Chapter 26

The first two centuries c.e. fully realized the potential created by Augustus’ establishment of widespread peace within the Mediterranean core of the Roman Empire. Rome had become a giant magnet attracting trade and talent from every quarter and radiating its influence in all directions. The writers and artists of the Augustan Golden Age had created a common cultural frame of reference for the Empire’s urbanized upper classes. Those classes shaped a remarkably uniform high imperial culture based on shared values and educational experience. They became an elite of imperial service. They were not bound by the parochial ties of language, tribe, or city, but the universal ideal of Rome as the city. It was the guarantor of civilized urban life against forces of destruction both within and without.

Indeed, the universal rule of Rome encouraged many to reject the old particularistic world of individual cities. Rome became their universal commonwealth. As its citizens, they lived under the care of a benevolent universal deity in the form of either the emperor himself or one of the savior gods popularized by various Eastern mystery cults.

Socially and economically, the Empire reached great heights. With Italy and the interior provinces enjoying unprecedented peace and prosperity and with threats on the frontiers usually contained, foreign and domestic trade flourished. There was enough surplus wealth to support a vigorous tradition of euergetism (the doing of good works). The emperors and the upper classes ameliorated the plight of the poor. Those of moderate means found opportunities for economic and social advancement. At the same time, Stoic and Cynic philosophers popularized an enlightened spirit. That spirit was consonant with at least moderately improved conditions for women and the lower classes and with the integration of provincials as Roman citizens.

Post-Augustan literature

The late Republic and the reign of Augustus had produced a series of major Latin authors, who had used the great works of Greek literature as their models. The latter continued to be the foundation of traditional paideia (the training of youths) in the Greek East. In the West, they were now mediated through the classic Latin writings of Cicero, Caesar, Livy, Vergil, Horace, Propertius, Tibullus, and Ovid. Those authors had enshrined the values and ideals summed up in a later word, Romanitas. They now formed the basis of literary education in the West. Educated western provincials thus absorbed patriotic pride in the glories of Rome’s past and espoused the ideals believed to have accounted for its greatness. As a result, the high culture of the imperial capital became indelibly etched on that of the western provinces.

The Latin language and its literature were also the western provincials’ passport to the wider world of Rome itself and imperial service. Consequently, many of the leading figures in the world of Latin letters in the first two centuries c.e. no longer came from the old Roman aristocracy or from the municipalities of Italy. They sprang from the colonies and municipalities of Gaul, Spain, and North Africa. Such men were a constant source of fresh talent and gave Latin letters greater breadth and popularity than ever before.

The impact of rhetoric and politics

Latin authors of the first and second centuries c.e. often wrote in a highly rhetorical style different from the more restrained Classicism of the first century b.c.e. Rhetoric, the art of persuasive speech, had always been a large component of Greco-Roman education. Effective speaking was essential for success in the public life of Greek city-states and the Roman Republic. Rhetorical skills were needed more than ever in the Roman Empire. The greater number of law courts under the emperors and the greater number of cases generated by the more complex Empire required an army of lawyers trained to be as persuasive as possible. Countless petitions addressed to the emperor and his administrators required writers with rhetorical skill and polish. Emperors, provincial governors, military leaders, and local officials needed to communicate effectively with large audiences.

At the same time, it was politically dangerous to be too independent or original under an all-powerful emperor. He might view independent and original ideas as a threat to his own leadership. Flattery of the emperor and his agents was much safer. Therefore, the persuasive or argumentative declamations, suasoriae and controversiae, of the rhetorical schools became progressively artificial. Rhetoric increasingly concentrated on elaborate and exotic technique for its own sake. Sometimes, the constant striving for effect produced a turgid, twisted, and distorted kind of writing meant only to display one’s verbal virtuosity in competition with others similarly trained. This trend was reinforced by the political need of the emperor and local elites to win popular favor by entertaining mass audiences with spectacles, games, and shows. Literary tastes now ran toward the more theatrical and emotional; the exotic, the grotesque, and the sensational became appealing subjects.

Of course, the idealized past of heroes and statesmen enshrined in many Classical authors was fundamentally incompatible with the autocracy that even the most restrained emperors found hard to mask. As the imperial monarchy became a permanent fixture under the Julio-Claudians, the contradiction between ideals and reality was difficult for some to overlook, particularly for traditionalists in the Roman senatorial class. Therefore, many of the Latin authors from that class during the first two centuries looked back in nostalgia or protest to the lost liberty of the Republic. They took refuge in the teachings of Stoicism symbolized by the great martyr to republican libertas, Cato the Younger. On the other hand, for authors who did not come from that class or were only recent arrivals, sometimes it was easier to overlook the contradiction between ideal and reality. Their writings were deferential to the emperors in whose service they rose to a prominence that they never could have attained under the old Republic.

Poverty of literature under Tiberius and Caligula

The stern and intrigue-ridden reign of Tiberius and Caligula’s frightening suppression of real or imagined rivals stifled creativity and free expression in most fields of literature.

History and handbooks

There were few historians of note under those emperors. Velleius Paterculus (ca. 19 b.c.e.–ca. 32 b.c.e.), an equestrian military officer, wrote a brief history of Rome in a rhetorical style. Its importance is that it reflects the attitudes of his class. It is favorable toward Tiberius, with whom Velleius had served, and displays an unusual interest in Roman cultural history. Aulus Cremutius Cordus (d. 25 c.e.), on the other hand, wrote a traditional history of Rome’s civil wars to at least 18 b.c.e. He reflected the attitudes of Stoic-inspired aristocrats who resented the emperor’s monopoly of power and dignitas. Sejanus had Cordus tried for treason, his books were burned, and he committed suicide (p. 411).

Seneca the Elder—Lucius (or Marcus) Annaeus Seneca (ca. 55 b.c.e.–ca. 40 c.e.)—fared better, although his history of the same period is also lost. That is unfortunate because he came from Corduba in Spain, making him one of western provincials who were becoming prominent in early imperial Rome. What has survived of his writings is a handbook of rhetorical exercises (controversiae and suasoriae) culled from public declamations.

Practical handbooks were safe and popular. One of the most famous produced during Tiberius’ reign was another compilation for use in rhetorical training, the Nine Books of Memorable Deeds and Sayings by Valerius Maximus. M. Gavius Apicius, a famous gourmet, even wrote a popular book on sauces. It is now lost. The extant book of recipes that goes by the name of Apicius is a fourth-century collection.

Poetry

Poetry fared almost as badly as prose under Tiberius, although he himself was a poet in the Alexandrian tradition. Unable, it seems, to reconcile the illusions of the Augustan Principate with its reality, Tiberius did not encourage celebratory, patriotic historical epic in the tradition of Vergil. With his interest in astronomy and astrology, however, he may have appreciated the only surviving pieces by his nephew and adopted son, Germanicus: two large fragments from translations of earlier Greek epics on astronomy and predicting the weather. Another scientific poem survives from this period, the Astronomica of Germanicus’ contemporary Marcus Manilius. It covers the planets, the signs of the zodiac, the calculation of a horoscope, and the influence of the zodiacal signs at various points during their periods of dominance. It is very Stoic in its attempt to find a universal cosmic order.

Phaedrus (ca. 15 b.c.e. to ca. 50 c.e.)

The most interesting surviving author of the period is Gaius Julius Phaedrus or Phaeder. First of all, as a freed Thracian slave of Augustus, he represents a class whose voice is seldom heard in imperial Rome. Second, he introduced a whole new minor genre to Greco-Roman literature, the moralizing poetic fable in the tradition of Aesop. His tales are often thinly disguised criticisms of the powerful in his own day. Sejanus tried to silence him but failed.

The blossoming of the Silver Age in literature under Claudius and Nero

The period from 14 to 138 c.e. is often called the Silver Age in comparison with the Golden Age of Augustus. The Silver Age really blossomed under Claudius and Nero. It then surpassed the early years of Augustus in quantity of writing and, with one major break, in length of sustained activity. Claudius himself was a writer and historian of some accomplishment (p. 421). Ironically, under the influence of Messallina early in his reign, he banished Seneca the Elder’s son, Lucius Annaeus Seneca (the Younger), an accomplished orator and devoted Stoic. This act must have cast a pall over free expression at Rome. In 49, however, at the prompting of Agrippina, Claudius recalled Seneca the Younger to tutor her young son, Nero. From that point until Seneca’s fall from power under an increasingly fearful Nero, there was a great outburst of literary activity, especially among writers from Spain, many connected to Seneca’s family.

