29

‘I conclude my work with the year 1815, because everything which came after that belongs to ordinary history.’

Metternich, Memoirs

‘True heroism consists of being superior to the ills of life, in whatever shape they may challenge to the combat.’

Napoleon on board HMS Northumberland, 1815

Once it became clear that Ney, Macdonald, Lefebvre and Oudinot had no stomach for a civil war, and the Allies had informed Caulaincourt on April 5 that they would give Napoleon the lifetime sovereignty of the Mediterranean island of Elba off Italy, the Emperor signed a provisional abdication document at Fontainebleau for Caulaincourt to use in his negotiations.1 ‘You wish for repose,’ he told the marshals. ‘Well then, you shall have it.’2 The abdication was only for himself and not for his heirs, and he intended Caulaincourt to keep it secret as he would ratify it only once a treaty – covering Elba and granting financial and personal security for Napoleon and his family – was signed. Yet of course the news quickly leaked out, and the palace emptied as officers and courtiers left to make their peace with the provisional government. ‘One would have thought,’ said State Councillor Joseph Pelet de la Lozère of the exodus, ‘that His Majesty was already in his grave.’3 By April 7 the Moniteur didn’t have enough space in its columns to print all the proclamations of loyalty to Louis XVIII that had been made by Jourdan, Augereau, Maison, Lagrange, Nansouty, Oudinot, Kellermann, Lefebvre, Hullin, Milhaud, Ségur, Latour-Maubourg and others.4 Berthier was even appointed to command one of Louis XVIII’s corps of Guards.5 ‘His Majesty was very sad and hardly talking,’ Roustam recorded of these days.6 After his stay at the Jelgava Palace in Latvia, where he had written to Napoleon asking for his throne back in 1800, Louis XVIII had moved to Hartwell House in Buckinghamshire, England, in 1807, from where he now prepared to move back to France in order to reclaim his throne, as soon as he received the news that Napoleon had abdicated.

Yet even denuded of an officer corps and general staff, Napoleon could still have precipitated a civil war had he wished. On April 7 rumours of his abdication prompted the 40,000-strong army at Fontainebleau to leave their billets at night and parade with arms and torches crying ‘Vive l’Empereur!’, ‘Down with the traitors!’ and ‘To Paris!’7 There were similar scenes at the barracks in Orleans, Briaire, Lyons, Douai, Thionville and Landau, and the white flag of the Bourbons was publicly burned in Clermont-Ferrand and other places. Augereau’s corps was close to mutiny, and garrisons loyal to Napoleon attempted risings in Antwerp, Metz and Mainz. In Lille the troops were in open revolt for three days, actually firing on their officers as late as April 14.8 As Charles de Gaulle was to observe: ‘Those he made suffer most, the soldiers, were the very ones who were most faithful to him.’9 Struck by these protestations of loyalty, the British foreign secretary, Lord Castlereagh, warned the secretary for war, Lord Bathurst, of ‘the danger of Napoleon’s remaining at Fontainebleau surrounded by troops who still, in a considerable degree, remain faithful to him’. This warning finally prompted the Allies to sign the Treaty of Fontainebleau, after five days of negotiation, on April 11, 1814.10

Caulaincourt and Macdonald arrived there from Paris with the treaty the next day, which now only required Napoleon’s signature for its ratification. He invited them to dinner, noting the absence of Ney, who had stayed in the capital to make his peace with the Bourbons.11 The treaty allowed Napoleon to use his imperial title and gave him Elba for life, making generous financial provisions for the whole family, although Josephine’s outrageously generous alimony was cut to 1 million francs per annum. Napoleon himself was to receive 2.5 million francs per annum and Marie Louise was given the Italian duchies of Parma, Piacenza and Guastalla.12 Napoleon wrote to her on April 13, saying: ‘You are to have at least one mansion and a beautiful country . . . when you tire of my Island of Elba and I begin to bore you, as I can but do when I am older and you still young.’ He added: ‘My health is good, my courage unimpaired, especially if you will be content with my ill-fortune and if you think you can still be happy in sharing it.’13He had not yet appreciated that the rationale for a Habsburg marrying a Bonaparte had been that he was Emperor of France; now that he was to be merely Emperor of Elba the desirability of the match collapsed. Getting hold of a book on the island he told Bausset, ‘The air there is healthy and the inhabitants are excellent. I shall not be very badly off, and I hope that Marie Louise will not be very unhappy either.’14 Yet only two hours before General Pierre Cambronne and a cavalry detachment arrived at Orleans on April 12 with orders from Napoleon to take her and the King of Rome the 54 miles to Fontainebleau, an Austrian delegation from Metternich took her and her retinue away to the chateau of Rambouillet, where she was told that her father would join her. At first she insisted that she could only leave with Napoleon’s permission, but she was persuaded to change her mind easily enough, although she wrote to Napoleon that she was being taken against her will. It was not long before she gave up any plans she might have had to rejoin him, and went instead to Vienna. She had no intention of being not very unhappy.

For all his optimism in his letter to Marie Louise, on the night between the 12th and 13th, after dinner with Caulaincourt and Macdonald, Napoleon attempted to commit suicide.15 He took a mixture of poisons ‘the size and shape of a clove of garlic’ that he had carried in a small silk bag around his neck since he was nearly captured by the Cossacks at Maloyaroslavets.16 He did not try any other means of suicide, not least because Roustam and his chamberlain, Henri, Comte de Turenne, had removed his pistols.17 ‘My life no longer belonged to my country,’ was Napoleon’s own later explanation:

the events of the last few days had again rendered me master of it – ‘Why should I endure so much suffering?’ I reflected, ‘and who knows that my death might not place the crown on the head of my son?’ France was saved. I hesitated no longer, but leaping from my bed, mixed the poison in a little water, and drank it with a sort of feeling of happiness. But time had taken away its strength; fearful pains drew forth some groans from me; they were heard, and medical assistance arrived.18

His valet Hubert, who slept in the adjoining room, heard him groaning, and summoned Yvan the doctor, who induced vomiting, possibly by forcing him to swallow ashes from the fireplace.19

Maret and Caulaincourt were also called during the night. Once it was clear that he wasn’t going to die, Napoleon signed the abdication the next morning ‘without further hesitation’ on a plain pedestal table in the red and gold antechamber now known as the Abdication Room. ‘The Allied powers having declared that the Emperor Napoleon was the only obstacle to the re-establishment of peace in Europe,’ it stated, ‘the Emperor Napoleon, faithful to his oath, declares that he renounces, for himself and his heirs, the thrones of France and Italy, and there is no personal sacrifice, even that of life, that he would not be ready to make in the interest of France.’20

When Macdonald went to the Emperor’s apartments to collect the ratified treaty at 9 a.m. on April 13, Caulaincourt and Maret were still there. Macdonald found Napoleon ‘seated before the fire, clothed in a simple dimity [lightweight cotton] dressing-gown, his legs bare, his feet in slippers, his head resting in his hands, and his elbows resting on his knees . . . his complexion was yellow and greenish.’21 He merely said he had been ‘very ill all night’. Napoleon was fulsome towards the loyal Macdonald, telling him: ‘I did not know you well; I was prejudiced against you. I have done so much for, and loaded with favours, so many others who have abandoned and neglected me; and you, who owe me nothing, have remained faithful to me!’22 He gave him Murad Bey’s sword, they embraced, and Macdonald left to take the ratified treaty to Paris. They never saw each other again.

