PART THREE

23

‘A Frenchman is brave but long privations and bad climate would wear him down and discourage him. Our climate, our winter, will fight on our side.’

Tsar Alexander to Caulaincourt, early 1811

‘One must never ask of Fortune more than she can grant.’

Napoleon on St Helena

Napoleon toured his Empire for many weeks of the year, and always at breakneck speed. In the autumn of 1811, he visited forty cities in twenty-two days, despite losing two and half days stuck on board the warship Charlemagne at Flushing due to a gale and another day at Givet when the Meuse flooded its banks. He was much more interested in gleaning information than in listening to laudatory speeches from local worthies. On one occasion when a mayor had taken great pains to commit a speech to memory, Napoleon had ‘scarcely given him time to present the keys before the coachman was impetuously ordered to drive on, and the mayor left to harangue the air’. The mayor was perhaps consoled by seeing an account of the presentation of the keys and his entire speech reproduced in the next day’s Moniteur. ‘“No harangue, gentlemen!” is frequently the discouraging apostrophe with which Bonaparte cuts short these trembling deputations,’ recalled the civil servant Theodor von Faber.1 The questions Napoleon asked mayors were testimony to his omnivorous appetite for information. One might have expected inquiries about population, deaths, revenues, forestry, tolls, municipal rates, conscription and civil and criminal lawsuits, and Napoleon certainly asked them, but he also wanted to know ‘How many sentences passed by you are annulled by the Court of Cassation?’ and ‘Have you found means to provide suitable lodgings for rectors?’2

• • •

‘There is proof’, Napoleon wrote to Tsar Alexander on November 4, 1810, ‘that the colonial produce at the last Leipzig Fair was brought from Russia in seven hundred wagons . . . and that 1,200 merchant vessels, under Swedish, Portuguese, Spanish and American colours, which the English escorted with twenty warships, have partly landed their cargoes in Russia.’3 The letter went on to ask him to confiscate ‘all the goods introduced by the English’. In December Napoleon ordered Champagny to give Alexander Kurakin, the Russian ambassador to Paris, and simultaneously Caulaincourt to give the Tsar, a direct warning that should Russia open her ports to ships carrying English merchandise in direct contravention of the Tilsit treaty, then war would become inevitable.4

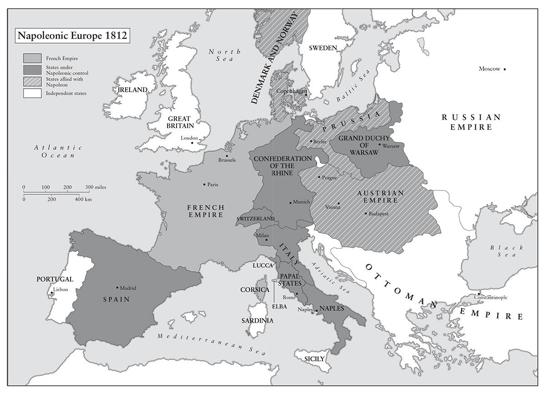

It was largely in order to combat smuggling across the German north-west littoral that Napoleon annexed the Hanseatic Towns such as Hamburg, Bremen and Lübeck on December 19 1810. After Rome, Hanover and Holland, it was Napoleon’s fourth annexation in the past twelve months, and like them it arose directly as a result of his obsession with his protectionist economic war against Britain. Yet taking over the direct rule of these major cities made no geographical or commercial sense without also acquiring the 2,000-square-mile Duchy of Oldenburg on the left bank of the Weser, whose ruler, Duke Peter, was the father-in-law of Alexander’s sister, the Grand Duchess Catherine Pavlovna. Despite repeated warnings from Napoleon it continued to trade relatively openly with Britain, to the point that it has been likened to an enormous warehouse for smuggled goods.5 Although the duchy’s independence had been guaranteed by Tilsit, Napoleon decided to close this loophole and annexed Oldenburg on the same day as the Hanseatic Towns. A month later he offered Duke Peter the small principality of Erfurt in compensation for the duchy, which was six times larger, but this left Alexander even more affronted.6

Franco-Russian tensions had long pre-dated Napoleon; Louis XVI had supported the Ottomans against Russian expansionism, and had made common cause with Gustav III of Sweden in the Baltic.7 Successive tsars and empresses had looked westwards since Peter the Great visited every major European court (except Versailles) on his travels at the end of the seventeenth century, and St Petersburg was a testament to this westward outlook. Alexander had brought Russia up to the Danube with the annexations of Moldavia and Wallachia, and looked covetously towards Turkey’s Balkan possessions. The Russians under Alexander’s grandmother, Catherine the Great – herself a German princess who had long seen France as a potential antagonist – had partitioned Poland three times between 1772 and 1795, and Alexander’s father, Paul I, had become Grand Master of the Knights of Malta and sent the great General Suvorov into Lombardy and Switzerland. Russia’s ambitions to be a major European power were therefore very long-standing, and were always likely to cause tensions with whichever was the hegemonic European power of the day. For much of the eighteenth century, and certainly by Napoleon’s time, that was France.

Even before Napoleon’s annexation of Oldenburg, Alexander had been making plans for another war against France.8 His war minister Barclay de Tolly, his military advisor General Ernst von Phull, a French émigré Comte d’Allonville and a former adjutant to the Tsar, Count Ludwig von Wolzogen, were all sending him detailed schemes from October 1810 onwards that covered every offensive and defensive contingency. In early December, Barclay planned for a defensive battle on both sides of the Pripet Marshes, in modern-day southern Belarus and northern Ukraine, after a quick pre-emptive Russian attack had destroyed Napoleon’s bases in Poland.9 From being (Napoleon hoped) an enthusiastic friend at Tilsit, and a more reluctant ally at Erfurt, Alexander was now looking more and more like a future enemy.

