Chapter 30

In Roman history, the fourth century c.e. is often reckoned from the acclamation of Diocletian as emperor in 284 to the death of Theodosius in 395. The real turning point between the third and the fourth centuries, however, is the death of Carinus in 285. Only then did the unprecedented barrage of political, military, and natural disasters characterizing the third century begin to lose intensity in the face of Diocletian’s subsequent actions.

The gigantic mobilization required to meet Rome’s difficulties over the third century had furthered the trend toward an absolute military monarchy that can already be seen with Commodus and Septimius Severus. Under Diocletian, the Principate gave way completely to the Dominate. The term comes from dominus, “lord and master,” which was synonymous with an absolute monarch and was now used in public documents to refer to the emperor. Diocletian instituted sweeping military, administrative, and fiscal reforms to ensure the survival of the Roman Empire united under his command as the senior of four ruling partners, tetrarchs, who formed the Tetrarchy.

Sources for Roman history during the fourth century c.e.

The latter part of the fourth century c.e. is one of the best documented periods in Roman history. Unfortunately few major pagan or Christian writers cover Diocletian’s crucial reign at the century’s start. The pagan Greek historian Zosimus (p. 707) portrayed Diocletian very favorably in his New History (ca. 500 c.e.), but the sections that cover Diocletian’s reign in detail are missing. On the other hand, the rest of the narrative, which is very biased against Constantine and the Christians, is complete. The excellent History (or Res Gestae) written in Latin by the pagan historian Ammianus Marcellinus is missing the part that covers Diocletian, Constantine, and Constantine’s sons up to 353, but it is extant for the period from 353 to 378 (p. 634). Quintus Aurelius Symmachus, a staunch pagan upholder of senatorial tradition at Rome, has left a major body of letters. They provide valuable insights into the world of well-connected Roman aristocrats (pp. 633–4). The works of the Neoplatonist Iamblichus and Eunapius’ Lives of the Philosophers and Sophists also shed much light on the time and its people (p. 635).

The letters and poems of Ausonius, a Gallo-Roman aristocrat and rhetorician, illustrate the life of the increasingly Christian elite of the western provinces (pp. 634–5). Themistius, a pagan philosopher and rhetorician, and other skilled orators produced numerous panegyrics on Constantine and members of his dynasty (p. 636). The voluminous letters and speeches of the great pagan Greek rhetorician Libanius of Antioch shed light on many personalities and events during the second half of the fourth century (p. 636). The letters and essays of Julian the Apostate, the former Christian who tried to restore the primacy of paganism when he became emperor, are very helpful for his lifetime (p. 635).

Historical writings of secondary importance include the biography of Diocletian at the close of the Historia Augusta and several fourth-century breviaria, brief historical surveys of Roman history, the last parts of which are of real value since they record events of the authors’ own time (p. 634). A number of interesting fourth-century technical treatises and handbooks on grammar, rhetoric, geography, medicine, and military affairs have also survived.

The surviving works of Christian thinkers and churchmen from the fourth century are very extensive. They are full of quotations from otherwise lost documents, such as imperial statutes and edicts, proceedings of Church councils, imperial correspondence, and letters written by bishops and other ecclesiastical officials. Their biases are obviously counter to those of strongly pagan authors and often involve partisan or theological controversies within the Church as well. One of the best, but most biased, Christian writers is Lactantius (ca. 240–ca. 325). Aside from his doctrinal works, important for understanding the evolution of Christian thought, his Latin tract On the Deaths of the Persecutors presents a hostile view of the policies and personalities of Diocletian and those with whom he shared power (p. 637). The works of the Greek bishop Eusebius of Caesarea are important despite their obvious favoritism: versions of his Chronicle and his Ecclesiastical History mentioned earlier (p. 638), his Life of Constantine (unfinished), and the Praise of Constantine (with the Tricennalian Oration, which celebrates Constantine’s thirtieth anniversary as emperor) are invaluable. Other Greek histories of the Church are those of Theodoret, Sozomen, and Socrates, which end in 408, 425, and 439, respectively (p. 707). Many other great churchmen writing in both Greek and Latin provide a wealth of material for all aspects of history in the latter half of the fourth century through their histories, biographies, letters, sermons, and doctrinal writings (pp. 637–8).

Other sources include inscriptions, papyri, coins, archaeological materials, and especially imperial statutes (constitutiones 1). The latter are preserved in numerous documents: inscriptions, papyri, various juristic and literary works, the Theodosian Code (published in 438 during the reign of Theodosius II, 408–450), and the Justinian Code (first published in 529 during the reign of Justinian I, 527–565). The three most important inscriptional texts are Diocletian’s famous Edict on Maximum Prices, his Currency Edict, and the great Paikuli inscription of Narses I of Persia (293–302), who recounted his triumphs and the acts of homage paid him by Roman envoys and the vassal kings of Asia.

