24

‘He didn’t want to conquer Russia, not even to re-establish Poland; he had only renounced the Russian alliance with regret. But conquering a capital, signing a peace on his terms and hermetically sealing the ports of Russia to British commerce, that was his goal.’

Champagny’s memoirs

‘Rule one on page one of the book of war, is: “Do not march on Moscow.”’

Field Marshal Viscount Montgomery, House of Lords, May 1962

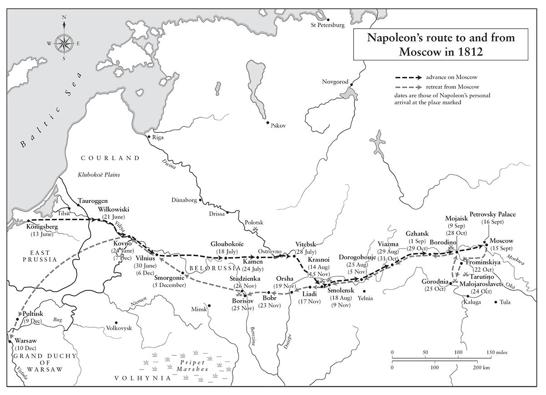

Napoleon crossed the River Niemen at 5 a.m. on June 24, 1812, and then stationed himself on a hillock nearby as his soldiers marched past crying, ‘Vive l’Empereur!’1 He hummed the children’s song ‘Malbrough s’en va-t’en guerre’ to himself. (‘Marlborough is going to war, / who knows when he’ll be back?’)2 He wore a Polish uniform that day, and equally symbolically rode a horse named Friedland. That afternoon he went on to cross the Viliya river and entered Kovno. It took five days for the whole army to make it across the river.

Although Russia had 650,000 men under arms in 1812, they were spread out widely across her Empire – in Moldavia, the Caucasus, central Asia, the Crimea, Siberia, Finland and elsewhere – with only around 250,000 men and guns, organized in three armies, facing Napoleon in the west. Barclay de Tolly’s First Army of the West, of 129,000 men, was widely deployed either side of Vilnius; Bagration’s Second Army of the West, of 48,000 was 100 miles to the south of Vilnius at Volkovysk; and General Alexander Tormasov’s Third Army of the West, of 43,000 was coming from much further south, freed from Danubian service by the Russo-Turkish peace. Napoleon wanted to keep these three forces separate and to defeat them piecemeal. He sent Eugène and Jérôme out on wide enveloping movements in the hope of surrounding Bagration’s Second Army before it could join Barclay’s First Army. Why he chose to give this vital task to his stepson and brother rather than to senior, experienced soldiers such as Davout, Murat or Macdonald is unclear. Jérôme had commanded the 9th Corps during the 1806–07 campaign (the army’s German contingent) but had not particularly distinguished himself. ‘The heat is overpowering,’ Napoleon wrote to Marie Louise from the convent at Kovno where he had set up his headquarters, adding: ‘You can present the University with a collection of books and engravings. This will please it vastly and will cost you nothing. I have plenty of them.’3

Opinion in the Russian high command was split between the aristocratic generals who supported Bagration’s counter-offensive strategy and the ‘foreigners’ (often Baltic Germans) who supported Barclay de Tolly’s strategy of withdrawal, essentially that of Bennigsen in 1807 except across a far wider area. By the time Napoleon crossed the Niemen the latter had won, partly because the sheer size of the Grande Armée made a counter-offensive unthinkable. Having a smaller army would therefore paradoxically have helped Napoleon by tempting the Russians into the early battle he logistically needed to fight, and would also have allowed him (because of its lesser supply needs) more time to fight it. Had Alexander appointed the Russian-born Bagration as war minister and commander of the First Army of the West instead of Barclay – an appointment that would have been popular in the Russian officer corps – Napoleon might have destroyed the Russian army at, or even before, Vilnius. Instead he picked the less flamboyant, more incisive Barclay and stuck by Barclay’s plan to lure the Grande Armée deep into Russian territory, stretching its supply lines away from the huge military depots in Mainz, Danzig, Königsberg and elsewhere.

Napoleon entered Vilnius, the capital of Polish Lithuania, on June 28 and turned it into a massive supply centre, the Russians having removed or burned all theirs before they left. He told Marie Louise that he had chosen for his headquarters ‘a rather fine mansion where the Emperor Alexander was living a few days ago, very far from thinking at the time that I was so soon to enter here’.4 Half an hour before Napoleon made his entry into the city, he ordered a Polish artillery officer on his staff, Count Roman Soltyk, to fetch Jan Sniadecki, the renowned astronomer, mathematician and physicist, and rector of Vilnius University, to talk to him there. When Sniadecki insisted on putting on silk stockings before leaving his house, Soltyk expostulated: ‘Rector, it doesn’t matter. The Emperor attaches no importance to exterior things which only impress the common people . . . Let’s be off.’5

‘Our entry into the city was triumphal,’ wrote another Polish officer. ‘The streets . . . were full of people, all the windows were garnished with ladies who displayed the wildest enthusiasm.’6 Napoleon showed characteristic sensitivity to public opinion by having himself preceded and followed by Polish units in the procession. He set up a provisional government for the Lithuanian Poles there, and Lithuania was ceremonially reunited with Poland in a ceremony at Vilnius cathedral. At Grodno French troops were met by processions with icons, candles and choirs blessing them for the ‘liberation’ from Russian rule.* A Te Deum was sung in Minsk, where General Grouchy handed around the collection plate, but once the rural population heard that the French troops were requisitioning food, as they always did on campaign, they herded their livestock into the forests. ‘The Frenchman came to remove our fetters,’ said the Polish peasants in western Russia that summer, ‘but he took our boots too.’7

‘I love your nation,’ Napoleon told the representatives of the Polish nation at Vilnius. ‘For the last sixteen years I have seen your soldiers at my side in the battles in Italy and Spain.’ He offered Poland ‘my esteem and protection’. With Schwarzenberg protecting his southern flank, however, he needed to add: ‘I’ve guaranteed to Austria the integrity of her states, and I cannot authorize anything that will tend to trouble her in the peaceful possession of what remains to her of her Polish provinces.’8 He was having to perform a delicate balancing act.

