Chapter 20

While Augustus had been working out his unique governmental position and making extensive administrative and social reforms at Rome, he also had to secure the safety and stability of what can now be called the Roman Empire. Military and fiscal reforms and the establishment of defensible (but not static or permanent) provincial frontier zones were essential for this effort. Augustus’ primary motive always was to secure the benefits of empire for Rome and Italy in a world safely structured around the unifying core of the Mediterranean Sea, Mare Nostrum (Our Sea), as the Romans justly called it. He wanted to be remembered as the bringer of peace, prosperity, and increased power to the Roman People. Although he preferred subtler and gentler means, Augustus had no qualms about ruthlessly crushing anyone or anything that stood in the way of that primary goal. Therefore, the process that created the Pax Romana (Roman Peace) was not always experienced as peaceful or benign by those who were to serve Rome’s and Augustus’ glory.

Military reforms

In 27 b.c.e., to prevent the rise of powerful military commanders who could have undermined his own power and the peace that he earnestly wished to give the Roman Empire, Augustus had obtained for himself the provinces containing the most legions. He placed them under the immediate command of his own loyal equestrian legates. Moreover, all soldiers were required to take an oath of personal allegiance to Augustus.

Reduced size of army

Augustus’ first step in dealing with military problems, however, had been to reduce the sheer number of men under arms and provide them with their expected grants of land. Both of these steps were necessary to decrease the risk of civil disorder from unoccupied and disgruntled soldiers. They also reduced the crushing economic burden that the huge armies of the civil war placed upon the exhausted treasury. After Actium, Augustus had demobilized about 300,000 men and cut the number of legions from over sixty to perhaps twenty-eight (about 160,000 men).

He avoided the harsh confiscations that had accompanied his settlement of discharged veterans in 41 b.c.e. New colonies in Italy and throughout the Empire provided land for his veterans. They also helped to increase the security and Romanization of the surrounding areas. The vast wealth of Egypt gave Augustus the funds necessary to carry out this colonization scheme without increasing taxes or denying compensation to those whose land was used for colonial settlements.

A retirement system

Eventually, it became impractical to give all veterans land upon discharge. To have done so on a regular basis would have required a costly administrative system. Good land would have become prohibitively expensive as peace and stability encouraged the rapid growth of population once more. Outright confiscation would have revived rural unrest, and distributing cheap waste or marginal land would have left a dangerous number of disgruntled veterans.

Therefore, beginning in 13 c.e., Augustus began to reward many veterans with a system of monetary payments to provide them with financial security upon discharge. Praetorian guardsmen received grants of 5000 denarii and ordinary soldiers 3000, the equivalent of almost fifteen years’ pay. That is far more money than the average person could have saved in a lifetime. Moreover, soldiers were encouraged, and later required, to save some of their pay in a fund kept at legionary headquarters. Spent wisely, their savings and discharge bonuses alone, on the average, would have supplied the daily needs of veterans for as long as they might expect to live after retiring at thirty-five or forty years of age. On the other hand, a retired veteran could invest his money in a small farm or open up a small shop to support himself in retirement. A higher paid centurion might even have enough from his bonus and savings to acquire equestrian status and pursue a career in higher offices after retirement. The auxiliary troops, however, did not fare as well. Because their bonus, if any, was small, their greatest reward was the diploma of citizenship.

During the years from 7 to 2 b.c.e., Augustus paid discharged veterans no less than 400 million sesterces from his own funds. Still, even his resources could not stand that kind of expense forever. Therefore, in 6 c.e. he shifted the burden to the state by setting up a special fund (aerarium militare). He contributed 170 million sesterces of his own money at the start. For the future, he funded it with the revenues from certain taxes (p. 365), as well as with gifts and legacies received from his subjects and clients.

Professionalization

Augustus created a permanent professional army commanded by men loyal to him and to Rome. Terms of service and rates of pay were regularized. Ordinary soldiers received 225 denarii a year and, at first, were required to serve sixteen years. Later, to relieve the strain on manpower and reduce the drain on retirement funds, the official term was raised to twenty years, but men might be kept in service even longer.

The backbone of the army was the corps of professional officers composed of the centurions. Under the Principate, they were the lowest commissioned officers and commanded the individual cohorts of the legions. They were often promoted from the ranks of the noncommissioned officers and received triple pay and bonuses. The ranks from military tribune on up were held by equestrians and younger members of the senatorial class in preparation for higher civilian careers. The highest officers were usually members of Augustus’ family or were nobles of proven loyalty.

The individual legions were made permanent bodies with special numbers and titles. Through the use of identifying symbols for each legion, a soldier was encouraged to develop a strong loyalty to his unit and strive to enhance its reputation. Each legion tended to be stationed permanently in some sector of the frontier. Many important cities in Europe grew up around such legionary camps.

Legionary soldiers were recruited primarily from Roman citizens in Italy and heavily Romanized areas such as Spain and southern Gaul. In the East, freshly enfranchised natives were also used. Each Roman legion was accompanied by an equal number of auxiliary forces, particularly cavalry, from warlike peoples in the less developed parts of the Empire and from non-Roman allies. They often supplied whole units along with their native officers. Regular pay for auxiliaries was only seventy-five denarii a year, and their term of service was twenty-five years.

The combined total of legionary and auxiliary forces under Augustus was between 250,000 and 300,000 men, not too large an army for defending a frontier at least 4000 miles long. Of the twenty-eight legions, at least eight guarded the Rhineland and seven the Danubian region. Three legions were in Spain, four in Syria, two in Egypt, one in Macedonia, and one in Africa. The equivalent of two others were scattered in cohorts in Asia Minor, Judea, and Gaul.

The Praetorian Guard

In Italy itself, however, Augustus stationed the nine cohorts of the Praetorian Guard. They were specially recruited Roman citizens and were called the Praetorian Guard after the bodyguard of republican generals. Each cohort probably contained 500 (later 1000) men. Three were stationed near Rome and six others in outlying Italian towns. As privileged troops, the praetorians served for only sixteen years and received 375 denarii a year, with 5000 upon discharge. Many praetorians were promoted to legionary centurions.

