1

Michael Zahrnt

“No Alexander if not for Philip” is true in more than just biological terms. Alexander’s triumphant conquests would not have been possible without Philip’s achievements, namely, the enormous expansion and consolidation of the Macedonian kingdom, with the removal of any danger posed by the Greek states or neighboring barbarians, and the development of an army ready to strike and a capable and loyal officer corps.1 But Philip did not create Macedonia from nothing, despite what ancient authors and modern scholars suggest: he inherited a kingdom which while it had experienced many ups and downs over three centuries had always survived and – given stable internal affairs and favorable external circumstances – represented a power that was recognized and at times even courted by others.2

It all started from small beginnings around the middle of the seventh century, south of that part of the Thermaic Gulf which in those days extended far west inland.3 There, on both sides of the Haliacmon, lay a region called Makedonis and within it – on the northern slopes of the Pierian mountains – the original Macedonian capital Aegae. It was from here that the Macedonians conquered Pieria, the coastal plain east of the Pierian mountains and the Olympus, as well as Bottiaea, the region extending west and north of the Thermaic Gulf up to the Axius, with the future capital Pella. Next they crossed the Axius and occupied the plain between this river and present-day Thessaloniki. Thus they established control over the whole area around the Gulf and finally, just before the end of the sixth century, they also took over the regions of Eordaea and Almopia which bordered the central plain on the western and northwestern sides. The capture of Eordaea, beyond the mountain ridge sealing off the plain to the west, allowed the Macedonian kings to reach further into upper Macedonia, where the regions of Lyncus, Orestis, and Elimeia lay, enclosed by mountains and with their own rulers, whose adherence to the Macedonian kingdom was dependent on the strength of its central rule at any one time. It is impossible now to ascertain when the Macedonian kings first approached these mountain areas, while the further expansion toward the east falls into the period after the failure of Xerxes’ campaign.

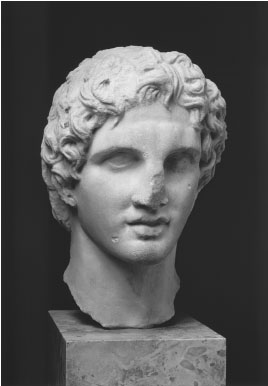

Figure 1.1 Bust of Alexander the Great, c.340–330 BC (copy?), as a youth. Acropolis Museum, Athens. Photo: Scala/Art Resource, New York.

The early days of Macedonian history are obscure. The first certain reports relate to the time of Persian rule on European soil: around 510 the Persian general Megabazus conquered the area along the northern coast of the Aegean and accepted the surrender of the Macedonian king Amyntas I. During the Ionian Revolt the Macedonians too shook off Persian sovereignty, which was restored as early as 492. Amyntas’ son Alexander I therefore participated in Xerxes’ campaign as a subject of the Great King.4 Immediately after the Persian defeat at Plataea, Alexander defected and took possession of the regions of Anthemus, Mygdonia, Crestonia, and Bisaltia which lay between the Axius and Strymon. However, in the final years of his reign he sustained losses on the western banks of the Strymon. His successor, Perdiccas II, who ruled until 413, was not only unable to reverse the losses in the east but also had to contend with the endeavors of the rulers of upper Macedonia to establish independence. Moreover, in his time Macedonia was impeded by the Athenian naval empire and drawn into the conflicts of the Peloponnesian War. But Perdiccas was able to maneuver a way through the warring factions fairly successfully and thus for the most part to maintain the independence of his kingdom.

His son Archelaus was destined for a happier rule, since Athenian pressure had eased after the Sicilian disaster. Relations with the Athenians were virtually reversed as they relied on Macedonian timber for shipbuilding. Archelaus’ real contributions lay in domestic politics, his cultural efforts and military reforms. Not only did he accelerate the extension of the road network, but he also initiated the development of a heavily armed infantry which, as shown by the events of the Peloponnesian War, was yet lacking in Macedonia. In the final years of his rule Archelaus was able even to intervene in Thessaly in favor of the imperiled noble family of the Aleuadae, to gain territory and secure his influence in Larisa.5 The right conditions for further extending Macedonian control were therefore in place when Archelaus was murdered in 399.

“Macedonian kings tended to die with their boots on”6 – and indeed the years from 399 to 359 were marked by turmoil and disputed successions during which the position that Macedonia had gained under Archelaus could not be retained. It was only in the latter half of these forty years that Macedonia was once more strengthened internally and enjoyed a degree of external authority, and we shall see when and why this became possible.

However, before that period, the Macedonians saw no fewer than four rulers within the six years, of whom we know little except that most of them came to a violent end and that the kingdom lost territories under them, at least in the east. We can picture Macedonia’s troubles more clearly in the first years of the rule of Amyntas III, who ascended the throne in 393.7 Soon after, Amyntas came under threat from the Illyrians and entered into a defensive alliance with the Chalcidian League which had become an important power on the north coast of the Aegean; he paid for this by ceding the Anthemus, the fertile valley southeast of present-day Thessaloniki. This alliance, however, did not save him from being temporarily expelled from his country. Only in the second half of the 380s was Amyntas secure enough to reclaim from the Chalcidians the land that he had ceded. Not only did they refuse to return it, but they for their part intervened in Macedonian affairs and forced Amyntas to turn to the Spartans who sent an army north in 382. The Olynthian War which began thus was, according to Xenophon’s report, fought mainly by the Spartans and their allies. The Macedonians did not contribute any military force worth mentioning, although Derdas, ruler of the Elimeia, and his cavalry provided useful support. Derdas and his territory are portrayed as being independent of the Macedonian king, and the other upper Macedonian kingdoms appear to have broken away at that time. In 379 the Chalcidian League was dissolved. Amyntas regained the Anthemus, but, according to Xenophon, the Spartans did little otherwise to strengthen the rule of the Macedonian king.8

Isocrates, a slightly older contemporary of Xenophon, however, took quite a different view. In his Panegyricus, published in 380, he castigates Spartan politics of the time with harsh words, introducing as one example among others that the Spartans had helped to extend the rule of the Macedonian king Amyntas, the Sicilian tyrant Dionysius, and the Great King (126). If Isocrates wished to remain credible in his condemnation of Spartan politics, he could not have included a completely insignificant Macedonian king in his trio of those then in power on the boundaries of the world of the Greek poleis. Therefore in 380 Amyntas must have been a political power not to be despised, even if in previous years he had suffered domestic and external problems. Isocrates also had something to say about this when he published his Archidamus in the 360s. Here Amyntas serves as a perfect example of what can be achieved by sheer determination: after he had been vanquished by his barbarian neighbors and robbed of all Macedonia, he regained his whole realm within three months and ruled without interruption into ripe old age (46). Isocrates could make such an assertion only if Amyntas was recognized as a ruler to be reckoned with even after his death.

