Chapter 12

The next source is perhaps the greatest source for the legend. The History of the Kings of Britain was written by Geoffrey of Monmouth in 1136. The purpose of the book was to trace the history of Britain through 1,900 years. The inspiration was a patriotic one aimed at the Welsh and Bretons. We know Geoffrey had some connection with Monmouth and frequently mentions Caerleon-on-Usk in South Wales. He is named in a number of charters and there is evidence he lived in Oxford and London for a time. However, he appears to be from Welsh or Breton stock. The book is dedicated to Robert, Earl of Gloucester, the son of Henry I and Waleron, Count of Mellent, son of Robert de Beaumont. Three times in the book he mentions Walter, Archdeacon of Oxford, who he claims provided him with a, now lost, ancient book in Welsh.

It is important to be aware of the historical and political situation. Just seventy years earlier, William the Conqueror had taken the throne of England from the Saxon King Harold at the battle of Hastings. For 500 years prior to that the Saxon kingdoms, and later England, had expanded at the expense of the Romano-British. The Welsh, Cornish and Strathclyde were the descendants of these, as were the Bretons in modern Brittany. Saxons were their common enemy. One third of William’s army at Hastings were Bretons and many Breton lords were given land throughout England after the conquest.

We can’t say what these Bretons thought about Britain or the Saxons, but it is not a coincidence the interest in Arthur occurred after the Norman conquest. The Breton link is, I think, important. The Arthur of local legends and magical animals was the dominant one until the twelfth century.1 It was Geoffrey of Monmouth who propelled Arthur into literary fame. The French romance novels further developed the stories to the legend we know today. Indeed, many of the concepts were added at this point: the Round Table, Excalibur, the sword in the stone, even Merlin. The original story is as Nennius describes in the Historia Brittonum around 829: Arthur is a soldier, a leader of battle, leading the kings of Britain against the Saxons in twelve battles culminating in Baden. The Welsh legends and poems weren’t written down until after Geoffrey and may have been influenced by him. The same may be said of the saints’ lives, and both sets of ‘evidence’ are viewed as ahistorical.

Geoffrey makes Arthur a king and one that conquers a vast empire including Norway, Iceland and Gaul. He then engages in a battle against Rome on the Continent. So in Geoffrey’s work, Arthur’s Continental adventures are a major part. The most significant character added to the story is arguably Merlin, but this appears to be manufactured from the Ambrosius of the Historia Brittonum (itself possibly derived form the Ambrosius Aurelianus of Gildas) and the Myrddin Wylit of the Annales Cambriae.

Similar to other medieval historians in Europe, he believed the country was founded by a Trojan prince after the fall of Troy. So Brutus is the first of three main characters in the book, Arthur being the third. Brutus comes to Britain and, after defeating various giants, gives the island its name. A long list of kings and adventures follows, including King Lear of Shakespeare fame. We then have the story of Belinus and Brennius, two brothers who conquer Gaul and Rome.

Brennus was a chieftain of the Senones, a Gaulish tribe, that did indeed sack Rome in 387 BC which demonstrates, as with other characters, that Geoffrey was not averse to being economical with the truth or giving his characters storylines lifted from other figures. There’s no evidence for many of his kings, although as he moves through history he does include more established figures such as Julius Caesar and Claudius. We then go through further kings, who apparently ruled alongside the Romans, until we get to Magnus Maximus, or Maximianus as Geoffrey calls him.

We will take it from there and follow the story up to just before Arthur so we can compare it with Nennius, Gildas and Bede. Geoffrey leaves Maximus having appointed Gracianus in charge, who immediately has to ward off invasions by the Picts and Huns led by Wanius and Malgo. Needless to say, evidence for the veracity of this is absent. There then follows what seems to be a repeat of Gildas with a legion returning, building the wall and a repeating of the Rescript of Honorius. Enemies return, this time Norwegians and Danes, and seize territory up to the wall. So a garbled version of Gildas and Bede with Huns, Danes and Norwegians thrown in for a twelfth-century audience.

