14

Diana Spencer

Introduction: Reception and Knowledge: Making Up Alexander

Thinking about Alexander the Great means thinking about a character generated by the cultural politics of the Roman world. Roman culture is saturated with themes that scream “Alexander” – knowing glances and nods to a foreign king who became deeply embedded in the experience of being Roman in the first and second centuries BC and AD. In fact his importance for Rome was so intense that Roman texts (in the broadest sense) have drowned out most earlier (and contemporary) accounts of Alexander, leaving us with a figure that is almost wholly modeled by Roman anxieties, interests, and enthusiasms.1 Imperialist, monomaniac, alcoholic, narcissist, mystic, visionary: the seductive combination of fascination and horror which fed the posthumous Alexander industry seems already to have been present, in embryo, in his own publicity machine.2 From the very start, thinking about Alexander has been influenced and invigorated by his reputation as a man who understood the vital importance of fame for increasing one’s authority. For Romans living through the turbulent late republic, emphasis on individual celebrity and the ability to position oneself as an outstanding personality were setting politics along a track that would eventually lead to the principate. In this particular political and cultural climate at Rome – a world view intensely influenced by the modes of authority deployed by the Hellenistic kingdoms that succeeded Alexander – his significance as an underlying and at times even explicitly invoked model is difficult to overestimate.

Taking Scipio Africanus as a notional starting point, and concluding with Hadrian, this essay suggests that we read Rome’s Alexander as an inevitable precursor to and even by-product of Roman imperialism in the late republic. Furthermore, this approach makes cultural consciousness of “Alexander” (Alexander-as-meme) central – with hindsight at least – to the political changes that transformed Rome into a superpower. Perhaps it is an overstatement to assert that all Roman questions and answers inevitably lead to Alexander, but through a three-part examination of Rome’s cultural permeability to Alexander during the late republic and early empire, we may find that placing Alexander at the heart of Roman systems of interrogating, understanding, and categorizing the world is less tendentious than it might, at first glance, seem.3 This essay commences with the figures that we tend to identify as prime candidates for being Alexander at Rome. Focusing, then, on the significance of Alexander’s campaign historian Callisthenes for Roman interest in Alexander we can think through why control of historical narrative is such an important feature of Alexander’s mythography. Finally, I suggest that we conclude with “Alexander” as a mode for the systematization of knowledge at Rome. Taken together, these approaches show how Roman voices and spaces speak directly about Alexander as an epistemological model for politics, culture, and identity.

Being Alexander the Great – A Roman Complex?

Identifying particular Romans as potential “Alexanders” is only the start of the interpretive process that faces us when we explore the place of Alexander the Great in Roman self-fashioning. We are also faced with another dilemma: to what extent are comparisons with Romans primarily about “Alexander,” or their Roman protagonists, or indeed the authors themselves? After all, Cicero likening Caesar to Alexander is rather different from Plutarch or Appian doing so. Pompey is perhaps the most obvious starting point, if only because he gained the same sobriquet magnus which so sets Alexander apart, but he is certainly not the only late republican “Alexander.” We can, in fact, commence with a brief glance back to the place of Alexander in retroactive accounts of Scipio Africanus, a figure whose struggle against Punic (i.e., Phoenician) Carthage, and whose mythical qualities and legendary chastity are all complicated by the nostalgia of hindsight. The supposed proskynesis of the waves before Scipio at New Carthage, facilitating the city’s fall and echoing the story of the sea’s deference to Alexander at Mt. Climax, is a particular case in point.4

Eventually, it is left to Juvenal (Satires 10.133–73) to turn the Scipionic model on its head. Rather than comparing Scipio with Alexander, or alluding to Alexanderstyle behavior on his part, he reinvents Alexander as the culture monster Hannibal. By identifying Alexander with Rome’s evil genius, the general who commanded Carthage (the only superpower seriously to threaten Rome itself), Juvenal binds Alexander’s dangerous possibilities into a story of Rome’s imperializing success, transforming Scipio, the “Roman” Alexander and conqueror of Hannibal, into a new and improved version.5 Despite the cynical and even horrified overtones that typify accounts of post-republican Alexanders – and the attendant complications of reading Scipio through the voices of authors living in a wholly different world – exploring the kinds of things that make these potential Alexanders stand out offers a fascinating insight into how History and identity were being fashioned.

Pompey and the Beginning of the End

Although reception of Pompey’s Alexander qualities are colored by the political maneuverings of Marius and Sulla at the beginning of the first century, he does seem to have been the first Roman to encourage widespread and explicit comparisons between himself and Alexander.6 Pompey’s links with the influential Stoic philosopher Posidonius of Rhodes (whose interests also extended to history and political theory),7 might well have attracted Pompey to aspects of Alexander’s image beyond those of military glamor and personal style. Alexander’s potential as a model for intellectual inquiry, imperializing topography and cultural colonialism offers an important subtext to accounts of Pompey’s eastern achievements. Pompey’s three Triumphs (over Hiarbas, Sertorius, and Mithridates) located him as the conqueror (albeit for Rome) of the three continents. As master of the world and the man who defined the boundaries of the world and Rome, we can see how significant public images of world domination must have been for his image, and in particular for any attempts to position him(self) as Alexander’s successor on the world stage.8

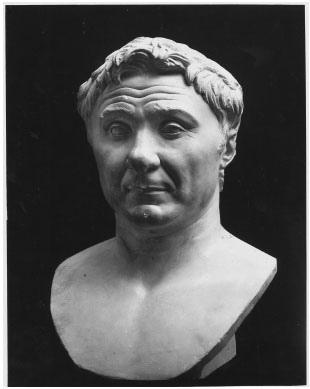

Figure 14.1 Pompey the Great, Roman, first century BC . Carlsberg Glyptotek, Copenhagen. Photo: Alinari/Art Resource, New York.

One way in which Pompey may have tried to combine both intellectual and military aspects of Alexander’s authority was in his sponsorship of Theophanes of Mytilene as a personal historian (on which see Strabo 1.1.6); more generally, one might also see traces of it in his creation of a cultural and intellectual milieu that could secure control over his reception.9 By modeling his arch-enemy Mithridates of Pontus as a new Hannibal, Pompey might nod to Scipio while also –potentially – demonstrating a cause for war not dissimilar to Alexander’s campaign of retribution against Persia. Just like Alexander, Pompey could disseminate a version of his campaign that transformed it into a civilizing mission, spreading law and order, and extending the boundaries of science and knowledge.10 Contemporary responses to this self-promotion, and a rigorous program of public and monumental texts, make it seem likely that this was self-association –indeed, imitation– rather than simply a process of ascribing Alexander-style qualities after the fact. We can see this at work in Pompey’s foundation of eponymous cities (e.g., Pompeiopolis in Cilicia), the trophy he erected in the wake of his victory over Sertorius (adorned with his statue and an inscription enumerating his conquest of 876 cities), and the similar iconographic program at his theater, developing his identification as kosmokrator.11

Breathless and admiring comments on Pompey’s magnificence in Pliny’s Naturalis historia are doubtless colored both by (Antonine) hindsight and Pompey’s successful image-making as a man guided (at least in part) by scientific and intellectual principles; but the glamor of Alexander is rarely far away.12 However apocryphal it may have been, the story of Pompey driving through Rome in triumph in 61, wearing Alexander’s cloak (which he just happened to have found among Mithridates’ belongings) was far too good to pass up.13 Likewise, his retrospectively reported attempt to harness four elephants to his chariot for the Triumph awarded after his victory over Hiarbas – thwarted only because the arch spanning the route was just too narrow – offers a tantalizing and irresistible set of connections to Alexander’s self-positioning as eastern conqueror that even Paul Zanker (1988: 10) was unable to resist.14 A Tiberian era slant on Alexander’s problematic associations may be surfacing in Valerius Maximus (6.2.7), who recounts a story of M. Favonius accusing Pompey, in 60, of wearing a diadem and aiming to turn Rome into a monarchy. Writing in the fourth century AD, Ammianus Marcellinus (17.11.4) suggests that Favonius had in fact misinterpreted a “bandage” that Pompey was using to cover an ulcer. It is unclear how diadem-like a bandage could really be! As such later anecdotes suggest, the glory and sparkle of being Alexander at Rome has a flip side, and we see his charm continuing to unravel if we turn to Caesar and Crassus.15

Caesar and Crassus

Conquests in the east gave body to Pompey’s status as Rome’s Alexander, and without this tangible military glory, positioning himself as conqueror of Alexander’s “east” (Rome’s notional antithesis) and attempting to play up a physical resemblance to Alexander would have been more likely to tend toward bathos rather than glamor. Nevertheless, Pompey’s eventual political decline at Rome suggests that deploying “Alexander” qualities at home might prove rather more complicated than being a glamorously reported and victorious “Alexander” in Asia Minor. Our impression of Pompey’s career as, ultimately, a failure, suggests that invoking Alexander at Rome was likely to drag overtones of despotism and monarchy into the heart of an empire that still defined itself as a place from which kings were excluded.

