2

Waldemar Heckel

On the seventh day of the Attic month Metageitnion (August 2) 338, Philip II, with his son Alexander commanding the cavalry on the left, defeated a coalition of Thebans and Athenians at Chaeroneia, destroying the vaunted Theban Sacred Band and, as many writers of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries have commented, dealing the fatal blow to “Greek liberty.” Today we may be more circumspect about the nature of Greek “freedom,” but the fact remains that Chaeroneia was a turning point in Greek history. Philip promptly consolidated his gains on the battlefield by forging the League of Corinth,1 which he was designated to lead as its hegemon in a crusade of vengeance against Persia. But dynastic politics, following on the heels of personal misjudgment, supervened, and in 336 the Macedonian king fell victim to an assassin’s dagger before he could witness his statue carried into the theater at Aegae (Vergina) along with those of the twelve Olympians.2 The ceremony was to have been a fitting tribute to a descendant of Heracles about to embark upon a Panhellenic war of conquest. The undertaking and the greatness that its fulfillment held in promise were to be Alexander’s inheritance.

Straightaway, it was necessary for the new king to establish his authority. Rivals for the throne, and their supporters, were swiftly dispatched: first of all, two sons of Lyncestian Aëropus, Arrhabaeus and Heromenes, were publicly executed on charges of complicity in the assassination (Arr. 1.25.1). The murderer himself, Pausanias of Orestis, had been killed in flight by the king’s bodyguards. If there was any truth to the charge that the Lyncestians had conspired with him,3 they appear to have given little help (unless they supplied the horses that were meant to facilitate his escape), nor was it clear if they sought the throne for a member of their own family, or for Amyntas son of Perdiccas (Plu. Mor. 327c). The vagueness in the reporting of their alleged crime is doubtless Alexander’s doing: it suited his purpose to eliminate all contenders, including the hapless Amyntas. Indeed, it is hard to credit the existence of such a conspiracy without dismissing its perpetrators as inept, if not downright stupid. The Lyncestians ought to have secured the support of Antipater, the powerful father-in-law of their brother Alexander. But clearly they did not. Alexander was reportedly the first to proclaim Alexander king, doubtless at the urging of Antipater, who proved his own loyalty and bought the life of his daughter’s husband by abandoning Arrhabaeus and Heromenes. Even in later years, when distrust had tainted the relationship between king and viceroy, no charge of conspiring to kill Philip or prevent Alexander’s accession was ever leveled against him. Amyntas son of Perdiccas, too, appears to have been eliminated swiftly – certainly he was dead by the spring of 335 (Arr. 1.5.4). A companion of his, Amyntas son of Antiochus, fled Macedonia and took service with the Persian king, but it is unlikely that this occurred before the death of Perdiccas’ son. The latter was a nephew of Philip II and rightful heir to throne, whose claims the state, in need of strong leadership to combat external foes, had swept aside in the years that followed the death of Perdiccas III in 360/59.4Married to Philip’s daughter by an Illyrian wife, the discarded heir had lived quietly, without incurring suspicion; in all likelihood, he became the victim of the aspirations of others and of his own bloodline.5

Elsewhere, Attalus, guardian of Philip’s last wife Cleopatra-Eurydice, may have been perceived as a threat. But, in this case as well, stories that Attalus was conniving with the Athenian Demosthenes and other Greeks (D.S. 17.5.1), if they are true, point only to the desperation of his situation. So weak was his position that he could not even persuade his own father-in-law, Parmenion, to side with him, though together they commanded a substantial force in northwestern Asia Minor. Alexander’s agent, Hecataeus, secured Attalus’ elimination, something that could not have been achieved without Parmenion’s acquiescence. Some scholars have been misled into attributing too much power to Attalus; for his influence with Philip must be explained by the fact of his relationship to Cleopatra-Eurydice.6 His remark at the wedding feast in 337, that the marriage would produce “legitimate heirs” to the throne, marked him for execution when Alexander became king. It was the tactless utterance of a drunken man, but fatal nonetheless. His relatives by blood and marriage, though hardly contemptible, could do little to save him and found it expedient not to try. Parmenion obtained a more suitable husband for his widowed daughter in the taxiarch, Coenus son of Polemocrates. The father-in-law and his sons received high offices in the expeditionary force.7

Domestic problems were, moreover, balanced by defection in the south and challenges on the northern and western marches of the kingdom. In western Greece, Acarnania, Ambracia, and Aetolia openly declared themselves hostile to Philip’s settlement;8 the Peloponnesians too evinced widespread disaffection. But Alexander made a rapid foray into Thessaly, effected by means of cutting steps into Mt. Ossa (“Alexander’s Ladder”), and induced the Thessalians to recognize him as Philip’s heir as archon of their Thessalian League, thereby also gaining a voice in the Amphictyonic Council. With the added moral authority, the new king granted independence to the Ambraciots, and then moved south into Boeotia preempting military action there. The Athenians saw to their defenses and sent an embassy to Alexander; Demosthenes was said to have abandoned the embassy at Cithaeron, fearing the king’s wrath.9 Now, too, the League of Corinth declared Alexander its hegemon, but the sparks of disaffection were yet to ignite into full-scale rebellion.

In the north, Alexander turned against the so-called “autonomous” Thracians and the Triballians, tribes dwelling near the Haemus range and beyond to the Danube. South of the Haemus, the Thracians sought to blockade Alexander’s force by occupying the high ground and fortifying their position with wagons. Unable to resist the attacking Macedonians, even after pushing the empty wagons into the path of the oncoming enemy, they were dispersed with heavy casualties. The Triballians responded by transferring their women and children to the Danubian island of Peuce, which their king, Syrmus, defended with a small but adequate force. The remainder of the Triballians evaded the Macedonian army as it hastened north, and occupied a wooded area near the river Lyginus, less than a day’s march from the Danube. But Alexander turned back and dealt with them, using his skirmishers to dislodge the Triballians from the forest before catching them between two detachments of cavalry and attacking their center with the phalanx. Some 3,000 were killed; the remainder escaped into the safety of the woods.

An attempt on Peuce failed: the ships which Alexander had brought up from the Black Sea were insufficient in numbers and the banks of the island too well defended. Instead the Macedonians launched an attack on the Getae who lived on the north bank of the river. After destroying their town and devastating their crops, they forced the Getae to come to terms. Syrmus too sent a delegation asking for terms; possibly, Alexander demanded that he contribute a contingent to serve in his expeditionary army, in which some 7,000 Illyrians, Odrysians, and Triballians are found in 334.

To the west, the Illyrians, inveterate enemies of Macedon, threatened the kingdom’s borders as Glaucias son of Bardylis allied himself with the Taulantian chief Cleitus. At Pellium Alexander displayed what a superior army led by a brilliant tactician could do. The campaign was a textbook example of speed and maneuver: the discipline of Alexander’s troops mesmerized the Illyrians, outwitting them with a display of drill that turned them into spectators when they ought to have been taking counter-measures.10 But the preoccupation with northern affairs gave new impetus to the anti-Macedonian party in central Greece. The reckoning was long overdue, and the consequences for Thebes devastating.

Encouraged by rumors that Alexander had been killed in Illyria and by the false hope of Athenian aid, the Thebans besieged the Macedonian garrison established on the Cadmeia after Chaeroneia.11 The king’s response was swift, far more so than they could have imagined; for Alexander bypassed Thermopylae and arrived before the gates of Thebes within two weeks. Negotiations amounted to little more than posturing by both sides and Thebes, abandoned by the very Athenians who had incited the rebellion, was quickly taken, though not without great bloodshed. The city was razed and the survivors enslaved, all as later – and doubtless contemporary – apologists claimed by the decision of a council of Alexander’s allies. Many of these were Boeotians and Phocians with a long history of enmity toward the city, but it could also be argued that it was condign punishment for a century and a half of collaboration with Persians (medismos or “Medism”). So it proved both a warning to other cities in Greece that Alexander would not tolerate rebellion and a symbolic beginning of the campaign against the true enemy of Greece and its supporters.

