Chapter 7

This and the next four chapters cover the period between 264 and 133 b.c.e. when the Roman Republic was at its height in many ways. By 264, the internal social and political struggles of the early Republic had largely abated. To preserve unity, patrician leaders had gradually agreed to grant important men from plebeian gentes equal access to the social and political levers of power. The acquisition of booty and territory from conquered neighbors had helped to alleviate the economic distress of the poor. Therefore, between 264 and 133 b.c.e., the Roman political system remained basically stable under the control of the new patricio-plebeian consular nobility in the senate.

Yearly warfare had practically become a way of life during the early Republic. Citizens of all classes had become accustomed to the profits of war, and aristocratic leaders craved military glory and benefited politically from the popularity won in victorious campaigns. By 264 b.c.e., the Republic had expanded militarily and diplomatically into the unchallenged leader of peninsular Italy. Subsequently, the Romans fought a series of wars that carried their power beyond peninsular Italy and resulted in the acquisition of a Mediterranean-wide empire.

With this empire came an acceleration of the integration of Roman culture and Hellenistic Greek civilization. (The term Hellenistic is used to designate the distinctive phase of Greek civilization that flourished after the conquests of Alexander the Great [d. 323 b.c.e.], when many non-Greek peoples adopted numerous elements of Classical Greek civilization.) In 264 b.c.e., Hellenistic influences permeated political, economic, and cultural life in much of the world from the Himalayan Mountains in the East to the Atlantic coast of Spain in the West. After 264, Roman culture, too, developed rapidly under the tutelage of Hellenistic Greeks. Their poetry, drama, history, rhetoric, philosophy, and art provided the models for Romans to produce a distinctive Greco-Roman civilization that characterized the Mediterranean world for the rest of antiquity.

Finally, the Republic’s Imperial success precipitated social, economic, and political changes that set the stage for its own destruction during the century after 133 b.c.e. Although Rome’s conquests provide an interesting narrative, their impacts on the nature of the Republic itself are also worth studying.

Sources for Roman history from 264 to 133 b.c.e.

At this point in Roman history, there are, for the first time, fairly reliable written sources of information. The early annalistic writers used by Polybius, Livy, and others were contemporaries of this period. They had either personally witnessed the events of which they wrote or learned of them directly from those who had. Polybius himself had come to Rome in 168 b.c.e., almost a century after the outbreak of the First Punic War (264 b.c.e.). His brief account of that war and his detailed description of the Second Punic War and Rome’s subsequent conquest of the Mediterranean world are quite reliable. Unfortunately, his work is intact only to the year 216 b.c.e. (Books 1–6) and preserved only in fragments—a term that scholars use to describe both passages of lost works preserved as quotations in other authors and bits of text preserved on damaged parchment and papyrus—down to its end with the events of 145/144 b.c.e. (Books 7–40). Livy, however, who extensively used Polybius as well as Roman annalists, is complete for the years 219 to 167 (Books 21–45). Some of the lost books of his history are known through summaries (called Periochae) and epitomes of Roman history written in the late Empire (p. 398).