He stayed ten days in Vilnius to allow much of the army to rest, regroup and allow that part of the right wing of the army that was under the untried and untested Jérôme – comprising two of Davout’s divisions, Schwarzenberg’s Austrians, Poniatowski’s Poles and Reynier’s Saxons, 80,000 men in all – to advance towards the lower Berezina river and try to pincer Bagration’s army. The vanguards moved on and on June 29 the broiling heat broke in a great hailstorm and deluge of rain, after which Sergeant Jean-Roch Coignet of the Imperial Guard noted that ‘in the cavalry camp nearby, the ground was covered with horses which had died of cold’, including three of his own.9 The rain also made the ground boggy and roads muddy, causing supply problems and slowing down the vanguards in pursuit of the Russians. In some marshes and swamps men waded up to their chins.10

Berthier wrote to Jérôme from Vilnius on June 26, the 29th and the 30th encouraging him to keep in close proximity to Bagration and to capture Minsk.11 ‘If Jérôme pushes strongly ahead,’ Napoleon told Fain, ‘Bagration is deeply compromised.’12 With Jérôme moving in from the west and Davout from the north, Bagration ought to have been crushed between them at Bobruisk, but Jérôme’s bad generalship, as well as Bagration’s skill at withdrawal, meant that the Russian Second Army escaped. By July 13 it was clear that Jérôme had failed. ‘If it had been more rapid and better concerted between the Corps of the army,’ General Dumas, the intendant-general, later opined, ‘the object would have been obtained and the success of the campaign decided at the very opening.’13When Napoleon learned of the failure he appointed Davout to command Jérôme’s army. His outraged youngest brother resigned his command and flounced back to Westphalia only three weeks into the campaign.14

‘The weather is very rainy,’ Napoleon wrote to Marie Louise from Vilnius on July 1, ‘the storms in this country are terrible.’15 Although we don’t have her letters to him, the Empress wrote one every other day that month. ‘God grant I may soon meet the Emperor,’ she told her father at this time, ‘for this separation weighs much too heavily upon me.’16 As well as mentioning his state of health – almost always positively – Napoleon asked after his son in every letter he wrote, begging for news about ‘whether he is beginning to talk, whether he is walking’ and so on.

• • •

On July 1, Napoleon received Alexander’s aide-de-camp, General Alexander Balashov, who told him somewhat belatedly that Napoleon could still withdraw from Russia and avoid war. He wrote Alexander a very long letter reminding the Tsar of his anti-British remarks at Tilsit, and pointing out that at Erfurt he had accommodated Alexander’s needs with regard to Moldavia, Wallachia and the Danube. Since 1810, he said, the Tsar had ‘rearmed on a large scale, declined the path of negotiations’ and demanded modifications to the European settlement. He recalled ‘the personal esteem which you have sometimes shown to me’ but said that the ultimatum of April 8 to withdraw from Germany had been designed ‘clearly to place me between war and dishonour’.17 Even though ‘for eighteen months you have refused to explain anything’, Napoleon wrote, ‘My ear will always be open to peace negotiations . . . you will always find in me the same feelings and true friendship.’ He blamed the Tsar’s bad advisors and Kurakin’s arrogance for the war, using a phrase he had employed in writing to the Pope, the Emperor of Austria and others in the past: ‘I pity the wickedness of those who gave Your Majesty such bad advice.’ Napoleon then argued that if he had not had to fight Austria in 1809, ‘the Spanish business would have been ended in 1811, and probably peace would have been brokered with England at that time.’ In conclusion, Napoleon offered:

a truce on the most liberal grounds, such as not considering men in hospital as prisoners – so that neither side has to hurry evacuations, which involves heavy losses – such as the return every two weeks of prisoners made by either side, using a rank-for-rank exchange system, and all the other stipulations that the custom of war between civilized nations has allowed: Your Majesty will find me ready for anything.18

He ended by repeating that, notwithstanding the war between them, ‘the private feelings that I bear for you are not in the least affected by these events . . . [I remain] full of affection and esteem for your fine and great qualities and desirous of proving it to you.’*

Alexander took up none of Napoleon’s proposals. The Russians were retreating steadily before the Grande Armée – the first clash to cost either side more than a thousand casualties didn’t come for four weeks – but that didn’t mean they were offering no resistance. Recognizing that this war was going to be as much about logistics as battles, they systematically destroyed anything that couldn’t be removed. Crops, windmills, bridges, livestock, depots, fodder, shelter, grain – everything that could be of any use whatever to the oncoming French was either taken away or burned, for many miles on both sides of the road. Napoleon had done the same thing on his retreat from Acre, and had admired Wellington’s skilful execution of a similar scorched-earth policy while withdrawing to the Lines of Torres Vedras, for, as Chaptal recorded: ‘It was on traits like these that he judged the skill of generals.’19

Because eastern Poland and Byelorussia were grindingly poor and sparsely populated regions where malnutrition was common even in peacetime – unlike the lush and fertile grounds of northern Italy and Austria – there would always have been a serious supply problem when its backward agrarian economy was suddenly called upon to feed hundreds of thousands of extra mouths. Yet with entire villages set ablaze by the retreating Russians, the situation quickly became dire. Worse, there were squadrons of light Russian cavalry operating deep behind French lines, including a famously daring one led by Alexander Chernyshev, which threatened Napoleon’s lengthening lines of communication.20

No sooner was the violently wet weather of late June over than the baking sun returned; fresh water was in short supply and recruits fainted from exhaustion. The heat threw up a choking dust so thick that drummers had to be stationed at the head of battalions so that the men marching behind wouldn’t get lost. By July 5, because of bottlenecks of wagons on the pontoon bridges across rivers, the Grande Armée was facing severe food shortages. ‘Difficulties over food remain,’ noted the Comte de Lobau’s aide-de-camp Boniface de Castellane, ‘soldiers are without food and horses without oats.’21 When Mortier told Napoleon that several members of the Young Guard had actually died of hunger, the Emperor said: ‘It’s impossible! Where are their twenty days’ rations? Soldiers well commanded never die of hunger!’22 Their commander was brought, and stated, ‘either from weakness or uncertainty’, that in fact the men had died from intoxication, upon which Napoleon concluded that ‘One great victory would make amends for all!’23

An average of 1,000 horses were to die for every day of the 175 days that the Grande Armée spent in Russia. Ségur recalled that the more than 10,000 horses that died from dehydration and heat exhaustion, when unripe rye had been their only fodder, ‘sent forth a stench impossible to breathe’.24 Caulaincourt, Napoleon’s master of horse, was devastated. ‘The rapidity of the forced marches, the shortage of harness and spare parts, the dearth of provisions, the want of care, all helped to kill the horses,’ he recorded.