In the context of a trial in 343, the Athenian Aeschines similarly identifies Amyntas as a political figure of some significance, when he records that Amyntas had been represented by a delegate at a Panhellenic congress (of which there were three between 375 and 371) but had full power over that delegate’s vote (2.32). According to this, Amyntas III was regarded as a full member of the community of Greek states at least toward the end of the 370s. The Athenians had already regarded him as such a little earlier in the 370s when they entered into an alliance with him (SIG3 157; Tod 129), the details of which unfortunately are not known, but which was probably connected to the expansion of Athenian naval power at the time. We know that in the year 375 the ship timber required came from Macedonia (Xen. Hell. 6.1.11). Macedonian ship timber was clearly once more in demand, and therefore the initiative to reach an agreement is likely to have come from the Athenians. In any case this agreement provides additional evidence that Macedonia had again joined the circle of states able to pursue their own policies.

Amyntas’ son Philip II is unwittingly responsible for the negative picture which both later sources and modern scholars have painted of him. In fact, Philip not only eclipsed the achievements of his predecessors, but also induced contemporary writers such as Theopompus, and later universal historians like Diodorus and modern historians, to portray him as almost the god-sent savior of a Macedonia sunk into chaos. Amyntas, with his stamina and energy, had already slowly overcome the disorder following Archelaus’ murder, although he also benefited from the shifts in power around Macedonia, and he left his sons a fairly well-secured kingdom when he died in 370/69.

The general state of affairs remained essentially favorable to the further rise of Macedonian power for his successors. But inner stability and continuity in the succession were needed as well as favorable external conditions. That it had taken Amyntas more than ten years to rebuild the kingdom, and that previously six years of disputes over the succession had been sufficient to bring Macedonia to the brink of disaster, show how quickly what had been achieved could be jeopardized. However, at this point a period of internal turmoil and struggle for the throne, as well of major external interference, soon commenced once more.

The succession of 370/69 went smoothly: Alexander II, the eldest son from Amyntas’ marriage to Eurydice, came to the throne, which in itself shows that Amyntas had again established order. The Illyrians, however, were of a different mind and invaded Macedonia. Pausanias, a relation of the ruling house who lived in exile, used the resulting absence of the young king to invade the country from the east. In this predicament the king’s mother Eurydice turned to the Athenian general Iphicrates who had been dispatched to win back Amphipolis and asked him for help. Iphicrates, gladly taking the opportunity to place the Macedonian king under an obligation, succeeded in expelling Pausanias.9

With this Alexander’s rule was secured, particularly since he had managed to ward off the Illyrian threat. The young king also began to assume the external status his father had achieved in his last year of rule, for the Thessalian Aleuadae called on his support against the tyrant Alexander of Pherae. The Macedonian king appeared with his army in Larisa, was allowed to enter the town, and took the castle after a short siege. Crannon likewise fell into his hands shortly afterward. But instead of handing over the towns to the Thessalian nobility, he kept them himself and installed garrisons in them. This turn of events was not what the Thessalian nobles had expected; they therefore turned to the Thebans who sent Pelopidas to their aid. Pelopidas marched north with an army and liberated Crannon and Larisa from Macedonian rule.

In the mean time Alexander II had been forced to return to Macedonia, for his brother-in-law Ptolemaeus had risen against him. Both parties turned to Pelopidas and called on him to be the arbiter. In order to insure that his arrangements would last and to retain a bargaining tool against the Macedonian king, Pelopidas received Alexander’s youngest brother Philip and thirty sons from the leading families as hostages. Thus the position of power gained under Amyntas III and inherited by Alexander II was quickly lost again and the country once more came under the influence of the then predominant power in Greece, but this was also due to their own mistakes. The state of affairs was to continue for some time. As soon as Pelopidas departed after settling the internal dispute, Alexander II was killed in the winter of 369/8.

As one of the closest male relatives, Ptolemaeus became guardian of Perdiccas, Alexander’s younger brother, and assumed the reins of government. The friends of the murdered ruler, however, regarded him as a usurper and in the summer of 368 turned to Pelopidas, who once more entered Macedonia. Ptolemaeus was forced to declare himself ready to come to an arrangement and to undertake to safeguard the rule for Alexander’s brothers, Perdiccas and Philip. Moreover, he had to agree to an alliance with Thebes and surrender his son and fifty nobles as hostages to guarantee his loyalty. Once more Macedonia was at the mercy of external forces, and again as a result of internal turmoil.

In 365 Perdiccas III succeeded in ridding himself of his guardian Ptolemaeus. Soon after assuming his rule, he decided to make common cause with the Athenians, to work with their commander Timotheus who was operating off the Macedonian coastline, and to take joint action with him against the Chalcidians and Amphipolis. Timotheus gained Potidaea and Torone on the Chalcidian peninsula, but was unable to achieve anything against Amphipolis. Soon afterward, the Athenians sent a cleruchy to Potidaea in order to secure his new acquisition, which occupied a strategic position.

Working with Timotheus is likely to have opened the Macedonian king’s eyes to the Athenians’ political ambitions for power and their by this time very limited capabilities, and to have strengthened his self-confidence, for he soon defected from them and secured Amphipolis through a garrison. Thus Perdiccas ended up on hostile terms with both the Athenians and the Chalcidians, who were themselves also at war with each other, and Athens’ power continued to wane. Overall Macedonia was again on the rise, after the rightful ruler had assumed the throne in Perdiccas and overcome initial problems. He was now able to begin to consolidate the kingdom and to secure it externally. As part of this, he also appears to have reasserted control over the upper Macedonian kingdoms. He also resolved to stop the Illyrians, who had plagued Macedonia since the times of Amyntas III, but was at last defeated in a great battle and fell with 4,000 of his men.

