Chapter 17

The assassination of Caesar solved nothing. It merely set the stage for another destructive civil war. The conspirators and their friends hoped to wipe out all vestiges of Caesar the divinely sanctioned dictator and return to free republican aristocratic competition as equals. Many of Caesar’s allies and relatives wanted to take up his fallen mantle and use his popularity with the masses to assert their own dominance.

Marcus Antonius tries to take control, 44 to 43 b.c.e.

At Brutus’ insistence, the conspirators had planned nothing but killing the “tyrant,” Caesar. Brutus naively thought that the old free Republic would miraculously return to life afterward. Once the deed was done, however, the other senators panicked and stole away to their homes. The conspirators, becoming unsure of the public’s reaction, retired to the Capitol, erected barricades, and planned their future moves. Marcus Antonius (ca. 83–30 b.c.e.), Caesar’s relative (p. 285) and colleague in the consulship of 44, had been detained outside the chamber during the murder. He had quickly fled and hidden in fear that he might be the next victim. That night, sensing a chance to act, he improvised a bodyguard, came out of hiding, and persuaded Caesar’s widow, Calpurnia, to hand over all of her husband’s papers to him. In this way, he could claim to be the dead dictator’s legitimate representative.

Antonius has often been portrayed as a boozing, boorish bully of the worst kind. Any possible faults, weaknesses, and early follies, however, have been exaggerated by the propaganda of his enemies, especially Cicero and Augustus. It shaped the “official” version of events reflected in most surviving sources. Antonius had many good qualities as a soldier, general, and politician. His shrewdness and diplomacy helped to avoid serious trouble in the hours and days immediately following Caesar’s assassination.

M. Aemilius Lepidus had been outside the gates of Rome with a newly recruited legion. While Antonius was securing Caesar’s papers, Lepidus prepared to besiege the conspirators on the Capitol. The next morning, Antonius, having sensibly persuaded Lepidus to refrain, took charge of his troops. They then conferred with others of Caesar’s old officers and friends and established contact with the conspirators. Both sides also kept in communication with Cicero, the elder statesman. He had not been part of the conspiracy but had declared support for Caesar’s murderers immediately after the killing.

The outcome of the various conferences was a meeting of the senate on March 17. Antonius presided. Many senators wanted Caesar condemned as a tyrant, his assassination approved as necessary and just, his body flung into the Tiber, and all his acts declared null and void. Antonius urged them to reject such extremes; argued that they owed to Caesar their public offices, provinces, and political futures; hinted at the danger of popular uprisings; and pleaded that they listen to the people howling outdoors for vengeance and the blood of the conspirators. The appeal to fear and self-interest prevailed. The senators voted to give all Caesar’s acts the force of law and to proclaim an amnesty for the conspirators. That night, Antonius entertained Cassius, Brutus dined with Lepidus, and various other conspirators joined other Caesarians. The toasts that they drank seemed to proclaim more loudly than senatorial resolutions that peace and harmony prevailed.

On the next day, Antonius and Caesar’s father-in-law, Calpurnius Piso, persuaded the senators to make public Caesar’s will and grant him a state funeral. As many of the conspirators and their allies feared, publicizing Caesar’s will before the funeral stirred up the lower classes against the assassins. With news of Caesar’s murder spreading, the popular mood was turning ugly. More and more of his veterans and admirers among the rural plebs streamed into the city. When they learned how generously Caesar had provided for them and even one of his murderers (Decimus Junius Brutus), they became increasingly outraged at their patron’s killers. Caesar’s benefactions to the Roman People included turning his gardens across the Tiber into a public park and giving 300 sesterces in cash to each Roman citizen.

The will also made Antonius’ position more difficult in the long run. The chief beneficiary was not Antonius, a relative who was named only a minor heir, but Gaius Octavius Thurinus (63 b.c.e.–14 c.e.), Caesar’s grandnephew, the future Emperor Augustus. He was the son of C. Octavius, a senator born to a wealthy equestrian family, and of Atia, daughter of Caesar’s second older sister.

As the will required, Octavius took his uncle’s more distinguished name, Gaius Julius Caesar, but he did not follow the usual practice of adding to it the adjectival form of his former nomen, in this case Octavianus (Octavian). His enemies, however, sometimes used it in an attempt to deny him the magic of Caesar’s name and remind people of his less impressive equestrian origin. Now, to avoid the confusion that he actively sought between himself and Caesar, historians call him Octavian for the period after March of 44 b.c.e. and before he received the title Augustus in 27 b.c.e.

March 20 was the day of Caesar’s funeral. A recounting of Caesar’s mighty deeds on behalf of the Roman People aroused the feelings of the crowd for its lost leader. Next, Antonius, as consul, delivered the traditional eulogy. It probably was not so high flown as the reconstructions by Dio, Appian, and Shakespeare. As he progressed, however, he seems to have stirred up people’s passions with expression of his personal feelings for their hero. Then, with consummate showmanship at the very end, Antonius thrust aloft Caesar’s bloodied toga on the point of a spear and displayed on a rotating platform a wax image of the corpse with its oozing wounds. The people went completely berserk and seized Caesar’s bier. They surged toward the Capitol with the intention of interring him in the Temple of Jupiter. The authorities, however, turned them back. Returning to the Forum, they made a makeshift pyre near the Regia, Caesar’s headquarters as pontifex maximus. There they cremated his corpse and kept vigil over the ashes far into the night. Unfortunately, they also vented their rage by literally dismembering the hapless tribune C. Helvius Cinna. A friend of Caesar, he had come to the Forum to pay his respects. The crowd confused him with Caesar’s former brother-in-law, the praetor L. Cornelius Cinna, who had recently denounced Caesar and praised his assassins.

The Amatius affair

At this time, it seemed that Antonius would succeed Caesar. Although disappointed that he was not Caesar’s principal heir, he profited much from possessing the dictator’s private funds, papers, and rough drafts; much more, still, from his own skillful diplomacy and conciliatory spirit. Seeking to satisfy both friends and enemies of Caesar, he procured Caesar’s old position as pontifex maximus for Lepidus and was not violent toward the conspirators. The common people, however, were not happy with Antonius’ moderate course. A certain Amatius, apparently a wealthy man of Greek origin, had assumed the mantle of popular leadership. He convinced many people that he was actually a grandson of Marius and, therefore, a relative of Caesar. Having built up a considerable following, Amatius sponsored the creation of a monument, altar, and attendant cult to Caesar on the spot where he had been cremated in the Forum. Here the plebs settled disputes, swore oaths in Caesar’s name, and threatened violence against the conspirators. Clearly, the Forum was not a safe place for the latter, nor was Rome. Antonius quietly allowed them to proceed to their allotted provinces. Cassius and Marcus Brutus did not go directly but lingered among the towns of Latium in a vain effort to recruit support for their cause.

