Chapter 31

Diocletian had lived to see the disintegration of the Tetrarchy and the recognition of a religion that he himself had persecuted. He saw his own great fame fade into obscurity before the blazing light of Constantine’s rising sun and died in the belief that he had worked in vain. In principle, however, after gaining control of the Empire, Constantine continued many of the social, economic, military, and administrative policies established by Diocletian.

Constantine the Great, as he came to be called by Christian writers, was the son of Constantius Chlorus, Maximian’s Caesar and eventual successor as Augustus in the West. His mother was named Helena, but her origin and the details of Constantine’s early years are hard to discern. The existing information is scanty and distorted by the biases of his Christian boosters and pagan detractors. For example, the former call Helena a virtuous Christian wife and mother, but the latter call her only a concubine of low birth and questionable morals.

Although certainty is impossible, the best evidence indicates that Constantine was born in 272 or 273, probably in or near Naissus (Nĭs or Nish) in what was then the Balkan province of Moesia, later Dardania, and now Serbia. By 289, his father had set aside his mother in favor of a politically advantageous marriage to Theodora, the (step)daughter of Maximian, who was then Diocletian’s Caesar in the West. Subsequently, Constantine was sent to Diocletian’s court in the East, where he received excellent training in the arts of politics and war.

Constantius may have had little choice in these matters: his own military success marked him as a potential rival for power. Demonstrating his loyalty by accepting Maximian’s (step)daughter in marriage and sending his son to live under the watchful eye of Diocletian may have been a way to guarantee the safety of himself and his family. Constantine never seems to have held his father’s actions against him, and he rejoined his father soon after Diocletian and Maximian abdicated.

The rise of Constantine, 306 to 312 c.e.

By 306, Constantine had already distinguished himself militarily during Galerius’ victorious Persian campaigns of 298 and was becoming a popular figure with the troops. Although Constantius was nominally the senior Augustus after 305, Galerius was the actual master of the Empire. He still basked in the glories of his Persian victories. The two Caesars, his nephew Maximinus Daia in the East and his old friend Flavius Valerius Severus in the West, were both devoted to him. The presence of the young Constantine at what was now Galerius’ court also gave Galerius a popular advocate with the army and leverage with Constantius.

Galerius’ leading role in the last persecution of the Christians engendered a strong bias against him in the later sources, which are largely Christian and favor the Christian hero Constantine. Here, for example, is a summary of Lactantius’ story about how Constantine rejoined his father (On the Deaths of the Persecutors, 24.5ff.):

When Constantius asked Galerius to let Constantine help him battle the Picts, who had invaded Britain from Scotland in 306, Galerius was unwilling to let him go. One day, however, when Galerius was in a good mood after dinner, he gave Constantine a pass to use the imperial posting system (cursus publicus) to go wherever he wanted. Taking no chances, Constantine left in the middle of the night to rejoin his father. As he had feared, Galerius changed his mind the next morning and sent pursuers. Constantine foiled his enemies by killing or laming the remaining post horses after each change of mounts.

The truth is probably more prosaic. In fact, it can be shown that instead of reaching Constantius on his deathbed in Eburacum (York), as the story goes on to claim, Constantine joined him at the port of Gesoriacum (Bononia, Boulogne) on the English Channel. From there, they set sail for Britain and successfully defeated the Picts before Constantius died at Eburacum on July 25, 306. Contrary to the principles of the Tetrarchy, the army immediately proclaimed Constantine as the new Augustus at the head of the Herculian side of the Tetrarchy.

That title, however, now rightly belonged to Constantius’ Caesar, Severus. Constantine seems to have tried to protect himself and his position by being both accommodating and opportunistic. For the moment, he accepted the title of Caesar from Galerius and did not contest Severus’ elevation to the position of Augustus in the Herculian dynasty. Galerius rewarded him by sharing the consulship with him in 307. During that year, however, Constantine had an opportunity to obtain recognition as an Augustus from another source.

The usurpation of Maxentius, 306 c.e.

Maximian’s son Maxentius had been incensed at receiving nothing when Severus and Constantine were made Augustus and Caesar in the West. Questioning the status of Constantine’s mother, he argued that he, as the legitimate son of an ex-Augustus, had a better right to the throne. At Rome, the Praetorian Guard and population in general backed him because they resented the loss of privileges that Diocletian, Galerius, and Severus had gradually removed as they sought to increase the revenues of the state. Therefore, Maxentius declared himself Augustus. Maximian repudiated his retirement, reclaimed the title of Augustus, and backed Maxentius.

Complex maneuvers

Severus failed to dislodge Maxentius from Rome in the spring of 307 and soon after withdrew to Ravenna. Ultimately, he surrendered to Maximian and abdicated, but that did not save his life. In the fall of 307, Maximian visited Constantine in Gaul. Constantine had prudently concentrated on building up the defenses and loyalties of his own provinces. He had avoided direct involvement in the conflicts of the others. Now, he threw in his lot with Maximian and Maxentius against Galerius in return for their recognizing him as an Augustus. He divorced his first wife and married Maximian’s daughter Fausta. Constantius had originally betrothed Constantine to her fourteen years earlier, but no marriage had yet resulted. Now, it would have been dangerous to leave Fausta free for Maximian and Maxentius to use in attracting some other ally. Also, as the daughter of the former Augustus of the Herculian dynasty, she strengthened Constantine’s dynastic position even further.

