A strain of music closed the tale,

A low, monotonous, funeral wail,

That with its cadence, wild and sweet,

Made the long Saga more complete.

![]()

THEODORE ROOSEVELT’S FORMAL SERVICES to the nation as Vice-President lasted exactly four days, from 4 March to 8 March 1901.1 The Senate then adjourned until December, and Roosevelt was free to lay down his gavel and return to Oyster Bay. Before doing so he asked Associate Justice Edward D. White for advice on resuming his long-abandoned legal studies in the fall2—a sure sign of confusion and pessimism about the future.

It was pleasant, all the same, to relax with his numerous children after so many busy years. Sagamore was at its most beautiful that spring, with spreading dogwood, blooming orchards, and the “golden leisurely chiming of the wood thrushes chanting their vespers” down below.

An old friend, Fanny Smith Dana, visited him that spring. “As always, Theodore was vital and stimulating, but there was a difference. The spur of combat was absent.”3 In May he escorted Edith north to the opening of the Pan-American Exposition in Buffalo, and in July and August made two further restless trips West, to Colorado and Minnesota. “I always told you I was more of a Westerner than an Easterner,” he explained, rather vaguely, to Lincoln Steffens.4 In early fall his social schedule began to pick up, and on 4 September 1901, he arrived in Rutland, Vermont, for a short series of speaking engagements.

“He has a man of destiny behind him.”

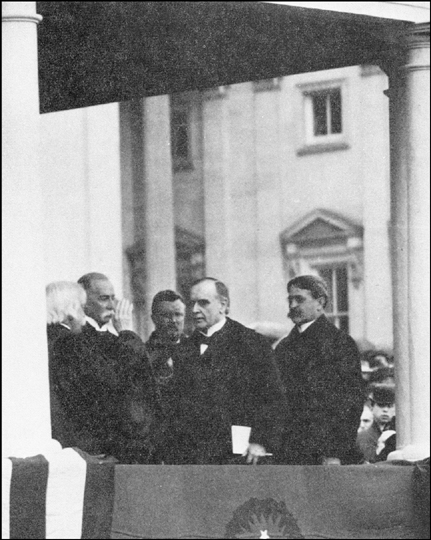

The second Inauguration of William McKinley, 4 March 1901. (Illustration epl.1)

Sometime that day Roosevelt’s eastbound train crossed the tracks of the Presidential Special, bearing William McKinley north to the exposition in Buffalo.5

![]()

TWO DAYS LATER, on Friday, 6 September, the Vice-President attended an estate luncheon of the Vermont Fish and Game League on Isle La Motte, in Lake Champlain.6 With a thousand other guests he sat under a great marquee and ate and drank leisurely until about four o’clock. Then, leaving the crowd to follow him, he strolled across the lawns to the home of his host, ex-Governor Nelson W. Fisk. An impromptu reception was planned inside, at which any member of the league might come forward and shake the Vice-President’s hand.

Inside the house a telephone shrilled. While Fisk answered it, Roosevelt stood in the sun chatting to one or two companions. Then Fisk appeared at the door and beckoned him in wordlessly. To the puzzlement of other people on the lawn, the door was locked as soon as the Vice-President had stepped through it. Keys were heard turning in all the other doors in the house, and volunteer guards stood at the windows. They would answer no questions as to what was being discussed on the telephone. Yet somehow a realization swept through the crowd that the President had been shot, perhaps killed.

Meanwhile Roosevelt had put down the receiver and was addressing the house company. “Gentlemen, I am afraid that there is little ground for hope that the report is untrue. It comes now from two sources and appears to be authentic.” He gave them the facts. A young anarchist had approached the President in Buffalo’s Temple of Music with a handkerchief wrapped around his right hand. McKinley, thinking it a bandage, had reached to shake his left hand, whereupon a revolver concealed in the handkerchief blasted twobullets into the President’s breast and belly. He was now undergoing exploratory surgery, and the assailant, whose name was Leon Czolgosz, had been apprehended. “Don’t let them hurt him,” McKinley had murmured before lapsing into deep shock.7

While Senator Redfield Proctor apprised the crowd of the details, Roosevelt and his aides left immediately for Buffalo.