The Athenians, for their part, hastened to display contrition, foremost among them the very self-serving politicians who had fomented the uprising from the safety of the bema. Nevertheless, their prominence diverted the young king’s wrath from the common citizens: instead he demanded the surrender of ten orators and generals. In the event, only the implacable Charidemus was punished with exile, although Ephialtes fled to Asia Minor in the company of Thrasybulus; several of the others outlived Alexander to rally their citizens to another disastrous undertaking in 323/2. It is important to note, however, that whereas the destruction of Thebes could be justified with reference to the city’s history of Medism, any hostile act against the Athenian state as a whole would have undermined Alexander’s Panhellenic propaganda.12

The Asiatic campaign began in spring 334: in fact, it was a continuation of the initiative launched in spring 336 but postponed by Philip’s murder and the unrest in Greece. The advance force under Parmenion, Attalus, and Amyntas had faltered and was now clinging to its bases on the Asiatic side of the Hellespont. Attalus’ execution had doubtless undermined the morale of the army, but the setback had as much to do with the vigorous resistance by the forces of Memnon the Rhodian.13Cities that had proclaimed their support of Philip – some with extravagant honors for the Macedonian king – reverted to a pro-Persian stance (Rhodes and Osborne 83–5), and it was doubtless the lackluster performance of the first Macedonian wave that persuaded Darius III that a coalition of satraps from Asia Minor was sufficient to confront the invaders. For Darius, in addition to securing his claim to the Persian throne, had been preoccupied with an uprising in Egypt.14

The army that crossed the Hellespont comprised 12,000 Macedonian heavy infantry, along with 7,000 allies and 5,000 mercenaries; the light infantry were supplied by Odrysians, Thracians, and Illyrians, to the number of 7,000, as well as 1,000 archers and the Agrianes, for a grand total of 32,000. To these were added 5,100 cavalry (thus D.S. 17.17.3–4; but other estimates range from 34,000 to 48,000 in all). At the Granicus River,15 to which the coalition of satraps had advanced after their council of war in Zeleia, the “allied” forces confronted a Persian army that included a large contingent of Greek mercenaries. By choosing to stand with the Persian forces they had disregarded an order of the League and committed high treason, and Alexander was determined to make an example of them (Arr. 1.16.6). Distrusted by their employers, the mercenaries were not engaged until the battle was already lost (McCoy 1989). Nevertheless, they paid a heavy price in the butchery that followed, and those who surrendered were sent to hard labor camps in Macedonia, stigmatized as traitors to a noble cause and denied whatever rights might be granted prisoners of war. This stood in sharp contrast to Alexander’s clemency on other occasions, and it would be almost three years before he relented and authorized their release. For their part, the Persian cavalry and light infantry fled as the victors turned to deal with the mercenaries. Arsites, in whose satrapy the disaster had taken place, escaped and thus bought enough time to die by his own hand. Panoplies from the battle were sent to Athens with the dedication, “from Alexander son of Philip and all the Greeks, except the Lacedaemonians,” maintaining the pretense of a common cause while directing criticism at the Spartans for their refusal to join the League.

Victory at the Granicus cleared the path for the conquest of the Aegean littoral. Many states came over voluntarily, while others were prevented by the presence of Persian forces from declaring for the Macedonian conqueror. This should not be seen as enthusiasm for Macedonian “liberation” but rather as an opportunity for the enemies of the existing regimes to overthrow their political masters. Far different was the case of Mithrenes, the hyparchos of Sardis, who surrendered the city despite its superb natural defenses (Briant 1993a: 14–17). The death of Spithridates at the Granicus had left Lydia without a satrap (cf. Egypt after the death of Sauaces at Issus), and Mithrenes, making a realistic appraisal of the Persian military collapse in Asia Minor, was motivated by self-preservation and the hope of favorable treatment. Alexander received him honorably, although it would be late 331 before he reaped as his reward the unenviable task of ruling Armenia. To the Aeolic cities, not directly in the army’s path, the king sent Alcimachus – a prominent Macedonian and, apparently, a brother of Lysimachus – to establish democracies. Alexander meanwhile turned his attention to Miletus and Halicarnassus, where resistance continued; for the Persian navy still dominated the eastern Aegean and Darius’ general Memnon had concentrated his forces in that area. Miletus was taken with relative ease, when the Macedonians controlled the access to the harbor before the Persian fleet could arrive.16 Nevertheless, Alexander decided at this point to disband his fleet – its strength, quality, and loyalty were all suspect – and concentrate on engagements by land. The decision, though baffling to some at the time, would prove to be a wise strategic move and an economic blessing.

Figure 2.1 Bronze equestrian statue of Alexander the Great, found at Herculaneum. Museo Archeologico Nazionale, Naples. Photo: Foto Marburg/Art Resource, New York.

At Halicarnassus, Memnon and Orontopates directed a stubborn defense, inflicting casualties on the besiegers and setting fire to their siege-towers.17 But the city was quickly cordoned off and eventually taken; for Alexander found a less costly, political means of gaining control of Caria. He had received envoys from neighboring Alinda, where Ada, the aging sister of Maussolus, and rightful queen of Halicarnassus, was residing. Some time after the death of her husband (also her brother), Idrieus, Ada had been deposed by yet another brother, Pixodarus.18 When Pixodarus died shortly before the Macedonian invasion, the administration of the satrapy was given to Orontopates, who appears to have married the younger Ada, a bride once offered to Alexander’s half-witted sibling, Arrhidaeus.19 By restoring the former queen to her kingdom, and by accepting her as his adoptive mother, Alexander earned the goodwill of the Carians. Sufficient forces were left with Ada to compel the eventual surrender of Halicarnassus, thus freeing Alexander to proceed into Pamphylia. But the act of reinstating Ada, like the king’s treatment of Mithrenes, was a departure from the official policy of hostility to the barbarian. Few in the conquering army will have cared about the Hecatomnid record of philhellenism.

Over the winter of 334/3, Alexander campaigned in Lycia and Pamphylia, rounding Mt. Climax where the sea receded, as if it were doing obeisance (proskynesis) to the future king of Asia (Callisthenes, FGrH 124 F31), just as the Euphrates had lowered its waters for the younger Cyrus in 401 (Xen. Anab. 1.4.18). This apparent foreshadowing gained credence in spring 333 when Alexander slashed through the Gordian knot with his sword and claimed to have fulfilled the prophecy that foretold dominion over Asia for the man who could undo it. While prophecies could be carefully scripted by the spin-doctors, mastery over Asia would require military victory over Darius III, who, by the time Alexander entered Cilicia, had amassed an army on the plains of northern Mesopotamia at Sochi. Alexander’s own advance had been methodical, aiming clearly at the coastal regions that might give succor to the Persian fleet and the satrapal capitals with their administrative centers and treasure houses. Near Tarsus he fell ill, collapsing in the cold waters of the river Cydnus, perhaps stricken with malaria.20 That Darius interpreted the Macedonian’s failure to emerge from Cilicia as cowardice (Curt. 3.8.10–11) may be attributable to the sources who wished to depict the Persian king as a vainglorious potentate whose actions in the field belied his boastful pronouncements. On the other hand, it is not unlikely that the Persians had a genuine expectation of victory – after all, a larger army under the younger Cyrus had been crushed at Cunaxa in 401 despite the valor of the Ten Thousand (Xen. Anab. 1) – and underestimated both the Macedonian army and its youthful commander. Impatient and eager to force a decision upon an enemy he regarded as shirking battle, Darius entered Cilicia via the so-called Amanic Gates and placed himself astride Alexander’s lines of communication. By doing so, the Persian king abandoned the more extensive plains which offered him the chance of deploying the mobile troops that could most harm the enemy and negated his numerical superiority by leading his forces into the narrow coastal plain between the Gulf of Issus and the mountains.

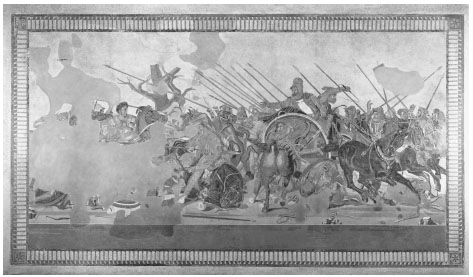

Figure 2.2 The Alexander Mosaic, from the House of the Faun, Pompeii. Museo Archeologico Nazionale, Naples. Photo: Scala/Art Resource, New York.

Alexander, who had advanced south of the Beilan Pass (Pillar of Jonah)21 and approached what would in the Middle Ages be known as Alexandretta (Iskenderum), now turned about to confront the Persian army, marching first in column and then spreading out to occupy the plain south of the Pinarus river. Despite his initial error in allowing himself to be lured onto a battlefield more favorable to the smaller Macedonian army, Darius made good use of the terrain, which he strengthened in one spot by means of a palisade. The Greek mercenaries gave a good account of themselves, as did the cavalry posted by the sea, but the battle was decided on the Persian left, where Alexander broke the Persian line and advanced directly upon Darius. The Great King was soon turned in flight, a move that signaled defeat and sauve qui peut. The slaughter was great, but the enemy leader escaped, ultimately, to the center of his empire to regroup and fight another day.22

