PRAISE FOR

THE RISE OF THEODORE ROOSEVELT

![]()

“Reading Morris’s comprehensive, necessarily breathless account of Roosevelt’s rise is like riding a cannonball express through the Rockies, the peaks whipping past, one exceeding another in magnificence.”

—MORDECAI RICHLER

“Morris has written a monumental work in every sense of the word.… The result is a book of pulsating and well-written narrative, documented by well over 100 pages of minute, immaculate notes. An average reader will take a long time to read and absorb it all. But read it he will. The tale never lags, like its unique human subject.”

—EDWIN TETLOW, The Christian Science Monitor

“His prose is elegant and at the same time hard and lucid, and his sense of narrative flow is nearly flawless.… The author recreates a sense of the scene and an immediacy of the situation that any skilled writer should envy and the most jaded reader should find a joy.”

—DARDEN A. PYRON, Miami Herald

“It is a big volume, but it is exciting enough to thrill any reader. Morris has an exceptional dexterity with words.… This book will undoubtedly become the standard study of Roosevelt’s rise to power.”

—THOMAS CONWAY, The Boston Sunday Globe

“To his task Morris brings imposing assets.… He is scrupulous in the use of his material and notably fair-minded, … [and] he can tell a very good story.”

—ELTING E. MORISON, The Washington Post Book World

“This highly entertaining, immensely readable book is an extraordinary portrait of a most amazing man, Theodore Roosevelt.… Edmund Morris is scrupulously fair. He is not judgmental; he draws no sweeping conclusions. Sympathetic, amused, and understanding, he is neither adoring nor worshipful.”

—CAREY MCWILLIAMS, Chicago Sun-Times

“Theodore Roosevelt is one of those figures who cannot be fully calibrated without the distance of history and the views of an outsider. This towering biography is the first to answer both requisites.… Orchestrating his material with a certainty and lightness of touch, Morris shuns facile psychohistory and lets Roosevelt’s life build its own edifice.”

—EDWIN WARNER, Time

“If you want a classic Teddy biography, one that hews close to the Theodore Roosevelt of patriotic legend, this entertaining and colorful book is for you.… TR would have enjoyed this version of his life, not only because it’s exciting, particularly the cowboy tales, but because it’s morally correct.… In no other Roosevelt biography do we get a more lively and lifelike picture of the pre-presidential Roosevelt.”

—NICHOLAS VON HOFFMAN, Chicago Tribune

“A huge book, but one that is so full of action that the reader will have difficulty putting it down.… A monumental piece of writing … one of the most interesting biographies to appear in many a moon.”

—JAMES H. JESSE, The Nashville Banner

“The documentation is almost overwhelming and the description of both events and personalities is unusually detailed and complete. Morris reveals the developing personality, the complex and often contradictory character, and the multiplicity of associations of this most ubiquitous of statesmen. His political career, literary activity, life as a rancher and soldier, and personal life are all abundantly covered. This may well become the definitive life.”

—RALPH ADAMS BROWN, Library Journal

“If a novelist were to create a character as multidimensional as Theodore Roosevelt, his credibility would be severely strained. One cannot finish Edmund Morris’s sympathetic study of the 26th President’s early years without feeling that if TR isn’t one of our history’s greatest men, he is surely one of the more fascinating ones.”

—RICHARD SAMUEL WEST, The Philadelphia Inquirer

“Morris has crafted a magnificent biography, carefully researched and gracefully written. He has a keen eye for just the right quotation to enliven an incident or bring a personality to life, and his own sense of humor sparkles through.”

—ALLEN J. SHARE, Louisville Courier-Journal

“Morris faces all the problems and contradictions.… If he were less sympathetic than he is, his treatment of these aspects might make for distortion, but as it is, it only makes for fuller understanding.

“He is also, I must not fail to restate, a magnificent writer. You can read this book with the absorption with which you would read a great novel.… So great is Morris’s skill that the reader follows the story as breathlessly as if he did not already know the outcome.”

—EDWARD WAGENKNECHT, Waltham-Newton News-Tribune

“Readers of this first volume of a biography that takes Roosevelt to his first White House term will get some of the feeling of having received a series of doses of electric voltage.”

—HARRY STEINBERG, Newsday

“This volume leaves us on Sept. 2, 1901. President McKinley has been shot.… America would move into the 20th century with an activist President at its helm, a man who would set the pace of a strong, involved federal government. Morris is now writing that part of the story, and its publication is an event to anticipate eagerly.”

—MAURICE DOLBIER, Providence Sunday Journal

“This irresistible biography is a lot more than a string of dramatic anecdotes. For example, there’s the magnificent prose picture of the disastrous Western winter of 1886–87.… Time and again, Mr. Morris seizes such relatively minor incidents and blows them up to fill the imaginative landscape of his study.…

“What does the total picture of Roosevelt add up to? … Mr. Morris’s refusal to interpret analytically pays rich dividends. We get to see the many contradictory sides of Theodore Roosevelt—the killer of big game and the passionate conservationist; the indefatigable writer of historical potboilers and the scholar who produced the definitive naval history of the War of 1812; the sentimental family man and the tub-thumping advocate of imperialism—the list could go on forever.… For the time being, we can count our curiosity over them among the many reasons for looking forward to the second volume of this wonderfully absorbing biography.”

—CHRISTOPHER LEHMANN-HAUPT, The New York Times

Theodore Rex

![]()

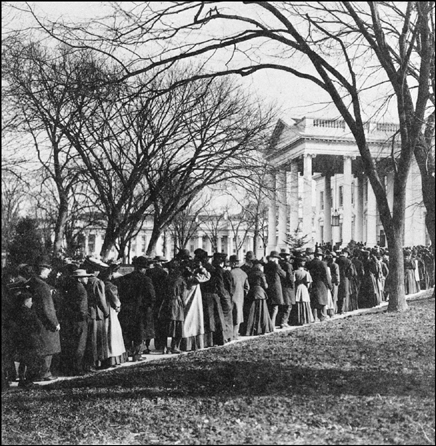

AT ELEVEN O’CLOCK PRECISELY the sound of trumpets echoes within the White House, and floats, through open windows, out into the sunny morning. A shiver of excitement strikes the line of people waiting four abreast outside Theodore Roosevelt’s front gate, and runs in serpentine reflex along Pennsylvania Avenue as far as Seventeenth Street, before whipping south and dissipating itself over half a mile away. The shiver is accompanied by a murmur: “The President’s on his way downstairs.”1

