maintained a fascination with the ranges decades after his first visit. He would write to the Gardener’s Chronicle in 1886 of the rosy bush-pea (Pultenaea subalpina), describing it as ‘one of the most local of all plants in existence, being absolutely restricted to the summit of Mount William, in the Australian Grampians, at about 5000 feet. This is also the exclusive native locality of Eucalyptus alpina [E. serraensis],’ and suggested it might be grown elsewhere: ‘If plants strong enough for experiment are available, they might be tried in mild places of England as outdoor plants, inasmuch as this Pultenaea has to endure in its native haunts a sub-alpine clime, and is subjected to frosts of more or less severity through several months in the year. In places like Arran in Scotland, the Devonshire coast, and the Channel Islands, it ought to prove perfectly hardy.’19

While Mueller had been primarily interested in botanical specimens, he and his associates collected much else. In 1863, to Joseph Decaisne at Bibliothèque de l’Institut de France, Paris, Mueller sent a case of ‘weapons of the Gipps Land Aborigines’ and ‘fossils from the Grampians’.20 If there is ambiguity about what is meant by fossils in this context, another piece of correspondence is quite clear. In 1868, Mueller had sent his friend Wilhelm Sonder a crate of Australian scientific specimens, which Sonder was to pass on to collections in Berlin, Vienna, Munich and other locations. Sonder informed the director of the Staatliches Museum für Naturkunde in Stuttgart, Ferdinand Krauss, that he would receive some ‘bird skins’, a ‘young crocodile from North Australia as well as a droll animal like a rat’, which would give Krauss ‘some enjoyment, and perhaps also the insects and other vermin in spirit’. At the end of his letter, Sonder told Krauss that Mueller had also sent the body parts of Indigenous Australians for display in the Stuttgart Museum: ‘The skulls of the Aborigines are from the Grampians,’ said Sonder. ‘Perhaps a wild man can be made artificially with the remaining bones.’21 Where these remains were ultimately stored is unclear.

Throughout the later nineteenth century, the Field Naturalists Club of Victoria became active and enthusiastic collectors of specimens both plant and animal. By 1925, in addition to Wilhemi’s early account and Sullivan’s 1890 Complete Census of the Flora of the Grampians and Pyrenees, the senior botanist for the National Herbarium in Melbourne, James Audas, had completed work for his publication One of Nature’s Wonderlands, the Victorian Grampians. One of the chief contributions of this work was to investigate the Mount Difficult region (Plate 5.1), where Audas identified a new species, the broad-leaf trymalium (Spyridium x ramosissimum).22 This early interest from botanists and plant collectors, including Mueller and his many assistants, led to nation-wide recognition of Gariwerd as a unique botanical reserve, a feature that would contribute to its eventual declaration as a national park in the 1980s. In the meantime, other natural resources of the ranges had become just as alluring, albeit for different reasons.

Water

In contrast to the attraction of the fertile pastures to the south of Gariwerd, the plains to the north were much drier. From the early days, Alfred Taddy Thomson held the Fiery Creek pastoral station to the east of Gariwerd. He wrote about how, on journey southwards into the district in February 1841, his party was ‘following the Broken River down to the Goulburn, and the latter to near its junction with the Murray, when we struck into Sir T. Mitchell’s outward track and followed it to the Wimmera’. But, he wrote, ‘our expectations of the country to be found there, formed from his description, were not realised. A series of dry seasons had altered the face of the country, and the fertile region which had presented itself to his delighted view had been converted into an arid waste, destitute of either grass or water.’23 Likewise, John Carfrae traversed the region at length before taking land to the west of Gariwerd. ‘In April 1843 I started with some stock … with the intention of taking up some new country either on the Avoca or Wimmera,’ he said. ‘I passed the north end of the Pyrenees, crossing the Avoca, Avon, and Richardson, all of which were completely dry for from 15 to 20 miles to the north of my course.’ Carfrae recalled how he followed ‘the Wimmera abreast of Mount Zero (the north point of the Grampians), and not liking the then parched and dusty Wimmera Plains, I crossed over to the head of the Glenelg, and in June took up the station now known as Glenisla’. He would later take the Ledcourt run.24 The land to the north of the mountains was, it seems, undesirable to the first squatters, who encountered what seemed to them like a harsh, hostile environment. One colonist recalled how, while resident in the area he ‘made several excursions into the large desert, with the view of discovering new tracts of pastoral country’. He continued to remember how:

We first went in a westerly direction. After proceeding about fifteen miles into it from the side next my run, we came to a steep ridge of sand-hills, about 200 or 300 feet above the adjacent desert. The surface of them was composed of nothing but loose drift-sand, and they were covered with a few stunted bushes. When on the summit they appeared to be a chain of hills running from where we ascended them northerly as far as the eye could reach. To the westward we saw nothing but an unbroken expanse, for the next twelve or fifteen miles, of the same dreary wilderness that lay around us … Interspersed but very distant from each other, on this desert, are oases of a few acres, where the eucalyptus and other trees grow, with a fair sprinkling of grass. As the soil of them is very clayey, it was only on them that we found surface water to drink. The whole eastern extent of it is a loose white sand, covered chiefly with a very prickly grass, which grows in large tufts, and is so stiff in the blade that it causes the horses’ legs to bleed as they travel over it; also with stunted mallee, and a very diminutive species of the honeysuckle tree, the flowers of which the natives crush and steep in water, in order to obtain what is to them a sweet and nourishing drink. The emu and the lowan are the only birds of size on it. The former frequents the open desert, the latter the mallee thickets.25