The imperial Roman navy

The war with Sextus Pompey and the Battle of Actium clearly demonstrated the need for a sizable Roman navy. To suppress piracy, defend the shores of Italy, and escort grain transports and trading ships, Augustus created two main fleets, one based at Misenum on the Bay of Naples, the other at Ravenna on the Adriatic. He had other fleets also, especially at Alexandria and, for a time, at Forum Julii (Fréjus) in southern Gaul. The sailors were largely provincials from the Dalmatian coast but included some slaves and freedmen. They served under the command of prefects who were sometimes equestrians but more often freedmen. Auxiliary river flotillas patrolled the Nile, the Rhine, the Danube, and the major rivers of Gaul.

Vigiles and cohortes urbanae

Augustus created the vigiles and cohortes urbanae to fight fires and maintain public order in Rome (p. 354). They were organized along military lines but were not considered part of the military. The vigiles consisted of seven cohorts 1000 men apiece, and each was in charge of two of the fourteen regions into which Augustus divided Rome. The three urban cohorts had 1000 to 1500 men each. The vigiles were recruited from freedmen and commanded by an equestrian prefect of the watch (praefectus vigilum). The cohortes urbanae were freeborn citizens commanded by the new prefect of the city (praefectus urbi), a senator of consular rank.

Protection of the emperor

The Praetorian Guard, the vigiles, and the urban cohorts not only preserved law and order in Rome and Italy but also were effective means of preventing or suppressing secret plots and rebellions against Augustus. Accompanying the establishment of these protections was Augustus’ use of the Law of Treason (maiestas, p. 235). It was vague, flexible, and sweeping, encompassing all offenses from conspiracy against the state to insulting or even disrespecting the emperor in speech, writing, or deed. In light of Caesar’s assassination, conspiracies such as that uncovered ca. 23 b.c.e. (p. 348), and the numerous civil wars of the previous century, Augustus was understandably anxious about plots against himself and the state. He was sensible and restrained in applying the law of maiestas. Yet, in the hands of insecure, inexperienced, and immature emperors, the law could be subject to deadly abuse. Sometimes, people acting as informers, delatores (sing. delator), would try to settle a grudge by accusing an enemy of plotting against an emperor. Indeed, there was an incentive for informers to prey upon an emperor’s fears by accusing innocent people of maiestas. If someone whom a delator accused of maiestas was convicted, the delator received one-fourth of his property.

Fiscal reforms

Before the Principate of Augustus, the civil wars of the late Republic had depleted the funds of the old senate-controlled state treasury, the aerarium Saturni, and exhausted its revenues. The old system of tax collection, corrupt and inefficient at best, had completely broken down. The absence of any formal budget, regular estimate of tax receipts and expenditures, or census of taxable property made an already bad situation worse. Despite the urgent need for action, Augustus at first moved slowly and circumspectly. He wished to avoid in every way the suspicion of ruthlessly trampling upon the ancient prerogatives of the senate. In 28 b.c.e., he requested a transfer of control over the state treasury from inexperienced quaestors to ex-praetors selected by the senate. Their duties were given to two additional annual praetors after 23 b.c.e. Because Augustus’ greater income enabled him to subsidize the state treasury, he soon acquired virtual control over all the finances of the state.

He was content with informal control, however. After 27 b.c.e., he set up, for each imperial province, a separate account or chest called a fiscus (literally, “fig basket”), into which he deposited the tax receipts and revenues of the province for payment to the legions. The fisci not only helped him, as sole paymaster, to assume complete mastery of the armies. They also enabled him to take control over the administration of the Empire. Years later, Claudius united the several fisci into a single, central fiscus. It then became in fact and in law the main treasury of the Roman Empire and was administered separately from both the aerarium Saturni and the aerarium militare. Augustus had also continued the Republic’s practice of maintaining a special sacred treasury, the aerarium sanctius, to provide financial reserves for military emergencies.

Augustus had still another fund, the patrimonium Caesaris, of fabulous size, though not strictly a treasury. It consisted of Julius Caesar’s private fortune, the confiscated properties of Antonius, the vast treasures of Cleopatra, the revenues from Augustus’ private domains in the provinces, and the numerous legacies left him by wealthy Romans. (The legacies alone amounted to the huge sum of 1.4 billion sesterces.) The public treasuries and his enormous personal funds gave Augustus financial control over the entire administration of the Empire.

Taxation

To fund the aerarium militare, Augustus instituted a 5 percent tax on inheritances from well-off Roman citizens without close heirs and made use of a 1 percent tax on auctions. Another new tax, 2 or 4 percent on the sale of slaves, probably funded the vigiles. Augustus also levied a tax of as much as 25 percent on imports from outside the Empire and customs dues of 2 to 5 percent on the shipment of goods from one province to another. They were collected by tax contractors who paid the aerarium Saturni before collecting the taxes themselves. Augustus replaced the old provincial taxes of stipendium and tithe with a poll tax, called the tributum capitis (collected from all adults in some provinces and just adult males in others), and the tributum soli, a percentage of one’s assessed property. Both taxes were determined by a periodic census and were deposited in the provincial fisci to cover the expense of imperial defense and administration. The 5 percent tax on the manumission of slaves (p. 357) probably went into the special reserve treasury (aerarium sanctius).

Provincial reforms

The loyalty of the provinces required stable, efficient, and honest administration, with due regard for the provincials themselves. To ensure such administration, Augustus kept firm control over both imperial and senatorial governors. He strengthened the laws against extortion, and reformed the system of taxation by instituting a census of property at regular intervals. Subdividing or rearranging large provinces were other ways to achieve greater administrative efficiency and control. Augustus curbed the power of the tax-farming companies and gradually transferred the collection of direct taxes to quaestors and procurators assisted by local tax officials. Particularly in the East, those reforms made possible a rapid economic recovery and commercial expansion and helped Augustus win the loyalty of the provincial peoples.

The princeps respected local customs as much as possible. He also gave the provincials considerable rights of self-government. That encouraged the growth of urban communities out of villages, hamlets, and temple lands. Accordingly, he allowed the town councils (curiae) and the leagues (consilia or koina) of the provincial cities and tribes freedom of assembly and the right to express gratitude or homage and bring their grievances to the attention of the emperor or the senate.

Egypt was a special case. For millennia it had been the personal estate of its kings. To have imposed a new system might have been disruptive. Also, it was to Augustus’ advantage simply to take the place of the ancient pharaohs and Hellenistic Ptolemies in order to keep Egypt’s vast wealth and vital grain out of the hands of potential challengers. Therefore, he treated it as part of his personal domain and declared it off limits to Roman senators without special permission. He and his successors administered it through special prefects of equestrian rank.