McKinley’s condition next morning, Saturday, 7 September, gave encouragement to his attending physicians. The breast wound was no more than a gash on the ribs, but the abdominal penetration was deep and serious. Both walls of the stomach had been torn open; the bullet was buried somewhere irretrievable. The most dangerous threat was of gangrene; however there were no visible signs of sepsis.8

McKinley was a man of strong constitution, and he rallied amazingly over the weekend. By Tuesday, 10 September, his condition was so improved that Roosevelt (who had comported himself with extraordinary dignity and concern throughout) was told he no longer need remain at the presidential bedside. In fact it would be best, from the point of view of publicity, if he quit Buffalo altogether.9

The Vice-President left that afternoon for a short vacation in the Adirondacks, where Edith and the children were waiting for him in a mountain cabin.

![]()

HE COULD NOT HAVE CHOSEN a destination more likely to reassure the American people that the national crisis was over, and that his services would not be required in some dread emergency. The cabin stood at Camp Tahawus, “the most remote human habitation in the Empire State,” on the slopes of Mount Marcy, highest peak in the Adirondacks. Half a century before, Tahawus had been a little mining community; now, thanks to the enterprise of Roosevelt’s wealthy friend and fellow conservationist James McNaughton, it had been transformed into a luxury resort for hunters, fishermen, and climbers.10

On arrival at the camp Roosevelt stopped at Tahawus Club, the old village lodging-house, and arranged for two ranger guides to accompany him on an ascent of the mountain, beginning on 12 September.11 This done, he went on up the slope to his cabin in the trees.

By nightfall on the twelfth, Roosevelt and his climbing party, consisting of Edith, Kermit, ten-year-old Ethel, a governess, James McNaughton, three other friends, and the two rangers, were at Lake Colden, altitude 3,500 feet, where they spent the night in two cabins. The next morning, Friday the thirteenth, was cold and gray: an impenetrable drizzle screened off the mountain above them, and the women and children elected to return to Tahawus. But Roosevelt, who could never resist the highest peak in any neighborhood, in any weather, exhorted his elder male companions to continue climbing with him. Leaving one guide to escort the downward party, he ordered the other to lead his own up into the mists. At about nine o’clock they set off along the cold, slippery trail.12

![]()

AT 11:52 A.M. ROOSEVELT found himself on a great flat rock, gazing out (could he but see it!) across the whole of New York State. Rolling fog obscured everything but nearer grass and shrubs, yet the sense of being the highest man for hundreds of miles around, cherished by all instinctive climbers, was no doubt pleasing to him. As if in further reward, the clouds unexpectedly parted, sunshine poured down on his head, and for a few minutes a world of trees and mountains and sparkling water lay all around, stretching to infinity.13

Roosevelt was not a reflective man, nor was he prone now in his early middle age (he would be forty-three in six weeks’ time) to long for the past as much as he used to. But the news of President McKinley’s accident, and the unavoidable horrid thrill of being, if only for a few hours, the likely next President of the United States, seems to have temporarily awakened his youthful tendency to nostalgia. Writing to Jacob Riis a few days before, he had said that “a shadow” had fallen across his path, separating him from “those youthful days” which he would never see again.14

Here, if ever, was an opportunity to look around him at all these lower hills, and to think of the hills he had himself climbed in life. Pilatus as a boy; Katahdin as an underclassman; Chestnut Hill as a young lover; the Matterhorn in the ecstasy of honeymoon; the Big Horns in Wyoming, with their bugling elks; the Capitol Hill in Albany, that freezing January night when he first entered politics; Sagamore Hill, his own fertile fortress, full of his children and crowned with triumphant antlers; the Hill in Washington where he twice laid out John Wanamaker; that lowest yet loftiest of hills in Cuba, where like King Olaf on Smalsor Horn he planted his shield; now this. Would he ever rise any higher? Or was McKinley’s recovery a sign that the final peak he had so long sought would after all be denied him?

Mists rolled in again, and Roosevelt descended five hundred feet to a little lake named Tear-of-the-Clouds, where his party unpacked lunch. It was about 1:25 in the afternoon.15

As he ate his sandwiches he saw below him in the trees a ranger approaching, running, clutching the yellow slip of a telegram.16 Instinctively, he knew what message the man was bringing.