There is some shifting of feet, but no eager pushing forward. The crowd knows that Roosevelt has hundreds of bejeweled and manicured hands to shake privately before he grasps the coarser flesh of the general public. Judging by last year’s reception, the gate will not be unlocked until one o’clock, and even then it will take a good two hours for everybody to pass through. Roosevelt may be the fastest handshaker in history (he averages fifty grips a minute), but he is also the most conscientious, insisting that all citizens who are sober, washed, and free of bodily advertising be permitted to wish the President of the United States a Happy New Year.2

On a day as perfect as this, nobody minds standing in line—with the possible exception of those unfortunates in the blue shadow of the State, War, and Navy Building. Already the temperature is a springlike 55 degrees. It is “Roosevelt weather,” to use a popular phrase.3 Ladies carry bunches of sweet-smelling hyacinths. Gentlemen refresh their thirst at dray-wagons parked against the sidewalk. A reporter, strolling up and down the line, notices that the weather has brought out an unusual number of children, some of whom seem determined to enter the White House on roller skates.4

“All citizens who are sober, washed, and free of bodily advertising.”

Theodore Roosevelt receives the American people on New Year’s Day. (Illustration prl.1)

More music seeps into the still air. This time it is “The Star-Spangled Banner,” played with dignified restraint by the Marine Band. (The President has had occasion to complain, in previous years, of too loud a welcome as he arrives in the vestibule.) After only one strophe, the anthem fades into silence, and another murmur runs down the line: “He’s taking his position in the Blue Room.” Now a German march. “He’s begun to receive the ambassadors.”5

![]()

FOR THE LAST half hour they have been rolling up in their glossy carriages—viscounts, barons, and knights bearing the greetings of emperors and kings to a plain man in a frock coat. A sizable crowd has gathered outside the East Gate to watch them alight under the porte cochère. Their Excellencies teeter down, almost crippled by the weight of full court dress. Plumed helmets wobble precariously, while silver nose-straps tweak at their mustaches. Great bars of medals tangle with their swaying epaulets, gold braid stiffens their trousers, and swords of honor slap against their thigh-length patent-leather boots. Officers of the White House detail, themselves as brilliant as butterflies, hurry across the sunny gravel to assist. Screened through the tall pickets of the White House fence, all this awkward pageantry dissolves into an impressionistic shimmer, and the crowd watches fascinated until the last diplomat has hobbled inside.6

Thousands of other onlookers throng Sixteenth Street and Connecticut Avenue to watch the cavalcade of Washington society converging upon the White House. Justices of the Supreme Court creak by in dignified four-wheelers. Congressional couples display themselves to the electorate in open broughams (necks crane for a glimpse of “Princess Alice” Longworth, the President’s beautiful daughter, in apricot satin and diamonds). A silver-helmeted military attaché steers his own electric runabout. Two energetic little mules haul a mud-spattered bus full of Army ladies.7

Inspired by the balmy weather, many of the President’s guests arrive on foot. Lafayette Square is crowded with elegant young men and women. Naval officers march five abreast, their plumes frothing in unison. Chinese grandees drag heavy silk robes. Grizzled veterans of the Civil War stomp along with tinkling medals, and the crowd parts respectfully before them. The air is full of high-spirited conversation and laughter, while the music pouring out of the White House (a continuous medley, now, of jigs and Joplin rags) creates an irresistible holiday mood. A newspaperman is struck by the happiness he sees everywhere, on this, “the best and fairest day President Roosevelt ever had.”8

![]()

SUCH SUPERLATIVES in praise of the weather are mild in comparison with those being lavished on the state of the union. “On this day of our Lord, January 1, 1907,” the Washington Evening Star reports, “we are the richest people in the world.” The national wealth “has been rolling up at the rate of $4.6 billion per year, $127.3 million per day, $5.5 million per hour, $88,430 per minute, and $1,474 per second” during President Roosevelt’s two Administrations.9 Never have American farmers harvested such tremendous crops; railroads are groaning under the weight of unprecedented payloads; shipyards throb with record construction; the banks are awash with a spring-tide of money. Every one of the forty-five states has enriched itself since the last census, and in per capita terms Washington, D.C., is now “the Richest Spot on Earth.”10

Politically, too, it has been a year of superlatives, many of them supplied, with characteristic immodesty, by the President himself. “No Congress in our time has done more good work,” he fondly told the fifty-ninth, having battered it into submission with the sheer volume of his social legislation.11 He calls its first session “the most substantial” in his experience of public affairs. Joseph G. Cannon, the Speaker of the House, agrees, with one reservation about the President’s methods. “Roosevelt’s all right,” says Cannon, “but he’s got no more use for the Constitution than a tomcat has for a marriage license.”12

“Theodore the Sudden” has been accused of having a similar contempt for international law, ever since the afternoon in 1903 when he allowed a U.S. warship to “monitor” the Panamanian Revolution. If he loses any sleep over his role in that questionable coup d’état, he shows no sign. On the contrary, he glories in the fact that America is now actually building the Panama Canal “after four centuries of conversation”13 by other nations. A few weeks ago he visited the Canal Zone (the first trip abroad by a U.S. President in office), and the colossal excavations there moved him to Shakespearean hyperbole. “It shall be in future enough to say of any man ‘he was connected with digging the Panama Canal’ to confer the patent of nobility on that man,” Roosevelt told his sweating engineers. “From time to time little men will come along to find fault with what you have done … they will go down the stream like bubbles, they will vanish; but the work you have done will remain for the ages.”14

Few, indeed, are the little men who can find fault with the President on this beautiful New Year’s Day, but they are correspondingly shrill. Congressman James Wadsworth, a battered opponent of Roosevelt’s Pure Food Act (which goes into effect today), growls that “the bloody hero of Kettle Hill” is “unreliable, a faker, and a humbug.”15 The editor of the St. Louis Censor, who has never forgiven Roosevelt for inviting a black man to dine in the White House, warns that he is now trying to end segregation of Orientals in San Francisco schools. “Almost every week his Administration has been characterized by some outrageous act of usurpation … he is the most dangerous foe to human liberty that has ever set foot on American soil.”16 Another Southerner, by the name of Woodrow Wilson, is tempted to agree: “He is the most dangerous man of the age.”17 Mark Twain believes that the President is “clearly insane … and insanest upon war and its supreme glories.”18

Roosevelt is used to such criticism. He has been hearing it all his life. “If a man has a very decided character, has a strongly accentuated career, it is normally the case of course that he makes ardent friends and bitter enemies.”19 Yet even impartial observers will admit there is a grain of truth in Twain’s assertions. The President certainly has an irrational love of battle. He ceaselessly praises the joys of righteous killing, most recently in his annual message to Congress: “A just war is in the long run far better for a man’s soul than the most prosperous peace.”