Seneca the Younger (ca. 4 b.c.e. to 65 c.e.)

L. Annaeus Seneca, the most noted literary figure of the mid-first century c.e., was born to Seneca the Elder at Corduba, Spain, and came as a boy to Rome. He was one of Rome’s most notable Stoic philosophers and a copious author of varied works: a spiteful burlesque on Claudius (Apocolocyntosis); a long treatise on natural science (Quaestiones Naturales); nine tragedies, typically Euripidean in plot and theme, in a highly rhetorical style; ten essays (misnamed Dialogi), containing a full exposition of Stoic philosophy; prose treatises; and 124 Moral Epistles (Epistulae Morales).

Lucan (39 to 65 c.e.)

Born in Corduba, M. Annaeus Lucanus (Lucan) was Seneca’s nephew. His sole extant work is the De Bello Civili (often called Pharsalia), a violent and pessimistic epic poem in ten books, which narrates the war between Caesar and Pompey. It displays a strong republican bias, a deep hostility toward Caesar, and a rejection of Vergil’s patriotic idealism. Suspected of complicity in Piso’s conspiracy against Nero (pp. 433–4), both Lucan and Seneca the Younger were forced to commit suicide in 65.

Thrasea Paetus and Petronius (? to 66 c.e. for both)

Nero continued his persecution of Stoic critics in 66 by condemning to death Thrasea Paetus (P. Clodius Thrasea Paetus), who wrote a sympathetic biography of Cato the Younger. Others suspected of involvement with him were ordered to commit suicide. One of them was the Petronius whom Tacitus calls the “arbiter of social graces” (elegantiae arbiter) under Nero (p. 434). He is often identified with the Petronius who authored the witty and picaresque satirical novel Satyricon (or Satyrica). It combines humor with serious criticism of the times. In its world, the old Roman values are stood on their heads. Gross materialism and sensuality are the order of the day. Bad rhetoric runs riot. Everyone pretends to be what he is not. Beneath the laughter is the feeling that society has run amok.

Persius (34 to 62 c.e.) and Martial (ca. 40 to 104 c.e.)

Aulus Persius Flaccus and Marcus Valerius Martialis were both satirists who escaped Nero’s purges. Persius may simply have died too soon. His six surviving hexameter poems, the Satires, are highly compressed, rather academic attacks on stereotypic human failings. On the other hand, Martial, a Spaniard from Bilbilis, in the twelve books of his Epigrams, attacks the shams and vices of real people. He was probably too young to attract much notice under Nero. He wrote mostly under the Flavians and eventually returned to Spain.

Curtius (ca. 20 to 80 c.e.)

Significantly, the most well-known historical work from Caligula to the Flavians was the History of Alexander by Quintus Curtius Rufus. It was more of an historical romance than serious history, which would have been dangerous. Curtius merely furthered the romanticized tales that had quickly obscured the real facts of Alexander’s career after his death.

Technical writing and scholarship

Research and writing on technical subjects were still much safer pursuits than poetry or history. For example, the De Re Rustica of Lucius Junius Moderatus Columella (ca. 10–70 c.e.), who came from Gades (Cadiz), is a practical guide for large-scale farmers. The earliest Roman geographical treatise that has survived belongs to Columella’s contemporary and fellow Spaniard Pomponius Mela. Written in the archaizing style of Sallust, his Description of Places (Chorographia) starts at the Straits of Gibraltar, goes counterclockwise around the Mediterranean in three books, and ends up back at Gibraltar. Fantasy sometimes prevails over fact, but it indicates that Rome’s acquisition of a large empire stimulated a desire to learn more about its lands and peoples.

Pliny the Elder, Gaius Plinius Secundus (ca. 23 to 79 c.e.)

Nowhere is the interest in conveying practical technical knowledge better epitomized than in the encyclopedic Natural History (Historia Naturalis) of Pliny the Elder. Pliny’s Stoic-inspired goal was no less than to sum up the existing state of practical and scientific knowledge as a service to mankind. He died in the eruption of Vesuvius while he was combining intellectually curious observation with an attempt to rescue victims. Arranged topically in thirty-seven books, his immense work unscientifically but systematically compiles a vast array of information and misinformation on such subjects as geography, agriculture, anthropology, medicine, zoology, botany, and mineralogy. It is still useful because it preserves an enormous store of information that, correct or not, provides the modern historian with valuable raw material for fresh analysis.

Frontinus (ca. 30 to 104 c.e.)

A more technical and practically informed writer is Pliny’s long-lived contemporary Sextus Julius Frontinus. His compilation of useful military stratagems culled from Greek and Roman history, the Strategemata, has survived. His more theoretical treatment of Greco-Roman warfare has not. Because military officers building camps, roads, and fortifications needed practical information on surveying, he wrote a treatise on that subject, too. Excerpts from it survive in a later compilation of writers known as the Gromatici, named from a Roman surveying instrument called a groma.

In 97, Emperor Nerva appointed Frontinus supervisor of Rome’s water supply. To guide his successors and people dealing with the problems of water supply in other cities, Frontinus published all that he had found useful in his most famous and original work, the De Aquis (De Aquae Ductu) Urbis Romae. In two volumes, it gives an invaluable history of Rome’s aqueducts and priceless technical information derived from personal experience, engineering reports, and public documents.

Artemidorus (late second century c.e.)

A far different kind of writer is Artemidorus, a Greek from Ephesus. He was very much interested in subjects that today would be associated with popular superstition or the occult. His Interpretation of Dreams records and explains dreams collected from people during his extensive travels. It provides a fascinating look at the popular anxieties and psychology of the time.

Science and medicine

Abstract science was not a forte of the Romans. The scientific work that did take place was carried on by the heirs of the Greek tradition in the East. Even they were primarily encyclopedists like Pliny the Elder and did little original work; instead, they tended to codify and compile the work of predecessors. Their summaries then became standard reference works that remained authoritative until the scientific revolution of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.

Ptolemy of Alexandria (mid-second century c.e.)

The most influential scientist of the first two centuries c.e. was the mathematician, astronomer, and geographer Ptolemy, Claudius Ptolemaeus. He expounded the geocentric theory of the universe in a thirteen-volume work known by the title of its Arabic translation, the Almagest. His complex theory of eccentric circles and epicycles to explain the observed motions of heavenly bodies in relation to the earth was mathematically very sophisticated. It dominated Arabic and Western astronomy until the Copernican revolution.

In his geographical writings, Ptolemy accepted the view of the Hellenistic scholar Eratosthenes on the spherical shape of the earth. He constructed a spherical projection with mathematically regular latitudes and longitudes. Ironically, however, he argued for Posidonius’ much shorter circumference of the earth than the more accurate longer one of Eratosthenes. It was the belief in the spherical shape and short circumference of the earth that led Columbus to think that he could get to the Indies relatively quickly by sailing west.

Medical writers before Galen

A number of Greek and Roman physicians kept up the long-established tradition of medical writing. Under Claudius, the Roman Scribonius Largus produced a practical handbook of prescriptions for drugs and remedies that still exists under the title Compositiones. Largus is greatly surpassed, however, by his Greek contemporary Dioscorides Pedianus, who had traveled extensively as an army doctor. Dioscorides has left two works on drugs and remedies that became the standard reference in pharmacology for the rest of antiquity. Under Trajan and Hadrian, Soranus of Ephesus wrote twenty medical treatises in Greek, and many were translated into Latin. Of his surviving works, the most important are his gynecological writings. They provide a rare resource for studying women in relation to ancient medical theory and practice and often reveal male-biased misconceptions of female biology.

Galen (129 to ca. 200 c.e.)

The greatest physician and medical writer of antiquity was the Greek doctor Galen of Pergamum. He started out as a doctor for gladiators in Pergamum. Then he became Marcus Aurelius’ court physician at Rome. He was both a theorist and a practitioner. Equally skilled in diagnosis and prognosis, he always sought to confirm his theories with practical experiments. Indeed, through careful dissection, he greatly advanced the physiological and anatomical knowledge of the day. His writings, now thirty printed volumes, were regarded as so authoritative that medical research in the West largely stagnated for the next thousand years.

