In the spring of 1186, with the worst of his illness behind him, Saladin–now some forty-eight years old–returned to Damascus. Much of the remainder of that year was given over to his protracted convalescence, and the calmer recreations of theological debate, hawking and hunting, as his physical vitality slowly rekindled. That summer, one marked distraction was provided by the prediction of an impending apocalypse. For decades, astrologers had foretold that, on 16 September 1186, a momentous planetary alignment would stir up a devastating wind storm, scouring the Earth of life. This bleak prophecy had circulated among Muslims and Christians alike, but the sultan nonetheless thought it ridiculous. He made a point of holding a candlelit, open-air party on the appointed night of disaster, even as ‘feeble-mind[ed]’ fools huddled in caves and underground shelters. Needless to say, the evening passed without event; indeed, one of his companions pointedly remarked that ‘we never saw a night as calm as that’.

While his health gradually improved, Saladin looked to reorganise the balance and distribution of power within what could now be termed his Ayyubid Empire. One priority was the promotion of his eldest son al-Afdal as primary heir. The young princeling, now around sixteen, was brought north from Egypt to Syria. Entering Damascus to celebrations fit for a sultan, al-Afdal became nominal overlord of the city, although in the years to come Saladin often kept him by his side, tutoring him in the arts of leadership, politics and war. Two of Saladin’s younger sons were similarly rewarded. Uthman, aged fourteen, was appointed ruler of Egypt, and the sultan’s trusted brother al-Adil returned from Aleppo to the Nile region to act as the young boy’s guardian and governor. Aleppo itself passed to the thirteen-year-old al-Zahir. The only problem spawned by this extensive reshuffle was Saladin’s nephew Taqi al-Din. As governor of Egypt since 1183, he had shown worrying tendencies towards independent action. With the aid of Qaragush (whom Saladin had appointed to oversee the Cairene court in 1169), Taqi al-Din had laid plans for a campaign westwards along the North African coast that would have deprived the sultan of valuable troops. Rumours also abounded that, during the sultan’s illness, Taqi al-Din had been preparing to declare his autonomy. In autumn 1186, Isa, ever the consummate diplomat, was tasked with the delicate mission of persuading him to relinquish his hold on Egypt and return to Syria. Arriving unexpectedly at Cairo, Isa was initially greeted with prevarication, but then apparently advised Taqi al-Din to ‘Go wherever you want.’ This seemingly neutral statement possessed an icily threatening undertone, and Saladin’s nephew soon left for Damascus, where he was welcomed back into the fold and rewarded with his former lordship at Hama and further lands in the newly subdued region of Diyar Bakr.63

The question of Taqi al-Din’s continued subservience reflected a wider issue. To sustain his burgeoning empire, Saladin relied upon the support of his wider family, but the sultan was also determined to protect the interests of his sons, the direct perpetuators of the Ayyubid bloodline. Saladin had to achieve a delicate balance–he needed to harness the drive and ambition of kinsmen like Taqi al-Din, because their energy was vital to the continued preservation and expansion of the realm; but at the same time, their independence had to be curbed. In Taqi al-Din’s case, Saladin hoped to ensure loyalty by offering his nephew the prospect of continued advancement in Upper Mesopotamia.

ISLAM UNITED?

Saladin’s attempts to shape the dynastic fortunes of the Ayyubid Empire in 1186 were, to some extent, a direct function of the increased power and territory he had now accumulated. Since emerging as a political and military force in 1169, he had masterminded the subjugation of Near Eastern Islam, extending his authority over Cairo, Damascus, Aleppo and large stretches of Mesopotamia. The Fatimid caliphate’s abolition had brought the crippling division between Sunni Syria and Shi‘ite Egypt to an end, ushering in a new era of pan-Levantine Muslim accord. These achievements, unparalleled in recent history, surpassed even those of Nur al-Din. On the face of it, Saladin had united Islam from the Nile to the Euphrates; his coinage, circulating throughout his realm and far beyond, now bore the inscription ‘the sultan of Islam and the Muslims’, stark proclamation of his all-encompassing, almost hegemonic authority. This image has often been accepted by modern historians–an attitude typified by one scholar’s recent assertion that after 1183 ‘the rule of all Syria and Egypt was in [Saladin’s] hands’.64

Yet the notion that Saladin now presided over a world of complete and enduring Muslim unity is profoundly misleading. His ‘empire’, constructed through a mixture of direct conquest and coercive diplomacy, was in truth merely a brittle amalgam of disparate and distant polities, many of which were administered by client-rulers whose allegiance might easily falter. Even in Cairo, Damascus and Aleppo–the linchpins of his realm–the sultan had to rely upon the continued fidelity and cooperation of his family, virtues that were never assured. Elsewhere, in the likes of Mosul, Asia Minor and the Jazira, Ayyubid supremacy was largely ephemeral, dependent upon loose alliances and tainted by barely submerged antipathy.

In 1186 the spell held. But it did so only because Saladin had survived his illness and still possessed the wealth, might and influence to manifest his will. In the years that followed, the work of sustaining and governing such a geographically expansive and politically incongruent empire tested the sultan to breaking point. And the struggle to counteract the ingrained centrifugal forces that could so readily rip apart the Ayyubid Empire proved constant and consuming.

Even after some seventeen years of unrelenting struggle, Saladin’s work was not done. Amidst the holy war to come, he could call upon a dedicated, loyalist core of battle-hardened troops, but for the most part the sultan stood at the head of a fragile, often restive, coalition, ever conscious that his realm might be disrupted by insurrection, rebellion or cessation. This fact was of paramount importance, for it shaped much of his thinking and strategy, often forcing him to follow the path of least resistance to seek swift, self-perpetuating victories. Contemporaries and modern historians alike have sometimes criticised Saladin’s qualities as a military commander in this later phase of his career, arguing that he lacked the backbone to prosecute costly and prolonged sieges. In fact, he depended upon speed of action and ongoing success to maintain momentum, clear in the knowledge that if the Muslim war machine ground to a halt, it might well collapse.