We then have the appeal to Agicius, which may well mean Aetius, in 445–54, but Geoffrey seems to be placing this around 410. It doesn’t help that he gives no dates. Around this time he names the Archbishop of London as Guithelinus, a name that may have relevance in the genealogy of Vortigern. He travels to Armorica, modern Brittany, to ask for help from King Aldoneus. The king’s brother, Constantine, comes to Britain with an army and accepts the crown.

Immediately one is confronted with contradictory dates. Is this Constantine the same Constantine III who declares himself emperor from Britain and invades Gaul? On one hand, aside from the appeal of Aetius, the chronology would suggest yes. On the other, Geoffrey gives his children different names and has him ruling for ten years. Constantine III had Constans and Julianus and ruled for four years before being killed in Gaul. Geoffrey’s Constantine also has a son named Constans, but he adds Ambrosius Aurelianus and Uther Pendragon. This will lead to problems later because an Arthur born to Uther in the early or mid-fifth century is unlikely to be fighting at Badon in 516, let alone Camlann in 542, the latter being the only date Geoffrey does give us.

So his chronology is a little muddled to say the least. After Constantine’s death, his son Constans is given the throne but Vortigern, his advisor, conspires to have him killed and takes the throne. We then have the arrival of Hengist and Horsa, but this time settling in Lindsey around Lincoln. Reinforcements arrive and Hengist builds a fortress. Unlike Nennius, however, Geoffrey names the daughter that Vortigern falls for as Renwein. They marry and Hengist is given Kent, removing the British earl, Gorangonus. We then meet St Germanus who, as we know, in reality visited in 429. Octa and Ebissa arrive with 300 more ships and are allowed to settle in Northumberland. Vortigern is deposed and his son Vortimer made king, fighting four battles and forcing the Saxons to leave.

