It is accepted,

The angry defiance,

The challenge of battle!

![]()

THE MORNING OF 15 October 1886 was drizzly, and the East River heaved dull and gray as Roosevelt’s ferry pushed out from Brooklyn. On Bedloe’s Island, far across the Bay, he could mistily make out the silhouette that had been tantalizing New Yorkers for months: an enormous, headless Grecian torso, with half an arm reaching heavenward.1 But he probably gave it no more than a glance. His mind was on politics, and on this evening’s Republican County Convention in the Grand Opera House. He was curious to see who would be nominated for Mayor of New York. The forthcoming campaign promised to be unusually interesting—so much so he had delayed his departure to England until 6 November, four days after the election.

For the first time in the city’s history, a Labor party had been organized to fight the two political parties. What was more, it had nominated as its candidate the most powerful radical in America. Roosevelt had met Henry George before—on 28 May 1883, the same night he first met Commander Gorringe2—and the little man had hardly seemed formidable. Balding, red-bearded, and runtlike, he was just the sort of “emasculated professional humanitarian” Roosevelt despised.3 Yet George was famous as the author ofProgress and Poverty (1879), one of those rare political documents which translate sophisticated social problems into language comprehensible to the ghetto. So simple was the book’s language, so inspirational its philosophy to the poor, that millions of copies had been sold all over the world.4

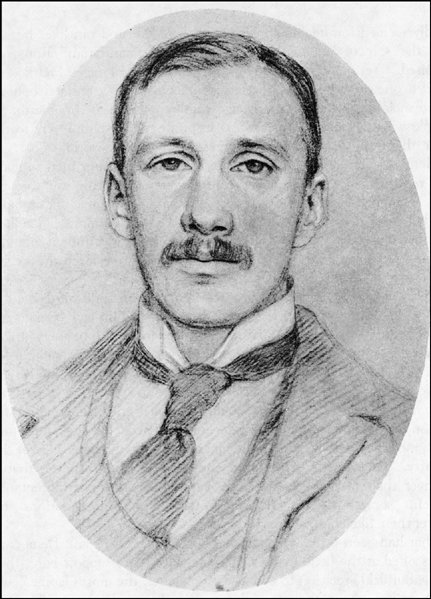

“A pale young Englishman … with a combination of courtliness and inquisitiveness.”

Cecil Arthur Spring Rice at thirty-five. (Illustration 14.1)

Henry George argued that because it takes many poor men to make one rich man, progress in fact creates poverty. The only way to solve this, “the great enigma of our times,” was to have a single tax on land, as the most ubiquitous form of wealth. Thus, the more a landlord speculated on Property, the more he would enrich Government, and the more Government would repay Labor, which had produced the wealth in the first place.5

Up until 1886, George had been content to propound his single-tax philosophy in print and on lecture platforms (for all his lack of glamour, he was a blunt and effective orator). But the recent rash of angry strikes across the country6 persuaded him that it was time to submit his principles to the ballot. New York, with its abnormally wide gulf between rich and poor, was the obvious place to start. George let it be known that if thirty thousand workingmen pledged to support him for Mayor, he would run on an independent Labor ticket. Thirty-four thousand pledges flowed in, to the amazement of politicians all over the country. “I see in the gathering enthusiasm [of labor] a power that is stronger than money,” George crowed delightedly in his acceptance speech, “something that will smash the political organizations and scatter them like chaff before the wind.”7

That had been on 5 October, and both Republicans and Democrats had scoffed at the little man’s hyperbole. Pledges of support bore, they knew, but fickle relation to actual voting figures: the most George could hope for was fifteen thousand. But now, only ten days later, George’s strength was increasing at a truly phenomenal rate. Professional politicians were seriously alarmed. If George, by some political fluke, captured City Hall, he would wield greater power than any former Mayor—thanks to legislation sponsored in 1884 by none other than Assemblyman Theodore Roosevelt.8

The latter’s first question, when he stepped off the ferry into a group of New York reporters, was about their latest estimate of George’s voting strength. The answer, “20,000, and probably much more,” surprised and flurried him. After remarking, irrelevantly, that he himself was “not a candidate” for Mayor (not even the most imaginative journalist thought that he might be), Roosevelt hurried uptown to the Union League Club.9

![]()