Yet the fact about this most pugnacious of Presidents is that his two terms in office have been almost completely tranquil. (If he had not inherited an insurrection in the Philippines from William McKinley, he could absolve himself of any military deaths.) He is currently being hailed around the world as a flawless diplomat, and the man who has done more to advance the cause of peace than any other. If all Eastern Asia—and for that matter most of Western Europe—is not embroiled in conflict, it is largely due to peace settlements delicately mediated by Theodore Roosevelt. At the same time he has managed, without so much as firing one American pistol, to elevate his country to the giddy heights of world power.20

He never tires of reminding people that his famous aphorism “Speak Softly and Carry a Big Stick” proceeds according to civilized priorities. Persuasion should come before force. In any case it is the availability of raw power, not the use of it, that makes for effective diplomacy. Last summer’s rebellion in Cuba, which left the island leaderless, provided Roosevelt with a textbook example. Acting as usual with lightning swiftness, he invoked an almost forgotten security agreement and proclaimed a U.S.-backed provisional government within twenty-four hours of the collapse of the old. While Secretary of War William H. Taft worked “to restore order and peace and public confidence,” American warships steamed thoughtfully up and down the Cuban coastline. The rebels disbanded, Taft returned to Washington, and the big white ships followed. Cuba is now assured of regaining her independence, and the Big Stick has been laid down unbloodied.21

Roosevelt hopes the episode will put to an end, once and for all, rumors that he is still at heart an expansionist. “I have about as much desire to annex more islands,” he declares, “as a boa-constrictor has to swallow a porcupine wrong end to.”22

![]()

TWO OR THREE political clouds, perhaps, mar the perfect blue of Theodore Roosevelt’s New Year. Japan is not convinced that his efforts to end discrimination against her citizens in California are sincere, and there are veiled threats of war; “but,” as yesterday’s Washington Star noted confidently, “President Roosevelt thinks he can settle them.” The stock market, despite the booming economy, seems paralyzed. Wall Street billionaires are predicting that Roosevelt-style railroad rate regulation will sooner or later bring about financial catastrophe. And there is an ominous paucity of blacks on line today—only fourteen, by one count—indicating that race resentment is growing against his dishonorable discharge of three companies of colored soldiers for an unproved riot in Brownsville, Texas.23

As yet, these clouds do not loom very large. Roosevelt is free to enjoy the sensation of near-total control over “the mightiest republic on which the sun ever shone,”—his own phrase, much repeated.24 Youngest and most vigorous man ever to enter the White House, he exults in what today’s New York Tribune calls “an opulent efficiency of mind and body.” He loves power, loves publicity for the added power it brings, and so far at least seems to have disproved the Actonian theory of corruption. Curiously, the more power Roosevelt acquires, the calmer and sweeter he becomes, and the more willing to step down in two years’ time, although a third term is his for the asking. Until then he intends to exercise to the full his constitutional rights to cleave continents, place struggling poets on the federal payroll, and treat with crowned heads on terms of complete equality. Henry Adams calls him “the best herder of Emperors since Napoleon.”25 Expert opinion rates his influence over Congress as greater than that of Kaiser Wilhelm II over the Reichstag.26 He commands a twenty-four-seat majority in the Senate, a hundred-seat majority in the House, and the frank adoration of the American public. A cornucopia of gifts pours daily into the White House mail-room: hams shaped to match the Rooseveltian profile, crates of live coons, Indian skin paintings, snakes from a traveling sideshow, chairs, badges, vases, and enough Big Sticks to dam the Potomac. One million “Teddy” bears are on sale in New York department stores. Countless small boys, including a frail youngster named Gene Tunney, are doing chest exercises in the hope of emulating their hero’s physique. David Robinson, a bootblack from Lackawanna County, Pennsylvania, has just arrived in Washington, bearing letters of recommendation from judges and members of Congress, and begs the privilege of shining the President’s shoes for nothing.27

Nor is Roosevelt-worship confined to the United States. In England, King Edward VII and ex-Prime Minister Balfour consider him to be “the greatest moral force of the age.”28 Serious British journals rank him on the same level as Washington and Lincoln. Even the august London Times, in a review of his latest “very remarkable” message to Congress, admits “It is hard not to covet such a force in public life as our American cousins have got in Mr. ROOSEVELT.”29

All over the world Jews revere him for his efforts to halt the persecution of their co-religionists in Russia and Rumania, and for making Oscar Solomon Straus Secretary of Commerce and Labor, the first Jewish Cabinet officer in American history.30 France’s Ambassador to the United States, Jules Jusserand, says publicly that “President Roosevelt is the greatest man in the Western Hemisphere—head and shoulders above everyone else.”31

And from Christiania, Norway, comes the ultimate accolade: an announcement that Theodore Roosevelt, world peacemaker, has become the first American to win the Nobel Prize.32

![]()

TWELVE-THIRTY HAS COME and gone, but the White House gates are still firmly shut. He must have shaken at least a thousand hands already.… Fob watches flash in the sun as students of Washington protocol calculate how long it will take him to work his way down through the social strata. Twenty minutes are generally enough for all the ambassadors, ministers, secretaries, and chargés d’affaires, assuming that each flatters the President for no longer than thirty seconds; ten minutes for the Supreme Court Justices and other members of the judiciary; a quarter of an hour for Senators, Representatives, and Delegates in Congress (he’ll probably spend a minute or two talking to old Chaplain Edward Everett Hale, who hasn’t missed a reception in sixty-two years); a good half-hour, knowing Roosevelt’s priorities, for officers of the Navy and Army; then five minutes apiece for the Smithsonian Institution, the Civil Service, and the Attorney General’s office … which means the Grand Army of the Republic should be going through about now. Last in the order of official precedence will be veterans of the Spanish-American War, including the inevitable Rough Riders, some of whom are very rough indeed. One of today’s newspapers complains about the President’s habit of inviting “thugs and assassins of Idaho and Montana to be his guests in the White House.”33 But Roosevelt has never been able to turn away the friends of his youth. After assuming the Presidency he sent out word that “the cowboy bunch can come in whenever they want to.” When a doorkeeper mistakenly refused admission to one leathery customer, the President was indignant. “The next time they don’t let you in, Sylvane, you just shoot through the windows.”34

