26

‘Posterity would never have seen the measure of your spirit if it had not seen it in misfortune.’

Molé to Napoleon, March 1813

‘He could sympathize with family troubles; he was indifferent to political calamities.’

Metternich on Napoleon, July 1813

‘On seeing what he created twenty days after his arrival in Paris,’ Marshal Saint-Cyr wrote in his memoirs, ‘we must agree that his brusque departure from Poland was wise.’1 Napoleon embarked upon a maelstrom of activity, recognizing that it could not be long before the Russians coalesced with the Prussians, and possibly with his father-in-law Emperor Francis of Austria too, first to expel France from Poland and Germany and then to try to overthrow him. In attempting to repair the Russian disaster Napoleon showed, in the view of Count Molé, who was shortly to be appointed minister of justice, ‘a furious activity which perhaps surpassed everything he had revealed hitherto’.2 Hortense, who hurried to the Tuileries, found her former stepfather preoccupied but resolute. ‘He seemed to me wearied, worried, but not disheartened,’ she wrote. ‘I had often seen him lose his temper about some trifle such as a door opened when it should have been shut or vice versa, a room too brightly or too dimly lighted. But in times of difficulty or misfortune he was completely master of his nerves.’ She sought to give him some comfort, saying ‘Surely, our enemies have suffered huge losses too?’ To which he replied, ‘No doubt, but that does not console me.’3

In less than seventeen weeks between returning to Paris in mid-December 1812 and setting off on campaign the following April, Napoleon incorporated the 84,000 infantry and 9,000 gunners of the National Guard into the regular army; called up 100,000 conscripts from the 1809–12 year groups and 150,000 from 1813 and 1814; formed thirty new infantry regiments consisting of dozens of new demi-brigades; ordered 150,000 muskets from arms factories; combed through the depots and garrisons for extra men; moved 16,000 marines from the navy to the army as well as veteran naval gunners to the artillery; demanded that the Empire’s 12,000 cantons each provide one man and one horse; ransacked the line army in Spain to rebuild the Imperial Guard; bought and requisitioned horses wherever they could be obtained; ordered the allies to rebuild their armies; and created Corps of Observation on the Elbe, on the Rhine and in Italy.4 The recruits called up were of course described in the Moniteur as ‘magnificent men’ but some were as young as fifteen and Molé noted at a review at the Carrousel that ‘their extreme youth and poor physique roused a deep pity among the crowds around them’.5 These young recruits were nicknamed ‘Marie Louises’, partly because the Empress had signed the orders for their conscription in Napoleon’s absence, and partly because of their innocent smooth-cheeked youth. The grognards referred to the newly recruited cavalrymen as ‘chickens mounted on colts’. Since the new French recruits had no time to train they were far less manoeuvrable in battle; one of the reasons for the unimaginative frontal assaults of the next two years was the need to keep undertrained masses moving together.

If Napoleon’s imperial rule had been tyrannical, one would have expected those parts of Europe that had endured it for the longest to be the first to rise up once he had been comprehensively humiliated, yet that was not what happened. East Prussia and Silesia, which hadn’t been occupied by the French, revolted in 1813, but the parts of Prussia that had been occupied since 1806, such as Berlin and Brandenburg, did not.6 Similarly Holland, Switzerland, Italy and much of the rest of Germany either didn’t rise against him at all or waited for their governments to declare against him, or sat passively until the Allied armies arrived. In France itself, apart from some bread riots in Brittany and minor trouble in the Vendée and Midi, no risings materialized – in 1813, 1814 or indeed 1815. Although much of France was heartily sick of war, and there was substantial local opposition to conscription, especially during harvest-time, the French did not want to oust their Emperor while he was fighting France’s enemies. Only those openly denouncing Napoleon were liable to arrest, and even this mild crackdown was carried out in a classically French eighteenth-century manner. When the royalist Charles de Rivière ‘proclaimed his hopes a little too spitefully and prematurely’, he was sent to La Force prison, but was later released when a friend won his freedom in a game of billiards against Savary.7 Some ambitious army officers even wanted the war to continue. ‘One thing disturbed us,’ wrote Captain Blaze of the Imperial Guard. ‘If, we said, Napoleon should stop short in so glorious a career, if he should unfortunately take it into his head to make peace, farewell to all our hopes. Luckily, our fears were not realized, for he cut out more work for us than we were able to perform.’8

Although they rarely draw much attention, Russian losses in 1812 were also enormous. Around 150,000 Russian soldiers had been killed and 300,000 wounded or frostbitten over the course of the campaign, and very many more civilians. Russia’s field army was down to 100,000 weary men and much of the area from Poland to Moscow had been devastated, depriving the Russian treasury of hundreds of millions of rubles in taxes, though Alexander remained utterly committed to destroying Napoleon. In early 1813 four Russian divisions crossed the Vistula and invaded Pomerania, forcing the French to evacuate Lübeck and Stralsund, though they left garrisons in Danzig, Stettin and other Prussian fortresses. On January 7 Sweden, which had hitherto been neutral under the terms of the 1812 Treaty of Åbo but was now under Bernadotte’s influence, declared war against France. Bernadotte told Napoleon that he was not acting against France but for Sweden, and that Napoleon’s seizure of Swedish Pomerania was the cause of the rupture – adding, however disingenuously, that he would always bear for his old commander the sentiments of a former comrade in arms.9 Apart from his natural inclination as a Frenchman not to shed French blood, Bernadotte recognized that doing so would mean for ever giving up his hopes, which had been stoked by Alexander, of one day becoming king of France.

• • •

‘My army has suffered losses,’ Napoleon told the Senate on December 20, ‘due to the premature rigour of the season.’10 Using Yorck’s defection to whip up patriotic indignation, he set as his target to raise 150,000 men and ordered prefects to stage meetings in support of his recruiting drive. ‘Everything is in motion here,’ he told Berthier on January 9.11 It needed to be. The Russian army advanced 250 miles between Christmas Day 1812 and January 14 when they reached Marienwerder in Prussia, despite having to recapture Königsberg and other French strongholds in the depths of a northern winter.12 Eugène had no choice but to withdraw back to Berlin.

