Force rules the world still,

Has ruled it, shall rule it;

Meekness is weakness,

Strength is triumphant!

![]()

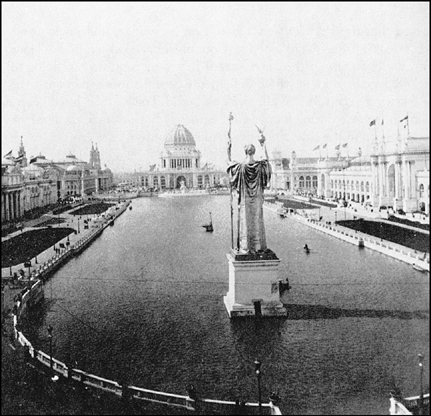

“WE HAVE BUILT these splendid edifices,” roared Grover Cleveland, “but we have also built the magnificent fabric of a popular government, whose grand proportions are seen throughout the world.”1 His eyes flickered back and forth: he was trying to read his notes, seek out an ivory button, and address two hundred thousand people simultaneously. The eyes of the crowd, too, were restless. They shifted from the President’s fat forefinger, as it hovered over the button, to the inert fountains, the furled flags, the motionless wheels in the Palace of Mechanic Arts, and the enshrouded statue looming against the fogbanks of Lake Michigan.

“As by a touch the machinery that gives life to this vast Exposition is now set in motion, so at the same instant let our hopes and aspirations awaken forces which in time to come”—Maestro Thomas raised his baton over seven hundred musicians, and for the first moment that morning a hush descended on the Grand Court—“shall influence the welfare, the dignity, and the freedom of mankind,” Cleveland intoned, and pressed the button. It was eight minutes past noon, Chicago time, on 1 May 1893.

“The fair by no means matched the splendor of his own dreams for America.”

The Grand Court of the World’s Columbian Exposition, Chicago, 1893. (Illustration 18.1)

From the flagstaff crowning the gold-domed Administration Building, three hundred feet above the President’s head, Old Glory broke forth, a split second before the lower banners of Christopher Columbus and Spain.2 Seven hundred other ensigns exploded brilliantly over the White City. The great Allis engine coughed into life, and seven thousand feet of shafting began to move. Fountains gushed so high that umbrellas popped up everywhere; and the folds fell from the Statue of the Republic, revealing a gilt goddess facing west, her arms extended toward the frontier.

The noise accompanying this cataclysmic moment—the first demonstration, on a massive scale, of the generative powers of electricity—was appropriately tremendous. From the lake came the thunder of naval artillery and the shriek of countless steam whistles. Carillons pealed, the orchestra crashed out Handel’s Hallelujah Chorus, and louder than everything else rose the roaring of the crowd. The war-whooping of seventy-five Sioux added savage overtones. This bedlam continued for ten full minutes; then “America” sounded on massed trombones, and the roaring turned to singing. Even the stolid Cleveland was moved to join in, to the embarrassment of his guest of honor, Cristóbal, duke of Veragua, Columbus’s senior living descendant. The little Spaniard stood bowed under the weight of his inherited epaulets, silent in the universal chorus:

Let music swell the breeze,

And ring from all the trees

Sweet freedom’s song!

Theodore Roosevelt did not arrive in Chicago for another ten days3—his own modest contribution to the World’s Fair was a Boone & Crockett Club cabin, dedicated 15 May4—but he had little need of music and artillery to swell his love of country. Indeed, this stupendous exposition, whose combination of classical architecture and modern technology so bewildered Henry Adams that he felt the universe was tottering,5 was to Roosevelt an entirely natural and logical product of American civilization. He was conventionallymoved by its grandeur (“the most beautiful architectural exhibit the world has ever seen”),6 but the Fair by no means matched the splendor of his own dreams for America. These palaces, after all, were carved out of plaster, and would survive, at most, for a couple of seasons; his Columbia would burgeon for centuries.

To Adams, sitting with spinning head on the steps of the Administration Building, the World’s Fair asked for the first time “whether the American people knew where they were driving.” He suspected they did not, “but that they might still be driving or drifting unconsciously to some point in thought, as their solar system was said to be drifting towards some point in space; and that, possibly, if relations enough could be observed, this point might be fixed. Chicago was the first expression of American thought as a unity; one must start there.”7

Roosevelt felt no need to ask, or answer, such questions. He had long known exactly where the United States was drifting, just as he had throughout life known where he was driving. He came to the White City, gazed cheerfully upon it, then hurried off to Indianapolis on Civil Service Commission business.8 There was no need to stop and ponder the dynamos, the “new powers” which so mystified Henry Adams, for he felt their energy whirring within himself. Theodore Roosevelt, as the British M.P. John Morley later observed, “was” America9—the America that grew to maturity after the Civil War, marshaled its resources at Chicago, and exploded into world power at the turn of the century.

