Chapter 37

The restored Roman Empire of the fourth century had disintegrated during the fifth and sixth. Since the time of Montesquieu and Edward Gibbon, many modern thinkers have attempted to explain Rome’s fall. It is an impossible task. The process of disintegration took place over a huge area for a long time. It was extremely complex in detail. The factors involved are so numerous, their interactions so involved, and the evidence so limited in comparison that a definitive analysis is impossible. At the general level, however, it is clear that given its geographic, economic, social, political, and cultural characteristics, the Roman Empire was unable to sustain the frequent and simultaneous blows of “barbarian” migrations and invasions in the West and war with the Sassanid Persians in the East. Without those or similar external factors, the Roman Empire as a political entity might have continued indefinitely, despite its weaknesses.

During the fifth and sixth centuries, many of the internal characteristics that identified the Empire in Late Antiquity as still Roman in the Classical sense underwent major transformations. As always, changes did not occur at a uniform pace or even in the same way everywhere within the Empire’s vast territories. By the early seventh century, however, the cumulative effects had created a world that was quite different from that of the fourth and was recognizably medieval despite significant continuities with the Classical Roman past.

The economy

In general, the economy of the late antique Roman world declined in the fifth and sixth centuries, sooner and more steeply in the West than in the East and more in some ways than in others. Despite overall economic decline, there were major shifts in wealth that enriched some even while others saw their wealth reduced or destroyed altogether. In the West, Germanic kings and their loyal warriors were enriched at the expense of Roman landowners. The latter often lost anywhere from one-third to all of their property to their new overlords. In the East, wealth poured into the new capital at Constantinople to the benefit of the eastern emperor and a growing class of imperial functionaries. Everywhere, Christian churches, monasteries, and shrines received countless donations of land, money, gold, silver, jewels, and other precious goods from those who piously sought divine favor or shrewdly hoped to acquire influence in an increasingly powerful institution.

Economic fragmentation and declining trade

Although reduced in volume, long-distance trade in luxury goods continued to follow traditional patterns between the eastern and western Mediterranean. Those who had retained their wealth or were newly rich were willing to pay for high-status goods at prices that attracted suppliers no matter what the risks and hardships. In the East, regional trade and production remained steady until the Arabic Muslim conquest in the early seventh century.

In general, however, the collapse of the Roman state in the West fragmented the economy of the Roman world and caused major changes in the production and distribution of goods. The Roman armies and the system of taxation and supply to maintain them had been powerful forces promoting the production and transportation of a wide range of goods in large quantities over considerable distances. Roman administrative centers and major military posts had stimulated the development of profitable urban markets. The state’s system of military roads and transport had subsidized commercial shipments. The government’s demands for taxes and supplies had spurred the higher levels of organization and production that had sustained a larger and more sophisticated private sector than would have been possible otherwise. By the end of the fifth century, this system had disappeared in the western provinces.

Decline of monetization and the monetary system

During the fifth century, the only stable coinage was based on gold. Silver disappeared into private hands as hoarded coins or the elaborate silver plates and utensils that adorned churches and wealthy homes. The increasingly debased bronze or copper coins were so worthless that they had to be sealed up by the hundreds or even thousands in a leather bag (follis) and exchanged by weight. In the West, the Germanic successor kings tried at first to maintain imperial-style fiscal and monetary systems. Gradually, they surrendered the control of taxation and the right to coin money to local magnates and towns. By the early seventh century, coins ceased to circulate widely.

In the East, at the end of the fifth century, Emperor Anastasius successfully reformed the coinage of the eastern provinces (p. 699). His good-looking, well-made new bronze coin, the follis (so named because it was worth a bagful of the old coins) and its fractions, held their value. Justinian continued to improve them until the wars of the 540s. Then, war debts and the need for bronze to make arms forced him to debase the bronze coins once more.

As a result, inflation wracked the economy of the eastern Empire. Tiberius II (578–582) and Maurice (582–602) stabilized the coinage temporarily, but the assassination of Maurice and subsequent chaos, the wars with Persia, and attacks by the Arabs threw the monetary system of the East into turmoil. Inflation raged, most imperial mints ceased to function, and uniform, regular denominations of coins for daily use could not be maintained.

Agricultural trends

As trade and the Roman monetary system that supported it declined in the fifth and sixth centuries, the amount of cultivated lands in Roman territory declined, too. Contrary to older views, soil exhaustion was probably not a general problem. Often good or potentially good land was simply abandoned because of population loss or lack of security. In some fortunate or protected areas, particularly in the East, agriculture flourished and even expanded well into the sixth century. Justinian’s wars in the West caused enormous destruction. Even in the East, their huge expenses were overburdening the small proprietors, and the concentration of land in the hands of a wealthy few became more pronounced than it had been in that part of the Empire.

Social and demographic changes

The economic trends of the fifth and sixth centuries accompanied major social and demographic changes. Although the population of the Empire had always been overwhelmingly rural, it became more so. At the same time, the total population declined. By the end of the sixth century, the late antique social world had given way to one that would characterize the medieval world for centuries.

The end of the Classical city

Although the urban population of the Roman Empire as a whole was probably never much more than 10 percent, the Classical Greco-Roman city gave Roman civilization its unique character. The Classical city had a number of easily recognizable features: citizen rights and civic institutions; an identifiable architectural style; standard public buildings and monuments like shrines, temples, baths, theaters, amphitheaters, circuses, markets, libraries, fora, honorific statues, commemorative arches, and inscriptions of all kinds; public works such as aqueducts, fountains, latrines, sewers, and well-paved streets. Maintaining and spreading the distinctive form of the Classical city had provided the social, cultural, and administrative glue that had held together Rome’s far-flung empire. During the fifth and sixth centuries, the cities of the Roman Empire were abandoned, destroyed, or transformed into something quite different in every way from what they had been before. Those that remained inhabited shrank to shadows of their former selves; their economic function became much more limited, primarily as local or regional market towns; the Classical style and construction of buildings gave way to local vernaculars; ecclesiastical institutions replaced civic; and the amenities disappeared.

