15

The Official Portraiture of Alexander the Great

Catie Mihalopoulos

The Hellenistic era marks an important shift in postclassical Greek social, political, and artistic beliefs. The person most responsible for shaping and developing the political and religious ideals distinguishing this period was Alexander the Great. His political and military achievements established him as an icon for the Hellenistic world. He became a symbol of power, intelligence, beauty, and fortune.

Nothing is more reflective of these qualities than the numerous examples of Alexander’s portraits. An enormous variety of styles and types has been discovered throughout the Greco-Roman world. The surviving evidence of these works is scanty. It is, nevertheless, extremely important in understanding the construction of a new ideal in official portraiture. The sculpted image of Alexander had become much more than a representation of his physical appearance. His portraits were the direct reflection of a political and social order which he had established. The personal character revealed through his portraiture conveyed the increasing emphasis on the individual and his tyche (fate). Furthermore, the production of these images can also be viewed as a prominent vehicle for political propaganda and a way of expressing the monarch’s achievements and power. The extensive variety of Alexander’s representations made him more a paradigm than a person. The official image of Alexander, therefore, is an essential element that distinguishes the art of the Hellenistic period, which set a powerful standard for future tradition and subsequent royal and private portraiture.

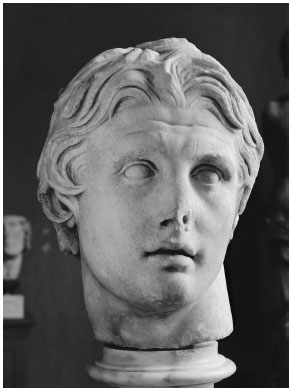

Son of Philip II and Olympias, Alexander stands in the first rank of the world’s great military commanders. Identified by his massive leonine hair, idealized face, and upturned eyes, Alexander was the first Greek ruler who understood and exploited the propagandistic powers of official portraiture. One of the earliest portraits of Alexander representing him as a youth, dating from 340–330, is found today in the Acropolis Museum in Athens (see fig. 1.1).1 This portrait shows Alexander as a dreamy-looking youth. His eyes are deep set, his eyebrows are strong, and he has a rounded face and fleshy lips. In sharp contrast, his hair locks, which are summarily shaped into a massive mane, produce a strong chiaroscuro. Here, this portrait conflates Attic ideology, legend, and history. Alexander is clean-shaven and is depicted as the Homeric hero Achilles.2 A second example of the youthful Alexander, said to have originated from Megara and now at the J. Paul Getty Museum in Malibu, dates to about 325–320 (fig. 15.1).3 This portrait shows Alexander with his head turned slightly to the left. He has strong eyebrows, a prominent nose, and a rounded jaw; his mouth is fleshy. There is juxtaposition between the modeled face and the chiaroscuro created by his leonine hair. The Acropolis portrait and the Getty Alexander share similarities in the youthful expression of the monarch who appears to be rendered as a variation of images that connect him with the Homeric hero Achilles.4 Pausanias tells us that in 338 Philip II commissioned a gallery of portraits to be placed in the Sanctuary of Zeus at Olympia.5 These statues were made of gold and ivory, thus, chryselephantine, and one of them depicted Alexander at age 16. The portraits commissioned by Philip are said to have been created by the artist Leochares, who was famous for his sculptures of the gods. According to this account, Alexander’s image was projected even before he became king of Macedonia.6

Figure 15.1 The Getty Alexander, c.325–320BC . J. Paul Getty Museum, Malibu. Acc. no. 73.AA 27. Photo: The J. Paul Getty Museum.

Alexander spent his life on the battlefield with his troops, while Macedonia was governed in his name by Antipater. He was rarely in the vicinity of his subjects, and when the inhabitants of a state are not often reminded that there is a ruler in charge it can be a difficult task to retain loyal subjects. The absence of a powerful political icon increases the possibility of rebellion, especially when it is an empire that has recently been conquered as had Persia. Perpetuating his image in his place of birth at Aegae (modern Vergina) in Macedonia would not have been much of a problem since his victories brought fame and glory to the Macedonians. The eastern peoples, however, whom he had defeated and absorbed into his empire, would not have been so pleased or concerned to hear news of his continuing conquests. The need for an official powerful image became particularly important toward the end of his life, especially after his withdrawal from India.7 In order to maintain his unconquered image in the minds of his subjects, he needed some way to remind them of his past achievements. The implementation of a persuasive portrait iconography in the form of statues, paintings, and subsequently coins conveying the existence of an omnipotent leader became a very effective iconic sign.8 These visual signifiers reminded the empire that there was in fact a powerful monarch present who, if disobeyed, would punish all who broke the law. It was at this moment that the art of propaganda was crystallizing at a rapid pace.9 To paraphrase Stewart, Alexander’s portraiture was a constructed new ideal adhering to the rules of the new Hellenistic social ideology. The portraits gave him legitimacy and they were encoded so that they could be interpreted by their audience as imagery of the charismatic ruler. In other words, Alexander’s portraits were intended for political and moral interpretation and they became “epideictic visual rhetoric.”10