To the extent that Amatius had helped drive the conspirators from public life in Rome, he had been helpful to Antonius. At that point, however, his growing influence among Caesar’s veterans and the plebs was too great a threat to be tolerated. Indeed, that a “nobody” like Amatius should be wielding so much influence in the Forum must have offended all sides in the senate. Therefore, on April 13, with the senate’s full support, Antonius had Amatius arrested and summarily executed. The unauthorized shrine for Caesar’s worship was then destroyed.

Antonius further dissociated himself from the monarchic tendencies that Caesar had lately demonstrated. On his initiative, the office of dictator was forever abolished to assure the nobility that there would never be another Caesar. Then, with the senate concurring, Antonius took up the province of Macedonia and all the legions that Caesar had mobilized for his intended invasions of the Balkans and Parthia. Thus, Antonius had carefully steered between those who wanted to wipe out everything that Caesar had done and those who wanted to enshrine it in public worship. He had saved Rome from chaos after Caesar’s death and seemed to be solidifying his position as Rome’s preeminent leader.

Opposition from Cicero and Octavian

As consul and executor of Caesar’s estate, Antonius tried to bolster his position by showing special favor to friends like Lepidus. For example, he betrothed his eldest daughter to Lepidus’ son and obtained Lepidus’ appointment as pontifex maximus to replace Caesar. He also spent Caesar’s money for his own benefit. These actions disturbed men like Cicero, who wanted to guide the ship of state. They doubted his motives and worked against him. Even more, it was the unexpected challenge of Caesar’s principal heir, Octavian, which prevented Antonius from smoothly consolidating his supremacy. Caesar had sent Octavian to Epirus to train for the projected Parthian war. Only eighteen and of a rather delicate constitution, Octavian boldly determined to return to Italy and take advantage of any opportunity that the sudden turn of events might offer. He immediately demanded his inheritance, much of which Antonius had already spent. Seriously underestimating the young man, Antonius contemptuously rebuffed him. More determined than ever, Octavian undermined loyalty to Antonius among Caesar’s veterans. He played upon the magic of his new name and exploited their resentment of Antonius’ leniency with Caesar’s assassins.

Antonius tried to strengthen his position by obtaining passage of a law transferring command of Cisalpine and Transalpine Gaul from Decimus Brutus and Lepidus to himself for five years. Obviously, Antonius hoped to dominate Italy and Rome from this advantageous position, as Caesar once did. Many of Caesar’s old officers and soldiers did not want to fight each other or lose the political advantages of a united front. Their pressure kept Antonius and Octavian from intensifying their feud.

Antonius’ troubles still increased. His new provincial command aroused the fear and jealousy of Marcus Brutus and Gaius Cassius. In July, they demanded more significant provinces than Crete and Cyrene. His patience worn thin, Antonius refused their demands. He issued such strong threats that they abandoned Italy in order to recruit armies among Pompey’s old centers of support in the East. Moreover, Pompey’s son Sextus, who had escaped the Pompeian disasters in Africa and Spain, was now seizing control of western waters and raising another revolt in Spain. Meanwhile, Octavian had improved his standing as Caesar’s champion. He borrowed enough money to celebrate games scheduled in honor of Caesar’s victory at Pharsalus, since no one else would do it. After a comet fortuitously appeared during the celebrations, Octavian successfully encouraged the popular belief that it was Caesar’s soul ascending to heaven.

Antonius was getting worried. He began to resent Cicero’s absence from the senate, which many interpreted as criticism of Antonius’ actions. Indeed, Cicero did believe that the Republic was being subverted, a belief sharpened by his own lack of power. On September 1, 44 b.c.e., Antonius publicly criticized Cicero’s failure to attend meetings of the senate. In reply, Cicero delivered a speech mildly critical but irritating enough to provoke the increasingly sensitive Antonius to an angry attack upon Cicero’s past career. Cicero in turn wrote and published a very hostile but never-spoken second “speech.” He branded Antonius as a tyrant, ruffian, drunkard, and coward, a man who flouted morality by kissing his wife in public! Likening his speeches to Demosthenes’ famous orations against Philip of Macedon in fourth-century Athens, Cicero dubbed them Philippics. Twelve other extant Philippics followed, an eternal monument to Cicero’s eloquence but filled with misinformation and misrepresentation.

Rome had become unbearable for Antonius. Down to Brundisium, he went to meet four legions summoned from Macedonia, his original province. He intended to send them north to drive Decimus Brutus out of Cisalpine Gaul. The latter had refused to hand it over to Antonius despite the recent law. Antonius’ consular year (44 b.c.e.) was near its end. Should he delay, he might be left without a province or legions to command. Brutus and Cassius had proceeded to the East to take over rich provinces and their large armies. Cassius had defeated the governor of Syria and had driven him to suicide. Lepidus, now in Nearer Spain, was a shifty and suspect ally; Lucius Munatius Plancus, in Gallia Comata, and Gaius Asinius Pollio, in Farther Spain, were even less dependable. Even worse, Octavian had returned to Rome at the head of 3000 troops. Some of them were Antonius’ former soldiers who had now declared their loyalty to Caesar’s young heir. Octavius, however, soon alienated public opinion in a fiery speech against Antonius and turned to Cicero for help. Cicero eagerly embraced him as a weapon that he could discard after destroying Antonius.

The siege of Mutina, 44 to 43 b.c.e.

Antonius hastened north and trapped Decimus Brutus in Mutina (Modena). In January, the senate finally sent Decimus reinforcements under the two new consuls, Aulus Hirtius and Gaius Vibius Pansa, former comrades of Antonius under Caesar. At Cicero’s insistence, the senate also sent the young Octavian, granted propraetorian power and senatorial rank. He was promised rich rewards: money and land for his legitimized troops; for himself, the right to stand for the consulship when he reached the age of thirty-three, ten years before the legal age.