In this situation Perdiccas’ brother Philip proceeded with determination, military ability, and diplomatic skill, first to stabilize Macedonia, and then to pursue a course of expansion by making the most of each opportunity as it presented itself.10He was able to eliminate the pretenders to the throne who almost always quickly appeared in Macedonia in such circumstances; his next step was to secure the borders of the kingdom and their immediate approaches. In this he benefited from the situation in Greece: the Spartans, who acted as if they had been the masters of Greece for some time and had even intervened in the years 382–379 in favor of the then Macedonian king, had been eliminated as a leading power since their defeat at Leuctra (371) and limited to the Peloponnese in their political ambitions. From 357 to 355 the Athenians were entangled in conflicts with some of their allies, and the Second Athenian Confederacy was falling apart. The Thebans’ power likewise was crumbling: where ten years earlier they had still exerted crucial influence as far as Macedonia and even on the Peloponnese, now even their attempt at chastising the insubordinate Phocians failed. Instead, these occupied the sanctuary of Delphi in the early summer of 356 and proceeded to form a large army of mercenaries with the help of its treasures and to hold their own against the other members of the Amphictyony. Finally, the situation in Thrace was also advantageous for Philip after its king Cotys, who had succeeded in reuniting the kingdom, was murdered in the summer of 360 and Thrace was broken up into three parts in the subsequent battle for the succession. Thus the 350s saw convincing successes by Philip on all borders of his kingdom.

The borders to the west and north caused the fewest problems: Philip had already marched against the Illyrians in the early summer of 358, forcing them to cede substantial territories up to Lake Ochrid. When two years later the Illyrian king allied himself with the Paeonians, Thracians, and Athenians against Philip, it was sufficient for Philip to send the experienced general Parmenion against him. After that the region was quiet for more than ten years, especially after another safeguard had been put in place toward the end of the 350s when Philip installed his brother- in-law Alexander as ruler in Epirus, turned the country into something resembling a satellite kingdom, and annexed the region of Parauaea, located between Epirus and Macedonia.11 The Paeonians, who had settled midway on either side of the Axius, were neighbors who had hoped to gain at the expense of Macedon following the defeat of Perdiccas III. At the beginning Philip induced them to maintain peace by making both payments and promises but soon after he attacked, defeated, and brought them into line. In 356 the king of the Paeonians joined the coalition (see above), and shortly afterward his country was finally subjugated.

Philip began to turn east and to round off the area under his rule along the Macedonian coastline in 357. First, he captured Amphipolis, with its deposits of precious metals and timber, which controlled both the crossing over the Strymon and access to the interior of the country, and secured his new acquisition with a garrison; soon after he attacked Pydna on the Macedonian coast. The Athenians who at that time held Pydna and laid claim to Amphipolis declared war against him, but Philip responded to this by approaching the Chalcidian League, promising to acquire for them the Athenian cleruchy of Potidaea.12 This was meant to happen in 356, but while still laying siege to the town Philip received a request for help from the Greek colony of Crenides, which lay in the hinterland of Neapolis (present-day Kavala), and which saw itself threatened by a Thracian king. Philip placed a garrison in the town which he refounded under the name of Philippi. By this he gained not only another foothold in the east, but also the opportunity to exploit the Pangaeum’s rich deposits of precious metal.13 The Thracian king in whose territory Philippi lay naturally joined the coalition, with the result that by the end of the year he was a vassal of Philip and the latter had extended his rule up to the Nestus. In the autumn of 355 Philip attacked Methone, Athens’ last remaining foothold on his shores, and succeeded in forcing it to surrender after a prolonged siege. This represented not only a material but also a public relations victory, for the Athenians had not offered the town any help even though they had the means after the Social War came to an end. As a result, Philip thought a second attempt worth his while: in the spring of 353 he was active east of the Nestus, presumably in order to harm the Greek towns along the coast that were allied to Athens and to make an impression on the Thracian king who ruled this region. The outcome of this test, which was of limited duration, appears to have satisfied Philip: in the autumn of 352 he returned to Thrace and marched rapidly in stages across the Hebrus against Cersebleptes, who ruled the most easterly of the three Thracian kingdoms, and forced him to subordinate himself as vassal. We do not know to what extent this expedition was also aimed at the Athenian territories on the Thracian Chersonese, for Philip fell ill and had to curtail the campaign.

These activities served for the most part to safeguard and expand the Macedonian kingdom and were directed against Athens only among the Greek states. However, what secured a decisive influence over central Greece for Philip occurred between the two campaigns into middle and eastern Thrace. The energetic kings among his predecessors had always pursued three aims: to subjugate the rulers of upper Macedonia; to reach the mouth of the Strymon in order to secure the Bisaltia, which was rich in precious metals, and to alleviate the possibility of Athenian pressure on the coasts of their kingdom; and to extend their influence into Thessaly. Philip achieved the first two goals relatively quickly, and even surpassed his predecessors by not only placing the upper Macedonian territories under his rule, but also pushing the western border of Macedonia up to Lake Ochrid, and by reaching not only the Strymon in the east but as far as the Nestus, and bringing the precious metal deposits of the Pangaeum and of the Bisaltia under his control. He also gave his attention to the third objective and brought his influence to bear in Thessaly.14In this he was able to exploit the tensions between the Aleuadae in Larisa and the Thessalian League on the one hand and the tyrants of Pherae on the other: a first intervention took place as early as 358 and secured the position of his newly won friends among the Thessalian nobility. Philip intervened a second time in 355 in favor of the Thessalian League and thereby made it possible for it to commence a Sacred War jointly with the Thebans against the Phocians, who by now had been in Delphi for over a year without punishment. It appears that Philip had clearly understood that getting involved in central Greece might open up an opportunity for him to gain influence by intervening personally, an influence which could then perhaps also be brought to bear against the Athenians.15

