When Blackwell’s Al Bertrand first suggested that I edit a volume of new papers on Alexander the Great, it was believed that a “Guide” or “Companion” to the study of the famous conqueror would serve as a useful background for readers attracted to the subject by the appearance of Oliver Stone’s film Alexander. For once, my habitual lethargy proved beneficial; for the anticipated triumph of Stone’s epic never materialized – and I leave it to readers to decide for themselves why this was so. The volume’s title thus mutated intoAlexander the Great: A New History, a change that is neither subtle nor unimportant. What, one may ask, is new in this New History? Is it even possible to say anything new? Again, readers will have or at least may form their own opinions, but some observations are worth making at the outset.

First of all, this book offers a collection of views on aspects of the history and life of Alexander, as well as on the kingdom from which he emerged and the empire he conquered, by a wide range of scholars – some providing a synthesis of arguments developed over many years of engagement with the subject (or, on occasion, of “engaging the enemy more closely” – for we are not all admirers of his alleged “greatness”), others presenting fresh new approaches to topics both familiar and less so. Neither the contributors nor the editors would agree in every case (or even whole-heartedly) with the conclusions reached in some or perhaps most of the chapters in this book, but all will recognize that the arguments presented here are based on reasoned interpretations of the (often complex) evidence. And it is precisely this healthy difference of opinion that keeps the study of Alexander fresh and, dare I say, new. The newness and appeal of this volume are, thus, to be found in its diversity and its combination of novel insights with breadth of coverage, of in-depth investigation with an appreciation of universal truths. The individual chapters are not intended primarily as surveys of scholarship, although they often provide this very thing; instead they offer thought-provoking insights into much discussed problems as well as new areas of study. Furthermore, I have in recent months debated with myself whether it is not somewhat disingenuous to claim as “new” contributions which in some cases have been sitting on my desk for over four years, but again the newness resides in the arguments and their presentation rather than in the speed with which they have found their way into print.

This leads me to comment briefly on the evolution of this particular volume. As I mentioned above, the proposal came originally from Al Bertrand to me, but I soon found it desirable to invite – perhaps “beg” would be the more appropriate word – my friend Larry Tritle to join me as co-editor. We commissioned articles by German, French, and Italian scholars, and the need to translate these brought with it concomitant delays in publication. When it came to contributors who wrote in English, some withdrew – reluctantly and with apologies and ample warning – and another simply did not deliver or bother to forewarn the editors or offer an excuse. Hence, a further delay. Nevertheless, the final collection vindicates the adage that “good things come to those who wait,” even when this means waiting for A New History. The volume, in its final form, combines narrative1 with special studies, background and context with specific details, and a survey of older literature with the promise of new approaches. Some contributors have examined new areas without resorting to what might be considered “trendy” or being seduced by the need to be “sexy”; nor is there an excessive use of jargon (though, in one case, I would venture to say that one man’s jargon is another woman’s precision). Others have taken traditional approaches to subjects previously neglected. And, for those with a craving for scholarship so profound that only foreign expressions will suffice to define it, this volume offers Quellenforschung, Wissenschaftsgeschichte, and Nachleben in healthy doses. The book’s range is geographically expansive and it stretches chronologically from the formative years of Persia and Macedon to the annus mirabilis, 2004, which witnessed the tragic non-event of Stone’s Alexander, the inspiration for the countless “new” volumes that sounded to publishers very much like the clinking of “money in the bank,” but proved to be nothing more than the echoing of an empty vault. Indeed, we have arrived too late to jump on the bandwagon. Just as well, for I would rather rock on my own than sink with the Stone.

WH

Works on Alexander the Great, his life and times, his military achievements, are legion – scholarly, popular, military, and most recently cinematographic – and all this points to the ongoing interest in one of the ancient world’s great figures, perhaps the greatest. All of this might prompt the question, What more could be said, can anything be new? The answer to this must be yes, as scholars and authors continually respond to Alexander from the perspective of their own time.

I

In the early modern era, Alexander was a subject of interest to many authors as well as translators. Niccolò Machiavelli in The Prince refers to the Macedonian king and conqueror, titling one chapter (4) after him and elsewhere citing his generosity while also referring to his imitation of Achilles just as Caesar would imitate him.2 The earliest translations of Plutarch’s Lives including the Alexander, began in the sixteenth century, first into Latin (e.g., Politan, Melanchthon, on the continent; in England Sir John Cheke and Richard Pace) and then followed not long after by vernacular translations in virtually all the major European languages. Of these those of Jacques Amyot in France and Thomas North in England were perhaps most important as they made available as never before the life of Alexander, whose achievements would inspire others to great deeds.3At the same time, additional historical accounts, particularly those of Quintus Curtius (1470/1) and Arrian (1535) provided even more information which stimulated further the study of Alexander’s life and achievements.4

The first detailed and modern scholarly treatment of Alexander appeared with the 1833 publication of Gustav Droysen’s study of Alexander.5 Droysen continued revisions to this work through the nineteenth century, and to the present day it is widely regarded that he not only single-handedly revolutionized the study of Alexander, but in doing so created a whole new field of ancient history, the Age of Hellenistic.6 This view is now in need of revision, as Pierre Briant convincingly demonstrates in the pages that follow. A few years later in England, banker and parliamentarian George Grote began to publish A History of Greece in 1846, a work that concluded with an entire volume on Alexander that continues to be cited today.7 Though a pronounced contemporary liberal temper and middle-class ethic characterizes his work, Grote weighs the evidence of the ancient authors carefully and his judgments are generally judicious.