Napoleon was surprisingly open about the depth of his setback in Russia. ‘He is the first to speak about the misfortunes and he even brings them up,’ wrote Fain.13 Yet if the Emperor was willing to acknowledge his misfortune, he did not always do so truthfully. ‘There was not an affair in which the Russians captured either a gun or an eagle; they took no other prisoners but skirmishers,’ he told Jérôme on January 18. ‘My Guard was never engaged, and did not lose a single man in action, and it could not therefore have lost any eagles as the Russians declare.’14 The Guard lost no eagles because it had burned them at Bobr, but it suffered badly at the battle of Krasnoi, as Napoleon well knew. As for the Russians not capturing a single gun, something he also told Frederick VI of Denmark, Tsar Alexander conceived a scheme to build a massive column out of the 1,131 French cannon captured in the 1812 campaign. It never came to fruition, but scores of Napoleonic cannon can still be seen in the Kremlin today.15

In an effort to minimize domestic discontent, Napoleon concluded a new Concordat with the Pope at Fontainebleau in late January. ‘Perhaps we will achieve the much desired aim of ending the differences between State and Church,’ he had written on December 29. It seemed ambitious, but within a month a wide-ranging and comprehensive document had been signed covering most areas of disagreement.16 ‘His Holiness will exercise the Pontificate in both France and Italy,’ it began, ‘the Holy See’s ambassadors abroad will have the same privileges as diplomats . . . the domains of the Holy Father which are not alienated will not be subject to tax, those alienated will be compensated up to 2 million francs of income . . . the Pope will give canonical institution to the Emperor’s archdioceses within six months’ – that is, he would recognize Napoleon’s appointments as archbishops. Napoleon was also given permission to appoint ten new bishops.17 It was a good outcome for Napoleon, which the Pope immediately regretted and tried to renege upon. ‘Would you believe,’ Napoleon told Marshal Kellermann, ‘that the Pope, after having signed this Concordat freely and of his own accord, wrote to me eight days afterwards . . . and earnestly entreated me to consider the whole affair null and void? I replied that as he was infallible he could not be mistaken, and that his conscience was too quickly alarmed.’18

On February 7 Napoleon held a great parade at the Tuileries and a meeting of the Conseil d’État afterwards to set up a regency for periods when he would be away on campaign. The Malet conspiracy had rattled him and he wanted to protect himself against any renewed effort to take advantage of his absence. He was also keen to ensure that in the event of his death his son would be accepted even in infancy as his successor. (He had come a long way since his youthful fulminations against monarchs.) Under the nineteen-clause sénatus-consulte drawn up by Cambacérès, in the event of Napoleon’s death power would reside with Marie Louise, who would be advised by a Regency Council until the King of Rome came of age. Napoleon wanted Cambacérès to be the effective ruler of France, but with Marie Louise to ‘give the Government the authority of her name’.19 The meeting to establish the regency was attended by Cambacérès, Regnier, Gaudin, Maret, Molé, Lacépède, d’Angely, Moncey, Ney, the interior minister the Comte de Montalivet and the once-again forgiven Talleyrand. Napoleon, in Molé’s words, ‘though apparently calm and confident as to the campaign he was about to open, mentioned the vicissitudes of war and the fickleness of fortune in words which gave the lie to his imperturbable expression’.20 Ordering Cambacérès only to ‘show to the Empress what it is good for her to know’, Napoleon told him not to send her the daily police reports as ‘It’s pointless to speak to her of things which could worry her or sully her mind.’21

By February 13 Napoleon had received the deeply ominous news that Austria was mobilizing a field army of at least 100,000 men. Shortly afterwards, Metternich offered to ‘mediate’ a European peace settlement – hardly the stance expected of an ally. A long talk with Molé in the billiards room of the Tuileries after dinner that evening laid bare Napoleon’s thinking on several issues. He spoke highly of Marie Louise, saying he saw something of her ancestress, Anne of Austria, in her. ‘She knows quite well that so-and-so voted for the death of Louis XVI, and also knows everyone’s birth and record,’ he said, yet she never showed bias towards the old nobility or against the regicides. He then spoke of the Jacobins who were ‘fairly numerous in Paris and particularly formidable’, but ‘As long as I am alive that scum will not move, because they found out all about me on 13th Vendémiaire and know that I’m always ready to stamp on them if I have any trouble.’22 He knew his foreign and domestic enemies would be ‘much more venturesome since the Russian disaster. I must have one more campaign and get the better of these wretched Russians: we must drive them back to their frontiers and make them give up the idea of leaving them again.’23 He went on to complain about his marshals: ‘There’s not one who can command the others and none of them knows anything but how to obey me.’24

Napoleon told Molé that he had hopes for Eugène, despite the fact that he was ‘only a mediocrity’. He complained that Murat cried ‘fat tears on the paper’ when he wrote to his children and said he had suffered from ‘despondency’ during the retreat from Moscow, whereas:

In my own case it’s taken me years to cultivate self-control to prevent my emotions from betraying themselves. Only a short time ago I was the conqueror of the world, commanding the largest and finest army of modern times. That’s all gone now! To think I kept all my composure, I might even say preserved my unvarying high spirits . . . Yet don’t think that my heart is less sensitive than those of other men. I’m a very kind man but since my earliest youth I have devoted myself to silencing that chord within me that never yields a sound now. If anyone told me when I was about to begin a battle that my mistress whom I loved to distraction was breathing her last, it would leave me cold. Yet my grief would be just as great as if I’d given way to it . . . and after the battle I should mourn my mistress if I had the time. Without all this self-control, do you think I could have done all I’ve done?25

So rigid a control of one’s emotions might seem distasteful to the modern temperament, but at the time it was considered a classical virtue. It undoubtedly helped Napoleon deal with his extraordinary reversals of fortune.

This self-control was in evidence when he spoke to the opening of the Legislative Body and Senate on February 14. A spectator recalled that he mounted the steps of the throne to cheers from the deputies, ‘though their faces betrayed infinitely more anxiety than his’.26 In his first full presentation to his deputies since his return from what he called the Russian ‘desert’, he explained the defeat by saying, ‘The excessive and premature harshness of the winter caused my army to suffer an awful calamity.’ He then announced an end to his ‘difficulties’ with the Pope, said that the Bonaparte dynasty would for ever reign in Spain and proclaimed that the French Empire had a positive trade balance of 126 million francs, ‘even with the seas closed’.27 (Three days later Montalivet published statistics that backed up everything the Emperor had claimed, as dictatorships so often do.) ‘Since the rupture which followed the treaty of Amiens, I have proposed peace [with Britain] on four occasions,’ he said, in this instance truthfully, after which he added: ‘I will never make any peace but one that is honourable and suitable to the grandeur of my empire.’28 The phrase ‘perfidious Albion’ had been employed occasionally ever since the Crusades (and had appeared in an ‘Ode on the Death of Lannes’) but it was in 1813, on Napoleon’s orders, that it came into general use.29

