These tribulations are for God’s sake. The sword of Islam is in our hands. If we had not chosen to endure these tribulations, we would not be worthy to be called gazis. We would be ashamed to stand in God’s presence on the day of Judgement.

Mehmet II

There is a fable about Mehmet’s methods of conquest told by the Serbian chronicler Michael the Janissary. In it, the sultan summoned his nobles and ordered “a great rug to be brought and to be spread before them, and in the centre he had an apple placed, and he gave them the following riddle, saying: ‘Can any of you take up that apple without stepping on the rug?’ And they reckoned among themselves, thinking about how that could be, and none of them could get the trick until (Mehmet) himself, having stepped up to the rug took the rug in both hands and rolled it before him, proceeding behind it; and so he got the apple and put the rug back down as it had been before.”

Mehmet now held the moment right for taking the apple. It was obvious to both sides that the final struggle was under way. The sultan hoped that, like a section of wall tottering under the weight of cannon-fire, one last massive assault would collapse all resistance at a stroke. Constantine understood from spies, and possibly from Halil himself, that if they could survive this attack, the siege must be lifted and the church bells could ring for joy. Both commanders gathered for a supreme effort.

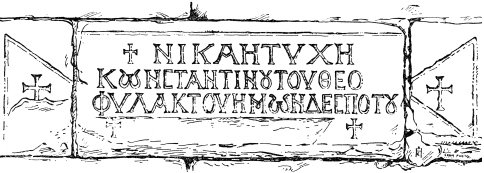

Inscription on the land walls: “The Fortune of Constantine, our God-protected Sovereign, triumphs”

Mehmet propelled himself into a frenzy of activity. In these final days he seems to have been continuously in motion, on horseback among the men, holding audience in the red and gold tent, raising morale, giving orders, promising rewards, threatening punishments, personally supervising the final preparations – above all being seen. The physical presence of the Padishah was held to be an essential inspiration in steadying the morale of the men as they prepared to fight and die. Mehmet knew this was his moment of destiny. Dreams of glory were within his grasp; the alternative was unthinkable failure. He was determined personally to ensure that nothing should be left to chance.

On Sunday morning, May 27, he ordered the guns to open up again. It was probably the heaviest bombardment of the whole siege. All day the great cannon hammered away at the central section of the wall, with the express aim of opening up substantial breaches for a full-scale assault and preventing effective repairs. It seems that massive granite balls struck the wall three times before bringing down a large section. By daylight, under this withering volley of fire, it was impossible to carry out running repairs, but no attempt was made to attack. All day, according to Barbaro, “they did nothing apart from bombard the poor walls and brought a lot of them crashing to the ground, and left half of them badly damaged.” The gaps were getting larger, and Mehmet ensured that it was increasingly difficult to plug them. He wanted to make certain the defenders should have no rest in the days before the final rush.

During the day Mehmet called a meeting of the officer corps outside his tent. The complete command structure assembled to hear their sultan’s words: “the provincial governors and generals and cavalry officers and corps commanders and captains of the rank and file, as well as commanders of a thousand, a hundred or fifty men, and the cavalry he kept around him and the captains of the ships and triremes and the admiral of the whole fleet.” Mehmet suspended in the air before his listeners the image of fabulous wealth which was now theirs for the taking: the hoards of gold in the palaces and houses, the votive offerings and relics in the churches, “fashioned out of gold and silver and precious stones and priceless pearls,” the nobles and beautiful women and boys available for ransom, marriage, and slavery, the graceful buildings and gardens which would be theirs to live in and enjoy. He went on to stress not only the immortal honor that would follow from capturing the most famous city on earth, but also the necessity of doing so. Constantinople remained a palpable threat to the security of the Ottoman Empire so long as it rested in Christian hands. Captured, it would be the stepping-stone to further conquests. He presented the task ahead as now being easy. The land wall was badly shattered, the moat filled in, and the defenders few and demoralized. He was at particular pains to play down the determination of the Italians, whose involvement in the siege was obviously something of a psychological problem for his audience. Almost certainly, although Kritovoulos, a Greek, does not mention it, Mehmet stressed the appeal to holy war – the long-held Islamic desire for Constantinople, the words of the Prophet, and the attractions of martyrdom.