DOUBTLESS HE INTENDED to attend the Republican County Convention as an observer. But during the afternoon he was visited by a group of influential Republicans, who, on behalf of party bosses, asked if he would accept the nomination for Mayor. This bombshell took him completely by surprise.10 As a loyal party man, he could not refuse the honor; as a loyal (and still secret) fiancé, he could not reveal that he had a transatlantic steamship ticket in his pocket. Edith was looking forward to a leisurely, three-month honeymoon in Europe after their wedding, and would surely resent being hurried back to New York so that he could prepare to take office on 1 January. Moreover she was hardly the type to spend the next two years shaking ill-manicured hands at municipal receptions. All this was assuming he won, of course. If he lost…

But the party bosses were expecting an answer. Roosevelt agreed, “with the most genuine reluctance,” to allow his name to be put before the convention.11 The emissaries departed, leaving him alone. Night came on. He remained ensconced in his club, waiting for the inevitable news from the Opera House.

![]()

HE HAD A LOT to think about during those solitary hours. Why had Johnny O’Brien, Jake Hess, Barney Biglin, and all the rest of the machine men offered him this unexpected honor? He was, after all, their ancient enemy. Perhaps they wished to reward him for his support of James G. Blaine in 1884; more likely they hoped he would lure the Independents back into the Republican fold, in order to have a united party behind Blaine—again—in 1888. Or perhaps they imagined (as many did) that he was a millionaire, and mightcontribute a liberal assessment to the campaign chest.12 They would soon learn the likelihood of that: half his capital was tied up in Dakota, and the interest on the remainder would barely support him and Edith at Sagamore Hill.13

A cynical hypothesis which he did not want to consider, but which would come up in the press, was that the party bosses had decided no Republican could win a three-way contest for the mayoralty, and merely wanted a few thousand votes to trade on Election Day.14 Certainly the campaign odds were against him. The Democrats had just nominated Representative Abram S. Hewitt, a man of mature years, vast wealth, moderate opinions, and impeccable breeding.15 Hewitt also happened to be an industrialist, famous for his enlightened attitude to labor (during the depression years 1873–78 he ran his steel works at a loss in order to safeguard the jobs of his employees).16 He would doubtless attract all but the most extreme George followers, along with those Republicans who felt nervous about Roosevelt’s youth. Only yesterday, the Nation had editorialized: “Mr. Hewitt is just the kind of man New York should always have for Mayor,” and Roosevelt’s instinct told him the voters would agree on 2 November.17

All in all, he concluded, it was “a perfectly hopeless contest, the chance of success being so very small that it may be left out of account … I have over forty thousand majority against me.” However, there was that chance; he had taken on older men before, and beaten them: his pugnacious soul rejoiced at the overwhelming challenge. He would make “a rattling good canvass” for the mayoralty, and would not be disgraced if he ran second. The only disaster would be to run third. But that seemed unlikely: in his opinion Henry George was “mainly wind.”18

![]()

SEVEN BLOCKS AWAY, in the bakingly hot, tobacco-blue auditorium of the Grand Opera House, Chauncey Depew, the Republican party’s most unctuous orator, was persuading delegates that the idea of a young mayor for this, “the third city of the world,” was a brilliant one. “Every Republican here tonight asks for young blood. I would select a young man whose family has long been identified with good government… [cheers and shouts for Roosevelt] … He came out of the Legislature with a reputation as wide as the confines of this nation itself.” A senior Republican leaped up to protest that the young man was a Free Trader.19 “If in his experience he has made a mistake,” grinned Depew, “he has had the courage to acknowledge it.” The protester was booed and hissed out of the hall, and the convention unanimously nominated Theodore Roosevelt for Mayor.20

![]()

RIGHT FROM THE START the candidate made it clear that he was going to run his own campaign. Establishing himself in luxurious headquarters at the Fifth Avenue Hotel, he informed the party bosses that he would pay “no assessment whatsoever” and would be “an adjunct to nobody.”21 These declarations aroused flattering comments in the press. “Mr. Roosevelt is a wonderful young man,” remarked the Democratic Sun. Even E. L. Godkin of the Post admitted: “If Roosevelt is elected, we have not a word to say against him.”22

Roosevelt remained sure that he could not win at least through the first four days of the campaign. He explained to Lodge that he was only running “on the score of absolute duty,” and hoped to enjoy, if nothing else, “a better party standing” afterward. “The George vote will be very large … undoubtedly thousands of my should-be supporters will leave me and vote for Hewitt to beat him.”23 But this did not prevent him from campaigning with all his strength. He worked eighteen-hour days, addressing three to five meetings a night, pumping hands, signing circulars, repudiating bribes, plotting strategy, and on at least one occasion dictating letters and holding a press conference simultaneously.24

As usual Roosevelt never minced words. He was determined to meet every issue head-on, even the touchy one of Labor v. Capital. George was so articulate on the left, and Hewitt so persuasive in the center, that Roosevelt might have been well advised to keep his own right-wing views tacit, and concentrate on other subjects; but that was not his style. When a Labor party official accused him of belonging to “the employing and landlord class, whose interests are best served when wages are low and rents are high,”25Roosevelt shot back with a contemptuous public letter, dated 22 October 1886.