Philology and literary scholarship

Philological and literary criticism had begun to grow by the end of the first century b.c.e. It blossomed in the next two centuries as the recognized classics like Cicero, Vergil, Horace, and Ovid became the standard texts for Roman rhetorical education. Cicero’s importance as a school text is seen in the extant commentaries that Asconius Pedianus wrote for his young sons on five speeches of Cicero. Asconius is particularly valuable because two of the speeches on which he wrote, Pro Cornelio and In Toga Candida, are lost. His comments help to reconstruct them.

Helenius Acron and Pomponius Porphyrio wrote school commentaries on Horace at the end of the second and beginning of the third centuries. Acron has been reworked by a later pseudo-Acron, but Porphyrio is intact. Both are indispensable for the study of Horace.

Sometime in the first century c.e., an author variously identified as Dionysius or Longinus (once wrongly identified with Cassius Longinus [p. 538]), wrote one of the most important pieces of literary criticism in the ancient world. Written in Greek and entitled On the Sublime, it is a highly original analysis of what makes a piece of literature great. It gets beyond the usual discussion of rhetoric and style and stresses the need for greatness of mind and feeling.

Lack of great literature under the Flavians, 69 to 96 c.e.

Nero’s purge wiped out a whole generation of Roman writers just as it was reaching its prime. The political situation under the Flavians was not conducive to the emergence of a new one. Vespasian, Titus, and Domitian were not hostile to learning and literature, but they did not encourage the freedom of expression necessary for truly great literature. Vespasian set the tone when he banished the Stoic and Cynic philosophers from Rome and executed Helvidius Priscus (p. 447). Domitian reinforced it with similar banishments in 89 and 95 and ruthlessly employed informers to muzzle his critics (pp. 450–1).

Poetry

Only three poets other than Martial (p. 479) have survived. Silius Italicus (ca. 26–101 c.e.) wrote an uninspired epic, the Punica, in seventeen books on the Punic wars. Valerius Flaccus (?–ca. 90 c.e.) wrote a refined but unoriginal epic, the Argonautica, a rehash of Jason’s expedition to find the Golden Fleece. Publius Papinius Statius (ca. 45–96 c.e.), the most talented of the three, was a professional writer patronized by Domitian. Two epics, the Thebaid, on the quarrel between Oedipus’ sons, and the unfinished Achilleid, on Achilles, are extant. Statius’ best work is the Silvae, thirty-two individual poems, many written to friends on special occasions.

Josephus (b. 37 or 38 c.e.)

The only important historian who published under the Flavians was their Jewish client Flavius Josephus. He was a captured Pharisee who allegedly prophesied that Vespasian would become emperor. He wrote the Jewish War to point out the futility of resisting Rome. Despite his pro-Roman outlook, however, he defended his people’s faith and way of life to the gentiles in his twenty-volume Jewish Antiquities. He also wrote Contra Apionem against the anti-Semitic writings of the Alexandrian Greek Apion and defended his own career in an autobiography. His works all survive in Greek, but he wrote the original version of the Jewish War in Aramaic to reach Mesopotamian Jews.

Quintilian (ca. 33 to ca. 100 c.e.)

The central role of rhetoric in higher education resulted in a comprehensive handbook of rhetorical training by the Spaniard Marcus Fabius Quintilianus. He held Vespasian’s first chair of rhetoric at Rome and tutored Domitian’s heirs. His Institutio Oratoria (Oratorical Education) deals with all of the techniques of rhetoric and has influenced serious study of the subject ever since. It is also a source of important information on many other Greek and Latin authors.

Resurgence of literature under the five “good” emperors

The most important authors who came of age under the Flavians did not begin to publish their works until after the death of Domitian. His autocratic nature and constant fear of conspiracies after 88 made it dangerous to express thoughts openly on many subjects. On the other hand, the more relaxed atmosphere between the five succeeding emperors and the educated senatorial elite was more congenial to many writers.

Tacitus (ca. 55 to 120 c.e.) and Pliny the Younger (ca. 61 to ca. 114 c.e.)

The foremost author was Cornelius Tacitus, whose valuable historical works have been discussed above (p. 438). He also wrote the Dialogue on Orators, observations on earlier orators and how the lack of free institutions in his own day produced mere striving for rhetorical effect instead of real substance in contemporary orators. Nothing underscores Tacitus’ point more clearly than the Panegyric, a speech of the younger Pliny, Gaius Plinius Caecilius Secundus, nephew of Pliny the Elder. It is full of flattery of Trajan and dares to offer advice only indirectly by safely criticizing the dead Domitian. The ten books of his Letters, however, are much better. In smooth, artistic prose, they are addressed to Trajan and numerous other important friends. They reveal an urbane, decent individual. He tried to live up to his responsibilities, avoid injustice, and do good where he could, as in endowing a school for boys and girls or refusing to accept anonymous denunciations of Christians.

Juvenal (ca. 55 to ca. 130 c.e.)

Little is known about Juvenal (Decimus Junius Juvenalis), who published he published sixteen Satires during the reigns of Trajan and Hadrian. They are vitriolic, misogynistic, and otherwise offensive attacks on vices and their practitioners. Juvenal was immensely popular in the Middle Ages because he titillated Christian moralists while confirming their view of pagan Roman decadence.

Suetonius (ca. 69 to ca. 135 c.e.)

Another writer who fascinated medieval Christians in the same way was Gaius Suetonius Tranquillus. He is often considered the last author of Latin’s Silver Age. Friend of Pliny the Younger, he served Trajan and became Hadrian’s private secretary and imperial librarian. He wrote on textual criticism, famous courtesans, illustrious men, literary figures, Greek and Roman games, and a variety of other topics. Nevertheless, most of those works are lost. His fame rests upon his major biographical work, the Lives of the Twelve Caesars (Julius Caesar to Domitian). These biographies, however, aim not so much at serious scholarship as at entertainment. Suetonius does preserve much valuable information from lost earlier sources, but his portraits must be treated cautiously. Rumor, gossip, and rhetorically embellished scandal are often included.

Fronto (ca. 100 to ca. 170 c.e.) and a new literary movement

Suetonius’ fascination with the bizarre actions of past emperors and his research on obscure topics was symptomatic of his age. A general absorption in arcane and antiquarian subjects became a definite literary movement, almost a cult of antiquity, under the Antonines (Antoninus Pius through Commodus). A man who fostered this movement was Marcus Aurelius’ tutor in rhetoric, M. Cornelius Fronto. Significantly, Fronto had been born at Cirta in North Africa, which soon replaced Spain as a provincial source of Roman writers.

Fronto’s major interest lay in ransacking early Latin literature for archaic and uncommon words. He and his literary circle wanted to expand the rather limited vocabulary of the Classical writers like Cicero and Vergil. Fronto and his friends created what he called an elocutio novella (new elocution) to give greater point and variety to their expression.

Aulus Gellius (ca. 125 to ca. 175 c.e.)

The danger in Fronto’s approach was that arcane archaisms and recondite research would become ends in themselves and irrelevant to the real world. A case in point is Fronto’s cultured friend Aulus Gellius. Beginning as a student in Athens, he compiled interesting oddities culled from earlier writers and interspersed with accounts of conversations on a wide range of philological and antiquarian subjects. Called Attic Nights (Noctes Atticae) in honor of its origin, it is a valuable work to modern scholars because it preserves much important information from now-lost earlier works.

Apuleius (ca. 123 to ca. 180 c.e.)

Apuleius was a professional rhetorician and popular Middle Platonist philosopher in Roman Carthage. He published excerpts from his declamations in the Florida. In the encyclopedic spirit of the age, he also wrote widely on various subjects in such books as Natural Questions, On Fish, On Trees, Astronomical Phenomena, Arithmetica, and On Proverbs. Although he was inclined to show off, his interests were serious, as seen from his declamation Concerning the God of Socrates. His investigations into magic and theurgy eventually led to his prosecution for practicing forbidden magic after he married a wealthy older widow. That led to his two greatest works, the Apology, based on his successful self-defense in court, and the Metamorphoses (or Golden Ass), the only complete Latin novel to have survived.

