“Death be to the evil-doer!”

With an oath King Olaf spoke;

“But rewards to his pursuer!”

And with wrath his face grew redder

Than his scarlet cloak.

![]()

UNABLE TO TEAR HIMSELF away from Edith, Roosevelt remained in the East for a “purely society winter,” as he called it, of dinners, balls, and the Opera. At the height of the season, through January and February 1886, he was going out every other night.1 Fanny Smith Dana saw him often with Edith, yet suspected nothing: to an old family friend they looked as natural together as brother and sister.2

What the couple were at pains to conceal in public, they also concealed in private. Page after page of Roosevelt’s diary for the period contains nothing but the cryptic initial “E.”3 One can only sigh for the rhapsodies of self-revelation that Alice Lee evoked. But Roosevelt had been a boy then, as much in love with love as with a girl. Now he was a man in love with a woman, and his passion was correspondingly deeper, more dignified. Edith was not the sort of person to encourage rhapsodies, anyway. She disapproved of excess, whether it be in language, behavior, clothes, food, or drink. Too much ardor was just as vulgar as too much cream on too many peaches—another Rooseveltian tendency she was determined to restrain. In her opinion, any revelation of the intimacies between lovers, even in a man’s diary, was abhorrent. The thought of such details ever becoming public obsessed her, to the point that “burn this letter” became a catch-phrase in her own correspondence. Her influence over Theodore was already sufficient to control his pen in the winter of 1885–86; yet it must be remembered that he, too, had become something of a self-censor. The mature Roosevelt wrote nothing that he could not entrust to posterity. Many of his purportedly “family” letters were quite obviously written for publication. On such occasions he signed himself formally THEODORE ROOSEVELT instead of his usual “Thee.”4 Only in his letters to Edith did he spill out his soul, in the secure knowledge that she would read, understand, and then destroy. By some freak chance one of these love letters has survived. Although written in old age, it is as passionate as anything he ever composed during his courtship of Alice Lee.

“We took them absolutely by surprise.”

Deputy Sheriff Roosevelt and his prisoners:

Burnsted, Pfaffenbach, and Finnegan. (Illustration 13.1)

They continued to suppress details of their engagement, and in later years Edith even went through family correspondence to weed out every single reference to it.5 Why she should be quite so secretive is unclear, for it flowered out into a famously successful marriage. Possibly there were quarrels, even estrangements; both she and Theodore were powerful personalities, used to getting their own way. Whatever the case, history must respect their fierce desire for privacy.

As the season proceeded, Roosevelt saw more and more of Edith. He grew bored and restless when forced to socialize without her. “I will be delighted when I get settled down to work of some sort again,” he told Henry Cabot Lodge. “… To be a man of the world is not my strong point.”6 Lodge was now president of the Boston Advertiser, had contracted to write a life of George Washington for the prestigious American Statesmen series, and was determined to run again for Congress later in the year. On a trip to New York at the end of January, he projected such an air of purposeful industry that Roosevelt felt ashamed of his own dallying. “I trust that you won’t forget your happy-go-lucky friend,” he wrote, after Lodge’s return to Boston. “Anything connected with your visit makes me rather pensive.”7

Lodge, meanwhile, had sympathetically pulled a few strings, with the result that Roosevelt also received a commission to write an American Statesmen book.8 His biography was to be of Senator Thomas Hart Benton, the Western expansionist. It was an ideal subject for a young author of proven historical ability and intimate knowledge of life on the frontier. He accepted with delight, and plunged at once into his preliminary research.

![]()

AS FEBRUARY MERGED into March, Roosevelt began to feel neglectful of his “backwoods babies” on the Elkhorn Ranch. They had not seen him for nearly six months, and their morale was surely low: he knew how depressing winter in the Badlands could be. If he did not go West soon, the pessimistic Bill Sewall might work himself into such a state of gloom as to ask for release from his contract. Will Dow would certainly follow suit. With Elkhorn now fully capitalized and turning over satisfactorily, Roosevelt could ill afford to lose either man.

