From WZKM 22 (1908): 265-87.

The purpose of this article is to draw attention to a few perhaps not unimportant observations pertaining to the strophic structure of the Koran-observations I myself cannot pursue further as I am fully occupied with other tasks. D. H. Muller based his division of various Koran suras into stanzas on purely stylistic and rhetorical considerations, whereas I came to my all too brief study of the Koran rhymes a propos of reading Vollers's Volkssprache and Schriftsprache.l The results of my investigations were nevertheless surprising, and will soon be published in my review of Vollers's book in Gottinger Gelchite Anzeige. In many respects what I say there overlaps with what I am putting forward here. But here I am making some additional observations, which are not included there because they go beyond what is relevant in that context. Also, quite a few points touched on there are taken up again here and stated with greater clarity and precision.

The Koran text appended by W. N. Lees to his edition of Zamakhshari's Kashshaf gives a division into verses that differs from the text of Flugel's edition. Zamakhshari's text (designated Zam. henceforth) does not merely record the division into suras, and into Juz'2 and verses, as Flugel does, but also makes the rulings concerning pauses and prostrations (Arabic, Rukul) when the text is read out ritually. The Juz' divisions are marked with all manner of signs, corresponding to the extended system of Ibn Tayfur as-Sajawandi and enumerated by Noldeke in Geschichte des Qoran,3 while the rukuc are given the siglum, `ayn L (the Arabic letter). It is a priori obvious that these prostrations must mark the more forceful sections of the recitation and hence also of the textual content.

And this is indeed almost invariably the case, at least in Lees's case. When in some few instances there is deviation from this rule, we are justified in assuming that either the rukuc has been put in the wrong place, or that there has been some disruption of another kind. That this assumption is correct is confirmed in that we find, on the one hand, that no break between two suras is without rukuc, and on the other, that every rukul coincides with the ending of a verse (according to the division in Zam.) 4 It is then striking that the end of a verse that comes at a ruku` often departs from the rhyming context, as with XIII.26; XIV.6, 32; XVI.72; XIX.41 (from verse 35 on in -fin); XXII.34; XXIV.56; XXVIII.28; LXXXIX.30; XC.20; XCIII.11; XCVI.19; XCVIII.8; CXI.5 (further examples in my review in the Gott. Gel. Anz.). Finally, the change in rhyme not infrequently coincides with a ruku (I give numerous examples in my review in that journal).Whether the distribution of the ruku is identical or variable in all recensions of the Koran, or in all Islamic rites, would still have to be investigated. However, that there are fluctuations and differences between the individual recensions is suggested by the fact that Zam. shows in Sura II. 19 after qadiran, a verse division not present in Fliigel- one which at the same time is provided with a ruku. If we now consider those suras that, in the view of D. H. Muller, show strophic divisions, and take into consideration the ruku noted in Zam., then such prostrations are prescribed in Sura VII before verses 57, 63, 71, 83, 92, 98, 106, 124, 127, 138, 146, and 151; in Sura XI before verses 27, 38, 52, 64, 72, 75, 85, and 99; in Sura XV before verses 16, 26, 45, 61, and 80; in Sura XIX before verses 16, 42, 52, 67, and 86; in Sura XXVI before verses 9, 33, 52, 69, 105, 123, 141, 160, 176, and 192; in Sura XXXVI before verse 33; in Sura XLIV before verses 29 and 43; in Sura LI before verses 24 and 31; in Sura LIV before verses 23 and 41; in Sura LVI before verses 38 and 74; in Sura LXIX before verse 38; in Sura LXXV before verse 31; and in Sura LXXVIII before verse 31. In the remaining four suras considered by D. H. Muller, only the beginning and the end are given ruku`. Thus, of the fifty-two ruku enumerated here, only seven-namely those before Sura VII.98, 124, 127, 151; XIX.86; XLIV.29; and LVI.38-are internal to Muller's stanzas, whereas forty-five coincide with the strophic divisions posited by Muller. The textual division conjectured by Muller from the stylistic and rhetorical premises agrees, then, within the thirteen suras being considered, at forty-five out of fifty-two points with the sections marked with prostration in the recension in Zam. What is true of ruku, that do not fall on strophic divisions remains to be discussed in the relevant individual instances. But before I move onto this, I must indicate two features of importance for the strophic structure also of the Koran which I have treated at length in my article in the Gott. Gel. Anz., and to which, in consequence, I need only briefly refer here. In the article I have shown, by comparing Flugel's text with Zam., that the division of the Koran into verses varies considerably in the different recensions; and I believe that from this, we may confidently infer that this division was introduced at a relatively late stage. On the other hand, I have shown there that the division into verses in at any rate these two recensions-probably also in all others-does not keep strictly to the rhyming units of the text, but ignores all manner of internal rhymes and often-intentionally or otherwiseobscures beyond recognition quite complicated rhyme-strophe complexes. I have made it clear with various examples that the ruku' divisions frequently coincide with these complexes. And so all these various features must be kept in mind when studying the poetic forms of the Koran; and in this sense I will now discuss the suras treated by Muller.