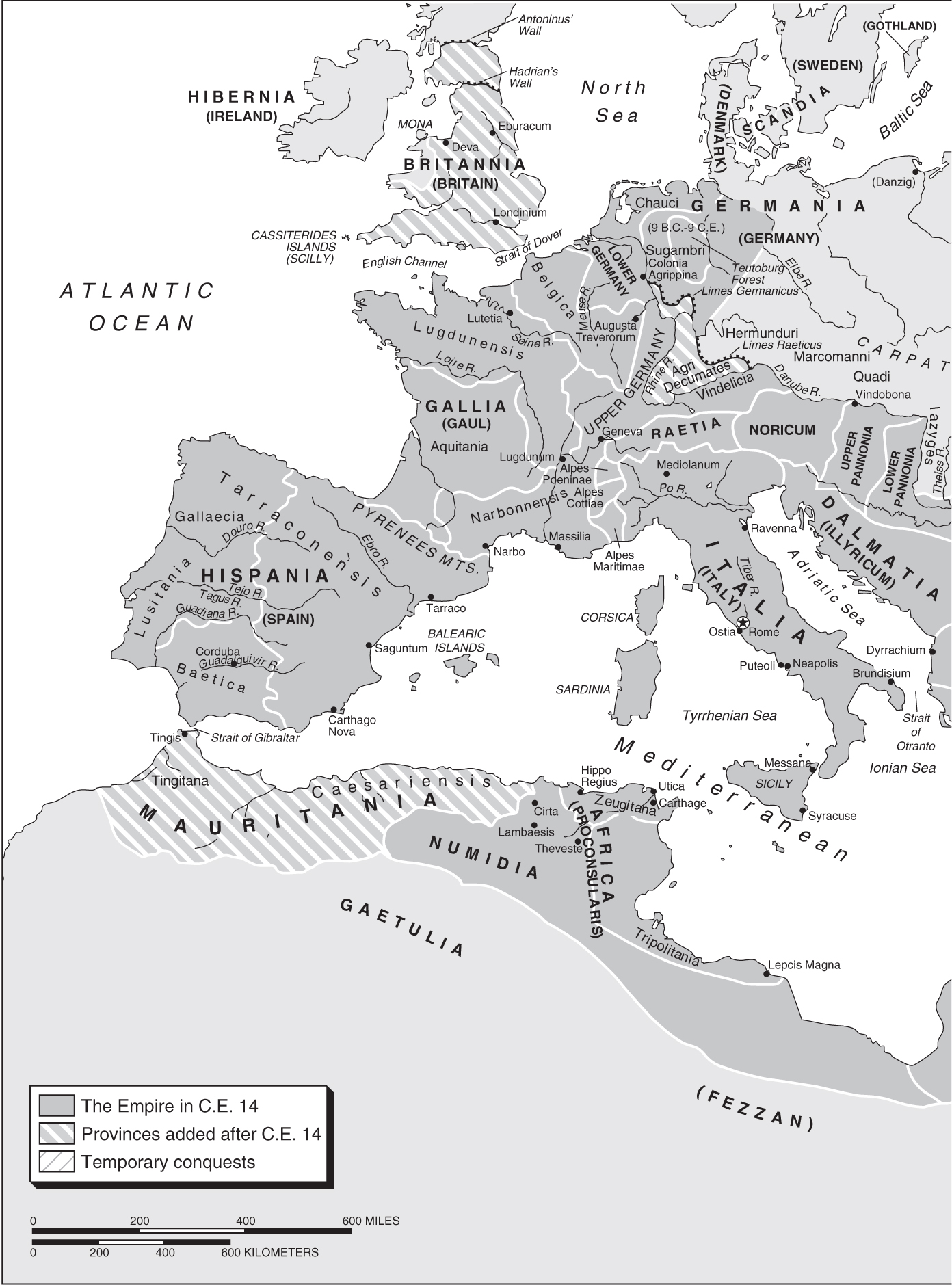

To round out the conquest of the Mediterranean basin and expand imperial power to the most defensible geographic frontiers, Augustus added a number of new provinces and extended Roman control over other territories. By 14 c.e., there were twenty-eight provinces, ten of which were senatorial and eighteen imperial (map, pp. 368–9). From the Roman point of view, his policy was a great success and earned Augustus much prestige in a society that valued military prowess highly. It was not, however, always a pretty story in human terms. A century later, the historian Tacitus grasped the reality faced by the native peoples whose independence and homelands were destroyed in the process of creating the Roman Peace (Pax Romana). He has a native leader say of the Romans, “With false words they call robbery, murder, and rape ‘empire’ and where they have created an empty waste, ‘peace’” (Agricola, 30.5).

Conquests in the West

The policy of conquest was very evident in the West. There were still large areas near Italy that the Romans had not yet attempted to take over. It was necessary to do so, however, in order to protect Italy, the heart of the Empire, and secure efficient communications with the outlying territories. From 27 b.c.e. to 9 c.e., therefore, Augustus methodically rounded out imperial conquests in the West.

Spain and Gaul, 27 to 22 b.c.e.

Augustus personally led the fight against the Cantabrians and Asturians of northwestern Spain in 27, but his always-delicate health failed in 26, and he left in 24. Agrippa suppressed the rugged tribesmen years later through the brutal expedients of massacre and enslavement. In Gaul, Caesar’s thorough victories left Augustus nothing more than minor campaigns in Aquitania and administrative reorganization. In 22 b.c.e., he transferred Gallia Narbonensis to the senate. He divided old Gallia Comata into three administrative parts: Aquitania, Lugdunensis, and Belgica, each under a separate legate subject to the governor, who had his headquarters in Lugdunum (Lyons).

The Alpine districts, 25 to 14 b.c.e.

Although the Roman Empire now extended from the Straits of Gibraltar to the Euphrates, the Alpine region had remained unsubdued and menaced Italy. In 25 b.c.e., a decisive victory and ruthless enslavement removed the menace. In the northern and eastern Alps, Roman armies subdued Raetia (eastern Switzerland, southern Bavaria, and western Tyrol) and Noricum (eastern Tyrol and western Austria) from 17 to 14 b.c.e. Those efforts were led by Augustus’ stepsons, Tiberius Claudius Nero (Tiberius) and Nero Claudius Drusus (Drusus I). All the tribes near the headwaters of the Rhine and the Danube became Rome’s subjects. The upper Danube then became Rome’s northern frontier in the West.

