Chapter 18

The political turmoil that began with the Gracchi was matched by continued social, economic, and cultural ferment. In the countryside of Italy, the problems that had contributed to the Gracchan crisis were often made worse by the series of domestic wars inaugurated by the Social War in 90 b.c.e. The provinces suffered from the ravages of war, both civil and foreign, and from frequently inept or corrupt administration. In Rome and Italy, people’s values and behavior changed as the old social fabric frayed. The mos maiorum lost its strength, the state’s cults suffered neglect during civil upheavals, and new religious influences from the Hellenistic East gained in popularity. Nowhere, however, was change more evident than in art and literature. Creative, thoughtful individuals responded to the social, economic, and political turmoil with new attitudes, forms, and concepts that mark the late Republic as a period of great creativity as well as crisis.

Land, veterans, and rural life

Whatever success Gracchan land-redistribution legislation may have had in the late 100s b.c.e., the problems that it sought to alleviate in Italy were just as bad throughout much of the first century b.c.e. The forces that had impoverished many small farmers earlier still existed, and facts do not support the thesis that, beginning with Marius, powerful generals largely solved the problem by enrolling landless men in their armies and providing them with land upon discharge. That land was often taken from other smallholders. Those who received it frequently, in turn, lost it from a combination of economic, demographic, and political factors. Large-scale, long-term settlements in the provinces had to wait until after 30 b.c.e. when the civil wars of the Republic finally ceased.

Until then, instead of receiving their own land to farm, a number of landless or indebted peasants became free tenants, coloni, on great estates. This trend is evident primarily in central and southern Italy, where the great estates were concentrated and where the danger of rebellion among large concentrations of slaves had been emphasized by the revolt of Spartacus. Some owners, therefore, found it safer and more productive to settle coloni as cultivators on part of their land in return for a yearly rent.

Despite all the problems facing small farmers, many did survive. In the rural districts of interior Italy, small independent farmers still concentrated primarily on the cultivation of grain, whose surplus production could be sold in nearby towns. Near large towns and cities, specialized production for urban markets remained profitable. The great estates continued to specialize in raising sheep, cattle, and pigs to supply wool, hides, and meat for urban markets and Roman armies, or in the growing of grapes for wine and olives for oil.

Wealthy landowners also began to experiment with more exotic crops for either profit or ostentatious display on their own tables. Many large estates were turned into hunting preserves to supply their owners with choice wild game, and seaside properties became famous for their ponds of eels, mullet, and other marine delicacies.

In the western provinces, landowners in Sicily and North Africa intensified the production of grain for export to the insatiable Roman market. Italian immigrants in Spain and southern Gaul were establishing olive groves, vineyards, and orchards that would eventually capture the provincial markets of the exporters in Italy. The rural economy in the eastern provinces, however, was severely depressed as a result of the devastation, confiscations, and indemnities resulting from the Mithridatic wars and the civil wars of the 40s and 30s.

Industry and commerce

Manufacturing and trade in the East had also been severely disrupted by the wars of the late Republic. Many Italian merchants and moneylenders in Asia Minor lost their wealth and their lives in the uprising spurred by Mithridates in 88 b.c.e. Delos, which the Romans had made a free port to undercut Rhodes in 167/166, never recovered from being sacked in 88 and 69. When commerce did revive between the Levant and Italy, it was largely in the hands of Syrian and Alexandrian traders, who maintained sizable establishments at Puteoli to serve Rome and Italy. Italians, however, dominated the western trade, particularly the export of grain from Africa and Sicily and the exchange of Italian wine, pottery, and metalwork across the Alps in return for silver and slaves.

Two of Italy’s most important industries, the production of bronze goods and ceramic tableware, were concentrated respectively at Capua in Campania and Arretium in Etruria. Capua produced fine bronze cooking utensils, jugs, lamps, candelabra, and implements for the markets of Italy and northern Europe. Using molds, the Arretine potters specialized in the mass manufacture of red, highly glazed, embossed plates and bowls known as terra sigillata, or Samian ware. It enjoyed great popularity all over the western provinces, which eventually set up rival manufacturing centers of their own.

The copper mines of Etruria were becoming exhausted in terms of the prevailing techniques of exploitation, but the slack was more than taken up by production in Spain, where private contractors operated the mines on lease from the state. Tin, which was alloyed with copper to form bronze, was imported from Cornwall in the British Isles along a trade route that had been opened up by the father of Marcus Crassus during his governorship of Spain in 96 b.c.e.

Several factors limited economic growth: the low level of ancient technology in the production and transportation of goods, the extensive use of slave labor, and the extremely uneven distribution of wealth. They hampered development of large-scale industries and mass markets that would have provided high levels of steady, full-time employment for wage laborers. Rather, Rome and other large cities like Capua, Puteoli, and Brundisium were the domain of the taberna (home plus retail shop) or the officina (workshop) and small individual proprietors, both men and women (pp. 329–30). Helped by family members and a slave or two, the shopkeeper would carry on the retail sale of particular types of food, goods, or services or engage in the specialized production of goods on a handicraft basis. Goods might also be sold at retail on the premises or at wholesale in batches to a merchant who would consolidate them for bulk shipment elsewhere or peddle them individually in smaller towns that could not support a local retailer or producer.

Specific trades were often concentrated in certain streets or neighborhoods. At Rome, for example, there were the Street of the Sickle Makers and the Forum Vinarium, where the wine merchants gathered. In that way, it was easy for merchants and craftsmen to exchange information of mutual interest, receive materials, and be accessible to customers looking for what they sold or produced.

In Rome and Italy, the building trades flourished. Sulla, Pompey, and Caesar used the spoils of war to finance many public works in Rome. Wealthy nobles covered the Palatine with sumptuous townhouses. Elsewhere in the city, speculators put up huge blocks of flimsy, multistoried apartment buildings, insulae, to house a population probably nearing a million (if we include the outlying suburbs) by 30 b.c.e., despite attempts to reduce it.

FIGURE 18.1 Pompeii, the Street of Abundance, with workshops and stores.

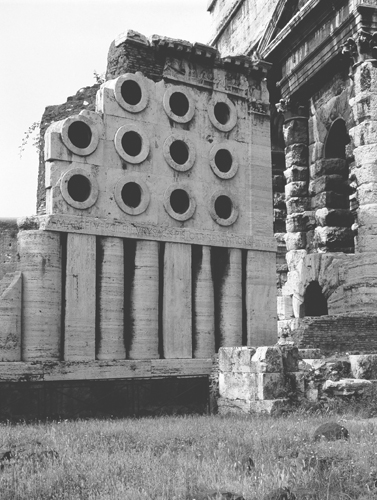

Some of the lower-class freedmen or freeborn tradespeople and craftworkers could acquire significant wealth and property. People who produced or sold luxury goods for the wealthy in their tabernae and officinae were very successful. Some owned several shops in their specialties around the city of Rome. People who dealt in gold and silver jewelry, pearls, precious stones, perfumes, luxury furniture, and artwork were quite prosperous. One large-scale baker named M. Vergilius Eurysaces was so successful that when he died, around 30 b.c.e., he left for himself and his wife, Atistia, one of the largest and most impressive funeral monuments still in existence from ancient Rome (see Figure 18.2). On it, the couple commemorated all aspects of commercial bread-making in a handsomely sculpted frieze. A freedman named Q. Caecilius Spendo, who specialized in making cheap clothes, built a tomb large enough to include eighteen of his own ex-slaves along with him and his wife.

