Mohenjodaro

Mohenjodaro in Sindhi means ‘mound of the dead’. It was first excavated in 1920–21, and then between 1922 and 1931. The site comprises two mounds—the higher but smaller western mound and a much larger but lower eastern mound, both separated by an open space and about 5 km west of the present bed of the Indus. Excavation in the early years was conducted in both the mounds. In 1950, Wheeler excavated only in the western mound, and in 1964–65 G.F. Dales (1965; Dales and Kenoyer 1986) excavated at the western edge of the HR section in the south-western corner of the eastern mound. In modern times, the condition of the excavated burnt-brick ruins has deteriorated because of the underground salt action. This led to the programme of rigorously documenting everything related to the site, which has been completed in recent years under M. Jansen.

There is no positive evidence that the site ever stood on the bank of the Indus or that the river sent any branch or canal to it. The present open space between the two mounds was open in the past too. The limits of the site are ill-defined. The visible space is c. 95 ha, but Jansen’s survey has traced ruins up to about 2 km to the east. It is possible that these newly discovered ruins belong only to the late phase of the site’s history, but still, the total built-up area is now estimated to be c. 200 ha. Because of sub-soil water no excavation could reach the earliest occupational deposit. On the basis of two deep borings in the present plain outside the HR section, Dales wrote that the traces of occupation were found till a depth of 12 m below the present ground level. The height of the mound above the present ground level was 10.5 m feet. This means that the total occupational deposit in this part of the mound is 22 m in all. The sub-soil water was encountered at the depth of only 4.5 m below ground level, and this meant that the excavator had to leave 7 m of occupational deposit at that point unexcavated. This tells us very clearly that the early level of Mohenjodaro is unknown.

An interesting argument has been offered to explain the occurrence of artefacts at a depth of 12 m below the present ground level. This explanation is based on the fact that the two mounds of the site were both built on huge man-made platforms of mud and mud-brick. To get clay for these bricks, the builders of Mohenjodaro must have dug in the immediate area, and thus created a wide and deep ditch around it. As people living in houses built on the top of the two platforms threw rubbish in this ditch, artefacts would be found at a much lower depth than the level of the actual occupation. It is an interesting hypothesis but certainly not beyond doubt. There may be a substantial depth of unexcavated early occupation deposit at Mohenjodaro.

If one leaves aside the still undocumented and presumably late extension of the city to the east, the urban configuration of Mohenjodaro centres around its western and eastern mounds. The occupational remains in the western mound, at the north-eastern corner of which is a Buddhist stupa of the early centuries AD, were built on top of an artificially constructed mud and mud-brick platform which measured approximately 400 × 200 m. There was a 6 m thick mud-brick retaining wall around it, with its height rising above the level of the platform. There are traces of salients or projections from this wall on the south-west and the west. A tower on this salient has been excavated on the south-east. Access to the top of the platform was probably by a stairway going down to the level of the plain. No trace of this stairway has survived.

The stupa area at the north-east corner of this mound, which also represents its highest point, has not been excavated, and this presumably marked the most sacred spot of the site. There is a road called ‘Divinity Street’ in front, and across this street (c. 2–3 m wide) is what has been named a ‘college’ of priests mainly because of the thickness of its outer wall, size (c. 70 m × c. 24 m), composition as a single architectural unit, and proximity to the inferred sacred spot. In the same sector there is another building which shows four bathroom-like rooms on either side of a passage with a covered drain. The inference is that priests used to live on the top floor of this complex and they had a special suite of bathrooms. There are three other interesting complexes in the western mound. First, there is the Great Bath which is basically a c. 14.5 m × c. 7 m burnt-brick-built pool sunk c. 2.43 m below the level of the surrounding open brick-paved courtyard. It was accessed by steps which had wooden covers fixed by bitumen or asphalt. The sides of the pool had another set of walls surrounding them, with the intervening space between the two being filled with a bitumen coating and earth. Its water was drained by a large corbelled drain which went down the mound’s western slope. Water to fill it was possibly drawn from the well found in one of the rooms fronting the open courtyard around it. The bricks for construction were laid on edge and made watertight by using gypsum as mortar. The whole complex had a 5 m wide road around it and was thus the only free-standing structure of Mohenjodaro, which could be walked around outside. To its immediate south-west is what has been called a granary. This complex was made of 27 mud-brick blocks with passages between them for smooth air-flow. Built integrally with it in the north was a loading platform made of burnt-bricks. The mud-brick blocks have been presumed to have had wooden superstructures which were filled with grain by standing on top of the loading platform which had an alcove at its eastern end. In the southern sector of the western mound is the so-called assembly hall. Roughly square in shape, this has 20 rectangular brick piers arranged in rows of five each and dividing the hall from east to west into five aisles or corridors. It would be incorrect to claim that all the houses excavated in the western mound fall into non-residential category, such as the ones mentioned here, but the very fact that the complexes like the Great Bath, the Granary, the ‘assembly hall’, the ‘collegiate building’ and the complex with eight bathrooms arranged in two rows existed in this area suggests its somewhat exclusive character. When one considers, along with this, its general height and smaller size in relation to the eastern mound, the reason for it being called ‘citadel area’ becomes obvious.

