12

Boris Dreyer

This chapter provides an overview of the known cults for Alexander the Great and his closest family and adherents. With regard to Alexander, Bosworth observes:

Beginning as a Heraclid and descendant of heroes, he had become son of Zeus and competitor with the heroes. Finally he had become a god manifest on earth, to be honored with all the appurtenances of cult. The precedent for the worship of a living man was firmly established, and cults were offered to his Successors with greater frequency and magnificence.

The core question that remains for the current scholarly debate is to what extent the various ways of putting the king on par with heroes and gods were actually contemporary. There is also a need to clarify in detail which of the cults and festivities in the various cities were actually desired by Alexander1 and which were introduced during his lifetime.2 The available evidence, almost without exception, dates to the period after Alexander’s death. The arguments for dating these phenomena within the lifetime of the king are no more than indices. The same is true of the explanations advanced regarding the motives for establishing these honors. There is also a debate as to the extent to which deification stems from oriental/Persian or Egyptian influences on Alexander, and/or whether deification of a living person is reconcilable with Greek thought.3

It is in this context that the disputes over Alexander’s attempt in the year 328 to introduce proskynesis must be seen. Hephaestion had prepared the attempt, with the court historian Callisthenes refusing full implementation. Proskynesis, the forms and variants of which are still intensely disputed,4 was a specific form of symbolic obeisance by the “subjects” (of various legal and social categories) before the Achaemenid ruler, whose tradition Alexander considered himself part of as time progressed (especially from 330) – much to the chagrin of his Macedonian and Greek followers.

In the ceremony that Alexander aimed to introduce, an important role was played by the altar whose eternal flame would cease to burn only when the Great King died (or, as Alexander ordered, on Hephaestion’s death in 324). The king received the guest in the antechamber by drinking from a bowl, which he then passed to the guest. The guest emptied the bowl and bowed (or knelt) before the altar of the eternal flame. Then he would kiss the king on the mouth. Callisthenes’ act of impropriety, for which he fell into disfavor (his final fall from grace occurred in connection with the Pages’ Conspiracy; see Heckel, ch. 4), was his attempt to omit the genuflection in front of the altar when the king was distracted. However, when his refusal was detected, the attempt at introducingproskynesis failed and was never repeated.5 But apart from that, because the Great King had never been divine in the Achaemenid empire, proskynesis could not serve as preparation for divine kingship, according to Persian custom. “Greek authors apparently agree that the Persian monarch was not regarded as divine by his subjects and that proskynesis was not an act of worship. None the less it evoked widespread abhorrence.”6

Even if proskynesis could not serve as a means of deification, Alexander stylized his descent from heroes and gods from an early date. The king identified himself especially with Heracles, Achilles, and Dionysus in two respects:7 on the maternal side he traced his lineage via the Epirote Molossians to the hero Achilles; the Argeads, the ruling house in Macedonia, traced their ancestry back to Heracles. Furthermore, it is abundantly evident from his actions that his motive was to repeat what Achilles, Heracles, and Dionysus had done, or indeed to improve upon their acts.8 After crossing the Hellespont Alexander visited Ilium (see also below) and paid sacrifice at the tomb of Priam to do penance for the actions of his “ancestor” Achilles.9 He granted favors to the Cilician Mallians based on their common descent from Argos,10 and personally led his army into battles in the Hindu Kush, exposing himself to great danger, in order to match up to the models he wished to emulate, namely Heracles and Dionysus,11 though the latter was relevant only to the eastern part of the campaign. One of the aims of his march through the Gedrosian desert was to compete with Cyrus and Semiramis.12 Alexander also frequently appeared in robes and disguises that obviously referred to attributes of the gods that he admired (Hermes and Artemis among others).13

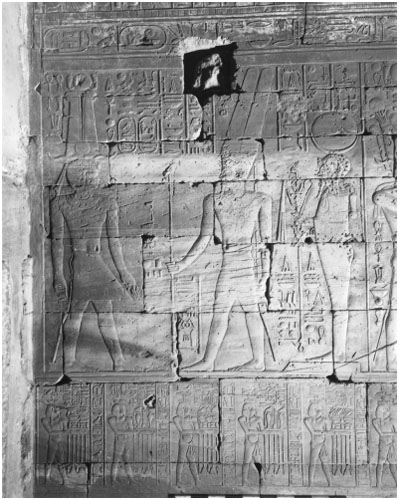

Figure 12.1 Shrine of the Bark: dedicatory inscription of Alexander the Great praising the god Amun-Ra four times, while the nomes bring offerings, c. 330–325 BC. Egypt, Thebes: Luxor Temple. Oriental Institute, The University of Chicago. 38387/N. 43812/CHFN 9246. Photo: The Oriental Institute.

In modern scholarship, however, there are keen debates as to whether the king felt himself to be an incarnation of Dionysus (as the one who successfully reached India), or whether he would not become a Neos Dionysus until after his death. Such identifications, especially in the latter case, depend on how they are presented in the ancient tradition and how far modern accounts rely on the different ancient versions.

The “vulgate” tradition was associated with Callisthenes’ positive image of Alexander, which started with Cleitarchus’ hymnic, transfiguring depiction of the king, which can in turn be found in relatively true-to-original form in the seventeenth book of Diodorus and where an intensification of the Dionysian elements can also be discerned. In the first century, during the period in which the Roman republic was threatened by Mithridates VI Eupator, there was a tendency toward a negative portrayal of Alexander, as reflected by Curtius Rufus in the early imperial age.14 Whatever historical links to Dionysus remain here serve primarily to illustrate the negative characterization of a drunkard. This negative portrayal, however, also had begun immediately after the death of the king in the satirical text of Ephippus, which has as its general theme the deification of Hephaestion and Alexander. The text ridicules comparison with Heracles and his apotheosis, contrasting this with Alexander’s unhistorical demise after drinking from the “Cup of Heracles” during a heavy drinking session.15

As son of the god Zeus, Alexander was raised to the sphere of the gods by the priests of Ammon at the oracular site in the oasis of Siwah.16 He had identified himself as son of Zeus before that, and it was something his mother had also repeatedly emphasized.17The various reports on the Siwah oasis, which contain strong divergences, reflect varying levels of motivation and bias.18 The report by Ptolemy in Arrian19 describes in relatively sober and reserved terms the march, after the founding of Alexandria, to the oasis greatly revered among the Greeks, where Alexander performed a sacrifice to Zeus Basileus. Callisthenes and Cleitarchus embellished this (basic) version, which was familiar with and downplayed the extravagant versions. Cleitarchus, who lived in Alexandria at the time of Ptolemy I, had the founding of Alexandria (April 7, 331) follow the inspirational visit to the oasis,20 which he elevates to a processional oracle according to Egyptian custom.