In the novel, a certain Lucius is the victim of his own experiments in sex and magic. They turn him into an ass with human senses who suffers numerous comical and bawdy mishaps. Apuleius, however, has interspersed many additional elements from other stories to give it greater depth and to ridicule the magic and superstition of the age. In contrast, many argue, Apuleius describes the true power of pure faith in the saving grace of the goddess Isis through a moving scene of conversion at the end. To others, however, the ending may be a rather sexist spoof, another instance of Lucius’ misplaced trust in a female who has all the answers.

Pausanias (fl. 150 c.e.)

The peace and prosperity of the first two centuries c.e. and the antiquarianism of the age encouraged travel and the viewing of historical places, monuments, and museums. Therefore, travelogues and guidebooks were in great demand. Fortunately, one of the most valuable survives, the Description of Greece by Pausanias. He was a Greek geographer from Lydia in the mid-second century. Usually, he outlines the history and topography of cities and their surroundings and frequently includes information on their mythological lore, religious customs, social life, and native products. Pausanias is particularly interested in historic battle sites, patriotic monuments, and famous works of art and architecture. The accuracy of his descriptions has been very helpful in locating ancient sites and reconstructing what has been recovered.

Resurgence of Greek literature

It is significant that Pausanias was a Greek writer describing great monuments and locales in ancient Greece. The first two centuries c.e. saw a renewal of cultural activity and local pride in the Greek-speaking half of the Roman Empire. Greeks could reflect with pride that upper-class Romans continued to flock to the great Greek centers of culture to complete their education just as they had done during the late Republic. The vigorous philhellenism of emperors like Nero, Hadrian, and Marcus Aurelius recalled a sense of greatness to many Greeks. The return of prosperity to Greek cities under the imperial peace and the growing prominence of influential Greeks in imperial administration must have reinforced it. In fact, many significant Greek writers during this period were men who had successful careers in the Roman government.

Plutarch (ca. 45 to 120 c.e.)

An outstanding example of such a person is Plutarch (L.[?] Mestrius Plutarchus) of Chaeronea in Boeotia. Under Hadrian, Plutarch was procurator of Achaea. A large collection of miscellaneous ethical, rhetorical, and antiquarian essays (not all genuinely Plutarch’s) is entitled Moralia. Plutarch’s most famous work is the Parallel Lives of Noble Greeks and Romans. The overall theme of the Lives is that for every important figure of Roman history, a similar and equally important character appears in Greek history. Plutarch hoped to show that the Greeks were worthy partners of Rome in the great task of maintaining the Empire. Plutarch chose his material to highlight moral character, not present an objective or critical historical analysis.

Arrian (ca. 95 to 180 c.e.)

Another Greek writer who had served Rome was L. Flavius Arrianus, Arrian, from Nicomedia in Bithynia. Also a Roman citizen, he became a suffect consul in the early years of Hadrian and was governor of Cappadocia from 131 to 137. Retiring to the cultured life of Greece, he studied philosophy under Epictetus (p. 489). He presented a full account of Epictetus’ Stoic teachings in his Diatribes (Discourses) and a synopsis in the Enchiridion (Handbook).

Of Arrian’s extant historical works, the most important is his account of Alexander’s war against Persia, the Anabasis of Alexander. It is the fullest and most soundly based account of Alexander that has survived. The loss of his After Alexander makes it much more difficult to reconstruct the history of Alexander’s successors.

Appian (ca. 90 to 165 c.e.)

Appianus (Appian), a Greek from Alexandria and Arrian’s contemporary, also obtained Roman citizenship. After a successful career at Rome, he wrote a universal history in Greek like Polybius’ earlier work. His universal Roman History (Romaika) in twenty-four books began with the rise of Rome in Italy and then treated various ethnic groups and nations conquered by Rome. Books 13 to 17, however, form an interlude entitled Civil Wars on the period from the Gracchi to Actium. Appian often followed valuable, now-lost Greek and Latin sources.

Lucian (ca. 115 to ca. 185 c.e.)

The most original writer of this period was Lucian (Lucianus). He was a Hellenized Syrian from Samosata, who held a Roman administrative post in Egypt. He was a master of Classical Attic Greek and was deeply versed in its literature. Lucian’s earlier works consist of rhetorical declamations and literary criticism, often laced with wit. Contrary to some claims, however, Lucian is probably not the author of a satirical novel entitled Lucius (or The Ass), based on the same original as Apuleius’ Golden Ass. His most famous works are humorous, semipopular philosophical dialogues, such as his Dialogues of the Dead. They deflate human pride, pedantic philosophers, religious charlatans, and popular superstitions. He vigorously disliked all that was fatuous, foolish, or false.

The Second Sophistic

Lucian’s interests and the range of his writings are too broad to be categorized easily. They must be seen in the context of a Greek literary movement known as the Second Sophistic. The Greek sophists of the fifth and fourth centuries b.c.e. had invented formal rhetoric. Hence, the professional rhetoricians of the second and third centuries c.e. were also called sophists. Many of them sought to revive the vocabulary and style of earlier Greek orators. Most of them were wealthy, cultured men proud of the Greek past and eager to promote the influence of their native cities within the Roman Empire. In their society, they were as popular and influential as modern celebrities. They cultivated relations with Roman aristocrats and were often favored by emperors. Their archaizing tendencies influenced Fronto. His elocutio novella represents a parallel movement in Latin.

A leading figure of the Second Sophistic was Aelius Aristides (ca. 120–189 c.e.). He delivered lectures and ceremonial speeches all over the Empire. There are fifty extant works ascribed to Aristides. In his panegyric address To Rome, he gives heartfelt thanks and praise for the peace and unity that Rome had brought to the Mediterranean world so that it had become, in effect, one city. His Sacred Discourses records dreams that he attributed to the healing god Asclepius. It provides a valuable look at practices associated with the cult of Asclepius (see Box 26.1) and the religious experience of an educated pagan.

26.1 Incubation cults

The Romans frequently sought aid or advice from their gods through prayers, offerings, and sacrifices. The gods often responded, sometimes through signs in the natural world (like lightning strikes or flooding rivers) and sometimes through direct appearances. Gods were thought to reveal themselves to mortals both in broad daylight and at night in dreams. While dream-epiphanies could happen no matter where the worshiper slept, sanctuaries belonging to certain gods, Asclepius most famous among them, offered a service called incubation (from the Latin incubare, “to lie in”) where the worshiper could, after offering prayers and making a request, spend the night at the temple in hopes that the god would deliver advice or, in the case of Asclepius who specialized in medical matters, a cure in a dream. Inscriptions from numerous cult sites around the Roman world reveal that sometimes Asclepius would perform a medical procedure (even surgery) in the dream, and the worshiper would wake up cured. Other times, he would speak to the dreamer, delivering a prescription or a regimen of diet and exercise to be followed upon waking.

Dio Chrysostom (ca. 40 to ca. 115 c.e.)

The best representatives of the Second Sophistic were popular philosophical lecturers who earnestly communicated moral lessons to a wide audience. The most noteworthy is Dio Chrysostom (Golden-mouthed) from Prusa in Bithynia. His message was a mild blend of Stoicism and Cynicism that stressed honesty and simple virtues.

Christian writers

Chrysostom traveled the Empire and propagated what he believed were the best values of his civilization. Others were spreading a new religion. Although they and Chrysostom shared the values of their common Greco-Roman heritage, they would eventually transform that heritage into something quite different. Their best-known works are the four canonical Gospels ascribed to Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John and the missionary letters either written by the Apostle Paul or ascribed to him. They make up the bulk of the Christian New Testament. The Gospel writers sought to preserve the memory and message of Christ’s life and teachings as they understood them. The Pauline letters form the intellectual foundation of much basic Christian theology.

Yet there were many other notable Christian writers. The most famous were Ignatius of Antioch (50–107 c.e.), the first great ecclesiastic and the father of Christian orthodoxy; Irenaeus of Lyons (ca. 130–202 c.e.), the powerful advocate of Christian unity, denunciator of heresy, and father of systematic theology; and Tatian “the Assyrian” (ca. 120–172 c.e.). The latter’s Life of Christ, in Syriac, was a harmonized version of the four canonical Gospels. It was read in Syrian churches for almost three centuries. As Christians began to experience persecutions, Christian writers glorified and exalted the martyrs in works called martyrologies to inspire the living. The earliest such martyrology was the account of Polycarp’s martyrdom at Smyrna (Izmir) on the coast of Asia Minor, probably in 155/156.