The official portraiture of Alexander demonstrated a new ideal: the amalgamation of individual characteristics, associated with adopted elements from the Near East and Egypt. Thus, a frequent modus operandi involves the ruler as if he were a divinity related with local religious traditions such as the concept of leader of the people he had just conquered. From early in his career, as king (basileus) of Macedonia, hegemon of the Greeks, successor to the Achaemenids, and finally son of Zeus, Alexander ruled by virtue of what has been called a quasi-constitutional position.11 Surrounded by Macedonian aristocrats, his “Companions,” Alexander shaped a new aristocracy to which his eastern subjects would submit without much struggle. Hence, the personality and energy of the new monarch became determining factors in his subsequent reception and perception of his newly conquered subjects in Asia as well as in Egypt. In pharaonic Egypt the king was a divinity. This belief would later lead to the Ptolemaic ruler cult, but was shaped itself by Alexander’s own connection with Egyptian divinities. This is seen in the image of Alexander before Amon-Ra from the so-called Shrine of the Bark at the Temple of Luxor (see fig. 12.1). In winter 332/1 Alexander also took a long march to the desert oracle of Amun at the oasis of Siwah. His own propaganda later announced that the oracle recognized him as the son of Amun, the equivalent to the Greek god Zeus, thus bestowing on Alexander the divine right to rule as Egyptian pharaoh.12

The portraiture of Alexander is often divided by scholars into various types. These types were consequently established from images that perpetuated the Hellenistic ruler cult.13 A variety of these images concentrated on depictions of the monarch as Heracles, Helios, the son of Zeus, and may be considered heroic portraits. Other images, dubbed the equestrian type, show Alexander on horseback as on the so-called Alexander Sarcophagus from the royal necropolis at Sidon (fig. 2.3) and in the Alexander Mosaic from the House of the Faun, Italy (fig. 2.2).14

The majority of the so-called royal-derivative portraits were primarily significant in the intentional projection of the idiosyncratic qualities of the ethos, pathos, and the arête of the individual. Hence, these ruler-type portraits represented visual political propaganda and were intended to perpetuate the image, prestige, tyche, and the charisma of Alexander. That is to say, these various images functioned in antiquity like popular culture images transmitted today on television and in printed political advertisements. The portraiture of the ruler was an effective and persuasive means of projecting the qualities of the monarch. The artist credited with the creation of this type of ruler portraiture was Lysippus of Sicyon.15 It is said that Lysippus pioneered a new style in sculpture during the late fourth century, and critics said of his work that “older sculptors made men as they are; he made them as they appear to be.”16

In addition to individual portraits of Alexander, Lysippus created victory monuments that commemorated the king’s battles and subsequent conquests. The most important of these was that commemorating the battle of Granicus.17 According to Pollitt, the Granicus Monument was transported to Rome by Q. Caecilius Metellus in 146 and no longer survives.18 The monument commemorating the battle was originally located at Dion, in the great sanctuary of the Olympian Zeus just below Mt. Olympus. According to tradition, Alexander started his campaign following official ceremonial sacrifices. The monument is said to have been a composition depicting the twenty-five Companions who fell during the battle. One of these equestrian statues may have inspired an equestrian statue of Alexander, Alexander on Horseback, that no longer survives. Echoes of this now lost masterpiece may be found in the Equestrian Statuette of Herculaneum at the Museo Archeologico Nazionale, Naples (fig. 2.1).

Lysippan Portraits of Alexander the Great

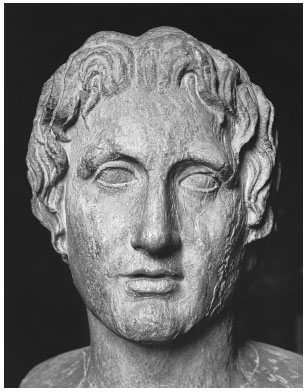

According to Plutarch “it is the statues of Lysippus which best convey Alexander’s physical appearance. . . For it was the artist who captured exactly those distinctive features which many of Alexander’s successors and friends later tried to imitate, namely the poise of the neck turned slightly to the left and the melting glance of the eyes.”19 Plutarch continues that “Alexander decreed that only Lysippus should be allowed to make his portrait. For only Lysippus, it appears, brought out his real character in the bronze and he also gave form to the essential excellence of his character.”20

Lysippus’ achievement in creating Alexander’s portrait is clearly revealed in Plutarch’s language. For example, the Lysippan images conveyed first and foremost Alexander’s arête as well as his ethos and pathos. According to tradition, Lysippus incorporated Alexander’s natural tilt of the neck, a physical peculiarity that caused his head to have a slightly upward angle. No original Lysippan portrait of Alexander survives. Plutarch’s artistic vocabulary, however, can be detected in many copies of Alexander, such as the turn of the neck to the left, the upward glance of his eyes and his particular anastolè hairstyle that were copied on a number of occasions during and after Alexander’s time.21

Figure 15.2 Head of Alexander the Great. Copy of original by Lysippus. Capitoline Museum, Rome. Photo: Alinari/Art Resource, New York.