The 1812 campaign had been disastrous for French finances. Until 1811 the franc had maintained its value against sterling, indeed it had slightly gained on it. The 1810 budget had seen a small surplus of 9.3 million francs, and bond yields were at a manageable 6 per cent. But after the infamous 29th bulletin, bonds – reflecting the lack of confidence in Napoleon’s future – shot up from 6 per cent to 10 per cent, and the budget deficit for 1812 of 37.5 million francs could be serviced only through new taxes and new sales of state property, which fetched a fraction of earlier sell-offs because their title was so insecure. When the public sale of 370 million francs’ worth of state-owned land raised only 50 million francs, sales taxes had to be increased by 11.5 per cent and land taxes by 22.6 per cent.30 Napoleon meanwhile made some personal economies, telling his chief steward that he wanted ‘fewer cooks, fewer plates, dishes, etc. On the battlefield, tables, even mine, shall be served with soup, a boiled dish, a roast, vegetables, no pudding.’31Officers were no longer going to be able to choose between wine and beer, but would drink whatever they were given. On an interior ministry proposal to spend 10 per cent of a prefect’s salary on his funeral if he died in office, Napoleon scrawled: ‘Refused. Why look for occasions to spend more?’32 The Army of Catalonia would no longer be sent wine, brandy, oats and salted meats when there was plenty locally. ‘All the deals that are being made by General Dumas are madness,’ Napoleon wrote of the intendant-general’s plans for provisioning the Oder fortresses. ‘He apparently believes that money is nothing more than mud.’33 All state building projects had been suspended before the Russian campaign, and were never resumed. The years 1813 and 1814, when there was no sign that an end to mass mobilization and high military spending was in sight, produced still higher deficits.

• • •

Although in early January 1813 Frederick William III offered to have General Yorck court-martialled for concluding the non-aggression pact with the Russians at Tauroggen, he was merely biding time. Prussia had undergone a modernizing revolution since Tilsit, which meant that Napoleon now faced a very different enemy from the one he had crushed at Jena nearly seven years before. The country had reformed, with defeat as the spur and the Napoleonic administrative–military model as its template. Barons vom Stein and von Hardenberg and generals von Gneisenau and von Scharnhorst demanded a ‘revolution in the good sense’ which, by destroying ‘obsolete prejudices’, would revive Prussia’s ‘dormant strengths’. There had been major financial and administrative reforms, including the abolition of many internal tariffs, restrictive monopolies and practices, the hereditary bondage of the peasantry and restrictions on occupation, movement and land ownership. A free market in labour was created, taxation was harmonized, ministers were made directly responsible and the property, marriage and travel restrictions on Jews were lifted.34

In the military sphere Prussia purged the high command (out of the 183 generals en poste in 1806, only eight still remained by 1812), opened the officer corps to non-nobles, introduced competitive examination in the cadet schools, abolished flogging, and mobilized her adult male population in the Landwehr (militia) and Landsturm (reserve). By 1813 she had put more than 10 per cent of her total population into uniform, more than any other Power, and over the next two years of almost constant fighting she lost the fewest through desertion.35 With a hugely improved general staff, Prussia was able to boast fine commanders in the coming campaigns, such as generals von Bülow, von Blücher, von Tauentzien and von Boyen.36 Napoleon was forced to admit that the Prussians had come on a great deal since the early campaigns; as he rather crudely put it: ‘These animals have learnt something.’37 It was hardly a consolation that they had learned much of it from him, just as Archduke Charles’s military reforms since Austerlitz had copied many Napoleonic practices and several of Barclay de Tolly’s reforms in Russia since Friedland had also echoed them. The wholesale adoption by all European armies of the corps system by 1812, making the Allies’ armies far more flexible in manoeuvre, was a tribute to the French, but also a threat to them.

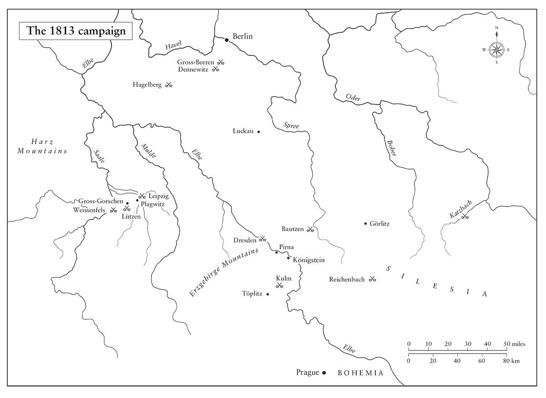

On February 28, 1813 Frederick William signed the Treaty of Kalisch with Alexander, whereby the Tsar promised to restore Prussia to her pre-Tilsit borders and provide 150,000 troops if Prussia would send 80,000 to fight Napoleon. No sooner had the treaty been signed than the British began shipping arms, equipment and uniforms into the Baltic ports for use by both armies. Eugène was forced to abandon Berlin while leaving behind garrisons in Magdeburg, Torgau and Wittenberg. Because it was already besieging the French in Stettin, Küstrin, Spandau, Glogau, Thorn and Danzig, the Russian field army was down to 46,000 infantry and 10,000 Cossacks, although they were about to be joined by 61,000 Prussians. The Allied plan was to move on Dresden in order to detach Saxony from Napoleon, while sending Cossack units pouring across the north German plain to try to stir up rebellion in the Hanseatic Towns and the Rhine Confederation.

‘At the least insult from a Prussian town or village burn it down,’ Napoleon commanded Eugène on March 3, ‘even Berlin.’38 Fortunately burning the Prussian capital was no longer possible, since the Russians entered it that same day. ‘Nothing is less military than the course you have pursued,’ Napoleon raged to Eugène on hearing the news. ‘An experienced general would have established a camp in front of Küstrin.’39 He further complained that as he wasn’t getting daily reports from Eugène’s chief-of-staff, ‘I only learn what’s happening from the English press.’ He was even angrier with Jérôme, who complained about the high taxes that Westphalians had to pay to provision fortresses like Magdeburg. ‘These means are authorized by a state of war; they have constantly been employed since the world was the world,’ Napoleon raged in a characteristically blistering response. ‘You will see how much the 300,000 men cost that I have in Spain, all the troops which I have raised this year, and the 100,000 cavalry I am equipping . . . You always argue . . . All your arguments are nonsense . . . Of what use is your intelligence since you take such a wrong view? Why gratify your vanity by vexing those who defend you?’40 Before sending off a force to defend Magdeburg on March 4, Napoleon went through a familiar checklist with its commander: ‘Make absolutely certain that each man has a pair of shoes on his feet and two pairs in his knapsack; that his pay is up to date, and, if it isn’t, have the arrears paid. Make sure that each soldier has forty cartridges in his ammunition pouch.’41

Writing to Montalivet, Napoleon said he was about to go to Bremen, Münster, Osnabrück and Hamburg, but in his new spirit of thrift his lodgings and guards of honour in those cities ‘must cost the country nothing’.42 It was a ruse, however, to deceive the enemy about his movement. It was just as well he didn’t go to Hamburg, however, as on March 18 Cossacks arrived and sparked a Hanseatic revolt just as the Allies hoped. Mecklenburg was the first state to defect from the Confederation of the Rhine. By late March the situation was so bad that Napoleon told Lauriston, now the commander of the Observation Corps of the Elbe, that he no longer dared to write to Eugène about his plans for the defence of Magdeburg and Spandau as he didn’t have a cipher code and ‘the Cossacks might intercept my letter.’43 To make things even worse, Sweden then agreed to contribute 30,000 men to the Sixth Coalition if Britain would subsidize her with £1 million, and in early April General Pierre Durutte’s small garrison was forced to evacuate Dresden.