What we now term the “First Triumvirate,” an unofficial coalition between Pompey, Caesar, and M. Licinius Crassus, drew together three men for whom Alexander proved to be an increasingly problematic running mate. The late 60s were colored by jostling for power between Caesar and Crassus, whilst Pompey was cutting a swathe through Rome’s eastern problems. Caesar’s tactical transformation of the west into a theater of empire to match the sexiness of Pompey’s (and Alexander’s) eastern exploits left Crassus in search of a conquest to match them. Perhaps it was in an attempt to claim conquistadorial charisma for himself that he launched an expedition against the Parthian empire. For a man attempting to shed the role of financier, this was a bold maneuver.16 Pompey’s defeat of Mithridates had dragged Alexander’s military glamor firmly into his repertoire of attributes, but Mithridates was still only king of Pontus – not a name to conjure with. The Parthians, on the other hand, could be identified fairly straightforwardly as the successors to the Persian empire. And that would, of course, make their conqueror into Alexander. Crassus enjoyed some early success in Mesopotamia in 54, but it was at Carrhae, the following year, that the decisive battle was seared onto Rome’s imagination. Crassus’ army was wiped out, he was killed, and those soldiers who survived ended up settling in Parthia as POWs. Perhaps even more disastrously, the legionary standards were lost.17 This calamity haunted Roman policy in the east, and was still continuing to overshadow attitudes to expansive imperialism in the second century AD. Suddenly, rather than offering an exciting, wealthy new world for Roman flexing of military supremacy, the “east” became a zone which might put Romans at a disadvantage – physically and psychologically.

We can see all of these complex associations playing themselves out in Julius Caesar’s subsequent career, but before looking briefly at their potential impact on his assassination, it is worth setting the scene. Stories of Caesar as the gods’ favorite seem to have associated him with Hellenistic patterns of divinely favored monarchy, which themselves look back to the complex relationship between Alexander and the Successor kingdoms and are echoed in elite image-making in late republican Rome.18 Caesar’s famous lightning strike warfare (celeritas bellandi) becomes a key element in the positive connection between the two men, even if we have no clear or contemporary evidence that this was a consciously “Alexander”-style tactic on Caesar’s part.19 Plutarch’s decision to pair Caesar and Alexander in his series of “parallel” Lives is both telling and infuriating. It makes it clear that this kind of comparison was, at least by the late first century AD, acceptable and even straightforward, but his apparent assumption that readers will know the background to the comparison makes it difficult to analyze how it might have worked in the mid first century, and in the aftermath of Caesar’s assassination. Still, even Peter Green, usually doubtful of the contemporaneity of links between Caesar and Alexander, sees echoes of self-fashioning in Caesar’s supposed regret when faced with a statue of Alexander in the temple of Hercules at Gades (69) for his own paucity of achievement (at a similar age).20

Cicero’s self-conscious attempts to work up a letter of advice to Caesar, modeled on Aristotle’s guidance of Alexander, show us one way in which even after Pompey,

Alexander could be redrafted as a positive political model.21 The virtue of clementia (forgiveness) is perhaps the other obvious example.22 Clementia connects Caesar directly to Scipio and Pompey, but also ties him posthumously to Augustus’ program of post-civil war renewal at Rome.23 It is in accounts and texts of the years leading up to 44 that we see Alexander’s potential as a popularity winner at Rome breaking down, and this coincides with a gradual ratcheting up of negative associations with Caesar. We find Caesar’s style increasingly being characterized as more ostentatiously autocratic, and his authority as being less and less clearly dependent upon traditional codes of political practice and the mos maiorum. The corollary to these trends is a nexus of associations between Caesar and tropes of monarchy, tyranny, luxury, and self-interest. This in turn may be paralleled in the recurrence of dominatio and libertas in political rhetoric.24

Clementia suggests moral as well as military authority, and combined with a developing network of visual tags which connected Caesar to monarchical style, it is unsurprising that his political enemies had little difficulty in making his plans for a campaign against Parthia into an aspirational blueprint for a return of the trappings of autocracy to Rome. We gain a vivid (if rather belated) picture from a series of authors, suggesting that Caesar wore a “regal” purple toga, a laurel wreath, and a style of boot associated with Etruscan kingship; he was even portrayed on contemporary coins, an honor typically associated with dead “heroes” (or at least notionally heroic ancestors) or gods.25 Taken in conjunction with the events of early February 44 – when Caesar, sitting on a gold seat at the foot of a statue of himself, was waited on by senators in front of his temple of Venus Genetrix, he is reported to have refused to rise to meet them; infamously, then, at the Lupercalia festival he supposedly acted out a scene of “refusing” a diadem from Antony – the assassination in March of that year seems (narratologically) almost inevitable.26

Antony and Augustus: From Republic to Empire

Being Alexander in the wake of Caesar was a fraught enterprise, so it is unsurprising that his direct, named heir, Octavian, distanced himself from the taint that being Alexander carried. Antony, however, was trapped – whether by himself or by enemy propaganda it is not entirely clear, since we have little trace of the kinds of anti- Octavianic rhetoric that his supporters may have indulged in, but are well supplied with propaganda from the winning side. In effect, our story of Alexander from the years before Actium (31) is a story concocted by Octavian and his partisans, with occasional glimpses into the ways in which Antony might have retaliated or set his own agenda.27 Antony’s use of solar imagery, both on coins, and for his son (with Cleopatra), Alexander Helios, connects into the kind of astral symbolism that characterized deification in the wake of Alexander, and that was almost certainly implicit in the anxieties concerning a waning of the sun and the comet that followed Caesar’s death.28 But while this kind of imagery was gaining currency in the late republic, Antony’s liaison with Cleopatra and his Parthian expedition located him in much more problematic territory. In effect, by choosing the “east” as his operational field, and leaving the west to Octavian (and, more tenuously, to Lepidus), Antony commenced a process of self-fashioning as yet another Roman Alexander that was to have disastrous consequences.

Excessive drinking and partying is a feature of late republican invective that used Alexander as a frightening model, and became closely identified with Antony. This is summarized neatly by the Younger Seneca (Ep. 83.25) when he tells us that drunkenness, a love of wine, and Cleopatra drove Antony into foreign vices and ruined him – in effect, it is a combination that Seneca claims turned him into a barbaric, oriental despot.29 Sex, surprisingly, is not typically a feature of Roman invective against Alexander, but I suspect this is because drunkenness is used to such eloquent effect as a way of modeling effeminacy, bodily weakness, and mental degeneracy. Obsession with sexual pleasure can then become another feature of the lifestyle that a drunken degenerate might enjoy. What this style of polemic against Antony makes clear is that alien and debauched imagery was applied to Antony as part of a coherent oppositional model to “Romanness” – a bundle of qualities laid claim to by Octavian.30

The “east,” in these terms, is less a place than a state of mind, and it is for this reason that Antony’s self-association with Dionysus, Hercules, and of course Alexander was all too successful, and eventually disastrous.31 Within Roman popular consciousness, it is clear that Antony could plausibly reinvent himself as the conquistadorial, civilizing successor to Dionysus and Hercules, just as Alexander seems to have done. But since this imaginary eastern realm was also one in which excess, luxury, despotism, and gender inversion exercised an aggressively seductive hold on everyone who crossed over, Antony’s susceptibility to the dark side of the comparisons was inevitable.32 And not just with hindsight. By associating himself with Apollo, Octavian allowed himself the luxury of joining battle on a divine front, whereby the gods of the “west” were inevitably more powerful than those of the “east.” By contrast Antony was enslaved to barbarian Cleopatra and Egyptian Osiris, and, tellingly, was said to want to shift the imperial capital from Rome to Alexandria.33

In the light of this, controlling connections with and reception of Alexander at Rome takes on a deadly seriousness. Most importantly, it must have been evident that, to succeed, it was vital not to become marginalized as a Roman playing at Alexander in a decadent eastern ghetto. Positive Alexander imagery (military success, divine favor, charisma, popularity) needed to be assimilated into mainstream Roman understanding of successful imperialism, and neutralized. This required the exercise of clementia, as Octavian demonstrated effectively, and a process of redefinition and appropriation that attempted to write explicit references to “Alexander” out of the newly developing ideology of the principate. This new political model demanded a sense of combined mastery of east and west, which we see expressed strategically by Virgil’s comment (via Anchises) that Augustus’ imperium would encompass the annual passages of the constellations and the sun (Aen. 6.795–6). That said, Alexander does not wholly disappear, and he continues to crop up as a reference point for the early years of the Augustan principate in particular. Later accounts tell us, for example, that Octavian apparently spared Alexandria because of its founder’s magnificence, and went on to use Alexander’s image on his personal seal ring.34 Nevertheless, as the reality of autocracy at Rome became increasingly apparent, in particular after 27, Livy’s programmatic decon- struction of Alexander as a viable or even interesting enemy for Rome sets a formal limit to speculation.35 Given Augustus’ decision to set limits to Roman imperialism, the danger of invoking a despotic, degenerate Alexander rather than his positive achievements probably insured his slippage out of contemporary political currency.36