Edith, moreover, would not long detain him in the East. She had confirmed her decision to accompany her mother and sister to Europe in early spring, perhaps because she could not afford to remain behind, or more likely because she knew her absence would remove any lingering doubts Roosevelt might have about marrying her. (He was still racked with guilt about the memory of Alice Lee.) If, by next winter, he was ready to follow her across the Atlantic, a quiet wedding could be arranged in London.9

So, on 15 March, after spending ten final days almost entirely with “E,” Roosevelt left New York for Medora.10

![]()

ELKHORN RANCH

March 20th 1886

Darling Bysie [Bamie],

I got out here all right, and was met at the station by my men; I was really heartily glad to see the great, stalwart, bearded fellows again, and they were as honestly pleased to see me. Joe Ferris is married, and his wife made me most comfortable the night I spent in town. Next morning snow covered the ground; but we pushed [on] to this ranch, which we reached long after sunset, the full moon flooding the landscape with light. There has been an ice gorge right in front of the house, the swelling mass of broken fragments having been pushed almost up to our doorstep … No horse could by any chance get across; we men have a boat, and even then it is most laborious carrying it out to the water; we work like Arctic explorers.

Things are looking better than I expected; the loss by death has been wholly trifling. Unless we have a big accident I shall get through this all right; if not I can get started square with no debt.…

Your loving brother

THEE11

![]()

THE ABOVE-MENTIONED BOAT was, like Roosevelt’s rubber bathtub, an object of some curiosity in the Badlands. There were, to be sure, a few scows tied up at various points along the valley, but often as not their keels rotted away from disuse. For most of the year the Little Missouri was too shallow even for a raft: cowboys galloped across it wherever they chose, barely wetting their horses’ bellies. In winter the river froze rapidly, and men and wolves traveled up and down it as if it were a highway.12

Only in freak weather, such as that prevailing in March 1886, did the Elkhorn boat really come in useful. Sewall and Dow, who were experienced rivermen, kept it in beautiful trim. Small, light, and sturdy, it was available at a moment’s notice whenever they wanted to cross the river for meat, or to check up on their ponies.13

Arctic conditions continued for days after Roosevelt’s arrival. At night, as he lay in bed, he could hear the ice-gorge growling and grinding outside. Floes were still coming down so thickly that the jam increased rather than diminished. If the ranch house had not been protected by a row of cottonwoods, it would have been overwhelmed by ice.14 Fortunately a central current of speeding water kept the gorge moving. To prevent the boat from being dragged away, Sewall roped it firmly to a tree.

Early on the morning of 24 March, however, he went out onto the piazza and found the boat gone. It had been cut loose with a knife; nearby, at the edge of the water, somebody had dropped a red woolen mitten.15

Roosevelt reacted so angrily on hearing this news that he had to be dissuaded from saddling Manitou and thundering off in instant pursuit of the thieves.16 A horse, Sewall pointed out, was of little use when the river was walled off on both sides with ice. Roosevelt would never get within a mile of the men in his boat: all they had to do was keep floating downstream (the current was such they could not possibly have gone upstream) until he gave up, or galloped to his death across the gorge. There was only one thing to do: build a makeshift scow and follow them. The thieves probably felt secure in the knowledge that they had stolen the only serviceable boat on the Little Missouri, and would therefore be in no hurry. He had at least an even chance of catching them. Roosevelt agreed, and sent to Medora for a bag of nails.17

It was not the value of his loss that annoyed him: the Elkhorn boat was worth a mere thirty dollars. But he was, by virtue of his chairmanship of the Stockmen’s Association, a deputy sheriff of Billings County, and bound (at least by his own stern moral code) to pursue any lawbreakers. Besides, he had been intending to use the boat on a cougar hunt that very day, and his soul thirsted for revenge. He knew very well who the thieves were: “three hard characters who lived in a shack, or hut, some twenty miles above us, and whom we had shrewdly suspected for some time of wishing to get out of the country, as certain of the cattlemen had begun openly to threaten to lynch them.”18 Charges of horse-stealing had been leveled against their leader, “Redhead” Finnegan, a long-haired gunman of vicious reputation. (During the previous summer he had blasted half the buildings in Medora with his buffalo-gun, in consequence of a practical joke played on him while drunk.)19 Finnegan’s associates were a half-breed named Burnsted, and a half-wit named Pfaffenbach. All three men must be desperate, or they would never have made a break in such weather; if chased, they would certainly shoot for their lives.

