Chapter 27

The third century c.e. in Roman history really began with the death of Marcus Aurelius in 180 and lasted a little more than hundred years until the accession of Diocletian in 284/285. It falls into two almost equal parts. The first extends from the death of Marcus Aurelius in 180 to the assassination of Severus Alexander in 235. During that time, the frontiers of the Empire remained well defended, although under pressure. Only two serious internal political crises arose: from 193 to early 197 and from 217 to 221. The century’s second part stretches from 235 to the ultimate victory of Diocletian in 285. Frequent civil wars and assassinations saw the rapid rise and fall of twenty-six emperors or pretenders, constant breakthroughs on the borders, and the near breakup of the Empire under those two stresses and a devastating plague.

Despite the differences between the first and second parts of the third century, several political trends give it unity throughout. The city of Rome itself remained of great symbolic significance, but actual power shifted to the frontier provinces. Their defense demanded ever more attention. The growing importance of defense and the provinces is clearly illustrated by the fact that almost all of the third-century emperors were generals of provincial birth. Many came from the Danubian provinces, where the problems of defense were often acute and where many of the Empire’s best soldiers were recruited.

The growing importance of the provinces and the parallel decline of Roman and Italian primacy also led to increasing regionalism, sectionalism, and disunity. Often the armies and inhabitants of one province or region would support their own claimant to the throne or oppose a challenger from another part. At times, some areas even broke away under their own emperors.

Defense and personal safety became the overriding concerns of emperors. Their office increasingly lost the characteristics of a civilian magistracy that it had retained since the days of Augustus. The Principate was becoming an absolute monarchy resting on raw military power and the trappings of divine kingship along Near Eastern and Hellenistic lines. Also, as the emperors tried to mobilize all the state’s resources to meet its defensive needs, the bulk of its people sank into the status of suffering subjects instead of satisfied citizens. The wealthy and influential few, mainly senators and equestrians, were neutralized and co-opted by grants of greater social and legal privileges and lucrative posts in the imperial bureaucracy. The lower classes, however, paid harsher penalties than others for crimes and were subject to greater oppression in the name of the state. In better times, more benevolent or less desperate emperors had afforded them a measure of protection and dignity.

Sources for Roman history, 180 to 285 c.e.

The lack of reliable written accounts makes the period from 180 to 285, especially after 235, difficult for historians. Cassius Dio’s later and most valuable books (except 79 and 80), which covered his own times, are preserved only in epitomes and fragments. Valuable information about the period from 180 to 238 is contained in the eight extant books of Herodian’s contemporary History of the Empire after Marcus in Greek and the Historia Augusta, probably from the late fourth century, in Latin. Unfortunately, Herodian’s moralizing rhetoric sometimes reduces his reliability, and the biographies of emperors starting half-way through Elagabalus’ reign (218–222) in the Historia Augusta are more romantic fiction than history. Minor relevant historical works from the fourth century include biographies like Aurelius Victor’s Caesares and the anonymous Epitome de Caesaribus and brief histories of Rome like those of Eutropius and Rufius Festus (pp. 632–3). In the late fifth or early sixth century, Zosimus, a pagan Greek, covered events from 270 to 410 in an account called the New History. Unfortunately, the first of its six books is missing the section on Diocletian.

Sources written in Syriac, a dialect of Aramaic that was spoken in a region extending from Asia Minor to the Arabian peninsula, are increasingly important for the period. They include such secular writings as the Letter of Mara bar Serapion and several chronicles. Syriac Christian writings such as the Oration of Meliton the Philosopher before Antoninus Caesar, the Acts of Thomas, and several martyrologies are particularly valuable.

Greek and Latin Christian writers also became more numerous and important during the third century. They supply much information on the history and doctrinal controversies of the expanding Christian Church and on secular affairs as well. Among the Latin Christian authors, the most notable in this period are Tertullian and St. Cyprian (p. 559). Tertullian’s works reveal much about the social life of the period. St. Cyprian’s works are particularly valuable for the history of the persecution of Christians that occurred in the 250s. They also cover the Donatist controversy over Christians who denied their religion during the persecution and then wanted to be taken back by the faithful afterward. Also valuable for this period are St. Jerome’s De Viris Illustribus (On Famous Men) and his translation and extension of Eusebius’ Chronicle (p. 565).

Of the contemporary Greek Church Fathers, Clement of Alexandria and Origen stand out (p. 560). They document the growth of Christian theology and provide unusual glimpses into the pagan Greek mysteries that they combated. Eusebius of Caesarea in Palestine (ca. 260–ca. 340) produced two historical works that are valuable in reconstructing the third century. The original Greek version of his chronicle of events from Abraham to 327/328 c.e. is lost, but its substance is preserved in an Armenian translation and in Jerome’s extended version. Fortunately, his Ecclesiastical History, an invaluable general account of the growth of the early Church in the Empire, is intact.

Justinian’s codification and summary of the Civil Law (p. 675) preserves numerous fragments of third-century legal works. Together with coins, papyri, inscriptions, and archaeological material, they constitute the bulk of information about life in the third century. In particular, avid interest in local archaeology throughout countries once embraced by the Roman Empire has produced a better understanding of defensive policies and the social and economic conditions of the provinces.

Commodus (180 to 192 c.e.)

Marcus Aurelius had done everything that he could to prepare his son and heir, Commodus, for his role as emperor and ensure a smooth transition of power. Commodus had been given the best teachers available, had been proclaimed a Caesar at age five, and had received a grant of imperium, a consulship, and the title Augustus at fifteen. From then on he was joint ruler with his father.

Aurelius had reasonably expected that after he died, his experienced advisors would continue to guide his young heir along the path that he had set. Unfortunately, sometimes the advisors disagreed. This dissonance eventually contributed to divisions and jealousies among members of the imperial family, military officers, and powerful senators. The consequences for Commodus’ reign were disastrous. Some advisors, like T. Claudius Pompeianus, second husband of Commodus’ sister Lucilla, wanted Commodus to finish his father’s great war with the Quadi and the Marcomanni. Others, whether out of conviction or desire to advance in the new emperor’s favor or both, advised him to negotiate a settlement and return to Rome. A negotiated settlement had much to recommend itself: the war had already placed a great strain on imperial resources. The Roman army had been weakened by plague. Although Aurelius’ plans for a frontier based on the Elbe River and the Carpathian Mountains did have some strategic advantages over the longer Rhine–Danube line, it would have greatly extended the Empire’s lines of supply through territory that would take a long time and many troops to pacify adequately.