Grover Cleveland’s adjectives on Opening Day—splendid, magnificent, grand, vast—were no different from those Roosevelt himself had lavished on America in all his books. The symbolism of the flags, and of the little Spanish admiral dwarfed by a three-hundred-pound American President, was pleasing to him, but not revelatory. Nine years before, in his Fourth of July oration to the cowboys of Dickinson, he had hoped “to see the day when not a foot of American soil will be held by any European power,” and instinct told him that that day was fast approaching. When it came, it would bring out what some consider the best, what others consider the worst in him. This overriding impulse has been given many names: Jingoism, Nationalism, Imperialism, Chauvinism, evenFascism and Racism. Roosevelt preferred to use the simple and to him beautiful word Americanism.

![]()

THE WINNING OF THE WEST, which occupied Roosevelt, on and off, for nearly nine years, was the first comprehensive statement of his Americanism, and, by extension (since he “was” America), of himself. All his previous books had been, in a sense, sketches for this one, just as his subsequent books were postscripts to it, of diminishing historical and psychological interest. One by one, themes he had touched on in the past came up for synthesis and review: the importance of naval preparedness, and effect of ethnic derivations on fighting blood (The Naval War of 1812); the identity of native Americans with their own flora and fauna (Hunting Trips of a Ranchman); the doctrine of Manifest Destiny (Thomas Hart Benton); the need for law and order in a savage environment(Ranch Life and the Hunting Trail); the significance of the United States Constitution (Gouverneur Morris); the problems of free government (Essays in Practical Politics); and the social dynamics of immigration (New York).

Nothing written prior to Roosevelt’s Presidency shows the breadth of his mind to greater advantage than the introduction to The Winning of the West, which makes it clear that his specific subject—white settlement of Indian lands west of the Alleghenies in the late eighteenth century—is but a chapter in the unfolding of an epic racial saga, covering thousands of years and millions of square miles. The erudition with which he traces the “perfectly continuous history” of Anglo-Saxons from the days of King Alfred to those of George Washington is impressive. He draws effortless parallels between the Romanticization of the Celto-Iberians in the second century B.C. and the capture of Mexico and Peru by the conquistadores; between the Punic Wars and the War of the American Revolution; even between the future of whites in South Africa and the fate of Greek colonists in the Tauric Chersonese.

“During the past three centuries,” Roosevelt begins, “the spread of the English-speaking peoples over the world’s waste spaces has been not only the most striking feature in the world’s history, but also the event of all others most far-reaching in its importance.”10What else but destiny—a destiny yet to be fully realized—can explain the remorseless advance of Anglo-Saxon civilization? The language of what was, in Queen Elizabeth’s time, “a relatively unimportant insular kingdom … now holds sway over worlds whose endless coasts are washed by the waves of three great oceans.” Never in history has a race expanded over so wide an area in so short a time; and the winning of the American West may be counted as “the crowning and greatest achievement” of that mighty movement.11

The narrative proper begins in chapter 6 with the first trickle of settlement following Daniel Boone’s penetration of the Cumberland Gap in 1765. Roosevelt uses a striking flood metaphor: “The American backswoodsmen had surged up, wave upon wave, till their mass trembled in the troughs of the Alleghenies, ready to flood the continent beyond.”12 As the flood gathers volume, he achieves the effect of ever-widening waves by making his chapters overlap, every one moving farther afield geographically, and further ahead in time. So intoxicated is Roosevelt as he rides these waves that he sweeps uncaring past such solid obstructions as Institutional Analysis and Land Company Proceedings. (“I have always been more interested in the men themselves than the institutions through which they worked,” he confessed.)13 He might have added, “and in action rather than theory.” Far and away the best parts of The Winning of the West are the fighting chapters. In describing border battles, Roosevelt reveals himself with the utter unself-consciousness which was always part of his charm. He makes no secret of his boyish identification with those gaunt, fierce warriors of the frontier, who were “strong and simple, powerful for good and evil, swayed by gusts of stormy passion, the love of freedom rooted in their very heart’s core.”14

Here is Roosevelt the aggressor, single-handedly killing or crippling seven Indians in the pitch darkness of his pioneer log cabin; wrenching himself from the stake and running naked for five days through mosquito country; trying consecutively to shoot, knife,throttle, and drown a reluctant Chief Bigfoot, while his own brother puts a bullet in his back; advancing upon Vincennes through mile after mile of freezing, waist-deep water; and, in a moment of supreme ecstasy, spurring a white horse over a sheer, three-hundred-foot cliff:

There was a crash, the shock of a heavy body, half-springing, half-falling, a scramble among loose rocks, and the snapping of saplings and bushes; and in another moment the awestruck Indians above saw their unarmed foe, galloping his white horse in safety across the plain.15

Here, too, is Roosevelt the righteous, assailing the “warped, perverse, and silly morality” that would preserve the American continent “for the use of a few scattered savage tribes, whose life was but a few degrees less meaningless, squalid, and ferocious than that of the wild beasts with whom they held joint ownership.”16 He pours scorn on “selfish and indolent” Easterners who fail to see the “race-importance” of the work done by Western pioneers.17 Yet Roosevelt is not sentimental about the latter. He shows the tendency of the frontier to barbarize both conqueror and conquered, until such civilized issues as good v. evil, law v. anarchy, are forgotten in the age-old struggle of Man against Man.18