Other than war, the business that still produced the biggest profits was finance, both public and private. The numerous annexations in Asia Minor greatly expanded the business of tax farming, which was carried on by companies of publicani (p. 186). Money lending was an important source of profits to wealthy financiers. Often, provincial cities needed to borrow money to pay the publicani, or client kings needed loans to stay solvent after paying huge sums to obtain Roman support for their thrones. With interest rates as high as 24 or 48 percent, even the greatest nobles were tempted to exploit this source of revenue. Pompey loaned some of the huge fortune that he had acquired in the East to Ariobarzanes II, whom he had confirmed as king of Cappadocia. In 52 b.c.e., Cicero was shocked to learn that Marcus Brutus was the Roman who indirectly pressured him to use his power as governor of Cilicia to force the Cypriot city of Salamis to make payment on an illegal loan at 48 percent interest.

FIGURE 18.2 The funeral monument of M. Vergilius Eurysaces, a wholesale miller and baker of late Republic or early Augustan times. The various operations of milling and baking are depicted in the bas-reliefs at the top.

On the other hand, there were many lenders, mostly well-to-do equites, who engaged in the more normal business of advancing money to merchants and shipowners to finance trade or to Roman aristocrats to finance their careers. One of these men was Cicero’s confidant, publisher, and banker, T. Pomponius Atticus. Although they were heavily engaged in business, they shared the basic outlook of the landed aristocracy and used much of their profits to invest in land and live like gentlemen. For example, vast estates acquired in Epirus allowed Atticus to spend the turbulent years from 88 to 65 at Athens (hence his cognomen, Atticus), where he was safe from Rome’s political storms. When he returned to Rome, he patronized the arts and literature from his house on the Quirinal. He made so many important contacts that he was protected on all sides during the subsequent civil wars.

The concentration of wealth

Atticus, with his great wealth, illustrates one of the striking features of the late Republic: the concentration of wealth in a few upper-class hands and the ever-widening gap between rich and poor. This trend had already been evident since at least the time of the Punic Wars. It was greatly accelerated by Marius’ and Sulla’s introduction of proscription. In times of civil war, those on the winning side, or at least not on the losing side, could acquire the property of proscribed individuals at a mere fraction of its normal value, either through favoritism or because the sudden increase in property for sale temporarily depressed prices. When property values rose with the return of normalcy, their net worth increased enormously. For example, Marcus Crassus had inherited a relatively modest fortune of 300 talents upon the deaths of his father and brother in the civil war of 87. After siding with Sulla in 83, however, he took advantage of Sulla’s proscriptions in order to acquire valuable properties. Then, through shrewd management, he increased his wealth still further, so that his vast real-estate holdings alone were worth more than 7000 talents in 55 b.c.e.

The profits of war and imperial administration that accrued to the nobility were even greater. Despite his failure to defeat Mithridates totally, Lucullus had amassed enough wealth from Asia Minor to live like a king in numerous villas after his recall to Italy. He became so famous for his conspicuous consumption that the term Lucullian has come to characterize rich living. The wealth acquired by Pompey and Caesar during their respective conquests in the East and Gaul made them far wealthier than even Crassus. His only hope of matching them was to conquer the wealthy empire of Parthia.

Provincial governors often abused their power in order to amass personal fortunes to compete with their aristocratic rivals for high office and social status. Verres, the notorious governor of Sicily from 73 to 71 (pp. 260–1), was reported to have said that the illegal gains of his first year were to pay off the debts that he had incurred in running for his praetorship of 74, those of the second year were to bribe the jury to acquit him of his crimes, and those of the third were for himself. Significantly, the artworks that he had plundered from Sicily were said to have earned him a place on Antonius’ proscription list in 43. Even an honest governor, such as Cicero had been in Cilicia in 52, was able to profit handsomely from office. In addition, though a man of relatively modest means among the Roman nobility, Cicero had prospered through inheritances, gifts, and favorable loans from other nobles whom he defended in court. He was able to buy a townhouse on the Palatine for 3.5 million sesterces and at least eight well-appointed country villas. He, too, of course, lost them along with his life in the proscriptions of 43.

Life for the urban poor

As an imperial city, Rome acquired a more and more diverse population through voluntary immigration and the importation of slaves from all over the Mediterranean world. Some ended up doing very well. Most joined the hundreds of thousands who toiled in anonymity. The luckier ones might have been able to afford to live in some of the better insulae that were being built with concrete, which had been introduced in the second century (p. 195). Still, even these insulae were often ill-lit, poorly ventilated, and unsanitary. In fact, overall health conditions in a large preindustrial city like Rome were such that it could not have expanded or even maintained the number of its inhabitants without a constant high level of immigration.

Although there were large numbers of artisans and shopkeepers, there were even more unskilled and semi-skilled people. They had to rely on occasional employment as day workers on construction projects, on the docks, and in odd jobs like porterage and message-carrying for the more fortunate. As clients of the rich, many of the poor were helped by gifts of food (sportulae) and occasional distributions of money (congiaria). Public festivals and triumphs could also produce helpful bonuses. Crassus, for example, feasted the whole city of Rome to celebrate his victory over Spartacus and gave each Roman citizen a three months’ supply of grain. The public distribution of free grain to several hundred thousand Roman citizens also helped to keep prices reasonable for those who had to buy all of their grain. Since it was limited to adult men, however, it was not enough to sustain their families. The distribution of free grain was not based on need. Grain went to all of those who met basic citizenship and residency requirements, even the rich. Many poor inhabitants of Rome and Italy received no free grain. For them, hunger must have been a constant threat.

Fire, flood, and violence

Life in the cities, particularly Rome, was precarious in other ways, too. There was no public fire department to control the numerous fires that swept through crowded slums. There was no systematic effort to prevent the Tiber from flooding the low-lying, usually poor neighborhoods. Nor was there a police force to prevent the crime and violence that poverty and crowded conditions bred. Private associations might try to provide local protection. Some wealthy individuals earned popularity by maintaining private fire brigades, as Crassus is believed to have done and as did a certain Egnatius Rufus later. The rich surrounded themselves with private bodyguards when they traversed the city, especially at night. The poor had to rely mainly on their own efforts or those of family and friends to protect themselves or secure justice from those who committed crimes against them. The principle of self-help was still widely applied. There was no public prosecutor, and the courts, with their cumbersome procedures, were mainly for the rich (pp. 204–5).

Politically inspired violence also increased greatly in late republican Rome. The most notable examples, of course, are the civil wars and proscriptions, during which many thousands were killed. Increasingly, however, important trials, political meetings (contiones), elections, and legislative meetings of the assemblies were marred by violence. Rival politicians hired gangs to intimidate and harass each other (p. 280).

Public entertainments

As a result of elite political competition and the availability of greater resources, public entertainments at Rome became more numerous, more elaborate, and more violent during the late Republic. These entertainments were associated with various public religious festivals of the Roman year (pp. 66–7), special celebrations, and funerals. During the Republic, the aediles became responsible for presenting games, ludi, at major public festivals. There were two types: ludi scaenici, which involved the presentations of plays and pantomime dances accompanied by flutes, and ludi circenses, which consisted of chariot races in a circus built for that purpose. The aediles received some public funds but increasingly sought popularity for election to higher office by lavish additional expenditures of their own. They even provided such extras as exotic-beast hunts (venationes) and gladiatorial combats, which wealthy families often put on at the funerals of prominent members.