An important document is the Laterculus of Verona. It lists the provinces created under Diocletian’s reorganization of the Empire. Another major document is the Notitia Dignitatum (List of Offices), an apparently official, illustrated register of military units and their postings throughout the provinces. As it stands, it comes from the western half of the Empire after the division that prevailed from 395 onward, but the information on the East is earlier. Because it reflects the ideal of stated policy, it does not necessarily represent actual practice. It must be used with caution when trying to determine what was really happening at any particular moment.

The archaeological evidence for the fourth century is enormous. Diocletian and his co-emperors, then Constantine and Constantine’s heirs, spent prodigiously on building in Rome, Constantinople, and other important cities where emperors frequently resided, such as Trier, Milan, Sirmium, Nicomedia, and Antioch. Fortifications, camps, guard stations, and signal posts were constructed all over the Empire. The elite spent huge sums on building and expanding rural villas as they focused more and more on a self-sufficient life in the countryside. Christians built shrines, monasteries, and major urban churches with great fervor after persecution ended early in the century and official support began.

The rise of Diocletian

The humbleness of Diocletian’s origins has been exaggerated by hostile or overly dramatic sources. One of a series of talented, well-trained officers from the Danubian provinces, he probably came from a relatively well-to-do provincial family. He had been a cavalryman under Gallienus, a dux, or cavalry commander, in Moesia, and a commandant of the imperial mounted bodyguard. His excellent military record is nevertheless overshadowed by his career as an organizer, administrator, and statesman. He inspired excellent advisors and generals to assist him loyally in restoring stability to the Empire.

The chief military and political problems facing Diocletian were the strengthening of the power and authority of the central government, the defense of the frontiers, the recovery of the rebellious and seceding provinces, and the removal of those conditions that favored constant attempts to seize the throne. Diocletian’s first act was to find a loyal representative who could take over the defense of the West and permit him to concentrate his energies on the protection of the threatened Danubian and eastern frontiers. Such a loyal representative would convince the western legions of his concern for western problems and would lessen the danger of revolt. His choice fell upon Maximian, an old comrade in arms, whom he elevated to the rank of Caesar and sent to Gaul.

In Gaul, Maximian quickly crushed a rebellion of desperate peasants (the Bacaudae) and drove out the Germans into the region east of the Rhine. In recognition of these victories, Diocletian raised Maximian to the rank of Augustus in 286. Maximian was to rule jointly with Diocletian and to be second only in personal prestige and informal authority.

Maximian had not been so successful at sea. To clear the English Channel and the North Sea of the Frankish and Saxon pirates who had been raiding the shores of Gaul and Britain, he established a naval base at Gesoriacum (Bononia, Boulogne) on the coast of Gaul and placed Marcus Aurelius Carausius in command of the Roman fleet. Carausius, a native of the German lowlands and an experienced and daring sailor, overcame the pirates within a few weeks. Then, he ambitiously enlarged his fleet with captured pirate ships and men, seized Gesoriacum and Britain, and conferred upon himself the title of Augustus. Diocletian was too occupied to do more than protest and Maximian’s fleet was wrecked at sea. Carausius maintained undisturbed sway over Britain for seven years as Emperor of the North.

In the East, however, Diocletian successfully displayed Roman might on the Danube and the Euphrates. Between 286 and 291, he repelled invasions and strengthened frontier defenses. In 287, successful negotiations with the Persian King Bahram (Vahram, Varahan, Varanes) II (276–293) obtained Persian renunciation of claims to Roman Mesopotamia and recognition of Rome’s ally Tiridates “III” (261–317) as the legitimate king of Armenia.

The Tetrarchy: a new form of Imperial rule, 293 to 312 c.e.

In order to strengthen imperial control of the armies and forestall usurpers such as Carausius, Diocletian resolved in 293 to create the four-man ruling committee known as the Tetrarchy. Two Caesars were to be appointed to serve as junior emperors and successors to two Augusti. One would serve under Diocletian, the Augustus in the East, the other under Maximian, the Augustus in the West. Diocletian selected Gaius Galerius, another Danubian officer and a brilliant strategist, as his Caesar. Maximian’s choice was yet another Danubian, C. Flavius Julius Constantius, commonly called Chlorus or “Pale Face,” who proved himself an excellent general, a prudent statesman, and the worthy father of the future Constantine the Great.

The Tetrarchy was held together by the personality and authority of Diocletian, the senior Augustus. It was doubly strengthened by adoption and marriage. Each Caesar was the adopted heir and son-in-law of his Augustus. Diocletian’s daughter, Valeria, married the Caesar Galerius. Maximian’s daughter (or stepdaughter) Theodora was already married to the Caesar Constantius. Also, Maximian’s son, Maxentius, married Galerius’ daughter, Valeria Maximilla.