Characteristics associated with Alexander’s portraits are also reflected in royal Hellenistic processions, and in the ruler cult of Hellenistic monarchs and subsequent Roman leaders. One of the best-known examples of such sculpture is a marble head generally identified as Alexander that dates to 180, the Alexander from Pergamum, at the Istanbul Archaeological Museum (fig. 15.3).22 This portrait appears to convey the dramatic artistic elements that have been attributed to Lysippus. Small nuances, however, such as the rounded eyes, the modeled face, and the deeply drilled hair locks highly suggest a local Pergamene style.23 A marble portrait of Alexander discovered in the modern city Gianitsa (Macedonia), now now in the local museum at Pella, is perhaps a truer to life image of Alexander (fig. 15.4).24 This particular portrait dates from c.200–150, the era of the Macedonian kings Philip V and Perseus.25 There is a lack of dramatic exaggeration as well as a much softer treatment in the creation of the eyes. Such artistic elements can be directly connected with sculpture that dates from the fourth century, that is, the late Classical period. Therefore, the Gianitsa Alexander may indeed be the closest example linked to a Lysippan prototype.

Figure 15.3 Alexander from Pergamum, c. third centuryBC . Archaeological Museum, Istanbul. Photo: Erich Lessing/Art Resource, New York.

Alexander is also represented in a historical or quasi-historical context in the so-called Alexander Sarcophagus from the royal necropolis at Sidon, now in the

Figure 15.4 The Pella Alexander, from Gianitsa, c. 200–150BC . Pella Museum, Pella. Sculpture inventory no. TA 15. Photo: Archaeological Receipts Fund (TAP Service).

Archaeological Museum in Istanbul (figs. 2.3,2.4,2.5) depicting a battle scene, possibly that at Issus.26 The sarcophagus presents us with an image of Alexander created not long after his death. On the sarcophagus, Alexander is shown wearing a lion’s head helmet. The sarcophagus may be connected to Abdalonymus who was the last king of the native Sidonian dynasty, and whom Alexander elevated to power.27 The work is generally referred to as the “Alexander Sarcophagus” and it shows one of the most striking representations of battle that can be connected to Alexander. Traces of color are still evident on the sarcophagus. Two of its four sides show battles between the Macedonians and/or Greeks and the Persians. These images are found on one of the long and one of the short sides of the sarcophagus. The other two corresponding sides show hunting scenes. These reliefs are significant not only for their stylistic quality but also for their subject matter. The elaborate and at times rather complex compositions imply extensive knowledge of pictorial representations as well as exceptional artistic expertise.28 Additionally, the lion- helmeted horseman may be an elaborate representation of young horsemen found on Attic stelai that date from the late fourth century, for example, the Funerary Stele of Dexileus (c.390) at the Kerameikos Museum in Athens.29 Furthermore, the hunting friezes can be a vivid documentation of the political importance attributed to the hunting of lions and the subsequent repetitive motifs of the hunt seen in Hellenistic art. The long side of the sarcophagus, showing a battle scene distinctively portraying a lion-helmeted horseman, associates Alexander with Heracles.30 The figure of the lion-helmeted horseman may be considered a heroic portrait of Alexander portrayed as the fierce warrior, clearly conscious of his ability to exercise his control and power. Moreover, the symbolic signifier of the lion’s head may also imply Alexander’s divine-like qualities.

The facial characteristics of Alexander appear to be those described by Plutarch; they are also similar to those of the herm of Alexander, the so-called Azara Herm, found in Tivoli and now at the Louvre.31 A Greco-Roman copy after a fourth- century original statue believed to have been modeled after a close representation of Alexander (fig. 15.5). Inscribed AΣEΞANΔPOΣ ΦIΣIΠΠOY MAK[EΔΣN] (Alexander the Macedonian son of Philip), its subject is clearly identified.32 Though the Azara Herm is much worn, with some restorations and in poor condition, aspects of this portrait of Alexander surely go back to a Lysippan prototype as seen in the characteristic anastole hairstyle. This signature style would reappear later in the portrait of the Roman general and politician Pompey the Great, as seen in the example now at the Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek, Copenhagen (fig. 14.1).33

Finally, many scholars agree that the image of Alexander on the Alexander Sarcophagus reflects an amalgamation of the ruler portrait that was created by Lysippus and Apelles. Equestrian-type statues were widely copied throughout history. Though Alexander was not the first person depicted on horseback, later examples of equestrian portraits were perhaps styled after these Alexander prototypes. Examples of these include the Roman emperor Marcus Aurelius, the Byzantine emperor Justinian, and the medieval Frankish king Charlemagne, the emperor who restored the idea of Rome in his celebrated coronation on Christmas Day 800. A much later example is David’s famous painting of Napoleon crossing the Alps (Bonaparte, Calm on a Fiery Steed, Crossing the Alps , 1801).34

Figure 15.5 Alexander the Great, so-called “Alexander Azara.” First-centuryBC copy of original bust ( c. 320BC ) by Leochares. Louvre, Paris. Photo: Erich Lessing/Art Resource, New York.