Supplying wild beasts and gladiators for entertainments at Rome required big operations. The hunting, trapping, shipping, and handling of wild beasts involved complicated networks of suppliers and agents. Enterprising men set up training schools, like the one from which Spartacus escaped (pp. 258–9), to turn promising slaves and volunteers into professional fighters whom they provided on contract for gladiatorial shows. Gladiators fought according to strict regulations regarding equipment and rules of combat. Contrary to modern belief, they did not usually fight to the death unless the sponsor was willing to pay a hefty premium for the privilege of wasting what were valuable professional athletes. Like modern athletes, they developed followings of loyal fans who often showered them with money that allowed them eventually to buy their freedom and retire as wealthy men if they lived long enough.

The same was true of the charioteers who raced in the ludi circenses. There were usually four competing in each race. In the late Republic, the people in charge of the games would hire the charioteers, the horses, and the chariots from four different groups organized for that purpose. The groups came to be known as factions (Latin, factiones), and each one distinguished itself by a special color—red, white, blue, or green. In a society where the urban poor often led idle and frustrating lives, the circus races aroused intense interest. Daredevil driving and deaths in spectacular crashes rivaled modern automobile races, and there was always the chance to make a little money by betting on the winner. The restless and bored attached themselves to individual factions, wearing their faction’s distinctive color, cheered their favorites, and sometimes fought with each other in brawls.

Voluntary associations

To obtain some measure of protection and comfort in the violent, disease-ridden, and unpredictable world of the tabernae and insulae, the lower classes of Rome and other cities organized themselves into voluntary associations, collegia (briefly outlawed from 64 to 58 b.c.e. [p. 280]). People organized collegia based on their occupations, religious cults, or local neighborhoods (vici), districts (pagi), or hills (montes). They elected their own officers and pooled their modest resources to provide banquets and entertainments for themselves, ensure proper burial when they died, and protect their interests against the higher authorities if need be. Indeed, aristocrats campaigning for office courted their votes and hoped that the collegia would promote their campaigns.

Slaves and freedmen

The kidnapping activities of pirates before 67 b.c.e., Pompey’s conquests in the East, and Caesar’s conquests in Gaul produced a continual flood of slaves. Overall, the lives of slaves did not change much over the course of the Republic. Roman masters, however, did learn from the dreadful uprisings of mistreated rural slaves in Sicily (104–99 b.c.e.) and under Spartacus in Italy (73–71 b.c.e.). Therefore, they improved the treatment or control of such slaves enough to prevent future outbreaks. Roman masters did sometimes free personal and domestic slaves, whom they frequently came to know and view as members of their own families, personal friends, and bedmates. A good example was Cicero’s personal secretary Tiro. Tiro served Cicero faithfully as a freedman, invented a system of shorthand (still extant) to handle his voluminous dictation, wrote a biography of him after his death, and helped to collect his correspondence for publication.

FIGURE 18.3 The funerary monument of the freedman A. Clodius Metrodorus, a doctor (medicus), flanked on the left by his son, Clodius Tertius (also a doctor), and on the right by his daughter, Clodia.

Many freedmen became successful and even wealthy in business. They often got their start with financial help from their former masters, with whom they shared their profits. Ironically, freedmen had larger profits to share after 118 b.c.e., when a law removed many other obligations that freedmen once owed their former masters. Nevertheless, many freeborn, upper-class Romans became very ambivalent toward freedmen. On the one hand, they enjoyed the profitable business associations with successful freedmen; on the other hand, they saw the success of freedmen as threats to their own social status. One result was the extremely negative upper-class stereotype of the boorish nouveau-riche freedman later epitomized by the character Trimalchio in Petronius’ Satyricon (p. 479). Even lower-class freeborn citizens jealously guarded their privileges. Efforts to give freedmen membership in all the voting tribes were bitterly resisted and always failed.

Italians and provincials

Unlike freedmen, the Italians, who had won the franchise as a result of the Social War, were able eventually to obtain equitable enrollment in the voting tribes (pp. 259–60). Still, for the average Italian, the difficulty of going to Rome to exercise the franchise regularly made the vote of little worth. For the local Italian landed aristocracy, who now became Roman equites, it was another matter, however. They joined the older equites in demanding a greater voice in public affairs. Sulla’s addition of 300 equites to the senate did not appreciably alter the status of the rest. They continued to feel that the noble-dominated senate was not doing enough to protect their legal and financial interests. Men like Cicero (who came from the equestrian class), Pompey, Crassus, and Caesar, however, eagerly supported many equestrians. Their money, votes, and influence could be highly useful in the struggles of the Forum. Similarly, powerful Roman aristocrats courted wealthy provincials, provincial cities, and even entire provinces as clients. Their money, manpower, and material resources were great advantages in domestic struggles and foreign wars.

Women in the late Republic

Upper-class women played a significant role in the intellectual and political life of the late Republic. To be sure, fathers did not send their daughters away to places like Athens or Rhodes for higher training as they did their sons (p. 331). Nevertheless, some accomplished and loving fathers, like Hortensius, Cicero, and the younger Cato, took great personal interest in educating their daughters beyond the ordinary level. Cicero lavished much attention on his daughter Tullia. While he was in exile, he became extremely distressed that her mother, Terentia, had arranged a marriage for her with a man whom he correctly thought was unworthy of her virtue and intelligence. Cicero was inconsolable over her death and even contemplated the establishment of a cult and shrine for her. Cato’s daughter, Porcia, was like her father with respect to his outspoken republicanism. She supported her first husband, M. Calpurnius Bibulus, in his opposition to Caesar. She insisted that she participate with her second husband, Brutus, in the planning of Caesar’s assassination. After her death, Cicero delivered a powerful eulogy for her.

FIGURE 18.4 Woman with a stylus and wax writing tablet; wall painting from Pompeii, 40–50 c.e.

In 42 b.c.e., Hortensia, the daughter of Cicero’s oratorical rival Hortensius, appeared with a female delegation in the Forum to argue against the imposition of a special tax on wealthy women to pay for the war against Brutus and Cassius (see Box 18.1). She gained public support and won her point. Pompey’s last and most beloved wife, Cornelia, daughter of Metellus Scipio, earned praise because she was well read, could play the lyre, and, most significantly, was adept at geometry and philosophy. Nor can anyone ever forget Sallust’s picture of the high-born, highly educated, and daring Sempronia, a conspirator with Catiline in 63 b.c.e. (Bellum Catilinae, 25) and possibly the mother of Caesar’s assassin Decimus Brutus.

18.1 Female networks

The episode of the confrontation over the triumvirs’ proposed tax on the estates of wealthy women demonstrates that Roman women had their own social networks that ran alongside, and sometimes intersected with, the networks of which their husbands, sons, and fathers were part. This was not something new in the late 40s b.c.e.; rather, it is a phenomenon of which we can catch a glimpse every now and then in the literary sources going at least as far back as the late third century.

In 42 b.c.e., after organizing themselves as a group, the women first made their case to the closest female relatives of the men in charge: Fulvia, the wife of Antonius; Julia, his mother; and Octavia, the sister of Octavian. This was, clearly, proper protocol for voicing their opposition. Hortensia and her colleagues were well received by Julia and Octavia; Fulvia, demonstrating a striking independence from social pressure, rejected their overtures. Her rudeness, so the story goes, inflamed the other women so that, in the heat of the moment, they headed en masse to the Forum where they confronted the triumvirs. Antonius, Octavian, and Lepidus, affronted by the women’s brazenness, ordered them removed from the forum. Hortensia’s speech, however, had persuaded the crowd standing around the tribunal, so the people rushed to the women’s defense. Ultimately, the women won a partial victory: the triumvirs did not cancel the tax, but they did restrict it to only the 400 wealthiest women in the city rather than the original 1400 who had been targeted.