On the death or abdication of an Augustus, his Caesar, as his adopted son and heir, supposedly would take his place. The new Augustus would, in turn, select a new Caesar. The Tetrarchy was indivisible in operation and power: laws were promulgated in the names of all four rulers, and triumphs gained by any one of them were acclaimed in the name of all. On the other hand, each member of the Tetrarchy had his own separate court and bodyguard and had the right to strike coins bearing his own image and titulature.

Each Augustus and Caesar oversaw those provinces and frontiers that he could conveniently and adequately defend from his own headquarters. Maximian protected the upper Rhine and upper Danube from Mediolanum (Milan) and Aquileia in Italy. Constantius shielded the middle and lower Rhine, Gaul, and later Britain from Augusta Treverorum (Trèves, Trier) in Gaul. Galerius seems initially to have guarded the Euphrates frontier, Palestine, and Egypt from Antioch in Syria (293–296) and then the lower Danube and the Balkans from Thessalonica (Salonica, Thessaloniki, Saloniki) in Macedonia and Serdica in Thrace (299–311). For most of his first ten years, Diocletian oversaw the middle and lower Danube and Asia Minor from his bases at Sirmium on the Save River and Nicomedia on the Sea of Marmara (Marmora, Propontis); from 299 to 302, he looked after affairs in Asia Minor, the Levant, and Egypt from Antioch and then from Nicomedia (302–305).

The Tetrarchy in action

While Diocletian held the reins of power, the Tetrarchy fully justified his expectations. Each of the four rulers set about restoring peace and unity in his own part of the Empire. Constantius weakened Carausius by capturing the port of Gesoriacum (Bononia, Boulogne) and defeating his German allies. In 293, a treacherous rival assassinated Carausius, and, in 296, Constantius successfully reestablished Roman rule in Britain. Returning to the Continent, he strengthened the fortifications along the Rhine frontier and established a long period of peace after a spectacular victory over the Alemanni in 298.

The activities of Diocletian and Galerius in the East are poorly documented, but recent research supports the following outline. Between 293 and 296, Diocletian waged a series of successful campaigns against the tribes along the lower Danube. He restored Roman defenses in the area while events in Persia and Egypt occupied Galerius’ attention. In Persia, a new king, Narses (293–302), overthrew Bahram II and began to subvert the treaty of 287. He also promoted the religious beliefs of the Manichees (pp. 550–1), whose missionary activities raised Roman suspicions. At the same time, Egypt was being disturbed by the raids of the Blemmyes from the Sudan. They could no longer be left unchecked. Galerius probably spent all of 294 and the first few months of 295 in Egypt in order to drive out the Blemmyes and strengthen Egypt’s defenses.

Meanwhile, Narses was causing increasing alarm on the Euphrates frontier. By the fall of 296, hostilities could no longer be avoided. Narses had driven Tiridates III out of Armenia and was poised to strike at Roman territory. Diocletian brought reinforcements from the Danube and guarded the Euphrates. Galerius rushed off to intercept Narses. The latter won an initial victory. Galerius, with significant help from his wife, Valeria, obtained enough reinforcements and resources to turn the tables in the following year. He captured the king’s harem, regained control of Mesopotamia, and seized the strategic fortress of Nisibis as well as the Persian capital of Ctesiphon (map, p. 379).

While Galerius was fighting Narses, tax increases precipitated a serious revolt in Egypt under the leadership of Domitius Domitianus and Aurelius Achilleus.2 Diocletian brought an army from Syria in mid-297 and besieged Alexandria for eight months. After subduing the whole of Egypt during the rest of 298, he returned to join the victorious Galerius at Nisibis for the final peace negotiations with Narses.

Narses had to accept harsh peace terms in order to get back his wives and children. He agreed to surrender Mesopotamia, which now extended to the west bank of the upper Tigris, and five small provinces east of the Tigris. He acknowledged Greater Armenia and the kingdom of Iberia south of the Caucasus as Roman protectorates. He also agreed that merchants traveling between the Roman and Persian empires must pass through the Roman customs center at Nisibis. The victory of Galerius was so complete that the Persians did not risk war with Rome for another fifty years.