After the attempted suicide, Roustam fled Fontainebleau, later saying he feared that he might be mistaken for a Bourbon or Allied assassin if Napoleon succeeded in killing himself.23

• • •

On April 15 it was decided that generals Bertrand, Drouot and Pierre Cambronne would accompany Napoleon to Elba, with a small force of six hundred Imperial Guardsmen, the Allies having promised to protect the island from ‘the Barbary Powers’ – that is the North African states – under a special article of the treaty. (Barbary pirates were rife in that part of the Mediterranean.) The next day four Allied commissioners arrived at Fontainebleau to accompany him there, although only the British commissioner, Colonel Sir Neil Campbell, and the Austrian, General Franz von Koller, would actually be living on the island. Napoleon got on well with Campbell, who had been wounded at Fère-Champenoise when a Russian, mistaking him for a French officer, lanced him in the back while another sabred him across the head, even though he had called out lustily, ‘Angliski polkovnik!’ (English colonel). To his delight he was ordered by Castlereagh ‘to attend the late chief of the French Government to the island of Elba’ (a wording that indicates the uncertainty that already prevailed over Napoleon’s exact status).24

Napoleon read the Parisian newspapers at Fontainebleau. Fain recalled that their abuse ‘made but slight impression upon him, and when the hatred was carried to a point of absurdity it only forced from him a smile of pity’.25 He told Flahaut that he was pleased not to have agreed to the Châtillon peace terms in February: ‘I should have been a sadder man than I am if I had to sign a treaty taking from France one single village which was hers on the day when I swore to maintain her integrity.’26 This refusal to renege on one iota of la Gloire de la France was to be a key factor in his return to power. For the present, Napoleon told his valet Constant: ‘Ah well, my son, prepare your cart; we will go and plant our cabbages.’27 The inconstant Constant had no such intention, however, and after twelve years’ service he absconded on the night of April 19 with 5,000 francs in cash. (Savary had orders to hide 70,000 francs for Napoleon – a good deal more than the Banque de France’s governor’s annual salary.28)

Meeting Napoleon on the 17th, Campbell, who spoke French well, wrote in his diary:

I saw before me a short active-looking man, who was rapidly pacing the length of his apartment, like some wild animal in his cell. He was dressed in an old green uniform with gold epaulets, blue pantaloons, and red top-boots, unshaven, uncombed, with the fallen particles of snuff scattered profusely upon his upper lip and breast. Upon his becoming aware of my presence, he turned quickly towards me, and saluted me with a courteous smile, evidently endeavouring to conceal his anxiety and agitation by an assumed placidity of manner.29

In the quick-fire series of questions that Campbell came to know well, Napoleon asked about his wounds, military career, Russian and British decorations and, on discovering that Campbell was a Scot, the poet Ossian. They then discussed various Peninsular War sieges, as Napoleon spoke in complimentary terms about British generalship. He inquired ‘anxiously’ about the tragically unnecessary battle of Toulouse, which had been fought between Wellington and Soult with more than 3,000 casualties each side on April 10, and ‘passed high encomiums’ on Wellington, asking after ‘his age, habits, etc’ and observing, ‘He is a man of energy. To carry on war successfully, one must possess the like quality.’30

‘Yours is the greatest of nations,’ Napoleon told Campbell. ‘I esteem it more than any other. I have been your greatest enemy – frankly such; but am no longer. I have wished likewise to raise the French nation, but my plans have not succeeded. It’s all destiny.’ (Some of this flattery might have stemmed from his desire to sail to Elba in a British man-of-war rather than in the French corvette, Dryade, that he had been allocated, partly perhaps on account of pirates and partly because he may have feared assassination at the hands of a royalist captain and crew.)31 He concluded the interview cordially with the words: ‘Very well, I am at your disposal. I am your subject. I depend entirely on you.’ He then gave a bow ‘free from any assumption of hauteur’.32 It is easy to see why many Britons found Napoleon a surprisingly sympathetic figure. During the negotiations over the treaty, Napoleon had instructed Caulaincourt to inquire as to whether he might come to Britain for his exile, comparing the society of Elba unfavourably with ‘a single street’ of London.33

When on April 18 it was discovered that the new minister of war, none other than the same General Dupont who had surrendered his corps at Bailén in Spain in 1808, had ordered that ‘all the stores belonging to France must be removed’ before Napoleon arrived on Elba, the Emperor refused to leave Fontainebleau on the grounds that the island would be left vulnerable to attack.34 He nonetheless sent off his baggage the next day – though not his treasury of 489,000 francs, which would travel with him – and gave away books, manuscripts, swords, pistols, decorations and coins to his remaining supporters at the palace. He was understandably irritated when he heard about the Tsar’s visit to Marie Louise at Rambouillet, complaining that it was ‘Greek-like’ for conquerors to present themselves before sorrowing wives. (Perhaps he was thinking of the family of Darius received by Alexander the Great.) He also railed against the visit the Tsar had paid to Josephine. ‘Bah! He first breakfasted with Ney, and after that, visited her at Malmaison,’ he said. ‘What can he hope to gain from this?’35

When Berthier’s former aide-de-camp General Charles-Tristan de Montholon visited the palace in mid-April with a (somewhat belated) plan to escape to the upper Loire, he ‘found no one in those vast corridors, formerly too small for the crowd of courtiers, except the Duke of Bassano [Maret], and the aide-de-camp Colonel Victor de Bussy. The whole court, all his personal attendants . . . had forsaken their unfortunate master, and hastened towards Paris.’36 This wasn’t wholly true; still in attendance to the end were generals Bertrand, Gourgaud and Jean-Martin Petit (the commander of the Old Guard), the courtiers Turenne and Megrigny, his private secretary Fain, his interpreter François Lelorgne d’Ideville, his aides-de-camp General Albert Fouler de Relingue, Chevalier Jouanne, Baron de la Place and Louis Atthalin, and two Poles, General Kosakowski and Colonel Vousowitch. Caulaincourt and Flahaut were absent but still loyal.37 Montholon attached himself to Napoleon’s service, and never left it. Although loyalty and gratitude in political adversity are rare, Napoleon still had the capacity to inspire it, even when he had nothing to offer in return. ‘When I left Fontainebleau for Elba I had no great expectation of ever coming back to France,’ he later recalled. All that these last faithful attendants could expect was the animosity of the Bourbons.38 Nor was the spirit of revenge confined to the Bourbons: Count Giuseppe Prina, Napoleon’s finance minister in Italy, was dragged from the Senate in Milan and lynched over four hours by the mob, after which tax documents were stuffed into the corpse’s mouth.