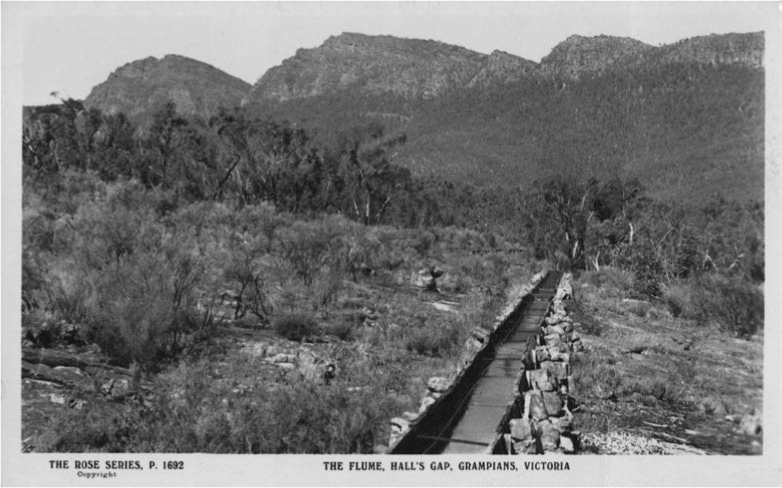

The mountains were the largest water catchment in the region, and by the middle of the twentieth century nearly every drop of this resource had been harvested and diverted to provide water to the plains beyond. The first attempt at such a scheme occurred in 1856, when waters from the Wimmera were diverted by the Wilson brothers into Yarriambiack and Ashens creeks in order to supply the Longerenong run in the east; other pastoralists were often forced to cart water from natural reservoirs for many kilometres.26 From 1875, the mountains were the source of an improved water supply for nearby Stawell, where water had been scarce since the 1850s. Construction of the scheme commenced in 1875 under the guidance of local engineer John D’Alton, who designed an extensive gravity-fed system beginning with a weir on Fyans Creek, 12 km of fluming (Fig 5.3), a 1 km tunnel through the Mount William Range, and along a 24 km pipeline east to Stawell. In all, the scheme took seven years to build and the flume required constant maintenance, but in 1881 it was perhaps the most elaborate piece of water engineering in Victoria.27

Fig. 5.3. A section of the fluming from John D’Alton’s Stawell water supply scheme. Photo: Rose Stereograph Co. State Library of Victoria.

In 1885, a natural basin in the ranges at Wartook was built up into a larger reservoir on the MacKenzie River, and a series of weirs and channels built to transport water for domestic, stock and irrigation purposes from the Mount William Creek and Wimmera River to Horsham and the Wimmera district.28 This was the beginning of numerous schemes through the ranges that would take water northwards into the parched Wimmera and Mallee plains. Lake Lonsdale was constructed in 1905, and control of the headwaters for all rivers and creeks originating in the mountains came under the State Rivers and Water Supply Commission of Victoria in 1906. Channels into the Wimmera were substantially extended in the first three decades of the twentieth century. Over 1600 km of channels serving 8550 km2 was expanded to 9600 km of channelling providing water to some 28 000 km2 of land to the north. The Upper Glenelg Diversion Channel was constructed in 1932, taking water from the south into Wimmera storages. In the same period, storages at Lake Fyans and at Taylors and Pine lakes were constructed. Moora Reservoir was built in 1933 to store floodwaters from the Glenelg. The Rocklands Reservoir was completed in 1953 and stored diverted water from the Glenelg River in the south for the Wimmera River in the north. In 1967, Lake Bellfield was formed by damming Fyans Creek. In the end, the Wimmera Mallee Domestic and Stock Channel System, as it would come to be known, was one of the largest in the world. Its 17 500 km of channels supplied water to 2.9 million hectares of land, 36 towns and 20 000 farm dams. Much of this water came from Gariwerd. The system was made up of open channels that were subject to clogging with drifting sand and soil, seepage into the surrounding land and, above all, evaporation: by the time the water had reached the northern extremities of the system, some 85 per cent had evaporated. Thus in 2010 a new closed, piped system replaced the open system and the channels and structures of the old supply were decommissioned by 2014.29

The water resources of the mountains would become so important in the lives of Victorian farming communities that, in 1938, pastoralists were no longer permitted to lease land in the ranges for grazing. At a meeting of the Horsham, Dimboola, Arapiles, Wimmera, Borung, Kowree, Karkaroo and Lowan councils with the Forests Commission and Water Supply Commission in March 1938, representatives discussed ‘the importance of the Grampians water catchment area, without which the continued settlement of a productive province would be rendered impracticable’ and urged that the entire area, including forest reserves and unoccupied Crown Lands, be placed under the control of the Forests Commission. They resolved that ‘no further alienation of Crown lands be permitted. That leases and licenses to permit grazing of sheep and cattle on lands comprising the catchment be terminated immediately’. They also proposed that ‘milling of timber and stripping of wattle bark in the area be permitted only after consultation with the State Rivers and Water Supply Commission’, and that ‘in view of the necessity of preserving the natural vegetation at its maximum, so that the run-off may be regulated and erosion minimised, adequate funds should be made available to the Forests Commission for the proper development of areas and for complete protection from fire’.30

While communities to the north of Gariwerd – sometimes far to the north – had come to rely heavily upon the ranges for their water resources, from the nineteenth century and well into the twentieth century many local industries had emerged to make use of the mountains’ various assets. Although grazing in the water catchment fell out of favour, other industries continued apace, including forestry and mining.

Industry and diversification

By the end of the nineteenth century, the pastoral land around Gariwerd had proved productive and profitable, but the mountains themselves had been generally too steep to graze and too rocky to plough. In an article on the prospects for farming in the region published in The Australasian in 1902, the writer noted that, on the flats between the ranges, ‘Most of the land in this locality is utilised for grazing purposes only, though in many parts it is eminently suited for intense culture of all sorts. The climate in winter is slightly colder than in most parts of Victoria, but in summer amongst the ranges it is deliciously cool, comparatively, and in sheltered portions, such as Hall’s Gap, the grass is green and succulent through the whole summer.’ The author said that the countryside was ‘for the most part thickly timbered, but, where rung [ringbarked], the natural fertility of the soil is evidenced by the abundant growth of grass and herbage; ferns are plentiful, but with persevering treatment are readily got rid of’. The mountains, then, might represent further opportunities for development and exploitation.

It was trees and timber in particular that Gariwerd had a comparative excess of – compared, of course, with the surrounding plains – and these represented an economic opportunity in many ways. ‘Wattles – mostly Acacia decurrens or black wattle – grow luxuriantly everywhere,’ noted The Australasian, ‘and with the bark selling at £7 per ton on the average, good paying results are obtained from stripping … very little wattle-sowing and cultivation is practised, the majority of holders trusting to the natural growth.’31 Bark had many uses: in 1878, Ferdinand von Mueller was sent by the Victorian Government to the ranges to ‘enquire into the prospect of continuing the supply of tannersbark of Acacia decurrens & your A. pycnantha along with what is needed for the local tanneries here in years to come’.32 In addition to bark, which was also used in the construction of earlier housing, charcoal production was an important industry for the mountains, along with harvesting for firewood.