The decline of Roman cities was both a function of and a contributor to the other changes taking place in the late antique Roman world. Attacks by invaders and usurpers weakened them so that they were more vulnerable to attack. The decline of trade and agriculture undermined them economically so that there was even less of a market for trade goods and agricultural products. The inability or unwillingness of urban elites to perform increasingly burdensome civic duties weakened civic institutions still further.

Like lights successively going out on a cascading power grid, Roman cities declined in a progression that began on the fringes of the less heavily urbanized West and culminated in the older, more heavily urbanized East. Cities along the northwestern frontier in Britain, northern Gaul, and Germany rapidly declined at an early date. Between 400 and 500, urban life disappeared in these areas. Many sites were abandoned altogether, but some places, such as London, York, and Augusta Treverorum, survived mainly as the locations of major churches and ecclesiastical residences.

Even Rome had practically collapsed by 550. During Justinian’s Gothic War, its population may have been reduced to 20,000, and Procopius reports that at one point it was abandoned. After 600, Rome seems to have been primarily a site of monasteries and churches inhabited by clerics and a few Byzantine officials.

In Roman North Africa, Carthage decayed badly after Justinian’s reconquest. Many of the occupied areas were abandoned in the seventh century. Burials, which used to be forbidden within the walls of the city, began to intrude upon ruined structures. After it fell to the Arabs in 698, it was abandoned altogether. By the time of the Arab Conquest, Lepcis (Leptis) Magna, on the coast between Carthage and Cyrene, had shrunk from a city covering 320 acres at its height to only 70.

In general, the cities of the East fared much better than those of the West in the fifth and sixth centuries. The cities of the northern Balkans, however, went into decline when the Huns and Ostrogoths invaded in the second half of the fifth century. Greek cities like Athens, Corinth, Argos, and Sparta declined precipitously after the Slavic attacks in the 580s. Athens remained inhabited, but the others were eventually abandoned.

The cities of Asia Minor and the Levant show new building activity accompanying growing wealth and population until the Persian and Arab invasions of the seventh century. Thereafter, rapid decline set in. The Sassanid Persians sacked Antioch in 611, Damascus in 613, and Jerusalem in 614. Between the Persian sack of 616 and the Arab attack of 654/655, the great city of Ephesus shrank to little more than a fortress. The Muslim capture of Alexandria in 642 ended its role as the supplier of grain to Constantinople and caused it to decay.

Constantinople itself had reached its apogee as a Classical city under Justinian. While Rome was shrinking, Constantinople had grown in population to about half a million. During the seventh century, however, as it lost control of the cities from which it drew its wealth, it too began to contract. Preoccupied with its own internal political intrigues and religious factionalism, it had lost the spirit and resources of a Classical city.

Changing patterns of rural settlement

The amount of archaeological information available for the countryside in Late Antiquity is not so great as that for cities, nor is it easy to interpret. Nevertheless, evidence for the transition to later patterns of settlement in the fifth and sixth centuries is beginning to come to light in some places. In the East, the pattern of village-farming life tended to endure in agricultural areas that were still prosperous. In the western provinces, rural life was in a state of flux. In many areas, life on the villa estates of great landowners began to resemble more that of medieval manorialism than that of the rural world in the high Empire.

In Italy, the shift from the Classical pattern of dispersed settlement in open land to the medieval pattern of hilltop villages often occurred. Archaeological surveys in South Etruria indicate a drastic drop in population and the creation of fortified hilltop settlements to protect the area from invading Lombards. A similar trend is evident in the upper valley of the Volturnus River. Although much more work needs to be done to confirm the details and to investigate other parts of Italy, it is safe to say that the transformation from the Classical to the medieval countryside was well underway by 600 c.e.

Attempts to improve the position of women and children in society

In the fifth and sixth centuries, there were attempts at improving conditions for women and children. How much these attempts actually affected the daily lives of most is hard to assess. Still, that efforts were even made is significant.

Emperors could not make up their minds on whether to permit divorce by mutual consent or not. There was always a fear that liberalized divorce would break up families too easily and harm the interests of the children in family property. Theodosius II allowed women to divorce unilaterally because of outrageous infidelity or abuse. Anastasius allowed divorce by mutual consent. In 542, Justinian added impotence to the list of grounds allowing a woman to seek divorce, but he banned consensual divorce and disallowed wife beating as grounds for divorce. (He did, however, institute heavy fines in an attempt to stop husbands from beating their wives.) A year after Justinian’s death, Justin II returned to the more lenient position that men and women should be allowed to dissolve unhappy marriages by mutual consent without formal grounds. Working within a long legal tradition, Christian emperors, even in their most strict legislation, never adopted the teachings of churchmen like Basil of Caesarea, Augustine, or Jerome that a woman could never divorce her husband and that neither could remarry until the other’s death.

Justinian’s legislation made a concerted effort to improve conditions for lower-class women, particularly prostitutes or those equated with prostitutes. There is good reason to believe that the powerful influence of Theodora had something to do with it (p. 674). In 535, Justinian made it a crime to force or trick girls into prostitution. Justinian also tried to protect all women from raptus, which encompassed seduction, abduction, and rape. Contrary to previous law (p. 618), a man who had intercourse with a woman of any class was unable to avoid a charge of stuprum (unlawful intercourse) unless she was his wife. Justinian also put the blame for raptus squarely on the man committing the deed. The penalty was execution. A woman’s relatives or master could summarily kill her raptor if they caught him in the act. If the victim were a slave or freedwoman, the executed man’s heirs could receive his property. A freeborn victim got to keep the executed man’s property plus that of any accomplices, and she was free to marry without stigma. If she were in an adulterous relationship with a seducer, a woman could, if the family wished, be divorced and prosecuted with the man, but she could also simply be given a whipping and sent to a convent for two years. After that, she could return to her husband if he would have her.