In April of 308, Maximian turned against Maxentius but failed to drive him from Rome. Maximian fled to Constantine, who gave him refuge. Galerius tried to stabilize the situation in November of that year by summoning a meeting with Diocletian at Carnuntum on the Danube in Upper Pannonia (map, p. 378). Diocletian refused to resume power. Maximian was forced to retire again, and Maxentius was condemned as a usurper. Galerius obtained approval of his old comrade Licinius to replace Severus as Augustus in the West.

Constantine and Maximinus Daia (Galerius’s Caesar) did not attend and refused to accept subordinate positions as “sons of the Augusti.” In late 309 or early 310, Galerius yielded and accepted them as full-fledged Augusti. Later, in 310, Maximian tried to raise a revolt against Constantine in Gaul. He apparently committed suicide after Constantine captured him.

Abandoning the Tetrarchy

By 310, it probably was apparent to Constantine that the tetrarchic system of Diocletian would never work and that he had the opportunity to consolidate the whole Empire under his own leadership. Galerius was dying of cancer, Maximinus Daia and Licinius hated each other, and Maxentius’ position in Rome and Italy was rapidly deteriorating. At that point, Constantine repudiated the Herculian dynasty as the basis of his claim to rule and sought a new sanction by announcing his descent from the renowned Claudius Gothicus. In place of Hercules, he adopted as his patron deity the Unconquered Sun (Sol Invictus), who was identified in Gaul, it seems, with Apollo. Sol had also been the protector of Claudius Gothicus and Aurelian. Constantine’s claim of descent from Claudius Gothicus would enable him to assert not only his right to the throne by inheritance but also his right to undivided rule over the whole Empire. Fortified by this new sanction, Constantine declared Maxentius a usurper and a tyrant, but he postponed further action to await more favorable circumstances after the death of Galerius.

The Edict of Religious Toleration, 311 c.e.

After the abdication of Diocletian, the persecution of the Christians had continued in Galerius’ dioceses (Illyricum, Thrace, and Asia Minor) and particularly in those of Maximinus Daia (Syria and Egypt). Finally, near death in 311, Galerius became convinced of the futility of the Christian persecutions. As senior Augustus, he issued his famous Edict of Toleration that granted Christians all over the Empire freedom of worship and the right to reopen their churches, if only they would pray for him and the state and do nothing to disturb public order. He explained his change of policy by stating that it was better for the Empire if people practiced some religion than none at all. A few days after the proclamation of this edict, Galerius died.

Predictably, after the death of Galerius, Maximinus Daia at once overran and seized the Asiatic provinces of Galerius and threatened Licinius’ control over the Balkans. In anticipation of war with Maxentius, Constantine had made an alliance with Licinius and betrothed to him his half-sister Constantia, who was then in her late teens. Meanwhile, Daia had made a secret agreement to cooperate with Maxentius.

Constantine’s invasion of Italy, 312 c.e.

Constantine launched his long-awaited invasion of Italy in the spring of 312. He set out from Gaul with an army of nearly 40,000 men and crossed the Alps. Near Turin, he met and defeated a large force of armored cavalry dispatched by Maxentius. Quickly seizing northern Italy, he advanced against Rome. Maxentius had originally intended to defend the city behind the almost impregnable walls of Aurelian because Constantine’s army probably was not equipped either to take the city by storm or to conduct a long siege. Nevertheless, either belief in signs sent by the gods or fear of a popular uprising caused Maxentius to change his plan. Instead, he went out to meet Constantine in open battle.

The Battle of the Milvian Bridge, 312 c.e.

Maxentius had ordered the Milvian Bridge to be destroyed as a defensive measure in accordance with his earlier strategy. Now, he led out his army over the Tiber on a hastily constructed pontoon bridge. It comprised two sections held together with chains, which could be quickly cut apart to prevent pursuit by the enemy. Maxentius advanced along the Flaminian Way as far as Saxa Rubra, “Red Rocks” (about ten miles north of Rome), where Constantine had encamped the night before.

Lactantius says that on the night before the battle a vision appeared to Constantine and bade him place upon the shields of his soldiers the Christogram (☧), a monogram consisting of an X with a vertical line drawn down through it and looped at the top to represent chi and rho, the first two letters of Christ’s name in Greek, XPIΣTOΣ. With less plausibility, Eusebius asserts that Constantine told him years later that sometime before the battle, he saw a miraculous sign across the face of the sun: a flaming cross and beneath it the Greek words ἐν τοὺτῳ νίκα or, as handed down in the more familiar Latin form, in hoc signo vinces (in this sign you shall conquer). Whatever vision Constantine may have had (if he had one at all), when he went forth into battle, he soon drove the enemy back to the Milvian Bridge and won a total victory.