One of the best-known works of art discovered at Pella is the mosaic that shows a stag hunt, signed by Gnosis, dated to c. 300 (fig. 15.6).35 This mosaic depicts a hunt, a popular theme in works of art associated with the Macedonian court. Royal hunting scenes have a long tradition in the Near East and Egypt and were popularized in the west by Alexander following his conquest of Persia.36 Some have seen in this mosaic Alexander and his companion Hephaestion.37 The mosaic shows two armed and nude men hunting a stag with a dog. The focus of the composition is on the stag under attack by the dog. The artist has brought drama and excitement to the work as the stag is shown bleeding from the attacking dog. While the two hunters are positioned symmetrically, the stag and the dog are placed in what is defined as a pyramidal composition. This particular artistic arrangement was later favored by Italian Renaissance artists such as Raphael in his Madonna del Cardellino ,38 as well as in Leonardo da Vinci’s Virgin of the Rocks.39

Figure 15.6 The Stag Hunt, Gnosis, c.300BC . Pella Museum, Pella. Photo: Archaeological Receipts Fund (TAP Service).

Gnosis was technically proficient in the artistic conventions employed by his late Classical contemporaries. One may recall the Abduction of Persephone by Hades in the Tomb of Persephone at Vergina dated c. 340.40 In the abduction scene the anonymous artist has made clear that what was to become Hellenistic art comprehends fully the idea of the modern concept di sotto in sù, first used by Mantegna on the ceiling of the Camera degli Sposi in 1474 in Mantua.41

The Gnosis mosaic shares artistic essentials that are analogous to those found on the Hades and Persephone wall painting. In addition, one may argue that Gnosis understood the shared artistic vocabulary that was to be developed and eventually practiced by artists throughout the Hellenistic world. There is an element of the koine, which is highly prevalent during the Hellenistic era. These works of art share many commonly understood constructs that distinguish the art of the Hellenistic era from other periods. These constructs relate to the ways in which artists observed nature and the societal ideals that were embedded into the Hellenistic populace, such as pothos, ponos, pathos, all of which in turn relate to the theatricality of the epoch, or to the spreading stylistic advantages in individual portraiture.

Figure 15.7 Pseudo-athlete from Delos. National Archaeological Museum, Athens. Photo: courtesy of John Pollini.

It is during the Hellenistic era, for example, that we find the fully developed idea of the human condition: it can be a depiction of a fortunate individual, such as the Pseudo-Athlete from Delos (fig. 15.7),42 or an individual depicted in tragic circumstances and shows his distress and fear, as in theLaocöon. M. Robertson argues that what characterizes Hellenistic art is a combination of new emphases as well as continuity: it can be found in the so-called philosopher portraits, in the erotic representations of divinities and humans alike, as well as in the psychological portraits of the period.43 The Gnosis mosaic appears to embrace several elements that can be distinguished as Hellenistic. For example, the movement and torsion seen in the representation of the two young men is mirrored in the stag and the dog in the middle of the composition.

Additionally, Gnosis applies a subtle gradation of shade to project the illusion that the figures have a rounded and solid form. The dark background of the composition sets the stage for illuminating the figures, as well as their presence and domination within it. Both hunters are shown wearing achlamys,44 which billows in the wind, suggesting rapid movement. There is an obvious counterbalance in the representation of their weapons, which are placed on a diagonal, as well as in an opposing but symmetrical manner. The figure on the right holds a sword while that on the left holds an ax. The legs of the two hunters are shown tense and they repeat the same counterbalance to the right and the left of the composition. An interesting signifier is included in this otherwise standard hunting scene: the hat in the upper right of the composition. This hat is a petasos, symbolic of travelers.45 If one were to take the right figure as Alexander, then the petasos may imply that the youth was not at Pella, because the monarch was away from Macedonia, a traveler in his newly conquered empire. Pollitt notes that the mosaic may have decorated the royal residence at Pella or simply the home of important Macedonian noble: it may have been at the house of Cassander, who ruled c.316–297, or perhaps of Antigonus Gonatas, who ruled 272–239.46 Moreno gives several reasons for his identification of the two youths. According to him, in Macedonia the petasos was a hat emblematic of royal rank and so should depict Alexander. The youth on the left of the composition is armed with a double ax, the weapon used by Hephaestus, the divine namesake of Hephaestion.47

An exceptional work of art, the Alexander Mosaic from the House of the Faun in Pompeii is thought by some to depict the battle at Issus (fig. 2.2). Moreno, however, asserts that the scene in fact commemorates the subsequent rout of the Persians at Gaugamela, near Nineveh in Iraq today,48 as suggested by the accounts of Ptolemy and Aristobulus of Cassandreia.49 The mosaic is believed by some to be a copy of a monumental Greek original painting by Philoxenus of Eretria (possibly Apelles).50 According to Moreno, the Alexander Mosaic was augmented during antiquity and was restored at the time it was inserted into the floor of an exedra in the House of the Faun, the residence of the Satrii family.51

The tesserated mosaic was quite influential when it was discovered in Italy in 1831.52