It was at this time that Napoleon spoke to Molé about the prospect of France returning to her ‘old’, pre-war borders of 1791. ‘I owe everything to my glory,’ he said.

If I sacrifice it I cease to be. It is from my glory that I hold all my rights . . . If I brought this nation, which is so anxious for peace and tired of war, a peace on terms which would make me blush personally, it would lose all confidence in me; you would see my prestige destroyed and my ascendancy lost.44

He compared the Russian disaster to a storm which shakes a tree to its roots but ‘leaves it still more firmly fixed in the soil from which it has failed to tear it’. Dubious arboreal analogies aside, he wanted to discuss the French nation: ‘It fears me more than it likes me and would at first regard the news of my death as a relief. But, believe me, that is much better than if it had liked me without fearing me.’45 (The contrast between being loved and feared of course echoes Machiavelli’s The Prince, a book with which he was very familiar.) Napoleon went on to say that he would beat the Russians as ‘they have no infantry’ and that the borders of the Empire would be fixed on the Oder as ‘The defection of Prussia will enable me to seek compensation.’ He also thought Austria would not declare war, because ‘The best act of my political career was my marriage.’46 In those last three points at least he was clearly trying to boost Molé’s morale without any real consideration of the facts of the situation.

It was a measure of Napoleon’s resilience and resourcefulness – and of the confidence that he still commanded – that having returned from Russia with only 10,000 effectives from his central invading force, he was able within four months to field an army of 151,000 men for the Elbe campaign, with many more to come.47 He left Saint-Cloud at 4 a.m. on April 15 to take the field, with the kings of Denmark, Württemberg, Bavaria and Saxony and the grand dukes of Baden and Würzburg as allies, albeit some of them reluctant ones. ‘Write to Papa François once a week,’ he told Marie Louise three days later, ‘send him military particulars and tell him of my affection for his person.’48 With Wellington on the offensive in Spain, Murat negotiating with Austria over Naples, Bernadotte about to land with a Swedish army, fears of rebellion in western Germany and an Austria that was rearming quickly and at best only offering ‘mediation’, Napoleon knew he needed an early and decisive victory in the field. ‘I will travel to Mainz,’ he had told Jérôme in March, ‘and if the Russians advance, I will make plans accordingly; but we very much need to win before May.’49 The Allies grouping around Leipzig – commanded by Wittgenstein after Kutuzov’s death from illness in April – had massed 100,000 men; 30,000 of them were well-horsed cavalry, and they were being heavily reinforced. As a result of the equinocide in Russia the previous year, the rapidly reconstituted Grande Armée, by contrast, had only 8,540 cavalry.

Napoleon reached Erfurt on April 25 and assumed command of the army. He was shocked to find how inexperienced some of his officers were. Taking captains from the 123rd and 134th Line to make them chefs de bataillon in the 37th Légère, he complained to his war minister General Henri Clarke: ‘It’s absurd to have captains who have never fought a war . . . You take young people just out of college who have not even been to Saint-Cyr [Military Academy], with the result that they know nothing, and you put them in new regiments!’50 Yet this was the material Clarke had to work with after the loss of over half a million men in Russia.

Within three days of his arrival Napoleon had led the Grand Armée of 121,000 men back across the Elbe and into Saxony. His aim was to recover north Germany and relieve Danzig and the other besieged cities, to release 50,000 veterans, and hopefully sweep back to the line of the Vistula. Adopting the bataillon carré formation, he aimed for the enemy army at Leipzig with Lauriston’s corps in the van followed by Macdonald’s and Reynier’s corps on the left flank, Ney’s and General Henri Bertrand’s on the right and Marmont’s as the rearguard. On his left Eugène had a further 58,000 men. Poniatowski rejoined the army in May, but Napoleon sent Davout off to be governor of Hamburg, a dangerous underuse of his best marshal.

• • •

On May 1, while out reconnoitring enemy positions, Bessières was killed when a cannonball ricocheted off a wall and hit him full in the chest. ‘The death of this exalted man affected him much,’ Bausset recorded. Bessières had served in every campaign of Napoleon’s career since 1796. ‘My trust in you’, Napoleon had once written to him, ‘is as great as my appreciation of your military talents, your courage and your love of order and discipline.’51 (To calm her, he asked Cambacérès to ‘Make the Empress understand that the Duc d’Istrie [Bessières] was a long way away from me when he was killed.’52) He now wrote to Bessières’ widow saying: ‘The loss for you and your children is no doubt immense, but mine is even more so. The Duc d’Istrie died the most beautiful death and suffered not. He leaves behind a flawless reputation: this is the finest inheritance he could bestow upon his children.’53 She might justifiably have taken issue with him as to whose loss was the greater, but his letter was heartfelt nonetheless, and accompanied by a generous pension.

Napoleon now faced a force totalling 96,000 men.54 On Sunday May 2, when he was watching Lauriston’s advance, he heard that Wittgenstein had launched a surprise attack on Ney near the village of Lützen at ten o’clock that morning. Listening intently to the cannonading, he ordered Ney to hold his position while he twisted the army round, sending Bertrand to attack the enemy’s left and Macdonald its right in a textbook corps manoeuvre, with Lauriston forming the new reserve.55 ‘We have no cavalry,’ Napoleon said; ‘that’s all right. It will be an Egyptian battle; everywhere the French infantry will have to suffice, and I don’t fear abandoning myself to the innate worth of our young conscripts.’56 Many of these conscripts had received their muskets for the first time when they reached Erfurt only days before the battle, and some only the day before the battle itself.57 Yet the ‘Marie Louises’ performed well at Lützen.