The three enemy armies finally forced Antonius to abandon the siege of Mutina but could not prevent his retreat across the Alps into southern Gaul. There he hoped to gain the support of Lepidus and Plancus. Both consuls lost their lives at Mutina: Hirtius, killed in battle; Pansa, later dying of his wounds. Their deaths cleared the field for Octavian.

Cicero had high hopes after Mutina. The enemy was on the run. The armies of the Republic would shortly track him down. The entire East fell into the hands of Brutus and Cassius. Decimus Brutus still held Cisalpine Gaul, and Sextus Pompey was supreme at sea. Soon, Cicero and his friends would close the ring and dispose of Octavian, too. Then would come the day for the glorious restoration of the Republic—so Cicero believed. He was cruelly deceived.

Antonius’ enemies miscalculate

After Mutina, the senate declared Antonius a public enemy. Upon Brutus and Cassius, it conferred superior command (imperium maius) over all Roman magistrates in the East. To Decimus Brutus, the dominant senators voted a triumph and supreme command over all the armies in Italy. To Sextus Pompey, they extended a vote of thanks and an extraordinary command over the Roman navy. For Octavian, however, they proposed only a minor triumph, ovatio, and an inferior command. Even that proposal they finally voted down. They also refused to reward his troops and repudiated the promised consulship. Through their own folly, they drove Octavian back into the arms of the other Caesarians.

Octavian seizes the initiative, July 43 b.c.e.

To punish the slights and studied disdain of senatorial leaders, Octavian marched on Rome with eight legions. Two legions were brought over from Africa to defend his senatorial enemies. The legions deserted to him. All resistance collapsed. Octavian, not yet twenty, entered Rome and obtained the election of himself and Quintus Pedius as suffect (substitute) consuls to fill out the deceased consuls’ terms. Pedius was Caesar’s nephew, his former legate, and heir to one-eighth of his estate.

Octavius’ first act as consul was to rifle the treasury and pay each soldier 2500 denarii; the next was the passage of a law instituting a special court to try Caesar’s murderers and Sextus Pompey. In order to claim patrician status, he also sought to make himself Caesar’s adopted son by more than just a provision in Caesar’s will. Tribunes loyal to Antonius had blocked a previous attempt in 44. Now, with Antonius out of Rome, Octavian went through a formal adoption ceremony that normally would have been valid only if Julius Caesar had been alive to participate. Soon, Octavian would be too powerful for people to quibble over technicalities. Now, however, he still needed allies. To obtain them, he had the decree against Antonius and Lepidus revoked. That done, he hastened north to see them.

Meanwhile, Antonius had been neither idle nor unsuccessful. His debacle at Mutina had brought out the best in him. After a hard and painful march into southern Gaul, he confronted Lepidus’ far larger army. Antonius cleverly played upon the sympathies of Lepidus’ men, many of whom had served with him under Caesar in Gaul. Begrimed, haggard, and thickly bearded, he stole into the camp of Lepidus and addressed the men. Thereafter, the two armies began gradually to fraternize. Soon, Antonius was in real command. He used the same tactics in approaching the army belonging to L. Munatius Plancus, Caesar’s former legate and the governor of Gallia Comata. Then, Decimus Brutus was deserted by his army. Brutus himself attempted to escape to Macedonia, but he was trapped and slain by a Gallic chief.

When Antonius and Lepidus returned to Cisalpine Gaul with twenty-six legions, they found Octavian already there with seventeen. Although they greatly outnumbered the young pretender, they did not try to fight him. They feared that their men might refuse to fight against one who bore Caesar’s name. Lepidus arranged a conference instead.

The triumvirate of Octavian, Antonius, and Lepidus, 43 to 36 b.c.e.

After some preliminary negotiations, the three leaders met near Bologna. They agreed upon a joint effort. They would form themselves into a three-man executive committee with absolute powers for five years for the reconstruction of the Roman state (tresviri rei publicae constituendae). The lex Titia to that effect was carried by a friendly tribune on November 27, 43 b.c.e. In name, the consulship survived along with its traditional prestige, title, and conferment of nobility. In fact, its powers were greatly reduced. Octavian and Pedius agreed to resign the office. Two nonentities took their place. Also, to strengthen the alliance, Octavian married Antonius’ step-daughter Claudia. She was the daughter of Antony’s wife, Fulvia, whom he had married in either 47 or 46. Claudia’s father was Fulvia’s first husband, Publius Clodius. Fulvia’s second husband, Curio, had died fighting for Caesar in 49 (p. 288).

Octavian was not the dominant member in the triumvirate. Antonius, who had one less legion than Octavian, insisted that he be given four more and Octavian only three. Thus Octavian was limited to parity with Antonius. They both took their additional legions from Lepidus. As for the provinces, Antonius secured Cisalpine Gaul and Gallia Comata. Lepidus obtained Transalpine Gaul and the two Spains. Octavian received a more modest and doubtful portion: North Africa and the islands of Sicily, Sardinia, and Corsica, all disputed and some already seized by the outlawed Sextus Pompey.

The proscriptions, 43 b.c.e.

A few days later, the triumvirs instituted a proscription as cold-blooded as that of Sulla. Among their victims were 130 senators and, if Appian is correct, 2000 equites. The excuse alleged was the avenging of Caesar’s murder. The reality is different. The triumvirs needed money for their forty-three legions and for the inevitable campaign against Marcus Brutus and Gaius Cassius. They soon found that the confiscated wealth of their victims was insufficient for their needs. Therefore, they imposed a capital levy upon rich women, laid crushing taxes upon the propertied classes in Italy, and set aside the territories of eighteen of the richest cities in Italy for veteran settlements. The women, at least, protested vociferously and won a significant reduction of their impost (pp. 327–8).

In addition to the triumvirs’ need for money was a desire to wipe out political enemies. Their most distinguished victim, at Antonius’ insistence, was Cicero. Unlike some of the proscribed, he lingered until too late. Abandoning his final flight, Cicero calmly awaited his pursuers along a deserted road and was murdered on December 7, 43 b.c.e., a martyr to the cause of the dying Republic. The Rostra from which Cicero had so often spoken saw his head and at least the gesturing right hand nailed upon it. Fulvia, often a victim of Cicero’s sharp tongue, is said to have taken vengeance later by ripping it out and sticking a hairpin through it.

The consolidation of power, 43 and 42 b.c.e.

To buttress their regime of terror and violence, of confiscation and proscription, the triumvirs packed the senate with men of nonsenatorial origin who would become their loyal clients. They made the consulship the reward of graft or crime and nominated several pairs of consuls in a single year. To the praetors, whom Caesar had increased to sixteen, they added fifty more.

