Seals and Script

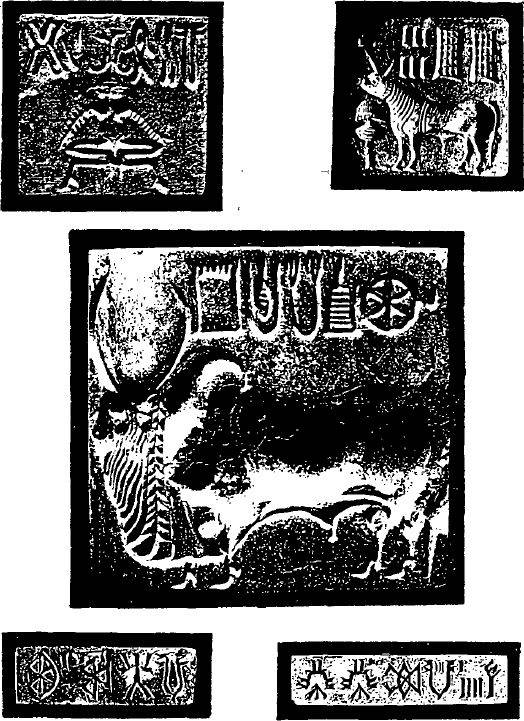

In 1998, the number of Harappan inscribed objects should be well past 3675, as suggested by Asko Parpola’s corpus of Indian and Pakistani collections published in 1987 and 1991. They are mostly seals and seal impressions, copper tablets, copper/bronze implements, pottery and other miscellaneous objects. The last category comprises a good number of ‘miniatures’ in terracotta, stone, faience and other materials. According to a list published in 1977, about 50 per cent of these objects have been found at Mohenjodaro and when combined with the number from Harappa, the percentage goes up to 87 per cent. The other listed sites such as Chanhudaro, Kalibangan, Lothal, etc. are much smaller and much less exposed than Mohenjodaro and Harappa. In 1931, Ernest Mackay published 10 different types of seals at Mohenjodaro: cylindrical (?), square with perforated boss on reverse, square with no boss and frequently inscribed on both sides, rectangular without boss, button with linear designs, rectangular with perforated convex back, cube, round with perforated boss, rectangular with perforated boss, round with no boss and inscribed on both sides. It is the square/rectangular type which is the most common and thus forms the diagnostic type. Cylindrical seals are characteristic of the Mesopotamian and Persian world whereas the round type is diagnostic of the Gulf area. The presence of such types in limited quantities and often with Harappan motifs suggests a cultural interaction. The largest square seal of Mohenjodaro is a little more than 6.35 cm square. The more usual ones are around 2.54 cm square and examples of 1.27 cm square also are known. The seals are generally made of steatite but there are a few cases of silver, faience and calcite. Copper and soapstone specimens are known from Lothal. Most of the steatite specimens carry ‘a glaze-like coating of a smooth glassy-looking substance’. The coating was possibly intended to cover the blemishes before the engraving was done, and afterwards baked in a kiln to ‘whiten and improve the outside; for many of the broken seals show that the colour of the stone of which they were made was originally grey’. The number of actual seal impressions is much less than that of seals, and this, along with the fact that the seals are found abraded only at the edges and not inside, has led in certain quarters to the speculation that they were used more as amulets and/or identification marks than in administrative and economic life. The presence of one or two examples of ‘amulets’ had, in fact, been noted by Mackay at Mohenjodaro, where the interior of the seal had been carefully hollowed out to form a compartment which was ‘formerly closed by a sliding cover that fitted with grooves cut in the two sides of the seal’. Mackay wrote:

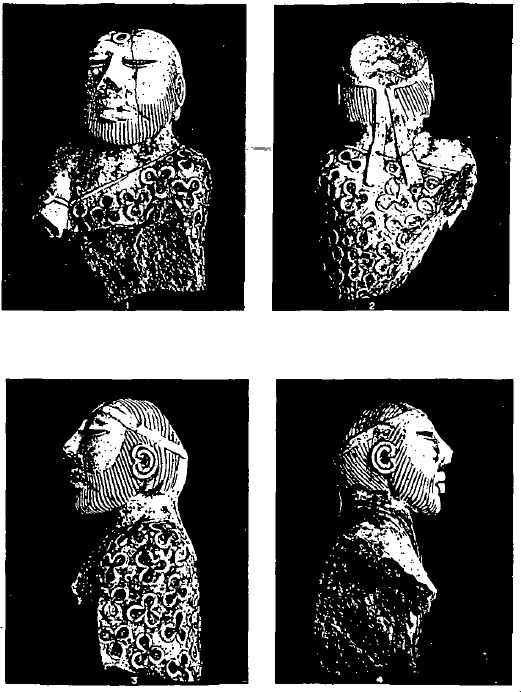

Fig. 23 Harappan seals

Personally, I am of the opinion that these seals were used almost exclusively for stamping sealings of clay, which, unless it were baked or of a special quality, would be unlikely to survive in a site that is, or has been, dump…. None of the seals of other ancient civilizations resemble those that have been found at Harappa and Mohenjodaro, either in their devices or the pictographs they bear, or even in shape.

