30

‘I sensed that Fortune was abandoning me. I no longer had in me the feeling of ultimate success, and if one is not prepared to take risks when the time is ripe, one ends up doing nothing.’

Napoleon on the Waterloo campaign

‘A general-in-chief should ask himself several times in the day, what if the enemy were to appear now to my front, or on my right, or on my left?’

Napoleon’s Military Maxim No. 8

By the time Napoleon went to bed at three o’clock on the morning of Tuesday, March 21, 1815, he had largely reconstituted his government. The Vienna Declaration made it clear that the Allies would not allow him to retain the throne, so he needed to prepare France for invasion, but he hoped that – unlike in 1814 – ordinary Frenchmen would actively rally to him, having now experienced the Bourbon alternative. To an extent they did; over the next few weeks there were as many recruits as the depots could handle. It was a wrenching moment for Frenchmen to decide where their true loyalties lay. Of the Bonaparte family, Joseph was received with affection by him on the 23rd – Napoleon no longer suspected him of making a move on Marie Louise – Lucien came from his self-imposed exile in Rome and was ‘speedily admitted’ into his presence and forgiven for everything, Jérôme was given the 6th Division to command, Cardinal Fesch returned to France and Hortense became the chatelaine of the Tuileries. Louis and Eugène stayed away, the latter at the behest of his father-in-law, the King of Bavaria. Marie Louise remained in Austria, fervently hoping that Napoleon, to whom she had written for the final time on January 1, would be defeated.1 In a letter to a friend of April 6, the infatuated young woman mentioned the exact number of days – eighteen – since she had last seen General Neipperg, and in her last oral message to Napoleon soon afterwards she asked for a separation.2

The unfeigned surprise shown by senior statesmen such as Cambacérès at the news of Napoleon’s return confirms that it was not the result of a widespread conspiracy, as the Bourbons suspected, but of the willpower and opportunism of one man.3 Cambacérès reluctantly went to the justice ministry, complaining ‘All I want is rest.’4 A few – such as the adamant republican Carnot, who went to the interior ministry – joined Napoleon because they genuinely believed his assurances that he would now be acting as a constitutional monarch who respected the civil rights of Frenchmen.* Other ministers, such as Lavalette, were dyed-in-the-wool Bonapartists. Decrès went back to the naval ministry, Mollien to the treasury, Caulaincourt to the foreign ministry and Daru to war administration. Maret became secretary of state, while Boulay de la Meurthe and Regnaud de Saint-Jean d’Angély returned to their key positions in the Conseil and Molé to his old inspectorate of roads and bridges.5 Savary took over the gendarmerie and even Fouché was allowed back into the police ministry – a sign of how indispensable he was despite his chronic untrustworthiness. Overall, Napoleon had gathered easily enough talent and experience to run an efficient administration if the military situation could somehow be squared. When he saw Rapp, who had been given a divisional command by the Bourbons, he playfully (and perhaps a little painfully) punched him in the solar plexus, saying, ‘What, you rogue, you wanted to kill me?’ before making him commander of the Army of the Rhine. ‘In vain he sought to assume the mask of severity,’ Rapp wrote in his posthumously published autobiography, but ‘kind feelings always gained the ascendancy.’6 One of the few people who wrote a letter asking for re-employment to be refused was Roustam. ‘He’s a coward,’ Napoleon told Marchand. ‘Throw that in the fire and never ask me again about it.’7 It was understandable that he should not want as his principal bodyguard someone who had fled Fontainebleau in the night the previous year. His place was taken by Louis-Étienne Saint-Denis, who since 1811 had been dressed by Napoleon as a Mamluk and called Ali, despite his being a Frenchman born in Versailles.

On March 21 the Moniteur, which once again changed its editorial policy the moment he returned to power, printed the name NAPOLEON in capital letters no fewer than twenty-six times in the course of four pages, telling the news of his triumphant return.8Napoleon rose at six o’clock that morning after only three hours’ sleep, and at 1 p.m. held a grand parade in the courtyard of the Tuileries. Commandant Alexandre Coudreux described Napoleon’s arrival to his son:

The Emperor, on horseback, reviewed all the regiments and was welcomed with the enthusiasm that the presence of such a man inspired in the brave men whom for some days the last government had treated as murderers, Mamluks and brigands. For the four hours that the troops remained under arms, the cries of joy were interrupted only for the few minutes that Napoleon spent addressing the officers and non-commissioned officers gathered around him in a circle with a few of those beautiful, if vigorous phrases that belong to him alone, and that have always made us forget all our ills and defy all dangers! [Cries of ‘Vive l’Empereur!’ and ‘Vive Napoléon!’ were] repeated thousands of times, [and] must have been heard throughout the whole of Paris. In our euphoria, we all hugged each other without distinguishing between grade nor rank, and more than fifty thousand Parisians, witnessing such a fine scene, applauded these noble and generous demonstrations with all their hearts.9

Napoleon’s work ethic remained unchanged: in the three months between his return to the Tuileries and the battle of Waterloo he wrote over nine hundred letters, the great majority of them concerned with trying to put France back onto a war footing in time for the coming hostilities. On the 23rd he ordered Bertrand to have various items brought to Paris from Elba, including a particular Corsican horse, his yellow carriage and the rest of his underwear.10 Two days later he was already writing to his grand chamberlain, Comte Anatole de Montesquiou-Fezensac, about that year’s theatre budgets.11

• • •

The only marshal besides Lefebvre to report for duty at the Tuileries immediately was Davout, even though he had been shamefully underused in the 1813 and 1814 campaigns, tied up in Hamburg rather than unleashed against France’s enemies. After Napoleon’s abdication he had been one of the few marshals who refused to take the oath of loyalty to Louis XVIII. But Napoleon now made a serious error when he appointed Davout war minister, governor of Paris and commander of the capital’s National Guard, thereby denying himself the services of his greatest marshal on the battlefields of Belgium. Some have speculated that the lack of personal rapport between the two of them might have been behind Napoleon’s decision, or that Napoleon thought he needed Davout in Paris in case of a siege – but if the field campaign was not won decisively and swiftly it wouldn’t matter who was in charge in Paris.12 Napoleon did in fact understand this fully, telling Davout on May 12, ‘The greatest misfortune we have to fear is that of being too weak in the north and to experience an early defeat.’13 On the day of the battle of Waterloo, however, Davout was signing bureaucratic documents about peacetime army pay grades.14 Years later, Napoleon regretted not putting either General Clauzel or General Lamarque in the war ministry instead.15 At the time he inundated Davout with his customary letters, such as one on May 29 when, after an eagle-eyed review of five artillery batteries bound for Compiègne, he wrote, ‘I noticed that several gun caissons didn’t have their little pots of grease or all their replacement parts, as required by order.’16

Of the nineteen marshals on the active list (Grouchy was awarded his baton on April 15) only ten – namely Davout, Soult, Brune, Mortier, Ney, Grouchy, Saint-Cyr, Masséna, Lefebvre and Suchet – declared for Napoleon (or eleven if one counts Murat’s quixotic and, as it turned out, suicidal decision to support the man whom he had been the very first to desert). But it wasn’t until April 10 that Masséna in Marseilles put out a proclamation in favour of ‘our chosen sovereign, the great Napoleon’, and afterwards he did nothing.17 Similarly Saint-Cyr stayed on his estate, and Lefebvre, Moncey and Mortier were too ill to be of any service. (Mortier would have commanded the Imperial Guard but for his severe sciatica.)18 Napoleon assumed that Berthier would rejoin him, and joked that the only revenge he would take would be to oblige him to come to the Tuileries wearing the uniform of Louis XVIII’s Guards. But Berthier left France for Bamberg in Bavaria, where he fell to his death from a window on June 15. Whether this was suicide, murder or an accident – there was a history of epilepsy in the family – is still unknown, but it was most probably the first.19 We can only guess at the internal conflict and despair which may have prompted such a course in Napoleon’s chief-of-staff after nearly twenty years of exceptionally close service. Berthier’s absence over the coming weeks was a serious blow.