“The mass of the American people,” he wrote, “are most emphatically not in the deplorable condition of which you speak.” As for the accusation that he, Roosevelt, belonged to the landlord class, “if you had any conception of the true American spirit you would know that we do not have ‘classes’ at all on this side of the water.” In any case, “I own no land at all except that on which I myself live. Your statement that I wish rents to be high and wages low is a deliberate untruth … I have worked with both hands and with head, probably quite as hard as any member of your body. The only place where I employ many wage-workers is on my ranch in the West, and there almost every one of the men has some interest in the profits.”

Roosevelt conceded that “some of the evils of which you complain are real and can be to a certain degree remedied, but not by the remedies you propose.” But most would disappear if there were more of “that capacity for steady, individual self-help which is the glory of every true American.” Legislation could no more do away with them “than you could do away with the bruises which you receive when you tumble down, by passing an act to repeal the laws of gravitation.”26

To this the Labor man could only reply, “If you were compelled to live on $1 a day, Mr. Roosevelt, would you not also complain of being in a deplorable condition?”27 But by then Roosevelt’s campaign was going so well—to everybody’s surprise—that the mournful question was ignored.

![]()

ON THE NIGHT of Wednesday, 27 October, Roosevelt’s twenty-eighth birthday, bonfires belched in the street outside Cooper Union, reddening the huge building’s facade until it glowed like a beacon. For almost an hour, rockets soared into the murky sky, casting showers of light over Lower Manhattan and attracting thousands of curious sightseers. By 7:30 P.M. every seat in the hall was filled, and standing room was at a premium as Republican citizens of New York gathered to ratify the nomination of Theodore Roosevelt forMayor. One old politician marveled that he had never seen such a crowd since Lincoln spoke at the Union in 1860.28

The guest of honor did not appear until shortly before eight o’clock. He had long ago learned the dramatic effect of delayed entry. In the meantime the audience could feast their eyes on his large crayon portrait, surrounded by American flags and a gilt eagle, and hung around with rich silk banners. It was, as one reporter observed, “a millionaires’ meeting.” Astors, Choates, Whitneys, Peabodys, and Rockefellers fondled each other’s lapels, and discussed “the boy Roosevelt’s” remarkable progress in the campaign so far.29They had been impressed to read, in various daily papers, such headlines as the following:

|

(22 Oct.) |

PIPING HOT—Roosevelt Busy as a Beaver |

|

(23 Oct.) |

RED HOT POLITICS—The Fight Going on Merrily All Over the City |

|

(24 Oct.) |

THE ROOSEVELT TIDAL WAVE—Growing Strength of the Candidate |

|

(25 Oct.) |

ROOSEVELT STILL LEADING |

|

(26 Oct.) |

CHEERS FOR ROOSEVELT, THE BOY |

|

(27 Oct.) |

ALL SOLID FOR ROOSEVELT30 |

Not only Republicans were impressed by him. Abram Hewitt himself admitted he would have liked Roosevelt on his team, as president of the Board of Aldermen.31 The editors of the Sun—Democrats to a man—had been moved to print these prophetic words on the eve of the Cooper Union meeting:

THEODORE ROOSEVELT has gone into the fight for the Mayoralty with his accustomed heartiness. Fighting is fun for him, win or lose, and perhaps this characteristic of his makes him as many friends as anything else. He makes a lot of enemies too, but so does anybody who is fit to live … He is getting to be somewhat a shrewder politician … and though he is somewhat handicapped by the officious support of the Union League Club, he may do well. It cannot be denied that his candidacy is attractive in many respects, and he is liable to get votes from many sources. He has a good deal at stake, and it’s no wonder that he is working with all the strength of his blizzard-seasoned constitution. It is not merely the chance of being elected Mayor that interests him. There are other offices he might prefer. To be in his youth the candidate for the first office in the first city of the U.S., and to poll a good vote for that office, is something more than empty honor.… He cannot be Mayor this year, but who knows what may happen in some other year? Congressman, Governor, Senator, President?32

![]()

“BLUSHING LIKE a schoolgirl,” Roosevelt bounces onstage to brass fanfares and a standing ovation.33 Somebody shouts, “Three cheers for the next Mayor of New York!” and the auditorium vibrates with noise. It is some minutes before Elihu Root, chairman of the Republican County Committee and the only calm man in the room (with his slit eyes, bangs, and waxlike cheeks, he resembles a Chinese mandarin), introduces Thomas C. Acton as chairman of the meeting. The silver-haired banker steps forward.