The next day, Constantine entered Rome in triumph. In the forefront of the procession, a soldier carried the head of Maxentius on a spear. The jubilant throng hailed Constantine as liberator. The senate damned the memory of Maxentius, declared his acts null and void, and proclaimed Constantine senior Augustus of the entire Empire.

A victory for Christianity

Although the senate undoubtedly hailed the elevation of Constantine as the triumph of libertas, the true victor would turn out to be the Christian Church. Constantine’s arch of triumph includes a representation of the Unconquered Sun and bears an inscription that claims that he achieved victory by the intervention of an unnamed divine power (instinctu divinitatis) and by his own greatness of mind (mentis magnitudine). Nevertheless, a victory statue of Constantine held a cross in its right hand. That publicly recognized the valuable support of the Christians, which he had cultivated by his tolerant policies in the provinces under his control.

Although Constantine eventually came to ascribe his victory wholly to the intervention of Christ, he did not become an exclusive believer in Christianity upon his victory at the Milvian Bridge. On the other hand, he clearly was a believer before his baptism at the end of his life. Exactly when his full conversion took place cannot be said. The interactions of political considerations and personal developments made it a complex, gradual process. He was obviously too keen a statesman to attempt to impugn or suppress immediately the religious beliefs of 80 to 90 percent of his subjects, not to mention the senate, imperial bureaucracy, and army. Also, one victory, however brilliant and decisive, could not in one day completely change his old beliefs.

As emperor, Constantine continued to hold the ancient Roman office of pontifex maximus. A set of gold medallions struck in 315 represents a blending of typical Roman and Christian symbolism: it shows the emperor with the Christogram on his helmet, the Roman she-wolf on his shield, and a cruciform-headed scepter in his hand. Constantine continued to strike coins in honor of Mars, Jupiter, and even Hercules until 318; and coins in honor of the Sun until 323. Thus Constantine’s reign was a link between the pagan Empire that was passing and the Christian Empire that was to come.

As senior Augustus, Constantine ordered Maximinus Daia to discontinue his persecution of the Christians in the East. Daia only grudgingly obeyed. In 313, Constantine instructed his proconsul in Africa to restore to the churches all confiscated property; to furnish Caecilianus, the newly elected bishop of Carthage, funds for distribution among the orthodox bishops and clergy in Africa, Numidia, and Mauretania; and to exempt them from all municipal civic duties or liturgies (public services provided to the community at private expense). That done, Constantine left Rome for Milan (Mediolanum) to attend a conference with Licinius.

The conference of Milan, 313 c.e.

At the conference of 313 in Milan, the long-expected marriage of Licinius and Constantia took place. The two emperors also reached a general agreement regarding complete freedom of religion and the recognition of the Christian Church or, rather, granting each separate local church legal status as a “person.”1

The publication of a so-called Edict of Milan is open to some doubt, although the agreements reached included not only Galerius’ documented Edict of Toleration from 311 but also all of Constantine’s rescripts concerning the restitution of the churches’ property and their exemption from public burdens. Licinius enforced these agreements not just in his own domains in Europe but even in the East, which he soon liberated from Maximinus Daia.

The end of Maximinus Daia, 313 c.e.

Maximinus Daia was undoubtedly a man of some principle, military competence, and statesmanship, but he is understandably vilified by Christian writers. Despite the publication of Galerius’ Edict of Toleration, Daia had still sporadically persecuted the Christians in his dominions or subjected them to humiliating indignities. Constantine’s order in 313 to desist was obeyed, but with neither alacrity nor enthusiasm.

After the defeat and death of his ally Maxentius, Daia stood alone against the combined forces of Constantine and Licinius. Constantine’s departure for Gaul to repel a Frankish invasion of the Rhineland presented Daia with an excellent opportunity to attack Licinius. In the dead of winter, Daia crossed the Bosphorus (Bosporus) and captured Byzantium. Licinius rushed from Milan with a smaller but better-trained army. The two forces met near Adrianople (Adrianopolis). Defeated in battle, Daia disguised himself as a slave and escaped. Licinius pursued him into Asia Minor, where Daia fell ill and died. Licinius, with the East now in his hands, granted the Christians complete religious freedom. As he had agreed at the conference of Milan, he also restored to them their confiscated churches and properties.

Constantine and Licinius: the Empire divided, 313 to 324 c.e.

Once again the Empire was divided between two rival and distrustful brothers-in-law, as it had been in the days of Marcus Antonius and Octavian. In 315, Constantine tried to reinforce his position. He gave his half-sister Anastasia in marriage to a senator named Bassianus, the brother of a high-ranking officer under Licinius. When Constantine asked Licinius to agree in making Bassianus a Caesar in charge of Italy, Licinius used Bassianus’ brother to suborn Bassianus’ help in assassinating Constantine. When Constantine discovered the plot, he had Bassianus executed. War with Licinius soon followed in 316.

Licinius was defeated with heavy losses in Pannonia but fought to a draw in Thrace. Because neither wished the inconclusive struggle to continue, they arranged a truce: Licinius agreed to abandon his claim to any territory in Europe but Thrace; Constantine agreed to waive his claim as senior Augustus to the right of legislating for Licinius’ part of the Empire.