Germanicus: The Perfect Prince

Despite, or perhaps because of, the anxieties about how to succeed (or be successful) after Alexander that clustered around accounts of his death, Alexander never figures explicitly in Augustus’ strategies for engineering the succession of power and keeping it within his own family, in what was notionally not a hereditary monarchy. Instead, parallels with Alexander reemerge around the person of Germanicus. The elder Pliny is delighted to recount a connection between Alexander, Augustus, and Germanicus which transforms all three into fellow equestrians (a nice Roman touch) – Alexander’s affection for his horse, Bucephalas, is legendary, and Augustus did not quite manage to outdo the gift of a city (Bucephalia) as a monument. That said, Pliny tells us that Augustus’ horse did receive a funeral mound, and that Germanicus composed a poem about it (HN 8.154–5). Horses (and their monarchical associations) continue to be important for Alexander at Rome, but Pliny’s story is only a foretaste of Tacitus’ complex introduction of Alexander to Germanicus’ death in the Annals.37 When Germanicus engaged in what Tacitus traces as a kind of Alexander-style progress through Rome’s eastern empire, he was picking up on a motif that other authors also notice, but that reaches its most impressive development in the Annals.38

Tacitus transforms Germanicus into a glorious might-have-been whose brief perfection is undercut by increasingly problematic clusters of association with Alexander. In Athens (2.53) and Alexandria (2.59.3) we find Tacitus characterizing Germanicus as gradually shedding what he terms his “Caesarian” dignity; taken together with Germanicus’ acceptance of a crown in Parthia, we can see how echoes of Caesar and Antony (his splendidly legitimating ancestors 2.53.1–3) saturate this eastern tour. Alexander looms disastrously over the whole series of episodes, offering a knowing foretaste of Germanicus’ ultimate fate – to die young, amid rumors of foul play, leaving a distraught and helpless nation.39 The perfection that characterizes Tacitus’ Germanicus also hints at his lack of feasibility as a savior for Rome in the long term – he is (perhaps like the young Alexander) too good to be true. By dying young, Germanicus makes possible the elaborate comparison with Babylon after Alexander that characterizes responses to his death (2.82–3), but this use of Alexander also fulfills an important narra- tological function in the Annals. It allows Tacitus to represent this as a turning point, after which aiming for the perfect, idealized autocrat is recognizably impossible, and can lead only to the excessive disasters of Caligula and Nero (and perhaps by implication, Domitian).

Caligula, Nero, and Domitian: Alexander the Degenerate Despot

In Germanicus, Tacitus offers a glimpse of an idealized young Alexander, but his hindsight should remind us that much of our disquiet concerning Roman Alexanders is also refracted through authors from the mid to late first century AD. Looking forward to Caligula, Nero, and Domitian, we see familiar motifs recurring, but in the context of insane or excessive devotion to and (over)identification with Alexander and of an increasing inability to set and respect boundaries, whether personal, bodily, political, or imperial, or indeed between divine and mortal identity.40 We also see sexual excess being mapped onto a generalizing notion of barbarous and infectious luxury, which slots into a pattern of deception and treachery that has its roots in versions of Alexander worked out in more detail in Q. Curtius Rufus’ narrative.41 Finally, an atmosphere of secrecy and lies, a world in which even intimate personal relationships can be misleading, is at the heart of the younger Seneca’s (political) philosophy, underpins Lucan’s epic account of the previous century’s civil war and Tacitus’ Annals, filters through Suetonius’ Lives of the Caesars, and colors the Alexander who emerges in this era.

In stories of Caligula, comparisons with Alexander take on a whole new meaning. The association is no longer between an aristocratic, would-be Roman Alexander and Alexander, the prototype for imperializing monarchy. Instead we are presented with a ready-made Roman emperor who appears to embrace Alexander without any concern for the ways in which explicit association and comparisons might have caused problems in the past. Reports of Caligula’s enthusiastic assumption of the role of Alexander show just how quickly the principate developed from tentatively expressed “republican” autocracy to monarchy by another name. We can see responses to Caligula’s brand of autocracy (and its complications, particularly in the wake of senatorial responses to Tiberius) in accounts of Caligula’s preemptive celebration of a Triumph – wearing Alexander’s breastplate – before risking the vagaries of military campaign. By purloining Alexander’s body armor, Caligula thereby makes tomb-robbing a prelude to his other transgressive excesses.42 An attempt to make his horse, Incitatus, a consul (Suet. Calig. 55.3), may look back to Augustus’ horse and Germanicus’ poem as much as to Alexander’s memorialization of Bucephalas, but it also fits in with a pattern of dissolving socio-cultural boundaries, and even breaches in the dividing line between sanity and insanity that seethe through accounts of Caligula’s principate.

Boundary-breaking, of course, could still just about be read in a positive and even culturally assertive light vis-à-vis Alexander’s “civilization” of the east, despite problematic associations with Caligula. With Nero, however, we see how even this can assume traumatic overtones. Nero’s self-fashioning in Alexander’s style is on display in accounts of his explicitly aggressive policy toward Parthia, and his problematic relationship with his general Corbulo.43 Nero’s manipulation of a confrontation with Tiridates, using Corbulo as a field-general, highlights the kinds of tension that attempting to be emperor and Alexander could set up – sending a deputy to lead the armies was a fraught undertaking, and as the aftermath of Nero’s death demonstrated, it was from the ranks of successful commanders that imperial succession would be determined. Any anxiety on Nero’s part concerning Corbulo’s potential to be too successful was probably well placed. The highly stage-managed “submission” of Tiridates (AD 66) in Rome further demonstrates the impossible situation Nero faced once he had decided on imperial expansion into the east: he could not risk leaving the capital for long periods of time, but still needed to make Corbulo’s victory into his own Triumph. Tacitus’ narrative makes great play with echoes of Alexander, but eastern maneuvers are not the only way in which Alexander contaminates our understanding of Nero, and vice versa.

Suetonius’ account of Nero’s highlights (Ner. 19) includes a mention of his plan to tour Alexandria and Achaea, and in addition, to send a newly constituted “phalanx of Alexander the Great” (composed of six-foot-tall Italian recruits) out into Alexander territory (the Caspian Gates). Being able to command a whole series of subordinate “Alexanders,” ordering them to conquer at one’s command, almost puts Nero back among the intellectual games played by Livy when he speculated that Alexander would always lose to Rome because he was one man, whereas Rome comprised an endless succession of super-Alexanders (9.18.8–19). In conjunction with Tacitus’ complex characterization of Tiridates as both Alexander and Darius, and the philhellenism with which Nero is so disastrously associated, the younger Seneca’s obsession with Alexander as an ethical model comes as no surprise.44

Domenico Lassandro (1984) provides an overview of how Alexander fits into Seneca’s works, though he stops short of arguing (as I do) that Seneca’s use of Alexander drags “Nero” in implicitly, even when he seems to be absent. As Jacob Isager rightly suggests, Seneca’s Alexander, in both his good and his bad qualities (patron of the arts, hands-on commander, monomaniacal despot), is strikingly similar to the kinds of post-Neronian critiques of the emperor which make up most of our knowledge of his principate.45 What this suggests is that by the time we reach the AD 70s, rhetorics of imperial praise and criticism are persistently – if implicitly – dragging Alexander into the frame, and vice versa; this makes the elder Pliny’s exclusion of any mention of direct connections between Alexander and any of the post-Augustan emperors particularly fascinating.46 Traced through Pliny’s epistemological imperialism, we find a golden Alexander prefiguring and even propping up Augustus, while others (Antony, Caligula, Nero) take the fall for all that is wrong in Rome.