Tilsit’s constraints on trade had meant that the Russian treasury had been running unsustainably large deficits, of 126 million rubles in 1808, 157 million in 1809 and 77 million in 1810. Her national debt increased thirteen-fold, with dire consequences for the value of her currency. In 1808 the volume of Russia’s Baltic exports had dropped to one-third of their 1806 level.10 On December 19, the same day that Napoleon annexed the Hanseatic Towns and Oldenburg, Tsar Alexander retaliated by publishing a ukaz(decree) which stated that from the end of the year Russian trade would be opened to neutral countries (such as America, though not including Britain) and that certain French Empire luxury goods would be banned, while others – such as wine – would be subjected to heavy import duties.11 Cambacérès believed that the ukaz had ‘destroyed our commercial relationship with Russia and . . . revealed the true intentions of Alexander’.12 It did state that all goods manufactured in England would be burned, but added that so too would certain silks and cloths manufactured in France and the Rhine Confederation. On hearing the news, Napoleon said: ‘I would sooner receive a blow on the cheek than see the produce of the industry and labour of my subjects burnt.’13 It wasn’t long before British ships flew the Stars and Stripes so that they could evade the ukaz regulations, with the covert complicity of Russian customs officials.14

The year 1811 saw the start of a continental economic crisis that lasted two years and that also engulfed Britain, which was beset by bad harvests, mass unemployment, wage cuts, Luddism and food shortages.15 Mulhouse in eastern France saw two-thirds of its workforce of 60,000 unemployed, and over 20,000 were unemployed in Lyons.16 Napoleon needed to stimulate growth, but his Colbertian economic views, which rejected the idea of competition and free exchange as positive phenomena, sent him back to attempting to enforce ever more strictly the Continental System, even if it might eventually mean fighting Russia again. Napoleon feared that if Russia were allowed to leave the System other countries might follow, but in 1811 none was likely to try.

By 1812 Napoleon believed that the Continental System was working, and cited the bankruptcies of various London banks and commercial enterprises to support this. As his private secretary Baron Fain put it: ‘A little more effort and the blockade would have subdued British pride.’17 Napoleon assumed that Britain couldn’t simultaneously afford, in Fain’s list, ‘the occupation of India, the war against America, the establishments in the Mediterranean, defending Ireland and its own coasts, the garrisoning of the huge navy, and at the same time the stubborn war . . . against us in the Peninsula’.18 In fact such was the credit-worthiness of the British government and the underlying strength of the British economy that all those commitments could just about be sustained simultaneously, but Napoleon was certain that to break British commerce it was necessary for the Continental System to encompass all Europe. Having brought Prussia and Austria into the System in 1807 and 1809 he was not about to allow the Russians to break it, even though Russian trade was never an important factor in the British economy – certainly not as important a factor as British trade was for Russia’s. By then some 19 per cent of Britain’s exports went to the Iberian peninsula, another reason why Napoleon should have gone back there rather than putting pressure on Russia.19

Napoleon was not wrong in assuming that Britain was suffering very seriously as a result of his Continental System throughout 1811 and the first half of 1812, which have been described as ‘years of grave danger for the British state’.20 Trade declined rapidly, government 3 per cent consols fell from 70 in 1810 to 56 in 1812, the bad harvests of 1811 and 1812 led to food shortages and inflation, and war expenditure increased budget deficits from £16 million in 1810 to £27 million in 1812. Some 17 per cent of Liverpool’s population was unemployed during the winter of 1811/12, and the militia had to be deployed against potential rioters and Luddites across the Midlands and North of England, with ringleaders sentenced to transportation to Australia, or even in some cases death.21The worst moment for the British economy in fact came with the outbreak in June 1812 of the war against America over trade and impressment issues.22 Yet Spencer Perceval stuck rigidly to his programme of funding the Peninsular War, while meeting all Britain’s other commitments as listed by Fain. The immense pressure on Britain only lifted in late 1812 and early 1813 as a result of Napoleon’s campaign in Russia; had he not undertaken it, there is no way of knowing how long Britain could have held out against the Continental System.

The ukaz directly contravened the Tilsit and Erfurt agreements and was a clear casus belli, threatening Napoleon’s imperial system at a time when he was capable of raising an army of over 600,000 men. Yet even if Napoleon had defeated Russia in 1812, it is doubtful that he could have enforced the Continental System. Would he have then annexed the rest of the south Baltic coastline, and installed French customs officials at St Petersburg? He probably assumed that a defeated Alexander would administer the System for him again, as he had between 1807 and 1810, but it is doubtful that this crucial aspect of his plan was properly thought through. There are certainly no letters in his vast correspondence that even refer to how he intended to enforce his ban on British trade after the war.

On Christmas Day 1810, Alexander wrote to Prince Adam Czartoryski about ‘the restoration of Poland’, baldly stating: ‘It is not improbable that Russia will be the Power to bring about that event . . . This has always been my favourite idea; circumstances have twice compelled me to postpone its realisation, but it has nonetheless remained in my mind. There has never been a more propitious moment for realising it than the present.’23 He asked Czartoryski to canvass opinion among Poles as to whether they would accept nationhood ‘from whatever quarter it might come, and would they join any Power, without distinction, that would espouse their interests sincerely and with attachment?’ Asking for absolute secrecy, he wanted to know ‘Who is the officer who has the greatest influence upon opinion in the army?’, freely admitting that his offer of ‘a regeneration of Poland . . . is based not on a hope of counterbalancing the genius of Napoleon, but solely on the diminution of his forces through the secession of the Duchy of Warsaw, and the general exasperation of the whole of Germany against him’. He attached a table showing that the Russians, Poles, Prussians and Danes together could amount to 230,000 men, against Napoleon’s forces in Germany of 155,000. (Since Alexander included a figure of only 60,000 French, and the Danes were loyal allies of France, the table made little sense.) Alexander concluded by warning Czartoryski that ‘Such a moment presents itself only once; any other combination will only bring about a war to the death between Russia and France, with your country as the battlefield. The support on which the Poles can rely is limited to the person of Napoleon, who cannot live for ever.’24 Czartoryski replied sensibly, questioning the Tsar’s figures and pointing out that ‘the French and Poles are brothers in arms . . . the Russians are her bitter enemies’, and that there were 20,000 Poles fighting in Spain, who would be open to ‘the vengeance of Napoleon’ if they suddenly swapped sides.25