The animals represented on the seals include the so-called unicorn (one-homed mythical animal), short-horned bull (in every case a low manger, flat-based and with concave sides, in front), buffalo (its nose sniffing the air), Brahmani bull (with its characteristic dewlap and hump), rhinoceros (a manger/cult object in front), tiger, horned tiger, elephant, horned elephant, fish-eating crocodile, antelopes, hare, etc. There are also mythological motifs, composite animals and plant forms. There are grounds to believe that the seals were generally manufactured at the site where they have been found, with perhaps a limited quantity of better-fashioned specimens being left for groups of superior craftsmen and inter-site trade. At Mohenjodaro, seals, as Mackay pointed out, ‘were found in the houses of the poor and rich alike’, and at Mohenjodaro again, a limited study has led to the inference that there was a decrease in the number of seals and the variety of its icons and shape in the upper levels which witnessed an increase in the number of inscribed copper tablets.

Many attempts notwithstanding, the Harappan script is still undeciphered, and there is nothing to choose between the different linguistic hypotheses proposed in connection with the attempted decipherments. ‘Scientific paradigms’ of the Euro-American scholars (cf. Possehl 1996: 21) in this matter are no worse or better than the reasonings offered by Indian scholars. The basic signs are about 400 to 417, according to a concordance published by the Archaeological Survey of India. The calculation of sign frequency is remarkably interesting:

|

over 800 occurrences: 1 sign; |

over 50 occurrences: 46 signs; |

|

over 200 occurrences: 6 signs; |

over 20 occurrences: 86 signs; |

|

over 100 occurrences: 24 signs; |

over 10 occurrences: 100 signs. |

Apparently, only a small proportion of signs was regularly used and this suggests that our idea of the writing system as a whole is incomplete and that there could be a whole range of texts on perishable materials (cf. Possehl 1996: 63). That the Indus writing system may throw up surprises in future is amply indicated by the presence of an inscription of nine letters found on the floor of the western chamber of the north gate excavated at Dholavira: each letter is c. 37 cm high, c. 25–27 cm wide and ‘made by arranging cut pieces of a milk-white crystalline material’. They were obviously affixed to a wooden or similar board and put up as a kind of ‘hoarding’/‘notice’. This shows that the extent of Harappan literacy may be much more than we are willing to admit on the basis of the inscribed material in non-perishable materials. With exceptions, the direction of writing was from right to left.