In the eastern section we have one main north–south street (‘First Street’ of the excavators), traces of two more north–south streets at an equal distance (180 m) from the First Street and no evidence of a main east–west street. Excavations at the western edge of the HR area in 1964–65 revealed massive and solid mud-brick embankments with a series of at least 6 m high retaining walls of burnt-brick. This indicates the possibility of such surrounding walls around the entire periphery of the eastern mound. The excavated remains of the HR area provide a fairly clear picture of the arrangement of ordinary houses of Mohenjodaro, which were also built on artificial platforms of varying heights. The First Street (9–10.5 m wide), two smaller and roughly parallel side-streets to its west and a few lanes with sharp turns frame these houses whose main entrance is in general from the side-streets or lanes and whose main focus is either an open or lightly covered courtyard with rooms disposed in various fashions around it. Drains which were made of burnt-bricks and given a cover of stone slabs or burnt-bricks are fairly common in this area as elsewhere in the excavated parts of the city. Interestingly, two brick-built cess-pits in the First Street had a connecting brick drain between them to carry the surplus water of the northern pit to the southern one, which had in addition a series of brick-steps on one side so that somebody could go down and clean it. This regular cleaning arrangement of drains (general width 23 cm and depth 45–60 cm) is also clear from the little deposits of sand found along them. Even brick culverts (some as large as 75 cm wide and 120–150 cm high) to discharge the total water from the drains have been found in the outskirts of the site. The soak-pits placed at the mouths of water-chutes coming out of the houses were earthen jars with holes at the bottom. In the western part of the HR area, a double row of sixteen houses with a single room in front and one or two smaller rooms at the back has been interpreted as shops or working-men’s quarters. In the VS area a house showed a room with five sunken brick-made hollows in which the bottoms of large jars could fit. As this room could be entered directly from the main road, the inference is that this could be a sweetmeat shop or a place where dyeing vats were kept. Within the range of such little variations the Mohenjodaro houses are standardized, and the speculations about their functions or ownership on the basis of their general size and thickness of walls do not really add up to much.

Chanhudaro

No fortification or urban wall could be traced at Chanhudaro, possibly located on an old bed of the Indus in Sind and excavated principally in 1935–36. Mud-brick platforms, miscellaneous structural ruins and traces of at least three streets—the main one 5.68 m wide and with two covered burnt-brick-built drains on two sides—and a lane have been excavated. On the eastern side of the main street is what has been called a bead-making factory on the basis of a large number of finished and unfinished beads there. Some evidence of a regulated town-plan has also been found at a few smaller excavated sites in Sind, such as Ali Murad (a partially traced fortification wall made of stone blocks), Kot Diji (a street and a lane) and Ahladino (an open court with a well and surrounding buildings with bathrooms and covered drains).