It is a primeval warfare, and it is waged as war was waged in the ages of bronze and iron. All the merciful humanity that even war has gained during the last two thousand years is lost. It is a warfare where no pity is shown to non-combatants, where the weak are harried without ruth, and the vanquished are maltreated with merciless ferocity. A sad and evil feature of such warfare is that the whites, the representatives of civilization, speedily sink almost to the level of their barbarous foes, in point of hideous brutality.19

Yet, says Roosevelt, this kind of struggle is “elemental in its consequences to the future of the world.” In a paragraph which will return to haunt him, he proclaims:

The most ultimately righteous of all wars is a war with savages, though it is apt to be also the most terrible and inhuman. The rude, fierce settler who drove the savage from the land lays all civilized mankind under a debt to him. American and Indian, Boer and Zulu, Cossack and Tartar, New Zealander and Maori—in each case the victor, horrible though many of his deeds are, has laid deep the foundations for the future greatness of a mighty people … it is of incalculable importance that America, Australia, and Siberia should pass out of the hands of their red, black, and yellow aboriginal owners, and become the heritage of the dominant world races.20

Roosevelt the proud saw no reason to retract this passage in later life, for the overall context of The Winning of the West makes plain that he regarded any such race-struggle as ephemeral. Once civilization was established, the aborigine must be raised and refined as quickly as possible, so that he may partake of every opportunity available to the master race—in other words, become master of himself, free to challenge and beat the white man in any field of endeavor. Nothing could give Roosevelt more satisfaction than to see such a reversal, for he admired individual achievement above all things. Any black or red man who could win admission to “the fellowship of the doers” was superior to the white man who failed.21 Roosevelt’s long-term dream was nothing more or less than the general, steady, self-betterment of the multicolored American nation.22

Of Roosevelt the military man, as revealed in The Winning of the West, little need be said. Chapter after chapter, volume after volume, demonstrates his ability to analyze the motives that drive men to battle, to define the mysterious powers of leadership, and weigh the relative strengths of armies. His accounts of the Battle of King’s Mountain and the defeat of St. Clair are so full of visual and auditory detail, and exhibit such an uncanny sense of terrain, that it is hard to believe the author himself has never felt the shock of arms. One can only infer from the power and brilliance of the prose that such passages are the sublimation of his most intense desires, and that until he can charge, like Colonel William Campbell, up an enemy-held ridge at the head of a thousand wiry horse-riflemen, he will never be fulfilled.23

![]()

ROOSEVELT WAS NOT ALONE in his efforts during the early 1890s to define and explore the origins of Americanism. Long before the final volume of The Winning of the West was published, other young intellectuals took up and developed his theme that the true American identity was to be found only in the West. The most brilliant of these was Frederick Jackson Turner, who came to the Chicago World’s Fair in July 1893 to deliver his seminal address, “The Significance of the Frontier in American History,” before an audience of aging, puzzled academics.24

Turner had admiringly reviewed Roosevelt’s first two volumes in 1889, and had marked in his personal copy a passage describing the “true significance” of “the vast movement by which this continent was conquered and peopled.”25 His thesis—that “the existence of an area of free land, its continuous recession, and the advancement of American settlement westward explain American development”—was identical with that of The Winning of the West, albeit expressed more succinctly.26 But Turner refined away much of the crudity of Roosevelt’s ethnic thinking. It was not “blood,” but environment that made the American frontiersman unique: he was shaped by the challenge of his situation “at the meeting-point between savagery and civilization.” Forced continually to adapt himself to new dangers and new opportunities, as the frontier moved West, he was “Americanized” at a much quicker rate than the sedentary, Europe-influenced Easterner. Consequently, said Turner, it was “to the frontier that the American intellect owes its most striking characteristics.”27 And in listing those characteristics, Turner painted an accurate portrait of somebody not unfamiliar to readers of this biography:

That coarseness and strength combined with acuteness and inquisitiveness; that practical, inventive turn of mind, quick to find expedients; that masterful grasp of material things, lacking in the artistic but powerful to effect great ends; that restless nervous energy; that dominant individualism, working for good and evil, and withal that buoyancy which comes with freedom—these are the traits of the frontier.…28

Turner closed his great essay on an elegaic note. The Chicago World’s Fair marked more than the four hundredth anniversary of the arrival of Columbus in the New World; it coincidentally marked the end of the era of free land. An obscure government pamphlet had recently announced that, since the frontier was now almost completely broken up by settlements, “it cannot … any longer have a place in the census reports.”29 This apparently unnoticed sentence, said Turner, made it clear that the United States had reached the limits of its natural expansion. Yet what of “American energy … continually demanding a wider field for its exercise”? Turner did not dare answer that question. All he knew was “the frontier has gone, and with its going has closed the first period of American history.”30

Theodore Roosevelt was not among Turner’s drowsy audience that hot summer’s day, but he was one of the first historians to sense the revolutionary qualities of the thesis when it was published early in 1894.31 “I think you have struck some first class ideas,” he wrote enthusiastically, “and have put into definite shape a good deal of thought which has been floating around rather loosely.”32 This was hardly the profound scholarly praise which Turner craved; but the older man’s warmth, and his promise to quote the thesis in Volume Three of The Winning of the West, “of course making full acknowledgement,” was flattering.33 Turner thus became yet another addition to the circle of Roosevelt’s academic admirers, and a fascinated observer of his later career.34 If one could no longer see the frontier retreat, one could have fun watching Theodore advance.