Pottery

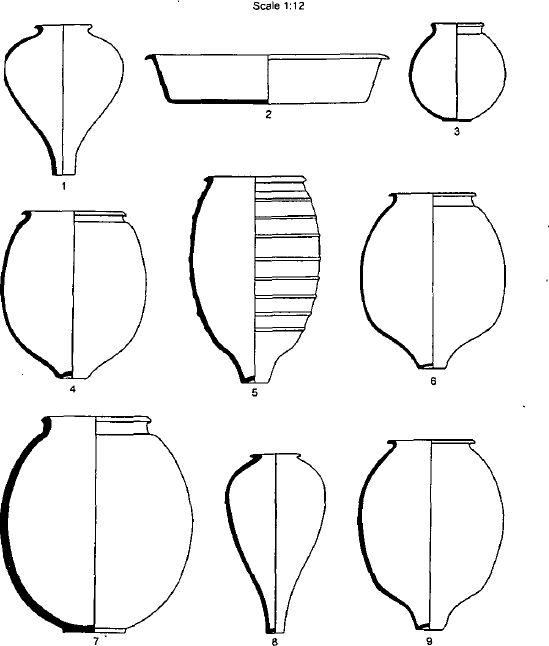

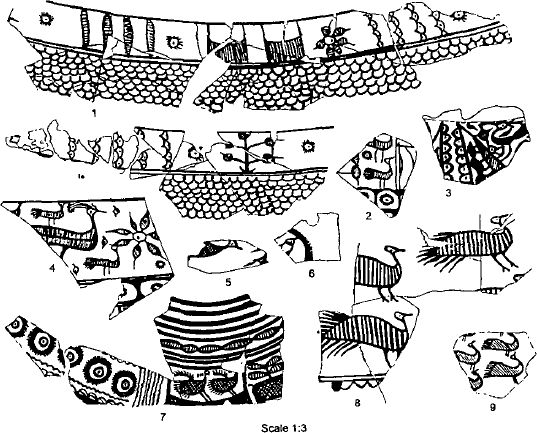

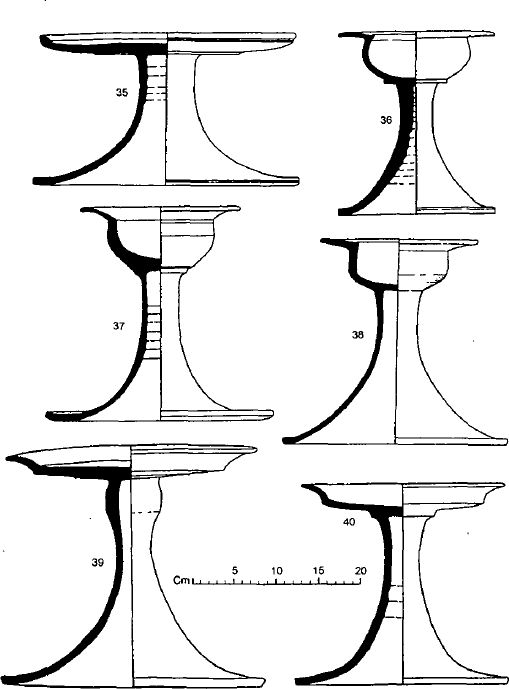

The categories of black-on-red, red, grey, buff and black-and-red (only in Gujarat) sum up the general types. In the painted varieties (only 10 per cent of the total pottery material at Kalibangan, which is broadly indicative of other sites as well), there are mainly black paintings on red surface, chocolate/purple black on buff and white/creamy on the black-and-red. There are both fine and coarse fabrics. Slip is present and absent almost in equal proportion. There was red oxide slip in red pottery and the other slips were creamy with different hues and chocolate/purplish. Some had two slips, and some were given a wash. The thickness of the fabric varies too. Clay generally is well-levigated, with sand, lime or mica as tempering materials, although not in every case was the clay tempered. Wheel was used, possibly foot-wheel in Sind and Punjab and hand-operated wheel elsewhere. The threadmarks at the bottom indicate that the wheel rotated both clockwise and anti-clockwise. Some were made in parts and later luted together on or off the wheel. The designs are generally geometric but there are naturalistic patterns in some cases. Paintings are in registers, not usually below the waist of the vessel, but exceptions occur. The incised designs are uncommon. Cord-impressions are found on storage jars or basins. A few pots carry barbotine decoration. Reserved-slip pottery forms a distinct group and is more frequent in Gujarat than elsewhere. Pots were fired in closed kilns, of which some examples have been excavated at Mohenjodaro and elsewhere. These kilns are vertical up-draught kilns, but there is no reason why open-fire baking kilns could not also have been used. The shapes are diverse, ranging from large storage jars to miniature pots. Some shapes, such as vases with an S profile, goblets with scored middle portion and pointed/incipient bottom, perforated jars, jars with globular profile and narrow bottom, dish-on-stands, etc. are distinctive. There are cases of zoomorphic types too. In Gujarat a distinct type is the stud-handled bowl. The manufacturing areas of potters have been traced on the surface at Mohenjodaro, which seems to indicate a common pattern for other sites as well. In Gujarat two types of pigment, manganese-rich and iron-rich, have been traced in the slip of Harappan pottery. The mode of pottery distribution has not yet been closely studied.

Fig. 24 Harappan pottery (a few shapes)

Fig. 25 Designs on Harappan painted pottery

Fig. 26 Harappan dish-on-stand from Kalibangan (Indian Arch.—A Rev.)

Lithic Industry

Recent research has brought to light a large number of Harappan stone quarries and traces of workers’ settlements in the Rorhi hills of Sind, and one such quarry has also been dated (2466–2201 BC calibrated range). It has also highlighted the complex and organized character of the operation behind the manufacture of large chert blades found at many Harappan sites in the Indus valley and elsewhere. For instance, the study of the assemblage at site 480 identified two working stages in this particular workshop: one connected with the production of blades more than 8 cm long and the other with the reuse of cores abandoned in the earlier operations for the preparation of ‘smaller-sized bladelet cores’. In the first case, the estimate is that at least 2000 blades were exported from the site. Another point which emerges is the possibility of using a metal point for pressing blades off the body of cores, along with the usual pressure-flaking technique which does not involve the use of metal points.

As already noted, lithic flakes and cores occurred in abundance in most of the houses of Mohenjodaro, and in this context it is logical to surmise that at least secondary preparations for specific blade-based tools took place in individual households, including some blade-production. Cherts, not brought from the Rorhi hills, were also used at Harappan sites, and in such cases the blades are smaller. There is also proof of the presence of a specialized miniature-blade preparation at Mohenjodaro. ‘Crested ridge’ blades, i.e. the blade-like lengths taken out of a core before regular blades are taken out of them occur too.

At Lothal the excavator’s inference is that the ‘thousands of parallel-sided blades’ found at the site served primarily as domestic pen-knives and sickle-blades. He admits the possibility of some of these blades having been imported from the Rorhi hills, but he also suggests the Kaladgi series of rocks in the upper Krishna valley as a source of raw material in this connection. In addition to the organized production in areas like the Rorhi hills, the Harappans could also have obtained their lithic industry from contemporary hunter-gatherers. In Gujarat this possibility is strong.