At a fundamental level, Saladin’s empire had also been forged against the backdrop of jihad; at every step he justified the extension of Ayyubid authority as a means to an end. Unity beneath his banner may have been bought at a heavy price, but he argued that it was directed at one sole purpose: the jihad to drive the Franks from Palestine and liberate the Holy City. This ideological impulse had proved to be an enormously potent instrument, fuelling and legitimising the motor of expansion, but it came at a near-unavoidable cost. Unless Saladin wished to be revealed as a fraudulent despot, all his promises of unbending devotion to the cause must now be fulfilled and the long-awaited war waged. Certainly, in the aftermath of his illness, and what may have been a period of deepening spirituality, the sultan’s promulgation of the jihad became ever more active. Revered Islamic scholars like the brothers Ibn Qudama and Abd al-Ghani, both long-time proponents of Saladin’s cause, were among those who contributed to a quickening of religious fanaticism. In Damascus, and across the realm, religious tracts and poems on the faith, the obligation ofjihad and the overriding devotional significance of Jerusalem all were recited at massed public gatherings with increasing regularity. By the end of 1186, it appears that the sultan had not only recognised the political necessity for an all-out assault on the Latins, but had also embraced the struggle ahead at a personal level. This is borne out by the testimony of one of Saladin’s few critics among contemporary Muslim commentators, the Mosuli historian Ibn al-Athir. Recording a war council from early 1187, the chronicler wrote:

One of [Saladin’s] emirs said to him: ‘The best plan in my opinion is to invade their territory [and] if any Frankish force stands against us, we should meet it. People in the east curse us and say, “He has given up fighting the infidels and has turned his attention to fighting Muslims.” [We should] take a course of action that will vindicate us and stop people’s tongues.’

Ibn al-Athir’s intention was to censure Ayyubid expansionism, while evoking the tide of public pressure and expectation now attendant on the sultan. But he went on to suggest that Saladin experienced a brief, but significant, moment of self-realisation at this meeting. According to Ibn al-Athir, the sultan declared his determination to go to war and then mournfully observed that ‘affairs do not proceed by man’s decision [and] we do not know how much remains of our lives’. Perhaps it was the sultan’s own sense of mortality that moved him to action; whatever the reason, a change does seem to have occurred. Real questions remain about the true extent of his determination to combat the Franks in the long years between 1169 and 1186, but regardless of what had gone before, in 1187 Saladin brought the full force of his empire to bear against the kingdom of Jerusalem. He was now doggedly resolved to bring the Christians to full and decisive battle.65

A KINGDOM UNDONE

This upsurge of Ayyubid aggression coincided with a deepening crisis in Latin Palestine. At some point between May and mid-September 1186 the young King Baldwin V of Jerusalem died, and a rancorous succession dispute erupted. Count Raymond of Tripoli, who had been acting as regent, schemed to seize the throne, but he was outmanoeuvred by Sibylla (Baldwin IV’s sister) and her husband, Guy of Lusignan. Having won the support of Patriarch Heraclius, a large proportion of the nobility and the Military Orders, Sibylla and Guy managed to have themselves crowned and anointed as queen and king. Raymond tried to engineer an outright civil war, proclaiming Humphrey of Toron and his wife Isabella as the rightful monarchs of Jerusalem. But, perhaps mindful of the terrible damage that might be wrought should this claim be pursued, Humphrey declined to step forward.

As king, one of Guy’s first steps was to buy time to restore some sense of order to the realm by renewing the treaty with Saladin until April 1187 in return for some 60,000 gold bezants. Guy was a divisive figure–Baldwin of Ibelin was so disgusted by his elevation that he gave up his lordship and moved to Antioch–and, as king, Guy’s policy of putting family members from Poitou into positions of power caused further unease. To deal with his most powerful enemy, Raymond of Tripoli, Guy seems to have hatched a plan to seize the lordship of Galilee by force. But in response, Raymond took the quite drastic step of seeking protection from Saladin himself. Muslim sources indicate that many of the sultan’s advisers were suspicious of this approach, but that Saladin rightly judged it to be an honest offer of alliance, the product of the desperate division that now afflicted the Franks. To the evident horror of many of his Latin contemporaries, Raymond welcomed Muslim troops into Tiberias, to bolster the town’s garrison, and gave Ayyubid forces licence to travel unhindered through his Galilean lands. At this worst moment, the count perpetrated an act of treason, engendering even greater disunity among the Christians.

Then, in the winter months of 1186 and 1187, Reynald of Châtillon, lord of Kerak, contravened the truce with the Ayyubids by attacking a Muslim caravan travelling through Transjordan on its way from Cairo to Damascus. His motives remain open to debate, but basic greed probably combined with a realisation that Saladin was building towards a major offensive to spur Reynald into action. Certainly in the weeks that followed he made no effort to repair relations, bluntly refusing the sultan’s demands for restitution of the stolen goods. Even without Reynald’s raid, Saladin would almost certainly have refused that spring to renew the truce with Frankish Palestine, so the once popular contention that the lord of Kerak effectively ignited the war to come should probably be discarded. Nonetheless, Reynald’s exploits did reinforce his status as the Muslim world’s abhorred enemy. They also provided Saladin with a clear cause for war further to inflame the heart of Islam.