SURA I

Sura I shows, in its short construction, an ending in verse 6 that deviates from the rhyme. If we take the rhyme as our criterion, we obtain six lines, with verses 6 and 7 comprised in the final one. The sura divides into two equal parts of three lines each, and in each part the rhyme sequence is as follows: in, im, in. The first half praises God; the second gives the prayer for proper guidance. Possibly the division of the sixth line into two verses was effected in order to bring about the holy number seven in the Fatihah.

SURA VII

A regular division into stanzas is not visible in this sura, as Muller already showed. But if we consider the distribution of the ruku', we can discern a more or less definite subdivision in the contents, which develops in the following way:

(a) verses 1-9. Threat of being called to account at the Last Judgment

(b) verses 10-24. Rebellion of 'Iblis, and the Fall

(c) verses 25-29. The ordering of apparel

(d) verses 30-37. Punishment of unbelievers in hell

(e) verses 38-45. Distinguishing the just and the unjust

(f) verses 46-51. Tardy repentance of unbelievers

(g) Verses 52-56. Evidence of God in nature

(h) verses 57-62. Noah

(i) verses 63-70. Had

(k)5 verses 71-82. Salih (71-77) and Lot (78-82)

(1) verses 83-91. Shu'ayb

(m) verses 92-97. The scheme according to which the prophets were [are] sent

(n) verses 98-123. Practical (moral) applications following therefrom (98-100); dispatch of Moses and conversion of the magicians (101-123).

(o) verses 124-126. Pharaoh's resistance and Moses' encouragement of his people

(p) verses 127-137. Unbelief of the Egyptians and Exodus of the Israelites

(q) verses 138-145. Moses on Sinai

(r) verses 146-150. The Golden Calf and Moses' anger

(s) verses 151-156. Moses' giving of the Law

(t) verses 157-162. Israel in the wilderness

(u) verses 163-170. Legend of Elath

(v) verses 171-180. God's signs in history [or in the story]

(w) verses 181-188. God's punitive court and judgment

(x) verses 189-205. God the refuge of believers.

The ruku, seems not always to occur in the correct place; for instance, it should surely be moved from verse 150 to the division between 152 and 153. The prostration after verse 97 is also noteworthy, and would really be expected after verse 100, which is where Muller places the divide. It comes as no surprise that in this sura, sloppily put together as it is, Miller's divisions are not always confirmed by the positioning of the ruku`. It is all the more to be noted that, where the division according to content, marked by responsion,6 is more evident, Miller's sections coincide exactly with the rukuc. Thus it is precisely the irregularities of this sura that give visible indication that his theory is correct. Closer study of the way the rhymes are arranged would perhaps eliminate many of those irregularities. But such a study would lead us too far afield, and is also made very difficult by the sura's rhyming in the characteristic un-sound. (The [austretenden] rhymes that drop out of 139, 143, 146, 157, 186, are dropped in the distribution given in Zam.)

SURA XI

Muller's strophes verses 27-98 coincide exactly with the rukuc sections, with only the rukuc after verse 46 missing. In this way the Noah legend would divide into only two sections of 11 (2 x 6 - 1) and 14 (2 x 7) lines, and so is strongly analogous to the following legends of Hud, Abraham and Shu'ayb.7 If one takes note of the rhyme formation, the legend of Salih divides likewise into two parts; the first comprising four lines rhyming in ib (fib), as verse 66 forms a single line with verse 67 because the rhyme has dropped out. The second part consists of two lines (verses 69 and 70 + 71), rhyming in iz (ad)8 and introduced by the responsion formula fa-lamma ja'a ... (when our decree issued ... ]. The whole is thus made up of six lines which fits the remaining stanzas (as half?). Incidentally, the structure of the Abraham strophe changes considerably if the rhyme is taken into consideration. It then divides-by splitting verse 84 after mandudin-into two equally long sections of seven lines each, which incidentally are linked by terminal responsion fa-lamma dhahaba ... ar -raw`u wa ja'-athul bushra [verse 77] and fa-lamma ja'a amruna (verse 84). The rhyme is formed by the elements id and ib in all manner of combinations, while in the Shu'ayb strophe, constructed in the same way, two elements terminating in in are entwined additionally in each half. The rest of this sura (not discussed by Muller), which contains practical applications from the Moses legend, also falls-by the ruku, mark after verse 111-into two equally long strophes, linked by their initial wa la-qad 'arsalna Musa bi-' dyatina ... [verse 99] = wa la-qad 'atayna Musa 1 -kitaba [verse 112], and their final responsion wa inna la- muwaffuhum nasibahum ghayra manqusin [verse 111 ] = wa ma rabbuka bi-ghaflin `amma ta'maluna [verse 123], each comprising fourteen lines (if one adds the new verse endings indicated in Zam.: mubinin in verse 99, mukhtalifin in verse 120, and `amiluna in verse 122). The first of the two strophes begins with non-rhyming line (mubinin) and then has two sequences of five lines each, the first four of which in each case terminate in ad, while the fifth (verses 103 and 108) departs from the rhyme but both assonate among themselves (ib = iq). An abgesang (concluding section) of three lines forms the end of the strophe, the first two lines rhyming again in ud, while the third and final line departs completely from the rhyme (manqusin ). The second strophe is much more simply constructed. It begins likewise with a nonrhyming line muribin, followed by a distich in it (u) but the remaining eleven lines terminate in the allpurpose rhyme an.