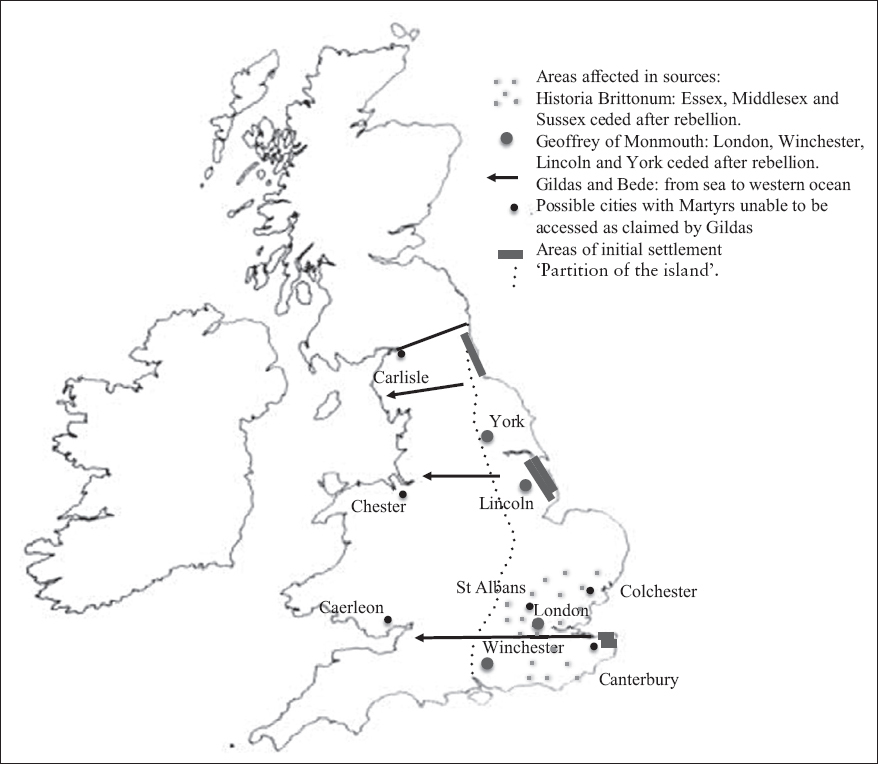

Geoffrey is roughly following Nennius rather than Bede, but with added information. Renwein poisons Vortimer allowing Vortigern to take back the crown and Hengist to return with 300,000 men. The British princes plot to rebel so Hengist arranges for a peace conference. This becomes known as ‘The Night of the Long Knives’ because, on a prearranged signal, Vortigern is captured and 300 British nobles murdered with only one escaping. The Saxons take London, York, Winchester and Lincoln. The timeline is closer to Nennius and any of the events above, such as Vortigern’s marriage, the gifting of Kent, slaughter of the British nobles or the fall of the cities mentioned, could be linked to the entry for 440 in the Gallic Chronicle. However, it makes far more sense with regard to the other sources for these events to be after 450. Whether we take this as a separate event to the Gallic Chronicle or not, there is something worth noting. Despite the discrepancies there are some similarities between Gildas and Bede on one hand, and Geoffrey and Nennius on the other.

We have to remember that there’s no evidence for any of this. It could be Geoffrey that possessed a now lost manuscript, but it’s equally possible he made the whole thing up. To continue, Vortigern then flees to Wales and attempts to build a fortress. We then have the introduction of Merlin into the story. Geoffrey combines two characters here. The first is the Myrddin Wyllt (Mryddin the wild), mentioned in the Annales Cambriae and other Welsh legends as being at the Battle of Arfderydd in 573. The second is Emrys Ambrosius mentioned by Nennius and associated with Vortigern. So he has combined two figures, one from a generation before Arthur and the other from two generations after. Then he’s changed the name to Merlin. Norman French ‘Mryddin’ is a little too close in sound to ‘Merde’, which has a rather impolite meaning. He then devotes much time describing a series of prophecies by Merlin, most notably the story of the red and white dragons with the red one eventually winning over the Saxon white dragon.

The barbarian revolt.

It is significant that Geoffrey, a Welshman or Breton, is writing for a Norman Lord – both would see Saxons as a common enemy. The portrayal of the Saxons as poisoners and betrayers is in line with this. Ambrosius and Uther then land and catch Vortigern in the castle of Genoreu in South Wales, where the castle and it’s occupants are burned to the ground. Ambrosius is crowned king and defeats the Saxons in two battles, Maisbeli and Kaerconan, before executing Hengist. Octa and Eossa surrender and are given Bernicia in Northumberland, while Ambrosius rules from York. We then have an aside where Merlin is called from the land of Geweissi to magically transport the giants ring from Ireland to build Stonehenge as a suitable burial place for the 300 nobles slaughtered by the Saxons. Uther leads an army to Ireland to achieve this. On Uther’s return Vortigern’s son and the Irish king invade. While Uther is defeating them, Ambrosius is poisoned by the Saxons. Still we have no dates.

There is a mention of Uther’s battle where he sees a two-headed dragon in the sky with a fiery tail. Geoffrey uses this to explain Uther’s title of ‘Pendragon’. Some have equated this with Haley’s Comet which would have been around 451. But the mention of St Samson (circa 485–565) being given the Bishopric of York and St Dubricius (465–555) the City of the Legions doesn’t tie in with this. Nor does an Arthur being born soon after, and fighting a battle in 542. There are two records of comets in the fifth century; the first recorded for 497 in a fourteenth-century text, Flores Historiarum. The second is seen from Brittany in 457 and is recorded by a Conrad Wolffart in the sixteenth century. They both have a similar description and may well be influenced by Geoffrey. If not though we once again have more than one possible date, which makes a timeline difficult.