Domitian’s place in the parade of Roman Alexanders locates him at the intersection between man and god, artiste and patron, Princeps and Dominus. Statius, in his collection of ostensibly occasional poems (Siluae), conjures up an Alexander who is endlessly susceptible to revision (Silv. 1.1.84-90) – here, Alexander astride Bucephalas is frozen into Roman space in the Forum, before metamorphosing into Caesar and ending up in a dramatic face-off with the vast new equestrian Domitian. Alexander/Caesar’s inevitable displacement by Domitian makes clear the precarious nature of imperial identity and authority, and this opening poem leaves us in little doubt of its credentials as a statement of imperial passivity vis-à-vis immediate and longer-term control of reception. The torment and betrayal that suffuse Alexander’s relationship with his statue of Hercules (Silv. 4.6) dispel any lingering uncertainties about the implications of Alexander for Domitianic Rome.47 Here, With Domitian’s transgressive but irresistible demand to be characterized asdominus et deus we see the logical conclusion of drawing Alexander into Roman political rhetoric. Curtius’ vigorous denunciation of Alexander’s “enslavement” of the freedom-loving Macedonian people, and his attempts to introduce oriental subservience and even worship into relations between ruler and ruled key neatly into the kinds of post- Neronian rhetorics of dominatio (and damnatio memoriae) that cluster posthumously around Domitian.48

Picking up on Augustus’ visit to Alexander’s tomb and Caligula’s tomb-robbing, we find that from Nero to Domitian, death and afterlife and even the perils of immortality are rarely far from Alexander. Lucan’s Alexander (BC 10.20–52), like the later Alexanders of Silius Italicus,49 Statius, and Juvenal (Sat. 10.171–3), is a function of a world dangerously obsessed with the dead past. This simultaneous sense of closure and anxiety about what kind of world will ensue, reflects and also models elite concerns in the face of the melt-down after Nero, and the continuing instability that culminated in Domitian’s own death.50

Trajan and Hadrian: Parthia and Civilization

Trajan and Hadrian mark the formal conclusion to this series of Roman Alexanders, and as a pair, they encapsulate the promise of triumph and disaster that characterizes Alexander’s Roman imagery.51 Nerva’s smooth accession belied Tacitus’ packaging of his combination of autocracy and liberty (Agricola 3) and his speedy adoption of Trajan as his heir put a stop to threats of another descent into anarchy. Trajan’s title Optimus, granted in AD 114, connects him not just with Capitoline Jupiter (Optimus Maximus) but also acknowledges the implicit dangers of Greatness.52Meritocracy versus magnificence: we might see in this unspoken choice of honorifics an attempt to reinvest Rome’s emperors with some of the military kudos that Alexander might still connote. Reopening this military interface with Alexander also plays up Trajan’s best qualities as an imaginative and ambitious commander. Moving from triumph over Dacia in the early years of the second century AD, Trajan’s parabola through Arabia, Armenia, and on into Mesopotamia locates him squarely in a world where comparisons with Alexander are inevitable.53 Ideologically, the younger Pliny’s Panegyric maps out how inescapable this process of Alexandrification has become, and the connections are made explicit in Dio Chrysostom’s orations On Kingship.

Establishing a co-principate with Jupiter, whereby Domitian’s formulation dominus et deus becomes literally the case (Trajan and Jupiter ruling in partnership), side-steps (temporarily at least) the uncomfortable aspects of emperor worship that Domitian had bungled in Alexander’s shadow. Ancient authors highlight the significance of the conquistadorial trajectory from Alexander through Caesar and Antony to Trajan for interpreting these Parthian wars, but with Hadrian we see an interesting footnote to this optimistic assertion of Rome’s authority over the eastern world. Hadrian’s ethnographic and intellectual interests were catholic, and his empire in microcosm at Tivoli might be interpreted as a pleasure palace for a dilettante, a cabinet of wonders allowing him to enjoy the marvels of the whole world from a space in which imperial self-fashioning could reflect (on) Rome at a distance. His quasi-touristic approach to empire certainly looks back to the intellectual and scientific modes of conquest that informed the elder Pliny’s textual empirebuilding, and cluster around Pompey’s military success. Yet although Hadrian spent just over half of his reign traveling, his peregrinations were administrative and even personally motivated, rather than expansive. Hadrian’s principate, then, was susceptible to some of the rhetorics of assimilation (or “going native”) that were attached to Alexander’s progress into Persia, Antony’s relationship with Cleopatra, and Germanicus’ tour of the east and Egypt. Hadrian’s fascination with Egyptian cults in particular, leading to the posthumous deification of his friend (and probably lover) Antinous, seem to have interesting echoes of the propaganda surrounding Actium. It is also likely that connecting Hadrian with Egypt could have hinted at Alexander’s quest for deification at Siwah, and Lucan’s implicit syncresis of Cato and Alexander in a weirdly surreal and dangerous Libya, and at Siwah (BC 9.564–86).

Authorial (Self-)Fashioning and Making History: Callisthenes and Rome

One of the most fascinating voices that almost (but not quite) speaks to us about Alexander belongs to the man whom Alexander himself commissioned to write up an account of his expeditionary campaign: Aristotle’s nephew Callisthenes. Bluntly told, his story seems fairly unremarkable – he accompanies Alexander across Asia only to fall foul of the king’s increasingly uncertain temper, becomes embroiled in a plot against his life, and loses his own life as a consequence. But this summary barely touches upon the enduring afterlife that Callisthenes achieved in Roman stories of Alexander; thinking about reasons for his prominence locates us at the heart of the most topical political, cultural, and intellectual (never mind personal) cruces that faced the (would-be) movers and shakers of late republican and early imperial Rome. Writing (and, indeed, commissioning) History is never a culturally neutral activity. Engaging with the process of producing narrative history demands, at the very least, an acceptance that historians are involved in a complex series of implicit and/or explicit position statements concerning the nature of the account that they compose. For our purposes, asking why Alexander’s decision to commission an up-to-the-minute narrative of his achievements was so significant for Rome sends us back, in the first instance, to the potential crisis of Hellenic identity, threatened by Macedonian military supremacy.

Alexander succeeded his father Philip just as the Greek world was getting to grips with Macedon as the new superpower. What particularly complicated the relationship between Macedon and the rest of Greece in the mid fourth century was that despite Philip’s (and then Alexander)’s undeniable achievement in enforcing a Macedonian hegemony over the other Greek states, Macedon continued to be perceived as a barbarous, primitive backwater (see Zahrnt, ch. 1). We will never know, of course, what complex of reasons led to the elegant, propagandist solution that Philip kick-started and Alexander took to its ultimate conclusion: selling the new and uneasy coalition as a way of finally striking back at Persia to “punish” the empire for its invasions of Greece. In this light, Alexander’s country could be redefined as “Greek,” positioning Macedon at the head of a retaliatory and even culturally imperialistic crusade against an aggressive and tyrannous eastern threat. Callisthenes’ role in the process of realignment of identities is worked out against this backdrop. Although his execution on a charge of treason is not directly connected (as far as we know) to what he wrote in his history of the campaign, nevertheless our image of him, filtered through Roman voices, makes it clear that writing history is tantamount to articulating control over the (im)mortality of one’s subject.

Famously, reception of Alexander has immortalized him as a man who believed himself descended from both Heracles and Zeus. With Achilles thrown into the mix, this makes for a heady cocktail of ancestry. From these three, it is (the Homeric) Achilles’ role in modeling what “Alexander” signifies that resonates directly in Roman receptions, and it is to Roman interest in connecting Callisthenes and Achilles jointly to Alexander, indeed in foregrounding Callisthenes’ role in this aspect of Alexander’s story, that I now turn. The figure of Callisthenes’ opens up, for Roman authors, strategically interesting ways of focusing on and exploring relationships between historiography, autocracy, and individual responsibility.54 Reading Roman interest in connecting Alexander to Achilles via Callisthenes in these terms makes evident the complexity and wider significance of Rome’s engagement with Alexander. Speaking in 62, on behalf of the poet A. Licinius Archias (whose right to citizenship was in doubt), Cicero paints a picture of Alexander’s success and enduring greatness as wholly attributable to his correct understanding of the symbiotic relationship between Achilles and Homer. This is a relationship, Cicero stresses, which is replicated at Rome in Pompey’s support and patronage of the historian Theophanes of Mytilene.55 Moreover, this speech implicitly suggests that Alexander’s “greatness” exists only because of his subsequent decision to surround himself with a posse of writers who would Homerize him along similar lines.

Seven years later, Cicero returned to the same motif in an edgy and politically complex letter to the historian L. Lucceius (Ad Fam. 5.12).56 Here, Cicero’s own reputation and afterlife hang in the balance; specifically, his urgent need to insure that the history being written by Lucceius provides a favorable account of Cicero’s consulship, and his execution of the Catilinarian conspirators. What was implicit in his speech for Archias becomes bluntly explicit here – this is a win-win scenario for historian and subject. Alexander we are told, believed that art glorified both artist and subject; by the end of Cicero’s proposition, Lucceius himself has been turned into a great (magnus) and illustrious man (Ad Fam. 5.12.6-7). Cicero’s contention that creative association with great men of action allows writers and artists to take on something of their attributes draws a direct line between Homer and Achilles, Callisthenes and Alexander, Theophanes and Pompey, and Lucceius and himself. In making this connection, Cicero is locating Roman quests for individual gloria and posthumous renown in a tradition that is also intimately concerned with understanding and modeling one’s place in the world, whether as a state (Macedon, Rome) or an individual (Alexander, Pompey, Cicero). In order to insure a satisfactory, successful, and credible outcome, individuals and nations must control their representation, and that demands advance understanding of the desired narrative momentum.