He then laid out the tactics for the battle. He believed, quite rightly, that the defenders were exhausted by constant bombardment and skirmishing. The time had come to bring the full advantage of numbers into play. The troops would attack in relays. When one division was exhausted, a second would replace it. They would simply hurl wave after wave of fresh troops at the wall until the weary defenders cracked. It would take as long as it took and there would be no let-up: “once we have started fighting, warfare will be unceasing, without sleeping or eating, drinking or resting, without any letup, with us pressing on them until we have overpowered them in the struggle.” They would attack the city from all points simultaneously in a coordinated onslaught, so that it was impossible for the defenders to move troops to relieve particular pressure points. Despite the rhetoric, limitless attack was impossible: the practical time frame for a full-scale assault would be finite, compressed into a few hours. A stout resistance would inflict murderous slaughter on the rushing troops; if they failed to overwhelm the defenders quickly, withdrawal would be inevitable.

Precise orders were given to each commander. The fleet at the Double Columns was to encircle the city and tie down the defenders at the sea walls. The ships inside the Horn were to assist in floating the pontoon across the Horn. Zaganos Pasha would then march his troops across from the Valley of the Springs and attack the end of the land wall. Next, the troops of Karaja Pasha would confront the wall by the Royal Palace, and in the center Mehmet would station himself with Halil and the Janissaries for what many considered to be the crucial theater of operations – the shattered wall and the stockade in the Lycus valley. On his right Ishak Pasha and Mahmut Pasha would attempt to storm the walls down toward the Sea of Marmara. Throughout he laid particular emphasis on ensuring the discipline of the troops. They must obey commands to the letter: “to be silent when they must advance without noise, and when they must shout to utter the most bloodcurdling yells.” He reiterated how much hung on the success of the attack for the future of the Ottoman people, and promised personally to oversee it. With these words he dismissed the officers back to their troops.

Later he rode in person through the camp, accompanied by his Janissary bodyguard in their distinctive white headdresses, and his heralds who made the public announcement of the coming attack. The message cried among the sea of tents was designed to ignite the enthusiasm of the men. There would be the traditional rewards for storming a city: “you know how many governorships are at my disposal in Asia and in Europe. Of these I will give the finest to the first to pass the stockade. And I shall pay him the honours which he deserves, and I shall requite him with a position of wealth, and make him happy among the men of our generation.” All major Ottoman battles were preceded by the promise of a graduated series of stated honors designed to spur the men on. There was a matching set of punishments: “but if I see any man lurking in the tents and not fighting at the wall, he will not be able to escape a lingering death.” It was one of the psychological ploys of Ottoman conquest that it bound men into an effective reward system that linked honor and profit to the recognition of exceptional effort. It was implemented by the presence on the battlefield of the sultan’s messengers, the chavushes, a body of men who reported directly to the sultan. Their single account of an act of bravery could lead to instant promotion. The men knew that great acts could be rewarded.

Mehmet went further. In accordance with the dictates of Islamic law, it was decreed that since the city had not surrendered, it would be given to the soldiers for three days of plunder. He swore by God, “by the four thousand prophets, by Muhammad, by the soul of his father and his children and by the sword he strapped on, that he would give them everything to sack, all the people, men and women, and everything in the city, both treasure and property, and that he would not break his promise.”