Metallurgy

There is nothing tentative about Harappan metallurgy either in its range of tool types and other objects or in the variety of both alloying patterns and metals used. The catalogue of copper objects from Mohenjodaro is adequately representative: vessels (generally made by hammering single sheets of metal, but also cases of manufacture in two parts which were subsequently luted together; some could be cast as well), axe (both long and narrow, and short and broad sub-types), arrowhead, knife or dagger, sword/dirk, razor, saw, sickle-shaped blade, fish-hook, chisel, awl and reamer, needle, kohl-stick, drill, bolt, plumb-bob, scale-pan and beam, mirror, spatula, finger-ring, ear-ring, bangle, jar-handle, piping, shield-boss (used as patches of some kind), bull, bird, terminals, spacer, bead, casting, chain, and the famous dancing girl from the site. The details of typology do not interest us here, but as a group this is a distinctive assemblage without specific parallels. Pins with single or double spiral heads, which were once thought to have been more common in west Asia, have now been found at a number of sites, including Manda in Jammu, Ganeshwar in the Aravallis of Rajasthan and Surkotada in Kutch. Shaft-holed axes are uncommon, but a terracotta model of the type occurs in the lower levels of Mohenjodaro.

To some extent, smelting of metallic ores took place in settlements, as the finds of copper ores, slag and crucibles at Mohenjodaro indicate. More commonly, they were perhaps smelted near the pit-heads. The alloying pattern is as follows:

|

TABLE V.1 |

|

|

The variety of alloys is distinctive and so is the emphasis on a pure copper tradition which, according to Indian tradition, is ritually pure. Copper must have come primarily from the Aravallis in Rajasthan and Gujarat which could also supply other metals, including zinc and lead ores mixed with silver. Another major source was the rich copper deposits of Baluchistan and presumably Afghanistan. The nearest source of tin is the Tosam area of modern Haryana, although some tin could also have come from north Afghanistan and central Asia. Gold, of which there is a substantive amount of jewellery from Mohenjodaro and other sites, could have been obtained by panning river sands for gold, or they could have come from the auriferous deposits of Andhra and Karnataka. Arsenic was obtained from lollingite ores, some amount of which has been obtained at Mohenjodaro. Zinc ores occur in abundance in Rajasthan. Two Lothal objects contain 39.1 per cent and 66.1 per cent iron and the latter can be called an iron object (a fragment in this case). Some familiarity with iron-smelting may be assumed, at least in the case of the Gujarat Harappans. As small bird and animal figures in copper and the figurine of the dancing girl indicate, the lost-wax process of making metal objects was widely practised.

Miscellaneous Arts and Crafts

Ordinary household items like saddle querns, mullers, pounders, bowls, etc. must have had a separate group of craftsmen just as there are such groups even today. The processing of semi-precious stones—agate, carnelian, onyx, jasper, plasma, crystal and others—was done by bead-makers who had their own workshops. At the bead-making factory excavated at Lothal nearly 800 finished and unfinished beads were found, along with the evidence of a kiln which used thin burnt-brick walls with mud-plaster and was ovoid in plan (c. 1 m high and c. 1.5 m long) with four interconnected flues in the lower chamber so that fire could touch the earthen bowls containing pebbles and beads. Because of the continuity of bead-making industry in the modern times, it has been possible to get a good idea of how beads of semi-precious stones were manufactured, right from the collection of stone nodules to the final polishing. Etched designs were put on some carnelian beads by first immersing the designed beads in a plant-derived alkaline substance and then heating them for the absorption of the alkali by stone. Some beads like the long barrel-cylinder beads in translucent red carnelian or those made of moss agate were possibly considered very precious because one would require a large quantity of raw material to make them. Micro-beads made of steatite paste which was made hard by heating are a distinct Harappan feature, and so are the beads made of faience which is obtained by amalgamating lime with quartz at high temperature. Conch-shells were widely used for bangles, etc. just as they are used now. Ivory was used generally for beads and gamesmen, and although bone was used for beads, its more common use was for making awls and pins. Varieties of gold and silver jewellery and silver vessels, especially from Mohenjodaro, Harappa and Lothal, indicate the emphasis placed on these precious metals. The main types of gold ornaments comprised bracelets, necklaces, armlets, pendants, ear-studs, beads, bosses, brooches and fillets. Direct evidence of cotton has not survived except as impressions. Evidence has also been obtained of the firing of a class of terracotta bangles (called stoneware bangles) at high temperature.