The men, lacking everything to supply their own needs, were little inclined to pay heed to their horses, and watched them perish without regret, for their death meant the breakdown of the service on which the men were employed, and thus the end of their personal privations. There you have the secret and cause of our earlier disasters and of our final reverse.25

As early as July 8 Napoleon had to write to Clarke in Paris to say that it wasn’t necessary to increase cavalry recruitment ‘since we are losing so many horses in this country that we will have great difficulty, with all the resources of France and Germany, in keeping the current number of men in the regiments mounted’.26

That same day Napoleon learned that the main Russian force, the First Army of the West, was at Drissa, a powerful fortress that was badly situated strategically. Filled with hope, he sent his advance guard there, but by the time they arrived there on the 17th they found it abandoned. On July 16 he was told that although Davout had captured Minsk, Bagration had managed to slip away again. Just before he left Vilnius, Napoleon dined with General de Jomini; they spoke of how close Moscow was – it was actually 500 miles away – and Jomini asked if he intended to march there. Napoleon burst out laughing, saying:

I much prefer to get there in two years’ time . . . If M. Barclay thinks that I want to run after him all the way to the Volga, he is very much mistaken. We shall follow him as far as Smolensk and the Dvina, where a good battle will allow us to go into cantonments. I shall return here, to Vilnius, with my headquarters to spend the winter. I shall send for an opera company and actors from the Théâtre-Français. Then, next May, we shall finish the job, if we do not make peace during the winter. That is better, I think, than running to Moscow. What do you say, Monsieur Tactician?27

Jomini agreed.

• • •

By then Napoleon was facing a devastating new threat for which no army of the day was prepared. Typhus fever is a disease of dirt; its causative organism, Rickettsia prowazekii, lies midway between the relatively large bacteria that cause syphilis and tuberculosis and the microscopic smallpox and measles viruses. Carried by lice which infest unwashed bodies in the seams of dirty clothing, the organism is not transferred by the louse’s bite but through its excrement and corpse.28 It had been endemic in Poland and western Russia for years.

Heat, lack of water for washing, troops packed together in large numbers at night, the hovels in which they sheltered, scratching irritable areas, not changing clothes: all were ideal conditions for spreading typhus. In the first week of the campaign alone, 6,000 men fell ill with it every day. By the third week of July over 80,000 men had either died or were sick, at least 50,000 of them from typhus. Within a month of the start of the invasion, Napoleon had lost one-fifth of the men in his central army group.29 Larrey, the Grande Armée’s surgeon-general, was a fine doctor, but typhus had not yet been medically linked to lice, which were thought of as an unpleasant pest but no killer, and he was at a loss to know how to respond. Dysentery and enteric fever were dealt with in hospitals in Danzig, Königsberg and Thorn, but typhus was different. Napoleon supported vaccination, especially for smallpox – he had had his son vaccinated at two months – but there was none to be had against typhus. Recent research on the DNA taken from the teeth of 2,000 corpses in a mass grave in Vilnius shows that they almost all carried the typhus exanthematicus pathogen, known as ‘war plague’. Ironically, Napoleon insisted that hospitalized men be made to bathe, but it wasn’t known that healthy men needed to as well.30Even the Emperor caught lice on the retreat from Moscow, when it was too cold to remove any of his clothes for days on end.31 The way to defeat them was to boil undergarments and iron outer garments with a hot iron, neither of which could be done in the sub-zero temperatures that first arrived on November 4.32

Typhus (which is quite different from typhoid fever, dysentery and the other ‘diseases of the poor’) had been a growing problem in France itself as the Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars progressed, with outbreaks prevalent in villages situated along the major roads. In the Seine-et-Marne, outbreaks were almost uninterrupted after 1806, as well as in the eastern Parisian communes where the troops arrived back from the Rhine. Mortality was heavy in 1810–12 and, when asked to explain this, the medical officers of Melun and Nemours agreed that the principal cause was ‘continual war’.33 Typhus returned when the Allied armies invaded France in 1814 and 1815. The most eminent physicians of the day assumed that it could break out spontaneously given ‘great hardship, colds, lack of the necessaries of life, and the consequent consumption of spoiled foodstuffs’.34 Even twenty years after the end of the wars, J. R. L. de Kerckhove, a former chief of French hospitals in 1812, understood the cause of typhus incorrectly, writing: ‘The typhus that had so decimated the French army had its origin in privation, fatigue and the polluted air that one breathes in places overflowing with the sick and the exhausted. Then it spread by contagion.’35 The connection between lice and typhus was not made until 1911. De Kerckhove got the symptoms absolutely right, however:

The infection manifested itself through general malaise, accompanied most often by a state of languor; a weak, slow or irregular pulse; an alteration in facial traits; a difficulty executing movements . . . extreme fatigue, difficulty standing, lack of appetite; vertigo, ringing in the ear, nausea, headaches were very frequent; sometimes he suffered from vomiting; sometimes the tongue was covered in a white or yellow mucus.

After about four days a fever developed which ‘was evident firstly in shaking followed by an irregular feeling of heat . . . the fever developed and became continual, the skin was dry . . . congestions of the brain and sometimes the lung’.36 In most cases, death followed. Up to 140,000 of Napoleon’s soldiers died of disease in 1812, the majority of them from typhus but a significant number from dysentery and related illnesses.

Napoleon could not allow disease to derail the entire invasion, and pressed on eastwards in the hope of keeping the Russian First and Second Armies of the West separate. He himself was, in the estimation of the ordnance officer attached to his staff, Captain Gaspard Gourgaud, ‘in excellent health’ during the campaign, spending hours a day on horseback with no serious illnesses reported.37 The speed of the Grande Armée’s advance and the rawness of the young recruits meant that many could not keep up. ‘Stragglers are committing awful horrors,’ wrote Castellane, ‘they are sacking and pillaging: mobile columns are organized.’38 On July 10 Napoleon ordered Berthier to send a column of gendarmes to Vorovno ‘to arrest the pillagers of the 33rd, who are committing horrible devastation in that country’.39 By mid-July troops were also deserting in bands.

On July 18 Napoleon arrived at Gloubokoïé, where he stayed for four days in the Carmelite convent, attending Mass, setting up a hospital, inspecting the Guard and hearing reports about the severe problems the army was facing as a result of the constant marching. ‘Hundreds killed themselves,’ recalled Lieutenant Karl von Suckow, a Mecklenburger serving with the Württemberg Guard, ‘feeling no longer able to endure such hardship. Every day one heard isolated shots ring out in the woods near the road.’40Medicine had become almost unobtainable, except with cash. The Bavarian General von Scheler reported to his king that even as early as crossing the Vistula ‘all regular food supply and orderly distribution ceased, and from there as far as Moscow not a pound of meat or bread, not a glass of brandy was taken through legal distribution or regular requisition’.41 It was an exaggeration, but a pardonable one.