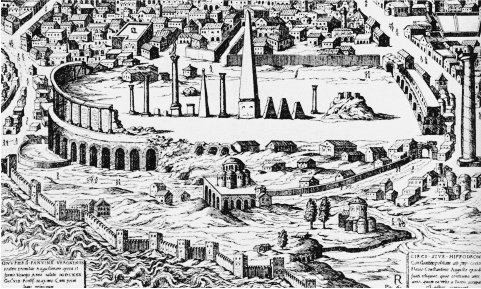

The prospect of the Red Apple, rich in plunder and marvels, was a direct appeal to the very soul of the nomadic raider, an archetype of the horseman’s longing for the wealth of cities. After seven weeks of suffering in the spring rain, it must have struck the men with the force of hunger. To a large extent the city they imagined did not exist. The Constantinople conjured by Mehmet had been ransacked by Christian crusaders two and a half centuries earlier. Its fabulous treasures, its gold ornaments, its jewel-encrusted relics, had largely gone in the catastrophe of 1204 – melted down by Norman knights or shipped off to Venice with the bronze horses. What was left in May 1453 was an impoverished, shrunken shadow of its former self, whose main wealth was now its people. “Once the city of wisdom, now a city of ruins,” Gennadios had said of the dying Byzantium. A few rich men may have had hoards of gold hidden in their houses and the churches still had precious objects, but the city no longer possessed the treasure troves of Aladdin that the Ottoman troops longingly imagined as they stared up at the walls.

City of ruins: the crumbling Hippodrome and empty spaces of the city

Nevertheless the proclamation whipped the listening army into a fever of excitement. Their great shouts were carried to the exhausted defenders watching from the walls. “O, if you had heard their voices raised to heaven,” recorded Leonard, “you would indeed have been paralysed.” The looting of the city was probably a promise that Mehmet had not wanted to make, but it had become the necessary lever for fully winning over the grumbling troops. A negotiated surrender would have prevented a level of destruction that he was hoping to avoid. The Red Apple was not for Mehmet just a chest of war booty to be plundered; it was to be the center of his empire, and he was keen to preserve it intact. With this in mind a stern caveat was attached to the promise: the buildings and walls of the city were to remain the property of the sultan alone; under no circumstances were they to be damaged or destroyed once the city had been entered. The capture of Istanbul was not to be a second sacking of Baghdad, the most fabulous city of the Middle Ages, committed to the flames by the Mongols in 1258.

The attack was fixed for the day after next – Tuesday, May 29. In order to work the soldiers to a pitch of religious zeal and to quash any negative thoughts, it was announced that the following day, Monday, May 28, was to be given over to atonement. The men were to fast during daylight hours, to carry out their ritual ablutions, to say their prayers five times, and to ask God’s aid in capturing the city. The customary candle illuminations were to continue for the next two nights. The mystery and awe that the illuminations, combined with prayers and music, worked on both the men and their enemies were powerful psychological tools, employed to full effect outside the walls of Constantinople.

In the meantime the work in the Ottoman camp went on with renewed enthusiasm. Vast quantities of earth and brushwood were collected ready to fill up the ditch, scaling ladders were made, stockpiles of arrows were collected, wheeled protective screens drawn up. As night fell the city was again ringed by a brilliant circle of fire; the rhythmic chanting of the names of God rose steadily from the camp to the steady beating of drums, the clash of cymbals, and the skirl of the zorna. According to Barbaro the shouting could be heard across the Bosphorus on the coast of Anatolia, “and all us Christians were in the greatest terror.” Within the city it had been the feast day of All Saints, but there was no comfort in the churches, only penitence and continual prayers of intercession.

At the day’s end Giustiniani and his men again set about repairing the damage to the outer wall, but in the brilliantly illuminated darkness the cannonfire continued unabated. The defenders were horribly conspicuous, and it was now, according to Nestor-Iskander, that Giustiniani’s personal luck started to run out. As he directed operations, a fragment of stone shot, probably a ricochet, struck the Genoese commander, piercing his steel breastplate and lodging in his chest. He fell to the ground and was carried home to bed.