The fortunes and paths of the two kings now moved in different directions. Darius returned to Mesopotamia, intent upon saving the heart of the empire and rebuilding his army. For this purpose, he summoned levies from the upper satrapies, which had not been called up in 333, perhaps from overconfidence that the victory would be easily won without them. Alexander meanwhile stuck doggedly to his strategy of depriving the Persian fleet of its bases and gaining control of the lands that supplied ships and rowers. For it was clear that most served Persia under compulsion and would defect once their home governments had acknowledged the power of the conqueror. Tyre proved a stubborn exception – not out of loyalty to Persia, but rather in hope of gaining true independence as a neutral state. But Alexander could not afford to leave so prominent and powerful an island city unconquered. The siege and capture of Tyre were one of the king’s greatest achievements and a monument to his determination and military brilliance. After seven months, the city succumbed to a combined attack of the infantry on the causeway, built with great effort and loss of life, and a seaborne assault on the weakest point of the walls. The king’s naval strategy was already paying dividends; for the Cypriot rulers had by now defected and joined with the other Phoenicians to blockade the Tyrian ships in their harbor, while a second flotilla carrying soldiers and battering rams gained undisputed access to the walls. The defenders repelled an attack after the initial breach was achieved, but they were soon overwhelmed and the city paid a heavy price for its defiance of Alexander.23

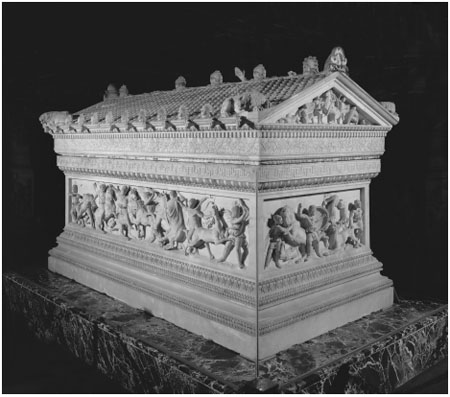

Figure 2.3 The Alexander Sarcophagus, late fourth century BC. Detail of a helmeted Alexander on horseback. Marble, 195 × 318 × 167 cm. Inv. 370T. Archaeological Museum, Istanbul. Photo: Erich Lessing/Art Resource, New York.

Figure 2.4 The Alexander Sarcophagus. View of the entire sarcophagus. Photo: Erich Lessing/Art Resource, New York.

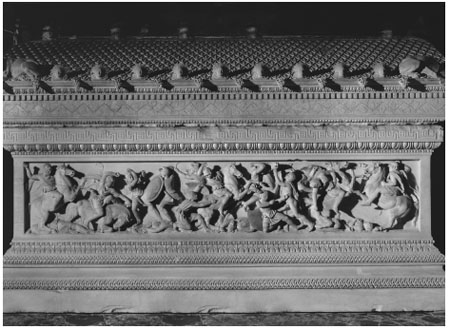

Figure 2.5 The Alexander Sarcophagus. View of the long battle side. Photo: Erich Lessing/ Art Resource, New York.

To the south, Gaza represented the final obstacle to the Macedonian strategy. It too was captured after a two-month siege. Its garrison commander, Batis, was allegedly dragged around the city by Alexander in imitation of Achilles’ punishment of Hector. This has generally been dismissed as fiction, though perhaps unjustly. The form of punishment and Alexander’s personal role may well be literary invention on the part of Cleitarchus, if not of Callisthenes of Olynthus, but there is a strong suspicion that behind this story there lurks an element of truth: Batis was doubtless subjected to cruel punishment for his opposition to Alexander (and we might add that Alexander was twice wounded in the engagement), just as later Ariamazes was crucified for his defiance.

In Egypt, the Macedonian army faced no resistance, since Persian authority in the satrapy had collapsed.24 If the populace welcomed Alexander as liberator, they did so out of hatred for Persia, which had harshly reintegrated Egypt into the Persian empire after roughly sixty years of independence under the kings of the Twenty-Eighth to Thirtieth Dynasties, and because, like the native populations of other regions, they were helpless to do otherwise. Alexander himself was recognized as the legitimate pharaoh – whether or not an official crowning took place in Memphis25 – and the earthly son of Amun, both in the Nile Delta and by the high priest of the god at Siwah in the Libyan Desert. Thus Egypt began a new era of foreign rule. The pharaonic titles were accepted by Alexander, just as they were conferred by his subjects, as recognition of the irresistible conqueror and his achievement. Neither side was truly deceived, but the process reaffirmed order and the continuation of the patterns of everyday life; for Alexander, like his Persian predecessors, would reside elsewhere and govern through satraps and nomarchs. The reality was clear to both Alexander and the Egyptians, but for the Macedonians Alexander’s new role and the nature of his relationship with Amun were deeply disturbing.

The journey to the oracle of Amun at Siwah in the Libyan Desert represents a critical point not only in Alexander’s personal development but also in the king’s relationship with his men – common soldiers and officers alike. Although there is a tradition that Alexander was “seized by an urge” (pothos) to visit the oracle and thus emulate his mythical ancestors, Perseus and Heracles, the journey cannot have been an impulsive act. Some have argued that the king sought divine approval for his new city on the Canopic mouth of the Nile. It is most likely that the journey was in some way connected with Alexander’s role as pharaoh, and such an interpretation finds curious support in Herodotus’ account of Cambyses. Certainly the story that the Persian king sent an army to destroy the shrine, and that this army was buried in the desert sands (Hdt. 3.26; Plu. Alex. 26.12), is as apocryphal as the one about his killing of the Apis calf – a patent fabrication that still commands the belief of some Classical scholars. The kernel of truth is surely that Cambyses consulted the oracle once he became master of Egypt. Whatever the fate of his envoys, the Herodotean account defies credulity. But Alexander must have known that, as pharaoh, he would be recognized as son of Amun. Whether the trip was made solely to consolidate his position in Egypt, or for a more ambitious purpose, cannot be determined. What is certain is that his men soon equated his acceptance of Amun as his divine father with a rejection of Philip (see Hamilton 1953). The first rumblings of discontent occurred before the army left Egypt; in the coming years, as the army made its weary progress eastward, Alexander’s apparent repudiation of his Macedonian origins was to become a recurring cause of complaint.

The conquest of the Levantine coast and Egypt had given Darius time to regroup. In 331 he moved his army from Babylon, keeping the Tigris river on his right and then crossing it south of Arbela, where he deposited his baggage. From here he marched north, bridging the river Lycus, and then encamped by the Boumelus (Khazir) in the vicinity of Gaugamela. As the Persian king was choosing his battle field, Mazaeus, who had once been satrap of Abarnahara (the land beyond the river), approached the Euphrates near Thapsacus with some 6,000 men. This force was far too small to prevent Alexander’s crossing and was probably intended to harass and observe the enemy, and Mazaeus quickly withdrew in the direction of the Tigris. Alexander, for his part, had been informed by spies about Darius’ location and the size of his army; at any rate, he had banished any thought of proceeding directly to Babylon, a move which would have created supply problems and allowed Darius to position himself astride his lines of communication for a second time. Furthermore, Alexander was eager for a decisive engagement.26

In 331, Darius was not Alexander’s only worry. During his second visit to Tyre, on the return from Egypt, the king received word of unrest in Europe, where the Spartan king Agis III had organized a coalition and defeated Antipater’s strategos in the Peloponnese, Corrhagus.27 Agis was besieging Megalopolis with an army of 22,000 just as Antipater was attempting to suppress a rebellion by Memnon, strategos of Thrace. Despite the timing, there is no good reason for suspecting that the uprisings were coordinated, or that Memnon had been in communication with Agis (paceBadian 1967). In fact, Antipater was able to come to terms with Memnon far too quickly for the Thracian rebellion to benefit Agis. Nor can the actions of the strategos have been regarded as treasonous; for the truce allowed him to retain his position, and Alexander appears to have taken no retaliatory action against him. Freed from distractions in the north, Antipater led his forces to Megalopolis and reestablished Macedonian authority with heavy bloodshed: 3,500 Macedonians lay dead, and 5,300 of the enemy, including Agis himself. But when Alexander confronted Darius at Gaugamela the affairs of Europe were only beginning to unravel.28

In his address to the troops, Alexander told them that they would be facing the same men they had defeated twice before in battle, but in fact the composition of the Persian army at Gaugamela was radically different and included the skilled horsemen of the eastern satrapies. And, this time, the Persians would be fighting on terrain of their own choosing. With vastly superior numbers, Darius expected to outflank and envelop the much smaller Macedonian army, which numbered only 47,000. Furthermore, the Macedonians were confronted by scythe chariots and elephants. But the Macedonians advanced en echelon, with the cavalry on the far right wing deployed to prevent an outflanking maneuver there; behind the main battalions of the pezhetairoi, Alexander stationed troops to guard against envelopment. By thrusting with his Companions against the Persian left, Alexander disrupted the enemy formation as the heavy infantry surged ahead to strike at the center. But in so doing, the infantry created a gap, which the Scythian and Indian horsemen were prompt to exploit. But the barbarians rode straight to the baggage of the field camp, eager for plunder and acting as if their victory was assured. Had they struck instead at the Macedonian left, where Mazaeus was putting fearsome pressure on the Thessalian cavalry under Parmenion’s command, they might have turned the tide of battle. Instead they were soon following their king in flight, struggling to escape the slaughter that emboldens the victor.