According to Callisthenes,21 Alexander alone (without his entourage) was allowed into the sanctum of “the father” Zeus by the Egyptian priests, who greeted him, the liberator from the Persian yoke, as the son of Ammon (the Greeks equated Zeus Ammon with the Egyptian Amun Re), that is, as the ruler of Upper and Lower Egypt.22 After the visit references to his being the son of a god did not cease.23 Thus, there would be many occasions on which to establish cults for the son of Zeus.

However, other reasons for dedicating cults to Alexander existed even before this, that is, during the liberation of the cities of Asia Minor.24 The reasons or pretexts for creating a cult cannot be determined directly from the sources except in the rarest of cases, because they reflect the thinking of later periods.25 They may document the cult directly or indirectly, but it is with hindsight, long after Alexander’s death. Nothing demonstrates the popularity of the ruler and the feeling of commitment toward him more than the fact that his cults were being preserved even in the Augustan period and the second century AD. However, we can confidently assume that most of the documented cults had their origins during the lifetime of the conqueror.

Two major occasions for establishing a cult can be identified. The first was the liberation of the Greek cities on the mainland of Asia Minor from the yoke of Persian domination during Alexander’s campaign, beginning in 334/3 (particularly up to the year 332, when Alexander’s gains were irreversible).26 These cities viewed the year 334 as the beginning of a new epoch, which confirms the high esteem in which Alexander’s actions were held.27 These comprised the liberation not only from the Persian yoke, but also from the tyrannies and oligarchies it entailed,28 the collection of tribute,29 and the introduction of democracy. The second occasion (prepared by the first) at which cults were established was Alexander’s own desire for deification; this involved primarily the cities of the Greek mainland (see below).30

One notable example occurs in Alexandria by Egypt (the official designation of the city). Here it was probably only after Alexander’s death that a foundation cult for him was established, with a place of worship at his tomb where the anniversary of his death was celebrated.31

Asia Minor and Aegean Islands

During his conquest of Asia Minor, Alexander acted according to fixed principles. In the non-Greek areas, he encouraged traditional forms of rule and administration. In the Greek cities he had set out to liberate, he promoted the establishment of democracy which he supported with administrative reorganization. Examples of these follow.

As with the most important cities of Caria, Alexander sent delegates to free the cities of Ionia and Aeolia, abolishing the oligarchies that ruled them and the tribute paid to the Persians, and reestablishing their ancestral laws and constitutions.32 Alexandrian games with contests and sacrifices were celebrated by the koinon, presumably on Alexander’s birthday.33 During the early principate, the festival in Alexandria marking the king’s birthday was always celebrated near Teos,34 whereas previously – demonstrably in the third century – the event was hosted alternately by the member states of the koinon. That the event existed in Alexander’s lifetime is not disputed. This league celebration should be distinguished from the Alexander cults that have been shown to exist in the separate member states of the koinon.

In Ilium there is documentary evidence for the existence of the phyle (tribe) Alexandris in this city.35 Thus there existed a cult for the king. Because of the mythical significance of Ilium and Alexander’s self-identification with Achilles, the king had provided repeated favors to the city since his stay there in 334.36 These favors included intensive building activities37 that changed the shape of the city to such an extent that a tribal reorganization of the citizen-body is plausible. The king donated gifts for the consecration of the temple of Athena, declared the city to be autonomous, and freed it from paying tribute. According to sources, Alexander had other great plans for the city. It is also likely that there was a founder’s cult for Alexander in the city.38

The cult of Alexander in Erythrae, for which there is considerable documentation, was also established during his lifetime, as suggested at least by the king’s title associated with the cult. Under Alexander’s rule, the city was freed from paying tribute and became independent.39 The gratitude shown by the city was great, even though the plan to cut through the isthmus was not implemented in the end.40 In 332/1, the sibyl of Erythrae announced that Alexander was the son of Zeus.41 Around 270, the sale of the priesthood of King Alexander is epigraphically docu- mented.42 Habicht argues that the outlays for sacrifices to Alexander after 200 were intended for the city’s own cult, not for the cult of the koinon. 43 An inscription was found on the base of a statue in which agones are referred to as Alexandreia.44 Correctly ascribing this reference is not so easy. An Alexandrian priest, however, still existed in the third century AD.45

The assumption that a cult for Alexander existed in Teos derives from a suggestion by Rostovtzeff concerning an inscription dating from the second century,46 according to which the theos (god) mentioned is supposed to be Alexander. The surrounding area (including Smyrna and Clazomenae) had profited by Alexander’s projects. Though these were left uncompleted, there would be a reason for such an inscription.47 However, the proposed reconstruction of the text cannot be upheld, on account of the remaining letters in the lacuna, and so the origins of the Teos inscription remain by no means certain.

A cult for Alexander has been shown to have existed in Ephesus. A document dating from AD 102–16 in the reign of Trajan, takes the form of a laudatio for T. Statilius Kriton.48 Kriton was the personal physician to the emperor himself, a procurator, and thus priest, of Alexander and of Augustus’ grandsons Gaius and Lucius. This physician was frequently consulted and enjoyed great influence. The link to the Alexander cult of the Augustan period demonstrates the enormous importance of the cult over the centuries. An Alexandrian renaissance began even during (and because of) the reign of Trajan (also in historiography, with Arrian writing his account of the “historical” Alexander and referring to the works of Ptolemy and Aristobulus). The title of “king” suggests the cult was instituted during Alexander’s lifetime (see above, on the cult in Alexandria), presumably on the occasion of his presence in the city in summer 334. According to Arrian, Alexander had released the city from paying tribute and had given it its freedom.49 He introduced democracy and restored to their homes the citizens who had fled from Memnon of Rhodes. The divinity of the king during his lifetime is also suggested by the anecdote by Artemidorus of Ephesus, cited in Strabo.50 According to this story, the Ephesians addressed Alexander as a god, although the context seems to be anachronistic. During Alexander’s lifetime, a painting by Apelles51 was erected in the Artemision in Ephesus, which Alexander had refurbished.52 Although tribute no longer had to be paid, it was replaced by sacrificial offerings. This provided the basis, in 334, for a characteristic element of, and motive for, the subsequent ruler cult in Greek cities of Asia Minor (see Priene).