At 2.30 p.m. Napoleon appeared on the battlefield at the head of the Guard cavalry, riding to the village of Kaja. He formulated his plan rapidly. Ney would continue to hold the centre while Macdonald came in on the left, Marmont secured Ney’s right, and Bonnet would try to get round the enemy’s rear from the Weissenfels–Lützen road. The Guard infantry of 14,100 would assemble out of view as a reserve and then deploy between Lützen and Kaja. Seeing some of the younger soldiers of Ney’s corps making for the rear, and even a few dropping their muskets, Napoleon formed the Guard cavalry as a stop-line, and harangued and cajoled them until they returned to their ranks. Overall, however, Ney told Napoleon that he thought the young recruits fought better than his veterans, who tended to calculate probabilities and so take fewer risks. The Moniteur subsequently stated: ‘Our young soldiers are not afraid of danger. During this great action, they have revealed the absolute nobility of French blood.’58

The four villages of Gross-Gorschen, Kaja, Rahna and Klein-Gorschen formed the centre of the battle. The Tsar – who along with Frederick William was present, although Wittgenstein as Allied commander-in-chief took all the important military decisions – sent in Russian horse artillery, and Ricard’s division was fought to a standstill as each village changed hands several times. Ney was wounded on the front line and all the senior officers of Souham’s division were either killed or wounded except Souham himself. Wittgenstein was running out of reserves and could see more and more French arriving every hour, but he chose to renew the attack on Kaja. By about 6 p.m. Napoleon decided the moment for the final assault was fast approaching. Drouot brought forward 58 guns of the Guard artillery to join the Grand Battery, so that 198 guns could now pound the enemy centre. Remembering his mistake at Borodino when he had failed to employ the Guard decisively, Napoleon ordered Mortier to lead the Young Guard – 9,800 men in four columns – into the attack, backed by six battalions of the Old Guard in four squares. Two divisions of Guard cavalry, comprising 3,335 men, were in line behind them, and to the roar of ‘Vive l’Empereur!’ they swept forward from Rahna to Gross-Gorschen. At the same moment, Bonnet’s division launched itself from Starsiedel, and Morand’s continued to attack from the west.

With all the Allied reserves totally committed, the Russian Guard massed behind Gross-Gorschen to encourage retreating Russian and Prussian formations to rally. As night fell – lit by the five burning villages – the French renewed the attack, further unsettling the enemy. After the battle the Allies withdrew in good order, having failed to exploit their huge superiority in cavalry. Napoleon was victorious, though at a heavy cost: 2,700 had been killed and as many as 16,900 wounded. The Russians and Prussians lost a similar number (though they admitted to only 11,000). Napoleon had no cavalry to conduct a pursuit, which was to be a major problem throughout the 1813 campaign. He did, however, begin the recovery of Saxony and the west bank of the Elbe. ‘My eagles are again victorious,’ he told Caulaincourt after the battle, adding ominously, ‘but my star is setting.’59

‘I’m very tired,’ Napoleon wrote to Marie Louise at eleven o’clock that night. ‘I’ve gained a complete victory over the Russian and Prussian armies under Emperor Alexander and the King of Prussia. I lost 10,000 men, killed and wounded. My troops covered themselves with glory and proved their love in a way that went to my heart. Kiss my son. I’m in very good health.’60 To her father he wrote that Marie Louise ‘continues to please me in the extreme. She is now my prime minister and acquits herself of this role to my great satisfaction; I did not want Your Majesty to be unaware of this, knowing how much it will please his paternal heart.’61 Napoleon’s appeal to Francis’s paternal pride was a clear effort to prevent him siding with his enemies. Russia and Prussia he could just about manage, but should Austria join them his chances of victory would be severely reduced.

‘Soldiers! I am satisfied with you; you have fulfilled my expectations!’ Napoleon exclaimed in his post-battle proclamation, after which he took a dig at Alexander with a mention of ‘parricidal plots’ and the Russian practice of serfdom: ‘We will drive back these Tartars into their frightful regions, which they ought never to have left. Let them remain in their frozen deserts, the abode of slavery, of barbarism, and of corruption, where man is debased to equality with the brute.’62

• • •

As the Allies retreated across the Elbe in two great columns – one mainly Prussian, one mainly Russian – the French could follow only at infantry pace. The Prussians naturally wanted to retire north to protect Berlin, while the Russians wanted to move eastwards to protect their lines of communication through Poland. Wittgenstein, still looking for opportunities to attack the French in the flank and rightly suspecting that Napoleon wanted to recapture Berlin, massed his army close to Bautzen, only 8 miles from the Austrian border, from where he could cover both Berlin and Dresden.

Napoleon entered Dresden on May 8 and stayed there for ten days. He received a Young Guard division and four battalions of the Old Guard, incorporated the Saxon army into a corps of the Grande Armée, sent Eugène back to Italy in case of Austrian encroachment, and secured three separate lines of communication back to France. ‘I have reason to be happy with Austria’s intentions,’ he told Clarke, ‘I do not suspect her provisions; however my intention is to be in a position not to have to depend on her.’63 It was a sensible policy. He was however angry with the Dresden city delegation who welcomed him, telling them that he knew they had aided the Allies during their occupation. ‘Fragments of garlands are still clinging to your houses, and your streets are still littered with the mush of the flowers your maidens strewed before the monarchs’ feet,’ he said. ‘Still, I am willing to overlook all that.’64

Napoleon then did one of those dumbfounding things of which he was so often capable. He wrote to his former intelligence chief Fouché and instructed him to come to Dresden in secret, as quickly as possible, in order to run Prussia once it was captured. ‘No one must know of this in Paris,’ he told him. ‘It must seem as if you are about to leave to go on campaign . . . Only the Empress-Regent knows of your departure. I’m very glad to have the opportunity to call upon you for new duties and to have new proof of your attachment.’65 Fouché felt no attachment to Napoleon since his abrupt sacking following his secret peace talks with Britain, as the events of the following year were to illustrate. The military situation meant that he never took over Prussia, but as with Talleyrand, Napoleon had either lost his antennae for who opposed and who supported him, or was so confident in his powers that he didn’t care. The circle of loyal advisors he could count on was shrinking.

• • •

The news that Austria was arming, and seemed ever more bellicose, worried Napoleon. He wrote to Marie Louise constantly to ask her to intercede with her father, saying on May 14 for example: ‘People are trying to mislead Papa François. Metternik [sic] is a mere intriguer.’66 He wrote to Francis himself three days later, calling him ‘Brother and dearly beloved father-in-law’. ‘No one desires peace more ardently than me,’ he began. ‘I agree to the opening of negotiations for a general peace and the summoning of a Congress’, but ‘Like all warm-blooded Frenchmen, I would rather die sword in hand than yield, if an attempt be made to force conditions on me.’67 At the same time, he sent Caulaincourt to the Tsar asking for peace, telling him: ‘My intention is to build him a golden bridge . . . you must try to tie up a direct negotiation on this basis.’ Even now he believed he could rekindle their friendship. ‘Once we have come to speak to each other,’ he said, ‘we will always finish by finding an agreement.’68 But when Caulaincourt arrived at Allied headquarters, the Tsar would see him only in the presence of the King of Prussia and the Austrian and British ambassadors.