Twelve fifty-five. A stir at the head of the line. Bonnets are adjusted, with much bobbing of artificial fruit; ties are straightened, vests brushed free of popcorn. The gates swing open, and two bowler-hatted policemen lead the way down the White House drive. As the crowd approaches the portico, nine-year-old Quentin Roosevelt waves an affable greeting from his upstairs window. The officers eye him sternly: Young “Q” has a habit of dropping projectiles on men in uniform, including one gigantic, cop-flattening snowball that narrowly missed his father.35

The music grows louder as the public steps into the brilliantly lit vestibule. Sixty scarlet-coated bandsmen, hedged around with holly and poinsettia, maintain a brisk, incessant rhythm: Roosevelt knows that this makes his callers unconsciously move faster. Ushers jerk white-gloved thumbs in the direction of the Red Room. “Step lively now!”36

Shuffling obediently through shining pillars, past stone urns banked with Christmas-flowering plants, the crowd has a chance to admire Mrs. Roosevelt’s interior restorations, begun in 1902 and only recently completed.37 (One of her husband’s first acts, as President, had been to ask Congress to purge the Executive Mansion of Victorian bric-a-brac and restore it to its original “stately simplicity.”) These changes come as a shock to older people in line who remember the cozy, shabby, half-house, half–office building of yesteryear, with its dropsical sofas and brass spittoons. Now all is spaciousness and austerity. Regal red furnishings accentuate the gleaming coldness of stone halls and stairways. Roman bronze torches glow with newfangled electric light. The traditional floral displays, which used to make nineteenth-century receptions look like horticultural exhibitions, have been drastically reduced. Rare palms tower in wall niches; vases of violets and American Beauty roses perfume the air.38

Here the Roosevelts live in a style which, to their critics, seems “almost more than royal dignity.”39 Formality unknown since the days of George Washington governs the conduct of the First Family. Even the President’s sisters have to make appointments to see him. During the official diplomatic season, beginning today, the White House will be the scene of banquets and receptions of an almost European splendor. (The President spends his entire $50,000 salary on entertaining.)40 Roosevelt’s practice, on such occasions, of making dramatic entrances at the stroke of the appointed hour, offering his arm to the lady who will sit at his right, looks like imperial pomp to some. “The President,” says Henry James, “is distinctly tending—or trying—to make a court.”41

Roosevelt himself scoffs cheerfully at such gibes. “They even say I want to be a prince myself! Not I! I’ve seen too many of them!”42 He is merely performing, with meticulous correctness, the duties of a head of state. Within the confines of protocol he remains the most democratic of men. He refuses to use obsequious forms of address when writing to foreign rulers, preferring the informal second person, as a gentleman among gentlemen. Nor is he impressed when they address him as “Your Excellency” in return. “They might just as well call me His Transparency for all I care.”43

Yet some citizens are bent on killing this “first of American Caesars.” Last year a man walked into the President’s office with a needle-sharp blade up his sleeve. Ever since then, White House security has been tight.44 Uniformed aides confiscate bundles, inspect hats, draw pocketed hands into open view. All along the corridor, Secret Service men stand like statues. Only their eyes flicker: by the time a caller reaches the Blue Room, he has been scrutinized from head to foot at least three times. Roosevelt does not want to leave office a day too soon.

“I enjoy being President,” he says simply.45

![]()

NO CHIEF EXECUTIVE has ever had so much fun. One of Roosevelt’s favorite expressions is “dee-lighted”—he uses it so often, and with such grinning emphasis, that nobody doubts his sincerity. He indeed delights in every aspect of his job: in plowing through mountains of state documents, memorizing whole chunks and leaving his desk bare of even a card by lunchtime; in matching wits with the historians, zoologists, inventors, linguists, explorers, sociologists, actors, and statesmen who daily crowd his table; in bombarding Congress with book-length messages (his latest, a report on his trip to Panama, uses the novel technique of illustrated presentation); in setting aside millions of acres of unspoiled land at the stroke of a pen; in appointing struggling literati to jobs in the U.S. Treasury, on the tacit understanding they are to stay away from the office; in being, as one of his children humorously put it, “the bride at every wedding, and the corpse at every funeral.”46

He takes an almost mechanistic delight in the smooth workings of political power. “It is fine to feel one’s hand guiding great machinery.”47 Ex-President Grover Cleveland, himself a man of legendary ability, calls Theodore Roosevelt “the most perfectly equipped and most effective politician thus far seen in the Presidency.”48 Coming from a Democrat and longtime Roosevelt-watcher, this praise shows admiration of one virtuoso for another.

With his clicking efficiency and inhuman energy, the President seems not unlike a piece of engineering himself. Many observers are reminded of a high-speed locomotive. “I never knew a man with such a head of steam on,” says William Sturgis Bigelow. “He never stops running, even while he stokes and fires,” another acquaintance marvels, adding that Roosevelt presents “a dazzling, even appalling, spectacle of a human engine driven at full speed—the signals all properly set beforehand (and if they aren’t, never mind!).” Henry James describes the engine as “destined to be overstrained perhaps, but not as yet, truly, betraying the least creak … it functions astonishingly, and is quite exciting to see.”49

At the moment, Roosevelt can only be heard, since the first wave of handshakers, filing through the Red Room into the Blue, obscures him from view. He is in particularly good humor today, laughing heartily and often, in a high, hoarse voice that floats over the sound of the band.50 It is an irresistible laugh: an eruption of mirth, rising gradually to falsetto chuckles, that convulses everybody around him. “You don’t smile with Mr. Roosevelt,” writes one reporter, “you shout with laughter with him, and then you shout again while he tries to cork up more laugh, and sputters, ‘Come, gentlemen, let us be serious. This is most unbecoming.’ ”51