This correspondence had the effect of turning Alexander against an offensive war from the spring of 1811, although Napoleon was still worried about a surprise attack well into the spring of 1812. Had he known that Alexander was seeking secret military conventions with Austria and Prussia at this time he would have been even more concerned. In September 1810, Alexander had approved Barclay’s increases in army recruitment and introduction of deep-seated military and social reforms.26 Russia adopted the corps and divisional system; the War College was abolished and all military authority was brought into the war ministry; orders were given for military production factories to stay open on Church holidays; a law entitled The Regulation for the Administration of a Large Active Army was passed, providing for – among many other things – the better collection and distribution of food; the powers of army commanders were codified and regulated; and a more efficient staff structure was introduced.27 Alexander himself took charge of an extensive fortification programme of Russia’s western frontier, which, because her most recent wars had been fought in the north against Sweden and in the south against Turkey, was relatively under-protected. These fortifications, and the relocation of troops from Siberia, Finland and the Danube to the Polish border, were considered a provocation by Napoleon, who, according to Méneval, came to the conclusion by early 1811 that Russia intended ‘to make common cause with England’.28 In the first week of January 1811, Alexander wrote to his sister Catherine: ‘It seems like blood must flow again, but at least I have done all that is humanly possible to avoid it.’29 His actions and correspondence over the previous year clearly belied him.

A huge military concentration was beginning, on both sides. On January 10 Napoleon reorganized the Grande Armée into four corps. The first two, under Davout and Oudinot, were stationed on the Elbe, a third under Ney occupied Mainz, Düsseldorf and Danzig – the last of which, by January 1812, was turned into a major garrison city containing enough stores to sustain 400,000 men and 50,000 horses. By April 1811 a million rations had been amassed in Stettin and Küstrin (present-day Szczecin and Kostrzyn) alone.30 Napoleon managed everything, from the significant – ‘If I were to have war with Russia,’ he told Clarke on February 3, ‘I reckon that I should require two hundred thousand muskets and bayonets for the Polish insurgents’ – down to a complaint a few days later that twenty-nine out of one hundred conscripts on a march to Rome had deserted at Breglio.31

Napoleon didn’t actively want war with Russia, any more than he had wanted it with Austria in 1805 or 1809, but he was not about to avoid it through concessions that he feared might compromise his empire. Writing to Alexander in late February 1812, in a letter he gave the Tsar’s aide-de-camp, Colonel Alexander Chernyshev, who was attached to the Russian embassy in Paris, he enumerated in friendly, temperate language all his various grievances, saying that he had never intended to revive the Kingdom of Poland, and insisting that their differences over issues such as Oldenburg and the ukaz could be resolved without conflict.32 Chernyshev, who unbeknown to Napoleon was Russia’s extremely successful spymaster in Paris, took eighteen days to get the letter to Alexander and another twenty-one days to have the necessary discussions and return.33 By the time Chernyshev got back to Paris, Poniatowski had heard of Czartoryski’s soundings among the Polish nobility and Napoleon had put his forces in Germany and Poland on full alert for a Russian attack expected between mid-March and early May.

‘I cannot disguise from myself that Your Majesty no longer has any friendship for me,’ Napoleon had written to Alexander.

You raise all kinds of difficulties on the subject of Oldenburg, when I do not refuse an equivalent for that country, which has always been a hotbed of English smugglers . . . Allow me to say frankly to Your Majesty that you forget the benefits you have derived from this alliance, and yet what has happened since Tilsit? By the treaty of Tilsit you should have restored Moldavia and Wallachia to Turkey; yet, instead of restoring those provinces, you have united them to your empire. Moldavia and Wallachia form one-third of Turkey-in-Europe; it is an immense addition which in resting the vast empire of Your Majesty on the Danube, deprives Turkey of all force.34

Napoleon went on to argue that if he had wanted to re-establish Poland, he could have done it after the battle of Friedland, but he deliberately hadn’t done so.

Having ordered a fresh military levy of serfs on March 1, Alexander replied: ‘Neither my feeling nor my politics have changed, and I only desire the maintenance and consolidation of our alliance. Am I not rather allowed to suppose that it is your Majesty who has changed towards me?’35 He mentioned Oldenburg, and ended, somewhat hyperbolically: ‘If war must begin, I will know to fight and sell my life dearly.’36

• • •

On March 19, 1811, almost a year after her first encounter with Napoleon, Marie Louise felt birth-pangs, and as Bausset recalled, ‘all the court, all the great functionaries of the State assembled at the Tuileries, and waited with the greatest impatience’.37 None more so than Napoleon, who, Lavalette remembered, was ‘much agitated, and went continually from the salons to the bedchamber and back again’.38 He took Corvisart’s advice to hire the obstetrician Antoine Dubois, whom he paid the vast sum of 100,000 francs, but advised, ‘Pretend you’re not delivering the Empress but a bourgeois from the rue Saint-Denis.’39

Napoléon-François-Joseph-Charles was born at 8 a.m. on Wednesday, March 20, 1811. It was a difficult, even traumatic birth. ‘I’m not naturally soft-hearted,’ admitted Napoleon years later, ‘yet I was much moved when I saw how she suffered.’ It required instruments which meant that the baby emerged with ‘a little scratching about the head’ and needing ‘much rubbing’ on delivery.40 ‘The redness of his face showed how painful and laborious his entry into the world must have been,’ wrote Bausset. Despite everything he had done for an heir, Napoleon instructed the doctors that if it came to a choice the Empress’s life must be saved rather than the baby’s.41 The infant was proclaimed ‘King of Rome’, a title of the Holy Roman Empire, and was nicknamed ‘L’Aiglon’ (the Eaglet) by Bonapartist propagandists.

The baby’s second name was a tribute to his grandfather, the Emperor of Austria, and the fourth was further indication that Napoleon had loved his father, even if he hadn’t much admired him. Because it had been announced that the birth of a daughter would be signalled by a salute of twenty-one guns and that of a son by a hundred and one, there was huge celebration in Paris on the twenty-second boom of the cannon, which was so widespread that the prefecture of police had to stop all traffic in the city centre even days later.42 ‘My son is big and healthy,’ Napoleon wrote to Josephine, with whom he had stayed affectionately in touch. ‘I hope that he will grow up well. He has my chest, my mouth, and my eyes. I trust that he will fulfil his destiny.’43 Napoleon was a doting father. ‘The Emperor would give the child a little claret by dipping his finger in the glass and making him suck it,’ recalled Laure d’Abrantès. ‘Sometimes he would daub the young prince’s face with gravy. The child would laugh heartily.’44 Many royals were stern and unloving towards their children at that time – the Spanish Bourbons and British Hanoverians almost made a practice of hating their children – but Napoleon adored his son. He was inordinately proud of the boy’s bloodline, pointing out that through his mother’s brother-in-law he was related to the Romanovs, through his mother to the Habsburgs, through his uncle’s wife to the Hanoverians and through his mother’s great-aunt to the Bourbons. ‘My family is allied to the families of all the sovereigns of Europe,’ he said.45The fact that all four families currently longed for his overthrow in no way lessened his satisfaction.