While Sewall and Dow labored with hammers and chisels, Roosevelt, ever the schismatic, began to write Thomas Hart Benton. He completed Chapter 1 on 27 March, by which time the boat, a flat-bottomed scow, was ready.20 But a furious blizzard delayed their departure for three more days. Roosevelt soothed his impatience with a literary letter to Cabot Lodge. “I have got some good ideas in the first chapter, but I am not sure they are worked up rightly; my style is rough, and I do not like a certain lack of sequitur that I do not seem able to get rid of.” Casually mentioning that he was about to start downriver “after some horse thieves,” he added, “I shall take Matthew Arnold along.”21 He also took Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina, and a camera to record his capture of the thieves. Already he was thinking what a good illustrated article this would make for Century magazine.22

The story of the ensuing boat-chase was to become, with that of the Mingusville bully, one of Roosevelt’s favorite after-dinner yarns.

![]()

EARLY ON THE MORNING of 30 March the three pursuers pushed their scow into the icy water.23 Mrs. Sewall and Mrs. Dow, who were both five months pregnant, worriedly watched them go. The fact that Redhead Finnegan already had six days’ start was no reassurance that they would see their menfolk again, for the north country was known to be bleak, and full of hostile Indians.

The boat picked up speed as the river current took it. With Sewall steering, and Dow keeping watch at the bow, there was nothing much for Roosevelt to do. He snuggled down amidships with his books and buffalo robes, determined to have “as good a time as possible.”24 From time to time he would look up from Matthew Arnold and watch the high, barren buttes slide by. They were rimed with snow, yet blotched here and there with rainbow outbursts of yellow, purple, and red. Closer, and on either side, the ice-walls loomed in crazy, glittering stacks. “Every now and then overhanging pieces would break off and slide into the stream with a loud, sullen splash, like the plunge of some great water-beast.” These sights and sounds were duly memorized for his article.25 Seeking a simile to describe the shape of the buttes as dusk came on and reduced them to silhouettes, he thought of “the crouching figures of great goblin beasts,” then decided that Browning had said it better:

The hills, like giants at a hunting, lay

Chin upon hand, to see the game at bay …26

Progress was fairly rapid that day and the next, Sewall and Dow poling through stretches of bad water with an expertise no Westerner could match. They would have moved faster had it not been for a freezing wind in their faces, which seemed to bluster ever stronger, no matter which way the river turned. (Sewall was heard grumbling that it was “the crookedest wind in Dakota.”)27 The temperature dropped steadily, and ice began to form on the handles of the poles. The only sign of human life was a deserted group of tepees, sighted on the second day. Of the thieves there was no trace whatsoever. It began to seem as if Finnegan had not headed downriver after all. Then why steal a boat?

They camped, when they were too cold to go on, under whatever shelter they could find ashore, but naked trees afforded little relief from the wind. During the second night, the thermometer reached zero.

Next morning, 1 April, anchor-ice was jostling so thick they could not push on for several hours. They managed to shoot a couple of deer for breakfast, and the hot meat warmed their frozen bodies back to life. Early that afternoon, when they were nearly a hundred miles north of Elkhorn, they rounded a bend, laughing and talking, and almost collided with their stolen boat.28 It lay moored against the right bank.

From among the bushes some little way back, the smoke of a campfire curled up through the frosty air … Our overcoats were off in a second, and after exchanging a few muttered words, the boat was hastily and silently shoved toward the bank. As soon as it touched the shore ice I leaped and ran up behind a clump of bushes, so as to cover the landing of the others, who had to make the boat fast. For a moment we felt a thrill of keen excitement and our veins tingled as we crept cautiously toward the fire …

We took them absolutely by surprise. The only one in the camp was the German [Pfaffenbach], whose weapons were on the ground, and who, of course, gave up at once, his companions being off hunting. We made him safe, delegating one of our number to look after him particularly and see that he made no noise, and then sat down and waited for the others. The camp was under the lee of a cut bank, behind which we crouched, and, after waiting an hour or over, the men we were after came in. We heard them a long way off and made ready, watching them for some minutes as they walked towards us, their rifles on their shoulders and the sunlight glittering on their steel barrels. When they were within twenty yards or so we straightened up from behind the bank, covering them with our cocked rifles, while I shouted to them to hold up their hands … The half-breed obeyed at once, his knees trembling as if they had been made of whalebone. Finnegan hesitated for a second, his eyes fairly wolfish; then, as I walked up within a few paces, covering the center of his chest so as to avoid overshooting, and repeating the command, he saw that he had no shot, and, with an oath, let his rifle drop and held his hands up beside his head.29