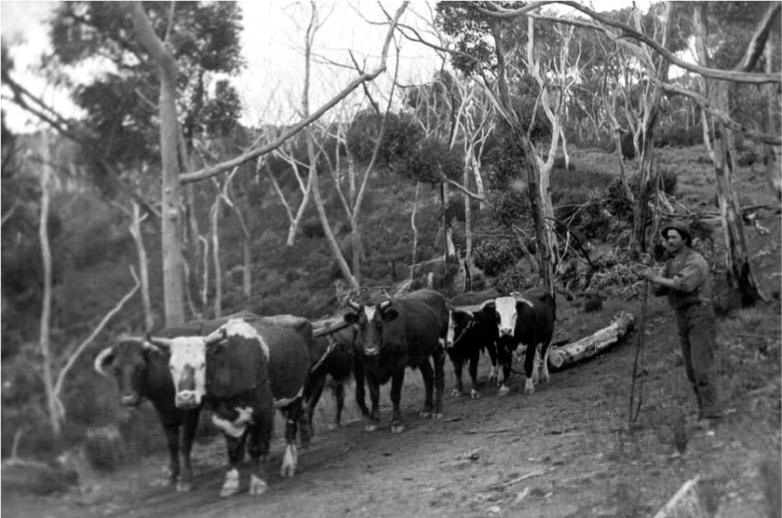

From the 1850s, with nearby goldfields at Stawell and Ararat, the timber of the mountains was utilised for constructing railways and mining infrastructure, as well as for burning in steam engines and for charcoal in ore-processing. Sawmills located at Fyans Creek, Stony Creek, Borough Huts, Wartook, Cranages and Strachan’s huts were steam powered and frequently mobile: mills were placed at sites near to forests to be logged. Bullocks and tramlines provided further means of transportation (Fig 5.4). From 1907, the mountains were declared a State Forest under the control of the Forests Commission. In areas of heavier annual rainfall, common hardwoods for harvest were messmate and brown stringybark, as well as manna gum and mountain grey gum; these mixed forests, sometimes up to 30 m tall, yielded hardwood for house construction, farming and sawlogs for over a century of intensive logging. At Woohlpooer near the Victoria Range, river red gum and yellow gum were harvested along with yellow box, grey box, long-leaf box, red box and red stringybark, producing heavy, durable timber used for house stumps, railway sleepers and fence posts. From the 1920s, softwoods were planted to boost the local industry. The ranges were controlled by the Forests Commission as the Grampians State Forest until 1984; of its 216 000 ha, some 154 000 ha were harvested as Reserved Forest and the remaining 62 000 ha were Protected Forest for recreation and conservation.33

Fig. 5.4. A bullock team hauls logs in the mountains. Photo: AJ Campbell. Museums Victoria.

The remnants of Gariwerd’s historic timber industries can still be found strewn across the local landscape. Some of it is barely detectable, such as the stone wall ruins and several mature, exotic trees that were established near John Childe’s abandoned milling operation near the junction of Fyans and Glenbower creeks, where he intended to generate power using a water wheel. Sanderson’s Gap Track, a sawmilling track named after the prominent sawmilling family, was previously used in the 1890s by field naturalists and excursionists. The Sandersons operated the Basin sawmill site on the west side of Fyans Creek in the 1930s; it was the only mill burnt out by the 1939 fires, when workers took refuge in nearby concrete pipes. Elsewhere, all that remains from the Green Creek Road sawmill that operated at the turn of the twentieth century are a series of pits, trenches and a yard. At Stony Creek, large sawn logs, a series of trenches and depressions and a stone and earthen structure are reminders of a sawmill and tramway from the 1920s. The present-day Mount Difficult Plantation camping ground was once a forestry camp for workers at the softwood plantations established nearby in 1926; in the 1930s, men working in the forests for unemployment relief also used the camp. At Strachan’s Hut and sawmill, where one Allan McIntyre operated a sawmill in 1939 and later sold to the Strachans in Hamilton, a timber hut that remained was destroyed in bushfires during 2013 and later rebuilt using local logs. On the edge of the Borough Huts picnic ground, three large, cylindrical iron kilns – used for charcoal production in the 1940s – speak of a revived wartime charcoal industry that emerged as an alternative for petrol in internal combustion engines.34 Near the MacKenzie Falls, the remnants can be found of Harold Smith’s sawmill operations, established in the 1930s to provide his Horsham timber and hardware store with materials. Traces in the form of ruined cottages and gardens, steam engines and a sawdust heap speak to the two decades during which the mill operated, employing up to 15 workers who would travel each day to Long Gully and fell trees by hand with axes and crosscut saws. In 1950, a fire in the mill destroyed thousands of pounds of equipment. The removal of sawmills from the forests to the towns in the aftermath of the 1939 fires meant that Smith’s mill was never rebuilt.35

Beyond forestry, industry in the mountains themselves continued to intensify and diversify. One observer noted in 1902 that around Hall’s Gap ‘there are rich black flats of excellent quality; these, if drained when necessary, are capable of producing nearly anything; potatoes and onions, lucerne and clovers, cocksfoot, and many other grasses, and nearly all root crops may be grown to perfection. A considerable portion of these valuable flats is at present uncleared or merely rung, and used for grazing purposes, but that it has first-class capability has been proved beyond a doubt.’36 Beyond livestock grazing, the mountains appeared to hold great potential for agricultural diversification. In some parts, particularly on the eastern flanks of the ranges, fruit growing had been successful:

In some portions excellent fruit is grown, notably apples, pears, plums, gooseberries, raspberries, currants, quinces, peaches, apricots, and oranges, but the apples and pears attain the greatest perfection; and, from the fact of their being so readily preserved, the risk of loss with them through unseasonable weather or a glutted market is reduced to a minimum.37

Besides fruit, tobacco was produced in significant quantities near the mountains during the early decades of the twentieth century. Some fruit orchards – promising though they were – were eventually replaced with more profitable tobacco enterprises. In 1913, it was reported that ‘an experimental plot (1 acre) was recently planted at Hall’s Gap, Grampians, and during the week, Mr. Temple Smith, Government tobacco expert, visited there, and delivered a lecture on tobacco culture. On visiting the plot he expressed his surprise at the excellent quality of tobacco grown, and held a field demonstration on the cutting and curing of the leaf.’38 By the early 1920s, a tobacco-growing syndicate had been formed in the area with the hopes of ‘growing tobacco on the slopes of the Grampians, at and near the Pomonal orchard settlement, and to encourage settlers and others to embark in the industry if it should prove to be profitable.’39 Within a few years, The Age reported, ‘The results have been excellent, and the returns, at their very best, have been very gratifying … Most of the Pomonal apple growers have had small experimental plots [and] there is an unlimited demand for such sample as the Grampians growers have been producing when the season has been right.’40 In 1930, Temple Smith became involved as a director of a new scheme operating as Australian Tobacco Plantations Ltd, which sought to boost Australia’s share of the tobacco trade. In the past, despite a suitable climate and soils, the industry had ‘made no progress. Cultivation in the Pomonal district, however, has recently been more encouraging and the leaf produced has been notable for its attractive colour for the trade.’41