SURA XV

The ruku, here also come at Muller's strophic divisions, but in such a way that a different division into groups is formed from that advocated by Muller. The first rukuc division accords with Muller's group 1, whereas group 2 would extend only to verse 25, and group 3 begins already at verse 26. In this distribution, groups 2 and 3 would correspond through their initial words-on the one hand wa la-qad ja `alna ft s-sama'i burujan (verse 16) and on the other Wa la-qad khalagna l-'insana (verse 26). This grouping is also justified because of the content, for in group 1 the disposition of the whole sura is given, while group 2 tells of God's care in his creation, and group 3 of the angelic fall of the Iblis. Muller's linking strophe (verses 45-50) is not divided off by the ruku, division in Zam., but belongs there to a group that extends to verse 60 and which, beginning with mention of the joys of paradise, narrates Abraham's visitation by the angels. The next ruku` strophe (verses 61-79) repeats the punishment of the Sodomites, while the final one (verses 80-99), after a brief reminiscence of the affair with Hijr, draws the moral and gives an exhortation to fear of God and to faith. The number of lines in the individual ruku` strophes form the following series: 15 + 10 + 19 + 16 + 19 + 20. Nothing much can be inferred from brief consideration of the rhymes terminating in the an sound. From the distribution of the ruku, it would seem that that the construction of the strophes is somewhat irregular. But I would stress the possibility that larger or smaller units have been lost, bearing in mind that the reports of punitive judgments, known from other suras, have been substantially abbreviated and sharpened into pure exemplifications. In verses 78 and 79, which Muller9 wishes to eliminate, there may be a residual fragment of a longer account. Miller's divisions into groups are not further impaired by the results of the comparison. In particular, to include the linking strophe verses 45-50 (which quite looks as though it did not originally belong in the context of the sura) in the following ruku section is quite intelligible from its origin as an interpolation. As the sense of the section between verses 44 and 51 was already firmly fixed, the intrusion could be reckoned as well with the pre- ceeding as with the following section; the latter was preferred, as the substance of the interpolated piece could just about be suitable as an introduction to the mention of the "friend of Allah," whereas it had no point of contact with the naming of hell, which concludes the earlier section.