One of the greatest scenes of the Napoleonic epic took place when he left Fontainebleau for Elba at noon on Wednesday, April 20, 1814. The huge White Horse courtyard of the palace – now known as the Cour des Adieux – provided a magnificent backdrop, with its huge double staircase a proscenium, and the Old Guard drawn up in ranks a suitably appreciative and lachrymose audience. (As the courier had not yet arrived from Paris with assurances that Dupont’s malicious order had been rescinded, the commissioners were not even certain Napoleon would actually leave, and were relieved when at 9 a.m. the grand marshal of the palace, General Bertrand, confirmed that he would.) Napoleon first met the Allied commissioners individually in one of the reception rooms upstairs in the palace, speaking angrily to Koller for over half an hour about his continued forced separation from his wife and son. In the course of the conversation ‘tears actually ran down his cheeks’.39 He also asked Koller whether he thought the British government would allow him to live in Britain, allowing the Austrian to make the deserved rejoinder: ‘Yes, Sire, for as you never made war in that country, reconciliation will become the more easy.’40 When Koller later said that the Congress of Prague had provided a ‘very favourable opportunity’ for peace, Napoleon replied, ‘I have been wrong, maybe, in my plans. I have done harm in war. But it is all like a dream.’41

After shaking hands with the soldiers and few remaining courtiers and ‘hastily descending’ the grand staircase, Napoleon ordered the two ranks of grognards to form a circle around him and addressed them in a firm voice, which nonetheless, in the recollection of the Prussian commissioner, Count Friedrich von Truchsess-Waldburg, occasionally faltered with emotion.42 His words recorded by Campbell and several others bear repetition at some length, both because they represent his oratory at this great crisis of his life and because they indicate the lines of argument he was to employ when he later tried to construct the historical narrative of this period:

Officers, non-commissioned officers, and soldiers of the Old Guard, I bid you adieu! For twenty years I have found you ever brave and faithful, marching in the path of glory. All Europe was united against us. The enemy, by stealing three marches upon us, has entered Paris. I was advancing in order to drive them out. They would not have remained there three days. I thank you for the noble spirit you have evinced in that same place under these circumstances. But a portion of the army, not sharing these sentiments, abandoned me and passed over to the camp of the enemy . . . I could with the three parts of the army which remained faithful, and aided by the sympathy and efforts of the great part of the population, have fallen back upon the Loire, or upon my strongholds, and have sustained the war for several years. But a foreign and civil war would have torn the soil of our beautiful country, and at the cost of all these sacrifices and all these ravages, could we hope to vanquish united Europe, supported by the influence which the city of Paris exercised, and which a faction had succeeded in mastering? Under these circumstances I have only considered the interests of the country and the repose of France. I have made the sacrifice of all my rights, and am ready to make that of my person, for the aim of all my life has been the happiness and glory of France. As for you, soldiers, be always faithful in the path of duty and honour. Serve with fidelity your new sovereign. The sweetest occupation will henceforth be to make known to posterity all that you have done that is great . . . You are all my children. I cannot embrace you all so I will do so in the person of your general.43

He then kissed Petit on both cheeks, and declared, ‘I will embrace these eagles, which have served us as guides in so many glorious days’, whereupon he embraced one of the flags three times, for as long as half a minute, before holding up his left hand and saying: ‘Farewell! Preserve me in your memories! Adieu, my children!’ He then got into his carriage and was taken off at a gallop as the Guard band played a trumpet and drum salute entitled ‘Pour l’Empereur’. Needless to say, officers and men wept – as did even some of the foreign officers present – while others were prostrated with grief, and all the others cried ‘Vive l’Empereur!’

By nightfall the convoy of fourteen carriages with a cavalry escort had reached Briare, nearly 70 miles away, where Napoleon slept in the post-house. ‘Adieu, chère Louise,’ he wrote to his wife, ‘love me, think of your best friend and your son.’44 Over the next six nights, Napoleon slept at Nevers, Roanne, Lyons, Donzère, Saint-Cannat and Luc, arriving at Fréjus on the south coast at 10 a.m. on April 27. The 500-mile journey was not without danger in the traditionally pro-royalist Midi, and on different occasions Napoleon had to wear Koller’s uniform, a Russian cloak and even a white Bourbon cockade in his hat to avoid recognition. At Orange his carriage had several large stones thrown through the window; at Avignon the Napoleonic eagles on the carriages were defaced and a servant was threatened with death if he didn’t shout ‘Vive le Roi!’ (A year later, Marshal Brune was shot there by royalist assassins and his body thrown into the Rhône.) On April 23 he met Augereau near Valence. The old marshal, who had been one of Napoleon’s first divisional commanders in Italy in 1796, had removed all his Napoleonic orders except for the red ribbon of the Légion d’Honneur. He now ‘abused Napoleon’s ambition and waste of blood for personal vanity’, telling him bluntly that he ought to have died in battle.45

Campbell had arranged for Captain (later Admiral) Thomas Ussher to pick Napoleon up on the frigate HMS Undaunted at Fréjus. When he arrived there, Napoleon was met by Pauline, who proposed to share his exile. Faithless to her husbands, she nonetheless showed great fidelity to her brother in his downfall. He had wanted to leave France on the morning of the 28th but missed the tide, ate a bad langoustine at lunchtime which induced vomiting, and didn’t sail until 8 p.m. He insisted upon and was given a sovereign’s twenty-one-gun salute when he went aboard, despite the Royal Navy’s convention not to fire salutes after sunset.46 (The Treaty of Fontainebleau had confirmed that he was a reigning monarch and was entitled to the accompanying formalities.) In a poignant echo, he left from precisely the same jetty that he had arrived at when returning from Egypt fifteen years before.47 Although Captain Ussher checked that his sword was loose in its scabbard in case he needed to defend his charge from the crowd, he found instead that Napoleon was cheered as he left, which Ussher found ‘in the highest degree interesting’.48 Throughout the journey, Campbell noted, ‘Napoleon conducted himself with the greatest . . . cordiality towards us all . . . and the officers of his suite observed that they had never seen him more at his ease.’49 Napoleon told Campbell that he believed that the British would force a commercial treaty on the Bourbons, who as a result ‘will be driven out in six months’.50 He asked that they land at Ajaccio, telling Ussher anecdotes of his youth, but Koller begged the captain not to consider it, possibly fearing the havoc Napoleon might wreak if he escaped into the mountains there.51

At 8 p.m. on May 3, Undaunted anchored at Elba’s main harbour of Portoferraio, and Napoleon disembarked at 2 p.m. the next day. When he stepped ashore he was welcomed by the sub-prefect, local clergy and officials carrying the ceremonial keys of the island, but most importantly by cries of ‘Vive l’Empereur!’ and ‘Vive Napoléon!’ from the populace.52 They raised the flag he had designed – white with a bee-studded red band running diagonally across it – over the fort’s battery, and, in an amazing feat of memory, Napoleon recognized a sergeant in the crowd to whom he had given the cross of the Légion on the battlefield of Eylau, who promptly wept.53 After processing to the church for a Te Deum he went to the town hall for a meeting with the island’s principal dignitaries. He stayed in the town hall for the first few days, and then installed himself in the large and comfortable Palazzina dei Mulini overlooking Portoferraio, taking the Villa San Martino, which affords a fine view of the town from its terraces, as a summer residence.* The day after landing he inspected Portoferraio’s fortifications, and the next day its iron mines, which needed to be productive as he would soon be facing a severe cash shortage.

