Chapter 21

The Augustan Age witnessed a quickening of economic life throughout the Mediterranean. The ending of civil wars, the suppression of piracy at sea and of banditry and lawlessness in Italy, and the construction of extensive roads in Italy and the provinces brought about a remarkable expansion of agriculture, industry, and commerce. At first, Italy benefited most from the new expansion. The East had not yet recovered from the effects of past wars and exploitation. The western provinces were still too young to take full advantage of the new order. Italy, therefore, continued to dominate the Mediterranean world not only politically but also economically and culturally.

The population and economic impact of Rome

Disturbed conditions during the civil wars from 49 to 36 b.c.e. probably produced a temporary reduction in Rome’s population, a large part of which was always very fluid and transient. Under the Augustan peace, the population rapidly rebounded. It probably reached a million as the princeps improved the attractiveness of Rome by restoring order, improving public amenities, providing for a steady supply of food, and inaugurating a building program that created much employment. In fact, Rome became the greatest metropolis of premodern Europe, if not the whole premodern world.

Within Italy and, therefore, the Empire, the great imperial metropolis drove economic and cultural developments. Until recently, Rome has been viewed in terms of the “consumer” or “parasite” model of the ancient city. According to this line of thinking, most large ancient cities produced little of economic value and served mainly their ruling elites. The ruling elite of a region’s metropolitan center, it is said, inhibited the development of its hinterlands and subject territories. Surplus wealth was siphoned off in the form of rents, taxes, tribute, and spoils in order to support the metropolis as the physical embodiment of its elite’s own greatness. Newer studies, however, based on more extensive archaeological research and comparisons with large cities in other premodern societies, have shown this model to be inadequate.

First, it underestimates the real value of a metropolis’s central administration in suppressing intraregional conflicts and providing defense from external attack. Second, it ignores the impact of the market created by the metropolis’ concentration of surplus wealth. That surplus financed the purchase and transportation of vast quantities of food, goods, and services from the hinterland and subject territories. Under Augustus and a relatively benign central administration, Rome gave the Mediterranean world a prolonged period of internal peace and freed its economy from the destructive conflicts and confiscations of earlier times. Moreover, Rome’s legions freed subject cities and territories from the less efficient maintenance of their own individual armies. As a result, Rome’s subjects had more wealth at their disposal to spur local economic growth, even after the deduction of Rome’s taxes and tribute.

Furthermore, the taxes and tribute used to pay Roman armies on the frontier and build the transportation infrastructure that supported those armies were great stimuli to the economic growth of the frontier provinces. Finally, by subsidizing Rome as the Empire’s metropolis, the wealth that flowed into the city also flowed out into the Italian hinterland, other parts of the Empire, and even beyond to purchase the foodstuffs, raw materials, services, manufactured goods, and luxuries that the city demanded. Those expenditures put more money in circulation, which created even more demand, which supported local and regional economic growth.

From the modern point of view, this economic growth can be considered less than ideal. Much of it was ultimately based on the politically derived purchasing power of the emperor and elite landowners. It was also limited by the lack of many significant technological developments. Profits often rested on the exploitation of slaves and were unevenly distributed in favor of those already privileged. Nevertheless, there was real economic growth, and many ordinary people benefited.

Agriculture

After Actium, Augustus avoided the confiscations that had marked his attempts to settle veterans after Philippi (p. 383). The ranks of the small farmers stabilized throughout Italy. Augustus’ upgraded road system and the growth of cities allowed more small farmers to specialize in high-value products for urban markets. By siphoning off the excess population of the countryside, growing cities also greatly reduced the small farmer’s perennial problem of subdividing land into increasingly uneconomical units among heirs. Growing provincial cities and Rome’s insatiable demand for food had an impact on provincial agriculture similar to that on Italian agriculture. More farmers produced for profitable markets rather than just for subsistence. Although part of Rome’s need for grain was met through taxes in kind on provincial producers, the rest was acquired through purchase. Therefore, landowners in the grain-producing provinces of Sicily, Sardinia, North Africa, and Egypt profited from the enormous efforts to supply Rome and its armies. Similarly, along the Mediterranean coasts of Spain and Gaul and up the valley of the Rhône, vineyards and olive groves were beginning to produce large quantities of wine and oil for the lucrative Roman market.

Agricultural wealth and urbanization

In both Italy and the provinces, the larger landowners profited most from the commercialization and urbanization fostered by Rome, which they largely supported. The wealthy local landowners became the backbone and lifeblood of the curial class (curiales), the local aristocrats who filled the governing councils (curiae) of cities and municipalities all over the Empire. Like their counterparts in the Roman senatorial class, they dedicated a significant part of their agricultural profits to increase their status by building fine residences in the nearest significant city or town and by providing expensive benefactions, such as games, gifts of food, temples, theaters, schools, aqueducts, baths, fora (forums), and porticoes. These amenities attracted more population by making the growing cities and towns more appealing places to live and by creating employment in the building trades and the provision of goods and services to a growing population. Thus, in many places, there occurred an upward spiral of urban development fueled by the profits of local landowners. Some were part of an elaborate network funneling food and raw materials from their estates to Rome. Of course, some of the other growing cities were significant markets themselves and further enriched local landowners who also produced for them (map, pp. 378–9).

Cities of Italy and the Empire

Italian communities particularly well situated within the elaborate network of roads and waterways that funneled supplies to Rome had grown to be rather significant urban centers by the mid-first century c.e. For example, the crucial ports of Puteoli (Pozzuoli) and Ostia, where ships unloaded cargoes bound for Rome, reached populations of 30,000. Regional centers like Mediolanum (Milan), Patavium (Padua), and Capua had populations from 25,000 to as many as 40,000. About twenty-five other centers, including Verona, Cremona, Genua (Genoa), Beneventum, Pompeii, Brundisium, and Rhegium, could be classed as major cities, with populations between 5000 and 25,000.