TO THE HORNS OF HATTIN

In the spring of 1187 Saladin began to amass his forces for an invasion of Palestine. Drawing troops from Egypt, Syria, the Jazira and Diyar Bakr, he assembled a massive army, with some 12,000 professional cavalrymen at its heart, supported by around 30,000 volunteers. One Muslim eyewitness likened them to a pack of ‘old wolves [and] rending lions’, while the sultan himself described how the dust cloud raised when this swarming horde marched ‘dark[ened] the eye of the sun’. Marshalling such a huge force was a feat in itself–a muster point was appointed in the fertile Hauran region south of Damascus and, with soldiers coming from so far afield, the mobilisation took months to complete. The task was overseen by Saladin’s eldest son, al-Afdal, in his first major command role.66

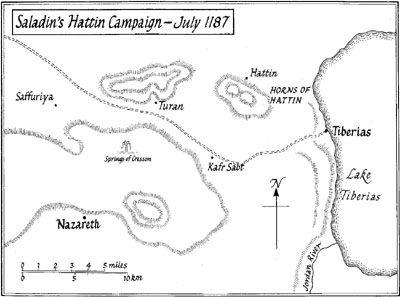

During the early stages of the 1187 campaign, Muslim strategy largely followed the pattern established by Ayyubid attacks in previous years. In April, the sultan marched into Transjordan to link up with forces advancing from North Africa, while prosecuting a series of punitive raids against Kerak and Montreal, including the widespread destruction of crops. But the Franks offered little or no reaction to this provocation. Meanwhile, on 1 May, al-Afdal participated in a combined reconnaissance and raiding mission across the Jordan, testing Tiberias’ defences while Keukburi led a mounted assault force of around seven thousand to scout the Franks’ own preferred muster point at Saffuriya. That night they were spotted by watchmen in Nazareth, and a small party of Templars and Hospitallers, then travelling through Galilee and led by the masters of both orders, decided to give battle. A bloody skirmish followed at the springs of Cresson. Vastly outnumbered, around 130 Latin knights and 300 infantry were killed or captured. The Templar Master Gerard of Ridefort was one of the few to escape, but his Hospitaller counterpart was among the dead. An early blow had been struck, buoying Muslim morale and denting Christian manpower. In the aftermath of this shocking defeat, with the overwhelming Ayyubid threat now impossible to ignore, King Guy and Raymond of Tripoli were begrudgingly reconciled, and the count broke off contact with Saladin.

In late May the sultan himself marched into the Hauran and, as the last troop contingents arrived, moved to the advance staging post of Ashtara, around a day’s march from the Sea of Galilee. He now was joined by Taqi al-Din, returned from northern Syria, where a series of vicious raids had forced the Frankish Prince Bohemond III to agree terms of truce that safeguarded Aleppo from attack. Throughout June, Saladin made his final plans and preparations, carefully drilling his troops and organising battle formations, so that his immense army might function with maximum discipline and efficiency. Three main contingents were formed, with the right and left flanks under Taqi al-Din and Keukburi respectively, and a central force under Saladin’s personal command. At last, on Friday 27 June 1187, the Muslims were ready for war. A crossing of the Jordan was made just south of the Sea of Galilee and the invasion of Palestine began.

In response to the terrible spectre of Islamic attack, King Guy had followed standard Frankish protocol, amassing the Christian army at Saffuriya. Given the unprecedented scale of Saladin’s forces, the king had taken the drastic step of issuing a general call to arms, gathering together practically every last scrap of available fighting manpower in Palestine and using money sent by King Henry II of England to the Holy Land (in lieu of actually crusading) to pay for further mercenary reinforcements. A member of the sultan’s entourage wrote that the Latins came ‘in numbers defying account or reckoning, numerous as pebbles, 50,000 or even more’, but, in reality, Guy probably pulled together around 1,200 knights and between 15,000 and 18,000 infantry and Turcopoles. This was one of the largest hosts ever assembled beneath the True Cross–the Franks’ totemic symbol of martial valour and spiritual devotion–but it was, nonetheless, heavily outnumbered by the Muslim horde. In mustering this army, the Christian king had also taken a considerable gamble, leaving Palestine’s fortresses garrisoned by the barest minimum of soldiers. Should this conflict end in a resounding Latin defeat, the kingdom of Jerusalem would stand all but undefended.67

Saladin’s overriding objective was to achieve just such a decisive victory, drawing the Franks away from the safety of Saffuriya into a full-scale pitched battle on ground of his choosing. But all his experience of war with Jerusalem suggested that the enemy would not easily be goaded into a reckless advance. In the last days of June, the sultan climbed out of the Jordan valley into the Galilean uplands, camping in force at the small village of Kafr Sabt (about six miles south-west of Tiberias and ten miles east of Saffuriya), amidst an expansive landscape of broad plains and undulating hills, peppered with occasional rocky outcrops. He began by testing the enemy, dispatching raiding sorties to ravage the surrounding countryside, while personally reconnoitring Guy’s encampment from a distance. After a few days it became obvious that, as expected, a Latin reaction would only be elicited by bolder provocation.

On 2 July 1187, Saladin laid his trap, leading a dawn assault on the weakly defended town of Tiberias, where Christian resistance soon buckled. Only the citadel held out, proffering precarious refuge to Lady Eschiva, Raymond of Tripoli’s wife. This news raced back to Saffuriya (indeed, the sultan probably allowed Eschiva’s messengers to slip through) bearing entreaties for aid. Saladin’s hope was that the tidings of Tiberias’ stricken condition would force Guy’s hand. As evening fell, the sultan waited to see whether this bait would bring forth his quarry.

Lodged sixteen miles away, the Franks were locked in debate. At a gathering of the realm’s leading nobles, presided over by King Guy, Count Raymond seems to have advised caution and patience. He argued that the risk of direct confrontation with so formidable a Muslim army must be avoided, even at the cost of Tiberias’ fall and his own spouse’s capture. Given time, Saladin’s host would break apart, like so many Islamic forces before it, compelling the sultan to retreat; then Galilee might be recovered, and Eschiva’s ransom arranged. Others, including Reynald of Châtillon and the Templar Master Gerard of Ridefort, offered a different view. Counselling Guy to ignore the traitorous, untrustworthy count, they warned of the shame attendant upon cowardly inaction and urged an immediate move to relieve Tiberias. According to one version of events, the king initially elected to remain at Saffuriya, but, during the night, was persuaded by Gerard to overturn this resolution. In fact, the most decisive factor shaping Latin strategy was probably Guy’s own experience. Confronted with a near-identical choice four years earlier, he had eschewed battle with Saladin and, in consequence, faced derision and demotion. Now, in 1187, he embraced bold pugnacity and, on the morning of 3 July, his army marched forth from Saffuriya.