But the Sacred War came to an end in the autumn of 354. Philip saw no chance of personally intervening in it and turned against Thrace in the spring of 353. Then the hoped-for turn of events in central Greece did occur after all, in the form of an offensive by the Phocians under Onomarchus and a rekindling of the conflict between the Thessalians and the tyrants of Pherae. The latter turned to the Phocians, and the Thessalians to Philip. At first Philip experienced some success but then he suffered two defeats by Onomarchus and had to retreat to Macedonia. He returned in 352, had supreme command over the armies of the Thessalian League transferred to himself, and routed Onomarchus. Soon afterward Pherae and its port Pagasae fell; the tyrannis there came to an end. It would have been natural for Philip to use his military successes so far to legitimize his position as Thessalian supreme commander, and he therefore marched his troops against the Thermopylae which were being held by the Phocians, in order to deal a decisive blow against the temple robbers. However, this was no longer an issue which concerned only Philip, the Thessalians, and the Thebans on the one hand and the Phocians on the other. Control of the Thermopylae would have opened up the way south for the Macedonian king, and thus he found the pass occupied by troops of the Phocians, Athenians, Achaeans, and Spartans, as well as the tyrants who had been expelled from Pherae with their mercenaries. Philip had to withdraw again, and as a result the battles in central Greece continued without him, and the enemies wore each other out in these conflicts to his advantage. Thus he turned for some years to other issues in the north, to the situation in Thrace and Epirus and to his relations with the Chalcidian League, which had long ago ceased to be Philip’s ally in his war against the Athenians and had become an alien element in the much enlarged Macedonia. The folly of alerting Philip to this fact through insubordination presented him with a reason to intervene and led to the destruction of Olynthus in 348, the dissolution of the League, and the annexation of its territory. A military alliance with the Athenians, sealed in the summer of 349, was not enough to save the Chalcidians.

Indeed, throughout these years the Athenians had not managed to achieve military success against Philip. He for his part had not only refrained from seriously pursuing the Athenians, but had even repeatedly signaled his desire for peace by indications to this effect or even clear offers. However, his military activities decreased noticeably after 352, without his relinquishing his aim to wield decisive influence in Greece. But Philip could afford to wait. When the Phocians at last conceded defeat in 346, they informed him of their capitulation, and it was owing to him that the conditions turned out to be less harsh than had been demanded by some members of the Amphictyony.16 Philip could believe that he had resolved the situation in central Greece in a manner beneficial to himself. He was already assured of lasting influence in the region by his having been given both of the Phocian votes in the Amphictyonic council and by also being able to call on those of the Thessalians and their neighbors.

Shortly before this, in the spring of 346, peace had also been agreed with the Athenians, on the basis of the status quo.17 The Athenians thus had to concede Amphipolis and other places along the Macedonian–Thracian coast that had been lost; in return Philip guaranteed their ownership of the Thracian Chersonese which was crucial to Athenian survival. He demonstrated to the Athenians that this was very obliging of him while yet negotiating the Peace of Philocrates: as deliberations about the conditions he had proposed at Pella took place in Athens, he led a surprise campaign against Cersebleptes and forced him again to acknowledge Macedonian sovereignty. From here it would have been a stone’s throw to the Chersonese. Despite having once more demonstrated his military supremacy, Philip granted the Athenians a comparatively favorable peace in 346.18

However, it soon become apparent that Philip’s expectations of the Peace of 346 had been too high and that it was impossible for him to strengthen his own influence in Greece at the same time as developing good relations with the Athenians.19 On the face of it, over the next years he limited himself to securing and consolidating his rule in the north: in 345 he led a campaign against the Illyrians, and in 344 he executed some military operations in Thessaly. In the winter of 343/2 he arrived in Epirus, took some Greek cities on the coast for its ruler and thus bound him to himself more closely. Next, administrative reforms were implemented in Thessaly which allowed Philip to exert an even tighter grip on the country. Once the south (i.e., Thessaly), the southwest (i.e., Epirus), and the northwest (i.e., the Illyrian border) had been secured, the Thracian campaign of the years 342/1 could commence.

South of Thessaly Philip had not looked to expand the territory over which he ruled, yet he did not abstain from extending his influence there as well. At the same time he continued to court the Athenians and endeavored to avoid coming into conflict with them. He proved this for the first time in the autumn of 346 when the Athenians did not contribute to his campaign against the Phocians despite their alliance with him, did not send a representative to the Amphictyonic council, and offered an even greater provocation by omitting to send an official delegation to the Pythian Games which were being held under Philip’s stewardship for the first time. In view of the Athenians’ pro-Phocian attitude during the ten-year-long Sacred War and the general sentiment among the Amphictyons, it would have been easy for Philip to decide in favor of another Sacred War, this time against the Athenians. However, Philip not only refrained from a military advance against the Athenians, but even secured a resolution by the Amphictyonic council a little later which took their interests into account. On the other hand in 344 he supported Sparta’s enemies in the Peloponnese both financially and by dispatching mercenaries, which provoked an Athenian counter-delegation to the Peloponnese led by Demosthenes.

This illustrates Philip’s dilemma which finally led him to change his approach. Developing a good understanding with the Athenians was not easy after the blows they had been dealt over the years. His attempts to extend his own influence in Greece also cast a shadow over relations with the Athenians and hindered a rapprochement. Philip began by courting them, and in the winter of 344/3 offered to negotiate with them in revising the peace treaty of 346, but the negotiations foundered on the Athenians’ exaggerated demands. Philip reacted in the following year, 343, by once again exerting influence over the internal affairs of Greek cities, that is, Elis, Megara and Euboea, two of which lay in close proximity to Athens. He followed this warning shot by approaching the Athenians in early 342 with a renewed offer to improve relations. When he was again rebuffed he realized that an encounter to settle the matter once and for all could not be avoided, but he insured that he would determine the circumstances in which this was to take place. He proceeded to conquer Thrace, which until then had stood in a relation of loose dependency upon Macedonia, in order to annex the whole region up to the straits. With it under his control, it was possible to bring the Athenians to their knees.

However, the campaign against Thrace was aimed not only at the Athenians. In 344 the Great King had regained Cyprus, in 343 Phoenicia, and news of Persian military preparations that came to Philip led him to expect a reconquest of Egypt.20 While this was not an alarming prospect, given the reputation of the Persian empire in recent decades, which appeared to pose no threat to Macedonia, a newly consolidated Persian empire might well change the equilibrium of power in the Aegean. By expanding his own authority up to the straits, Philip thought to prevent this. In the summer of 341 the conquest of Thrace was complete, but Philip appears to have remained in this country for another winter in order to implement administrative measures.

