The battle for Stalingrad is frequently cited as the bloodiest, most hard-fought and most destructive struggle of the Second World War and for the Luftwaffe’s part in this monumental contest was always gruelling. They played many roles, not only attacking targets, but carrying out reconnaissance and patrols, gathering information and airlifting supplies. Hermann Goering’s boastful opinion of his Luftwaffe had remained unchanged and when the Sixth Army was encircled and trapped inside Stalingrad in late November 1942, he assured Hitler that the air force was able to provide the supplies needed to sustain the Germans and enable them to keep on fighting. The amount required was about 550 tons a day. It proved to be an impossible target, given the ferocity of Russian anti-aircraft activity. The end result was the near-destruction of the Luftwaffe’s transport arm.

In these circumstances, any role the Luftwaffe might play on any particular day was dangerous and nerve-wracking. Horst Ramstetter considers his missions at Stalingrad were the hardest he ever flew in his entire career as and airman.

‘Undoubtedly, the most difficult mission was Stalingrad, because the concentration of defences was so enormous, more than at any time from beginning to the end of the Russian campaign. For me at any rate, it was an enormous effort to reach the various points that had been chosen as targets there, fly there and do the job.’

The job entailed pounding Stalingrad with such damaging raids that the water mains were destroyed and large areas of the city were left burning. Many of the buildings had to be pulled down to stop the blaze spreading. Dar Gova, in the south of Stalingrad near the River Volga, was obliterated, leaving its rows of neat bungalows a mess of smoking wood and ash. At the nearby sugar plant, now in ruins, only the grain elevator remained standing.

Before the battle began, the younger German airmen had not realised what they were in for. Horst Ramstetter remembers the excitement and anticipation of 18-year olds facing their first battle, and how quickly these feelings changed.

‘When our advance on Stalingrad began, everyone said, great, we’re moving, marching, everything’s fine. Then they realised too late that the Russians had no intention of losing. To them, Stalingrad was a sort of ‘show town’, an object of prestige. Some of the pilots were only eighteen and had never flown a mission. They’d had their heads filled with ‘Führer, Volk and Vaterland - we’ll storm onwards, we heroes will win the war!’. But the real thing was very different. They came back crying their eyes out. They were ready to drop, they hadn’t been prepared for such an operation, or for an enemy as ferocious as the Russians. The raw reality pulled them back down to the earth.’

Ramstetter remembers how he discovered that the Russians had broken through the German defences.

‘Romanian troops, our Allies, were fighting with our forces. They were positioned to the north of Stalingrad. Two of us flew a mission over the area. We were supposed to find out what was going on because the front line was a bit confused. I looked down and saw these greyish-brown uniforms. The Romanians! I thought, and decided to check it out.

‘I dived down, but I was fired at. I said, ‘Those crazy Rumanians, why are they firing at us, we’re -.’ It wasn’t the Romanians, it was the Russians but what were they doing there? I immediately flew back to base at Pitomnik and reported: the Russians have broken through. Where? I showed them where on the map. ‘That’s impossible,’ they said ‘That’s where the Rumanians are. Yes, exactly there, I said. And once the reconnaissance had flown over and confirmed my report, we prepared the airstrip ready for defence.

‘We knew if the Russians kept advancing like that, that they’d be on top of us in a day. We had nothing, no infantry, nothing. We had already been forced to evacuate our airfield, because the Russians were too near. Now, they were coming close again and all we could do was sit in the trenches and wait until they arrived. We lay there all night and at first light, at dawn, we climbed into the planes and flew up over the airstrip. The Russians were already there, and they fired on us.

‘We flew fifteen or sixteen missions. We were reloaded with ammunition and bombs whilst the engines were still running and then we had to take off again.’

By October 1942, the battle for Stalingrad had already become a battle of attrition. Russian resistance was so fanatical that General Paulus, in command of the German Sixth Army, lost four battalions in exchange for capturing a block of flats. On 14th October, five German divisions were sent to overrun two factories, supported by three thousand sorties from the Luftwaffe.

In December 1942, Horst Ramstetter’s squadron was transferred to Nichechieskaya, south of Stalingrad. They wanted to celebrate Christmas with a sing-song but instead found themselves in the thick of battle.

‘We heard: ‘Alarm! Alarm! The Russians have broken through’. Thank God we had an 88 flak unit with us, one that had been pulled back from the front. The 88 was the best anti-tank gun of all, although it had been intended as an anti aircraft gun. But it kept the Russians off our necks and we were able to take off and fly over Stalingrad which was already under siege. Army Group South were supposed to relieve the Sixth Army with their advance tanks. We thought, great, thank God! But it didn’t work out that way.

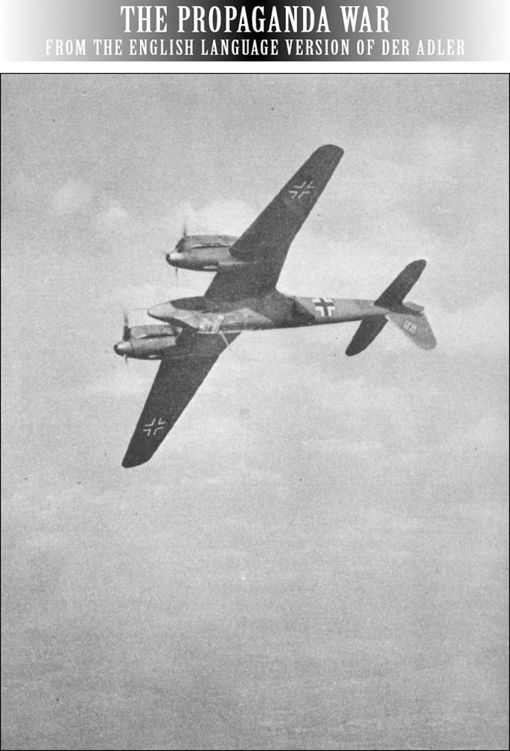

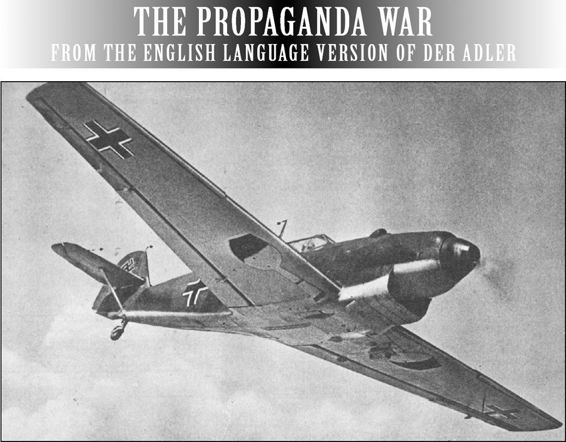

The Fw-87 Flying upside-down. The clean-cut lines of this modern destroyer plane show that it can complete with any antagonist in speed and manoeuvrability.