Once news reached Saladin that the Franks were on the move, he immediately climbed back into the Galilean hills, leaving a small body of troops to maintain the foothold gained in Tiberias. The enemy were advancing eastwards in close order, almost certainly following the broad Roman road that ran from Acre to the Sea of Galilee, with Raymond of Tripoli in the vanguard, the Templars holding the rear and infantry screening the cavalry. A Muslim eyewitness described how ‘wave upon wave’ of them came into sight, remarking that ‘the air stank, the light was dimmed [and] the desert was stunned’ by their advance. Guy of Lusignan’s precise objectives that first day are difficult to divine, but he may, rather optimistically, have hoped to reach Tiberias or at least the shores of the Galilean sea. The sultan was determined to prevent either eventuality. Sending skirmishers forward to harass the Christian column, he held the bulk of his troops on the open plateau north of Kafr Sabt, blocking their path.

Saladin’s Hattin Campaign-July 1187

Saladin rightly grasped that access to water would play a crucial role in this conflict. During high summer, soldiers and horses crossing such arid terrain might easily become dangerously dehydrated. With this in mind, he ordered any wells in the immediate region to be filled in, while ensuring that his own troops were well supplied from the spring at Kafr Sabt and with water ferried on camel-back from the Jordan valley below. Only the ample spring in the village of Hattin remained, on the northern fringe of the escarpment, and the approaches to this were now heavily guarded. The sultan had created what was, in effect, a waterless killing zone.68

Around noon on 3 July, the Franks paused for brief respite beside the village of Turan, whose minor spring could temporarily quench their thirst but was not adequate to the needs of many thousand men. Guy must have believed that he could still break through to Tiberias, for now he turned his back on even this insubstantial sanctuary, continuing the creeping march eastwards. But he had underestimated the sheer weight of numbers at Saladin’s disposal. Holding his central contingent in place to block and hamper the Christian advance, the sultan sent Keukburi’s and Taqi al-Din’s flanking divisions racing to take possession of Turan, barring any possibility of Latin retreat. As the Franks marched on they entered the plateau area so carefully prepared by Saladin for battle and victory. The trap had been sprung.

Near the day’s end, the Christian king hesitated. A committed frontal assault, either east towards the Sea of Galilee or north-east to Hattin, might still have had some chance of success, enabling the Latins to break through to water. But instead, Guy made the forlorn decision to pitch camp in an entirely waterless, indefensible position, a move that was tantamount to an admission of impending defeat. That night the atmosphere in the two armies could not have been more different. Hemmed in by Muslim soldiers ‘so close that they could talk to one another’ and so tightly that even ‘a [fleeing] cat…could not have escaped’, the Franks stood to in the heavy darkness, weakening each hour with terrible, unslaked thirst. The sultan’s troops, meanwhile, filled the air with chants of ‘Allah akhbar’, their courage quickening, ‘having caught a whiff of triumph’, as their leader made final assiduous preparations to deliver his coup de grâce.

Full battle was not joined with the coming of dawn on 4 July. Instead, Saladin allowed the Christians to make pitifully slow progress, probably eastwards along the main Roman road. He was waiting for the heat of the day to rise, maximising the withering effects of dehydration upon the enemy. Then, to further exacerbate their agony, Saladin’s troops set scrub fires, sending clouds of stifling smoke billowing through the faltering Latin ranks. The sultan later chided that this conflagration was ‘a reminder of what God has prepared for them in the next world’ it was certainly enough to prompt pockets of infantry and even some named knights to break ranks and surrender. One Muslim eyewitness remarked, ‘the Franks hoped for respite and their army in desperation sought a way of escape. But at every way out they were barred, and tormented by the heat of war without being able to rest.’69

So far, Muslim skirmishers had continued to harass the enemy, but Saladin’s deadliest weapon had not been unleashed. The preceding night he had distributed some 400 bundles of arrows among his archers and now, around noon, he ordered a full, scything bombardment to begin. As ‘bows hummed and the bowstrings sang’ arrows flew through the air ‘like a swarm of locusts’, killing men and horses, ‘open[ing] great gaps in [the Frankish] ranks’. With the panicking infantry losing formation, Raymond of Tripoli launched a charge towards Taqi al-Din’s contingent to the north-east, but the Muslim troops simply parted to defuse the force of their advance. Finding themselves beyond the fray, Raymond, Reynald of Sidon, Balian of Ibelin and a small group of accompanying knights thought better of returning to the battle and made good their escape. A Muslim contemporary wrote that:

When the count fled, [the Latins’] spirits collapsed and they were near to surrendering. Then they understood that they would only be saved from death by facing it boldly, so they carried out successive charges, which almost drove the Muslims from their positions despite their numbers, had it not been for God’s grace. However, the Franks did not charge and retire without suffering losses and they were gravely weakened…The Muslims surrounded them as a circle encloses its central point.70

In desperation, Guy sought to make a last stand, beating a path north-east towards higher ground, where twinned rocky outcrops–the Horns of Hattin–stood guard over a saddle of land and a bowl-like crater beyond. Here, two thousand years earlier, Iron Age settlers had fashioned a rudimentary hill fort, and its ancient ruined walls still offered the Franks a degree of protection. Defiantly rallying his troops to the True Cross, the king pitched his royal red tent and prepared those knights who remained for a final, desperate attack. The Christians’ only hope now lay in striking directly at the Ayyubid army’s heart–at Saladin himself. For, should the sultan’s yellow banner fall, the tide of battle might turn.