The peaceful compromise was neither destined nor intended to last. After a few years of apparent harmony and cooperation, relations between the two emperors slowly deteriorated. Constantine did not really want peace. Licinius’ eventual reversal of the policies agreed upon in Milan presented Constantine a ready-made, though specious, pretext for the war that gave him the whole Empire.

Unlike Licinius, Constantine had drawn closer to Christianity ever since the Battle of the Milvian Bridge. The benefits that Constantine bestowed upon the Church at that time were in thanks to the Christians’ deity for the heavenly aid that he believed he had been given in battle. In turn, he recognized the Christian Church on earth and made it an effective partner of the state.

Constantine certainly had to take into account the predominance of pagans in the population, army, and bureaucracy. Still, he authorized measures that went far beyond the agreements reached in Milan and granted Christians ever more privileges and immunities. An important feature of his religious policy was to permit the pope (bishop of Rome) and the orthodox clergy to determine correct doctrine and discipline within the Church. In a constitution published in 318, Constantine recognized the legality of decisions handed down by bishops’ courts. He also allowed the bishops to enforce their decisions by the authority of the state. In a rescript of 321, he not only legalized bequests by Roman citizens to the Christian Church but assigned to it the property of martyrs dying intestate. In the same year, he proclaimed Sunday a public holiday and day of rest for people working in law courts and state-run manufacturing operations.2 Symbolic, too, of Constantine’s growing personal acceptance of Christianity was that after the Battle of the Milvian Bridge, he adopted the labarum, a standard consisting of a long-handled cross with a chi-rho monogram at the top.

The Donatist Schism

Constantine’s personal experiences and Christian mentors such as Bishop Hosius of Corduba had convinced him of the power of the Christians’ deity. He also saw the benefits that the state could derive from being united with the strong, effective organization that the Christian Church identifying itself as universal (Catholic) had become. Therefore, Constantine took a serious view of a schism that was rending the Church in Africa and destroying unity in the state. The schism derived its name from Donatus, the fanatical leader of a radical group of dissident clergymen. This group had protested strongly against the election of Caecilianus as metropolitan bishop of Carthage. They claimed that he was too ready to grant pardon and restore to clerical office those who had betrayed the faith during Diocletian’s persecution and had surrendered the Holy Scriptures for burning. The Donatists championed Donatus himself, who had endured six years of prison and torture without breaking. Contrary to the will of the pope in Rome, they held their own election and installed Donatus as bishop of Carthage.

The African dispute rose to a crescendo of fanaticism when Constantine denied the Donatists a share in the benefactions that he had recently granted the African clergy and congregations loyal to the pope. Two church councils summoned by Constantine in 313 and 314 ruled against the Donatists. They appealed to the emperor to judge their case himself. At last, he agreed. After much deliberation, he reaffirmed the decisions of the councils and ordered the military suppression of the Donatists and the confiscation of their churches. In 321, realizing that persecution only heightened their fanaticism and increased the turmoil in Africa, Constantine ordered the persecutions to cease. He scornfully left the Donatists “to the judgment of God.” His first attempt to restore peace and unity in the Church had failed dismally.

The Arian heresy

Similar religious problems confronted Licinius, but he handled them differently, yet no more successfully. At first, he faithfully observed the decisions reached in Milan, but, when a Christian controversy arose in Egypt and threatened to disrupt the peace and unity of his realm, he resorted again to systematic persecutions of the Christians. The dispute centered on Arius, a priest associated with a group in Egypt that also opposed leniency toward Christians who had betrayed their faith during Diocletian’s persecution. He held views about the nature of Christ that his opponents could use to discredit him as a heretic. He argued that Christ was not “of the same substance” (homoousios) as God the Father but “of different substance” (heteroousios): since Christ was the Son of the Father, he must, therefore, have been subsequent and posterior; although he was begotten before all worlds, there must have been a time when he was not.

Arius’ view was not substantially different from the occasional utterances of some great Church Fathers of the early third century (e.g., Origen, St. Dionysius of Alexandria, and Tertullian in his old age). Bishop Alexander of Alexandria, however, argued that the Son was of the same substance with the Father, and that all three persons of the Trinity (God the Father, God the Son [Jesus Christ], and God the Holy Spirit) were one in time, substance, and power, representing the three aspects of the Almighty Power of the universe.

Alexander, whose position eventually prevailed as the orthodox view, excommunicated Arius and touched off a raging controversy that even drew in Licinius’ wife, Constantine’s half-sister Constantia. Never really sympathetic toward Christians, Licinius now saw in their controversies a disruptive element all the more dangerous because of his impending power struggle with Constantine (on whose behalf he perhaps suspected they were saying their prayers). Accordingly, in 320, he renewed the persecution of the Christians.

The defeat and death of Licinius, 324 c.e.

Although renewed Christian persecutions provided Constantine with a moral issue in his ultimate war against Licinius, he found a more immediate cause in the Gothic invasion of Moesia and Thrace in 323. To repel the invasion, Constantine had no other recourse but to trespass upon the Thracian domains of Licinius. Licinius made an angry protest; Constantine rejected it. Both sides at once mobilized.