It is difficult to overestimate the importance of Giustiniani to the Byzantine cause. From the moment that he had stepped dramatically onto the quayside in January 1453 with 700 skilled fighters in shining armor, Giustiniani had been an iconic figure in the defense of the city. He had come voluntarily and at his own expense, “for the advantage of the Christian faith and for the honour of the world.” Technically skillful, personally brave, and utterly tireless in his defense of the land walls, he alone had been able to command the loyalty of both the Greeks and Venetians – to the extent that they were forced to make an exception to their general hatred of the Genoese. The construction of the stockade was a brilliant piece of improvisation whose effectiveness chipped away at the morale of the Ottoman troops. The unreliable testimony of his fellow countryman, Leonard of Chios, suggests that Mehmet was moved to exasperated admiration of his principal opponent and tried to bribe him with a large sum of money. Giustiniani was not to be bought. Despair seems to have gripped the defenders at the felling of their inspirational leader. Wall repairs were abandoned in disarray. When Constantine was told, “right away his resolution vanished and he melted away into thought.”

At midnight the shouting again suddenly died down and the fires were extinguished. Silence and darkness fell abruptly over the tents and banners, the guns, horses, and ships, the calm waters of the Horn, and the shattered walls. The doctors who watched over the wounded Giustiniani “treated him all night long and laboured in sustaining him.” The people of the city enjoyed little rest.

Mehmet spent Monday, May 28, making final arrangements for the attack. He was up at dawn giving orders to his gunners to prepare and aim their guns on the wrecked parts of the wall, so that they might target the vulnerable defenders when the order was given later in the day. The leaders of the cavalry and infantry divisions of his guard were summoned to receive their orders and were organized into divisions. Throughout the camp the order was given, to the sound of trumpets, that all the officer corps should stand to their posts under pain of death, in readiness for tomorrow’s attack.

When the guns did open up, “it was a thing not of this world,” according to Barbaro, “and this they did because it was the day for ending the bombardment.” Despite the intensity of the cannonflre there were no attacks. The only other visible activity was the steady collection of thousands of long ladders, which were brought up close to the walls, and a huge number of wooden hurdles, which would provide protection for the advancing men as they struggled to climb the stockade. Cavalry horses were brought in from pasture. It was a late spring day and the sun was shining. Within the Ottoman camp the men went about their preparations: fasting and prayer, sharpening blades, checking fastenings on shields and armor, resting. A mood of introspection stilled the troops as they steadied themselves for the final assault. The religious quietness and discipline of the army unnerved the watchers on the walls. Some hoped that the lack of activity was a preparation for withdrawal; others were more realistic.

Mehmet had worked hard on the morale of his men, tuning their responses over several days through cycles of fervor and reflection that were designed to build morale and distract from internal doubt. The mullahs and dervishes played a key role in creating the right mentality. Thousands of wandering holy men had come to the siege from the towns and villages of upland Anatolia, bringing with them a fervent religious expectation. In their dusty robes they moved about the camp, their eyes alight with excitement. They recited relevant verses from the Koran and the Hadith and told tales of martyrdom and prophecy. The men were reminded that they were following in the footsteps of the companions of the Prophet killed at the first Arab siege of Constantinople. Their names were passed from mouth to mouth: Hazret Hafiz, Ebu Seybet ul-Ensari, Hamd ul-Ensari, and above all Ayyub, whom the Turks called Eyüp. The holy men reminded their listeners, in hushed tones, that to them fell the honor of fulfilling the word of the Prophet himself:

The Prophet said to his disciples: “Have you heard of a city with land on one side and sea on the other two sides?” They replied: “Yes, O Messenger of God.” He spoke: “The last hour [of Judgment] will not dawn before it is taken by 70,000 sons of Isaac. When they reach it, they will not do battle with arms and catapults but with the words ‘There is no God but Allah, and Allah is great.’ Then the first sea wall will collapse, and the second time the second sea wall, and the third time the wall on the land side will collapse, and, rejoicing, they will enter in.”

The words attributed to the Prophet may have been spurious, but the sentiment was real. To the army fell the prospect of completing a messianic cycle of history, a persistent dream of the Islamic peoples since the birth of Islam itself, and of winning immortal fame. And for those killed in battle blessed martyrdom and the prospect of paradise lay ahead: “Gardens watered by running streams, where they shall dwell forever; spouses of perfect chastity: and grace from God.”