SURA XIX

Here, too, the division proposed by Muller is on the whole confirmed. But study of the disposition of the rhymes makes the strophes much more regular than Muller himself assumed them to be, retaining as he did the division into verses of Flugel's edition of the text; for if we eliminate verse 3,10 which deviates from the rhyme, by joining it to verse 4 (so as to make a line comparable in length to verse 5); and if we take note of the internal rhyme taqiyyan verse 14, which in Zam. appears as a special break, so that the correspondence with verse 33 is even more forcefully stressed; then the principal group concerning the Baptist episode (verses 1-15) becomes divided into three equally long strophes of five lines each, assuming that the end of verse 7 (drawn in Zam. together with verse 8) in Yahyd (in the not impossible pronunciation Yahiyyd) rhymes with samiyyan. Even if this assumption is not tenable, the sequence of lines 5 + 4 + 5 remains symmetrical. In the Mary episode, making verses 26 and 27 into one (effected also in Zam.) is justified by the absence of rhyme, and then the lines are distributed in the individual strophes in the ratio of 6 + 5 + 7. Closer comparison of the third strophe of each of the two principal groups shows that the address of Yahyas in verse 13 has no proper link with what precedes it, and the analogy of verse 30 would lead one to expect here a question of the people to Zakariyya. If one may assume for this reason that a line has dropped out before verse 13, then we obtain the following distribution of units to the two principal groups: Yahya 5 + 4 + 6; 1Isa 6+5+7, and the stanzaic structure is firmly secured by manifold interlocking of responsion elements. The additional strophe verses 35-41 is appended by the ruku` positioning of the Mary episode, as with D. H. Muller. The process is here the same as with the interpolation in verses 45-50 in sura XI. Muller's Abraham strophe (verses 42-51) is bounded by two rukul marks, whereas there is no such mark after verse 58, and, on the other hand, the two strophe verses 52-58 and verses 59-66, which Muller regards as belonging together, are kept apart from each other by a ruku`. The uncertainty here is due not to Muller-even though he stresses (Proph. 1.29) the difficulties obtaining here-but to those considerations which were dominant in distributing the rukul. So much is clear from the notable absence of a rukul after verse 75, where both the division according to content and the change of rhyme suggest that there would be one here. Study of the disposition of the rhymes shows that Muller's division remains in essence secure also for the final section of the sura, prominent by virtue of its novel rhyme-in spite of the badly misplaced ruku, after verse 85. For if we allow for the internal rhymes waladan in verses 91 and 93 and 'abdan 11 in verse 94, all moved to the end of new verses by the division of the verses in Zam., then we obtain three strophes, of which the first (verses 76-83) has eight, the second (verses 84-90) seven, and the third (verses 91-95) eight lines, while verses 96-98 form a special coda to the great symphony and solemnly summarize the promise of eternal bliss for the godfearers, and eternal punishment for unbelievers. The ruku, inserted here between verses 85 and 86 can, as already said, make no difference to this, because it blatantly disturbs the content, and also because verses 84-87 are shown to be closely linked by the intertwinement of the rhymes `izza-didda- 'azza-'adda. Additionally there is the fact that-characteristic of the sense of form documented in the structure of the whole sura-the rhyme termination -zza, which otherwise occurs only in this passage (verses 84 and 86), turns up once again in the final verse of the coda. Whether the distribution of the rukuc in this sura reappears in other recensions of the Koran would have to be determined by comparison, which I am at present unable to make. But even if all rites agreed, this would not make the striking displacement of the two final prostration marks any more acceptable. Both have obviously been moved too far back, and probably belong after verse 58 or, as the case may be, after verse 75. Comparison of the division into stanzas of this sura proposed by Muller (Proph. 1.33) with the one that emerges from the above discussion yields the following configurtion:

First section (verses 1-15). Birth of John 5 + 4 + 5(6) (M. 6 + 5 + 4)

Second section (verses 16-34). Birth of Jesus 6 + 5 + 7 (M. 6 + 6 + 7); addendum (verses 35-41) Polemics against Christianity 7 (M. 7)

Third section (a) (verses 42-58) Various prophets 10 + 7 (= 17); and (b) (verses 59-75). Period without prophets, resurrection 8 + 9 (=17) (M. 10+7+8+9)

Fourth section (verses 76-95). Polemics against those of other faiths, 8 + 7 + 8 and coda (verses 96-98). The reward of faith, punishment of infidelity 3 (M. 8 + 7 + 8).

The comparison shows clearly how surprisingly the results of the two so different methods of observing the data agree.

SURA XXVI

In this sura the ruku, marks fall invariably on MUller's intervals between the strophes, and also, with one single exception (after verse 32) on those that Muller emphasizes with division marks. A section marked off in this manner with the ruku` distribution placed also between verses 32 and 33, which are not separated in this way by Muller, seems justified to me because of the introduction of the Egyptian medicine men in the next section. The part played by the number eight in the line numbering of the Moses legend is striking and was already stressed by Muller. If one eliminates the nonrhyming verse 5912 by combining it with verse 60, one then obtains a regular eight-line stanza instead of the nine-line one. There then remains only the irregularity of the seven-line strophe, verses 33-39, explicable as the result of a line dropping out, as one misses any mention between verses 38 and 39 of the persons speaking in the latter verse. MUller's division gives irregular strophes in the Abraham legend. In spite of what he says (Proph. 1.41), I would place the division of the second from the third strophe after verse 86, where a new theme begins; and I would put verse 96 with the fourth strophe, to which its subject matter is better suited. In this way we obtain four equally long strophes of nine lines each-a number that reappears in the strophes of the following legends of Noah and Had. The story of Salih covers-if one allows for the internal rhyme yufsiduna in verse 152-two equally long strophes of ten lines each, while the legends of Lot and Shucayb return to the regularity of eight lines in each of two strophes-a regularity dominant in the final part of the sura. I would advocate taking the units of five and three lines together-Muller makes them alternate-because of verse 197, which because it does not rhyme must be fused with verse 198, whereas verse 194 divides into two lines after the internal rhyme litakuna. To be sure, a fresh five-line unit could end with verse 195 and the three-line unit begin at verse 196. The subject matter would allow this. Muller makes the final section into a unit of five lines; but with the fusion of verses 227 and 228, justified by the subject matter, since the mention of the Shayatin in verse 221 leads on immediately to verses 224 ff. to the polemics against the poets inspired by him. In fact, no prostration is prescribed at this point. Our analysis, while strikingly confirming Muller's divisions, demonstrates that this sura possesses a far more regular form, one that is completely rounded off, apart from the insignificant aberration the fourth strophe, as the following tabulation makes clear:

That a literary configuration that is so well-proportioned in its form could not have risen by chance is quite obvious.