Since Droysen and Grote, their many contemporaries and students, research into Alexander has continued to explore the king’s life and times, going beyond the mere military achievement and finding whole new subjects to consider. In the English-speaking world, scholars including E. Badian, A. B. Bosworth, E. D. Carney, P. Green, N. G. L. Hammond, W. Heckel, and W. W. Tarn have made numerous contributions to this investigation, as have P. Briant and P. Goukowsky (in French), H. Berve, F. Schachermeyr, U. Wilcken, and G. Wirth (in German).8 The present collection of essays offers both a broad survey of the reign and conquests of Alexander, Greeks and Persians, as well as focused studies of his life and impact on those who followed.

II

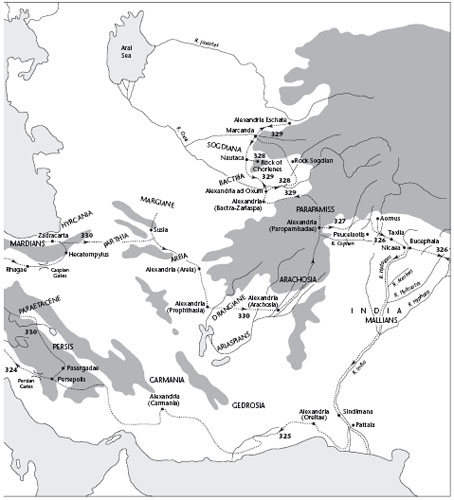

We begin with the background of ancient Macedonia and Greece, and its world well beyond Alexander’s life and reign. The historical narrative of Michael Zahrnt, Waldemar Heckel, and Patrick Wheatley examines the formation of the Macedonian kingdom under Philip and his immediate predecessors (Zahrnt), the conquests of Alexander (Heckel), and the Hellenistic world of Alexander’s successors, the Diadochi (Wheatley). The story of Alexander’s battles and conquests has certainly been told many times, but Heckel’s narrative is at once familiar yet also refreshing and insightful. Alexander’s death in Babylon led to a tumultuous and violent era that is often so confusing to students that it is dismissed as simply beyond comprehension. Pat Wheatley provides a concise discussion of this immensely difficult subject. He manages at the same time to give an overview of the sources for this period, including recent scholarly work on long neglected sources from the Near East that shed light on the notoriously difficult chronology of the period. New ideas of kingship that formed at this time are also examined.

Alexander could have accomplished nothing without one of the great armies of all time, and Waldemar Heckel, in a second essay, and Gregor Weber offer stimulating treatments of Alexander, his army, and court. Exploring the nature of the army – where its men came from and also the relationship between commander and commanded – Heckel offers an interpretation of Alexander’s leadership and command abilities that readers will find stimulating and provocative. Alexander also inherited a court from his father Philip, and Weber shows how, during the course of his reign and conquest, this court changed along with the king. Persian institutions as well as representation entered the Macedonian court, making it different. The court also became permanent as the source of power of a monarch who is at once Greek and Macedonian as he is also Persian.

Alexander inherited not only his kingdom from his father but also a complex web of connections to the Greeks whom Philip had defeated at Chaeroneia in 338/7.

These relationships are examined by Elisabetta Poddighe and Lawrence Tritle, looking at two very different dimensions of these. As Philip planned his attack on the Persian empire, he established an alliance and league, what we now know as the Corinthian League, to create stability and order in Greece while campaigning. Leadership of this fell to Alexander, inheriting his father’s title as hegemon. Pod-dighe examines the sometimes sensitive dealings between king and League, arguing that Alexander mostly maintained a diplomatically proper relationship with the Greeks. This changed somewhat upon his return to Babylon in 324, especially for Athens which disputed the king’s call for “freedom” in Greece which for Athens meant loss of the island of Samos as its exiled population would now return home. Not all Greeks, however, saw Alexander and the Macedonians as oppressors. Many, thousands even, benefited and profited from Alexander and the Macedonian conquests, and participated in the great adventure into the Persian east, joining Alexander as soldiers and bureaucrats, artists and entertainers, of all kinds. Tritle identifies these, discussing and analyzing their associations with Alexander and his army.