Although fourteen marshals had fought in the Austerlitz campaign, fifteen in the Jena campaign, seventeen in the Polish campaign, fifteen in the Iberian campaign, twelve in the Wagram campaign, thirteen in the Russian campaign, fourteen in the Leipzig campaign and eleven in the 1814 campaign, only three – Grouchy, Ney and Soult – were present in the Waterloo campaign. From the small pool available to him, Napoleon needed a battle-tested commander for the left wing of the Army of the North to take on Wellington and he summoned Ney, who joined the army as late as June 11. But the war-weary Ney underperformed badly throughout. On St Helena Napoleon opined that Ney ‘was good for a command of ten thousand men, but beyond that he was out of his depth’.20 His place in charge of the left wing should have been taken by Soult, whom Napoleon appointed chief-of-staff, in which job he too badly underperformed. Instead of appointing Suchet or Soult’s lieutenant, General François de Monthion, chief-of-staff he wasted the former by sending him off to the Army of the Alps and kept Monthion, whom he disliked, in a junior role.

Of the other marshals, Marmont and Augereau had betrayed Napoleon in 1814; Victor stayed loyal to the Bourbons; the hitherto politically unreliable Jourdan was made a peer of France, governor of Besançon and commander of the 6th Military Division, while Macdonald and Oudinot stayed passively neutral. Oudinot, who returned to his home at Bar-le-Duc after his troops had declared for Napoleon, is credited with replying to the Emperor’s offer of employment: ‘I will serve no one, Sire, since I will not serve you.’21

• • •

In a series of proclamations from Lyons and later from the Tuileries, Napoleon swiftly undid many of the more unpopular Bourbon reforms. He cancelled changes in judicial tribunals, orders and decorations, restored the tricolour and the Imperial Guard, sequestered property owned by the Bourbons, annulled the changes to the Légion d’Honneur and restored to the regiments their old number designations that the Bourbons, with scant regard for military psychology, had replaced with royalist names. He also dissolved the legislature and convoked the electoral colleges of the Empire to meet in Paris in June at the Champ de Mars to acclaim the new constitution he was planning and ‘assist at the coronation’ of the Empress and the King of Rome.22 ‘Of all that individuals have done, written, or said, since the taking of Paris,’ he promised, ‘I shall for ever remain ignorant.’23 He was as good as his word; it was the only sensible basis on which to attempt to restore national unity. But this did not prevent yet another rising in the Vendée, against which Napoleon was forced to deploy 25,000 troops in an Army of the Loire under Lamarque, including newly raised Young Guard units that would have been invaluable at Waterloo. Troops also had to be sent to Marseilles – which hoisted the tricolour only in mid-April – Nantes, Angers and Saumur and a number of other places in a way that had not been necessary in earlier campaigns, except 1814.24

Napoleon made good on his promise to abolish the hated droits réunis taxes on returning to power, but this reduced his ability to pay for the coming campaign.25 Gaudin, who returned to the finance ministry, was told on April 3 that provisioning the army for the coming campaign would require an extra 100 million francs. ‘I think that all the other budgets can be reduced,’ Napoleon told him, ‘given that ministers have allowed themselves much more than they really need.’26 (Despite austerity measures, he still managed to find 200,000 francs in the imperial household budget for ‘musicians, singers, etc.’27) Gaudin drew heavily on the Civil List, took 3 million francs in gold and silver from the cashier-general of Paris, raised 675,000 francs in timber taxes, borrowed 1.26 million francs from the Banque de France, sold 380,000 francs’ worth of shares in the Canal du Midi, which, along with the sale of 1816 bonds and other government assets, as well as a tax on salt-mines and other industries, raised 17,434,352 francs in total.28 It would have to be a swift and instantly victorious campaign, as France could clearly not afford a drawn out series of engagements.

In order to substantiate his claim to wish to govern France liberally, Napoleon asked the moderate Benjamin Constant to return from internal exile in the Vendée and draw up a new constitution, to be called the Acte Additionnel aux Constitutions de l’Empire. This provided for a bicameral legislature which would share powers with the Emperor on the British model, a two-stage electoral system, trial by jury, freedom of expression and even powers of impeachment of ministers. In his diary at the time, Constant described Napoleon, whom he had earlier derided in published pamphlets as akin to Genghis Khan and Attila, as ‘a man who listens’.29 Napoleon later explained that he had wanted ‘to substantiate all the late innovations’ in the new constitution to make it harder for anyone to restore the Bourbons.30 Napoleon also ended all censorship (so much so that even the manifestos of enemy generals could be read in the French press), abolished the slave trade entirely, invited Madame de Stäel and the American Revolutionary War hero the Marquis de Lafayette into his new coalition (both distrusted Napoleon and refused*), and ordered that no Britons were to be detained or harassed. He also told the Conseil that he had entirely renounced all imperial ideas and that ‘henceforth the happiness and the consolidation’ of France ‘shall be the object of all my thoughts’.31 On April 4 he wrote to the monarchs of Europe, ‘After presenting the spectacle of great campaigns to the world, from now on it will be more pleasant to know no other rivalry than that of the benefits of peace, of no other struggle than the holy conflict of the happiness of peoples.’32

Historians have tended to scoff at these measures and statements, yet such was the exhausted state of France in 1815, with most of the population wanting peace, that if he had remained in power Napoleon might very well have returned to the kind of pacific government of national unity that he had operated during the Consulate. But his longtime foes could not believe he would give up his imperial ambitions, and certainly could not take the risk that he would do so. Nor could they have guessed that he would be dead in six years. Instead, as one British MP not unreasonably put it, it was assumed that peace ‘must always be uncertain with such a man, and . . . whilst he reigns, would require a constant armament, and hostile preparations more intolerable than war itself’.33On March 25 the Allies, still in congress at Vienna, formed a Seventh Coalition against him.