“You are called here tonight to ratify the nomination of the youngest man who ever ran as candidate for the Mayor of New York,” says Acton. “I knew his father, and wish to tell you that his father did a great deal for the Republican party, and the son will do more … [Applause] He is young, he is vigorous, he is a natural reformer. He is full, not of the law, but of the spirit of the law …” The chairman begins to flounder, then hits upon a crowd-pleasing phrase. “The Cowboy of Dakota!” he cries. “Make the Cowboy of Dakota the next Mayor!”

This brings about a roar so prolonged that the band has to strike up “Marching Through Georgia” to quell it. Roosevelt, showing all of his teeth, approaches the lectern.

His speech is typically short, blunt, and witty. He begins by noting that Abram Hewitt has predicted “every honest and respectable voter” will support the Democrats. “I think,” says Roosevelt, “that on Election Day Mr. Hewitt will find that the criminal classes have polled a very big vote.” When the laughter from that dies down, he goes on to counter the outgoing Mayor’s charge that he is “too radical” a reformer. “The time for radical reform has arrived,” he shouts, “and if I am elected you will have it.”

A VOICE You will be elected.

ROOSEVELT I think so, myself! (Great applause.)

He castigates his habitual targets, “the dull, the feeble, and the timid good,” and proclaims himself a strong man, careless of class, color, or party politics. “If I find a public servant who is dishonest, I will chop his head off if he is the highest Republican in this municipality!”34

An effective follow-up speech is made by Richard Watson Gilder, editor of Century magazine. He confesses that he has never stood on a political platform before, but is doing so now in order to praise “the best municipal nomination that has been made in my time … Mr. Roosevelt is, in my opinion, the pluckiest, the bravest man inside of politics in the whole country.”35 Amid thunderous applause, the nomination is declared ratified.

The candidate shakes hands for twenty minutes until aides drag him from the platform. Outside, in the rain, a large crowd is waiting to serenade him. “I hope to see you all down in the City Hall after January 1, when I am Mayor,” says Roosevelt. He bows and he smiles.36

![]()

AN EXTRAORDINARY HUSH descended on the city’s political headquarters next day, 28 October. Everybody except Roosevelt, it seemed, was aboard sight-seeing boats in the Bay, or fighting for a foothold on Bedloe’s Island, where, that afternoon, President Cleveland was due to unveil the great Statue of Liberty.37 Roosevelt, therefore, had a few hours alone at his desk, undisturbed except by a distant thumping of drums, to ponder press reports of his birthday rally, and review his chances for the mayoralty.

While the reports were generally flattering, there was no change in the partisan attitudes of any newspaper. The Times, Tribune, Commercial Advertiser, and Mail & Express were for him; the Herald, Sun, World, and Daily News were for Hewitt. Only a few smudgy ethnic sheets were for George. The balance, in other words, was fairly even: while Hewitt’s newspapers had more readers, Roosevelt’s reached more influential people. With his popular momentum increasing, and only five days left to go, it was tempting to believe the Times’s headline: “ROOSEVELT SURE TO WIN—THAT’S WHAT LAST NIGHT’S MEETING INDICATES.” The Tribune carried even more encouraging news, under the headline, “MR. ROOSEVELT’S PROSPECTS—HIS ELECTION NOW DEEMED CERTAIN.” It reported that the U.S. Chief Supervisor of Elections, after making an independent survey, projected a total vote of 85,850 for Roosevelt, 75,000 for Hewitt, and 60,000 for George.38