The consuls of 42 were to be Lepidus and Caesar’s old legate Munatius Plancus. Another legate and C. Antonius Hybrida became censors. Hybrida, Cicero’s suspect consular colleague in 63, was Antonius’ uncle and former father-in-law.

Formally taking office January 1, 42 b.c.e., the triumvirs compelled the senate and the magistrates to swear an oath to observe Caesar’s acts. They also provided for building a temple to Caesar on the site of the altar set up by Amatius in the Forum. Caesar became a god of the Roman state under the name Divus Julius, the Deified Julius. Consequently, Octavian called himself Divi Filius (“Son of a God”). Antonius was appointed Caesar’s special priest, flamen, but realized the old nobility’s strong dislike of Caesar’s deification. Hoping, perhaps, to deflect some of their anger to Octavian, he delayed being inaugurated until 40 b.c.e.

The Battle of Philippi, 42 b.c.e.

After crushing all resistance in Italy, the triumvirs made war on Brutus and Cassius. Those two had accumulated nineteen legions and had taken up a strong position at Philippi on the Via Egnatia in eastern Macedonia. Their navy dominated the Aegean Sea. Nevertheless, in the fall of 42, Antonius and Octavian, eluding enemy naval patrols, landed their forces. Brutus defeated the less-able Octavian, but Antonius defeated Cassius, who, unaware of Brutus’ victory, committed suicide. Instead of letting winter and famine destroy the enemy, Brutus yielded to his impetuous officers and offered battle three weeks later. After a hard and bloody battle, Antonius’ superior generalship prevailed. Brutus took his own life.

Antonius, the real victor, received the greatest share of Rome’s empire. He took all of the East and the Gallic provinces in the West, although he later gave up Cisalpine Gaul. It was then merged with Italy proper. Lepidus, who was reported to have negotiated secretly with Sextus Pompey while Antonius and Octavian were at Philippi, now began to lose ground. He had to give Narbonese (Transalpine) Gaul to Antonius and the two Spains to Octavian. Still, they allowed him to save himself by conquering North Africa. Octavian returned to deal with problems in Italy and reconquer Sicily and Sardinia, which Sextus Pompey had seized.

Antonius and the East, 42 to 40 b.c.e.

Antonius went to the easternmost provinces to regulate their affairs and raise money promised to the legions. He extracted considerable money from the rich cities of Asia by arranging for nine years’ tribute to be paid in two. He also set up or deposed kings as it seemed advantageous to himself and Rome. Finally, in 41, he came to Tarsus in Cilicia, to which he had summoned Cleopatra. She had returned to Egypt from Rome about the time when Brutus and Cassius fled. She needed to protect her kingdom: both the Caesarians and anti-Caesarians would be seeking its resources against each other. She had tried to placate both sides without committing herself openly to either in the struggle that had culminated at Phillipi. Now she needed to convince the chief victor that he could rely on her in the future. She appeared in a splendid barge with silvery oars and purple sails, herself decked out in gorgeous clothes and redolent with exquisite perfumes. It is easy to follow propaganda and legend and see Antonius hopelessly seduced by a sensuous foreign queen. Passion notwithstanding, however, both pursued rational political interests. Each had something to gain by cooperating with the other: Cleopatra, the support of Roman arms against her rivals; Antonius, Egyptian wealth to defray the costs of a projected war against Parthia and rivalry with Octavian. In the meantime (40 b.c.e.), Cleopatra bore him a set of twins (p. 311).

Octavian in Italy vs. Fulvia and L. Antonius, 42 to 41 b.c.e.

Octavian probably realized that Italy was still the key to ultimate control of Rome’s empire, despite the problems that awaited him there. The eighteen cities previously earmarked for soldiers’ settlement proved inadequate to meet the needs of the 100,000 demobilized veterans who returned with him. The evicted owners angrily protested. Expanded confiscations, including now as many as forty towns, further increased the groundswell of discontent. The populace of Rome was also in a disturbed and angry mood. Sextus Pompey still controlled the seas and began to shut off grain supplies. Discontent, confusion, insecurity, and want threatened the stability of the state. Soldiers and civilians were at each other’s throats. At one point, Octavian himself almost suffered violence at the hands of a battling mob.

In 41 b.c.e., intrigue aggravated Octavian’s situation. Both Fulvia, Antonius’ firebrand wife, and his brother Lucius, one of the consuls, worked to ensure that Antonius’ veterans did not forget him even as Octavian was making sure they received their land allotments. At the same time, Lucius was sympathetic to the plight of the displaced landowners. Although Fulvia at first disagreed with Lucius’ decision to align the Antonian cause with those opposed to Octavian, (so the story goes) she was persuaded once it was pointed out that Antonius himself might return home from Egypt if war broke out.

The Perusine War, 40 b.c.e.

Despite the repeated efforts of senators and of soldiers on both sides, Octavian and Lucius took up arms. Although all parties wrote to Antonius, it is not clear what his reaction to events in Italy was. Octavian’s loyal generals Marcus Vipsanius Agrippa and Quintus Salvidienus besieged Lucius in the Etruscan hill town of Perusia (Perugia); Fulvia was elsewhere, frantically trying to persuade Antonius’ legates to bring aide to Lucius. Two marched from Gaul and got close enough to Perusia that the besieged troops could see the fires in their camps, but Octavian’s generals blocked the way. Eventually, starvation forced Lucius to surrender. Although Octavian ruthlessly executed all but one member of Perusia’s town council, he spared the lives of Lucius and his troops, and of Fulvia and of Antonius’s children. He sent Lucius as governor to Spain, where he soon died. He allowed Fulvia to leave Italy with the children and join her husband.

Because Antonius’ remaining legate in the two transalpine Gallic provinces had now died, Octavian sent some of his victorious forces to seize them. The dead legate’s son surrendered without a fight, and Agrippa was placed in charge. Now, militarily, Octavian was virtually in charge of all western provinces in Europe.

Still, it was not the end of troubles for Octavian. Pillage, fire, mass executions, and military control of provinces had neither solved his problems nor made him safe from danger. His actions served only to increase hatred and discontent in a land still seething with revolt and held in the grip of famine, turmoil, and despair. The hostile fleets of Sextus Pompey menaced Italy’s coasts, assailed the provinces, and interrupted grain shipments.