Napoleon took advantage of his brief return to power to restart various public works in Paris, including the elephant fountain at the Bastille, a new market place at Saint-Germain, the foreign ministry at the Quai d’Orsay and at the Louvre.34 Talma went back to teaching acting at the Conservatory, which had been closed by the Bourbons; Denon the Louvre director, David the painter, Fontaine the architect and Corvisart the doctor returned to their old jobs in the arts and medicine; Carle Vernet’s painting of Marengo was rehung at the Louvre, and some of the standards captured in the Napoleonic campaigns were put up in the Senate and Legislative Body.35 On March 31 Napoleon visited the orphaned daughters of members of the Légion d’Honneur, whose school at Saint-Denis had had its funding cut by the Bourbons. That same day he restored the University of France to its former footing, re-appointing the Comte de Lacépède as chancellor. The Institut de France also reinstated Napoleon as a member. At a concert at the Tuileries that March to celebrate his return, the thirty-six-year-old Anne Hippolyte Boutet Salvetat, a celebrated actress known as Mademoiselle Mars, and Napoleon’s old flame from the Italian campaign, Mademoiselle George, both wore the new Bonapartist emblem inspired by his springtime reappearance – a sprig of violets.

Yet none of these acts of public relations could dispel the growing belief on the part of most Frenchmen that disaster loomed. In April, conscription was extended to hitherto exempted married men. That month John Cam Hobhouse, a twenty-eight-year-old Radical writer and future British cabinet minister who was at the time living in Paris, noted: ‘Napoleon is not popular, except with the actual army, and with the inhabitants of certain departments; and, perhaps even with them, his popularity is only relative.’ Hobhouse was a fanatical Bonapartist, yet even he had to admit that the Saint-Germain nobles hated Napoleon, that the shopkeepers wanted peace and that although the regiments cried out ‘Vive l’Empereur!’ with feeling there was no echo from the populace, who made ‘no noise nor any acclamations; a few low murmurs and whispers were alone heard’ when the Emperor rode through the city.36 By mid-April the conspicuous non-arrival from Vienna of Marie Louise and the King of Rome – ‘the rose and the rosebud’ as propagandists termed them – further alerted Parisians to the inevitability of war.37

At the Tuileries on April 16 Hobhouse watched Napoleon reviewing twenty-four battalions of the National Guard – which now accepted all able-bodied men between the ages of twenty and sixty. As the troops took two hours to march past, and Hobhouse was standing only ten yards away, he had ample opportunity to study his hero, who he thought looked nothing like his portraits:

His face was of a deadly pale; his jaws overhung, but not so much as I had heard; his lips thin, but partially curled . . . His hair was of a dark dusky brown, scattered thinly over his temples: The crown of his head was bald . . . He was not fat in the upper part of his body, but projected considerably in the abdomen, so much so that his linen appeared beneath his waistcoat. He generally stood with his hands knit or folded before him . . . played with his nose; took snuff three or four times, and looked at his watch. He seemed to have a labouring in his chest, sighing or swallowing his spittle. He very seldom spoke, but when he did, smiled, in some sort, agreeably. He . . . went through the whole tedious ceremony with an air of sedate impatience.38

Although some soldiers stepped out of the ranks to deliver their petitions to the grenadier on guard – a hangover from the revolutionary army tradition – when others seemed scared of doing so Napoleon beckoned to have their petitions collected. One was presented by a six-year-old child dressed in a pioneer uniform, complete with false beard; he gave it to the Emperor on the end of a battle-axe, and Napoleon ‘took and read [it] very complacently’.39

• • •

On April 22, 1815 Constant published the Acte Additionnel, which was then put to a plebiscite: 1,552,942 voted yes and 5,740 voted no, numbers which need to be treated with the same reservations as in earlier plebiscites. (People who voted both yes and no in error counted as a yes, for example; the overall turnout was only 22 per cent.40 In the Seine-Inférieure, only 11,011 yes and 34 no votes were cast, compared with 62,218 who voted in the 1804 plebiscite.41) ‘At no period in his life had I seen him enjoy more unruffled tranquillity,’ recorded Lavalette, who reported to Napoleon daily. He put this down to the endorsement of the Acte Additionnel, which managed to blur political distinctions between liberals, moderate republicans, Jacobins and Bonapartists in what has been dubbed ‘Revolutionary Bonapartism’.42

By late April 1815 a generally spontaneous fédéré militia movement was growing to hundreds of thousands of Frenchmen whose aim was to rebuild the sense of national unity France was believed to have felt at the time of the fall of the Bastille.43 Thefédérésheld assemblies twice a week and required a signed commitment and sworn oath to confront the Bourbons with force; in much of the country they kept the royalists quiescent (at least until Waterloo, after which they were brutally suppressed).44 Only in the fiercely anti-Bonapartist parts of France – Flanders, Artois, the Vendée and the Midi – did Revolutionary Bonapartism get nowhere. Otherwise it crossed the social classes: in Rennes the middle classes dominated the local fédéré organization whereas in Dijon it was made up of working men, while in Rouen it was indistinguishable from the National Guard. The fédérés had no effect on the war, but they were an indication of the widespread support Napoleon enjoyed in the country, and that he might have been able to stir up a guerrilla campaign after Waterloo had he chosen to do so.

On May 15 the Allies formally declared war on France. Molé saw Napoleon at the Élysée Palace, where he had moved for its secluded garden, two days later and found him ‘gloomy and depressed, yet calm’. They spoke of the possible partition of the country.45In public Napoleon maintained his customary sangfroid, however. At a review of five battalions of the Line and four of the Young Guard at the Tuileries later that month he was pulling grenadiers’ noses and playfully slapping a colonel, after which ‘the officer went away, smiling and showing his cheek, which was red with the blow.’46

The Acte Additionnel was ratified at a gigantic open-air ritual called the Champ de Mai, which confusingly took place on the Champ de Mars, outside the École Militaire, on June 1. ‘The sun, flashing on sixty thousand bayonets,’ recalled Thiébault, ‘seemed to make the vast space sparkle.’47 During this strange mixture of religious, political and military ceremony, loosely based on one of Charlemagne’s traditions, Napoleon, wearing a purple costume not unlike his coronation mantle, spoke to 15,000 seated Frenchmen and over 100,000 more milling in the crowd. ‘As emperor, consul, soldier, I owe everything to the people,’ he said. ‘In prosperity, in adversity, on the battlefield, in counsel, enthroned, in exile, France has been the sole and constant object of my thoughts and actions. Like the King of Athens, I sacrificed myself for my people in the hope of seeing fulfilled the promise to preserve for France her natural integrity, honour and rights.’48* He went on to explain that he had been brought back to power by public indignation at the treatment of France and that he had counted on a long peace because the Allies had signed treaties with France – which they were now breaking by building up forces in Holland, partitioning Alsace-Lorraine and preparing for war. He ended by saying, ‘My own glory, honour and happiness are indistinguishable from those of France.’ Needless to say, the speech was followed by prolonged cheering, before a massive march-past by the army, departmental representatives and National Guard.49 The whole court, Conseil, senior judiciary and diplomatic and officer corps in their uniforms were present, and ladies in their diamonds. With a hundred-gun salute, drumrolls, a vast amphitheatre, eagles emblazoned with the names of each department, gilded carriages, solemn oaths, a chanted Te Deum, red-coated lancers, an altar presided over by archbishops and heralds in their finery, it was an imposing spectacle.50 During Mass, Napoleon looked at the assembly through an opera glass. Hobhouse had to admit that when the Emperor ‘plumped himself down on his throne and rolled his mantle round him he looked very ungainly and squat’.