Justinian tried to protect the property rights of children in their mother’s family by asserting that consanguinity should be reckoned through females as well as males. He also decreed that a child could not be enslaved to pay off a parent’s debts, a long-standing evil in the ancient world. Finally, he declared that no foundling could be raised as a slave. An unintended consequence, however, might have been a greater reluctance of people to take in exposed infants. On the other hand, the organized efforts of the Church to provide for such infants may have filled any gap.

Romans and Germans

Germanic rule seriously affected western Roman aristocrats. In Gaul, when the Visigoths and Burgundians were settled in Aquitania and Savoy in 418 and 443, the Roman inhabitants had to surrender one-third of their arable land, cattle, coloni, and slaves to the newcomers. Later they had to give up another third. Both the Visigoths and the Burgundians governed the old Roman inhabitants under special, Roman-based codes of law. That not only tended to segregate the Romans and Germans but made disputes between them more complicated. The Visigoths also forbade intermarriage between Romans and themselves.

In Italy, Odovacer took only one-third of each Roman’s possessions for his men, and Theoderic the Amal merely reassigned those thirds to his Ostrogothic followers when he took over in 493. He allowed many landowners simply to pay one-third of their rents as taxes to the king instead of losing the land itself. Theoderic also tried to preserve the Roman administrative system intact and did not segregate the old Roman inhabitants. They could even serve as military officers.

The Vandals under Gaiseric in North Africa confiscated all the property of the Roman inhabitants and probably reduced to serfs those who did not flee. In northern Gaul, the Franks were completely different. After their initial conquests, they left the Roman inhabitants in possession of all of their property.

General relations between old inhabitants of the West and newcomers were frequently strained. The Germanic tribesmen were not used to settled ways and orderly government, despite the earnest attempts of some of their kings to preserve continuity. Germanic officials were just as corrupt as the previous Roman ones. Lawlessness and violence were common everywhere.

Moreover, there was the added problem of the religious differences between the Arian Germans and the orthodox Catholic Romans. Ethnic antagonisms and religious differences tended to become intertwined. The situation was especially acute in the Vandal kingdom, where the kings were particularly fanatical Arians. Huneric banished about 5000 Catholic clergy to the desert and used Catholic bishops for forced labor on Corsica.

The Burgundians, Visigoths, and Ostrogoths were more tolerant and tried to cooperate with the Catholic hierarchy. Unfortunately, King Theoderic of the Ostrogoths found that orthodox clergy cooperated with his enemies. The Burgundian king Gundobad (474–516), former supreme commander at Rome (p. 661), had a better relationship and even allowed his children to be converted to Catholicism. His tolerance had a direct impact on the pagan Franks. Clovis, founder of the Merovingian dynasty of Frankish kings, married Gundobad’s daughter Clotilda. She persuaded Clovis to be baptized as an orthodox Roman Catholic. After that, the Franks converted directly from paganism to Clovis’ new faith. Thus, the foundation was laid for historically significant relations between the Franks and the Church at Rome.

Religion

From Justinian onward, Christians and their controversies increasingly dominated religious life. Justinian’s attempts to root out paganism did not completely succeed but dealt it serious blows. Jews found the state increasingly hostile.

Pagan survivals

Although the public cults and rituals of paganism declined rapidly after Theodosius’ attacks at the end of the fourth century, pagan intellectuals lived relatively undisturbed. Theodosius had not instituted the ancient equivalent of the Inquisition. Only the outward practices of paganism, not belief itself, were attacked. Pagan books freely circulated, and pagan thought still dominated the schools of law, rhetoric, and philosophy, where pagans and Christians freely mingled. During the fifth and early sixth centuries, many high imperial officials, who were usually trained in the schools, continued to be pagans, both openly and secretly. Even after the brutal murder of the pagan scholar Hypatia by the partisans of Cyril in 415 (p. 636), Alexandria remained a center of Neoplatonic thought with an Aristotelian twist. Athens continued as another center of Neoplatonism and even increased its intellectual prestige.

Justinian was the one who initiated what might be called an inquisition to eradicate pagan thought. He encouraged civil and ecclesiastical officials to investigate reports of continued pagan practice and forbade anyone except baptized Christians to teach. When the leaders of the schools at Athens refused to conform, Justinian confiscated the schools’ endowments (529). Some of the scholars fled to the court of Chosroes I in Persia but soon found life uncongenial there. Chosroes did them one great service, however: in his treaty of 532 with Justinian, he stipulated that they be allowed to return to the Empire and live in peaceful retirement.

Justinian also sought to root out the paganism that had persisted among the simple folk of the countryside. He sent out aggressive officials to close out-of-the-way shrines that had escaped previous attempts at closure. He supported wide-ranging missionary activities to convert the unconverted. The task was made easier because there had already occurred a certain synthesis of Christian and pagan practices. The former simple services of the Primitive Church had now given way to more elaborate ceremonies that included the use of incense, lights, flowers, and sacred utensils. A myriad of saints and martyrs had taken over the competing functions of many pagan deities and heroes. It is no mere coincidence that the Parthenon at Athens, home of Athena the Virgin (Parthenos), became a church of the Virgin Mary; that the celebration of the Nativity came to coincide with the date of Mithras’ birth and the season connected with pagan celebrations of the winter solstice; or that sleeping in a church of Saints Cosmas and Damian could now produce the cures that used to be found in a temple of Castor and Pollux. Nor would the distinction between theurgy and the celebration of the Eucharist be clear to the unsubtle mind.

Christian heretics and Jews

Many developments in late imperial Christianity involved heresies and schisms such as Arianism (p. 587), Monophysitism (p. 665), and Donatism (pp. 586–7). They have been discussed in chapters on the political events with which they were intimately bound because they had aroused popular passions. Other heresies have been noted in connection with religious developments during the third century (pp. 553–4).