On the other hand, being too close to Rome or another growing major center could cause decline. Many old cities of Etruria and Latium are good examples. The wealthy landowners in their territories generally concentrated their efforts on acquiring status in Rome itself. Formerly flourishing centers nearby withered and died. Nevertheless, many more places in Italy prospered.

Supplying Rome also stimulated urban growth around the Mediterranean as old centers were refounded or reinvigorated. Julius Caesar had refounded Corinth in 44 b.c.e. In 29 b.c.e., Augustus fulfilled Caesar’s intention of refounding Carthage. Both were prime agricultural sites located on major maritime trade routes. As a result, they quickly grew to be major cities once more. The port of Alexandria flourished as never before and probably reached 500,000 in population. It was the collection point for the vital Egyptian grain shipped to Rome in great fleets. It was also the entrepôt for luxury goods that flowed to Rome and other cities from the upper Nile and the Red Sea (map, p. 375). In Gaul, Lugdunum (Lyons), founded in 43 b.c.e. near the confluence of the Rhône and the Saône, was the hub of the Gallic road system. From its island commercial center at the confluence of the two rivers, Gallic wine and other products were shipped downriver to Arelate (Arles). It grew tremendously under Augustus as a port where seagoing vessels picked up the cargoes from riverboats for shipment to Rome.

Non-agricultural trade and industry

The production and transportation of raw materials and manufactured goods for the lucrative Roman market were also important factors in economic and urban growth under Augustus. Rome’s network of roads and waterways encouraged centers of production to increase output. They shipped their products not only to Rome but also to distant markets, from Jutland (Denmark) to the Caucasus and from Britain to India (map, p. 387).

Textiles

Until the advent of power-driven, mechanized spinning and weaving, cloth was very expensive. It could be shipped long distances in the ancient world at a profit. Patavium (Padua, Padova), located in a major sheep-raising district north of the Po and not far from the Adriatic, became a great center for the production of woolen goods. Its output was so large that in Augustus’ day it is reported to have supplied the huge demand for inexpensive clothing at Rome. Finer grades of woolen goods and purple dye, which was much in demand, came from Tarentum. Silk came from the Greek island of Cos (map, p. 379) and Alexandria supplied the Roman market with linen made from Egyptian flax.

The glass industry

The thriving glass industry had been revolutionized around 40 b.c.e. by the Syrian (or Egyptian) invention of the blowpipe. It made possible the production of not only beautiful goblets and bowls but even windowpanes. From the glass factories of Campania or of the Adriatic seaport of Aquileia came wares that found their way as far north as the Trondheim fjord in Norway and to the southernmost borders of Russia.

Arretine pottery

Manufacturers of red Samian ware, terra sigillata, at Arretium in Etruria and later at Puteoli had become highly successful. By the time of Augustus and Tiberius, they had achieved mass production and were exporting as far west as the British Midlands and as far east as modern Arikamedu near Pondicherry (ancient Poduke?) in southeastern India (p. 375). One Arretine operation had a mixing vat for 10,000 gallons of clay and required up to forty expert designers and a much larger number of mixers, potters, and furnacemen. Some manufacturers were now establishing branch operations in southern and eastern Gaul, in Spain, in Britain, and on the Danube.

FIGURE 21.1 Products and trade of the Roman Empire.

The metal industries

Augustan Italy led the world in the manufacture of metalware. The chief centers of the iron industry were the two great seaports of Puteoli and Aquileia. The iron foundries of Puteoli smelted ores brought by sea from the island of Elba and, by a process of repeated forging, manufactured arms, farm implements, and carpenters’ tools that were as hard as steel. Aquileia, with easy access to the rich iron mines of recently annexed Noricum, also manufactured excellent farm implements. They were sold throughout the fertile Cisalpina and exported to Dalmatia, the Danubian region, and even Germany.

For the manufacture of silverware (plates, trays, bowls, cups, and candelabra), the two leading centers were Capua and Tarentum (map, p. 378). Capua was also famous for bronze wares (statues, busts, lamp stands, tables, tripods, buckets, and kitchen pots and pans). Capuan manufacturers using perhaps thousands of workmen had evolved a specialization and division of labor usually associated with modern industry. The immense export trade of Capua to Britain, Germany, Scandinavia, and south Russia continued unabated until Gaul established workshops first at Lugdunum and, around 80 c.e., farther north in the Belgica and the Rhineland.

Building supplies and trades

The extensive building program of Augustus and the large sums spent on beautifying the Empire’s capital stimulated the manufacture and extraction of building and plumbing materials—lead and terracotta pipes, bricks, roof tiles, cement, marble, and the so-called travertine, a cream-colored limestone quarried near Tibur. Some of these operations seem never to have developed large, systematized methods of production. Lead pipes, for instance, were made in small shops by the same people who also laid and connected them. On the other hand, the making of bricks and tiles reached a high degree of specialization especially on senatorial and imperial estates, which produced materials in large volumes for public works. Almost nothing, however, is known about the organization of the enterprises that made cement, a mixture of volcanic ash and lime, which was also in great demand.

The queen of building materials was marble. The Romans imported many varieties: the famous marbles of the Greek Aegean; the fine white, purple-veined varieties of Asia Minor; the serpentine and dark red porphyries of Egypt; and the beautiful, gold-colored marble of Simitthu in Numidia. Also, in Augustus’ time, they began to quarry marble in Italy: the renowned white Luna (Carrara) marble in Etruria and all those remarkable colored varieties of greens and yellows or mixed reds, browns, and whites found north of Liguria in the Italian Piedmont, in Liguria itself, and near Verona (front map).