Napoleon left Dresden at 2 p.m. on May 18 to attack the Allied main army at the fortified town of Bautzen on the River Spree. One would hardly have surmised this from the letter he wrote Marie Louise the next day: ‘The valley of Montmorency is very beautiful in this season, yet I fancy the time when it’s pleasantest is the beginning of June when the cherries are ripe.’69 That day he ordered Eugène in Italy to ‘Busy yourself with the organization of your six regiments right away. To begin with, you will dress them in jackets, trousers and shakos . . .’ In another letter he elaborated on how Eugène’s six-year-old daughter, Josephine of Leuchtenberg, would receive the revenues of the Duchy of Galliera, which Napoleon had especially created for her in the Emilia-Romagna region of Italy.70

The Allied armies, some 97,000 strong, had fallen back to the low hills overlooking Bautzen, a naturally strong position quickly improved with field fortifications. All reports indicated that they would stand their ground there, which is exactly what Napoleon wanted them to do. He had 64,000 men in Bertrand’s, Marmont’s and Macdonald’s corps facing the enemy directly, supported by Oudinot’s corps and the Imperial Guard: 90,000 in all. The Allies had built eleven strong redoubts in the hills as well as some in the town, and had three fortified villages in their second line of defence. But their northern flank was dangerously open, and that was where Napoleon intended to send Ney’s and Lauriston’s corps. In all he would engage some 167,000 men by the end of the battle. When his officers told him that some of the Prussian regiments they would be facing had fought under Frederick the Great, he made the obvious point: ‘That’s true, but Frederick isn’t around any more.’71

The battle of Bautzen opened on Thursday, May 20, 1813 with Oudinot vigorously attacking the Allied left. Napoleon waited for Ney’s enlarged wing of the Grande Armée of some 57,000 men to march up and into position before decisively turning the open Allied right flank and driving it into the Erzgebirge mountains. The plan worked well on the first day, as the Tsar mistakenly committed most of the Allied reserves to the left, just as Napoleon hoped. The next day, Napoleon was confident that Ney and Lauriston would join the battle and complete the victory. Oudinot again vigorously assaulted the Allied left; Macdonald and Marmont joined the attack in the centre and then Napoleon committed the Imperial Guard when he thought the moment right. But Ney arrived late after a confusing order led him to halt for an hour, allowing the Allies to spot the danger and march away to safety. The level of ferocity of the fighting is reflected in the casualties: 21,200 Frenchmen were killed or wounded whereas the Allies, enjoying the benefit of strong defences, lost half that. Once again the lack of cavalry meant Napoleon was unable to exploit his tactical victory in any meaningful way.

‘I had a battle today,’ Napoleon told Marie Louise. ‘I took possession of Bautzen. I dispersed the Russian and Prussian armies . . . It was a fine battle. I am rather unwell, I got soaked two or three times during the day. I kiss you and ask you to kiss my son for me. My health is good. I lost no one of any importance. I put my losses at 3,000 men, killed or wounded.’72 The proximity of the phrase ‘My health is good’ so soon after ‘I am rather unwell’ implies that the sign-off was by then just a reflex.

Only hours after writing that he hadn’t lost anyone of any importance, his closest friend, Géraud Duroc, the Duc de Frioul, was disembowelled by a cannonball in front of him on a hill overlooking Nieder-Markersdorf at the battle of Reichenbach on May 22. ‘Duroc, there is another life,’ Napoleon was represented in the Moniteur as having told him. ‘There you will await my coming.’ Duroc is supposed to have answered: ‘Yes, Sire, when you have fulfilled all the hopes of our Fatherland’, and so on, before saying: ‘Ah, Sire, leave me; the sight of me is painful to you!’73 A year later Napoleon spoke about what had really happened, admitting that ‘when his bowels were falling out before my eyes, he repeatedly cried to me to have him put out of his misery. I told him: “I feel pity for you, my friend, but there is no remedy but to suffer till the end.”’74

The loss of such a friend, who could read Napoleon’s moods and could distinguish between his real and feigned anger, was at once personally traumatic and politically devastating, especially in that spring of 1813 when Napoleon badly needed wise and disinterested counsel. ‘I was very sad all day yesterday over the death of the Duke of Frioul,’ Napoleon wrote to Marie Louise the next day. ‘He was a friend of twenty years’ standing. Never did I have any occasion to complain of him, he was never anything but a comfort to me. He is an irreparable loss, the greatest I could suffer in the Army.’75 (He remembered Duroc’s daughter in his will.) ‘The death of the Duc de Frioul pained me,’ he wrote a few weeks later to his son’s governess, Madame de Montesquiou. ‘This was the only time in twenty years that he did not guess what would please me.’76 The list of friends and close comrades Napoleon had lost in battle was by now long and doleful: Muiron at Arcole, Brueys at the Nile, Caffarelli at Acre, Desaix at Marengo, Claude Corbineau at Eylau, Lannes at Aspern-Essling, Lasalle at Wagram, Bessières the day before Lützen and now his closest friend Duroc at Reichenbach. Nor was it to end there.

• • •

The victories at Lützen and Bautzen gave Napoleon control of Saxony and most of Silesia, but his losses were high enough to force him to accept a temporary ceasefire on June 4. The Armistice of Pleischwitz was originally intended to last until July 20. ‘Two considerations have caused me to make this decision,’ Napoleon told Clarke, ‘my lack of cavalry, which prevents me from striking strong blows, and the hostile attitude of Austria.’77 It was not in Napoleon’s nature to agree to armistices, which went totally against his concept of war as a fast-moving surge of aggression in which he always kept the initiative. (Indeed the codename that the Bourbons’ intelligence service gave him was ‘The Torrent’.) He later acknowledged that the Allies used the time bought by Pleischwitz more profitably than he did, almost doubling their forces and strengthening their defences in Brandenburg and Silesia. Britain also used the time to organize the Treaty of Reichenbach, which funded Russia and Prussia with a massive £7 million, the largest subsidy of the war.78 Yet Caulaincourt, who took over Duroc’s roles as advisor and grand marshal of the palace, was in favour of the armistice, as was Berthier; only Soult thought it a mistake.

At the time Napoleon desperately needed to train, reorganize and reinforce his army, especially his cavalry, fortify the Elbe crossings, and replenish ammunition and food stocks. ‘A soldier’s health must take precedence over economic calculations or any other consideration,’ he told Daru when trying to buy 2 million pounds of rice. ‘Rice is the best way to protect oneself from diarrhoea and dysentery.’79 He worked throughout the truce at his normal frenetic pace – on June 13 he caught sunstroke having been in the saddle all afternoon. The other reason he needed time was to persuade Austria not to declare war on him. During the armistice, Metternich sent Count Stadion to the Allies and Count Bubna to Napoleon to discuss a French withdrawal from Germany, Poland and the Adriatic. Metternich had demanded an international congress at Prague to discuss peace, but Napoleon feared that was merely a pretext for Austria joining the Allies. A French evacuation of Holland, Spain and Italy was also to be tabled there.