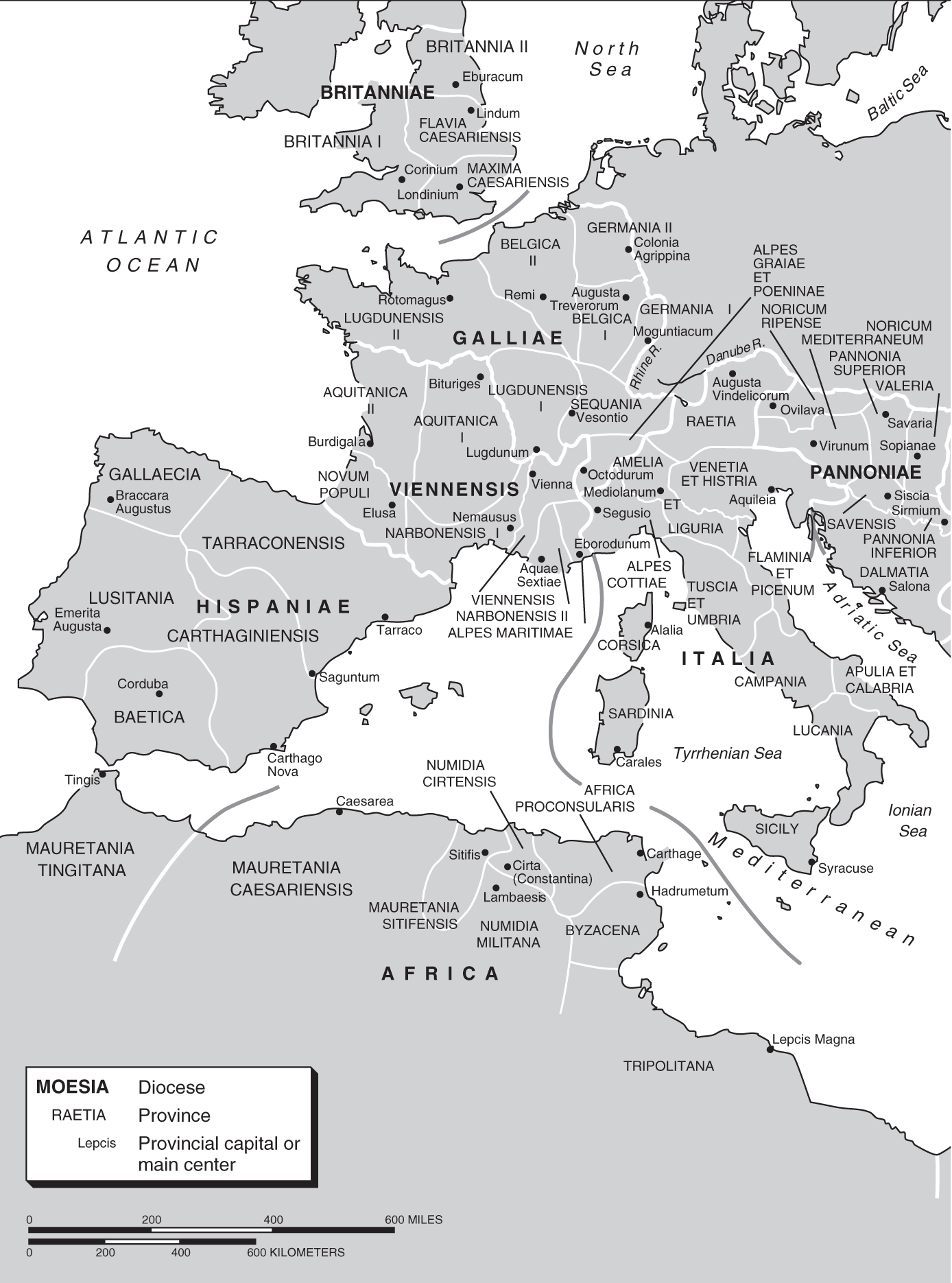

FIGURE 30.1 The dioceses and provinces of the Roman Empire in 314 c.e.

The creation of the Tetrarchy had been fully justified. Constantius was victorious in the West and Galerius had secured the East. Strong defenses existed around the Empire: in Britain, along the Rhine, Danube, and Euphrates rivers; in Mesopotamia; and in Egypt. Captured invaders had become settlers who helped to repopulate and defend lands adjacent to the frontiers. That four-headed, seemingly decentralized, but actually united, power gave Rome twenty years of stable rule.

Diocletian’s other initiatives

In addition to establishing the Tetrarchy and consolidating the military defenses of the Empire, Diocletian brought to fulfillment growing changes in almost every department of the government. These changes were not the innovations of a radical but rather the continuation and strengthening of the trends that had been developing in the shift toward absolute monarchy.

Exalting the emperor

Diocletian went much further than previous emperors in attempts to exalt the emperor above ordinary mortals. He surrounded himself with an aura of such power, pomp, and sanctity that any attempt to overthrow him would appear not only treasonous but also sacrilegious. Diocletian assumed the title of Jovius as Jupiter’s earthly representative sent to restore the Roman Empire. He bestowed on his colleague, Maximian, the name of Herculius as the earthly analog of Hercules, son and helper of Jupiter. Together they demanded the reverence and adoration due to gods for the Jovian and Herculian dynasties that they had founded. Everything about them was sacred and holy: their palaces, courts, and bedchambers. Their portraits radiated a nimbus or halo, an outer illumination flowing from an inner divinity.