Philosophy

Hellenistic Greek philosophers like Panaetius and Posidonius had adapted Stoicism to the attitudes and needs of the Romans (pp. 334–5). Stoics, along with the Cynics, were the only philosophers to retain any vigor during the first two centuries c.e. Neither Greek nor Roman practitioners, however, broke any new ground in this period. Their efforts were directed mainly at popularizing and preaching the accepted doctrines of duty, self-control, and virtue as its own reward.

Seneca had expounded on numerous Stoic themes under Claudius and Nero (p. 479). Yet, his essays did not have so wide an impact in their day as the public lectures of his contemporary Gaius Musonius Rufus (ca. 30–ca. 100 c.e.). Rufus suffered banishment twice, first under Nero, after the abortive conspiracy of Piso (p. 433), and again under Vespasian’s crackdown on Stoic opponents (p. 447). Many later Stoics were pupils of Rufus. The most notable was the lame Greek ex-slave Epictetus (55–135 c.e.). He suffered with Rufus under Nero and was banished by Domitian. During his exile, he taught at Nicopolis, across the Adriatic from Italy. He attracted a large following and heavily influenced Marcus Aurelius (p. 469). He did not write anything, but his teachings survive in Arrian’s Enchiridion and Diatribes. He emphasized the benevolence of the Creator and the brotherhood of man. He believed that happiness depends on controlling one’s own will and accepting whatever Divine Providence in its wisdom might require one to endure. These teachings of Epictetus and the Meditations of Marcus Aurelius have significantly influenced later Western ethical thought over many centuries.

General religious trends

Stoicism, however, did not have such a widespread effect on the first and second centuries as did developments in religion. Augustus’ renewal of traditional Roman cults, rituals, and festivals had greatly influenced the religious calendars of many other cities. Throughout the Empire, local cults were assimilated into parallel cults of the Roman pantheon. Thus, Roman paganism took on the appearance of an international religion. Each emperor took his duties as pontifex maximus seriously, and emperor worship grew steadily. Many people kept shrines of the emperor in their houses.

More significant was the impact of a centralized imperial state that increasingly controlled people’s affairs. Individuals sought access to divine powers to achieve some sense of control over their lives and destinies. Oracles, omens, and portents were eagerly sought and studied. Astrology was popular within both the upper and lower classes. Miracle workers who claimed to have access to divine powers found eager followings. Under Nero and the Flavians, for example, the Cappadocian Apollonius of Tyana achieved great popularity as a sage and healer, so much so that Domitian banished him from Rome. After his death, he was worshiped with his own cult for a long time.

Under Antoninus Pius, another popular healer and purveyor of oracles was Alexander of Abonuteichos from Paphlagonia (Bithynia). He established a mystery cult that influenced a number of prominent Romans, including Fronto, the tutor of Marcus Aurelius. It, too, continued to exist after his death.

In a universal empire ruled by a powerful central monarch, the traditional local gods and cults were bound to seem diminished in power or not completely adequate. Moreover, the greater mobility of the population also weakened traditional religious ties among cosmopolitan urban populations. Therefore, gods that could claim some more universal power or appeal became prominent features of popular religion.

Judaism

One such deity who attracted considerable favorable attention in the cities of the early Empire was the god of the Jews. Pompey the Great had inadvertently aided the spread of Judaism to the western provinces in the late Republic (p. 333). There was occasional unwelcome attention from authorities in Rome itself, where foreign cults were often treated with suspicion. Still, Jewish communities grew and even attracted converts before the Jewish revolt from 66 to 70. Those unwilling to convert and undergo circumcision or observe other strictures of the Mosaic Law were called “God fearers.” After 70, the destruction of the Temple, the elimination of the high priesthood, and the forced payment of the Temple tax to the pagan Jupiter Capitolinus permanently alienated many Jews. The disastrous revolts under Trajan and Hadrian resulted in severe restrictions on Judaism. The growth of Christianity (aided, ironically, by the earlier spread of Judaism) made the god of the Hebrew Covenant (Old Testament) more accessible to gentiles through the New Covenant (New Testament). Judaism then became limited largely to those born to it.

Mystery cults

Universalized mystery cults whose initiates received assurances of a better future became very popular. Among them were numerous Dionysiac cults. The initiation procedures of one such cult are vividly portrayed in a series of wall paintings at Pompeii in the Villa of the Mysteries. The cult of Demeter at the Athenian suburb of Eleusis attracted initiates from all over the Empire, one of whom was Emperor Hadrian.

Isis

Alongside traditional Greco-Roman mystery cults, Eastern mystery religions were growing with missionary zeal. The secret nature of their activities and the details of their beliefs (hence the label “mystery cults”) and the complete victory of their Christian rivals later on make information about them sketchy at best. Still, a few basic facts are known. Participants in the cult of Isis and her male counterpart, Serapis, followed a few simple rules of conduct and received promises of happiness in this world, if not the next. Worshippers also gained psychological satisfaction and a sense of community from direct participation in elaborate, emotionally charged rituals.

In 58 b.c.e., the senate had banned the worship of Isis from the city of Rome in the tense political atmosphere surrounding the issue of restoring Ptolemy Auletes to the throne of Egypt (p. 283). Her worshipers must have been back before 28 b.c.e., when Augustus banned Egyptian rites within the pomerium, Rome’s sacred boundary. Tiberius banned the cult of Isis from the whole city in 19 c.e. Caligula, however, finally provided a public temple for her in the Campus Martius, and Domitian piously rebuilt it (p. 440). A major cult that had spread to every corner of the Empire could not be kept out of the center any longer.

Mithraism

Eventually, the Persian god Mithras also became popular in Rome. In Persian Zoroastrianism, Mithras was a god of light and truth. He aided Ahura-Mazda, the power of good, in an eternal struggle with Ahriman, the evil power. Mithras was closely associated with the sun god, an important ally of Ahura-Mazda, and he is sometimes identified as the sun. Among Mithras’ divine accomplishments, the most celebrated was the capture and slaying of a bull. From its body sprang other useful forms of life. This death and birth are a central element in the Mithraic mysteries. The bull connects Mithraism with the zodiac and important astronomical phenomena. The most common type of Mithraic cult statue shows Mithras performing the tauroctony, the slaying of the bull.

In another common representation, perhaps associated with the celebration of his birth on December 25 near the winter solstice, Mithras emerges from a stone sphere or egg. The typical Mithraic temple, Mithraeum, was an artificial subterranean cave that may have symbolized death and the grave from which initiates were reborn to a better life. First, however, initiates had to be initiated with a bath in the blood of a sacrificed bull (the taurobolium) and complete certain ordeals. Among them seems to have been a simulated murder. Mithraism also involved a sacramental meal and imposed a strong moral code.

Archaeological evidence indicates that the Hellenized cult of Mithras found more favor in Ostia, Rome, and parts of the western provinces than in the eastern region where it originated. Restricted almost exclusively to men, the cult emphasized honesty, duty, and heroic valor in the face of evil and danger. It appealed particularly to merchants, skilled artisans, civil servants, soldiers, and sailors. It did not attract much following among either slaves or the elite classes of the Empire. Under the Flavians, Mithraism spread especially among the military camps and outposts along the Rhine and Danube. In the second and third centuries, western soldiers carried it to more scattered locations throughout the Empire.

Each Mithraeum usually represented a small self-governing group of only thirty to seventy-five men. Therefore, the numbers of initiates were always relatively small. Mithraism’s communal nature is seen in the lack of a professional Mithraic priesthood or any large institutional organization. Each initiate had to pass through seven stages or gates to reach the highest level of knowledge and spiritual awareness that would free him from the mundane forces that threatened his soul. Those in the higher stages mentored those below, and those who reached the highest stage became “fathers” who guided the particular group.

Christianity

Christianity combined the appealing characteristics of many mystery religions: a loving, divine savior in Jesus, who overcame the forces of evil and death; a benevolent mother figure in the Virgin Mary; the promise of a blessed future; a sense of belonging to a special community in an era when local values and civic institutions were losing force in the face of a distant central government. In this third aspect, however, Christianity greatly surpassed the rest. The requirements of a strict moral code and, in keeping with its Jewish roots, the rejection of all other gods increased the Christians’ sense of specialness. Furthermore, Christ’s injunction to “love one another” resulted in charitable activities within Christian congregations that increased the feelings of fellowship and communal identity.