Harappa

The search for burnt-bricks, broken bits of which could be used as ballast by the builders of the railway line between Lahore and Multan led to the large-scale spoliation of this site which has a higher and smaller western ‘citadel’ section on the bank of an old bed of the Ravi and a larger and lower habitation area to the east. The structures inside the western mound are much too destroyed for any worthwhile excavation results, and the excavations at the site between 1920–21 and 1933–34 and in 1946 were mainly focused on the buildings between the western mound and the bed of the Ravi and on the cemeteries to the south of this mound. Cemeteries were, in fact, sporadically excavated even after 1946 but the modern phase of excavations at the site, which began in 1986 and is continuing through the 1990s, has made a conscious effort to investigate the habitational area on the east. The total area of the site, by modern reckoning, is c. 150 ha, out of which a c. 442 × 244 m area is occupied by the western mound and roughly a 300 m square area by the mound near the Ravi. The western mound was fortified with a wall with a burnt-brick revetment, which possessed a slope both inside and outside, a varying width, towers and salients, a set of terraces along the western edge for ceremonials and the main gateway presumbably in the north. The whole complex was raised on an artificial platform of mud and mud-bricks. There were three complexes near the Ravi: the ‘Great Granary’, constructed in two blocks with six halls raised higher than the ground on sleeper-like walls and with passages between them, about 18 circular platforms (11 m in diameter and all equidistant—roughly a little more than 6 m—from one another) with their centred hollows being used for pounding grains, and a block of 14 small houses which could have housed working people associated both with the pounding of grains and the sixteen copper-smelting furnaces found at a higher level near them. There are two cemeteries, named Cemetery R37 and Cemetery H, to the south of the fortified western mound.

The evidence of habitation in the eastern mound is still not very sharp, but the traces of small streets, drains and soak pits occur in its north-western section which also has a series of mud-brick platforms with burnt-brick retaining walls. A 5.4–6.5 m thick free-standing mud-brick wall of two structural phases has been traced for more than 73 m along the southern edge of the mound, and more interestingly, with a 2.6 m wide gateway. The walls associated with the gateway system are 9 m thick and their outer faces bear the traces of a burnt-brick cover of their otherwise mud-brick body.

Kalibangan

Excavated between 1960–61 and 1968–69, the site is located on the bank of the dry bed of the Ghaggar and comprises two mounds—the smaller western mound and the larger eastern mound with an open space between them—and a burial ground to the west-south-west of the western mound. The western fortified enclosure (c. 240 × c. 120 m; 3 to 7 m wide and with rectangular salients and towers) was partitioned into two units by an inner wall with stairways on either side for movement between the two units. The southern unit had, on its south, a series of steps fronting the fortification wall which was provided with a passage across it at this point. Otherwise, this unit contained several mud-brick platforms, possibly with structures on them. These structures have disappeared but on top of one of the platforms there are seven fire-altars in a row. These rectangular altars were sunk into the floor, plastered with clay and contained a cylindrical and faceted clay stump and terracotta ‘cakes’ associated with ash and charcoal. There were a few bath-pavements and a well near these ‘fire-altars’, and there is little doubt that the southern unit was used for rituals. The buildings inside the northern unit suggest a residential purpose and it appears that the people associated with the performance of rituals in the southern unit lived in a specific enclosure, i.e. the northern unit, meant apparently only for them.

A 3 to 3.9 m wide mud-brick wall, which in its northern section was made in a box-like fashion with mud filling inside, enclosed the eastern mound (c. 360 × 240 m) which had a gate on the western side and an entrance at the north-western corner. The streets, of which five have been traced, are 1.8 to 7.2 m wide and were paved with terracotta nodules in the late phase and had occasionally street-fenders at the turnings. Most of the houses had fire-altars of the type noticed in the western mound. In one case the entrance to the house was from a lane and there was a corridor from this entrance to a courtyard around which there were rooms of different dimensions (3 × 2 m, 2 × 1 m). There were 70–75 cm wide single-leaf doors. Oblong troughs made of mud-bricks in some courtyards may suggest the feeding of cattle, among other things. To the east of the eastern mound an isolated structure with five ‘fire-altars’ suggests a religious place.