The newly elected chambers took their oath of allegiance to the Emperor with minimal difficulty two days later, even though the elections the previous month had resulted in a number of constitutionalists, liberals, crypto-royalists and Jacobins being elected. With the lower house immediately sidetracked into an ill-tempered debate about whether members should be allowed to read speeches from notes hidden in their hats, the legislature was unlikely to cause Napoleon much immediate cause for concern, despite the fact that his long-term opponent, the former senator the Comte Lanjuinais, had been elected its president and Lafayette was now a deputy. There was a huge firework display in the Place de la Concorde the following evening, which featured Napoleon arriving in a ship from Elba. As a spectator recorded: ‘The mob cried “Vive l’Empereur and the fireworks!” and the reign of the Constitutional Monarchy began.’51 Of course it wasn’t a constitutional monarchy as in Britain, since the ministers were all appointed by Napoleon, who was his own prime minister, but neither was it the unfettered dictatorship of the pre-1814 period, and it seemed possible that it might evolve liberally.

Napoleon knew that his success or failure would ultimately be determined solely on the battlefield. On June 7 he ordered Bertrand to get his telescopes, uniforms, horses and carriages made ready ‘so that I can leave two hours after having given the order’, adding: ‘As I will be camping often, it is important that I have my iron beds and tents.’52 That same day he told Drouot: ‘I was pained to see that the men in the two battalions that left this morning had only one pair of boots each.’53 Two days later, on June 9, 1815, the Allies signed the Treaty of Vienna. Under Article I they reaffirmed their intention of forcing Napoleon from the throne, and under Article III they agreed that they would not lay down their arms until this was achieved.54

• • •

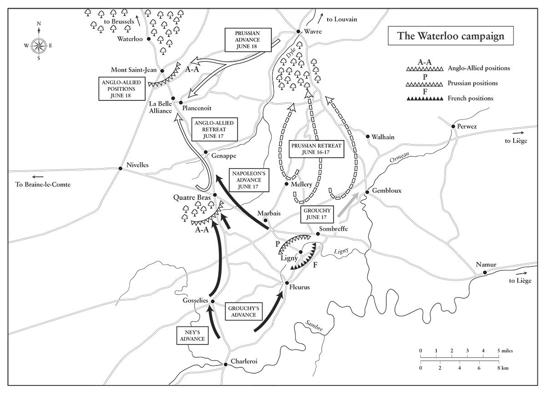

As early as March 27 Napoleon had told Davout that ‘the Army of the North will be the principal army’, as the closest Allied forces were in Flanders and he certainly did not intend to wait for Schwarzenberg’s return to France.55 At 4 a.m. on Monday, June 12 Napoleon left the Élysée to join the Army of the North at Avesnes, where he dined with Ney the next day. By noon on the 15th he was at Charleroi in Belgium, ready to engage the Prussian army under Blücher near Fleurus. He hoped to defeat Blücher before falling on an Anglo-Dutch-Belgian-German force under Wellington, 36 per cent of whose troops were British while 49 per cent spoke German as their first language.

Napoleon later said that ‘he had relied mainly . . . upon the idea, that a victory over the English army in Belgium . . . would have been sufficient to have produced a change of administration in England, and have afforded him a chance of concluding an immediate general truce.’56 Capturing Brussels, part of the French Empire until 1814, would also have been good for morale. To fight was a risk, but not so great a risk as waiting until the vast Austrian and Russian armies were ready to strike at Paris once again. Across Europe, 280,000 French soldiers faced around 800,000 Allies, although the Austrian contingent would not be in theatre for several weeks, and the Russians not for months. ‘If they enter France,’ Napoleon told the army from Avesnes on June 14, ‘therein they will find their tomb . . . For all the French who have the courage, the time has come to vanquish or perish!’57

The opening stages of the campaign saw him reviving the best of the strategic abilities he had shown the previous year. The French were even more scattered than the Allies at first, across an area 175 miles wide by 100 deep, but Napoleon used this fact to feint towards the west and then concentrate in the centre in classic bataillon carré style. The manoeuvring of the 125,000-strong Army of the North between June 6 and the 15th allowed it to cross the rivers at Marchienne, Charleroi and Châtelet without any Allied reaction of note. Wellington, who had arrived post-haste from Vienna on April 5, had been forced to string his force out along a 62-mile-wide front, trying simultaneously to guard the routes to Brussels, Antwerp and Ghent. He frustratedly acknowledged as much when he said on the evening of June 15, ‘Napoleon has humbugged me, by God.’58

Napoleon’s speed and tactical ability allowed him once again to strike at the hinge between the armies opposing him, as he had been doing for nearly twenty years. His manoeuvres were all the more impressive as half of his army was made up of raw recruits. Although veterans had been released from Spanish, Russian and Austrian prisoner-of-war camps, after the initial rush of enthusiasm only 15,000 volunteers had joined the colours, so conscription provided the balance. Morale among the troops was shaky, especially after the former Chouan leader, General Bourmont, and his staff defected to the Allies on the morning of the 15th.59 Some of the men understandably asked why generals who had pledged oaths to the Bourbons, such as Soult, Ney, Kellermann and Bourmont, had been allowed back at all. Low morale led to poor discipline, with the Imperial Guard plundering freely in Belgium and laughing at the gendarmes sent to stop them.60 Equipment was also wanting: the 14th Légère had no shakos, the 11th Cuirassiers no breastplates. (‘Breastplates aren’t necessary to make war,’ Napoleon blithely told Davout on June 3.) The Prussians reported that some battalions of the Imperial Guard, reconstituted on March 13 when Napoleon was in Lyons, looked more like a militia, wearing an assortment of forage caps and bicornes instead of their fearsome bearskins. The Middle Guard, disbanded by the Bourbons, had been recalled only the previous month.

On June 16, Napoleon divided his army into three. Ney took the left wing with three corps to prevent the juncture of the two enemy forces by capturing the crossroads at Quatre Bras – where the north–south Brussels–Charleroi highway crosses the vital east–west Namur–Nivelles road that was the principal lateral link between Blücher and Wellington – while Grouchy was on the right wing with his corps, and Napoleon stayed in the centre with the Imperial Guard and another corps.61 Later that day, as Ney engaged first the Prince of Orange and then Wellington himself at Quatre Bras, Napoleon and Grouchy attacked Blücher at Ligny. ‘You must go towards that steeple,’ he told Gérard, ‘and drive the Prussians in as far as you can. I will support you. Grouchy has my orders.’62 While these mission-defined orders might sound somewhat casual, a general of Gérard’s enormous experience knew what was expected of him. Napoleon meanwhile ordered an army corps of 20,000 men under General d’Erlon, which an order from Soult had earlier detached from Ney’s command on its way to Quatre Bras, to fall on the exposed Prussian right flank at Ligny.