Among the Greeks of Asia Minor, Philip’s Panhellenic propaganda53 fell on fertile ground, at least by the time of Parmenion’s expeditionary campaign (in 336). The Artemision had already housed a statue of Philip II, but this had been removed by the pro-Persian oligarchs before the city was captured by Alexander and democracy restored.54 The tyrants of Eresus on Lesbos took similar action against the altars of Zeus Philippios, that is, of Philip, shortly before and perhaps even during the campaign in 334.55

Philip’s cults then were treated accordingly by the Achaemenids and their allies, oligarchs, or tyrants in Asia Minor. When Alexander marched into Ephesus, the exiled citizens who had taken Philip’s side and had fled Memnon and his forces (see above) were able to return.56 Until his death in 333, Memnon posed the greatest, though not always the most dangerous, Persian threat to Alexander.

It is possible that Memnon had suppressed a pro-Macedonian, democratic government that had been able to form under the influence of Philip’s troops in 336.57 In Eresus on Lesbos, Philip had played a role in toppling the tyrants and restoring democracy in the year 343; in 337 Eresus was admitted to the League of Corinth. The gratitude of the liberated city, as seen in cult of Philip established no later than 336, is just as understandable as the destructive hatred of the two sets of tyrants who were installed in power by Memnon soon after 335 and again in 333. Cult honors for Philip had to be renewed when these tyrannic regimes fell and (as in Ephesus) when honors for Alexander were established.

Epigraphic evidence shows that Alexander gave the city of Priene its freedom in 334 and showered gifts on the city and temple.58 Unlike the Ephesians, the Prienians did not oppose Alexander’s dedicating of their temple of Athena.59 The city, however, did not join the League of Corinth and this encouraged the pro-Macedonian oligarchs. Established by Alexander’s father, Philip, the League was not well liked among mainland Greeks, and for some Aegean Greeks Persian dominion according to the settlement of King’s Peace of 386 remained an attractive alternative until 332.60Therefore, Alexander distanced himself from the League, liberating the Greek cities in Asia Minor and in many cases establishing democracies. This sharply contrasts with the actions of Philip who preferred oligarchic regimes, as did Antipater, Alexander’s deputy in Greece, although this was contrary to Alexander’s orders.

Additionally, Alexander granted the citizens of Priene other favors, even if he was not necessarily present in the city in person; honors were also bestowed by the city on Antigonus Monophthalmus,61 Alexander’s proxy. It would not be plausible to expect cult honors for Alexander62 later than those for Antigonus.

It has been suggested that the idea to reestablish Priene completely can be traced back to Alexander. Contrary to this, Helga Botermann argues that Alexander arranged only for the completion of a building project that was already under construction by the indigenous Hecatomnids. In other words. he deliberately adhered to local traditions and fulfilled popular expectations.63 The honors accorded Alexander were therefore a consequence of his good deeds and thus anticipate the subsequent cult of the Greek city ruler. This role of benefactor (euergetes) was known to the Greeks almost only theoretically up to this time. Isocrates, in his pamphlet-speech Philippos, attributes this role to Philip, Alexander’s father, outlining Philip’s ideal relationship to the Greeks and his future tasks in organizing the Panhellenic program against the Persian empire.64 This program consisted of three steps: freedom for the Greeks in Asia Minor; the conquest of Asia Minor if possible, in order to settle Greeks there; and, most important of all, the subjection of the Persian empire.65 Therefore, the role of the future pambasileus (on this see below) and his relationship to Greek cities is rooted in Greek intellectual thought of the fourth century.

One document dating from the second century informs us that a dilapidated Alexandreion was restored with private wealth; the Hieron on West Gate Street may have been that building. In any case, a statuette of Alexander, identified with the cult, has been found on that site.66

In Magnesia-on-the-Maeander the founding document for the festival of Artemis Leukophryene in 206 refers to the Alexandreia, that is, the games of Alexander.67 The reason for mentioning the Alexander festival in this context remains unclear. Since the city did not belong to the Ioniankoinon, it is quite probable that these Alexander festivities were not those conducted by the koinon. Alexander had not visited the city in the year 334, but delegates from the city of Magnesia had traveled to Alexander in Ephesus in order to surrender the city to him.68

When the gymnasium in Bargylia and its statue of the king were refurbished in the third century, the cult for Alexander was also revived.69 The gymnasium substituted for the lack of a temple.70 Just as the gymnasium and the theater become a “second agora,” one can also observe that the municipal theater housed cult altars dedicated to the king – as a substitute for a sacred temple.

Contrary to earlier assumptions, the Dionysia and the Alexandreia on Rhodes were also organizationally separate. There were priests71 as well as separate festivities.72 These were amalgamated before 129, because at that time the festivals were held together,73and there is much documentary evidence for their combination.74 However, the Alexander festival did not lose its autonomy and the person being revered was never equated with Dionysus. Tragic plays and chariot races were organized in Alexander’s honor.75

Since 332, there had been intensive relations between the Rhodian republic and Alexander,76 although the extent of the favors bestowed by Alexander has been exaggerated in the legends propagated by Rhodes from the end of the third century onward.77 The legendary descriptions of an exclusively good relationship are qualified by the news that the citizens of Rhodes had driven out the Macedonian garrison after the death of the king, thus regaining their freedom.78 So the question as to when the cult for Alexander was established cannot be answered with any certainty.