There is evidence to suggest that Napoleon was being misled about both food supplies and the number of healthy soldiers in his army. Units that Napoleon was told had food for ten days had actually run out of it altogether, and General Dumas recalled that Davout’s brother-in-law, General Louis Friant, the commander of two Guard grenadier demi-brigades, ‘wanted me to produce a report on the 33rd Line to say it amounted to 3,200 men, whilst I knew that in reality no more than 2,500 men, at most, were left. Friant, who was under Murat’s orders, said Napoleon would be angry with his chief. He preferred to introduce an error, and Colonel Pouchelon provided the mendacious report required.’42 That single deception, therefore, involved three senior officers (and possibly Murat too), or at least required them to be compliant. Somehow the culture of the army had changed, so that Napoleon, who used to be so close to his men, was now regularly lied to by his senior commanders. He continued his personal inspections, but the sheer size of the Grande Armée and the breadth of its advance meant that he relied far more on his commanders than in any previous campaign. Another of his bodyguards also recalled in his memoirs that during the retreat in December Napoleon asked Bessières about the condition of the Guard. ‘Very comfortable, Sire,’ came the reply. ‘The spit is turning at a number of fires; there are chicken and legs of mutton, etc.’ The bodyguard stated: ‘If the marshal had looked with both eyes he would have found that these poor devils had little to eat. Most of them had heavy colds, all were very weary, and their number had greatly decreased.’43

• • •

When on July 19 Napoleon heard from Murat’s aide-de-camp Major Marie-Joseph Rossetti that the Russians had abandoned Drissa, ‘he could not contain himself for joy’.44 Writing to Maret from Gloubokoïé, he said: ‘The enemy has evacuated its fortified camp at Drissa and burnt all its bridges and a huge quantity of stores, sacrificing work and provisions that were the focus of their work over many months.’45* According to Rossetti’s journal, the Emperor, ‘striding quickly up and down’, said to Berthier: ‘You see, the Russians don’t know how to make either war or peace. They are a degenerate nation. They give up their palladium without firing a shot! Come along, one more real effort on our part and my brother [that is, the Tsar] will repent of having taken the advice of my enemies.’46 He quizzed Rossetti closely about the morale of the cavalry and the condition of the horses, getting favourable responses and making Rossetti a colonel on the spot. Yet in fact Murat was asking far too much of the cavalry, wrecking the horses’ constitutions with the constant work he demanded from them. ‘Always at the forefront of the skirmishers,’ Caulaincourt complained, ‘he succeeded in ruining the cavalry, ending by causing the loss of the army, and brought France and the Emperor to the brink of an abyss.’47

On July 23 Barclay arrived at Vitebsk, 200 miles east of Vilnius, ready to make a stand if Bagration joined him. But that same day, in the first major engagement of the campaign, Davout blocked Bagration’s drive northward at the battle of Saltanovka (also called Mogilev), albeit at a loss of 4,100 killed, wounded and missing. Bagration was forced to head towards Smolensk instead. Two days later, Murat’s advance guard skirmished with Barclay’s rearguard under Count Ostermann-Tolstoy at Ostrovno, west of Vitebsk. Napoleon hoped that a major battle might be joined. As ever, he wildly exaggerated the facts in his bulletin (his tenth), claiming that Murat had fought against ‘15,000 cavalry and 60,000 infantry’ (in fact the Russians had totalled 14,000) and that they had suffered 7,000 killed, wounded and captured against the true total of 2,500. He put the French losses as 200 killed, 900 wounded and 50 captured, whereas the best modern estimates are 3,000 killed and wounded and 300 captured.48

Napoleon had high hopes that the Russians might fight rather than surrender the city of Vitebsk, writing to Eugène on the 26th: ‘If the enemy wants to fight, then that’s very fortunate for us.’49 That same day, Jomini’s question about the possibility of marching on Moscow seems to have entered his strategic thinking as a serious possibility for the first time. On July 22 he had told General Reynier that the enemy would not dare attack Warsaw ‘at a time when Petersburg and Moscow are menaced so closely’. Four days later he wrote to Maret: ‘I am inclined to think that the regular divisions will want to take Moscow.’50 His plans to stop at Vitebsk or Smolensk if the enemy didn’t give battle were now morphing into something altogether grander and more ambitious. He was allowing himself to be drawn into Barclay de Tolly’s trap.

• • •

At dawn on July 28, Murat sent word that the Russians had disappeared from Vitebsk and that he was in pursuit. They had taken everything with them, leaving nothing that gave any indication of which direction they had gone in. ‘There appeared more order in their defeat than in our victory!’ noted Ségur.51 At a meeting with Murat, Eugène and Berthier, Napoleon had to face the fact that the decisive victory they so wanted ‘had just escaped our grasp, as it had at Vilnius’.52 Victory seemed tantalizingly close, and always just over the next hill or on the other side of the next lake, plain or forest – as, of course, the Russians intended. During the sixteen days he spent in Vitebsk, Napoleon very seriously considered ending the year’s campaigning there, to resume in 1813. He was now on the borders of Old Russia, where the Dvina and Dnieper rivers formed a natural defensive line. He could establish ammunition magazines and hospitals, reorganize Lithuania politically – the Lithuanians had already raised five infantry and four cavalry regiments for him – and build up the numbers for his central force, one-third of whom had by then died or were sick from typhus and dysentery. From Vitebsk he could threaten St Petersburg if need be.53 Murat’s chief-of-staff, General Auguste Belliard, told Napoleon frankly that the cavalry was exhausted and ‘stood in absolute need of rest’ since it could no longer gallop when the charge was sounded. Furthermore, there weren’t enough horseshoe-nails, smiths or even metal suitable for making nails. ‘Here I stop!’ Ségur recalled Napoleon saying on entering Vitebsk on the 28th. ‘Here I must look around me; rally, refresh my army and reorganise Poland. The campaign of 1812 is finished; that of 1813 will do the rest.’54

Napoleon certainly had a fine line of defence at Vitebsk; his left flank was fixed at Riga on the Baltic, and ran through Dünaborg, Polotsk, fortified Vitebsk with its wooded heights at the centre, then down the Berezina and through the impassable Pripet Marshes, with the fortress town of Bobruisk on his right, 400 miles south-east of Riga. Courland could support Macdonald’s corps for food and supplies, Samogitia would do the same for Oudinot’s, the Klubokoë plains for Napoleon himself, and Schwarzenberg could stop in the fertile southern provinces. There were huge supply depots at Vilnius, Kovno, Danzig and Minsk to see the army through the winter. That he truly considered this option is evident from the fact that he ordered twenty-nine large ovens to be built at Vitebsk, capable of baking 29,000 pounds of bread, and had houses pulled down to improve the appearance of the palace square where he stayed. Yet it was hard thinking of winter quartering when, as Napoleon wrote to Marie Louise, ‘We are having unbearable heat, 27 degrees. This is as hot as in the Midi.’55 Ségur blamed Murat for persuading Napoleon to push on, despite the Emperor supposedly saying, ‘1813 will see us in Moscow, 1814 at Petersburg. The Russian war is a war of three years.’56