Roosevelt spent much of his time during the years 1893–95 formulating theories of Americanism, partly under the influence of Turner, but mostly under the influence of his own avidly eclectic reading. Gradually the theories coalesced into a philosophy embracing practically every aspect of American life, from warfare to wild-flowers.35 He began to publish patriotic articles with titles like “What Americanism Means,” and continued to write such pieces, with undiminished fervor, for the rest of his life. In addition he preached the gospel of Americanism, ad nauseam, at every public or private opportunity. Ninety-nine percent of the millions of words he thus poured out are sterile, banal, and so droningly repetitive as to defeat the most dedicated researcher. There is no doubt that on this subject Theodore Roosevelt was one of the bores of all ages; the wonder is that during his lifetime so many men, women, and children worshipfully pondered every platitude. Here is an example, taken from the above-named essay:

We Americans have many grave problems to solve, many threatening evils to fight, and many deeds to do, if, as we hope and believe, we have the wisdom, the strength, and the courage and the virtue to do them. But we must face facts as they are. We must neither surrender ourselves to a foolish optimism, nor succumb to a timid and ignoble pessimism … .36

And so on and on; once Roosevelt got a good balanced rhythm going, he could continue indefinitely, until his listeners, or his column-inches, were exhausted.

An analysis of “What Americanism Means”37 discloses that even when dealing with what is presumably a positive subject, Roosevelt’s instinct is to express himself negatively, to attack un-Americans rather than praise all-Americans. Imprecations hurled at the former outnumber adjectives of praise for the latter almost ten to one. Selecting at random, we find base, low, selfish, silly, evil, noxious, despicable, unwholesome, shameful, flaccid, contemptible—together with a plentiful sprinkling of pejorative nouns:weaklings, hypocrites, demagogues, fools, renegades, criminals, idiots, anarchists … One marvels at the copious flow of his invective, especially as the victims of it are not identified. It is possible, however, to single out Henry James, that “miserable little snob”38 whose preference for English society and English literature drove Roosevelt to near frenzy:

Thus it is for the undersized man of letters, who flees his country because he, with his delicate, effeminate sensitiveness, finds the conditions of life on this side of the water crude and raw; in other words, because he finds that he cannot play a man’s part among men, and so goes where he will be sheltered from the winds that harden stouter souls.

In such manner did Roosevelt, with the shrewd instinct of a rampant heterosexual, kick James again and again in his “obscure hurt,” until the novelist was moved to weary protest. “The national consciousness for Mr. Theodore Roosevelt is … at the best a very fierce affair.”39 James was too courteous to say more in print, but he privately characterized Roosevelt as “a dangerous and ominous jingo,” and “the mere monstrous embodiment of unprecedented and resounding Noise.”40

![]()

IT IS A RELIEF to turn from Roosevelt’s own spontaneous essays to those prompted by the philosophizing of others, notably the English historian Charles H. Pearson, whose National Life and Character: A Forecast appeared in early 1894. Roosevelt wrote a ten-thousand word reply to this work of gentle, scholarly pessimism for publication in the May issue of Sewanee Review.41 It represents altogether the better side of him, both as a man and as a writer, and can be taken as his confident answer to those who, like Pearson and Henry Adams, shuddered at the nearness of the twentieth century.

“At no period of the world’s history,” says Roosevelt, “has life been so full of interest, and of possibilities of excitement and enjoyment.” Science has revolutionized industry; Darwin has revolutionized thought; the globe’s waste spaces are being settled and seeded. A man of ambition has unique opportunities to build, explore, conquer, and transform. He can taste “the fearful joy” of grappling with large political and administrative problems. “If he is observant, he notes all around him the play of vaster forces than have ever before been exerted, working, half blindly, half under control, to bring about immeasurable results.”42

Roosevelt refuses to look at the future through the “dun-colored mists” of pessimism, yet he does not pretend to see it all clearly. “Nevertheless, signs do not fail that we shall see the conditions of our lives, national and individual, modified after a sweeping andradical fashion. Many of the forces that make for national greatness and for individual happiness in the nineteenth century will be absent entirely, or will act with greatly diminished strength, in the twentieth. Many of the forces that now make for evil will by that time have gained greatly in volume and power.”