Uther, now king, has to contend with Octa and Eossa who rebel, are defeated and taken prisoner. We then get the famous story of Merlin helping Uther magically change his appearance to seduce Ygraine at Tintagel, and it is this union that produces Arthur. Uther is able to marry Ygraine after her husband dies in battle. Arthur has a sister, Anna, who is married to King Loth of Lothian who assists Uther in fighting the Saxons, Octa having escaped. Uther defeats them before being poisoned at St Albans. We now come to Arthur who occupies a good third of the book. Arthur is crowned by St Dubricius at the age of 15, the same age, incidentally, that Clovis I of the Franks was crowned. The author is more than willing to borrow from other people’s history and make things up, and this could be another example. Arthur defeats the Saxons, now led by Colgrin and Baldulf, at a battle at the river Douglas before besieging York, which is possibly a reference to the City of the Legions in Nennius. He’s forced to retreat to Lincoln before requesting assistance from Hoel of Brittany, son of Arthur’s sister and King Budicius.

Geoffrey doesn’t make clear whether this is a second marriage or a second sister. He does state that Loth and Anna have two sons, Mordred and Gawain. Arthur then gains two victories at Kaerluideoit, Lincoln, and at Caledon Wood, both possible nods to Nennius’s battle list. The Saxons then promise to leave, but break this immediately by sailing round to Devon. Arthur defeats them at the Battle of Badon near Bath. His cousin, Cador, Duke of Cornwall pursues the Saxons to Thanet, reminiscent of Vortimer’s four battles. Arthur then fights three battles against the Picts, another at Loch Lomond and one against a King Gilmarius of Ireland. He marries Guinevere before invading Ireland and receiving the surrender of the Orkneys and Gotland.

Twelve years go by, meaning Arthur is now 27 in the story, and he invades Norway and Denmark before marching on Paris, defeating a Frollo in single combat, and subduing Gaul. It goes without saying there is no evidence for any of this. We know there were Britons fighting in the Loire valley in the 460s and of course Riothomus in 471, but whether these are from Britain or Brittany is impossible to say. Otherwise we have Frankish expansion into Brittany that might be the basis for a British leader fighting in France either side of 500. But there was certainly no conquest of Norway or Ireland at this time. It may well be that he has stolen the story of Maximus, or one of the other Roman leaders declared emperor from Britain who then invaded Gaul.

Nine years go by, making Arthur 36, and we then come to the main part of the narrative. One that is often forgotten in subsequent stories. While in court in Caerleon-on-Usk, messengers from the Roman Procurator, Lucius Hiberius arrive, demanding tribute and submission. This is said to be in the time of the Roman emperor Leo. In fact the eastern emperor, Leo I, reigned from 457–74 and Leo II in 474. There was a Pope Leo in 440–61, but that seems too early. There is no record of a Lucius Hiberius, although a western emperor Glycerus (473–4) was sometimes misspelled as Lucerius. If true, this would place Arthur’s birth around 438, which would not tie in with any of the other implied dates, or indeed fighting at Camlan aged 96. Arthur refuses on the basis that Brennius and Constantine the Great had defeated Rome and so Rome owed allegiance to Britain. This is quite important; Geoffrey is telling his audience that Britain has a glorious past that gives it authority over other nations. To push the point further he has Arthur take an army to Gaul to fight the Romans, leaving his nephew Mordred in charge of Britain. There is a short story of Arthur defeating a giant at Mont St Michel in which he remembers another giant-killing act. He describes in great detail a huge battle in the Saussy region between Langres and Autun, near Dijon in Eastern France. Needless to say, there is no such record of British or even Roman military activity in this area at this time. Arthur is, of course victorious, and prepares to invade Italy and take Rome.