Organization and the spread of Christianity

As did other new cults, Christianity spread first to the major urban centers along the trade routes of the Empire. Paul and the earliest missionaries often found their first converts among the local Jews and “God fearers” when they arrived in a new city. That often caused conflict with local Jewish leaders. Such conflict sometimes aroused the hostility of Roman authorities.

During the first century c.e., individual Christian communities established a local system of clergy and leaders—deacons and deaconesses (servants), presbyters (elders), and bishops (overseers)—who ministered to the needs of their congregations, established policies, and regulated activities. Later, missionaries were sent out under the direction of these larger centers and established churches in the smaller surrounding communities. The urban bishops were the ones who coordinated this expansion and naturally came to exercise great influence and authority.

By the end of the second century, the bishops of the major cities were recognized as the heads of whole networks of churches in their regions. Furthermore, because of the strong sense of Christian brotherhood, the bishops and various churches regularly corresponded with each other to provide mutual support in the face of difficulties. In this way, they also ensured that local practices and beliefs conformed to the authoritative accepted teachings of Jesus and his disciples.

It is significant that Jesus’s immediate disciples or the Apostle Paul had founded the earliest Christian churches. These early foundations were seen as direct historical links with the words and deeds of Jesus himself through the apostolic succession of their bishops. Churches founded in the generation after Paul and the disciples naturally looked to the apostolic churches for guidance and authoritative teachings. They wished to confirm that they were proceeding in accordance with the words and spirit of Christ’s teachings, which they considered imperative for obtaining salvation. Therefore, the bishops of the apostolic churches, especially in the four major cities of Rome, Jerusalem, Alexandria, and Antioch, achieved great respect and authority. Often they were able to impose their will on the lesser churches, so that Christianity reached a degree of organizational and doctrinal unity matched by no other religion in the ancient Mediterranean world.

This emerging universal (Catholic) organization was challenged in the mid-second century by the Marcionite Christians, followers of Marcion, the wealthy son of an Eastern bishop. Marcion taught that the stern creator god of the Hebrew Bible (Old Testament) was not the same as the better, merciful god of the New Testament. He rejected the human incarnation of Christ. He saw Jesus as a manifestation of the merciful god in human form, not flesh. Marcion also emphasized an ascetic faith as the path to salvation. Persecution under pagan emperors and Constantine in the third and fourth centuries weakened the Marcionite Christian Church. Marcionites survived, however, for hundreds of years in the East until Manichaeism (pp. 550–1) absorbed many of them.

Diverse appeal of Christianity

Another factor that helped the spread of early Christianity was its openness and appeal to all classes and both sexes. Women were not excluded from or segregated within it. In fact, Paul and the early missionaries never would have succeeded without the heavy financial and moral support of numerous women such as those commemorated in the Book of Acts and the Pauline letters. In the early Church, deacons and deaconesses shared in ministering to the congregations. Moreover, the simple ceremonies and the grace-giving rites of baptism and communion posed no expensive obstacles to the poor. Indeed, Christ’s teachings praised the poor and the humble and made their lot more bearable by encouraging the practice of charity toward them in the present and promising them a better life in the future.

On the other hand, basing Christianity on written works—such as the Jewish Scriptures, the four Gospels, and the sophisticated Pauline letters—gave it an appeal to the educated upper class as well. Converts from this class provided the trained thinkers and writers who established a tradition of Christian apologetics aimed at counteracting popular misconceptions about Christians and official hostility toward them. Justin Martyr, who went from Flavia Neapolis (Nablus) in Palestine to establish a Christian school in Rome, addressed just such a defense of Christianity to Antoninus Pius and Marcus Aurelius.

Persecution of Christians

The Christians needed to defend themselves from attack for two reasons. Their rigid monotheistic rejection of other gods and their refusal to participate in traditional activities with their pagan neighbors were an offense to those around them and bred personal hostility toward them. This hostility was fed by the normal human fear of the unfamiliar. Accordingly, people were quick to blame Christians for all manner of misfortunes that befell them individually or collectively. Frequently, they denounced Christians to Roman officials for their “crimes.” Moreover, Roman authorities had always been suspicious of secret societies and feared that they were plotting against the state. This fear seemed borne out in the Christians’ case. They refused to propitiate the gods who were believed to protect the state and would not perform the required ceremonies before the image of the emperor.

During the first two centuries, most of the persecutions and resultant martyrdoms were the consequences of purely local personal and political tensions. By the beginning of the second century, Christianity had become widespread in the eastern provinces, and local agitation against it was frequent. Pliny the Younger faced such a situation when he was governor of Bithynia-Pontus. Emperor Trajan wrote Pliny that there should be no organized hunt for Christians or acceptance of anonymous accusations. He insisted, however, that those fairly accused and convicted of being Christians be executed unless they renounced their faith and sacrificed to the gods. Hadrian insisted that accusations against Christians had to stand up under strict legal procedures or be dismissed. Although he disliked them, Marcus Aurelius himself did not actively promote the persecution of Christians. Neither did he punish governors who yielded to popular pressure and condemned Christians to torture and death (p. 469). The result of the individual martyrdoms in the first and second centuries was to strengthen the resolve of the faithful and impress thoughtful non-Christians. The latter were often moved to convert by the heroic examples of martyrs.

Roman architecture in the first two centuries c.e.

Architecture was a very creative aspect of Roman imperial culture in the first two centuries c.e. Augustus had used the resources of the state for building projects far more than ever before. His example was followed and enlarged upon by most succeeding emperors during this period. With the resources thus made available, architects found no end of opportunities to use their creative talents.

Imperial palaces

Each emperor had to have his own splendid residence on the Palatine, or at least he had to add to that of his predecessor. Nero, of course, took advantage of the fire of 64 to construct his extravagant Golden House, an architectural achievement of the first order. It covered an area twice as large as that of the Vatican today (p. 432). Vespasian destroyed Nero’s palace and built a smaller one on the Palatine to symbolize the beginning of a new order. Vespasian’s sons, especially Domitian, continued to enlarge this new palace until it, too, became a huge complex, the Domus August[i]ana, that destroyed or buried many older buildings beneath its foundations. Its remains are visible on the Palatine today.

FIGURE 26.1 The Colosseum (Coliseum), or Flavian Amphitheater.

Emperor Hadrian was an innovative architect and designed a splendid villa near Tibur (Tivoli), about eighteen miles east of Rome. It surpassed Nero’s Golden House in complexity of design, and much of it remains. What is most striking about the whole complex is the imaginative combination of different geometric shapes—curves, octagons, rectangles, and squares—to create new visual effects.

Flavian and Trajanic public buildings

Augustus’ Julio-Claudian successors did not contribute greatly to the public architecture of Rome. The Flavians, on the other hand, introduced a dynamic era of public construction (plan, p. 390). Vespasian completed a temple of the Deified Claudius and began the great complex named the Temple of Peace (in commemoration of the end of the Jewish revolt), also called the Forum of Vespasian, near the Forum of Augustus and the original Forum. The actual temple faced a great colonnaded square and was flanked by rectangular halls that housed a library and, perhaps, some administrative functions.

Vespasian also began the monumental task of building the Colosseum (Coliseum), the Flavian Amphitheater as it was originally called. It arose on the site of Nero’s demolished Golden House and received the name Colosseum from the nearby colossal bronze statue originally intended for the vestibule of the Golden House (p. 432). The Colosseum’s remains stand today as a symbol of Roman imperial architecture, a massive structure showing a sophisticated blend of decorative styles and impressive engineering.

Titus continued work on the Colosseum and started to build the baths named for him over another part of the Golden House. Titus also began a temple to his father at the northwestern end of the old Forum and the arch that still bears his name at the top of the Via Sacra (Sacred Way) leading to the Forum (p. 441). Domitian completed the Colosseum and his brother’s projects and built a new stadium, with seats for 30,000 in the Campus Martius. It remained one of the city’s most famous structures for centuries. The length of the arena was about 750 feet, and its shape and size are preserved by the modern Piazza Navona. Between Vespasian’s forum and those of Augustus and Julius Caesar, Domitian constructed a narrow forum with a temple of Minerva at its northeast end. It is called the Forum Transitorium or the Forum of Nerva, who dedicated it after Domitian’s death.