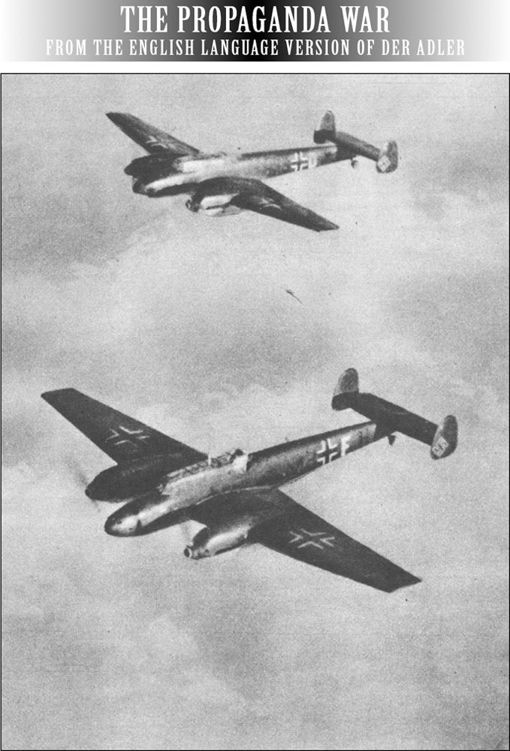

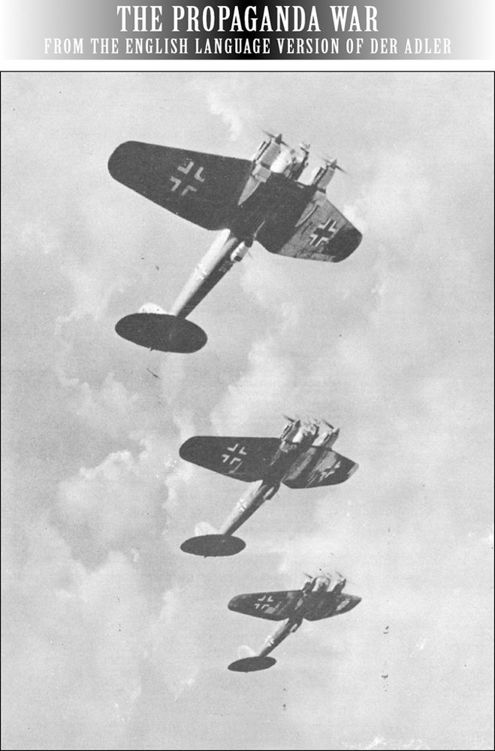

Destroyer formation on the wing. The powerful engines and a copious supply of fuel give this type of airplane a wide radius of action.

‘General Paulus, with his 150,000 soldiers, sat there in Stalingrad. The supply lines weren’t working. They’d been told ‘The Luftwaffe can supply you, you can hold out. But that didn’t work. They went hungry, they had no ammunition no fuel, and they ate the horses that were lying around dead. We saw the front line of the relieving army and saw the signals from the besieged pocket. The distance between them was 40 kilometres.

‘The men on the ground had been told: ‘When a German soldier stands there, he does not yield one centimetre of ground’. These stupid orders, the glorification of heroism. Madness! Suddenly the relieving army halted. What’s wrong now, we wondered? I’ll tell you: the Russians broke through the southern wing and soon Russians and Germans were fighting house to house. Sometimes they were on different floors. When we flew attacks on Stalingrad, we couldn’t tell our troops from the Russians.’

For Ramstetter, total war on the ground at Stalingrad was translated to total war in the air.

‘We carried many injured men, picked them up directly from the from the medical stations near the front lines, we flew very close to the front, but at low level. We were often able to avoid the flak because we knew roughly where the flak batteries were. But over Stalingrad we used to fly very low because the light flak, which was operated by women, was very accurate and low flying meant they couldn’t track us so easily.

‘The heavy flak was quite a different matter. The Russians had set up their flak, and before you got to the Stalingrad, you saw what looked like a wall of fire. Shells detonated, it looked like darker and lighter balls of cotton wool. And we had to fly into them! There wasn’t time to be afraid because we were so preoccupied with keeping our planes in the air, but when I returned to base, I felt I had just been dragged across an obstacle course. We didn’t have much respite, though. We were soon in the air again, to reconnoitre the Russian troops’ supplies.

On one such mission, disaster nearly overtook Ramstetter after his aircraft was shot down. He narrowly escaped the Germans’ worse fear in Russia, being captured by the communists.

‘I was flying an FW-190, and discovered a Russian train loaded with war material. We attacked and destroyed the engine, but my aircraft received a massive hit and I had to make an emergency landing. I came down behind the Russian lines.

‘We carried emergency rations of a bar of choco-cola and weather proof matches and Dextrose. We had the machine gun on board the plane and were carrying our own hand guns. I got out of the plane, saw a corn field and ran into it. I heard the troops rolling past somewhere in the distance and I said to myself: ‘If the Russians should come now, you’ve got seven or eight rounds in your gun. You can try to get the Ivans with seven of them and the last one you’ve got left will be for yourself.’ But I thought again and said: ‘Nothing doing! I’m not going to kill myself.’

‘I had my compass with me and knew in which direction I had to go. I set off, always keeping myself hidden. On the second night, I arrived at a German border position on the front line. I swam across a river and ran across a field and shouted, ‘Don’t shoot! I’m a German pilot!’ But just as I reached the position safely, a Russian fighter-bomber appeared and dived down on us. Everyone threw themselves to the ground and some men jumped on top of me. They saved my life. They were hit by shrapnel, but I survived, but I thought, I’d rather volunteer for 100 combat missions than go through another day like this.’

Aerial combat with the Russian fighters was a traumatic experience for Detlef Radbruch.

‘It’s an awful moment to see six planes fly towards you all at once. It was frightening. We didn’t know what was going to happen. But when you were fighting, operating the gun and firing it and hitting your opponent were the only things that mattered. When we had flown difficult missions, we called it birthday celebrations, we celebrated our birthday, for having got through it.

‘We flew in formations of up to five planes and each had three machine guns. We had agreed on the tactic of firing at the first Russian plane that approached us and mostly we managed to shoot it down or damage it badly so that it turned away. When that happened, the other five Russians turned away as well. Except, that is for the pilot we called ‘the Commissar’. You always knew there was a fanatical communist piloting that plane, because he’d attack us even though we outnumbered him. We were hit many times. Once, our undercarriage was hit so that we had to land on one wheel and make a crash landing. Fortunately, all of us got out in one piece.

‘We were very lucky, but many others weren’t. It’s a terrible thing to see a comrade shot down. During transport flights over the Kuban bridgehead in the Caucasus, we had escort planes. They kept the Russian fighter planes at a distance but several of them were shot down. When we saw that, it was a great shock every time. At Stalingrad, some 488 planes were shot down and more than one thousand airmen were lost. It had taken a long time to train them - a year for radio operators and about as long for pilots, but all that could be lost within a few minutes.’

Despite all the efforts of Detlef Radbruch and other German pilots, the 550 tons a day the encircled Sixth Army had been promised by Goering never materialised. It was difficult enough for the Luftwaffe to deliver 100 tons a day, and even that was rarely achieved. The transports were frequently ambushed by Russian fighters, which had special orders to destroy German supply aircraft flying to Stalingrad. On 24th November, four days before the Russians completed their encirclement of the Sixth Army, Luftflotten 4 lost twenty two out of forty-seven of their Ju-52s. Another nine were destroyed the following day. General Baron Wolfram von Richthofen, a cousin of the famous ‘Red Baron’, realised the how crucial this rate of loss was: ‘We simply have not got the transport aircraft to do it,’ he said. By December, losses among the Luftwaffe transports had risen to thirty percent of all flights attempted.

The Luftwaffe fighters, too, came under threat and Richthofen was forced to move some of his fighters into Stalingrad in order to protect them. He admitted: ‘We have not been able to master the Russian fighters absolutely and, of course, the Russians can attack our forward airfields any time they like. We have been able to fly in only 75 tons instead of the 300 tons we were ordered to deliver.’

Richthofen had only 550 bombers, 350 fighters, 100 reconnaissance planes and his few transports against the Russians’ 1,250 planes. The standard of servicing was low and the intense cold damaged the fabric of the aircraft, causing many of them to crash. Supply lanes that managed to land safely were plastered on the ground by Russian artillery and roving T-34 tanks and bombed and strafed by Russian fighters. Unloading them had to be done at speed, the wounded were embarked and the aircraft would have to run the gauntlet again to take off safely. The casualties in men and aircraft were massive and Pitomnik, the principle supply field for Stalingrad, was full of bomb craters, snow and wrecked planes.