It was a heady mixture, but there were those in the camp, including Sheik Akshemsettin himself, who were extremely realistic about the authentic motivation of some of the troops. “You well know,” he had written to Mehmet earlier in the siege, “that most of the soldiers have in any case been converted by force. The number of those who are ready to sacrifice their lives for the love of God is extremely small. On the other hand, if they glimpse the possibility of winning booty they will run towards certain death.” For them too, there was encouragement in the Koran: “God has promised you rich booty, and has given you this with all promptness. He has stayed your enemies’ hands, so that He may make your victory a sign to true believers and guide you along a straight path.”

Mehmet embarked on a final restless tour of inspection. With a large troop of cavalry he rode to the Double Columns to give Hamza instructions for the naval assault. The fleet was to sail around the city, bringing the ships within firing range to engage the defenders in continuous battle. If possible, some of the vessels should be run aground and an attempt made to scale the sea walls, although the chances of success in the fast currents of the Marmara were not considered great. The fleet in the Horn was given similar orders. On the way back he also stopped outside the chief gate of Galata and ordered the chief magistrates of the town to present themselves to him. They were sternly warned to ensure that no help was given to the city on the following day.

In the afternoon he was again on horseback, making a tour of inspection of the whole army, riding the four miles from sea to sea, encouraging the men, addressing the individual officers by name, stirring them up for battle. The message of “carrot and stick” was reiterated: both great rewards were at hand and terrible punishments for those who failed to obey. They were ordered under pain of death to follow the orders of their officers to the letter. Mehmet probably addressed his sternest words to the impressed and reluctant Christian troops under Zaganos Pasha. Satisfied with these preparations, he returned to his tent to rest.

Within the city a set of matching preparations was under way. Somehow, against the worst fears of Constantine and the doctors, Giustiniani had survived the night. Disturbed and obsessed by the state of the outer wall, he demanded to be carried up to the ramparts to oversee the work again. The defenders set about the business of plugging the gaps once again and made good progress until they were spotted by the Ottoman gunners. At once a torrent of fire forced them to stop. Later it seems that Giustiniani was well enough to take active command of the defenses of the crucial central area once more.

Elsewhere preparations for the final defense were hampered by friction between the various national and religious factions. The deep-rooted rivalries and conflicting priorities of the different interest groups, the difficulty of providing sufficient food, the exhaustion of continuous work, and the shock of bombardment – after fifty-three days of siege, nerves were stretched to the breaking point and disagreements flared into open conflict. As they prepared for the coming attack, Giustiniani and Lucas Notaras nearly came to blows over the deployment of their few precious cannon. Giustiniani demanded that Notaras should hand over the cannon under his control for the defense at the land walls. Notaras refused, believing that they might be required to defend the sea walls. A furious row took place. Giustiniani threatened to run Notaras through with his sword.

A further quarrel broke out about provisioning the land walls. The shattered battlements needed to be topped by effective defensive structures to provide protection against enemy missiles. The Venetians set about making mantlets – wooden hurdles – in the carpenters’ workshops of their quarter, the Plateia, down by the Horn. Seven cartloads of mantlets were collected in the square. The Venetian bailey ordered the Greeks to take them the two miles up to the walls. The Greeks refused unless they were paid. The Venetians accused them of greed; the Greeks, who had hungry families to feed and were resentful of the arrogance of the Italians, needed time or money to get food before the end of the day. The dispute rumbled on so long that the mantlets were not delivered until after nightfall, by which time it was too late to use them.

These flaring antagonisms had a deep history. Religious schism, the sacking of Constantinople in the Fourth Crusade, the commercial rivalry of the Genoese and the Venetians – all contributed to the accusations of greed, treachery, idleness, and arrogance that were hurled back and forward in the tense final days. But beneath this surface of discord and despair, there is evidence that all sides generally did their best for the common defense on May 28. Constantine himself spent the day organizing, imploring, rallying the citizens, and the assorted defenders – Greek, Venetian, Genoese, Turkish, and Spanish – to work together for the cause. Women and children toiled throughout the day, lugging stones up to the walls to hurl down on the enemy. The Venetian bailey put out a heartfelt plea “that all who called themselves Venetians should go to the land walls, firstly out of love for God, then for the good of the city and for the honour of all Christendom and that they should all stand to their posts and be willing to die there with a good heart.” In the harbor the boom was checked and all the ships stood to in battle order. Across the water, the people of Galata watched the preparations for a final struggle with growing concern. It seems likely that the Podesta also put out a last, clandestine appeal to the men of the town to cross the Horn in secret and join the defense. He realized that the fate of the Genoese enclave was now dependent on Constantinople’s survival.