This is revealed in Goethe’s contemporary description that “the present and the future will not succeed in commenting correctly on this artistic marvel, and we must always return, after having studied and explained it, to simple, pure wonder.”53 At first glance the composition appears to be as chaotic as the spears of the warriors that form several diagonals in the background, especially those created by the Macedonian sarissai. To the left of the composition is a lifeless tree, placed off-center behind Alexander and his men. Greeks associated death with dead trees and their subsequent inclusion in the composition conveys an omen of death.54 A different interpretation about the inclusion of the dead tree, and one that agrees partially with Moreno’s, is that made by F. Zevi, who maintains that the dead tree recalls Arabic sources that refer to Gaugamela as the “Battle of the Desiccated Tree.” According to this interpretation, these sources, which date after Hellenistic times, claim that Alexander lost his helmet at Gaugamela. This piece of information may point to the location of the battle, since Alexander in this mosaic is shown bareheaded.55 In this work, Alexander is depicted charging toward Darius and impaling a Persian warrior trying to protect his king. On the right side of the composition, artistic knowledge and understanding of perspective and foreshortening is clearly demonstrated. The extreme foreshortening here showing a horse from the rear does not appear again until the Renaissance, as seen, for example, in Paolo Uccello’s The Battle of San Romano(c. 1445) at the National Gallery, London.56

The scene of the Alexander Mosaic offers a historical account of Alexander’s military success and the creation of his empire. It illustrates his heroism and bravery in battle, his arête, a Greek ideal, and exudes pathos, a Hellenistic trend in the visual tradition. Darius and his men, on the other hand, express fear and anguish which is clearly visible in their faces. Darius dramatically turns back, gazing at Alexander who slays one of his soldiers. In addition, Darius is shown dressed in Persian attire (as understood by late fourth-century Greek artists), which includes leggings, or pants.57In previous representations of battles, such as Amazonomachies (battles between the Greeks and the Amazons), which intend to illustrate the “other,” Amazons are dressed in leggings. This eastern form of dress often signified the effeminacy and the inadequacy of the opponent, and it was intentionally incorporated to show the “other” as being uncivilized and disruptive of the civilized Greek cosmos. Amazonomachy was part of the common artistic repertoire employed by Greek artists. This visual signifier was commonly located on the architectural decorations of temples such as the Temple of Zeus at Olympia, the Parthenon on the Athenian Acropolis, and in the interior frieze of the Temple of Apollo Epicurius at Bassae.

Images of Alexander by Apelles

A different form of portraiture associated with Alexander is the Zeus Keraunaios .58Variations of this type appear to derive from a famous painting by Apelles, the court painter of Alexander, showing Alexander seated and holding a thunderbolt in his right raised hand. A painting in the House of the Vettii at Pompeii may be a copy of this lost painting.59 The young man is shown with his head turned slightly to the left, and with a detailed coiffure of the anastole hairstyle. Additionally, the lower part of the body is covered by a himation and the figure’s feet rest on a small stool. Throughout the ancient world, an individual seated on a klismos with the feet on a stool suggested a person of high status. Additionally, the himation itself suggests a subject of either divine or at very least demigod status.

According to Pliny, it was Apelles who created the image of Alexander appearing as Zeus Keraunophoros.60 The artist is said to have created such a painting of Alexander that was placed at the great sanctuary in the Temple of Artemis at Ephesus.61Aelian, writing in the third centuryAD , reports that an image of Alexander was to be seen in this famous and important temple.62 If Aelian’s account is accurate, then the Temple of Artemis would have been the perfect location to display an image of the deceased young monarch. Pliny recounts that two images of Alexander by Apelles were also exhibited in the Forum of Augustus.63

A number of images of Alexander portray him with his head twisted to one side, face uplifted, and with expressive facial features. A good example of this emotionally charged image or Pathosbild is exemplified in the Pergamene head, previously discussed (fig. 15.3). A more idealized version of this pathos image is a portrait of Alexander as Helios at the Capitoline Museum in Rome, dating from about the second century (fig. 15.8). This image was perhaps based on a Hellenistic prototype and some scholars regard it as a portrait of Helios and not Alexander as Helios.64The supposed portrait of Alexander as Helios combines soft modeling of the face and a more flamboyant coiffure of leonine locks. The head is dramatically twisted to the left, thus creating a forceful movement that is further exaggerated by the chiaroscuro created by his full mane of hair. The curls of the hair are fluid, one thick strand cascading on top of the other, generating a waterfall type of movement that frames the highly polished face. This adaptation may exaggerate the features of some Lysippan prototype and introduces elements of the so-called Hellenistic Baroque style of c. 200–100.65Additionally the portrait is most likely indicative of the eclectic taste of the time, as the smooth surfaces and the hard lines are created in the neoclassical tradition of the time.66

Figure 15.8 Alexander Helios. Hellenistic bust. Capitoline Museum, Rome. Photo: Alinari/ Art Resource, New York.

Alexander’s divine-like images embody serenity, exemplifying the ruler as the son of Zeus. This style, expressed in the divine images of the monarch deriving from Apellan prototypes, is intended to perpetuate the transcended human limitations of the otherwise mortal ruler. Emotionally charged images, on the other hand, as seen in the Lysippan prototypes and those descending from them, are associated with the heroism of figures from the Greek past and now Alexander.

Figure 15.9 Neisos Gem. Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg.