Diocletian adopted an elaborate court ceremonial and etiquette, not unlike that prescribed at the royal court of Persia. He became less accessible and seldom appeared in public. When he did, he wore the diadem and carried the scepter. He arrayed himself in purple and gold and sparkled with jewels. Those to whom he condescended to grant an audience had to kneel and kiss the hem of his robe. This act of adoration was incumbent also upon members of the Imperial Council (consilium), which acquired the name of Sacred Consistory (sacrum consistorium) from the necessity to remain standing (consistere) while in the imperial presence.

Provincial administration

To increase the control of the emperor and prevent ambitious governors from amassing too much power, Diocletian completely reorganized the administrative system. Following a trend initiated by Septimius Severus, he completed the abolition of Italy’s privileged status and divided it into a dozen provinces. In addition, by subdividing the old provinces, he increased the total number of provinces from about 40 to about 105 (map, pp. 570–1). He also deprived most governors of their former military functions.

The new provinces were grouped into twelve administrative districts known as dioceses. Each diocese was subject to a vicar (vicarius) of equestrian rank. He supervised all governors, even those of senatorial rank except the three senior senatorial governors: the proconsuls of Africa, Asia, and Achaea. Like all governors (except those of Isauria in Asia Minor and Mauretania in North Africa), the vicars were civilian officials whose main function was the administration of justice and supervision of tax collection. The dioceses, in turn, were grouped into four prefectures: Gaul and Italy in the West, Illyricum and the Orient in the East. A praetorian prefect supervised the vicars in each prefecture and reported directly to the tetrarch who resided at the headquarters of that prefecture.

Diocletian assigned command over the armies and garrisons stationed in the provinces to professional military men known as dukes (duces). To ensure close supervision and the mutual restraint of ambitious impulses, he made the dukes dependent on the governors and other civilian officials for military supplies and provisions. In some dioceses, several dukes might serve under the command of a higher officer known as a comes (companion, count).

Military reforms

During the third century, Rome’s system of frontier defense had essentially collapsed. In the latter part of the century, Gallienus and his capable Illyrian successors surrendered control of the Empire’s eastern and western periphery and concentrated on holding its central core. After they checked the attacks of outsiders against the core, they regained effective control over the periphery. Diocletian represents the culmination of this process. Having regained political and military control within the territory of the Empire, Diocletian instituted military reforms to restore frontier defenses.

Although not all of the details are clear, Diocletian’s reforms represent the reestablishment of Rome’s traditional defensive strategy. Tactical and organizational changes plus a huge increase in manpower simply made it more effective. First of all, Diocletian increased the size of Roman military forces (infantry, cavalry, and naval, both regular and auxiliary) by as much as 100,000 men to a total of around 500,000. He probably kept the official manpower of individual legions at around 5500. Tactically, however, he spread out the legions and the other forces in numerous smaller detachments. Some manned small, heavily constructed forts and guard posts along roads and supply routes in frontier zones. Others served as easily mobilized forces billeted in strategically located fortified cities and towns within the frontier provinces. In this way, the army could guarantee the safe acquisition, transportation, and storage of supplies. It could also protect communications in general, sound the alarm when any sector of the frontier was attacked, and quickly bring up mobile forces as needed.

There is no major shift in Roman defensive strategy here. The fortified roads were built in forward areas to provide protective zones for the provinces proper. That fits a pattern going all the way back to Augustus. Units stationed in the rear performed the same function as those once stationed in large legionary camps. It was easier, however, to supply them by stationing smaller detachments in various cities and towns. Furthermore, the dispersal of provincial troops in small units made it more difficult for provincial commanders to win over large numbers of troops quickly for a rebellion.

The tetrarchs commanded armies large enough to meet major emergencies along the most vulnerable frontiers. Each of the four controlled a different prefecture from his strategically located headquarters. Constantius kept an eye on the Rhine from Trier; from Milan, Maxentius could defend the Agri Decumates, the dangerous triangle formed by the upper reaches of the Rhine and Danube rivers; Galerius guarded the rest of the Danube from Sirmium; and Diocletian protected the eastern frontiers from Nicomedia in Bithynia. With each tetrarch were highly mobile troops, especially cavalry. They constituted his comitatus (personal escort) and formed the nucleus of the large field armies that would be assembled from smaller provincial units where and when they were needed.

Recruiting enough soldiers for Diocletian’s expanded army was a real problem. Conscription had fallen into disfavor, and the government could not afford to call too many men away from most occupations in any case. Diocletian employed conscription cautiously, enforced hereditary military obligations, utilized voluntary enlistment, and hired foreign mercenaries.