Even as he rejoiced in these figures, Roosevelt must have felt a threat in George’s amazing total. For a political virgin with no charisma and eccentric, not to say revolutionary views, George had proved to be a redoubtable campaigner. His platform, representing the aspirations of “the disinherited class,” was high-toned and reassuringly democratic. Businessmen as well as laborers nodded their heads over such sentences as “The true purpose of government is, among other things, to give everyone security that he shall enjoy the fruits of his labor, to prevent the strong from oppressing the weak, and the unscrupulous from robbing the honest … The ballot is the only method by which in our Republic the redress of political and social grievances can be sought.”39 There was no doubt as to George’s sincere identity with the working class, nor to his personal honor (he had refused Tammany’s offer of a seat in Congress if he would withdraw). One had to admire the dignity with which the little man climbed again and again onto his favorite pedestal, a horse-cart unshackled in the middle of some grimy street. “What we are beginning here,” George would yell, at the sea of cloth caps around him, “is the great American struggle for the ending of industrial slavery.” Sometimes he would go too far, as when he proclaimed that the French Revolution, “with all its drawbacks and horrors,” was “the noblest epoch in Biographies & Memoirs,” and was “about to repeat itself here.”40 Such inflammatory statements delighted his unlettered listeners, not to mention the nation’s anarchists, who looked forward to civil war if George was elected.

Roosevelt had confidence enough in the American democratic system to disbelieve that such a man would ever triumph at the polls. The real danger, as he saw it, was that Henry George’s hell-raising image (so like his own, unfortunately) might, come Election Day, turn responsible voters away from both of them, in favor of the solid and sober Abram S. Hewitt. Already Democratic papers were chanting the ominous refrain, “A vote for Roosevelt is a vote for George.”41

However it was not in his nature to think negatively. Hope lay in positive action. From now on he must campaign at an increasing rate, to offset any possible attrition in his lead. By late afternoon, when Republican Committee members began to arrive back from Bedloe’s Island, he was already hard at work on his evening’s speeches, and autographing colored lithographs of himself.42

![]()

“IT IS SUCH HAPPINESS to see him at his very best once more,” Bamie wrote to Edith in London. “This is the first time since the [1884] Investigation days that he has had enough work to keep him exerting all his powers. Theodore is the only person who has the power (except Father who possessed it in a different way) of making me almost worship him … I would never say, or, write this except to you, but it is very restful to feel how you care for him and how happy he is in his devotion to you …”43

![]()

A FAIR IMPRESSION of the pace of Roosevelt’s candidacy for Mayor may be gained by following him through one night of his campaign—Friday, 29 October.44

At 8:00 P.M., having snatched a hasty dinner near headquarters, he takes a hansom to the Grand Opera House, on Twenty-third Street and Eighth Avenue, for the first of five scheduled addresses in various parts of the city. His audience is worshipful, shabby, and exclusively black. (One of the more interesting features of the campaign has been Roosevelt’s evident appeal to, and fondness for, the black voter.) He begins by admitting that his campaign planners had not allowed for “this magnificent meeting” of colored citizens. “For the first time, therefore, since the opening of the campaign I have begun to take matters a little in my own hands!” Laughter and applause. “I like to speak to an audience of colored people,” Roosevelt says simply, “for that is only another way of saying that I am speaking to an audience of Republicans.” More applause. He reminds his listeners that he has “always stood up for the colored race,” and tells them about the time he put a black man in the chair of the Chicago Convention. Apologizing for his tight schedule, he winds up rapidly, and dashes out of the hall to a standing ovation.45 A carriage is waiting outside; the driver plies his whip; by 8:30 Roosevelt is at Concordia Hall, on Twenty-eighth Street and Avenue A. Here he shouts at a thousand well-scrubbed immigrants, “Do you want a radical reformer?” “YES WE DO!” comes the reply.46

At 9:00 P.M. he is in a ward hall at 438 Third Avenue, where the local boss introduces him as “the Cowboy Candidate.” He has had time to get used to this phrase—not that he dislikes it—and jokes that “as the cowboy vote is rather light in this city I will have to appeal to the Republicans.” But the audience is more interested in his experiences as deputy sheriff than his views on municipal reform, and Roosevelt makes his escape. He promises to return, as Mayor, with many stories about cowboys, bears, “and other associates in the West.”47

Now he rattles uptown to Grand Central Station, where a special locomotive (courtesy of New York & Harlem Railroad President Chauncey Depew) is waiting, with steam up, to speed him to Morrisania, in the Bronx. Roosevelt climbs into the observation cab over the boiler; the engine leaps north at sixty miles an hour. For thirteen minutes, red and green lights flash by: all railroad traffic has been halted in his favor. He arrives at Tremont Station only one minute late, and runs into the neighboring hall. Ladies of the 24th Ward present him with an immense floral horseshoe. He says that it is appropriate for a youthful candidate to come to this “young” district of the city. “Three times three cheers for the Boy!” yells someone. Not forgetting his bouquet, Roosevelt jumps back on the train and hurries south across the Harlem River. He reaches the 22nd Assembly District Roosevelt Club in time for his final address of the evening at 10:30 P.M. Then, at last, he can walk home to Bamie’s house, where Baby Lee lies sleeping.48