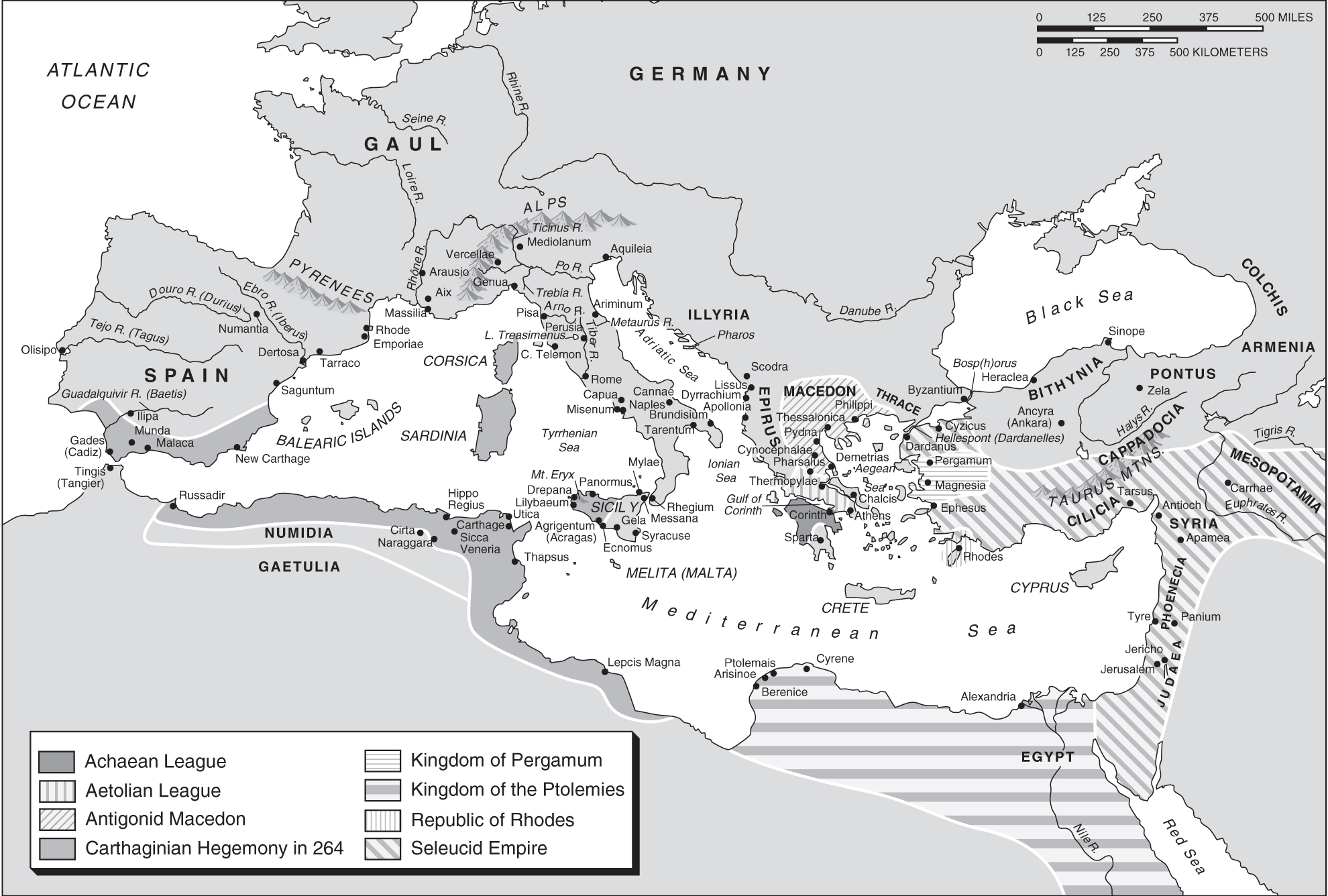

FIGURE 7.1 The Mediterranean world, ca. 264–200 b.c.e.

For events from 167 to 133 b.c.e., we must rely on later and, in some instances, less reliable sources such as the brief account by Velleius Paterculus (early first century c.e.), whose sources are unclear. More reliable are the histories of several Greek writers who drew on earlier Roman material: Cassius Dio, Diodorus Siculus, and Appian. Also useful are the biographies of some of the most important Roman and Carthaginian figures of the period by Cornelius Nepos and Plutarch. The Greek geographer Strabo and the Greek traveler Pausanias also preserve some details.

With this period, for the first time, there are contemporary works of literature, such as the plays of Plautus and Terence, that help to illuminate the life and culture of the period (pp. 199–200). Contemporary coins not only illustrate economic history but also reveal much about the officials who issued them and the places, events, and concepts depicted on them. Inscriptions—texts carved in stone or metal or (more rarely) painted on walls and objects—are also more numerous in this period. They preserve the texts of treaties and laws and the epitaphs that help to reconstruct the political relationships and careers of famous people and the daily lives of ordinary people. Finally, extensive archaeological excavations at Rome, Carthage, and hundreds of other sites around the Mediterranean reveal much about social, economic, political, and cultural trends.

A new chapter in Rome’s expansion

The fateful year 264 b.c.e. emphatically punctuates the completion of Rome’s control of peninsular Italy with the destruction of the rebellious Etruscan city of Volsinii (Orvieto). At the same time, it opens up a new chapter in the expansion of Rome’s power with the start of the First Punic War. Like ever-widening ripples from a stone dropped in a quiet pool, Roman power had moved outward from its central location. It had already reached the southern tip of Italy when the Greek city of Rhegium (Reggio di Calabria) had accepted Rome’s protection as an ally in 285. In 264, the ripple would spread across the three miles of water known as the Straits of Messana (Messina), which separate Rhegium from Sicily, where Punic Carthage was extending its sway.

Carthage

By this time, Carthage had become a major Hellenistic power. It had never been conquered by Alexander the Great nor had it ever inherited any part of his conquests. Still, it had been extensively influenced by the Greeks through constant commercial contact and rivalry in the western Mediterranean, particularly on the strategically located island of Sicily. It was separated from Cape Bon, near Carthage, by only ninety miles of open water. The upper classes had adapted Greek models in government, agriculture, skilled crafts, architecture, dress, jewelry, art, metalware, and even language. Soon Carthage and Rome, which was rapidly rising in the same Hellenistic world, would become locked in a titanic struggle that would make Sicily Rome’s first overseas conquest.

Phoenician Tyre had strategically located Carthage on the coast of North Africa where the Mediterranean Sea is at its narrowest. Therefore, Carthage was in an ideal position to dominate Phoenician trade between its eastern and western ends. Later, Carthage had settled its own colonists on the island of Melita (Malta), just below the southeast corner of Sicily. As a result, Carthage also held a strategic advantage over the Greeks, who were the Phoenicians’ toughest commercial and colonial rivals in the western Mediterranean. Carthage could force the Greeks to access the west through only the dangerous narrow straits between Sicily and Italy.

When Tyre had weakened in the seventh and sixth centuries b.c.e., Carthage had become a power in its own right (pp. 18–9). To protect and expand their mercantile interests, the favorably situated Carthaginians created a navy second to none in the Mediterranean. Eventually, they incorporated former Phoenician colonies and other peoples in North Africa and the Iberian Peninsula into an empire that also included Sardinia, Corsica, parts of Sicily, and the Balearic Islands.

Carthaginian wealth and trade

Carthage controlled the richest mining resources of the western Mediterranean basin. Sardinia and Spain produced lead, zinc, copper, tin, iron, and silver. From Gades (Cadiz), on the Atlantic coast of Spain, the Carthaginians had access to tin from Cornwall and could sail south along the Atlantic coast of Morocco and perhaps down the West African shore as far as the mouth of the Senegal River to obtain gold, ivory, slaves, and war elephants.