Despite all this, Goering’s orders to supply the troops inside Stalingrad with 500 tons a day or more still stood. Richthofen realised the part played by ego and politics in Goering’s refusal to see sense.

‘Orders are orders and we’ll do our best to carry them out,’ he commented. ‘But the tragedy is that no local commander on the spot, even those who enjoy the Führer’s confidence, can any longer exercise influence. As things are, we commanders, from the operations point of view, are now nothing more than highly paid NCO’S.’

When he first arrived in Russia, Detlef Radbruch worked at the direction finding station that regulated the air traffic supplying the German pocket at Stalingrad, but he had been told he should get some flying experience, and at the end of January 1943, he flew with a night mission over the city.

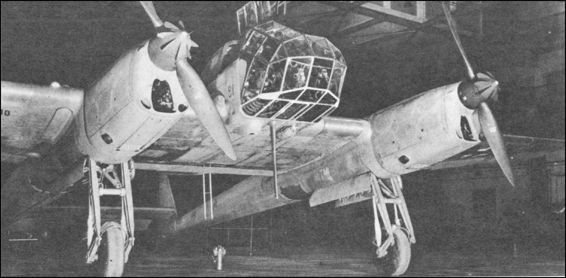

Preparations for the next take-off; the armourer is fitting ammunition belts into the machine-gun drums

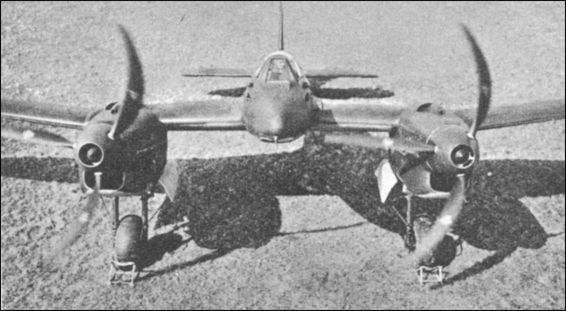

Front view of the Fw-187 destroyer, showing the arrangement of the machine-guns at each side of the pilot’s seat.

‘The pilot of our aircraft had already flown eleven missions to Stalingrad, so that was a lot of practice and we were going to be very grateful for it. But it was extremely dangerous, the temperatures were below minus 30, and the distance to the airfield at Stalingrad was over 300 kilometres, so it was going to be a big effort to return to base.

‘The Russians had set up very powerful flak around the Sixth Army in the pocket at Stalingrad. General Paulus had already surrendered, but there was a detachment to the north of Stalingrad still holding out. We reached it and dropped our cargo - bread in sacks, sausage and ammunition. One crate, containing special ammunition got jammed in the door and the parachute dropped out and opened. Two of us were able to cut the parachute free but it became entangled in the tail fin aileron and the pilot had to struggle to keep the plane flying. Because he was an excellent and experienced pilot, he was able to get us back to the airstrip. This was the last aircraft supplying the Sixth Army at Stalingrad.

‘Many of us thought the disaster at Stalingrad was Goering’s fault.

‘We didn’t think a great deal of him. At Stalingrad there were between 260 and over 300,000 German soldiers Our planes brought out 40,000 wounded but at least 160,000 fell during the battle, and about 100,000 were taken prisoner. Only about 6,000 came home after the War. The Russian losses at Stalingrad were double or three times ours. They lost over half a million soldiers. In that dreadful battle, over half a million young people or more died because of the madness of two dictators - Hitler and Stalin.’

General Paulus surrendered in Stalingrad on 31st January 1943, and the following July, the Germans attempted to recompense themselves with the massive tank assault on the Russians at Kursk. They were beaten again and weakened their already fragile position on the eastern front. The Luftwaffe, flying in support, was hammered by the Russians and lost 1,400 aircraft. After that, Horst Ramstetter recalls, many planes were grounded due to lack of supplies.

‘We’d been given all sorts of promises, about wonder weapons and miracle armaments, but it was all nonsense. What actually happened was that our supply line broke down and we couldn’t get off the ground. We had to leave the planes standing, or blow them up because we didn’t have any fuel.’

A scarcely less violent struggle was continuing in the Mediterranean, where the Luftwaffe were striving to keep the supplies lines open to the Afrika Korps. This imposed so much strain on the Luftwaffe pilots that one of them, a sergeant by the name of Mosbach, lost his nerve. He told his commander, Hajo Hermann, that he had decided not to fly.

‘We’d been fighting against the Royal Navy and the battles were very hard. RAF fighter planes were there as well, and everyone was under terrible pressure. This Mosbach was a very capable, skilful pilot but one day he came up to me and said. “Sir, I have to report that I don’t feel well, I think I’m going to be shot down on this mission.” I replied, “Have you gone off your head? What’s the matter with you? You’re not an old woman.” “No,” he said, “I know that I’m making myself a laughing stock, but I have such a strong feeling, that I just can’t do it today.”

‘I just stared at him for a bit and said, “Well, Mosbach, I’ve known you for a long time and I’ve never experienced anyone like you come up to me in this way.” I was a bit angry, but I told him: “Stay at home then!” So he stayed at home. But he was shot down during another mission and floated around in a rubber dinghy until the British came and picked him up. But the terrible thing was, he was badly burned and lost his sight.’

On 9th May 1943, the German and Italian troops in Tunisia surrendered unconditionally and Erwin Rommel, the original commander of the Afrika Korps, was said to be relieved that his men were now Allied prisoners and far beyond the reach of Adolf Hitler, who would have sacrificed them rather than capitulate. The last German resistance in North Africa, at Cape Bon, was extinguished on 12th May, when, together with his entire staff, Colonel-General Jürgen von Arnim, commander of Army Group Africa was captured at an inland camp on the peninsula.

The invasion of Sicily took place on 10th July, preceded by one hundred sorties by American Mustang fighter-bombers. They bombed and strafed behind the German defence lines, plastered troop concentrations with cannon-fire and left transport, bridges, locomotives, railway yards and barracks burning and in ruins.

The Luftwaffe was now subjected to the same treatment they had meted out in Poland or Russia. The Allied air presence, which included attacks by Liberator bombers, was so overwhelming that German pilots were unable to get their planes off the ground and within only a few hours, the Allies had command of the air. The Sicilian campaign ended with the Axis surrender on 17th August 1943 and less than two weeks later, Allied forces invaded Italy.

After his service in Russia, Detlef Radbruch flew missions in Italy in support of the German troops on Sicily and as preparation for the invasion of the mainland.

‘We were withdrawn from Russia and flew on special orders to southern Italy, where we were to bring the Division Hermann Goering, an infantry division that was part the Luftwaffe, to Naples. After the surrender in North Africa, we flew around Italy for three weeks, bringing troops to Sicily and Sardinia because the Allied landing on Sicily was expected.’

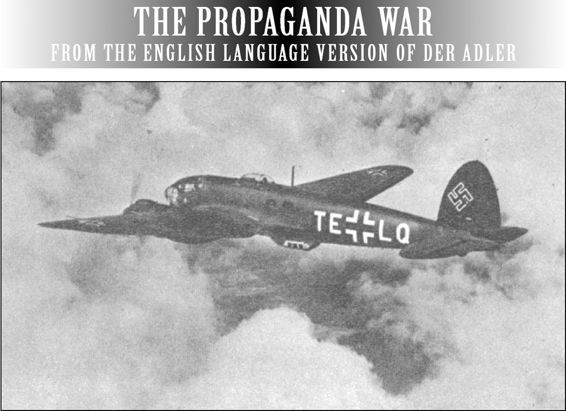

Often referred to as the Fliegender Bleistift (“flying pencil”), this was a very common light bomber or Schnellbomber, which was designed to be so fast that it could outrun opposing fighter aircraft. Equipped with two radial engines, mounted on a “shoulder wing” structure this ungainly aircraft featured a Twin tail vertical stabilizer configuration. Designed in the early 1930s, it was one of the three main Luftwaffe bomber types used in the first three years of the war. The Do-17 made its combat debut in 1937 during the Spanish Civil War, operating in the Condor Legion. Along with the Heinkel He-111 it was the main bomber type available to the Luftwaffe in 1939-40. The Dornier was popular with its crews due to its manoeuvrability and ease of handling. Its sleek and thin airframe made it harder to hit than other German bombers, due to the fact that it presented a relatively small target.