Like Alexander (and Macedon), Rome in the third, second, and even first centuries was struggling to articulate a wholly satisfactory story of how and why it was more than a hugely successful military superpower. Cultural anxieties were understandable when faced with the highly developed intellectual and artistic milieus of the Hellenistic kingdoms of the Successors to Alexander’s empire, the mythopoetics of Greek historiography, and indeed the philosophical and political heritage still peddled by Athens. Rome lacked a developed tradition of History-making which would explain to the Mediterranean world at large why Roman imperialism was both right and inevitable. Perhaps more nebulously, Rome also lacked a rationale for dealing with (relatively) sudden wealth and luxury – the delightful rewards of empire that were increasingly changing what Romans perceived to have been their traditional austerity and way of life.

If we turn this position back to Callisthenes, from a Roman perspective we might now redefine him as one of Alexander’s coping strategies for unifying the Hellenic world, creating a successful strategic account of how and why Macedon was the leading state, and guaranteeing his own personal Greatness.57 Where this goes wrong, of course, is that the historical Callisthenes attempted to capture the center stage of History, and involved himself directly in a conspiracy against Alexander. For late republican intellectuals and politicians this presents a certain tension. As I have suggested, Roman readings of Callisthenes’ story as a primer for resistance to Alexander make him a useful model for men such as Cicero (and even Pompey) to deploy. Patronizing or encouraging a historian who, unlike Callisthenes, does not rebel might then suggest that one has avoided the worst of Alexander’s excesses, but it also opens up for consideration the possibility that writers can have a serious and long-term impact on politics and posterity that goes far beyond the written word. Moreover, although Alexander’s positive qualities seem initially to have been prominent in his reception in republican Rome, Callisthenes’ fate might offer a disturbing counterpoint to Alexander’s potential to stand for unalloyed “greatness” and “republican” (or consensus-based) monarchy. So we find that although before Antony, Alexander stands primarily as a successful self-fashioner, a man who promotes the idea of a cultural program that combines politics and military achievement in one overarching narrative package, a change takes place as the principate develops into a “hereditary” autocracy.

Instead of focusing on how one goes about creating and acting the role of being Alexander the Great, Romans become increasingly fascinated (and horrified) by how one responds to an uncontrollable subject who no longer seems confinable in neatly packaged story-lines. Developing Callisthenes’ role as a figure of resistance to tyranny and political oppression, indeed using him as a means of interrogating the kinds of freedom and discourse that are available to subjects (rather than citizens), could become a serious and even potentially dangerous proposition. It eventually offered one way for political philosophers to question models of citizenship and identity in Neronian Rome, but it also raised the specter of what happens when the relationship between an author and his subject breaks down.

Two first-century AD Roman authors whose interest in Callisthenes’ fall from favor is particularly illuminating are Curtius Rufus and the elder Seneca.58 Curtius’ lengthy account of Callisthenes’ downfall is interwoven into a narrative that is increasingly driven by suspicion, megalomania, plots, and treason, rather than by magnificent achievements or even the marvels of the east. In his Callisthenes we find characterization and language that are increasingly evocative of Roman senatorial anxieties in the face of ever more absolute autocracy.59 Simultaneously, Macedonian resistance to (what Curtius represents as) Alexander’s ever more “orientalized” behavior, is configured in strikingly Roman terms. In effect, Curtius’ stalwart, luxury-hating and down-to-earth Macedonians take on many characteristics that suggest they act as stand-ins for Romans in his conception of the story. And Callisthenes functions as a focus for narratological expressions of dissent.60 These come dramatically to a head with Alexander’s attempt to introduce proskynesis – a Persian gesture of obeisance to a social superior which Roman authors tend to interpret as full-body prostration on the ground, and to deprecate as an indication that the recipient was being worshiped as a god.61 Callisthenes’ intensely Roman refusal to performproskynesis in Curtius’ story is couched in terms that instantly key into Roman rhetorical contestations of identity. Curtius’ positioning of Alexander, eavesdropping on Callisthenes from behind a curtain, hammers home the kind of ideal response he is attempting to generate (8.5.21). Callisthenes’ response to proskynesis, in Curtius’ narrative, makes it plain that Alexander’s monarchy is increasingly losing touch with the kinds of “democratic” style of rule that initially characterize idealizing versions of Macedonian autocracy.62

Turning to the elder Seneca’s interest in Callisthenes, we find ourselves confronted with a discourse positioned at the heart of elite citizen identity. Learning to manipulate and control the citizen body using public speech was central to senatorial self-fashioning in the republic, and continued, even if solipsistically, to function as a model for citizen excellence in the principate. It is likely that Seneca put together his anthology of epideictic declamationes (known as suasoriae) for his sons late in his life, and in doing so he was both looking back to exemplary practitioners of oratory, and also collecting up a package of themes on which young Roman aristocrats could be expected to have something to say.63 So far, so straightforward. But Seneca had more than an antiquarian’s interest in the epistemology of declamatory identity. Alongside his catalogues of suasoriae andcontrouersiae he also wrote a highly topical history of Rome from the civil wars to his own time, and his suasoriae are suffused with a sense of poignancy suggesting a genre and discourse already in a process of decline.64 This indicates, I think, that he was wholly aware of the biting significance that performing Alexander might have for a young Roman aristocrat.

The first sample theme in Seneca’s collection of suasoriae is the practicability of Alexander’s desire to explore the Ocean that bounded the world. Here, “quoting” the Augustan rhetorician L. Cestius Pius, Seneca boldly sets out a model for public speech (and thereby personal autonomy and identity) under a tyranny (1.5). This practical handbook for courtiers presents us with an uneasy sense that by the first century AD, “Alexander” has become shorthand for inappropriate self-importance, delusions of grandeur, political crassness, and (murderous) lack of proportion in interpersonal relationships.65 Moreover, “Cestius’ “ ability to conflate the stories of Callisthenes’ execution for treason and Cleitus’ murder for a pointed (and drunken) joke at Alexander’s expense, suggests that “Alexander” has taken on a Roman life and identity that no longer requires a direct connection to a consistent biographical tradition. In effect, Seneca’s representation of Callisthenes in this suasoria demonstrates problems of breakdown in category that have significant implications for understanding cultural change at Rome, and Alexander’s role in this process. “Cestius” tells his audience that Callisthenes’ death (speared by Alexander) is a result of an unwise joke (urbanitas) that ichor rather than blood should flow from a wound received by the king. Callisthenes is described as both teacher (praeceptor) and philosopher to Alexander, but his death here is a function of his having stepped beyond both roles, taking on the guise of (satirical) commentator. This demonstrates the ambiguity inherent in the relationship between subject (willing or otherwise) and authors, and between advisers and advisees. And at Rome, the relationship between authorship and advisory, didactic discourse was extremely close.66

Alexander and the Sum of All Knowledge

The characters that make up our set of Roman Alexanders do not, as I have been suggesting, exist in a cultural vacuum. Alexander is implicitly and explicitly embedded in Roman intellectual taxonomies and gradual development of a self-conscious imperial world view. While this weaves in and out of the characters and texts that I have been discussing, it is also on display in the burgeoning field of scientific and technical writing that Roman authors make distinctively their own from the late republic onward. Three authors in particular demonstrate Alexander’s centrality to Roman epistemology: Vitruvius, Strabo, and the elder Pliny.67 It is in their attempts to categorize, describe, and lay claim to a controlling understanding of the world (and Rome’s place in it) that Alexander’s impact is embedded in the longest term.68 When Vitruvius recounts Alexander’s topographical near-metamorphosis into Mt. Athos, he is not just providing Romans with a concrete example of how supreme commanders have a dramatic effect on their landscapes; he is also offering a narratological reification of the psychological impact of imperialism on how reality is experienced.