Philip was not the only one who thought the decisive confrontation with the Athenians was unavoidable, however little he relished the prospect. Demosthenes likewise saw no other solution but war, but, in contrast to Philip, he purposefully worked toward it. He inflamed the situation by provocation and finally in the spring of 340 managed to establish a Hellenic League directed against Philip; besides Athens, this (purely defensive) alliance included the cities of Euboea, Megara, Corinth with its colonies Leucas and Corcyra, as well as Achaea and Acarnania.

In the mean time Philip led his troops against Perinthus which he was unable to take, in particular because it received support from the Byzantians and the Persian satraps on the eastern shore of the Propontis. In the autumn of 340 he attempted a raid on Byzantium with part of his troops. In his vicinity cruised the Athenian general Chares, whose task was to provide safe conduct into and through the Aegean for the grain ships arriving from the Black Sea region, and who met with the Persian generals for a conference while this fleet assembled. By now Philip must have been convinced that war was inevitable, and the fleet that was so easily within his reach was so tempting that he could not wait for another such opportunity for an entire year. He seized it during Chares’ absence and thereby – in addition to gaining rich booty – provoked the Athenian declaration of war. That this would be the consequence must have been obvious to him. The question is only whether he wished to overcome the Athenians in battle or whether, by striking against the grain fleet, he did not also wish to convince them of their inferiority at sea. In any case, he did not at first concern himself with the Athenians but continued his maneuvers against Byzantium. This city, however, was now successfully supported by the Athenians, and Philip was forced to put an end to his operations in early 339. But instead of marching against the Athenians he campaigned against the Scythians near the mouth of the Danube to safeguard his new conquest, Thrace, from this direction as well, and then returned to Macedonia through the territory of the Triballians. Here a call for help from his friends in central Greece soon reached him.

For, of course, Philip had not forgotten the Athenians. They had so far been unable to mobilize their allies against him and he now attempted to isolate them further by inducing others to bring a charge against them in the Amphictyonic council. The allegation against them was cleverly chosen: during the Phocian War the Athenians had put up votive offerings, intended as a memorial of their victory over the Persians and Thebans in the year 479, in the as yet unconsecrated temple of Apollo in Delphi. That it was sacrilege was clear and it was expected that the city would be ordered to pay a large fine, if only because of Philip’s majority in the Amphictyonic council. Naturally, the Athenians would not comply, and the Thebans were unable to avoid participating in the Sacred War which would then have to be waged, if only because of its cause. This extremely skillful plan failed, because Aeschines of all people represented Athenian interests in Delphi at the time and was able to redirect the anger of the Amphictyons against the small city of Amphissa with a clever counter-accusation, with the result that a Sacred War did ensue but followed a different course from that Philip had intended. The Thebans, whom Philip had planned to employ in his interests, indeed even in his place against the Athenians, did not only back up the Amphissaeans, but turned against Philip and snatched control of the Thermopylae from him. Thus it became impossible for the other Amphictyons to lead their troops south and to proceed with a military campaign against Amphissa, and in the autumn of 339 they had to call on Philip who had just returned from the Danube.

In this way the war in central Greece, which Philip had first attempted to avoid and then had to fight and which he continued to try to resolve after it had broken out by repeatedly offering to enter into negotiations, erupted after all. But a military decision could not be avoided, and it came at the beginning of August 338 at Chaeroneia unequivocally in favor of the Macedonian king. He was again able to begin to order his relations with the Greeks and to set the direction for his next undertaking.21

His longstanding ally Thebes received a heavy punishment for having defected to the enemy: a Macedonian occupying force was stationed in the Cadmeia and those who had been exiled were allowed to return; this brought Philip’s friends into power and led to a change of government. The Boeotian League was not dissolved; in this way the Thebans who now lost their positions of power in Boeotia were meant to be held in check. Refounding the Boeotian cities which the Thebans had destroyed during their rule served the same purpose. All these measures had only one aim: Thebes was to be weakened as a land power and subject to the control of hostile neighbors.

In 346 the Athenians had obtained a fairly favorable peace and entered into an alliance with Philip. The peace and alliance were later extended to Philip’s successors and thus declared to be everlasting. We saw earlier Philip’s courting of the Athenians in subsequent years as well as Demosthenes’ attempts to sabotage any rapprochement, to build up an alliance of Greek cities against Philip, and finally to bring about a decisive battle. In Philip’s eyes the Athenians were therefore more than guilty and let others become culpable, and did not deserve any leniency because of their stubbornness. And yet they received it in greater measure than could have been expected. Philip did not touch Athenian democracy despite all his bad experiences with it, and he did not even invade Attica. Moreover, the Athenians were allowed to retain their possessions abroad, Lemnos, Imbros, Skyros, and Samos, and had to cede only the Thracian Chersonese to Philip. Since the Athenians depended on the cereal imports from the Black Sea region, the loss of the Thracian Chersonese meant that they were obliged to conduct themselves well toward Philip or face the possibility of a blockade of the Hellespont. The Athenians were also to be deprived of any opportunity to prepare for or wage a war against Philip at sea, and therefore the Second Athenian Confederacy, or what remained of it, was dissolved.22

We know barely anything about how other Greek states fared, especially those that had sent troops to Chaeroneia. Corinth and Ambracia had to accept a Macedonian garrison.23 Together with the Theban Cadmeia, this made for three bases, which appear to have been sufficient for Philip. The distribution of these garrisons was well chosen: the one in Corinth controlled access to the Peloponnese, and the arrangements which were made here soon afterward guaranteed the good behavior of the peninsula. Ambracia controlled northwestern Greece and was situated strategically between Epirus and Aetolia, two new rising states who had thus far been promoted by Philip but could not be trusted. Lastly, Philip knew the Thebans personally and was aware of their ambitions to rule over central Greece. In order to prevent this, his friends kept hold of the reins in the city and, since they were relatively few in number and were opposed by the demos, they had to be safeguarded by a Macedonian garrison. In some states the outcome of the war appears to have brought friends of the Macedonians into power, without our having to assume a direct intervention by Philip in their internal affairs.