Weights and Linear Measures

A.S. Hemmy’s observation on the identical weights found at Mohenjodaro and Harappa are worth quoting:

These weights are with hardly an exception uniform in shape, a rectangular block, cubical in the smaller sizes, and in the great majority of cases of the same material—a hard chert. They are well finished polished faces and occasionally with bevelled edges. They are made with much greater accuracy and consistency than those of Susa and Iraq. The system is binary in the smaller weights and then decimal, the succession of weights being in the ratios 1. 2, 1/3 × 8, 4, 16, 32, 64, 160, 200. 320. 640, 1600.8

A shell object from Lothal has been interpreted to be a compass for measuring angles, but perhaps more convincing is the evidence of a broken piece of ‘scale’ made of shell from Mohenjodaro: 1.57 cm wide, 5.29 cm long and 0.67 cm thick.

The dividing lines are cut with a fine tool into subgroups of 5 divisions marked with a dot and circle, also suggesting the use of the decimal scale between any two dots or circles…. The estimated distance between the dot and the circles is believed to be 33.53 mm. This distance was termed ‘The Indus Inch’ when the British ruled India and inch was 1 /36th part of the legal linear unit of length—yard.9

Crops and Domestic Animals10

In an area spreading from Baluchistan to the upper Ganga-Yamuna Doab and from Jammu to Gujarat there has to be a strong diversity of agricultural practices and animal husbandry. There is no reason why it should be any different in the Harappan context, especially when there is no firm evidence of climatic change since then. The presence of irrigation and plough can both be taken for granted. We have argued strongly in favour of the presence of irrigation in an earlier section, and the find of an early Harappan ploughed field at Kalibangan and a terracotta model of a plough at Banawali are conclusive as far as the idea of plough agriculture is concerned.

|

TABLE V.2 |

|

|

Mohenjodaro |

wheat, barley |

|

Chanhudaro |

wheat, barley, mustard |

|

Harappa |

wheat, barley, peas (Pisum arvense), sesame (Sesamum indicum), rice, and millets |

|

Banawali |

basically unpublished, but wheat reported |

|

Kalibangan |

wheat, barley, chick-pea (Cicer arietinum), pea (Pisum arvense) |

|

Rohira (district Sangrur, Indian Punjab) |

early Harappan context—modern babul (Acacia), kareel (Capparis aphylla), jhau (Tamarix dioica). teak (Tectona grandis), toon (Cedrella toona) khirani (Manilkara hexandra), and deodar (Cedruts. deodara) woods; modern henna or mehendi (Lawsonia inermis) and grape-vine (Vinus vitifera); mature Harappan context—in addition to babul and jhau trees and grape, khejri (Prosopis spicigera) and sheesham (Dalbergia sp.) woods, ‘ber’ (Zizyphus jujube) and ‘harsingar’/ ‘shephalika’ flower |

|

Mahorana (district Sangrur, Indian Punjab) |

in addition to some of the things found at Rohira, an important find is hyacinth bean (Dolichos lablab) which needs ‘frequent irrigation’ |

|

Hulas(Saharanpur district, UP Doab) |

wheat, barley, wild (Oryza rupifogon) and cultivated (Oryza sativa) rice as impressions on potsherds. sorghum and ragi millets, cotton, castor, almond, walnut and a variety of pulses including Dolichos biflorus, Pisum arvense, Pisum sativum, Lathyrus sativas, Vigna radiatus, and Vigna mungo |

|

Lothal |

babul, siris (Albizzia sp.), teak (Tectona grandis), haldu (Adina cordifolia) androhini (Soymida febrifuga) woods; rice (identified with certainty in the Lothal report), and possibly millet and sesame |

|

Surkotada |

mainly Italian millet (Setaria Italica) and ragi millet (Eleusine coracana), in addition to a large variety of wild grass and plant species |

|

Shikarpur(Kutch) |

wheat, ragi millet and Italian millet in addition to woods inclusive of silk-cotton (Salmalia malabarica) and sal (Shorea robusta) |

|

Rojdi |

a variety of millets inclusive of ragi, Italian and sorghum millets and a variety of wild grasses and plants, some of which can be used as fodder |

|

Kuntasi |

wheat, barley, a variety of millets including Panicum, Italian and Kodo millets, and Job’s tears the seeds of which were probably used for beads |

|

Shortughai |

barley, wheat, Panicum millet, lentil, pea, almond. pistachio, grapes and linseed |

The list is by no means comprehensive and does not discuss the technicalities involved, but it offers a rounded picture of the variety of crops available to the Harappans. On the basis of the early occurrence of millets in the Gujarat sites and of Panicum millet in the early level of Shortughai, there is no reason to believe that they were introduced late in the Harappan sequence or served the purpose of a ‘green revolution’ crop. Also, millets were an integral part of the Sind sites as they were in pre-industrial modern Sind, although no direct evidence has yet emerged. All the major crops of the subcontinent were known along with a variety of pulses. The trees inclusive of deodar, teak, sheesam, sal and babul suggest a landscape with which we are familiar, and if a particular tree is missing now in a particular area, that may simply be due to the denudation of the landscape by humans. Grapes were known and so were henna or mehendi and the harsingar or shephalika flower. As noted earlier, cotton was cultivated too.