Somebody asked him the following morning, Saturday, if he was not exhausted by the pace he was setting himself. “Not in the least!” Roosevelt replied.49 His wellsprings of energy continued to bubble through the last night of the campaign, but close observers noticed a gradual decline in his confidence of victory. “The ‘timid good,’ ” he exasperatedly wrote Lodge, “are for Hewitt.” The word “if” crept frequently into his speeches: “If I am not knifed in the house of my friends I shall win.”50

![]()

KNIVES FLEW thick and fast in those final days, and he could not be sure whether some of the throwers might be his fellow Republicans. A sudden rumor went around that James G. Blaine was coming to lend a hand in the campaign, just when Roosevelt thought he had at last explained away his support of the Plumed Knight in 1884. He was obliged to issue an angry statement that Blaine “had not and would not be invited to speak here.”51 At a large downtown rally for Hewitt, ex–State Senator David L. Foster made a devastating analysis of ex-Assemblyman Roosevelt’s democratization of the Board of Aldermen: “The result of this change in the first year of its adoption was that two of them died, five left the country, and about seventeen of them were indicted for crime.”52Uptown, meanwhile, moonlighting newsboys delivered Democratic newspapers to Republican subscribers, and the slogan “A Vote for Roosevelt is a Vote for George” penetrated into the heart of his traditional constituency.53

These same newspapers shrewdly caricatured the “boy” image, knowing that thousands of voters felt nervous about putting a twenty-eight-year-old in charge of America’s largest city. “It has been objected that I am a boy,” said Roosevelt wearily—he had been hearing the charge for years—“but I can only offer the time-honored reply, that years will cure me of that.” He must have been humiliated by a full, front-page cartoon in the Daily Graphic, entitled “The Two Candidates,” showing Henry George and Abram Hewitt squaring off at each other like giants: only after close inspection did readers perceive the tiny, bespectacled head of Roosevelt peeping out of George’s tote-bag.54

Most damaging, perhaps, was the Star’s publication (on Sunday, 31 October, when the whole city was at home with the papers) of a remark President Cleveland had made as Governor, after vetoing Roosevelt’s Tenure of Office Bill: “Of all the defective and shabby legislation which has been presented to me, this is the worst and the most inexcusable.”55 The World reprinted this statement on Monday morning, aggravating Roosevelt’s embarrassment as his campaign entered its penultimate twenty-four hours.

Evidently sensing defeat now, Roosevelt dropped his hitherto courteous attitude to the opposition. Henry George was “a galled jade,” E. L. Godkin was “that peevish fossil,” Hewitt’s backers were “the same old gang of thieves who have robbed the city for years.”56 Those telltale signs of Rooseveltian frustration, the angry f’s and popping p’s, reappeared in his oratory: “They [the Democrats] are men who fatten on public plunder—I shall make no promises before election that I will not keep when in office: I propose to turn the plunderers out.”57

But for the most part he managed to preserve his dignity, as did Hewitt and George in their own contrasting ways. Observers were agreed on Monday night that it had been a splendid contest, fought by men of exceptional quality, inspiring the public to a degree hitherto only seen in presidential years. Substantive issues had been raised and discussed—municipal reform by Roosevelt, social injustice by George, and the dangers of unionized politics by Hewitt. The two latter candidates had, moreover, exchanged a stately series of open letters which expounded the philosophies of Labor v. Capital so brilliantly that Roosevelt himself suggested they should be published in book form. The fact that he could make such a generous proposal, at a time when his own strength was in doubt, is testimony to the elevated mood of all three men. To this day the mayoral campaign of 1886 is regarded as one of the finest in the history of New York.58

![]()

THE LAST FORECASTS varied widely, with newspapers as usual differing along partisan lines. The Journal came nearest to an accurate reflection of the city’s enigmatic atmosphere: “Seldom has an election for Mayor of New York presented greater uncertainties on the eve of the voting than the one that will be decided tomorrow. The leaders … are at sea.”59

