27

‘Fear and uncertainty accelerate the fall of empires: they are a thousand times more fatal than the dangers and losses of an ill-fated war.’

Napoleon, statement in the Moniteur, December 1804

‘When two armies are in order of battle, and one has to retire over a bridge while the other has the circumference of the circle open, all the advantages are in favour of the latter.’

Napoleon’s Military Maxim No. 25

‘There’s not an ounce of doubt that the enemy will call off the armistice on the 10th and that hostilities will recommence on the 16th or 17th,’ Napoleon warned Davout from Dresden on August 8, 1813. He predicted that Austria would then send 120,000 men against him, 30,000 against Bavaria and 50,000 against Eugène in Italy.1 Nonetheless, he concluded: ‘Whatever increase in forces this gives to the Allies, I feel able to face up to them.’ His birthday celebrations were therefore brought forward five days, to August 10; they were to be the last formally held while he ruled France. The Saxon cavalry colonel Baron Ernst von Odeleben recalled in his memoirs the two-hour review of 40,000 soldiers, a Te Deum sung at Dresden cathedral accompanied by the roar of artillery salutes, the Imperial Guard banqueting with the Saxon Royal Guard under the linden trees by the Elbe, bands playing martial airs, every soldier receiving double pay and double meat rations, and the King of Saxony giving thousands of bottles of wine to the troops. As for Napoleon, ‘the vivats resounded as he passed along the ranks at a full gallop, attended by his brilliant suite.’ Few would have predicted that the French and Saxon artillerymen who ‘caroused together’ would within weeks be firing on each other. At 8 p.m. Napoleon visited the King of Saxony’s palace for a birthday banquet, after which their soldiers jointly cheered and discharged fireworks from either side of the bridge. ‘An azure sky gave a charming effect to the multitude of rockets,’ remembered Odeleben, ‘which crossed each other in their flight over the dark roofs of the city, illuminating the air far and wide . . . After a pause the cipher of Napoleon appeared in the air, above the palace.’2 Later on, as the crowds dispersed, the ‘doleful cries’ of a fisherman could be heard from the shore; he had approached too close to the rockets and had been mortally wounded. ‘Was this an omen,’ Odeleben wondered, ‘of the dreadful career of the hero of the fête?’

By mid-August 1813 Napoleon had assembled 45,000 cavalry, spread over four corps and twelve divisions.3 It was far more than he had had at the start of the armistice, but still not enough to counter the forces massing against him. The Allies denounced the armistice at noon on the 11th, within twenty-four hours of Napoleon’s estimate, and stated that hostilities would resume at midnight on the 17th.* Austria declared war on France on the 12th. The deftness with which Metternich had drawn Austria out of her alliance, then into neutrality, then into supposedly objective mediation, and then, the day after the end of the armistice, into the Sixth Coalition has been described as ‘a masterpiece of diplomacy’.4 Napoleon saw only duplicity. ‘The Congress of Prague never seriously took place,’ he told the King of Württemberg. ‘It was a means for Austria to choose to declare herself.’5 He wrote to Ney and Marmont saying he would take up a position between Görlitz and Bautzen and see what the Austrians and Russians would do. ‘It seems to me that no good will come of the current campaign unless there is first a big battle,’ he concluded in what was by now a familiar refrain.6

The strategic situation was serious but not disastrous. As he had stated, Napoleon had the advantage of internal lines within Saxony, although he was surrounded by large enemy armies on three sides. Schwarzenberg’s Army of Bohemia now consisted of 230,000 Austrians, Russians and Prussians, who were coming up from northern Bohemia; Blücher was leading the Army of Silesia, comprising 85,000 Prussians and Russians, westwards from Upper Silesia, and Bernadotte headed a Northern Army of 110,000 Prussians, Russians and Swedes moving southwards from Brandenburg: 425,000 men in total, with more on the way. Facing them, Napoleon had 351,000 men spread between Hamburg and the upper Oder.7 Although he had a further 93,000 men garrisoning German and Polish towns and 56,000 training in French army depots, they were not readily available. He would need to keep his army concentrated centrally and defeat each enemy force separately, as he had done so often in the past. Yet instead he made the serious error of splitting his army – contradicting two of his own most important military maxims: ‘Keep your forces concentrated’ and ‘Do not squander them in little packets.’8

Napoleon took 250,000 men to fight Schwarzenberg, while sending Oudinot (against the marshal’s protestations) northwards to try to capture Berlin with 66,000 men, and General Jean-Baptiste Girard to defend Magdeburg 80 miles to the west of Oudinot with 9,000 men. He also ordered Davout to leave 10,000 men behind to defend Hamburg and to support Oudinot with a further 25,000. As in the attack on Moscow, Napoleon rejected the strategy that had served him so well in the past – that of concentrating solely on the enemy’s main force and annihilating it – and instead allowed secondary political objects to intervene, such as his desire to take Berlin and punish Prussia. Nor did he place Davout under Oudinot’s command or vice versa, with the result that there was no unity of command in the northern theatre.

Even had Oudinot succeeded in capturing Berlin it would not have guaranteed victory in 1813 any more than it had in 1806; had Schwarzenberg been comprehensively defeated by the combined French forces, Bernadotte could not have defended Berlin in any case. Although Napoleon knew the campaign was going to be decided in Saxony or northern Bohemia, he failed to give Oudinot more than a skeleton force to protect the Elbe from Bernadotte and defend his rear.9 Leaving Davout to counter non-existent threats from north-west Germany was also a shocking waste of the marshal who had best proved his ability in independent command.

On August 15, his forty-fourth birthday, Napoleon left Dresden for Silesia, where he hoped to strike Blücher, who had captured Breslau. On the way he was joined at Bautzen by Murat, who was rewarded for his unexpected re-adherence to Napoleon’s cause with his old position in overall charge of the cavalry. That day Napoleon told Oudinot that Girard’s division at Magdeburg was 8,000 to 9,000 strong, which was true. The very next day he assured Macdonald it numbered 12,000.10

• • •

‘It is he who wanted war,’ Napoleon wrote to Marie Louise in reference to her father, ‘through ambition and unbounded greed. Events will decide the matter.’11 From then on he referred to Emperor Francis only as ‘ton père’ or ‘Papa François’, as when writing on August 17, ‘Deceived by Metternich, your father has sided with my enemies.’12 As regent of France and a good wife, Marie Louise was loyal to her husband and adopted country, rather than to her father and her fatherland.