Pearson’s theory that “the higher races” cannot long subjugate black and brown majorities finds Roosevelt in complete agreement, for “men of our stock do not prosper in tropical countries.” Only in thinly peopled, temperate regions is there any lasting hope for European civilization. A secure future is promised the English-speaking conquerors of North America and Australia, as well as the Russians, who “by a movement which has not yet fired the popular imagination, but which thinking men recognize as of incalculable importance, are building up a vast state in northern Asia.”43 But Europeans hoping “to live and propagate permanently in the hot regions of India and Africa” are doomed. In one of the earliest of his many remarkable flights of historical prophecy (flawed only by an exaggerated time-scale), he writes:

The Greek rulers of Bactria were ultimately absorbed and vanished, as probably the English rulers of India will some day in the future—for the good of mankind, we sincerely hope and believe in the very remote future—themselves be absorbed and vanish. In Africa south of the Zambesi (and possibly here and there on high plateaus north of it) there may remain white States, although even these States will surely contain a large colored population, always threatening to swamp the whites … It is almost impossible that they will not in the end succeed in throwing off the yoke of the European outsiders, though this end may be, and we hope will be, many centuries distant. In America, most of the West Indies are becoming negro islands … it is impossible for the dominant races of the temperate zones ever bodily to displace the peoples of the tropics.44

Roosevelt is serenely untroubled by Pearson’s fear that the black and yellow races of the world will one day attain great economic and military power and threaten their erstwhile masters. “By that time the descendant of the negro may be as intellectual as the Athenian … we shall then simply be dealing with another civilized nation of non-Aryan blood, precisely as we now deal with Magyar, Finn, and Basque.”45

Turning from global to national matters, Roosevelt discusses the phenomenon of the “stationary state,” in which a freely developing nation tends to become rigid and authoritarian as its period of upward mobility comes to an end. But again he sees no cause for concern. It is right and proper that the power of government should increase to counteract “the mercilessness of private commercial warfare.” As for that other tendency of a maturing civilization, the crowding out of the upper class by the middle and lower, Roosevelt welcomes it as he welcomes all natural processes. Every new generation, he says, will increase the proportion of mechanics, workmen, and farmers to that of scientists, statesmen, and poets, but as long as the aggregate population increases there will be no decline in cultural values. On the contrary, the nation’s overall quality will improve, thanks to “the transmission of acquired characters” by an ever-thinning, ever-refining aristocracy.46 This process “in every civilization operates so strongly as to counterbalance … that baleful law of natural selection which tells against the survival of the most desirable classes.”47

Reducing his focus yet again to the domestic environment, Roosevelt “heartily disagrees” with Pearson’s mistrust of Americanized, democratic families. “To all who have known really happy family lives,” he writes, “that is, to all who have known or who have witnessed the greatest happiness which there can be on this earth, it is hardly necessary to say that the highest idea of the family is attainable only where the father and mother stand to each other as lovers and friends. In these homes the children are bound to father and mother by ties of love, respect, and obedience, which are simply strengthened by the fact that they are treated as reasonable beings with rights of their own, and that the rule of the household is changed to suit the changing years, as childhood passes into manhood and womanhood.”48

Roosevelt is making no effort to be metaphorical, but this whole simple and beautiful passage may be taken as symbolic of his attitude to his country and the world. Father is Strength in the home, just as Government is Strength in America, and America is (or ought to be) Strength overseas. Mother represents Upbringing, Education, the Spread of Civilization. Children are the Lower Classes, the Lower Races, to be brought to maturity and then set free.

“We do not agree,” Roosevelt concludes, “… that there is a day approaching when the lower races will predominate in the world, and the higher races will have lost their noblest elements … On the whole, we think that the greatest victories are yet to be won, the greatest deeds yet to be done … the one plain duty of every man is to face the future as he faces the present, regardless of what it may have in store for him, turning toward the light as he sees the light, to play his part manfully, as a man among men.”49

![]()

ROOSEVELT WAS CERTAINLY playing his own part manfully when he wrote the above lines in the early spring of 1894. His intellectual activity was as intense as it had ever been. Having published, in late 1893, The Wilderness Hunter, the third of his great nature trilogy and arguably his finest book,50 he was now simultaneously at work on Volumes Three and Four of The Winning of the West, planning the never-to-be-written Volumes Five and Six, editing his second Boone & Crockett Club anthology (to which he also contributed scholarly articles), reading Kipling, and addressing a variety of correspondents on subjects ranging from British court procedures to arboreal distinctions between Northern and Southern mammalian species. In addition, he had recently begun a part-time career as a professional lecturer, and took frequent quick trips out of town to speak in New York or Boston on history, hunting, municipal politics, and “the subject on which I feel deepest,” U.S. foreign policy.51

There was a reason for all this activity, abnormal even by his standards. During the previous summer, Grover Cleveland had presided unhappily over the worst financial panic in American history—a crisis so severe as to make the plaster palaces of Chicago seem but hollow symbols indeed. The nation’s steady outflow of gold, caused by a steady rise in imports and monthly purchases of silver by the government (mandatory since the Silver Purchase Act of 1890), could only be stopped by drastic action, and Cleveland had summoned an emergency session of Congress on 7 August 1893. Despite violent opposition from his own party, the President managed to force the repeal of the controversial act on 28 August. He thus saved the nation’s credit, but transformed himself overnight into the most unpopular President since James Buchanan.52 Americans high and low felt the icy threat of bankruptcy that winter, and Roosevelt, still striving vainly to recover from his losses in Dakota, was no exception. His accounts showed a crippling deficit of $2,500 in December 1893; Edith, in her private letters, put the total nearer $3,000.53 Roosevelt complained that his ill-paid government job was “not the right career for a man without means.” The sale of six acres of property on Sagamore Hill, at $400 apiece,54brought him temporary security, but Roosevelt knew he would still have to scrabble for freelance pennies during the next few years in order to save his home and educate his children. The birth of a son, Archibald Bulloch, on 10 April 1894, was further cause for concern. “I begin to think that this particular branch of the Roosevelt family is getting to be numerous enough.”55