• • •

In early April 1811 Napoleon sent a letter to the King of Württemberg, asking him to join the kings of Saxony, Bavaria and Westphalia in providing men to protect Danzig from the Royal Navy. In it he mused with a certain poetic resignation on the tendency of talk of war to lead ineluctably to a confrontation, and suggested that the Tsar might be forced into war whether he wanted one or not.

If Alexander desires war, public opinion is in uniformity with his intentions; if he does not wish for war . . . he will be carried away by it next year and thus war will take place in spite of him, in spite of me, in spite of the interests of France and those of Russia. I have seen this happen so often that my experience of the past unveils the future. All this is an operatic scene, the shifting of which is in the hands of the English . . . If I do not wish for war, and if I am far from desiring to be the Don Quixote of Poland, I have the right to insist upon Russia remaining faithful to the alliance.46

He also feared the effect of Russia and Turkey coming to terms, something he ought to have calculated far earlier, and taken steps to prevent.

Another consideration should have figured much more prominently in his calculations: Spain. In early May 1811 Masséna was defeated by Wellington at the battle of Fuentes de Oñoro, after which the French were forced out of Portugal altogether, never to return. Napoleon replaced Masséna with Marmont – who did even worse against Wellington – and never employed ‘the darling child of victory’ in any significant capacity again. Yet Masséna had never been adequately supplied or reinforced, so his failure had been largely Napoleon’s fault. However, the situation in Spain in mid-1811 was not desperate; the guerrilla war still raged, but the Spanish regular army posed no serious danger. Wellington was far from Madrid on the Spanish–Portuguese border and most of the Spanish fortresses (except Cadiz) were in French hands. If Napoleon had not ordered a concentration on Valencia or had provided more reinforcements, or had taken command himself, the situation would have improved enormously, and perhaps even been reversed.47

Because of disease, desertion, guerrilla and British action, the Russian campaign and virtually no reinforcements, Napoleon had only 290,000 troops in the Iberian peninsula in 1812, and by mid-1813 the figure had fallen to a mere 224,000. As the annual intake of 80,000 French recruits was only just enough to cover the 50,000 per annum attrition rate in Spain and the need for garrison forces in central Europe, Napoleon simply did not have enough Frenchmen to conduct a major campaign in Russia.48 Had he cauterized the ‘Spanish ulcer’ by restoring Ferdinand and withdrawing to the Pyrenees in 1810 or 1811 he would have saved himself much trauma later on.

• • •

On April 17, 1811 Champagny, who opposed the coming war, was replaced as foreign minister by Hugues-Bernard Maret, later Duc de Bassano, a bureaucrat who has been described as docile, even servile, and who certainly wouldn’t cause any difficulties.49Napoleon’s Russian plans were more or less vocally criticized by Cambacérès, Daru, Duroc, Lacuée and Lauriston, as well as by Caulaincourt and Champagny.50 Perhaps they did not all warn quite so presciently or loudly as they later claimed, but nonetheless they all counselled to some degree against a confrontation with Russia. Part of the problem was that many of those to whom in earlier years Napoleon might have had to listen were now unavailable: Moreau and Lucien were in exile in America and Britain respectively; Talleyrand, Masséna and Fouché were in disgrace; Desaix and Lannes were dead. Furthermore, Napoleon had been proved right against the advice of others too often in the past for him to feel that the nay-sayers were right, even when there were a number of them. Almost all the French diplomatic service opposed the war, but Napoleon didn’t heed them either.51 He had no intention of going deep into the Russian interior, so a war did not seem at the time like any great gamble. Besides, he had succeeded through audacity before.

Caulaincourt – who had been replaced by Lauriston as ambassador to St Petersburg in mid-May and brought back to Paris so that Napoleon could call on his inside knowledge of Russia during the coming crisis – spent five hours one day in June 1811 trying to persuade the Emperor not to go to war against Russia. He told him of Alexander’s admiration for the Spanish guerrillas’ refusal to make peace despite losing their capital, of Alexander’s remarks about the severity of the Russian winter, and of his boast ‘I shall not be the first to draw my sword, but I shall be the last to sheathe it.’52 He said that Alexander and Russia had fundamentally changed since Tilsit, but Napoleon replied, ‘One good battle will see the end of all your friend Alexander’s fine resolutions – and of his sandcastles as well!’53 Napoleon crowed similarly to Maret on June 21: ‘Russia appears to be frightened since I picked up the gauntlet, but nothing is yet decided. The object of Russia seems to be to obtain, as an indemnity for the Duchy of Oldenburg, the cession of two districts of Poland, which I will not consent to, by honour and because they would altogether destroy the Grand Duchy.’54

By ‘honour’ Napoleon meant his prestige, but he obviously didn’t realize that he would be risking honour, prestige and his throne itself over two Polish districts and the so far non-existent integrity of the Grand Duchy of Warsaw. Still expecting a campaign of the Austerlitz–Friedland–Wagram kind, Napoleon believed that a sharp, focused re-run of his 1807 campaign – albeit on a larger scale – would not entail great risk. Yet three emergency levies in 1812 raised no fewer than 400,000 new recruits for Russia, out of 1.1 million new recruits in the period 1805–13. Napoleon failed to take into account the fact that he would be fighting a very different Russian army from earlier ones, though one with the same doggedness that had aroused his admiration at Pultusk and Golymin. Over half of the Russian officer corps were seasoned veterans and one-third had fought in six or more battles. Russia had changed, but Napoleon had not noticed. So while not actively seeking war, Napoleon was more than willing to ‘pick up the gauntlet’ that was thrown down by Alexander’s ukaz.