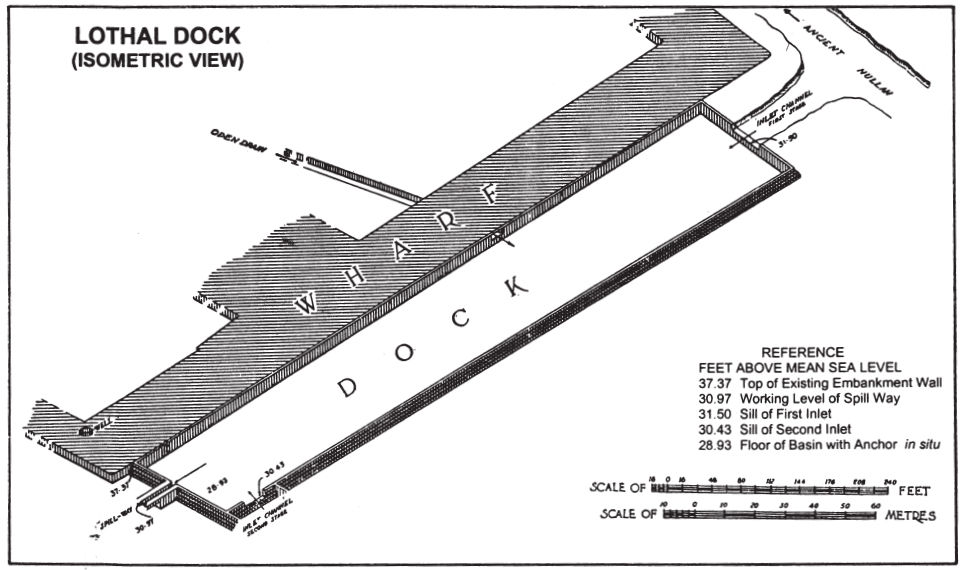

Fig. 18 Lothal dock (Rao, 1979)

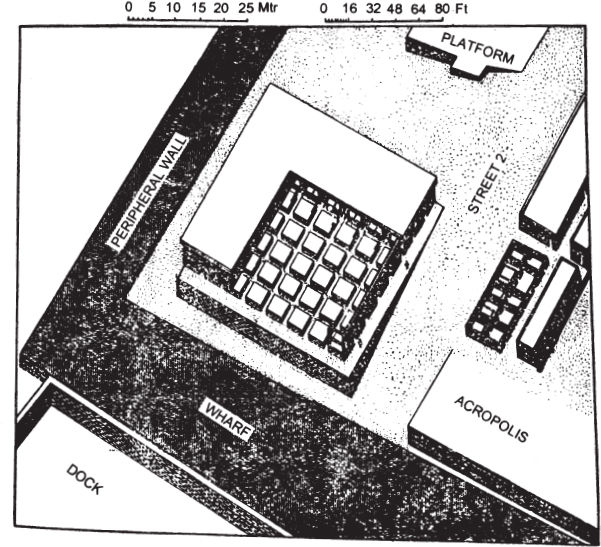

Fig. 19 Lothal warehouse complex (Rao, 1979)

Banawali

Considerably upstream along the Ghaggar, not far from Hissar on the way to Sirsa, is Banawali (excavated in 1974–77 and 1983–84) which is a 300 × 150 m fortified site, with a part of it partitioned by a wall to form a ‘citadel’. The plan is somewhat confusing but apparently irregular with a number of obliquely laid streets. A house in the town area (i.e. in the area outside the ‘citadel’) has been graphically described by the excavator R.S. Bisht (1982):

It contained several rooms, probably a courtyard and a corridor, a large room having many earthen jars half embedded in the house floor, a sitting room paved with bricks, a worship room with a fire-place, and a kitchen with several hearths— both on an elevated ground and the ground level—a toilet fitted with a wash-basin emptying its sullage through a pucca drain into a soakage jar placed outside the major street, and a roadside platform constructed against the building complex and just outside the room of the pottery jars mentioned above…. A prominent merchant might have been the owner of this house since it has given a rich harvest of seals, weights, beads including those of gold, lapis and etched carnelian, besides the deluxe pottery of the age.

The excavator’s interpretation may not be beyond doubt, but the image is striking enough.