Although he professed still to be enjoying his work as Civil Service Commissioner, and to “get on beautifully with the President,”56 an increasing restlessness through the spring and summer of 1894 is palpable in his correspondence. It would be needlessly repetitive to describe the battles he fought for reform under Cleveland, for they were essentially the same as those he fought under Harrison. “As far as my work is concerned,” he grumbled, “the two Administrations are much of a muchness.”57 There were the same “mean, sneaky little acts of petty spoilsmongering” in government; the same looting of federal offices across the nation, which Roosevelt combated with his usual weapons of publicity and aggressive investigation; the same pleas for extra funds and extra staff (“we are now, in all, five thousand papers behind”); the same fiery reports and five-thousand-word letters bombarding members of Congress; the same obstinate lobbying at the White House for extensions of the classified service; the same compulsive attacks upon porcine opponents, such as Assistant Secretary of State Josiah P. Quincy, hunting for patronage “as a pig hunts truffles,” and Secretary of the Interior Hoke Smith, “with his twinkling little green pig’s eyes.”58

All this, of course, meant that Roosevelt was having fun. As Cecil Spring Rice remarked, “Teddy is consumed with energy as long as he is doing something and fighting somebody … he always finds something to do and somebody to fight. Poor Cabot must be successful; while Teddy is happiest when he conquers but quite happy if he only fights.”59

He continued utterly to dominate the Civil Service Commission, not without some protest on the part of General George D. Johnston, Hugh Thompson’s old and crotchety successor. On several occasions their altercations grew so violent that Roosevelt said only a sense of propriety restrained him from “going down among the spittoons with the general.”60 Things became dangerous when Johnston, who wore a pistol at all times, objected to Roosevelt’s office being carpeted before his. Roosevelt had a private talk with President Cleveland, and the general was offered two remote diplomatic posts, in Vancouver and Siam. He refused both, whereupon Cleveland summarily removed him.61

This enabled Roosevelt to bring in a new Commissioner, John R. Procter, of Kentucky. Procter was a tall, scholarly geologist and Civil Service Reformer who had caught Roosevelt’s eye in the spring of 1893, and whom he had then hoped—in vain—would replace “silly well-meaning Lyman.”62 Now, with Procter in, he at last had “a first-class man” he could groom to take over, and continue his policies as Civil Service Commissioner. Roosevelt was beginning to talk of stepping down after one more winter in Washington, “although I am not at all sure as to what I shall do afterwards.”63

![]()

MANY WRITERS OTHER THAN Henry Adams have compared Theodore Roosevelt’s career to that of an express locomotive, speeding toward an inevitable destination. The simile may be extended to describe his two static years under President Cleveland as a mid-journey pause to stoke up with coal and generate a new head of steam. The first signs that he was about to get under way again occurred in the late summer of 1894: there was the lift of a signal, a flickering of needles, the anguish of a personal farewell, a groan of loosening brakes. From now on Roosevelt’s acceleration would be continuous—almost frighteningly so to some observers, but very exhilarating to himself.

Sometime during the first week in August, Congressman Lemuel Ely Quigg of New York, an attractive, prematurely grizzled political schemer, dropped a subtle hint regarding Roosevelt’s future. What a pity it was, he sighed, that Roosevelt was possessed of “such a variety of indiscretions, fads and animosities” that it would be impossible to nominate him for Mayor of New York in the fall.64 The odds of a Republican victory in that city were higher than they had been for years; what was more, there seemed to be a good chance of getting a reform ticket elected. Roosevelt rejected Quigg’s hint good-humoredly (“I have run once!”), but ambition stirred within him. He had never quite gotten over his failure to capture control of his native city in 1886, and the temptation to try and transcend that failure soon became irresistible. He broached the subject with Edith, but she protested vehemently. To run for Mayor, she said, would require him to spend money they simply did not have, and the prize was by no means assured. Pitiful as his present salary was, it was at least better than the nothing he would earn as a twice-defeated mayoral candidate. Roosevelt miserably told Quigg he would have to think the matter over.65

On 7 August, President Cleveland recognized the new Republic of Hawaii,66 to Roosevelt’s grim satisfaction. This meant that the United States at last had a firm ally and naval base in the Pacific, to counter the burgeoning might of Japan. Roosevelt had been fuming for sixteen months over Cleveland’s obstinate refusal to sign the annexation treaty prepared for him by President Harrison. “It was a crime against the United States, it was a crime against white civilization.”67 In his opinion the President should now start to build up the Navy, and order the digging of an interoceanic canal in Central America “with the money of Uncle Sam.”68 However Roosevelt knew there was not much chance of that, for the Democrats were “very weak” about foreign policy. “Cleveland does his best, but he is not an able man.”69