Defeat at Gaugamela left the heart of the empire and the Achaemenid capitals at the mercy of the invader. Mazaeus, who had fled to Babylon, now surrendered the city and its treasures to Alexander, thus earning his own reward. The king retained him as satrap of Babylonia, though he took the precaution of installing Macedonian troops and overseers in the city. The administrative arrangements, like the ceremonial handing over of the city, were the same as those at Sardis, except that at that uncertain time Alexander was not yet ready to entrust the Iranian nobility with higher offices. In Susa, the king confirmed the Persian satrap Abulites, who had made formal surrender after Gaugamela: but again native rule was fettered by military occupation as its Persian commandant Mazarus was replaced by the Macedonian Xenophilus.29

In the closing months of 331, anxiety about Agis’ war in the Peloponnese helped to buy the Persians time. The need to await news of events in the west kept Alexander in Babylonia and Elam longer than he had planned, a delay exploited by the Persian satrap, Ariobarzanes, who occupied the so-called Persian Gates30 with an army of perhaps 25,000 (40,000 infantry and 700 horse, according to Arrian 3.18.2). But his efforts, like those of the Uxians shortly before, proved futile. Alexander circumvented the enemies’ position and was soon reconstructing the bridge across the Araxes, which the Persians had destroyed in an effort to buy time. Perhaps the intention was to facilitate the removal or even the destruction of the city’s treasure; for the best Ariobarzanes could do was delay Alexander’s force while Parmenion took the heavier troops and the siege equipment along the more southerly wagon road to Persepolis. But no such measures were taken, and Tiridates surrendered the city and its wealth to the conqueror.

Vengeance had been the theme exploited, first by Philip and then by Alexander, and the war against Persia the justification for allied service under the Macedonian hegemon. The mandate of the League could be enforced before the troops even reached Asian soil. Thebes, which had a long history of Medism, was accused once again of collaboration with Persia, and indeed of advocating alliance with the Great King to overthrow the tyrant who was oppressing Greece, Alexander (D.S. 17.9.5). The city’s destruction was at once an act of terror and vengeance. On similar grounds, Parmenion had destroyed Gryneium on the Aegean coast and enslaved its population.31 And, not surprisingly, Alexander’s propagandists depicted the crossing into Asia as the beginning of another chapter in the ongoing struggle between east and west. The king sacrificed to various gods and heroes associated with the Trojan War, including an apotropaic sacrifice to Protesilaus, the first of the Achaeans to leap ashore and to meet his fate there. Thereafter he hurled his spear into Asian soil, and leaping onto the Asian shore, proclaimed it “spear-won land.”32 The message was unmistakable: more than a mere punitive expedition, this was to be a war of conquest, and it was to be a Panhellenic effort.33 But Alexander had no sooner embarked on this fine-sounding mission than it became clear to him that propaganda and expediency were destined to clash. Slogans might prove useful for the enlistment of troops or creating ardor among the rank and file, but victory over the enemies’ military forces did not guarantee the political acquiescence of the conquered peoples.

Hardly had he consigned Greeks who had served as mercenaries of the Great King to hard labor camps, for their collaboration with the enemy, before he accepted the surrender of Sardis by the Persian Mithrenes, whom he treated with respect and kept in his entourage. It was a clear indication of what could be accomplished without recourse to battle, and the friendly treatment of the defector would induce others to follow his example. In the same campaigning season, Alexander dismissed the allied fleet. Militarily and economically, this was a good move, but the political implications were otherwise. The leader of the League of Corinth had rejected the participation of one of its most powerful members. Furthermore, he followed this gesture with an equally confounding one when he allowed Ada to return to Halicarnassus as its rightful queen and accepted her as his adoptive mother. From the very beginning, Alexander had recognized that he might conquer without reaching an accommodation with the barbarian, but he would do so more easily and rule the empire more securely if he did so. Hence, the orientalizing tendencies of the king, which were to cause so much anxiety in the years that followed Darius’ death, were already in evidence in 334/3. But Alexander was doing little more than applying the methods of Philip to the Asiatic sphere.

For the conservative Macedonians and Greeks, it was a disturbing trend, but Alexander’s progressive moves reveal a political talent that rivaled his military genius. No opportunity was wasted. The decision to send the newly-weds back to Macedonia, where they could kindle the enthusiasm of their countrymen for the war and return with reinforcements, was a fine public relations exercise, to say nothing of its impact on the Macedonian birth rate. In spring 333, Alexander was quick to exploit the prophecy of the Gordian knot, even if his rashness forced him to find a desperate solution. After the king’s death there were those who said that he had cheated by cutting the knot with his sword, but no one said so at the time. The respectful treatment of the Persian women captured at Issus showed that Alexander was the consummate master of propaganda, whether it was directed toward the Greeks, the Macedonians, or the barbarians. Not every victory would be gained on the battlefield. So much was clear to the young conqueror, although the soldiers and the majority of their commanders failed to appreciate their leader’s approach. Whatever political advantages accompanied the king’s recognition as “Son of Amun,” the troops saw only the rejection of Philip II and the inflated ego of a man to whom success came too soon and too easily.

It would indeed be easy to reduce the king’s actions to those of a young man corrupted by fortune; for thus he is represented in some of the extant accounts. But this is to deny Alexander an awareness of the political reality. He more than anyone understood that the rhetoric which had fueled the campaign in the first place must give way to a policy of rapprochement if the fruits of his military successes were not to be squandered. Nevertheless, he was prepared to employ different forms of propaganda in his dealings with two conflicting groups – the victors and the vanquished. But, when the fighting stopped, the consequences of this studied duplicity would confront him.

In truth, that confrontation occurred even before the war was officially ended. The flight of Darius from Gaugamela and the surrender of Babylon and Susa made Alexander de facto ruler of the Persian empire. Although one final attempt was made to impede the king’s progress at the Persian Gates, the capture of Persepolis was more or less symbolic. Indeed, for the Greeks, the entry into the city was, like that of the armies of the First Crusade into Jerusalem in 1099, the culmination of the campaign and the fulfillment of the purpose for which they had crossed into Asia. But for Alexander it was a public relations nightmare. As long as Darius lived and continued to be recognized as Great King, the war remained unfinished and the eastern half of the empire unconquered. Greek allies, mindful of the League’s propaganda, demanded the destruction of the city in the hope of sating their hunger for revenge and booty. Victorious and laden with spoils, they expected to be demobilized. To deny the soldiers of League, as well as his Macedonian veterans, the right to plunder would be a failure to acknowledge their sacrifices, but Parmenion rightly advised that Alexander should not destroy what was now his (Arr. 3.18.11). Hence the king compromised, allowing his troops to pillage while still reserving the greatest treasures for himself; for even in the suburbs there were enough spoils to go around. But, if the destruction of the palace was an act of policy, it was an unfortunate miscalculation. Alexander may have attempted to limit the physical destruction while satisfying the expectations of the Greeks back home; the symbolism of the act was, however, seared into the hearts of Iranians for centuries.34

In vain Darius summoned reinforcements from the upper satrapies, despite the fact that Alexander was delayed at Persepolis awaiting news of the outcome of Agis’ war and the clearing of the passes through the Zagros. When in May 330 Alexander finally crossed the Zagros into Media, Darius had little choice but to retreat to the solitudes of Central Asia, following the caravan route (later to be known as the Silk Road) that led from Rhagae through the Caspian Gates (the Sar-i-Darreh pass) between the Great Salt Desert and the Elburz mountains. But the cumbersome train of women and eunuchs, and the other impedimenta of royalty, made slow progress, while Alexander closed the distance between himself and his prey. Darius thus felt compelled to decide the matter in battle, with an army that had dwindled to fewer than 40,000 barbarian troops and 4,000 Greeks. And these lacked the fighting spirit or the leadership to decide the matter on the battlefield: Bessus, satrap of Bactria and Sogdiana, and the chiliarch Nabarzanes were intent upon flight to Bactra (Balkh), where new forces could be enlisted for a guerrilla war against Alexander; Darius had lost all authority. He was arrested and placed in chains, allegedly of gold, as if to mitigate the crime, and his remaining followers slipped away to make submission to the advancing conqueror. Finally, in a vain hope of buying time or winning Alexander’s goodwill, the conspirators murdered their king and left him by the roadside. Arrian dates Darius’ death to the month Hecatombaeon in the archonship of Aristophon, that is, July 330 (Arr. 3.22.2; Bosworth 1980b: 346 suggests a miscalculation and postpones the event to August). Not long after, Alexander reached Hecatompylus and dismissed the remainder of his allied troops. The pressure to declare an end to the Panhellenic war had been mounting since the fall of Persepolis, and some forces had been sent home from Ecbatana. Despite the loss of the allied contingents, there was still a ready supply of mercenary soldiers and regular reinforcements from Macedonia and Thrace. Furthermore, since the king was anxious to bring about an accommodation with the Persian aristocracy, and indeed to present himself as the legitimate successor of Darius III, it was necessary to abandon the slogans of Panhellenism and vengeance.