At this point he learns that Mordred and Guinivere have betrayed him and have allied with Saxons led by Chelric. Arthur returns to Britain and defeats Mordred at the battles of Richborough and Winchester, possibly referring to Fort Guinnion. Mordred is finally killed at the battle of Camlann in Cornwall. Arthur is fatally wounded and taken to the Isle of Avalon so that ‘his wounds might be attended to’. Arthur orders that his cousin Constantine takes the crown. Nothing more is said and his death is not confirmed beyond the fatal wounding comment. So we see the legend we know today start taking shape. But you may notice the absence of Excalibur, the Round Table, Lancelot and the Grail. Geoffrey actually names the sword ‘Caliburn’, but these later concepts were added by other authors inspired by Geoffrey’s work.

Geoffrey states the battle of Camlann was in 542 and assuming this was a year after his Roman war, he died aged about 37. So, working backwards, we have a birth date around 505 and a battle of Badon after his crowning at 15, placing it after 520. Uther reigns at least fifteen years, suggesting the comet in 497 is the more likely one to be connected. This does put Ambrosius reigning in the 490s slightly at odds with Bede’s statement that it was in the time of Zeno, 474–91. It also pulls Vortigern right up towards the later part of the fifth century. While we can’t trust any of the narrative or dates, there is one glaring problem with the text. There simply was no British army victoriously rampaging across Roman Gaul in either the fifth or sixth centuries. We know there was a Romano-Saxon war in the 460s and the Romans later requested help from a British king, Riothamus. But his battle was against the Goths and he lost, never to be heard of again. The history of sixth-century Gaul is fairly well known and neither British or Roman armies featured. We will discuss the relationship between Bretons and Franks later, but we can be fairly certain this part is inaccurate.

After Camlann, Geoffrey then proceeds to list four of the five kings denounced by Gildas: Constantine is the first, followed by Aurelius Conanus, Vortiporus, and Malgo (Maelgwn). He misses out Cuneglasse. This is the king Gildas accuses of rejecting his wife and taking her sister from ‘holy orders’. He goes on to call him: ‘Bear; Driver of the chariot of the bear’s stronghold; Red butcher; and with arms special to yourself.’ Could it be because Geoffrey has already mentioned him? The Bear, ‘arth-’ in Welsh, being possibly an epitaph for Arthur? That, I’m afraid, is hugely speculative. Many have tried to suggest it, and he is one of the candidates that people have put forward, but he’s one among many. I would add also that Gildas appears to be delivering his sermon as all five kings are ruling. Geoffrey has them coming sequentially.

It is accepted that he had access to Gildas, Nennius, Annales Cambriae, Harleian Genealogies and a number of Welsh legends and poems. His account does not stop there though. He then describes a King Keredic and the invasion by Gormund, king of the Africans, with an army of 160,000 aided by Isembard nephew of Louis, king of the Franks. This does seem complete fabrication. He ends in 689 with the death of Cadwallader, the seventh-century King of Gwynedd and the last Welsh king to claim lordship over Britain. He finishes by berating the Welsh for their tendency to civil war and claiming the Saxons behaved more wisely and kept the peace among themselves.

The book as a whole does have a particular message: it is the first attempt at a full historical narrative for Britain. It shows a great and glorious past descended from the kings of Troy and equal to the Romans. Arthur is simply one of three main characters, Brutus, Brennius and Arthur. It shows that the Welsh and Bretons have a proud history and the prophecies are there to demonstrate they will rise again if they avoid the civil wars and discord. To help this narrative Geoffrey is quite happy to include fictitious characters and events alongside giants and magic. It also also provides a link between Britain, Brittany and France, at the same time demonstrating the dangers of discord and civil wars. The Saxons and the Romans provide a common enemy for the Welsh and the whole narrative would not offend his Norman sponsors. In fact, Arthur emerged as a popular character only after the Norman conquest.2 Prior to that Arthur is the more mystical and magical character of Welsh poems and legends that weren’t written down until much later.