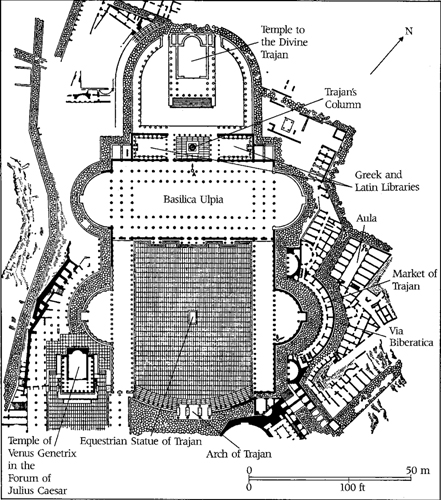

Before being assassinated, Domitian had also begun to construct what came to be called the Forum of Trajan and the Markets of Trajan, who extensively redesigned them. Trajan’s forum is the largest of the imperial fora, and its remains are still impressive. It was to the northwest of Augustus’ forum, and its southern corner bordered the northern corner of Caesar’s in order to complete Caesar’s original plan of providing a connection from the republican Forum to the Campus Martius. The base of the Quirinal Hill had to be cut back to make room for its enormous design. The main feature was a great basilica to house law courts. Behind the basilica, two libraries (one Latin and one Greek, as was customary) faced each other. In the midst of the courtyard between them stood one of Rome’s most remarkable monuments, the column of Trajan. After Trajan’s death, Hadrian built a magnificent temple to the Deified Trajan and Trajan’s wife, Plotina, on the open side of this courtyard so that the whole area had an architectural balance.

FIGURE 26.2 Plan of Trajan’s Forum, with Basilica Ulpia, Rome.

Across a street running along the outside of the forum’s northeast wall was a complex known today as the Market(s) of Trajan. It ran several stories up the side of the Quirinal. Instead of housing markets, it probably contained the offices of those who handled the daily business of the Empire.

Hadrian’s public buildings

In Rome, Hadrian was primarily concerned with rebuilding and restoring what already existed, but he was responsible for the construction of three unique projects that epitomize the way that Roman imperial architecture combined disparate forms and styles into structures that are both massive and interesting. The first was the largest temple in Rome—the Temple of Venus Felix and Roma Aeterna—between the Colosseum and the Temple of Peace (Forum of Vespasian). It was really two temples back to back. In the back of each was a seated statue, one of Venus and one of Roma. This arrangement took advantage of a convenient Latin pun: Venus is the goddess of love, amor in Latin, which is the name of Rome, Roma, spelled backward. Only its foundations remain, however. The emperor Maxentius rebuilt the temple with back-to-back apses in the early fourth century.

Hadrian’s most famous building is the Pantheon, Temple of All the Gods. A Christian church since 609, it is the best-preserved ancient building in Rome today. It is the perfect example of the imaginative combination of shapes and forms that distinguishes Roman imperial architecture. The front presents the columned and pedimented facade of a Classical Greek temple. This facade may preserve the lines and dedicatory inscription of the original Pantheon, built by Augustus’ colleague Marcus Agrippa, but it and the rest are almost completely the work of Hadrian’s builders.

The conventional facade joins a huge domed cylinder that is the temple proper. Thus, the rectilinear is uniquely combined with the curvilinear. This theme is carried out further in the rectangular receding coffers sunk in the curved ceiling of the dome, in the marble squares and circles of the floor, and in the alternating rectangular and curved niches around the wall of the drum. Moreover, the globe and the cylinder are combined because the diameter of the drum is the same as the distance from the floor to the top of the dome, so that if the curve of the dome were extended, it would be tangent with the floor and wall of the drum. Finally, the whole building is lighted by a round opening, the oculus (eye), about thirty feet in diameter in the top of the dome. This hole is open to the weather, but because of its great height, most moisture evaporates before it reaches the floor during a rain.

The dome exemplifies how Roman engineers took advantage of the properties of concrete, whose use the Romans greatly advanced. To reduce the dome’s weight, progressively less dense material was used in the concrete as the dome rose, and the dome was made thinner as it neared the top. The recessed coffers reduced the weight still further and created a grid of structural ribs. Once the concrete set, the dome was a solid, jointless mass of exceptional stability, as its survival for 1900 years testifies.

Across the Tiber, there arose another architectural marvel of the age—Hadrian’s tomb—a colossal round mausoleum over 200 feet in diameter. It eventually held the bodies of Hadrian, his successors through Caracalla, and a number of their family members. In the Middle Ages that massive structure long served as a fortress and was known as the Castel Sant’ Angelo, a name it still bears. After Hadrian, the pace of building in second-century Rome slackened considerably.

FIGURE 26.3 Front view of Hadrian’s Pantheon, with an inscription from Agrippa’s earlier building.

Architecture in the provinces

A fine example of imperial architecture and planning in a smaller town is Thamugadi (Timgad), a colony established by Trajan for veterans in North Africa. It was laid out on a grid of broad, intersecting main streets and side streets. The main streets were colonnaded, and other amenities, including a large Greek-style theater, baths, and a well-appointed forum, were provided. By 200 c.e., 12,000 to 15,000 people dwelt there in comfort and security.

Sculpture

The Roman tradition of realistic portraits and statues continued through the second century c.e., as can be seen in the busts of the various emperors. The best example is the bronze statue of Marcus Aurelius mounted on a horse, the single bronze equestrian statue to have survived from antiquity (p. 472). Panels of sculptured relief in the tradition of Augustus’ Ara Pacis (p. 392) constituted one of the most common forms of official art. In the courtyard behind the Basilica Ulpia, however, Trajan set up a completely new kind of relief to commemorate his Dacian wars. It is a column about twelve feet in diameter and exactly one hundred Roman feet (about ninety-seven English feet) high. Around this column winds a spiral relief depicting the wars themselves. The vast and complex logistical, engineering, and military aspects of the wars are portrayed in a realistically detailed narrative that leads dramatically to the death of King Decebalus. There are some 2500 separate figures, but through it all, Trajan is a unifying presence appearing over fifty times. The width of the spiral and size of the figures increase as they move upward to compensate for the greater viewing distance from the ground. A bronze statue of Trajan surmounted the top until it was replaced by one of St. Peter in 1588. The large pedestal on which the column rests was Trajan’s mausoleum.

FIGURE 26.4 City of Thamugadi (Timgad).

Marcus Aurelius imitated Trajan’s column with one of his own in the Campus Martius. Its dimensions are the same, and it has a spiral relief depicting the Second Marcomannic War (172–175). Artistically, however, this relief is very different from Trajan’s. The realistic details of scenery are omitted, there is no attempt at three-dimensional spatial relationships, and there is no unified, dramatic narrative sequence. There is constant motion and striving, almost chaos. Through it all, however, Marcus Aurelius stands out. He is not merely part of the action. He repeatedly faces outward and dominates the viewer’s attention to become a solid, powerful presence in the midst of all the confused action. The details of mundane reality are sacrificed to present the viewer directly with the essence of the emperor’s role in events. This style approaches the “otherworldly” art of the late Empire and the Middle Ages.

Painting

Most of what is known of Roman painting in the first two centuries c.e. comes from the wall paintings found at Pompeii, Herculaneum, and other sites buried by the eruption of Vesuvius in 79 during Titus’ reign. These frescoes are the work of artists and craftsmen adapting or copying on plaster the works of great masters or following standardized decorative scenes according to the tastes of their customers. Pleasant or romantic landscapes, still lifes, and scenes from famous myths or epics abound.

Decorators set off these scenes by painting the surrounding wall in an architectural style. From roughly 14 to 62, the Third (Egyptianizing) Style was most popular. Instead of creating the illusion of depth, the painters used painted architectural forms to provide a flat frame within which the picture could be featured. After 62, the Fourth (Ornamental) Style prevailed: perspective is heavily used to give the illusion of infinite depth behind the wall, and there is great flamboyance in the design of the architectural forms. They often resemble stage sets, are weighed down with intricate detail to the point of looking like baroque fantasies, and probably show the influence of Nero’s tastes, which can be seen in the surviving decorations from his Golden House.