Lothal

Located in the rich wheat-and-cotton-growing deltaic and low-lying area between the Bhogavo and the Sabarmati rivers in the Saurashtra peninsula of Gujarat, this settlement (excavated in 1955–62) measures only 240 m × 210 m but has an integrated and enclosed layout with a dockyard. The sea is now about 16–19 km away but according to the local tradition it was once much nearer and the place is in fact approachable by boat from the coast at certain times of the year. Compared to the size of the settlement which had a burial ground in the north-west outside the enclosed area, its peripheral wall—initially of mud, an d later of mud-bricks with burnt-bricks on the north—is impressive: c. 13 m on the south and c. 22 m on the east, c. 1.8 m–2.4 m high on the south and c. 2.4 m high on the east. The entrance was on the south. There was no dividing wall inside, but in the southern section the mud and mud-brick platforms on which houses were built stood higher than such foundation platforms found elsewhere in the settlement and formed thus a more elevated area in this section. Three house-blocks with both exposed and covered drains, cess-pools and soakage jars have been excavated in this section. One of these house-blocks is supposed to have been a warehouse. It stands on a mud-brick podium (c. 49 m × c. 41 m × c. 4.1 m) with an outer platform, and had on it 12 solid blocks of mud-brick (each 3.65 m square and 0.91 m high) separated by c. 1 m wide criss-cross passages. As 65 terracotta sealings with impressions of reed, woven fibre, matting and even, twisted cords have been found in this complex it is fair to imagine that it was ‘a large warehouse wherein packages of goods were examined and stored’. Another house-block in this sector which has two streets, some lanes and two associated drains shows a row of 12 houses (each 7.62–8.53 m long and 5.48 m wide) with their bathing pavements at the back being connected with a drain outside. Outside this cluster of higher house-blocks, the main habitation area too is composed of house-blocks (sizes vary from 114.3 m × 22.86 m to 48.78 m × 41.14 m), although of a lesser elevation (from 1.21 m to 3.65 m). One house here has a wide (12.19 m) verandah, with three rooms arranged in a row along its length. Bathrooms connected to the outside drains are a common feature, and so is the presence of small sacrificial pits containing terracotta cakes or round lumps and ashes. A niche found in the roadside face of a house may suggest the placing of lamps in such niches at night. The streets (3.65 to 5.48 m wide) and lanes (1.82 m to 2.74 m wide) were all paved with mud-bricks with a layer of gravel on top. The street drains (internal width 1.21 m to 0.64 m) had a carefully provided gradient, with screens at their mouth to prevent solid waste from falling in cess-pools, one of which was 1.31 m square and about 1.52 m deep. The Lothal ‘dockyard’ is a roughly trapezoidal area (western wall: 218.23 m, eastern wall: 215.03 m, southern wall: 35.66 m and northern wall: 37.49 m) enclosed by a four-course burnt-brick wall on the inner side of broader mud-brick embankment walls. There are two inlets to this enclosure, one each in the northern and southernmost portions of the eastern side. There is also a spill-channel which is basically a narrow burnt-brick-built passage at the southern arm. At high tide the sea-going vessels could enter the inlet and a regular level of water could be maintained by regulating it by means of a wooden sluice-gate fitted across the spill-channel. The presence of marine organism detected inside the enclosure has more or less proved that this was really a dockyard. A mud-brick platform (12.8 m wide and 243.84 m long) adjoining its western embankment possibly served as a ‘wharf’ for the loading and unloading of goods.