In contrast to the silence of the Ottoman camp, Constantinople was animated by noise. All day church bells were rung and drums and wooden gongs beaten to rally the people to make final preparations. The endless cycle of prayers, services, and cries of intercession had intensified after the terrible omens of the previous days. They reached a mighty crescendo on the morning of May 28. The religious fervor within the city matched that on the plain outside. Early in the morning a great procession of priests, men, women, and children formed outside St. Sophia. All the most holy icons of the city were brought out from their shrines and chapels. As well as the Hodegetria, whose previous procession had proved so ill-omened, they carried forth the bones of the saints, the gilded and jeweled crosses containing fragments of the True Cross itself, and an array of other icons. The bishops and priests in their brocade vestments led the way. The laity walked behind, penitent and barefoot, weeping and beating their chests, asking absolution for sins and joining in the singing of the psalms. The procession went throughout the city and along the full length of the land walls. At each important position, the priests read the ancient prayers that God would protect the walls and give victory to His faithful people. The bishops raised their crosiers and blessed the defenders, sprinkling them with holy water from bunches of dried basil. For many it was a day of fasting also, broken only at sunset. It was the ultimate method of raising the defenders’ morale.

The emperor probably joined the procession himself, and when it was over he called together the leading nobles and commanders from all the factions within the city to make a last appeal for unity and courage. His speech was the mirror image of Mehmet’s. It was witnessed by Archbishop Leonard and recorded in his own way. Constantine addressed each group in turn, appealing to their own interests and beliefs. First he spoke to his own people, the Greek residents of the city. He praised them for their stout defense of their home for the past fifty-three days and entreated them not to be afraid of the wild shouts of the untrained mob of “evil Turks”: their strength lay “in God’s protection” but also in their superior armor. He reminded them of how Mehmet had started the war by breaking a treaty, building a fortress on the Bosphorus, “pretending peace.” In an appeal to home, religion, and the future of Greece, he reminded them that Mehmet intended to capture “the city of Constantine the Great, your homeland, the support of Christian fugitives and the protection of all the Greeks, and to profane the sacred temples of God by turning them into stables for his horses.”

Turning first to the Genoese, then the Venetians, he praised them for their courage and commitment to the city: “you have decorated this city with great and noble men as if it were your own. Now raise your lofty souls for this struggle.” Finally he addressed all the fighting men as a body, begged them to be utterly obedient to orders, and concluded with an appeal for earthly or heavenly glory almost identical to that of Mehmet: “know that today is your day of glory, on which, if you shed even one drop of blood you will prepare for yourself a martyr’s crown and immortal glory.” These sentiments had their desired effect on the audience. All present were encouraged by Constantine’s words and swore to stand firm in the face of the coming onslaught, that “with God’s help we may hope to gain the victory.” It seems that they all resolved to put aside their personal grievances and problems and to join together for the common cause. Then they departed to take up their posts.