To make sure that imperial armies were adequately armed and equipped, Diocletian instituted or expanded a system of state-owned workshops (fabricae) that produced directly for the military. Those located near sources of iron ore in Asia Minor specialized in armor or weapons. Some were located in strategic western cities such as Sirmium, Salona, and Ticinum. A number of shops produced cloth or leather, which other shops turned into clothing, headwear, and footwear (p. 608).

The reform of the coinage, 286 to 293 c.e.

Diocletian attempted to end the frightful monetary chaos and inflation of the late third century by reforming the Roman coinage. His system of silver and gold coinage, though not a long-term success itself, served as a model for his successors. In 286, he began to replace the old aureus with a new gold coin at the rate of sixty to the standard Roman pound of 327.45 grams (12 Roman ounces, 11.536 ounces avoirdupois [English/U.S.]). By 301 at the latest, this gold coin was known as the solidus (pl. solidi). In 293, Diocletian introduced a silver coin, the argenteus, at ninety-six to the pound and roughly equivalent to the old denarius of Nero’s time. To answer the need for small change, he struck three denominations: a new copper denarius of less value than the old silver one, a silver-washed copper piece worth two new denarii, and a more heavily silvered bronze nummus worth five new denarii. Despite these changes, Diocletian was unable to mint enough good gold and silver coins to satisfy the government’s needs, and the new copper denarius and the two billon (silver-coated base metal) coins were issued in huge numbers that only added to inflation.

The Edict on Maximum Prices, 301 c.e.

Unfortunately, Diocletian’s administrative and military reforms also added fuel to the inflationary fires of the time. When he increased the number of provinces from about 40 to about 105 and created separate military commanders and civilian governors for each, he increased the number of highly salaried provincial officials fivefold. On top of that, he added the four praetorian prefects and twelve vicarii and all their staffs. The creation of various new imperial residences for the four tetrarchs, the building of frontier forts and roads, and monumental building programs in Rome entailed even more expense. Between 150 and 300, the basic rate of military pay had increased sixfold. By increasing the number of soldiers by somewhere between one-fourth and one-third and by giving donatives at regular intervals throughout the year, Diocletian raised the government’s cost for manpower and supplies even more.

Diocletian made the situation even worse in early 301 by issuing his famous Edict on Maximum Prices, one of the most valuable Roman economic documents available. It has been reconstructed from numerous fragmentary Greek and Latin inscriptions largely in the eastern part of the Empire but more recently also in Italy. It set a ceiling on the prices of over a thousand different items from wheat, barley, rice, poultry, vegetables, fruits, fish, and wines of every variety and origin to clothing, bed linen, ink, parchment, and craftsmen’s wages.

In a remarkable preamble to the edict, Diocletian sharply condemned speculators and profiteers who robbed the helpless public. He was particularly concerned about the purchasing power of soldiers, who had little other than money to exchange in the marketplace. The penalty for those who overcharged was death. With the prices for goods and services fixed and the value of money falling, it became unprofitable to sell goods at the official prices. Therefore, people either refused to produce goods, sold them illegally on black markets, or simply relied on barter, which had always played a strong role in the everyday economy, particularly for the countryside. In the face of economic realities, the edict had to be relaxed to encourage production and the availability of goods for sale in markets. The edict had become largely a dead letter by the end of Diocletian’s reign.

Tax reform

In order to meet the increased needs of the government and reduce the effects of inflation on the imperial budget, Diocletian instituted a thorough rationalization of the tax system. He made it more efficient and dependable. He did away with many taxes. His new system relied on two basic types of taxes that had traditionally been used throughout the ancient Mediterranean world, the land tax and the poll (head) tax. It was also traditional that many taxes were paid in kind, that is, in the form of agricultural products (such as grain, oil, wine, and meat) or manufactured goods (such as cloth, leather, tools, building materials, and arms). They provided the annona, by which the emperors fed, clothed, and equipped the armies; paid the soldiers and government officials; and sustained the poorer residents of Rome. What Diocletian tried to do was regularize these traditional practices on an empire-wide basis.

Under his system, agricultural labor and land were taxed according to certain standard units. The system for assessing labor is usually referred to as capitatio and that for land as iugatio. They are derived, respectively, from caput (pl. capita), “head,” and iugum (pl. iuga), “yoke” (the amount of land that could be plowed in a day with a yoke of oxen). Theoretically, all of the land throughout the Empire was divided into iuga, which varied in size with the types of crops grown and the quality of the soil. All agricultural labor, human and animal, was reckoned in capita, with women and young teenagers being counted at half the value of men and with draft animals proportionally lower. The property owner was then assessed at so many capita and so many iuga. Every five years until 312 and then every fifteen thereafter, a new assessment, called an indictio (indiction), would be made. Thus, the term indictio came also to be used for the period of time that the assessment was in force. For each year during an indiction, the government would calculate how much food, material, and labor it would need and divide those amounts by the total number of units to find out how much would have to be collected per unit from each property owner.