Through most of the campaign the weather had been cold and drizzly, with curtains of fog drifting around Manhattan, seeming to seal the island off from the outside world. It was still murky when Roosevelt (looking fatigued at last) went to bed on Monday night, but early next morning a meteorological “break” took place. Shortly after dawn, the Statue of Liberty revealed herself above the low fog lying across the Bay. She glowed brilliantly as the sun struck her, and for a while seemed to be standing on a pedestal of cloud.60 Then a mild breeze whisked the fog away, and New York awoke to Indian summer. The streets, washed clean by weeks of rain, steamed dry in the warmth, and the people turned out en masse to vote.61

Peace and good humor prevailed around the ballot boxes. Since the taverns were shut, and the sunshine luxurious, thousands spent the entire day out-of-doors. Rumors as to how the voting was going flashed with near-telegraphic speed from one street corner to another.62

As early as 2:00 P.M., secret messages came to Republican headquarters that George’s vote was going to be very high and Roosevelt’s very low. While the candidate sat innocently by, the party bosses shot back their secret reply: Republicans must vote for Hewitt. At all costs George must be stopped.63

The secret, of course, could not long be kept from Roosevelt. His emotions on discovering that he was being “sold out”—even for honorable political reasons—can be imagined. But he maintained a good-humored front, and tried to cheer his drooping staff by telling funny stories. About six o’clock he went out into the bonfire-lit night for dinner with friends. He seemed as buoyant as ever when he returned two hours later. By then it was plain that his defeat had become a rout.64 The only good news to come his way that evening was a telegram from Boston, announcing that Henry Cabot Lodge had been elected to the Congress of the United States. He shouted with joy, and sent his congratulations by return wire:

AM MORE DELIGHTED THAN I CAN SAY. DO COME ON THURSDAY.

AM BADLY DEFEATED. WORSE EVEN THAN I FEARED.

THEODORE ROOSEVELT.65

![]()

AFTER A LATE BREAKFAST next morning, Roosevelt went back to his headquarters and found it taken over by “a small army of scrub women.” But he seemed reluctant to leave, and sat around until a lone newspaperman poked his head in through the door. “I thought I’d look in to see what they had done with the corpse.” Roosevelt responded with a most uncorpselike grin.66

By rights the final returns, as headlined that day, should have made him wince. Hewitt had scored 90,552; George, 68,110; Roosevelt, 60,435.67 These figures were unassailable: the polls had been rigorously supervised. The turnout had been prodigious—20,000 more ballots were cast than during last year’s gubernatorial election—yet Roosevelt’s votes were 20 percent fewer than the Republican total on that occasion. To compound his humiliation, he found that he had run far behind every state and city candidate on the Republican ticket, including those for minor posts on the Judiciary and Board of Aldermen. The Post sadistically pointed out that “Mr. Roosevelt’s vote is lower than any other Republican vote in the last six years.”68

The main reason for his poor showing was, of course, the Republican defection to Hewitt, which he estimated at 15,000, and the Democrats at 10,000. What must have rankled was the fact that this defection took place not in the sleazy wards of the East and West Sides (where he proved surprisingly popular) but in the wealthier “brownstone district” he had always regarded as his natural constituency. “I have been fairly defeated,” he told a Tribune reporter later in the day, as he watched portraits of himself being ripped off the wall and thrown away. “But to tell the truth I am not disappointed at the result.”69

The evidence is that he was—deeply so.70 This third political defeat in just over two years became one of those memories which he ever afterward found too painful to dwell on. It rates just one sentence in his Autobiography. He talked often in later years of his various campaigns, but that of 1886 was rarely, if ever, mentioned. Once, when he was telling one of his “gory stories,” about killing a bear, somebody sympathized out loud for the unfortunate animal: “He must have been as badly used up as if he had just run for Mayor of New York.” Roosevelt overreacted. “What do you mean?” he roared, slamming his fists down on the table. It was some time before he could recover himself.71

![]()

ON THE WHOLE, the press of the day treated him kindly. Republican papers noted that if there had not been a panic swing to Hewitt, Roosevelt would have won. The opposition expressed admiration for his courage against impossible odds. Few editorials displayed any contempt. Even the Daily Graphic, which had often poked cruel fun at him, quoted the consolatory lines,

Men may rise on stepping stones

Of their dead selves to higher things …

and added: “Reflect on this Tennysonian thought, Mr. Roosevelt, and may your slumbers be disturbed only by dreams of a nomination for the Governorship, or perhaps the Presidency in the impending by and by.”72

A “Mr. and Miss Merrifield” sneaked up the gangplank of the Cunard liner Etruria early on Saturday morning, 6 November. No social reporters were prowling the decks at that hour, or it might have been noticed that the couple bore a marked resemblance to Theodore and Bamie Roosevelt. They had sat up all night writing announcement notes of the engagement and forthcoming wedding; by the time those notes reached their destinations, the Etruria would be heading out to sea.73