Besides being receptive to humor, the President produces plenty of it himself. As a raconteur, especially when telling stories of his days among the cowboys, he is inimitable, making his audiences laugh until they cry and ache. “You couldn’t pick a hallful,” declares the cartoonist Homer Davenport, “that could sit with faces straight through his story of the blue roan cow.”52 Physically, too, he is funny—never more so than when indulging his passion for eccentric exercise. Senator Henry Cabot Lodge has been heard yelling irritably at a portly object swaying in the sky, “Theodore! if you knew how ridiculous you look on top of that tree, you would come down at once.”53 On winter evenings in Rock Creek Park, strollers may observe the President of the United States wading pale and naked into the ice-clogged stream, followed by shivering members of his Cabinet.54 Thumping noises in the White House library indicate that Roosevelt is being thrown around the room by a Japanese wrestler; a particularly seismic crash, which makes the entire mansion tremble, signifies that Secretary Taft has been forced to join in the fun.55

Mark Twain is not alone in thinking the President insane. Tales of Roosevelt’s unpredictable behavior are legion, although there is usually an explanation. Once, for instance, he hailed a hansom cab on Pennsylvania Avenue, seized the horse, and mimed a knife attack upon it. On another occasion he startled the occupants of a trolley-car by making hideous faces at them from the Presidential carriage. It transpires that in the former case he was demonstrating to a companion the correct way to stab a wolf; in the latter he was merely returning the grimaces of some small boys, one of whom was the ubiquitous Quentin.56

Roosevelt can never resist children. Even now, he is holding up the line as he rumples the hair of a small boy with skates and a red sweater. “You must always remember,” says his English friend Cecil Spring Rice, “that the President is about six.”57 Mrs. Roosevelt has let it be known that she considers him one of her own brood, to be disciplined accordingly. Between meetings he loves to sneak upstairs to the attic, headquarters of Quentin’s “White House Gang,” and thunder up and down in pursuit of squealing boys. These romps leave him so disheveled he has to change his shirt before returning to his duties.58

A very elegant old lady moves through the door of the Blue Room and curtsies before the President. He responds with a deep bow whose grace impresses observers.59 Americans tend to forget that Roosevelt comes from the first circle of the New York aristocracy; the manners of Gramercy Park, Harvard, and the great houses of Europe flow naturally out of him. During the Portsmouth Peace Conference in 1905, he handled Russian counts and Japanese barons with such delicacy that neither side was able to claim preference. “The man who had been represented to us as impetuous to the point of rudeness,” wrote one participant, “displayed a gentleness, a kindness, and a tactfulness that only a truly great man can command.”60

Roosevelt’s courtesy is not extended only to the well-born. The President of the United States leaps automatically from his chair when any woman enters the room, even if she is the governess of his children. Introduced to a party of people who ignore their own chauffeur, he protests: “I have not met this gentleman.” He has never been able to get used to the fact that White House stewards serve him ahead of the ladies at his table, but accepts it as necessary protocol.61

For all his off-duty clowning, Roosevelt believes in the dignity of the Presidency. As head of state, he considers himself the equal, and on occasion the superior, of the scepter-bearers of Europe. “No person living,” he curtly informed the German Ambassador, “precedes the President of the United States in the White House.” He is quick to freeze anybody who presumes to be too familiar. Although he is resigned to being popularly known as “Teddy,” it is a mistake to call him that to his face. He regards it as an “outrageous impertinence.”62

![]()

CORDS OF OLD GOLD velvet channel the crowd into single file at the entrance to the Blue Room. Since the President stands just inside the door, on the right, there is little time to admire the oval chamber, with its silk-hung walls and banks of white roses; nor the beauty of the women invited “behind the line”—a signal mark of Presidential favor—and who now form a rustling backdrop of chiffon and lace and satin, their pearls aglow in the light of three sunny windows.63 Roosevelt is shaking hands at top speed, so the observer has only two or three seconds to size him up.

![]()

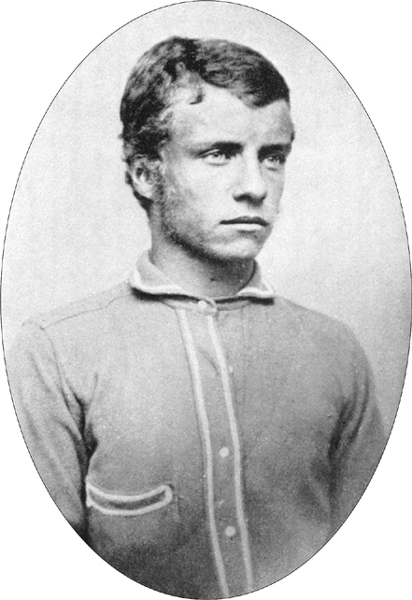

A FEW SECONDS, surprisingly, are enough. Theodore Roosevelt is a man of such overwhelming physical impact that he stamps himself immediately on the consciousness. “Do you know the two most wonderful things I have seen in your country?” says the English statesman John Morley. “Niagara Falls and the President of the United States, both great wonders of nature!”64 Their common quality, which photographs and paintings fail to capture, is a perpetual flow of torrential energy, a sense of motion even in stillness.65Both are physically thrilling to be near.

Although Theodore Roosevelt stands three inches short of six feet, he seems palpably massive.66 Two hundred pounds of muscle—those who think it fat have not yet been bruised by contact with it—thicken his small-boned frame. (The only indications of the latter are tapered hands and absurdly small shoes.) A walrus-like belt of muscle strains against his stiff collar. Muscles push through the sleeves of his gray frock coat and the thighs of his striped trousers. Most muscular of all, however, is the famous chest, which small boys, on less formal occasions, are invited to pummel. Members of the White House Gang admit to “queer sensations” at the sight of this great barrel bearing down upon them, and half expect it to burst out of the Presidential shirt. Roosevelt has spent many thousands of hours punishing a variety of steel springs and gymnastic equipment, yet his is not the decorative brawn of a mere bodybuilder. Professional boxers testify that the President is a born fighter who repays their more ferocious blows with interest. “Theodore Roosevelt,” says his heavyweight sparring partner, “is a strong, tough man; hard to hurt and harder to stop.”67