On paper, this system looks like the soul of simplicity and fairness. In practice, however, it was not. Surviving documents show that sometimes taxes in kind were converted to taxes in gold solidi. There was also great variation in the terminology actually used and even in the meaning of the same term. In some cases, caput may refer to the labor equivalent of one adult male. In other cases, caput may be interchangeable with iugum and represent the amount of labor needed per iugum. Figures from one estate indicate that such a caput may be equivalent to the labor of twelve and one-half adult males. In southern Italy, land was assessed in units of fifty Roman iugera called millenae (sing. millena), and in North Africa, the centuria of 200 iugera was the standard unit. If, as has been argued, the standard iugum equaled twelve and one-half Roman iugera, then the millena and centuria can easily be divided into four and sixteen iuga, respectively, but certainty is impossible.

Moreover, it is not reasonable to expect complete consistency in so vast an empire as Rome’s, with its strong regional differences and traditions. Insofar as Diocletian did not include provisions for taxing merchants and craftsmen, his system was unfair to the owners of agricultural land. Also, although rural landowners were supposed to be taxed in proportion to what they owned, there were many inequities and injustices in the way in which assessments were actually made and taxes collected. It was always easier for the wealthy landowners, who were responsible for collecting the taxes at the local level, to shift a disproportionate share of the tax burden onto the poor through dishonesty and extortion.

The great virtue of Diocletian’s system was that it gave taxpayers relief from the totally unexpected and unregulated ad hoc requisitions characteristic of the late third century. It also provided the government with a dependable source of supply that did not rely on the government’s own worthless money.

The persecution of Christians

The end of Diocletian’s career saw renewed systematic persecution of Christians, which brought his reign to a tragic and bloody close. Why Diocletian broke the religious truce begun forty years earlier under Gallienus has been the subject of much speculation. Some scholars have seen his persecution based on religious principle: Diocletian, the self-proclaimed representative of Jupiter, sought to restore the old Roman faith and moral code. The circumstances under which the persecution began give some support to this view. They also show that Diocletian was politically concerned about ensuring conformity and uniformity among the population in order to strengthen the state in pursuit of security. Enemies of Christianity, like the Caesar Galerius and Hierocles, author of the Lover of Truth, were quick to brand the Christians as subversives and evil influences on the Empire.

The incident that sparked the persecution occurred in 299 at a public sacrifice. When the diviners inspected the entrails of the slaughtered animals in order to determine the will of the gods, they reported that the presence of hostile influences had frustrated and defeated the purpose of the sacrifice. Diocletian angrily gave orders that all persons in the imperial palace offer sacrifice to the traditional gods of the state or, upon refusal to do so, be beaten. The edict even applied to his wife, Prisca, who is alleged to have been a Christian or Christian sympathizer. Next, he permitted Galerius to post orders that all officers and men in the army be required to offer sacrifice on pain of dismissal from service.

In 303, Diocletian drafted an edict that ordered the destruction of Christian churches and the surrender and burning of Christians’ sacred books. It also prohibited Christian worship and restricted the rights of prosecution and defense formerly enjoyed by Christians in courts of law. One evening in the winter of 303, without having waited for the official proclamation of the aforementioned edict, the imperial police suddenly entered, ransacked, and demolished the Christian cathedral that stood opposite the emperor’s palace in Nicomedia. The edict was posted throughout the city the next day. An enraged Christian who tore down one of the posters was arrested and burned at the stake.

Within the next fifteen days, two fires of unknown origin broke out in the imperial palace in Nicomedia. Numerous Christian suspects were imprisoned, tortured, and killed. At the same time, revolts ascribed to Christians in Syria and Cappadocia, though easily suppressed, led to the proclamation of two more edicts. One ordered the imprisonment of Christian clergy. The other sought to relieve the overcrowding of the prisons: it offered liberty to all who would consent to make a sacrifice to the gods of the state and condemned to death those who refused.

After his visit to Rome, where he had just celebrated the twentieth anniversary of his accession, Diocletian became very ill and ceased to attend to public affairs. According to Eusebius, Galerius seized the opportunity to draft and publish a fourth edict, which required all Christians to offer the customary sacrifices under pain of death or hard labor in the mines. None of the four edicts, except perhaps the first, was enforced everywhere with equal severity. In Gaul and Britain, Constantius limited himself to merely pulling down a few churches, whereas Galerius and Maximian were far more zealous in their domains. When Diocletian abdicated in 305, the persecution was at its height and would not end until 311.