In the early fifth century, the Pelagian heresy is worthy of note. It raised fundamental questions about sin and salvation that have exercised Christian thinkers ever since, although it did not touch off any great popular conflict at the time. The Church taught that saving grace could be obtained through only two sacraments, baptism and penance: baptism, which could not be repeated, would wash away the taint of Adam’s original sin and any personal sins incurred in this life up to the moment of baptism; penance could eliminate those committed thereafter. As a result, in the fourth century, many who espoused Christianity put off baptism until the last possible moment in order to die sinless in a state of grace. After baptism in childhood or early adulthood became more common in the fifth century, penance was relied on as the means of wiping out sins committed before death. Therefore, many people paid little attention to the strict Christian moral code. They lived just as sinfully as non-Christians. Indeed, there was even less need to show restraint because they knew that all could be wiped away by baptism or penance.

Among those who were troubled by this unedifying state of affairs was a Welsh layman named Morgan, later known as Pelagius. He denied the doctrine that Adam’s original sin derived from his nature and was transmitted to posterity. Therefore, he argued, it was possible to gain salvation through one’s own efforts in leading a righteous life. Pelagius’ views were originally accepted in the East, but St. Augustine (pp. 703–4) led an attack on them in the West at a council in 416. Eventually, after numerous intervening councils, they were condemned at the Third Ecumenical Council at Ephesus in 431.

Justinian, in his zeal to achieve “one Church and one Empire,” was anxious to root out heretics as much as pagans. He barred heretics from the professions of law and teaching, forbade them the right to inherit property, and would not let them bear witness in court against orthodox persons. He even instituted the death penalty for Manichees and relapsed heretics.

Justinian was no friend of the Jewish population either. For centuries, the Greek and Jewish communities in the cities of the East had been at odds over the rights and duties of citizenship. At times they even rioted against each other. With the Greek population becoming more and more Christian, however, the explosive element of religious hatred made things worse. At Alexandria, for example, riots between Christians and Jews gave the newly elected bishop Cyril an opportunity to solidify his leadership of the Alexandrian church. He increased its power in the city by conducting a virtual pogrom against the Jewish population. It was Hypatia’s support of the imperial prefect’s efforts to curb Cyril’s violence that led to her murder in 415 (p. 636).

Justinian abandoned the secular toleration that the Roman government had traditionally maintained toward Jews. Although he did not forbid orthodox Jews to practice their religion, he subjected them and Samaritans to the same civil disabilities as heretics. These policies resulted in two serious revolts of Jews and Samaritans in Palestine in 529 and about 550. They produced much bloodshed and no relief for the oppressed.

The new cultural spirit

The tree planted during the cultural revival of the fourth century continued to grow in the fifth and sixth, but as cities declined, it increasingly required the special environment of a church, cloister, or ruler’s court to flower. On the stock of elite pagan rhetoric, philosophy, literature, and art, Christianity had grafted the traditions of those formerly on the social and geographical fringes of the Roman world. The pagan stock still produced new shoots, but they were completely overshadowed by the luxuriant growth of the new graft, which transformed the cultural landscape of the age. It was a landscape dominated by theological debate, experiencing holy mysteries, discovering allegories, and a sense that, in the face of change, what was useful from the past needed to be collected before it was lost.

Latin poetry

Despite the internal conflicts and disruptive invasions of the fifth century in the West, pagan and Christian Latin poetry flourished.

Claudian (ca. 370 to ca. 404 c.e.) and Namatianus (d. after 416 c.e.)

Two poets who represent the old pagan stock in Latin literature are Claudius Claudianus and Rutilius Namatianus. Claudian was a pagan Greek from Alexandria and became the court poet of Honorius and Stilicho. He wrote in Latin and produced highly polished classicizing poems in praise of his two patrons and members of their families. Rutilius Namatianus was a wealthy pagan from Gaul, a member of the old Gallo-Roman elite. He left Rome in 416 to attend to his Gallic estates, which German raiders had badly damaged. He described his journey in the long elegiac poem De Reditu Suo (On His Return) that gives a moving tribute to the city of Rome and keenly observes the country through which he passes, but he crudely condemns the “barbarian” Stilicho, Judaism, monasticism, and all else that he saw as destroying paganism and the Empire.

Paulinus of Nola (353–431 c.e.)

A famous younger Christian contemporary is Paulinus of Nola (Meropius Pontius Paulinus). A wealthy Gallo-Roman, he was a prized pupil of Ausonius (pp. 634–5). Consul at Rome (378) and then governor of Campania, he married a wealthy woman from Spain. They eventually settled in the Campanian town of Nola. There, they devoted themselves to the cult of St. Felix of Nola. Each year for the saint’s feast day, Paulinus composed one of his Natalicia, poetic sermons that use rural themes and everyday experiences to communicate Christian ideas to the pagan peasants. Paulinus’ large correspondence links him not only with Ausonius, but also with many of the leading Christian figures of his day like St. Ambrose, St. Augustine, St. Jerome, Melania the Elder, and Melania the Younger.

Sidonius Apollinaris (ca. 430 to ca. 480 c.e.)

Like Paulinus, Bishop Sidonius Apollinaris of Clermont (Augustonemetum) near Gergovia (p. 719), had given up a prominent public career for the Church. He saw Classical culture and Christianity as allies against uncouth invaders. The twenty-four poems of his Carmina include occasional poems reflecting his social world and others in praise of the emperors Avitus (his father-in-law), Majorian, and Anthemius (pp. 660–1). Of great historical value are the nine books of letters that he published as bishop.

Dracontius (ca. 455–ca. 505 c.e.) and Corippus (fl. 540–570 c.e.)