Had d’Erlon arrived as arranged, Napoleon’s respectable victory at Ligny would have turned into a devastating rout, but instead, just as he was about to engage, he received urgent, imperative orders from Ney that he was needed at Quatre Bras, so he turned around and marched to that battlefield.63 Before he got there and was able to make a contribution, Soult ordered him to turn round and return to Ligny, where his exhausted corps arrived too late to take part in that battle also. This confusion between Ney, Soult and d’Erlon robbed Napoleon of a decisive victory at Ligny, where Blücher lost around 17,000 casualties to Napoleon’s 11,000 and the Prussians were driven from the field by nightfall.64 Ney meanwhile lost over 4,000 men and failed to capture Quatre Bras.

‘It may happen to me to lose battles,’ Napoleon had told the Piedmontese envoys back in 1796, ‘but no one shall ever see me lose minutes either by over-confidence or by sloth.’65 With the Prussians seemingly retreating along their supply lines eastwards towards Liège, he could have fallen upon Wellington’s force at first light on Saturday, June 17. But instead he did not rise until 8 a.m. and then wasted the next five hours reading reports from Paris, visiting the Ligny battlefield, giving directions for the care of the wounded, addressing captured Prussian officers on their country’s foreign policy and talking to his own generals ‘with his accustomed ease’ on various political topics.66 Only at noon did he send Grouchy off with a huge corps of 33,000 men and 96 guns to follow the Prussian army, thereby splitting his force the day before he anticipated a major battle against Wellington, rather than concentrating it.67 ‘Now then, Grouchy, follow up those Prussians,’ Napoleon said, ‘give them a touch of cold steel in their kidneys, but be sure to keep in communication with me by your left flank.’68 But in sending Grouchy off, he was ignoring one of his own military maxims: ‘No force should be detached on the eve of battle, because affairs may change during the night, either by the retreat of the enemy, or the arrival of large reinforcements which might enable him to resume the offensive, and render your previous dispositions disastrous.’69

Although visiting Ligny gave him an idea of the Prussian order of battle and of which enemy corps had been most damaged, this intelligence could never compensate for letting the Prussian army escape – which it might not have done if he had sent Grouchy off on the 16th, or very early on the 17th. Soult had sent Pajol on a reconnaissance towards Namur, where he had captured some guns and prisoners, leading Napoleon further towards the theory that most of the Prussian army was retreating in disarray on its supply lines.70 Various comments he made that day and subsequently suggest that Napoleon thought he had so shattered the Prussians at Ligny that they could play no further significant part in the campaign. No reconnaissance was therefore sent northwards.

The Prussians had a fifteen-hour head-start on Grouchy, who didn’t know in which direction they had gone. Blücher had been concussed during the battle, and his chief-of-staff, General August von Gneisenau, had ordered a retreat to the north, to stay close to Wellington’s army, rather than east. This counter-intuitive move was to be described by Wellington as the most important decision of the nineteenth century. As he fought and refought the battle in his mind over the next half-decade, Napoleon blamed many factors for his defeat, but he acknowledged that either he should have given the job of staving off the Prussians to the more vigorous Vandamme or Suchet, or he should have left it to Pajol with a single division. ‘I ought to have taken all the other troops with me,’ he ruefully concluded.71

Only later on June 17 did Napoleon move off at a leisurely pace towards Quatre Bras, arriving at 1 p.m. to join Ney. By that time Wellington had learned what had happened at Ligny and was prudently retreating north himself in the pouring rain, with plenty of time to take up position on the ridge of Mont Saint-Jean. This was a few miles south of his headquarters at the village of Waterloo, in an area he had previously reconnoitred and whose myriad defensive advantages as a battlefield – only 3 miles wide with plenty of ‘hidden’ ground and two large stone farmhouses called Hougoumont and La Haie Sainte out in front of a ridge – he had already spotted. ‘It is an approved maxim in war never to do what the enemy wishes you to do’, was another of Napoleon’s sayings, ‘for this reason alone, because he wishes it. A field of battle, therefore, which he has previously studied and reconnoitred should be avoided.’72 Not committing the Guard at Borodino, staying too long in Moscow and Leipzig, splitting his forces in the Leipzig and Waterloo campaigns and, finally, coming to the decisive engagement on ground which his opponent had chosen: all were the result of Napoleon not following his own military maxims.

• • •

Napoleon spent some of June 17 visiting battalions that had distinguished themselves at Ligny, and admonishing those that had not. He recognized Colonel Odoards of the 22nd Line, who used to be in his Guard, and asked him how many men he had on parade (1,830), how many they had lost the day before (220), and what was being done with abandoned Prussian muskets.73 When Odoards told him they were being destroyed, Napoleon said they were needed by the National Guard and offered 3 francs for every one collected. Otherwise the morning of the 17th was characterized by an entirely unaccustomed torpor.

Claims were made decades after the campaign by Jérôme and Larrey that Napoleon’s lethargy was the result of his suffering from haemorrhoids which incapacitated him after Ligny.74 ‘My brother, I hear that you suffer from piles,’ Napoleon had written to Jérôme in May 1807. ‘The simplest way to get rid of them is to apply three or four leeches. Since I used this remedy ten years ago, I haven’t been tormented again.’75 But was he in fact tormented? This might be the reason why he spent hardly any time on horseback during the battle of Waterloo – visiting the Grand Battery once at 3 p.m. and riding along the battlefront at 6 p.m. – and why he twice retired to a farmhouse at Rossomme about 1,500 yards behind the lines for short periods.76 He swore at his page, Gudin, for swinging him on to his saddle too violently at Le Caillou in the morning, later apologizing, saying: ‘When you help a man to mount, it’s best done gently.’77 General Auguste Pétiet, who was on Soult’s staff at Waterloo, recalled that

His pot-belly was unusually pronounced for a man of forty-five. Furthermore, it was noticeable during this campaign that he remained on horseback much less than in the past. When he dismounted, either to study maps or else to send messages and receive reports, members of his staff would set before him a small deal table and a rough chair made of the same wood, and on this he would remain seated for long periods at a time.78

A bladder infection has also been diagnosed by historians, although Napoleon’s valet Marchand denied that his master suffered from one during this period, as has narcolepsy, of which there is no persuasive evidence either. ‘At no point in his life did the Emperor display more energy, more authority, or greater capacity as a leader of men,’ recalled one of his closest aides-de-camp, Flahaut.79 But by 1815 Napoleon was nearly forty-six, overweight, and didn’t have the raw energy of his mid-twenties. By June 18 he also had had only one proper night’s sleep in six days. Flahaut’s explanation for Napoleon’s inaction was simply that ‘After a pitched battle, and marches such as we had made on the previous day, our army could not be expected to start off again at dawn.’80Yet such considerations had not prevented Napoleon from fighting four battles in five days the previous year.

There is in fact no convincing evidence that any of the decisions Napoleon took on June 18 were the result of his physical state rather than his own misjudgements and the faulty intelligence he received. ‘In war,’ he told one of his captors the following year, ‘the game is always with him who commits the fewest faults.’81 In the Waterloo campaign that was Wellington, who had made a study of Napoleon’s tactics and career, was rigorous in his deployments, and was everywhere on the battlefield. Napoleon, Soult and Ney, by contrast, fought one of the worst-commanded battles of the Napoleonic Wars. The best battlefield soldier Napoleon had fought before Waterloo had been Archduke Charles, and he was simply not prepared for a master-tactician of Wellington’s calibre – one, moreover, who had never lost a battle.