Those who supported Bessus hastened in the direction of the Merv Oasis and the upper satrapies of Bactria and Sogdiana. Others, however, rejected Bessus and his clique. Bagisthanes, Antibelus (or, as Curt. 5.13.11 renders the name in Latin, Brochubelus) son of Mazaeus, and Melon, the king’s interpreter, had surrendered even before the conspirators seized Darius. Now, upon Bessus’ usurpation, the number and importance of these defectors increased: Phrataphernes, Autophradates, Artabazus and his sons, all found their way to Alexander’s camp. The king did not disappoint them, assigning to Phrataphernes the rule of the Parthians, and Autophradates the Tapurians. Artabazus and his sons remained with Alexander – he had known them since they had taken refuge at Philip’s court, and would reward them later. Even the regicide Nabarzanes surrendered to Alexander and was pardoned through the efforts of the younger Bagoas, an attractive eunuch who found favor with Alexander.35 Perhaps he lived out his life in obscurity, although it is possible that the “Barzanes” who attempted to gain control of Parthia and Hyrcania, and was subsequently arrested and executed, was in fact the former chiliarch.36

It soon became known that the regicide Bessus had assumed the upright tiara and styled himself Artaxerxes V, and it is perhaps no mere coincidence that Alexander adopted Persian dress at about the same time (Plu. 45.1–3). At Susia (Tus), Alexander accepted the surrender of Satibarzanes, whom he confirmed as satrap of the Areians and sent back to his satrapy (in the vicinity of modern Herat) accompanied by forty javelin men under Anaxippus. These were soon butchered by Satibarzanes’ forces and Alexander, who had set out for Margiana, was forced to divert his army to Artacoana. Caught off-guard by the suddenness of his arrival, the treacherous satrap fled to Bactria with 2,000 horsemen, but he soon returned to challenge the Persian Arsaces, whom Alexander had installed in his place. Not much later, Satibarzanes was killed in single combat with Erigyius.

Alexander himself followed the Helmand river valley eastward in the direction of Arachosia. On the way, he encountered the Ariaspians, a people known also as the “Benefactors” (euergetae) for the aid they gave Cyrus the Great in the 530s; now they provisioned another great conqueror over the winter of 330/29. In Arachosia, in the vicinity of modern Kandahar (but see Vogelsang 1985: 60 for pre-Alexandrian settlement), the king founded yet another Alexandria in the satrapy abandoned by the regicide Barsaentes, whom Sambus now sheltered. The Macedonians then entered Bactria via the Khawak Pass, which led to Drapsaca (Qunduz). Their speed and determination were beginning to take a toll on the barbarian leaders, who sought reprieve by surrendering Bessus. The regicide was arrested, stripped naked, and left in chains to be taken (by Ptolemy) to Alexander, but the conspirators who betrayed him were not yet ready to test the conqueror’s mercy.

The punishment of Bessus – Alexander sent him back to Ecbatana to be mutilated in Persian fashion (which involved cutting off the ears and nose) and then executed – should have ended the affair. But the northeastern frontier was unstable, and the semi-nomadic peoples there were inclined to trust the vastness of its open spaces and its seemingly unassailable mountain fortresses. Furthermore, Alexander’s campaign to the Iaxartes, and the establishment of Alexandria Eschate to replace the old outpost of Cyropolis, threatened the old patterns of life and trade in Sogdiana.37 Hence the local dynasts, Spitamenes, Sisimithres, Oxyartes, Arimazes, took up the fight, and two years of guerrilla warfare followed before the political marriage of Alexander and Oxyartes’ daughter, Roxane, could bring stability to the region.

Alexander’s treatment of Bessus had perhaps sent the wrong message: the rebels should expect no clemency from the conqueror. Invited to a council at Bactra (Zariaspa), the chieftains of Bactria and Sogdiana suspected treachery and renewed their opposition. Spitamenes, perhaps an Achaemenid, emerged as the leader of the resistance, striking at Maracanda while Alexander carried the war beyond the Iaxartes. Next he caught the force sent to relieve the town in an ambush at the Polytimetus, inflicting heavy casualties and inspiring the natives’ hopes. But the following year, he was hemmed in by the contingents of Craterus and Coenus and eventually betrayed by his Scythian allies, who sent his head to the Macedonian camp while they themselves made good their escape into the desert.

In the late autumn of 328, large numbers of rebels and their families took refuge with Sisimithres on the so-called “Rock of Chorienes,” now known as Koh-i-nor,38 frighteningly high and of even more imposing circumference and surrounded by a deep ravine. But Alexander induced his surrender through the agency of Oxyartes, who must have defected to the Macedonians in the hope of saving his family. By his voluntary submission Sisimithres averted a fate similar to that of Ariamazes, and he was allowed to retain his territory (probably the region of Gazaba), although his two sons were retained as hostages in Alexander’s army. In early 327, Sisimithres was able to provision Alexander’s army with supplies for two months, “a large number of pack-animals, 2000 camels, and flocks of sheep and herds of cattle” (Curt. 8.4.19). Alexander repaid the favor by plundering the territory of the Sacae and offering Sisimithres a gift of 30,000 head of cattle. It was almost certainly at this point that the banquet at which Roxane was introduced to Alexander occurred, and the king took his first oriental bride.

Alexander had never entirely trusted mercenaries – perhaps he had bitter memories of their betrayal of Philip (Curt. 8.1.24) – and he found it convenient to settle not fewer than 10,000 of them in military outposts beyond the Oxus (Amu-darya). The king had, of course, founded numerous “cities” throughout the east – several, though not all, named for himself – and would continue to do so in India: Plutarch (Mor. 328e = de fort. Al. 1.5) speaks of more than seventy, but many of these involved either the resettling of old cities (e.g., Alexandreia Troas, or Prophthasia at Phrada, modern Farah) or the establishment of military colonies (katoikiai), though some twelve to eighteen Alexandreias deserve serious attention.39 In Bactria and Sogdiana, the short-term prognosis for these settlements was not good: for the mercenaries felt abandoned in the solitudes of Central Asia and, prompted by the false news of Alexander’s death in India, considered a bold escape to the west – thus imitating on a grander scale the achievement of the Ten Thousand – but the plan was suppressed in 326/5 and again, with great slaughter, in 323/2.40 Paradoxically, Bactria and Sogdiana were destined to become an outpost of Hellenism between the Mauryan kingdom in the east and the Parthians in the west.

The opposition to Alexander that manifested itself at the time of Philip’s death had been silenced by swift and decisive measures, but the opponents remained. In the first year of the Asiatic campaign, the king found evidence of secret negotiations between Alexander Lyncestes and representatives of the Great King. In winter 334/3, the Lyncestian was arrested on information divulged by a Persian agent named Sisenes (Arr. 1.25). The theory that he had not been in treasonous contact with the chiliarch Nabarzanes and the exile Amyntas son of Antiochus, but was himself the victim of conspiracy devised by Alexander (thus Badian 2000a), is unconvincing (see Heckel 2003b). At the time, however, Alexander’s position was far from secure, and he was reluctant to test the loyalty of Antipater by executing his son-in-law. The Lyncestian was nevertheless kept in chains for three years before being brought to trial.

Further dissatisfaction resulted from the king’s acceptance of his “divine birth” at Siwah. For the conquest and administration of the satrapy, Alexander’s recognition by the priests of Amun was a political expedient. But the subtleties of politics were wasted on the conservative Macedonian aristocracy, which had grown to regard its king as first among equals. Like the king’s later orientalisms, the decision to exploit native sentiment was regarded by the conquerors as a demotion of the victors and their practices. Hegelochus, perhaps a relative of Philip’s last wife Cleopatra, appears to have plotted against the king in Egypt, but the plan came to naught and was disclosed only in 330, more than a year after the conspirator’s death at Gaugamela. Philotas had also voiced his displeasure in Egypt, treasonous activity for a lesser man. His claim that Alexander’s military success was due primarily to Parmenion’s generalship did not sit well with the son of Philip of Macedon, perhaps because there was some truth in it. Before the final decision at Gaugamela, the remark was ignored but not forgotten. The echo of Philotas’ boast would resound in Phrada in 330, when Parmenion had been left behind in Ecbatana.