Blossius Aemilius Dracontius and Flavius Cresconius Corippus were products of the late Roman literary culture of North Africa. Dracontius, a wealthy landowner from Carthage, wrote a number of poems on both pagan and Christian themes. His long poem The Tragedy of Orestes and two short epics (epyllia) On the Rape of Helen and Medea show his deep engagement with Classical mythology. His On the Praises of God celebrates the benevolence of God toward the pious. He also invokes Christian themes in the Satisfactio, a poem in which he asks pardon for offending a Vandal king.

Corippus had held some imperial offices before he left North Africa for the court at Constantinople. There, he continued the Latin Classical tradition with Vergilian-style historical epics: one about John, general in the Moorish War, and the other a celebration of Emperor Justin II.

Fortunatus (ca. 530 to 600 c.e.)

The last significant poet of the sixth century was Venantius Honorius Clementianus Fortunatus (p. 672). Born near Treviso in northeastern Italy, he received a solid Classical education at Ravenna. As a young man, he traveled across Germany and Gaul and eventually settled at Poitiers. There he became a bishop and close friend of both Gregory of Tours (p. 705) and the influential Merovingian queen Radegunda. Eleven books of his poems survive. They include panegyrics on various Merovingian kings, epitaphs, consolations, religious poems and hymns, and verse biographies of Radegunda and St. Martin of Tours.

Latin prose

The greatest Latin authors of the fifth and sixth centuries wrote in prose. Their works included history, biography, philosophy, theology, sermons, and letters. They are rich sources for the history of Rome in the West during these centuries.

St. Jerome (ca. 347 to ca. 420 c.e.) and St. Augustine (354 to 430 c.e.)

The two greatest masters of late Latin prose were St. Jerome and St. Augustine. Educated at the height of the fourth century (see p. 629), they wrote in the early fifth and reflected high Classical standards. As Paulinus of Nola advocated, however, they applied their skill on behalf of propagating the faith. Yet, steeped as they were in the Classical tradition, they were devastated by the sack of Rome in 410.

Jerome (Sophronius Eusebius Hieronymus) was born at Stridon in Dalmatia and educated at Rome. As a young man, he traveled and studied in the Greek East. After learning Greek, he returned to Rome and rose to prominence as secretary to Pope Damasus I. Damasus asked him to undertake his most enduring work, the Latin translation of the Bible, commonly known as the Vulgate. For that task, he learned Hebrew in order to read the Hebrew Scriptures. Jerome was also a prolific commentator on the Bible and a harsh polemicist in theological debates. He carried on many of his disputes through a vast correspondence with people like St. Augustine. These letters and his historical works (p. 509) make him a major witness to his age.

Augustine (Aurelius Augustinus), bishop of Hippo Regius in Africa Proconsularis, is the greatest example of the complex blend of pagan learning and Christian faith, at least in the West. Born of a pagan father and a Christian mother at Thagaste, about one hundred miles south of Hippo, he studied rhetoric at Carthage. Then, he went to Rome to make his mark. There, he became acquainted with Symmachus and his circle. Through them, he gained appointment to a professorship of rhetoric at Milan. He was greatly influenced in thought and style by Cicero. He was also a Manichee before he became an orthodox Christian. His conversion took place at Milan through association with St. Ambrose, who was part of an influential circle of Christian Neoplatonists.

Augustine’s voluminous letters, sermons, and commentaries show the influence of pagan Classical literature and philosophy everywhere. Two works stand out—his Confessions and his magnum opus, the Civitas Dei (City of God). The former traces his intellectual and spiritual development from a callow student smitten with Cicero to a Manichee, to a Neoplatonist, and finally to a baptized Christian. The latter work was stimulated by Alaric’s sack of Rome in 410 and the flood of upper-class pagan refugees to Africa. Their presence threatened to undermine the recently won supremacy of orthodox Catholicism in his region.

In his best Latin rhetorical style, Augustine met them on their own terms. He made a systematic critique of the ancient myths and historical views on which they based their paganism. His refutation of Neoplatonism was philosophically rigorous. Even in arguing for his radically Christian view of reality, however, he argued on the basis of shared concepts, such as Divine Providence and the quintessentially Classical sociopolitical concept of the civitas, a community of citizens. For Augustine, the Christian is a citizen of God’s perfect heavenly community and longs for it while he or she dwells as a resident alien in this earthly community. Yet, Augustine does not reject the earthly city. As part of God’s creation, it is good, though not perfect. The good Christian, while enjoying its virtues, can work to eliminate its faults. There is no puritanical rejection of the Classical civitas that pagans loved. It is simply augmented by the vision of another that is even better.

Rufinus (345 to 410 c.e.)

Rufinus of Aquileia had been a friend of Jerome and was primarily a translator of Greek works, particularly Origen’s (p. 560), which otherwise would be lost. Jerome’s eventual doubts about the orthodoxy of Origen offended Rufinus and triggered a nasty dispute. Rufinus also translated Eusebius’ Ecclesiastical History into Latin and extended it to the death of Theodosius I.

Orosius (ca. 390 to after 417 c.e.) and Salvian (ca. 400 to ca. 480 c.e.)

Augustine’s younger friend Paulus Orosius, a priest from Spain, wrote theological treatises and a seven-volume history of man, the Historia adversus Paganos. He wrote it for Augustine to use in writing the City of God. Orosius argued that God had created the Roman Empire in order to spread Christianity and that Romano-Christian culture would eventually absorb the Germanic invaders. Salvian of Marseilles, however, declared in his De Gubernatione Dei (On the Governance of God) that God had sent the invaders to punish sinful Christians.

Gregory of Tours (538 to 594 c.e.)

Gregory, bishop of Tours (Limonum) in Merovingian Gaul, was a prolific writer of verse and prose. His poems are lost. Of his prose works, the most important is his History of the Franks. It begins with Adam but concentrates on the murderous doings of the Merovingian Franks. To Gregory, their bloody crimes are earthly episodes in the struggle between good and evil, which eventually will be won by good, represented on earth by the Church.