• • •

When Napoleon met d’Erlon at Quatre Bras on the 17th he said either ‘You have dealt a blow to the cause of France, general’, or, as d’Erlon himself preferred to recall it, ‘France has been lost; my dear general, put yourself at the head of the cavalry and push the English rearguard as hard as possible.’82 That evening Napoleon seems to have come close to the fighting between the British cavalry rearguard, slowing the pursuit in the heavy rain, and the French vanguard thrusting them northwards towards the ridge of Mont Saint-Jean, though he didn’t take part in a cavalry charge, as d’Erlon claimed in his memoirs.83 He did have time to stop for the wounded Captain Elphinstone of the 7th Hussars, however, to whom he gave a drink of wine from his own hipflask and for whom he got the attention of a doctor.84 Napoleon was perfectly capable of kindness to individual Britons while detesting their government.

At around 7 p.m., Napoleon called off the attack on the Anglo-Allied rearguard, as d’Erlon had been urging him to, and said: ‘Have the troops make soup and get their arms in good order. We will see what midday brings.’85 That night he visited the outposts, telling his men to rest well, for ‘If the English army remains here tomorrow, it is mine.’86 He chose Le Caillou farmhouse as his headquarters that night, sleeping on his camp bed on the ground floor while Soult slept on straw on the floor above. (He hadn’t wanted to go the extra 3 miles back to the town of Genappes as he knew he would be receiving reports.) Corbineau, La Bédoyère, Flahaut and his other aides-de-camp spent the night riding between the various corps in the rain, recording movements and positions.

‘Mamluk Ali’, Napoleon’s French bodyguard, recalled him lying on a bundle of straw till his room was made ready. ‘When he had taken possession . . . he had his boots taken off, and we had trouble in doing it, as they had been wet all day, and after undressing he went to bed. That night he slept little, being disturbed every minute by people coming and going; one came to report, another to receive orders, etc.’87 At least he was dry. ‘Our greatcoats and trousers were caked with several pounds of mud,’ Sergeant Hippolyte de Mauduit of the 1st Grenadiers à Pied recalled. ‘A great many of the soldiers had lost their shoes and reached their bivouac barefoot.’88 Never had Napoleon’s obsession with shoes been more vindicated.

Napoleon later told Las Cases that he reconnoitred with Bertrand at 1 a.m. to check that Wellington’s army was still there, which (despite there being no corroboration of it) he might have done. He was woken at 2 a.m. to receive a message from Grouchy, written four hours earlier, in which he reported being in contact with the Prussians near Wavre. Grouchy thought it might be the main Prussian force, whereas in fact it was only Blücher’s rearguard. Napoleon didn’t reply for another ten hours, despite knowing by then that Wellington was going to defend Mont Saint-Jean later that morning. It was an extraordinary error not to have brought Grouchy back to the battlefield immediately, to fall on Wellington’s left flank.

‘Ah! Mon Dieu!’ Napoleon told General Gourgaud the next year, ‘perhaps the rain on the seventeenth of June had more to do than is supposed with the loss of Waterloo. If I had not been so weary, I should have been on horseback all night. Events that seem very small often have very great results.’89 He felt strongly that his thorough reconnoitring of battlefields such as Eggmühl had led to victory, but the real significance of the rain was that his artillery commander, General Drouot, suggested waiting for the ground to dry before starting the battle the next day, so that he could get his guns into place more easily and the cannonballs would bounce further when fired. It was advice Drouot was to regret for the rest of his life, for neither he nor the Emperor knew that, having eluded Grouchy, Blücher had reiterated his promise to Wellington that same morning that at least three Prussian corps would arrive on the battlefield that afternoon. Indeed, Wellington decided to fight there only on the understanding that this would happen.

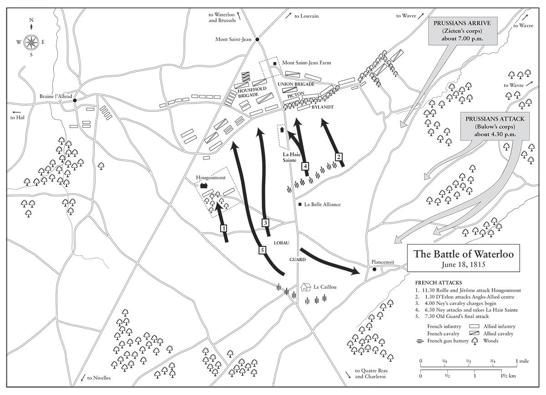

Had Napoleon started his attack at sunrise, 3.48 a.m. on Sunday, June 18, instead of after 11 a.m., he would have had more than seven extra hours to break Wellington’s line before Bülow’s corps erupted onto his right flank.90* Although Napoleon ordered Ney to have the men properly fed and their equipment checked ‘so that at nine o’clock precisely each of them is ready and there can be a battle’, it was to be another two hours before the fighting started.91 By then Napoleon had held a breakfast conference of senior officers in the dining room next to his bedroom at Le Caillou. When several of the generals who had fought Wellington in Spain, such as Soult, Reille and Foy, suggested that he should not rely on being able to break through the British infantry with ease, Napoleon replied, ‘Because you’ve been beaten by Wellington you consider him to be a good general. I say that he’s a bad general and that the English are bad troops. It will be a lunchtime affair!’ A clearly unconvinced Soult could only say, ‘I hope so!’92 These seemingly hubristic remarks completely contradicted his real and oft-stated views about Wellington and the British, and must be ascribed to his need to encourage his lieutenants just hours away from a major battle.

At the breakfast conference, Jérôme told Napoleon that the waiter at the King of Spain inn at Genappes where Wellington had dined on June 16 had overheard an aide-de-camp saying that the Prussians would join them in front of the Forest of Soignes, which was directly behind Mont Saint-Jean. In response to this (ultimately devastatingly accurate) information, Napoleon said, ‘The Prussians and the English cannot possibly link up for another two days after such a battle as Fleurus [that is, Ligny], and given the fact that they are being pursued by a considerable body of troops.’ He then added, ‘The battle that is coming will save France and will be celebrated in the annals of the world. I shall have my artillery fire and my cavalry charge, so as to force the enemy to disclose his positions, and when I am quite certain which positions the English troops have taken up, I shall march straight at them with my Old Guard.’93 Napoleon could be forgiven for not altering his entire strategy on the basis of a waiter’s report of the conversation of an over-loquacious aide-de-camp, but even his own explanation of the tactics he was about to adopt betrays their total lack of sophistication. Wellington expected Napoleon to adopt a wide flanking manoeuvre of the French left – and deployed 17,500 men at Hal to guard against it – but his plan turned out to be no more imaginative than those he had employed at Eylau, Borodino or Lâon.