Putting their Trachenberg strategy into effect as agreed, the Allies fell back in front of Napoleon’s force while seeking out those of his principal lieutenants. Blücher was thus ready to take on Ney between the Bober river and the Katzbach on August 16, but he pulled back when Napoleon moved up with large elements of his main field army. Oudinot, whose advance on Berlin was slowed by torrential rain that all but halted his artillery, was pounced upon by Bülow’s Prussians and Count Stedingk’s Swedish corps in three separate actions from August 21 to 23 at Gross-Beeren, and defeated. He withdrew to Wittenberg rather than, as Napoleon would have preferred, Luckau. ‘It’s truly difficult to have fewer brains than the Duke of Reggio,’ Napoleon said to Berthier, after which he despatched Ney to take over Oudinot’s command.13

By August 20 Napoleon was in Bohemia, hoping to impede Schwarzenberg’s movement towards Prague. ‘I drove out General Neipperg,’ he reported to Marie Louise that day. ‘The Russians and Prussians have entered Bohemia.’14 (Only a year later, the dashing one-eyed Austrian General Adam von Neipperg would exact a horribly personal revenge.) Hearing of a major attack on Dresden by the Army of Bohemia, Napoleon turned his army around on the 22nd and dashed back there, leaving Macdonald to watch Blücher. As he did so he wrote to Saint-Cyr: ‘If the enemy has effectively carried out a big movement towards Dresden, I consider this to be very happy news, and that will even force me within a few days to have a great battle, which will decide things for good.’15 The same day he also wrote to his grand chamberlain, the Comte de Montesquiou, expressing his dissatisfaction with his birthday festivities in Paris. ‘I was much displeased to learn that matters were so badly managed on the 15th of August that the Empress was detained for a considerable time listening to bad music,’ he wrote, ‘and that consequently the public were kept waiting two hours for the fireworks.’16

• • •

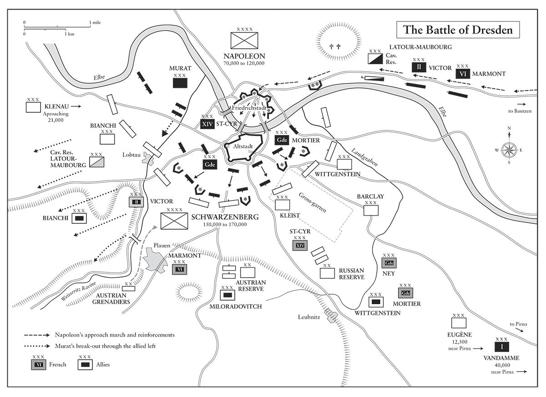

The battle of Dresden was fought on August 26–27, 1813. Napoleon’s intelligence service had accurately warned of the huge Allied forces converging on the city. By the 19th, Barclay de Tolly’s Russians had joined Schwarzenberg to form a vast army 237,770 strong – comprising 172,000 infantry, 43,500 cavalry, 7,200 Cossacks and 15,000 artillery, with a colossal 698 guns. This enlarged Army of Bohemia marched into Saxony on August 21 in five columns. Wittgenstein’s column of 28,000 men headed for Dresden. Since Napoleon controlled all the bridges over the Elbe, however, the French were able to march on both sides of the river.

At Dresden itself the Old City defences, effectively a semicircle anchored at each end on the Elbe, were held by three divisions of Saint-Cyr’s corps, roughly 19,000 infantry and 5,300 cavalry. The city’s garrison of eight battalions manned the walls. Napoleon arrived at the gallop at 10 a.m. on the 26th and approved Saint-Cyr’s deployments. Despite suffering from stomach pains that induced vomiting before the battle, he fired off his instructions. Guns were placed in each of the five large redoubts outside the Old City walls and eight inside the New City. The Old City’s streets and gates were barricaded, all trees within 600 yards of the walls were cut down and a battery of thirty guns was placed on the right bank of the river to fire into Wittgenstein’s flank.17 Fortunately for those making these preparations, the slowness of General von Klenau’s Austrian column meant that the general attack had to take place the next day.

Although Tsar Alexander, General Jean Moreau (who had left his English exile to witness the great assault on Napoleon) and General Henri de Jomini (Ney’s Swiss chief-of-staff who had defected to the Russians during the armistice) all thought Napoleon’s position too strong to attack, King Frederick William of Prussia argued that it would damage army morale not to, and insisted that the Allies gave battle. Although both sides were ready to fight from 9.30 a.m. nothing happened until mid-afternoon, when Napoleon ordered Saint-Cyr to retake a factory just outside the city walls. This minor advance was mistaken by the Allied commanders as the signal for the battle to begin, which it therefore did essentially by accident.

Wittgenstein was in action by 4 p.m., advancing under heavy artillery fire as the Young Guard met the Russian attack. Five Jäger (elite light infantry) regiments and one of hussars attacked the Gross-garten, a formal baroque garden outside the city walls, with infantry and artillery support. The French defended the Gross-garten stubbornly, and managed to bring up a battery through the Prinz Anton Gardens to hit the enemy in the flank. Two Russian attack columns were meanwhile caught by murderous artillery fire from beyond the Elbe. By the end of the day each side held about half of the Gross-garten. (A fine view of the battlefield can be seen today from the 300-foot dome of the Frauenkirche.) Marshal Ney led a charge at Redoubt No. 5 composed of Young Guard units and men of Saint-Cyr’s corps, which forced the Austrians to feed in reserves, but even these couldn’t prevent an entire Hessian battalion from being surrounded and forced to surrender. When the first day’s fighting ended at nightfall, the Allies had lost 4,000 killed and wounded, twice as many as the French.

Napoleon was reinforced by Victor’s corps during the night. They went up to Friedrichstadt as Marmont moved to the centre, and the Old Guard crossed the Elbe to form a central reserve. Using the corps system effectively, Napoleon now had massed 155,000 men for the next day’s fighting. It poured with rain all night and there was a thick fog on the morning of August 27. As it cleared, Napoleon spotted that the Allied army was divided by the deep Weisseritz ravine, which cut off its left wing under Count Ignaz Gyulai from its right and centre.18 He decided on a major attack at 7 a.m. with almost all his cavalry and two corps of infantry. Murat, wearing a gold-embroidered cloak over his shoulders and a plume in his headdress, had sixty-eight squadrons and thirty guns of the 1st Cavalry Corps ready for the attack on Gyulai’s corps, along with thirty-six battalions and sixty-eight guns of Victor’s corps.