The Do-17 was phased out from front line service from 1942 onwards, as its bomb load and range were too limited. It was discovered however that the Do-17 made a very efficient reconnaissance aircraft and performed well as a night fighter, being capable of carrying bulky radar equipment, but still left room for some very heavy offensive weaponry. Some 10,000 of all types of Do-17 saw service with the Luftwaffe.

General der Flieger (Air Vice Marshal) Friedrich Christiansen, still takes his seat at the joy-stick of his Messerschmitt “Taifun” and presents a brilliant example of German flying spirit to the youth of the country.

One day, Radbruch was on the airfield at Naples Cappodiccino when he heard and ‘unbelievable’ sound of engines. He looked up and saw sixteen Me-323 Gigant troop transports above him. The size and capacity of the Me-323s was reflected in their name. The Gigant, which flew on six engines, had a length of just over 92 feet, and could carry 130 troops and 21,500 lbs. of freight, three times the capacity of the Junkers-52. Despite their formidable appearance, they were far from impregnable. Gigants were slow-flying and vulnerable and in April 1943, during the last days of the war in Africa, a Polish Fighter Wing serving with the RAF had downed most of a flight of twenty Gigants and sank tons of much-needed supplies into the Mediterranean. The Gigants Radbruch saw were going to meet a similar fate.

‘I saw these planes and immediately thought, ‘Oh God, that’s not going to work, because the Allied air superiority is too great. In the evening after an Italian flight, I returned and went into the casino, A captain sat at the bar shaking his head and getting drunk: he had seen the death of the Gigants. All of them had been shot down. Each Gigant was carrying 20 tonnes of fuel, which was to be taken to Tunis. The captain said that he saw the sea burning, he was very shocked.’

Detlef Radbruch had his own dangers to face in Italy.

‘We fetched German troops from Livorno and brought them to Sicily and Sardinia. These flights were very dangerous. We had to fly very low because many of our aircraft were being shot down at that time. The twin-engined Lightnings found our Junkers all too easy to destroy. We flew very, very low, because the fighters can’t operate down there, and apart from that, we hoped that if we flew over the sea and were hit we could make an emergency landing in the water and be saved.’

In Italy, the Luftwaffe scored a surprise success on the night of 2-4th December 1943, when 105 Ju-88s attacked the Adriatic port of Bari, where the First British Airborne Division was based during the transfer of Allied Forces from Sicily. The attack was entirely unsuspected. There had been no attempt to blackout the port. The docks were brilliantly lit as the Luftwaffe swooped in on the thirty ships in port, and blew up two ammunition ships which caused the loss of another seventeen vessels.

One of these, the John Harvey was carrying a secret supply of mustard gas as insurance against the chance that the Germans might resort to gas warfare. The John Harvey blew up in a massive fireball that threw debris and her deadly cargo hundreds of feet into the air. The crew died instantly, and among the rest of the estimated one thousand casualties, more than half, 628 people, died of mustard gas poisoning. Large areas of Bari were reduced to rubble, and the capacity of the port was severely curtailed for the next three weeks.

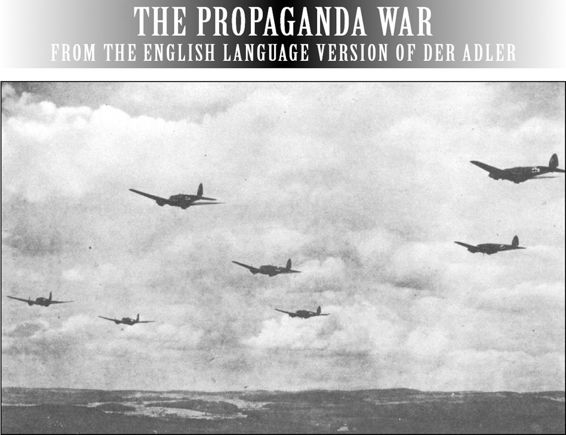

Powerful formations of German bombers raided the enemy and several raids on a single day, favoured by good weather all through, were nothing uncommon.

A Messerschmitt destroyer of the Me-110 type circles over Palermo, the Sicilian city.

The raid on Bari resulted in supply shortages to the Allied Fifth Army in Italy and the losses sustained there prevented the US Fifteenth Air Force from participating in raids on Germany for another two months. However, the raid was not a sign of renaissance for the Luftwaffe. It was more of a final sting in the tail of a once-deadly scorpion. The Luftwaffe was, in fact, in a desperately decimated state by the time the Allies invaded Italy. There was a serious decline in number of pilots and their effectiveness naturally suffered. The Luftwaffe retained its esprit de corps and its camaraderie, but these were small advantages compared to the enormity of the task facing them after 1943. Preserving their planes and pilots became an important consideration. Horst Ramstetter was one Luftwaffe pilot who had to judge whether or not it was wise to attack.

‘We had to think about whether the risk we were taking was worth it and what would happen if an attack went wrong. Sometimes we’d attack a position four times and blaze away at it with everything we had. The problem then was that the enemy fighters arrived, and our weapons went ‘Click!’ - there was no ammunition left.

‘After that you had to start thinking about whether you’d get back to home base or not. There was, though, a trick we used to use. We called it the ‘pilot’s fart’. There was a stopper that you could pull out and you got extra burst of speed through an additional injection of fuel and went 40 or 50 kms. faster. The snag was that when you had pulled that thing, it virtually destroyed the engine. You could fly for perhaps five minutes and then it was over. But in an emergency, you hoped that the five minutes enabled you to escape.’

In spite of such ploys, the situation of the Luftwaffe worsened steadily.

‘The pilot training periods were reduced, and because the new fighter pilots had no experience, they were the first to be shot down. As the War went on, we were no longer capable of flying missions over manufacturing plants while at the same time, Allied bombing raids on Germany were hurting us a lot.’

One important setback for the Luftwaffe was that the Allied planes had made the Me-109s obsolete. Not only was it outclassed, but the version introduced at the end of 1942, the Me-109G, carried so much firepower and extra equipment for protection against Allied attack that it was unable to operate successfully. The Luftwaffe’s operational strength fell to a mere 4,000 aircraft, with no reserves. From there, the numbers fell consistently, leaving the Germans no more than 1,800 aircraft during the rest of the War. Besides this, the Allied bombing campaign on Germany reduced the Luftwaffe to a defensive role, something for which it had never been designed.

The Allied raids went on round the clock. The United States Army Air Force Flying Fortresses and Royal Air Force Lancaster bombers took turns, the first bombing Germany by day and the second, bombing by night. The cities as well as the factories of the Fatherland were targets. The Luftwaffe was short of night-bombers, and the JU-88, built as a light bomber, had to be specially adapted to cope. Heinz Philip was a gunner with one of these JU-88s.

‘As the night fighting became acute, when the English started to come more and more frequently at night - we didn’t have any planes specifically for the night. At first the ME 110 was equipped and put into operation as a night fighter but it couldn’t fly for long enough and didn’t carry enough guns, so in order to be able to use more weapons the JU 88 was used. Trials with other planes were made, but they proved ineffective.