Napoleon’s financial position was not commensurate with what he considered necessary. In addition to the half a million francs he had brought from France himself, his treasurer Peyrusse delivered an extra 2.58 million and Marie Louise had sent 911,000 francs, giving a total of less than 4 million francs.54 Although the Treaty of Fontainebleau theoretically gave him an annual income of 2.5 million francs, the Bourbons never actually remitted him a centime of it. Revenues from Elba totalled 651,995 francs in 1814 and 967,751 in 1815, yet Napoleon’s civil, military and household expenses amounted to over 1.8 million francs in 1814 and nearly 1.5 million in 1815. He therefore had only enough money to cover another twenty-eight months, although with five valets there were obviously some economies he could make. To make matters worse the Bourbons would sequester the Bonaparte family’s goods and properties in December.55

When in 1803 Elba had been ceded to France, Napoleon had written of its ‘mild and industrious population, two superb harbours and a rich mine’, but now that he was its monarch he described its 20,000 acres as a ‘royaume d’opérette’ (operetta kingdom).56Any other sovereign might have relaxed on the charming, temperate, delightful island, especially after the gruelling nature of the previous two years, but such was Napoleon’s nature that he flung himself energetically into every aspect of its life – while always on the lookout for an opportunity to slip past Campbell and return to France should the political situation there favour it. During his nearly ten months on Elba he reorganized his new kingdom’s defences, gave money to the poorest of its 11,400 inhabitants, installed a fountain on the roadside outside Poggio (which still produces cold, clean drinking water today), read voraciously (leaving a library of 1,100 volumes to the municipality of Portoferraio), played with his pet monkey Jénar, walked the coastline along goat-paths while humming Italian arias, grew avenues of mulberry trees (perhaps finally expelling the curse of the pépinière), reformed customs and excise, repaired the barracks, built a hospital, planted vineyards, paved parts of Portoferraio for the first time and irrigated land. He also organized regular rubbish collections, passed a law prohibiting children from sleeping more than five to a bed, set up a court of appeal and an inspectorate to widen roads and build bridges. While it was undeniably Lilliputian compared to his former territories, he wanted Elba to be the best-run royaume d’opérette in Europe.57 His attention to the tiniest details was undimmed, even extending to the kind of bread he wanted fed to his hunting dogs.58

All this was achieved despite the fact that Napoleon had grown stout. Noting that he was unable to climb a rock on May 20, Campbell wrote that ‘Indefatigable as he is, corpulency prevents him from walking much, and he is obliged to take the arm of some person on rough roads.’59 This didn’t seem to have the same torpor-inducing effect on Napoleon that it does on others, however. ‘I have never seen a man in any situation of life with so much personal activity and restless perseverance,’ Campbell noted. ‘He appears to take so much pleasure in perpetual movement, and in seeing those who accompany him sink under fatigue . . . After being yesterday on foot in the heat of the sun, from 5 a.m. to 3 p.m., visiting the frigates and transports . . . he rode on horseback for three hours, as he told me afterwards, “to tire myself out!”’60

• • •

At noon on Sunday, May 29, 1814, Josephine died of pneumonia at Malmaison. She was fifty and five days earlier had gone out walking in the cold night air with Tsar Alexander after a ball there. ‘She was the wife who would have gone with me to Elba,’ Napoleon later said, and he decreed two days of mourning. (In 1800 George Washington had got ten.) Madame Bertrand, who told him the news, later said: ‘His face did not change, he only exclaimed: “Ah! She is happy now.”’61 His last recorded letter to Josephine the previous year had ended: ‘Adieu, my love: tell me that you are well. I’m informed that you are getting as fat as a Norman farmer’s good wife. Napoleon.’62 With this jocular familiarity concluded one of the supposedly great romances of history. She had been living beyond even her enormous income, but had come to terms with her new status as an ex-Empress. Napoleon superstitiously wondered whether it had been Josephine who had brought him luck, noting that his change of fortune had coincided with his divorcing her. By November he was expressing surprise to two visiting British MPs that she could possibly have died in debt, saying, ‘Besides, I used to pay her dressmakers’ account every year.’63

Madame Mère arrived from Rome to share her son’s exile in early August. Campbell found her ‘very pleasant and unaffected. The old lady is very handsome, of middle size, with a good figure and fresh colour.’64 She dined and played cards with Napoleon on Sunday evenings, and when she complained, ‘You’re cheating, son’, he would reply: ‘You’re rich, mother!’65 Pauline arrived three months later, the only one of his siblings to visit. Napoleon set aside and decorated rooms for Marie Louise and the King of Rome in both his residences, either in a heart-wrenching act of optimism or as a cynical propaganda move, or possibly both. On August 10 Marie Louise wrote to him to say that, although she promised to be with him soon, she had had to return to Vienna in deference to her father’s wishes.66 On August 28, Napoleon wrote the last of his 318 surviving letters to her, from the hermitage of La Madonna di Marciano, on Monte Giove, which featured his typical statistical exactitude: ‘I am here in a hermitage 3,834 feet above sea level, overlooking the Mediterranean on all sides, and in the midst of a forest of chestnut trees. Madame is staying in the village 958 feet lower down. This is a most pleasant spot . . . I long to see you, and also my son.’ He ended: ‘Adieu, ma bonne Louise. Tout à toi. Ton Nap.’67 But by then Marie Louise had found a chevalier to escort her to Vienna, the dashing one-eyed Austrian general Count Adam von Neipperg, who Napoleon had defeated in Bohemia in the 1813 campaign. Neipperg has been described as ‘skilful, energetic, a thorough man of the world, an accomplished courtier, an excellent musician’.68 In his youth he had run off with a married woman, and was himself married when he was charged with looking after Marie Louise. By September they were lovers.69

The hermitage of La Madonna di Marciano (which can today be reached after a 3-mile hike up the mountain) is a romantic and secluded spot with fabulous views over the island’s bays and inlets, from where one can see the outlines of both Corsica and mainland Italy. On September 1, Marie Walewska arrived with Napoleon’s four-year-old natural son Alexandre, and they stayed there for a couple of nights with Napoleon. She had divorced her husband in 1812, and now she had lost the Neapolitan estates that Napoleon had given her when he had broken off their affair before marrying Marie Louise. But loyalty drew her to Napoleon, however briefly. For when General Drouot warned Napoleon that island gossip had uncovered his secret – indeed a local mayor had climbed the hill to pay his formal respects to the woman everyone thought was the Empress – Marie had to leave the island.70

Napoleon gave the first of a series of interviews to visiting British Whig aristocrats and politicians in mid-November, when he spent four hours with George Venables-Vernon, a Whig MP, and his colleague John Fazakerley. In early December he twice met Viscount Ebrington, for a total of six and a half hours, and on Christmas Eve the future prime minister Lord John Russell. Two other Britons, John Macnamara and Frederick Douglas, the latter the son of the British minister Lord Glenbervie, met him in mid-January. All of these intelligent, well-connected and worldly interlocutors marvelled at the grasp of Napoleon’s mind and his willingness to discuss any subject – including the Egyptian and Russian campaigns, his admiration for the House of Lords and his hopes for a similar aristocracy in France, his plans for securing the colonies through polygamy, the duplicity of Tsar Alexander, the ‘great ability’ of the Duke of Wellington, the Congress of Vienna, the mediocrity of Archduke Charles of Austria, the Italians (‘lazy and effeminate’), the deaths of d’Enghien and Pichegru (neither of which he admitted was his fault), the Jaffa massacre (which he said was), King Frederick William (whom he called ‘a corporal’), the relative merits of his marshals, the distinction between British pride and French vanity, and his escape from circumcision in Egypt.71

‘They are brave fellows, those English troops of yours,’ he said during one of the encounters, ‘they are worth more than the others.’72 The Britons reported that he ‘talked with much cheerfulness, good humour and civility of manner’ and defended his record, on one occasion pointing out that although he had not burned Moscow, the British had set fire to Washington that August.73 Napoleon may have been trying to make a good impression in anticipation of an eventual move to London, but his intelligence and candour induced his visitors to lower their guard. ‘For my own part,’ he often said, ‘I am no longer concerned. My day is done.’ He also regularly used the expression ‘I’m dead.’74 Yet he asked lots of questions about the popularity of the Bourbons and the whereabouts of various British and French military units in southern France. He was less subtle in questioning Campbell on these subjects, to the point that the commissioner wrote to Castlereagh in October 1814 to warn him that Napoleon might be contemplating a return.75Yet the Royal Navy’s watch was not increased beyond the lone frigate HMS Partridge, and Napoleon was even allowed a sixteen-gun brig, L’Inconstant, as the flagship of the Elban navy.