Alexander is rarely far from Strabo’s concerns in his opening imperial benchmarking statement. For Strabo, Alexander’s campaigns connect the newly and increasingly Roman Mediterranean (17.1.6-13 on Alexandria and Egypt, from “then” to “now”) with the mythic worlds of Troy (1.3.3, 13.1.27) and the Amazons (11.5.4–5) while also locating him squarely at the start of the process of scientific inquiry into space and territory that drives his own intellectual plan of campaign (1.2.1).69 We can see this in his fixation on Alexander as a man who supported and promoted the process of mapping as a key strand in conquest: in order to refashion a new identity for conquered peoples, it was vitally important to understand and control how they are and have been categorized and defined (1.4.9, 2.1.6). Ultimately, we see in Strabo an understanding that Alexander himself, in turn, is transformed into a benchmark for later attempts to measure the world (2.1.24, 3.5.5). Strabo’s Alexander is at once self-aggrandizing (11.7.4) and gullible – and thereby flawed in his conception of the world (15.1.28).70

In Pliny’s Naturalis historia we can see how time and space combine to portray Rome’s empire as a kind of magnificent diorama, a spectacular show that acknowledges the lure of the circus, but presents us instead with an imperial panopticon, ordered by a narrative of intellectual and scientific inquiry. When Pliny tells us (HN 2.5) that Vespasian was the world’s greatest ruler ever, he was doing more than simply nodding to the newest über-patron (father of Titus, Pliny’s addressee). He is also setting up a taxonomic model that cuts to the heart of Roman understanding of the world; in effect the empire in Vespasian’s shadow will be defined and categorized inasmuch as it relates to knowledge required by Rome at its center. A side effect (perhaps) of this model is that Pliny’s focus is forced out to the edges of the empire, the places that generate the stories that are directly relevant to Rome’s glorious progress (27.1). By synthesizing, assessing, and outdoing previous (and Greek) attempts to understand the natural world and to locate the role of nature firmly as a function and feature of Rome’s pacification of the world, Pliny makes himself a worthy match for the military men who previously controlled exploration and thereby acquisition of knowledge.71 Just as Pompey, in Pliny’s account, matches Alexander and almost equals Hercules and Father Liber in the brilliance of his exploits (HN 7.95, 96), Pliny implicitly suggests that on Rome’s behalf, he reconquers the world and holds it fast for Rome.72

The mutability of the world, the transience of physical features, forms an important strand in Pliny’s rationale – without a structured record of the processes of change and the ability to create historically aware accounts that can capture and control (intellectually, at least) this process, no empire can last. Alexander’s flawed understanding and faulty epistemology mean that although he tries frantically to achieve an empire founded on knowledge, his lack of structure and control over the wide-ranging kinds of information that poured in mirrors his lack of rationale for sustainable empire-building.73 Human progress, in Pliny, means learning to understand, use, and control the natural world, and in these terms, transmission of this knowledge is vital to the imperializing mission. Papyrus, according to Pliny, began to be transformed into paper only with Alexander’s foundation of Alexandria (HN 13.27).74

This essay concludes, then, with paper; and in particular, the close relationship between the reception of Alexander, the hermeneutics of classical identity, and the physical processes by which knowledge was transmitted.

1 For the backstory of how and why Alexander keyed so elegantly into Rome’s political and cultural concerns in the second and first centuries, see Spencer 2002: 9–38. On the lost histories of Alexander, see Pearson 1960, and more briefly, in summary form Baynham 2003: 3–13. An excellent introduction to the major narratives of Alexander from the early Roman empire is Atkinson 2000b. This essay focuses on the allusive and pervasive impact of Alexander on the popular imagination, rather than dealing with the narratives for which Alexander is the primary focus.

2 Most straightforwardly, we can see this in the control exercised over “official” images, characterized by the works of Lysippus and Apelles. The wide-ranging impact of Alexander’s tightly controlled iconography is discussed in detail in Stewart 1993. The most useful recent discussion is Stewart 2003; see also Moreno 1993, Killerich 1993, and Nielsen 1993; see also Mihalopoulos, ch. 15.

3 Though approaching the topic from a wide variety of angles (e.g., Quellenforschung, historiography, biography, cultural studies, literary criticism) the second half of the twentieth century onward has seen a dramatic growth in reception of Alexander at Rome. The most recent extended study is Spencer 2002 (which includes an extensive bibliography). Isager 1993 offers a concise summary of Roman Alexanders from Pompey to Vespasian, but the breadth of coverage allows for little detailed engagement. Other exciting and challenging approaches to Alexander reception in antiquity include three collections (Sordi 1984b; Croisille 1990b; Carlsen et al. 1993) and a handful of individual essays (e.g., Ceau^escu 1974; Green 1989a; Baynham 2003).

4 On Scipio and Alexander see, e.g., Livy 26.19.5–7 and Dio 16.38–9, 17.63 (conversations with Jupiter and divine father); Livy 35.14.6–7 (conversation with Hannibal, about Alexander); Livy 26.50, Dio 16.43, and Gell. 7.8.1–6 (chastity of, at New Carthage – on this, see Spencer 2002: 172–5); Sil. Ital. Punica 13.762–76 (Alexander as his compromised, dead adviser – on this, see Spencer 2002: 162–3). For echoes of Alexander in Scipio’s success at New Carthage, see Plb. 10.8.6–10.9.3, 10.11.6–8, 10.14.7¬12; Livy 26.45.8–9 (cf. Plu. Alex. 17.3–5; Arr. 1.26.1–2). Scipio’s acclamation as Inuictus connects him at least associatively with Alexander, the ultimate invincible leader (see, e.g., Ennius Operis incerti fragmenta annalibus fortasse tribuenda 5 (var. 3) V, in Skutsch 1985; and posthumously, Cic. Verr. 4.82; Rep. 6.9; Livy 38.51.5); this also drags him forward into subsequent usage by Pompey and Caesar. A succinct account of Scipio’s associations with Alexander can be found at Green 1989a: 201–2; see also Spencer 2002: 168–9.

5 For a more detailed discussion, see Spencer 2002: 157–9.

6 Although, as Isager 1993: 76 acknowledges, much of our detail on Pompey’s imitation is a function of later texts. Plutarch (with hindsight, of course) offers examples of Pompey attracting mockery rather than glamor from his association with Alexander, e.g.,Pomp. 2.2; Caes. 7.1.

7 On Posidonius and Pompey see, e.g., Str. 11.1.6; Cic. Tusc. Disp. 2.61; Plin. HN 7.112.

8 For the representation of oikoumene in the Triumph in 61, see Dio 37.21.2; on Pompey as world conqueror see, e.g., Cic. Pro Sest. 129; Pro Balb. 9.16; Manilius, Astronomica 1.793; Plu. Pomp. 45.6.

9 Franklin 2003 offers a useful summary of Pompeian “ideology.”

10 Plu. Pomp. 37.3 makes Theophanes responsible for black propaganda on Pompey’s behalf. For Pompey’s self-fashioning as Alexander, see in particular Sall. Hist. 3.88M. Green 1989b: 291 n. 40 provides a range of references. Pompey’s entourage included Theophanes, Lenaeus (a Greek freedman and rhetorician), and the antiquarian and polymath Varro, and he also seems to have kept up contact with Posidonius (an influential Stoic philosopher and historian from Rhodes, with interests in political theory). On the significance of exploration and science as Pompeian themes in general, see e.g., Plin. HN 6.51–2, 12.20, 12.111. On Lenaeus’ study of Mithridates’ medical texts see, e.g., Plin. HN 25.5. On Theophanes see, e.g., Cic. Pro Arch. 24; Str. 11.2.2, 11.4.2, 11.5.1, 11.14.4, 11.14.11; Plu. Pomp. 35, 36; a connection between Pompey and Theophanes is discussed by Gold 1985.

11 For Pompeiopolis, see Str. 8.7.5; Plu. Pomp. 28; Dio 36.37.6; App. BM 115. Cf., e.g., Arr. 5.29; D.S. 17.95.1 for parallelism with Alexander. On his theater, see Plin. HN 36.41; Suet. Ner. 46.1. For imagery of world mastery in connection with Pompey and Caesar, see Weinstock 1971: 50–3.

12 See, e.g., Plin. HN 7.95, 7.97; Sall. Hist. 3.88M; Cic. Ad Att. 2.13.2; Plu. Pomp. 2.2.

13 Appian (BM 117) and Zanker (1988: 10) certainly want to believe it. See Dio. 59.17.3 and Suet. Calig. 52 on Caligula and Alexander’s breastplate.

14 For accounts of the Triumph see, e.g., Plin. HN 8.4; Plu. Pomp. 14.6.

15 Green (1989a: 198) is hugely doubtful that Pompey’s botched Alexandrophilia would have made the Macedonian an attractive model for Caesar, but I suspect that synchronicity between Pompey and Caesar and Pompey’s (ultimate) failure may have made outdoing Pompey/Alexander even more (rather than less) attractive.

16 The nickname “Moneybags” (Diues) that Crassus acquired is rather less alluring than Pompey’s “Great.” It is interesting that, rather than gaining a tag, “Caesar” instead becomes one in the principate (and after).

17 Comparisons with Rome’s catastrophic defeat by Hannibal at Cannae may not be too far from the mark, as suggested later in Hor. Carm. 3.5. Eventually, Augustus managed to negotiate their return, and the standards were lodged in the temple of Mars Ultor in the Forum Augustum at Rome in 2 BC.