Napoleon was outraged that he should have to give up Illyria to Austria without a fight. ‘If I can, I will wait until September to attack with heavy strikes,’ he wrote. ‘I therefore want to be in a position to beat my enemies, as far as is possible, so that when she sees me capable of doing so, Austria will . . . face up to her deceptive and ridiculous pretensions.’80 Yet he also had to acknowledge to Fain: ‘If the Allies don’t want peace in good faith, then this armistice could be very deadly to us.’81 He wasn’t always glum, however; when he was told that Marie Louise had received the homosexual Cambacérès while in bed, he told her: ‘I beg that under no circumstance will you receive, no matter who, when in bed. That is permitted only to persons over thirty years of age.’82

Some of Napoleon’s marshals wanted to retreat to the Rhine if the armistice collapsed, but he himself pointed out that this would mean abandoning for ever the garrisons in the fortresses on the Oder, Vistula and Elbe, as well as his Danish, Polish, Saxon and Westphalian allies. ‘Good God!’ he said. ‘Where’s your prudence? Ten lost battles could hardly reduce me to the position you want to place me in right away!’ When his marshals reminded him of the long lines of communication to Dresden he said: ‘Certainly, you don’t have to risk your lines of operation lightly; I know it; it’s the rule of common-sense and the ABC of the job . . . But when great interests are unravelled, there are moments in which one must sacrifice to the victory and not fear to burn one’s boats! . . . If the art of war was only the art of not risking anything, glory would be prey to mediocrities. We need a full triumph!’83

Napoleon intended to use Dresden’s geography to his advantage. ‘Dresden is the pivot from which I want to manoeuvre in order to face all the attacks,’ he told Fain.

From Berlin to Prague, the enemy is developing on a circumference of which I occupy the centre; the shortest communications get longer for him on the contours that they have to follow; and for me some marches suffice to take me wherever my presence and my reserves need to be. But in the places where I will not be, my lieutenants must know to wait for me without committing anything to chance . . . Will the Allies be able to keep up such a spread of operations for long? And myself, shouldn’t I reasonably hope to surprise them sooner or later in any false movement?84

The reasoning was sound, though it relied completely on the clarity of his own judgement and manoeuvring on internal lines.

To those in the French high command who argued that the Russians might try to put light cavalry beyond the Elbe and even the Rhine, Napoleon retorted: ‘I’m expecting it, I’ve provided for it. Independently of the strong garrisons of Mainz, Wesel, Erfurt and Würzburg, Augereau is gathering a Corps of Observation on the Main.’ ‘Only one victory,’ he added, ‘will force the Allies to make peace.’85 Napoleon’s victories early in his career had quickly led to peace by negotiation; his central mistake now was to assume that peace would still be found in that way. He now faced an enemy with as firm a resolve as his own, and a newfound determination to force him to yield. ‘You bore me continually about the necessity of peace,’ he wrote on June 13 to Savary, who had told him again how much Parisians yearned for it. ‘No one is more interested in concluding peace than me, but I will not make a dishonourable peace or one that would see us at war again in six months. Don’t reply to this; these matters do not concern you, don’t get mixed up in them.’86

On June 19 Talma, his former mistress from ten years previously Marguerite Weimer (whose stage name was Mademoiselle George) and fifteen other actors arrived in Dresden. There’s no indication that Napoleon had specifically asked for Mademoiselle George to come, but he appeared to be grateful for the distraction of theatre. ‘A remarkable change took place in Napoleon’s taste,’ remarked his chamberlain, Bausset, ‘who until this time had always preferred tragedy.’87 Now he chose only comedies to be performed and plays that drew closely observed ‘delineations of manner and characters’. Perhaps he had seen quite enough genuine tragedy by then.

• • •

The following week Napoleon wrote to Marie Louise: ‘Metternich arrived in Dresden this afternoon. We shall see what he has to say and what Papa François wants. He is still adding to his army in Bohemia; I’m strengthening mine in Italy.’88

What precisely happened during the eight-hour – some accounts say nine-and-a-half-hour – meeting in the Chinese Room of the Marcolini Palace in Dresden on June 26, 1813 is still a matter of speculation, since only Napoleon and Metternich were present and they gave contradictory accounts. Yet taking the most unreliable narrative, Metternich’s memoirs written decades later, and comparing it with the other available sources – Metternich’s own short official report to Francis of that same day, a letter Metternich wrote to his wife Eleonore two days later, Napoleon’s contemporaneous report to Caulaincourt, Maret’s report to Fain published in 1824 and some remarks Napoleon made to the Comte de Montholon six weeks before he died – it is possible to arrive at a fair understanding of what transpired in the climactic encounter that would do so much to determine the fate of Europe.89

Napoleon began the meeting shortly after 11 a.m. hoping to browbeat Metternich, the most imperturbable statesman in Europe, into dropping Austria’s plans for mediation. He thought he could persuade him to return to the French camp. Metternich, by contrast, was determined to arrive at a negotiated peace agreement covering all the outstanding territorial issues over Germany, Holland, Italy and Belgium. The vast discrepancy in their respective positions partly explains the length of the meeting. As the diplomat who had negotiated Napoleon’s marriage, in Vienna Metternich was considered pro-French. He had (at least publicly) shown dismay when the Grande Armée was shattered in Russia. Was he vague as to the precise terms of the peace, as Napoleon later charged? Or was he deliberately employing delaying tactics to allow his country to rearm? Was he demanding more than he thought Napoleon could ever give in the hope of making him look unreasonable? Or did he really want peace but thought it could be assured only on the basis of massive French withdrawals across Europe? Given Metternich’s mercurial inconsistency, he was probably driven by an ever-changing mélange of several of these motives and others. He certainly thought that Dresden was the moment when he, rather than Napoleon, could decide the fate of the continent. ‘I am making all of Europe revolve around the axis that I alone determined months ago,’ he boasted to his wife, ‘at a time when all around me thought my ideas were insignificant follies or hollow fantasies.’90

There are several contradictions in the various reports of the meeting. Napoleon admitted he threw his hat on the ground at one stage: Metternich told his wife that Napoleon threw it ‘four times . . . into the corner of the room, swearing like the Devil’.91 Fain said that Napoleon agreed to participate in the Congress of Prague at the end of the meeting; Metternich said it was four days later, as he was stepping into his carriage to leave Dresden. Metternich claimed to have warned Napoleon, ‘Sire, you are lost!’, and Napoleon accused him of being in the pay of the English.92 This last remark was a stupid one; on his deathbed Napoleon admitted it had been a disastrous faux pas, turning Metternich into ‘an irreconcilable enemy’.93 Although Napoleon tried to make amends almost immediately, pretending it had been a joke, and although the two men seem to have ended the meeting on civil terms, Metternich emerged convinced – or so he claimed – that Napoleon was incorrigibly committed to war.