The Roman Imperial coinage

The Augustan Age also witnessed new developments in the creation of a stable and abundant coinage that served ever-expanding fiscal and economic needs both within the Empire and far beyond its frontiers. Before Actium, the coinages of Italy and the Roman world had been in a confused and unreliable state as a result of inflation and disruption caused by war and civil strife. The huge amounts of gold and silver available to Augustus after his victory at Actium allowed him to reestablish the credibility of Roman coinage and issue an adequate supply from various mints. His principal gold coin, the denarius aureus, was virtually pure gold and was struck at a weight of forty to the Roman pound. It is usually known simply as the aureus to distinguish it from the more common denarius of silver, denarius argentarius. Augustus’ silver denarius was 97.5 to 98 percent silver and was struck at eighty-four to the Roman pound (p. 115). Twenty-five silver denarii equaled one aureus. Each coin had its respective half, called a quinarius. The constant acquisition of more gold and silver through booty, mining, and trade allowed Augustus and most of his successors to maintain similar standards for almost 200 years. Civic and provincial coins were still produced, particularly in the East. All, however, were linked to the Roman denarius, which provided the standard of value.

Sometime after 23 b.c.e. (19 b.c.e.?), Augustus reopened the mint at Rome and instituted a college of three moneyers (tresviri monetales), officials who minted coins at the joint direction of the princeps and the senate. At that time, Augustus introduced a new series of token coins designed to meet the need for small denominations in daily transactions. He issued a sestertius (one-quarter of a silver denarius) and its half, the dupondius. They were minted in orichalcum, brass made of 75 percent copper, 20 percent zinc, and 5 percent tin. Pure copper went into the as (one-quarter of a sestertius) and the quarter as, called a quadrans. Although these coins were not intrinsically worth their official values, they were so well made and useful that they gained universal acceptance.

The Augustan coinage had an important propaganda or publicity value in addition to its purely economic function. It provided the newborn regime a flexible, subtle, and compelling method of influencing those who used it, particularly soldiers. They received enormous quantities of coins as pay and spent them all over the Empire. People would use and inevitably look at the coins, which could vaguely, yet effectively, suggest what the government wanted them to feel and believe. New coin types, appearing as frequently as modern commemorative stamps, kept the exalted figure of Augustus before the public eye in many forms.

As media of publicity and mass propaganda, the coins were more effective and malleable than the monumental arts. Even the most wonderful works of architecture and sculpture could not keep pace with new messages. Moreover, comparatively few of the Empire’s 50 million to 70 million inhabitants ever saw the major monuments, whereas people everywhere daily used and handled the coins. Moreover, coins could depict monuments. Words on coins were also better vehicles than literary texts for advertising rapidly changing purposes, policies, and resolves of the government. Texts could not be reproduced and disseminated in great numbers so quickly as coins.