SURA XXVIII

Muller gives only a brief analysis of this sura, without quoting the text. The rukul in Zam. are distributed in the intervals after verses 12, 20, 28, 42, 50, 60, 75, and 82. I am not attempting any more accurate account, but should like to refer briefly to the third section (Moses' adventure in Midian), the eight lines of which have their rhymes embraced as follows: first and last verse il; second to fifth verse fin, ir, ir, in; sixth and seventh verse in. Miiller's divisions accord approximately with the rukti marks.

SURA XXXVI

Muller's division, established by the responsion, overlaps with the arrangement of the rukuc only insofar as the second ruku, of the sura does in fact fall on the inteval between strophes 1 and 2; here, too, I have no desire to anticipate a closer study of the structure.

SURA XLIV

Here the first of the rukuc noted in Zam. falls in the middle of MUller's strophe 4, while the second, following the sense, comes to stand between strophes 5 and 6. But the position of the first ruku, is hardly tenable, because the legend of Pharaoh's punishment is thereby cut into two in a quite unintelligible way. In this instance, light will come only from comparison of the various recensions.

SURA LI

If we ignore the nine (really eight) verses of the initial invocation that deviate from their rhyme-I discuss them in Gott. Gel. Anz.-then the sura divides first into a fourteen-line proclamation of punishment and reward (verses 10-23), then into a legend section of twenty-three verses in all (verses 24-46), followed by fourteen lines of pointing the moral (verse 47-60). In the legend section fourteen lines are devoted to the birth of Isaac and the judgment on Sodom. There are those Muller discusses in his "Prophets." The remaining nine lines comprise fragments of the other well-known judgment legends, and here the question arises as to what extent the abbreviating is original or attributable to later mutilation. No one can fail to recognize the rhythmic role of the number seven in the other parts. The three rukul that have been entered come after verses 23, 30, and 46 and confirm Muller's division.

SURA LIV

Here, too, the principle on which Muller bases his sectionalization is confirmed by the positioning of the rukuc. For the rest, the sura seems to be in a pretty mutilated condition. (See Proph. 1.54)

SURA LVI

The ruku, after verse 37 is seemingly without proper sense, and placed where it really disturbs the recitation. But it may indicate that at this point something is not right with the text. It is in fact the case that in the preceding section, verses 13 and 14, which clearly form a responsion, stand in a quite different context. From the tafsir literature the sense of these verses is that many of those who were pious before Muhammad was active will belong to the foremost in paradise, and only a few of those who came later, namely, the oldest and most faithful members of his community. These verses thus answer the question: Who really are the sabiquna (foremost)? Verses 38 and 39 must have a similar sense and reference. It is very natural to suspect that originally they also had an analogous position. Accordingly, they would belong between verses 26 and 27 as an answer to the question: ma asha bu 1-yamini? What will be the companions of the Right Hand? That a remark of this kind is not to be expected from "the people of the left hand," the sinners, lies in the nature of things. Of such people there were countless numbers before and after Muhammad's call. But the answer to the relevant question lies in the words of verse 49: 'innd l-'awwalina wa-l-'akharana; Yea, those of old and those of later times. Here, too, we find responsion to the passages just discussed, which gives fresh support to Muller's theory, even if in certain details I sectionalize in a different way. Above all it is significant that in Zam., verse 22 divides after inun, and verse 40 after the first ash-shimali, whereas Muller makes verses 46 and 47 into a single verse. It is important to stress the division of verse 40, because by analogy it leads to dividing verses 8, 9, 10, and 26 in the same way-something justified also by the rhyme dispositions of these units. If we further take cognizance that this latter is valid also for verses 3 and 32, we then obtain for verses 1-56 of the text a series of 63 lines to encompass these into strophic configurations, one must note that: verses 1-7 form an eight-line introductory strophe, in which the first four units have a uniform rhyme and the two middle lines only an assonating one, while the second half comprises three assonating lines and finally a nonrhyming one. Then there follows a transition strophe (verses 8-10) of six lines consisting of identical rhyme pairs. Here the three categories of wretched souls on the day of the Last Judgment are enumerated.