By the third century, Carthage’s workshops were turning out jewelry, ivory work, pottery, metal goods, and highly prized purple-dyed cloth in great quantities. An even greater source of wealth was the export of Carthaginian agricultural products: wine, olive oil, and various fruits like pomegranates and figures. Carthage did not have a monopoly on western sea lanes, but it was a formidable commercial force and eager to secure its advantage whenever it could.

Agriculture

The contribution that the Carthaginians made to scientific agriculture and especially to the unfortunate development of slave-worked plantations is usually ignored. They taught the Romans the technique of organizing large masses of slave labor on agricultural estates or plantations for the production of single marketable crops or staples. The slave trade and the use of slaves as farmhands and shop workers were well known in Greece and other ancient countries. Still, slave labor was never able to compete on a large scale with the labor of freeborn individuals in Greece, in the Seleucid Empire, or in Ptolemaic Egypt. The Carthaginians relied on Greek and Hellenistic treatises for the scientific cultivation of specific farm crops. On their own, they worked out a system for the large-scale use of slave labor.

Carthaginian government

As described by Aristotle in the fourth century b.c.e., Carthage was an aristocratic republic that had both democratic and oligarchic features. The details are not always clear, but four elements stand out: a popular assembly; a senate; a supreme court of 104 picked men; and elected officials, including generals and 2 annual chief magistrates called “judges” (shophetim in Punic and suf(f)etes in Latin). The popular assembly elected the generals and judges from a small group of wealthy commercial and landowning families who constituted a powerful oligarchy that also dominated the senate and supreme court. The senate, guided by an executive committee of thirty, and the judges presented questions to the assembly only if they could not agree. The supreme court kept the judges and generals in check.

The navy and army

Carthage, a seafaring city, manned its large navy with loyal citizens commanded by naval experts. Unlike Rome, however, Carthage did not have an extensive rural population of citizens from whom to recruit its armies. Therefore, the army contained few citizen troops. It was composed largely of conscripted natives of Libya, Sardinia, and Spain; troops hired from the allied but independent chiefs of what are now Algeria and Morocco; and mercenaries picked up in every part of the Mediterranean. It was difficult to maintain the army’s loyalty when Carthaginian prestige or funds were low. Moreover, a successful general might be accused of dictatorial ambitions before the supreme court; an unsuccessful one might be nailed up on a cross to appease popular anger. The loss of experienced leadership could be critical at times.

Sicily and the outbreak of the First Punic War, 264 b.c.e.

Until 264 b.c.e., the western Greek cities of Italy and Sicily had been Carthage’s major rivals in the western Mediterranean. For over 200 years, the Carthaginians and the Greeks of Sicily had been fighting for control of that rich and strategically located island. During that period, the Carthaginians had cultivated good relations with the Romans, as indicated by the various treaties that had regulated their commercial and state relations in 509(?), 348, 306, and 279 b.c.e. (pp. 112–3). In 279, they had even found a common interest in the war against Pyrrhus, who threatened Rome’s interests in southern Italy and Carthage’s in Sicily. Polybius, however, emphatically contradicting the pro-Carthaginian historian Philinus, denies that any treaty ever defined the two powers’ respective interests so sharply that the Romans were barred from using arms anywhere in Sicily and the Carthaginians from anywhere in Italy (Book 3.26.1–7). Whether Polybius is right or wrong is largely irrelevant. Many Romans were aware that, treaty or no treaty, they would be in danger of provoking Carthage to war if they sent troops to Sicily in the situation that confronted them in 264.

The Mamertines

That situation resulted from the actions of the Mamertines, a group of Campanian mercenaries. They had once been hired to fight for Syracuse, the greatest Greek city founded in Sicily (p. 20). Later, in 289 b.c.e., they had deserted and seized the strategic town of Messana, in the northeastern corner of Sicily, on the straits that bear its name. The Mamertines had killed the men, taken their women, and had begun to plunder Syracusan territory periodically. Around 265, the Syracusan general Hiero inflicted a great defeat on the Mamertines. He won such popularity that he was able to make himself king at Syracuse as Hiero II. In 264, the remaining Mamertines, still in control of Messana, decided that they needed outside help to stave off any further attacks from Syracuse. One group appealed to the Carthaginians and another to the Romans. A Carthaginian commander who had a fleet nearby quickly responded to the first group’s request. He garrisoned Messana’s citadel with part of his forces, and Hiero refrained from taking any further action against the Mamertines.

Debate and the decision for war in Rome

Meanwhile, the Mamertines who had requested help from Rome had sparked a long and difficult debate in the Roman senate. Polybius mentions two countervailing views that could not be reconciled (Book 1.10.1–9). On one side, many argued that it was beneath the dignity of Rome to ally with the Mamertines. Their crimes at Messana had been equal to those of some allied Campanian soldiers whom Rome had recently punished at Rhegium (Reggio), just across the straits, in 270 b.c.e. Others were afraid that if Rome did not aid the Mamertines, Carthage would use Messana as a base for subduing Syracuse and the rest of Sicily that they did not already control. Since Carthage already held Sardinia, Corsica, and extensive territories in Spain and North Africa, adding all of Sicily would make the Carthaginians very powerful and dangerous neighbors. Although Polybius does not say so, there were senators of Campanian origin who may have felt a kindred sympathy toward the Mamertines. Probably a number of senators argued that Rome needed to prevent the Carthaginians from gaining control of the Straits of Messana, or else they would be able to interfere with the shipping of Rome’s southern Italian Greek allies, Carthage’s traditional competitors. Still others may well have felt that without an adequate navy and already faced with a rebellion in Italy at Volsinii, Rome was in no position to risk a major overseas war with a great naval power like Carthage. Among the senators who would have risked war, there may have been those looking forward to winning glory and spoils in Sicily. Some opponents may have been concerned that such a war would enable an ambitious general to acquire political advantage over his peers in the senate. Many may have argued that Rome should finish the existing war against Volsinii first. In the end, a majority of senators did not approve aid for the Mamertines.