Domestic animals comprised cattle, buffalo, sheep, goat, pig, camel, elephant, dog, cat, horse and others. One may include ass in this list. Horse occurs at Harappa, Mohenjodaro, Lothal, Surkotada, Kalibangan and Kuntasi and has been identified as such by many scholars with expertise in animal identification. There are wild varieties of sheep, goat and possibly ass and pig, and a number of deer varieties. There are also turtles and fish, and one of the most significant recent hypotheses in this field is that dried sea fish from possibly the Makran coast used to be traded as far upstream as Harappa. The culling of cattle herd surplus was practised, as the pronounced cluster of cattle deaths between the two and five years of age at Oriyo Timbo in Gujarat suggests. A recent study suggests an organized exploitation of molluscs for food, at least in Gujarat.

Trade11

The explicit evidence of Harappan internal trade is the occurrence of various raw materials found at Harappan sites in different regions. In the context of Gujarat alone the sitewise distribution of raw materials (prepared before Dholavira excavations) includes steatite, shell, carnelian, jasper, gold, amazonite, quartz, onyx, sardonyx, flint/chert, chalcedony, hornblende, syenite, silver, alabaster, ivory, agate, lapis lazuli, crystal, bloodstone, opal, plasma, sandstone, granite, schist, felspar, dolerite and copper/bronze—28 items. The sheer fact of their being found at different Gujarat sites makes the economic world behind it—a world of raw material procurement, processing, manufacture of objects and their distribution—obvious. Gujarat is only one area of Harappan distribution; if all the areas are taken together, this world assumes great proportions.

(1) Emanating from the Karachi region, one line of movement went through Kohistan and, following broadly the western banks of the Indus river, reached the Larkana district where Mohenjodaro was located. From Larkana, the Indus was crossed to reach Chanhudaro and the eastern segment of Sind. (2) There was also a route which passed from the Sukkur/Rorhi hills to Harappa on the one hand and the Ghaggar/Hakra stretch on the other. (3) That the Indus river was also used for some amount of traffic is a distinct possibility, although this was not the sole route in the Sind region.

Sind and Baluchistan seem to have been interacting both over land and along the coast with Gujarat. (1) The eastern segment of Sind … mediated a route between the Sind plains and Gujarat through Kutch and Kathiawar. (2) A sea route, hugging the coast. … also appeared….

Land and riverine routes connected the Bahawalpur and central Indus region with Rajasthan. (1) One land route went from the Multan-Montgomery region to Bahawalpur, from where the Anupgarh-Lunkaranser-Bikaner-Jhunjhunu axis was traversed. (2) An important link was the Multan–Pugal–Bikancr route. (3) There was also a land route from Ganeshwar to Sothi–Bhadra via Neem-Ka-Thana and Khetri. (4) That the Kantli river was mediating traffic between Rajasthan and the regions to its north and west as well is likely….

Between Sind and east Punjab, there were two major routes that passed through the Bahawalpur region. From there, (1) one branched off to the Upper Sutlej region. going through Bhatinda and Ludhiana districts till the edge of the Himalayas where Manda was located. (2) The other, after passing the Ghaggar–Drishadvati divide of central Punjab, went to Hissar and Jind, reaching Rohtak from where one branch crossed the Yamuna to Meerut and the other proceeded to Gurgaon.

East Punjab also shared a very close interaction with Rajasthan…. (1) A branch of the Kantli river, which is now extinct, acted as a channel between the Sikar district and Hissar. (2) Another river, the Dohan, … also went to Haryana. (3) The land route went from Ganeshwar through Rajgarh from where one branch went to Bhiwani … and the other reached the Sothi–Bhadra region.