Surkotada

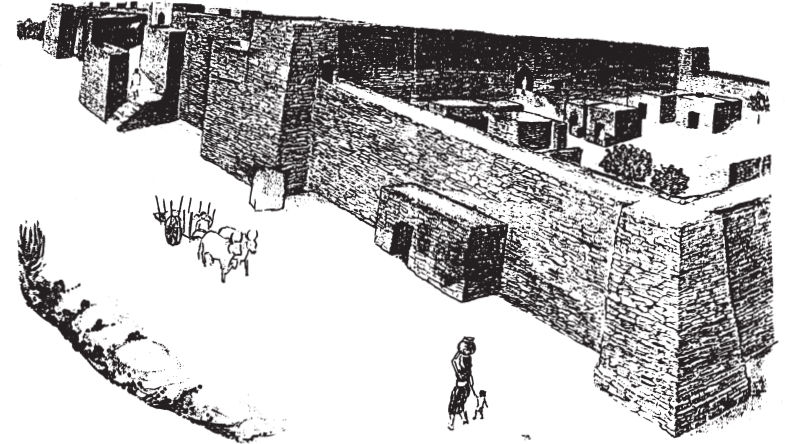

The plan of Surkotada (excavated in 1971–72) is almost similar to the plan uncovered in the western mound of Kalibangan: a fortified complex with a clear walled division inside between the non-residential and residential parts. Before building the complex the ground level was raised by rammed mud deposit, about 1.5 m high in the non-residential section and 0.5 m high in the residential area. Thus, the non-residental section had a higher elevation than the residential one. The non-residential area measured 60 m square but the exact area of the residential part could not be determined. The 7 m wide fortification wall enclosing the non-residential area was made of mud and mud-brick, with a rubble cover on the outside and mud-plaster on the inside. Its eastern side was provided with a buttress of mud-brick with rubble cushioning at a later stage. The wall around the residential section was only 3.25 m wide. The main entrance to the non-residential section was in the south, with an opening to the residential section to its east. No inner structural complex is worthy of notice here. There is a burial ground to the north-west of the fortified enclosure.

Fig. 20 General reconstruction of Surkotadạ Harappan settlement (Joshi, 1990)