• • •

On September 15, 1814 the Great Powers convened the Congress of Vienna at the instigation of Metternich and Talleyrand, where it was hoped all the major disagreements – over the futures of Poland, Saxony, the Rhine Confederation and Murat in Naples – might be settled. After nearly a quarter of a century of war and revolution the map of Europe had to be redrawn, and each of the Powers had desiderata which needed to be accommodated with those of the others to provide the permanent peace that it was hoped would follow a general settlement.76 The fall of Napoleon had reignited some long-standing territorial differences between the Powers, but unfortunately for him, although it stayed in formal session until June 1815, the outlines of agreement on all the major questions were in place by the time he decided to leave Elba in late February.

Precisely when Napoleon decided to try to retake his throne is unknown, but he watched closely the seemingly endless series of errors the Bourbons made after Louis XVIII’s return – under Allied escort – to Paris in May 1814. Napoleon increasingly believed that the Bourbons would soon experience what he called ‘a Libyan wind’ – a violent sirocco desert wind that reaches hurricane speeds and was then believed to originate in the Libyan Sahara.77 Although the king had signed a wide-ranging Charter guaranteeing civil liberties on his arrival, his government had failed to alleviate fears that they secretly wished to re-establish the Ancien Régime. Indeed, far from it. Louis’ reign was officially recorded as being in its nineteenth year, as if he had ruled France ever since the death of his nephew Louis XVII in 1795 and everything that had taken place since – the Convention, Directory, Consulate and Empire – had been merely an illegal hiatus. The Bourbons had agreed that France should go back to her 1791 borders, thereby shrinking her from 109 departments to 87.78 There were increases in the Ancien Régime-era droits réunis taxes and food prices, and the Catholic Church returned to some of its pre-revolutionary power and prestige, which irritated liberals as well as republicans.79 Official ceremonies were held at Rennes to honour the ‘martyred’ Chouans, and the remains of Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette were disinterred from the Madeleine cemetery and reinterred with much pomp in the Abbey of Saint-Denis. Although building work resumed at Versailles and the king appointed a ‘premier pousse-fauteuil’, whose sole job it was to push in his chair as he sat down at the table, pensions were cut, even to wounded veterans.80 Paintings that Napoleon had brought together at the Louvre were removed from it and returned to the occupying powers.

As Napoleon had predicted, the pre-revolutionary 1786 trade agreement with Britain was reintroduced, reducing tariffs on some British goods and abolishing them on others, thus triggering a new slump for French manufacturers.81 The British government hardly improved matters by choosing Wellington as its ambassador to France.* ‘Lord Wellington’s appointment must be very galling to the army,’ Napoleon told Ebrington, ‘as must the great attentions being shown him by the king, as if to set his own private feelings up in opposition to those of the country.’82 Napoleon later described what he thought the Bourbons ought to have done. ‘Instead of proclaiming himself Louis XVIII he should have proclaimed himself the founder of a new dynasty, and not have touched on old grievances at all. If he had done that, in all probability I should never have been induced to quit Elba.’83

The Bourbons’ most self-defeating policies were towards the army. The tricolour, under which French soldiers had won victories across Europe for over two decades, was replaced by the white flag and fleur-de-lys, while the Légion d’Honneur was downgraded in favour of the old royal orders (one of which the grognards promptly nicknamed ‘the bug’).84 Senior army posts were awarded to émigrés who had fought against France, and a new Household Guard superseded the Imperial Guard, while the Middle Guard, which Napoleon had instituted in 1806 and which boasted many proud battle honours, was abolished altogether.85 Large numbers of officers were retired by the despised Dupont and 30,000 more put on half-pay, while aggressive searches continued for draft evaders.86*‘My first hope came when I saw in the gazettes that at the banquet at the Hôtel de Ville there were the wives of the nobility only,’ Napoleon later recalled, ‘and none of those of the officers of the army.’87 In gross defiance of orders, many in the army openly celebrated Napoleon’s birthday on August 15, 1814, with cannon-fire salutes and cries of ‘Vive l’Empereur!’ as sentries presented arms only to officers wearing the Légion d’Honneur.

Of course it was not only the Bourbons’ mistakes which helped decide Napoleon to risk everything to try to regain his throne. Emperor Francis’s refusal to allow his wife and son to rejoin him was another, and the fact that his expenses were running at two and a half times his income. There was also sheer ennui; he complained to Campbell of being ‘shut up in this cell of a house, separated from the world, with no interesting occupation, no savants with me, nor any variety in my society’.88* Another consideration was paragraphs in the newspapers and rumours from the Congress of Vienna that the Allies were planning forcibly to remove him from Elba. Joseph de Maistre, the French ambassador to St Petersburg, had nerve-wrackingly suggested the Australian penal colony of Botany Bay as a possible destination. The exceptionally remote British island of St Helena in the mid-Atlantic had also been mentioned.89

On January 13, 1815, Napoleon spent two hours with John Macnamara and was delighted to hear that France was ‘agitated’.90 He admitted that he had stayed in Moscow too long and said ‘I made a mistake about England in trying to conquer it.’ He was adamant that his role in international affairs was over. ‘History has a triumvirate of great men,’ Macnamara stated, ‘Alexander, Caesar, and Napoleon.’ At this, Napoleon looked steadfastly at him without speaking, and Macnamara said ‘he thought he saw the Emperor’s eyes moisten.’ It is what he had wanted people to say ever since he was a schoolboy. Eventually Napoleon replied: ‘You would be right if a ball had killed me at the battle of Moscow but my late reverses will efface all the glory of my early years.’91 He added that Wellington was ‘a brave man’ but that he should not have been made ambassador. Napoleon laughed frequently during the conversation, as he did when told that the Prince Regent had welcomed his divorce from Josephine, as it had set a precedent for him to divorce the wife he hated, Caroline of Brunswick. Macnamara asked if he feared assassination. ‘Not by the English; they are not assassins,’ he said, but he conceded that he did have to be cautious with regard to the nearby Corsicans.92 As he left, Macnamara told Bertrand that the Emperor ‘must be a very good-humoured man and never in a passion’. Bertrand replied with a smile: ‘I know him a little better than you.’93