The nerves that link all this mass of muscle are abnormally active. Roosevelt is not a twitcher—in moments of repose he is almost cataleptically still—but when talking his entire body mimes the rapidity of his thoughts. The right hand shoots out, bunches into a fist, and smacks into the left palm; the heels click together, the neck bulls forward, then, in a spasm of amusement, his face contorts, his head tosses back, spectacle-ribbons flying, and he shakes from head to foot with laughter. A moment later, he is listening with passionate concentration, crouching forward and massaging the speaker’s shoulder as if to wring more information out of him. Should he hear something not to his liking, he recoils as if stung, and the blood rushes to his face.68

Were it not for his high brow, and the distracting brilliance of his smile, Roosevelt would unquestionably be an ugly man. His head is too big and square (one learned commentator calls it brachycephalous),69 his ears too small, his jowls too heavy. The stiff brown hair is parted high and clipped unflatteringly short. Rimless pince-nez squeeze the thick nose, etching a tiny, perpetual frown between his eyebrows. The eyes themselves are large, wide-spaced, and very pale blue. Although Roosevelt’s gaze is steady, the constant movement of his head keeps slicing the pince-nez across it, in a series of twinkling eclipses that make his true expression very hard to gauge. Only those who know him well are quick enough to catch the subtler messages Roosevelt sends forth. William Allen White occasionally sees “the shadow of some inner femininity deeply suppressed.”70 Owen Wister has detected (and Adolfo Muller-Ury painted) a sort of blurry wistfulness, a mixture of “perplexity and pain … the sign of frequent conflict between what he knew, and his wish not to know it, his determination to grasp his optimism tight, lest it escape him.”71

His ample mustache does not entirely conceal a large, pouting underlip, on the rare occasions when that lip is still. Mostly, however, the mustache gyrates about Roosevelt’s most celebrated feature—his dazzling teeth. Virtually every published description of the President, including those of provincial reporters who can catch only a quick glimpse of him through the window of a campaign train, celebrates his dental display. Cartoonists across the land have sketched them into American folk-consciousness, so much so that envelopes ornamented only with teeth and spectacles are routinely delivered to the White House.72

At first sight the famous incisors are, perhaps, disappointing, being neither so big nor so prominent as the cartoonists would make out. But to watch Roosevelt talking is to be hypnotized by them. White and even, they chop every word into neat syllables, sending them forth perfectly formed but separate, in a jerky staccatissimo that has no relation to the normal rhythms of speech. The President’s diction is indeed so syncopated, and accompanied by such surprise thrusts of the head, that there are rumors of a youthful impediment, successfully conquered.73 His very voice seems to rasp out of the tips of his teeth. “I always think of a man biting tenpenny nails when I think of Roosevelt making a speech,” says an old colleague.74 Others are reminded of engines and light artillery. Sibilants hiss out like escaping steam; plosives drive the lips apart with an audible pfft.75

Hearing him close up, one can understand his constant use of “dee-lighted.” Phonetically, the word is made for him, with its grinning vowels and snapped-off consonants. So, too, is that other staple of the Rooseveltian vocabulary, “I.” He pronounces it“Aieeeee,” allowing the final e’s to rise to a self-satisfied pitch which never fails to irritate Henry Adams.76

The force of Roosevelt’s utterance has the effect of burying his remarks, like shrapnel, in the memory of the listener. Years after meeting him, an Ohio farmer will lovingly recall every inflection of some such banality as “Are you German? Congratulations—I’m German too!” (His ability to find common strains of ancestry with voters has earned him the nickname of “Old Fifty-seven Varieties.”)77 Children are struck by the tenderness with which he enunciates his wife’s name—“Edith.”78 H. G. Wells preserves, as if filmed and recorded, an interview with the President in the White House garden last summer. “I can see him now, and hear his unmusical voice saying, ‘the effort’s worth it, the effort’s worth it,’ and see the … how can I describe it? The friendly peering snarl of his face, like a man with sun in his eyes.”79

The British author declares, in a Harper’s Weekly article, that Roosevelt is as impressive mentally as physically. “His range of reading is amazing. He seems to be echoing with all the thought of the time, he has receptivity to the pitch of genius.”80 Opinions are divided as to whether the President possesses the other aspect of genius, originality. His habit of inviting every eminent man within reach to his table, then plunging into the depths of that man’s specialty (for Roosevelt has no small talk), exposes but one facet of his mind at a time, to the distress of some finely tuned intellects. The medievalist Adams finds his lectures on history childlike and superficial; painters and musicians sense that his artistic judgment is coarse.81

Yet the vast majority of his interlocutors would agree with Wells that Theodore Roosevelt has “the most vigorous brain in a conspicuously responsible position in all the world.”82 Its variety is protean. A few weeks ago, when the British Embassy’s new councillor, Sir Esmé Howard, mentioned a spell of diplomatic duty in Crete, Roosevelt immediately and learnedly began to discuss the archeological digs at Knossos. He then asked if Howard was by any chance descended from “Belted Will” of Border fame—quoting Scott on the subject, to the councillor’s mystification.83 The President is also capable of declaiming German poetry to Lutheran preachers, and comparing recently resuscitated Gaelic letters with Hopi Indian lyrics. He is recognized as the world authority on big American game mammals, and is an ornithologist of some note. Stooping to pick a speck of brown fluff off the White House lawn, he will murmur, “Very early for a fox sparrow!”84 Roosevelt is equally at home with experts in naval strategy, forestry, Greek drama, cowpunching, metaphysics, protective coloration, and football techniques. His good friend Mrs. Henry Cabot Lodge cherishes the following Presidential document, dated 11 March 1906:

Dear Nannie Can you have me to dinner either Wednesday or Friday? Would you be willing to have Bay and Bessie also? Then we could discuss the Hittite empire, the Pithecanthropus, and Magyar love songs, and the exact relations of the Atli of the Volsunga Saga to the Etzel of the Nibelungenlied, and of both to Attila—with interludes by Cabot about the rate bill, Beveridge, and other matters of more vivid contemporary interest. Ever yours,

THEODORE ROOSEVELT85

There is self-mockery in this letter, but nobody doubts that Roosevelt could (and probably did) hold forth on such subjects in a single evening. He delights like a schoolboy in parading his knowledge, and does so so loudly, and at such length, that less vigorous talkers lapse into weary silence. John Hay once calculated that in a two-hour dinner at the White House, Roosevelt’s guests were responsible for only four and a half minutes of conversation; the rest was supplied by the President himself.86