F. Salviat has edited a law from Thasos dating from the last quarter of the fourth century, which contains a provision that, among other things, imposed limits on trials on festival days.79 The list of festivals also includes the Alexandreia, which was celebrated on the king’s birthday (6th day in the month of Hecatombaion) – as in the Ionian koinon. This is one of the earliest documents providing evidence of festivities in honor of Alexander. It appears to be either a consequence of the desire for deification expressed by Alexander in the year 324 (see below), or perhaps already a reaction to the Asia Minor campaign in 334, especially in cases of spontaneous introductions – as in the case of the cities in Asia Minor – and celebrations on his birthday. However, it is also possible that the celebrations were introduced after his death.80

The famous regulations in Mytilene on Lesbos probably also belong to an early period (about 332),81 as in the case with Chios.82 These followed the Persian naval offensive, which in spite of its (limited) successes could be regarded a failure as Alexander continued his campaign and conquered all the major harbors of the Levant.83 If this early, not uncontested, date of the document could be confirmed, its contents would be a link between the first and the second period of honors for Alexander, chronologically and geographically. In addition to the care that the well-informed Alexander showed during the settlements – as in the cases of Philippi (331), Chios (334), and later Tegea (324) – the regulations in l. 46 seem to include cultic veneration for the king.84

The Greek Mainland

Alexander’s desire for deification, complemented by Hephaestion’s secondary ascription as theos paredros, or “assistant deity,” was intensely debated in 324, especially in Athens. Alexander’s ancestors had already been accorded cult honors in the cities of Macedonia, namely Amyntas III in Pydna and Philip II in Amphipolis and Philippi. A scholion to Demosthenes indicates a shrine to Amyntas (an Amynteion) in Pydna, into which the inhabitants of the city fled from Philip II.85 The occasion and time at which the Amyntas cult was established are unclear. It survived Athenian rule and certainly the period after its being stormed by Philip. Aristeides also refers in his report to a temple to Amyntas in Pydna and to divine honors for Philip II in Amphipolis.86

This means that the cult for Philip in Amphipolis was already in existence before the city was taken in the year 357. It was introduced after he came to the throne in 360/59. In that year the Macedonian occupation that Perdiccas III had installed against the threat from Athens was withdrawn.87The withdrawal of his army was carried out by Philip as an act of rapprochement toward Athens. However, the regime in power when the city was stormed by Philip in 357 was hostile to the Macedonian king.88 The result was an oligarchic overthrow.89 Thus, it is possible that establishment of the cult was prompted by withdrawal of the occupying Macedonian forces.

In Philippi (Krenides), which had been renamed by Philip in the year 358/7,90 the dating of an Alexander scroll after a priest has been thought to indicate a cult for Philip, which seems likely in a city bearing his name. This epigraphic letter was found with other inscriptions in a sacrificial pit, possibly an area of cult worship, considered by Picard to be a heroon to Philip.91 At any rate, there were at least two temene of Philip II in Philippi.92

After the Macedonian victory in 338/7, Philip II received several distinctions in Athens, at the initiative of Demades. These included citizen’s rights and the erection of a statue in the Odeion. Apsines, however, claims that Demades did not arrange for Philip to be decreed the thirteenth god.93

In contrast, the cultic veneration of Alexander in Athens is documented by a fragment of a speech by Hypereides.94 Hence, the cult for Alexander in fact existed before the end of the year 322, the date of the speech.95 It is clear from the fragment that a cult image, an altar, and a temple were erected in Athens in honor of Alexander. It is also generally assumed that the “servants who were celebrated as heroes” referred to Hephaestion, who was also revered as theos paredros, the “assistant deity” for Alexander. The establishment of this cult shortly before the ruler’s death is very likely already due to this fact alone. On the other hand, revering him as a deity was certainly not part of the honoring of Alexander between 338 and 335 in Athens:96 Hypereides definitely speaks of such a cult being established a short time before.

A debate over the establishment of cults at the king’s behest is documented for Athens and Sparta.97 It is certain that revering the king was practiced in several Greek communities.98 An unspecified number of unnamed cities in Babylon worshiped Alexander as a god. The delegates had the specific title of theoroi, that is, they were delegates who sought contact with the god (and not presbeutai, as was normal in interstate communications).99

The motive behind deification in Athens is known. It was hoped that by deifying the king, Alexander would be lenient in the Samos issue and resolve in Athens’s favor the dispute over the Athenian cleruchy on the island.100 Based on the statement by Hypereides, Habicht has argued that the Alexander and the Hephaestion cults in Athens must be seen as a single entity, and that they were introduced simultaneously.101 His argument runs as follows. By desiring a cult for Hephaestion in Athens, Alexander was also striving indirectly for his own deification. According to the Ammon oracle consulted by Alexander (in the spring of 323), Hephaestion, who had died in October 324,102 was to be revered as a hero. Even before that, Alexander had ordered that Hephaestion be revered in thechora barbaros and the army camp.103 Athens too had previously decided – in the winter of 324/3, before the oracle of Ammon spoke – that Hephaestion be revered.104 Hephaestion was also referred to generally as an “assistant deity,” as a theos paredros, in Diodorus and Lucian.105 A cult of Hephaestion in Athens was therefore based on a superordinate Alexander cult. The two cults can therefore be assumed to have coexisted as a single cult,106 whereby, according to Hypereides, Hephaestion as servant was accorded reverence as a hero.107 This joint cult is comparable to that of Achilles and Patroclus, who had a common tomb and were jointly revered by a cult108which had existed, allegedly, since 334, when Hephaestion and Alexander visited Ilium.109 This close association of Alexander and Hephaestion in a joint cult is also indirectly addressed in the Ephippus pamphlet, written shortly after Alexander’s death, because their divinity stood in sharp contrast to their mortality as humans and to the humiliating manner in which Alexander died (chronic alcoholism).110 Habicht believed additionally that the joint cult could also be identified in Alexandria, where statuettes for Alexander and Hephaestion were found.111 This would mean that the joint cult for Alexander and Hephaestion was established in early 323 in Athens, before the arrival in Babylon of the delegates who did not worship the king as a divinity before April 323 according to Habicht.112

Habicht thus took an emphatic position against the hypothesis that the Exiles’ Decree, already known when announced to the Greeks by Nicanor at the Olympic Games, was legally based on the deification of Alexander that had already been effected.113 However, there is not necessarily a temporal relationship between the two cults in the Hypereides fragment. Habicht actually retracted his hypothesis of a joint cult in 1970 (in the afterword to the second edition).114 He did not state the implications of his unsuccessful argument for the existence of a joint cult, though.