In these boom days, ‘People with dreams of fortunes made by growing tobacco in a big way formed companies to acquire large areas of land. Timber was grubbed and kilns for drying the tobacco were erected.’ But with boom came bust: ‘The kind of leaf they were able to show the buyers very soon became a drug on the market. Presently the buyers refused to buy and the bottom fell out of tobacco completely.’42 The federal government ended subsidies to the industry, and relaxed restrictions on overseas imports. What remained of the unprofitable tobacco industry on the eastern slopes of Gariwerd was destroyed in the Black Friday fires of January 1939. The Horsham Times observed in 1940 that ‘Thousands and thousands of pounds went into Pomonal, but never came out of it again. Today the kilns are all gone. Not a single leaf of tobacco is grown there now … To-day, Pomonal, once rated as the finest tobacco country in Victoria, is in disgrace.’43

Another industry once prominent but soon lost was goldmining. In January 1897, a Melbourne newspaper shared a story with readers that, by the end of the nineteenth century, was symbolic of a decades-long search for gold in the Gariwerd mountain ranges. In the spring of 1896, a man named Edmund David left Wartook to explore the mountains for gold. With the expectation of being able to hunt animals, he brought with him only two days of food, but a good supply of ammunition. ‘The first week or two was spent in collecting specimens and exploring for gold’, the story recounted. ‘He had been shooting rabbits, kangaroos and birds for food, varying his diet with wild pigs, which are numerous. At night he took shelter in caves, and stayed a few days, occupying himself in short excursions from his camp.’ Soon he found himself in trouble:

He was without food after his ammunition had run out for five or six days, and felt very weak. His last meal was an iguana. On the sixth day he became too weak to carry his swag, but after a desperate effort he scaled a range and saw beyond country he knew. He made his way to an out station of Elliot Bros, ravenous and in tatters. For six days his only food was iguana, and for nearly six weeks he had not had a particle of bread, living on the roasted flesh of the game he shot. He is now recovering slowly from the effects of starvation and exposure, but it will be long before he is fit for work again.44

The story of gold in Victoria is replete with such frustrated quests for fortune, but it is particularly emblematic of the search for gold in Gariwerd. Starving, almost dead, Edmund David found no gold, and likely had no sound evidence to truly believe he would find much, if any at all, throughout his explorations. The experience of Gariwerd goldseekers in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, like that of Edmund David, was often one of frustration.

Against the backdrop of discoveries in New South Wales and elsewhere in Victoria in the middle of the nineteenth century, goldseekers had turned their eyes to the Gariwerd mountain ranges in particular. While surrounding regions did yield sizable quantities of gold, the mountains – perched so charismatically as they were above the otherwise flat western plains – were the subject of especially eager speculation. At a public lecture in Geelong during 1851, the German geologist George H. Bruhn told the audience that the goldfields in New South Wales were ‘analogous to the rich gold fields of the Ural, in Siberia; our Grampians, Pyrenees, Mount Alexander, and all exhibit the same characteristics.’ The outward similarity of these ranges and mountains with other gold-bearing regions in Australia and the world, he argued, meant they too would bear gold.45 Bruhn was partially correct – the Pyrenees Ranges had, in fact, already been the site of a suppressed goldrush in 1849 – although his predictions for Gariwerd itself mostly did not materialise.46

From these early years, a pattern of unrealised hope was established for Gariwerd goldseekers. Newspapers reported in May 1855 that the ‘news from these diggings is cheering. A gentleman arrived in town yesterday, bringing about 30 ounces of gold of a coarse nuggetty description, some pieces, weighing from 1 to 1 1/2 ounces. The diggers on Hard Hill and Black Man’s Head are all doing well. A nugget of 8 lbs. is reported to have been taken from Hard Hill last week; and a fine specimen was brought to the Belfast Store on Monday last, and weighed 8 ounces. Provisions are reasonable, flour selling at six pounds ten shillings the bag. The population is about 2,500.’47 In 1857, in contrast, another writer lamented that ‘I myself lost my whole fortune in conducting prospecting parties … to search for gold’ in Gariwerd, and hoped to prevent his ‘fellow colonists from ruining themselves also, on the same forlorn hope.’ He noted that although ‘auriferous ground to some extent’ could be found at the foot of Mount William and around the Black Ranges – where a £1000 reward was offered for the discovery of gold – neither ‘at the Grampians, the Victoria, nor the Dundas Ranges … is there the slightest prospect of a workable gold-field’.48 Despite the rich gold country around nearby Stawell and Ararat, to those with rudimentary geological knowledge, the sedimentary rocks of the Gariwerd mountains themselves seemed to hold little promise for those who came to Victoria from the mid-nineteenth century seeking fortunes.

Towards the end of the century, hopes were raised again. In 1897, Fred D’Alton found granite on his land at Stony Creek near Halls Gap, and then found gold. Kept secret for several months, sluicings from gold-washing eventually revealed the location of the site to downstream workers.49 A correspondent for The Age in Melbourne informed readers that the site ‘may be found by following the course of the Stony Creek about 3 1/2 miles as the crow flies – but mostly over a route impassable for vehicles, or even a laden pack horse.’50 One newspaper reported in April of that year that ‘Some excitement has been caused by reports that have been circulated to the effect that gold has been discovered at Stoney Creek, in Hall’s Gap.’ It observed that ‘Several claims have been pegged out, both for alluvial and quartz, several very fair prospects having been obtained.’ A spokesperson for the Mining Department reported that the prospectors have found ‘a little gold, and [was] of opinion the locality will repay further prospecting.’51

However, another observer reported shortly afterwards that ‘the sinkings are shallow, and the prospects so far show small yields. (The best prospect seen was 2 gr. to the dish) … The surface indications are not favourable from an old miner’s point of view.’52 Nevertheless, the population of Halls Gap doubled for a time as a small but short-lived rush ensued. For these unfortunate prospectors, Stony Creek would yield very little gold, even when its flats were dredged with equipment imported from New Zealand.53 That a new goldfield would be discovered in western Victoria therefore seemed unlikely by the end of the century. The Australian mining industry in the late nineteenth century experienced an economic and technological revival, but its heartland moved north and west from the coast of eastern Australia to regions of low rainfall and high evaporation. In these sparsely populated regions, new goldfields were discovered in older, Precambrian rocks – around Mount Isa, Kalgoorlie and Broken Hill, for instance – that had not been mined before. As the industry transformed in the wake of these discoveries, Victorian gold towns that had not become self-sustaining by this point began a period of decline that trailed into the twentieth century.54 Gariwerd however, would yet yield a surprise.