Napoleon chose to continue chasing Barclay for several perfectly rational military reasons. He had advanced 190 miles in a month and suffered fewer than 10,000 battle casualties; July was absurdly early in the campaigning calendar to order a halt for the year; audacity had always served him well up till then and he would cede the initiative if he stopped at Vitebsk so early in the year; the Tsar had called up the 80,000-strong militia in Moscow on July 24 as well as 400,000 serfs, so it made sense to attack before they were trained and deployed; and the only two occasions when he had ever been forced to fight defensively, at Marengo and Aspern-Essling, he had not initially fared well. Murat also pointed out that Russian morale must have been devastated by the constant retreats. How much more of Russia could the Tsar see ravaged before he sued for peace? He couldn’t know that Alexander had declared in St Petersburg that he would never make peace, saying: ‘I would sooner let my beard grow to my waist and eat potatoes in Siberia.’57

The French learned that Barclay’s army was only 85 miles away at Smolensk, where it was joined by Bagration’s on August 1. Napoleon assumed that the Russians would not surrender one of the greatest cities of Old Russia without a major battle. He therefore decided not to stop in Vitebsk after all, but kept the option open of returning there after fighting the Russians at Smolensk. He was advised by Duroc, Caulaincourt, Daru and Narbonne to remain at Vitebsk, and he also heard similar views from Poniatowski, Berthier and Lefebvre-Desnouettes, with Murat putting the opposing opinion, before deciding on his own course.58 Ségur recalled that the Emperor would occasionally address people with such half-sentences as ‘Well! What shall we do? Shall we stay where we are, or advance?’, but ‘He did not wait for their reply but still kept wandering about, as if he were looking for something or someone to end his indecision.’59 Clues to his thinking can be gleaned from phrases such as that of August 7 to Marie Louise: ‘Here we are only one hundred leagues from Moscow.’60 (In fact Vitebsk is 124 leagues – 322 miles – away.)

The decision to press on to Smolensk was not taken lightly. ‘Did they take him for a madman?’ Ségur recorded Napoleon saying to Daru and Berthier around the 11th.

Did they imagine he made war from inclination? Had they not heard him say that the wars of Spain and Russia were two ulcers which ate into the vitals of France and that she could not bear them both at once? He was anxious for peace but in order to treat for it, two persons were necessary and he was only one.61

Napoleon also pointed out that the Russians would be able to march over frozen rivers in the winter, and at Smolensk he could win either a great fortress or a decisive battle. ‘Blood has not yet been spilled, and Russia is too powerful to yield without fighting. Alexander can only negotiate after a great battle,’ he said.62 This conversation lasted a full eight hours and during it Berthier burst into tears, telling Napoleon that the Continental System and the restoration of Poland weren’t good enough reasons for over-extending French lines of communication. Duroc’s friendship with Napoleon was almost ended by the decision.

Napoleon stuck nevertheless to his conviction ‘that boldness was the only prudential course’.63 He reasoned that the Austrians and Prussians might rethink their alliances with him if he stagnated, that the only way to shorten the lines of communication was to secure a quick victory and return, and that ‘a stationary and prolonged defence isn’t in the French nature’. He also feared that British military aid to Russia was about to start taking effect. He concluded, as recorded by Fain, ‘Why stop here for eight months when twenty days might suffice for us to reach our goal? . . . We have to strike promptly, otherwise everything will be compromised . . . In war, chance is half of everything. If we were always waiting for a favourable gathering of circumstances, we’d never finish anything. In summary, my campaign plan is a battle, and all my politics is success.’64*

On August 11 Napoleon gave orders to move on Smolensk, leaving Vitebsk himself at 2 a.m. on the 13th. ‘His Majesty rides much less quickly these days,’ noted Castellane, who was deputed to accompany him,

he has put on a good deal of weight, and rides a horse with more difficulty than before. The grand equerry [Caulaincourt] has to give him a hand in mounting. When the Emperor travels, he goes most of the journey by carriage. It is very tiring for the officers who have to follow, because His Majesty is rested by the time he has to mount . . . When His Majesty is on the move, one cannot expect a moment’s rest in twenty-four hours. When [General Jean-Baptiste] Éblé spoke to the Emperor about the lack of horses, His Majesty replied: ‘We shall find some fine carriage horses in Moscow.’65

When Napoleon was moving at top speed, water had to be poured on the wheels of his carriage to prevent them overheating.

• • •

The situation on both Napoleon’s flanks looked promising in mid-August, with Macdonald protecting his north successfully, Schwarzenberg in the south dealing a serious blow to Tormasov’s Third Army of the West at Gorodeczna on the 12th (for which Napoleon asked Francis to promote him to field marshal), and Oudinot and Saint-Cyr holding off General Peter Wittgenstein’s Army of Finland at Polotsk four days later. Napoleon was therefore able to launch the ‘Smolensk Manoeuvre’, a huge operation intended to pin the Russian army north of the Dnieper while swiftly moving most of the Grande Armée to the south bank, thanks to impressive bridge-building from Éblé’s engineers. Yet this rush for Smolensk was frustrated by the heroic sacrificial rearguard action of General Neverovski’s 27th Division at Krasnoi on the 14th, a fighting withdrawal that bought time for the First and Second Armies to reach Smolensk and defend it.

At 6 a.m. on the 16th Murat’s cavalry drove in the Russian outposts on the approaches to Smolensk. ‘At last I have them!’ Napoleon said, as he and Berthier reconnoitred the position at 1 p.m., coming to within 200 yards – some sources say closer – of the city walls.66 At the battle of Smolensk on August 17, Napoleon hoped to turn the Russians’ left flank, cut them off from Moscow and drive them back to the Lower Dvina. But a stout defence of the city, protected by its strong wall and deep ravines, gave Barclay the opportunity to retreat eastwards after suffering losses of around 6,000, while Ney’s and Poniatowski’s corps lost over 8,500. Under Lobau’s shelling Smolensk caught fire, which Napoleon watched with his staff from his headquarters. Ségur states that ‘The Emperor contemplated in silence this awful spectacle’, but Caulaincourt recalled Napoleon saying, ‘Isn’t that a fine sight, my Master of Horse?’ ‘Horrible, Sire!’ ‘Bah!’ Napoleon replied. ‘Gentlemen, remember the words of a Roman emperor: a dead enemy always smells sweet!’67*

French troops entered the smouldering city at dawn on August 18, stepping over rubble and corpses to find it deserted. When he heard that the Russians sang a Te Deum in St Petersburg to celebrate their supposed victory, Napoleon said wryly: ‘They lie to God as well as to men.’68 He inspected the battlefield and Ségur said ‘The pain felt by the Emperor might be judged by the contraction of his features and his irritation.’ At the gates of the citadel near the Dnieper he held a very rare council of war, with Murat, Berthier, Ney, Davout, Caulaincourt (and possibly also Mortier, Duroc and Lobau), who were seated on some mats that had been found. ‘The scoundrels!’ he said. ‘Fancy abandoning such a position! Come on, we must march on Moscow.’69 This led to ‘a lively discussion’ which lasted over an hour. Rossetti, Murat’s aide-de-camp, heard that everyone but Davout had been in favour of stopping at Smolensk, ‘but that Davout, with his usual tenacity, had maintained that it was only at Moscow that we could sign a peace treaty’.70 This was also thought to be Murat’s view, and it was certainly a line that Napoleon was to repeat often thereafter. Years later he would admit ‘I should have put my soldiers into barracks at Smolensk for the winter.’