Having divested his prisoners of an alarming array of rifles, revolvers, and knives, Roosevelt now found himself in something of a quandary. He could not tie them up, for their hands and feet would freeze off.30 What was more, Mandan, the first big town downriver, was more than 150 miles away, and the ice-floes ahead were so thick it could be weeks before they got there. With six mouths to feed, and game apparently nonexistent upriver, he was fast running out of provisions.31 The surrounding countryside, as far as he could see, was uninhabited. There was no question of returning to Elkhorn: the river was nonnavigable in reverse. Any right-minded Westerner, of course, would have executed his prisoners on the spot, then abandoned the boats, and walked back to civilization. But Roosevelt’s ethics would not allow that. He was determined to see Finnegan in jail, according to due process of law. His only choice, therefore, was to pole on downriver behind the ice-jam, pray that it would quickly thaw, and maintain a constant guard over the thieves. If this meant losing half a night’s sleep every second night, he could stand it.

Now began eight days as monotonous and wearing as any he ever spent. The weather remained so cold that the ice-jam rarely shifted before noon, only to wedge again, like a floating mountain, a few miles farther on. Sometimes they had to fight against being sucked under by the current—all the while keeping an eye on Redhead, who was capable of quick and murderous movement. “There is very little amusement in combining the functions of a sheriff with those of an Arctic explorer,” Roosevelt decided.32

Game continued scarce. By 6 April the party had nothing to eat but dry flour. They were forced to make soggy, unleavened cakes by dunking fistfuls of it in the dirty water. But Roosevelt’s spirits remained high. The strange camaraderie that develops between captors and captives in isolation reached the point where all six men joked and talked freely, “so that an outsider overhearing the conversation would never have guessed what our relations to each other really were.” No reference was made to the boat-theft after the first night out.33

![]()

ROOSEVELT, HAVING FINISHED his volume of Matthew Arnold, proceeded to devour Anna Karenina, in between spells of guard duty. He saw nothing incongruous in this. “My surroundings were quite grey enough to harmonize with Tolstoy.”34 The book both attracted and repelled him. His subsequent review of it for Corinne reveals a strange combination of sophistication and naiveté in his critical intellect, plus the insistence that all art should reaffirm certain basic moral values:

I hardly know whether to call it a very bad book or not. There are two entirely different stories in it; the connection between Levin’s story and Anna’s is of the slightest, and need not have existed at all. Levin’s and Kitty’s history is not only very powerfully and naturally told, but is also perfectly healthy. Anna’s most certainly is not, though of great and sad interest; she is portrayed as being prey to the most violent passion, and subject to melancholia, and her reasoning power is so unbalanced that she could not possibly be described otherwise than as in a certain sense insane. Her character is curiously contradictory; bad as she was however she was not to me nearly as repulsive as her brother Stiva; Vronsky had some excellent points. I like poor Dolly—but she should have been less of a patient Griselda with her husband. You know how I abominate the Griselda type. Tolstoy is a great writer. Do you notice how he never comments on the actions of his personages? He relates what they thought or did without any remark whatever as to whether it was good or bad, as Thucydides wrote history—a fact which tends to give his work an unmoral rather than moral tone, together with the sadness so characteristic of Russian writers.35

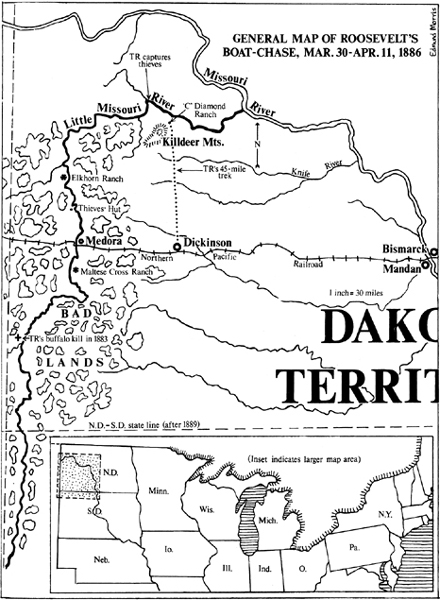

On 7 April Roosevelt struck civilization in the form of a cow camp, and stocked up on bacon, sugar, and coffee. The following day he rode a borrowed bronco fifteen miles to the C Diamond Ranch in the Killdeer Mountains, where he hired a prairie schooner and two horses. The rancher was puzzled as to why he had not strung up his prisoners long since, but agreed to drive them to the sheriff’s office in Dickinson, forty-five miles south. Sewall and Dow were to continue downriver to Mandan at their own speed.36