On Monday, 13 August, a telegram arrived to say that Elliott Roosevelt (drinking heavily again and reunited with his mistress in New York) was very ill indeed.70 Roosevelt, desk-bound in Washington, did not respond: he knew from experience that Elliott would not let any members of the family come near him. There had been many such messages in recent months. “He can’t be helped, and he must simply be let go his own gait.”71 The following day Elliott, racked with delirium tremens, tried to jump out of the window of his house, suffered a final epileptic fit, and died. Distraught, Theodore hurried to New York, and saw stretched out on a bed, not the bloated souse of recent years, but the handsome youth of “the old time, fifteen years ago, when he was the most generous, gallant, and unselfish of men.”72 The sight shattered him. “Theodore was more overcome than I have ever seen him,” Corinne reported, “and cried like a little child for a long time.”73

Theodore recovered his equanimity in time to veto “the hideous plan” that Elliott be buried with his wife. Instead, a grave was dug in Greenwood Cemetery, “beside those who are associated only with his sweet innocent youth.” At the funeral on Saturday, Roosevelt noted with some surprise that “the woman” and two of her friends “behaved perfectly well, and their grief seemed entirely sincere.”74

![]()

ON 4 SEPTEMBER he started West to shoot a few antelope and ponder the New York mayoralty. He felt depressed and ill, and Dakota’s drought-stricken landscape drove him back to Oyster Bay after only two weeks on the range. Edith was still adamantly against his running in October, and Theodore, who was as putty in her hands, decided to turn Quigg down. But this was by no means easy. Quigg was so sure of his acceptance that a special nominating Committee of Seventy had been formed, and was determined to nominate him as a reform candidate; he had to refuse four times before they would accept his decision.75 He sank into a mood of bitter remorse as his thirty-sixth birthday approached, for he felt himself a political failure. His whole instinct was to run: after well over five years of appointive office he craved the thrill of an election campaign. At all costs he must keep his chagrin private. “No outsider should know that I think my decision was a mistake.” Henry Cabot Lodge received the terse explanation, “I simply had not the funds to run.”76 But after a further period of brooding, Roosevelt had to unburden himself to his friend:

I would literally have given my right arm to have made the race, win or lose. It was the one golden chance, which never returns; and I had no illusions about ever having another opportunity; I knew it meant the definite abandonment of any hope of going on in the work and life for which I care more than any other. You may guess that these weeks have not been particularly pleasant ones … At the time, with Edith feeling as intensely as she did, I did not see how I could well go in; though I have grown to feel more and more that in this instance I should have gone counter to her wishes … the fault was mine, not Edith’s; I should have realized that she could not see the matter as it really was, or realize my feelings. But it is one of the matters just as well dropped.77

William L. Strong, a middle-aged businessman with little or no political experience, was duly nominated by the Republicans of New York; he ran on a popular reform ticket, and was elected. And so the mayoral campaign of 1894 joined that of 1886 as another of Roosevelt’s unspoken, passionate regrets.

![]()

RETURNING TO WORK at the Civil Service Commission now was “a little like starting to go through Harvard again after graduating,”78 and that telltale sign of Rooseveltian frustration, bronchitis, recurred in December. For a week he was confined to his bed. A strange tone of nostalgia for his native city crept into his correspondence, as he obsessively discussed Mayor Strong’s appointments and the prospects for real reforms of the municipal government. Shortly before Christmas a message arrived from Strong: would he care to accept the position of Street Cleaning Commissioner in New York?79

Roosevelt was “dreadfully harassed” by the offer. Thirteen years before, when he first stood up in his evening clothes to speak at Morton Hall, he had addressed himself to the subject of street cleaning. But something told him that his future lay elsewhere than in garbage collection. He declined with exquisite tact, obviously hoping for a more suitable offer.80 In the meantime there was more than enough federal business to keep him occupied. President Cleveland had at last begun to extend the classified service; John Procter was responding well to Roosevelt’s training; another season of hard work would “put the capstone” on his achievements as Civil Service Commissioner.81

![]()

THE YEAR 1895 opened snowy and crisp, and Roosevelt plunged into the familiar round of receptions and balls and diplomatic breakfasts, to which he was by now shamelessly addicted. “I always eat and drink too much,” he mourned. “Still … it is so pleasant to deal with big interests, and big men.”82

A particularly big interest loomed in February. Revolutionaries in Cuba, Spain’s last substantial fragment of empire in the New World, declared war on the power that had oppressed them for centuries. Instantly expansionists in the capital began to discuss the pros and cons of supporting the cause of Cuban independence. Henry Adams’s salon at 1603 H Street became a hotbed of international intrigue, with Cabot Lodge and John Hay weighing the strategic and economic advantages of U.S. intervention, and Clarence King rhapsodizing over the charms of Cuban women.83 Roosevelt, true to form, dashed off a note to Governor Levi P. Morton of New York, begging that “in the very improbable event of a war with Spain” he would be included in any regiment the state sent out. “Remember, I make application now … I must have a commission in the force that goes to Cuba!”84