According to Polybius (Book I.11.1–3), however, the consuls, who were favorable toward aiding the Mamertines, brought up the matter before the voters (he does not specify in which assembly). With a second war to fight in their year of office, the consuls could each look forward to all of the advantages of a military victory. They pointed out to the voters the potential threat that Carthage would pose if it gained control of Sicily. Also, they reminded the voters of the rich spoils awaiting those of them who would end up fighting if it came to war with Carthage in Sicily. Those who served in the Roman army had become used to profiting from almost yearly warfare. Many would have remembered how Pyrrhus had tried to make use of Sicily against Rome only a dozen years before. Indeed, after almost continuous struggles with neighboring peoples in Italy, the Romans had developed an almost paranoid fear of powerful neighbors. Many voters may also have been mindful of Rome’s need to protect the interests of allied Greek cities in southern Italy against their commercial rival Carthage.

Finally, although no ancient source mentions it, another consideration may have been a need to secure better access to supplies of grain for feeding Rome’s rapidly growing urban population. Rome was already importing grain from places along the western Mediterranean coast, but treaties with Carthage limited Roman access to the richest western sources in Sardinia, Sicily, and North Africa. A desire to end that situation also could have fostered a willingness among many Romans to go to war.

Appius Claudius Caudex invades Sicily

The consul Appius Claudius Caudex (a grandson of the famous censor of 312 b.c.e.) was appointed to assemble an army, cross over to Sicily, and place Messana under Roman protection. While Appius was preparing to transport his army from Rhegium to Messana, the pro-Roman Mamertines managed to induce the Carthaginian commander to withdraw his garrison. They urged Appius to cross over quickly and take his place. Perhaps the Carthaginian commander hoped that if he left Messana, the Romans would be content to remain in Italy. His superiors, however, were enraged at his failure to hold Messana. They crucified the man, stationed a fleet between Messana and the forces of Appius at Rhegium, and sent an army to retake Messana. Hiero II, allying himself with Carthage in this effort, brought up the Syracusan army and attacked Messana from his direction.

At the same time, Appius made a daring night crossing from Italy to Sicily. He avoided the Carthaginian fleet and landed his forces at the harbor of Messana. His attempt to procure the withdrawal of either the Carthaginians or Hiero through negotiations failed. Therefore, acting boldly while his troops were still fresh and before his supplies ran out, Appius first attacked and defeated Hiero, who quickly withdrew to Syracuse. Then, on the next day, Appius turned against the Carthaginians and defeated them. The First Punic War had begun, with momentous consequences for the history of Rome, Carthage, and the whole Mediterranean world.

The Carthaginian view

The Carthaginians, although not prepared for a major war, had to risk fighting. Despite any legalistic interpretations that could have been given to existing treaties, the Romans appeared to be the aggressors. They had no previous interests in Sicily, whereas the Carthaginians had long been one of the dominant powers there. To have tolerated Roman interference would have made the Carthaginians appear weak and unwilling to protect their interests in a situation where justice seemed to be on their side. Moreover, to have negotiated any agreement based on Roman claims of a protectorate over the Mamertines would have left the Mamertines free to cause trouble in Sicily under the umbrella of Roman power. From the Carthaginian perspective, therefore, the Romans had to be opposed.

Initial Carthaginian setbacks, 263 and 262 b.c.e.

Unfortunately for Carthage, most of its warships had been lying in storage ever since the Pyrrhic War. Ships had to be refitted; crews had to be recruited and trained. Meanwhile, Appius Claudius Caudex had laid siege to Carthage’s ally Hiero II at Syracuse. Hiero was already alarmed that Carthaginian forces had not even been able to prevent Appius’ main army from crossing the straits in 264. He was totally disillusioned when he did not receive the expected support against the Roman siege. Consequently, he negotiated a peace with the Roman consul who replaced Appius Claudius Caudex in 263. The peace was to run for fifteen years, and Hiero agreed to help Rome against Carthage. Therefore, in 262, he aided the Romans in capturing the Carthaginian stronghold of Agrigentum (called Acragas by the Greeks, Agrigento in modern Italian).

Expansion of the war

After the fall of Agrigentum, the Romans saw the possibility of driving the Carthaginians out of Sicily altogether. The obstacle was the Carthaginian fleet. Once it was fully ready for action, it threatened to cut communications with Italy and starve the Roman army into surrender. It also raided Italian coastal cities. The Romans must already have realized that they needed to match the Carthaginian navy at all costs or else get out of the war.

Rome builds a new fleet, 261 b.c.e.

The small navy that had served Rome during the Second Samnite War and the war with Pyrrhus (pp. 109–11) probably had been abandoned. Even if it still did exist, it would not have been adequate for an overseas war. The navies of allied Greek city-states in Italy had transported the Roman armies to Sicily. Their light triremes had been sufficient before Carthage had mobilized its full naval power, which was based on the heavy quinquereme, heavy and strong warships manned by multiple units of five rowers spread across anywhere from one to three banks of oar and fronted with a great bronze beak used for ramming and sinking other ships.