18 Appian (BC 2.149), e.g., includes what seems to be Callisthenes’ story of Alexander’s “miraculous” passage along the coast beneath Mt. Climax in Pamphylia (FGrH 124 F31; Arr. 1.26.1–2; Plu. Alex. 17.3–5) in his comparison of Alexander and Caesar. As noted above, this story gets attached to Scipio at his successful siege of New Carthage. Cf. Cicero (De imp. Cn. Pompei 10.28; 16.47, 48) on Pompey, and the need for a general to have felicitas. Weinstock 1971 draws together a vast array of associations with Alexander that color Caesar’s progress to deification (although his encyclopedic tendencies lead to some uncritical readings). Wiseman 1974 and Zanker 1988: 5–25 offer important discussions of late republican aristocratic self-aggrandizement.

19 Plutarch tells us that Caesar studied Alexander’s campaigns (Caes. 11), while speed forms an important narrative strand in Curtius’ Alexander (e.g., 4.4.1–2; 5.1.36). Appian makes a direct com¬parison (2.21.149–54), as does Velleius (2.41.1). Strabo, writing under Augustus tells us that Caesar was philalexandros (13.1.27).

20 Green 1989a: 195: Suet. Iul. 7; cf. Plu. Caes. 11.

21 Cic. Ad Att. 12.40.1–2, 13.26.2, 13.27.1, 13.28.1–3. Weinstock 1971: 188 thinks (ex silentio) that Caesar himself may have “suggested” the comparison to Cicero; Green 1989a: 205 dismisses this. Spencer 2002: 57, 61–3 discusses these letters.

22 On the role of clementia in modeling Roman Alexanders, see Spencer 2002: 170–5, 229 n. 20. On clementia and Cicero’s Pro Marcello, see Spencer 2002: 58–61.

23 On imperial virtues, see Fears 1981.

24 Useful texts are referenced by Wirszubski 1960, esp. 52, 62, 103–5.

25 Caesar’s changing image (and detailed references to texts) is summarized by Gelzer 1968: 278–9, 308–9, 315–23. Weinstock 1971: 188–9 locates Caesar’s use of the red boots of the Alban kings very explicitly in Alexander’s shadow, linking this to problems associated with Alexander’s “Medizing” changes of dress. On the significance of genealogies, mythical and otherwise, in late republican image- making, see Wiseman 1974.

26 See, e.g., App. BC 2.106–9; Suet. Iul. 76, 79; Plu. Caes. 61. Despite Pompey’s successful post-Sullan reinvention of Venus as his protector, Caesar’s explicit annexation of her as his ancestor raised far more disturbing implications. Suddenly, this was more than divine favor for an individual/family, it implied a divine plan which raised the Julii far above fellow citizens, and raised the specter of hereditary power monopolized by one family, whose success was integral to the prosperity and destiny of Rome itself. Green 1989a: 206–7 succinctly (if dismissively) summarizes what he terms “the dim area of merely circumstantial evidence” on Alexander and Caesar (206). Although the textual evidence is complex and at times contradictory, Wiseman 1974 introduces a persuasive vision of a Rome in which vying for famous “ancestors” was almost a commonplace, against which backdrop annexation of Alexander – in particular, a deified Alexander – seems highly likely.

27 Cicero’s Philippics and Antony’s De ebrietate sua are the most obvious examples, but a storied charade in which Octavian hosted a “banquet” of the Olympian gods (with himself as Apollo) also crops up (see Suet. Aug. 70). On this in particular, see Gurval 1995: 94–8; his account of Antonian propaganda (1995: 92–3) is useful, and should be read in conjunction with Scott 1929 and 1933; Huzar 1978: 233–52; Zanker 1988: 57–65; and Ramsey 2001. Pollini 1990 and Gurval 1995 take an alternative approach to Zanker on pre-Actian propaganda, playing down the likelihood of Octavian partaking even semi-publicly in tropes of deification. On changes in Octavianic coinage, see Zanker 1988: 53–7 and Gurval 1995: 52–65. Despite all this, Cicero’s understanding of Alexander is still double-edged enough to allow him to figure early on in the struggle as a positive example for giving power to the young Octavian (Phil. 5.17.48).

28 Antony and Cleopatra’s daughter, named Cleopatra Selene, continues the theme. On stars and Sol/Helios in connection with Caesar, Weinstock 1971: 370–84 provides a clear overview; cf. Gurval 1996 on the sidus Iulium and Augustus.

29 On Alexander in this epistle, see Spencer 2002: 91–3.

30 On Alexander, degeneracy, and Antony, see Spencer 2002: 193–5, and more generally on the years after 44, Zanker 1988: 33–77.

31 On the “east” and the “other,” see Romm 1992 and Evans 2003. On receptions of Hercules, see Anderson 1928 and Galinsky 1972.

32 Hercules’ enslavement by Omphale was easily rewritable as Antony and Cleopatra. We see echoes of Alexander’s (and Antony’s) problematization of Hercules in Commodus’ claims to be him, and, indeed to refound Rome as colonia Commodiana in the AD190s. Dionysus’ role as a civilizing imperialist could be countered with the asocial and wilderness associations of his cult and worship. Seneca, Ep. 83 is particularly interesting in this respect, since it tacitly acknowledges the tension between the sacral and “truth-telling” connotations of wine, and its dangerous, boundary-breaking effects (see Spencer 2006b). Cf. the elder Pliny on Pompey and Alexander (HN 7.95). Gurval 1995: 189–208 focuses on the implications of the propagandist battle of Actium. Kienast 1969: 441–5 discusses Antony’s dynasticism in terms of Alexander.

33 Examples of parallelism involving divine mimesis include Verg. Aen. 8.678–713 and Prop. 4.6. Gurval’s (1995: 98–131) discussion of Apollo and Augustus is comprehensive, and he also offers an interesting reading of Prop. 4.6.

34 Dio 51.16.3–5 recounts the story of Octavian’s explanation of why he spared Alexandria, and his trip to Alexander’s tomb. Cf. Suet. Aug. 18.1.

35 See Spencer 2002: 41–53 on Livy’s Alexander (9.18); see also Morello 2002 on the rhetoric of the extract.

36 Kienast 1969: 432–43 and Eder 1990: 89–101 offer useful readings of how Alexander-Augustus comparisons work (see the more expansive overview in Garcia Moreno 1990). After AD 20 Alexander slips out of focus (with the exception of allusions such as Virgil’s (above) and, e.g., Hor.Carm. 2.1.232¬44) until he briefly recurs in the iconography and rhetoric surrounding the dedication of the temple of Mars Ultor (2 BC), in which the standards recovered from the Parthians were lodged, and Gaius Caesar’s Parthian mission in 1. See Spencer 2002: 191 and Isager 1993: 79.

37 Tac. Ann. 2.72–3, 82–3. On the importance of horsey connections at Rome, see Spencer 2007. Statius’ commemoration of Domitian’s big horse is discussed below.

38 E.g., Vell. Pat. 2.129; Suet. Tib. 52. For an overview of Alexander in the Annals, with particular emphasis on Germanicus and Corbulo, see Spencer 2002: 191–3, 199–200; and on Germanicus and mutiny 202–3. Malissard 1990 is particularly good on Tacitus’ “eulogy” of Germanicus. See also Aalders 1961; Shotter 1968; Ross 1973; Rutland 1987; Pelling 1993; Gissel 2001.

39 A useful comparative for Tacitus’ account is Q. Curtius Rufus’ version of the aftermath of Alexander’s death (10.5.7–16), but see also Just. 13.1.1–6.

40 André 1990 provides a helpful overview of what we might term “Julio-Claudian” imitatio Alexandri.

41 Curtius’ date and identity are not securely fixed, but it is likely that he was writing in the late first century AD. His account is unique in that it provides the only (almost completely) extant treatment of Alexander in Latin. Baynham 1998a provides a full-scale discussion of his entire history of Alexander. For Curtius, Callisthenes, and Rome, see below. On Alexander’s rhetoric in Curtius’ account of the Pages’ Conspiracy, see Spencer 2002: 135–8; on Orientalism and topography in Curtius, see Spencer 2005b.

42 For the Triumph and breastplate, see Suet. Calig. 52.3; Dio 59.17.3. Isager 1993: 81 takes this as a record of actual imitatio Alexandri on Caligula’s part, but I think it is more indicative of how deeply embedded Alexander had become in Roman political consciousness. It would be almost impossible to conceptualize ways of characterizing a mad, bad ruler without dipping into tropes recalling Alexander.

43 On Corbulo and Nero, see Spencer 2002: 199–200 (including bibliographical references). The accounts of Tacitus and Cassius Dio are worth comparing (e.g., Tac. Ann. 13.6–7, 13.35, 14.20–2, 14.23.1; Dio 62.19.2–4, 62.23.5, 63.6.4). In Elsner and Masters 1994, the complexity of disentangling the historical Nero from the monster is addressed.

44 On Nero’s philhellenism, see Alcock 1994.

45 Isager 1993: 82. Too 1994 discusses the complex didactic between Nero and Seneca in the epistulae morales. On a range of Senecan passages, see also Spencer 2002: 69–79, 89–94, 97–112. On Ep. 83 in particular, see Spencer 2006b.