Architecture and art

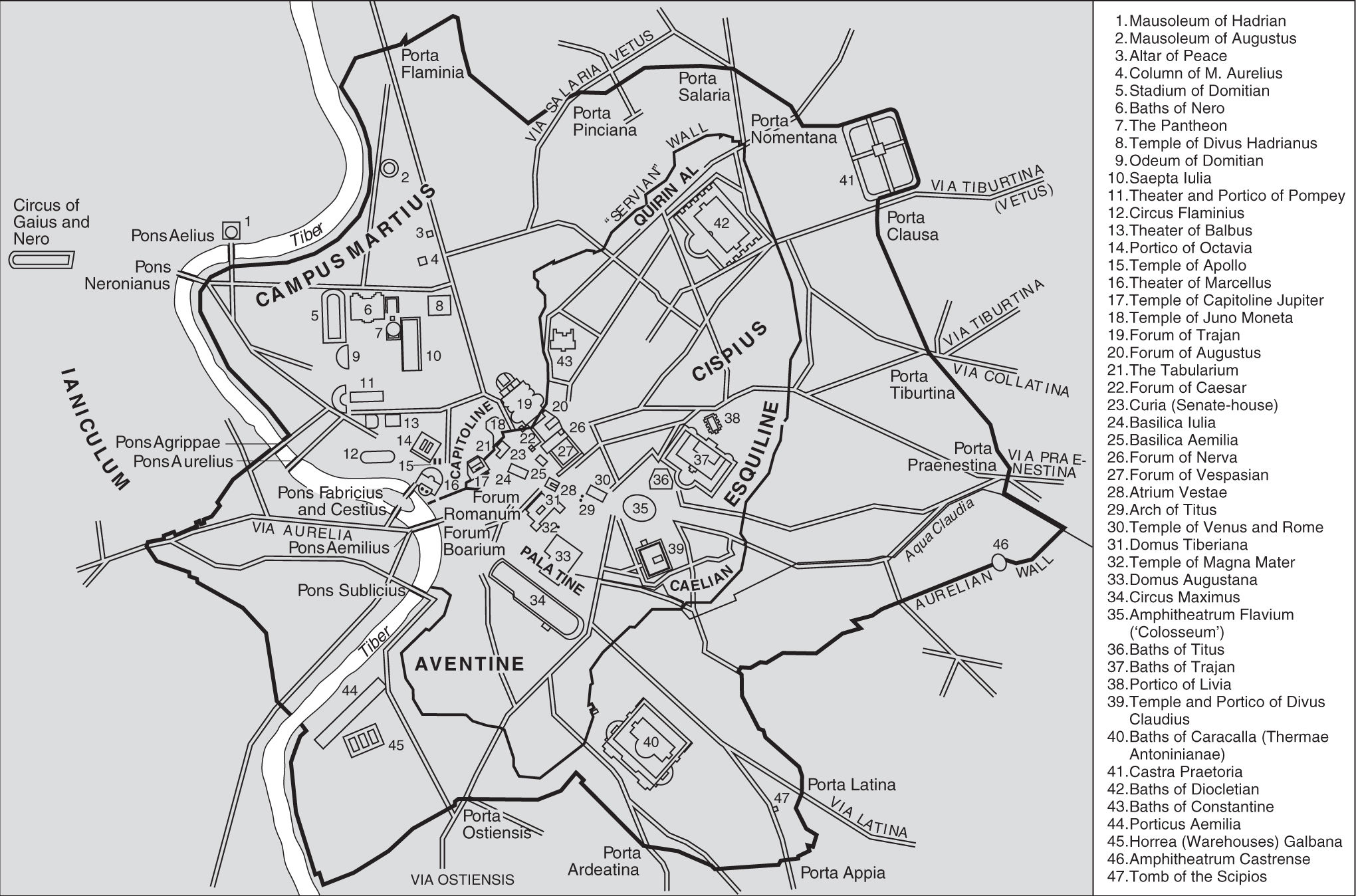

First as Octavian, then as Augustus, the heir of Julius Caesar had an enormous influence on Roman art and architecture. He fostered the ultimate synthesis of Italic, Etruscan, and Greek traditions into an imperial style of Roman Classicism that was widely imitated in the provinces. At Rome, Augustus’ refurbishment of eighty-two temples was a visible expression of his claim to have restored the Res Publica (p. 359). In addition, both Augustus and his faithful general and son-in-law, Marcus Agrippa, enhanced the city with useful public works, beautiful monuments, and magnificent new temples to earn gratitude from the populace and reinforce the themes and values that Augustus promoted. For buildings discussed below, see the plan of Rome on the facing page.

Next to Caesar’s Forum Julium (map, p. 390), Augustus built the even more magnificent Forum Augustum, dedicated in 2 b.c.e. as a visible reminder of the pious vengeance that he had taken on Caesar’s assassins. At the northeastern end, a great temple of Mars Ultor (Mars the Avenger) rose up on a high podium in the Italo-Etruscan manner. It had eight columns across the front, the same number as the Parthenon in Athens, but of the Corinthian, not the Doric, order. On the forum’s long sides were parallel covered colonnades with semicircular projections, hemicycles, off the back at the ends near the temple. They linked the whole into a symmetrical Hellenistic complex. The colonnades and hemicycles displayed statues of republican heroes on one side and the men of the Julian gens on the other. Uniting the two, a large statue of Augustus himself stood in the center of the space in front of the temple.

In 28 b.c.e., Augustus commissioned Rome’s first great building to be constructed entirely of gleaming white Luna (Carrara) marble, a temple to Apollo that sat next to his house (the Domus Augustus) on the Palatine. Augustus attributed his victory at Actium to Apollo’s favor. This temple further linked Augustus and Apollo through their roles as patrons of the arts. Augustus attached two libraries, one Latin and one Greek, to the temple’s precinct. Filled with Classical Greek sculpture and the busts of famous poets and orators, they also functioned as museums. Next to the temple, Augustus and Livia each maintained a relatively simple, republican-style home decorated with beautiful frescoes, some of which still survive, similar to those from the same period at Pompeii.

FIGURE 21.2 Imperial Rome.

Under Augustus, the Forum Romanum acquired the appearance that marked it for centuries. He completed the Curia Julia, Caesar’s new senate house (map, p. 390) and furnished it with a statue and altar of Victory that stood for centuries as assurances of Rome’s imperial sway. He rebuilt the Basilica Aemilia after a fire in 14 b.c.e. Reconstruction after a fire also enabled him to enlarge the Basilica Julia. To the northwest of the latter, the old temples of Concord and Saturn were remodeled in the imperial style. Close to those temples, he expanded the rostra (speakers’ platform) recently built by Caesar. At the southeast end of the Forum, he erected a triple arch and the adjacent temple of his deified adoptive father, Divus Julius. The arch displayed the inscription now called the Capitoline Fasti (p. 76), and the façade of the temple portrayed three generations of Augustus’ family.

FIGURE 21.3 La Maison Carrée at Nîmes, one of the most beautiful surviving Roman temples. It seems to have been erected in the early first century c.e. to commemorate Augustus’ deceased adopted sons Gaius and Lucius.

FIGURE 21.4 Pont du Gard, Nîmes.

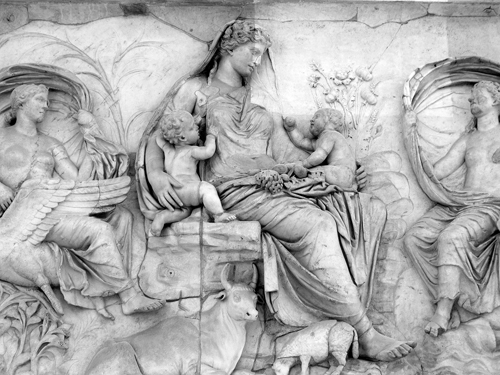

FIGURE 21.5 Sculptured relief from the Ara Pacis, with goddess and babies flanked by the East and West Winds and surrounded by symbols of peace and prosperity.

Augustus built many monuments in the Campus Martius. At its northern limit, he placed his own imposing mausoleum (map, p. 390). Shaped like a mounded Etruscan tomb, it served the emperors and their families from the death of Octavia’s son Marcellus in 23 b.c.e. to that of Emperor Nerva in 98 c.e. A little to the south, Augustus’ architects marked out a huge sundial, the Horologium, in the pavement. A large obelisk, part of the spoils from his victory over Antonius and Cleopatra at Alexandria, formed the pointer. On Augustus’ birthday, to remind people of the peace achieved by his victory, the obelisk’s shadow aligned northeastward to intersect with the magnificent, new Altar of Augustan Peace (Ara Pacis Augustae).

The center of the Campus Martius contained benefactions by Agrippa: the original Pantheon (“Shrine of All the Gods”), a public park with a lake, and Rome’s first major public baths. Other men, eager to be associated with the new era of peace and prosperity, also built impressive public buildings on the southern end of the Campus. Augustus himself built a theater in memory of Marcellus, much of which still stands (map, p. 390).