By 10 a.m. the Austrians were under huge pressure despite the fact that Klenau had finally rejoined the Army of Bohemia. Victor’s corps and General Étienne de Bordessoulle’s heavy cavalry succeeded in turning their flank. At 11 a.m. Murat ordered a general assault, charging forward with the cry ‘Vive l’Empereur!’ Around Lobtau the Austrian infantry stood at bay, with good artillery support, streets barricaded and houses loopholed for muskets. Their skirmishers were driven back and through the patchy fog they saw the massive attack columns of Murat’s infantry advancing. Under heavy artillery fire, the French made for the gaps between the villages and got past them, before turning to attack them from the rear. Although the Austrians made counter-attacks, their line of retreat was relentlessly compromised.

In the centre, the Austrians and Prussians were ready from 4 a.m., expecting to renew the fight. Marmont’s task was to fix them in place while the French wings defeated the enemy. By 8 a.m. Saint-Cyr was attacking the Prussian 12th Brigade on the Strehlen heights, forcing them back to Leubnitz, where they were joined by the Russian 5th Division. This stubborn fighting was mainly done by bayonet as the heavy rain soaked the muskets’ firing-pans despite their protective frizzens.

By 10 a.m. Napoleon had massed a large battery on the Strehlen heights, from where it dominated the centre of the battlefield. As Saint-Cyr paused to reorganize, he was counter-attacked by Austrian infantry. He tried to push on but the sheer weight of Allied artillery fire pinned him back. Napoleon was by his side at noon and ordered him to keep up the pressure, while the Young Guard was pitched into Leubnitz to try to wrest the village from the Silesian infantry. At 1 p.m. Napoleon was opposite the Allied centre-right, in the middle of a formidable artillery exchange where he personally directed some horse artillery that largely silenced many of the Austrian guns. During this firefight Moreau had both legs smashed by a cannonball. By the early afternoon the Prussian cavalry was beginning to move away to the right. Saint-Cyr’s pressure was slowly tipping the balance.

On Napoleon’s left flank, Ney began his attack at 7.30 a.m. As the Prussians had already been driven out of the Gross-garten, he used the garden to mask part of his advance. Napoleon arrived at 11 a.m. and encouraged the enthusiastic attack of the tirailleurs (skirmishers), although they were occasionally checked by Prussian and Russian cavalry. Despite Barclay de Tolly having no fewer than sixty-five squadrons of Russian and twenty of Prussian cavalry to hand, he didn’t commit them. In the pouring rain this was a fight of bayonet and sabre, punctuated by blasts of artillery. Schwarzenberg contemplated a major counter-attack, only to find all his units already too heavily engaged, just as Napoleon had intended.

By 2 p.m. Napoleon was back in the centre forming a battery of thirty-two 12-pounders near Rachnitz to smash the Allied centre. At 5.30 p.m. Schwarzenberg received the news that Vandamme had crossed the Elbe at Pirna and was marching on his rear. He now had no alternative but to give up the fight altogether. (Vandamme was a reckless swashbuckler of whom Napoleon said that every army needed one, but that if there were two he would have to shoot one of them.19) By 6 p.m. the French had halted in the position occupied by the Allies that morning. Although both sides had lost around 10,000 men, Murat’s victory on the right flank had led to the capture of 13,000 Austrians, and the French captured 40 guns.20 When he was told that Schwarzenberg had been killed in the battle, Napoleon had exclaimed, ‘Schwarzenberg has purged the curse!’ He hoped his death would finally lift the shadow of the fire at his marriage celebrations in 1810. As he explained later: ‘I was delighted; not that I wished the death of the poor man, but because it took a weight off my heart.’21 Only later did he find out to his profound chagrin that the dead general was not Schwarzenberg but Moreau. ‘That rascal Bonaparte is always lucky,’ Moreau wrote to his wife just before he expired from his wounds on September 2. ‘Excuse my scrawl. I love and embrace you with all my heart.’22 It was brave of the renegade general to apologize for his handwriting while dying, but he was wrong about Napoleon’s extraordinary run of good luck.

• • •

‘I’ve just gained a great victory at Dresden over the Austrian, Russian and Prussian armies under the three sovereigns in person,’ Napoleon wrote to Marie Louise. ‘I am riding off in pursuit.’23 The next day he corrected himself, saying ‘Papa François had the good sense not to come along.’ He then said Alexander and Frederick William ‘fought very well and retired in all haste’. Napoleon was harder on the Austrians. ‘The troops of Papa François have never been so bad,’ he told his Austrian-born wife. ‘They put up a wretched fight everywhere. I have taken 25,000 prisoners, thirty colours and a great many guns.’24 In fact it had been the other way around; the Allied sovereigns and generals had failed their men strategically and tactically in their positioning and lack of co-ordination, and it was only the stubborn, brave troops who had saved the two-day battle from becoming a rout.

Riding over the battlefield in the driving rain worsened Napoleon’s cold, and he was struck with vomiting and diarrhoea after the battle. ‘You must go back and change,’ an old grognard called out to him from the ranks, after which the Emperor finally went back to Dresden for a hot bath.25 At 7 p.m. he told Cambacérès, ‘I am so tired and so preoccupied that I cannot write at length; [Maret] will do so for me. Things are going very well here.’26 He couldn’t afford to be ill for long. ‘In my position,’ he had written in a general note to his senior commanders only a week earlier, ‘any plan where I am not myself in the centre is inadmissible. Any plan which removes me to a distance establishes a regular war in which the superiority of the enemy cavalry, in numbers, and even in generals, would completely ruin me.’27 Here was an open recognition that his marshals couldn’t be expected to pull off the coups necessary to win battles against forces 70 per cent larger than theirs – indeed that most of them to his mind were barely capable of independent command.