Pompey’s third wife, Mucia, also deserves mention. She did not disappear from public life after Pompey divorced her. She quickly married M. Aemilius Scaurus, Pompey’s former quaestor and brother of Aemilia, Pompey’s deceased second wife. Mucia thus remained connected to the world of elite politics. She actively promoted the fortunes of her three children by Pompey and the son whom she bore to Scaurus. She played a key role in arranging the negotiations for the Treaty of Misenum (p. 308). After the Battle of Actium, she secured a pardon for her son by Scaurus.

Terentia, Cicero’s first wife, also should not be overlooked. She was a resourceful and influential person in her own right. She is said to have had a significant role in the bitter relations that Cicero had with Catiline and Clodius. While Cicero was in exile or abroad during his governorship or civil war, she handled his complicated finances, oversaw his various villas, managed her own considerable properties, protected his children, and promoted his cause even if she did not always win his approval. After their divorce, she continued to manage her investments and received at least one significant legacy from a wealthy banker. Although she did not have Cicero’s depth of intellectual interests, she appreciated her learned slave Diocles enough to free him. He had been trained by Tyrannio of Amisus, who edited the rediscovered manuscripts of Aristotle (p. 330). As a freedman, Diocles established a school and probably shared its income with Terentia. St. Jerome’s statement that Terentia later married the historian Sallust has been rightly challenged: his source probably meant that Sallust had married Cicero’s much younger second wife, Publilia. Terentia, whom Cicero had divorced in 46 b.c.e., lived a very long life, dying only at age 103 (ca. 6 c.e.).

The need for powerful marriage alliances in the growing competition for power among the aristocracy of the rapidly expanding Roman Republic gave numerous upper-class Roman women opportunities to influence public affairs. As members of powerful aristocratic families, many of them pursued family or personal agendas and were willing to use marriages and sexual liaisons to advance them. Prime examples include Cornelia, Pompeia, and Calpurnia, Caesar’s wives; Fulvia, wife of Clodius, Curio, and Marcus Antonius; Servilia, mistress of Julius Caesar and mother of Marcus Brutus; Octavia, wife of C. Claudius Marcellus and Marcus Antonius and sister of Octavian; Scribonia, Octavian’s second wife; and Livia, Octavian’s last wife.

The frequent charges of sexual misconduct are one of the most visible signs of the increased power and independence of upper-class women in the late Republic. While some woman like Cornelia, mother of the Gracchi, though quite independent, had held to the ideal of a virtuous Roman matron and widow, others became the target of gossip and scandal. Pompey divorced Mucia because she was alleged to have been unfaithful while he was fighting Mithridates. Caesar’s second wife, Pompeia, was caught in the famous affair with P. Clodius (pp. 270–1). One of Clodius’ three sisters (each named Clodia), the wife of Metellus Celer, was reputed to have been highly promiscuous. Among her lovers, many believe, were the poet Catullus and Cicero’s friend M. Caelius Rufus (p. 281). Another of the sisters, Lucullus’ ex-wife, was accused in sworn testimony of having had incestuous relations with Clodius while she was still married to Lucullus. Sallust claims that a number of talented and dissolute women besides Sempronia became involved in Catiline’s conspiracy. The independent, intelligent, and unconventional aristocratic women of the late Republic have their counterparts in many of the women in later Imperial dynasties. Clearly, they also generated politically motivated invective regarding their characters as did powerful men.

Women of the lower classes

There were three major categories of lower-class Roman women: slaves, freedwomen, and poor freeborn women. Female slaves continued to make up a large percentage of the household workforce in such capacities as nurses, weavers, hairdressers, handmaidens, cooks, and housekeepers. The more there were and the more specialized their tasks, the greater their owner’s prestige. Large numbers of female household slaves eventually gained freedom. Some stayed on as free retainers with their former owners, others practiced the trades that they had learned as slaves, and some rose to a comfortable status by good marriages, generous patrons, or hard work.

The most unfortunate group of female slaves was that of the prostitutes. Prostitution was extensive, and often the unwanted female children of slaves and poor citizens were sold by masters and parents to procurers who raised them for that purpose alone. In general, they had little to look forward to. Even if they obtained their freedom, they were not trained to do anything else and could have become worse off without an owner who had an interest in providing a minimum level of shelter, food, and physical security.

Ironically, the slaves and freedwomen of the aristocracy often had far greater opportunities in life than freeborn women of the poorer citizen classes. Girls were less valued than boys. With the added burden of a high incidence of death in childbirth, life for poor women was precarious indeed. They often worked the lowliest jobs: laundry work, spinning and weaving, turning grindstones at flour mills, working as butchers, and selling fish are frequently recorded. Inscriptions from Pompeii list some other occupations for women, such as dealer in beans, seller of nails, brickmaker, and even stonecutter. Many women worked as waitresses in taverns or servers at food counters, where they may also have engaged in prostitution on the side. The names of waitresses and prostitutes are found scribbled on numerous tavern walls, with references to their various virtues or vices, attractions or detractions as the case may be. For many unskilled poor women, prostitution was the only source of livelihood, and unlike slave prostitutes, who had at least the protection of a brothel, they had to practice their trade unprotected out of doors in the public archways, fornices, whence comes the word fornicate.

New waves of Hellenization

The First and Third Mithridatic wars sent two new surges of Hellenization over Roman arts and letters. In 88, Philo of Larissa, head of Plato’s Academy in Athens, fled to Rome. He became the teacher of important political and intellectual leaders like Quintus Catulus and Cicero. When Sulla looted Athens in 86, he sent home fleets of ships loaded with the finest products of Greek artists, writers, and thinkers. Among them were the works of Aristotle and his successor as head of the Lyceum. These works had been damaged earlier and had not been widely known for some time. Their intellectual impact was extensive, particularly after Lucullus brought back the captive Greek scholar Tyrannio of Amisus during the Third Mithridatic War, who helped to amend and publish them.

At the end of the third war, Pompey brought back the Greek historian Theophanes of Mytilene and the medical library of Mithridates. Lucullus had already looted a large library of books from Pontus, which he housed in a complex of study rooms and colonnades where Greek intellectuals and interested Roman aristocrats met to study and debate. Indeed, Lucullus set the fashion for large private libraries such as Cicero created. Caesar had planned to outdo them all by building Rome’s first public library and filling it with books from the famous library of the Ptolemies at Alexandria. This Roman mania for Greek libraries stimulated a tremendous demand for the copying and selling of books, which made Greek culture even more accessible to the Romans.

Education

By the first century b.c.e., Rome had developed a fairly extensive system of education. Its availability was limited by the ability to pay, since the state contributed no support. Primary schools (ludi literarii) were open to both boys and girls. There they learned the fundamentals of reading, writing, and arithmetic, often painfully, since corporal punishment was frequently applied. Between the ages of twelve and fifteen, girls and boys took different paths. A girl would often be married to an older man at about fourteen, and if she were not of the wealthy elite, formal education stopped. Roman boys moved on to the secondary level under the tutelage of a grammaticus, who taught them Greek and Latin language and literature. No Roman of the first century b.c.e. could be considered truly educated if he did not speak and write Greek as fluently as Latin and did not know the Classical Greek authors by heart.