The Augustan peace fostered much similar building activity in Italian and provincial cities and towns. Examples abound in Gaul: the famous Roman temple at Nîmes (Nemausus), the so-called Maison Carrée (below, Figure 21.3); possibly the lofty Pont du Gard, which carried traffic and water to Nîmes on three tiers of majestic arches 160 feet above the river Gard (p. 392, Figure 21.4); and at Orange (Arausio), a triumphal arch and an immense theater, whose colonnade and central niche housed a colossal statue of Augustus.

The serene and idealized realism of Attic Greek Classicism from the Golden Age of Pericles in the fifth century b.c.e. marked the Augustan style in art. It underscored the arrival of a new Golden Age under Augustus. It is epitomized by the reliefs sculpted on the Ara Pacis (above, Figure 21.5) and by the impressive statue of Augustus set up at Livia’s villa near Prima Porta (p. 393, Figure 21.6). The upper panels on two solid sides of the screen around the altar itself depict Augustus’ family reverently taking part in a stately procession: perhaps the supplicatio (public thanksgiving) of 13 b.c.e., when the senate authorized the altar; perhaps the dedication of the altar in 9 b.c.e. The short upper panels flanking the entrances on the east and west sides portray the blessings and activities of peace: fruit, grain, cattle, a fecund young matron with two healthy babies, and the offering of a sacrifice. Augustus’ statue from Prima Porta depicts a self-possessed and mature, yet youthful, commander in full parade dress. Reliefs carved on his cuirass show the Parthian king handing over to Tiberius the legionary standards that Crassus lost in 53 b.c.e., the final conquest of Spain and Gaul, the fertility of Mother Earth, and Jupiter’s protective mantle over all. These monuments all advertise that peace and honor had been restored under the capable and pious leadership of Augustus and his family.

FIGURE 21.6 Statue of Augustus Imperator with sculptured breastplate (ca. 20 b.c.e.), from the Villa of Livia at Prima Porta.

Similar, if not identical, ideas are conveyed in the same style by a marble altar from Roman Carthage with Roma seated on a heap of arms and contemplating an altar with a horn of plenty (cornucopiae), staff of peace (caduceus), and globe (orbis terrarum) resting upon it; by the exquisite Vienna cameo (Gemma Augustea) and the Grand Camée de France showing respectively a triumph of Tiberius and the ascension of Augustus into Heaven; by two silver cups from Boscoreale that portray the submission of the Germanic Sugambri to Augustus and Tiberius; and by a silver dish from Aquileia, which depicts the emperor surrounded by the four seasons and all the symbols of the fertility, plenty, and prosperity of the new Golden Age.

Literature

The Augustan Age has often been called the Golden Age of Latin Literature. Already the political capital of the Mediterranean world, Rome was rapidly becoming the cultural center, attracting students, scholars, and writers from abroad. It offered themes for literary praise: a heroic past and a great and glorious present.

In the judgment of later generations, Roman writers acquired perfection in form and expression during the Principate of Augustus. Many writers and thinkers were also truly grateful that Augustus had brought an end to destructive civil war. They liked the policies that he designed to preserve the hard-won peace. Many of them were supported by Augustus himself or his close friend Gaius Cilnius Maecenas, a wealthy equestrian of Etruscan descent.

Unlike the age of Caesar, in which prose writers predominated (Cicero, Caesar, Sallust, Nepos, and Varro), the Augustan Age was notable for its poets (Vergil, Horace, Tibullus, Propertius, and Ovid). It was essentially an age of poetry. Even Livy’s great history of Rome, Ab Urbe Condita, was no exception, for some critics have regarded it as an epic in prose form. Livy began where the Aeneid of Vergil left off.

Vergil (70 to 19 b.c.e.)

Publius Vergilius Maro, son of a well-to-do northern Italian farmer near Mantua, gave up a career in the courts to study philosophy with Siro the Epicurean at Naples. After Siro’s death, he turned to poetry. In 38 or 37 b.c.e., he published his Eclogues (Bucolics), ten short pastoral poems in the style of the Hellenistic Greek poet Theocritus, poems idealizing country life and the loves and sorrows of shepherds. They were, however, more than pretty pastorals. The first and the ninth refer to the dispossession of small farmers to settle Octavian’s veterans after Philippi. Both the fifth and ninth refer to the deification of Julius Caesar, while the fourth predicts the return of the Golden Age with the birth of a child. The sixth, reminiscent of Lucretius, expounds Epicurean philosophy, and the tenth is a tribute to fellow poet Cornelius Gallus (p. 396).

The Eclogues had brought Vergil to the attention of Maecenas. With Maecenas’ support, Vergil began, and by 29 b.c.e. had completed, the four books of his Georgics. It is ostensibly a didactic poem on farming like the early Greek poet Hesiod’s Works and Days. More than that, it is a hymn of praise to Italy’s soil and sturdy farmers and to Augustus for restoring the peace so essential for prosperous agriculture and human happiness. As Augustus was returning to Rome from the east after the battle of Actium, he paused to rest a few days at the town of Atella. For his entertainment, Vergil read the Georgics to him.

After completing the Georgics, Vergil spent the next decade in writing his greatest work, the Aeneid. It is a national epic poem in twelve books. The first six correspond to Homer’s Odyssey, the last six to the Iliad. The Aeneid begins the story of Rome with the burning of Troy and the legendary journey of the hero Aeneas to Latium. There, according to Vergil, it was fated that Rome would rise to become a great world empire and fulfill its glorious destiny under Augustus. Although Aeneas, the legendary ancestor of the Julian family, is nominally the hero, the real hero is Rome: its mission is to rule the world, to teach the nations the way of peace, to spare the vanquished, and to subdue the proud (Book 6.851–3). The fulfillment of this mission requires of all Roman heroes the virtues that made Rome great: courage, pietas (devotion to duty), constancy, and faithfulness. Vergil’s emphasis upon these virtues was in line with the Augustan reformation of morals and the revival of ancient faith (prisca fides).