The Pact of Brundisium, 40 b.c.e.

Octavian, in his extremity, sought accommodation with Sextus. He had divorced Claudia, Fulvia’s daughter, in the build-up to the conflict that ended at Perusia. In her stead, he married Scribonia, about ten years older than he. Scribonia’s brother was one of Sextus’ important political allies and was the father of his wife. Apparently, Octavian was unaware that Sextus was making overtures to Antonius. The latter had been in Egypt while Octavian was fighting his brother and Fulvia. Antonius had learned that the Parthians had overrun Syria, Palestine, and parts of Asia Minor. Not yet prepared to fight the Parthians, Antonius sailed for Greece to confer with Fulvia once she left Italy. Fulvia, who died shortly after their reunion, persuaded him to receive envoys from Sextus Pompey and accept the proffered alliance. Only then did Antonius proceed to Italy to recruit legions for a war against the Parthians.

By previous agreement, Antonius and Octavian were to use Italy as a common recruiting ground. How worthless that agreement was Antonius discovered when he found Brundisium closed against him by Octavian’s troops. Frustrated and angry, he besieged the city. Simultaneously, his republican ally, Sextus Pompey, also struck southern Italy. When Octavian appeared at Brundisium to oppose his colleague, Caesar’s old legions refused to fight. They fraternized instead. There followed negotiations, conferences, and finally a new agreement known as the Pact of Brundisium, which renewed the triumvirate. A redistribution of provinces added Illyricum to the other provinces that Octavian controlled. Antonius received the East. Lepidus retained Africa. Italy was to remain, theoretically at least, a common recruiting ground for all three. To seal the pact, Antonius married Octavia, the freshly widowed sister of Octavian. The covenant between the two powerful rivals filled Italy with hopes of peace.

The hopes were premature. Sextus Pompey believed that Antonius had played him false. He threatened Rome with famine. Taxes, high prices, and food shortages provoked riots. The people clamored for bread and peace. When Antonius and Octavian prepared to attack Sextus, popular reaction forced them to negotiate with him. Sextus’ mother, Pompey the Great’s ex-wife Mucia, played a crucial role in setting up the negotiations.

The Treaty of Misenum, 39 b.c.e.

At Misenum (near Naples) in the autumn of 39 b.c.e., the triumvirs met with Sextus Pompey, argued, bargained, and banqueted. They agreed to let him retain Sicily and Sardinia, which he had already seized and gave him Corsica and the Peloponnesus as well. They also allowed him compensation for his father’s confiscated lands and promised him a future augurate and consulship. In return, he agreed to end his blockade of Italy, supply Rome with grain, and halt his piracy on the high seas.

The position of Octavian was improving. The Roman populace and Caesar’s veterans favored him. Moreover, time was on his side. Years of Antonius’ absence in the East would cause his influence to wane in the West.

The predominance of Antonius, 39 to 37 b.c.e.

For the present, however, the West looked bright to Antonius. His influence was especially strong among the senatorial and equestrian orders, old-line republicans, and most men of property throughout Italy. Sextus Pompey would surely counter the growing power of Octavian—so thought Antonius as he and Octavia set out for Athens. He spent two winters enjoying domestic happiness and the culture of that old university town. From there, he directed Ventidius Bassus and Herod (client king of Judea since 40 b.c.e.) to drive out Parthian invaders from Syria, Palestine, and Asia Minor.

By not offering battle except from advantageous positions on high ground, Ventidius negated the Parthian strength in archers and cataphracts (mail-clad cavalry). He shattered the Parthian forces in three great battles and rolled them back to the Euphrates. There he wisely stopped. Antonius, however, made plans to subjugate the Parthians completely and avenge Crassus’ defeat at Carrhae. In 37 b.c.e., Antonius sent another of his commanders to pacify Armenia, on Parthia’s northern flank. New troubles in the West, however, compelled Antonius to postpone his invasion of Parthia.

Livia strengthens Octavian in the West, 39 and 38 b.c.e.

The Treaty of Misenum had brought Italy peace and a brief respite from piracy, shore raids, and famine. To Octavian, it meant even greater benefits: republican aristocrats of ancient lineage, allies worth his while to court and win, returned home. The peace was of short duration, however. Sextus Pompey was upset with Antonius’ delay in handing over the Peloponnesus and generally felt slighted by the triumvirs. He resumed the blockade of Italy later in 39. War threatened again, and Pompey’s ill-will grew when Octavian suddenly divorced Scribonia. For love and politics, Octavian promptly married Livia Drusilla (58 b.c.e.–29 c.e.). She was young, beautiful, rich, politically astute, and anxious to secure the future prominence of her family and her children. She was also hugely pregnant with her second son by her first husband, Tiberius Claudius Nero, who had fought against Octavian at Perusia. Now, both he and Livia decided to pin their families’ futures on Octavian. By mutual consent, the two divorced in 39 b.c.e. Octavian obtained a ruling from the pontiffs that he and Livia could become betrothed right away. They married in January of 38, once Livia gave birth. Octavian had been so anxious to pursue an advantageous union with Livia that he had divorced Scribonia on the very day that she bore him his only child, Julia, whom he would later use in numerous dynastic marriages. Although Livia bore him no children (there was a stillbirth), she became one of Octavian’s most trusted advisors. He consulted her at every major turn for the rest of his life.

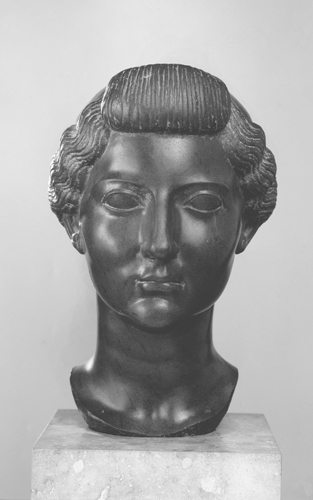

FIGURE 17.1 Livia, wife of Octavian and future empress.

Octavian’s marriage to Livia and the noble connections that she secured through her connections to the Claudian gens through her father and her first husband helped to broaden Octavian’s support among leading senators and to undermine that of Antonius. At the same time, Octavian’s origin from an equestrian family of Italian background was an asset against the noble-born Antonius. Octavian cultivated friends among the equites, who had long resented the exclusivity of the old republican nobility. From this class came two of his most loyal and important supporters: the wealthy patron of the arts who helped to mold public opinion in his favor, Gaius Cilnius Maecenas, and the architect of many of his military victories, Marcus Vipsanius Agrippa. Moreover, Octavian won strong support in the countryside of Italy, from which Roman armies were recruited.