Commodus sided with those who advised negotiation. Still, he kept up the military pressure for several months after Aurelius’ death in order to obtain a peace in accordance with well-established Roman precedents. The Quadi, Marcomanni, and Iazyges agreed to surrender Roman deserters and captives, create a demilitarized zone along the Danube, furnish troops to the Roman army, and help feed that army with annual contributions of grain. This settlement was reasonable and produced stability along the Danube for many years.

A young emperor’s problems

A newcomer who had great influence with Commodus was the palace chamberlain (cubicularius), a Bithynian Greek freedman, Saoterus. Not since Claudius and Nero had imperial freedmen enjoyed such public prominence as Commodus gave Saoterus. He seems to have generated the kind of resentment among the upper classes, particularly the senators, that the freedmen of those earlier emperors had incurred. For his part, Commodus was like the young emperors Caligula, Nero, and Domitian in that they, too, had also assumed the position of princeps without serious prior experience in working with senators. Commodus failed to appreciate how important it was to maintain the goodwill of these wealthy and influential men, who bitterly resented affronts to their dignitas. He did not understand that emperors needed at least to appear to share power with the senatorial elite if they wished to remain secure on their thrones.

Military men of senatorial rank were another problem. Marcus Aurelius had promoted a number of talented new men to the senate and major military commands during his long wars. They were eager for an opportunity to earn greater glory. Many were unhappy with Commodus’ decision to abandon his father’s expansionistic policy, which would have given them that chance.

The situation was made worse when Commodus’ marriage failed to produce an heir. It tempted other people with some connection to the imperial family to try for the throne. They believed that they could gain support from those who disliked Commodus and also satisfy those who supported dynastic succession. Thus, several factors combined to create a deadly atmosphere of intrigue, fear, and suspicion that left an indelible mark on the surviving sources for Commodus’ reign. These sources are undoubtedly biased and sensationalistic, but they still reflect serious underlying problems.

Lucilla: plots, power plays, and executions

As early as 182, a number of senators conspired with Commodus’ sister Lucilla (Annia Aurelia Galeria Lucilla) to assassinate him. Her second husband, T. Claudius Pompeianus, whom she could not tolerate, was not one of them. Her daughter (by her first husband, Lucius Verus [pp. 469–70]) and two of her lovers were. One of those two was Quintianus. He was Claudius Pompeianus’ nephew or son by a previous marriage and was engaged to her daughter. The other was Ummidius Quadratus. He was a relative of Marcus Aurelius by adoption and stepson of one of Commodus’ other sisters. Quintianus bungled the assassination when he paused to proclaim that the senate was sending the dagger in his hand. Commodus’ bodyguard grabbed him, and the plot failed.

All of the conspirators were arrested and executed, even Lucilla after she was briefly exiled on the Isle of Capri. Soon, suspicion also fell on Commodus’ wife, Bruttia Crispina, daughter of one of Aurelius’ old advisors. Accused of adultery, she, too, was executed after a short exile on Capri. The innocent Claudius Pompeianus prudently retired from public life to avoid any suspicion of wanting to be emperor. Ironically, two members of Ummidius’ household became close members of Commodus’ court: the freedman Eclectus eventually became Commodus’ chamberlain, and the freedwoman Marcia soon became his concubine.

Right after the failed coup of 182, the joint praetorian prefects, P. Taruttienus Paternus and Sextus Tigidius Perennis, along with the freedman M. Aurelius Cleander, caused the murder of Saoterus. Cleander replaced him. When Paternus was promoted to the senate, Perennis became sole praetorian prefect and promptly engineered Paternus’ execution on the charge that he was plotting to place his son-in-law on the throne. For the next two years, Perennis was the dominant figure at court.

A number of senators who had been close friends of Marcus Aurelius were executed on charges of being associates of Paternus and seeking to overthrow Commodus. Perennis also removed senatorial generals from their commands and replaced them with equestrian legates. Two of those who were removed seized chances later to become emperor, Helvius Pertinax (a protégé of Claudius Pompeianus) and Septimius Severus. Didius Julianus, a relative of Paternus’ son-in-law, also made a bid. In the meantime, morale in the armies declined and gave rise to a series of provincial mutinies (sometimes called the Deserters’ War), which seems to have spawned another attempt at assassination.

In 185, Perennis himself succumbed to a group of palace freedmen under the leadership of Cleander as chamberlain. The freedwoman Marcia also participated. Allegedly, Cleander and Marcia appointed imperial administrators in return for large bribes and controlled affairs in general. A series of praetorian prefects rose and fell until Cleander took an unprecedented step for a freedman and had himself appointed as an equal to the regular joint prefects in 188.

Cleander met his fate two years later in a plot that may have been orchestrated by Helvius Pertinax in conjunction with a group of men connected to the province of Africa, where Pertinax had served as proconsul. Pertinax was now urban prefect and commanded the Urban Cohorts. The man who soon replaced Cleander as praetorian prefect, Q. Aemilius Laetus, was also from Africa. Laetus, in turn, appointed his fellow African provincial, the future Emperor Septimius Severus, as governor of the strategic Danubian province of Panonnia. Severus, moreover, had served as Pertinax’s legate in Syria. Severus’ brother was appointed to govern the Danubian province of Lower Moesia. Another African provincial, Decimus Clodius Albinus, received the important command of the armies in Britain.

Provincial administration and defense under Commodus

Commodus apparently left the routine running of the Empire to his favorites. It was in their best interest to see that the system functioned smoothly even when they were pursuing their own personal agenda. Under Perennis, there were serious incursions from the North of Britain into the Roman province. Even the governor was killed. A new governor retrieved the situation and enabled Commodus to be proclaimed Britannicus in 184. Apparently, however, the new governor’s harsh discipline soon provoked a rebellion in the legions. Perennis fell to Cleander before he could take any action. Ironically, Cleander called on Pertinax, whom Perennis had earlier cashiered. Pertinax revived his career by restoring order among the legions in Britain.

It is clear that Commodus’ treaty with tribes across the Danube did not lead to Roman neglect in that quarter. Under Perennis, operations occurred beyond Dacia, probably against Sarmatian tribes. In 188, preparations were underway for a sequel to Aurelius’ two German wars. Probably they were directed at an uprising of the Quadi. Either they were sufficient by themselves to restore peace or they were dropped because of another conspiracy against Commodus.