Dholavira

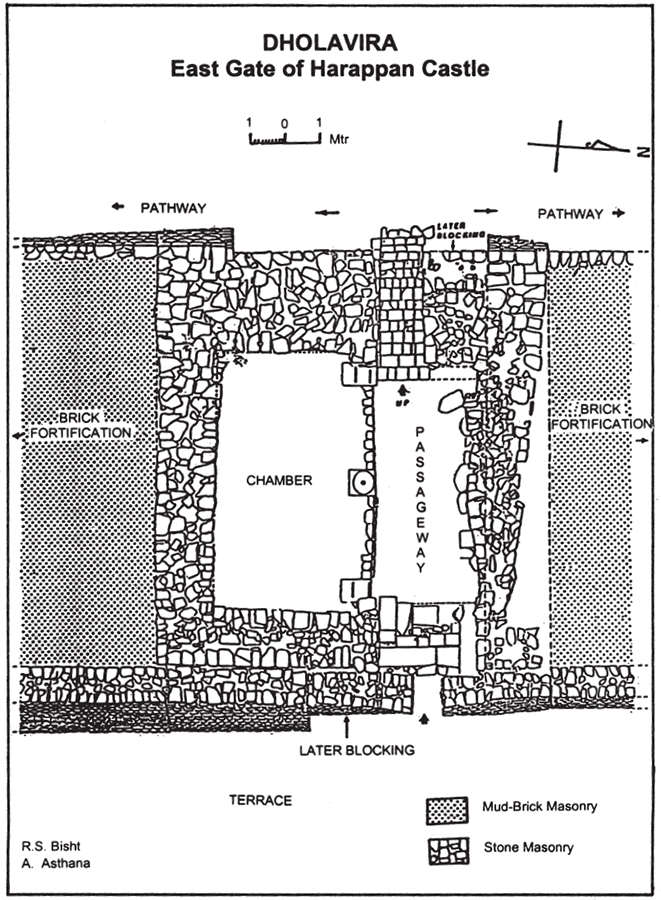

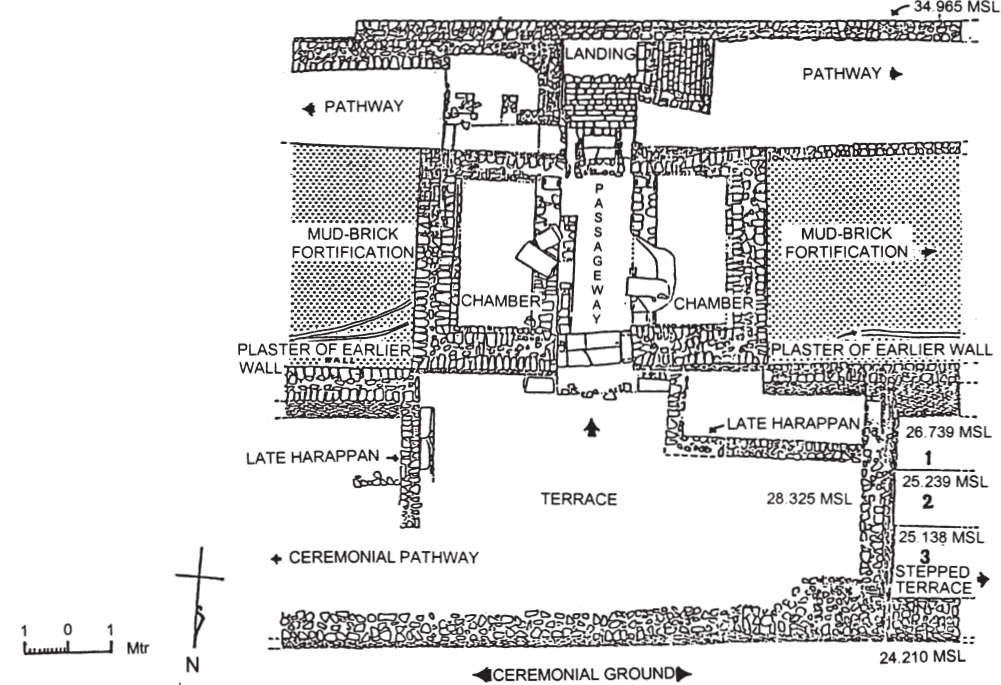

Excavations began at this 100 ha site (inclusive of the ruins outside the fortified area and a burial ground to the west) in an island or ‘bet’ of the Rann of Kutch in 1989–90 and have continued, with interruptions, till the present (1998). It lies in an area which receives less than 160 cm of annual rainfall, and has a history of prolonged droughts. Water management had to be an important feature of any ancient settlement in this area, and the fact that the Harappans were acutely aware of the problem is clear from the large (c. 7 m deep) rock-cut cisterns that have been reported virtually all around the inner side of the outer wall of the settlement. They also used the two local seasonal rivulets—the Mandsar (outside the walled area to its north-north-west) and the Manhar (flowing through the south-eastern part of the walled area)—by building dams across them. Within the area (c. 714 m × c. 614 m) enclosed by the outer wall (mud-brick with a veneer of stone-blocks on the outer face), which has not survived all around but is 8.40 m wide in its south-eastern section, there are at least three separately fortified enclosures: a small ‘castle’ area with a ‘bailey’ or a lower adjunct by its western side, and a much larger ‘middle town’ to the north of this twin complex. The area to the east has no separate fortification and is called the ‘lower town’. A remarkably interesting feature of the plan is the presence of an open space of regular shape between the castle-bailey complex and the middle town. This has been thought to be a ceremonial ground. There were possibly two gateways on each side, of which two seem to have been excavated. From the brief reports published so far, it appears that the northern gate of the ‘castle’ which fronted the ‘ceremonial ground’ to its north was an elaborate complex: two chambers (separated by a passageway) set within the width of the fortification wall itself, and the landings and terraces associated with them. Both rounded and narrow-waisted polished stone pillar bases and parts have been found in this section. Thinner and straight monoliths with mushroom heads (1–2 m high) found standing amidst the complex of buildings to the east of the ‘castle’ are among many other briefly reported finds from this site. Streets, lanes, drains and houses have also been excavated.