War with Sextus Pompey, 38 b.c.e.

In 38, Octavian determined to destroy Sextus Pompey once and for all. He scored an initial coup when Pompey’s traitorous governor of Sardinia defected with his province. Nevertheless, a little later that year, Octavian attempted an invasion of Sicily. It was a fiasco. Pompey destroyed two of his fleets. These reverses compelled Octavian to recall the indispensable Agrippa from Gaul and to invoke the aid of Antonius. The latter was angry at Octavian for going to war contrary to his advice and for causing a delay in his own campaign against the Parthians. Still, he loyally left Athens with a large fleet and came to his aid.

The Treaty of Tarentum and defeat of Sextus Pompey, 37 and 36 b.c.e.

The two triumvirs, resentful and suspicious of each other, met at Tarentum in 37. Through the patient diplomacy of Maecenas and the influence of Octavia, they concluded the Treaty of Tarentum. It renewed their triumvirate, which had lapsed on December 31, 38 b.c.e., for another five years. Octavian betrothed his two-year-old daughter, Julia, to Antyllus, Antonius’ older son by Fulvia. In exchange for the 120 ships that Antonius now contributed to the war against Sextus Pompey, Octavian promised 20,000 Roman soldiers for service in the East. Antonius never got them. In an amphibious attack on Sicily, Octavian suffered a crippling defeat, but Agrippa crushed Pompey in a great naval battle at Naulochus, near the Straits of Messana. Sextus barely escaped to Asia Minor.

The downfall of Lepidus, 36 b.c.e.

Octavian had already overcome one rival, and soon he would another. Lepidus had come to reclaim his province of Sicily with twenty-two legions. Hungry for glory, he insisted on accepting the surrender of the island in person. When Octavian objected, Lepidus ordered him out of the province. Bearing the magic name of Caesar, Octavian boldly entered the camp of Lepidus and persuaded his legions to desert. Then he stripped Lepidus of any real power and committed him to comfortable confinement at the lovely seaside town of Circeii in Latium. Lepidus, still pontifex maximus, wisely lived there peaceably for another twenty-four years.

The triumphant return of Octavian, 36 b.c.e.

Rome joyously welcomed home the victorious Octavian. He had ended civil wars in the West, restored the freedom of the seas, and liberated Rome from the danger of famine. Although he had helped crush the liberty of the old nobility, he now brought the blessing of strong, ordered government to a populace exhausted by civil war. For his part, he gave vague promises of a future restoration of the civil state (res publica). People heaped honors upon him, even adoration and divine epithets. Statues of him were placed in Italian temples; a golden one was set up in the Roman Forum, and he received the sacrosanctity of a plebeian tribune in addition to the military title of Imperator Caesar, which he had previously usurped.

Antonius and Cleopatra rule the East, 37 to 32 b.c.e.

Antonius had been tricked into spending the better part of two years helping Octavian win mastery of the West while he gained nothing. In 37 b.c.e., he returned to the East, to which he henceforth committed himself fully in order to secure his independent power. Later that year, his commitment was strikingly symbolized by a public ceremony with Cleopatra at Antioch. That act was not a marriage in any Roman sense, and he did not divorce Octavia. She was too politically valuable, and her status as his legitimate wife was not threatened by his liaison with a noncitizen.

By becoming co-ruler of the only remaining independent successor state of Alexander the Great’s empire, Antonius was able to lay legitimate claim to that empire, much of which the Parthians controlled. This relationship also allowed Antonius to manipulate popular religious ideas to his advantage. He had already sought favor with the Greeks by proclaiming himself to be Dionysus, the divine conqueror of Asia in Greek mythology. Now, for the Greeks, he and Cleopatra became the divine pair, Dionysus and Aphrodite. To the native Egyptians, they appeared as Osiris and Isis.

The religio-political significance of their relationship is also revealed by Antonius’ public acknowledgment and renaming of the twins whom Cleopatra had previously borne to him. They became Alexander Helios (Sun) and Cleopatra Selene (Moon). The choice of Alexander as part of the boy’s name clearly shows the attempt to lay legitimate claim to Alexander the Great’s old empire. The names of Helios and Selene had powerful religious implications for his and Cleopatra’s political positions. According to Greek belief, the Age of Gold was connected with the sun deity. In some Egyptian myths, Isis (the role claimed by Cleopatra) was mother of the sun. By the Greeks, she was equated with the moon. Finally, the Parthian king bore the title Brother of the Sun and Moon, who were powerful deities in the native religion. Accordingly, Antonius probably was identifying these potent Parthian symbols with himself in order to strengthen his anticipated position as king of conquered Parthia.

Reorganization of eastern territories

In the past, the client kingdoms of the East had owed allegiance not to Rome but to their patron, Pompey the Great. The Parthian invasion had clearly revealed the weakness of their relationship to Rome. Antonius did not disturb the provinces of Asia, Bithynia, and Roman Syria, but he assigned the rest of the eastern territories to four client kings. They were dependent on Rome yet strong enough by means of their heavily armed and mail-clad cavalry to guard their frontiers against invasion.

To Cleopatra, he gave part of Syria along the coast, Cyprus, and some cities in Cilicia, territories not more extensive than those given to others but immensely rich. Antonius firmly rejected her demand for Judea, the kingdom of Herod I, although he did give her Herod’s valuable balsam gardens at Jericho. Cleopatra had now regained control over much of what Ptolemaic Egypt had ruled at its height under Ptolemy II Philadelphus (283–246 b.c.e.). She emphasized this point by naming the son whom she bore to Antonius in 36 b.c.e. Ptolemy Philadelphus.

The Parthian campaign and its aftermath, 36 to 35 b.c.e.

Antonius’ strengthened ties to Cleopatra in 37 had greatly bolstered his position in the reorganized East as he prepared for his major invasion of Parthia. He was, however, neither subservient to her nor dependent upon the financial resources of Egypt at that point. He prepared his expedition with the resources of the Roman East and embarked upon it against the advice of Cleopatra in 36. He should have listened to her. The expedition was a disaster. King Artavasdes II of Armenia, pursuing his own interests, withdrew his support from Antonius at a critical point. Antonius lost his supplies and 20,000 men.