The foregoing summation of major internal routes linking the different areas of the Harappan civilization, which is based on a careful study of the distribution of various raw materials at different sites and their possible sources, highlights more than anything else the scale and importance of Harappan internal trade. The evidence of Harappan external trade has been found principally in north Afghanistan, Turkmenistan, north and south Iran, the islands of Bahrain, Failaka and the Oman peninsula in the Gulf, and north and south Mesopotamia. There are finds of ‘Indus’ or ‘Indus’ -related objects in all these areas. Similarly, there are non-Indus, externally derived objects in the distribution area of the Indus civilization. All these objects can immediately be put in different categories. The most explicit items are two types of ‘Indus’ beads—etched carnelian and long barrel-cylinder carnelian types—and square/rectangular Indus seals with script or the presence of Indus script on pottery. They occur in virtually all areas. Along with this are less direct items, such as pottery, ‘Indus’ motif on local seals, objects of ivory, miscellaneous terracottas, etc. all of which suggest a familiarity with the ‘Indus’ area. On the other hand, within the ‘Indus’ area there are some seals of external affinity, steatite/chlorite vessels with specific designs, some externally derived motifs, etc. The details of the typology and context of all these objects and motifs have drawn much discussion. Such details are not necessary in the present context, but a few general observations may be made. Everywhere outside the subcontinent the relevant finds are found along well-defined trade routes. For instance, to reach Shortughai in north Afghanistan the traders had to be familiar with the orientation of the different passes across the Hindukush. In Iran the Baluchistan–Kirman–Fars plain–Luristan–Khujestan route of south Iran and the northern Iranian route through Kandahar, Girishk, Herat (these three places in Afghanistan), Meshed (north-east Iran), Hissar (north Iran) and beyond along the southern slope of the Elburz range were both used. These routes were overland routes to Mesopotamia. Turkmenistan was reached either via the Shortughai and Herat areas or across the Kopet Dagh range from Meshed. The southern Iranian route also offered access to the Gulf, but the Gulf area could be reached by sea, and thus there was a maritime access to Mesopotamia as well. The maritime route could have touched the Makran coast, but more logically, ships went out of Gujarat to the Oman peninsula taking the help of monsoon winds. This is an area where the ‘Indus’ presence is sharply visible, down to pottery and the presence of ‘Indus’ designs on presumably some local pottery. Ras-al-Junayj on the Oman coast lies in an area which provides the landfall for ships coming from the Gujarat side, and significantly, the place has yielded indisputable ‘Indus’ artefacts. In the ‘Indus’ area, cylinder seals of the Mesopotamian, Iranian and central Asian world occur notably at Mohenjodaro and Kalibangan but show ‘Indus’ motifs. A ‘Gulf’ seal was found on the surface at Lothal and a seal with a ‘Gulf’ motif has been found at Bet Dwaraka. On the other hand, several ‘round’ seals of Gulf origin bear Indus motifs and script not merely in the Gulf itself but also in Mesopotamian sites like Ur and the Iranian Khujestan site of Susa. By and large, the whole region seems to be tied by a network of both overland and maritime trade. This conforms to a pattern with which we are familiar in much later historical contexts, and it may not be wise to read too much in this trade, as several scholars have done. For instance, the term ‘Meluhha’, which occurs in Mesopotamian literature, may not denote exclusively the area of the Harappan civilization, as some scholars have hypothesized. A better explanation is that the term could denote the whole area to the east of Khujestan and its adjacent area in Iran and thus possibly included the ‘Indus’ area as well in its scope. There could also be settlements of Harappan traders in Mesopotamian cities; there have been settlements of Indian traders in the entire region from central Asia to the Gulf in the historic periods including the present.

Goods must have been regularly traded over this whole area, and it is possible that in this process, especially in the context of the Oxus-Indus interaction zone, the seasonal nomads of the Hindukush region like the modern Powindahs played a role. In the scheme of Harappan external trade, north Afghanistan like the Gulf region seems to have had a special niche. Miscellaneous Harappan or Harappa-related objects have been found in various looted graves of the Bactrian region and at a site called Dasly. On the other hand, indisputably rich trade goods with Bactrian material have been found in Quetta, Mehrgarh and Sibri, all in the Bolan pass region. These finds, according to some scholars, belong to the end phase of the Indus civilization, but there is really no special reason why it cannot date from its mature phase.

Religion12

The archaeological evidence of an ‘Indus’ religion was comprehensively discussed in the first volume of the Mohenjodaro report in 1931, and although many scholars have expressed disagreement with it, the disagreements are basically in the matter of detail and do not really affect the basic structure offered. In view of the female terracotta figurines found at sites, a belief in the different types of mother goddess may be taken for granted. A small sealing from Harappa shows a plant coming out of the womb of a woman. Another representation on a seal has been interpreted as ‘a prototype of the historic Siva’. An apparently three-faced god with horned head-dress sits on a low Indian throne in a yogic posture, with legs joined heel to heel below him and the arms resting on the knees on either side. The arms are fully covered by bracelets, three on each arm being larger and more prominent than the rest. The chest is covered by a row of necklaces disposed in the form of an inverted triangle. There are two bands across the waist and it looks as though the figure is shown ithyphallic. There is an ibex/deer/goat below the throne. A number of animals (elephant and tiger on the left and a rhino and a horned bull/buffalo on the right) and an inscription occur as a background. The horned head-dress, association with animals, three faces, ithyphallic state and the yogic posture mark it out as a deity who has a better chance to have been a prototype of Siva than anything else. ‘Siva’ is also writ large on the phallic stones found at Mohenjodaro and Harappa where there are also ring-stones on the model of female signs. Further, a standing nude figure in a tree with a supplicant below suggests a tree deity, and another seal shows a row of seven standing females, recalling the ‘seven mothers’ of the later Hindu tradition. The life-like rendering of animals shown on seals may denote some sanctity associated with these animals. At Kalibangan, the offering-pits found on the top of platforms in the western mound and the offering-pits found in the ordinary dwelling places of Lothal, Banawali, etc. show a pattern of sacrifice which many practising Hindus will recognize. We do not suggest that Hinduism, as we find it today, was there in the Indus civilization. All that we would say is that some later features of Hinduism have been echoed by ‘Indus’ finds, and thus this civilization is likely to have contributed to the stream of ‘sanatana dharma’ or traditional religion of the modern Hindus.