Since the Romans had come to dominate Italy and the western Mediterranean by the first century b.c.e., it was essential for other people to know Latin. Therefore, schools of Latin, and even Greek for those who had real ambitions, were becoming common everywhere. They spread the Latin language and Greco-Roman culture widely and produced a remarkably uniform culture among the upper classes of Italy and the western provinces. As earlier, the masters of the primary and secondary schools were frequently freed slaves, like Terentia’s Diocles, who had been tutors in the houses of the wealthy. Their pupils were often offspring of equestrian or prosperous lower-ranking fathers like those of Cicero, Vergil, and Horace, who had ambitions for their sons to enter Roman politics and rise in social standing.

The prevalence of private tutors among the aristocracy meant that aristocratic girls often received instruction at the secondary level along with their brothers. Sometimes they were even able to participate in the higher training of rhetoric and philosophy, if, as with Sempronia, sister of the Gracchi, their families brought men accomplished in these fields into their homes and supported them in return for instructing their children. Many sons of both aristocrats and nonaristocrats were sent to professional rhetoricians for instruction at the highest level. Frequently an upper-class young man capped his formal education with a tour to the great centers of Greek rhetoric and philosophy at Athens and Rhodes.

For a long time, Greek rhetoric dominated the higher curriculum. Right at the beginning of the first century, there was a movement to create a parallel course of professional instruction in Latin rhetoric. In 92, however, the censors banned teachers of Latin rhetoric, perhaps out of fear that rhetorical skills, the foundation of political success, might be made too accessible to the lower orders. Julius Caesar finally lifted the ban when he became dictator.

Law and the legal system

Roman law continued to be shaped by private unpaid, learned, aristocratic jurists, the jurisconsults (pp. 203–4), but their role became less visible than it had been in earlier centuries. One reason was the establishment of the various permanent jury courts (quaestiones) under Sulla (p. 249). The praetors, by exercising their imperium as magistrates in charge of the courts, created law through their edicts granting relief to plaintiffs, issuing injunctions, and establishing procedural rules. As could anyone else involved in legal proceedings, praetors often consulted with the jurists before issuing their edicts. Praetors from one year tended to adopt the edicts of their predecessors. Over time, there grew up a body of praetorian law that supplemented the traditional civil law and specific statutes.

One of the major trends in the late Republic was a striving for fairness and equity, not just the strict application of the letter of the law. The jurists often resorted to the principle of good faith (bona fides) as a way of advancing equity. For the most part, this effort was a practical response to the increasing complexity of the Roman world rather than the mere borrowing of a concept from Greek law or philosophy, as has sometimes been argued. Nevertheless, as in the case of the Gracchan reforms, Greek law and philosophy may have helped to provide Roman jurists with a vocabulary and rationale for what they were doing or had done.

The same is true in the development of the famous ius gentium (law of nations) in the late Republic. Roman civil law and statutes did not always apply in cases where non-Romans were involved. That was increasingly the case with the expansion of Roman power. Therefore, the praetor peregrinus at Rome and the governors of provinces often incorporated into their edicts useful elements from the laws of other people. Greek philosophical concepts like the Stoic idea of a natural law (ius naturale) uniting all people supplied useful jargon and justification for what the Romans were doing, but they do not seem to have supplied any ideological motivation.

On the other hand, the principles of logic, debate, and rhetoric worked out earlier by Greeks were important for the rise of professional forensic orators. They began to take over from traditional jurisconsults in pleading cases before standing courts of nonspecialist judges and jurors. Orators, however, still relied on the expertise of learned jurists like two cousins from the Scaevola family. The older was Quintus Mucius Scaevola the Augur, consul in 117 b.c.e. He was the son-in-law of Scipio Aemilianus’ famous friend Laelius. He was also the father-in-law of his own protégé L. Licinius Crassus. As a pupil of both Scaevola the Augur and L. Crassus, Cicero absorbed their idealism and moderation. The younger of the two Scaevolae was Quintus Mucius Scaevola the Pontiff, consul in 95 b.c.e. The greatest of all legal works published during the Republic was his Civil Law (Ius Civile), the first systematic exposition of private law and a model for legal commentators down into the second century c.e.

The religious world of the late Republic

Religious life continued to be vibrant and varied throughout the late Republic. The cults and festivals of rural villagers and urban members of countless collegia and neighborhood associations continued to flourish. Worshipers frequented temples, leaving gifts for the gods alongside their prayers. The frequency with which augury, divination, and the reporting of omens were used by political rivals against each other shows just how seriously those things were taken. Indeed, the more one thought that he was on the side of the gods, the more convinced he would have been of finding favorable auguries, signs, and omens. Of course, an enemy, who often is equally convinced of his own rightness, will naturally claim that his opponent is a liar and a fraud.

If the state for which the great deities were chiefly responsible was not faring well and public cults were being neglected during destructive civil wars, it was not seen as a failure of religion. It was a failure of the leaders. They were always equally responsible for running the state and carrying out the religious duties that maintained the pax deorum (peace of the gods) vital to its welfare. That Julius Caesar had won the civil war with Pompey and was restoring peace and stability was proof to many of his divine favor and justified bestowing on him such honors as made him seem more than human.

In a manner, going all the way back to Hercules in the Forum Boarium (p. 206), Julius Caesar became just another in a long line of new deities whom the Roman state had officially welcomed into the Roman family of gods over the centuries. It was always wise to have as many gods as possible participate in the pax deorum that protected the state and fostered the growth of Roman power. As Rome had incorporated new people into the ranks of its Italian allies and overseas empire, so it had incorporated their gods. In times of crisis, the senate was even known to have sanctioned the adoption of a completely foreign deity, as was the case with the Great Mother (Magna Mater), Cybele, from Asia Minor during the Hannibalic War in 204 (p. 187).

Nevertheless, Roman authorities were leery of cultic practices and deities that seemed too un-Roman or appeared to promote political loyalties other than to Rome. The senate may have viewed Jewish immigrants, adherents of the Temple and high priest at Jerusalem, as being just like the Bacchic worshipers whom it suppressed in 186 (p. 205). However that may be, a senatorial decree of 139 ordered the expulsion of Jewish immigrants from Rome. Only after Pompey captured Jerusalem and established Roman hegemony in Judea during the Third Mithridatic War were the captives whom he brought back to Rome successful in establishing permanent synagogues there. Chaldean astrologers were particularly suspect because of the secret knowledge that they claimed to have and that might be used against established authority. Therefore, a law, probably of 67 b.c.e., expelled them, too. Similarly, when Roman relations with Cleopatra’s Egypt were tense in the 50s and 40s, there were several attempts to destroy the increasingly popular worship of the paired Egyptian deities Isis and her consort, Serapis (Sarapis). The priests of Isis and Serapis were independent of the official Roman priesthoods. They fostered a personal attachment to the loving goddess Isis and her consort, who were closely associated with the Ptolemaic dynasty. Originally, she had been an ancient Egyptian nature goddess, but in Ptolemaic times she was transformed into a universal mother figure and savior of mankind.