Despite his losses, Antonius was still strong in the East and the dominant partner in a divided empire. He also had considerable popular support remaining in Italy and an impressive following among the senators, including Caesarians, Pompeians, and such staunch republicans as Cn. Domitius Ahenobarbus, Cato’s grandson L. Calpurnius Bibulus, and several other kinsmen of Cato and Brutus. Nevertheless, the defeat in Parthia and, as a result, his increasing dependence on Cleopatra’s resources provided plenty of fuel for Octavian’s propaganda machine. Octavian refused to send the four legions that he had promised in the Treaty of Tarentum (p. 310). Also, he returned only the 70 ships surviving from the 120 that Antonius had lent him against Sextus Pompey. Even Sextus tried to take advantage of Antonius’ Parthian defeat by attacking Asia Minor, where he was finally captured and killed in 35.

The importance of Octavia, 35 to 32 b.c.e.

Octavia remained intensely loyal to Antonius, despite his liaison with Cleopatra. She set out with a large store of supplies and 2000 fresh troops to aid her husband in the spring of 35. At Athens, a message from Antonius ordered her to return to Rome but still send on the troops and supplies. It was a bitter blow. Yet, she quietly obeyed. Antonius restored his tattered military laurels by conquering Armenia in 34. While Octavia dutifully looked after his interests in Rome, Antonius spent the winter of 33 and 32 with Cleopatra in Ephesus to reinforce his position in the East. Then he carried off King Artavasdes to Egypt and celebrated an extraordinary triumph at Alexandria. In a ceremony known as the Donations of Alexandria, he gave Cleopatra and her children additional territories and recognized Cleopatra as supreme overlord of all eastern client kingdoms. She soon asserted her authority by having Artavasdes executed.

The approach and renewal of civil war, 32 to 30 b.c.e.

Meanwhile, the prospect of war loomed larger. Octavian had built up his forces and military reputation with a successful campaign in Illyricum. Several of his generals also earned triumphs in Spain and Africa. Still, it would not be easy for even so crafty a politician as Octavian to go to war against Antonius. The latter, with both consuls of 32 b.c.e. and half the senate on his side, was elected consul for 31. To prove Antonius a menace to Rome was difficult. Cleopatra, however, was more vulnerable. She was portrayed as a detestable foreign queen plotting to make herself empress of the world. Antonius was made to seem only her doting dupe.

The breach between the two triumvirs constantly widened. Each hurled recriminations against the other, charges of broken promises, family scandal, and private vices. Poets, orators, lampoonists, and pamphleteers entered the fray at the expense of truth and justice. Both protagonists, just like Pompey and Caesar, were too proud to tolerate the appearance of backing down before each other. Truth lies buried beneath a thick, hard crust of defamation, lies, and political mythology. Had Antonius instead of Octavian won the eventual civil war, the official characterizations of the protagonists would have been equally fraudulent but utterly different. Antonius would have been depicted as a sober statesman and a loving husband and father, not a sex-crazed slave of Cleopatra; the savior of the Republic, not a tyrant striving to subject the liberties of the Roman People to Eastern despotism.

Earlier, Antonius had sent the two friendly consuls of 32 b.c.e. dispatches requesting the senate’s confirmation of all his acts in the East and his donations to Cleopatra and her children. He even promised, for propaganda purposes, to resign from the triumvirate and restore the Republic. Fearing serious repercussions from the first two items, the two consuls withheld the contents of the dispatch, but one roundly condemned Octavian in a bitter speech in the senate. A few weeks later, Octavian appeared before the senate with an armed bodyguard. He denounced Antonius and dismissed the senate. The consuls and perhaps more than 300 senators fled from Rome to Antonius at Ephesus.

The divorce of Octavia and the will of Antonius

By early summer, Antonius and Cleopatra had moved their huge armada across the Aegean to Athens. Antonius probably realized that if he was to have the support of the eastern populace and the forces they provided, he needed to show his full commitment to them. Finally, then, he sent Octavia a letter of divorce. Some of Antonius’ allies had begun to have doubts as his cause became more and more dependent on the East and Cleopatra. Divorcing Octavia was the last straw for the ever-foresighted survivor L. Munatius Plancus. To ingratiate himself with Octavian, he brought a precious gift, the knowledge that Antonius had deposited his last will and testament with the Vestal Virgins. Octavian promptly and illegally extorted it from them. He read it at the next meeting of the senate. The will allegedly confirmed the legacies to Cleopatra’s children, declared that her son Caesarion was a true son and successor of Julius Caesar, and provided for Antonius’ burial beside Cleopatra in the Ptolemaic mausoleum at Alexandria. Genuine or fraudulently altered, the will gave Octavian his greatest propaganda victory.

Octavian declares war, 32 b.c.e.

Capitalizing on popular revulsion against Antonius, Octavian now resolved to mobilize the power of the West against the East. By various means, he contrived to secure an oath of personal allegiance from the municipalities first of Italy and then of the western provinces. Fortified by this somewhat spurious popular mandate, he obtained a declaration stripping Antonius of his current imperium and upcoming consulship for 31 b.c.e. Late in the fall of 32 b.c.e., to avoid the appearance of initiating another civil war of Roman against Roman, war was declared on Cleopatra. Octavian then spent the winter in preparation for a spring offensive.

Meanwhile, Antonius and Cleopatra had not been idle. Toward the end of 32 b.c.e., they set up camp at Actium, at the entrance to the Ambracian Gulf. There lay the main part of their fleet. Antonius seemed much stronger than his foe. He was an excellent general and commanded an army numerically equal in both infantry and cavalry to that of Octavian. He also had one of the biggest and strongest fleets the ancient world had yet seen. His weakness, however, overbalanced his strength. Although most legionaries admired Antonius as a man and soldier, they hated war against fellow citizens. His Roman officers detested Cleopatra and privately cursed Antonius for not being man enough to send her back to Egypt.

The Battle of Actium, September 2, 31 b.c.e.

Marcus Agrippa, Octavian’s second in command, had set up a blockade that caused a severe famine and an outbreak of plague in Antonius’ camp during the summer of 31. Antonius’ commanders were divided and quarreling among themselves; his troops were paralyzed by treason and desertions. Apparently, he and Cleopatra decided to make a strategic retreat. While they took only the faster, oared ships and broke out of the bay, the rest of the army, it seems, was to retreat overland to Asia Minor. Cleopatra’s squadron of sixty ships got clean away, and Antonius managed to follow with a few of his ships. The rest became too involved with those of Agrippa, who sailed out to block them. Antonius’ men soon surrendered. Octavian’s victory was so complete that he felt no immediate need to pursue the fugitives to Egypt. He turned his attention to mutinous legions in Italy instead and recrossed the Adriatic to appease their demands for land and money.