As for “big men,” he encountered on 7 March a genius greater than any he had yet met, with the possible exception of Henry James.85 Rudyard Kipling was not quite thirty, but was already the world’s most famous living writer,86 and Roosevelt hastened to invite him to dinner. At first they did not get on too well. Kipling, Roosevelt wrote, was “bright, nervous, voluble and underbred,” and displayed an occasional truculence toward America which required “very rough handling.”87 Kipling’s manners improved, and the two men became fond of each other. Roosevelt introduced Kipling to his literary and political acquaintances, escorted him to the zoo to see grizzlies, and to the Smithsonian to see Indian relics. From time to time he thanked God in a loud voice that he had “not one drop of British blood in him.” When Kipling amusedly mocked the self-righteousness of a nation that had extirpated its aboriginals “more completely than any modern race has done,” Roosevelt “made the glass cases of the museum shake with his rebuttals.”88

Roosevelt’s activity became more and more strenuous as spring approached. He dashed in and out of town on Civil Service Commission business, taught himself to ski, bombarded his friends in the New York City government with advice and suggestions, continued to toil on Volume Four of The Winning of the West and collaborated with Cabot Lodge on a book for boys, Hero Tales from American History.89 Friends noticed hints of inner turbulence. He was seen “blinking pitifully” with exhaustion at a dinner for Owen Wister and Kipling,90 and his tirades on a currently fashionable topic—whether dangerous sports should be banned in the nation’s universities—became alarmingly harsh. “What matters a few broken bones to the glories of inter-collegiate sport?” he cried at a Harvard Club dinner. (Meanwhile, not far away in hospital, the latest victim of football savagery lay paralyzed for life.)91 He declared publicly that he would “disinherit” any son of his who refused to play college games. And in private, through clenched teeth: “I would rather one of them should die than have them grow up as weaklings.”92

Clearly he was under considerable personal strain. The reason soon became evident. He was torn between his longing to join Mayor Strong’s reform administration in New York, and his instinct to stay put until the next presidential election. Toward the end of March he told Lemuel Quigg that he would like to be one of the four New York Police Commissioners, but waxed coy when Quigg said it could be arranged. He dispatched Lodge to New York to discuss the matter further. “The average New Yorker of coursewishes me to take it very much,” Roosevelt mused on 3 April. “I don’t feel much like it myself …” On the other hand, it was a glamorous job—“one I could perhaps afford to be identified with.”93 Before the day was out, he had reached his decision:

TO LEMUEL ELY QUIGG

WASHINGTON, APRIL 3, 1895

LODGE WILL SEE YOU AND TELL YOU. I WILL ACCEPT SUBJECT TO HONORABLE CONDITIONS. KEEP THIS STRICTLY CONFIDENTIAL.

THEODORE ROOSEVELT94

![]()

THE APPOINTMENT WAS CONFIRMED on 17 April, by which time Roosevelt was quite reconciled to leaving Washington. “I think it a good thing to be identified with my native city again.”95 Mayor Strong asked him to be ready to take office about the first of May. Roosevelt promptly sent his resignation to President Cleveland.

I have now been in office almost exactly six years, a little over two years of the time under yourself; and I leave with the greatest reluctance … During my term of office I have seen the classified service grow to more than double the size that it was six years ago … Year by year the law has been better executed, taking the service as a whole, and in spite of occasional exceptions in certain offices and bureaus. Since you yourself took office this time nearly six thousand positions have been put into the classified service … it has been a pleasure to serve on the Commission under you.96

“There goes the best politician in Washington,” Cleveland said, after bidding him farewell.97

All the abrasiveness of recent months melted away as Roosevelt joyfully contemplated his achievements in Washington and the challenge awaiting him in New York. He hated to leave the capital at a time when the trees were dense with blossom, and the slow Southern girls—so different from their quick-stepping Northern sisters!—were strolling through the streets in their light summer dresses, to the sound of banjos down by the river. He was sorry to say good-bye to nice, peevish old Henry Adams, to “Spwing-Wice of the Bwitish Legation,”98 and Lodge and Reed and Hay and all “the pleasant gang” who breakfasted at 1603 H Street. He would miss the Smithsonian, to which he affectionately donated his pair of Minnesota skis, along with several specimens from the long-defunct Roosevelt Museum of Natural History.99 Most of all, perhaps, he would miss the Cosmos Club, the little old house on Madison Place where leaders of Washington’s scientific community liked to gather for polysyllabic discussions. Ever since Roosevelt’s first days as Civil Service Commissioner, when he astonished twenty Cosmos members by effortlessly sorting a pile of fossil-bones into skeletons, with running commentaries on the life habits of each animal, he had been a star attraction at the club.100 In later life Rudyard Kipling, looking back on these “spacious and friendly days” in Washington, would remember Roosevelt dropping by the Cosmos and pouring out “projects, discussions of men and politics, and criticisms of books” in a torrential stream, punctuated by bursts of humor. “I curled up in the seat opposite, and listened and wondered, until the universe seemed to be going round, and Theodore was the spinner.”101