By the beginning of February Campbell noted that Napoleon had ‘suspended his improvements as regards roads and the finishing of his country residence’, all on grounds of expense, and had also attempted to sell Portoferraio’s town hall.94 He again warned Castlereagh that ‘If the payments promised to him at the time of abdication were withheld, and the want of money pressed upon him, I considered him capable of any desperate step.’95 Tsar Alexander later lambasted Talleyrand for not paying the funds due to Napoleon: ‘Why should we expect him to keep his word with us when we did not do so with him?’96

When Napoleon’s former secretary Fleury de Chaboulon visited him in February 1815 he brought a message from Maret that France was ripe for his return. Napoleon asked about the attitude of the army. When forced to cry ‘Vive le Roi!’, Fleury told him, the soldiers would often add in a whisper ‘de Rome’. ‘And so they still love me?’ Napoleon asked. ‘Yes, Sire, and may I even venture to say, more than ever.’ This accorded with what Napoleon was hearing from a large number of French sources and from his network of agents in France, including people like Joseph Emmery, a surgeon from Grenoble who helped plan his coming expedition and to whom he left 100,000 francs in his will. Fleury said the army blamed Marmont for the Allied victory, which prompted Napoleon to claim: ‘They are right; had it not been for the infamous defection of the Duke of Ragusa, the Allies would have been lost. I was master of their rear, and of all their resources; not a man would have escaped. They would have had their [own] 29th Bulletin.’97

On February 16 Campbell left Elba in HMS Partridge ‘upon a short excursion to the continent for my health’. He needed to visit either his ear doctor in Florence or his mistress, Countess Miniacci, or possibly both.98 This gave Napoleon his chance, and the next day he ordered L’Inconstant to be refitted, stocked for a short voyage and painted the same colours as Royal Navy vessels.99 On Campbell’s arrival in Florence, Castlereagh’s deputy at the British foreign office, Edward Cooke, told him: ‘When you return to Elba, you may tell Bonaparte that he is quite forgotten in Europe: no one thinks of him now.’100 At much the same time, Madame Mère was telling her son: ‘Yes, you must go; it is your destiny to do so. You were not made to die on this desert island.’101 Pauline, ever the most generous-hearted of his siblings, gave him a very valuable necklace that could be sold to help pay for the coming adventure. When Napoleon’s valet Marchand tried to console her by saying that she would soon be reunited with her brother, she presciently corrected him, saying that she would never see him again.102 A year later, when asked whether it was true that Drouot had tried to dissuade him from leaving Elba, Napoleon answered that it was not. In any case, he retorted curtly, ‘I do not allow myself to be governed by advice.’103 The night before Napoleon left he had been reading a life of Emperor Charles V of Austria, which he left open on the table. His elderly housekeeper kept it untouched, along with ‘written papers torn into small bits’ that were strewn about. When British visitors questioned her soon afterwards, she gave them ‘unaffected expressions of attachment, and artless report of his uniform good humour’.104

• • •

Napoleon left Elba on L’Inconstant on the night of Sunday, February 26, 1815. Once the 300-ton, 16-gun ship had weighed anchor, the 607 Old Guard grenadiers aboard were told they were headed for France. ‘Paris or death!’ they cried. He took generals Bertrand, Drouot and Cambronne, M. Pons the inspector of mines, a doctor called Chevalier Fourreau, and a pharmacist, M. Gatte. They were attempting to invade a great European country with eight small vessels, the next three largest of which were only 80, 40 and 25 tons, carrying 118 Polish lancers (without their horses), fewer than 300 men of a Corsican battalion, 50 gendarmes, and around 80 civilians (including Napoleon’s servants) – a total force of 1,142 men and 2 light cannon.105 A moderate breeze carried them to France, and they narrowly missed two French frigates on the way. Napoleon spent a lot of time on deck, chatting to officers, soldiers and sailors. The commander of the lancers, Colonel Jan Jermanowski, recorded:

Lying down, sitting, standing, and strolling around him, familiarly, they asked him unceasing questions, to which he answered unreservedly and without one sign of anger or impatience, for they were not a little indiscreet, they required his opinions on many living characters, kings, marshals and ministers, and discussed notorious passages of his own campaigns, and even of his domestic policy.106

During this he spoke openly of ‘his present attempt, of its difficulties, of his means, and of his hopes’.

L’Inconstant sailed into Golfe-Juan on the southern French coast on Wednesday, March 1, unloading Napoleon’s force by 5 p.m. ‘I have long weighed and most maturely considered the project,’ Napoleon harangued his men just before they went ashore, ‘the glory, the advantages we shall gain if we succeed I need not enlarge upon. If we fail, to military men, who have from their youth faced death in so many shapes, the fate which awaits us is not terrific: we know, and we despise, for we have a thousand times faced the worst which a reverse can bring.’107 The following year he reminisced about the landing: ‘Very soon a great crowd of people came around us, surprised by our appearance and astonished by our small force. Among them was a mayor, who, seeing how few we were, said to me: “We were just beginning to be quiet and happy; now you are going to stir us all up again.”’108 It was a sign of how little Napoleon was seen as a despot that people could speak to him in that way.

Knowing that Provence and the lower Rhône valley were vehemently royalist, and that for the moment he needed above all else to avoid any Bourbon armies, Napoleon resolved to take the Alpine route to the arsenal of Grenoble. His instinct was proved right when the twenty men under Captain Lamouret whom he sent off to Antibes were arrested and interned by the local garrison. He hadn’t the troops to attack Toulon, and was conscious of the need to move faster than the news of his arrival, at least until he could augment his force. ‘That is why I hurried on to Grenoble,’ he later told his secretary General Gourgaud. ‘There were troops there, muskets, and cannon; it was a centre.’109 All he had was the capacity for speed – horses were soon bought for the lancers – and a genius for propaganda. On landing he issued two proclamations, to the French people and the army, which had been copied out on board ship by hand by as many of the men as were literate.

The army proclamation entirely blamed the 1814 defeat on the treason of Marmont and Augereau: ‘Two men from our ranks have betrayed our laurels, their country, their prince, their benefactor.’110 He turned his back on bellicosity, declaring: ‘We must forget that we were masters of nations, but we must not suffer anyone meddling in our business.’ In the proclamation to the people, Napoleon said that after the fall of Paris, ‘My heart was torn apart, but my spirit remained resolute . . . I exiled myself on a rock in the middle of the sea.’111 It was only because Louis XVIII had sought to reintroduce feudal rights and rule through people who had for twenty-five years been ‘enemies of the people’ that he was acting, he claimed, despite the fact that the Bourbons had certainly not yet got around to reviving feudalism. ‘Frenchmen,’ he continued, ‘in my exile I heard your complaints and wishes; you were claiming that government of your choice, which alone is legitimate. You were blaming me for my long sleep, you were reproaching me for sacrificing to my repose the great interests of the State.’ So, ‘amid all sorts of dangers, I arrived among you to regain my rights, which are yours.’112 It was tremendous hyperbole, of course, but Napoleon knew how to appeal to soldiers who wanted to return to glory and full pay, better-off peasants who feared the return of feudal dues, millions of owners of the biens nationaux who wanted protection from the returning émigrés and churchmen who wanted their pre-1789 property back, workers hit by the flood of English manufactured goods and imperial civil servants who had lost their jobs to royalists.113 The Bourbons had failed so comprehensively in less than a year that even after the defeats of 1812 and 1813 Napoleon was able to put together a fairly wide-ranging domestic coalition.