In North Africa, Roman commanders conducted operations against the Mauri (Moors) and extended or enlarged Roman defenses in Mauretania and Numidia. In the East, imperial governors faithfully maintained the network of fortifications and roads that protected Rome’s provinces. Throughout the Empire, disaster relief and benefactions, all in the Emperor’s name, of course, were provided to various cities and gratefully acknowledged with laudatory inscriptions.

Commodus’ quest for popular adoration

Although Commodus ignored the sensibilities of the senate, he carefully cultivated popularity among the masses at Rome. In 186, he established a fleet to carry food supplies from the province of Africa to Rome on a regular basis. That kept supplies plentiful, prices low, and the common people of Rome happy. During his twelve-year reign, he made eight congiaria (donations of money) to the citizens and entertained them frequently with lavish shows of chariot races, gladiatorial combats, and beast hunts in the arena.

Commodus sought to win popularity with the spectators of these spectacles by taking part himself. Demonstrating his skill with javelin and bow, he killed hundreds of wild beasts in the arena. He trained and fought left-handed as the kind of light-armed gladiator called a secutor (pursuer). In the last year of his life, he even set up an inscription boasting of 620 victories in gladiatorial combat, more than any other left-handed fighter.

Commodus’ association with divinity

That inscription was on the base of the colossal statue in front of the Colosseum. Commodus had his head placed atop the statue and added the club and lion skin of Hercules. Numerous coins and portrait busts depicting Commodus as Hercules also appeared. Hercules was one of the most popular gods in the ancient world. He was a mortal who had achieved divinity by his great deeds on behalf of humanity. Rulers since Alexander the Great had sought to be identified in the popular mind with this divine hero. Commodus, toward the end of his life, even celebrated himself on coins as HERCULES COMMODUS.

In his last year, Commodus also associated himself in statues and on coins with various other deities such as Jupiter, Mithras, Sol (the Sun), Cybele, Serapis, and Isis. Clearly, he was aiming to become some kind of divine absolute ruler. He had his clothes embroidered with gold and used various titles associated with deities. He even turned Rome into a colony whose name, Commodiana, came from his own. Therefore, he would not be just the ruler of the city but literally its venerated founder and creator.

The assassination of Commodus, December 31, 192 c.e.

Commodus’ actions finally alienated so many people that there was no one left to protect him. His attempts to buy popularity exacerbated the fiscal crisis evident since his father’s wars. It forced him to debase the coinage in order to cover expenses. By 186, the weight of the denarius had fallen 8.5 percent and its silver content from 79.07 fineness (percent of precious metal) to 74.25. Inflation was the unhappy result. Even worse, during his last two years, his need for more and more money as well as his fear of conspiracy fueled an alarming increase in the executions of prominent persons and the confiscation of their property. On top of that, a disastrous fire swept through Rome in 192.

It is alleged that at the end of 192, Commodus was planning to move permanently into the gladiatorial barracks next to the Colosseum, kill the two new consuls on January 1, and, dressed as a gladiator, become sole consul in their place. This story may have been circulated to justify his assassination. At any rate, the Praetorian Prefect Laetus, the freedman Eclectus, who had replaced Cleander as chamberlain, and Commodus’ concubine Marcia believed that it was no longer safe to let Commodus continue. Marcia attempted the actual murder by poisoning his dinner on December 31. Apparently, the effects of too much wine during the day’s end-of-year celebrations caused him to vomit most of the poison. While he was recovering in his bath, his wrestling partner, Narcissus, another freedman who had joined the plot, strangled him.

Pertinax (January 1 to March 28, 193 c.e.)

It is not difficult to see the hand of Helvius Pertinax at work behind the scenes: during the past two years, his friends had been placed in strategic commands. Now, Laetus and Eclectus informed him immediately after the deed was done and accompanied him to the camp of the Praetorian Guard. With their help, Pertinax received the acclamation of the guardsmen after he had promised each one 12,000 sesterces. Then, while it was still very dark, he called a meeting of the senate to confirm his accession. In the meantime, Claudius Pompeianus, Pertinax’s old benefactor, arrived in Rome. He could not have come from his villa sixty miles away so soon after Commodus’ assassination unless he had been notified of the plot in advance. Pertinax tactfully offered to step aside in his favor, and he, equally tactfully, refused, thereby giving the blessing that Pertinax had probably desired.

The senate gratefully confirmed Pertinax and vociferously damned Commodus’ memory. Yet, Pertinax ensured his body a decent burial despite calls for throwing it into the Tiber. Pertinax attempted to restore order and refill the treasury. He reduced taxes in general, granted clear title and ten years’ remission of taxes to new occupiers of war-torn and plague-depopulated land, and put up for sale the luxuries that Commodus had accumulated in his palace. He even restored the coinage to the weight and fineness of Vespasian’s day.

Unfortunately, he made two serious mistakes. Selling off high offices to raise needed money alienated many senators who had been offended by the practice under Commodus. Also, like Galba after Nero, Pertinax alienated the Praetorian Guard, whose support had been only grudging. He failed to indulge the guardsmen and their prefect Laetus as much as they had expected. After two unsuccessful coups, a group of guardsmen marched on the palace and murdered him only eighty-seven days after he had taken office.

Didius Julianus (March 28 to June 1, 193 c.e.)

The oft-repeated ancient story that the guardsmen then held an auction and gave the throne to M. Didius Julianus is a highly exaggerated oversimplification. Laetus probably had chosen Julianus before the murder of Pertinax. After it, in the guardsmen’s absence from the praetorian camp, Pertinax’s father-in-law offered the guardsmen 20,000 sesterces each for their support. Julianus arrived and secured their backing by pointing out the danger to them of choosing a man whose son-in-law they had just murdered and by promising each man 25,000 sesterces.

Confirmed by a helpless senate, Julianus still faced opposition. Hostile crowds finally thronged into the Circus and called for the governor of Syria, Pescennius Niger, to seize the throne. Clodius Albinus in Britain and Septimius Severus on the Danube also claimed the purple. Septimius raced to Rome first. Julianus initially resisted and then negotiated with Severus. Deserted by the praetorians, whose shifty prefect Laetus he had removed, Julianus was murdered by a guardsman on his sixty-sixth day as emperor.

The accession of Septimius Severus (193 to 211 c.e.)