• • •

Another good reason not to embark on another war came in July 1811 when it became clear that the harvest had failed across northern France in Normandy, and in much of the Midi, leading to what Napoleon privately described as famine.55 Subsidizing the baking industry to prevent civil unrest turned into what the minister concerned, Pasquier, called ‘an immense burden for the government’. By September 15 a 4-pound loaf had nearly doubled in price to 14 sous and Napoleon was ‘most reluctant’ to see that figure exceeded.56 He chaired a Food Committee which met frequently, investigating price controls while, in Pasquier’s words, ‘Anxiety began to give way to terror’ in the countryside. With violence breaking out in corn-markets, gangs of starving beggars roaming the Norman countryside and flour-mills being pillaged and even destroyed, Napoleon at one point ordered the gates of Paris closed to prevent the export of bread. He also distributed 4.3 million dried-pea and barley soups.57 Troops were sent into Caen and other towns to quell bread riots, and rioters (including women) were executed. In the end a combination of price controls of grain and bread, charitable efforts by the notables of departments as co-ordinated by prefects, soup-kitchens, the sequestration of food stocks and harsh punishments for rioters helped alleviate the problem.58

Although Lauriston and Rumiantsev continued negotiating over compensation for the Oldenburg annexation and the amelioration of the ukaz during the summer of 1811, preparations for war continued on both sides of the Polish border. On August 15 Napoleon confronted Ambassador Kurakin at his birthday reception at the Tuileries. He had a long history of addressing ambassadors in very forthright language – including Cardinal Consalvi over the Concordat, Whitworth over Amiens, Metternich on the eve of the 1809 war, and so on – but full and frank discussions are partly what ambassadors are for. In a half-hour rebuke, the Emperor now told Kurakin that Russia’s support for Oldenburg, her Polish and (supposedly) English intrigues, her breaking of the Continental System and her military preparations meant that war seemed likely, yet she would be left alone and friendless like Austria had been in 1809. All this could be avoided if there were a new Franco-Russian alliance. Kurakin said he had no powers to negotiate such a thing. ‘No powers?’ Napoleon exclaimed. ‘Then you must write at once to the Tsar and request them.’59

The next day Napoleon and Maret went through the laborious process of looking into all the issues of the Oldenburg compensation, recognition of Poland, Turkish partition plans and the Continental System, reviewing all the papers on those subjects going back to Tilsit. These convinced him that the Russians had not been negotiating in good faith, and that evening he told the Conseil d’État that although a campaign against Russia in 1811 was impossible for climatic reasons, once Prussian and Austrian co-operation was assured, Russia would be punished in 1812.60 Russia’s hopes for military conventions with Prussia and Austria were dashed by those countries for fear of Napoleon’s reprisals, although both gave Alexander secret oral assurances that their support to the French would be minimal, rather as the Russian attack on Austria in 1809 had been. Metternich’s word for it was ‘nominal’.

The seriousness of Napoleon’s intentions can be ascertained by his renewed focus on the condition of the army’s shoes. A report in the Archives Nationales from Davout to Napoleon on November 29 stated: ‘In the 1805 campaign many men stayed behind for lack of shoes; now he is accumulating six pairs for each soldier.’61 Soon afterwards, Napoleon ordered his director of war administration, Lacuée, to supply provisions for 400,000 men for a fifty-day campaign, requiring 20 million rations of bread and rice, 6,000 wagons to carry enough flour for 200,000 people for two months, and 2 million bushels of oats to feed horses for fifty days.62 The weekly reports in the war ministry archives are testament to the huge operation taking place in early 1812. On February 14, 1812, to take an example almost at random, French troops were heading eastwards to over twenty German cities from all over the western part of the Empire.63 Further indication of Napoleon’s thinking can be seen in his order in December 1811 to his librarian, Barbier, to collect all the books he could find on Lithuania and Russia. These included several accounts, including Voltaire’s, of Charles XII of Sweden’s catastrophic invasion of Russia in 1709 and the annihilation of his army at the battle of Poltava, but also a five-hundred-page description of Russia’s resources and geography and two recent works on the Russian army.64*

In early January 1812 the Tsar, who still had six months to avert war if he cared to, wrote to his sister Catherine: ‘All this devilish political business is going from bad to worse, and that infernal creature who is the curse of the human race becomes every day more abominable.’65 Alexander was receiving reports from Chernyshev’s spy codenamed ‘Michel’, who worked in the transport department of the war administration ministry in Paris until his arrest and execution with three accomplices in late February 1812. These reports revealed to Alexander the vast extent of France’s war preparations and troop movements, and even Napoleon’s order of battle.66

On January 20, in another short-sighted act, France annexed Swedish Pomerania in order to enforce the Continental System along the Baltic coast. Cambacérès recalled that Napoleon had shown ‘little tact’ with Bernadotte, who after all had become a royal prince and deserved a new degree of respect. The annexation threw Sweden into the hands of the Russians, with whom she had been at war as recently as September 1809.67 Instead of establishing a useful ally in the north, capable of drawing Russian troops away from his own, Napoleon had ensured that Bernadotte would sign a treaty of friendship with Russia, which he did at Åbo on April 10, 1812.

In February Austria agreed to furnish Napoleon with 30,000 men under Prince von Schwarzenberg for the invasion, but as Metternich told the British Foreign Office, ‘It is necessary that not only the French Government but the greater part of Europe should be deceived as to my principles and intentions.’68 At the time, Metternich had no discernible principles, and his intention was simply to see how the invasion of Russia would go. A week later Prussia promised 20,000 men, whereupon fully a quarter of the Prussian officer corps resigned their commissions in protest, many of them, such as the strategist Carl von Clausewitz, actually joining the Russians.69 Napoleon used to say, ‘It’s better to have an open enemy than a doubtful ally,’ but he did not act according to that belief in 1812.70 With Davout reporting on the huge size of the Russian army, he believed he needed as many foreign contingents as possible, and he needed them to be well armed.71 ‘I have ordered the light horse to be armed with carbines,’ he had written to Davout on January 6. ‘I would also like the Polish to have them; I learned that they only have six per company, which is ridiculous, given they have to deal with the Cossacks, who are armed from head to foot.’72