In contrast, Vergil, like Lucretius before him, condemns the lust (cupido) and blind emotion (furor) that he sees as the causes of prior civil strife. Those are the destructive forces that hinder Aeneas and the Trojans from fulfilling the glorious destiny decreed for Rome by Jupiter and that the virtuous hero Aeneas must overcome. Unfortunately, Vergil often portrays these evil forces in feminine terms, which help perpetuate the negative stereotype of women in Western literature.

On his deathbed, Vergil requested the burning of the Aeneid. He considered it not yet perfected. Augustus countermanded that request and ordered it published.

Horace (65 to 8 b.c.e.)

Another great poet of the age was Quintus Horatius Flaccus, son of a well-to-do freedman of Venusia in Apulia. His father sent him to school in Rome and later to higher studies at Athens. There, Horace met the conservative noble Brutus and fought for the Republic at Philippi. Afterward, penniless, he returned to Rome and got a job in a quaestor’s office. Though boring, it gave him the time and means to write poetry.

By 35 b.c.e., he had composed some of his Epodes, bitter, pessimistic little poems in iambic meter (in imitation of the Greek poet Archilochus), and the first book of his Satires. He called his satires Sermones (informal “conversations”). They poke fun at the vices and follies of the capital. Despite being caustic, sometimes vulgar, and even obscene, Horace’s early poems had enough style, wit, and cleverness to win the admiration of Vergil. He introduced Horace to Maecenas in 38 b.c.e. At first, Maecenas provided Horace an independent income and then, in 33 b.c.e., a sizable estate in the Sabine country near modern Tivoli.

In 30 b.c.e., Horace published his second book of Satires. There, he is more mellow and less caustic than in the first. Meanwhile, he had already begun, and for seven years thereafter continued to work on, his Odes (Carmina). The first three books appeared in 23 b.c.e. They comprised eighty-eight poems of varying lengths and meters. Horace derived most of the meters from Greek poets and adapted them to Roman lyric form.

Horace’s fame rests chiefly on the Odes. He called them a monument “more durable than brass and loftier than the pyramids of Egyptian kings” (Odes 3.30.1–2). They touch, often lightly, on many subjects. That variety adds yet another charm to their artistry, compactness, pure diction, fastidious taste, and lightness. Some are so-called wisdom poems containing moral exhortations that he himself took seriously: “Be wise, pour out the wine, cut back long hope to suit a short time. While we are talking, envious time will have fled; seize the day [carpe diem]; trust tomorrow as little as possible” (Odes 1.11.6–8). Others discourse on friendship, the brevity of life, religion and philosophy, drinking wine, and making love, which for Horace was a lightly comic pastime, not an all-consuming passion as for Catullus. The long, more solemn, so-called Roman Odes (Odes 3.1–6) praise the virtues advocated by Augustus: moderation and frugality, valor and patriotism, justice, piety, and faith. In later years, Horace wrote two books of Epistles. They are sermons on morals, religion, and philosophy rather than real letters like Cicero’s. The longest and most famous of these letters, the so-called Art of Poetry (Ars Poetica), sets forth the principles for writing poetry, especially tragedy. From it, Alexander Pope in the eighteenth century drew many of the principles versified in his Essay on Criticism.

The Latin elegists

The elegiac couplet consisting of a dactylic-hexameter line alternating with a pentameter had served in Greek and Latin literature a variety of purposes—drinking songs, patriotic and political poems, dirges, laments, epitaphs, votive dedications, epigrams, and love poetry. Following the innovations of Catullus (pp. 338–9), the first Roman to use the elegy extensively for love poetry was probably Gaius Cornelius Gallus (ca. 69–26 b.c.e.), who also served as governor of Egypt until he ran afoul of Augustus. His four books of Amores firmly established the subjective erotic elegy and were very popular among his contemporaries. Alas, until 1978, none of Gallus’ poems was known to exist. Then, a piece of papyrus that contained one complete four-line poem and most of a second was discovered in Egypt.

Of Albius Tibullus (55–48 to 19 b.c.e.) little is known except that he belonged to the circle of poets around Marcus Valerius Messalla Corvinus, not only a member of the old nobility (p. 348) but also a literary patron and historian. Four books of poems appear under Tibullus’ name in surviving manuscripts. Only two books, comprising sixteen elegies, are certainly his. Several of those elegies are addressed to Delia and to Nemesis—two fatal attractions. They alternately made him ecstatic and heartbroken but never prevented him from writing smooth, clear, and elegant verses.

Sulpicia (born ca. 50 b.c.e.) is the only woman whose poetry has survived from the Augustan Age. She was another member of Messalla’s circle. Her six heartfelt poems to a lover named Cerinthus are included in the manuscripts of Tibullus. They show both her originality as a poet and her mastery of poetic forms normally associated with men.

Sextus Propertius (54–47 to ca. 15 b.c.e.) was another poet who enjoyed the patronage of Maecenas. His four books of elegies include patriotic themes and two poems in praise of Augustus, but he was never fully committed to the Augustan program. His early poems concentrate on his troubled relationship with a woman whom he calls Cynthia. Propertius, known for his innovative approach to Latin love elegy, shows great boldness and originality in his imagery, but obscure allusions and abrupt shifts in thought often make him difficult to understand.

Ovid (43 b.c.e. to 17–18 c.e.)

The most sensual and sophisticated of the elegists was Publius Ovidius Naso, Ovid. He came to Rome from Sulmo in the remote mountain region of Samnium. From a well-to-do equestrian family, he initially pursued a career in the courts but eventually devoted himself to poetry. He became the most prolific of the Augustan poets. He was friends with both Tibullus and Propertius, and Messalla helped his early career.