Failure on the German frontier, 12 b.c.e. to 9 c.e.

Augustus’ only failure on the frontiers was in Germany. Augustus wanted to cross the Rhine and push the frontier to the Elbe (Albis) and, later if possible, to the Vistula. The operations of Drusus I from 12 to 9 b.c.e. spectacularly accomplished the initial goal. Unfortunately, Drusus broke a leg by falling from a horse and later died of complications. Tiberius then handled matters effectively in Germany until he was called away to suppress a serious rebellion in Pannonia and Illyricum from 6 to 9 c.e. In 9 c.e., however, the German leader Arminius ambushed Quinctilius Varus and three legions in the Teutoburg Forest. Few escaped, and Varus committed suicide.

Although Augustus was unable to replace the three lost legions, he did not abandon an aggressive posture against the German tribes across the Rhine. Still, whether he intended to or not, the subsequent successful campaigns of Tiberius and Drusus’ son Germanicus to avenge Rome’s and his family’s honor never resulted in the extension of Roman administrative control to the Elbe. Not extending such control posed serious strategic problems later. The Rhine–Danube frontier was 300 miles longer than an Elbe–Danube one would have been and required more men to defend. In addition, the headwaters of the Rhine and the Danube created a triangular territory, the Agri Decumates, that would give attackers easy access to Italy and the western provinces if there were a breakthrough in that sector of the frontier.

Western North Africa

Caesar had enlarged Roman territory in western North Africa by the annexation of Numidia as the province of Africa Nova. Augustus was convinced that the enlarged territory was too difficult to defend. He consigned the western part of it to the kingdom of Mauretania (modern Algeria and Morocco). Upon Mauretania’s vacant throne he placed Juba II of Numidia, who had married Cleopatra Selene (Moon), daughter of Antonius and Cleopatra. Augustus combined the rest of Africa Nova with the old Roman province to create an enlarged Africa Proconsularis with its capital at Carthage. Caesar had planned the refounding of Carthage as a colony for retired veterans, but it was Augustus who actually brought the plan to fruition. In addition, Augustus established at least nine other colonies in Africa Proconsularis to provide land for veterans and security for the province. He also fought at least five wars against the tribes on the southern frontiers. Between 21 b.c.e. and 6 c.e., Augustus’ need to cultivate as much grain as possible in Africa to feed Rome’s huge population and the tribes’ need for open access to seasonal pasturage often led to conflict.

FIGURE 20.1 The Roman Empire under the Principate. (Provincial Boundaries ca. 180 c.e.).

Solidifying control of the Balkans, Crete, and Cyrene

The Balkan region (extending from Greece north to the middle Danube), Crete, and Cyrene formed a middle zone between the West and the rich provinces of the East. For the previous century, the Romans had concentrated on establishing their power in Asia Minor and the Levant. Now it was time to pay more attention to these intermediate territories, which sat astride the land and sea routes between the East and West.

The Danubian lands, 14 b.c.e. to 6 c.e.

Long overdue was the conquest of the Danubian lands in the northern Balkans. Illyricum (the modern republics of Bosnia, Croatia, and Macedonia; western Hungary; northern Serbia; and eastern Austria) was constantly disturbed by Pannonian and Dacian tribes. In addition, the Dalmatian coastal regions of Illyricum never had been completely pacified. In 13 b.c.e., Marcus Agrippa took over operations begun in the previous year against the Dalmatians and Pannonians. His heart failed during a harsh winter campaign, and Tiberius finished the task in four years of hard fighting from 12 to 9 b.c.e.

In the eastern Balkans, Thracian uprisings and Dacian invasions from across the Danube during 13 b.c.e. forced Augustus to act. Three years of fighting, from 12 to 10 b.c.e., eliminated the threat but depopulated Moesia (Serbia and northern Bulgaria) along the south bank of the Danube from Illyricum to the Black Sea. Eventually, Roman armies rounded up 50,000 Dacians from across the Danube and settled them in the vacant territory.

By these conquests, Augustus moved the frontier of the Empire away from northeastern Italy and greatly shortened communications between the vital Rhineland and the East. Moreover, although less economically valuable than many provinces, the Danubian lands soon proved to be the best recruiting grounds in the Empire. In later centuries, many of the emperors who fought to preserve the Empire from outside attacks came from this region.

Macedonia and Greece

In 27 b.c.e., Augustus separated Greece from Macedonia by creating the senatorial province of Achaea, apparently with Corinth as its capital. This new province included the Cycladic Islands, Aetolia, Acarnania, and part of Epirus. The island of Corcyra, Thessaly, Delphi, Athens, Sparta, and the League of Free Laconians remained technically autonomous.

Crete and Cyrene

The large island of Crete, despite its strategic location and the suppression of its pirates from 69 to 67 b.c.e., had remained independent during subsequent decades. It was not considered profitable enough for anyone to annex. Augustus finally ended this anomaly in 27 b.c.e. by combining Crete with Cyrene to create a proconsular province for a senator of praetorian rank. Cyrene and other prosperous Greek cities on the east coast of North Africa constituted a territory between Africa Proconsularis and Egypt. It had become a dependency of Egypt under the Ptolemies. Although the Romans had inherited the region from its Ptolemaic ruler in 96 b.c.e., they had done little with it until Augustus.

Holding the East

The problems presented by the East differed widely from those of the West. The eastern provinces were heirs to very old and advanced civilizations and were proud of their traditions. Many had been taken over only recently and were not yet fully reconciled to Roman rule. Beyond the eastern frontier lay the Parthian Empire, a vast polyglot state embracing an area of 1.2 million square miles from the Euphrates to the Aral Sea and beyond the Indus. Within recent memory, Parthia had inflicted three stinging defeats upon the Romans and was still considered a potential menace. As an organized state, however, it was capable of being dealt with through sophisticated diplomacy as well as force.

After Actium, an insistent clamor arose for a war of revenge against Parthia. Without openly defying the demands of public opinion and the patriotic sentiments of authors like Vergil and Horace, Augustus was reluctant to commit himself to a war with Parthia. Even if he could have defeated the Parthians in battle, it is doubtful that he could have committed the time, manpower, and resources to pacify and hold a large bloc of Parthian territory while there were more urgent matters that needed attention in the West. Augustus would try to strengthen Rome’s position and neutralize Parthia by other methods.