(In verse 10 the interrogative ma has presumably dropped out and must be supplied.) Each one of these three groups is then discussed with reference to the fate awaiting it. Each strophe begins by repeating the question that is put in the transitional strophe. Only the first strophe (verses 11-25) which treats of the group of the "foremost ones" named there in third place, is linked with it, appropriately to the sense, merely with a connecting demonstrative clause. The second strophe (verses 26, 38, 39, 27-37) discusses "the people of the right hand," the third (lines 40-55), "the people of the left." Each of these three principal strophes comprises, if one takes into consideration the features indicated above, sixteen lines. Verse 56 stands quite isolated at the end, giving a resume of the portrayal of Judgment Day, and in my view it refers not merely to the third group but to the whole. The isolated framework verses, which Muller posits for the second and the third main division of the sura, thus finds here, too, in the first part, something corresponding to them. By dividing the strophe in this way the ruku, that Muller places in the middle of the second strophe (after verse 37) comes at its end, and so confirms, if a minor uneveness is eliminated, the correctness of his proposals as a whole. What Muller (Proph. 1.24 ff.) says to justify his proposal that verses 24 and 25 should come after verse 39 is obviated by isolating verse 56 (or is obviated because it implies isolating verse 56). Rather does verse 37 come to a satisfactory and natural conclusion with the words

Li-'asha bi 1-yamini. Its relation to the recapitulation in the final strophe, verses 89 and 90, is thereby disturbed only in respect of a minor detail, and otherwise retains its full force. Miller's sectionalizing of the second main group is so firmly vindicated by the responding components that there can be no doubt about it.

Concerning the third main division, it is above all noteworthy that the isolation of verse 73 is assured by the positioning of the ruku, after it. Zam.'s drawing of verses 91 and 92 together into one, on the basis of their sense (double rhyme at the end of verse occurs again and again in the Koran), would seemingly upset the progression of the number of lines posited by Muller for the strophes of this section. But if one takes verse 95 with the final strophe, which the sense makes perfectly feasible (in that such a conclusion, which strongly reaffirms the recapitulation, also rounds off the strophe's content), then not only is the progression restored, but also the identity of the framing verses 73 and 96 is more forcefully emphasized by the isolation of the latter. And so here, too, we have on a purely formal basis-in spite of some seeming displacement of Muller's presuppositions in individual instances-striking confirmation of his fundamental arguments.

SURA LXIX

The principle operative in Sura LVI, of framing strophes by means of isolated verses, is seen again here in a different form, in that the principal section (verses 4-29) distinguished by its rhyme from the final section of the sura, is framed by two framework elements of three lines each. These vary in their rhyme both from the main section and from the final one, and also from each other, and the length of their lines becomes progressively longer. The principal section, marked out in this way, divides, for its part, into two subsections, the structure and rhyme dispositions of which are clarified by Muller (Proph. 11.49 ff.). Muller puts a line of demarcation between verses 12 and 13, but I think this gives too sharp a division. I also think that the line drawn after verse 32 is misplaced, because it cuts into two the speech of the judgment angel, which all belongs together. It is better transferred to after verse 37, where it coincides with the ruku< marked in Zam. The strophe verses 33-37 thereby still forms part of the principal section, and forms a sort of coda to it, the rhyme of which is continued in the tripartite abgesang13 (the final unit) that follows: If verse 44 is put with verse 45, because there is no rhyme, then the abgesang yields the symmetrical strophic sequence of 5 + 4 + 5 lines that Muller has found in so many instances.

SURA LXXV

Muller's division, so clearly confirmed by the change in rhyme, is further supported by the ruku, after verse 30. The sura thereby divides into a principal section and a two-strophe abgesang. When the internal rhymes are taken into account, the distribution of the lines turns out to be even more regular than it is with Muller. Verse 16 seemingly deviates with its ending from the rhyme pattern, but in fact consists of two halves, rhyming with each other and dividing after the first bihi. In this way the third strophe comes to consist of seven lines, like the second. The fifth strophe hastaking the internal rhyme in verse 29 as-saq/as-saqu into account-six lines. The number of lines in the different strophes is thus, in sequence, 6 + 7 + 7 + 6 + 6 in the aufgesang [the initial sections], and 5 + 5 in the abgesang. Each strophe has its own particular rhyme. Only the third has a more complicated rhyme configuration (a + a, b+b, c+c+c), and the two strophes of the abgesang rhyme identically.