Napoleon’s hopes for a close pursuit of the Russians were dashed the very next day when they successfully withdrew yet again after dealing Ney a heavy blow at the battle of Valutina-Gora (also known as Lubino), where the talented divisional commander General Gudin was killed when a cannonball skimmed along the ground and broke both his legs. After the battle medical shortages were so bad that surgeons tore up their own shirts to dress wounds, and then used hay and afterwards paper taken from documents in Smolensk’s archives. Yet those wounded in this part of the campaign were the lucky ones; statistically they had a far better survival rate than the healthy men who marched on eastwards.

• • •

Ney’s hopes to pincer the Russians at Valutina had been wrecked by Junot’s failure to advance his troops in time, to Napoleon’s understandable fury. ‘Junot has lost for ever his marshal’s baton,’ he said, after which he gave the command of the Westphalians to Rapp. ‘This affair will, perhaps, hinder me from going to Moscow.’ When Rapp said the army didn’t know that Moscow was now the ultimate destination, Napoleon replied: ‘The glass is full; I must drink it off.’71 Junot, who hadn’t won a victory since the Acre campaign and should have been disgraced after the loss of Portugal at the Convention of Cintra, but Napoleon kept him on for friendship’s sake.*

The day after Valutina, ‘well aware that it is more especially amidst such destruction that men think of immortality’, Napoleon distributed no fewer than eighty-seven decorations and promotions among Gudin’s 7th Légère and 12th, 21st and 127th Line.72Gudin’s division was surrounded by ‘the corpses of their companions and of the Russians, amidst the stumps of broken trees, on ground trampled by the feet of the combatants, furrowed with balls, strewn with the fragments of weapons, tattered uniforms, overturned carriages and scattered limbs’.73 By then disease, starvation, desertion and death in battle had brought Napoleon’s central army down to 124,000 infantry and 32,000 cavalry, with 40,000 left to protect his supply routes.74

Despite the fact that Barclay had escaped yet again, this time towards Dorogobuzh – or perhaps because of it, since the policy of withdrawal was so unpopular in the Russian army – on August 20 the Tsar replaced him as commander-in-chief with the sixty-seven-year-old Field Marshal Prince Mikhail Kutuzov, who had been defeated at Friedland. Napoleon was delighted, assuming that ‘He has been summoned to command the army on condition that he fights.’75 In fact, for the first two weeks after his appointment Kutuzov continued to fall back towards Moscow, carefully reconnoitring for the place to take his stand. He chose a village 65 miles to the west of Moscow, just south-west of the River Moskva, called Borodino. Despite his supply difficulties, Napoleon decided, on August 24, to press on after him.

He left Smolensk at 1 p.m. the next day, arriving at Dorogobuzh at 5 p.m. ‘Peace is in front of us,’ he told his staff, genuinely believing that Kutuzov couldn’t surrender the holy city of Moscow, the venerable previous capital of the Empire, without a major battle, and that afterwards the Tsar would have to sue for peace.76 Napoleon marched on Moscow to force the Russians to give battle, and his mind was already turning to the terms of surrender he could impose. He told Decrès that under any peace terms that were concluded he would try to secure trees in the Dorogobuzh area for ships’ masts.77 Murat’s aide-de-camp Charles de Flahaut wrote from Vyazma to his mother of his own certainty of ‘a victory which will finish the war’. While soldiers are not on oath when writing to their mothers from the front line, his assumption that the Tsar ‘will certainly now ask for peace’ was widespread in the high command.78

‘The heat was excessive; I never experienced worse in Spain,’ wrote Captain Girod de l’Ain, General Joseph Dessaix’s aide-de-camp after it hadn’t rained for a month. ‘This heat and dust make us extremely thirsty and water was scarce . . . I saw men lying on their bellies to drink horses’ urine in the gutter!’79 He also noticed that Napoleon’s orders were being disobeyed for the first time. Having ordered that private carriages, which he saw as an unnecessary luxury, should be burned, the Emperor ‘had barely gone a hundred yards before people hastened to put out the flames and the carriage joined the column, bowling along as before’.

On August 26 Napoleon wrote to Maret to say that he had heard that ‘the enemy is resolved to wait for us in Vyazma. We will be there in a few days, and then we will be halfway between Smolensk and Moscow, and, I believe, forty leagues from Moscow. If the enemy is beaten there, and nothing can secure this great capital, then I will be there on the 5th of September.’80 Yet the Russians weren’t in Vyazma either. The Grande Armée entered the city on the 29th, and found it empty of its 15,000 inhabitants. When told that a local priest had died of shock at his approach, Napoleon had him buried with full military honours. The priest may have been overcome by the official declaration by the Holy Synod of the Russian Orthodox Church that Napoleon was in fact the Anti-Christ from the Book of Revelation.81

• • •

On September 2 Napoleon received Marmont’s report of his defeat at the hands of Wellington at the battle of Salamanca on July 22. ‘It’s impossible to read anything more unimpressive,’ Napoleon told Clarke; ‘there’s more noise and clatter in it than in a clock, and not a word to explain the real state of affairs.’ He could read between the lines well enough to work out, however, that Marmont had left the well-protected Salamanca and given Wellington battle without waiting for Joseph’s reinforcements. ‘At the proper time you must let Marshal Marmont know how indignant I am with his inexplicable conduct,’ the Emperor told his war minister.82 Napoleon could nevertheless later take solace from the fact that Wellington had been forced out of Madrid by converging French forces in October and made to retreat back to Portugal. Joseph was back in his palace by November 2.

• • •

The food shortages brought with them other dangers besides those simply of hunger. When men went foraging too far from the main body of the army, they were sometimes captured by Russian irregulars, commanded by regular officers, operating well away from the main roads. This happened to Ségur’s brother Octave. By September 3 Napoleon told Berthier that Ney was ‘losing more men than if we gave battle’ because of the practice of sending out small foraging parties, and that ‘the number of prisoners being taken by the enemy is increasing by several hundred every day’. This needed to stop, through better co-ordination and protection.83 Napoleon was indignant about the incompetence and negligence he saw everywhere, especially in the treatment of the sick and wounded. ‘In the twenty years that I have commanded French armies,’ he wrote to Lacuée that day,

I’ve never seen military administration to be so useless . . . the people who’ve been sent here have neither capability nor knowledge. The inexperience of the surgeons is doing worse harm to the army than enemy batteries. The four organizing officers accompanying the Quartermaster-General have no experience. The health committee is extremely culpable to have sent such ignorant surgeons . . . The organization of nursing companies has, like all the war operations administration, entirely failed. Once we give them guns and military uniforms, they no longer want to serve in the hospitals.84

The simple fact that Napoleon had missed was also the most obvious one: its vast size made Russia impossible to invade much beyond Vilnius in a single campaign. His military administration was incapable of dealing with the enormous strain that he was putting on it. Each day, in his desperation for a decisive battle, he had fallen further into Barclay’s trap.