It was Ed. Meyer who had originally suspected that Alexander demanded deification by the cities of the Greek homeland in order to give a legitimate and lasting form to his “ruling position.”115 Habicht distances himself from this view and tends to believe instead that Alexander expressed such a wish in indirect form – by demanding that Hephaestion be revered as an assistant deity.116

Regulating the relationship between the Greek city-state and the ruler appears to have been a serious and increasing problem (pending since 334), or at least was considered as such by contemporaries. Given the need for protection on the part of the communities, and the overwhelming power of rulers like Alexander, it was necessary to regulate in which form the ruler could approach the formally free cities from his superordinated position, without damaging the inner structure and workings of the community.117 It has to be doubted that there was any systemizing will on the part of Alexander to create a superordinate hierarchical level, in the sense of a general deification. However, as the sources show, not only in the case of Alexander, but also in that of the Antigonids in 307, the acknowledgment of a divine ruler figure acting for the benefit of the city was essentially acceptable to Greek cities. The Seleucids under Antiochus III pursued this principle the most rigorously.118

In this case, commands from the ruler were like an oracle in nature. The Greeks had been familiar with such a superordinate, divine level of command since the archaic period.119 It was no coincidence that, since the days of Alexander, the emissaries of the cities who were sent out to receive the ruler’s instructions, were called theoroi.120 The ruler, who now took the place previously occupied by traditional protecting gods, was tolerable for a free Greek as long as he acted in the long term for the benefit of the communities.121 Abuse of his position was “conceptually” impossible, because the “new god” could give his instructions, which acquired the quality of an oracle, only when requested, and with the welfare of the inquiring city in mind. These instructions were “merely” suitable as fundamental decisions on essential issues, and were not to be obtained for day-to-day policy-making in a city. That the rulers of the oikumene had to keep the whole community in mind was necessarily to the benefit of the individual communities, since the ruler of the oikumene himself was not called into question.

This absolute ruler was theoretically conceived by Aristotle – with an eye to Alexander, of course – as an opposite form to tyranny. In the third and fourth book of his Politics, Aristotle termed this form of rule pambasileia.122 Such a ruler ![]()

![]() (1287a 8-9), but not in the negative sense of a tyranny, which Aristotle explicitly contrasts to such pambasileia as

(1287a 8-9), but not in the negative sense of a tyranny, which Aristotle explicitly contrasts to such pambasileia as ![]() (1295a 18). The tyrant rules without any duty of accountability

(1295a 18). The tyrant rules without any duty of accountability ![]()

![]() and merely for his own benefit

and merely for his own benefit ![]()

![]() . His rule therefore appears to be no longer tolerable for any free person (

. His rule therefore appears to be no longer tolerable for any free person (![]() ). In the documentary sources as well (Iasos, Amyzon, Teos), one finds the same concept of pambasileia – positively expressed of course – for Antiochus III over all men.

). In the documentary sources as well (Iasos, Amyzon, Teos), one finds the same concept of pambasileia – positively expressed of course – for Antiochus III over all men.

The charismatic king123 therefore acted purely for the benefit of the (Greek) communities, as euergetes, in the sense of fostering traditional political forms (usually democracy). It was therefore a topos that any royal directives that violated the constitution of the cities had to be invalid.124 For this reason, it was standard procedure that deification by the city had to be preceded by the ruler bestowing favors. This meant it was formally voluntary; in any case, the voluntary nature of deification was a desired objective and was purchased at a high “price” for the ruler. However, deification could also be demanded of the cities directly (by the king himself, but mostly through a royal functionary).125 In this form, it came close to the dynastic ruler cult,126 which was reserved, in formal legal terms, for the

dependent regions. However, since this is documented at a relatively late stage, the possibility must be conceded that the substance of the ruler cult in the cities (i.e., the “institutionalization” of the ruler’s dominance over a formally free city) became inflated to an increasingly apparent extent. Habicht himself admits, however, that the initiative for establishing the cults in the Greek mainland came originally from Alexander.127 And in every case in the time of the Successors of Alexander the introduction of the formally voluntary city cult was connected with a change in hegemony.

All endeavors to establish a more or less voluntarily practiced deification of Alexander in Athens and other cities in Greece were quashed by the Lamian War (323/2) after the death of Alexander and, following the victory of the central Macedonian government, were not reestablished because the government, distancing itself from Alexander, returned to forms of rule previously practiced under Philip.

In contrast, cults established for relatives of Alexander after his death are known: these include the cult of Philip III Arrhidaeus and Alexander IV on Samos, and the cult of Eurydice in Cassandreia.128 An agon for Philip III and Alexander IV on Samos was mentioned in the second half of 321.129 The festivities had been established not long before – following the expulsion of the Athenian cleruchy and after the return of the exiled Samians. Perdiccas had made this decision on behalf of the kings, although Polyperchon retracted it in 319 on behalf of the same. That probably meant the end of the festival.

The cult for Eurydice in Cassandreia is mentioned by Polyaenus (6.7.2). After the death of her son Ptolemy Ceraunus in 279, Eurydice had relinquished power of her own accord. After granting the city its freedom, she was pushed aside by Apollodorus, who intended to establish his own tyranny. He founded a festival for Eurydice and gave citizenship rights to the soldiers of the Macedonian garrison. He then used this garrison to establish a tyranny, which in the end was eliminated by Antigonus Gonatas. After the peace agreement between Gonatas and Antiochus in 278, Apollodorus’ tyranny became precarious. The cult therefore dates to between the years 279 and 278. The cult would actually be an indicator for the royal cult in the cities lacking any implications of dominance by a ruler,130 had it not been explicitly manipulated by Apollodorus and used to establish his own dominance.

1 E.g., Bosworth 1988a: 288, with n. 15.

2 Habicht 1956: 17–36.

3 Habicht 1956; 1970; Badian 1981; Bosworth 1988a: 278–90; Seibert 1994: 192–206; Gehrke 2003a: 157–8. On the abundant literature discussing the divinity of Alexander and the relationship between Alexander and the Greeks, see Ferguson 1912–13; Schnabel 1925; 1926; Stier 1939: 391–5; Balsdon 1950; Taeger 1957; Bosworth 1977; Rosen 1978; Fredricksmeyer 1979–80, 1981; Zahrnt 1996, 2003; Faraguna 2003; Nowotka 2003; Wiemer 2005: 163–4.