In Alexander’s camp there now occurred the first open signs of opposition to the king’s authority and policies (see also ch. 4). The so-called “conspiracy of Philotas” in the autumn of 330 was, if anything, an indication that some of the most prominent hetairoi had begun to question Alexander’s leadership. At that time, a relatively unknown individual named Dimnus either instigated or was party to a conspiracy to murder the king. The details of this plot he revealed to his lover Nicomachus, and by him they were transmitted to Nicomachus’ brother Cebalinus and ultimately to Alexander himself. Philotas’ role is at best obscure: what we do know is that Cebalinus reported the plot to him and that he did not pass it on, later alleging that he did not take it seriously. He could perhaps point to the humiliation endured by his father, Parmenion, who falsely accused Philip of Acarnania of planning to poison the king in Cilicia. But the fact remains that Philotas was already on record as having made boastful remarks which exaggerated his own achievements, and those of his father, and cast aspersions on Alexander’s generalship (Arr. 3.26.1; Plu. Alex. 48.1–49.2 provides the details). That this occurred in Egypt, after Alexander’s acceptance of his role as “Son of Amun,” is significant; for it is a clear sign of how the orientalizing policies of the king were alienating the conservative commanders of the army. Hegelochus son of Hippostratus, as has been noted, harbored treasonous ambitions at this time (Curt. 6.11.22-9). Furthermore, in the deadly world of Macedonian politics, where assassination was a regular and effective tool, it was easily believed that anyone who knowingly suppressed knowledge of a conspiracy must in some way have approved of it. This, at least, was the substance of the charge against Philotas and, combined with his previous record of disloyalty, it was sufficient to bring about his condemnation and execution. Alexander nevertheless was careful to give the impression of legality to his actions, for he knew that the execution of the son would have to be followed by the father’s murder. Charges were laid against Parmenion, and Polydamas the Thessalian was sent in disguise to Ecbatana, where the murder was carried out swiftly by men Alexander felt he could trust.41

The deaths of Philotas and his father gave Alexander the opportunity to eliminate Alexander Lyncestes, who, if he was no longer a danger to the king, remained a political embarrassment. Antipater appears not to have protested against the imprisonment of his son-in-law, and the king, who had now become truly the master of his growing domain, felt secure enough to execute the traitor. A lengthy incarceration will have given the Lyncestian time to rehearse a defense, but the hopelessness of his position rendered him confused and all but speechless.

The elimination of Philotas required a restructuring of the command of the Companion Cavalry. The king had learned that it was unwise to entrust so important an office to a single individual, and his solution was designed to limit the power of the hipparch while making conciliatory gestures to the old guard. Philotas’ command was thus divided between Black Cleitus, who had saved the king’s life at the Granicus and whose sister had been Alexander’s wet nurse, and the untried but unquestionably loyal Hephaestion. The latter appointment proved to be not merely a case of nepotism but an unsound military decision, and within two years the Companions were divided into at least five hipparchies, of which only one remained under Hephaestion’s command.

The strain of combat and campaigning under the harshest conditions took its toll on soldiers and commanders alike. In summer 328, at a drinking party in Maracanda, the stress of combat mixed with personal resentment and political outlook into a deadly brew. The event that precipitated a quarrel between Alexander and Black Cleitus, the former commander of the “Royal Squadron” (ile basilike) of the Companion Cavalry, was, on the face of it, innocent enough. A certain Pierion or Pranichus, who belonged to the king’s entourage of artists, recited a poem that appears to have been a mock epic about one of their own – the harpist Aristonicus (see Tritle, ch. 7) – who died in battle against Spitamenes.42 But the veteran warrior, Cleitus, took umbrage and faulted Alexander for allowing Greek nonmilitary men to ridicule a Macedonian defeat at a function that included barbarians. And we must assume that there were greater issues at play: Cleitus had watched Alexander’s transformation from a traditional Macedonian ruler to an orientalizing despot with disapproval, and the argument that ensued was as much a clash of generations and ideologies as the machismo of two battle-scarred veterans under the influence of alcohol.

The underlying tensions were not to subside. If anything, the marriage of Alexander to Roxane in winter 328/7, which had done so much to reconcile the barbarians with their conquerors, proved immensely unpopular with the army and its commanders – even more so, if there is any truth to claim that Alexander arranged for similar mixed marriages between his hetairoi and Bactrian women (Metz Epit. 31; D.S. 17 index λ). Furthermore, the king’s attempt to introduce the Persian practice of obeisance known asproskynesis at the court, for both barbarians and Macedonians, not only proved a dismal failure but increased the alienation of the Macedonian aristocracy.

Many scholars have seen Alexander’s unsuccessful experiment with proskynesis as a thinly veiled demand for recognition of his divine status. This is, however, highly unlikely; for the Greeks themselves knew that the Great King was never regarded as divine and that proskynesis was merely part of the court protocol. That they considered it an inappropriate way of addressing a mortal ruler is another matter. If hostile sources chose to equate Alexander’s adoption of the practice with a request for divine honors, that was a misinterpretation – either deliberate or unintentional – of the king’s motives. (In view of his later demands, this is not entirely surprising.) Furthermore, the claim that proskynesis required the Macedonians to prostrate themselves before their king is equally nonsensical. Herodotus, in a famous passage concerning the practice (1.134.1), makes it clear that the extent of debasement was directly proportional to the status of the individual and was not restricted to the greeting of the Great King (see also Xen. Anab. 1.6.10). If Macedonians like Leonnatus ridiculed the Persians for abasing themselves, it demonstrates merely that the conquered peoples approached their new sovereign as suppliants, thus humbling themselves before Alexander in a way that would not have been required of them at the court of Darius, where the hierarchy was clearly established. The position of Persian nobles at the court of Alexander was yet to be determined and obsequious behavior was a form of self-preservation. By contrast, Alexander would have required of his hetairoi little more than a kiss on the lips or the cheek, and it is perhaps a misunderstanding of this practice that led contemporary historians to claim that Alexander gave a kiss to hishetairoi only if they had previously performed proskynesis, when in fact the kiss and the proskynesis were synonymous. What is certain, however, is that the ceremony, which was intended to put the Persian and Macedonian on a roughly equal footing (Balsdon 1950: 382), and which suited Alexander’s new role as Great King, was rejected by the Greeks and Macedonians, and that Callisthenes of Olynthus was among the most vocal of those who voiced their objections. Nor is it difficult to understand that the nobles who had long regarded their ruler as primus inter pares would be reluctant to acknowledge that they, like the conquered enemy, were now “slaves” (douloi) of the Great King.

The extent of the alienation can be seen in the so-called “Conspiracy of the Pages.” The plot had its origins in a personal humiliation: Hermolaus son of Sopolis, while hunting with the king, had anticipated Alexander in striking a boar, an act of lèse-majesté.43 For this he was flogged. But the view that he plotted to murder the king in order to avenge this outrage is simplistic, and it was recognized even at the time that there were larger issues at play. The Pages were the sons of prominent hetairoi, and their hostility toward Alexander was doubtless a reflection of the Macedonian aristocracy’s reaction to his policies. The conspiracy itself came to naught: Eurylochus, a brother of one of the Pages, brought the news of the plot to the somatophylakes Ptolemy and Leonnatus, and the conspirators were arrested, tried, and executed. But the episode revealed once again the extent of disaffection among the Macedonian aristocracy. The elimination of the conspirators also gave Alexander the opportunity of ridding himself of Callisthenes (Aristotle’s nephew), the official historian who, over the course of the campaign, had developed too sharp a tongue for the king’s liking and played no small part in sabotaging the introduction of proskynesis. As tutor of the Pages, he could be held responsible for their political attitudes, and, although there was no clear evidence to incriminate him, the suspicion of ill-will toward the king was sufficient to bring him down. If the king’s friendship with Aristotle, perhaps already strained, mattered, he may indeed have intended to keep Callisthenes in custody until his fate could be decided by a vote of the League of Corinth. The conflicting stories of the nature of his death reflect at least two layers of apologia. In the version given by Ptolemy, he was tortured and hanged, a punishment at once barbaric and appropriate to traitors (Arr. 4.14.3; Bosworth 1995: 100); Chares of Mytilene says that he was incarcerated for seven months and died of obesity and a disease of lice (see Africa 1982: 4) before he could stand trial (Plu. Alex. 55.9 = Chares, FGrHist 125 F15).