Years later, al-Afdal described how he watched alongside his father, in dread, as twice the Franks launched driving, heavy charges over the saddle of the Horns, spurring their horses directly towards them. On the first occasion they were barely held back, and the prince turned to see that his father ‘was overcome by grief…his complexion pale’. Another eyewitness described the fearful damage inflicted upon the Latins when they were turned back to the Horns, as the pursuing Muslims’ ‘pliant lances danced [and] were fed on entrails’ and their ‘sword blades sucked away their lives and scattered them on the hillsides’. Even so, as al-Afdal recalled:

The Franks regrouped and charged again as before, driving the Muslims back to my father [but we] forced them to retreat once more to the hill. I shouted, ‘We have beaten them!’ but my father rounded on me and said, ‘Be quiet! We have not beaten them until that tent falls.’ As he was speaking to me, the tent fell. The sultan dismounted, prostrated himself in thanks to God Almighty and wept for joy.

With the king’s position overrun, the True Cross was captured and the last shreds of Christian resistance crumbled. Guy and all the Latin kingdom’s nobles, bar those few who had escaped, were taken prisoner, along with thousands of Frankish survivors. Still thousands more had been slain.71

As the clamour of battle subsided, Saladin sat in the entryway to his palatial campaign tent–much of which was still being hurriedly erected–to receive and review his most important captives. Convention suggested that they be treated with honour and, in time, perhaps ransomed, but the sultan called forth two in particular for a personal audience: his adversary, the king of Jerusalem; and his avowed enemy, Reynald of Châtillon. With the pair seated beside him, Saladin turned to Guy, ‘who was dying from thirst and shaking with fear like a drunkard’, graciously proffering a golden chalice filled with iced julep. The king supped deeply upon this rejuvenating elixir, but when he passed the cup to Reynald, the sultan interjected, calmly affirming through an interpreter: ‘You did not have my permission to give him drink, and so that gift does not imply his safety at my hand.’ For, by Arab tradition, the act of offering a guest sustenance was tantamount to a promise of protection. According to a Muslim contemporary, Saladin now turned to Reynald, ‘berat[ing] him for his sins and…treacherous deeds’. When the Frank staunchly refused an offer to convert to Islam, the sultan ‘rose to face him and struck off his head…After he was killed and dragged away, [Guy] trembled with fear, but Saladin calmed his terrors’, assuring him that he would not suffer a similar fate, and the king of Jerusalem was led away into captivity.72

The sultan’s personal secretary, Imad al-Din, summoned forth all his powers of evocation to depict the scene he witnessed as dusk fell over Galilee that evening. ‘The sultan’, he wrote, ‘encamped on the plain of Tiberias like a lion in the desert or the moon in its full splendour’, while ‘the dead were scattered over the mountains and valleys, lying immobile on their sides. Hattin shrugged off their carcasses, and the perfume of victory was thick with the stench of them.’ Picking his way across a battlefield that ‘had become a sea of blood’, its dust ‘stained red’, Imad al-Din witnessed the full horror of the carnage enacted that day.

I passed by them and saw the limbs of the fallen cast naked on the field of combat, scattered in pieces over the site of the encounter, lacerated and disjointed, with heads cracked open, throats split, spines broken, necks shattered, feet in pieces, noses mutilated, extremities torn off, members dismembered, parts shredded.

Even two years later, when an Iraqi Muslim passed by the battle scene, the bones of the dead ‘some of them heaped up and others scattered about’ could be seen from afar.

On 4 July 1187, the field army of Frankish Palestine was crushed. The seizure of the True Cross dealt a crippling blow to Christian morale across the Near East. Imad al-Din proclaimed that ‘the cross was a prize without equal, for it was the supreme object of their faith’, and he believed that ‘its capture was for them more important than the loss of the king and was the gravest blow they sustained in that battle’. The relic was fixed, upside down, to a lance and carried to Damascus.73

So many Latin captives were taken that the markets of Syria were flooded and the price of slaves dropped to three gold dinars. With the exception of Reynald of Châtillon, the only prisoners to be executed were the warriors of the Military Orders. These deadly Frankish ‘firebrands’ were deemed too dangerous to be left alive and were known to be largely worthless as hostages because they usually refused to seek ransom for their release. According to Imad al-Din, ‘Saladin, his face joyful, was sitting on his dais’ on 6 July, when some 100 to 200 Templars and Hospitallers were assembled before him. A handful accepted a final offer of conversion to Islam; the rest were set upon by a ragged band of ‘scholars and Sufis…devout men and ascetics’, unused to acts of violence. Imad al-Din looked on as the murder began.

There were some who slashed and cut cleanly, and were thanked for it; some who refused and failed to act, and were excused; some who made fools of themselves, and others took their places…I saw how [they] killed unbelief to give life to Islam and destroyed polytheism to build monotheism.

Saladin’s victory over the forces of Latin Christendom had been absolute. Just six days later he wrote a letter reliving his achievement, affirming that ‘the gleam of God’s sword has terrified the polytheists’ and ‘the domain of Islam has expanded’. ‘It was’, he asserted, ‘a day of grace, on which the wolf and the vulture kept company, while death and captivity followed in turns’ a moment when ‘dawn [broke] on the night of unbelief’. In time, he erected a triumphal Dome on the Horns of Hattin, the faint, ruined outline of which can still be seen to this day.74

THE FALL OF THE CROSS

In the aftermath of the triumph at Hattin, the door stood open to further Muslim success. The huge loss of Christian manpower on 4 July left the kingdom of Jerusalem in a state of extreme vulnerability, because its cities, towns and fortresses had been all but stripped of their garrisons. Nevertheless, the immense advantage for Islam might still have been squandered had Saladin not demonstrated such focused determination and been in a position to draw upon so deep a well of resources. As it was, through that summer, Frankish Palestine collapsed with barely a whimper.