The growth of Hellenized mystery cults like those of Isis and, later, Mithras (pp. 491–2) shows the spread of new religious forces in the Roman world, particularly in the large multiethnic, polyglot populations of cities like Rome. Traditional Roman religion still had great meaning for the Roman elite, who controlled it, and the native-born citizens, whom it served. Yet large numbers of willing and unwilling immigrants (slaves) from the eastern Mediterranean made up an increasingly large percentage of the urban population. They often found greater comfort in the mystery cults of their homelands. The conditions that had made them popular there were now being replicated in Rome and other large western cities. People who had been uprooted from the close-knit world of family, village, and local cults lived in a vast, dangerous, and unpredictable urban world made even more dangerous and unpredictable by partisan conflict and civil war. Sharing the mysteries of an initiation rite helped individuals stripped of previous associations create a new sense of community and belonging to one another. Moreover, deities like Isis, Mithras, and Cybele promised not only salvation in the next life, but also nurture and protection in this one through a personal connection with a powerful universal deity who was not limited to one city or territory. Such religions would find greater and greater appeal in the increasingly urbanized and cosmopolitan Roman world of the next two centuries.

Greek philosophy and the Roman elite

The removal of Greek philosophers and whole libraries of Greek philosophical writings to Rome and Italy during the first century b.c.e. stimulated the study of philosophy on a scale never seen before among the educated elite. There are those who say that this increased exposure to the rationalism of Greek philosophy undermined the ruling class’ belief in traditional Roman religion. That was true, no doubt, in some individual instances. Many probably had no difficulty in separating their religion and its important public role from their private intellectual pursuits as gentlemen. After all, many highly trained physicists and biologists today practice religions whose literal scriptures are at variance with many of their scientific suppositions. Cicero, for example, who subjected major aspects of Roman religion to intellectual scrutiny in such works as On the Nature of the Gods and On Divination, was in no way willing to discard them, even if he did not accept them in every single particular. So, for example, in the dialogue On the Nature of the Gods, one of his speakers says that he still believes in the traditional religion even though he cannot find proofs that meet his standards as an adherent of the Academic school of philosophy.

Stoicism

Stoic philosophy had been modified in the late second and early first centuries b.c.e. by the pro-Roman Panaetius of Rhodes (p. 203) and Posidonius of Apamea. Their views appealed to Romans like Cato the Younger and Brutus, who saw support for traditional Roman morality in Stoic ethics. Panaetius emphasized the virtues characteristically ascribed to a Roman noble: magnanimity, benevolence, generosity, and public service. In 87 b.c.e., as a Rhodian ambassador to Rome, Posidonius had developed a dislike of Marius. Therefore, in his historical writings, he favored Marius’ optimate enemies and their outlook, which further endeared his Stoic teachings to men like the younger Cato. Cicero and Pompey had both sat at his feet in Rhodes. Posidonius was so impressed with Pompey that he appended a favorable account of Pompey’s wars to the fifty-two books of his continuation of Polybius.

Posidonius saw Rome’s empire as the earthly reflection of the divine commonwealth of the supreme deity. Its mission was to bring civilization to less advanced people. Statesmen who served this earthly commonwealth nobly would join philosophers in the heavenly commonwealth after death. Cicero adopted that idea in his Republic to inspire Roman nobles to lives of unselfish political service. Posidonius also believed that the human soul was of the same substance as the heavenly bodies, to which it returned after death. His scientific demonstration of the effect of the moon on earthly tides reinforced this idea and gave great impetus to astrology at Rome. The growing popularity of these ideas, therefore, made it less difficult to accept the notion that the comet seen soon after Caesar’s death was his soul ascending to heaven.

Epicureanism

Not everyone at Rome was a Stoic in the late Republic. A number of prominent Romans, including both Caesar and his assassin, Cassius, adopted the skeptical, materialistic, and very un-Roman philosophy of Epicurus. He had argued that such gods as there were lived beyond this world and took no part in it: the gods were not concerned about whether humans worshiped them or not, nor were they interested in how humans lived their lives. Epicurus believed that the soul is made up entirely of atoms that disperse among the other atoms of the universe upon death. Therefore, he stressed that death is not to be feared because there is no afterlife of eternal punishment, and he advocated that people should shun the cares of marriage, parenthood, and politics to live quietly in enjoyment of life’s true pleasures. Among the Romans, Epicureanism was popularized by Philodemus of Gadara. He came to Italy after the First Mithridatic War. Later, he lived at Herculaneum on the Bay of Naples near his patron L. Calpurnius Piso Caesoninus, Caesar’s father-in-law. Charred papyrus rolls containing some of Philodemus’ writings have been found in the remains of Piso’s villa. It was destroyed 150 years later by the famous eruption of Vesuvius and has now been spectacularly replicated to house the J. Paul Getty Museum in Malibu, California.

Roman Epicureans were less restrained in taking their pleasures than Epicurus himself would have approved; yet the Epicurean ideal of a life of pleasant retirement in one’s garden may help to explain why Sulla retired at the height of his power and why Lucullus, Caesar, and others lavished so much attention on their pleasure gardens.

The Peripatetics and the New Academy

The Aristotelian Peripatetic School and the New Academy of the Skeptic Carneades (pp. 203–4) were much less popular than other philosophical schools at Rome. Crassus, however, maintained the Peripatetic Alexander in his household. Cicero was greatly drawn to the Academic school, with its emphasis on the testing of ideas through rational inquiry and debate. Still, in general, Cicero was eclectic. He greatly favored Stoic ethics and attitudes but reveals Academic and Peripatetic influences, especially in his political thought (p. 339). Rather than creating new systems of philosophy, Cicero and other Roman philosophical writers adapted to the Roman context the ideas that they admired and found useful in the works of Greek thinkers.

Art and architecture

Romans continued to admire Greek art. They created a large market for standardized reproductions of famous Greek bronze statues in marble and of famous Greek paintings in frescoes and mosaics on the walls and floors of affluent homes. Still, native Roman and Italic traditions in realistic portraiture and landscape scenes flourished and became more sophisticated in technique.

In architecture, Romans adopted the Hellenistic Greek articulation of different architectural elements into a symmetrical whole along a central axis. The best example in Italy is the Sanctuary of Fortuna Primigenia at Praeneste (see Figure 18.2), which Sulla reconstructed. Sulla’s Tabularium (Record Office), carefully sited on the brow of the Capitoline just behind the Roman Forum and finished by Catulus in 78 b.c.e., gave a central backdrop to the Forum. Its colonnaded upper story provided a clear architectural link between the buildings of the Forum and those on the Capitoline to create an articulated whole (see the plan of Rome on p. 390). Rome’s first permanent theater, built by Pompey in 55 b.c.e., was another carefully articulated stone complex. Unlike Greek theaters, which were built into solid hillsides, Pompey’s was a freestanding semicircle with the stage and backdrop on the chord and the seats rising in tiers on the arc. A shrine to Venus Victrix stood on the center of the topmost tier. A colonnaded portico attached to the back wall of the stage provided shelter in case of rain and had an annex for meetings of the senate.

Caesar himself planned the Basilica Julia, across from the recently rebuilt Basilica Aemilia, to give greater definition to the Forum. In 46 b.c.e., Caesar built an entirely new and symmetrical forum known as the Forum Julium. It was a rectangle completely surrounded by a colonnade. Along the central longitudinal axis from back to front were a temple of Venus Genetrix, an equestrian statue of Caesar, and a fountain. This forum set the pattern for all subsequent fora built by the Roman emperors.