It is quite possible that Geoffrey made the whole thing up. But it’s also possible he took that one reference in Nennius and added an elaborate tale using bits of other historical characters, myths and legends. The author of the translation I have been using does state ‘most of the material in the History is fictional and someone did invent it,’ yet ‘history keeps peeping through the fiction’.3 For example, Geoffrey describes the Venedoti decapitating a whole Roman legion in London and then throwing their heads into a stream called Nantgallum, or Galobroc in Saxon. In 1860 a large number of skulls were indeed found in the bed of the Walbrook in London.

Contemporary writers had something to say about Geoffrey. William of Newburgh writing around 1198 in History of English Affairs:

For the purpose of washing out those stains from the character of the Britons, a writer in our times has started up and invented the most ridiculous fictions concerning them, and with unblushing effrontery, extols them far above the Macedonians and Romans. He is called Geoffrey, surnamed Arthur, from having given, in a Latin version, the fabulous exploits of Arthur, drawn from the traditional fictions of the Britons, with additions of his own, and endeavored to dignify them with the name of authentic history.

Ranulf Higden of Chester writing in 1352:

Many men wonder about this Arthur, whom Geoffrey extols so much singly, how the things that are said of him could be true, for, as Geoffrey repeats, he conquered thirty realms. If he subdued the king of France to him, and did slay Lucius the Procurator of Rome, Italy, then it is astonishing that the chronicles of Rome, of France, and of the Saxons should not have spoken of so noble a prince in their stories, which mentioned little things about men of low degree. Geoffrey says that Arthur overcame Frollo, King of France, but there is no record of such a name among men of France. Also, he says that Arthur slew Lucius Hiberius, Procurator of the city of Rome in the time of Leo the Emperor, yet according to all the stories of the Romans Lucius did not govern, in that time nor was Arthur born, nor did he live then, but in the time of Justinian, who was the fifth emperor after Leo. Geoffrey says that he has marveled that Gildas and Bede make no mention of Arthur in their writings; however, I suppose it is rather to be marvelled why Geoffrey praises him so much, whom old authors, true and famous writers of stories, leave untouched. But perhaps it is the custom of every nation to extol some of their blood-relations excessively, as the Greeks great Alexander, the Romans Octavian, Englishmen King Richard, Frenchmen Charles; and so the Britons extolled Arthur. Which thing happens, as Josephus says, either for fairness of the story, or for the delectation of the readers, or for exaltation of their own blood.

We also have writers with the opposite view. William of Malmesbury in The Deeds of the kings of England (De Gestis Regum Anglorum) c.1125:

…the strength of the Britons diminished and all hope left them. They would soon have been altogether destroyed if Ambrosius, the sole survivor of the Romans who became king after Vortigern, had not defeated the presumptuous barbarians with the powerful aid of the warlike Arthur. This is that Arthur of whom the trifling of the Britons talks such nonsense even today; a man clearly worthy not to be dreamed of in fallacious fables, but to be proclaimed in veracious histories, as one who long sustained his tottering country, and gave the shattered minds of his fellow citizens an edge for war.

Then Henry of Huntingdon, History of the English (Historia Anglorum) c.1130:

The valiant Arthur, who was at that time the commander of the soldiers and kings of Britain, fought against the invaders invincibly. Twelve times he led in battle. Twelve times was he victorious in battle. The twelfth and hardest battle that Arthur fought against the Saxons was on Mount Badon, where 440 of his men died in the attack that day, and no Briton stayed to support him, the Lord alone strengthening him.

Both these examples pre-date Geoffrey’s work but are clearly derived from Nennius. But concerning Geoffrey’s work: what value can there be in a book, written 600 years after the event, that contains so much false history not to mention giants and magic? Yet he also names lots of historical figures too. There have been some modern historians who have agreed.

Leslie Alcock, Arthur’s Britain (1971):

There is acceptable historical evidence that Arthur was a genuine historical figure, not a mere figment of myth or romance.

John Morris, The Age of Arthur (1973):

…he was as real as Alfred the Great or William the Conqueror.

Others take a different view.