Polybius tells the famous story that the Romans used a captured Carthaginian quinquereme as a model and built one hundred quinqueremes along with twenty new triremes while new rowers trained in simulators on the shore (Book 1. 20.9–16). That they did it in sixty days from the cutting of the trees as Pliny the Elder claims (Natural History 16.192) seems impossible. It would have taken many months to cut and season timber; produce the ropes, sails, and fittings; and gather the number of skilled workers needed for such a large project.

It may be more accurate to say that the Romans assembled the ships in sixty days. The Carthaginian ship that they used as a model had been captured three years earlier. In the meantime, the Romans probably acquired raw materials and stockpiled various components prefabricated according to standard patterns based on the captured ship. When there were enough, the components could then be assembled quickly into complete ships.

To the bows of their new ships, the Romans added a device that the Athenians had tried during their disastrous expedition to Sicily (415–413 b.c.e.). It was a hinged gangplank raised upright by ropes and pulleys attached to the mast. After an enemy ship was rammed, this gangplank was dropped onto the disabled ship’s deck. Roman marines would rush across to fight as they would on land. The end of the plank had a grappling spike, or beak, to hold on to the enemy ship so that it could not slip off the Roman ship’s ram and escape. This spike gave the device its name, corvus (crow or raven). Although it served its purpose very well, it rendered Roman ships unstable in high seas when it was raised upright for transport.

A titanic struggle, 260 to 241 b.c.e.

A war of titans commenced in 260 b.c.e., when the new Roman fleet defeated the Carthaginians in a great naval battle off Mylae, not far from Messana. The triumphant Romans erected a column decorated with the rams (rostra) of captured Carthaginian ships near the speaker’s platform in the Forum. After failing to adapt to Roman tactics and losing another sea fight off Sardinia in 258, the commander of the Carthaginian fleet was crucified.

The Roman invasion of Africa, 256 to 255 b.c.e.

Having established sudden naval superiority, the Romans planned a massive invasion of Africa itself to end the war quickly. In 256, the Romans set sail with 250 warships, 80 transports, and about 100,000 men. They defeated another Carthaginian flotilla off Cape Ecnomus, on the south coast of Sicily, but new Carthaginian tactics began to counteract the corvus.

The Roman consul M. Atilius Regulus landed in Africa in the autumn of 256 b.c.e. He inflicted a minor defeat on the Carthaginians. Thinking that they were just about ready to give up, he offered them terms of peace so harsh that they were rejected. Though winter would have been the best season to fight in Africa, Regulus decided to wait until spring. Meanwhile, the Carthaginians had not been idle. They had engaged the services of Xanthippus, a Spartan strategist skilled in the use of the Macedonian phalanx and war elephants. New mercenaries were hired, and many Carthaginian citizens volunteered for service. All that winter, the work of preparation and training continued unabated.

In the spring of 255 b.c.e., Regulus advanced into the valley of the Bagradas but found the enemy already waiting for him. Here Xanthippus had drawn up his phalanx—elephants in front and cavalry on the wings. The Romans suffered a catastrophic defeat. Only 2000 men managed to escape. Regulus himself was taken prisoner along with 500 of his men. The dead probably numbered 10,000 or more.

A Roman armada sent to rescue survivors defeated another Carthaginian fleet and sailed off with the remnants of Regulus’ army. As the Romans were approaching the shores of Sicily, a sudden squall caught the ships made top heavy by the corvus. All but 80 of 364 ships according to Polybius’ account (Book 1.37.2) sank or crashed on the rocks with an estimated loss of 100,000 men. In 253, a similar disaster occurred.

The war in Sicily, 254 to 249 b.c.e.

After 255, Sicily and its surrounding waters remained the sole theater of military operations. Capturing Panormus (Palermo) in 254, the Romans drove the Carthaginians out of the island, except for two strongholds at the western tip—Lilybaeum and the naval base of Drepana (Trapani)—both of which they blockaded by land and sea. The Carthaginians concentrated their main effort on expanding their empire in Africa and stamping out native revolts in order to secure their resources at home. In 249, however, they regained the initiative against Rome.

Carthaginian success at sea, 249 to 247 b.c.e.

As the Romans had rebuilt their navy after the disasters of 255 and 253 b.c.e., they had abandoned the corvus. The Carthaginians had devised successful defensive tactics against it, while its height and weight made ships very vulnerable to storms at sea. In 249, the poor tactics of the consul Publius Claudius Pulcher (see Box 7.1) resulted in the loss of 93 out of 120 Roman ships off Drepana (Trapani). The version of events told by our ancient sources, however, blame not Claudius’ ineptitude but his arrogance in angering the gods before the battle. A second Roman defeat soon followed Claudius’ debacle: the other consul’s enormous fleet was completely destroyed, partly by Carthaginian attack and partly by storm. For the next few years, the Carthaginians had undisputed mastery of the sea. They were now able to break the Roman blockade of Lilybaeum, cut communications between Rome and Sicily, and make new raids upon the Italian coast itself.

7.1 The importance of the auspices

The Romans believed that their success as a society was due to the fact they were beloved of the gods and that this was the result of their correct worship of them. The story our Roman sources report about the Battle of Drepana is a classic Roman illustration of what could happen when the gods were displeased.