Martianus Capella (fl. ca. 435 c.e.)

A pagan resident of Carthage, Martianus Capella is another representative of the vibrant Latin culture of late Roman Africa. He wrote between the sack of Rome (410) and that of Carthage (439) and sought to sum up the essence of Classical culture in an encyclopedic work entitled On the Marriage of Mercury and Philology. Heavy with allegory, it reflects the religious-mystical world of Late Antiquity. It also establishes the model for the medieval educational curriculum based on the seven liberal arts: the trivium of grammar, dialectic, and rhetoric plus the quadrivium of geometry, arithmetic, astronomy, and music.

Boethius (ca. 480 to 524 c.e.)

Boethius is one of the great preservers of the Classical tradition in the sixth-century West. He was a philosopher from the Anicii family (p. 615) and had enjoyed the patronage of King Theoderic in Ostrogothic Italy. He was later executed on suspicion of treason. Attempting to sum up the best of ancient thought, he wrote on mathematics, music, Aristotle, and Cicero and had started the monumental task of translating all of Plato and Aristotle into Latin. He also wrote defenses of the orthodox view of the Trinity. His most popular work is the Consolation of Philosophy, written to comfort himself in jail. There, in a dialogue with the allegorical figure Philosophy, he espouses many pagan philosophical views that show how blurred the distinction could be between Neoplatonic paganism and Christianity.

Cassiodorus (487 to 583 c.e.)

Of a distinguished Italian family related to Boethius, Cassiodorus was one of the last holders of major Roman offices in the West. He became a consul, master of offices, and praetorian prefect. He published two historical works, the Chronica, which is a world history from Adam to 519, and the lost History of the Goths, which was used by Jordanes in his work on the Goths (p. 651). Cassiodorus also published the Variae which contains 468 official letters written while he was a high official in Ostrogothic Italy. Upon retirement, he founded a monastery in Bruttium, where he promoted the study and preservation of literature and useful knowledge that would enable the Romans and Germanic newcomers in Italy to forge a new nation. His treatise Educational Principles of Divine and Secular Literature was widely used as a guide to reading in the Middle Ages.

Isidore of Seville (Hispalis) (ca. 570 to 636 c.e.)

Bishop Isidore of Seville is most famous as an encyclopedist. He also wrote an important historical account of the Goths, Vandals, and Suevi as well as a Chronica and De Viris Illustribus. Succeeding his brother as bishop of Seville in 600, he worked hard to promote orthodox Catholicism in alliance with the Visigothic throne, but he also embraced ancient learning. He summarized rational explanations of natural phenomena in his De Natura Rerum, dedicated to King Sisebut in 613. In 620, the king commissioned an even greater encyclopedia, the Etymology or Origins. Unfinished when Isidore died, it was edited into twenty books. Through etymology, he tries to get back to and preserve the original meaning of the words that embody the skills, techniques, and tools essential for maintaining civilization.

Classicizing Greek poets

The rigorous paideia maintained in the Greek cities continued to produce writers who could mimic the ancient Classics with ease. Much of their work has an artificial air. Sometimes, however, there is real merit.

Quintus of Smyrna (fl. ca. 350 c.e.) and Nonnus (fl. ca. 400 c.e.)

Quintus of Smyrna wrote a sequel to the Iliad, often called Posthomerica. It fills the gap between the Iliad and the Odyssey by recounting such things as the death of Achilles and the building of the Trojan horse. Less traditional in subject is Nonnus, a Christian from the Egyptian Thebaid who flourished around 400. A master of Greek epic verse, he paraphrased the Gospel of John in meter. His magnum opus, however, is an amazing epic in forty-eight books on the life and loves of the god Dionysus, the Dionysiaca. Thoroughly pagan in spirit, it weaves together mythological traditions from Egypt, India, and the Near East and revels in lush sensuality.

Minor Greek poets of Late Antiquity

A collection known as the Greek Anthology preserves a large number of clever epigrams in Classical style from a collection called The Cycle, authored by a number of high-ranking officials at Justinian’s court. One of them, Paul the Silentiary, composed an excellent epic description of Justinian’s great church Hagia Sophia for its second consecration in 562 (p. 711). He also wrote love poetry that has been much imitated by later writers.

Finally, a poem that has inspired countless retellings is Musaeus’ romantic Hero and Leander, which tells how the young Leander is smitten by the beautiful Hero when he sees her at a religious festival. He convinces her of his love and swims across the Hellespont each night to join her secretly in her family’s lofty tower by the shore. One night, overpowered by a storm, he drowns. When Hero spies his body washed up below, she hurls herself from the tower to join him in death.

The late Greek historians

History is the premier Greek genre in the fifth and sixth centuries and is represented by several important authors.

Olympiodorus (fl. 410 to 425 c.e.) and Zosimus (fl. 490 to 520 c.e.)

A pagan Greek from Egyptian Thebes, Olympiodorus wrote a detailed account of the western Roman Empire for the period from 407 to 425. Significant fragments preserved in writers like Zosimus show that he was a serious and thoughtful historian. Zosimus was an official of the imperial treasury in the late fifth and early sixth centuries. His New History is an account of the Roman Empire from Augustus to Alaric’s sack of Rome in 410. It is particularly valuable for the third, fourth, and early fifth centuries in the East. Zosimus used now-lost sources like Dexippus (p. 558), Eunapius (p. 635), and Olympiodorus. Zosimus was outspokenly anti-Christian and constantly blamed Rome’s troubles on neglect of the old gods.

Socrates (ca. 380 to 450 c.e.)

The most significant church historian of the mid-fifth century was Socrates Scholasticus. His Church History continues Eusebius from 306 to 439. He was not a cleric, but an advocate at Constantinople. A well-read student of philosophy, theology, and logic, he respected Hellenism and brought a balanced sense of judgment to his work. That quality and his careful citation of sources make him particularly valuable.