At 9.30 a.m. Napoleon left Le Caillou, in his orderly Jardin Ainé’s recollection, ‘to take up his stand half a league in advance on a hill where he could discern the movements of the British army. There he dismounted, and with his field-glass endeavoured to discover all the movements in the enemy’s line.’94 He chose a small knoll near the La Belle Alliance inn, where he spread his maps on the table while his horses stood saddled nearby.95 ‘I saw him through my glass,’ recalled Foy, ‘walking up and down, wearing his grey overcoat, and frequently leaning over the little table on which his map was placed.’96 The night’s rain had given way to a cloudy but dry day. Soult suggested an early attack, but Napoleon replied that they ‘must wait’, almost certainly to allow the Grand Battery to negotiate the mud more easily. Colonel Comte de Turenne and Monthion recalled Napoleon’s tiredness in the two hours before the battle started; the Emperor ‘remained a long time seated before a table . . . and . . . they frequently saw his head, overcome by sleep, sink down upon the map spread out before his heavy eyes’.97

Napoleon wrote to Grouchy at noon and again at 1 p.m. ordering him to rejoin him immediately. But by then it was too late.98 (One of his messages didn’t even reach Grouchy until 6 p.m.) Napoleon later claimed that he had commanded Grouchy to return earlier, but no such order has been found and Grouchy vociferously denied it.99 A bulging file in the war ministry archives at Vincennes bears witness to the controversy between Grouchy and Gérard as to whether, without Napoleon’s direct orders, Grouchy ought in any case to have marched towards the sound of the Grand Battery when it opened up in the late morning, rather than pressing on to engage the Prussian rearguard at Wavre.100

• • •

In the Peninsular War, Wellington had conducted several defensive battles, including Vimeiro in 1808, Talavera in 1809 and Bussaco in 1810, and was confident of holding his ground. A tough, no-nonsense Anglo-Irish aristocrat and stern, unbending Tory, he admired Napoleon as ‘the first man of the day on a field of battle’ but otherwise despised him as a political upstart. ‘His policy was mere bullying,’ Wellington said after Waterloo, ‘and, military matters apart, he was a Jonathan Wild.’ (Wild was a notorious criminal hanged at Tyburn in 1725.)101 Wellington’s choice of ground, with his right flank protected by Hougoumont, his left by a forest, and his centre on a lateral sunken road a few hundred yards behind the fortified La Haie Sainte, severely limited Napoleon’s tactical options.* But with the Forest of Soignes behind him, Wellington took a tremendous risk in choosing this ground. If Napoleon had forced him back from the road, an orderly retreat would have been impossible.

The battle of Waterloo started around 11 a.m. with the guns of Reille’s corps preparing the way for the diversionary attack on Hougoumont by Jérôme’s division, followed by Foy’s. The attack on the farmhouse failed, and was to draw in more and more French troops as the day progressed. For some unknown reason they did not try to smash in the farmhouse’s front gates with horse artillery. Wellington reinforced it during the day and Hougoumont, like La Haie Sainte, became an invaluable breakwater that disrupted and funnelled the French advances. Jérôme fought bravely, and when his division was reduced to a mere two battalions Napoleon summoned him and said: ‘My brother, I regret to have known you so late.’102 This, Jérôme later recalled, was balm to the ‘many repressed pains in his heart’.

At 1 p.m. an initial bombardment by Napoleon’s eighty-three-gun Grand Battery against Wellington’s line did less damage than it might have due to Wellington’s orders that his men lie down behind the brow of the ridge. Napoleon unleashed his major infantry attack at 1.30 p.m. when d’Erlon’s corps assaulted Wellington’s centre-left through muddy fields of breast-high rye, marching past La Haie Sainte on their left in the hope of smashing through and then rolling up each side of Wellington’s line, rather as they had the Austro-Russians at Austerlitz. It was the correct place to attack, the weakest part of Wellington’s position, but the execution was faulty.

D’Erlon launched his entire corps with all the battalions deployed in several lines 250 men wide at the start of his assault, presumably to increase the firepower on contact with the enemy, but violating all the established French models of manoeuvring in column before deploying into line. This left the whole formation unwieldy, difficult to control and extremely vulnerable. Captain Pierre Duthilt of General de Marcognet’s division recalled that it was ‘a strange formation and one which was to cost us dear, since we were unable to form square as a defence against cavalry attacks, while the enemy’s artillery could plough our formations to a depth of twenty ranks’.103 No one knew whose idea this formation was, but ultimately d’Erlon must be responsible for so important a tactical decision as the formation in which his corps launched the vital front-fixing assault.* Another of Napoleon’s maxims was that ‘Infantry, cavalry and artillery are nothing without each other’, but on this occasion d’Erlon’s infantry attack was inadequately protected by the other arms, and was repulsed having failed to fix Wellington’s front in place.104 Instead the Union and Household brigades of British cavalry charged the corps and sent it fleeing back to the French lines with the loss of two eagles out of twelve. At 3 p.m., once the British cavalry had been driven away from the Grand Battery in the wake of d’Erlon’s retreat, Napoleon joined General Jean-Jacques Desvaux de Saint-Maurice, commander of the Guard artillery, for a closer look at the battlefield. With the Emperor riding beside him, Desvaux was cut in half by a cannonball.105

At about 1.30 p.m. the first of three Prussian corps started to appear on Napoleon’s right flank. He had been warned that this might happen by a Prussian hussar who had been captured by a squadron of French chasseurs between Wavre and Plancenoit, and had been moving men off to the right flank for the better part of half an hour. He now ordered that the army be told the dark-coated bodies of men on the horizon were Grouchy’s corps arriving to win the battle. As time wore on this falsehood was gradually revealed, with a corresponding drop in morale. During the afternoon Napoleon was forced to divert steadily increasing numbers to his right flank to confront the Prussians, and by 4 p.m. Bülow’s 30,000 Prussians were attacking Lobau’s 7,000 French infantry and cavalry between Frischermont and Plancenoit.106 The advantage that Napoleon had enjoyed in the morning of 72,000 men and 236 guns over Wellington’s 68,000 men and 136 guns was turned into a significant disadvantage once the Allies could together deploy over 100,000 men and more than 200 guns.

A series of massive cavalry charges totalling 10,000 men, the largest since Murat’s charge at Eylau, was launched under Ney against Wellington’s centre-right at around 4 p.m., although it is still unclear quite who – if anyone – had ordered it, since both Napoleon and Ney denied it afterwards.107 ‘There is Ney hazarding the battle which was almost won,’ Napoleon told Flahaut when he saw what was happening, ‘but he must be supported now, for that is our only chance.’108 Despite thinking the charge ‘premature and ill-timed’, Napoleon told Flahaut to ‘order all the cavalry [he] could find to assist the troops which Ney had thrown at the enemy across the ravine’.109 (Today one can see at the Gordon Monument how deep the road was, but it is no ravine.) ‘In war there are sometimes mistakes which can only be repaired by persevering in the same line of action,’ Flahaut later said philosophically.110 Unfortunately for Napoleon, this was not one of them.