Tiberias capitulated almost immediately and, within less than a week, Acre–Outremer’s economic hub–had likewise surrendered. In the weeks and months that followed, Saladin directed most of his efforts to sweeping up Palestine’s coastal settlements and ports, and from north to south the likes of Beirut, Sidon, Haifa, Caesarea and Arsuf fell in short order. Meanwhile, the sultan’s brother, al-Adil, who had been alerted immediately after Hattin, swept north from Egypt to seize the vital port of Jaffa, even as other sorties won further successes inland. Ascalon offered stiffer resistance, but by September even that port had been forced into submission, and the fall of Darum, Gaza, Ramla and Lydda followed. Even the Templars eventually gave up their fortress at Latrun, in the Judean foothills en route to Jerusalem, in return for the release of their master, Gerard of Ridefort.

The mercurial speed and broad extent of these successes were due, in part, to the sheer weight of troop numbers and the array of reliable lieutenants, like al-Adil and Keukburi, at Saladin’s disposal. This allowed a number of semi-autonomous Ayyubid war bands to range across the kingdom, significantly increasing the scale and pace of operations and prompting one Latin contemporary to observe that the Muslims spread ‘like ants, covering the whole face of the country’. In truth, however, the shape of events through that summer was largely determined by Saladin’s strategy. Conscious that Islamic unity could only be preserved by momentum in the field, he sought to diffuse Christian resistance by embracing a policy of clemency and conciliation. From the start, generous terms of surrender were offered to Frankish settlements–for instance, even Latin sources admitted that ‘the people of Acre’ were presented with an opportunity to remain in the town, living under Muslim rule, ‘safe and sound, paying the tax which is customary between Christians and Saracens’, while those who wished to leave ‘were given forty days in which to take away their wives and children and their goods’.75

Similar terms seem to have been given to any town or fortress capitulating without resistance and, crucially, these deals were upheld. By keeping his word and not simply ransacking the Levant, Saladin quickly augmented his reputation for integrity and honour. This proved to be a powerful weapon, for when confronted with a choice of hopeless defiance or assured survival, most enemy garrisons surrendered. By this means, the kingdom of Jerusalem was conquered with startling rapidity and at minimal cost to resources. Nonetheless, this approach was not without its drawbacks. From July 1187 onwards, large swathes of the Latin population became refugees and, true to his promises, the sultan allowed them safe conduct to a port, from where, it was expected, they would take sail, perhaps to Syria or the West. In fact, hundreds and then thousands of Franks sought sanctuary in what became Palestine’s sole remaining Frankish port–the heavily fortified city of Tyre.

Saladin was now confronted with a momentous choice. Much of the coastline and interior had been subjugated, but, as the summer waned, it was apparent that only one final push towards conquest might be possible before the onset of winter brought the fighting season to an end. A primary target needed to be identified. In strictly strategic terms, Tyre was the obvious priority: strengthening with each passing day, a bastion of Latin resistance, it offered a lifeline of naval communication with Outremer’s surviving remnants to the north and with the wider Christian world beyond. As such, its continued defiance gifted the enemy a clawing foothold, from which an attempt to rebuild the shattered crusader kingdom might, in time, be launched. Nonetheless, the sultan elected to leave Tyre untouched, twice bypassing the port on his journeys north and south. The Iraqi chronicler Ibn al-Athir saw fit to criticise this decision, arguing that ‘Tyre lay open and undefended from Muslims, and if Saladin had attacked it [earlier in the summer] he would have taken it easily’, and some modern historians have followed this lead, suggesting a lack of foresight on the sultan’s part. Such views depend, in large part, upon wisdom born of hindsight. In early September 1187, Saladin recognised that a protracted siege at Tyre might well bring his entire campaign to a grinding halt, causing the Ayyubid-led Islamic coalition to splinter. Rather than hazard this, the sultan prioritised his core ideological objective, turning inland to direct the full force of his army east, towards Jerusalem.76

To Jerusalem

Isolated amid the Judean hills, the Holy City’s value as a military objective was limited. But decades of preaching and propaganda, engineered by Nur al-Din and Saladin, had reaffirmed Jerusalem’s status as Islam’s most sacred site outside Arabia. The city’s compelling, almost mesmeric, spiritual significance now drew the Muslims on. For a war predicated upon the notion of jihad it was the inevitable and ultimate goal. Having sagely brought the Egyptian navy north to defend Jaffa against Christian counter-attack, and with the Latin outposts defending the eastern approaches to Judea readily subdued, Saladin’s armies descended upon Jerusalem on 20 September 1187. The sultan had come with tens of thousands of troops and heavy siege weapons, ready for a prolonged confrontation, but despite being packed with refugees, the city was desperately short of fighting manpower. Within, Queen Sibylla and Patriarch Heraclius proffered some direction, but the real burden of leadership fell to Balian of Ibelin. After escaping from the disaster at Hattin, Balian had taken refuge in Tyre, but Saladin later granted him safe passage to the Holy City so that Balian might escort his wife Maria Comnena and her children to safety. The understanding was that Balian would remain in Jerusalem for just one night, but upon arrival he was quickly persuaded to renege on this agreement and stay on to organise resistance. With only the barest handful of knights at his disposal, Balian took the expedient step of knighting every noble-born male over the age of sixteen and a further thirty of Jerusalem’s richer citizens. He also sought to strengthen the city’s fortifications wherever possible. In spite of his best efforts, Muslim numerical superiority remained utterly overwhelming.

Saladin began his offensive with an attack on the western walls, but after five days of inconclusive fighting by the Tower of David, shifted focus to the more vulnerable northern sector, around the Damascus Gate–perhaps unwittingly following the precedent set by the First Crusaders. On 29 September, in the face of fierce but ultimately futile resistance, Muslim sappers achieved a major breach in Jerusalem’s walls. The Holy City was now all but defenceless. Hoping for a miracle, Frankish mothers shaved their children’s heads in atonement and the clergy led barefoot processions through the streets, but in practical terms nothing could be done; conquest was inevitable.