Along with the Precambrian discoveries, some smaller goldfields were uncovered in eastern Australia after the 1880s. These fields, such as one found in western Tasmania, were located within Palaeozoic rocks hidden away in inaccessible and inhospitable broken country and well-timbered areas. In 1897 two splitters, Arthur and David Schache, discovered gold in a steep gully draining the eastern side of Mount William, overlooked by earlier prospectors, where an intrusion of quartz-rich igneous rock, granodiorite, laid down in the Devonian period, could be found.55 These granitic rocks also formed a basin in the MacKenzie River area, and created the low, rounded hills in Victoria Valley. Such geological formations are ideal for goldseekers. Despite earlier disappointments, this discovery would spark a great rush to Gariwerd during the early twentieth century. The Schache brothers told Phillip and Frank Emmett, who were in the mountains on a shooting trip. The Schaches had not found payable quantities of gold, but when the Emmetts – experienced goldminers from Ararat – returned and prospected the area, they promptly made a claim at the end of June in 1900. At least one of the Schache brothers, on the other hand, left Victoria for the Boer War in South Africa.56

Within a fortnight of the Emmetts’ claim, a rush had begun to the Gariwerd mountains, and gold had been discovered in ten more gullies.57 Thousands of goldseekers converged on Mount William in the weeks that followed. Beyond the lure of riches, how a rush of this size and speed might have occurred is perhaps best accounted for by the fact that Victoria, by the turn of the century, was a much different place from the nascent Australian colony of the 1850s. As one journalist observed, ‘In the old times everything was new. There were literally no roads, no farmhouses, save, perhaps, a station here and there, no fences, and where forests existed they were still in a state of nature. People bound to the rush were mostly on foot, and carried their belongings on their backs … Now, however, all is changed.’ Victoria’s population was significantly larger now and mining, transport, and communication technologies were considerably more advanced. News of the discoveries spread with greater ease and speed than ever before, while travelling to the new goldfields in the west of Victoria was now a more realistic proposition for many. ‘We roll along a well-made road, past well-appointed farms and orchards,’ observed an Australian Town and Country Journal correspondent on his way to the Mount William goldfields in the middle of 1900:

We pass old and long abandoned gold fields; the land is all fenced and subdivided into paddocks, and some of the fields well-cultivated. There people are many of them in vehicles of some sort, or, at all events, have their swags carried in a carriage of some description … The people, too, had changed in their dress and speech. The old miner was mostly clad in fustian; but the new miner wears cloth of some description. He also talks a different dialect, and hails from Victoria, New South Wales, or Tasmania, instead of, as in the old times, from the British Isles.58

Primarily sluicers and fossickers, it is popularly claimed that up to 10 000 goldseekers were on the new Gariwerd field in the following weeks. It was to be one of the last old-style rushes in Victoria, although from the outset it was met with scepticism. As one writer opined in the middle of July: ‘There is little reason to hope that 50 years hence the elderly residents of Mount William will be speaking of the nineties as the surviving pioneers of Bendigo, Ballarat, Forest Creek, and the Ovens now speak of the fifties.’ The newspaper’s correspondent continued:

Ararat people say that the rush is a ‘new Bendigo’. In at least one respect, the comparison is justifiable. Stories of Bendigo in the ‘fifties’ occasionally magnified ounces of gold into pounds, and pounds into bucketfuls. In the case of Mount William there is a strong tendency to declare pennyweights to be ounces, and to entirely understate the difficulty of unearthing payable wash. But it is impossible to exaggerate the stirring effect which the reported discoveries have had upon the populations of every town and village within 50 miles of the scene of the discoveries.59

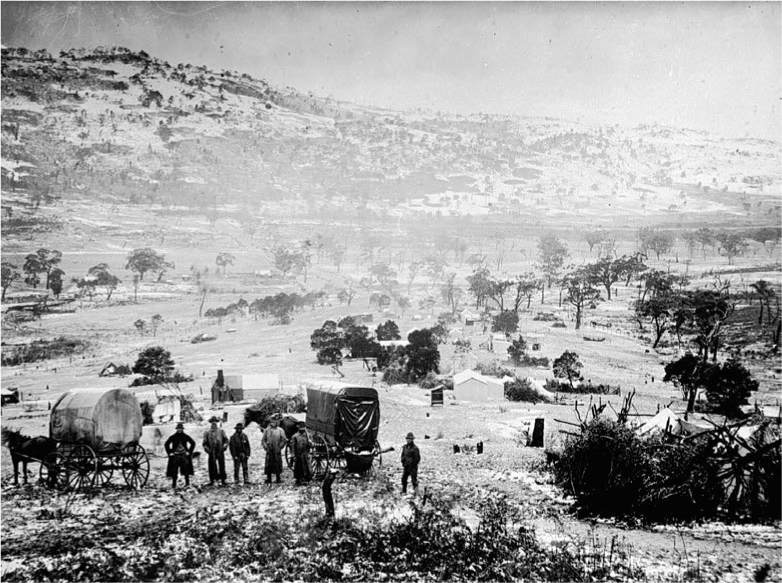

When the acting director of the Victorian Geological Survey, Hyman Herman, visited the fields in July 1900 (Fig 5.5), his first report was less than optimistic. Herman wrote that despite numerous rumours, no reefs or dykes had been discovered to account for the origins of the alluvial gold. ‘I can ascertain nothing reliable as to yields,’ he reported, ‘except that a good many statements concerning them are very unreliable.’ While he believed some claims already pegged out on the field might yet obtain good yields, Herman nevertheless believed that ‘there is absolutely no room for the large number of men present on the ground. A considerable number have left since my arrival last Friday [20 July 1900], but there must be, I think, fully 3000 or 4000 here yet.’60