46 See Isager 1993: 83. But Isager is vastly overstating the case when he says, conclusively, that after Nero “the model of Alexander seems so abused and emptied of positive connotations that we find no comparison between Alexander and Vespasian.” Surely the dark side of Alexander, that which ought not to be invoked, is ever present in the kinds of things which are not said about Vespasian?

47 On these two poems, see Spencer 2002: 151–4, 184–7 (discussed with Vell. Pat. 1.11.2–5 on the Granicus sculpture group) and Newlands 2002: 46–87.

48 See, e.g., Curt. 4.7.30–1; 8.7.1, 14. Domitian, unsurprisingly, did not die peacefully. He was stabbed to death by a group of conspirators who included his wife, Domitia, and the next emperor, Nerva.

49 Alexander figures as an ineffectual ghost – Sil. Pun. 13.762–76, likely to have been composed before Domitian’s death in AD 96. See Spencer 2002: 162–3.

50 On Lucan’s configuration of Rome’s Mediterranean as a toxically historical theme park, where playing at Troy, Alexander, or even Caesar is all that is left, see Spencer 2005a. We can look forward, eventually, to Caracalla’s sepulchral tourism in Alexandria, as recounted by Dio (78.7.2).

51 Useful biographies of Trajan and Hadrian are Bennett 2001 and Birley 1997.

52 As Zecchini 1984: 197–9 observes.

53 On Trajan and Alexander as fellow conquerors see, e.g., Bennett 2001: 189, 198, 199. A coda to the lure of Alexander’s footsteps can be found in Caracalla’s restless and relentless warfare (AD 213–17), conducted ostentatiously in the wake of Alexander’s trajectory. Historical irony makes it inevitable that, granted the titles Germanicus Maximus and Parthicus Maximus, he comes to a sticky end. That he met it at the hands of one of the Praetorians, near Carrhae, scene of Crassus’ debacle (and the explicit trigger for Rome’s Parthian complex), is particularly apt. Connections between M. Aurelius Antoninus (as he was officially styled, although he had himself called Elagabalus (Heliogabalus), named for the Emesan mountain and sun god), Severus Alexander and Alexander (the Great) focus first on deification and its disastrous consequences, and then imperialism. Severus failed to measure up to Artaxerxes (king of Persia from AD 227). He was eventually assassinated by mutineers in Germany (AD 235). The Scriptores historiae Augustae are particularly eager to play up associations.

54 As Waldemar Heckel has pointed out, the historic Callisthenes cannot have played a part in the fullest development of the Alexander-Achilles comparison – his death before that of Hephaestion rules him out of a direct involvement in creating the parallels between Hephaestion and Patroclus that vividly color accounts of Alexander’s response to the loss of his friend. We might also wonder how much of the scenario at Troy, before Achilles’ tomb, is a retrospectively applied topos.

55 Cic. Pro Arch. 24. For a more extended discussion, see Spencer 2002: 122–4. It is ironic that Pom- pey’s promotion of Theophanes ultimately led to his posthumous deification (as Zeus Eleutherios Theophanes) at Mytilene. We can assume that Cicero did not envisage the historian out-Alexandering his subject in quite such a dramatic way!

56 It is intriguing to note that Cicero also contacted Posidonius (60 BC), in effect triangulating the relationship with Pompey, asking him to polish up his own account of the Catilinarian conspiracy (Ad Att. 2.1.2).

57 On what it means to have “the Great” tagged after one’s name, see Spencer 2002: 2–5.

58 The elder Seneca (c.50 BC-C. AD 40) was a historian and rhetorician, originally from Corduba in Spain.

59 E.g., Curt. 8.5.13–20.

60 See Spencer 2002: 94–7 (on Curt. 6.2.1–5); and on this, in general, 178, 189–90, 194; also Baynham 1998a: 71–2 (Callisthenes as an Alexander historian), 51–2 (on the Pages’ Conspiracy), 192–5 (on Callisthenes’ resistance to proskynesis).

61 On Callisthenes’ downfall: Curt. 8.5.5–8.23. For a range of versions of the proskynesis story, see Arr. 4.10.5–12; Curt. 8.5.5–21; Just. 12.7.1–3; Val. Max. 7.2 ext. 11. In the wake of Augustus’ and subsequent deifications this story takes on the most urgent political and ethical implications for a Roman audience, and Romans will, no doubt, have expected accounts of Alexander to take a position on this event and its aftermath.

62 See, e.g., Curt. 6.6.2, 9; 8.5.5; 8.7.13–14; Just. 11.11; also Spencer 2002: 178. It is interesting that the accounts of Arrian and Plutarch (e.g., Arr. 4.12.7, 4.14.1; Plu. Alex. 55.4–5) are far more ambivalent about the role of Callisthenes in his own downfall. On narratological complexity in Curtius’ portrait of Callisthenes, see Spencer 2002: 136–7.

63 His sons were Seneca (known as the Younger, who went on to become tutor and then adviser to Nero), and M. Annaeus Mela, father of the poet Lucan. Like his uncle Seneca, Lucan came to grief under Nero despite what seems at first to have been a close relationship; both committed suicide in AD 65. Typically, suasoriae positioned their speakers in the realms of familiar and popular insoluble dilem¬mas, giving them an opportunity to cut their teeth on persuasive and advisory rhetoric in a notionally “safe” political and pop-cultural framework.

64 See Griffin 1992: 33.

65 Seneca the Younger’s comment that all Alexander’s achievements were pointless in the wake of his murder of Callisthenes is particularly poignant in the light of Nero’s role in his death (NQ 6.23.3; concluding: nihil tam mannum erit quam scelus” – there will be nothing in which [Alexander] is great, other than villainy).

66 On Alexander and the power play involved in advisory rhetoric, discussed in relation to Seneca and Cicero, see Spencer 2006b.

67 Vitruvius prospered as an architect (and engineer) for Caesar, but is most famous for his De archi- tectura (dedicated to Octavian). This work nods to the Hellenistic trend to compose philosophically and theoretically engaged humane “handbooks” that offer aids to conceptual understanding of practical topics. Strabo’s Geographia (probably composed under Augustus and Tiberius) is particularly inter¬ested in the ethical implications of landscape and the relationship between landscapes and empires. The elder Pliny owed much of his political success to the Flavians. He wrote extensively on a diverse range of topics, but of particular interest here is his Naturalis historia.

68 See also, e.g., Sen. QNat 3 pr. 5; 5.18.10–12. As Lassandro 1984: 162 observes, Alexander’s appear¬ance at QNat 6.23.3 is an extremely rare occurrence of Seneca using the QNat as a vehicle for authorial comment. For an overview of the kinds of Alexander narratives that all these authors might have had access to, see Atkinson 2000b and Baynham 2003. On natural history, see French 1994.

69 Other instances of Strabo’s obsessive cataloging of Alexander as subject and inquirer into natural history include 14.3.9 (the tides at Mt. Climax), 15.1.25 (the “wrong” Nile), 15.1.29 (from “wild” nature to Bucephalus), 15.1.31 (dogs), 15.1.35 (the Ganges), 16.1.9 (destruction of the artificial cataracts on the Euphrates), 16.1.11 (general interest in water management), 16.1.15 (experiments with naphtha).

70 This rather terse survey is only a sample of Alexander’s ubiquity in Strabo, and of particular impor¬tance is his appearance at 15.1.26 (in the wake of Strabo’s programmatic comments at 15.1.2–10).

71 E.g., Plin. HN 3.20 (a record of the peoples conquered by Rome, listed on a triumphal arch), 6.31 (Augustus’ intelligence operations against Armenia), 6.35, 12.8 (Nero’s exploratory foray into Ethio¬pia), 5.1 (strategic survey of the transalpine region), 6.35 (Juba’s fact-finding impulses). This trend comes to its logical conclusion in the mid second century AD with Greek-speaking Aelius Aristides’ summation of the whole world as a single city, Rome (Oration 26, “Regarding Rome”; e.g., 6, 8, 11, 63, 102; Alexander figures particularly at Oration 26.24–8). On Aristides’ place in modeling Antonine Alexanders see Zecchini 1984: 199–204.

72 Pompey’s Magnus, Pliny tells us, was the spolia (booty) he received on conquering the whole of Africa.

73 See, e.g., HN 6.31 on the stranded “Alexandria,” abandoned by the sea.

74 Other significant examples of Alexander’s importance for the world according to Pliny can be found at HN 35.93–4 (Apelles in the temple of Mars Ultor), 8.44 (Alexander commissions a natural history of all animal life, from Aristotle), 8.149–50 (Alexander discovering a breed of hunting dog which will attack nothing more humble than lions or elephants), 6.61 (in order to understand India one must follow in the footsteps (uestigia) of Alexander).