Wellington’s infantry now formed thirteen hollow squares (in fact they were rectangular in shape) to receive the cavalry. A horse’s natural unwillingness to charge into a wall of bristling bayonets made them near-impregnable to cavalry, though Ney had broken the squares of the 42nd and 69th Foot at Quatre Bras and French cavalry had broken squares of Russians at Hof in 1807 and of Austrians at Dresden in 1813. Squares were particularly vulnerable to artillery and infantry formed in line, but this cavalry attack was unsupported by either, confirming the suspicion that it had started as an accident rather than from a deliberate order by Napoleon or Ney. Not one of the thirteen squares broke. ‘It was the good discipline of the English that gained the day,’ Napoleon conceded on St Helena, after which he blamed General Guyot, who commanded the Heavy Cavalry, for charging without orders. This was unfounded as Guyot only rode in the second wave.111

The mystery of the battle of Waterloo is why a collection of fine and experienced French combat generals of all three arms repeatedly failed to co-ordinate their efforts, as they had done successfully on so many previous battlefields.* This was particularly true of Napoleon’s favourite arm, the artillery, which consistently missed giving close support to the infantry at various important stages throughout the battle. With much of the French cavalry exhausted, its horses blown, and the Prussians arriving in force after 4.15 p.m., Napoleon would have been wise to withdraw as best he could.112 Instead, sometime after 6 p.m., Ney succeeded in capturing La Haie Sainte and the nearby excavation area known as the Sandpit in the centre of the battlefield, and brought up a battery of horse artillery at 300 yards’ range, allowing him to pound Wellington’s centre with musketry and cannon, to the extent that the 27th Inniskilling Regiment of Foot, formed in square, took 90 per cent casualties. This was the crisis point of the battle, the best chance the French had of breaking through before the sheer weight of Prussian numbers crushed them. Yet when Ney sent his aide-de-camp Octave Levasseur to beg Napoleon for more troops to exploit the situation, the Emperor, his cavalry exhausted and his own headquarters now within range of Prussian artillery, refused. ‘Troops?’ he said sarcastically to Levasseur. ‘Where would you like me to find them? Would you like me to make them?’113 In fact at that point he had fourteen unused Guards battalions. By the time he had changed his mind half an hour later, Wellington had plugged the dangerous gaps in his centre with Brunswickers, Hanoverians and a Dutch–Belgian division.

It wasn’t until around 7 p.m., once he had ridden right along the battlefront, that Napoleon sent the Middle Guard up the main road towards Brussels in a column of squares. The Imperial Guard’s attack in the latter stages of Waterloo was undertaken by only about one-third of its total battlefield strength, the rest being used either to recover Plancenoit from the Prussians or to cover the retreat. Napoleon ordered Ney to support it, but when the Guard was brought up, one infantry division had not been drawn out of the wood of Hougoumont, nor had a cavalry brigade been called over from the Nivelles road.114 So the Guard ascended the slope towards Wellington’s line, now well-defended once more, without a regiment of cavalry protecting its flanks and with only a few troops from Reille’s corps in support. Only twelve guns took part in the attack, out of the total of ninety-six available to the Guard artillery.

The forlorn nature of this attack might be judged from the fact that the Guard took no eagles with it, although 150 bandsmen marched at its head, playing triumphant parade-ground marches.115 Napoleon placed himself in the dead ground south-west of La Haie Sainte, at the foot of the long slope heading up towards the ridge, as the Guard marched past him cheering ‘Vive l’Empereur!’116 They started off with eight battalions, probably fewer than 4,000 men in all, escorted by some horse artillery, but dropped off three battalions along the way as a reserve. The harder ground was better for Wellington’s artillery and soon, as Levasseur recalled, ‘Bullets and grapeshot left the road strewn with dead and wounded.’ The sheer concentration of firepower – both musketry and grapeshot – that Wellington was able to bring to bear broke the will of the Imperial Guard, and it fell back, demoralized. The cry ‘La Garde recule!’ had not been heard on any battlefield since its formation as the Consular Guard in 1799. It was the signal for a general disintegration of the French army across the entire front. Although Ney was to deny having heard it when he made a speech about Waterloo in the Chamber of Peers a few days later, the cry ‘Sauve qui peut!’ went up at about 8 p.m., as men threw down their muskets and tried to escape before darkness fell. When it was clear what was happening, Napoleon took an unnamed general by the arm and said: ‘Come, general, the affair is over – we have lost the day – let us be off.’117

Two squares of the Old Guard on either side of the Charleroi–Brussels road covered the army’s pell-mell retreat. General Petit commanded the square of the 1st Battalion of the 1st Grenadiers à Pied some 300 yards south of La Belle Alliance, among which Napoleon took refuge.* ‘The whole army was in the most appalling disorder,’ Petit recalled. ‘Infantry, cavalry, artillery – everybody was fleeing in all directions.’ As the square retreated steadily, the Emperor ordered Petit to sound the stirring drumroll known as thegrenadière to rally guardsmen ‘caught up in the torrent of fugitives. The enemy was close at our heels, and, fearing that he might penetrate the squares, we were obliged to fire at the men who were being pursued . . . It was now almost dark.’118

Somewhere beyond Rossomme, Napoleon, Flahaut, Corbineau, Napoleon’s orderly Jardin Ainé, some officers and the duty squadron of Chasseurs à Cheval left the square to ride down the main road. Napoleon transferred into his carriage at Le Caillou but he found the road at Genappes completely blocked by fleeing soldiers. Abandoning the carriage he mounted his horse for the flight through Quatre Bras and Charleroi.* Flahaut recalled that, as they rode off towards Charleroi, they were unable to go at much more than walking pace because of the sheer crush. ‘Of personal fear there was not the slightest trace, although the state of affairs was such as to cause him the greatest uneasiness,’ he wrote of Napoleon. ‘He was, however, so overcome by fatigue and the exertion of the preceding days that several times he was unable to resist the sleepiness which overcame him, and if I had not been there to uphold him, he would have fallen from his horse.’119 Getting beyond Charleroi after 5 a.m., Ainé recorded that the Emperor ‘found in a little meadow on the right a small fire made by some soldiers. He stopped by it to warm himself and said to General Corbineau: “Eh bien monsieur, we have done a fine thing.”’ Even then, Napoleon was able to make a joke, however grim. Ainé remembered that Napoleon ‘was at this time extremely pale and haggard and much changed. He took a small glass of wine and a morsel of bread which one of his equerries had in his pocket, and some moments later mounted, asking if the horse galloped well.’120

• • •

Waterloo was the second costliest single-day battle of the Napoleonic Wars after Borodino. Between 25,000 and 31,000 Frenchmen were killed or wounded, and huge numbers captured.121 Wellington lost 17,200 men and Blücher a further 7,000. Of Napoleon’s sixty-four most senior generals who served in 1815, twenty-six were killed or wounded that year. ‘Incomprehensible day,’ Napoleon later said of Waterloo. He admitted that ‘he did not thoroughly understand the battle’, the loss of which he blamed on ‘a combination of extraordinary Fates’.122 Yet the genuinely incomprehensible thing was quite how many unforced errors he and his senior commanders had made. With his torpor the day before the battle, his strategic error over Grouchy, his failure to co-ordinate attacks and his refusal to grasp his last, best opportunity after La Haie Sainte fell, Napoleon’s performance after Ligny recalled those of his more ponderous Austrian enemies in the Italian campaigns nearly twenty years earlier. Not only did Wellington and Blücher deserve to win the battle of Waterloo: Napoleon very much deserved to lose it.