L. Septimius Severus was a native of Africa and spoke Latin with a Punic accent. He was born in 146 at Lepcis (Leptis) Magna, a town not far from modern Tripoli (ancient Oea). He is proof of the growing importance of the provinces. He had enjoyed an active career, was well educated, and loved the company of poets and philosophers. Apparently, his first wife had died childless. His second was a rich and intelligent Syrian woman named Julia Domna, who bore him two sons—Septimius Bassianus (Caracalla) and Septimius Geta.

Severus moved swiftly to consolidate his power. He seized the various treasuries, restocked the depleted granaries of the city, and avenged the murder of Pertinax, whose name he assumed. He increased the pay of his own troops to make sure of their continued loyalty and disbanded the Italian Praetorian Guard. He then replaced it with 15,000 of his best legionary soldiers, largely from Illyria and Thrace. The change in the composition of the Guard helped to remove the special privileges of Italy in the choosing of emperors and in the government of the Empire.

The war against Pescennius Niger, 193 to 194 c.e.

Severus thereupon set about dealing with one rival at a time. He temporarily acknowledged Clodius Albinus in Britain as his adopted successor with the title of Caesar. That would secure his rear as he advanced east against Niger. Meanwhile, Niger had won major support in the provinces of Asia and Egypt. He had also seized Byzantium as a base from which he could threaten Severus’ Danubian provinces. In a swift and savage campaign, Severus defeated Niger and captured Antioch. Niger was overtaken and killed as he attempted to escape to the Parthians across the Euphrates. Byzantium, however, fell in late 195 only after a protracted siege. It was virtually destroyed and was reduced to a dependency of neighboring Perinthus until it was rebuilt a few years later.

First War against Parthia, 194 to 195 c.e.

After Niger’s defeat and death, Severus attacked Parthia. King Vologeses IV had not only offered assistance to Niger but had tampered with the loyalty and allegiance of the king of Osrhoene, a Roman client in northwestern Mesopotamia (map, p. 369). In 194 and 195, Severus overran Osrhoene (most of which he turned into a Roman province), northern Mesopotamia, and Adiabene (northern Assyria). Here the campaign came to an abrupt end.

The war against Clodius Albinus, 195 to 197 c.e.

At the other end of the Empire, Albinus had amassed an army in Britain for a conflict with Severus. Albinus had been growing suspicious of the emperor’s sincerity in acknowledging him as Caesar and successor. Supported by a large following in the senate, he decided to make a bid for supreme power. To enforce his claim, he crossed over into Gaul and set up headquarters at Lugdunum (Lyons). He received considerable support in Gaul and Spain as well as Britain. Septimius drew his forces mainly from the Danubian provinces and Syria.

Severus headed west after the fall of Byzantium secured his rear. Other loyal officers had gone earlier to secure Rome, Italy, and the northern provinces. Severus stopped to reinforce the loyalty of armies along the way and then spent time in building up popular support at Rome and asserting control over the senate and public affairs. He finally collected his forces in Pannonia in early 197 and marched on Gaul. Near Lugdunum, the two enemies fought a furious battle that ended in the defeat and suicide of Albinus. Severus allowed his victorious troops to sack and burn the city of Lugdunum and carried out a ruthless extermination of the adherents of Albinus in the provinces and in the Roman senate.

New sources of Imperial authority and legitimacy

Although Severus had arrived in Rome at the head of an army in 193, he had tried to conciliate the senate and cooperate in order to legitimize his claim to the throne against his rivals. He had already taken the name of Pertinax so that he could pose as the avenger of the previously slain senatorial appointee. In Rome, he had donned civilian dress and had sworn to the senators that he would never execute a senator without a trial by peers. He also had promised not to encourage the use of informers.

Severus had little chance to prove himself. Many in the senate either distrusted him or, because he had been born a provincial of only equestrian rank, disliked him. Although Clodius Albinus had come from Africa, he was of the hereditary nobility. Therefore, he had been much more acceptable to the senate. In particular, he may have had the support of those who had backed Didius Julianus. The latter’s mother came from Albinus’ hometown. Senators who promoted the fortunes of Albinus had inevitably provoked Severus’ wrath. Therefore, after he had secured the East against Pescennius Niger and Parthia, Severus dropped the policy of conciliation with the senate and formally relied on the army as his principal source of authority in establishing himself and his family as a new dynasty at Rome.

In the past, the army had been used to force the senate, which was still the recognized source of legitimate authority, to authorize the appointment of a new emperor. Septimius Severus, however, went a long way to making the army the recognized source of authority instead. For example, in 195 he had the army in Mesopotamia declare Albinus a public enemy in order to legitimize the war against him. In the same year, he also had the army ratify his adoption into the family of Marcus Aurelius, the Antonines, and proclaim the deification of his “brother” Commodus. (Because the senate itself had condemned the memory of Commodus, he even forced it to revoke its previous action.) In 195 or 196, he also had the army proclaim his elder son, Septimius Bassianus (Caracalla), as Caesar in place of Clodius Albinus and bestow the name Marcus Aurelius Antoninus upon him in order to emphasize the family’s new Antonine pedigree.

This pedigree legitimized the claim of Severus and his sons to the throne through dynastic succession. It also allowed Septimius to claim the support of divinity for himself and his family. He was now the “son” and “brother” of deified emperors. While publicizing numerous portents foretelling his accession to the throne, Severus officially reinforced his claims to divine sanction through coins, inscriptions, and the imperial cult. In the military camps, the statues of Severus and other members of his family were worshiped as the domus divina (Divine House). Severus unofficially came to be called dominus (lord), a title with increasingly divine overtones. On one coin, his younger son, Geta, is depicted as the sun god crowned with rays, giving a benediction, and identified as Son of Severus the Unconquered, Pius Augustus, a designation that recalls the Unconquered Sun, an increasingly popular deity. Severus’ wife, Julia Domna, is portrayed as the Great Mother Cybele on some coins and on others as seated on the throne of Juno. She was hailed as Mother of the Augusti, Mother of the Senate, or Mother of the Fatherland (Mater Patriae). Severus is also referred to in inscriptions as a numen praesens (present spirit), and dedications were made to him as a numen, clear indications of his divinity.

Systematic reform

Having defeated Albinus and clearly established new bases of imperial authority and legitimacy, Septimius Severus initiated the most comprehensive series of changes in the Roman government since the reign of Augustus. Up to his time, many changes had occurred, but they had been subtle and evolutionary. What Septimius did was often in line with changes that had been gradually occurring. Still, he was the first to give them formal expression. Also, he was revolutionary in ruthlessly following their implications to create a clearly new system that gave an entirely different spirit to the Principate.