These were the measures taken immediately following the decision at Chaeroneia, which demonstrate a great divergence between the conditions for peace and in which the treatment of his former enemies is at times strangely disproportionate to their actual guilt. Something similar is true of Philip’s actions in the Peloponnese. Members of the erstwhile coalition of enemies in the north of the peninsula were spared, but Sparta, which had remained neutral, was significantly weakened in that it had to cede frontier areas to its hostile neighbors Messenia, Megalopolis, Tegea, and Argos. The aim of this was not to eliminate Sparta completely, but to strengthen its neighbors at its expense, with the result that none of these states was in a position to develop a hegemony over the whole Peloponnese. They owed their territorial expansion to Philip, and as long as Sparta continued to exist and to hope to regain what it had been forced to cede, these states were not allowed to forget who their friend and ally was.

With these arrangements Philip made sure that the former principal Greek powers would not again be in a position to assume a role that would compete with his. All three were significantly weakened, and care was taken to keep them under control for the future: the Thebans by the change in government, the garrison in the Cadmeia, and the strengthening as well as multiplication of the individual cities of the Boeotian League; the Spartans by territorial losses and the mistrust of the hostile states which surrounded them; and the Athenians by the loss of the Thracian Chersonese and the dissolution of the meager remainder of the Confederacy. The differences in treatment become even more obvious when we consider what the Athenians held onto and what comparable potential had been taken from the other states. Thebes and Sparta were land powers and as such had clearly been weakened. The might of the Athenians lay in their fleet which Philip allowed them to keep, even though he had nothing comparable to set against it.

The sparing treatment of the Athenians is astonishing, and attempts have been made to interpret it. For instance, Philip may have wished to retain the Athenian fleet in order to be able to deploy it in a war against the Persian empire.24 This would also explain his courting of the Athenians from 348 onward, which is an indisputable fact, and, as we saw earlier, a certain forbearance toward the Athenians could be observed even before that date.

This leads to the question as to when Philip began seriously to toy with the thought of marching against the Persian empire and when his politics on the southern Balkan peninsula were colored by it. In the sources the notion of a Persian campaign first appears for the year 346, although this is in a later source. After his report of the end of the Phocian War, Diodorus speaks of Philip’s wish to be appointed commander of the Greeks entrusted to lead the war against the Persians (16.60.5). Diodorus or his source knew that this wish, ascribed to the king in 346, became a reality later and may have dated it wrongly to an earlier period. On the other hand, planning a war against the Great King in 346 was not unrealistic if we consider the situation in the Persian empire as Isocrates describes it in his letter addressed to the Macedonian king in the summer of that year.25 With it, he hoped to win Philip for a military campaign against the Persian empire. Isocrates could propose such a plan only if he were confident that such a proposal would be thought feasible because of the power structure in the eastern Aegean and the state of affairs within the Persian empire at the time. It was also not the first time that Isocrates publicly proposed a Persian war. As early as in the Panegyricus of the year 380 he had lobbied for a reconciliation between the Greeks and a campaign against the Persian empire, and he could not have hoped to achieve anything with this pamphlet if his readers had been convinced that a war against the Great King was impossible.

The tyrant Jason of Pherae who represented the strongest power in central Greece toward the end of the 370s must have been among his readers; he was given credence when he announced that he would march against the Persian empire. That this claim is historical is certain: for one, Isocrates refers to it in 346 in his letter to Philip (119–20), then we have a guarantor of Jason’s ambitions in Xenophon who was no longer alive at the time when the Philippus was being composed and who has the tyrant argue as follows:

You are surely aware that the Persian king too owes being the richest man in the world to income not from the islands but from the mainland. To make him a subject of mine is a plan which I believe to be able to realize more easily than to subject Hellas to me. For I know. . . by what kind of army – and this is true as much for Cyrus’ troops during his march inland as for those of Agesilaus – the Persian king has already been brought to the verge of ruin (Xen. Hell. 6.1.12).

Xenophon himself had participated in the military operations to which he makes Jason refer in the above passage. Isocrates had already employed these examples in 380 (Panegyricus 142–9), and the historian Polybius also made use of them in the second century when he traced Philip’s planned campaign against the Great King back to the proven ineffectiveness of the Persians when faced with Greek armies (3.6.9–14). Polybius does not say when the Macedonian king decided on this plan for he is concerned purely with the preconditions for it. These had already been in place since the beginning of the fourth century. Since the successful retreat of the 10,000 Greek mercenaries and even more since Agesilaus’ maneuvers in western Asia Minor, the weakness and military inferiority of the Persians had become blatantly obvious. Consequently it was by all means realistic when Isocrates spoke of a joint campaign against the Great King by all Greeks in his Panegyricus in 380. Likewise, the tyrant Jason of Pherae was able publicly to consider pursuing a Persian war without having to fear being laughed at. And that even tough Jason at the time represented no more than the greatest land power in central Greece, the region over which Philip became supreme commander in 352. And this was basically only an annex to the then consolidated Macedonia which had been expanded in all directions. In contrast, the picture presented by the Persian empire in the first years of Philip’s rule was such that it was even more inviting to invade than it had been at the beginning of the century. This was even more so after the end of the second phase of Macedon’s rise, which extended from 352 to 346 and at which conclusion Isocrates asked the Macedonian king in an open letter to march against the Persian empire. Such an undertaking could reasonably be seen to promise even greater chances of success. The overview of Philip’s actions and movements should have demonstrated that he had been interested in power, and in extending it, all his life. With this attitude the notion of a Persian war may already have entered into his considerations at a fairly early stage. In conclusion we have to ask at what point it was first conceived, when it may have taken shape, and how far it determined his policies on the Balkan peninsula.