‘We didn’t carry bombs. When the plane was constructed there was a space intended to house bombs and this space was filled with a tank, an additional tank so that we were able to keep flying for four hours.

‘I sat at the guns on the Ju-88. There were four 2cm guns at the front and the magazines were in such a position that I could remove them when they had been emptied, that was my job, and I had to fix new magazines to the back. That was something to occupy me, but I didn’t do it continuously. And when the English or the Americans attacked, that was during the day, they defended themselves and I looked at them head on. To look head on at a machine gun that is firing at you, that made me very nervous, and the pilot was busy with his plane whilst I just sat beside him and didn’t know what to do. That happened the first time, but the second time I took my camera with me and from then on when we flew during the day, I took photographs so that I had something to do, to distract myself.’

Hannau Rittau served on one of the Luftwaffe anti-aircraft batteries defending Berlin from the Allied raids.

‘Our battery had four guns, one range finder and one radar. There were about six people operating each gun, another six to operate the range finger and five on the radar. Our job was to protect the Heinkel aircraft factory at Oranienburg, a suburb in the north of Berlin. The light-anti aircraft couldn’t come into action at all because the Allied airplanes flew far too high. We couldn’t reach them because we could fire no higher than 3,500 metres or thereabouts. But the planes usually came over at almost twice that height - around 6,000 metres and only the heavy anti-aircraft could deal with them.

‘Berlin was bombed almost every night, well, perhaps not every night but very regularly. The worst of it came in 1944, when the Allies started their thousand-bomber raids and one thousand of them came over at one time. The sky filled with planes and during these raids, I was at my range finder. I had to pick up the aeroplanes, and get all the data which was transferred to the guns so that they could fire at the aeroplanes at the right height. There was no time for training. We learned on the job.

The He-111 ready for its nocturnal trip and the crew are aboard. One engine is already running, the other will start in a moment.

Hard at work in the operations room.

The finished Ju-87 hangs as lightly as a toy from the steel cables of the crane.

‘Our battery was on the outskirts of Berlin Most of the anti-aircraft guns were on the outskirts, except for two anti-aircraft towers which were located right in Berlin, one of them at the Zoo. Berlin looked very, very damaged, houses came down and collapsed in ruins. But you got used to that after a while, you get used to everything after while. But we didn’t like getting it every night, that was horrible.’

The raids on Berlin normally started at around 2200 hours and Rittau’s antiaircraft was alerted by radio.

‘We were told where the bombers were, and were in action for three or four hours as they unloaded their bombs. Unfortunately, our flak wasn’t very effective. Our battery shot down in total of eight planes which wasn’t much considering how many raiders there were. We used to put a ring on our guns for every aircraft we shot down.

‘We thought of the pilots up above us and wondered how they felt, being fired at. I don’t suppose it felt very good when you sit in an aircraft and see all this firing going on around you and know the next one shell might hit your plane. I think that we damaged some of the planes and didn’t think they would get back to England. Some of them came down over the Netherlands or in France. On the other hand, we were the ones being bombed, so we were very glad when we were able to shoot down an Allied plane.’

Rittau’s world during a raid was a world of noise and flames.

‘You hear a humming sound all the time - that comes from the bombers flying overhead. We used to watch through binoculars to see when the bombs came down. Of course, you could figure out roughly where they were going to fall and sometimes, if it looked too close, you had to dig in, duck your head. and pray you weren’t hit. It was terrible, I mean it was a terrible noise, you would see flames over the place. We were scared, no question, all of us, but fortunately our battery was never hit by a bomb.’

Hajo Hermann was flying over Berlin in his Me-109 on 24th August 1943, while one of the Allied raids was going on. The raid was not a surprise, for Air Chief Marshal Arthur ‘Bomber’ Harris had already announced it. The Germans were well aware that Harris’ strategy was to win the War by bombing them into submission - a mistake Hermann Goering had already made about the British during the Battle of Britain. Hajo Hermann had already survived several brushes with death. This mission came the closest to costing him his life.

‘We were more or less prepared for the next attack that Harris had announced. It seemed to cause a certain amount of panic. The people, women and children above all, were evacuated from Berlin, and I stood ready to join in the fight. I flew during the night of 23-24th August from Bonn-Hangelar to Berlin, and from a distance I could see that over Berlin an enormous firework display was under way. The flak shells and searchlights were shining and I noticed the first planes being shot down. Then I went into action.

‘There was a bomber in front of me which I fired at but it escaped by spiralling away. I wanted to be more accurate with the next one and flew very close to it. But stupidly, I flew so close that I was lit up by the German searchlights below. So was he, and we fired at one another at almost point blank range. I could see the whites of his eyes, so to speak, and I suppose he could see mine.

‘His plane started to burn and the crew had to bail out. He fired and hit my engine. Smoke began to pour from it and I had to bail out, too. I fell into a lake, wearing full war gear, in other words, an overall with the parachute but without anything such as a life jacket. I had to struggle to keep my head above water, and with great difficulty managed to swim ashore where I met one of the British crew. He was quite friendly. Later on, another member of the bomber crew was sent to a nearby hospital and I visited him there. What happened to me was a rather stupid affair, but at least Harris’s bombers didn’t return to Berlin for another two months, except in very small groups.’

In January 1944, the RAF staged a big attack on Hitler’s headquarters. Once again, the Germans knew about it in advanced, having intercepted the British coded messages. When the raid took place, Hajo Hermann was in action again and once again brushed with death.

‘The weather was quite bad. Nevertheless, I got my man in my sights and hit him. His plane started to burn, but just then, a large area of defensive lighting spread out over the clouds. I was more interested in seeing if the plane was going to crash and while that was going on, I became visible as a silhouette against the light beams.

‘From behind me to the left, a Mosquito fired a salvo into my engine and everything was smashed up inside it. I got shrapnel in my leg and it was very unpleasant. At first I didn’t notice that I was bleeding. I noticed it only when my leg became cold. I grasped it and saw what had happened. Well, I told myself, you’ll have to do something to get down fast, and I flew towards the west because the weather looked as if it was better there.

‘I managed to reach an area around Hagen in the Ruhrgebiet, near Dortmund, but I hardly knew what I was doing. I was in a very bad state, with bouts of blindness and thought I was going to fall unconscious. I said to myself, before I crash down below with the plane, I’ll bail out and that’s what I did. I came through the clouds and snow storm and landed on the ground, but in really dreadful condition. I came down in a forest clearing, at about six o’clock in the morning, a door opened somewhere, some light shone and I called out, and some people quickly picked me up and drove me to a hospital. Fortunately, the hospital wasn’t far away.’

The Mosquito that shot down Hajo Hermann belonged to the squadrons that were ranging virtually at will over German territory in the latter part of 1943. The Luftwaffe tried desperately to inflict losses and reduce the onslaught, but all that happened was that the Allied planes came over in increasing numbers. They were using new techniques - the ‘pathfinder’ system which located and marked targets by radar, and the strips of metalised paper known as ‘window’ which, when released in the air, jammed and confused Germany’s own electronic defences.

The Luftwaffe could do little or nothing to prevent the systematic destruction of German towns, cities, factories and airfields. Hamburg was destroyed in July 1943, in a raid privately described by propaganda minister Josef Goebbels as ‘a catastrophe the extent of which simply staggers the imagination’. The RAF bombed Wilhelmshaven and Peenemunde, where the V1 and V2, Hitler’s ‘vengeance’ weapons, were being developed. The USAAF attacked the oil fields at Ploesti in Romania and the important ball-bearing factories at Schweinfurt.

Albert Speer, who became Hitler’s Minister of Armaments in 1942 and took total charge of war production the following year, relocated and camouflaged factories and other important installations in an attempt to halt the severe disruption caused by the Allied bombing. The disruption nevertheless continued. Manufacturing capacity was decimated and the development of new weapons, such as the Me-262, was almost brought to a standstill.