He is, fortunately, a superb talker, with a gift for le mot juste that stings and sizzles. Although he hardly ever swears—his intolerance of bad language verges on the prissy—he can pack such venom into a word like “swine” that it has the force of an obscenity, making his victim feel more swinish than a styful of hogs.87 Roosevelt has a particular gift for humorous invective. Old-timers still talk about the New York Supreme Court Justice he pilloried as “an amiable old fuzzy-wuzzy with sweetbread brains.” Critics of the Administration’s Panama policy are “a small bunch of shrill eunuchs”; demonstrators against bloodsports are “logical vegetarians of the flabbiest Hindoo type.” President Castro of Venezuela is “an unspeakably villainous little monkey,” President Marroquín of Colombia is a “pithecanthropoid,” and Senator William Alfred Peffer is immortalized as “a well-meaning, pin-headed, anarchistic crank, of hirsute and slabsided aspect.”88 When delivering himself of such insults, the President grimaces with glee. Booth Tarkington detects “an undertone of Homeric chuckling.”89

Theodore Roosevelt is now only one handshake away. His famous “presence” charges the air about him. It is, in the opinion of one veteran politician, “unquestionably the greatest gift of personal magnetism ever possessed by an American.”90 Other writers grope for metaphors ranging from effervescence to electricity. “One despairs,” says William Bayard Hale, “of giving a conception of the constancy and force of the stream of corpuscular personality given off by the President … It begins to play on the visitor’s mind, his body, to accelerate his blood-current, and set his nerves tingling and his skin aglow.”91

The word “tingle” appears again and again in descriptions of encounters with Roosevelt. He has, as Secretary Straus observes, “the quality of vitalizing things,”92 and some people take an almost sensual pleasure in his proximity. Today, the President radiates even more health and vigor than usual—he has spent the last five days pounding through wet Virginia forests in search of turkey. His stiff hair shines, his complexion is a ruddy brown, his body exudes a clean scent of cologne.93

He stands with tiny feet spraddled, shoulders thrown back, chest and stomach crescent as a peacock, his left thumb comfortably hooked into a vest pocket. For what must be the three thousandth time, his right arm shoots out. “Dee-lighted!” Unlike his predecessors, Theodore Roosevelt does not limply allow himself to be shaken. He seizes on the fingers of every guest, and wrings them with surprising power. “It’s a very full and very firm grip,” warns one newspaper, “that might bring a woman to her knees if she wore her rings on her right hand.”94 The grip is accompanied by a discreet, but irresistible sideways pull, for the President, when he lets go, wishes to have his guest already well out of the way.95 Yet this lightning moment of contact is enough for him to transmit the full voltage of his charm.

Insofar as charm can be analyzed, Roosevelt’s owes its potency to a combination of genuine warmth and the self-confidence of a man who, in all his forty-eight years, has never encountered a character stronger than his own—with the exception of one revered person, with the same name as himself.

Women find the President enchanting. “I do delight in him,” says Edith Wharton. The memory of every Rooseveltian encounter glows within her “like a tiny morsel of radium.”96 Another woman writes of meeting him at a reception: “The world seemed blotted out. I seemed to be enveloped in an atmosphere of warmth and kindly consideration. I felt that, for the time being, I was the sole object of his interest and concern.”97 If he senses any sexual interest in him, Theodore Roosevelt shows no sign: in matters of morality he is as prudish as a dowager. That small hard hand has caressed only two women. One of them stands beside him now, and the other, long dead, is never mentioned.

Men, too, feel the power of his charm. Even the bitterest of his political enemies will allow that he is “as sweet a man as ever scuttled a ship or cut a throat.”98 Senator John Spooner stormed into his office the other day “angry as a hornet” over Brownsville, and emerged “liking him again in spite of myself.” Henry James, who privately considers Roosevelt to be “a dangerous and ominous jingo,” is forced to recognize “his amusing likeability.”99

His friends are frank in their adoration. “Theodore is one of the most lovable as well as one of the cleverest and most daring men I have ever known,” says Henry Cabot Lodge, not normally given to hyperbole. Crusty John Muir “fairly fell in love” with the President when he visited Yosemite, and Jacob Riis claims the years he spent with Roosevelt were the happiest of his life.100

Yet, for all the warmth of the handshake, and the squeaking sincerity of the “Dee-lighted!” there is something automatic about that gray-blue gaze. One almost hears the whir of a shutter. “While talking,” notes the Philadelphia Independent, “the camera of his mind is busy taking photographs.”101 If Roosevelt senses the presence of somebody who is likely to be of use to him, either politically or socially, he will instantly file the photograph, and with half a dozen sentences ensure that his guest, in turn, never forgets him. Ten years later is not too long a time for Roosevelt to call upon that man, in the sure knowledge that he has a friend.102

Theodore Roosevelt’s memory can, in the opinion of the historian George Otto Trevelyan, be compared with the legendary mechanism of Thomas Babington Macaulay.103 Authors are embarrassed, during Presidential audiences, to hear long quotes from their works which they themselves have forgotten. Congressmen know that it is useless to contest him on facts and figures. He astonishes the diplomat Count Albert Apponyi by reciting, almost verbatim, a long piece of Hungarian historical literature: when the Count expresses surprise, Roosevelt says he has neither seen nor thought of the document in twenty years. Asked to explain a similar performance before a delegation of Chinese, Roosevelt explains mildly: “I remembered a book that I had read some time ago, and as I talked the pages of the book came before my eyes.”104 The pages of his speeches similarly swim before him, although he seems to be speaking impromptu. When confronted with a face he does not instantly recall, he will put a hand over his eyes until it appears before him in its previous context.105

The small hard hand relaxes its grip, and the line moves on. Guests barely have time to greet the First Lady, who stands aloof and smiling in brown brocaded satin at her husband’s elbow. She holds a bouquet of white roses, effectively discouraging handshakes. The White House’s most brilliant entertainer since Dolley Madison, Edith Kermit Roosevelt is also its most puzzlingly private. Nobody knows what power she wields over the President, but rumor says it is considerable, particularly in the field of appointments. For all his political cunning, Roosevelt is not an infallible judge of men.106