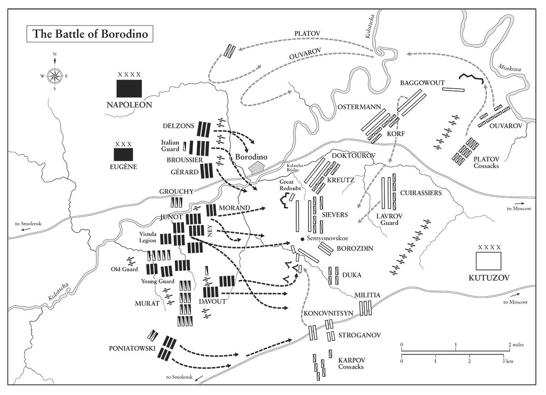

On September 5 Napoleon took the Shevardino Redoubt on the south-western edge of the Borodino battlefield, too distant from the main Russian position to be properly defended. Some 6,000 Russians were killed, wounded or captured to 4,000 Frenchmen. He then braced his army for the clash that he had been longing for ever since crossing the Niemen ten weeks earlier. In the intervening time 110,000 men had fallen victim to typhus, though not all had died, and many others had been picked off or fallen away.85 The army Napoleon could deploy for the great battle was therefore down to 103,000 men and 587 guns, against Kutuzov’s 120,800 men and 640 guns. The Russians had used the previous three days to dig formidable redoubts and arrowhead-shaped defensive earthworks called flèches, deepen ravines and clear artillery fields of fire on the battlefield. Several of the redoubts and flèches, rebuilt to their 1812 dimensions, can be seen there today.

The day before the battle, Baron de Bausset arrived at headquarters with François Gérard’s portrait of the King of Rome strapped to the roof of his carriage. Napoleon received the painting, wrote Fain, ‘with an emotion that he could hardly contain’, and set it up on a chair outside his tent so that his men could admire their future Emperor.86 ‘Gentlemen,’ he told officers arriving for a briefing, ‘if my son were fifteen, believe me he would be here in place of that painting.’87 The next day he said, ‘Take it away; keep it safe; he’s too young to see a battlefield.’ (He was indeed only eighteen months old. The painting was lost in the retreat, but Gérard had made copies.)

Bausset found Napoleon ‘quite well . . . not in the slightest degree inconvenienced by the fatigues of so rapid and complicated an invasion’, which contradicts those historians who have variously diagnosed the Emperor with cystitis, fever, influenza, an irregular pulse, difficulty in breathing, a bad cold and inflammation of the bladder that day.88 He told Marie Louise that he was ‘very tired’ the day before the battle but the day after it (as in so many of his letters) he pronounced his health to be ‘very good’. On the day of the battle itself he rose at 3 a.m. after a broken night’s sleep, and stayed up until past 9 p.m. Count Soltyk attested to his having a bad cold during the battle, but Ségur wrote of Napoleon being afflicted by ‘a burning fever and above all by a fatal return of that painful malady which every violent movement and high emotion excited in him’. (This might have been a reference to a return of the haemorrhoids which had been cured with leeches more than five years before.89) During the battle he stayed fairly sedentary at the Shevardino Redoubt and Lejeune afterwards recalled, ‘Every time I returned from one of my numerous missions, I found him sitting there in the same position, following all the moves through his pocket telescope, and issuing his orders with imperturbable calm.’90

Reconnoitring the edge of the battlefield the day before, Napoleon, Berthier, Eugène and some other staff officers had been forced to withdraw after being fired upon by grapeshot and threatened by Cossack cavalry.91 The Emperor could see how strongly the Russians were posted, yet when he sent out a series of officers to observe the defences they failed to spot the Great Redoubt in the centre of the battlefield which the Moscow militia had built for eighteen guns (a number soon increased to twenty-four). They also missed the fact that the Great Redoubt and the two flèches in the centre of the battlefield were on two entirely separate pieces of high ground, and that there was a third flèche hidden out of sight.

‘Soldiers,’ read the proclamation written the night before Borodino,

here is the battle which you have so long desired! Henceforth the victory depends upon you; it is necessary for us. It will give you abundance, good winter quarters, and a speedy return to our homeland! Behave as you did at Austerlitz, at Friedland, at Vitebsk, at Smolensk, and the remotest posterity will quote with pride your conduct on this day. Let it say of you: ‘He was at the great battle under the walls of Moscow.’92

• • •

The battle of Borodino – the bloodiest single day in the history of warfare until the first battle of the Marne over a century later – was fought on Monday, September 7, 1812.* ‘The emperor slept very little,’ recalled Rapp, who kept waking him up with reports from the advance posts that made it clear that the Russians hadn’t escaped in the night yet again. The Emperor drank some punch when he rose at 3.a.m., telling Rapp: ‘Fortune is a liberal mistress; I have often said so, and now begin to experience it.’93 He added that the army knew it could only find provisions in Moscow. ‘This poor army is much reduced,’ he said, ‘but what remains of it is good; my Guard besides is untouched.’94 He later parted his tent curtains, walked past the two guards outside and said, ‘It’s a little cold but here comes a nice sun; it’s the sun of Austerlitz.’95

At 6 a.m. a battery of one hundred French guns opened fire on the Russian centre. Davout launched his attack at 6.30, committing 22,000 superb infantry in three divisions under generals Louis Friant, Jean Compans and Joseph Dessaix deployed in brigade columns, with seventy guns in close support. Ney’s three divisions of 10,000 men followed them in, and 7,500 Westphalians were in reserve. This truly savage fight took all morning, during which Davout had a horse shot from under him and was himself wounded. The Russian soldiers showed their customary reluctance to cede ground in battle. By the end some 40,000 French infantry and 11,000 cavalry had to be committed to the struggle to take the flèches. Only when two of them had been captured by close-quarter bayonet fighting did the French discover the third, which then started pouring fire into the unprotected rear of the other two; that too had to be captured at great expense. The flèches were taken and retaken seven times – just the kind of attritional combat at which the Russians excelled and Napoleon, so far from home, needed to avoid.