An extensive and accomplished water management system gives Dholavira its unique place among the Indus civilization sites. This also shows that the modern climate of the area with its less than 160 cm of annual rainfall and frequent droughts was no different in the protohistoric context. It has been claimed that at least 16 water reservoirs were created within the city walls, covering 17 ha or 36 per cent of the walled area. Every effort was made to preserve rain water in an area where there is no perennial source of surface water and ground water is largely brackish. The rains in the catchment areas of the two streams—Manhar and Mansar—were dammed and the water diverted to reservoirs within the city walls. The reservoir area was c. 750 by 70–80 m along the northern and southern margins of the peripheral city wall and in the west it was c. 590 m long, with a width of 170 m in places. In the south-eastern corner there was a reservoir covering c. 5 ha. The reservoirs had 4.5 to 7 m wide bunds around them, protected by brick masonry walls. The natural gradient of the place was certainly used to create these reservoirs but deep troughs and depressions were also dug into the rock. This rock-cut tradition is unique at Dholavira. Brick-and-stone-built drains occurred mostly in the ‘castle-bailey’ complex. At least one of them was large enough to permit a standing human and most of them had surface apertures. These drains carried rain water to a receptacle for later use. The apertures served as air ducts to facilitate the easy flow of storm water. Household drains were linked to soakage pits.

Fig. 21 East gate of Harappan ‘castle’, Dholavira (Indian Arch.—A Rev.)

Fig. 22 North gate of the Harappan ‘castle’, Dholavira (Indian Arch.—A Rev.)

The cemetery area of Dholavira, which lies to the west of the fortified area, has thrown up at least two major surprises. First, there are rectangular burial pits lined with cist blocks. They do not contain any physical remains but are no doubt parts of a mortuary practice which can be seen much later in the megalithic burials. Second, there is a large, circular structure whose dome-shaped top is truncated to house the representation of a spoked wheel complete with its rim and hub. The space between the spokes is superficially filled with stone pieces and the hub portion has revealed a bowl buried in it. The details are unknown, but this circular structure represents a reliquary monument and antedates the stupa-building of the historic period.

Kuntasi

Excavated in 1987–90, this 2 ha site is situated on the bank of a small river, Jhinjhoda, at the edge of the Gulf of Kutch in Saurashtra and has been interpreted by its excavator as a Harappan emporium where raw materials like semi-precious stones and copper were processed. The nearest source of sweet water is a modern village c. 2.5 km away from the site. The river and the wells in the vicinity contain only brackish water. Yet, the site stood on the bank of the river, probably for the ease of movement. The meticulous excavation and clear reporting bring out the total character of the settlement: an outer and an inner fortification wall (the gap between the two is uneven, 15–25 m), both made of boulders set in mud and both more than a metre in width. The watch-tower in the south-western corner (roughly 8.5 m × 10.55 m) is also of the same material and originally 10–12 m or more high. This overlooked the river. On the eastern side the excavated gateway is complete with guard-rooms and passages. The structures inside were disposed around an open space fronted by a north–south stone platform (20.3 m × 3.8 m). Equally interesting is a multi-roomed structure which was found to contain kilns, furnaces, storage areas and a ramp going down to the river. The suggestion is that it was a workshop of pottery, beads and copper artefacts. Other fortified sites like Kuntasi occur in Gujarat, such as Pabumath, Desalpur, and Rojdi.

General Features of Harappan Settlements7

Within the common elements of fortification, types of structures, organized layouts, etc. there is a fairly wide range of variations. For instance, Mohenjodaro, Harappa, Kalibangan, Lothal, Banawali, Surkotada, Dholavira and Kuntasi—the sites where the basic settlement type is clear—are all different in detail. Second, there is a complete grip over the technical details. The fort layout down to the watch-tower, bastions, gateways and possibly even ditches was understood. There is no confusion about water disposal (drains with gradients, cess-pits, soakage jars) and water management (dams across the Dholavira rivulets, wells in many places) either. Third, the housing materials were also well understood: bricks of standardized measurements, stones set in mud-mortar and large-scale stone cutting and polishing where necessary (cf. Dholavira). Fourth, all settlements were integrated into the landscape and their characters hardly depended on size. The variation in size between Mohenjodaro and Lothal, or for that matter, Kuntasi, is high, but they retain the common features of organized layout, etc. Fifth, functional variations too are only to be expected; some like Kuntasi could be dominantly mere outposts to procure and process raw materials. In essence, the picture is not a flat one, although a proper three-dimensional one would need a lot more research.