In spring 327, Alexander recrossed the Hindu Kush and began his invasion of India, the easternmost limits of the Achaemenid empire. The extent of Persian rule in Gandhara and the Punjab had doubtless declined since the age of Darius I, but the response of the local dynasts to Alexander’s demands for submission shows that they continued to recognize some form of Achaemenid overlordship (hence Arrian’s use of the term hyparchoi), that is, they regarded Alexander’s authority as legitimate (see Bosworth 1995: 147–9). Not all came over willingly. In Bajaur, the Aspasians, who dwelt in the Kunar or Chitral valley, fled to the hills after abandoning and burning Arigaeum (Nawagai); nevertheless the Macedonians captured 40,000 men and 230,000 oxen. More obstinate was the resistance of the Assaceni, who fielded 2,000 cavalry, 30,000 infantry, and thirty elephants. After the death of Assacenus, who may have been killed in the initial skirmish with Alexander, Massaga in the Katgala Pass relied for its defense on Cleophis, the mother (or possibly widow) of Assacenus. Soon Cleophis sent a herald to Alexander to discuss terms of surrender, gaining as a result the reputation of “harlot queen”; for she was said to have retained her kingdom through sexual favors (Just. 12.7.9–11). The story that she later bore a son named Alexander is perhaps an invention of the late first century and an allusion to Cleopatra VII and Caesarion.44 Ora (Udegram) and Beira or Bazeira (Bir-kot), other strongholds of the Assaceni, fell in rapid succession. But a more strenuous effort was required to capture the rock of Aornus, which abutted on its eastern side the banks of the Indus river. Hence, it is probable that its identification with Pir-Sar by Sir Aurel Stein is correct, though recently others have suggested Mt. Ilam.45

In the mean time, the king had sent an advance force to bridge the Indus and secure Peucelaotis (modern Charsadda) with a Macedonian garrison. Ambhi (whom the Greeks called Omphis or Mophis), the ruler of Taxila – the region between the Indus and the Hydaspes – had already sent out diplomatic feelers to Alexander and he now welcomed the Macedonian army near his capital (in the vicinity of modern Islamabad); for he was prepared to exchange recognition of Alexander’s overlord-ship for military help against his enemies, Abisares and Porus, who ruled the northern and eastern regions respectively. In return for Macedonian support, Philip son of Machatas was appointed as overseer of the region, with Ambhi (under the official name of “Taxiles”) as nominal head of the kingdom.

Abisares had known of Alexander’s advance since at least winter 327/6, when he sent reinforcements to Ora. After the fall of Aornus in 326, natives from the region between Dyrta and the Indus fled to him, and he renewed his alliance with Porus. Though clearly the weaker partner in this relationship, Abisares could nevertheless muster an army of comparable size; hence Alexander planned to attack Porus before Abisares could join forces with him. In the event, Porus looked in vain for reinforcements, as Abisares made (token?) submission to Alexander and awaited the outcome of events. After the Macedonian victory at the Hydaspes, Abisares sent a second delegation, led by his own brother and bringing money and forty elephants as gifts. Despite his failure to present himself in person, as had been required of him, Abisares retained his kingdom, to which was added the hyparchy of Arsaces; he was, however, assessed an annual tribute and closely watched by the satrap, Philip son of Machatas. Although Abisares is referred to as “satrap” by Arrian, his son doubtless followed an independent course of action after Alexander’s return to the west.

Porus meanwhile prepared to face the invader and his traditional enemy, Taxiles, at the Hydaspes (Jhelum), probably near modern Haranpur.46 Here, Alexander positioned Craterus with a holding force directly opposite Porus and stationed a smaller contingent under Meleager and Gorgias farther upstream; he himself conducted regular feints along the river bank before marching, under the cover of night and a torrential downpour, to ford the river some 26 km north of the main crossing point, catching Porus’ son, who had been posted upstream, off his guard. This was near modern Jalalpur and the wooded island of Admana. The main engagement was a particularly hard-fought and bloody one,47 in which the Indian ruler distinguished himself by his bravery. The valiant enemy earned Alexander’s respect, and was allowed to retain his kingdom. It had not always been so: Alexander had not always been so generous in his treatment of stubborn adversaries. The greater challenge lay, however, in the attempt to bring about lasting peace between the Indian rivals. Curtius claims that an alliance between Taxiles and Porus was sealed by marriage, the common currency in such transactions. But the arrangement was never entirely satisfactory. Though Taxiles was perhaps more to be trusted than Porus, Alexander needed a strong ruler in what would be the buffer zone at the eastern edge of his empire (see Breloer 1941).

Despite the popular view of Alexander as a man obsessed with conquest and intent upon reaching the eastern edge of the world – a view which will persist because the legend of Alexander has become so firmly rooted that it defies all rational attempts to change it – Alexander abandoned thoughts of acquiring new territory after his hard-fought victory over Porus. What he needed now was security, and he worked with his new ally himself to bring the neighboring dynasts under Porus’ authority. The Glausae were reduced by Alexander and their realm added to that of Porus, while Hephaestion annexed the kingdom of the so-called “cowardly” Porus, between the Acesines (Chenab) and Hydraotes (Ravi) rivers. Garrisons were established in the region, but they comprised Indian troops and were responsible to Porus, not Alexander. Beyond the Ravi, the campaigns were either punitive or preemptive, depending on how Porus in his discussions with the king assessed their power or reported their activities. Sangala, indeed, was stubborn in its resistance, and the attackers paid a heavy price in casualties; but Sophytes (Saubhuti) made peace, perhaps relieved by the conqueror’s suppression of the neighboring Kshatriyas.

Nevertheless, the Hyphasis (Beas) marked the end of the eastward march – and Alexander knew it. He had, in truth, already determined to take the army elsewhere. After the victory at the Hydaspes, the king had established two cities, Bucephala and Nicaea, as outposts of his realm, and sent men into the hills to cut down trees for the construction of a fleet that would sail down the Hydaspes to the Indus delta, thus following a route known to the Greeks since the exploits of Scylax of Caryanda during the reign of Darius I (Hdt. 5.44). His reasons for campaigning in the eastern Punjab were simple and practical enough. It was essential that Porus should control a strong vassal kingdom on the edge of Alexander’s empire, and it was important to keep the men occupied and to place the burden of feeding his troops on the hostile tribes in that region rather than on his newly acquired friend Porus. Alexander’s behavior at the Hyphasis, when he withdrew into his tent and sulked because his troops would not follow him to the Ganges, was as a much an act of dissembling as the larger-than-life structures that were erected at the river, designed to deceive posterity into thinking that the Macedonian invaders had been more than mere humans.48

For Alexander the path to the Ocean was still open, but the need to secure the empire was not forgotten: the descent of the Indus waterway, conducted by land as well as on the river, shows that Alexander intended a systematic reduction of the area which would insure Macedonian rule in the Punjab (Breloer 1941). The expedition was a show of force on the eastern side of the Indus to support Macedonian claims to rule the western lands adjacent to the river (Bosworth 1983). The Sibi, allegedly descendants of Heracles, were woven into the fabric of the Alexander legend more securely than into that of the empire. The Kshudrakas (Oxydracae or Sudracae) and Malavas (Mallians) were deadly foes and long-time enemies of both Porus and Abisares. The sack of one of their towns – probably located at or near modern Multan (Wood 1997: 199-200) – nearly cost the king his life, and from this point, he was conveyed downstream by ship, displayed to the troops, in an attempt to stifle rumors that he had died and the “truth” was being kept from them by the generals.

When the king recovered his strength, he turned his attention to Musicanus, whose kingdom beyond the confluence of the Chenab is probably to be identified with ancient Alor. Musicanus, surprised by the enemy’s approach, surrendered and accepted a garrison. But Oxicanus (or Oxycanus), a nomarch of upper Sind (Eggermont 1975: 12 locates him at Azeika), resisted the invader and was eventually captured and, presumably, executed. Porticanus, ruler of Pardabathra, suffered a similar fate, but the arguments for identifying the two rulers as one and the same, as many scholars do (Smith 1914: 101 n. 3; Berve ii. 293), are not compelling (Eggermont 1975: 9–10, 12). At Sindimana, the capital of the dynast Sambus, whom Alexander had appointed satrap of the hill country west of the Indus, the inhabitants opened their gates to receive the Macedonians, but Sambus himself fled. Musicanus, too, on the advice of the Brahmans, had rebelled soon after the king’s departure, only to be hunted down by Peithon son of Agenor and brought to Alexander, who crucified Musicanus and other leaders of the insurrection. What became of Sambus we do not know, but Craterus’ return to the west through the Bolan Pass may have been intended to root out the remaining insurgents; for it appears that Sambus controlled the profitable trade route between Alor and Kandahar (Eggermont 1975: 22).

From Sind, Alexander explored the area of Patalene and the Indus delta before sailing into the Indian Ocean, where he sacrificed to the same sea deities whom he had propitiated at the Hellespont. But the road home, through the lands of the Oreitae and the Gedrosian desert (for the route: Stein 1943; Strasburger 1952; Engels 1978a: 135-43; Seibert 1985: 171-8; see Hamilton 1972 for the Oreitae), would be a hard one, especially for the ill-provisioned camp followers who had swollen the numbers of the Macedonian army. But the march was necessary if the king was to keep in contact with Nearchus’ fleet, which had been instructed to sail from the delta to the straits of Hormuz (for early travel from the Persian Gulf to India, see Casson 1974: 30–1, 45) and ultimately to the mouth of the Tigris; for at that time the river flowed directly into the sea, rather than joining the Euphrates, as it does today. The privations of the army were aggravated by the failure of certain satraps to provide the requisitioned supplies. The king’s angry gesture of tossing Abulites’ coins at the feet of his horses (Plu. Alex. 68.7) may suggest that the satrap had sent money instead of provisions. Nevertheless, Alexander reunited with Nearchus in Carmania and later again at the Tigris. The infamous Dionysiac procession, accepted or rejected by scholars (according to their personal views of Alexander) as evidence of his degeneration, may have been nothing more than well-deserved “R & R” for the troops (Tarn i. 109, typically, “a necessary holiday which legend perverted into a story of Alexander. . . reeling through Carmania at the head of a drunken rout”).