The Romans creatively began to combine different architectural elements and materials. They framed arched openings with half columns derived from the three traditional Greek orders—Doric, Ionic, and Corinthian as on the facades of the Sanctuary of Fortuna and Pompey’s theater. Using arches and vaults made of brick and concrete allowed the Romans to build more complex and massive buildings than did the Greeks. The Romans made these buildings look more expensive by covering them with thin veneers of stone or with stucco painted to imitate stone.

Late republican literature from the Gracchi to Sulla

Many major works of Roman oratory, poetry, history, and philosophy appeared in the century from the Gracchi (133 b.c.e.) to the Battle of Actium (31 b.c.e.). Unfortunately, almost nothing from the first half of the century has survived. The only extant book from before the death of Sulla (78 b.c.e.) is an anonymous Latin textbook on oratory, the Rhetorica ad Herennium (The Art of Rhetoric Addressed to Herennius), which shows marked Gracchan and Marian sympathies.

FIGURE 18.5 Remains of the Sanctuary of Fortuna Primigenia at Praeneste. The careful symmetrical arrangement of different shapes and architectural elements along a central axis extending from the bottom to the top can still be discerned.

Orators and historical writers

The two most notable orators in the early first century b.c.e. were Marcus Antonius, grandfather of the triumvir with the same name, and Lucius Licinius Crassus, one of Cicero’s teachers and a relative of Marcus Crassus. Once friends of Marius, both Antonius and Crassus joined the optimate opposition and perished during Marius’ proscriptions in 87 b.c.e. Gaius Gracchus and P. Sulpicius, the famous popular tribune of 88, were early practitioners of the Asianic style of oratory that is said to have originated in Pergamum. It was a highly emotional style of oratory, which used histrionic gestures, florid verbosity, and musical cadences to overpower the audience’s senses. The consummate practitioner was Cicero’s older rival, Q. Hortensius. In reaction to Asianism, there arose the Atticist school. It valued a plain, direct, simple style like that of the famous Attic Greek orator Lysias.

From the second century onward, the writers of history followed the lead of Cato the Elder and wrote in Latin. They were more interested in presenting their views on important topics to fellow Romans than to Greeks. Many still took the annalistic approach, some from a pro-Gracchan, popularis perspective and others from an anti-Gracchan, optimate stance.

Closely related to oratory and history was the emergence of aristocratic autobiography and antiquarianism. In the partisan atmosphere after the Gracchi, important men wanted to condemn their enemies and cement their own place in history by writing commentaries (commentarii). The two rivals M. Aemilius Scaurus and P. Rutilius Rufus mutually recriminated each other. Marius’ rivals Q. Lutatius Catulus and Sulla (using Greek) wrote accounts of their lives that reflected well on them and poorly on Marius. Marius’ reputation in later centuries has suffered in part because he never wrote his own account of his accomplishments. Antiquarian scholarship (research into the origins of old institutions, customs, and traditions) was stimulated by patriotic pride in competition with the Greeks and by partisan politics as the proponents of different policies and practices sought precedents in the past.

Drama and poetry

By the end of the second century b.c.e., plays of tragedy and comedy that had already become classics (pp. 197–200) increasingly competed with other dramatic forms, including native Italic traditions of slapstick, farce, and mime. By Caesar’s time, mimes dominated popular comedy. Their actors, male and female, appeared without masks and in plain shoes, did comic skits from daily life, sang and danced, and even put on stripteases. The skits might parody something from the high culture in the language of the street and include domestic quarrels or risqué love scenes without any sophisticated plot or point.

The Novi Poetae

Among the wealthy, cosmopolitan young aristocrats of the post-Sullan period were a number of poets who have come to be known as the Novi Poetae (New Poets) or Neoteric Poets from some references in the letters of Cicero, who disapproved of some aspects of their work but whose own poetry (which exists today only in fragment, see below) shares some important characteristics with it. They modeled their works on the personal and emotional writings of the early Greek lyric and elegiac poets like Sappho and Alcaeus or later Alexandrian love poets like Asclepiades. They also delighted in the learned, obscure, and exotic allusions to mythology, literature, and geography that characterized Alexandrian poets like Callimachus. They did not write for a large public but for themselves. That is why the works of all but one of them (including the epigrams of Cornificia, the only woman associated with them) have perished except for a choice line or two quoted by some grammarian or commentator on another work.

Catullus (ca. 85 to ca. 54 b.c.e.)

The one New Poet whose work has survived, albeit in a single manuscript from his hometown, is Gaius Valerius Catullus of Verona. Little is known of his life. He was born about 85 and died around 54 b.c.e. He moved in the highest circles of the aristocracy. His participation in public life was limited to a year of service in 57 on the staff of Gaius Memmius, governor of Bithynia, and to some scurrilous poems about politically prominent people, particularly Caesar, with whom he was reconciled shortly before he died.

At some point, Catullus met a woman with whom he had a torrid love affair. He called her Lesbia. Many believe that she was really Clodia, one of the sisters of the notorious P. Clodius and wife of Metellus Celer, but her identity is in no way certain. Apparently, “Lesbia’s” beauty and charm were equaled only by her promiscuity, as Catullus discovered to his bitter sorrow, which he expressed in a number of poems. He also expressed many other moods and emotions, such as grief in a touching lament for his dead brother, lightheartedness in a drinking song, reverence in a hymn to Diana, and ecstatic frenzy in a long poem on the god Attis. In all of his poems, Catullus shows himself to be a serious craftsman by being the first to adapt many Greek lyric meters to Latin poetry.

Lucretius (ca. 94 to ca. 55 b.c.e.)

One of the contemporary poets who did not share the outlook and focus of Catullus and other Novi Poetae was the Epicurean Titus Lucretius Carus. Even less is known about Lucretius than about Catullus. He was born about 94 and died probably in 55 b.c.e. His patron was Gaius Memmius, the same man whom Catullus served in Bithynia. A house excavated at Pompeii indicates that Lucretius’ family may have lived in the area around the Bay of Naples, where Philodemus and other Epicurean philosophers were concentrated.

Lucretius’ only known work, the De Rerum Natura (On the Nature of Things), is a didactic epic in six books of dactylic hexameter verse on Epicurean philosophy (p. 335). It is remarkable for the extraordinary beauty of the images it evokes, the elegance of its Latin, and the clarity and force of its argument. For Lucretius, reason, not religion, was the only safe guide to life. The only thing that he feared was passionate emotion because it clouds the reason and leads to extremes of behavior, the inevitable result of which is pain. By imparting Epicurus’ views on the true nature of reality and death, Lucretius hoped to convince people that the competition for wealth, fame, and power to achieve immortality, or the frenetic search for pleasure to blot out the fear of death, are completely vain.

Cicero (106 to 43 b.c.e.)

Many people forget that the orator Cicero was also a poet. Like the Novi Poetae, he experimented in a number of genres, but he preferred epic. The only poem of which much survives is an early didactic epic, the Aratea. It is a loose translation of the Phaenomena, a Hellenistic epic by the Stoic philosopher Aratus, who studied the stars and their effect on earthly life. We also have a substantial fragment of an original poem on the career of Marius. Cicero was well regarded as a poet, at least until he produced, late in his life, an epic on the events of 63 b.c.e., the year of his consulship, which was ridiculed for its pompous and self-congratulatory tone.