In reality Constantine and Giustiniani knew how thinly their forces were now stretched. After seven weeks of attritional fighting it is likely that the original 8,000 men had dwindled to about 4,000, to guard a total perimeter of twelve miles. Mehmet was probably right when he had told his men that in places there were “only two or three men defending each tower, and the same number again on the ramparts between the towers.” The length of the Golden Horn, some three miles, which might be subject to attack by the Ottoman ships at the Springs and by troops advancing over the pontoon bridge, was guarded by a detachment of 500 skilled crossbowmen and archers. Beyond the chain, right around the seawalls, another five miles, only a single skilled archer, crossbowman, or gunner was assigned to each tower, backed up by an untrained band of citizens and monks. Particular parts of the sea walls were allotted to different groups – Cretan sailors held some towers, a small band of Catalans another. The Ottoman pretender Orhan, the sultan’s uncle, held a stretch of wall overlooking the Marmara. His band was certain to fight to the death if it came to a final struggle. For them, surrender would not be an option. In general, however, it was reckoned that the sea wall was well protected by the Marmara currents and that all the men who could possibly be spared must be sent to the central section of the land wall. It was obvious to everyone that the most concerted assault must come in the Lycus valley, between the Romanus and the Charisian gates, where the guns had destroyed sections of the outer wall. The last day was given to making all possible repairs to the stockade and to assigning troops to its defense. Giustiniani was in charge of the central section with 400 Italians and the bulk of the Byzantine troops – some 2,000 men in all. Constantine also set up his headquarters in this section to ensure full support.

By midafternoon the defenders could see the troops gathering beyond their walls. It was a fine afternoon. The sun was sinking in the west. Out on the plain the Ottoman army started to deploy into regimental formations, turning and wheeling, drawing up its battle standards, filling the horizon from coast to coast. In the vanguard, men continued to work to fill in the ditches, the cannon were advanced as close as possible, and the inexorable accumulation of scaling equipment continued unchecked. Within the Horn the eighty ships of the Ottoman fleet that had been transported overland prepared to float the pontoon bridge up close to the land walls; and beyond the chain, the larger fleet under Hamza Pasha encircled the city, sailing past the point of the Acropolis and around the Marmara shore. Each ship was loaded with soldiers, stone-throwing equipment, and long ladders as high as the walls themselves. The men on the ramparts settled down to wait, for there was still time to spare.

Late in the afternoon the people of the city, seeking religious solace, converged for the first time in five months on the mother church of St. Sophia. The dark church, which had been so conspicuously boycotted by the Orthodox faithful, was filled with people, anxious, penitent, and fervent, and for the first time since the summer of 1064, in the ultimate moment of need, it seems that Catholic and Orthodox worshipped together in the city, and the 400-year-old schism and the bitterness of the Crusades were put aside in a final service of intercession. The huge space of Justinian’s 1,000-year-old church glittered with the mysterious light of candles and reverberated with the rising and falling notes of the liturgy. Constantine took part in the service. He occupied the imperial chair at the right side of the altar and partook of the sacraments with great fervor, and “fell to the ground, and begged God’s loving kindness and forgiveness for their transgressions.” Then he took leave of the clergy and the people, bowed in all directions – and left the church. “Immediately,” according to the fervent Nestor-Iskander, “all clerics and people present cried out; the women and children wailed and moaned; their voices, I believe, reached to heaven.” All the commanders returned to their posts. Some of the civilian population remained in the church to take part in an all-night vigil. Others went to hide. People let themselves down into the echoing darkness of the great underground cisterns, to float in small boats among the columns. Above ground, Justinian still rode on his bronze horse, pointing defiantly to the east.

As evening fell, the Ottomans went to break their fast in a shared meal and to prepare themselves for the night. The prebattle meal was a further opportunity to build group solidarity and a sense of sacrifice among the soldiers gathered around the communal cooking pots. Fires and candles were lit, if anything larger than on the previous two nights. Again the criers swept through, accompanied by pipes and horns, reinforcing the twin messages of prosperous life and joyful death; “Children of Muhammad, be of good heart, for tomorrow we shall have so many Christians in our hands that we will sell them, two slaves for a ducat, and will have such riches that we will all be of gold, and from the beards of the Greeks we will make leads for our dogs, and their families will be our slaves. So be of good heart and be ready to die cheerfully for the love of our Muhammad.” A mood of fervent joy passed through the camp as the excited prayers of the soldiers slowly rose to a crescendo like the breaking of a mighty wave. The lights and the rhythmical cries froze the blood of the waiting Christians. A massive bombardment opened up in the dark, so heavy “that to us it seemed to be a very inferno.” And at midnight silence and darkness fell on the Ottoman camp. The men went in good order to their posts “with all their weapons and a great mountain of arrows.” Pumped up by the adrenaline of the coming battle, dreaming of martyrdom and gold, they waited in total silence for the final signal to attack.