By 7.30 a.m. Eugène had captured the village of Borodino by bayonet charge, but then he went too far, crossing the bridge over the Kalatscha river and charging on towards Gorki. His men were mauled as they retreated to Borodino, which they nonetheless managed to retain for the rest of the battle. At 10 a.m. Poniatowski took the village of Utitsa, and the Great Redoubt was captured by an infantry brigade under General Morand, but as it wasn’t properly supported he was soon ejected with heavy losses. Also at 10 a.m., with the Bagration flèches finally in French hands, Bagration himself was mortally wounded in a counter-attack when his left leg was smashed by a shell splinter. When the 120-house village of Semyonovskoe was captured by Davout in the late morning, Napoleon was able to move up artillery to fire into the Russian left flank. Noon saw the crisis of the battle as several marshals – there were seven present, and two future ones – begged Napoleon to unleash the Imperial Guard to smash through the Russian line while it was still extended. Rapp, who was wounded four times in the battle, also implored Napoleon to do this.

Napoleon refused – there was a limit even to his audacity 1,800 miles from Paris without any other reserves – and so the opportunity, if such it was, was lost. Ségur recalled General Belliard being sent by Ney, Davout and Murat to ask for the Young Guard to be committed against the half-opened flank of the Russian left when Napoleon ‘hesitated and ordered the general to go and look again’.96 Bessières arrived at this point and said that the Russians were merely falling back in good order to a second position. Belliard was told by Napoleon that before he would commit his reserves he wanted ‘to see more clearly upon his chessboard’, a metaphor he used several times.

Ségur thought there might have been a political motive behind the decision: due to the polyglot nature of ‘an army of foreigners who had no other bond of union except victory’, Napoleon ‘had judged it indispensable to preserve a select and devoted body’.97 He couldn’t commit the Guard with the Russian General Platov threatening his left flank and rear; and if he had sent them down the Old Post Road on the southern flank of the battlefield at noon, when Poniatowski had not captured one side of the road, it might have been severely damaged by the Russian artillery. Later in the battle, when Daru, Dumas and Berthier again urged him to commit the Guard, Napoleon replied: ‘And if there should be another battle tomorrow, with what is my army to fight?’ For all the wording of his pre-battle proclamation, he was still 65 miles from Moscow. Ordering the Young Guard to take their position on the battlefield that morning, Napoleon had been keen to emphasize to Mortier that he must not act without direct orders: ‘Do what I ask and nothing more.’98

Kutuzov lost little time in tightening his line, and the cannon in the Great Redoubt continued, in the words of Armand de Caulaincourt, to ‘belch forth a veritable hell’ against the French centre, holding up any other major advance elsewhere.99 At 3 p.m. Eugène attacked the Redoubt with three infantry columns, and a cavalry charge managed to get into it from its rear, though at the cost of the lives of both Montbrun and Auguste de Caulaincourt, the grand equerry’s brother. ‘You have heard the news,’ Napoleon said to Caulaincourt when Auguste’s death was reported at headquarters, ‘do you wish to retire?’100 Caulaincourt made no reply. He merely raised his hat in acknowledgement, with only the tears in his eyes signifying that he had heard it.101

• • •

By 4 p.m. the Grande Armée had taken the field of battle. When Eugène, Murat and Ney repeated their request to release the Guard, this time its cavalry, Napoleon again refused.102 ‘I do not wish to see it destroyed,’ he told Rapp. ‘I am sure to gain the battle without it taking a part.’103 By 5 p.m. Murat was still arguing for the Guard’s deployment but Bessières was now against it, pointing out that ‘Europe was between him and France’. At this point Berthier also changed his mind, adding that by then it was too late anyhow.104 Having withdrawn half a mile by 5 p.m., the Russians stopped and prepared to defend their positions, which an exhausted Grande Armée was ready to shell but unwilling to attack. Napoleon ordered the commander of the Guard artillery, General Jean Sorbier, to fire at the new Russian positions, saying: ‘Since they want it, let them have it!’105

Under the cover of darkness, Kutuzov withdrew that night, having lost an immense number of casualties – probably around 43,000, though so dogged was the Russian resistance that only 1,000 men and 20 guns were captured.106 (‘I made several thousand prisoners and captured 60 guns,’ Napoleon nonetheless told Marie Louise.107) The combined losses are the equivalent of a fully laden jumbo jet crashing into an area of 6 square miles every five minutes for the whole ten hours of the battle, killing or wounding everyone on board. Kutuzov promptly wrote to the Tsar claiming a glorious victory, and another Te Deum was sung at St Petersburg. Napoleon dined with Berthier and Davout in his tent behind the Shevardino Redoubt at seven o’clock that evening. ‘I observed that, contrary to custom, he was much flushed,’ recorded Bausset, ‘his hair was disordered, and he appeared fatigued. His heart was grieved at having lost so many brave generals and soldiers.’108 He was presumably also lamenting the fact that although he had retained the battlefield, opened the road to Moscow and lost far fewer men than the Russians – 6,600 killed and 21,400 wounded – he had failed to gain the decisive victory he so badly needed, partly through the unimaginative manoeuvring of his frontal assaults and partly because of his refusal to risk his reserves. In that sense, both he and Kutuzov lost Borodino. ‘I am reproached for not getting myself killed at Waterloo,’ Napoleon later said on St Helena. ‘I think I ought rather to have died at the battle of the Moskwa.’109

Napoleon was clearly sensitive to the idea that he ought to have committed the Guard at noon. At 9 p.m. he summoned generals Dumas and Daru to his tent to inquire about care of the wounded. He then fell asleep for twenty minutes, woke suddenly and continued talking: ‘People will be surprised that I did not commit my reserves to obtain greater results,’ he said, ‘but I had to keep them for striking a decisive blow in the great battle the enemy will fight in front of Moscow. The success of the day was assured, and I had to consider the success of the campaign as a whole.’110 Soon afterwards he completely lost his voice, and had to give all further orders in writing, which his secretaries found hard to decipher. Fain recalled that Napoleon ‘piled up the pages during this mute work and banged on the table when he needed each order to be transcribed’.111

Larrey amputated two hundred limbs that day. After the battle the 2nd Light Horse Lancers of the Guard, known as the Dutch Red Lancers, spent the night in woods that had been captured by Poniatowski’s infantry, where the ground around the trees was so heavily littered with corpses that they were forced to carry scores out of the way before they could clear a space for their tents.112 ‘In order to get some water it was necessary to travel far from the field of battle,’ wrote the veteran Major Louis Joseph Vionnet of the Middle Guard in his memoirs. ‘Any water to be found on the field was so soaked with blood that even the horses refused to drink it.’113 When the next day Napoleon arrived to thank and reward the remains of the 61st Demi-Brigade for capturing the Grand Redoubt, he asked its colonel why its third battalion wasn’t on parade. ‘Sire,’ came the reply, ‘it is in the redoubt.’114