Varia and Concluding Remarks

Gem-cutters were extremely important in the perpetuation of the heroic images of leaders from Alexander on. According to Pliny, Pyrgoteles was the gem engraver of Alexander’s court.67 An example of Greek glyptic art representing Alexander is the Neisos Gem, probably dating from the second century, and inscribed NEIΣOY by the artist, at the Hermitage (fig. 15.9).68 This private work of art is made of carnelian and represents Alexander holding a thunderbolt in his left hand and a sheathed sword in his right hand. The figure appears to be a variant of the Alexander with lance type attributed to Lysippus.69 Although the ancient sources do not give an extensive description about this type, a number of scholars have written about it. It appears the Alexander with a lance type was created by Lysippus in response to the painting by Apelles showing Alexander with a thunderbolt. There are a number of replicas of Alexander with a lance that survive.70 The Neisos Gem shows Alexander’s forearm covered by an aegis, his right hand resting on a shield. To his right stands the eagle of Zeus. This specific representation of Alexander seems to incorporate a Zeus-like image, which informed a number of other types produced in later times. The fusion of heroic and godlike types may be indicative of later stages in Alexander’s life when his divinity was officially worshiped. Gems with such images of Alexander appear to reflect public works of art and perpetuate his memory in the private sphere.

Privately commissioned gems with images of Alexander may also have served as prototypes in the production of coins.71 The multitude of artistic representations, including the production of coins, that were created during and after the lifetime of Alexander, aided in the creation and subsequent perpetuation of the memory of Alexander and then later of the Diadochi, as well as subsequent Roman leaders.

When considering the real changes that were brought about by the appearance of Alexander in the political landscape of the ancient Greek world and his conquered territories, we must ask the question: what do we mean by Hellenistic? When these changes are considered, we are led to conclude that Alexander was the catalyst that caused what was Hellenic, or Greek, to be transformed into Hellenistic koiné. In a seminal chapter in Peter Green’s Hellenistic History and Culture, M. Robertson asks “What is Hellenistic about Hellenistic Art?” Robertson discusses the multivalent nature of Hellenistic art and Hellenistic ideals as viewed by scholars and the general public. Furthermore, he asks, what is not Classical (Greek) in Hellenistic art? Robertson is unable to decide the precise moment that Hellenistic style came into being. It appears, however, that Alexander’s ascension to the throne represents an important moment in the creation of Hellenistic ideology. What used to be the individual as part of the collective, that is the demos, was completely altered by individualism and self-projection under the leadership of a monarch. To quote Robertson: “in the changed world of the Hellenistic kingdoms, and directly influenced by the change, philosophical skepticism becomes more cogent. . . Gods are present for all to see in the mortal kings, while the traditional gods become much more dubious entities, and, even if they exist, of much less significance than a universally recognized and overriding power of fortune.”72

J. J. Pollitt, on the other hand, has shown that there are five different elements that distinguish Hellenistic art from other periods: (1) an obsession with one’s fortune; (2) the theatrical mentality of the people; (3) individualism; (4) a cosmopolitan outlook; (5) a scholarly mentality. Pollitt’s discussion about these five particular characteristics shows that “they are interdependent and together constitute something like a Hellenistic Zeitgeist .”73

In conclusion, the artistic development which occurred during and after the time of Alexander shaped a new ideal in the material culture of the Greek mainland and the Mediterranean world. The construction of individual objects demonstrates a mutual understanding of what has been described as koiné. This intellectual shift was the result of a number of factors, including those described by Pollitt. In several instances one can detect a strong sense of individualization and idealization of a deified mortal in portraiture, in keeping with a new interest in naturalism. In addition, the inclination for dramatic subject matter, as well as the fate of mortals takes center-stage in the new world of Hellenistic theater and theatricality. Alexander’s new world is converted into an all-inclusive stage in which a chosen leader becomes the protagonist. In this climate, there was a proliferation of war monuments that perpetuated the virtues of the victor, as seen in the Nike of Samothrace, c.200.74Furthermore, artistic creations are paid for and dictated by private patrons, for example, the Pseudo-Athlete from Delos (fig. 15.7).75 Subsequently, Alexander’s new world order serves as the basis of the Greco-Roman tradition which was to be reborn and transformed from the Renaissance onward.

1 Museum inv. no. 1331. Found in 1886 near the Erechtheion on the Athenian Acropolis, this portrait is made of Pentelic marble (H: 0.35 m). See Pandermalis 2004: 18, no. 1; Harrison 2001; Stewart 1993: 106–13; Brouskari 1974: 184. I would like to thank Mark Rose, Executive Editor,Archaeology Magazine, for his generous gift of the Onassis Foundation Catalogue, Alexander the Great. Treasures from an Epic Era of Hellenism (2004).