SURA LXXVIII

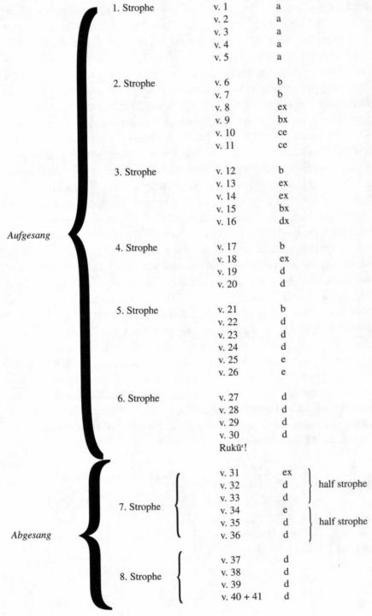

This strophe, too, is divided into an aufgesang and an abgesang by a ruku< after verse 30. While the former discusses God's signs in nature and threatens with the punitive Last Judgment, the latter begins by depicting the joys of paradise and repeats the admonition about the judgment of the world. Each of the two parts divides again into two (unequal) halves: the first after verse 16; the second after verse 36. The line count gives 5 + 6 + 5; 4 + 6 + 4 for the aufgesang; and 6 + 4 (verse 40 does not not rhyme and forms a single line with verse 41, as in Zam.) for the abgesang. The arrangement of the rhymes is noteworthy. The first strophe (verses 1-5) rhymes in an, the remainder of the first half of the principal section in ada, with various assonating deviations, which are nevertheless so ordered that again and again a rhythm is discernible. Thus, in the second strophe (verses 6-11); in each case the first two and last two verses have pure rhymes with each other, while the third assonates more closely with the final ones (aja: ashd), and the fourth more closely with the initial ones (ata: ada). In the third strophe (verses 12-16), ada assonates with ata in the first and fourth verse, the second and third verses rhyme with aja, and the fifth ends with an assonace equally remote from both groups. In the whole of the rest of the sura the rhyme aba is dominant, likewise punctuated with rhythmically ordered assonances, which on the one hand serve as intimations of ada, and on the other as suggesting aja. It is worth stressing that the deviations from the principal rhyme aba are consistently put at the beginning or at the end of the strophes (half-strophe in the abgesang). The fourth strophe (verses 17-20) begins in its first verse with ata followed by the second with aja (assonance with aga).14 The third and fourth verses have aba.The fifth strophe (verses 21-26) has ada, aba, aba, aba, aqa, aqa; the sixth (verses 27-30), aba throughout; the seventh (verses 31-36, beginning of the abgesang) has dza (assonance with aqa), aba, aba, aqa, aba, aba; the eighth (verses 37-41), has aba throughout. If we note that afa in verse 16 sounds closer to aba; there results the following rhymes and strophe scheme for the sura, in which the exponent x designates the assonance with the basis in general, and the exponent e the approach of the basis to the basis e:15

SURA LXXX

Here, too, it is quite apparent that Miiller's ordering of the strophes is confirmed by the rhyme. One needs to add that verse 15 is to be divided off after the internal rhyme safaratinlsafarah, as is the case in Zam. In this way the strophic schema for the first part is improved to 4 + 6 + 6. It is not feasible to terminate verse 18 with the nonrhyming nutfatin. It presumably extends to khalaqahu in verse 19, whereby a rhyme identical with verse 17 is achieved. In the fifth (nine-line) strophe (verses 24-32) it is notable that every third verse departs from the strict rhyme scheme. The framing of this strophe with the verse endings ta'amihi and li 'an'amikum is also of interest. They can be taken as rhyming with each other by analogy with Sura XLVII. The rule according to which the different pronoun suffixes do duty for each other here has yet to be investigated. Whether, on the other hand, verse 33 may be taken as a particular line seems doubtful to me, because it lacks any rhyme. If we put it with verse 34, the strophic scheme of the second part becomes 8 + 9 + 9 (i.e., compared with that of the first part; 2x8+1/2x6+'/2x6).

SURA LXXXII

Muller's divisions, justified by the content and the rhymes, would become even more rounded by dividing verse 12 after the internal rhyme ya'maluna. The sura would then fall into two parts, the first comprising a strophe of five lines, the second consisting of two equally long strophes of seven lines each. It is of no significance that the final verse deviates from the rhyme structure.

The divisions of Suras XC and CXII are quite clear and need no further confirmation.

![]()

I deliberately omit any summary of the observations made in this paper, since many details need further study, with recourse to recensions of the Koran that have not been considered here, and to possible ritual devia Lions. Moreover, as already stated, my illumination of the relevant rhyme patterns are not put forward as definitive. One thing, however, must be stressed; namely, from this study, only two of the seven rukul enumerated above that clash with Muller's proposals concerning divisions-namely, those portioned in the difficult Sura VII after verses 12 and 126-have stood firm (have survived criticism), and therefore serve to refute those proposals decisvely. In all other instances-that is, in fifty out of fiftytwo-Muller is proved right.