Before assuming the throne Philip had spent some years as a hostage in Thebes at the house of the general Pammenes. In early 353 the latter was sent to Asia Minor with 5,000 soldiers to aid the insurgent satrap Artabazus. Philip facilitated the passage through Macedonia and Thrace for him and therefore knew how large a force was considered sufficient to be deployed against an army of the Great King. Philip also heard of Pammenes’ successes after Artabazus had fallen out with him and fled to Macedonia, if not before.26 It may thus easily be imagined that as early as the end of the 350s Philip was toying with the idea of a future war to be fought against the Persians. But the circumstances for such an undertaking and the prolonged absence it necessitated were not yet favorable. He was at war with the naval power Athens, and even if the Athenians had so far been unable to harm him – they have actually lost one stronghold after another to him – as potential allies of the Great King they could certainly become an irritant for him. Likewise, while he had secured Thessaly in 352 against the tyrants of Pherae and the advancing Phocians, Philip had not succeeded in occupying the Thermopylae. Thus the opportunity to exert a decisive influence over central and southern Greece did not yet exist.

But Philip could prepare for a Persian war in another way. Immediately following the retreat from the Thermopylae, he led his army against Thrace and up to the Propontis. Of course this march also served as a display for the Athenians to demonstrate that he would always be able to threaten their grain supply routes and their possessions on the Chersonese. At the same time the subjection of Cersebleptes as vassal, and Philip’s alliance with Byzantium and possibly other coastal cities, safeguarded a territory that would some day prove useful when he was required to lead land forces against Asia Minor. The notion of such a campaign, which must have been a factor in Philip’s deliberations, must have seemed even more attractive a short time later when not only did the Great King fail once again to regain Egypt, but unrest broke out in the satrapies bordering Egypt as a result of the defeat. It does not appear to be a coincidence that for a year and a half from the autumn of 351 nothing is heard of any actions against Athens, and that these were resumed only in the context of Philip moving against the Chalcidian League, and even then he offered peace. Therefore much points to Philip having conceived the plan of a war against the Persian empire as early as in the late 350s and that he let it guide his policies in Greece. These were most likely based on the following consideration: for a Persian campaign he needed the Greeks, if not as fellow combatants, at least as sympathetic neutral powers, and he had to insure that they could not be incited by the Persian king behind his back and cause him difficulties. The latter related primarily to Athens where the city and harbor represented fortifications that were difficult to capture and could not under any circumstances be allowed to be turned into a Persian base on the European mainland. It would of course be even better to win over to his side the Athenians with their naval power and nautical expertise, so as to meet the Persian fleet with a force that could match it.27

If we accept that these were Philip’s intentions, his approach toward the various Greek states, which was very different from his approach toward the barbarians of Illyria and Thrace, against whom he campaigned more than once and whom he treated without squeamishness, becomes more comprehensible. With the Greeks, Philip intervened only when absolutely necessary, and then with such force that one strike was sufficient. After victory he would show carefully measured leniency. He preferred, if possible, not to strike against the Greeks at all. This had proved to be illusory, but after the victory at Chaeroneia Philip again proceeded to put in order his relations with the Greeks and to set the direction for his further plans once and for all. Philip’s aim to create the right conditions for a safe prolonged absence and a successful attack on the Persian empire was served by the measures implemented directly after Chaeroneia, which become understandable in view of the background on which light has now been shed. That the Athenians were for the most part spared accorded with Philip’s interest as did the harsh treatment of the Thebans. The participation of the Theban hoplites in the Persian war, in comparison to the Athenian fleet, appeared to be less important. Philip was able to recruit infantry soldiers in sufficient numbers from Macedonia. On the other hand, the Thebans remained the strongest Greek land power and could become a threat because of their ambitions by upsetting the peace in central Greece during Philip’s absence.

With the exception of the Thebans, Philip granted most of his opponents in war lenient conditions, but, for all his moderation, in dealing thus with them he also laid solid foundations for establishing a Macedonian hegemony over Greece. Moreover, in the Spartans he weakened a neutral but potentially dangerous power. Finally, shifting the balance of power within a state was one of the measures to secure his rule. In the end these were all individual measures, and Philip was justified in doubting whether, taken together, they represented a solid basis for controlling Greece. To achieve this required an order to incorporate all states that was not immediately seen as an instrument of Macedonian rule. A set of tools that had by now become established in Greece, without being connected to the hegemonial models of the Athenians, Spartans, or Thebans, was ideal.

Thus Philip secured the arrangements contractually with a Panhellenic peace treaty (koine eirene), the so-called Corinthian League, which was also to serve as the basis for Alexander’s relations to the Greek states.28 In the first half of 337 representatives of the Greek states assembled in Corinth at Philip’s invitation and agreed the freedom and autonomy of all Greeks as in previous koine eirene treaties. Not only was any military attack on a member of the peace treaty prohibited and a court of arbitration, it seems, established for territorial disputes, but in addition to guaranteeing the states’ current territorial possessions the treaty likewise protected their current constitutions from being overthrown in any way. Furthermore, the treaty obliged every member of the peace treaty to provide military aid to victims of aggression and to consider as an enemy anyone disturbing the peace. Earlier peace treaties had contained similar regulations, but the problem had always been how to ascertain bindingly who had broken the peace and how to set in motion disciplinary measures. Now for the first time institutions were created that not only insured the regulations were being kept to, but could if necessary enforce them and thus rebuild the order that had been disturbed. At the heart of this koine eirene was asynedrion, a body at which all participating powers were represented by delegates and whose decisions were binding on all member states. In order to execute the decisions of the synedrion, the office of hegemon was introduced. In military operations, the hegemondetermined the size of each contingent and was in command. As expected, Philip, who belonged to the League in his own right and not as Macedonian king, was voted to the office.

With the Corinthian League Philip created a legal basis for his hegemony in Greece and thus sealed Macedonia’s rise under international law. To this end he had adopted a type of treaty which the Greeks had by now become accustomed to, but continued to develop it by creating an overseeing and decision-making body and by introducing the office of the commander of the League’s forces to implement its decisions. The best orders and contractual regulations would have been worthless if the hegemon did not represent a power no one would have dared to contradict, even if there had been no treaty on the southern Balkan peninsula.