Mosaics, coins, and medallions

Numerous mosaics from the first two centuries c.e. are found all over the Empire, especially in the villas of North Africa. They are very valuable documents for social and economic life. They also exhibit remarkable taste and workmanship. The coins and medallions of this period are among the finest in history. The art of medal engraving was stimulated by Hadrian’s issue of a series of bronze medallions. They reveal a love of symbolism and allegory and reached a level of skill and technique comparable to that of the most beautiful coinages in the ancient world.

Social developments

As already seen, the composition of the Roman upper class changed over the first two centuries because emperors recruited administrators from the local Italian and provincial elites as loyal counterweights to the old republican senatorial families of Rome. Members of those families were understandably resentful. After the purges of Nero and Domitian, however, most of the old republican noble families had disappeared.

FIGURE 26.5 Frescoed walls (ca. 60–79 c.e.) of a room from the house of the Vettii, rich wine merchants of Pompeii.

Upper-class women

In the early Empire, there was a concerted attempt to “put women back in their place.” This attempt was reinforced by widespread Roman exposure to Classical Greek literature and philosophy, which tended to view women with a certain amount of anxiety, hostility, and insistence on their inherent inferiority. This view is paramount in the sixth satire of Juvenal (p. 484). Earlier, Augustus’ marriage legislation had tried to make women conform to the ideal of virtuous wife and mother. Still, women of the imperial family and upper classes carried on the late Republic’s tradition of actively involved women who strove to pursue their own and their families’ agendas. Augustus’ ex-wife Scribonia and his last wife, Livia, are prime examples. Mothers and wives of emperors were often depicted on coins and deified or otherwise honored to advertise their family connections and exalt their sons and husbands. Inscriptions and statues honored women throughout the provinces for their civic benefactions and numerous other women for accomplishments as athletes, musicians, and physicians.

Despite old biases and hostility, the legal rights of women improved in step with social reality. In 126, Hadrian liberalized women’s right to make wills. Marcus Aurelius made it legal for mothers, not just fathers, to inherit from children.

The lower classes

Unfortunately, the poor and the powerless, male and female, in any society seldom see dramatic improvements in their overall conditions. Still, the lot of lower-class citizens, freedpersons, provincials, and slaves improved somewhat over the first two centuries c.e. in comparison with the first century b.c.e. The general internal peace and prosperity of the period fostered traditional upper-class patronage and euergetism. Life became a little more secure and less desperate for the great mass of people. Almost all of the emperors tried to alleviate real hardship. They made great efforts to secure a stable grain supply for Rome in order to sustain those who received free grain and keep the price affordable for the rest. The urban poor also benefited from the emperors’ efforts to improve flood control, housing conditions, and the water supply and to upgrade public sanitation through the construction of public latrines and baths. In many of the great provincial cities, wealthy local benefactors undertook similar projects.

At least in Italy, children outside of Rome benefited from private charitable endowments and the alimenta of Trajan and his successors, but girls always received less per capita than boys. In the provinces, the emperors’ attempts to provide efficient and honest administration must have kept the peasantry from being exploited so mercilessly as they often had been. It would be naive, however, to think that all imperial officials acted as scrupulously as they were supposed to.

Some well-educated Greek slaves and freed slaves in the imperial household had impressive careers. Narcissus, Callistus, Polybius, and Pallas are notable under Claudius (p. 423). The freedwoman Claudia Acte was an important figure in the Emperor Claudius’ household. She became Seneca’s confidante as well as Nero’s mistress. She acquired great wealth in land and slaves and remained loyal to Nero even after he married Poppaea Sabina.

One of the most interesting freedwomen in Roman history is Antonia Caenis. She was Antonia the Younger’s confidential secretary. Surviving Caligula’s reign, she served both Claudius and Nero. She became the mistress of the rising young officer Vespasian until he married. Still, she continued to advance his career in court circles. They resumed their relationship after his wife died. She lived with him in the palace until she died.

Some freedpersons from less exalted households also became very wealthy. Others practiced middle-class trades and professions, and still others existed at the poverty level. All remained second-class citizens despite being eligible for honorific posts such as Augustalis (p. 358).

It is difficult to know the effect of humane legislation by Hadrian and Antoninus Pius on the treatment of slaves (p. 464 and 467). Manumissions were still frequent, as the innumerable funerary inscriptions of freedpersons prove. Augustus’ attempt to reduce manumissions by taxing them and limiting the number of slaves that a master could free in his will had a limited effect. Regardless of more enlightened attitudes on the part of some, slaves were still subject to torture as witnesses, and if a slave killed a master, all of his slaves could be punished by death.

Middle-class prosperity and urban growth

Under the general peace and stability within the Empire during the first two centuries c.e., the wealth of the Empire rose dramatically. People of moderate means or possessed of talent, enterprise, and good luck prospered to an extent never known before (and only again in recent times). Increased incomes gave rise to an unprecedented urge to travel, which was further encouraged by the construction of a huge network of excellent roads. Greater prosperity was reflected in the rebuilding of old cities, the colonization of new sites, and the growth of important settlements around major military camps on the frontiers. A traveler in Asia Minor, North Africa, Spain, or Gaul would see familiar-looking temples, theaters, libraries, baths, and fine homes everywhere.

Economic trends

The growth of Rome and other cities continued to stimulate imperial agriculture, industry, and commerce, but Italy declined as a center of production in relation to the provinces as the products of farm and shop moved freely over land and sea. Foreign trade steadily expanded.

Agriculture

In the eastern provinces, the establishment of peace and better administration after the end of Rome’s civil wars ultimately promoted the revival of agriculture, which continued to be dominated by smallholders. Agriculture in the western provinces expanded to supply the huge Roman market. On the other hand, provincial competition hurt small, marginal producers in Italy. Their decline led to the creation of far-flung holdings known as latifundia (p. 176). Smallholders gave up their land to large operators and became tenant farmers, coloni, in return for a fixed share of their crops. Latifundia began to appear even in the great grain-growing regions of North Africa, Sicily, and Gaul.

Mining and manufacturing

The creation of stable frontiers and the construction of great roads, harbors, and canals throughout the Empire also opened up new sources of raw materials and encouraged the spread of manufacturing. The production of lead ingots and pig iron was of major importance in Britain. Tin, copper, and silver continued to be important in Spain. The gold mines of the new province of Dacia were vigorously exploited.

In the East, the old manufacturing centers flourished. The workshops of Egypt and Syria produced papyrus, blown glass, textiles, purple dye, and leather goods. Asia Minor supplied marble, pottery, parchment, carpets, and cloth.

In the West, the Italian producers of glass, pottery, and bronze wares sent their products far and wide during the first century. Then they went into decline as provincial centers, especially in Gaul and the Rhineland, took over their export markets during the second. In the first century, Lugdunum (Lyons) in Gaul became the center of the western glass industry, although the second century saw Colonia Agrippina (Cologne) in Germany replace it. Terra sigillata, the famous red dinnerware with raised decorations from Arretium in Italy (p. 386), was successfully imitated by Gallic potters on a vast scale for western European markets. Even the famous bronze workers of Capua lost their western markets to Gaul’s skilled craftsmen.

Imperial commerce

Once provincial farmers and craftsmen made products comparable to those of Italy, their proximity to local markets gave them an unbeatable advantage over Italian exporters. Also, compared with products from the interior of Italy, provincial products originating near the seacoast or on waterways often had better access to the lucrative markets of Rome and coastal Italian cities. For example, despite the wonderful network of imperial roads, it was still cheaper to ship an amphora of wine from Arelate (Arles) or Narbo in southern Gaul to Rome by sea than to transport one overland to Rome from only fifty miles away in Italy.

The same factors, however, sharply limited the potential for manufacturing and commerce in the provinces beyond the points achieved by the second century c.e. Only producers with easy access to water transport could profitably export. Moreover, the slowness of transportation and the lack of refrigeration or modern preservation techniques meant that only spoilage-resistant agricultural products or salted and pickled foods could be shipped long distances. Only expensive manufactured goods whose production was limited by the geographic location of raw materials or highly specialized craftsmen could be profitably exported over significant distances. Therefore, the market for such goods was limited to the well-to-do. The mass of people either had to do without or settle for inferior locally manufactured imitations. As a result, most manufacturing tended to remain small and localized, and large-scale commerce was limited.

Foreign commerce