This judgement was largely confirmed when on August 26 – the first day of the battle of Dresden – in Prussian Silesia on the Katzbach river (present-day Kaczawa) Marshal Macdonald, with 67,000 men of the French army and the Rhine Confederation, was crushed by Blücher’s Army of Silesia.28 On St Helena Napoleon would confirm his opinion: ‘Macdonald and others like him were good when they knew where they were and under my orders; further away it was a different matter.’29 The very next day General Girard’s corps was effectively destroyed at Hagelberg on the 27th by the Prussian Landwehr, which had only recently exchanged its pikes for muskets, and some Cossacks. Girard’s stricken and much depleted force made it back to Magdeburg only with the greatest difficulty. On August 29 General Jacques Puthod’s 17th Division of 3,000 men was trapped up against the flooded River Bober at Plagwitz, fired off all their ammunition and had to surrender en masse. They lost three eagles, one of which was found in the river after the battle.30

Hoping to hold up Schwarzenberg’s retreat into Bohemia, Napoleon ordered Vandamme to leave Peterswalde with his force of 37,000 men and to ‘penetrate into Bohemia and throw back the Prince of Württemberg’. The goal was to cut the enemy lines of communication with Tetschen, Aussig and Teplitz. But Barclay, the Prussian General Kleist and Constantine together had twice Vandamme’s numbers and although his troops fought valiantly and exacted a heavy toll he was forced to surrender on the 30th near the hamlet of Kulm with 10,000 of his men. Napoleon had sent Murat, Saint-Cyr and Marmont to attack the Austrian rearguard at Töplitz as Vandamme bravely held up its vanguard, but they couldn’t save him. Napoleon himself was ill and unable to leave his bedroom; even on the afternoon of the 29th he could only get as far as Pirna.31 When Jean-Baptiste Corbineau arrived the next day with the disastrous news Napoleon could only say: ‘That’s war: very high in the morning and very low in the evening: from triumph to failure is only one step.’32

By the end of August all the advantage Napoleon had gained from his victory at Dresden had been thrown away by his lieutenants. Yet there was more bad news to come. Having sent Ney off to resume the attack on Berlin to recover the situation after Oudinot’s defeat by Bernadotte, on September 6 Ney and Oudinot together were defeated by General von Bülow at the battle of Dennewitz in Brandenburg. Bavaria then declared her neutrality, which made other German states consider their position, especially once the Allies proclaimed the abolition of the Confederation of the Rhine at the end of the month.

Napoleon spent most of September in Dresden, occasionally dashing out to engage any Allied forces that came too close, but incapable of making any large, campaign-winning strokes because of the Allies’ determination to avoid giving him battle, while continuing to concentrate on his subordinates. These were frustrating weeks for him, and his impatience and distemper would occasionally show. When General Samuel-François l’Héritier de Chézelles’ 2,000 men of the 5th Cavalry Corps were attacked by 600 Cossacks between Dresden and Torgau, he wrote to Berthier that Chézelles’ men should have fought them more aggressively even if they ‘had neither sabres nor pistols, and were armed only with broomsticks’.33

This kind of fighting was bad for morale, and on September 27 an entire Saxon battalion deserted to Bernadotte, under whom they had fought at Wagram. In Paris Marie Louise asked for a sénatus-consulte for a levy of 280,000 conscripts, no fewer than 160,000 of them an advance on the 1815 class year, the 1814 year having already been called up. Yet there was already widespread opposition to further conscription over large areas of France.

General Thiébault, a divisional commander in the campaign, accurately summed up the situation in the autumn of 1813:

The arena of this gigantic struggle had increased in an alarming fashion. It was no longer the kind of ground of which advantage could be taken by some clever, secret, sudden manoeuvre, such as could be executed in a few hours, or at most in one or two days. Napoleon . . . could not turn the enemy’s flank as at Marengo or Jena, or even wreck an army, as at Wagram, by destroying one of its wings. Bernadotte to the north with 160,000 men, Blücher to the east with 160,000, Schwarzenberg to the south with 190,000, while presenting a threatening front, kept at such a distance as to leave no opening for one of those unforeseen and rapid movements which, deciding a campaign or a war by a single battle, had made Napoleon’s reputation. The man was annihilated by the presence of space. Again, Napoleon had never till then had more than one opposing army to deal with at one time; now he had three, and he could not attack one without exposing his flank to the others.34

By early October Allied forces were moving across the French lines of communication at will, and there were several days when Napoleon could neither send nor receive letters. The situation worsened significantly on October 6 when Bavaria declared war against France. ‘Bavaria will not march seriously against us,’ a philosophical Emperor told Fain, ‘she will lose too much with the full triumph of Austria and the disaster of France. She knows well that the one is her natural enemy, and the other is her necessary support.’35The next day Wellington crossed the Bidasoa river out of Spain, leading the first foreign army onto French soil since Admiral Hood had vacated Toulon twenty years earlier. With Blücher and 64,000 men crossing the Elbe, and the 200,000-strong Army of Bohemia marching towards Leipzig, Napoleon left Saint-Cyr in Dresden and headed northwards with 120,000 men, hoping to chase Blücher back over the Elbe and then return to fight Schwarzenberg, while all the time posing a credible threat to Berlin.

By October 10 the three Allied armies under Schwarzenberg, Blücher and Bernadotte, totalling 325,000 men, were converging upon Leipzig, hoping to trap Napoleon’s much smaller army there. ‘There will inevitably be a great battle at Leipzig,’ Napoleon wrote to Ney at 5 a.m. on October 13, the same day he discovered that the Bavarian army had joined the Austrians and were now threatening the Rhine.36 Despite being greatly outnumbered (he could muster a little over 200,000 men), Napoleon decided to fight for the city which the British journalist Frederic Shoberl described the following year as ‘undoubtedly the first commercial city of Germany, and the great Exchange of the Continent’.37 He drew his men up in ranks of two rather than three, after Dr Larrey persuaded him that many of the head wounds he was seeing weren’t self-inflicted, as Napoleon had suspected, but were the result of men reloading and discharging their muskets close to the heads of comrades kneeling in the ranks in front of them. ‘One of the advantages of this new disposition’, Napoleon said, ‘will be to cause the enemy to believe that the army is one third stronger than it is in reality.’38

On October 14, as the Imperial Guard arrived from Düben, Napoleon spent the night in the house of a M. Wester in Leipzig’s eastern suburb of Reudnitz. As usual the maréchal de logis had chalked the names of the generals who occupied each room on their doors, and a fire was immediately made up in Napoleon’s room, ‘as His Majesty was very fond of warmth’.39 The Emperor then chatted to Wester’s chief clerk.