Hermann Goering was still criticising the Luftwaffe, this time for not being able to stop the Allied bombers. Heinz Phillip, a fighter pilot, was one of the objects of his ire.

‘When we were confronted with American air superiority, we practically became the hunted, we fighters, and because we hadn’t shot down enough planes and the Americans arrived with the bombs and so on, Goering stood up and said, ‘My fighters have become cowards’. In consequence, the entire officer rank removed their decorations and insignia and went around without their insignias of honour - Knights Crosses and so on, all gone.

‘I couldn’t stand Goering even before I was in the Luftwaffe. I regarded him as a vain, dressed-up fat man who performed like a theatre puppet. He wore fantasy uniforms - once he arrived in a snow-white uniform. He arrived in the morning, had a midday meal, inspected us, in the afternoon he did something or other, he changed uniforms two or three times in that time. He was a vain caricature - the highest decorations, highest-ranking Marshal and God knows what else. I know of one incident when he was urgently needed but couldn’t be found. Eventually, he was discovered at Karinhall, his palace. At Karinhall, there was a gigantic model railway in the cellar. Two or three men from the Luftwaffe had been assigned to him just to look after this railway, and there he was, playing with it.’

Take-off follows take-off, raid upon raid. The fighter pilot is ever ready to hurl himself upon the foe whenever encountered.

Early on in their campaign, RAF and USAAF bombers had been vulnerable due to the lack of fighter escorts that could accompany them all the way to Germany and back. This problem was solved in 1943 by the introduction of the P-51 Mustang fighters and, with these guards to protect them, the USAAF was able to resume the daylight raids that had been abandoned in 1943. This new Allied capability was typified by the ‘Big Week’ early in 1944 which saw continuous round the clock raids, in which RAF Bomber Command took over from the Americans at night. Between 20 and 26 February, the Allied air forces struck at the German aircraft and anti-aircraft factories and assembly plants in Leipzig, Regensburg, Augsburg, Fürth and Stuttgart. The Luftwaffe’s attempts to halt the raids destroyed 244 heavy bombers and 33 fighters planes, but cost them 692 aircraft in the air and many more on the ground.

This was only part of the attrition suffered by the Luftwaffe and its pilots. By May 1944, the Germans had lost 2,442 fights in action and another 1,500 through accidents and although their air industry was not destroyed, the numbers of trained pilots lost were irreplaceable.

The Luftwaffe attempted to cut off the onslaught at source, by attacking airfields in England. Heinemann made two of these flights.

‘We were sent on night fighter raids, with the bomber formations. We found the airfields in England were lit up brightly. I suppose they thought there would be no more Luftwaffe raids. We were supposed to give them some bother over there, but it proved much too dangerous. The raids were cancelled because too few of our planes returned.’

Meanwhile, the shortages occasioned by Allied attacks on Germany’s oil-production facilities meant that training new pilots was curtailed for lack of fuel. Many Luftwaffe pilots going into battle for the first time at this late stage in the War were inadequately equipped to face the Allied challenge and all too often, they were soon shot down by the bombers or their fighter escorts.

Anton Heinemann, one of the Luftwaffe’s night-fighter pilots, remembers the sheer impossibility of the task that faced them.

‘Once the massing of the Allied planes began, you could theoretically shoot down perhaps one plane every half an hour, but the other ninety or hundred had already flown on, heading for their target. Our actual rate of ‘kills’ was no more than six bombers shot down in one night. We thought that was quite a lot. Once we shot down three, which was not so good.

The squadron before starting for the north. The machines are drawn up as on parade and await commands.

‘The problem was the opposing fire we encountered from the rear-gunners on the Allied planes. So, our aircraft were equipped with two guns facing vertically upwards. The rear gunners found it much more difficult to get at us as we flew under the bomber and fired up into its right side in order to make it burst into flames. That worked quite well. We were also given a follow-up round which was belted onto the gun so that we could destroy a bomber’s fuel tanks. We used to pierce the tank, use an explosive shell which increased the size of the hole we’d made and another, incendiary, shell to start a fire.

‘We used to fly mostly in a right-hand curve. The thinking behind this was that in our own aircraft, the pilot sat on the left and we assumed that it was the same in the enemy plane. When a plane caught fire, the Allied pilot wasn’t going to turn onto the side that was burning. So, mainly they flew away to the left, in order to keep the fire above and not below, and I think that gave the crew a chance to bail out.

‘The way we’d fired at the Allied planes was something of a secret weapon. I heard it reported that they were shot down by flak because they didn’t know how we’d shot them down. I always hoped that the crew survived, but for us it was important that the plane and its bombs didn’t get to its target.’

Heinemann himself had the experience of being shot down and bailing out to safety.

‘In December 1943, my plane, a Junkers-88, was hit during one of the daylight missions we had to fly. We were going after a formation of American Boeings and were somewhere between Heligoland and Schleswig Holstein. There were about fifty American aircraft and they had such firepower at the rear that one of our engines was soon on fire, and we had to bail out

‘It isn’t difficult to make the decision to bail out when your engine is burning. All you know is the urge to escape. The Ju-88 had a hatch in the bottom, but when it was thrown open and produces such enormous suction, that if you just held out your boot then, Pphhtt! you were gone. We had been trained to count to about thirty before pulling the cord and then the parachute would open. On this occasion, I don’t know why, I wasn’t able to count to thirty. I got to about ten or twelve and then I pulled the cord. A rush of air got hold of me and I was pulled out of my felt boots. I remember seeing them get smaller and small down below because they were flying faster than I was with my parachute and disappear into the clouds.

‘Then came the interesting question, Was I going to fall into the North Sea or land on the coast? Luckily there was quite a strong west wind and I landed in the area of Itzehoe, northwest of Hamburg, in an empty field. A man came rushing up. He was wearing a yellow badge which meant he was a Polish labourer and he said: ‘Anglees, Anglees?’ He thought an Allied invasion had begun and that he would soon be free. He was very disappointed.’

By the time Heinemann’s Ju-88 was shot down, the American Eighth Air Force had opened up a new avenue of attack on Germany. Its P-51 Mustangs were let loose to search out the Luftwaffe fighters, embarking on a run of some 200,000 sorties during which they shot down 4,950 German aircraft and destroyed another 4,131 on the ground.

The Luftwaffe reeled before this onslaught. So many Luftwaffe aircraft were lost to this new strategy that Adolf Galland commented:

‘The day the Allies took the fighters off close escort duties and allowed them to roam free to engage the Luftwaffe fighters in the air and on the ground was the day we lost the air war.’

The Luftwaffe was in no shape to challenge the greatest of all onslaughts during the Second World War: the D-Day invasion of Normandy on 6th June 1944, when the greatest amphibious force ever known to warfare assaulted Hitler’s Fortress Europe. The air arm of the invasion carried out no less than 11,000 sorties and enjoyed complete superiority in the air from day one. Alfred Wagner was on his first combat mission when this mightiest of air umbrellas imposed its presence over northern France.

‘When we heard that Allied paratroops and glider-bourne forces were in Caen, just before the main Normandy landings, we were stationed a long way away, at Biarritz, near Bayonne on the Bay of Biscay close to the Spanish frontier. We were awakened early in the morning and heard the news and were told we were going to be transferred north straight away.

‘We were taken there on lorries, because we didn’t have enough planes to fly there. On the way, we were attacked continuously by English fighter planes but managed to reach our destination while it was still dark. That was when I saw real, live war for the very first time. The fireworks, they were impressive and frightening at the same time. We were all very young, and we couldn’t really comprehend it.