Asia Minor and the Levant

In 27 b.c.e., Augustus made only minor adjustments to the provinces established by Pompey in Asia Minor and the Levant. The principal change was the reannexation of Cyprus, which Marcus Antonius had ceded to Cleopatra. Augustus left the provinces of Asia Minor to senatorial proconsuls, but he actively promoted the restoration of stability and prosperity. Ephesus and Pergamum were encouraged to mint large numbers of silver tetradrachms to aid commerce. Augustus himself gave money to restore cities damaged by Parthian attacks and natural disasters. He generously rewarded others for loyalty and honors bestowed upon him.

Client kingdoms

At first, Augustus continued the policy of Marcus Antonius, which was to maintain client kingdoms as buffer states between Parthia and the Roman provinces. After Actium, Augustus consigned large territories in Asia Minor (Galatia, Pisidia, Lycaonia, and most of Cilicia) to Amyntas the Galatian. He also gave eastern Pontus, Lesser Armenia, and the huge realm of Cappadocia to client kings. At the same time, he enlarged Judea, the kingdom of Herod I, the Great (37–4 b.c.e.). Eventually, all the client kingdoms became provinces. When Amyntas died in 25 b.c.e., Rome acquired the vast province of Galatia and Pamphylia. A decade after Herod’s death, Augustus made Judea and Samaria an imperial province—or, rather, a subprovince attached to Syria and governed by prefects.

Armenia and Parthia

In only one kingdom, Armenia, had Roman influence deteriorated after the death of Antonius. Subdued and annexed as a province in 34 b.c.e., Armenia had slipped away from Roman control just before Actium. It had come under the brutal rule of King Artaxias II, who slew all Roman residents in Armenia. Augustus did not avenge their deaths. He made no effort to recover control of Armenia for over a decade, although it provided the best invasion routes from Parthia to Roman provinces in Asia Minor and Syria.

Meanwhile, he preferred intrigue and diplomacy to direct confrontation with Parthia. He gave refuge to Tiridates, a rival of the Parthian king Phraates IV. Tiridates turned over Phraates’ kidnapped son for Augustus to use as a hostage. In 23 b.c.e., wanting to get back his son, Phraates agreed to return the battle standards and all surviving prisoners captured from the Romans at Carrhae (p. 284) or in subsequent Parthian victories. Phraates, however, had still not made the exchange by 20 b.c.e., when Artaxias of Armenia was killed. Augustus immediately sent in Tiberius with a Roman army to place Tigranes III on the Armenian throne. Phraates, now fearful that Augustus might be able to use the army in Armenia to support Tiridates’ seizure of the Parthian throne, handed over the promised prisoners and standards.

A rattle of the saber temporarily restored Roman prestige in the East and wiped away the stains upon Roman honor. Augustus, therefore, shrewdly declared a great victory and silenced further demands for war by advertising his success on coins with such slogans as signis receptis (the standards regained), civibus et signis militaribus a Parthis recuperatis (citizens and military standards recovered from the Parthians), and Armenia recepta (Armenia recaptured).

All was quiet in the East until the death of Tigranes in 1 b.c.e. A group of Armenians, aided and abetted by the Parthians, enthroned a king of their own choice without consulting Augustus. He at once sent out Gaius Caesar, his grandson/adopted son and heir apparent, armed with full proconsular imperium over the entire East. Gaius marched into Armenia at the head of a powerful army. This show of force compelled the Parthians to recognize Rome’s preponderant interest in Armenia and accept a Roman appointee on the Armenian throne. The Armenians subsequently revolted but were suppressed after hard fighting. It was a costly victory, however. Gaius had suffered wounds that would not heal, and he died eighteen months later (4 c.e.).

Parthia, as well as Augustus, had reasons for avoiding war. Torn by the dissensions of rival claimants to the throne and continually menaced by Asian migrations, Parthia was in no position to attack. The Parthians willingly endured diplomatic defeat rather than risk military conflict. They calculated that their own diplomacy and intrigue might eventually succeed; overt aggression might fail and would surely be costly.