NAPOLEON: ‘What is your master?’

CLERK: ‘He is in business, Sire.’

NAPOLEON: ‘In what line?’

CLERK: ‘He is a banker.’

NAPOLEON: (smiling) ‘Oho! Then he is worth a plum.’

CLERK: ‘Begging your Majesty’s pardon, indeed he is not.’

NAPOLEON: ‘Well then, perhaps he may be worth two?’

They discussed discount bills, interest rates, the clerk’s wages, the present (woeful) state of business, and the owner’s family. ‘During the whole conversation the Emperor was in very good humour, smiled frequently, and took a great deal of snuff,’ recalled Colonel von Odeleben.40 When he left, he paid 200 francs for the pleasure of staying there, which, as one of his aides-de-camp noted, ‘was certainly not the usual custom’.

The next day Schwarzenberg’s 200,000 men came into contact with Murat to the south, spending the whole day in patrols and skirmishes while Blücher advanced along the Saale and Elster rivers. Riding a cream-coloured mare that day, Napoleon distributed eagles and colours to three battalions. Drums beat as each was taken from its box and unfurled, to be given to the officers. ‘In a clear solemn tone, but not very loud, which might be distinguished by the musical term mezza voce’, a spectator recalled Napoleon saying:

‘Soldiers of the 26th regiment of light infantry, I entrust you with the French eagle. It will be your rallying point. You swear to abandon it but with life? You swear never to suffer an insult to France. You swear to prefer death to dishonour. You swear!’ He laid particular emphasis upon this last word, pronounced in a peculiar tone, and with great energy. This was the signal at which all the officers raised their swords, and all the soldiers, filled with enthusiasm, exclaimed with common consent, in a loud voice, accompanied by the ordinary acclamations: ‘We swear!’

This ceremony used to be attended by band music, but no longer: ‘Musicians had become scarce, since the greater part of them had been buried in the snows of Russia.’41

• • •

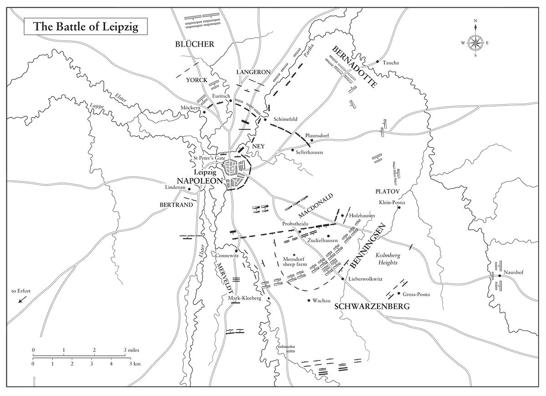

Among the half-million men who fought at Leipzig in ‘The Battle of the Nations’ – the largest battle in European history up to that moment – were French, Germans (on both sides), Russians, Swedes, Italians, Poles, every nationality within the Austrian Empire and even a British rocket section.42 The battle was fought over three days, on the 16th, 18th and 19th of October 1813. Napoleon had almost the whole of the French field army under him, comprising 203,100 men, of whom only 28,000 were cavalry, and 738 guns. Those absent were Saint-Cyr’s corps at Dresden (30,000 men), Rapp’s besieged at Danzig (36,000), Davout’s at Hamburg (40,000) and some 90,000 who were in hospital. In total by the last day of the battle the Allies had been able to bring up a total of 362,000 men and 1,456 guns, almost twice as many as the French.43 The battlefield was vast, cut in two by the Elster and Pleisse rivers, with open plains to the east and hills that provided artillery platforms and screened troops behind them.*

Captain Adolphe de Gauville, who was wounded at Leipzig, recalled that on the dark, gloomy and rainy morning of October 16, ‘at 5 a.m. Napoleon had an armchair and a table brought to him in a field. He had a great many maps. He was giving his orders to a great number of officers and generals, who came to receive them one after the other.’44 Napoleon calculated that he could engage 138,000 men against Schwarzenberg’s force of 100,000 to the south of the city and knew he had one or at best two days to subdue him before Blücher, Bernadotte and Bennigsen arrived from the north-west, north and east respectively. (Bennigsen’s advance troops – the Cossacks – arrived on the battlefield on the first day of combat, and the main body late on the 17th, ready for action the next day. Bernadotte’s troops also arrived then.)

The battle began early on the 16th when the Prussians took the village of Mark-Kleeberg from Poniatowski’s Poles in bitter street fighting made worse by racial hatred. Wachau was relatively lightly held and fell quickly to Russian forces backed by a Prussian brigade, but any attempt to push beyond it was stopped by French artillery. When Napoleon arrived there sometime between noon and 1 p.m. he formed a battery of 177 guns, under whose heavy cannonade he launched a major counter-attack, forcing the Russians back onto the Leipzig Plain, where there was no cover and grapeshot cut many of them down.

The Austrian General Ignaz Gyulai threatened Napoleon’s only escape route to the west – if one became necessary – so General Henri Bertrand’s corps was detached to protect it, significantly weakening Napoleon’s main attack. Gyulai became fixated on capturing Lindenau, near the road, and a real crisis developed in the late afternoon when the Austrians, despite strong artillery fire, stormed the burning village. Bertrand fell back and regrouped before counter-attacking at 5 p.m. He managed to clear the road completely, but Gyulai had made an important contribution by pinning down Bertrand’s corps.

At 10 a.m. Klenau advanced on Liebertwolkwitz, which fell quite quickly except for the church and the northern end of the village. A swift counter-attack pushed the Austrians straight back out again. General Gérard was wounded leading his largely Italian division against Klein-Posna before Mortier brought up his Young Guard divisions to secure the area. By 11 a.m. the Allies were back at their start lines, exhausted and denuded of reserves. Napoleon, surprised by their aggression, had been forced to move his own reserves in sooner than he would have liked. Friant’s Old Guard took the Meusdorf sheep farm, and two divisions of the Young Guard under Oudinot and the mass of reserve cavalry concentrated behind Wachau.