Whatever early excitement there might have been, disappointment soon set in. ‘The crowds of poor and idle men who were seen upon the field in July last had departed,’ recorded one correspondent for The Age by January of 1901. ‘The little community had thinned down to the most prosperous. As to how many miners there are on the field there is some degree of doubt. It is estimated that the total population is about 2000, and this estimate is probably a fair one.’61 By the end of March 1901, when the government census was taken, there were 879 people remaining on the Mount William goldfields.62 Nonetheless, the vestiges of the rush in the winter of 1900 would linger for a decade and a half in the Gariwerd mountains. Soon after the first discoveries, two small townships were established near the Mount William goldfields to service both the permanent and transient population of miners and their families. Mafeking and Ladysmith were, in the early days, bustling with activity. When a government delegation visited the goldfield at the end of January 1901, at the height of summer, the correspondent provided a vivid account. ‘As the gullies near at hand have been worked out, settlement has crawled ahead along the thickly-wooded ravines in the mountain, and, after climbing Spion Top, the precipitous heights above Ladysmith, the visitor encounters the township of Mafeking sprinkled about the forest of towering gums, and stretching away into the mountain wilderness until the last of its huts and tents is altogether lost to view in the bush.’ He continued to observe:

Fig. 5.5. The Mafeking goldfield after snow in 1900; trees had been cleared in the surrounding area for use on the diggings. Photo: Museums Victoria.

Once at the top of Spion Top the houses of Mafeking burst into view. At almost the same moment three or four barefooted little children, who had been making a play of broken crockery, 50 yards from a tent, disappeared in the undergrowth with the speed of terrified rabbits … Mafeking was holding high holiday. A piano was strumming and a stentorian voice was singing ‘I Went With Him’ in a tent labelled with the name of a well-known pugilist. Women were standing at the doors of the tents, huts and cottages; the clicking of billiard balls sounded from within the larger wooden structures, and a young woman was tripping along Baden Powell Street in company with a male attendant … The new bar maid was on her way to the hotel on the fringes of the dense bush.63

In the end, only around 25 000 ounces of gold – about 710 kg – was mined from the Mount William goldfield.64 The Gariwerd finds barely registered on government mining reports and were overshadowed by the newer Australian mining operations; Western Australia produced one-and-a-half million ounces of gold in 1900 alone.65 Today, there is little physical evidence of the Mafeking goldfield, but a visit to the remote field reveals some well preserved, if very overgrown, evidence of shallow alluvial diggings and hydraulic sluicing. Of other past mining enterprises, more can be seen. At the Heatherlie Quarry, or Mount Difficult Quarry, an open-cut, high-quality sandstone quarry was in use from the early 1860s. In the following years, Grampians sandstone – also sometimes referred to as Grampians freestone or Stawell freestone – would be quarried for use in the construction of several significant buildings in Melbourne, including the Town Hall and Parliament House; some stone is still extracted from the quarry for use in minor repairs. Apart from the obvious effects of stone quarrying on the surrounding landscape, remnants of the industry can be seen in the ruins of two stone cottages, along with a variety of industrial miscellanies including winches, hoppers, a boiler and steam engine, storage tanks and compressors, a boom, trolley and crane, and a magazine for explosives used in the mining operation. When the Taylors Lake and Pine Lake storage dams were constructed in 1919 and 1928, beaching stone was quarried at Mount Zero, where the formation of a 16 km horse-drawn tramway to Taylor’s Lake can be seen.66

Recreation and tourism

Although scientific interest in the ranges had continued to develop, and resources were increasingly exploited, perhaps the most substantial change in the mountains over the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries was the growth of tourism and recreation in the ranges. The 1868 Guide for Excursionists from Melbourne enticed the city-dwelling populace with the promise of an escape from the metropolis and its ills. ‘Thus for five pounds each we can leave Melbourne one hundred and eighty miles behind us, and escape for a while from the dead-locks, the Ministry, the Opposition, The Age, The Argus, the churches, the theatres, and all the turmoil and hurry – to say nothing of the smoke and malodours – which enter so largely into Melbourne life; and freshen our wits by getting an insight into various modes of life in another part of the country.’ The guidebook continues: ‘To he who likes to escape for a while from the conventionalities, and to be brought for a while face to face with Nature in her solemn, grand and eternal beauty, we say: Try the Grampians.’67

By the end of the first decade of the twentieth century, tourism to the ranges had become a popular pastime, and railways played no small part in their remaking as a holiday destination. Travellers from Melbourne could catch a seven-hour morning journey, or the five-and-a-half-hour afternoon express train to Stawell. ‘Fine excursions may be made from Stawell to the picturesque spots in the Grampians,’ noted the Picturesque Victoria and How To Get There tourist guide, a publication issued by the Victorian Railways: ‘that to Hall’s Gap, 17 miles from the town, being a popular trip.’ From here, visitors could access ‘the Turret Falls, Silver Band Falls, Venus’ Bath, and the Devil’s Pool’, and at the junction of Fyans and Stony Creeks ‘numerous family parties annually spend their summer vacations in their own tents in the shelter of this romantic valley’. Venturing further, tourists also trekked to Rose’s Gap, the Mount Difficult quarries, and the Wartook Reservoir. ‘Tracks are now being cut to some of the high peaks in the vicinity,’ promised the guidebook, ‘and visitors will find a grandeur in the rocky scenery of the Grampians that is unsurpassed in the whole continent.’ By foot or horseback, Victoria Valley promised a ‘huge State forest where kangaroos and emus are to be seen literally in hundreds … from the camping ground [at Halls Gap] to the valley is a pleasant and easy day’s walk’. For those wishing to stay closer to Stawell, the trip to the ‘Black Range Basin may be made on foot, by walk of 5 miles … The scenery from the saddle of the range is weird and romantic, the granite boulders upon the range having been thrown by some by-gone convulsion of Nature into all sorts of picturesque confusion.’ Finally, ‘No mention of this district would be complete which failed to include reference to the vineyards of Great Western, which play such a prominent part in the viticultural industry of the State.’68