Michael Wood, In Search of the Dark Ages (1987):

Yet, reluctantly we must conclude that there is no definite evidence that Arthur ever existed.

David Dumville, Histories and Pseudo-histories (1990):

The fact is that there is no historical evidence about Arthur; we must reject him from our histories and, above all, from the titles of our books.

After the History of the Kings of Britain was written in 1136 there was a rapid increase in interest and subsequent works. Fifty years later the monks of Glastonbury claimed to have made a remarkable discovery. In 1184 a great fire destroyed many buildings at Glastonbury Abbey. A chronicler at the abbey of Margam records that a monk had begged to be buried at a certain spot. When he died in 1191 the monks duly obeyed his request. Digging down they came across three coffins. The first contained the bones of a woman claimed to be Guinevere. The second, a man supposedly Mordred, ‘his nephew’. The last, with a leaden cross fixed, were the bones of a large man. The inscription stated:

Here lies the famous King Arthur buried in the Isle of Avalon.

He goes on to explain that the place was once surrounded by marshes, and is called the Isle of Avalon, that is ‘the isle of apples’. Explaining that ‘aval’ means, in British, an apple.

Gerald of Wales, writing shortly after, also recorded what happened. It is slightly different but he at least visited the site and handled the cross. Acting supposedly on the word of Henry II before he died in 1189, two years later they discovered, 16 ft below the ground, a hollowed oak tree that contained two skeletons. Under the covering stone was a lead cross bearing the following inscription.

Here lies buried the famous Arthurus with Wenneveria his second wife in the isle of Avalon.

Ralph of Coggeshall, writing in 1193, also mentioned it and supports the Margram version:

Here lies the famous King Arturius, buried in the Isle of Avalon.

Historical records differ on the number of tombs, skeletal remains and exact inscription. The majority appear to suggest two bodies and the reference to Arthurius and Isle of Avalon. The bones were transferred to a marble tomb in the Lady Chapel. A hundred years later during a visit by Edward I, there was a ceremony to move the bones again, this time to a black marble tomb in front of the altar of the larger church. The bones disappeared during the dissolution of the monasteries under Henry VIII. The leaden cross apparently survived.

Excavations in the 1960s suggest that there was a grave in that spot. We also know the cross was real. Leland described it in 1534 and William Camden sketched one side in 1607, it’s inscription supporting that of the Margam Chronicle and thus bringing into doubt Gerald of Wales (although leaving open to question what was on the other side). He admits he sketched it from the original copy and some of his copies differ in the shape of the letters. Sadly the cross went missing in the eighteenth century. Modern academics dismiss the find as a hoax for a number of reasons. First, following the devastating fire and the death of their greatest benefactor, the king, pilgrims and money had dried up. The scale of false religious artefacts and forgeries by the church in the Middle Ages should give pause for thought. Second, the letterforms are not consistent with the fifth century, but appear to be tenth century, as does the shape of the cross. The monks also had a history of similar claims. William of Malmesbury, writing shortly before Geoffrey, claimed that St Patrick was buried there in 472, dying aged 111. Like Geoffrey, he makes no link between Glastonbury and Arthur’s grave, claiming Arthur’s resting place is ‘nowhere to be seen’. William also claims the name Glastonbury comes from the founder, Glasteing. Indeed, the earliest record is Glestingaburg in the seventh century. There is no mention of islands or apples. Another legend also has it that Joseph of Arithamea founded the abbey in the first century and this is linked to Robert de Boron’s twelfth-century poems: The Holy Grail, Joseph of d’Arimathe and Merlin, all of which post-date Geoffrey of Monmouth.