Saladin’s intentions in September 1187

The sultan’s reaction to this situation and the precise manner of Jerusalem’s subjugation are immensely significant because they have been instrumental in shaping Saladin’s reputation in history and in popular imagination. Some facts, attested in both Muslim and Christian sources, are irrefutable. Ayyubid troops did not sack the Holy City. Instead, probably on 30 September, terms of Latin surrender were agreed between the sultan and Balian of Ibelin, and, without further spilling of blood, Saladin entered Jerusalem on 2 October 1187. Over the centuries, great weight has been attached to this ‘peaceful’ occupation, and two interconnected notions have gained widespread currency. These events are seen to demonstrate a striking difference between Islam and Latin Christianity, because the First Crusade’s conquest in 1099 involved a brutal massacre, whereas the Ayyubids’ moment of triumph seems to reveal a capacity for temperance and human compassion. It has also been widely suggested that Saladin was only too conscious of the comparison with the First Crusade, being aware of what a negotiated surrender might mean for the image of Islam, for contemporary perceptions of his own career and for the mark he would leave upon history.77

The problem with these views is that they are not supported by the most important contemporary testimony. Two strands of evidence are vital–the account written by Imad al-Din, Saladin’s secretary, who arrived in Jerusalem on 3 October 1187; and a letter from Saladin to the caliph in Baghdad, dating from shortly after Jerusalem’s surrender. The point is not that this material should be trusted simply because it was authored by those closest to events, but rather that it offers an insight into how the sultan himself conceived of and wished to present what happened at the Holy City that autumn.

Both sources indicate that, by the end of September 1187, Saladin intended to sack Jerusalem. According to Imad al-Din, the sultan told Balian at their initial meeting: ‘You will receive neither amnesty nor mercy! Our only desire is to inflict perpetual subjection upon you…We shall kill and capture you wholesale, spill men’s blood and reduce the poor and the women to slavery.’ This is confirmed in Saladin’s letter, which noted that in response to the Franks’ first requests for terms ‘we refused point blank, wishing only to shed the blood of the men and to reduce the women and children to slavery’. At this point, however, Balian threatened that, unless equitable conditions of surrender were agreed, the Latins would fight to the very last man, destroying Jerusalem’s Islamic Holy Places and executing the thousands of Muslim prisoners held inside the city. This was a desperate gambit, but it forced the sultan’s hand, and begrudgingly he agreed a deal. The eyewitness sources reveal an underlying awareness that this accord might be perceived as a sign of Ayyubid weakness. In his letter, Saladin carefully justified his decision, stressing that his emirs had convinced him to accept a settlement so as to avoid any further unnecessary loss of Muslim life and to secure a victory that was already all but won. Imad al-Din reiterated this idea, describing at length a ‘council meeting’, during which the sultan sought the advice of his leading lieutenants.78

This evidence offers a glimpse of Saladin’s own mindset in 1187. It suggests that his primary instinct was not to present himself as a just and magnanimous victor. Nor was he immediately concerned to parallel his own actions with those of the First Crusaders or, through some grand gesture, to reveal Islam as a force for peace. In fact, neither the sultan’s letter nor Imad al-Din’s account makes any explicit reference to the 1099 massacre. Instead, Saladin actually felt the need to explain and excuse his failure to butcher the Franks inside Jerusalem once a breach in the city’s defences was made. This was because, above all else, he feared an attack upon his image as a warrior dedicated to the jihad–as a ruler who had forced Islam to accept Ayyubid domination on the promise of war against the Franks.

This insight might cause some re-evaluation of Saladin’s character and intentions, but it should not prompt the pendulum to swing towards a total, polar opposite. The sultan’s behaviour must be judged in its proper context, against contemporary standards. By this measure, Saladin’s conduct in autumn 1187 was relatively lenient.79 According to the customs of medieval warfare–which, broadly speaking, were shared and recognised by Levantine Muslims and Frankish Christians alike–the inhabitants of a besieged city who staunchly refused to capitulate right up until the moment that their fortifications were breached or overcome could expect harsh treatment. Typically, in such a situation, the defenders’ opportunity to negotiate had passed and their men would be killed, their women and children enslaved. Even if the final settlement in Jerusalem was heavily influenced by Balian’s threats, by the norms of the day the terms that Saladin did agree were generous–and, more important still, they were honoured.

The sultan also acted with a marked degree of courtesy and clemency in his dealings with his aristocratic ‘equals’ among the Franks. Balian of Ibelin was forgiven for breaking his promise not to remain in Jerusalem, and an escort was even provided to take Maria Comnena to Tyre. Reynald of Châtillon’s widow, Stephanie of Milly, was likewise released without any demand for ransom.

The conditions of surrender settled upon around 30 September contained a number of fundamental provisions. Jerusalem’s Christian populace was given forty days to buy their freedom at a prescribed cost of ten dinars for a man, five for a woman and one for a child. In addition, they would be given safe conduct to the Latin outposts at Tyre or Tripoli and the right to carry away their personal possessions. Only horses and weaponry had to be left behind. After forty days those unable to pay the ransom would be taken captive. In the main, this agreement was followed and, in some instances, Saladin showed even greater generosity. Balian for instance was able, in return for one lump sum of 30,000 dinars, to secure the release of 7,000 Christians, and attempts appear to have been made to arrange a general amnesty for the poor.

Once enacted, the terms of capitulation resulted in a near-constant stream of refugees from Jerusalem, as bands of disarmed Franks were escorted to the coast. In practice, the system of ransoms proved to be an administrative nightmare for Saladin’s officials. Imad al-Din admitted that corruption, including bribery, was rife, and he bemoaned the fact that only a fraction of the money owed was ever lodged in the sultan’s treasury. Many Latins apparently slipped through the net: ‘Some people were let down from the walls on ropes, some carried out hidden in luggage, some changed their clothes and went out dressed as [Muslim] soldiers.’ The sultan’s willingness to allow the Franks to depart with their possessions also limited the amount of plunder. Patriarch Heraclius apparently left the city weighed down with treasures, but ‘Saladin made no difficulties, and when he was advised to sequestrate the whole lot for Islam, replied that he would not go back on his word. He took only the ten dinars from [Heraclius], and let him go to Tyre under heavy guard.’ At the end of the allotted forty days, a total of 7,000 men and 8,000 women were said to have remained unransomed, and they were taken captive and enslaved.80

On balance, Saladin cannot be said to have acted with saintly clemency that autumn, but neither can he be accused of ruthless barbarism or duplicity. In the version of events he broadcast to the Muslim world, the sultan clearly presented himself as a mujahidwilling, even eager, to put the Jerusalemite Franks to the sword, but it is impossible to determine whether this was his true intent. As it was, once confronted by Balian’s threats, Saladin chose negotiation over confrontation and went on to show a considerable degree of restraint in his dealings with the Latins.