In the middle of 324, Constantine attacked and defeated Licinius’ forces. Licinius surrendered. An appeal by Constantia elicited an oath from Constantine to spare his life. Licinius was exiled to Thessalonica (variously known as Salonica, Thessaloniki, Saloniki). Six months later, however, Constantine broke his word and had him put to death on a charge of treason. Constantine was now sole emperor, something that Roman Empire had not seen in almost forty years. The new slogan of the Empire came to be “one rule, one world, and one creed.”

Constantia and her sisters

Constantine was still insecure enough about a year later to execute the young son that Constantia had borne Licinius. Somehow, Constantine’s relationship with her survived despite the bloodshed. Neither Constantia nor Anastasia seems to have remarried after the executions of their husbands. Their sister, Eutropia, was luckier. She was married to the respected senator Virius Nepotianus. She was the only one of Constantine’s half-siblings to survive the purges after his death (pp. 596–7). Her son, however, also named Nepotianus, did not survive even a month as emperor in 350 before he was killed by the usurper Magnentius (pp. 596–7).

Both Anastasia and Constantia were honored members of Constantine’s court. Constantia took an active interest in theological debates and religious politics. She corresponded with Bishop Eusebius of Caesarea, the Church historian and admiring biographer of Constantine. She even attended the Council of Nicaea called to deal with the controversy concerning Arius and helped his defenders. Constantine greatly mourned her death about five years later.

The Council of Nicaea, 325 c.e.

Military victory had suddenly reunited the Empire politically, but did not so quickly and decisively restore the religious unity that Constantine had striven to bring about. In all his efforts to promote religious unity, Constantine labored under one distinct handicap: he failed to see the religious importance of the controversy between Arius and the bishop of Alexandria. Because his chief aim was to achieve unity within the state, it made little difference to Constantine whether the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit represented a single, indivisible godhead or were three separate deities. He was a doer, not an intellectual. Accordingly, writing to Arius and Bishop Alexander, he urged them to get down to fundamentals: they should abandon their battle of words over what he considered abstruse and unimportant points of theology. His letter naturally failed to end the controversy.

Still hoping for an amicable solution to the problem, Constantine summoned an ecumenical council at Nicaea in Bithynia, to which bishops from all over the Empire might travel at state expense and at which he himself would also be present. The council opened on May 20, 325, with some 300 bishops, virtually all eastern, present. In his brief opening address, Constantine avowed his own devotion to God and exhorted the assembled bishops to work together to restore the unity of the Church. All else, he declared, was secondary and relatively unimportant. Reserving for himself only the right to intervene from time to time to expedite debate and deliberation, he then turned the council over to them.

The Council of Nicaea defined the doctrine and completed the organization of the Catholic Church. Its decisions not only were relevant to the problems of 325 but also affected Christianity for all time. It formulated the Nicene Creed, which, except for some minor modifications adopted at the Council of Constantinople in 381, has remained the creed of most Christian churches to this day. It declared Christ homoousios (of the same substance with the Father), proclaimed the Trinity indivisible, excommunicated Arius, and ordered the burning of his books. Easter was fixed to fall on the first Sunday after the first full moon following the spring equinox. Twenty canons (rules) also were formulated for the regulation of Church discipline and government throughout Christendom.

The negative consequences of the Council of Nicaea were momentous. First of all, it made compromise on the issue of Christ’s nature more difficult and split the Church into two hostile camps for years. It also bedeviled imperial politics, since some emperors were Arian and others upheld the Nicene Creed. While enjoying official favor under Constantius II (337–361) and Valens (364–378), Arians were able to spread their version of Christianity across the Danube to many of the Germanic tribes who eventually took over much of the western half of the Empire. It had remained staunchly orthodox in upholding the Nicene Creed. Consequently, sectarian hostility between the orthodox population of old Roman territories and the new German overlords hindered unity in the face of worse invasions later.

Ironically, the problem would have been less severe if the Germans had remained pagans. They could have been forgiven their ignorance and more easily converted. The Arian Germans already considered themselves true Christians and resented their rejection by those Christians who called themselves orthodox.

The Council of Nicaea also deeply influenced future relations between Christianity and the state during the remainder of Roman and subsequent Byzantine history. The formal role that Constantine played by convening the council reinforced the already close association that had developed between the head of state and the emerging Catholic Church during the Donatist Schism. Constantine’s actions at the Council of Nicaea provided the model for the Caesaropapism of later centuries, when the emperors dominated the Church and manipulated it for purposes of state. Constantine himself claimed to be Isapostolos (Equal of the Apostles) and the elected servant of God. He later tried to enforce universal orthodoxy by banning such Christian sects as the Novatians, Valentinians, and Marcionites, whom he called heretics.

Constantine’s secular policies

In adopting Christianity and abandoning the Tetrarchy, Constantine had radically broken with Diocletian. Still, he mainly followed Diocletian’s lead in other spheres, making changes that were more incremental than radical.