Sculptural Art13

The number of stone and bronze sculptures is limited, although on the whole there is some justification for claiming a multiplicity of art styles and postulating the roots of the much later historic art of the subcontinent in them. This art form is a product of the Indus civilization itself; its roots cannot be traced in the pre- ‘Indus’ period which yields only stylized terracotta female and animal figures. The major specimens of Indus sculpture in stone are: (1) a head from Mohenjodaro, i.e. the famous Sramana head (the surviving portion is 17.78 cm); (2) a headless figure seated in a meditative posture (41.91 cm), also from Mohenjodaro; (3) the torso of a male from Harappa (about 10 cm high, as preserved); (4) the torso suggesting a dance posture from Harappa (about 10 cm high, as preserved); (5) a seated ibex/ram (49 cm long, 27 cm high and 21 cm wide), unprovenanced but certainly of the Indus civilization; (6) a broken, seated male figure from Dholavira (height unpublished). In addition, there are a few miscellaneous, severely mutilated ‘heads’ and ‘seated figures’ from Mohenjodaro. In bronze there is only the figure of a dancing girl from Mohenjodaro (11.25 cm high). There are certainly bronze objects from various sites, but they cannot be put in the category of high art. The Sramana head, with its eyes half-closed and focused on the tip of the nose, the shawl across the chest and below the right arm and the trefoil design of the shawl, leaves no doubt that here we are faced with the representation of a sacred person. The seated Mohenjodaro figure, again with a shawl draped over the left arm and below the right, suggests both a sense of volume and careful modelling, although the hands in this case cannot be called properly formed. The red sandstone torso from Harappa shows sockets for neck and shoulder and holes for nipples and possesses a remarkable similarity with historical sculptures in its smooth modelling, sense of volume, tautness and power. The grey stone figure in a dancing pose from Harappa suggests the posture of Nataraja, a dancing posture of Siva. The bronze dancing girl from Mohenjodaro is not really shown dancing but her nudity and confident posture with a leg thrust in front and arms resting on the knee and the left side of the waist put her in a class apart.

Fig. 27 Sramana’ figure from Mohenjodaro

As compared to the earlier periods, the painting style of the mature Indus civilization is more confident, lush and altogether suggestive of a vibrant community. The brushwork of some painted sherds from Gujarat is reminiscent of swiftly done sketches, and in one case at least, where a deer is shown turning its head, the painter could be telling a folk story.

Skeletal Biology

Human skeletons have been unearthed at various sites, including Mohenjodaro, Harappa, Lothal, Kalibangan and Dholavira. Technical studies have no doubt been published on some of them, but the inferences which one may draw about the people’s health on the basis of such studies are still limited. On the basis of the skeletons discovered in the early excavations at Harappa, P.C. Dutta of the Anthropological Survey of India outlined some parameters of their skeletal biology:

The people were, on the average, moderately long headed, having an average cranial capacity, average medium-high vault of head in relation to the length of the head, and a relatively high vault in relation to the breadth of head. The calvarium shapes were mostly ellipsoids to spheroids in males and ellipsoids to ovoids in females. The forehead was moderately broad and highly receding in males, whereas it was fairly narrow and vertical to slightly receding in females. The upper face of the Harappans was medium or low mesen shaped with varying degrees of alveolar prognathism. The noses were highly mesorrhine or moderately platyrrhine, and the bridge of the nose was frequently concave, depressed at the base. Orbits were medium high. These people had moderately broad hard palates with paraboloid dental arcades. Though the lower-jaw width was short in both sexes, the jaw itself was relatively robust and larger in males than in females. The Harappans were above average in body height.14

The idea of investigating the genetic continuity of the Harappans led Dutta to examine some modern crania in the anatomy department of the Christian Medical College, Ludhiana (about 160 km to the east–south-east of the site of Harappa) and he tentatively reaches the conclusion that the results ‘suggest a genetic continuum between the Harappans and the present-day people of the region’. This continuity of population has also been suggested by a brief mention of the results of unpublished studies on the skeletons excavated at Dholavira.

Among the diseases, thalassaemia and sickle-cell anaemia have been supposed to exist and both have been linked to malaria. At least one person at Harappa died of dental abscesses. Further, significant differences in a tooth condition—linear enamel hypoplasia—were found between the males and females, and this has been taken to ‘suggest that a greater percentage of women were stressed by nutritional deprivation and/or serious illness than were men’. Nutritional deprivation of women is still common in many Indian households. The possibility of skeletal studies, including the studies of ancient DNA, are immense, down to the reconstruction of the actual living face. From this point of view the study of ancient Indian skeletal biology is still in its infancy.