Jerusalem’s triumphant reconquest marked the apogee of Saladin’s career to date. Crucially, he could now draw upon this epochal achievement to legitimise his unification of Islam and to refute any charges of self-serving despotism. These two themes of astounding victory and ‘innocence’ affirmed permeated his letter to the caliph–they also formed the backbone of a further seventy letters written by Imad al-Din that autumn, publicising the Ayyubids’ success.81

Jerusalem repossessed

The day of Jerusalem’s formal surrender was selected with some care, so as to emphasise the sultan’s image as a proven champion of the faith. Centuries earlier, Muhammad himself was said to have made his Night Journey to Jerusalem, ascending from there to Heaven on 2 October. Drawing clear parallels between his own life and that of the Prophet, Saladin chose that same date in 1187 to make his triumphal entrance. Once within the walls of the Holy City, the transformative work of Islamicisation began apace. Many Christian shrines and churches were stripped of their treasures and closed; some were converted into mosques, madrasas (teaching colleges) or religious convents. The fate of the Holy Sepulchre was debated intensely, with some advocating its total destruction. More moderate voices prevailed, arguing that Christian pilgrims would still continue to revere the site even if the building were razed to the ground, and Saladin was reminded that Umar, Jerusalem’s first Muslim conqueror, had left the church untouched.

The spiritual dimension of Saladin’s achievement was manifested most clearly in the assiduous care with which he and his men set about ‘purifying’ Jerusalem’s holy places. Chief among these were two sites within the Haram as-Sharif (now also known as the Temple Mount)–the Dome of the Rock and the Aqsa mosque. In the eyes of Islam, the Franks had subjected both of these sacred buildings to the gravest desecration. Now this work was dutifully undone. Under Latin rule, the Dome–built by Muslims in the late seventh century and believed to house the rock upon which Abraham prepared to sacrifice his son and from which Muhammad ascended to heaven during his Night Journey–had been transformed into the Templum Domini (Church of Our Lord), its resplendent golden-hued dome adorned with a huge cross. This symbol was ripped down immediately, the Christian altar within and all pictures and statues removed, and rose water and incense used to cleanse the entire structure. After this, one Muslim eyewitness proudly proclaimed that ‘the Rock has been cleansed of the filth of the infidels by the tears of the pious’, emerging in a state of purity, like ‘a young bride’. Later, an inscription was placed upon the Dome, commemorating the sultan’s achievement: ‘Saladin has purified this sacred house from the polytheists.’

Similar work was undertaken at the Aqsa mosque, which the Franks had first used as a royal palace and then reshaped as part of the Templars’ headquarters. A wall covering the mihrab (a niche indicating the direction of prayer) was removed and the entire building rejuvenated, so that, in the words of Imad al-Din, ‘truth triumphed and error was cancelled out’. Here the first Friday prayer was held on 9 October and the honour of delivering the sermon that day was hotly contested by orators and holy men. Saladin eventually chose Ibn al-Zaki, an imam from Damascus, to speak before the thronged, expectant crowd. Ibn al-Zaki’s sermon appears to have stressed three interlocking themes. The notion of conquest as a form of purification was emphasised, with God praised for the cleansing ‘of His Holy House from the filth of polytheism and its pollutions’ and the audience entreated ‘to purify the rest of the land from this filth which has angered God and His Apostle’. At the same time, the sultan was lavishly praised, acclaimed as ‘the champion and protector of [God’s] holy land’, his achievements compared to those of Muhammad himself, and the efficacious nature of jihad exhorted with the words: ‘Maintain the holy war; it is the best means which you have of serving God, the most noble occupation of your lives.’82

Saladin’s achievement

The summer of 1187 brought Saladin two stunning victories. Seizing the moment after the Battle of Hattin, he reconquered Jerusalem, eclipsing the achievements of all his Muslim predecessors in the age of the crusades. Decades earlier, his patron Nur al-Din had ordered the construction of a staggeringly beautiful, ornate pulpit, imagining that he might one day oversee its installation within the sacred Aqsa. Now, in a final, telling act of appropriation, the sultan fulfilled his predecessor’s dream and shouldered his legacy, bringing the pulpit from its resting place in Aleppo to Jerusalem’s grand mosque, where it would remain for eight centuries.

Tellingly, even Saladin’s contemporary Muslim critic Ibn al-Athir acknowledged the unrivalled glory of the sultan’s accomplishments in 1187: ‘This blessed deed, the conquering of Jerusalem, is something achieved by none but Saladin…since the time of Umar.’ Al-Fadil, writing to the caliph in Baghdad, emphasised the transformative nature of the sultan’s defeat of the Franks: ‘From their places of prayer he cast down the cross and set up the call to prayer…the people of the Koran succeeded to the people of the cross.’83 Eighty-eight years after the First Crusaders’ stunning triumph, Saladin had repossessed the Holy City for Islam, striking a momentous blow against Outremer. He had reshaped the Near East and now seemed poised to achieve ultimate and enduring victory in the war for the Holy Land. But as news of these extraordinary events reverberated throughout the Muslim world and beyond, eliciting shock and awe, Latin Christendom was stirred to action. A vengeful lust for holy war awakened in the West and, once again, vast armies set out for the Levant. Soon Saladin would be forced to defend his hard-won conquests against a Third Crusade, battling a towering new champion of the Christian cause–Richard the Lionheart.