Monetary and fiscal changes

Constantine’s officials created a stable gold solidus minted at seventy-two to the Roman pound by making about a 16 percent reduction in the weight of Diocletian’s solidus (aureus: minted at sixty to the pound). They replaced the argenteus with a new silver coin, the miliarense (denoting a thousandth part of the gold pound). Silver remained in short supply, however, and the overproduction of base-metal coins continued to fuel inflation in terms of the ratio of base-metal coins to gold (p. 506). Fiscally, Constantine supplemented Diocletian’s taxes in kind with taxes in cash like Rome’s first tax on business, the collatio lustralis or chrysargyron (p. 617).

Military developments

The idea that Constantine abandoned a strong perimeter defense and substituted a policy of defense in depth (let the invaders in and pick them off after they have spread out) for one of preclusive security (keep invaders out) has been largely discredited. This understanding of his policy was based on two mistaken assumptions: first, that the Romans shared the modern idea of borders as fixed lines that clearly demarcated Roman territory from non-Roman; second, that Constantine withdrew the best troops from the frontier rearward to fortified positions and service in a mobile field army. Supposedly, he left only a weak peasant militia to sound the alarm when invaders appeared. As it has been mentioned already, Romans did not think in terms of fixed borders. The walls, roads, and rivers that are often viewed as boundaries were really part of a system of broad frontier zones. Within the frontier zones, they served to display Roman power, observe and control the movement of people, ensure military communication, and provide for the transportation of troops and supplies.

Both Diocletian and Constantine essentially kept the traditional Roman system of frontier defense. They did, however, disperse small detachments of soldiers in the cities and towns of frontier provinces to break up large concentrations of troops or oversee and protect the collection and storage of supplies as taxes in kind. Therefore, the troops responsible for guarding the frontier became more interspersed among the civilian population of frontier provinces. Over a long period of time, the distinction between soldier and civilian in the frontier zones became blurred. That blurring became common in the late fourth century and throughout the fifth as emperors settled invaders on vacant land in return for military service.

Constantine’s major military innovations were to increase the size of the mobile forces attached to the imperial court (comitatus), to accelerate the enrollment of Germans in imperial armies, and to appoint them to the highest governmental offices. To the regular troops of the comitatus (the comitatenses) Constantine added a new elite corps composed of some infantry, but mainly of cavalry and known as the protectores. He also replaced the old Praetorian Guard, which he disbanded in 312, with a personal bodyguard of crack troops. Most of them were Franks. To this bodyguard, he gave the distinctive name of Palace Schools (scholae palatinae).

Another important military development was the reorganization of the high command and the complete separation of military commands and civil functions. Constantine gave the operational military functions of the praetorian prefects to two supreme commanders known as master of the infantry (magister peditum) and master of the cavalry (magister equitum). Similarly, he abrogated the authority of the provincial governors over the dukes and counts, who commanded the frontier garrisons.

Administrative and political developments

Though stripped of their operational military functions, the praetorian prefects were still very powerful dignitaries. Each exercised the powers of a deputy emperor in one of Diocletian’s four great prefectures: Gaul, Italy, Illyricum, and the East. After 331, all judicial decisions handed down by them were final and were not subject to appeal even to the emperor. They supervised the administration of the imperial posting system (cursus publicus), the erection of public buildings, the collection and storage of taxes, the control of craft and merchant guilds, the regulation of market prices, and the conduct of higher education. Even more important, their executive control over the recruiting and enrollment of soldiers, the construction of military installations, and the provision of supplies acted as a powerful brake on ambitious army commanders.

High officials like the master of the infantry and the master of the cavalry were members of a vastly expanded imperial court (comitatus). Constantine kept Diocletian’s policy of surrounding the emperor with an elaborate court ceremonial to promote an aura of sacredness. He increased the number of personal attendants, many of whom, in Persian style, were eunuchs and became powerful by controlling personal access to the emperor. The most important were the chamberlain or keeper of the sacred bedchamber (praepositus sacri cubiculi) and the chief of the domestic staff (castrensis).

The highest administrators and important palace officials (palatini) made up the Sacred Consistory, the Imperial Council. The most powerful was the master of offices (magister officiorum). He controlled the newly formed Agents of Affairs (agentes in rebus), who carried dispatches, gathered intelligence, and controlled the movement of troops. He also oversaw the imperial bodyguards, arsenals, and arms production. He even controlled appointments with the emperor, received ambassadors, and thus influenced foreign policy.

Constantine and his successors still held the office of consul on occasion, retained the title pontifex maximus, and advertised their tribunica potestas in the tradition of Augustus. Nevertheless, the old magistracies continued to decline. Praetors had lost their judicial functions under Septimius Severus. Quaestors no longer had senatorial revenues to handle after the militarization of all provinces during the third century. By 300, the old praetors and quaestors had been reduced to one each. Their only duty was to conduct the games and entertainments during festivals in Rome. Constantine, however, created a new quaestor, the quaestor of the sacred palace. He was in charge of records, charters, and administrative directives as well as the drafting of laws.

Two consuls continued to be appointed, one at Rome and one at Constantine’s new eastern capital, Constantinople, but their office was merely honorary. The last real function of the consuls, as presidents of the senate, had already been transferred at some point to the urban prefect. His court heard the civil suits of all senators and the criminal suits of senators domiciled in Rome. The consuls’ other previous functions now belonged to a vicar of the praetorian prefect for Italy.