Sozomen (ca. 400 to 460 c.e.) and Theodoret (393 to ca. 460 c.e.)

Another layman writing ecclesiastical history in Constantinople was Sozomen. He drew heavily on Socrates Scholasticus for his Church History and covered almost the same period (325–425). The Syrian bishop Theodoret of Cyrus (393–ca. 460) wrote another Church History covering virtually the same period as Socrates and Sozomen (323–428). As a bishop and theologian deeply involved in the controversy between Nestorius and Cyril over the nature of Christ (p. 667), Theodoret had an interesting perspective on the history of doctrinal issues. His History of the Monks of Syria, which includes three women as subjects, is an important source for the ascetic movement in the East.

Evagrius (ca. 535 to 600 c.e.)

A later church historian from Syria was the well-connected advocate Evagrius at Antioch. He admired Eusebius, Socrates, Sozomen, and Theodoret. He continued their work in his Church History from 428 to his own time. He carefully quoted his sources but was too credulous at times. He was hostile to the Monophysites and attacked the anti-Christian views of Zosimus. Pessimistic about people’s ability to control events, he ascribed many things to God.

Procopius (ca. 500 to 565 c.e.) and Agathias (ca. 530 to ca. 582 c.e.)

The outstanding figure of late Greek secular historiography is Procopius. An advisor to the great Belisarius, he chronicled the age of Justinian (p. 672). The last secular Greek historian of the sixth century was Agathias. A lawyer and an official at Constantinople, he was also one of the love poets at court. He edited The Cycle, which contained many of his own poems. After Procopius died, Agathias decided to write his own militarily oriented History. His interest in the Franks and Persians and his use of Persian sources make him valuable. Unfortunately, when he died he had written only five books. They cover the campaigns of Narses in Italy and the end of the Lazic War.

Philosophy

Alexandria and Athens remained centers for Neoplatonic pagan philosophers. The distinction, however, between Neoplatonism and Christianity became more and more blurred. Philosophers and theologians shared the same intellectual world.

Synesius of Cyrene (ca. 370 to ca. 414 c.e.)

A good example of someone in whom Neoplatonism and Christianity tended to merge is Synesius, an aristocrat from Cyrene in the province of Libya. After studying with the pagan philosopher Hypatia in Alexandria, he successfully represented Libya at Constantinople in a plea for a reduction of its taxes. Later, he organized local efforts to defend Libya from the attacks of Berber tribes. Christians in Libya were so impressed with his leadership abilities that they insisted on electing him bishop of the important city of Ptolemais in 410. Synesius agreed only on the condition that he would give up neither his wife, who was a Christian, nor some of his most cherished philosophical beliefs. In return, he accepted basic Christian doctrines like the Resurrection. He wrote some typical rhetorical/philosophical essays on subjects like kingship and the decline of humanistic learning in the face of Christian asceticism and peasant superstition. He also wrote hymns that show his poetic talent and an important collection of 156 letters that provide a valuable look at life in his part of the late Roman world.

Proclus (ca. 410 to 485 c.e.) and Simplicius (ca. 490 to 560 c.e.)

There were no major original thinkers in the fifth and sixth centuries, but Proclus, who headed the Academy in Athens, was a significant synthesizer. He wrote commentaries on some of Plato’s dialogues and compiled encyclopedic works on physics, Platonic theology, and astronomy. Living a very ascetic, monkish life and even writing Neoplatonic hymns, he, too, illustrates the shared religious-mystical views of the day. Another important commentator was Simplicius. He studied at both Alexandria and Athens in the sixth century and wrote extensively on Aristotle. After Justinian officially ended the teaching of philosophy in Athens, Simplicius somehow kept on working. There is even a hint that he established a new school at Carrhae (Harran) in Persian territory.

Theology

By this time, it was very difficult to separate philosophy and Christian theology. The Platonists and Aristotelians, for example, presented questions that Christian theologians had to confront and ideas that they could use. Many of them were relevant to the Christological debates over the nature of Christ that dominated Greek theology in the fifth and sixth centuries.

John Philoponus (ca. 490 to ca. 470 c.e.)

The great rival of the Neoplatonists was John Philoponus, a Monophysite Christian and an Aristotelian. He was the principal philosopher at Alexandria. It is understandable that, as a Christian, he would attack Proclus’ belief that the world had no beginning.

Cyril (ca. 375 to 444 c.e.), Nestorius (ca. 381 to 451 c.e.), and John of Antioch (d. 441 or 442 c.e.)

The fifth- and sixth-century Christological debates began with the dispute between Bishop Cyril of Alexandria and Bishop Nestorius of Constantinople over granting Mary the title Theotokos, “Mother of God” (p. 665). Nestorius, no original theologian himself, came from Antioch, where some theologians taught that Christ was the true union by association of two personal subjects, one human and one divine. Cyril, ally of Pulcheria, wanted to assert the supremacy of his bishopric over Antioch and Constantinople. He speciously accused Nestorius of teaching the heresy that Christ comprised two separate persons (p. 667). Bishop John of Antioch naturally allied with Nestorius against Cyril. After Nestorius was condemned at the Council of Ephesus (431), John and Cyril reached a compromise called the Formula of Union (p. 667). Some of Nestorius’ supporters, however, did take what is called the Dyophysite (two separate natures) position to the heretical extreme that Christ was two persons and established a separate Nestorian church that Nestorius himself never supported.

Pseudo-Dionysius, ca. 500 c.e.