There was nothing left to be done. Both sides understood the climactic significance of the coming day. Both had made their spiritual preparations. According to Barbaro, who of course gave the final say in the outcome to the Christian god, “and when each side had prayed to his god for victory, they to theirs and we to ours, our Father in Heaven decided with his Mother who should be successful in this battle that would be so fierce, which would be concluded next day.” According to Sad-ud-din, the Ottoman troops, “from dusk till dawn, intent on battle … united the greatest of meritorious works … passing the night in prayer.”

There is an afterword to this day. One of the chronicles of George Sphrantzes sees Constantine riding through the dark streets of the city on his Arab mare and returning late at night to the Blachernae Palace. He called his servants and household to him and begged them for forgiveness, and thus absolved, according to Sphrantzes, “the Emperor mounted his horse and we left the palace and began to make the circuit of the walls in order to rouse the sentries to keep watch alertly and not lapse into sleep.” Having checked that all was well, and that the gates were securely locked, at first cockcrow they climbed the tower at the Caligaria Gate, which commanded a wide view over the plain and the Golden Horn, to witness the enemy preparations in the dark. They could hear the wheeled siege towers creaking invisibly toward the ramparts, long ladders being dragged over the pounded ground, and the activity of many soldiers filling in the ditches beneath the shattered walls. To the south, on the glimmering Bosphorus and the Marmara the outlines of the larger galleys could be discerned as distant, ghostly shapes moving into position beyond the bulking dome of St. Sophia, while within the Horn the smaller fustae worked to float the pontoon bridge over the straits and to maneuver close to the walls. It is a haunting, introspective moment and an enduring image of the long-suffering Constantine – the noble emperor and his faithful friend standing on the outer tower listening to the ominous preparations for the final attack, the world dark and still before the moment of final destiny. For fifty-three days their tiny force had confounded the might of the Ottoman army; they had faced down the heaviest bombardment in the Middle Ages from the largest cannon ever built – an estimated 5,000 shots and 55,000 pounds of gunpowder; they had resisted three full-scale assaults and dozens of skirmishes, killed unknown thousands of Ottoman soldiers, destroyed underground mines and siege towers, fought sea battles, conducted sorties and peace negotiations, and worked ceaselessly to erode the enemy’s morale – and they had come closer to success than they probably knew.

This scene is accurate in geographical and factual detail; the guards on the highest ramparts of the city could hear the Ottoman troops maneuvering in the darkness below the walls and would have commanded a wide view over both land and sea, but we have no idea if Constantine and Sphrantzes were actually there. The account is possibly an invention, concocted a hundred years later by a priest with a reputation for forgery. What we do know is that at some point on May 28, Constantine and his minister parted, and that Sphrantzes had a presentiment of this day and its meaning. The two men were lifelong friends. Sphrantzes had served his master with a faithfulness conspicuously absent among those who surrounded the emperor in the quarrelsome final years of the Byzantine Empire. Twenty-three years earlier, he had saved Constantine’s life at the siege of Patras. He had been wounded and captured for his pains, and had languished in leg irons in a verminous dungeon for a month before being released. He had undertaken endless diplomatic missions for his master over a thirty-year period, including a fruitless three-year embassy around the Black Sea in search of a wife for the emperor. In return Constantine made Sphrantzes governor of Patras, had been the best man at his wedding, and the godfather of his children. Sphrantzes had more at stake than many during the siege: he had his family with him in the city. Whenever the two men parted on May 28 it must have been with foreboding on Sphrantzes’s part. Two years earlier to the day he had had a premonition while away from Constantinople: “On the same night of May 28 [1451] I had a dream: it seemed to me that I was back in the City; as I made a motion to prostrate myself and kiss the Emperor’s feet, he stopped me, raised me, and kissed my eyes. Then I woke up and told those sleeping by me: ‘I just had this dream. Remember the date.’”