The Persians, of course, suffered defeat and ignominy at Alexander’s hands. Pierre Briant sheds light on this defeat, first looking at the state of affairs in the empire as Alexander invaded, then turns to history of the history of Alexander’s Persian conquest. R. G. Collingwood in his Idea of History (1946) discussed what he called “second order history,” or the history of history, and how present ideas shaped understanding of the past. In a penetrating study, Briant traces the origins of many of the ideas common to Alexander studies, placing them within the context of European intellectual history from before the Enlightenment to the twentieth century.

Conquering an empire is the work of great men, and few compare with Alexander. But what kind of a man was he? Three essays examine Alexander’s family life and his transition from man to virtually godlike stature. Elizabeth Carney and Daniel Ogden look at the man Alexander, but from very different perspectives. Carney investigates Alexander’s relations with his mother Olympias and her formative influences upon him. Slightly different is Ogden’s approach, which examines Alexander’s sexuality, placing it in the wider context of what sex in the ancient world was all about and what it would have meant to Alexander. Whatever one might say of Alexander’s relationship with his mother and with men and women, there is certainty in his heroics on the battlefield and in his conquests. These clearly set him apart from those around him and during his reign and conquests his heroic stature grew by leaps and bounds. Along with this rise in his larger-than-life status, there came to be established in his honor, and to enable his rule over those he conquered, many cults and festivals throughout the lands he touched. Boris Dreyer traces the evolution of the man to demigod status, and the establishment of his cults and festivals, many of which continued to be observed for hundreds of years after his death and those of his successors.

This heroic stature survives into our own time. The impact and tradition of Alexander into later times is the subject of four essays by Alexander Meeus, Diana Spencer, Catie Mihalopoulos, and Elizabeth Baynham, all examining later images of Alexander. Meeus begins with a stimulating reinterpretation of the image of Alexander that was already taking shape in the era of the Successors. This continued, as Spencer shows, with the Romans who were at once appalled and amazed at what Alexander had achieved. Best known perhaps is the famous antagonist of Julius Caesar, Pompey “the Great” who styled himself after Alexander as seen in his portrait and in literature, particularly Plutarch’s Life of Pompey. On a much broader level, Mihalopoulos investigates Alexander’s impact on portraiture and what would become known as Hellenistic art as seen the surviving body of Greek originals and Roman copies. Finally, the Romans were just the beginning of later generations’ fascination with Alexander. Alexander’s accomplishments and person, Baynham shows, influenced the art and court of Louis XIV as seen in the famous paintings of Charles LeBrun which the Sun King commissioned. No less influential is the powerful allure of Alexander in modern film. The interpretation of Alexander screened by Oliver Stone early in the twenty-first century, despite its commercial failure, makes plain not only the ongoing public interest in history and one of its biggest stars, but also the constant presence of the past.9

LAT

1 I would acknowledge, without a twinge of guilt, that my own contribution to the narrative section is the least new, being in fact a very slight reworking (by prearrangement with the publisher) of my contribution to K. Kinzl (ed.), A Companion to the Classical Greek World (Oxford: Blackwell, 2006).

2 Machiavelli 1992: 12, 42, 45. Written in 1513 and published (officially) in 1532, Machiavelli’s source for Alexander was the recently printed text of Q. Curtius (see below n. 3).

3 On the translations and their publication see Russell 1973: 147–52. For detailed commentary to Plutarch’s Alexander see Hamilton 1969. An accessible edition of Plutarch’s Alexander (and related texts) is Scott-Kilvert 1973.

4 Curtius: first edition is that of Spirensis (1470/1), possibly that which Machiavelli read for his references to Alexander in The Prince (see Whitfield in Machiavelli 1992: 198); many editions followed including those of Hedicke 1931 and Rolfe 1946, the latter with English translation. See also the English translation of Yardley and Heckel 1984. Arrian: first edition is that of Trincavalius (1535); many editions followed, including those of Roos and Wirth 1967–80 and Brunt 1976–83 (with English translation). Another readily available English translation of Arrian is de Selincourt 1971.

5 Readers might consult the introductions of Bosworth and Baynham 2000 and Bosworth 2002 which summarize the nature of the evidence for the study of Alexander and provide a historical overview. Cf. Roisman 2003a which offers neither.

6 Droysen 1833, 1877. In this newly created field of Hellenistic civilization, see especially the work of Rostovtzeff 1941 and Green 1990.

7 Grote 1846–56; citation is usually made from the 1888 “new” edn.

8 Readers can find references to the works of these scholars in the bibliography to this book.

9 While Oliver Stone’s film may be deserving of criticism, its depictions of the Macedonian phalanx and cavalry deploying at Gaugamela, the drunken brawl that cost Cleitus the Black his life at Alexander’s hands, are exemplary. This is in contrast to the 1956 film Alexander the Great, starring Richard Burton.