On February 24 Napoleon wrote to Alexander saying that he had ‘decided to talk with Colonel Chernyshev about the unfortunate events that have occurred over the last fifteen months. It only depends on Your Majesty to end it all.’73 The Tsar rebuffed this further open-ended effort at peace. On the same day Eugène started marching 27,400 men of the Army of Italy to Poland. According to Fain, Napoleon briefly considered dismembering Prussia at this time, and so ‘secure, from the first cannon-shot, an indemnity against all the unfavourable risks of a Russian campaign’.74 With the Russians having gathered more than 200,000 men between St Petersburg and the Grand Duchy of Warsaw, however, he had to face what he considered to be a serious Russian threat and could not afford to cause chaos in his rear.*

Although Napoleon hoped for another swift victory, he gave his enemies far more time to organize in 1811–12 than in any of his earlier campaigns. From the moment that the first mobilization orders went out to Rhine Confederation contingents in early 1811, the Russians had well over a year to prepare, time that they used extremely well. In all his other campaigns Napoleon’s opponents had been lucky if they had a matter of weeks to get ready for his onslaught. Although the plan to concentrate forces upon Drissa that General von Phull drew up in the spring of 1812 wasn’t adopted, the Russian high command was constantly thinking through alternative strategies, and certainly out-thinking Napoleon’s by then transparent strategy of a quick decisive battle fought on the border.

Although Napoleon called it the ‘Second Polish Campaign’, he privately told his staff, ‘We don’t have to listen to inconsiderate zeal for the Polish cause. France before anything else: those are my politics. The Poles aren’t the subject of this fight; they mustn’t be an obstacle to peace, but they might be a tool of war for us, and, on the eve of such a great crisis I will not leave them without advice or guidance.’75 He appointed the Abbé de Pradt as French ambassador to Warsaw. ‘The campaign began without any provisioning, which was Napoleon’s method,’ Pradt later wrote in his (violently anti-Napoleon) memoirs. ‘Some admiring imbeciles believe it was the secret of his success.’76 Though untrue – there was plenty of provisioning at the start of the campaign – it was a fair criticism later on, partly due to the negligence and incompetence of Pradt himself as Poland was the major supply depot for the campaign. Napoleon’s other possible appointee for Pradt’s post had been Talleyrand. That either was considered was a sign of how his usual good judgement of people (and continuing lacuna over Talleyrand) had begun to slip badly.

It took Napoleon dangerously long to realize that Alexander was about to pull off significant diplomatic coups in both the north and south, allowing him to concentrate his forces against the coming invasion. As late as March 30, 1812 he told Berthier, ‘I assume the Russians will avoid making any movement, they cannot be unaware that Prussia, Austria and probably Sweden are with me; that with hostilities starting again with Turkey, the Turks will make new efforts, that the Sultan himself is going to join the army, and that all this makes it unlikely they will defy me easily.’77 In fact Napoleon had lost the north flank through his inability to treat Bernadotte and Sweden with respect and indulgence, and in late May 1812 he also lost the south flank, despite sending General Andreossy to Constantinople to tell Sultan Mahmud II ‘If one hundred thousand Turks, their Sultan at their head, went through the Danube, I promise in exchange not only Moldavia and Wallachia, but also the Crimea.’78 Alexander matched Napoleon’s offer over the Danubian provinces and signed the Treaty of Bucharest with Turkey on May 29, which meant that the Russian Army of the Danube could begin to threaten Napoleon’s southern flank.

‘The Turks will pay dearly for this mistake!’ Napoleon said on hearing news of the treaty. ‘It is so stupid that I couldn’t foresee it.’79 But the stupidity in this instance was in fact his – he had counted too complacently on Ottoman support. In turning back Napoleon at Acre in 1799, and by allowing Russia to redeploy her Balkan forces against him in 1812, the supposed ‘sick man of Europe’ was in fact instrumental in two of Napoleon’s major reverses. ‘If I’m ever accused of having provoked this war,’ Napoleon told Fain in August, ‘please consider, to absolve me, how little my cause was linked with the Turks, and how harassed I was by Sweden!’80

• • •

By March 15 all the Grande Armée’s corps had reached the Elbe. That same day Napoleon ordered Louis Otto, the French ambassador in Vienna, to buy 2 million bottles of Hungarian wine at 10 sous each, to be delivered to Warsaw.81 To strengthen the invasion force, Belgian National Guard units replaced French troops in garrisons along the Atlantic coast, Princess Pauline Borghese’s bodyguard were called up, cannon were stripped from the navy and the hospitals scoured for malingerers. Reserve units were disbanded and reassembled to maximize the numbers that could go to Russia; the 10th Cohort of the Paris National Guard, for example, was soon almost entirely comprised of men with flat feet.82

On April 8, a week after the Grande Armée had reached the Oder, Alexander issued an ultimatum ordering Napoleon immediately to evacuate his troops from Prussia, Swedish Pomerania and the Grand Duchy of Warsaw and to reduce the Danzig garrison. This was to be a preliminary to a new settlement of the frontiers of Europe, under which Russia would be allowed to trade with neutrals but would negotiate compensation for Oldenburg and reduce Russian duties on French goods.83 These terms would clearly be unacceptable to Napoleon, and in any case sounded more like a propaganda bulletin than genuine bases for negotiation. On April 21 Alexander left St Petersburg for his army base at Vilnius. On the 17th Napoleon had made a peace offer to the British foreign secretary, Lord Castlereagh, saying that he would withdraw from the Iberian peninsula if the British did too, and that Sicily could stay Bourbon if Murat was recognized as king of Naples and Joseph as king of Spain. ‘If this fourth attempt should be unsuccessful,’ he concluded of his various peace offers since the breakdown of Amiens, ‘as those that have preceded it, France will at least have the consolation of thinking that the blood that could flow again will fall entirely on England.’84 It was cheekily opportunistic – especially the absurd provision regarding Joseph and Murat – and Castlereagh, as befitting a true disciple of Pitt, treated it with predictable contempt.