On the day he landed Napoleon bivouacked on the dunes at Cannes not far from the present-day Croisette, opposite an old chapel that is today the church of Notre-Dame. At two o’clock the next morning he joined Cambronne’s advance guard, which included unmounted lancers and the two cannon. Instead of going to Aix, the Provençal capital, he took the road through Le Cannet which climbs 15 miles up to Grasse, which – since there were only five working muskets in his town – the mayor surrendered. After resting till noon, Napoleon abandoned his carriages and cannon, mounted his supplies on mules, and took the mountain road northwards. There was snow and ice on the higher parts, where some mules slipped and fell, and at points the road narrowed to single file. He walked on foot among his grenadiers, who affectionately teased him with nicknames such as ‘Notre petit tondu’ (Our little cropped one) and ‘Jean de l’Epée’ (Jack of the Sword).114

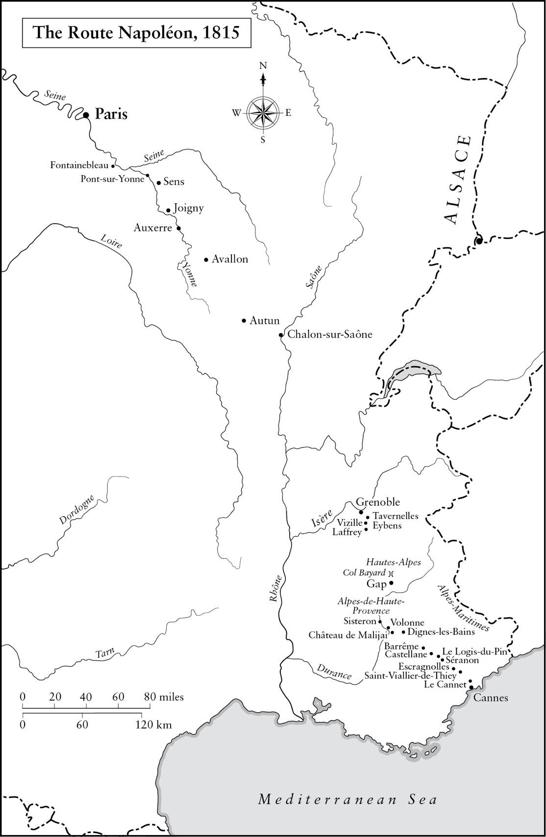

The ‘Route Napoléon’ was instituted by the French government in 1934 to encourage tourism, and impressive stone eagles were placed along it, of which a handful still survive today. Every town and village Napoleon went through has a sign proudly announcing the fact, and it is possible to see many of the places where he slept on what became a legendary journey north. Starting in the Alpes-Maritimes department, he marched through Alpes-de-Haute-Provence and Hautes-Alpes, and reached Grenoble in the Isère by the night of March 7, travelling 190 miles in only six days. He went on foot and on horseback across high plateaux and plains, over bare rocks and verdant pasture, past Swiss-style villages, over 6,000-foot snow-capped mountains with vertiginous drops and down winding Corniche-style roads. Today the Route Napoléon is considered one of the great cycling and motorcycling roads of the world.

After Saint-Vallier, Napoleon passed through the villages of Escragnolles, where he called another halt, Séranon, where he slept at the Château de Brondel, the country house of the Marquis de Gourdon, and Le Logis-du-Pin, where he was served broth. Reaching Castellane by noon on March 3 he lunched at the sous-préfecture (today in the Place Marcel Sauvaire), where Cambronne demanded 5,000 rations of meat, bread and wine from the mayor, a few days’ provisions for his still tiny force of less than a thousand. (Campbell thought Cambronne ‘a desperate, uneducated ruffian’, so he was just the right man for such an adventure.115) Napoleon spent that night in the hamlet of Barrême, where he slept in the house of Judge Tartanson on the main road. The next day he reached Digne-les-Bains and rested at the Petit-Palais hotel, where he was joined by some veterans of his Grande Armée. The people of Digne begged the pro-Bourbon commander of the Basses-Alpes department, General Nicolas Loverdo, not to turn their town into a battleground, and finding himself short of loyal troops he didn’t. Napoleon then pushed on and spent the night in the Château de Malijai, which today is the town hall.*

The next morning, Sunday, March 5, Napoleon halted at the village of Volonne, by local legend drinking at a fountain dating back to Henri IV. He faced his first real test at the massively imposing castle of Sisteron, where the guns of the great citadel there could easily have destroyed the sole bridge across the Durance. Instead he lunched with the mayor and notables in the Bras d’Or hotel and went on his way shortly afterwards. From the top of the citadel’s bell-tower it is possible to see up and down the River Durance for 40 miles; Napoleon would have had nowhere else to cross. Either due to an oversight, economies or because its commander wanted an excuse not to destroy the bridge, the castle had no gunpowder, and from then on whenever Cambronne arrived ahead of Napoleon to cajole, negotiate, bribe and, if necessary, threaten the mayors of each town, no bridge was destroyed.

Napoleon later recalled that when he reached Gap ‘Some of the peasants took five-franc pieces stamped with my likeness out of their pockets, and cried, “It is he!”’116* ‘My return dispels all your anxieties,’ he wrote in a proclamation from Gap to the inhabitants of the Upper and Lower Alps, ‘it ensures the conservation of all property.’ In other letters he specifically played on the fears of what might happen under the Bourbons (but hadn’t yet) when he stated that he opposed those ‘who wish to bring back feudal rights, who wish to destroy equality between different classes, cancel sales of biens nationaux’.117 He left Gap at 2 p.m. on March 6. From there the ground rises steeply, up to the Col Bayard at 3,750 feet. That night Napoleon slept in the gendarmerie in the main street of Corps.

Easily the most dramatic moment of the journey came the following day a few hundred yards south of the town of Laffrey, where Napoleon encountered a battalion of the 5th Line in a narrow area between two wooded hills on what is today called La Prairie de la Rencontre. According to Bonapartist legend, Napoleon, standing before them well within musket range, with only his far smaller number of Imperial Guardsmen protecting him, threw back his iconic grey overcoat and pointed to his breast, asking if they wanted to fire on their Emperor. In testament to the continuing power of his charisma, the troops threw down their muskets and mobbed him.118 Napoleon had previously been informed by two officers of the pro-Bonapartist attitudes of the demi-brigade, but a single shot from a royalist officer could have brought about a very different outcome. Savary, who wasn’t present, told a slightly less heroic version, in which Napoleon’s conversational style and habit of question-asking saved the day.

The Emperor approached; the battalion kept a profound silence. The officer who was in command ordered them to aim their muskets: he was obeyed; if he had ordered Fire we cannot say what would have happened. The Emperor didn’t give him time: he talked to the soldiers and asked them as usual: ‘Well! How are you doing in the 5th?’ The soldiers answered ‘Very well, Sire.’ Then the Emperor said: ‘I’ve come back to see you; do some of you want to kill me?’ The soldiers shouted ‘Oh! That, no!’ Then the Emperor reviewed them as usual and thus took possession of the 5th Regiment. The head of the battalion looked unhappy.119

When Napoleon himself told the story he said he had adopted a jovial, old-comrade attitude towards the troops: ‘I went forward and held out my hand to a soldier, saying, “What, you old rascal, were you about to fire on your Emperor?” “Look here,” he answered, showing me that his musket was not loaded.’120 He also put the success down to having his veterans with him: ‘It was the bearskin helmets of my Guards which did the business. They called to memory my glorious days.’121 Whether Napoleon had been declamatory or conversational at that tense moment, he showed great nerve. Laffrey also represented a watershed, because for the first time regular soldiers, rather than peasants or National Guardsmen, had come over to his side.