Ovid’s earliest poems are highly polished love elegies, the Amores, in the manner of Tibullus. His Heroides (Heroines) is an original collection of poetic letters in which famous legendary women address their absent husbands or lovers. Two of his most famous works are the Metamorphoses (Transformations) and the Fasti (Calendar). The first is his only surviving work in epic meter; the second, like all the rest, is in elegiacs. The Metamorphoses provides much information about Greek mythology and has been the source of inspiration to countless poets, playwrights, novelists, and artists ever since. More than that, however, the Metamorphoses is an epic history of the world that culminates patriotically in the change of Julius Caesar from a man to a god. The Fasti was intended to describe the astronomical, historical, and religious events associated with each month of the year, one book per month. It nicely complemented Augustus’ attempt to revive the many priesthoods and religious observances that had fallen into disuse. Unfortunately, the work is unfinished and covers only the first six months.

While the Fasti is compatible with Augustus’ revival of defunct priesthoods and religious traditions, Ovid’s Ars Amatoria (Art of Love) completely contradicts the moral reform that Augustus promoted. It is a salacious handbook, playfully didactic, that explains the arts of seduction and surveys all the known aspects of heterosexual experience, including rape to incest. Ovid attracted the attention of Augustus’ fast-living granddaughter, Julia. For the details are unknown (although scholars have enjoyed speculating), Julia and Ovid were caught up in scandal and banished by the emperor.

Ovid spent the rest of his life at Tomi, a desolate place on the Black Sea near the mouth of the Danube. His last two books of poetry, the Tristia (Sorrows) and Epistulae ex Ponto (Epistles from Pontus), were written there. They are fruitless, often pathetic, pleas for permission to return to Rome.

Latin prose writers

The Latin prose writers of the Augustan Age have been less fortunate than the poets. None of the major historical writings has survived intact. Gaius Asinius Pollio (76 b.c.e.–5 c.e.) and the literary patron Marcus Valerius Messalla Corvinus (64 b.c.e.–8 c.e.) each wrote a major first-hand account of the civil wars. Both works are now lost, although the extant Greek writers Plutarch and Appian drew heavily on Pollio. Augustus wrote a valuable, but highly selective account of his own accomplishments (Res Gestae) in a clear and readable style. Much of it survives from Greek and Latin copies that were inscribed on public monuments in various cities of the Empire. The most complete is a large inscription at Ankyra (Ankara) in Turkey, the Monumentum Ankyranum. Augustus also wrote an autobiography, but it is no longer extant.

Livy (59 b.c.e. to 17 c.e.)

Titus Livius, or Livy, the supreme prose writer of the Augustan Age, came from Patavium (Padua) in Cisalpine Gaul. His Ab Urbe Condita (From the Founding of the City) contained 142 books on the history of Rome from its founding to the death of Drusus I in 9 b.c.e. Only Books 1 to 10 (from the legendary landing of Aeneas in Latium to 293 b.c.e.) and Books 21 to 45 (218–167 b.c.e.) are extant. The Periochae, short summaries or epitomes (written probably in the fourth century c.e.) indicate the contents of all the books except 136 and 137. Livy blended the styles of Cicero and Sallust with poetical phraseology and great dramatic skill to record the mighty deeds of earlier Romans as a divinely ordered march to world conquest. He denounced the vices of his own age; he wanted to show that Rome’s rise to greatness had resulted from patriotism and traditional virtues.

Although his work is of great literary merit and reflects the attitudes of many upper-class Romans in Italy at the time, Livy has, from the modern point of view, numerous defects as an historian. He can be faulted, like most other ancient writers of history, for insufficiently critical use of sources, for failure to consult documents that were probably readily available to him, for his ignorance of economics and military tactics, and for failure to interpret primitive institutions in their proper social setting. Nevertheless, Livy succeeded in giving the world a compelling picture of Roman history and character as many Romans wanted to see them. That fact itself is of great significance for the modern historian.

Pompeius Trogus (ca. 50 b.c.e. to ca. 25 c.e.)

A quite different historian was Pompeius Trogus. Livy, writing from a patriotic Roman perspective, was not interested in other people except as enemies whom Rome conquered. Trogus wrote from the perspective of a provincial native, albeit a heavily Romanized one from Narbonese Gaul. Like Cornelius Nepos, he was much more interested in what Romans could learn from non-Romans than in glorifying an idealized Roman past. Out of the forty-four books of his Philippic Histories (Historiae Philippicae), only two focused on Rome. The bulk concentrated on Macedon and the great Hellenistic empires of Macedonian conquerors after Philip and Alexander. Others covered the Near East and Greece to the rise of Macedon. The rest treated Parthia, Spain, and Gaul to the time of Augustus. Unfortunately, the full text with much valuable information is lost, but a condensed version exists in an epitome made by Justin in the second or third century

The impact of Augustus on Latin literature

In a society where writers depend on wealthy or powerful personal patrons, those patrons have a great impact on literary production. Directly, or indirectly through Maecenas, the impact of Augustus was great indeed. That is not to say he dictated what people wrote. Livy, for example, was no hack writing official history for Augustus. He wrote with a genuine patriotism that happened to coincide with Augustus’ own needs and policies. The same can be said for Vergil, Horace, and Propertius, but that is what helped to attract the interest and patronage of Maecenas and Augustus. They in turn enabled the authors to concentrate on writing and ensured a public audience for, and the survival of, their works. Indeed, Augustus personally intervened to secure the publication of the Aeneid against Vergil’s own stated wishes. This situation was not necessarily harmful, but it raises the question of how many talented writers, either through lack of connections or because of incompatible views, failed to find a powerful patron and disappeared.