Before setting off to battle, Publius Claudius Pulcher did what was required of every Roman commander: he took the auspices, that is, he consulted the gods to see if they were in favor of the action he planned. The Romans had numerous ways to do this (see p. 69); Claudius used one of the methods favored by commanders in the field. He ordered the sacred chickens to be let out of their crate. He hoped to see them gobble down the special meal that had been scattered on the ground for them—the best possible sign was if a chicken ate so fast that whole pieces of food dropped from its mouth and hit the ground. Unfortunately for Claudius, he received the worst sign: the birds would not eat. (Since he took the auspices on board his ship and since chickens are not seabirds, the animals were likely seasick.) In such circumstances, protocol dictated that Claudius wait twenty-four hours and then try consulting the gods again, but his anger and impatience got the better of him. He threw the uncooperative birds overboard, shouting “Since they will not eat, let them drink!” The near total loss of his fleet in battle later that day was thus divine retribution delivered through the Carthaginian fleet.

Hamilcar Barca and ultimate Carthaginian failure, 247 to 241 b.c.e.

Never had the picture looked brighter for the Carthaginians, especially after they had given the young Hamilcar Barca, the most brilliant general of the war, command of Sicily in 247 b.c.e. His lightning moves behind Roman lines and daring raids upon the Italian coast made him the terror of Rome. Well did he merit the name of Barca, Baraq (Barak, Barack) in Punic, which means “blitz” or “lightning.”

Despite the brilliance of Hamilcar Barca and the amazing successes of the Carthaginian navy, Carthage lost the war. It was unable to deliver the final blow when Rome was staggering in defeat. Rome’s ultimate victory was not wholly due to doggedness, perseverance, or moral qualities, as has often been suggested. Carthage was weakened by an internal division between the commercial magnates and the powerful landowning nobility.

A landowning group headed by Hanno the so-called Great had prospered with the conquest of territory in North Africa. To this group, the acquisition of vast territories of great agricultural productivity in Africa was more important than Sicily, the navy, and the war against Rome. It came into control of the Carthaginian government at the very moment when the Carthaginian navy and the generalship of Hamilcar Barca seemed about to win the war. That this new Carthaginian government was not interested in winning the war was clearly evident in 244 b.c.e. The entire Carthaginian navy was laid up and demobilized. Its crews, oarsmen, and marines were transferred from the navy to the army of African conquest.

Meanwhile, the Romans saw that their only chance for survival lay in the recovery of their naval power. They persuaded the wealthiest citizens to advance money for the construction of a navy by promising to repay them after victory. In 242, a fleet of 200 Roman ships appeared in Sicilian waters. In the following year, on a stormy morning near the Aegates Islands, it encountered a Carthaginian fleet of untrained crews and ships undermanned and weighted down with cargoes of grain and other supplies for the garrison at Lilybaeum. The result was a disaster for Carthage that cost it the war. The garrison at Lilybaeum could no longer be supplied. There was no alternative but to sue for peace.

Roman peace terms, 241 b.c.e.

The Carthaginian government empowered Hamilcar Barca to negotiate peace terms with the consul C. Lutatius Catulus, the victor of the recent naval battle. Both sides were exhausted. The Roman negotiators, well aware of the slim margin of victory, were disposed to make the terms relatively light. Carthage was to evacuate Lilybaeum, abandon all Sicily, return all prisoners, and pay an indemnity of 2200 talents (presumably silver) in twenty annual installments (a talent equals about twenty-five kilograms or sixty pounds). These terms seemed too lenient to the Roman voters, who had to ratify the treaty in the comitia centuriata. They increased the indemnity to 3200 talents to be paid in ten years. The Carthaginians were also required to surrender all islands between Sicily and Italy, keep their ships out of Italian waters, and discontinue recruiting mercenaries in Italy.

The impact of the First Punic War

As in all major wars, the victors and vanquished alike were profoundly affected and underwent significant changes. First of all, the war had exacted enormous tolls in men and matériel on both sides. Although casualty figures are often grossly inflated by ancient sources, Rome and Carthage each had lost hundreds of ships and tens of thousands of men. Thus, the lives and livelihoods of many parents, wives, and children were devastated, with lasting consequences for their communities and societies as a whole.

At the state level, Rome had gained its first provincial territory, Sicily. It also became a major naval and international power. Eventually, it was unable to remain uninvolved in the affairs of the wider Mediterranean world even if it had wanted to. Many Romans probably were suspicious of Carthage and feared that it might someday seek to even the score. Others had found their appetite for conquest whetted and wanted more.

The sea power of Carthage was broken, and its naval dominance of the western Mediterranean was ended for all time. Some Carthaginians resented their humiliating defeat and hoped someday to restore Carthaginian prestige abroad. Others continued to concentrate on the intensive agricultural development of the territory around Carthage. More immediately, however, Carthage suffered a major crisis because of its inability to pay the mercenary troops that made up the bulk of its army. The temptation to take advantage of this situation at Carthage’s expense eventually proved too great for a number of Romans to resist.

The Truceless War and Roman trickery, 241 to 238 b.c.e.

No sooner had the Carthaginians made peace with Rome at the end of the First Punic War than they had to fight their own mercenaries. Returning from Sicily, 20,000 mercenaries demanded their accumulated pay and the rewards promised to them by Hamilcar Barca. The Carthaginian government, then dominated by unsympathetic landlords such as Hanno the Great, refused. The mercenaries mutinied and were joined by the oppressed natives of Libya, the Libyphoenicians of the eastern part and the Numidians of the western. The mercenaries became masters of the open country, from which Carthage was isolated. It was a war without truces and was, therefore, known as the Truceless War. A similar revolt subsequently broke out in Sardinia.

Hanno assumed command of the army, but his “greatness” failed to achieve any military success. The situation deteriorated until Hamilcar Barca took command. Three years of the bloodiest fighting followed. Crucifixions and all manner of atrocities were committed on both sides until Hamilcar, finally with Hanno’s cooperation, stamped out the revolt.