Nobody bothered them that day, and the great ship sailed on schedule at 1:00 P.M.74 It was not until next morning that a fellow passenger penetrated their disguise. He was a pale young Englishman who approached them with a combination of courtliness andinquisitiveness which they ever afterward associated with the White Rabbit in Alice. Might “Miss Merrifield” by any chance be Miss Roosevelt? Bamie, “being well out of sight of land,” admitted she was. The young man promptly introduced himself, in the accents of Eton, Oxford, and the Foreign Office, as Cecil Arthur Spring Rice, former assistant private secretary to Lord Rosebery. He said that he was on his way home to England, after spending some “leave” with a brother in Canada.75

Spring Rice, generally known as “Springy” or “Sprice,” was a born diplomat, and would soon become a professional one. He had a particular way with women. His sharp eye and social instinct had been honed in the best drawing rooms; he invariably picked out and cultivated the most important person in any place, whether it be a Tuscan hill-town or the heaving deck of a transatlantic steamer. Roosevelt, who (despite his ludicrous attempt to look anonymous) emitted an unmistakable glow of power and good breeding, was just such a person. Somehow Spring Rice had found out, through mutual friends in New York, that he would be on board, and had obtained letters of introduction to Bamie.76

The Englishman’s charm was, in any case, such that he could make friends without any conventional formalities. Roosevelt fell victim to it, while beaming his own charm in return—apparently with even greater effect. Spring Rice was to be, for the rest of his life, one of Roosevelt’s most ardent—if amused—admirers. Not only was this American cultured, talkative, and well-connected, he had a certain raw physical force, and a sense of personal direction (for all his recent rejection at the polls) that transcended Spring Rice’s own petty ambitions at the Foreign Office. Although Roosevelt was only four months older, he seemed to have lived at least a decade longer. Here was a man worth introducing to his friends at the Savile Club.

By the time the Etruria arrived in Liverpool on 13 November, “Springy” had agreed to act as Roosevelt’s best man.77

![]()

LOOKING BACK on the eighteen days he spent in London and the Home Counties before his wedding on 2 December, Roosevelt said he felt “as if I were living in one of Thackeray’s novels.”78 Romantically foggy weather added a dreamlike quality to his adventures.79 Spring Rice’s connections afforded him easy entry into British society: he was “treated like a prince … put down at the Athenaeum and the other swell clubs … had countless invitations to go down in the country and hunt or shoot.” For every invitation he accepted there were at least three he turned down—some, such as lunch with the Duke of Westminster or weekends with Lords North and Caernarvon, with real regret. “But I was anxious to meet some of the intellectual men, such as Goschen, John Morley, Bryce, Shaw-Lefèvre … I have dined or lunched with them all.”80 So busy was he that he found no time to pay his respects to the American Ambassador, and that gentleman let his displeasure be known.81

But Roosevelt had his priorities. No doubt he took frequent strolls through Mayfair to the Bucklands Hotel on Brook Street, where Edith was staying with her mother and sister. No doubt she returned these calls, and sat with him in his rooms in Brown’s Hotel on Dover Street; here they discovered “how cosy and comfortable one could be, with a small economical handful of coal in the grate and heavy fog outside.”82

“You have no idea how sweet Edith is,” Roosevelt wrote Corinne in a defensive tone wholly new to him. “I don’t think even I had known how wonderfully good and unselfish she was; she is naturally reserved and finds it especially hard to express her feelings on paper.”83 He had never had to explain his first wife to anybody, but then Alice Lee had needed no explanation. The complicated, mysterious person who was now preparing to marry him had depths and secrets and silences, like this very fog enshrouding London; it would be years before she disclosed herself fully to him, and even then he might not altogether understand her.

Visibility was so bad on the morning of 2 December that link-bearers had to be hired to guide Roosevelt’s carriage to St. George’s, Hanover Square. Bamie, arriving separately, found the church itself full of fog. She could not see her brother at the far end of the nave, much less the altar. When she moved into close range she noticed that Spring Rice had, for inscrutable reasons, persuaded him to wear bright orange gloves.84

The church was almost empty. Even if hundreds had been in the congregation, the fog would have muffled their whispering. This wedding, unlike Theodore’s first, was to be quiet—“as the wedding of a defeated mayoralty candidate should be.”85

He stood there alone with his orange gloves, waiting for Edith to walk out of the mists behind him.