2 For an extensive discussion on Alexander as the new Achilles see Stewart 1993: 78–86.

3 Museum inv. no. 73.AA.27. This particular work has undergone some restoration, perhaps during antiquity; however, some scholars regard the work as a fake. Stewart 1993: 52–3 gives a list of portraits commissioned during and after Alexander’s time. These include: (1) Alexander, the Granikos Group by Lysippus after 334; (2) Alexander with the thunderbolt by Apelles, dedicated at Ephesus after 334; (3) the reliefs in the Shrine of Amun at Luxor, c.331–323; (4) the equestrian statue of Alexander as the founder(ktistes) of the city of Alexandria, c.331; (5) statues on the battlefield of the Hydaspes, c.326; (6) a failed proposal to carve Mt. Athos into a portrait of Alexander; (7) several bronzes of Alexander (the lance type) by Lysippus; (8) several paintings by Apelles; (9) several gems by Pyrgoteles. Commissioned by the court: (1) Alexander and Darius in battle, painted by Philoxenus for Cassander, c.306?; (2) Alexander on satrapal coinage of Memphis. Cities also commissioned portraits of Alexander: e.g., (1) Alexander and Philip, Athens, c.338; (2) the Acropolis Alexander; (3) the proposed Alexander as Invisible God, c.324–323; (4) some cult statues for east Greek cities, c.323; (5) a statue at Larissa; (6) coins of Leucas and Naucratis. Individual commissions: e.g., (1) battle paintings by Aristides; (2) battle paintings for southern Italian vessels; (3) a painting of the marriage of Alexander to Roxane by Aetion, c .324.

4 Stewart 1993: nos. 5 and 16.

5 Paus. 5.20.9–10.

6 Pandermalis 2004: 15.

7 On Alexander in India see ch. 2 above.

8 Eco 1976: 207. On interpretations of Eco’s theory of semiotics regarding this topic, see Stewart 1993: 67.

9 There were numerous images of Philip II and Olympias circulating throughout Macedonia, in addition to those now preserved by the finds of Manolis Andronikos at Vergina. See Andronikos 1992.

10 Stewart 1993: 69; my emphasis.

11 See Tarn. See also Pollitt 1986: 318, app. 2. It is likely that Alexander requested that the Greek cities honor him as a god. See Ael. VH 2.19; Hyp. 5, col. 31; Arr. 7.23.2. See also Nock 1928.

12 Callisthenes ap.Str. 17.1.43, 40; Hornblower and Spawforth 27–30; OCD3. See also Bell 1985; el- Abdel el-Raqiz 1984; Stewart 1993: no. 53.

13 Ferguson 1928: 13–22; Nock 1928; Heuss 1937; Wilcken 1938: 298–321; Cerfaux and Tondriau 1957; Taeger 1957; Ritter 1965.

14 Alexander sarcophagus, Istanbul Archaeological Museum, inv. no. 370; Alexander Mosaic, Naples, Museo Nazionale, inv. no. 10020.

15 According to ancient sources, Alexander was so pleased with the images Lysippus created that he appointed him court sculptor. See Plin. HN 7.125; Plu. Alex. 4.1; Palagia and Pollitt 1996: 132. For other sources see also Johnson 1927: 301–6; Balsdon 1950; Sjöqvist 1966: 9–10; Badian 1981.

16 Palagia and Pollitt 1996: 132; see also Johnson 1927; Chamay and Maier 1987.

17 Gardner 1910: 227; Hammond 1980: 73–88.

18 Pollitt 1986: 43.

19 Plu. Alex. 4.1–7, c. 110AD . See also Stewart 1993: 344.

20 Plu. Alex. 4.1–7.

21 The anastolé hairstyle refers to the wave-like pattern of hair locks formed above the center of the forehead. For styles in Hellenistic sculpture see Ridgway 1990.

22 Museum inv. no. 1138 (cat. 538).

23 The Pergamene style is associated with the Hellenistic kings at Pergamum and Halicarnassus in Asia Minor. This artistic development showed the human in full motion, rounded and at times in the round, with rigorous facial characteristics as well as strong chiaroscuro. In addition, the images demonstrated strong emotions and elements of theater. See also Radt 1981; Pollitt 1986; Ridgway 1990.

24 Museum inv. no. TA 15. H: 30 cm.

25 Stewart 1993: xxv, no. 97 dates this portrait to c.300–270.

26 Museum inv. no. 370. L: 3.2 m; W 1.7 m. See Stewart 1993: 294–5, figs. 101–6, with further bibliography. The sarcophagus was perhaps that of Abdalonymus of Sidon. Arr. 2.15.6 reports that, when Alexander reached Sidon, the Sidonians opened their gates and invited him inside “out of their hatred for the Persians and King Darius.” Alexander made Abdalonymus king of Sidon after the battle at Issus in 333. See Winter 1912; Schefold and Seidel 1968; Koch 1975; Hammond 1980; and the next note.

27 Stewart 1993: 294; but see now Heckel 2006 who argues that the sarcophagus is that of Mazaeus, the Persian nobleman who fought Alexander at Gaugamela but soon after surrendered Babylon to him. Afterward Mazaeus became satrap of Babylon.

28 Especially see on mosaics located at Pella and Aegae (modern Vergina), dating from the fourth century, such as that signed by Gnosis, showing a stag hunt and two males (see below).

29 Pedley 2002: 313, no. 9.38.

30 Suhr 1979: 86.

31 Museum inv. no. MA 436, originally dated c .330. See Stewart 1993: nos. 45, 46.

32 Museum inv. no. MA 436. H: 68 cm. The eyebrows, nose, and lips are restored, dated c. 330 BC; Stewart 1993: nos. 45, 46.