The Corinthian League created by Philip was no doubt the most effective of all general peace treaties on land that had been agreed so far and appeared to stand the best chance of guaranteeing that the peace would be kept. Although this peace had been imposed by the victor and was a means of consolidating his supremacy and securing his hegemony in Greece, he had skillfully veiled it in the form of a koine eirene, acceptable to all states, which many had tried in vain to establish in Greece for fifty years. In particular, it was likely that the smaller states would welcome the new order, for it guaranteed them protection against their more powerful neighbors. Internal peace across Greece now appeared to have been secured, and in return many a state may have been willing to accept a degree of loss of its own independence. The status quo was, however, guaranteed primarily by the person of the hegemon – and therefore the oath of the koine eirene, part of which is transmitted epigraphically, also included the obligation not to abolish the rule of Philip and his successors. In all this Philip’s intention was not to develop direct rule over the Greek states but simply to govern them indirectly as a precondition for the Persian war, which it seems he had already decided to pursue from the late 350s. That he had to postpone these plans time and again had been due to his enemies in Greece, foremost Athens. Now there was nothing to hold him back any longer.

Following a motion by Philip, the synedrion agreed the war against the Persian empire and granted the hegemon additional powers for the duration of the campaign. As early as spring 336 a Macedonian army of 10,000 men crossed the Hellespont under Parmenion and his son-in-law Attalus, in order first to cause the Greek cities of Asia Minor to defect. Philip intended to follow as soon as military preparations had been completed, but it did not happen, for he was murdered in the autumn of 336. This time the succession in Macedonia went smoothly and the new ruler Alexander III also secured the hegemony in Greece despite some difficulties with the Thebans. As he set out on his campaign against the Persian empire in early 334, Alexander was able to do so trusting fully in the foundations laid by his father, and when he later began to be called “the Great,” it was overlooked that he was the son of an even greater man.

1 The author wishes to thank Dr. Kathrin Luddecke for the English translation.

2 For more recent studies of Macedonian history up to the time of Philip II see Hammond 1972; Hammond–Griffith; Errington 1990; Borza 1990, 1999.

3 Zahrnt 1984.

4 On Macedonia during the Persian Wars see Zahrnt 1992.

5 Westlake 1935: 51–9.

6 Carney 1983: 260.

7 On Amyntas III see Zahrnt, forthcoming.

8 Xen. Hell. 5.2.11–24, 37–43; 3.1–9, 18–19, 26; cf. D.S. 15.20.3–23.3.

9 On the history of Macedonia during the Theban hegemony see Hatzopoulos 1985.

10 On Philip II and the sources for his reign see (in addition to the works cited above): Ellis 1976; Cawkwell 1978; Griffith in Hammond–Griffith 210–726; Hatzopoulos and Loukopoulou 1980; Hammond 1994b: 11–17; Bradford 1992; McQueen 1995; Hammond 1994a. Since no continuous account of Philip’s history exists apart from the incomplete report in Diodorus’ sixteenth book and Justin’s rather unreliable statements (books 7–9), the evidence has to be collated from the most diverse ancient sources; therefore these references are not provided when discussing diplomatic and military events, and readers are referred instead to the studies mentioned.

11 On Philip’s intervention in Epirus, see Errington 1976.

12 On Amphipolis see Hatzopoulos 1991: 62ff., and on relations between Philip and the Chalcidian League Zahrnt 1971: 104ff.

13 On Philippi, Collart 1937 is still worth reading.

14 Cf. Griffith 1970.

15 On the so-called Third Sacred War, see Buckler 1989.

16 On the Phocians’ contract of capitulation with Philip II, see Bengtson 1975: ii. 318–19.

17 Overview of the sources in Bengtson 1975: ii. 312ff.

18 According to Markle 1974 and Ellis 1982, Philip even had the intention of weakening the Thebans in favor of the Athenians in 346 (which, as we shall see later, did indeed happen after the battle at Chaeroneia), but these plans had been thwarted by the machinations of Athenian politicians. The two speeches that Demosthenes and Aeschines made three years later during the trial against the latter are our main sources for the agreement of the Peace of Philocrates; and since they both spoke on their own behalf and were not always particular about the truth, even in later statements, we cannot discover Philip’s real intentions with certainty, but, as we shall see later, the Macedonian king was already at pains to be on friendly terms with the Athenians even at the time.

19 On what follows see Wust 1938, as well as Perlman 1973; Ryder 1994.

20 On the situation in the Persian empire at the time, see Zahrnt 1983.

21 On the measures then taken, see Roebuck 1948.

22 On the peace and alliance between Philip and Athens, see Schmitt 1969: iii. 1–7, an overview of the sources and discussion of previous literature.

23 Chalcis is often supposed to have been the fourth base but there is no evidence at all for this.

24 See, e.g., Griffith 1979: 619–20. Ellis 1976: 11–12, 92 and Cawkwell 1978: 111ff. assume this even already for the time of the Peace of Philocrates.

25 Philippos 99–104; cf. Zahrnt 1983: 278–9.

26 In this context Amminapes must also be mentioned, a noble Parthian, who, at some point which can no longer be ascertained and for reasons unknown, was exiled by the Persian king Artaxerxes III Ochus, came to Philip’s court, and apparently became a friend of the Macedonians (see Heckel 22).

27 This is also the view of the scholars mentioned in n. 24: Ellis 1976 has the Macedonian king toy with the notion of a Persian war as early as the late 350s, while Cawkwell 1978 and Griffith 1979 consider that such a plan can be regarded as proven with any certainty only for the time of the Peace of Philocrates. Such a consensus among more recent scholars may of course not remain unchallenged, and thus Errington 1981 has dismissed all three estimated timings and has Philip conceive the idea of a Persian war only just before the battle at Chaeroneia. After his diplomacy in central Greece had failed, Philip had wished to reconcile the Greeks to Macedonian authority by making a dramatic Greek gesture in proposing a Persian war, in other words, he made a national concern his own. For Buckler 1996, Philip’s possible attempts to develop a hegemony over Greece have left no traces at all, and we can only speculate about his ambitions toward the Persian empire, and his actual target right until the end was the Athenians. In view of the arguments in this chapter, a rebuttal appears superfluous.

28 Overview and detailed analysis of the sources in Schmitt 1969: iii. 3–7. The standard study of the Corinthian League of Philip II is now Jehne 1994: 139ff.; see Perlman 1985 on the background of the interstate relations during the fourth century. See Poddighe, ch. 6.