As the fog lifted across the battlefield, Napoleon could assess his clear superiority. Seeing an opportunity to split the Allied line at its weakest point at Wachau, he threw Macdonald’s corps in at noon to turn the Allied right flank. At about 2 p.m. he personally encouraged the 22nd Légère to storm the heights dominating Gross-Posna, known as the Kolmberg, teasing them with the taunt that they were merely standing at the base under heavy fire with their arms crossed.45 Although they took the heights, their movement was spotted by Alexander, Frederick William and Schwarzenberg, who sent in the Prussian reserves to stop them. (As earlier in the campaign, the two monarchs were now there in merely advisory and morale capacities, with the military decisions being taken by the professional soldiers.)

Out on the plain, Murat massed cavalry between Wachau and Liebertwolkwitz in dense columns to support Oudinot and Poniatowski. At 2.30 p.m. Bordessoulle’s cavalry led the charge in the centre, breaking through the Prince of Württemberg’s infantry and getting in among the artillerymen of the Allied grand battery. Eighteen squadrons, totalling 2,500 sabres, charged the Russian Guard Cavalry Division and overthrew it, heading on towards the Allied headquarters. Yet the French infantry failed to follow up this charge, and after Bordessoulle’s force was slowed by marshy ground it had to retreat, and took a good deal of punishment as it did so, including from friendly fire.

Napoleon had been waiting for Marmont to arrive from the north but by 3 p.m. he decided to launch his general assault with the troops he had at hand. He pushed his artillery well forward to batter the enemy centre, launched continual cavalry charges and counter-charges, ordered infantry volleys at close range and brought the Allied line almost to breaking point, but fresh Austrian troops, some of whom waded up to their waists in the Pleisse to enter the action faster, and the sheer stubbornness of the Russian and Prussian formations prevented a French breakthrough.

Hearing sustained cannon-fire from the direction of Möckern, Napoleon galloped to the northern part of the battlefield, where Blücher had engaged Marmont. Savage hand-to-hand fighting took place in the narrow streets of Möckern, and when Marmont tried to get onto the heights beyond the village Yorck unleashed a cavalry charge supported by infantry. Marmont’s men were forced back inside Leipzig. Ney had been falling back steadily towards the city, abandoning one strong position after another instead of delaying Blücher’s and Bernadotte’s advance.

With the Allies closing in on three sides, Napoleon was forced to spread the French attacks too thinly to be decisive at any one point. By 5 p.m. both armies were ready to end the first day’s fighting. The casualties were great, amounting to around 25,000 French and 30,000 Allies.46 That night, he ought to have slipped away along the road to the west, extricating himself before Schwarzenberg received massive reinforcements. Yet instead he allowed the whole of October 17 to pass by in rest and recuperation, requesting an armistice (which was refused) and sending the senior Austrian general captured that day, Maximilian von Merveldt, to Emperor Francis with a crudely anti-Russian message. ‘It’s not too much for Austria, France, and even Prussia to stop on the Vistula the overflowing of a people half nomad, essentially conquering, whose huge empire spreads from here all the way to China,’ he said, adding ‘I have to finish by making sacrifices: I know it; I am ready to make them.’47 The sacrifices he told Fain he would be willing to make for peace included an immediate renunciation of the Grand Duchy of Warsaw, Illyria and the Rhine Confederation. He was also willing to consider independence for Spain, Holland and the Hanseatic Towns, although that could only be part of a general settlement that also included Britain. For Italy he wanted ‘the integrity and independence of the Kingdom’, which sounded ambiguous, unlike his actual offer to Austria to evacuate Germany and withdraw behind the Rhine.48 Francis did not reply to the offer for three weeks, by which time the situation had radically altered to Napoleon’s disadvantage.49

Wellington later said that if Napoleon had withdrawn from Leipzig earlier, the Allies couldn’t have ventured to approach the Rhine.50 But to retreat from Leipzig without an armistice would effectively mean abandoning tens of thousands of men in the eastern fortress garrisons. Napoleon feared that the Saxons and Württembergers would then fall away from him as the Bavarians already had done. So instead of retreating towards Erfurt he organized his munitions supply – the French artillery was to fire 220,000 cannonballs during the battle, three times more even than at Wagram – and concentrated his whole army in a semicircle on the north-east and southern sides of the city, while sending Bertrand and Mortier to secure the exit routes should an escape become necessary.51 He succumbed to a heavy bout of influenza on the night of the 17th, but he had decided to fight it out. However, the arrival of Bernadotte’s and Bennigsen’s divisions meant that while Napoleon had been reinforced by the addition of 14,000 men of Reynier’s corps since the start of the battle, Schwarzenberg had been reinforced by over 100,000 men.52

After riding out towards Lindenau at about 8 a.m. on October 18, Napoleon spent most of the day at the tobacco mill at Thonberg, where the Old Guard and Guard cavalry were held in reserve.* By that time, the sun was shining and the armies were ready to engage. For the renewal of the battle Schwarzenberg had organized six great converging attacks, comprising 295,000 men and 1,360 guns. He hoped to take Connewitz, Mark-Kleeberg, Probstheida, Zuckelhausen, Holzhausen, Lindenau and Taucha before crushing the French army in Leipzig itself.

When Bennigsen arrived later in the morning he captured Holzhausen and its neighbouring villages from Macdonald. To Macdonald’s left were Reynier’s reinforcements, who included 5,400 Saxons and 700 Württembergers, but at 9 a.m. these fresh arrivals suddenly deserted to the Allies with thirty-eight guns, leaving a yawning gap in Napoleon’s line that General Jean Defrance’s heavy cavalry division attempted to fill.53 The Saxon battery actually turned around, unlimbered and began firing on the French lines. They had fought for Napoleon for seven years since deserting the Prussians after Jena, and such cool treachery was bad for French morale.

Von Bülow soon captured the village of Paunsdorf. Napoleon threw in units from the Old and Young Guard to recapture it, but the sheer weight of Prussian numbers forced even these elite units out. Probstheida, defended by Victor and Lauriston, became a veritable fortress that could not be seized at all that day despite the Tsar taking a close personal interest in its capture. Two Prussian brigades tried three times without success, and the 3rd Russian Infantry Division had to fall back sullenly behind its screen of light infantry. Napoleon was so concerned by the weight of these attacks that he pushed Curial’s Old Guard Division up in support, but was thankful they weren’t needed.