Major downgrading of the senate

Severus took his revenge on the senate by revoking its right to try its own members. He condemned twenty-nine of them for treason in supporting Albinus. He also appointed many new members, particularly from Africa and the East, who would be loyal to him. Italian senators became a minority. Moreover, he favored equites with a military background over senators in administrative appointments as deputy governors in senatorial provinces and as temporary replacements when regular senatorial governors became ill or died. When he added three new legions to the army, he put equestrian prefects instead of senatorial legates in command. He also abolished the senatorially staffed standing jury courts (quaestiones perpetuae). He placed cases formerly heard by them under the jurisdiction of the city prefect (praefectus urbi) within a hundred-mile radius of Rome and the praetorian prefect (praefectus praetorio) everywhere else.

As the result of a process of evolution dating back to Augustus, the senate had become simply a sounding board of policies formulated by the princeps and his Imperial Council, which had now become the true successor of the old republican senate. Since its inception, the Council had grown in membership and now included not only many of the leading senators and equestrians, but also the best legal minds of the age—Papinian and, later, Ulpian and Paul (p. 557).

The powers of the praetorian prefect were greatly increased: he was in charge of the grain supply and was commander-in-chief of all armed forces stationed in Italy. He was also vice-president of the Imperial Council, now the supreme court of the Empire and its highest policy-making body. From 197 to 205, Severus’ senior prefect was C. Fulvius Plautianus, a kinsman from Lepcis Magna. He was a man of extreme ambition, arrogance, and cruelty, who wielded almost autocratic power because of his overpowering personality and his influence upon the emperor.

Fiscal reforms

The confiscations of property belonging to political enemies in both East and West were so enormous that Septimius created the res privata principis (the private property of the princeps). It was a new treasury department separate and distinct from the fiscus (the regular imperial treasury) and from the patrimonium Caesaris. The new treasury, administered by a procurator, gave the emperor stronger control over both the fiscal administration of the Empire and the army. Soldiers’ annual base pay was raised from 300 to 400 denarii per man. Popular with the soldiers, this increase was also necessary in order to compensate for the inflation that had raged since the reign of Commodus. The resulting need for more coins forced Severus to reduce the silver content of the denarius to about 56 percent by the end of his reign. Although that ultimately increased inflationary pressure, it temporarily produced a revival of economic prosperity and a fairly respectable surplus in the treasury.

Legal developments

Several legal developments under Severus were already implicit in those under Hadrian, especially in the jurist Julianus’ revision of the Perpetual Edict (p. 463). The major Severan reform was the already mentioned abolition of the regular standing jury courts and the transfer of their cases to the jurisdiction of the urban prefect and the praetorian prefect. Under the Severi, the practical division of the Roman citizen body into the more privileged honorable orders (honestiores) and less privileged humble people (humiliores), which had always existed to one degree or another, became even more pronounced. The honestiores included senators, equites, all local municipal magistrates, and soldiers of all ranks; the humiliores included people who did not have enough wealth to hold local offices, freedmen, and the various poor citizens of all types. The emperors sanctioned different treatment of the two classes. A privileged person might be exiled or cleanly executed, an underprivileged one sentenced to hard labor in the mines or thrown to the beasts for the same crime. Furthermore, honestiores could much more easily appeal to the emperor than could humiliores.

Provincial administration

In general, the provincial policy of Septimius Severus was a corollary to that of Hadrian and the Antonines. They had begun to make the status of the provinces equal to that of Italy. Severus continued this policy mainly because of political and dynastic motives. Disbanding the Italian Praetorian Guard, stationing a newly created legion in Italy, and appointing Near Eastern and African senators were mainly measures to consolidate his regime. Although he spent money liberally in Rome and Italy on public works, on the feeding and amusement of the Roman populace, and on the resumption of the public alimentary and educational program (which Commodus had suspended), he spent equally vast amounts in Africa and Syria. Thus, the Severan regime saw the consummation of earlier policies leading to a balance, equalization, and fusion of the various geographical and cultural elements of the Greco-Roman world under the leadership of the emperors.

At the same time, Severus had to prevent the concentration of power in the hands of provincial governors who might prove as dangerous as Pescennius Niger and Clodius Albinus. He followed the policy of Augustus, Trajan, and Hadrian and partitioned large legion-filled provinces. He divided Syria and Britain each into two separate provinces and detached Numidia from Africa to create smaller provinces and correspondingly weaker provincial governors.

Military reforms

Owing his power entirely to the soldiers and genuinely wishing to provide adequate defense, Septimius Severus made significant improvements to the army. He not only increased its size from thirty to thirty-three legions but also made army life as attractive as possible. He allowed junior officers to organize social clubs. The members all contributed money for drinks, entertainment, and financial insurance during service and after discharge. Severus legalized marriages between soldiers defending the Empire’s frontiers and native women living near forts and encampments. Thus he abolished the anomaly of long-standing but not officially countenanced marriages. The Praetorian Guard, though no longer composed solely of Italians, western provincials, and Macedonians, continued to be an elite corps drilled in the best Roman tradition and renowned as a training school for future army officers.

In his reorganization of the army, Severus began to replace more senatorial commanders with equites. They were often ex-centurions promoted from the ranks. The commanders of his three new legions were no longer senatorial legati but equestrian prefects with the rank of legatus. Some of them even became provincial governors. Severus democratized the army by making it possible for a common soldier of ability and initiative to pass from centurion on to the rank of tribune, prefect, and legatus. He might eventually reach the high office of praetorian prefect, if not emperor. Even ordinary veterans became a privileged class rewarded with good jobs in civilian posts after discharge. While raising the pay of the legionaries, he also permanently leased lands from the imperial estate to certain auxiliary units. They thus became permanent peasant militias in their sectors of the frontier.

Imperial wars and defense, 197 to 201/202 c.e.

Severus paid careful attention to military affairs because he was primarily a military man. While he let the praetorian prefect Plautianus virtually run the government, he preferred the role of imperial warrior. He gloried in conquest and supervising the frontier defenses.

The Second Parthian War, 197 to 198 c.e.