Carthage received the unexpected sympathy and help of Rome, which furnished it with supplies and denied them to its enemies. Rome permitted the Carthaginians to trade with Italy and even to recruit troops there. It also rejected appeals for alliance from the rebels of Utica and Sardinia. After the revolt against Carthage had been stamped out in Africa, however, a faction unsympathetic to Carthage gained the upper hand in the Roman senate. As Hamilcar was moving to reoccupy Sardinia in 238 b.c.e., this group, “contrary to all justice,” in the words of the usually pro-Roman Polybius (Book 3.28.2), persuaded the senate to listen to the appeal of the Sardinian rebels, declare war on Carthage, rob Carthage of Sardinia, and demand an additional indemnity of 1200 talents.

Carthage gave in to Roman demands because it had no fleet and could not fight back. Losing Sardinia also meant that Carthage could no longer enforce any claim to neighboring Corsica, which the Romans invaded in 236. The natives of both Sardinia and Corsica fought ferociously against Roman occupation. Many continued to resist Roman authority long after the two islands were grouped together as the second Roman province in 227 b.c.e.

Roman conquests in northern Italy

Important Roman senators may have feared that, in the wrong hands, Sardinia and Corsica could be used to disrupt efforts to secure the northern frontier of Italy against the Gallic tribes of the Po valley. The Romans called that area Gallia Cisalpina, Cisalpine Gaul (Gaul This Side of the Alps). They had been fighting tribes from that region on and off since the time Brennus and his Gallic warriors had sacked Rome (pp. 102–3). Therefore, they always looked upon these people with fear and suspicion. There were two keys to holding the Gauls in check. One was Rome’s stronghold at Ariminum (Rimini), a colony on the extreme southeastern corner of the Po valley. The other was the mountainous territory of Liguria in the southwest corner of continental Italy. Liguria blocked the western end of the Po valley and controlled the upper part of the route that ran north from Rome along the west coast of Italy. Still free of Roman control, Liguria would have to be conquered to secure the northern frontier against the Gauls or anyone else who might invade peninsular Italy from that direction.

In 241 b.c.e., before the formal end of the First Punic War, the Romans began laying the groundwork for their campaigns in the North by securing vital communications routes. They found an excuse to make war on the Faliscans, whose fifty-year treaty with Rome had run out two years before. The Faliscans’ major stronghold, the fortified city of Falerii, was only about forty miles north of Rome. It was very close to the route of what would become the great Via Flaminia north from Rome through Umbria to the Adriatic coast and on to Ariminum. The Romans destroyed Falerii and moved its inhabitants to a less strategic spot three miles away. They also founded a colony at Spoletium in Umbria to protect the area through which they had to pass on the way to Ariminum.

At the same time, they began to build the great Via Aurelia northwest from Rome up the coast of Etruria to the colony of Cosa. Cosa was well fortified to protect both the land and sea routes to and from Liguria. Both of these routes could easily be attacked from the islands of Sardinia and Corsica. Northern Sardinia is only about 130 miles from the coast of Etruria, and the northern tip of Corsica is only about fifty miles from Populonia on the coast north of Cosa. Strategically minded Romans may well have feared that when they began the conquest of Liguria, the Ligurians would try to ally with the Carthaginians on Sardinia to harass Roman lines of supply and communication. Therefore, it scarcely seems coincidental that the consul Tiberius Sempronius Gracchus both led the Roman occupation of Sardinia and initiated the conquest of Liguria in 238 b.c.e.

In that same year, a Roman army based at Ariminum also started campaigning against the Gallic Boii at the eastern end of the Po valley. That campaign, in turn, provoked other Gauls, including transalpine tribes. Perhaps emboldened by the return of now-unemployed Gallic mercenaries who had served Carthage during the Truceless War, they joined with the Boii to attack the Romans at Ariminum in 236. Internal dissension among the Gauls led to their defeat. An uneasy truce during the next eleven years became even more uneasy in 232, when an ambitious tribune named C. Flaminius obtained passage of a law giving individual Roman settlers large amounts of land confiscated from the Boii fifty years earlier south of Ariminum.

The pirates of Illyria, 229 and 228 b.c.e.

Successful campaigns in Sardinia and Corsica in 231 b.c.e. and Liguria in 230 finally enabled the Romans to turn their attention to the festering problem of Illyrian pirates in the Adriatic. Previously, the maritime Greek cities of southern Italy had lost their independence, and Rome had become preoccupied with Carthage in western waters. In the meantime, the notorious pirates of Illyria, along the eastern coast of the Adriatic, had grown ever bolder. Queen Teuta, who had been expanding her Illyrian kingdom south to Epirus and the Gulf of Corinth, had been unable or unwilling to stop them. With the Greeks grown weak, pirates roved the seas at will, attacked not only Greek, but also Italian, ships and captured or killed their crews. Growing ever bolder, they ransacked towns along the Adriatic shores of southern Italy. The Romans were bound to protect the interests of their allies and could not tolerate attacks on Italy itself.