‘We were quartered in a chateau, quite a comfortable place. There was a landing strip nearby and it was from there that we flew our missions. We flew in four planes in the direction of the front line. The flak came up at us, and you heard the detonation right next to your plane, and saw mushrooms when the shots exploded, directly beside you. It was a very unpleasant feeling. I don’t know if it was enemy flak or ‘friendly fire’, but thank God, I wasn’t hit.

‘Then suddenly the enemy planes were there. I saw a Spitfire flying directly in front of me, but I managed to get away. I got separated from the other three planes and landed back at our airstrip on my own. That was my first mission and it had been quite easy, I suppose except for the flak, of course.

A group of combatant planes of the Heinkel He-11 type.

The order to start. An aircraftman is assisting a pilot to buckle on his safety-belt. The engines will be roaring in a few seconds.

Front view of the Fw-189, showing the device retracting the undercarriage. The machine has just left the assembly bay and will soon, like so many others of its type, be leaving for the firing line to take up its responsible duties.

‘But later, things got really hot. We had to fly to wherever Allied fighters had been reported. We sighted them, and then it began, the swerving, the diving, like some terrible ballet we were performing. It was very nerve-wracking. You had to have eyes everywhere otherwise you could be ‘jumped’ by an enemy and that might be the end of you.

‘Once, we had to attack a formation of Liberators directly head on. That was very dangerous because from head on, you had only about three second - two to fire your guns and then you had to make sure you got away. The Liberators or the Boeing B17s were so heavily armed that there was barely a blind angle to hide in. That’s why we had to fire quickly when we attacked and get away fast.

‘On one mission, an American Thunderbolt appeared in front of my snout, as they say. He tipped himself away to the right so that I could see the pilot quite clearly. He was black! A black American! We looked at one another, I pressed the trigger, there was an explosion and … he was gone. But I never forgot him. We had been eye to eye, opposite one another and that left a deep impression on me. It was frightening, and you said to yourself that the war was such madness; every war was. You shot down people you didn’t know and would never know. It was terrible. ‘

Alfred Wagner discovered the hard way that the propaganda fed to the Luftwaffe pilots was totally untrue.

‘At the beginning 1944, we’d been told that the Luftwaffe had a superiority in numbers of ten to one. The prospects looked good, especially after I’d shot down seven of those ten. But it was all a lie. When I was shot down myself, we were being attacked by three or four Allied planes at one time. So much for Luftwaffe superiority!

‘On that occasion, my plane had problems on the ground. The engine was over-revving, and I noticed that the switch on the control equipment was on manual, when it should have been on automatic. The flight mechanic had been careless, I thought. I switched to automatic, and the number of revolutions dropped considerably. There was a huge wall of dust in front of me from the planes starting before me. I took off, but soon afterwards, reported myself out of service. I wanted to return to the airstrip, but then I looked up and saw a large formation of Thunderbolts above me.

‘I didn’t want to face them with a defective engine and looked about for somewhere to land unnoticed. But the Thunderbolts had seen me, and before I could do anything, a couple of them came down after me. I was hit from behind and saw flashes sparking from part of my wings. The wings were shredded. I felt a stab in my right foot. It must have been an explosive shell and my foot was shredded, too.

‘My plane started to burn and I had to get out. I ejected the cockpit hatch, but couldn’t push myself out properly because my right foot was useless. I managed to push myself out with my arms, and as I did so, my right arm struck the bodywork and the bone broke. Somehow or other, I don’t know how, it must have been instinct, I pulled the ring of the parachute with my left hand, not something you normally did because you were taught to use your right hand. But if I’d tried to do that, I wouldn’t have been alive now. I still can’t understand how I managed to pull the parachute cord with my left hand. It was instinct, I suppose.

‘The air battles in France took place quite close to the ground and my parachute had only just enough time to open. I managed to land all right, but quite far off in the distance I saw the mushroom cloud of smoke rising from where my plane had crashed.

‘I was lying on the ground, fearing I would be shot while I was lying there, helpless. I shouted for help like a madman, and a French farmer came up over a nearby hill. He asked ‘Allemande soldat?’ - German soldier - and all I could say was ‘Oui, toute, suite, hôpital!!’ He said ‘Doucement, doucement’ - softly, softly, and went away.

‘I went on screaming for help and another, older farmer came up and he asked: ‘Allemande soldat?’ I replied again: ‘Yes, quickly, the hospital!’. This one ran away, too. After an age, or so it seemed, a car drove up and two military policeman and the second French farmer got out. The policeman was carrying a machine-gun. He was only two or three metres away when he started firing. I screamed, ‘You stupid animal!’ ‘Oh,’ he replied ‘I thought you were an English Tommy.’ They wrapped me in the parachute, carried me to the car and brought me to the hospital.’

Wagner’s injuries were very serious. His right foot had gone and his right leg had to be amputated below the knee. He had lost the middle bone of his left foot and the fourth toe was missing, but he was alive, an outcome he ascribes to a certain spiritual resilience that surfaces at times of great danger.

‘I think that at such moments, the human being is capable of superhuman achievement, superhuman strength’

Men at war have always had to live with the proximity of violent death or, perhaps even worse, crippling injury. Hajo Hermann had his own way of dealing with it.

‘You may think the entire bird is going to fall to pieces, the plane’s going to break up and that will be the end of you. But you just can’t be continuously eaten up with such emotions. When something goes wrong, of course you get a big shock, but I used to say to my people: ‘If there is a bang and bullets start shooting through the cabin and the wind howls in, well, you can still think, you can still act. All right then, let’s keep going. None of this trembling and dirtying your pants!’

In autumn 1937, the Reich Air Ministry commissioned designs for a new fighter to fight alongside the Messerschmitt Bf-109, which was then Germany’s front line fighter. Although the Bf-109 was at that point an extremely competitive fighter there were concerns that future enemy designs might outclass the Me-109 and it was considered prudent to have new aircraft under development to meet future challenges.

The winning design was the excellent Fw-190 designed by Kurt Tank. It used the air-cooled, 14-cylinder BMW 139 radial engine, which produced improvements in air speed, manoeuvrability rate of climb and operating altitude. The Fw-190 was to prove one of the best all round fighter designs of the war and immediately outclassed the British Spitfires and Hurricanes. It continued in service throughout the war and lent itself to a continuous programme of research and development, which saw it in service as a fighter-bomber, high altitude fighter, night fighter and fast reconnaissance aircraft.

During an attack on British ships at Le Havre at the time of the D-Day invasion in 1944, Hermann witnessed at first hand what could happen when nerves and anxiety took over.

‘I’d borrowed this man from somewhere because my own navigator was ill. When we were about to make the approach run, he would keep saying: ‘Are there barrage balloons? Is there going to be any flak? There are so many searchlights’ and so on. Was I going to make a horizontal approach to the target? he wanted to know No, I told him, that won’t be any good, we won’t hit anything. I’m going to dive on the target.

‘He said: ‘Then I might as well bail out now!’ ‘Please do,’ I told him. He stayed on board of course, but he made a grim face as if he wanted to murder me. Afterwards, when you pull the plane up and see those fat barrage balloons above you, then of course it’s a bit frightening, but you have to say to yourself that the balloons aren’t everywhere, you’ll be able to get past them. This man moaned and groaned all the way back to base. We didn’t fly into any wires, but frankly that was pure coincidence.’

Heinz Phillip knew what it was to be afraid, though he, too, developed his own method of keeping the fear at bay and even acquired a certain detachment about death in the air, whichever side in the War was doing the dying.

‘You can’t hear the flak exploding all round you, but you could see light. There was so much light when you’re flying at around 3,000 metres You could read a newspaper by it and the flashes of explosions and tracer bullets. That’s what it was like up there. You had a very empty feeling in your stomach and there were wet trousers, too, sometimes, There are people who said that they weren’t afraid but I was afraid and most men were afraid too. ‘Glorious, you just fly through it,’ we used to be told. Not at all, that’s just Latin, as we say in Germany, airmen’s Latin.