After being cheered by crowds at Vizille – where Charles de La Bédoyère brought the 7th Line over to him – taking refreshment at Mère Vigier’s café in Tavernelles and having a by then well-deserved footbath at Eybens, Napoleon entered Grenoble at 11 p.m. on March 7. There the townspeople tore down their own city gates and presented pieces of them to Napoleon as a souvenir of their loyalty. ‘On my march from Cannes to Grenoble I was an adventurer,’ Napoleon later said; ‘in Grenoble I once again became a sovereign.’122 Rejecting an offer to stay at the prefecture, Napoleon displayed his customary genius for public relations by instead staying in room No. 2 of the hotel Les Trois Dauphins in the rue Montorge, which was run by the son of a veteran of his Italian and Egyptian campaigns and was where he had stayed in 1791 when stationed at Valence. (Stendhal stayed in the same room in 1837, out of homage.) Any lack of comfort was made up for in Lyons where he stayed in the archbishop’s palace (today the city library), occupying the same apartments that the king’s brother, the Comte d’Artois (later King Charles X) had been forced to leave hastily that same morning. When Napoleon conducted a review of his by now sizeable force in Lyons, he reprimanded a battalion for not manoeuvring well enough. This, he later said, ‘had a great effect; it showed he was confident of his re-establishment’.123 Had he adopted an imploring attitude at that key moment, his men would have spotted it immediately. Instead, even after his defeats and abdication, they were still willing to follow him.

The news of Napoleon’s return reached Paris at noon on March 5 via the Chappe aerial telegraph, but the government kept it secret until the 7th.124 Ney, Macdonald and Saint-Cyr were deputed by Soult, the new war minister, to address the problem, whereupon Ney told Louis XVIII: ‘I will seize Bonaparte, I promise you, and I will bring him to you in an iron cage.’125 Soult’s order to the army stated that only traitors would join Napoleon, and ‘This man is now but an adventurer. His last mad act has revealed him for what he is.’126 And yet, for all this, the only two marshals to fight alongside Napoleon on the battlefield of Waterloo would be Ney and Soult.

On the day Napoleon left Lyons, March 13, the Allies, still in session at the Congress, issued the Vienna Declaration.

By appearing again in France with projects of confusion and disorders, [Napoleon] has deprived himself of the protection of the law and has manifested before the world that there can be neither peace nor truce with him. The Powers consequently declare that Napoleon Bonaparte has placed himself beyond the pale of civil and social relations, and that as an enemy and disturber of the world, he has delivered himself up to public vengeance.127

Napoleon continued northwards, spending the following night at Chalon-sur-Saône, the 15th at Autun, the 16th at Avallon and the 17th in the prefecture at Auxerre. He was greeted by large, enthusiastic crowds and joined by further units of soldiers along the way. He sent two officers in disguise to Marshal Ney, who was in command of 3,000 men at Lons-le-Saunier, telling him that if he changed sides, ‘I shall receive you as I did on the morrow of the battle of the Moskowa.’128 Ney had had every intention of fighting against Napoleon when he left Paris, but he had no wish to start a civil war, even if he could persuade his men to open fire. ‘I was in the midst of storms,’ he later said of his decision, ‘and I lost my head.’129 On March 14 Ney defected to Napoleon with generals Lecourbe and Bourmont (who were both very reluctant) and almost all his troops except for a few royalist officers. ‘Only the Emperor Napoleon is entitled to rule over our beautiful country,’ Ney told his men.130 He later said that the Bonapartist sentiment among the men was overwhelming and he couldn’t ‘hold back the sea with my hands’.131

Napoleon met Ney on the morning of the 18th at Auxerre, but as Ney had brought along a document warning him that he needed ‘to study the welfare of the French people and endeavour to repair the evils his ambition had brought upon him’ it was a cold, workmanlike reunion.132 Instead of treating him as he had ‘on the morrow of the battle of the Moskowa’, Napoleon questioned him about the morale of his troops, the state of feeling of the south-eastern departments and his experiences on the march to Dijon, to which Ney gave brief replies before being ordered to march on Paris.

On the 19th Napoleon lunched at Joigny, reached Sens by 5 p.m. and dined and slept at Pont-sur-Yonne. Then at 1 a.m. on Monday, March 20 he left for Fontainebleau, where he arrived in the White Horse courtyard eleven months to the day after leaving it. At 1.30 that morning the gouty Louis XVIII was bodily lifted into his carriage at the Tuileries – no easy task given his weight – and fled Paris. He went first to Lille, where the garrison seemed hostile, so he crossed into Belgium and then waited upon events from Ghent. With his customary veneration for anniversaries, Napoleon had wanted to enter Paris on the 20th – the King of Rome’s fourth birthday – and sure enough, at nine o’clock that evening he entered the Tuileries once again as de facto emperor of the French.

The courtyard of the Tuileries was packed with soldiers and civilians who had come to witness his return. There are several accounts of what happened next, all agreeing on the din of excitement and the general approval that Napoleon elicited upon his arrival. Colonel Léon-Michel Routier, who had fought in Italy, Calabria and Catalonia, was walking and chatting with comrades-in-arms near the pavilion clock at the Tuileries when

suddenly very simple carriages without any escort showed up at the wicket-gate by the river and the Emperor was announced . . . The carriages enter, we all rush around them and we see Napoleon get out. Then everyone’s in delirium; we jump on him in disorder, we surround him, we squeeze him, we almost suffocate him . . . The memory of this unique moment in the history of the world still makes my heart pound with pleasure. Happy who, like me, was the witness of this magical arrival, the result of a road of over two hundred leagues travelled in eighteen days on French soil without spilling one drop of blood.133

Even General Thiébault, who until earlier that day had been in charge of the defence of southern Paris against Napoleon, felt that ‘There was an instantaneous and irresistible outburst . . . you would have thought the ceilings were coming down . . . I seemed to have become a Frenchman once more, and nothing could equal the transports and the shouts with which I tried to show the party I was taking part in the homage rendered to him.’134 Lavalette recalled that Napoleon walked up the staircase of the Tuileries ‘slowly, with his eyes half closed, his arms extended before him, like a blind man, and expressing his joy only by a smile’.135 Such was the press of cheering supporters that it was only with difficulty that the door to his apartment could be closed behind him. When Mollien arrived that night to offer his congratulations, he embraced him and said, ‘Enough, enough, my dear, the time for compliments has passed; they let me come as they let them go.’136

After the dramas of the journey from Golfe-Juan, changing the regime in Paris came easily. That first night it was noticed that the fleur-de-lys covering the carpet in the palace’s audience chamber could be removed, and underneath could still be seen the old Napoleonic bees. ‘Immediately all the ladies set to work,’ recalled a spectator of Queen Julie of Spain, Queen Hortense of Holland and their returning ladies-in-waiting, ‘and in less than half an hour, to the great mirth of the company, the carpet became imperial again.’137