Under the presidency of the urban prefect, the Roman senate became only the municipal council of Rome. It no longer ratified the appointment of emperors, and its advisory function had been taken over by the Sacred Consistory. The emperor now merely informed the senate of his decisions, for which courtesy he received fulsome thanks.

In keeping with a long-standing trend, Constantine finally abolished the distinction between senators and equestrians. Because the need for competent officials was great, offices previously restricted to one class or the other were now open to both. Equites who were appointed to senatorial offices became senators. Therefore, the number of senators swelled to about 2500. Ironically, this change increased the prestige of the senators as a class, while the senate itself declined as an institution. Now senators became a part of the highest strata of imperial government, especially in the less urbanized West, where the great senatorial landowners were in a position to monopolize the highest posts. Constantine even revived the term patricius (patrician) as an official honor for senators who had performed particularly important services.

The founding of Constantinople, 324 to 330 c.e.

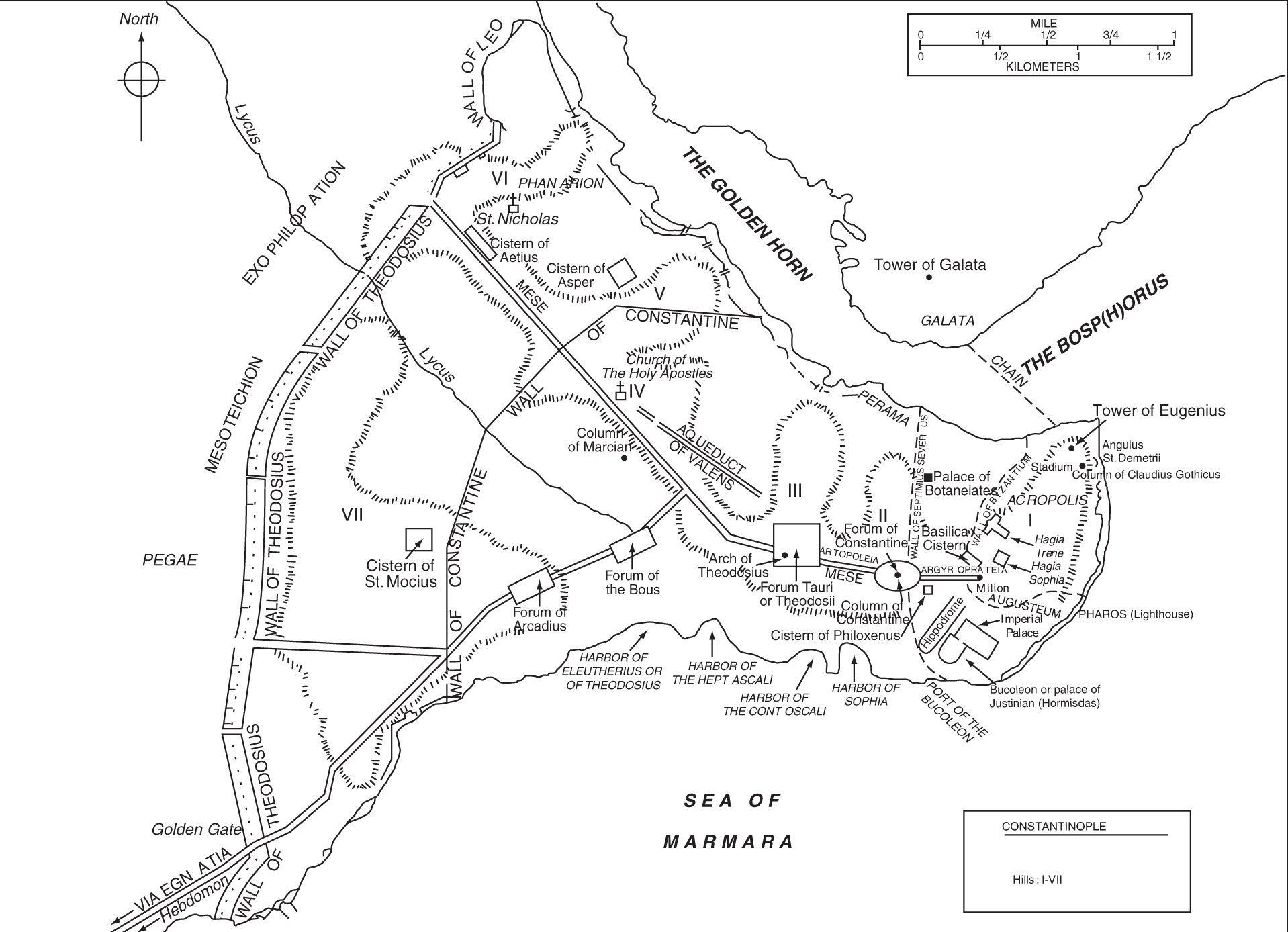

Since the time of Hadrian, the city of Rome and peninsular Italy had gradually lost their earlier dominance within the Empire. Citizenship, privileges, wealth, and political power had steadily spread outward to the provinces. Provincials came to make up the bulk of the soldiery, the bureaucracy, and the senatorial class and finally occupied the throne itself. Although the city of Rome still had much symbolic value for its possessor, it was no longer strategically well placed in relation to the constantly threatened frontiers. Milan eventually supplanted it as the strategic imperial residence in the West. Constantine realized, as had Diocletian, that the Empire had to be defended and administered from strategically located imperial residences in both the East and the West. Also, Rome’s loss of privileges and Constantine’s increasing favor toward the Christian Church alienated old pagan families that still dominated Rome. Therefore, the idea of a new Rome strategically located in the East and free from the deeply rooted pagan traditions of the old Rome greatly appealed to Constantine. His choice for his Eastern residence was the old, decaying Greek city of Byzantium. He began to transform it in 324 and gave the city its new name Constantinople (City of Constantine).

This choice was a stroke of genius. Constantinople, now the Turkish city of Istanbul, is located where the Black Sea flows through the straits known as the Bosphorus (Bosporus) into the Sea of Marmara (Marmora). Here Europe meets Asia. Through the city passed roads linking the Near East and Asia Minor with the Balkans and Western Europe. Those roads gave easy access to two of the main battlefronts of the Empire, the lower Danube and the Euphrates. Situated on a promontory protected on two sides by the sea and by strong land fortifications on the third, Constantinople occupied an almost impregnable position. It was not be taken by storm for more than 1000 years. It also enjoyed an excellent deep-water harbor (later called the Golden Horn). A great chain quickly and easily closed its entrance against attack by sea. Ideally located for trade, it captured the commerce of the world from the East and the West, the North and the South: furs from the North; silk from the Orient; spices from India and Arabia; fine wines and olive oil from Asia Minor and the Mediterranean; grain, precious stones, and exotic animals from Egypt and Africa.