While Severus had been fighting Albinus, Vologeses IV had attacked Osrhoene (map, p. 369). After purging the senate in the early summer of 197, Septimius immediately set out for Syria and renewed war against Parthia. In conscious imitation of Trajan, he swept down Mesopotamia and sacked the Parthian captital, Ctesiphon (near modern Bagdad). He did not pursue the fleeing Parthian king but returned to Syria. From there, he rearranged the borders of the province of Osrhoene and recreated Trajan’s short-lived province of Mesopotamia from Adiabene. The great fortress city of Nisibis was its capital. Thus he greatly strengthened the eastern frontier for the immediate future. Still, he had unwittingly helped pave the way for the rise of a much greater threat twenty years later, the aggressive Sassanid Persian dynasty.

Hatra, Syria, Arabia, Palestine, and Egypt, 198/199 to 201/202 c.e.

Although Severus failed to capture the wealthy city of Hatra, he did obtain an anti-Parthian alliance with it. Then he added part of southern Syria to the province of Arabia. He divided the rest into Syria Coele (roughly modern Syria), with its capital at Antioch, in the north and the much smaller Syria Phoenice (modern Lebanon), with its capital at Tyre, in the south (maps, p. 369 and 375). He vigorously upgraded the fortifications and military roads on the desert frontier of Arabia. Syria Coele was then extended eastward to include the strategic city of Dura-Europus, which guarded the crossing of the middle Euphrates. Severus also incorporated the military forces of the formerly independent caravan city of Palmyra into the Roman army and placed it under the control of the governor of Syria Phoenice.

Late in 199, Septimius Severus entered Egypt. On the way, he had stopped in Palestine. He was favorably received there, and he granted certain unspecified privileges that gratified the Jewish population. Egypt was of special interest to him for a number of reasons. Its security as Rome’s major source of grain was vital to every emperor. In particular, Severus needed to make sure of Egypt’s loyalty in view of its earlier support of Pescennius Niger. At Alexandria, he closed the tomb of Alexander the Great. Pescennius Niger had appealed to that magical name by claiming to be a second Alexander. Severus spent some months on legal and administrative affairs. Most notably, he finally granted Alexandria and other Egyptian cities the right to have their own municipal councils like those of cities elsewhere. Also, he permitted Egyptians to become senators at Rome for the first time. The very first one was a friend of Plautianus, who was becoming more and more powerful. Severus also took a great interest in the Egyptian priests’ books of sacred lore and magic, which he then confiscated in order to prevent anyone else from obtaining their power.

Africa, 202 to 203 c.e.

After a brief return to Antioch, Severus set out for Rome. He remained there barely long enough to distribute donatives and congiaria; celebrate the wedding of Caracalla to Plautianus’ daughter, Fulvia Plautilla; and celebrate the tenth anniversary of his accession (April 9, 202) with the most elaborate games and spectacles imaginable. Then he returned to the province of Africa Proconsularis and his hometown of Lepcis Magna. He dispensed benefactions to it and other African cities and towns. If he had not done so earlier, he also made Numidia into a fully separate province from Africa Proconsularis.

Militarily, Severus made further provisions for safeguarding the frontiers of Numidia and Mauretania well into the Sahara. In early 203, he launched a major campaign deep into desert regions south of Africa Proconsularis. This campaign created a much deeper frontier to protect the rich cities of the Mediterranean coast.

Roman interlude, 203 to 207 c.e.

In the summer of 203, Severus returned to Rome for the longest stay of his reign. In that year was dedicated his great triumphal arch in the Forum, commemorating his victory in the First Parthian War. This monument, which still stands today, symbolizes the dominant role that Severus wished to play as emperor. It rests on the spot where he claimed to have had a vision that foretold his becoming emperor. This arch used to face the now-vanished one that commemorated Augustus’ diplomatic retrieval of Roman military standards and captives from the Parthians more than 200 years earlier. It symbolically towers over the Comitium (the ancient meeting place of the comitia curiata) and the senate house and is flanked by the remains of the Temple of Concord. Thus the arch both expresses Severus’ wish for harmony with the senate and the Roman populace and makes clear that it was to be on the terms of Rome’s military monarch, who had even surpassed Augustus by defeating the hated Parthians.

The rest of Severus’ time in Rome revealed problems in the imperial family and court that did not bode well for the future of the Severan dynasty. Severus’ two sons, as rivals for the throne, hated each other. They also both hated the all-powerful praetorian prefect Plautianus, to whom Severus had been loyally devoted. Plautianus had frozen their mother out of Septimius’ confidences, and Caracalla hated Plautianus’ daughter Plautilla, the wife who had been thrust upon him at fourteen. Certain revelations in 204 had undermined Severus’ confidence in Plautianus. By 205, Caracalla, now eighteen, felt confident enough to procure Plautianus’ assassination and to divorce Plautilla. Then followed a purge of Plautianus’ supporters in the senate. The appointment of the experienced commander Q. Maecius Laetus and the distinguished jurist Papinian as joint prefects of the Praetorian Guard did not disperse the atmosphere of suspicion and fear.

The war in Britain, 208 to 211 c.e.

Severus, accompanied by Julia Domna and their sons, Caracalla and Geta, spent the last years of his reign in Britain. An expedition into the heart of Scotland failed to bring the natives to battle. They resorted instead to guerrilla tactics and inflicted heavy losses on the Roman army.

Despite the losses and the apparent failure of the whole campaign, Septimius achieved important results. The display of Roman power and the thorough reconstruction of Hadrian’s Wall effectively discouraged future invasions of England from the north. Britain enjoyed almost a century of peace. Severus, however, was not to see Rome again. He died at Eburacum (York) in 211. According to Dio, he advised Caracalla and Geta on his deathbed to “agree with each other, enrich the soldiers, and despise everyone else” (Book 76/77.15.2). Probably these words are rhetorical inventions, but they are significant in their emphasis on favoring the military and their contrast with the failure of his heirs to work together.

Caracalla (211 to 217 c.e.)

With Septimius dead, Caracalla and Geta together ascended the throne. Their attempt at joint rule proved hopeless because of their long-standing mutual jealousy. Each lived in mortal dread of the other. Soon Caracalla treacherously lured Geta to their mother’s apartment and murdered him, supposedly in his mother’s very arms (see Box 27.1). Caracalla carried out a pitiless extermination of Geta’s supposed friends and supporters, among them Papinian, the jurist and praetorian prefect. To silence the murmurs of the soldiers over Geta’s killing, Caracalla increased their basic pay from 400 to 600 denarii, an expenditure that exhausted the treasury and compelled him to raise more revenue. He doubled the tax on inheritances and the manumission of slaves and continued to reduce the weight and fineness of coins. He issued a new coin, called the Antoninianus, supposedly a double denarius but actually not double in weight. He also earned the undying hatred of many nobles by continuing his father’s policy of downgrading the importance of the senate while favoring the soldiers and the provincials.