Works spawned by the bitter Christological debates of the fifth and sixth centuries fell into obscurity once the politics that drove them were settled by the Arab Conquest. On the other hand, one of the most influential theological works from this period is a collection of spurious writings by an author purporting to be a first-century Athenian Christian named Dionysius and once thought to be St. Paul’s convert Dionysius the Areopagite. He is now called Pseudo-Dionysius and was really writing around 500. He was trying to reconcile Christianity and Neoplatonic philosophy. The ideas expressed are heavily influenced by the teachings of Proclus. They teach the Neoplatonic idea that God cannot be known directly and interacts with people through a series of nine angelic emanations. Contemplation and prayer, however, can free the soul for ecstatic union with God.

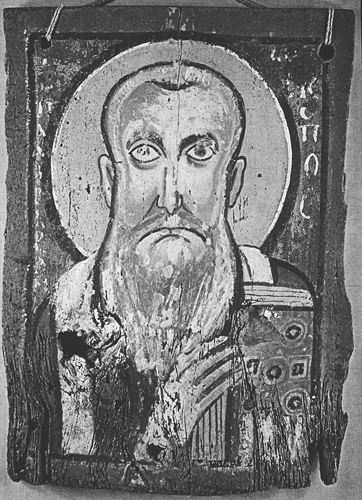

FIGURE 37.1 Bishop Abraham, sixth- or seventh-century icon from Middle Egypt.

Art and architecture

After 395, little new ground was broken in architecture until the time of Justinian. Except at Constantinople, there was little building activity beyond defensive works and churches. From the time of Constantine onward, great works of art from pagan temples were carried off to decorate the buildings of the New Rome. Despite official attempts to preserve the great monuments of the past, many old pagan temples were used as quarries for the building of Christian churches. Early Christian churches generally adopted the style of the Roman basilica, a simple rectangular building with arched windows, a semicircular apse at one end, and a pitched wooden roof. Eventually, side aisles were added, and then in Justinian’s Church of the Holy Apostles at Constantinople, two short wings or transepts were added near one end to produce a plan in the shape of a cross.

Hagia Sophia

Justinian’s Church of Hagia Sophia (Holy Wisdom) set a whole new style of church architecture. The best available architects, Anthemius of Tralles and Isidore of Miletus, were in charge of building a new Hagia Sophia to replace the one destroyed in the Nika Rebellion (pp. 677–9). Anthemius, who had specialized in domed churches, conceived the novel plan of combining a domed roof with a floor plan in the shape of a Greek cross. It was about 250 feet by 225 feet with a dome above the 100-foot square where the arms intersected.

The outside, as became typical of Byzantine churches, was plain, but the interior was richly decorated. Different-colored marbles from around the Empire were used for pillars and floors and to sheathe the walls. The domed ceiling was covered with pure gold, and huge mosaics decorated the church throughout.

The new Hagia Sophia was dedicated on December 26, 537. Unfortunately, however, Anthemius and Isidore had miscalculated the stresses in its innovative design, and the dome eventually collapsed in 558. Isidore the Younger built a new dome over twenty feet higher to provide more vertical thrust. It was finished in 562 and has endured to this day.

Decorative arts

Under the patronage of the Church, emperors, kings, and the wealthy few, the decorative arts reached new heights during the fifth and sixth centuries. There were gold and silver plates with finely chased reliefs; goblets, chalices, crosses, and crowns encrusted with gemstones; exquisitely carved ivory plaques and containers; richly embroidered tapestries and robes; elaborately designed rings and jewelry; fancy reliquaries; beautifully decorated books; and lavishly wrought icons, wall paintings, and mosaics. All were marks of piety and status.

Icons received particular attention during the fifth and sixth centuries. An icon is the image (eikon in Greek) of a particularly holy person, object, or scene. Icons were often painted on wooden panels with egg tempera or molten wax (encaustic). Their use stems from the cultural traditions of Egypt and the Near East, which influenced the Hellenistic and Roman practice of creating similar portraits of gods, emperors, kings, officials, and renowned men of letters. These Classical and pre-Classical predecessors often influenced the pose, grouping, and symbolism found in Christian icons. For example, the popular icon of the seated Virgin holding the infant Jesus child on her lap has its parallel in similar Egyptian depictions of Isis and Horus, her son.

FIGURE 37.2 Deesis mosaic, 12th–13th century, showing Emperor Commenos II, Virgin Mary, Jesus Christ, and Empress Irene, Hagia Sophia, 532–37, by Isidore of Miletus and Anthemius of Tralles, Istanbul, Turkey. © Manuel Cohen/Art Resource, NY.

By the fifth century, the popularity of icons increased as people began to believe in their ability to ward off evil. During the next century, it was common to bow and genuflect before icons. A cult of icons emerged, supported by theological speculation of a Neoplatonic bent about the relationship of an image to what is being imaged.

Icons employed the same flat, perspective-less, otherworldly style popular in wall paintings and mosaics during the fourth century (pp. 639–40). Their otherworldly quality was enhanced by powerful symbols, rich color, and a skillful handling of light. The combination of color and light is particularly impressive in the mosaics of the period. Subtle patterns created by richly colored bits of glass and stone make them glow with inner life. Many stunning examples can still be found at Ravenna in churches like San Vitale and Sant’Apollinare in Classe from the time of Justinian.

FIGURE 37.3 Mosaic depicting Justinian and attendants and Saint Maximian. San Vitale, Ravenna, Italy.

FIGURE 37.4 Mosaic of Theodora with attendants, San Vitale, Ravenna, Italy.

To enter these sanctuaries is to enter a completely different world from that of the first Roman emperor 600 years earlier. The pieces of the mosaic that constituted Roman culture had been rearranged into a very different pattern. Still, something of its substance remained, and memories of the old pattern endured.

Suggested reading

Mitchell , S. A History of the Later Roman Empire AD 284–641: The Transformation of the Ancient World. Blackwell History of the Ancient World. Malden and Oxford: Blackwell Publishing, 2007.

Wickham . C. Framing the Early Middle Ages: Europe and the Mediterranean, 400–800. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005.