‘Experience is lost on you,’ Metternich has Napoleon tell him. ‘Three times I have replaced the Emperor Francis on his throne. I have promised always to live in peace with him; I have married his daughter. At the time I said to myself you are perpetrating a folly; but it was done, and today I repent of it!’94 Napoleon digressed on the strength and strategy of the Austrian forces and boasted that he knew their dispositions down to ‘the very drummers in your army’. Going into his study, they spent over an hour going over his daily list from Narbonne’s spies, regiment by regiment, to prove how good his intelligence network was.

When Metternich brought up the ‘youthful’ nature of the French army, Napoleon is alleged to have snapped, ‘You are no soldier, and you do not know what goes on in the mind of a soldier. I was brought up in the field, and a man such as I am does not concern himself much about the lives of a million men.’95 In his memoirs Metternich wrote, ‘I do not dare to make use of the much worse expressions employed by Napoleon.’ Napoleon has been heavily criticized for this line about the million lives, which has been taken asprima facie evidence that he cared nothing for his soldiers, yet the context was critical – he was desperately trying to convince Metternich that he was perfectly willing to return to war unless he received decent peace terms. It was bluster, not the heartless cynicism it has been represented as being. If indeed he ever said it at all.

The terms Metternich demanded for peace went far beyond the restitution of Illyria to Austria. He seems to have asked Napoleon for the independence of half of Italy and the whole of Spain, a return to Prussia of almost all the lands taken from her at Tilsit, including Danzig, the return of the Pope to Rome, the revocation of Napoleon’s protectorate of the German Confederation, the evacuation of French troops from Poland and Prussia, the independence of the Hanseatic ports and the abolition of the Duchy of Warsaw. At one point Napoleon shouted from the map room adjoining his study, so loudly that the entourage heard, that he did not mind giving up Illyria but the rest of the demands were impossible.96

Napoleon had told his court several times that the French people would overthrow him if he signed a ‘dishonourable’ peace sending France back to her pre-war borders, which is effectively what Metternich was demanding. His police reports were currently indicating that the French people wanted peace far more than la Gloire, but he knew that national glory was indeed one of the vital four pillars – along with national property rights, low taxation and centralized authority – that bolstered his rule. Metternich might have been sincere in his desire for peace (though the words ‘Metternich’ and ‘sincerity’ tend to sit uncomfortably together at the best of times) but he clearly asked far too much as a price for it.

‘I had a long and wearisome talk with Metternich,’ Napoleon told Marie Louise the next day. ‘I hope peace will be negotiated in a few days’ time. I want peace, but it must be an honourable one.’97 That same day, Austria secretly signed a second Treaty of Reichenbach, with Prussia and Russia, in which she promised to go to war with France if Napoleon rejected peace terms at Prague. This, of course, had the effect of increasing the terms that Prussia and the by then irreconcilable Russia would demand.

Napoleon met Metternich again on June 30, this time for a four-hour conference at which they extended the armistice to August 10 and Napoleon accepted Austrian mediation at the Prague Congress, set to start on July 29. ‘Metternich,’ Napoleon told his wife afterwards, ‘strikes me as an intriguer and as directing Papa François very badly.’98 Although Napoleon denounced it as ‘unnatural’ for Emperor Francis to make war on his son-in-law, he himself had demanded that Charles IV of Spain make war against his son-in-law, the King of Portugal, in 1800, so he was not on very sure ground.

Napoleon’s position at the coming Congress was severely weakened when the news arrived on July 2 of Wellington’s crushing victory over Joseph and his chief-of-staff Marshal Jourdan at the battle of Vitoria in northern Spain on June 21, which cost Joseph 8,000 men and virtually the entire Spanish royal art collection. (It can today be seen at Apsley House in London. Jourdan’s red velvet marshal’s baton studded with golden bees is today on display outside the Waterloo Gallery at Windsor Castle.) Napoleon said the defeat at Vitoria was ‘because Joseph slept too long’, which is absurd.99 At the time, he wrote to Marie Louise to say that Joseph ‘is no soldier, and knows nothing about anything’, though that begs the question why he gave his brother overall command of an army of 47,300 men against the greatest British soldier since Marlborough.100 The trust and affection between the brothers had almost completely broken down over the disasters in Spain, for which each blamed the other. Five days later Napoleon told Marie Louise that if Joseph took up residence at his lovely Château de Mortefontaine in the Oise, with its islets, orangery, aviary, two parks and some of the finest landscaped gardens in Europe, then ‘it must be incognito and you must ignore him; I will not have him interfere with government or set up intrigues in Paris.’ He ordered Soult to take command of Joseph’s shattered army, with the very competent generals Honoré Reille, Bertrand Clauzel, Jean-Baptiste d’Erlon and Honoré Gazan as his principal lieutenants, hoping to protect Pamplona and San Sebastián.

On July 12 the Russian, Prussian and Swedish general staffs met at Trachenberg to co-ordinate strategy in the event that the Prague Congress should fail. It was one of those rare occasions when leaders showed they had learned the lessons of history. Appreciating that Napoleon had often outflanked enemy armies and then punished the centre, they accepted the Austrian General Joseph Radetzky’s strategy to divide their forces into three armies that would advance into Saxony, not offering battle to Napoleon himself, but instead withdrawing before him and concentrating on the inferior forces of his lieutenants. If one of the Allied armies was attacked by Napoleon, the other two would attack his flank or rear. The idea was to force Napoleon to choose between three options: going on the defensive, leaving open his lines of communication or dividing his forces.101 The Trachenberg strategy was explicitly tailored to counteract Napoleon’s military genius and it would be used to tremendous effect.

• • •

The Congress of Prague finally met on July 29. Caulaincourt and Narbonne represented France. ‘Russia is entitled to an advantageous peace,’ Napoleon told Fain at this time:

she would have bought it by the devastation of her provinces, by the loss of her capital and by two years of war. Austria, on the contrary, doesn’t deserve anything. In the current situation, I have no objection to a peace that might be glorious to Russia; but I feel a true repugnance to seeing Austria, as a price for the crime she committed by violating our alliance, collect the fruits and honours of the pacification of Europe.102

He did not wish to reward Francis and Metternich for what he saw as their scheming perfidy. After receiving intelligence reports from his spies, he warned his marshals on August 4 that ‘Nothing is happening at the Congress of Prague. They will arrive at no result, and the Allies intend to denounce the armistice on the 10th.’103

On August 7 Metternich demanded that the Grand Duchy of Warsaw be repartitioned, that Hamburg (which Davout had captured before the armistice) be liberated, that Danzig and Lübeck become free cities, that Prussia be reconstructed with a border on the Elbe and that Illyria, including Trieste, be ceded to Austria.104 Despite the fact that it would have meant forswearing the last seven years, leaving allies in the lurch and rendering the sacrifice of hundreds of thousands of lives in vain, almost every other statesman of the day would have agreed to these terms. But the Emperor of France, the heir to Caesar and Alexander, simply could not bring himself to accept what he saw as a humiliating peace.