North of Leipzig a battle raged for Schönefeld between Marmont and Langeron, a French émigré general fighting in the Russian army. By bringing up all the guns of Souham’s corps to add to his, Marmont managed to oppose Langeron’s 180 cannon with 137 of his own. The ground between these two enormous batteries was swept clear: six French generals were killed or wounded in cannonading that carried on until nightfall, when Marmont evacuated back to his entrenchments outside Leipzig. While Langeron engaged Marmont, Blücher pushed for the suburbs of Leipzig. Ney launched two divisions in a counter-attack, contesting the village of Sellerhausen. It was in this engagement that the British fired their noisy and highly lethal Congreve rockets with powerful effect, not least on French morale. Although rockets had been known about for sixteen years, and their efficacy had been attested at Copenhagen in 1807, Napoleon hadn’t developed a rocket capacity of his own.

Napoleon personally led some Old Guard and Guard cavalry over to counter-attack at Zwei-Naundorf at about 4.30 p.m., standing aside only at the last minute as they went into action. But the Allies fought them to a standstill and a tide of Russians and Prussians drove the French steadily backwards. ‘Here, I saw the Emperor under a hail of enemy canister,’ recalled Johann Röhrig, a company sergeant-major of French voltigeurs. ‘His face was pale and as cold as marble. Only occasionally did an expression of rage cross his face. He saw that all was lost. We were only fighting for our withdrawal.’54 After having to pay 2 crowns (that is, six francs, or three days’ wages) for eight potatoes from some Old Guard grenadiers, Röhrig wrote of that day:

I cannot understand that such a clever commander as the Emperor could let us starve. It would have been a very different life in that army if sufficient food had been available. And yet, no one who has not experienced it can have any idea of the enthusiasm which burst forth among the half-starved, exhausted soldiers when the Emperor was there in person. If all were demoralized and he appeared, his presence was like an electric shock. All shouted ‘Vive l’Empereur!’ and everyone charged blindly into the fire.55

Each side lost around 25,000 men in the bitter cannonades and hand-to-hand fighting that day.

• • •

On the morning of October 19, Napoleon finally decided that the army should retreat. He told Poniatowski, to whom he had awarded a marshal’s baton three days earlier, ‘Prince, you will defend the southern suburbs.’ ‘Sire, I have so few men,’ replied the Pole. ‘Well, you will defend yourself with what you have!’ said Napoleon. ‘Ah! Sire,’ answered the newly minted marshal, ‘we will hold on! We are all ready to die for your Majesty.’56 Later that day, he was as good as his word. Napoleon left the city at about 10 a.m. after visiting the King of Saxony, whose battlefield commander had not defected to the Allies as so many of his men had. ‘Napoleon had the appearance of composure on his countenance when he quitted Leipzig,’ recalled Colonel von Odeleben, ‘riding slowly through St Peter’s Gate, but he was bathed in sweat, a circumstance which might proceed from bodily exertion and mental disturbance combined.’57 The retreat was chaotic, with ‘Ammunition wagons, gendarmes, artillery, cows and sheep, women, grenadiers, post-chaises, the sound, the wounded, and the dying, all crowded together, and pressed on in such confusion that it was hardly possible to hope that the French could continue their march, much less be capable of defending themselves.’58 The confusion worsened considerably once the Allied assault on the city began at 10.30 a.m.

Pontoon bridges had not been built over the Pleisse, Luppe or Elster rivers, so everyone had to cross by the single bridge over the Pleisse in the city, which was reached at the end of a series of narrow streets. Catastrophically, the bridge was blown up at 11.30 a.m., long before the whole army had got over it, which led to well over 20,000 men being captured unnecessarily and turned the defeat into a rout. Napoleon’s 50th bulletin blamed Colonel Montfort by name for delegating the duty to a ‘corporal, an ignorant fellow but ill comprehending the nature of the duty with which he was charged’.59 People and animals were still on the bridge when the explosion shook the city, raining the body parts of humans and horses into the streets and river.60 Some officers decided to try to swim across to avoid capture. Macdonald made it, but Poniatowski’s horse, which he had ridden into the river, could not climb up the opposite bank and fell back on top of him. Both were swept away by the current.61 The fisherman who hauled Poniatowski’s corpse out of the river did well from selling his diamond-studded epaulettes, rings and snuffboxes to Polish officers who wanted to return them to his family.62 Napoleon’s red-leather briefcase for foreign newspapers, emblazoned Gazettes Étrangères in gold lettering, was captured, along with his carriage, and opened in the presence of Bernadotte.*

‘Between a battle lost and a battle won,’ Napoleon had said on the eve of the battle of Leipzig, ‘the distance is immense and there stand empires.’63 Between the dead and the wounded, Napoleon lost around 47,000 men over the three days. Some 38,000 men were captured, along with 325 guns, 900 wagons and 28 colours and standards (including 3 eagles), making it statistically easily the worst defeat of his career.64 In his bulletin he admitted to 12,000 lost, and several hundred wagons, mainly as a result of the blown bridge. ‘The disorder it has brought to the army changed the situation,’ he wrote; ‘the victorious French army arrives at Erfurt as a defeated army would arrive.’65 After further desertions and defections, he was able to bring only 80,000 men of the Grande Armée back over the Saale out of the more than 200,000 he had had at the start of the battle. ‘Typhus broke out in our disorganized ranks in a terrifying fashion,’ Captain Barrès recalled. ‘Thus one might say that on leaving Leipzig we were accompanied by all the plagues that can devour an army.’66

Napoleon conducted a fighting retreat to the Rhine, sweeping aside the Austrians at Kösen on the 21st, the Prussians at Freiburg that same day, the Russians at Hörselberg on the 27th and, in a two-day battle on the 30th and 31st, the Bavarians at Hanau. He re-crossed the Rhine at Mainz on November 2. ‘Be calm and cheerful and laugh at the alarmists,’ he told his wife the next day.67

Napoleon still had 120,000 men besieged in the fortresses on the Elbe, Oder and Vistula, with Rapp inside Danzig (where his 40,000 effectives were reduced by the end to 10,000), and generals Adrien du Taillis in Torgau, Jean Lemarois in Magdeburg, Jean Lapoype in Wittenberg, Louis Grandeau in Stettin, Louis d’Albe in Küstrin and Jean de Laplane in Glogau, as well as more men in Dresden, Erfurt, Marienburg, Modlin, Zamosc and Wesel. Although Davout held Hamburg and the lower Elbe, most of these eastern fortresses fell one by one in late 1813, often as the result of starvation. A few held out until the end of the 1814 campaign, but none played any useful part besides holding down local militia units in sieges. It was a sign of Napoleon’s invincible optimism to have left so many men so far to the east. By 1814, most of them were prisoners-of-war.