In 230 b.c.e., the Roman senate dispatched two envoys to lodge complaints with Queen Teuta. When pirates killed one of the envoys, the Romans responded swiftly. In the summer of 229 b.c.e., a fleet of 200 Roman ships appeared off the island of Corcyra (Corfu). Demetrius of Pharos, whom Teuta had charged with the defense of the island, betrayed her and surrendered to the Romans without a fight. The fleet then sailed north to support a large Roman army attacking the towns of Apollonia and Dyrrhachium (Durazzo). Teuta sued for peace in 228. She retained her crown on condition that she renounce her conquests in Greece, abandon all claims to islands and coastal towns captured by the Romans, and agree not to let more than two Illyrian ships at a time sail past Lissus, the modern Albanian town of Alessio. For his treachery, Demetrius received control of Pharos and some mainland towns.

Renewed war with the Gauls, 225 to 220 b.c.e.

The Romans do not seem to have had any territorial goal in Illyria. They wanted to suppress piracy and establish friendly client relations with those rulers and communities in the region who were willing to keep the Adriatic safe for the ships of Rome and its allies. Of much more pressing concern to the Romans were the Gauls in northern Italy. Mutual fear, suspicion, and even hatred drove the actions of both as they tried to strengthen themselves against one another. By 225 b.c.e., each side had built up massive armies ready to strike. The Boii and three other Gallic tribes in the Po valley plus some allies from the Rhone valley across the Alps contributed to the Gallic army. To counter them, the Romans had stationed two large armies in the north. An army of two legions and an even larger number of allied troops waited at Ariminum under the command of L. Aemilius Papus. Another large force, mainly of allied troops, was positioned on the northern border of Etruria under the command of a praetor.

Leaving part of their forces to protect the Po valley, the Gauls struck first. They followed the route down through Etruria that Brennus had taken over 160 years earlier. The Roman praetor caught up with them near Clusium and fell into a trap. He suffered serious losses before he was rescued by Aemilius Papus, who had rushed south with the army from Ariminum. The Gauls decided to cut westward and retreat up the Via Aurelia with Papus in hot pursuit. Meanwhile, Rome’s other consul, C. Atilius Regulus, who had been campaigning in Sardinia, landed his army at Pisa and marched south to intercept the fleeing Gauls. Trapped between the two Roman armies at Telamon, just north of Cosa, the Gauls fought furiously. They even managed to kill Regulus but ultimately were almost annihilated. Out of 50,000 Gauls, only 10,000 survived.

Subsequently, Aemilius Papus and then the consuls of 224 b.c.e. completely defeated the Boii in the Po valley. In 223, the consul C. Flaminius, who had obtained the law giving Gallic land to Roman settlers in 232 b.c.e., scored a major victory against the Insubrian Gauls. After more Roman victories in 222 and 221, all of Cisalpine Gaul was under Roman control. After being elected censor for 220, Flaminius initiated construction of the great paved road named for him, the Via Flaminia from Rome to Ariminum, and founded the colonies of Cremona and Placentia, which anchored Roman control of the central Po valley.

Pirates again, 220 to 219 b.c.e.

The hasty measures of 229 and 228 b.c.e. in Illyria had not solved the problem of Adriatic piracy. Demetrius of Pharos proved to be a very unreliable Roman client. Antigonus Doson, acting king of Macedon, disliked Roman interference in Balkan affairs. Conspiring with Doson, Demetrius stealthily extended his kingdom. After Teuta’s death, he invaded the territories of those friendly to Rome, attacked Greek cities farther south, and made piratical raids far into the Aegean. The Romans could not overlook these activities. In 220, they launched a campaign to eliminate Demetrius and the pirates. They succeeded in driving out Demetrius, but events of 218 in Spain forced them to abandon any plans of dealing with the situation in Illyria more thoroughly. Meanwhile, Demetrius had fled to the court of Macedon’s new king, the youthful Philip V. Whispering plots of revenge into the young king’s ear, Demetrius remained there for several years.

Rome’s rise as a Mediterranean power surveyed

The Mamertines’ requests for aid from both Rome and Carthage in 264 b.c.e. had pitted the two great republics of the western Mediterranean against each other and touched off the First Punic War. Rome turned itself into a major naval power to overcome Carthage’s advantage at sea. It was able to use its massive reserves of manpower and matériel in Italy to overcome staggering losses and exhaust the will of the increasingly divided Carthaginians to carry on the fight by 241.

Immediately after that, Carthage was further weakened by the Truceless War with its mercenaries. At first, Rome cooperated with Carthage. In 238, the Romans put their own strategic, and perhaps financial, considerations uppermost when they turned on Carthage. They forced it to surrender Sardinia and pay an additional indemnity or face renewed war with them. While taking over Sardinia, and soon thereafter, Corsica, the Romans pursued their previously planned campaigns against the Ligurians and Gauls in northern Italy. In the same period, the Romans mounted brief expeditions to suppress Illyrian piracy (229–228 and 220–219 b.c.e.).

Thus in the space of forty-six years, Rome had risen from a regional power controlling peninsular Italy to a major Mediterranean power stretching from the foothills of the Alps on the north to a point in Sicily only ninety miles from North Africa on the south and from the islands of Sardinia and Corsica on the west to the shores of Illyria on the east. The events in Spain that demanded Rome’s full attention in 218 b.c.e. would launch the Second Punic War with Carthage. That conflict would set Rome on the path to becoming the dominant power in the whole Mediterranean world.

Suggested reading

Hoyos , D. Mastering the West: Rome and Carthage at War. Ancient Warfare and Civilization, Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 2015.

Hoyos , D. Unplanned Wars: The Origins of the First and Second Punic Wars. Berlin and New York: De Gruyter, 1997.

Rosenstein , N. Rome and the Mediterranean, 290 to 146 b.c.e.: The Imperial Republic. Edinburgh: University of Edinburgh Press, 2012.