“More lively please!” an usher calls at the door of the Green Room. The velvet ropes lead on through the East Room, down a curving stairway, then out into the sunshine.107 The crowd disperses with the dazed expressions of a theater audience. There are some perfunctory remarks about the diplomatic display, but mostly the talk is about the man in the Blue Room. “You go to the White House,” writes Richard Washburn Child, “you shake hands with Roosevelt and hear him talk—and then you go home to wring the personality out of your clothes.”108

![]()

THE PRESIDENT CONTINUES to pump hands with such vigor that his last caller passes through the Blue Room shortly after two o’clock. Mrs. Roosevelt, and most of the receiving party, have long since excused themselves for lunch. Considering the exercise to which he has been put, Roosevelt is doubtless hungry too; yet even now he cannot rest. Wheeling in search of more victims, he grabs the hands of Agriculture Secretary James Wilson, who has stayed behind to keep him company. “Mr. Secretary,” croaks Roosevelt, “to you I wish a very, very happy New Year!”109 The fact that he has done so once already does not seem to occur to him. Still unsatisfied, the President proceeds to shake the hands of every aide, usher, and policeman in sight. Only then does he retire upstairs and scrub himself clean.110

Events which he cannot foresee will reduce the total of his callers next year. Never again will Theodore Roosevelt, or any other President, enjoy such homage. The journalists may add another superlative to their praises. On this first day of January 1907, the President has shaken 8,150 hands, more than any other man in history. As a world record, it will remain unbroken almost a century hence.111

![]()

LATER IN THE AFTERNOON, the President, his wife, and five of his six children are seen cantering off for a ride in the country. Although reporters cannot follow him through the rest of the day, enough is known of Roosevelt’s domestic habits to predict its events with some accuracy.112 Returning for tea, which he will swig from an outsize cup, Roosevelt will take advantage of the holiday quietness of his dark-green office to do some writing. Besides being President of the United States, he is also a professional author. The Elkhorn Edition of The Works of Theodore Roosevelt, just published, comprises twenty-three volumes of history, natural history, biography, political philosophy, and essays. At least two of his books, The Naval War of 1812 and the four-volume Winning of the West, are considered definitive by serious historians.113 He is also the author of many scientific articles and literary reviews, not to mention an estimated total of fifty thousand letters—the latest twenty-five of which he dashed off this morning.114

In the early evening the President will escort his family to No. 1733 N Street, where his elder sister Bamie will serve chocolate and whipped cream and champagne. After returning to the White House, the younger Roosevelts will be forcibly romped into bed, and the elder given permission to roller-skate for an hour in the basement. As quietness settles down over the Presidential apartments, Roosevelt and his wife will sit by the fire in the Prince of Wales Room and read to each other. At about ten o’clock the First Lady will rise and kiss her husband good night. He will continue to read in the light of a student lamp, peering through his one good eye (the other is almost blind) at the book held inches from his nose, flicking over the pages at a rate of two or three a minute.115

This is the time of the day he loves best. “Reading with me is a disease.”116 He succumbs to it so totally—on the heaving deck of the Presidential yacht in the middle of a cyclone, between whistle-stops on a campaign trip, even while waiting for his carriage at the front door—that he cannot hear his own name being spoken. Nothing short of a thump on the back will regain his attention. Asked to summarize the book he has been leafing through with such apparent haste, he will do so in minute detail, often quoting the actual text.117

The President manages to get through at least one book a day even when he is busy. Owen Wister has lent him a book shortly before a full evening’s entertainment at the White House, and been astonished to hear a complete review of it over breakfast. “Somewhere between six one evening and eight-thirty next morning, beside his dressing and his dinner and his guests and his sleep, he had read a volume of three-hundred-and-odd pages, and missed nothing of significance that it contained.”118

On evenings like this, when he has no official entertaining to do, Roosevelt will read two or three books entire.119 His appetite for titles is omnivorous and insatiable, ranging from the the Histories of Thucydides to the Tales of Uncle Remus. Reading, as he has explained to Trevelyan, is for him the purest imaginative therapy. In the past year alone, Roosevelt has devoured all the novels of Trollope, the complete works of De Quincey, a Life of Saint Patrick, the prose works of Milton and Tacitus (“until I could stand them no longer”), Samuel Dill’s Roman Society from Nero to Marcus Aurelius, the seafaring yarns of Jacobs, the poetry of Scott, Poe, and Longfellow, a German novel called Jörn Uhl, “a most satisfactorily lurid Man-eating Lion story,” and Foulke’s Life of Oliver P. Morton, not to mention at least five hundred other volumes, on subjects ranging from tropical flora to Italian naval history.120

The richness of Roosevelt’s knowledge causes a continuous process of cross-fertilization to go on in his mind. Standing with candle in hand at a baptismal service in Santa Fe, he reflects that his ancestors, and those of the child’s Mexican father, “doubtless fought in the Netherlands in the days of Alva and Parma.” Watching a group of American sailors joke about bedbugs in the Navy, he is reminded of the freedom of comment traditionally allowed to Roman legionnaires after battle. Trying to persuade Congress to adopt a system of simplified spelling in Government documents, he unself-consciously cites a treatise on the subject published in the time of Cromwell.121

Tonight the President will bury himself, perhaps, in two volumes Mrs. Lodge has just sent him for review: Gissing’s Charles Dickens, A Critical Study, and The Greek View of Life, by Lowes Dickinson. He will be struck, as he peruses the latter, by interesting parallels between the Periclean attitude toward women and that of presentday Japan, and will make a mental note to write to Mrs. Lodge about it.122 He may also read, with alternate approval and disapproval, two articles on Mormonism in the latest issue ofOutlook. A five-thousand-word essay on “The Ancient Irish Sagas” in this month’s Century magazine will not detain him long, since he is himself the author.123 His method of reading periodicals is somewhat unusual: each page, as he comes to the end of it, is torn out and thrown onto the floor.124 When both magazines have been thus reduced to a pile of crumpled paper, Roosevelt will leap from his rocking-chair and march down the corridor. Slowing his pace at the door of the presidential suite, he will tiptoe in, brush the famous teeth with only a moderate amount of noise, and pull on his blue-striped pajamas. Beside his pillow he will deposit a large, precautionary revolver.125 His last act, after turning down the lamp and climbing into bed, will be to unclip his pince-nez and rub the reddened bridge of his nose. Then, there being nothing further to do, Theodore Roosevelt will energetically fall asleep.