The abbey itself was not built until the seventh century and was extended in the tenth. There is no evidence for any of these legends and no archaeological evidence for earlier activity on this site. Geoffrey of Monmouth did not connect Avalon with the site. In his Life of Merlin, he does call Avalon Insula Pumorum, or Isle of Apples; in his History it is Insula Avallonis. He does not associate this with Glastonbury. In the Life of St Gildas written by Caradoc of Llancarfan in 1130–50, he tells the story of Melwas capturing Guinevere, and Arthur coming to Glastonbury to release her. Gildas intervenes and is later buried in the floor of St Mary’s church, despite all the other legends and evidence which place his resting place at Rhuys in Brittany. The same author also includes Arthur in the Life of St Cadoc. There is no mention of Avalon or any association with Glastonbury.

In the Brut y Brenhinedd, a mid-thirteenth century copy of Geoffrey’s work, this becomes Ynys Afallach. This suggests an island belonging to someone called Afallach, an attested Welsh name. This is similar to a King Avallo mentioned by Geoffrey. However, there are also similarities to other Welsh legends. In the Preiddeu Annwn, a cauldron, sought by Arthur, is guarded by nine maidens and it is a place where neither age or injury can hurt. In another Welsh myth, Afallach is the King of Annwn and father to the goddess Modron. Gerald of Wales also relates how Margan, a goddess of Annwfyn, hid Arthur in Ynys Afallach. In fact as early as the first century, a Roman geographer, Pomponius Mela, described an island, Sena, off the coast of Brittany. There, nine virgin priestesses cared for the oracle of a Gaulish god.

What all this demonstrates is that the association of Glastonbury with Avalon came after Geoffrey of Monmouth. Prior to this, Arthur’s resting place is seen as distinctly mythical and in part of the legend he wasn’t dead at all but would return in time of need. It also shows that separate to Arthur there were tales of islands, nine virgin priestesses and cauldrons. We also have a historical account of a first-century island off Brittany. It may also show the willingness of medieval writers to blend stories and legends and be willing to create myths and foundation stories to boost claims and revenue. This is something to bear in mind when reading the saints’ lives. Importantly it also demonstrates there was no particular consensus in the Middle Ages about Arthur’s resting place or even historicity. Tales and stories emerging 600 years after Arthur’s alleged time can hardly be held up as evidence.

In 1981 someone claimed the cross had been found in a lake in Enfield. The man took it to the British Museum and an employee who saw the cross described it as just over 6 in high, not the 1 ft Leland described in 1532. The finder, however, refused to hand the cross over and his description of the cross included the same wording and size as the William Camden sketch. Despite the council’s attempts, the cross was never recovered. The gentleman in question was apparently a lead-pattern worker for a local toy maker and was involved in the manufacture of lead models of cars. He was also a member of the Enfield Archaeological Society.

One possibility is that this was a hoax concerning an earlier hoax and highlights the need to treat any evidence with a healthy scepticism. There is a tendency to view evidence from the twelfth century, for example, with greater weight than it deserves; certainly more than a story written in modern times. While a modern story may have no historical value, we forget many of these tales were written 700 years or more after Arthur is supposed to have lived. In a similar vein, many modern theorists selectively pick out certain aspects of Geoffrey and other stories and mix them together in an attempt to build a coherent theory, neglecting to lay out the 90 per cent that has been cast aside. Later we will cover the genealogies that were also written many hundreds of years later. Theorists have used these and many of the names in Geoffrey’s work to build up a family tree. It is vital the reader looks to the original sources and not take the evidence at face value. There are a number of authors who have misrepresented and misspelt names to fit in with their theory. The reader will discover that many an ‘Arthur’ is not an Arthur at all, but Anthun, Atroys or Arthwys. There are as many people today willing to manipulate the evidence, or even lie for whatever purpose, as there were at any time since the fifth century.

In summary, we have a twelfth-century text, written 600 years after the events. It is contradictory and full of suspect material. Yet history does indeed ‘peep through the cracks’. On one hand the author is wholly unreliable, but on the other it shows a persistence of the legend and a receptive audience in the twelfth century. Additionally, as we shall see later, there is a way of interpreting the narrative that does not contradict other sources at all. This interpretation shouldn’t, of course, be mistaken for proof.