33 Claudian copy of an original discovered in the Licinian tomb on the Via Salaria in 1885, dated c .60–50; H: 0.26 m.

34 At the Musée Nationale du Chateau de Malmaison, Rueil. See Toman 2000: 376.

35 Moreno 2001: 102, pls. 48 and 49, argues that the mosaic is a copy of an original painting by Melanthius or Apelles.

36 A famous such scene is the relief sculpture at the London Museum from about 660–636, titled King Ashurbanipal Hunting a Lion at Nineveh. For Alexander hunting lions, see Stamatiou 1988: 209–17. See also the wall painting on the facade of “Philip’s Tomb,” in Andronikos 1992: 100–19, figs. 58–63.

37 Moreno 2001.

38 Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence; date: 1505–6. De la Croix et al. 1991: 646, no. 17–15.

39 Louvre, Paris; date: c. 1485. De la Croix et al. 1991: 635, no. 17–1.

40 Andronikos 1992: 90–1, no. 49.

41 Ducal Palace, Mantua; date: 1474. De la Croix et al. 1991: 629, no. 16–65.

42 Stewart 1993.

43 Robertson 1993: 97–101; Pollitt 1986.

44 For the dress and styles of young men in antiquity see Geddes 1987.

45 Geddes 1987. For images of young men on white-ground lekythoi, see Tzahou-Alexandri 1998: 89.

46 Pollitt 1986: 40–2, no. 35.

47 Moreno 2001: 102–4. See Moreno 2001 for bibliography on the two youths, note nos. 73, 74. See also Plin. HN 35.80; Plu. Arat. 12.3.

48 Moreno 2001. For an extensive discussion of this interpretation of the mosaic see Moreno 2001 and Zevi 1998. See also Plu. Alex. 31.6; Devine 1985, 1986; Cohen 1997.

49 Winter 1909; Rumpf 1962; Moreno 2001.

50 Fuhrmann 1931. The original painting is believed to have been a private commission by Cassander. Some scholars believe that Apelles made the original during Alexander’s lifetime. Others name a Helen as the artist of the painting.

51 See Stewart 1993: app. 4 for bibliography; Moreno 2001. Archaeology Magazine (2006): 36–9 shows images of the restoration of the mosaic. See also Andreae 1977; Zevi 1988; Dondener 1990; Cohen 1997; Zevi and Pedicini 1998.

52 Mosaics made of tesserae appear during the second century; Macedonian mosaics were made of pebbles.

53 Cited in Moreno 2001: 11.

54 See also the Niobid Painter.

55 Zevi 1988; Zevi and Pedicini 1998.

56 Tempera on wood; Gardner 1991: 601, pls. 16–29.

57 The Greeks did not think leggings acceptable attire for civilized people. For reception and interpretations of encoded images see Eco 1976 and 1990.

58 See Mingazzini 1961: 7–17; Frel 1979; Archer 1981; Pollitt 1986: 23; Frel 1987.

59 See plates in Stewart 1993: no. 65; Pollitt 1986: no. 23. The image sits in the winter triclinium of the House of the Vettii at Pompeii, west wall.

60 Plin. HN 7.125.

61 Pollitt 1986: 22–3.

62 Ael. VH 2.3. See also Stewart 1993: 377.

63 Plin. HN 35.94.

64 See Pollitt 1986: 28–9, no. 17.

65 Hellenistic Baroque is a subdivision within the artistic development during the Hellenistic era. It often combines theatrical elements, as well as much pathos (strong emotion) as seen in the Laocöon, attributed by Pliny to the Rhodian sculptors Hagesander, Polydorus, and Athenodorus, dating from the second to the first centuriesBC or the first centuryAD in the Vatican Museum, Rome. See Pollitt 1986 and Ridgway 1990.

66 The so-called neoclassical tradition in Hellenistic sculpture takes its name from works of art that were created by artists who were consciously reviving and imitating forms of the Classical period, c.480–340. Some of these works include the colossal statue ofAthena from Pergamum (c. 175), at the Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, or the Aphrodite of Melos (c. 150–125) in the Louvre, Paris. See Pollitt 1986: 164–72.

67 Plin. HN 35.94. See also Zanker 1968; Pollitt 1986.

68 Museum inv. no. 609.

69 Plu. De Is. et Os. 24; Plu. De Alex. fort. 2.2–3; Stewart 1993: 395, 404, 405.

70 Stewart 1993: 163–71 divides the statuettes with a lance into three types: the Fouquet type, the Nelidow type, and the Stanford type.

71 For numismatic production relating to Alexander and his Successors see Bellinger 1963; Davis and Kraay 1973; Smith 1989; M0rkholm 1991; Price 1991; Stewart 1993; Holt 2003; Pandermalis 2004; Kroll, 2007.

72 Robertson 1993: 89.

73 Pollitt 1986: 1.

74 Now in the Louvre. See Pollitt 1986: 114–16, 296.

75 Kleiner 1992: 34–5, no. 11. See also Stewart 1993.