27.1 Damnatio memoriae

On some occasions when a prominent politician had been declared an enemy of the state by the senate and then killed, the Romans further subjected him to what is referred to by modern scholars as damnatio memoriae (the condemnation of his memory). Caracalla, with impressive thoroughness, made sure that such memory sanctions were applied to his brother Geta after his death.

Damnatio memoriae took different forms over the course of Roman history. It could include a ban on the condemned man’s name being given to any of his descendants, the destruction of his house, and the confiscation of his property. Emperors could suffer the indignity of having their decrees revoked. More striking to us now are the visible efforts to mutilate all physical reminders of the condemned: simple removal was not enough. Geta’s name has been chiseled out of numerous inscriptions from across the whole of the Empire, and his portrait busts, statues, and painted images were intentionally damaged with hammers and other implements. Our sources report that Caracalla melted down coins that Geta had minted. On a few surviving coins that originally bore his image, Geta’s face has been scratched off.

Caracalla, the new emperor’s commonly used nickname, came from a long Gallic cape that he used to wear. He was a fairly good soldier and strategist and had some shrewd political instincts. The most historic act of his reign was the promulgation of the Constitutio Antoniniana in 212 to extend citizenship to all free inhabitants of the Empire. This action was in keeping with his father’s policy of reducing the privileged position of Italy and the old senatorial elite. By this legislation, Caracalla obliterated all distinction between Italians and provincials, between conquerors and conquered, between urban and rural dwellers, and between those who possessed Greco-Roman culture and those who did not. There may also have been some hoped-for advantages in terms of a unified legal system, increased availability of recruits for the Roman army, uniform liability for paying taxes, and even a shared state religion, all difficult matters to decide.

Another manifestation of Caracalla’s shrewdness was his proposal of marriage to the daughter of Artabanus V of Parthia. If he was serious, he may have hoped to unite the two great powers against the less civilized tribes beyond the frontiers. It is difficult, however, to see how either the Roman or Persian aristocracy would have tolerated such an arrangement. He may only have been looking for an excuse to go to war.

German and Parthian wars

Attempts at diplomacy notwithstanding, Caracalla spent the major part of his reign fighting wars. He proved himself a real soldier emperor. In 213, he proceeded to the Raetian border to attack the Alemanni. They were a formidable but newly organized confederacy of mixed resident and displaced Germanic tribes. They had migrated westward and settled along the right bank of the upper Rhine. After decisively defeating them at the river Main, Caracalla built and restored forts, repaired roads and bridges, and extended a 105-mile stone wall from six to nine feet high and four feet thick along the Raetian frontier. The latter successfully withstood numerous assaults for the next twenty years.

After similarly strengthening the defenses in Pannonia and along the lower Danube, Caracalla proceeded to the East. He brutally suppressed an uprising in Alexandria and resumed war against Parthia since his proposal to unite the two empires by marriage had been rejected. In 216, he marched across Adiabene (northern Assyria) and invaded Media. After sacking several fortified places, he withdrew to winter quarters at Edessa (Urfa) in Osrhoene. There he made preparations to mount a more vigorous offensive the following spring. He did not live to witness the consummation of his plans. On April 8, 217, while traveling from Edessa to Carrhae to worship at the Temple of the Moon, he was stabbed to death at the instigation of the praetorian prefect M. Opellius Macrinus (map, p. 369).

Macrinus (217 to 218 c.e.)

As ringleader of the plot against Caracalla, Macrinus secured the acclamation of the army and ascended the throne. He was a Mauretanian by birth, an eques in rank, and the first princeps without prior membership in the senate to reach the throne. To affiliate himself with the Severan dynasty, he adopted the name of Severus, bestowed that of Antoninus upon his young son Diadumenianus, and even ordered the senate to proclaim Caracalla a god. Realizing that he needed some military prestige to hold the loyalty of the army, he continued the war with Parthia but proved to be a poor general. After a few minor successes and two major defeats, he lost the respect of the army by agreeing to surrender his prisoners and to pay Parthia a large indemnity. This inglorious settlement, together with his unwise decision to reduce the pay for new recruits and the opposition of Severus’ family, ultimately cost him his life and throne.

Powerful Syrian empresses

Through marriage to Julia Domna, Septimius Severus had been connected to a family of remarkable Syrian women. They actively sought a leading role in imperial politics. Julia Domna, and her sister, Julia Maesa, were well educated, shrewd, and tough. Their father was the high priest of the sun god Elagabalus (Heliogabalus) at the Arabian city of Emesa (Homs, p. 379) in Syria. He probably was descended from its old royal house. Women of the family were accustomed to power and influence. Domna had enjoyed great importance at the beginning of Severus’ reign but had been outmaneuvered for a time by the ambitious praetorian prefect Plautianus. She had then devoted herself to creating a circle of influential intellectuals. She was able to recover her former strength after the fall of Plautianus. Indeed, she had probably contributed to it through Caracalla. In 208, she had accompanied Severus to Britain. After his death, she had tried to promote the interests of her more even-tempered son, Geta. Failing to prevent his murder, she had made the best of it with Caracalla. She accompanied Caracalla to Antioch on his Parthian expedition in 215 and died there soon after his assassination. Macrinus then forced her sister, Maesa, to retire to Syria.

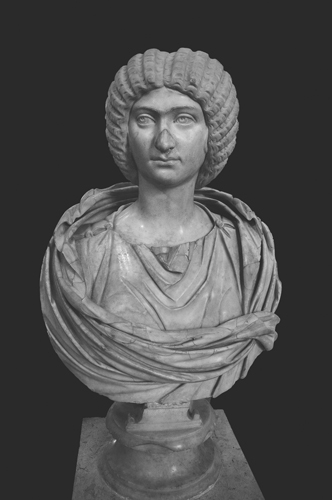

FIGURE 27.1 Empress Julia Domna, wife of Septimius Severus.

In Syria, Maesa plotted to restore her family’s imperial fortunes. She had gone back to Emesa with her two daughters, Julia Soaemias and Julia Mamaea. There, Varius Avitus, the fourteen-year-old son of Soaemias, had inherited the high priesthood of the sun god Elagabalus, and he himself came to be known by that name as emperor.