The last days of Antonius and Cleopatra, 30 b.c.e.

In the summer of 30 b.c.e., Octavian, now desperate for money, finally went to Egypt. The legions of Antonius put up only brief resistance. Alexandria surrendered. Cleopatra’s son Caesarion and Antonius’ son Antyllus were quickly murdered. Antonius committed suicide. A few days later, Cleopatra followed, arousing joy, relief, and even grudging admiration among Romans like the poet Horace (Odes, Book 1.37). Thus passed the last of the Ptolemies, a dynasty that had ruled Egypt for almost 300 years. Egypt became part of the Roman Empire. Octavian was now undisputed master of the Mediterranean World.

The end of the Republic

After 30 b.c.e., the forms of the Republic’s political institutions, which shared power among the citizen assemblies, collegiate magistracies, and senate of aristocratic equals, would still remain. In reality, power had become concentrated in the hands of one man, the total antithesis of republicanism. From 29 b.c.e. onward, Octavian would shrewdly manipulate those forms while turning himself into Augustus, Rome’s first emperor, and ending the Republic forever.

Many reasons have been offered to explain why the Republic collapsed. Ancient authors like Sallust, Cicero, and Plutarch offered moral explanations that modern historians have often favored: having conquered most of the Mediterranean world, the Romans no longer had the fear of external enemies to restrain them; they lost their old virtues and self-discipline through the debilitating influences of the alien cultures to which they had become exposed; great wealth and power corrupted them. Some modern historians have seen the Republic’s fall primarily as the work of Julius Caesar in supposedly single-minded pursuit of a long-planned monarchic design or mystical sense of destiny.

Others have seen the problem primarily in institutional terms: the institutions of a small agrarian-based city-state were inadequate for coping with the great problems that came with vast overseas expansion. Some, however, would argue that there can be no general explanation for the Republic’s fall. It was essentially an accident: the Republic had weathered the upheavals from the Gracchi to Sulla; it had made the necessary adjustments to changed conditions while maintaining its basic character; it was functioning quite normally and would have continued to do so if two egotistical, stubborn, and miscalculating men had not chanced to precipitate the civil war that destroyed it.

None of these explanations is adequate. To a certain extent, all history is accident, but that does not mean that important general causes cannot be found. To understand how the Republic finally came to an end, one must look at the outbreak of the particular civil war that destroyed it in the context of general, long-term social, economic, political, and cultural developments (described in Chapters 10 and 18).

Those who emphasize the inadequacy of the old Republic’s institutions for coping with the new problems of a vast empire have an important point. Institutions that arise from or are designed for a particular set of circumstances will eventually cease to function satisfactorily under radically altered circumstances. For example, the old eighteenth-century New England town-meeting form of government is totally impractical in twenty-first-century Boston. Old institutions may be modified and adapted up to a point and remain basically the same. Still, that process can be carried only so far before they are transformed into something quite different. After 400 years of change, the British monarchy of Queen Elizabeth II is not the same as that of Elizabeth I.

Similarly, after 200 years, the old Roman republican system had ceased to work. Minor modifications had not helped to preserve it. Increased numbers of lower magistrates increased the intensity of the competition for the annual consulships, which remained fixed at two. Annually elected consuls were not capable of waging long-term overseas wars and governing distant provinces in alien lands. Using practically independent promagistrates and extraordinary commanders, often with extended terms of duty, to handle these problems was dangerous. It gave individuals unprecedented amounts of economic, political, and military power. They could then overcome normal constraints and destroy the equilibrium within the ruling elite that had kept the old system in balance. The tremendous social and economic changes accompanying 200 years of imperialism had also greatly altered the composition of the popular assemblies. They became more susceptible to ambitious and/or idealistic manipulators pursuing personal advantage over their peers, the alleviation of legitimate grievances, or both. Sulla’s attempt to restore the old system in the face of changed conditions had merely doomed it to failure.

Still, institutional inadequacies in the face of changed conditions do not wholly explain the fall of the Roman Republic. Institutions do not exist or function apart from the people who control them. The character, abilities, and behavioral patterns of the people who run vital institutions do have a bearing on how well those institutions function under given circumstances. For example, during the Great Depression, the American presidency was not an effective instrument of popular leadership under Herbert Hoover, but it was under Franklin Roosevelt, no matter how one judges the ultimate worth of his policies. Therefore, individual leaders like Julius Caesar are important. Although he was not pursuing any mystical sense of destiny or long-meditated monarchic ambitions, he did have particular personality traits such as self-assurance, decisiveness, and unconventionality that made him particularly successful in the political and military competition destroying the Republic.

Nevertheless, individual differences should not be overemphasized. Caesar was operating within a general cultural context. It shaped his thoughts and actions in ways that were typical of men like Pompey, Crassus, Catiline, Clodius, Cato, Curio, Brutus, Antonius, and Octavian. They were all deeply concerned with the personal gloria, dignitas, and auctoritas that were the most highly valued prizes of their era. In the early Roman Republic, the great emphasis on and competition for gloria, dignitas, and auctoritas produced generations of leaders who eagerly defended the state against hostile neighbors; expanded Roman territory to satisfy a land-hungry population; and ably served the state as priests, magistrates, and senators. So long as Rome expanded within the relatively narrow and homogeneous confines of Italy, there was little opportunity for aristocratic competition at Rome to get out of hand; the values that fueled it were reinforced; and the highly desired stability of the state was maintained. These same values then contributed to overseas expansion along with accompanying disruptive changes at home. Both developments made it possible for individual aristocrats to acquire disproportionate resources for competing with their peers. In eagerly seeking those resources in accordance with long-held values, Roman aristocrats raised their competition to levels destructive to the very Republic that they cherished.

Suggested reading

Goldsworthy , A. Antony and Cleopatra. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2010.

Osgood , J. Caesar’s Legacy: Civil War and the Emergence of the Roman Empire. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006.

Welch , K. Magnus Pius: Sextus Pompeius and the Transformation of the Roman Republic. Roman culture in an age of civil war. Swansea: Classical Press of Wales, 2012.