4 Seibert 1994: 143–4, 202–4.

5 This was recorded by Chares of Mytilene, the court chamberlain of Alexander on the march: Plu. Alex. 54.5–6; Arr. 4.12.3–5; FGrH 125 F14.

6 Discussed at length by Bosworth 1988a: 284–7, at 284. His conclusion that the ceremony aimed to prepare Alexander’s deification is based on those sources in which proskynesis was discussed at court, including Callisthenes’ speech against it: Plu. Alex. 54.3; Arr. 4.10.5; Curt. 8.5.9. The content, however, seems to be ahistorical. Macedonian opposition to the ceremony followed from their displeasure at being equated with Persian “barbarians.”

7 On the identification with Dionysus and Heracles, see Seibert 1994: 204–6.

8 Bosworth 1988a: 281–2.

9 Arr. 1.11.8. The visit was motivated by the mythological-historical obligation of Alexander (he also visited Achilles’ tomb): Str. 13.1.27 C594; Bringmann and von Steuben 1995, nos. 246–8. For an overview of Alexander and Achilles see Ameling 1988: 657–92.

10 Arr. 2.5.9.

11 In 327/6 he besieged the Aornus mountain, where Heracles, according to myth, had failed: Arr. 4.28.2, 30.4; Curt. 8.11.2.

12 Schepens 1989.

13 FGrH 126 F5; Bosworth 1988a: 287–8.

14 Lehmann 1971: 23ff.

15 FGrH 126 F3; see Bosworth 1988a: 287; Lauffer 1993: 186–7 n. 32.

16 Kienast 1988; for debate on the research see Seibert 1994: 116–25; Bosworth 1988a: 282–4. This oracle was highly rated by the Greeks (see Hdt 2.50–7).

17 Plu. Alex. 3.3.

18 There are also a wide range of motives for Alexander’s actions, including his urge (pothos) to surpass his mythological and genealogical models, Perseus and Heracles (Str. 17.1.43 = Callisthenes, FGrH 124 F14; Arr. 3.3.1–2).

19 Arr. 3.3.1–4.5. Aristobulus’ account differs from Ptolemy’s on the return route; see Lauffer 1993: 88–9. About the same time reports arrived in Memphis from the oracle of the Branchidae at Miletos and of the Sibyl in Erythrae. They confirmed Alexander as the son of Zeus.

20 D.S. 17.49–51.

21 FGrH 124 F14 = Str. 17.1.43 C814; Plu. Alex. 27.

22 To the Greek cities in Asia Minor Alexander presented himself as liberator, and he affirmed the indigenous traditions (e.g., Sardis: Bringmann and von Steuben 1995: no. 258; Arr. 1.17.3–4; in Caria, Ada, the widow of Mausolus whom Pixodarus had deposed, adopted Alexander (Arr. 1.23.7–8); see below on Halicarnassus); in Egypt, after being crowned pharaoh, Alexander worshiped the Apis bull in Memphis, unlike Cambyses who supposedly killed it (Arr. 3.1.4).

23 Bosworth 1988a: 283.

24 In the year 335, just before Alexander’s own campaign in Asia Minor, the war in Asia Minor under Parmenion (initiated by Philip) was in crisis, as the propaganda of revenge made little impression on the cities of Asia Minor.

25 Habicht 1956; see also afterword of 2nd edn. (1970); Laufer 1993: 181.

26 See Habicht 1956: 22–5 for the introduction of Alexander cults in Asia Minor between 334 and 331; the reasons Habicht elaborates for the establishment of the cults are treated skeptically by Badian 1981: 59–63, who argues for an introduction in the last four years of Alexander.

27 SIG3 278; I. Priene 3.4, 4.4, 6.4, 7.4. In Priene, the stephanophoroi became eponymoi magistrates in the year 334: I. Priene 2.4. In Miletos, Alexander became the stephanophoros eponymos in the same or the following year. From that time on thestephanophoroi were inscribed on stone: I. Milet 122 II, 81 with commentary; for the other date, see commentary of Herrmann 1997: 166. A decree in Colophon (Robert 1936: 158–68) honored Alexander’s actions of 334 as the beginning of a new era; see Meritt 1935: 361, 6–7.

28 Arr. 1.17.11, 3.2.4ff.; Curt. 4.8.11; Rhodes-Osborne, no. 83.

29 D.S. 17.24.1; Arr. 1.18.2.

30 Arr. 7.23.2.

31 Habicht 1956: 36; 1970: 252. The cult has to be separated from the dynasty cult which referred to Alexander. Habicht supposed that the death of Alexander preceded the establishment of the cult, because basileus was omitted in the title of the priest: Plaumann 1920: esp. 85; Jul. Val. 3.60;SEG ii. 849. In the other cities founded by Alexander no cult is known, although it is likely they existed. In these cases Alexander also established democracies.

32 Arr. 1.18.1–2 (when Alexander was in Ephesus). In order to block up the harbors for the Persian fleet, he started freeing the important cities along the south coast of Asia Minor (Arr. 1.24.5–6; 26.5–27.4; 2.5.5–9) as soon as he gained Halicarnassus in Caria (with the exception of Salmakis: D.S. 17.27.6).

33 OGIS 222, 24–5 (third century); Str. 14.644 (Augustan era); also Le Bas and Waddington 1870: 1540 (Erythrae, Augustan era; see also Robert 1929: 148).

34 Str. 14.644.

35 CIG 3615; Brückner 1902: 472, no. 79; 576; see also Frisch 1975: no. 122, with the alternative to equate the eponymos of the phyle to Paris.

36 Arr. 1.12.1ff.; Plu. Alex. 15; D.S. 17.17.3; Just. 11.5.12; Instinsky 1949: 54ff.; Zahrnt 1996: 129–47.

37 Str. 13.593.

38 Habicht 1956: 21.

39 The city still referred to this status in the time of Antiochus I: Welles, RC 15, 21ff.

40 Paus. 2.1.5; Plin. NH 5.116.

41 Callisthenes, FGrH 124 F14.

42 SIG3 1014, 111; date discussed by Robert 1933; Sokolowski 1946: 548; Engelmann and Merkelbach: no. 201, n. 78.

43 Habicht 1956: 19, 93–4.

44 Fontrier 1903: 232, no. 2.

45 IGR iv. 1543, with OGIS 3 n. 2.

46 Rostovtzeff 1935: 62, with OGIS 246, 12.

47 Paus. 7.5.1–2; Plin. NH 5.117; on the Alexandreia of the Ionian koinon see above.

48 SEG iv. 521.

49 Arr. 1.17.10–12; Bringmann and von Steuben 1995: no. 263.

50 Str. 14.1.22 C640–1; Bringmann and von Steuben 1995: no. 264.

51 Plin. HN 35.92; Cic. Verr. 4.135; Ael. VH 2.3; Plu. Alex. 4.3; Plu. Mor. 335a. Berve 2.53–4 dated this to the year 331.