The poet Cornelius Gallus committed suicide after incurring Augustus’ official displeasure over the way in which he tactlessly publicized his own military accomplishments in Egypt. Gallus’ disgrace, therefore, may help to account for the disappearance of his work except for a few lines (p. 396). Although official disgrace had no such effect on Ovid and his work, it did prevent him from finishing the Fasti and may well have denied the world better works than those bemoaning his exile and begging for release.

Augustus allowed writers a certain amount of political independence. Propertius, for example, often resisted Maecenas’ request for more poems favorable to the princeps. Augustus even joked with Livy about the latter being sympathetic to Pompey. Still, he seems to have become less tolerant as people began to react against the increasing permanence of his new regime. Augustus was safely dead before Livy wrote about the sensitive events after Actium. It may not be coincidental that under Augustus’ successors the summaries of the relevant books in the Periochae (134–142) give those events the shortest shrift of all. More ominously, in 8 or 12 c.e., the works of the rabidly Pompeian historian Titus Labienus were condemned to public burning, and he committed suicide. The books of the outspoken orator Cassius Severus were burned, too, and he was exiled.

Greek writers

Educated men from the Greek-speaking parts of the Empire continued to produce much literature for Greek audiences. Of special note are two who worked in Rome under Augustus. The first is Diodorus Siculus (the Sicilian). He wrote a history of the world in forty books from the earliest days to Caesar’s conquest of Gaul. It is not a particularly distinguished work of history as such. Still, it is useful because it covers not only Greece and Rome but also Egypt, Mesopotamia, India, Scythia, Arabia, and North Africa, about which most ancient authors say little. Moreover, because Diodorus compiled his history from important earlier works now lost, he gives an indication of what they contained.

More important for the history of Rome and Italy is Dionysius of Halicarnassus, who taught Greek rhetoric at Rome from 30 to 8 b.c.e. In twenty books, his Roman Antiquities covered the history of Rome from its founding to the First Punic War. It preserves valuable material from lost Roman annalists and antiquarians on that period, the most poorly documented in Roman history, but the account is skewed by Dionysius’ overarching argument that the Romans were originally Greeks.

Also important was Strabo (64–63 b.c.e. to 25 c.e.), a Greek from Pontus. His forty-seven books of history, exclusive of that covered by Polybius, are unfortunately lost, but his Geography in seventeen books survives. It covers the known world of the time. Although it is not always based on the best available mathematical, astronomical, and geographic research of the day, it presents in readable form much interesting geographical and historical information that would otherwise be lost.

Scholarly and technical writings

Antiquarian scholarship, handbooks, and technical manuals of all types became increasingly popular from Augustus’ time onward. Vitruvius’ De Architectura became the standard handbook for Roman architects and exercised great influence on the Neoclassical architecture of the Renaissance and later Classical revivals. Verrius Flaccus, the tutor of Gaius and Lucius Caesar, compiled the earliest Latin dictionary, De Verborum Significatu, and Marcus Agrippa, who set up a large map of the Roman Empire in the Forum, wrote a detailed explanation of it in his Commentaries, which summarized the results of Greek geographic research and Roman surveying. A few years later, under Tiberius, Aulus Cornelius Celsus compiled an important encyclopedia whose section on medicine still survives as a valuable summary of earlier Greek medical knowledge.

Philology and literary scholarship

The works of Cicero, Vergil, and Horace became classics in their own lifetimes. They inspired a steady stream of philologists who analyzed their language and style and of scholarly commentators who dealt with literary and historical questions raised by their work. For example, Gaius Julius Hyginus supervised Augustus’ great public library on the Palatine and published a famous series of commentaries on Vergil. His work has not survived, but it is the source of much material preserved in the works of later commentators.

Law and jurisprudence

The Augustan Age marks the beginning of the Classical period of Roman jurisprudence, which lasted until the reign of Diocletian. The old republican families of high pedigree and proud public achievement were gradually becoming extinct. New jurisconsults, or jurists, and legal experts from Italian and even provincial towns came to the fore. Many were professional consultants, writers, and teachers of law. Eventually, jurists became salaried officials of the imperial regime.

Responsa

Either Augustus or Tiberius may have first given select jurists the right to give responsa (responses to people seeking their legal opinions) that were reinforced by his own personal authority (ius respondendi ex auctoritate principis). Most praetors and judges respected and accepted these responses but were under no legal obligation to do so. Unauthorized jurists were still free to give responses and magistrates and judges to accept them, but the prestige of those with the ius respondendi made their opinions more widely respected and helped to produce greater uniformity. Official authorization of jurisconsults did not endure beyond the reign of Trajan (98–117 c.e.).

Traditions of jurisprudence

At the end of the Republic and beginning of the Principate, two traditions or schools of jurisprudence emerged. The older is often called Sabinian after the famous jurist Masurius Sabinus. The other tradition originated under Augustus even though it later received the name Proculian during Nero’s reign. Apparently, they did not differ over fundamental questions such as the source or purpose of law but only in its application. The Sabinians tended to follow more particular, less systematic arguments in their legal opinions. The Proculians were willing to advance wider, more logically rigorous arguments but did not challenge existing legal principles and concepts.

The Augustan achievement

Law flourishes only in times of peace. Although Augustus started his career as another self-seeking leader in civil war, he made up for the destructiveness of his early years by earnestly trying to construct a better future for Rome. The restoration of peace and orderly government after Actium and the economic upsurge that followed laid the groundwork for a brilliant efflorescence of art, literature, and scholarship, which Augustus himself did much to inspire and encourage, albeit in ways beneficial to him.

Suggested reading

Galinksy , K. Augustan Culture: An Interpretive Introduction. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1996.

Severy , B. Augustus and the Family at the Birth of the Roman Empire. London: Routledge, 2010.

Zanker , P. The Power of Images in the Age of Augustus. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1990.