In every way, save religion, Constantine made the new imperial city an exact equivalent of Rome. Rome was still the capital, but a capital no longer limited to one place. Rome was now almost an idea conveyed by replicating its essential features in Constantinople. The New Rome, as it was also called, had to share or duplicate old Rome’s essentials: part of the senate (mostly senators from the eastern provinces); one of the two annual consuls; a Populus Romanus, privileged and exempt from taxation; and, above all, a plebs who received free entertainment and food.

To beautify the new city, Constantine ransacked ancient temples and shrines—even Delphi, from which he removed the tripod and the statue of Apollo. His confiscations, which some accounts (probably exaggerated) place at 60,000 pounds of gold, made it possible for him to build in Constantinople an enormous imperial palace, a huge hippodrome, a university, public schools and libraries, and magnificent Christian churches—Holy Peace (Hagia Eirene), Holy Wisdom (Hagia Sophia), and Holy Apostles. After dedicating the new city on May 11, 330, Constantine resided there most of his remaining life.

The death of Constantine the Great, 337 c.e.

Domestic tragedy marred what Constantine could otherwise have considered a glorious reign. In 326, he had his eldest son, Crispus, a youth with a brilliant military future, put to death on a trumped-up charge of raping his stepmother, the Empress Fausta. It appears that she had engineered the story to remove him as a possible rival of her own three sons—Constantine II, Constantius II, and Constans. In the same year, the empress herself died, scalded in a hot bath, supposedly after the emperor’s mother, Helena had revealed that Fausta had committed adultery with a slave.

FIGURE 31.1 Constantinople (Hills: I–VH)

In 337, while preparing to lead an army against Persia in retaliation for unprovoked aggression against the Roman protectorate of Armenia, Constantine fell ill. A visit to the hot springs of Helenopolis failed to help. On the way back to Constantinople, near Nicomedia, he felt the relentless approach of death. He asked Bishop Eusebius of Nicomedia, who had vigorously defended Arius at Nicaea, to administer the sacrament of baptism. (It was not uncommon to put off baptism until late in life in order to die in a blameless state.) While still arrayed in the white robes of a Christian neophyte, Constantine died. His tomb was the mausoleum connected with the Church of the Holy Apostles.

Overview

It would be difficult to overstate the significance of Constantine’s reign. He had ruthlessly eliminated all political rivals and reunited the Roman Empire under one ruler. He had taken Christianity, a small, persecuted sect, and given it the impetus that made it one of the major religions of the world. Indeed, he greatly influenced the formulation of its most widely accepted creed and institutional structure. Finally, by following up and skillfully modifying Diocletian’s reforms and by his splendid choice of a new residence, Constantine laid the foundations of the Byzantine Empire, which was to last 1000 years and have an incalculable impact upon Europe and the Near East.

NOTES

1 In much the same sense, modern business and nonprofit corporations are legally “persons.” They can own property, make contracts, and sue or be sued in court.

2 The proclamation could have been interpreted by a Christian as instituting “the Lord’s Day” and by a pagan as celebrating “the holy day of the Sun.”

Suggested reading

Drake , H. A. Constantine and the Bishops. The Politics of Intolerance. Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press, 2000.

Van Dam , R. The Roman Revolution of Constantine. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007.