52 Str. 14.1.22 C641; Alexander was one of the first rulers who guaranteed and extended the territory of an asylum (ibid.), in the case of the Artemision (which became common until the Roman period); but the Ephesians declined Alexander’s offer to meet all expenses for the temple, because he demanded credit for it in the dedicatory inscription (as it became common later on honoring the activities of euergetai: see above); this was contrary to the case of Priene.

53 Isocrates was the propagator of these ideas and connected them with Philip: Isoc. Ep. 3.5; see also Balsdon 1950. These ideas included the settlement of the uprooted masses of exiles of mainland Greece. Even in this respect Alexander quit the ground of his father’s policy with the Exiles’ Decree (see below).

54 Habicht 1956 interpreted this as a cult; but see now Habicht 1970: 245 for a different view. On the removal of Philip’s statue see Arr. 1.17.10–11.

55 Tod 191, ll. 1–2 and 43–4 = OGIS 8a. Rhodes-Osborne 83 argue against Heisserer 1980, who suggested that the plurality of the altars for Zeus Philippios could be explained by the fact that the tyrants ruled in the neighboring cities Antissa and Eresus and that altars were in both cities.

56 Arr. 1.17.10.

57 Berve ii. 251.

58 I. Priene 1 and 156 = OGIS 1 and SIG3 277 = Tod 185 and 184 = Rhodes-Osborne 86; Botermann 1994. For the dedication of the temple of Athena Polias see Bringmann and von Steuben 1995: no. 268.

59 In Xanthos, Lycia, dedications of Alexander are attested: SEG xxx. 1533.

60 Arr. 2.1.4.

61 SIG3 278 = I. Priene 2.

62 I. Priene 108, 75.

63 Botermann 1994. In Caria, Alexander respected the traditions by allowing himself to be adopted by the widow Ada (see above).

64 Isoc. 5.76, 114–15, where Heracles, the euergetes Hellados and ancestor of the Argeads, is the model for his actions.

65 Isoc. 5.120.

66 Habicht 1956: 18.

67 I. Magnesia 16.

68 Arr. 1.18.1. Tralles of Caria also sent an embassy (see above).

69 OGIS 3, with n. 2.

70 Habicht 1956: 143–4.

71 Segre 1941: 29–39, at 30, l. 14.

72 D.S. 20.84.3; Blinkenberg 1941: no. 197F, l. 5: after 156 BC.

73 Blinkenberg 1941: ii. 1, no. 233, ll. 8ff.

74 Habicht 1956: 26 n. 7.

75 IGR iv. 1116; Habicht 1956: n. 151.

76 Arr. 2.20.2; Curt. 4.5.9, 8.12; Just. 11.11.1; Plu. Alex. 32. Dedication of Alexander at Lindos: Blinkenberg 1941: ii. 1, no. 2 §38; Bringmann and von Steuben 1995: no. 194. Berve i. 247–8, also on the relationship between Rhodes and Alexander according to the novel of Alexander.

77 D.S. 20.81.3; Ps.-Call. 3.33.2 (p. 138 Kroll); Merkelbach 1954: 123–51. Pugliese Carratelli 1949: 154–71 argues that Alexander influenced the Rhodian constitution democratically and therefore became a second founder.

78 D.S. 18.8.1.

79 1958: 193–267, esp. 244–8.

80 Salviat 1958: 247.

81 Rhodes-Osborne 85. On the date see, e.g., Worthington 1990; Zahrnt 2003: 416.

82 SIG 3 283 = Rhodes-Osborne 84; cf. no. 87. No. 84 deals with the establishment of a democratic constitution. The king himself assumes the role of a diallaktes, as in Ephesus and Mytilene. This role introduced the cities to the idea of the euergetes ruler so common in the Hellenistic era, a role similar to that of a deity of an oracle (see below).

83 Arr. 2.5.7; Curt. 4.5.13–22; Worthington 2004a.

84 Rhodes-Osborne, no. 85, ll. 44–6. But the reading is uncertain (in OGIS ii. 46): see discussion in Rhodes-Osborne 428.

85 D. 1.5; on the circumstances by which Philip II took the city and violated the asylum, see D. 1.5, 20.63; cf. D.S. 16.8.2; D. 12.21, 23.

86 Aristid. Symachikos A (or. 38), vol. I 715D.

87 D.S. 16.3.3–4.1; Polyaen. 4.2.17.

88 D.S. 16.8.2.

89 Habicht 1956: 13; Badian 1981: 39–41.

90 D.S. 16.8.6.

91 Picard 1938: 334–5. During the marriage of Cleopatra, Philip’s statue was carried as the thirteenth god with the other Olympians.

92 SEG xlviii. 708, 835. It has been suggested that the building where was found a letter sent by Philippi’s envoys reporting a decision by Alexander concerning the city’s territory (c.330: see below) may have related to the cult of Philip II (SEG xxxviii. 658).

93 Rhet. 1. 221 Spengel-Hammer; see also the discussion in Schaefer 1887: iii. 32 n. 1.

94 Hyp. 6.21.

95 The later legend is that Alexander was worshiped as “Neos Dionysus” or as god additionally to the twelve traditional gods of Athens (see above about the identification with Dionysus).

96 Arr. 1.1.3; Paus. 1.9.4.

97 Balsdon 1950: 383. On attitudes regarding Alexander’s deification in Athens see Lycurgus in [Plu.] Mor. 842d and Demosthenes (Din. 1.94). On the wording of the (anachronistic) decision of Alexander’s deification in Sparta, see Ael. VH 2.19; cf. Plu. Mor.219e; Bosworth 1988a: 289. It is reasonable to suppose that the introduction of the cults in other cities of Greece was easier than in cities like Athens and Sparta which were hostile toward Alexander.