The southern ranges were not as accessible to visitors at the start of the twentieth century but were still relatively well served by a daily morning train from Melbourne, or a night train from Ararat, to Dunkeld. From here tourists could reach Mount Sturgeon and Mount Abrupt at the southern end of the Serra Range. A road took tourists behind Mount Sturgeon westward to the Victoria Valley, a region ‘eminently suitable for reserving for the purpose of a national park,’ it was suggested. ‘Small flocks of emus and occasional kangaroos may be seen by those driving on the rounds around Dunkeld, and they sometimes come as close to the township as Mount Sturgeon,’ Picturesque Victoria informed readers. The guidebook promised that ‘the air in the vicinity of the ranges is cool and bracing, especially suited to the requirements of those who enjoy camp life and can appreciate the delights of a holiday under canvas.’69

While the railways first opened Victoria to tourists, travel by car also began its steady rise to ascendancy in the early twentieth century. The Country Roads Board was established in 1912, charged with the responsibility for roads that had once been the concern of now under-resourced local shire councils. At this time, there were more than 12 000 motor vehicles registered in the state. Guest houses had begun to appear in Gariwerd to cater for these travellers, who now enjoyed a small network of tracks across the ranges. By 1929 there would be almost 600 000 cars in Victoria. As car ownership increased, so did the quality of roads. In 1922, the Victorian Country Roads Board was given responsibility for a new category of roadways: tourist roads. This enabled the Board to extend its hard, gravel roads across the state, including the Great Ocean Road, and to open new areas for tourism.

In 1923, the Hamilton branch of the National Roads Association of Australia spearheaded an effort to connect the Wimmera and Western Districts via a southern road into Gariwerd. ‘A spirited movement is on foot in the Stawell and Hamilton districts to obtain a good road through the Grampians, from Dunkeld to Hall’s Gap, and thus provide a ready means of communication between the Western and Wimmera districts,’ announced a correspondent for The Argus in Melbourne. ‘Such a route would not only be a boon to the producers, but would open a new province to the tourists. The scenery in the southern part rivals that of Hall’s Gap, but, because of the lack of a good road, only an occasional shepherd, in search of lost sheep, has the privilege of feasting his eyes upon it.’ Locals suggested that the existence of a new road in the south would promote development: ‘Private hospitals would probably be established, accommodation houses on an ambitious scale built, and private holiday homes erected. This road, indeed, is already paved with many good intentions.’70

Road links were soon constructed from Halls Gap to Zumstein, and the Halls Gap to Dunkeld road was completed in 1924.71 The Mount Victory Road, funded by the Tourists Resorts Committee, was perhaps the earliest of these tourist routes, and opened the MacKenzie Falls to visitors. Walter Zumstein blazed the original track to the Falls before a pathway was built in 1939.72 Elsewhere along the road, a track cut by an early shepherd to a lookout – Reed’s Lookout – towards the Victoria Valley was made accessible in 1923, while another 900 m track from this point led to The Balconies.73 The Mount William Tourist League promptly and successfully lobbied for a tourist road from Ararat to Halls Gap; this was opened in 1927, providing a new eastern entry point to the mountains and offering an alternative to the route via Stawell in the west.74 In the same year, the Silverband Road between Lake Bellfield and the Mount Victory Road was opened with funding from the Tourists Resorts Committee.75

The communities of Gariwerd began working to accommodate these travellers through the mountains. In the 1920s, along the MacKenzie River, a group of cottages was built on private land to host tourists; most of them no longer exist, although Cranage’s Cottage, a two-storey iron-clad cottage, can still be found. Using earth and stone and secondhand building materials, Walter and Jean Zumsteins set about building three cottages on the eastern side of the MacKenzie River. When the cottages were completed in 1935, a swimming pool was built and gardens were established; a two-storey timber house that no longer stands, the Redgum Cottage, was also constructed.76

From the 1920s and 1930s onwards, recreation and tourism in the mountains therefore became a popular pastime for Victorian families, and the evolution of rail and road travel in this time played no small part. While industry in the mountains continued to develop and change, it was perhaps the scientific interest of the ranges combined with its popularity with the public that were most influential in its eventual declaration as a national park. This recognition of its natural assets and conservation values did not occur until 1984, and debates over the mountains in the intervening years revealed the tensions that had developed over the late nineteenth century and into the twentieth century between the value of extractive industries in Gariwerd and the ranges’ national importance as a botanic and wildlife reserve.

Endnotes

1.Mitchell T (1839) Three Expeditions into the Interior of Eastern Australia. Vol. 2. T & W Boone, London, pp. 177–179.

2.Mitchell (1839), p. 175.

3.Mueller F (1853) Letter to John Foster. Melbourne, 22 August, Melbourne. D53/8374, unit 203, VPRS 1189 inward registered correspondence, VA 856 Colonial Secretary’s Office. Public Record Office, Victoria, Melbourne.

4.Mueller F (1853) Letter to William Hooker, Victoria Range, 21 November. In Hooker WJ (Ed.) (1854) Hooker’s Journal of Botany and Kew Garden Miscellany. Vol. 6. Reeve, Benham, and Reeve, London, p. 156.

5.Mueller F (1853) Letter to John Foster. Mount Sturgeon, 23 November. D53/12043, unit 203, VPRS 1189 inward registered correspondence, VA 856 Colonial Secretary’s Office. Public Record Office, Victoria, Melbourne.

6.Mueller F (1853) Letter to William Hooker. Torrumbarrey, 5 November. In Hooker (1854), p. 157.

7.Mueller F (1854) Second General Report of the Government Botanist of Victoria, on the Vegetation of the Colony. In Hooker WJ (Ed.) (1855) Hooker’s Journal of Botany and Kew Garden Miscellany. Vol. 7. Reeve, Benham, and Reeve, London, pp. 306–307.

8.Mueller F (1857) Report on the Botanic Garden, 25 August. Department of Public Works as No. 4301, unit 3, p. 196, VPRS 963. Public Record Office, Victoria, Melbourne.

9.Moje C (2014) Wilhelmi, Johann Friederich Carl (1829–1884). Encyclopedia of Australian Science, <http://www.eoas.info/biogs/P005437b.htm>.

10.Mueller F (1858) Letter to Daniel Bunce, 30 April. MS 13020, Box 4/1. State Library of Victoria, Melbourne.

11.Mueller F (1858) Report of the Government Botanist – 24 October 1858. John Ferres, Melbourne, p. 6.

12.Mueller F (1858) Letter to William Hooker, 15 June. Directors’ letters, vol. LXXIV, Australia letters 1851–8, letter no. 181. Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew.

13.Gillison J (1981) Henrietta D’Alton and her family. MS000725, Box 207–15. Royal Historical Society of Victoria Manuscripts Collection, Melbourne.