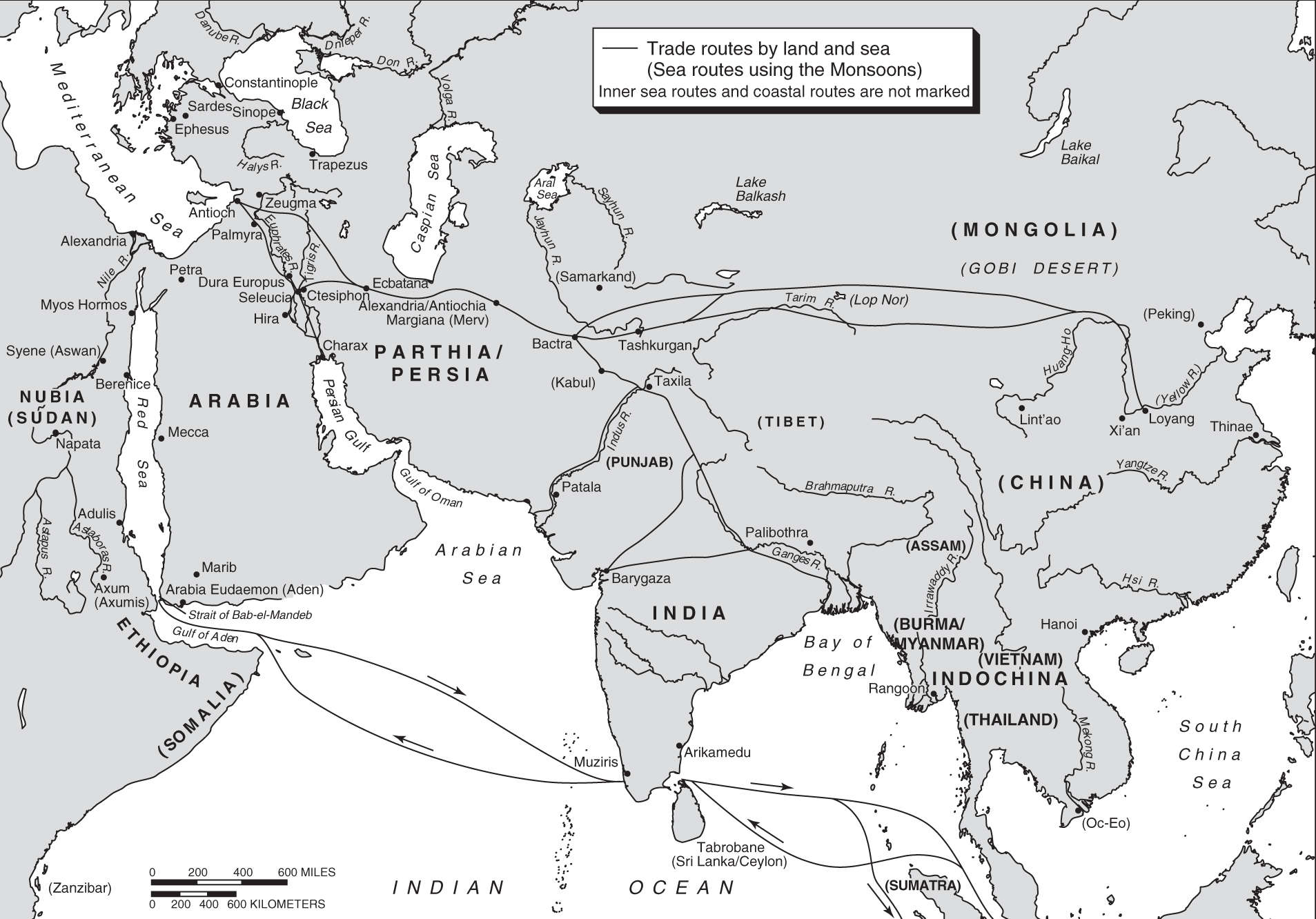

Both Parthia and Rome also had economic interests that would have been ruined by war. Peace along the Euphrates permitted the uninterrupted flow of the caravan trade that brought to each of them luxuries from India, Central Asia, and China. Under joint Parthian and Roman protection, Palmyra was rapidly becoming a large and prosperous caravan city with fine streets, parks, and public buildings. Other cities—Petra, Gerasa (Jerash), Philadelphia (Amman), and Damascus—were also beginning to enjoy the rich benefits of caravan trade.

Egypt and the Red Sea zone

Egypt, richest of all Augustan annexations and producer of one-third of the Roman annual grain supply (5 million bushels), remained relatively quiet except for some skirmishes on the Nubian border in upper Egypt. In 22 b.c.e., after three Roman campaigns in Nubia, the Nubian queen, Candace, agreed to fix the southern boundary of Egypt about sixty miles south of Syene (Aswan) and the First Cataract. It remained there for the next 300 years (map, p. 375).

About this time (25–24 b.c.e.), a Roman expedition, sent down to the Red Sea against the Sabaeans in Arabia near what is now Aden, sought to gain naval control of the Straits of Bab-el-Mandeb. Roman control would allow Alexandrian merchants to break the Sabaean monopoly on trade with India in precious stones, spices, cosmetics, and other commodities. The expedition failed, but it paved the way for more successful ones later.

Road building

The building of roads went hand in hand with conquest, frontier defense, and provincial communication. By 27 b.c.e., Augustus had completed the repair and reconstruction of the Italian roads (much neglected since the time of Gaius Gracchus)—especially the Flaminian Way, a vital artery of the Empire and the main thoroughfare between Rome and the North. After the conquest of the Alpine and Danubian regions, he began the construction of a road north from Tridentum (Trent) on the Adige in the Venetian Alps to Augusta Vindelicorum (Augsburg) on the Lech in Raetia. Other roads ran through the Alps between Italy and Gaul. The completion of this program brought Raetia and Noricum (modern Switzerland and parts of Austria and Bavaria), as well as Gaul, into close and rapid communication with Italy.

The Imperial post (cursus publicus)

Road building made possible another Augustan achievement, the imperial postal service (cursus publicus). Much like that of ancient Persia, the Roman postal service carried official letters and dispatches and transported officials, senators, and other privileged persons. The expense of this service—relays of horses and carriages and the provision of hotel service for official guests—fell upon the towns located along the great highways. That was a burden on many towns, but it was essential to promote swift communication and the centralization of administration. Moreover, as did railroads in the second half of the nineteenth century and national highways in the first half of the twentieth, the routes used by the cursus publicus brought business and travelers to towns located along them.