The 1813 campaign had claimed the lives of two marshals, Bessières and Poniatowski, and no fewer than thirty-three generals. It also saw the defection of Murat, who while he was with Napoleon at Erfurt on October 24, secretly agreed to join the Allies in exchange for a guarantee that he would remain king of Naples. Yet Napoleon was not disheartened, or at least not publicly. Arriving in Paris on November 9 he (in Fain’s words) ‘exerted every effort to turn his remaining resources to the best account’.68 He replaced Maret as foreign minister with Caulaincourt (after twice offering the position to the unemployed Talleyrand in order to show his conciliatory intentions), imposed an emergency levy of 300,000 new recruits, of which he got 120,000 despite the now powerful anti-conscription sentiment in the country, and seriously entertained a peace offer from the Allies, brought from Frankfurt by the Baron de Saint-Aignan, his former equerry and Caulaincourt’s brother-in-law.69 Under what were termed the Frankfurt bases of peace, France would return to her so-called ‘natural frontiers’ of the Ligurian Alps, the Pyrenees, the Rhine and the Ardennes – the so-called ‘Bourbon frontiers’ (even though the Bourbons had regularly crossed them in wars of conquest). Napoleon would have to abandon Italy, Germany, Spain and Holland, but not all of Belgium.70 At that point, with only a few garrisons holding out in Spain and unable to defend the Rhine with anything more than bluster, Napoleon told Fain he was prepared to surrender Iberia and Germany, but he resisted giving away Italy, which in wartime ‘could provide a diversion to Austria’, and Holland, which ‘afforded so many resources’.71

On November 14, the same day that the Frankfurt proposals arrived, Napoleon made a speech to Senate leaders at the Tuileries. ‘All Europe was marching with us just a year ago,’ he told them frankly, ‘today all Europe is marching against us. The fact is that the opinion of the world is formed by France or by England . . . Posterity will say that if great and critical circumstances arose they were not too much for France or for me.’72 The next day he instructed Caulaincourt that if the British army arrived at the Château de Marracq near Bayonne ‘it be set fire to, also all the houses which belong to me, so that they may not sleep in my bed’.73

Although he ordered the doubling of the droits réunis on tobacco and postage and doubled the tax on salt in order to raise 180 million francs, he admitted to Mollien that the measures were ‘a digestif that I was saving to the last moment of thirst’. As he was down to 30 million francs in the treasury, that moment had now arrived.74 He ordered that all payments of pensions and salaries be suspended so that the orders made by the war administration ministry could still be honoured.

After the Allies made the Frankfurt terms public on December 1, stating that they would ‘guarantee the French Empire a larger extent of territory than France ever knew under her kings’, Pasquier and Lavalette informed Napoleon that their intelligence services indicated the French people wanted him to accept.75 ‘The moment of the rendezvous has arrived,’ Napoleon told Savary melodramatically; ‘they look at the lion as dead, who will begin taking his delayed vengeance? If France abandons me, I cannot do anything; but they’ll soon regret it.’76 The following day Caulaincourt wrote to Metternich agreeing to the ‘general and summary bases’.77 On December 10, as Wellington crossed the Nive river and Soult withdrew to the Adour, Metternich replied to say that the Allies were waiting for Britain’s reply to Caulaincourt’s offer. The Napoleonic Wars could have ended there and then, but the British were opposed to a peace that left France in possession of any part of the Belgian coast from which Britain could be invaded, specifically Antwerp. Castlereagh’s opposition to Metternich’s terms wrecked the Frankfurt peace attempt, especially once he had arrived in Europe in January 1814 and encouraged the Tsar to oppose peace of any kind with Napoleon.78 He did not believe that a lasting peace would be possible if Napoleon remained on the throne of France.

‘Brilliant victories glorified French arms during this campaign,’ Napoleon told the Legislative Body on December 19, ‘defections without example rendered those victories useless. Everything turned against us. Even France would be in danger were it not for the energy and unity of Frenchmen.’ Only Denmark and Naples remained faithful, he said – though privately he was having doubts about Naples, telling his sister the Grand Duchess Elisa of Tuscany not to send any muskets to their sister Caroline and her husband, Murat, who were back in Italy negotiating with the Austrians once more. He told the Legislative Body that ‘he would raise no objection to the re-establishment of peace’, and ended defiantly: ‘I have never been seduced by prosperity; adversity shall find me superior to its blows.’79

Napoleon’s speech to the Senate was equally tough-minded. ‘At the sight of the whole nation in arms, the foreigner will flee or sign peace on the bases which he himself proposed. It is no longer a question of recovering the conquests we have made.’80 Although the Senate stayed loyal, on December 30 the Legislative Body voted by 223 to 51 in favour of a long critique of Napoleon’s actions, which ended with a demand for political and civil rights. ‘A barbarous and endless war swallows up periodically the youth torn from education, agriculture, commerce and the arts,’ it concluded.81 The French had allowed him his first defeat in Russia, but this second catastrophe at Leipzig, coming so soon afterwards, turned many of them against him. If he wished to remain in power, Napoleon had little alternative other than to banish the document’s authors, led by Joseph Lainé, and forbid its publication. The next day he prorogued the Legislative Body.

With fewer than 80,000 men under arms, Napoleon now faced 300,000 Russians, Prussians and Austrians on the Rhine, and 100,000 Spanish, British and Portuguese coming over the Pyrenees.82 ‘The moment when the national existence is threatened is not the one to come to talk to me about constitutions and the rights of the people,’ Napoleon told Savary. ‘We are not going to waste our time in puerile games while the enemy is getting closer.’83 Now that the Allies were crossing the Rhine, national unity was more important than political debate. France was about to be invaded and Napoleon was determined to fight.