The abdication

On May 1, 305, in the presence of the assembled troops at Nicomedia, Diocletian formally abdicated. With tears in his eyes, he took leave of his soldiers. He told them that he was too old and sick, probably from a stroke, to carry on the heavy tasks of government. On the same day at Milan, in fulfillment of a promise previously extracted by Diocletian, Maximian also resigned. Diocletian nominated Constantius Chlorus and Galerius as the new Augusti, with seniority for Constantius, who received as his special provinces Gaul, Britain, Spain, and Mauretania. Galerius took the Balkans and most of Asia Minor. Galerius, in turn, nominated his nephew Maximinus Daia as his Caesar in the East and ruler over the provinces in the rest of Asia Minor, Syria, and Egypt. Constantius accepted Galerius’ friend Flavius Valerius Severus as his Caesar in the Herculian dynasty. Severus was to rule over Italy, Roman Africa, and Pannonia.

After their abdication, the two ex-Augusti went into retirement. Maximian, fuming over his enforced abdication, went to Lucania (or Campania) to await the first opportunity to snatch back his share of the Empire. Diocletian retired to an enormous fortress palace on the Dalmatian Coast outside of Solin (Salona, Salonae) at Split (Spalatum, Spalato). He spent the last eight years of his life there in the manner of a good Roman gentleman. He tended his estate and intervened directly in events only once (p. 582). Whatever influence he may have kept at the seat of power disappeared in 311 with the death of his son-in-law, Galerius. Indeed, even Galerius shortly before he died issued an edict that called for an end to Diocletian’s policy of persecuting Christians and proclaimed official toleration of their religion (p. 583). Diocletian himself died from either illness or suicide probably in December of 312.

Prisca and Valeria

Diocletian’s wife, Prisca, and his daughter, Valeria, were still deeply involved in imperial politics. After Diocletian had retired to Split, Prisca went to live with Valeria and her husband, Galerius, in Thessalonica (Salonica, Thessaloniki, Saloniki). Valeria had received many high honors in her role as Diocletian’s daughter and Galerius’ wife. Just as Julia Domna before her, she had been named Mother of the Armies. After the defeat of Narses, she was the first woman ever to be granted a laurel crown of victory by the senate. The Pannonian province of Valeria was even named after her.

When Galerius died, the western Caesar, Licinius, succeeded him (p. 583). The eastern Caesar, Galerius’ nephew Maximinus Daia, unwillingly had to stay put. Licinius was left in charge of the politically important Prisca and Valeria. They did not feel safe with him. He probably feared that they would attract the attention of potential challengers for his throne. Prisca and Valeria fled to the disgruntled Daia. His daughter was betrothed to Galerius’ adopted illegitimate son Candidianus, whom the childless Valeria had helped raise. Daia gave them refuge precisely because he wanted to challenge Licinius. When, however, Valeria refused to marry him, he banished them to house arrest in Syria.

They escaped when Daia perished after Licinius defeated him in 313. At that point, the two women seem to have joined Candidianus, whom Licinius initially treated well at his court in Nicomedia after Daia’s death. Then, Licinius began to fear Candidianus as a rival and had him executed along with another possible pretender. Prisca and Valeria fled to Thessalonica, where they were hunted down and beheaded in 315.

Problems left by Diocletian

Ultimately, many of Diocletian’s reforms and policies did not work. He had created a huge administrative and military machine that surpassed the ability of the economy to support it and impeded communication between the center and the periphery. It encouraged corruption and reduced citizens of all ranks to subjects. Their response to an oppressive system was frequent disobedience. A new system of coinage and attempts to control prices only led to more inflation, shortages, and black markets. Diocletian’s persecution unnecessarily alienated the Christian community. Moreover, the Tetrarchy was held together only by the dynamism of Diocletian himself. Once he was removed, his successors began struggling amongst themselves for personal dominance. Another series of civil wars erupted and threatened to destroy the empire that he had rescued from total collapse.

NOTES

1 The constitutiones principum (statutes of the emperors), which had the validity of laws, included (1) edicta, or edicts (official proclamations of the emperor as a Roman magistrate, which were valid during his term of office for the whole Empire); (2) decreta, or decrees (court decisions of the emperor having the force of law); (3) rescripta, or rescripts (written responses to written inquiries on specific points of law). Although the constitutiones were originally valid only during the principate of their author, they later remained in force as sources of public and private law unless revoked by a later imperial constitution.

2 Manichaeism may have provided some link between their revolt and Narses’ hostile actions. At least Diocletian may have thought so by the time he outlawed Manichaeism in 302.

Suggested reading

Leadbetter , B. Galerius and the Will of Diocletian. London and New York: Routledge, 2009.

Rees , R. Diocletian and the Tetrarchy. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2004.