Colonization

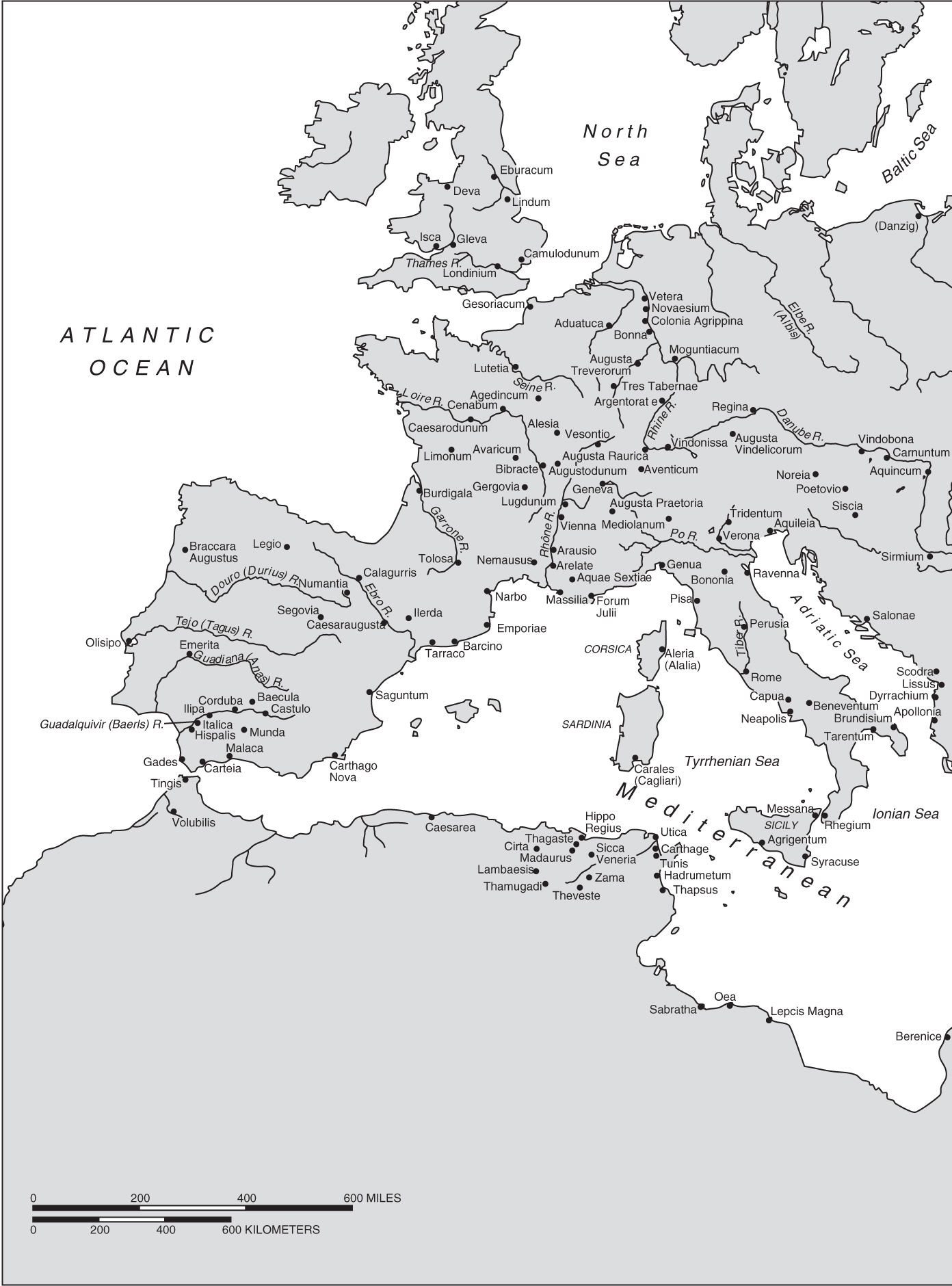

Over the course of his long career, Augustus founded twenty-eight colonies in Italy and perhaps eighty in the provinces. The Italian colonies, mainly of veterans, were very loyal to the new regime. Augustus was not primarily interested in the commercial potential of colonies. He founded few, if any, civilian colonies outside of Italy. Most of his provincial colonies were for the settlement of veterans or served as fortresses or military outposts at strategic points to hold down and secure recently conquered territory in the Alps, Gaul, and Spain. As always, while veteran colonies acted as garrisons, they also helped to spread the use of the Latin language and Roman law among the conquered peoples. Thus, they became important agents of Romanization. In time, many large and prosperous communities grew out of veteran colonies. A number provided the original foundations of well-known modern cities: Barcelona (Barcino), Zaragoza (Caesaraugusta), and Merida (Emerita) in Spain; Vienne (Vienna), Nîmes (Nemausus), and Lyons (Lugdunum) in France; and Tangier (Tingis) in Morocco (map, pp. 378–9).

FIGURE 20.2 East Africa, Arabia, and the Far East.

Urbanization of the provinces

Colonization probably should be seen as part of a long-term policy to promote urbanization and the growth of urban elites in general. The new cities would help to unify the Empire by the diffusion of Roman culture and would serve the central government as convenient administrative units for the collection of taxes and other useful functions. No doubt, too, Augustus realized that since the urban elites would owe their privileged position to the central government, they would in turn support the new imperial regime with vigor and enthusiasm.

Growth of the Imperial cult

The growth of emperor worship throughout the Empire was also useful in strengthening ties of loyalty to both Rome and the princeps. The people of the eastern provinces had long been used to worshiping their rulers as gods. When Augustus became ruler of the Roman world, many easterners began to establish cults for his worship. Augustus, however, was reluctant to be worshiped too directly. Whatever his personal feelings, it certainly would have entailed the political risk of alienating jealous or conservative nobles. Augustus insisted, therefore, that official provincial cults for his worship be linked with the goddess Roma. By 29 b.c.e., before he had received the title Augustus, temples of such cults already existed in the East. Later, with Augustus’ encouragement, such cults appeared in the western provinces, too. Each cult included a yearly festival and periodic games managed by a high priest elected from among the leading aristocrats of the city or provincial assembly (concilium, koinon) that maintained it. In this way, the provincial elite became identified with, and loyal to, both Rome and the emperor. Thus, the cautious promotion of emperor worship built a basis for imperial unity that bridged the different local and ethnic traditions of a huge polyglot empire.

The problem of succession

The problem of who would be the next princeps gave Augustus more difficulty than all the rest of the problems that he had faced. A smooth transfer of power would be essential for preserving the Principate and the stability of the Empire after his death. Legally and constitutionally, the choice of a successor was not his right, but that of the senate and the Roman People. Nevertheless, he feared that his failure to deal with the question beforehand might bring about a civil war after his death. Also, he naturally hoped to find a successor in his own family and of his own blood. Unfortunately, he had no sons and only one daughter, Julia, who had been married in 25 b.c.e. to his eighteen-year-old nephew M. Claudius Marcellus, Octavia’s son by her first husband. Augustus assiduously promoted the political advancement of his son-in-law so that he would have accumulated the experience and prestige that would make him the natural one to succeed to the Principate.

Unfortunately, Marcellus was not old enough when Augustus fell gravely ill in 23 b.c.e. Therefore, the princeps gave his signet ring to Agrippa, his longtime friend, loyal aide and most successful general, to indicate that he should carry on in his place. If Augustus had died then, Agrippa probably would have acted as some kind of regent until Marcellus had matured into the position of princeps. Even when Augustus recovered, however, Agrippa shouldered a bigger share of the government thereafter.

First, Augustus gave Agrippa command over the imperial provinces and the task of strengthening the East against Parthia. Marcellus’ sudden death later in 23, just after Agrippa’s departure, fueled speculation, both ancient and modern, that Agrippa and/or Livia had a hand in the death to benefit Agrippa or Livia’s sons. That seems merely to reflect malicious gossip aimed at discrediting later emperors descended from them. Augustus certainly did not suspect them. Instead, he relied on Agrippa even more.

In 21 b.c.e., Augustus sent for Agrippa and prevailed upon him to divorce his wife and marry Julia. In 18 b.c.e., he obtained the extension of Agrippa’s imperium over the senatorial provinces as well as the imperial ones and even had the tribunician power conferred on him for five years. Agrippa was now son-in-law, coregent, and heir presumptive to the Augustan throne. Nor was that all: in 17 b.c.e., the princeps adopted, under the names of Gaius and Lucius Caesar, the two young sons of Julia and Agrippa. That would have settled the problem of succession not just for one, but for two generations to come.