The study of poetry helped Cicero to become Rome’s greatest orator: rhythm and vivid language are essential tools of the orator. Cicero also studied famous classical Greek orators, like Demosthenes, and trained with the best contemporary Latin and Greek masters, such as Lucius Crassus and Apollonius Molon. He alternated between the Attic and Asian Greek styles (p. 338) as the occasion demanded. He often used his oratorical skill to obfuscate and mislead when his case was weak or polemical, as, for political reasons, it often was. Nevertheless, the surviving published versions of his speeches bring to life the political history of the Late Roman Republic. His voluminous letters to Atticus and other friends do so even more.

Forced to abandon active politics twice, first under the so-called First Triumvirate and then during Caesar’s dictatorship, Cicero tried to help himself and Rome by writing on philosophy and the art of oratory. His study of philosophy, particularly the Stoic, Peripatetic, and Academic Skeptic schools, had grounded him in logic and ethics. In Cicero’s view, they were essential for making the orator into a statesman who could persuade his fellow citizens to adopt the right course. Like Lucretius, Cicero tried to prevent Roman aristocrats from ruining the Republic with their destructive rivalries for power and dignitas. Unlike Lucretius, however, Cicero argued in the De Re Publica that virtuous behavior on behalf of the state would be rewarded with a blessed afterlife among the gods. Indeed, in other works, he expressly refuted Epicurean views of the gods and human happiness. He believed that men should be intensely involved in public affairs. A state guided by an enlightened leader of outstanding prestige, a princeps civitatis (First Man of the State), with a senate and citizenry performing their separate duties, would guarantee stability and happiness by reconciling individual freedom with social responsibility. He was clearly looking to Pompey to fill the leading role at one point but was sorely disappointed in the result. Ultimately, Octavian would play the part of princeps civitatis more effectively later (p. 346).

Sallust (86 to ca. 34 b.c.e.)

Like Cicero, the historian C. Sallustius Crispus, or Sallust, had come from a small Italian town, Amiternum in central Italy, and had started on a senatorial career. As a tribune in 52, he associated himself with Publius Clodius. When Clodius was murdered later that year, Sallust played a leading role in burning down the senate house at his funeral and opposing Cicero, who unsuccessfully defended Milo, Clodius’ murderer, in court.

The optimate censor of 50 b.c.e., Appius Claudius Pulcher, Clodius’ brother, expelled Sallust from the senate. Sallust sought to restore his position by serving Julius Caesar in the civil war against Pompey and Caesar’s optimate enemies. His reward was election to the praetorship in 46 and governorship of the revamped province of Africa. He enriched himself scandalously at the provincials’ expense and was tried for extortion. Caesar’s influence seems to have saved him, but his political career came to an end.

Sallust retired from politics and for the rest of his life wrote historical monographs in the style of the Greek historian Thucydides and, with some hypocrisy, condemned the Roman nobility’s ambition, corruption, and greed. By writing history, Sallust hoped to find the glory that he had failed to achieve in politics. He wrote three historical works: first, the Bellum Catilinae (The War of Catiline); second, the Bellum Jugurthinum (The Jugurthine War); and finally, the Historiae (Histories), whose five books covered events from 78 to 67 b.c.e. and may have been unfinished at his death. The first two works are extant, while only fragments of the Histories remain.

Caesar (100 to 44 b.c.e.)

Julius Caesar’s success as a general and politician was based in no small part on being both an accomplished orator and a consummate literary stylist. His skills as a speaker and writer enabled him to win the loyalty and devotion of his troops, acquire votes, and create a positive public image to counter the accusations of his foes. Caesar favored the straightforward, lightly adorned Attic style.

By 50 b.c.e., Caesar had published the first seven books of De Bello Gallico (On the Gallic War). The eighth book was later written by his loyal legate Aulus Hirtius. The three books of De Bello Civili (On the Civil War) were probably written in late 48 or early 47 b.c.e. but were not published until after Caesar’s death. The De Bello Gallico, other than presenting a descriptive military narrative, is a masterpiece of understated self-glorification and propaganda. It seems to have been read as dispatches from the front to the people of Rome to advertise the wealth and territory that Caesar was winning for them. These dispatches also justify his gratuitous conquests of the Gauls by calling up the memory of wrongs that the Romans and Caesar’s own family had suffered in past generations and raising the specter of new Gallic hordes attacking Rome. On the Civil War is different. Because waging civil war was one of the worst of crimes in Roman society, he had to show extreme provocation: a small group of ultra-reactionaries had perversely driven him to defend his honor and dignity and the good name and best interests of the Roman People. The men are shown as cruel and vain, cowardly in battle and ignominious in defeat. There are no outrageously false statements in the account, but the truth may be said to have been tested for elasticity.

Scholarship and patriotic antiquarianism

Many of Rome’s greatest writers were being shaped by the events of this period and would blossom into maturity after the civil wars came to an end in 30 b.c.e. Arcane scholarship and antiquarian research were safer than other genres that might offer overt critique of those in power. Scholars and antiquarians often exhibit a nostalgic longing for a glorious past and a desire to gain control over the present through research and philosophy.

Marcus Terentius Varro (116 to 27 b.c.e.)

The best representative of such authors is Marcus Terentius Varro. He fought against Caesar at Pharsalus but was pardoned. Caesar admired his great learning in works on history, law, religion, philosophy, education, linguistics, biography, literary criticism, and agriculture. He even entrusted Varro with creating Rome’s first great library, which was never finished. Varro’s greatest work was probably the Antiquities Human and Divine. It contained a vast array of knowledge, as well as many errors. In this work, Varro fixed the canonical date for the supposed founding of Rome by Romulus as April 21, 753 b.c.e. Of his numerous writings, the only ones to survive in more than small fragments are his three valuable books on agriculture; six of his twenty-five books on the Latin language.

Atticus (110 to 32 b.c.e.) and Nepos (ca. 100 to ca. 24 b.c.e.)

Varro based part of his research in early Roman history on a now lost chronology of Rome produced by his and Cicero’s old friend T. Pomponius Atticus (pp. 321–2). Cornelius Nepos, born about 100 b.c.e. in Cisalpine Gaul, was a friend of both Cicero and Atticus and also of Catullus. Nepos’ main contribution was the popularization at Rome of the Greek genre of biography. Before 32 b.c.e., Nepos published the first edition of his sixteen-volume De Viris Illustribus (On Illustrious Men). It contained short biographies of generals, statesmen, writers, and scholars, both Roman and non-Roman, in an easy-to-read style. Twenty-five biographies survive. Unfortunately, like most ancient biographers, Nepos was more interested in drawing moral lessons than in historical accuracy. His real contribution is his multicultural emphasis on Persians, Carthagians, and Greeks to show the Romans that they had no monopoly on talent and virtue.

The cultural legacy of the late Republic

Politically, those who were the last generation of the Roman Republic had not been able to preserve the traditional constitution. They did not meet the challenges produced by the acquisition of a vast empire and the great social and economic changes that had ensued. Culturally, however, they must be credited with great accomplishments. In art, architecture, rhetoric, literature, and scholarship, they were worthy successors to the Greeks of earlier generations. They had advanced the distinctive blending of Greek and native Italic traditions that was the hallmark of Roman culture to the point where the next generation of Roman artists, architects, writers, and thinkers could produce a new Golden Age. It would rival that of Classical Greece and become the dominant cultural force in Western Europe for centuries.

Suggested reading

Rawson , E. Intellectual Life in the Late Roman Republic. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1985.

Wallace-Hadrill , A. Rome’s Cultural Revolution. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2008.