Alexander’s lengthy absence in Central Asia and the Indus valley had raised doubts about whether he would return, and in the heartland of the empire the administration of the lands and treasures was conducted with little regard for the king’s pleasure or the empire’s well-being. Among the worst offenders was Harpalus, the treasurer who had moved his headquarters from Ecbatana to Babylon, where he lavished gifts and titles upon first one Athenian courtesan, Pythionice, and after her death another, Glycera. Other charges against him involved sexual debauchery and illegal treatment of the native population. When he learned of Alexander’s reemergence from India, Harpalus fled westward, first to Cilicia and then on to Athens, taking with him Glycera and no small amount of the king’s treasure. But Harpalus was only the most famous of the offenders and perhaps the most sensational in his offenses. Others were quickly called to account, tried, and in many cases deposed or executed. One scholar has labeled the actions a “reign of terror” (Badian 1961) and the phrase is now employed by many scholars as a convenient shorthand for the events that followed the king’s unexpected return from the east. Alexander’s restoration of order is frequently interpreted as abuse of power, and criminals as “scapegoats,” and not all were executed or deposed from office. It is hardly surprising that the king, after a lengthy absence, should conduct an investigation into their affairs.49

The house cleaning was accompanied by further orientalizing policies: at Susa, mass marriages of prominent hetairoi to the daughters of noble Persians were celebrated in conjunction with the legitimization of the thousands of informal unions of Macedonian soldiers with barbarian women. Not a “policy of fusion,” to be sure, or the creation of a “mixed race,” but rather a blueprint for political stability,50 if carried through by a capable leader committed to this vision of a new empire. This ceremony was soon followed by further integration of orientals into the military and the demobilization of some 10,000 Macedonian veterans. The process was regarded as an insult, even by those most eager to return home, and at Opis, for the first time, there was a genuine mutiny within the army. Once again Alexander showed himself a worthy son of Philip II, combining soothing words with largesse, while executing the ringleaders of the sedition. Notions of an appeal for universal brotherhood have, rightly, been debunked,51 but Alexander did not back away from his orientalizing policies; for he must now have given thought to establishing an administrative center in Asia – possibly in Babylon52 – and it appears that he elevated his best friend Hephaestion to the rank of chiliarchos or “Grand Vizier” (on the chiliarchy see Collins 2001).

As it turned out, the Alexanderreich, buffeted by political storms and weighed down by the king’s grandiose schemes, proved too flimsy a structure. Nor was the man himself emotionally prepared for what was to come. In the summer of 324, Nicanor of Stageira had proclaimed the Exiles’ Decree at the Olympic festival (D.S. 18.8.2-6; Zahrnt 2003), its demands far exceeding Alexander’s prerogatives as hegemon of the League and their implications catastrophic for many states, Athens in particular. The danger of war with Macedon was heightened by the arrival of Harpalus and the lure of his money. But Alexander himself was soon plunged into personal tragedy, as Hephaestion died of fever and excessive drinking in Ecbatana (October 324). The king’s grief knew no bounds and, although genuine, its Homeric displays were all too familiar. Anger was eventually directed against the Cossaean rebels, and mercy was in short supply. And in the months that followed, as he awaited the unfolding of events in Europe, including the possible confrontation between Antipater and Craterus, who had been sent to replace him, Alexander turned his thoughts to funeral monuments, a hero cult for Hephaestion, and a demand for his own recognition as a divinity (Habicht 1970: 28-36). In June 323 he too died of illness in Babylon without designating an heir. It would not have mattered, for only three male relatives of the king remained, one of them as yet unborn, and the marshals of the empire had taken too equal a share in the burden of conquest to relinquish overall power to one of their own number. Even as he was destroying the empire’s equilibrium, Alexander had been planning new expeditions to Carthage and Arabia.53 Thus his exit from life, and history, was at the same time an evasion of responsibility. Alexander (the Great) was as fortunate in death as he had been in life, as the burden of dealing with the consequences of his superhuman achievements fell on the shoulders of his all too human successors.

1 Rhodes-Osborne, no. 76.

2 Willrich 1899; Badian 1963; Bosworth 1971b; Kraft 1971: 11–42; Fears 1975; Develin 1981; Heckel 1981.

3 Bosworth 1971b.

4 Hammond–Griffith 208–9.

5 See, however, Ellis 1971, rejected by Prandi 1998; but see Worthington 2003: 76–9. Weber (ch. 5 in this volume) believes that Amyntas was, in fact, a very serious threat to Alexander’s succession.

6 Heckel 1986b: 297–8. For the details of her life and death see Heckel 89–90; Whitehorne 1994: 30¬42; Ogden 1999: 20–2; Carney 2000b: 72–5. The woman is referred to as Cleopatra in all sources except Arr. 3.6.5, where she appears as Eurydice (see Heckel 1978). I have used the compound name for the sake of clarity, to distinguish her from Alexander’s sister Cleopatra.

7 Heckel 1992: 13–33, 299–300.

8 Roebuck 1948: 76–7.

9 D.S. 17.4.6–7; cf. Plu. Dem. 23.3, in the context of Alexander’s destruction of Thebes.

10 Fuller 1960: 225.

11 Wüst 1938: 169; Roebuck 1948: 77–80.

12 Will 1983: 37–45; Habicht 1997: 13–15.

13 Judeich 1892: 302–6; Ruzicka 1985 and 1997: 124–5.

14 Anson 1989; Garvin 2003: 94–5; but HPE 1042 urges caution; on Khababash see Burstein 2000.

15 For the battle see D.S. 17.19–21; Arr. 1.13–16; Plu. Alex. 16; Just. 11.6.8–15.

16 Arr. 1.19; D.S. 17.22.1–23.3; Plu. Alex. 17.2.

17 Arr. 1.20.2 ff.; D.S. 17.23.4 ff.; Plu. Alex. 17.2; Fuller 1960: 200–6; Romane 1994: 69–75.

18 Hornblower 1982: 41–50; HPE 706–7; for Ada in particular Özet 1994.

19 Plu. Alex. 10.1–3; French and Dixon 1986.

20 Engels 1978b: 225–6.

21 For the topography see Hammond 1994a. For the battle see Arr. 2.8–11; Curt. 3.9–11; D.S. 17.33–4; Plu. Alex. 20.5–10; Just. 11.9.1–10; POxy 1798 §44 = FGrH 148.

22 Seibert 1988: 450–1 dismisses charges of “cowardice”; see also Nylander 1993; Badian 2000b; and the comments of Briant in ch. 9.

23 For the siege of Tyre see Arr. 2.16–24.5; Curt. 4.2–4; D.S. 17.40.2–46.5; Plu. Alex. 24–5; Just. 12.10.10–14; Polyaen. Strat. 4.3.3–4; 4.13; FGrH 151 §7; Fuller 1960: 206–16; Romane 1987.

24 HPE 861.

25 Burstein 1991.

26 For the battle of Gaugamela see Arr. 3.11–15; Plu. Alex. 31.6–33.11; D.S. 17.57–61; Curt. 4.13–16; Just. 11.13.1–14.7; Polyaen. Strat. 4.3.6, 17.

27 For the background to the war see McQueen 1978.

28 Borza 1971; Wirth 1971; Lock 1972; Badian 1994.

29 Heckel 2002a.

30 For location and topography, see MacDermot and Shippmann 1999; Speck 2002.

31 D.S. 17.7.8; Bosworth 1988a: 250.

32 Mehl 1980–1; Zahrnt 1996.

33 Seibert 1998; Flower 2000.

34 Balcer 1978; Shabazi 2003: 19–20.

35 Badian 1958b (the paper is a methodological study arguing against the views of Tarn 2.320–3); for Bagoas’ life see Heckel 68; for his relationship with Alexander see Ogden, ch. 11.

36 Heckel 1981: 66–7.

37 Holt 1988: 54–9.

38 Chorienes was, in all likelihood, Sisimithres’ official name: Heckel 1986a; but see Bosworth 1981; 1995: 124–39.

39 Stephanus of Byzantium, s.v. “Alexandreiai”; Fraser 1996; Tarn 1997: ii. 232–59.

40 Holt 1988; Tarn 1997.

41 See Badian 1960; Heckel 1977; Adams 2003.

42 Holt 1988: 78–9 n. 118, plausibly.

43 But see Roisman 2003b: 315–16.

44 Gutschmid 1882: 553–4; Seel 1971: 181–2.

45 Stein 1929; Bosworth 1995: 178–80. For Mt. Ilam: Eggermont 1970: 191–200; Badian 1987: 117 n. 1.