98 Lucian, Mort. dial. 13.2. For a possible cult-building for Alexander in Megalopolis see Paus. 8.32.1.

99 Arr. 7.23.2; about the term theoroi, see the honors of Athens for the Antigonids in 307: Plu. Demetr. 11. This Athenian way became a model for the manner of worship and in general for the rela¬tionship between democratic cities and rulers, who renounced the formal surrender of the city. Aristotle introduced this concept of treatment of a city by the pambasileus which was practiced by Alexander for the first time (see below; and on the euergetes king see above).

100 On the role of Demosthenes, who had already contacted Nicanor during the Olympic Games in August 324 immediately after the publication of the Exiles’ Decree, see Lehmann 2005: 207–15. His position during the negotiations was soon weakened because of his involvement in the Harpalus affair.

101 Habicht 1956: 29; 1970: 246ff. confirms that the cults for Alexander and Hephaestion in Athens were introduced simultaneously.

102 Habicht 1956: 33–6 argues that Harpalus arrived at Athens in September/October (Berve ii. 78 n. 2; contra Treves 1934: 515 – May/June 324). Demosthenes changed his mind during the Harpalus lawsuit which lasted six months (Din. 1.45) in the second half of the year 324 (Hyp. 1, col. 31), shortly before the condemnation in January 323.

103 Arr. 7.14.7; D.S. 17.115.6; Just. 12.12.12; cf. Arr. 7.14.9; D.S. 17.115.1; Lucian, Cal. 17.

104 Treves 1939.

105 D.S. 17.115.6; Lucian, Cal. 17.

106 Habicht 1956: 31.

107 The sources do not differentiate between hero and god: Arr. 7.14.7; Just. 12.12.12; Lucian, Cal. 17; Arr. 7.23.6; Plu. Alex. 2; D.S. 17.115.6.

108 Str. 13.596.

109 Arr. 1.12.1; 7.14.4, 16.8; Ael. VH 12.7.

110 FGrH 126; but the version that has Alexander succumb to the same fate as Heracles endured longer (OGIS 4.5; D.S. 18.56.2).

111 Gebauer 1938–9: 67–8.

112 Arr. 7.23.2.

113 Habicht 1956: 228–9. In 1970: 273–4 Habicht tried to confirm this by arguing that the Olympic Games were celebrated on August 4 (Sealey 1960). But Habicht’s main argument for the establishment of the cult of Alexander in the winter fails, because he has to concede (following Bickerman) that cults of Alexander and Hephaestion were not introduced simultaneously. On the Exiles’ Decree: Curt. 10.2.4–7; D.S. 17.119.1, 18.8.2–4; Just. 13.5.3–4; Din. 1.82–103; cf. SIG3 312, l. 11–15; Badian 1961: 41–3. The grateful exiles of Corinth erected a statue in Alexander’s honor in Olympia, where the king was equated with Zeus (Paus. 5.25.1).

114 Habicht 1970: 249–50. In Diodorus and Lucian the theos paredros was “nicht der beigestellte, sondern der Beistand leistende Gott” (according to Taeger in Habicht 1970: 250 n. 10).

115 Meyer 1910; 1924: 265–314. Meyer rated this ruling position as the basis for his command con¬cerning the exiles in August 324.

116 Habicht 1956: 225–9, 1970: 272–3; following him: Wiemer 2005: 163–5.

117 See, e.g., Ithyphallikos, Ath. 6.253b based on: Duris, FGrH 76 F13; cf. Demochares, FGrH 75 F2; Dreyer 1999: 115ff.

118 Dreyer 2007b: 300–20.

119 See the leading function of the Apollo of Delphi in the era of the Greek colonization, contrary to the argument of Habicht 1956: 227.

120 There is no irony in Arrian (7.23.2); cf. Habicht 1970: 247–8.

121 This role is attested for Alexander in the case of Tegea (SIG3 306 = Rhodes-Osborne 101, 324); Mitylene (OGIS 2 = Rhodes-Osborne 85); Chios (SIG3 283 = Tod 192 = Rhodes-Osborne 84). It shows the well-informed and extraordinary (deified) pretensions of Alexander, which may be regarded as preparation for his intervention in Philippi (about December 331; cf. Hatzopoulos 1987: 436–9, at 438ff. (no. 714); SEG xxxiv. 664; SEG xlviii. 835, perhaps in regard to the cult of Philip II; cf. SEG xxxviii. 658) and in the responsibilities of Antipater who was continuously quarreling with Olympias (Plu. Mor. 180d) and struggling in the war with Agis of Sparta.

122 In Pol. 1285b 36, the owner of the pambasileia is conceded the supreme decision; cf. Rhet. 1365b 37–1366a 2 and Hdt. 3.80.3; see also Pol. 1287a 8; in Pol. 1295a 18, the pambasileia is the positive counterpart of the third kind of kingship, the tyranny. This sort of kingship is not only negatively rated, but also as not Greek. The pambasileia, on the contrary, is honest, unselfish, tolerable for free men; one can see which considerations are connected with the cult of the worshiped king, who is under certain circumstances tolerable for free cities.

123 Gehrke 1982; see the definition in Weber 1922: ch. 3, §10.

124 Plu. Mor. 183e: ‘ ![]()

![]() .

.

125 In the areas in Asia Minor dominated originally by the Ptolemies: for Caria and Cilicia, see Dreyer 2002: 119–38, at n. 87; for Amyzon (passim), Kildara, Arsinoe, see Dreyer 2007b: 281 and Pfeiffer 2008: 33–46.

126 Contrary to Habicht 1956: 226–7. He argues that the city cult for living rulers had no ruling and hierarchic quality, because the city always had the initiative, and that this quality never existed under the successors of Alexander. On the connection of city cult of living rulers and dynasty cult, see Gauthier 1989: 73ff., who describes the development of the city cult for Laodice to the dynasty cult for Laodice; see also Dreyer 2007b: 239–59

127 Habicht 1956: 229. The kind of benefit by the ruler for the city can be seen in the cult epitheton of the worshiped ruler.

128 Habicht 1970: 252–5.

129 Habicht 1957: 156ff., no. 1.

130 Habicht 1970: 272.