When Agrippa died in 12 b.c.e., however, Lucius and Gaius were still too young. Augustus then turned to Livia’s older son, Tiberius. Tiberius had served Augustus well on numerous military assignments and had held the consulship in 13 b.c.e. Augustus now made Tiberius divorce Vipsania, a child of Agrippa’s first marriage, and marry Julia, the young widow of Marcellus and Agrippa. Julia bore Tiberius a son who died in infancy. Soon thereafter, the marriage soured. Supposedly, Julia turned to other lovers. If so, her motives may have been more dynastic than Dionysiac as she and Scribonia sought to promote Julia’s sons by Agrippa ahead of Livia’s son Tiberius in the line of succession to Augustus. Augustus had come to rely more and more on Tiberius after the latter’s popular and talented younger brother, Drusus I, had died in 9 b.c.e. (p. 367). Tiberius, however, became frustrated and angry that Julia’s inexperienced sons Gaius and Lucius seemed to receive advancement at his expense, despite his years of experience and hard work in loyal service to Augustus. In 6 b.c.e., therefore, he badgered Augustus to let him retire to Rhodes. Eventually, Augustus himself became disturbed enough by Julia’s conduct to take action against her and important men associated with her. The latter included the younger son of Fulvia and Marcus Antonius, Iullus Antonius, who had received clemency, high office, and a marital alliance from Augustus. In 2 b.c.e., Augustus officially charged them with adultery, a crime that emperors often alleged to cover up more political reasons for prosecutions. Iullus was either executed or forced to commit suicide. Others, including Julia, were relegated (banished) to small islands. Scribonia showed her support for Julia by voluntarily going with her. Even Tiberius, as well as crowds of demonstrators, unsuccessfully interceded on Julia’s behalf. The princeps would not relent, but in 4 c.e., he did permit her to move to Rhegium, where she eventually died (p. 406). One of her daughters by Agrippa, Julia the Younger, suffered banishment in 8 c.e. for similar reasons. At that time, the poet Ovid was somehow involved, and he, too, was forced into bleak exile.

The more Augustus sought to ensure his successor, the more many members of old senatorial families realized that he meant to establish a dynastic Principate that would not permit them to compete for being the leading man of Rome. Some hoped to make use of the rivalries and jealousies within the imperial family to promote a successor favorable to themselves. As time went on, Augustus began to take harsher measures against those deemed unsympathetic to his plans and wishes.

Fate always seemed to intervene on behalf of Tiberius’ succession. In 2 c.e., Augustus reluctantly let Tiberius return after the attractions of Rhodes had worn off. Unfortunately, Lucius Caesar died on the way to Spain a little later that year, and Gaius Caesar died less than two years after that (p. 373). In grief and frustration, Augustus adopted Tiberius as his son in 4 c.e. and obtained a ten-year grant of the tribunician power for him, as well as a grant of imperium in the provinces. Over the years, Tiberius clearly acquired the position of a coregent as Augustus became older and frailer. In 13 c.e., when Tiberius’ tribunician power was renewed along with another grant of imperium for both him and Augustus, there was no question that he was Augustus’ equal partner. When Augustus died a year later, Tiberius was already in place, and the smooth succession for which Augustus had constantly labored automatically took place.

FIGURE 20.3 Cities of the Roman Empire.

Still, in his attempt to secure the eventual succession of a member of his own family, the Julii, Augustus had complicated things for the future. At the same time that he had adopted Tiberius, he had also adopted Agrippa’s posthumously born son by Julia, Agrippa Postumus, a move that he soon came to regret (p. 405). He had also required Tiberius to adopt Germanicus, son of Tiberius’ own dead brother, Drusus I. Germanicus’ mother, Antonia the younger, had given him the blood of Augustus’ family because she was a child of the marriage between Augustus’ sister, Octavia, and Marcus Antonius. The Julian family tie was further strengthened by having Germanicus marry Agrippina, another child of Julia and Agrippa. Tiberius’ own son, Drusus II, who was not a blood relative to Augustus, received Germanicus’ sister, widow of Gaius Caesar, as his wife. Those attempts to manipulate the succession in favor of Augustus’ own Julian side of the imperial family created unfortunate tensions and rivalries in later generations of his Julio-Claudian dynasty.

The death of Augustus

At last, after a political career of almost sixty years, on August 19 of 14 c.e., in the Campanian town of Nola, Augustus met a peaceful death (see Box 20.1). Nearly seventy-seven years old, he was ready, serene, cheerful; not plagued by doubt, guilt, or remorse, although there was much for which he could have been. Dying, he jokingly asked his assembled friends whether he had played out the farce of life well enough. Then he added a popular tag ending from Greek comedy: “Since it has been very well acted, give applause and send us off the stage with joy” (Suetonius, Augustus 99.1). A consummate actor, he had played his part well indeed. The ruthless and bloody dynast of the civil wars had skillfully assumed the role of statesman. The applauding Roman senators, most of whom owed their positions to him, willingly conferred the divinity that he had tactfully refused to claim outright while he was alive.

20.1 Rome’s first Imperial funeral

The funeral of Rome’s first emperor was elaborate and carefully choreographed. The event comprised all the traditional elements of an aristocratic funeral—procession, imagines, eulogy, and spectacle—but in grander dimensions than anything the city had seen before. Public business was suspended so that everyone, not just the imperial family, was free to mourn.

As Augustus’ body was transported the long distance back to the capitol from the family estate where he died, the senators and equestrians who were granted the honor of carrying his body moved it only after dark to avoid the summer heat. During the daytime, the body lay in state in the towns where the procession paused.

The funeral itself began, not with the usual mourners’ parade through the Forum, but with multiple processions that converged there. One brought a wax effigy of Augustus, dressed in triumphal garb, from the imperial palace, another carried an effigy of gold from the Curia Julia, and a third was brought in on a triumphal chariot. The usual parade of actors dressed as the deceased’s most prominent ancestors was enhanced by the addition of images of great Romans of the past: Augustus’ heritage and that of the Roman People were one and the same. After not one, but two eulogies were delivered, all the leading men of the city and their wives escorted the body to the Campus Martius. As the funeral pyre caught flame, an eagle was released to signal that Augustus’ spirit had ascended to the gods above. Livia is said to have stayed by the pyre for five days and then moved his bones to his tomb.

Suggested reading

Lintott , A. Imperium Romanum: Politics and Administration. London and New York: Routledge, 1993.

Garnsey , P. and R. Saller . The Roman Empire: Economy, Society, and Culture. 2nd ed. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2014.