On April 25 Napoleon sent his aide-de-camp General Comte Louis de Narbonne-Lara (who was probably the illegitimate son of Louis XV) with more realistic counter-proposals to the Tsar’s ultimatum that didn’t involve evacuations from allies’ territory. ‘These will prove to Your Majesty my desire to avoid war and my steadfastness in the sentiments of Tilsit and Erfurt,’ Napoleon wrote. ‘However, Your Majesty will allow me to assure you that, if fate makes war between us inevitable, it would not change the sentiments that Your Majesty has inspired in me and which are safe from any alteration and vicissitude.’85 Historians have tended to view cynically Napoleon’s repeated attempts to stay personally friendly with a head of state of a country he was about to ravage, yet it was part of his belief in the almost ethereal brotherhood of emperors that this should be possible. Their time at Tilsit together had clearly meant much more to him than it had to Alexander. Speaking to Pasquier in May before he left for the front, Napoleon described the coming campaign against Russia as ‘The greatest and most difficult enterprise I’ve ever attempted. But what has been begun must be carried through.’86

• • •

At 6 a.m. on Saturday, May 9, Napoleon left Saint-Cloud with Marie Louise and the baby King of Rome to make his way to the front. The day before he had imposed wheat taxes and swingeing food-price controls. ‘In this way he hoped to ensure that they would remain contented during his absence,’ Pasquier concluded, but it was only a short-term solution.87 As always he moved fast: the imperial family passed the Rhine on the 13th, the Elbe on the 29th and the Vistula on June 6, travelling 530 miles in seven days and averaging over 75 miles a day in a horse-drawn carriage over unmetalled, rutted roads. There was nonetheless time for meetings in Dresden with the kings of Württemberg, Prussia, Saxony and Bavaria, the first of whom had refused to send a contingent to Spain in 1810, but would against Russia; the last was still angry that Napoleon had never reimbursed him for the expenses of the war of 1805, but nonetheless sent a contingent too. Marie Louise saw her father there for the first time since her wedding; Napoleon saw him for the first time since they had met at the windmill near Austerlitz. Francis also met his grandson. The King of Rome was attended by his governess Madame de Montesquieu, whose official title, ‘Governess to the Imperial Children’, indicates that Napoleon and Marie Louise hoped for more. Indeed, Napoleon later said he would have liked another son for the Kingdom of Italy and a third to be safe.

Metternich much later claimed that when they met in Dresden Napoleon had told him his Russian strategy. ‘Victory will go to the most patient,’ the Emperor supposedly said, according to Metternich’s unreliable and immensely self-serving memoirs. ‘I shall open the campaign by crossing the Niemen, and it will be concluded at Smolensk and Minsk. There I shall stop and fortify those two points. At Vilnius, where the main headquarters will spend next winter, I shall busy myself with organizing Lithuania . . . Perhaps I myself shall spend the most inclement months of the winter in Paris.’88 On being asked what would happen if Alexander didn’t sue for peace, Napoleon allegedly replied: ‘In that case I shall advance next year to the centre of the empire, and I shall be patient in 1813 as I have been in 1812!’ Whether Napoleon genuinely vouchsafed such secrets to a man he must have suspected didn’t want him to be victorious in Russia, and had excellent connections with the Russians, might be doubted.

Leaving Marie Louise with her parents in Dresden when he left at dawn on May 29, Napoleon wrote later that morning that he would be back within two months. ‘All my promises to you shall be kept,’ he said, ‘thus our absence from each other will be but a short one.’89 It was to be nearly seven months before he saw her again. Going eastwards via Bautzen, Reichenbach, Hainau, Glogau, Posen, Thorn, Danzig and Königsberg, he reached the banks of the Niemen by June 23. He deliberately didn’t go to Warsaw, where, if he had proclaimed the Kingdom of Poland, he could have raised, one Russian general estimated, 200,000 men and turned the ethnically Polish provinces of Lithuania, Volhynia and Polodia against the Tsar.90 Instead he preferred not to antagonize his Prussian and Austrian allies.

At 1 a.m. on the night of June 4, Colonel Maleszewski, one of Napoleon’s staff officers, heard the Emperor pacing up and down his room in Thorn, singing the verse from ‘Le Chant du Départ’ that includes the line ‘Tremblez, ennemis de la France.’91 On that day alone, Napoleon had written letters to Davout complaining of the marauding of Württemberger troops in Poland, to Clarke about raising a company of Elban sappers, to Marie Louise to say that he had been twelve hours in the saddle since 2 a.m., to Cambacérès that the frontier was quiet, to Eugène ordering 30,000 bushels of barley, and no fewer than twenty-four letters to Berthier about everything from a paymaster who should be punished for incompetence to a fever hospital that needed to be relocated.92Preparing for the attack on Russia caused Napoleon to write nearly five hundred letters to Berthier between the beginning of January 1812 and the crossing of the Niemen, and another 631 to Davout, Clarke, Lacuée and Maret between them.

On June 7 staying in Danzig with Rapp – to whom he was far more likely to speak about his strategic thinking than to Metternich – Napoleon said his plans were limited to crossing the Niemen, defeating Alexander and taking Russian Poland, which he would unite to the Grand Duchy, turn into a Polish kingdom, arm extensively and leave with 50,000 cavalry as a buffer state against Russia.93 Two days later he expanded further to Fain and others:

While we finish with the north, I hope that Soult will maintain himself in Andalusia and that Marmont will contain Wellington on the Portuguese border. Europe will breathe only when these affairs with Russia and Spain are over. Only then can we reckon on a true peace; reviving Poland will consolidate it; Austria will take care of more of the Danube and less of Italy. Finally, exhausted England will resign herself to share the world’s trade with continental vessels. My son is young, you have to prepare him for a quiet reign.94

These war aims – even for peace with Britain, against whom America had declared war on June 1 – were limited and possibly even achievable, and certainly far from the lunatic hubris with which Napoleon is generally credited on the eve of his invasion of Russia. There was no word of marching to Moscow, for example (any more than there had been in his supposed heart-to-heart with Metternich). Against the French Empire’s 42.3 million inhabitants, and a further 40 million living in the ‘Grand Empire’ of satellite states, Russia’s population in 1812 was about 46 million.95 Napoleon had fought against the Russians twice before and had defeated them on both occasions. His army of over 600,000 men was over twice the size of the Russian army in the field at the time. On June 20 he specified only twelve days’ marching rations for the Imperial Guard, implying that he was hoping for a short campaign – certainly not one that would take him over 800 miles from the Niemen to Moscow.