From the evidence I have given it does seem to emerge that closer study of the Koran's poetic forms will be able to disclose all manner of not unimportant facts. Above all, I think I have shown how correct the presuppositions are from which Muller proceeded. I myself was for long, if not skeptical, then at any rate indifferent toward his observations. All the more forcefully has the agreement of facts chanced upon, and unknown to Muller himself, with his examples of strophic divisions in the text of the Koran, convinced me that his views are correct. I regard it as fairly certain that in the future, following what has already been established, a whole series of strophe like configurations will be demonstrated going far beyond MUller's own expectations. To be sure, it is equally certain that not all such forms will evince the characteristics of concatenation and responsion that formed MUller's point of departure. But he himself stressed as much in the case of some of the individual texts that he discussed. On the other hand, one thing seems to to me to result irrefutably from my account; namely that the whole science of Koran study is forced to operate on very insecure ground so long as a principal requirement to its apparatus is lacking, that is, a European edition of the Koran that is really scholarly, meeting all the demands of criticism, and containing all relevant historical, philological, religious and liturgical material, set out discursively and with the appropriate comparisons. Without this, all individual research into the Koran must remain disjointed patchwork. This is how I regard my own contributions here, and I publish them only to stimulate further study after the manner of MUller's work, and to demonstrate how unsatisfactory the existing text editions are.

NOTES

1. Karl Vollers, Volkssprache and Schriftsprache im alten Arabien (Strassburg, 1906).

2. [Juz' = One of the thirty portions into which the Koran is divided.]

3. [Theodor Noldeke, Geschichte des Qorans (1860), p. 352. [Geyer obviously could only have been referring to the first edition.]

4. In contrast, there are Juz' sections without ruku`, as, for instance, before Juz' 3, 5, 6, 7, 9, 10, 11, 12, 14, 16, 20, 23. Juz' 21 coincides (according to the division in Zam.) with a ruku` (after Sura XXIX.43), whereas, from Flugel, it would be after verse 44 without R.

Further deviant'Ajza' in Zam.: Juz' 20 after Sura XXVII.56 and Juz' 23 after Sura XXXVI.20.

5. [Geyer does not have (j). I have kept his notation.]

6. ["An answer or reply; a response. Now rare." O.E.D. Cf. "Responsory: A liturgical chant traditionally consisting of a series of versicles and responses, the text usually taken from Scripture. The arrangement was designed for alternate singing of sentences or lines by different people." CODCH.]

7. David H. Muller, Die Propheten in ihrer ursprunglichen Form. Die Grundgesetze der ursemitischen Poesie, erschlossen and nachgewiesen in Bibel, Keilinschriften and Koran and in ihren Wirkungen erkannt in den Choren der griechischen Tragodie, 2 vols. (Vienna, 1896), vol. 1, p. 43 n.

[Other works of Muller on strophic composition include: Strophenbau and Responsion. Neue Beitrage. (5. Jahresbericht der israelisch-theologischen Lehranstalt in Wien 1897/1898) Wien, 1898; "Die Formen der jiidischen Respon- senliteratur and der muhammedanischen Fetwas in den sabaischen Inschriften," WZKM 14 (1900): 171; "Komposition and Strophenbau." Alte and neue Beitrage (Wien 1907).]

8. The different dental sounds rhyme (assonate) with each other in the Koran. Examples in my review of Vollers, R. Geyer, review of Karl Vollers, Volkssprache and Schriftsprache im alten Arabien, Gottinger GelehrterAnzeiger 171 (1909): 10-56.

9. Muller, Die Proheten in ihrer ursprunglichen Form, vol. 1, p. 48.

10. In my frequently mentioned article I assumed that shayban could be included in the rhyme by softening of the b. But closer scrutiny has convinced me that such a development is improbable.

11. On the capacity of fa'la, fi'la, fu'la to rhyme with fa'al, fa 'il, fa`ul, fi`al, fi'il, fa`ul, ful il, fu'al, ful ul, see Vollers, Volkssprache. pp. 97ff.

12. There is nothing notable in the fact that the same verse ending in verse 16 must be counted in, as there is often a nonrhyme at the end of a strophe.

13. [German Aufgesang = the first two sections of ternary strophe; German Abgesang = its concluding part.]

14. In the coinciding of these I discern a sort of anticipatory approach in the pronunciation of the q (Arabic letter, qaf) to the palatization to z effected in the later language. Compare with this what Vollers has to say about the pronunciation of the q (qaf) in the Koran.

15. Concordance of the rhyme types and rhyme syllables:

a = un, im

b = add

bx = ata

ce = asa,asha

d=aba

dx = afa

e=aqa

ex = aja, aza