‘You just can’t get away from the fact that you could be killed at any moment, so you try to distance yourself from death. When a comrade is killed, you try not to think about it too much. I was once playing a game called skat with three other Luftwaffe men. I had a marvellous hand, and so did one of the others. We kept on bidding and it was so exciting that other people in the room stood around watching us.

‘Suddenly, there was an alarm. We threw down our cards, saying we would continue the game later. I was the first one back, so I sat there, cards in my hand, waiting for the other three to arrive. They never came. Then we were told that the pilot had crashed after take off and all three had been burned to death. Maybe it didn’t really register, but I said: ‘Well, there must be someone around here who can finish this game.’ There was, and so we finished the game.

‘It worked both ways, for our opponents as well as for us. We never thought, at least I didn’t and neither did our crew when we talked about it, we never thought that, if we shoot down an Allied plane, then we are going to kill ten people who are sitting inside. For us it was ‘We are not killing the people, we are shooting down the plane.’ That is an enormous difference. For us, the plane was the adversary.’

In the last week of July 1944, after seven hard-fought weeks, the Allies broke out of the Normandy beach head. By mid-August, the German forces were escaping eastwards, with the prospect that the Fatherland itself would soon be open to invasion. Meanwhile, on 15th August 1944, two months after D-Day, the Allies landed in the south of France. Heinz Phillip had his worst experience of the War as the Luftwaffe tried to prevent this second invasion.

‘It was at Coulommières in the south of France. We’d been fighting all through the Allied disembarkation at night. We’d flown low level attacks on the beaches, and we returned to base and wanted to land. But when we were about to touch down, an English night fighter caught us at our most vulnerable moment. When the undercarriage and the ailerons are out, then the plane is as helpless as an old duck. The pilot of the nightfighter was a very good shot. He was directly behind us and when he fired, the radio operator was hit several times in the chest. Our aircraft was still able to fly, the engines were still running and our pilot retracted the ailerons and the undercarriage, accelerated and climbed back up into the air.

‘But we were burning up, left and right, the wings - there are fuel tanks in the wings too and they were on fire. We wanted to bail out, I jumped, but my parachute got tangled in the plane. I was outside and the parachute was up there somewhere, so that I was just about able to look inside. The pilot, who was preparing to get out himself, saw that I was hanging there and he went back to the cockpit, set the plane straight and then he tried to kick me free with his foot. But that didn’t quite work. He bailed out and the plane exploded. Only then was I free and although my parachute was rather shredded, I managed to land all right. But I landed very heavily. The time it took me to get from up there until I arrived down on the ground, it was only a few minutes, but it felt like an entire lifetime.’

In December 1944, the Germans made a desperate attempt to halt the Allied advance towards Germany by attacking the American 7th Army and other forces through the forested plateau of the Ardennes, on the border between Belgium and France. This brief, but doomed, campaign saw the last major offensive by the Luftwaffe, on 1st January 1945 when some eight hundred of their aircraft attacked airfields in France, Belgium and the Netherlands, destroying 156 Allied planes. It was an attempt to disrupt Allied air support, but it failed, with heavy losses. The Ardennes offensive cost the Germans a total of 1,600 planes and the Luftwaffe was finally broken.

Flying and music have one overwhelming feeling in common; the sense of freedom, detachment, and triumph over the workaday world. All those listening there in small groups to the performance of a military band on a field airdrome may be animated by similar thoughts.

The flying crew of a bomber group seem to be enjoying themselves in the protection of their He-111 and are giving the musical interlude every attention.

The Me-262, the world’s first turbojet fighter which first flew in combat in September 1944 came too late to save the Luftwaffe, or Germany. Its remarkable speed of 540 miles per hour, 140 miles faster than any conventional aircraft of its time, was wasted by Hitler when he ordered it to be used as an attack bomber rather than a fighter. Besides this, the Me-262 had cardinal faults, including engines with a service life of only twenty-five hours, and there were too few of them at this late stage in the War to make a difference to its outcome.

The moment the Luftwaffe and the Wehrmacht had struggled so hard to prevent came on 7th March 1945, when troops of the U.S. 9th Armoured Division broke into Germany across the Ludendorff Bridge over the Rhine at Remagen. German engineers were just preparing to blow it up when the Americans arrived. Heinz Phillip had volunteered for a mission to destroy the bridge. It was the only time his Ju-88 dropped bombs.

‘Some volunteers were wanted and I took part, my pilot was always way out in front and I wasn’t always filled with enthusiasm, but I had to go with him. A 5 cwt. bomb was attached below each of the wings left and right, and we were meant to drop them on the bridge at Remagen. Four or five planes in all went on this mission, which took place at night. But of course the Americans had gathered everything together at the Rhine crossing, everything they had, to defend themselves against air raids and it was quite some firework display that was staged there.

‘For us it was not very good because we had drawn number three, in other words we were to be the third plane to attack. Each plane was given a time, and we knew, now the first one is attacking, and then there was a fireball and he no longer existed. Then, the second plane went in, that became a fireball too, except that it was a little lower down, and then it was our turn.

‘You can image what our feelings were. It wasn’t exactly lovely. But we made it. Admittedly we didn’t hit the bridge, our bombs fell beside it, but we got out of it in one piece. But I’ll never forget it, we had eighty-eight bullet holes in the plane by the time we got away.’

The world-tamed Heinkel bomber He-111, which has had a surpassing share in the success of the German operations in the present air war owing to its great fighting power and its speed.

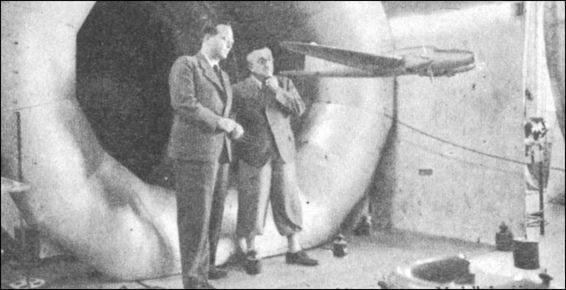

Dr. Heinkel tries out an aerodynamic improvement with one of his closest co-workers on a model of the He-111.

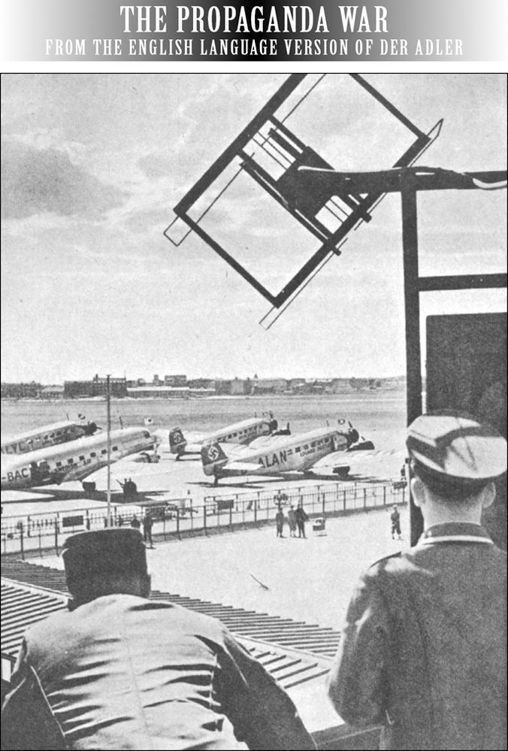

On the traffic control tower of the international airport Berlin-Templehof, from which the air police have an uninterrupted view of the whole traffic of the airdrome.