14.D’Alton St E (n.d.) Letter [with specimen of Trymalium daltonii] to Ferdinand von Mueller. MEL 56066. National Herbarium of Victoria, Royal Botanic Gardens, Melbourne; Mueller F (1875) Fragmenta Phytographiae Australiae 9(78), 135.

15.D’Alton St E (1894) Letter to Ferdinand von Mueller, 25 August. RB MSS M56. Library, Royal Botanic Gardens, Melbourne.

16.Sullivan D (1884) Letter to Ferdinand von Mueller, 16 January. RB MSS M19. Library, Royal Botanic Gardens, Melbourne.

17.Sullivan D (1883) Letter to Ferdinand von Mueller, 6 June. MSS M19. Library, Royal Botanic Gardens, Melbourne.

18.Calder J (1987) The Grampians: A Noble Range. Victorian National Parks Association, Melbourne.

19.Mueller F (1886) Letter to the Gardeners’ Chronicle, 17 July.

20.Mueller F (1863) Letter to Joseph Decaisne, 25 April. Von Mueller Correspondence Project, <http://vmcp.conaltuohy.com/xtf/view?docId=tei/1860-9/1863/63-04-25a.xml>.

21.Sonder W (1868) Letter to Ferdinand Krauss, Hamburg, 28 July. Von Mueller Correspondence Project. <http://vmcp.conaltuohy.com/xtf/view?docId=tei/Mentions/Selected%20Mentions%20letters/M68-07-28-final.xml>.

22.Audas JW (1925) One of Nature’s Wonderlands, the Victorian Grampians. Ramsay Publishing, Melbourne.

23.Thomson AT (1853) in Bride TF (Ed.) (1898 [1969]) Letters from Victorian Pioneers. Heinemann, Melbourne, p. 328.

24.Carfrae J (1853) in Bride TF (Ed.) (1898) Letters from Victorian Pioneers. RS Brain, Melbourne, p. 9.

25.Clow J (1853) in Bride (1898), p. 112.

26.Calder (1987).

27.Heritage Council of Victoria (2019) Stawell Water Supply Scheme. Victorian Heritage Database, <https://vhd.heritagecouncil.vic.gov.au/places/13595>.

28.‘Wartook storage: A visit of inspection’ (1885) The Horsham Times, 13 October, p. 3.

29.Veldhusen R, McIlvena B (2001) Pipe Dreams: A History of Water Supply in the Wimmera-Mallee. Wimmera Mallee Water, Horsham; Grampians Wimmera Mallee Water (2018) The Historic Wimmera Mallee Channel System. GWM Water: History of Our Water Supply, <https://www.gwmwater.org.au/our-water-supply/history-of-our-water-supply/the-historic-wimmera-mallee-channel-system>.

30.‘Grampians water preservation plans’ (1938) Weekly Times, 26 March, p. 16.

31.‘Farming in the Grampians’ (1902) The Australasian, 20 August, p. 11.

32.Mueller F (1878) Letter to George Bentham, 28 February. Kew correspondence, Australia, Mueller, 1871–81, ff. 207–8, Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew.

33.Calder (1987).

34.Land Conservation Council (1997) Historic Places Special Investigation: South-Western Area Final Recommendations. Land Conservation Council, Melbourne.

35.Horsham Historical Society and Parks Victoria (n.d.) Information sign at Smiths Mill Campground, Grampians National Park.

36.‘Farming in the Grampians’ (1902).

37.‘Farming in the Grampians’ (1902).

38.‘Tobacco growing in the Grampians’ (1913) The Age, 5 May, p. 9.

39.‘The Grampians for tobacco’ (1926) The Age, 2 February, p. 5.

40.‘The Grampians for tobacco’ (1926).

41.‘Tobacco scheme’ (1930) The Telegraph [Brisbane], 19 June, p. 7.

42.‘Pomonal and its tobacco boom’ (1940) The Horsham Times, 4 June, p. 1.

43.‘Pomonal and its tobacco boom’ (1940).

44.‘Exploring the Grampians’ (1897) Leader [Melbourne], 2 January, p. 23.

45.‘The Victoria Gold Field’ (1851) Sydney Morning Herald, 20 August, p. 2.

46.Wilkie D (2014) 1849: The rush that never started: forgotten origins of the 1851 gold discoveries in Victoria. PhD thesis. School of Historical and Philosophical Studies, University of Melbourne, Australia.

47.Portland Guardian and Normanby General Advertiser (1855) 21 May, p. 3.

48.‘Gold on the Glenelg’ (1857) The Age, 20 June, p. 4.

49.Calder (1987).

50.‘Stony Creek Diggings, Grampians’ (1897) The Age, 17 April, p. 5.

51.‘Gold in the Grampians’ (1897) The Ballarat Star, 13 April, p. 4.

52.Stony Creek Diggings, Grampians (1897).

53.Calder (1987).

54.Blainey G (1969) The Rush That Never Ended. Melbourne University Press, Melbourne.

55.Flett J (1970) The History of Gold Discovery in Victoria. Hawthorn Press, Melbourne.

56.Australian Town and Country Journal (1900), 28 July, p. 26.

57.Flett (1970).

58.Australian Town and Country Journal (1900).

59.The Age (1900) 16 July, p. 6.

60.‘The Geologist’s Report’ (1900) The Ballarat Star, 25 July, p. 6.

61.‘Mount William’ (1901) The Age, 23 January, p. 8.

62.Census of Victoria (1901) Table XVIII.

63.Mount William (1901).

64.Calder (1987).

65.Office of the Government Statist (1903) Victorian Year Book, 1903. Government of Victoria, Melbourne, p. 434.

66.Land Conservation Council (1997).

67.Hingston J (1868) Guide for Excursionists from Melbourne. H. Thomas, Melbourne. Quoted in Calder J (1987) The Grampians: A Noble Range. Victorian National Parks Association, Melbourne.

68.Victorian Railways (1908) Picturesque Victoria and How to Get There: A Handbook for Tourists. D.W. Paterson Co., Melbourne, pp. 145–148.

69.Victorian Railways (1908).

70.‘Road through Grampians’ (1923) The Argus, 30 January, p. 10.

71.Calder (1987).

72.Land Conservation Council (1997), p. 119.

73.Land Conservation Council (1997), p. 100.

74.Priestley S (1984) The Victorians: Making Their Mark. Fairfax, Syme & Weldon, Melbourne.

75.Land Conservation Council (1997), p. 126.

76.Land Conservation Council (1997), p. 64.