• • •

On June 22 Napoleon issued his second bulletin of the campaign:

Soldiers! The Second Polish War has commenced. The first ended at Friedland and Tilsit. At Tilsit, Russia swore an eternal alliance with France, and war with England. Today she violates her oaths . . . Does she believe us degenerate? Are we no longer the soldiers of Austerlitz? She places us between dishonour and war; the choice cannot be in doubt . . . Let us cross the Niemen! . . . The peace which we shall conclude shall put an end to the baneful influence which Russia has for fifty years exercised over the affairs of Europe.96

Not since his hero Julius Caesar crossed the Rubicon in 49 BC had the traversing of a river held a heavier portent than when Napoleon’s vast army started crossing the Niemen into Russia before dawn on Wednesday, June 24 1812. Since Lauriston had been sent away from Alexander’s headquarters without reply to Napoleon’s last-minute peace offer a few days before, there was no need for a formal declaration of war, any more than there had been at the outbreak of the War of Austrian Succession or the Seven Years War.

While Napoleon was reconnoitring the river on the day of the crossing, his horse shied at a hare and threw him onto the sandy riverbank, leaving him with a bruised hip.97 ‘This is a bad omen, a Roman would recoil!’ someone exclaimed, although it is not known whether it was Napoleon himself or one of his staff who said it – but with his penchant for ancient history (and the understandable reluctance of anyone else to make that obvious point) it may well have been the Emperor himself.98 Napoleon had ordered the artillery commander-turned-engineer General Jean-Baptiste Éblé to throw three pontoon bridges over the river near a village called Poniémen, and he spent the rest of the day in his tent and in a nearby house, in Ségur’s words, ‘listlessly reclining in the midst of a breathless atmosphere and a suffocating heat, vainly courting repose’.99

The sheer size of Napoleon’s army is hard to compute. He had over 1 million men under arms in 1812; once he subtracted garrisons, reserves, eighty-eight National Guard battalions, soldiers in the 156 depots back in France, various coastal artillery batteries and twenty-four line battalions stationed around the Empire, as well as the men in Spain, he was left with 450,000 in the first line with which to invade Russia and 165,000 mobilized in the second. A reasonably accurate total might therefore be 615,000, which was larger than the entire population of Paris at the time.100 It was certainly the largest invasion force in the history of mankind to that time, and very much a multi-national one. Poles made up the largest single foreign contingent, but it also comprised Austrians, Prussians, Westphalians, Württembergers, Saxons, Bavarians, Swiss, Dutch, Illyrians, Dalmatians, Neapolitans, Croats, Romans, Piedmontese, Florentines, Hessians, Badeners, Spaniards and Portuguese. Much has been made of the breadth of the seven coalitions that Britain brought together against France during the Napoleonic Wars, which is indeed impressive and significant, but the broadest coalition of all was this one that fought for France against Russia.101 Some 48 per cent of Napoleon’s infantry were French and 52 per cent foreign, whereas the cavalry was 64 per cent French and 36 per cent foreign.102 Even the Imperial Guard had Portuguese and Hessian cavalry units in it, and a squadron of Mamluks were attached to the Chasseurs à Cheval of the Old Guard. The problem with relying so heavily on foreigners was that many felt, as the Württemberger Jakob Walter’s journal admitted, ‘total indifference as to the outcome of the campaign’, treating French and Russians alike and certainly feeling no personal loyalty to Napoleon.103 No amount of haranguing would convert a Prussian, for example, to an ardent adherence to the French cause.

The numbers of men involved and the distances over which they were spread forced Napoleon to adopt a different army formation from the six or seven corps he had previously used. The first line was organized into three army groups. The central one under Napoleon’s personal command had 180,000, mostly French soldiers. It included Murat with two corps of reserve cavalry, the Imperial Guard, Davout’s and Ney’s corps and Berthier’s general staff, which itself now numbered nearly 4,000. On his right was Eugène’s 4th Corps of 46,000 men with Junot as his chief-of-staff, and the 3rd Reserve Cavalry Corps, with Poniatowski’s 5th Corps even further to the south. On Napoleon’s left was Oudinot’s corps, guarding the northern flank. In total the Grande Armée had over 1,200 guns.104

Napoleon invaded Russia with around 250,000 horses – 30,000 for the artillery, 80,000 for the cavalry and the rest pulled 25,000 vehicles of every kind – yet the supply of forage for so many horses was entirely beyond any system Napoleon or anyone else could have put into effect.105 He delayed the invasion until forage would be plentiful, but nonetheless the heat and their diet of wet grass and unripe rye killed 10,000 horses in the first week of the campaign alone.106 As horses required 20 pounds of forage per day, he had a maximum of three weeks before supplies would start to become inadequate. There were twenty-six transport battalions, eighteen of which consisted of six hundred heavy wagons drawn by six horses each, capable of transporting nearly 6,500 pounds, but the wagons were quickly found to be too heavy for Russian roads once they turned to mud, as ought to have been remembered from the First Polish Campaign.107 The men had four days’ food supply on their backs and a further twenty in the wagons following the army – enough for the very short campaign Napoleon envisaged, but if he had not comprehensively defeated the main Russian army within a month of crossing the Niemen, he would need either to withdraw or to stop and resupply. The critical moment of the campaign should therefore fall in the third week of July, if not earlier.

But the army that was crossing the Niemen was no longer the highly mobile entity of Napoleon’s earlier campaigns, designed to catch and swiftly envelop the enemy. Napoleon’s headquarters alone required 50 wagons pulled by 650 horses.108 Murat took along a famous Parisian chef, and many officers packed their evening dress and brought their private carriages.109 Many of the phenomena of Napoleonic warfare that had been characteristic of his earlier campaigns – elderly opponents lacking energy, a nationally and linguistically diverse enemy against the homogeneous French, a vulnerable spot onto which Napoleon could latch and not let go, a capacity for significantly faster movement than the enemy, and to concentrate forces to achieve numerical advantage for just long enough to be decisive – were not present or were simply impossible in the vast reaches of European Russia. The Russian generals tended to be much younger than the generals Napoleon had faced in Italy – averaging forty-six years old against the French generals’ forty-three – and the Russian army was more homogeneous than Napoleon’s. This was to be a campaign utterly unlike any he had fought before, indeed unlike any in history.