Elagabalus (218 to 222 c.e.)

Knowing how the army cherished the memory of Caracalla, Maesa concocted the rumor that Elagabalus was the natural son of Caracalla and, therefore, was a real Severus. She presented him to the legions of Syria. Persuaded by the offer of a large donative, they saluted him as emperor under Caracalla’s royal name, Marcus Aurelius Antoninus. Macrinus, deserted by most of his troops and defeated in battle, fled. He was later hunted down and killed.

A year later, wearing a purple silk robe, rouge on his cheeks, a necklace of pearls, and a bejeweled crown, Elagabalus arrived in Rome. He had brought from Emesa a conical black stone—the cult image of the god Elagabalus—which he enshrined in an ornate temple on the Palatine and worshiped with un-Roman sexual practices (which probably have been exaggerated in the retelling by hostile and sensationalistic sources) and outlandish rites to the accompaniment of drums, cymbals, and anthems sung by Syrian women. What shocked the Roman public even more than any of these strange rites was his endeavor to make that Syrian sun god the supreme deity of the Roman State.

In order to devote more time to his priestly duties and (in Roman eyes) scandalous ceremonies, Elagabalus entrusted most of the business of government to his grandmother. He also appointed his favorites to the highest public offices—a professional dancer, for example, as praetorian prefect; a charioteer as head of the night watch (vigiles); and a barber as prefect of the grain supply (annona). Maesa realized that the un-Roman conduct of Elagabalus would lead to his downfall and the ruin of the Severan family. She tactfully suggested that he ought to adopt Gessius Bassianus Alexianus, her grandson by Julia Mamaea, as Caesar and heir to the throne. When Elagabalus saw that Alexianus, whom he adopted under the name of Marcus Aurelius Severus Alexander, was preferred by the senate and the people, he regretted his decision and twice attempted to get rid of the boy.

Maesa and Mamaea appealed to the Praetorian Guard. The guardsmen were happy to hunt down Elagabalus and his mother, Soaemias. They seized the two in their hiding place—a latrine—cut off their heads, and dragged the corpses through the streets to the Aemilian bridge. There they tied weights to them and hurled them into the Tiber.

Severus Alexander (222 to 235 c.e.)

The accession of Severus Alexander was greeted with rejoicing. Although he was studious, talented, and industrious, he was only fourteen, and his capable mother, Mamaea, held the reins of power. She was virtually, even to the end of his reign, the empress of Rome.

The reign of Alexander marked the revival of the prestige, if not the power, of the senate. Mamaea enlisted its support in order to strengthen the arm of the civil government in controlling the unruly and mutinous armies. She accordingly set up a council of sixteen prominent senators to exercise at least a nominal regency, though actually, perhaps, to serve only in an advisory capacity. Among the sixteen senators were the imperial biographer Marius Maximus and the historian Cassius Dio (p. 556). Senators also probably held a majority in the enlarged Imperial Council. The president of both councils was the praetorian prefect. He was normally of equestrian rank but was now elevated, while in office, to senatorial rank. Accordingly, he could sit as a judge in trials involving senators without impairing the dignity of the defendants. At this time, the praetorian prefect was the distinguished jurist Domitius Ulpianus. Thus the new regime not only enhanced the dignity of the senate but also enlarged the powers of the praetorian prefect at the expense of the old executive offices. Under Severus Alexander, the tribunes of the plebs and aediles ceased to be appointed.

Social and economic policy

The government seems to have tried to win the goodwill and support of the civilian population by providing honest and efficient administration. It reduced taxes and authorized the construction of new baths, aqueducts, libraries, and roads. It subsidized teachers and scholars and lent money without interest to enable poor people to purchase farms. One major reform was the provision of primary-school education all over the Empire, even in the villages of Egypt. Another was the legalization, under government supervision and control, of all guilds or colleges (collegia) having to do with the supply of foodstuffs and essential services to the city of Rome. Under this category fell wine and oil merchants, bakers, and shoemakers. In return, the guilds enjoyed special tax favors and exemptions and the benefit of legal counsel at public expense.

The military problem

The fatal weakness of Alexander’s regime was its failure to control the armies. In 228, the Praetorian Guard mutinied. The praetorian prefect, Domitius Ulpianus, was murdered in the emperor’s palace itself because he was too strict. The soldiers in Mesopotamia mutinied and murdered their commander. Another excellent disciplinarian, the historian Cassius Dio, would have suffered the same fate had not Alexander whisked him off to his homeland of Bithynia.

Never had the need for disciplined armies been greater. Rome’s recent wars with Parthia had so weakened the decrepit Arsacid regime that it was overthrown between 224 and 227 by the aggressive Sassanid dynasty of Ardashir (Artaxerxes) I (224–241 c.e.) and his son Shapur (Sapor) I (241–272 c.e.). They sought to reestablish the old Persian Empire of the Achaemenid dynasty (ca. 560–330 b.c.e.). By 331, Ardashir had already overrun Mesopotamia and was threatening the provinces of Syria and Cappadocia. After a futile diplomatic effort, Alexander himself had to go to the East. He planned and executed a massive three-pronged attack that should have ensured a decisive victory. Because of poor generalship and excessive caution, it resulted only in heavy losses on both sides. It produced nothing more than a stalemate at best. Alexander returned to Rome to celebrate a splendid but dubious triumph in 233.

Meanwhile, the Alemanni and other German tribes had broken through the Roman defenses and were pouring into Gaul and Raetia. Accompanied by his mother, Alexander hurried north in 234. After some early successes, he followed his mother’s suggestion and bought peace from the Germans with a subsidy. His men were disgusted. They would have preferred to use some of that money for themselves. They mutinied in 235 under the leadership of the Thracian Gaius Iulius Verus Maximinus (Maximinus Thrax), commander of the Pannonian legions. Alexander and his mother were both killed.

Thus, the mutineers terminated the Severan dynasty. They also ushered in almost a half century of civil wars. Those wars were usually connected with such problems as Severus Alexander had faced on the frontiers of the Empire.

Suggested reading

Birley , A. R. Septimius Severus the African Emperor. 2nd ed. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1988.

Hekster , O. Commodus: An Emperor at the Crossroads. Amsterdam: J.C. Gieben, 2002.

Icks , M. The Crimes of Elagabalus: The Life and Legacy of Rome’s Decadent Boy Emperor. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2012.