Roosevelt elected to walk behind the ranchman’s wagon, for he did not trust him. “I had to be doubly at my guard … with the inevitable Winchester.” They set off on 10 April, the twelfth day of the expedition. By now the long-delayed thaw had begun, and the prairie was a sea of clay:

I trudged steadily the whole time behind the wagon through the ankle-deep mud. It was a gloomy walk. Hour after hour went by always the same, while I plodded along through the dreary landscape—hunger, cold, and fatigue struggling with a sense of dogged, weary resolution. At night, when we put up at the squalid hut of a frontier granger, I did not dare to go to sleep, but … sat up with my back against the cabin door and kept watch over them all night long. So, after thirty-six hours’ sleeplessness, I was most heartily glad when we at last jolted into the long, straggling main street of Dickinson, and I was able to give my unwilling companions into the hands of the sheriff.

Under the laws of Dakota I received my fees as a deputy sheriff for making the arrests, and also mileage for the three hundred miles gone over—a total of some fifty dollars.37

![]()

DR. VICTOR H. STICKNEY of Dickinson was just going home to lunch when he met Roosevelt limping out of the sheriff’s office.

This stranger struck me as the queerest specimen of strangeness that had descended on Dickinson in the three years I had lived there … He was all teeth and eyes. His clothes were in rags from forcing his way through the rosebushes that covered the river bottoms. He was scratched, bruised, and hungry, but gritty and determined as a bulldog … I remember he gave me the impression of being heavy and rather large. As I approached him he stopped me with a gesture, asking me whether I could direct him to a doctor’s office. I was struck by the way he bit off his words and showed his teeth. I told him I was the only practicing physician, not only in Dickinson, but in the whole surrounding country.

“By George,” he said emphatically, “then you’re exactly the man I want to see … my feet are blistered so badly that I can hardly walk. I want you to fix me up.”

I took him to my office and while I was bathing and bandaging his feet, which were in pretty bad shape, he told me the story of his capture of the three thieves … We talked of many things that day … He impressed me and he puzzled me, and when I went home to lunch, an hour later, I told my wife that I had met the most peculiar and at the same time the most wonderful man I ever came to know.38

Relaxing next morning in his Dickinson hotel room, Roosevelt wrote to Corinne: “What day does Edith go abroad, and for how long does she intend staying? Could you not send her, when she goes, some flowers from me? I suppose fruit would be more useful, but I think flowers ‘more tenderer’ as Mr. Weller would say.”39

Of course he knew very well when Edith was leaving, and where she was going; but his sisters were not yet in on the secret, and appearances had to be kept up.40

![]()

HE RETURNED TO MEDORA on 12 April, just in time to witness Billings County’s first election as an organized community. Under the supervision of one “Hell-Roaring” Bill Jones, who stood over the ballot-box with a brace of pistols, the votes were cast with a minimum of bloodshed, and a county council duly returned to power. While its first edict, promising “to hang, burn, or drown any man that will ask for public improvements at the expense of the County,” could have been worded more diplomatically, it at least voiced sound Republican sentiments, and Roosevelt had every reason to be optimistic about the future of representative government in the Badlands.41

![]()

THE FOLLOWING DAY, 13 April, he chaired the spring meeting of his Stockmen’s Association. The Marquis de Morès was present, yet there was no doubt as to who was the dominant force in the room. Roosevelt conducted the proceedings with iron authority, instantly gaveling to order any speaker who strayed from the subject under discussion. Afterward the stockmen were loud in his praise.42

By 18 April, when he arrived in Miles City as a delegate to the much larger Montana Stock Grower’s Convention, word of his capture of Redhead Finnegan had spread across the West, and Roosevelt found that he had become a minor folk hero. During his three days there he was “constantly in the limelight,” and could report to Bamie, “these Westerners have now pretty well accepted me as one of themselves.”43 No longer was he “Four Eyes,” “that dude Rosenfelder,” and “Old Hasten Forward Quickly There” (an allusion to the unfortunate order he had yelled at some cowboys shortly after coming to Dakota). Sourdoughs everywhere allowed that he was “one of our own crowd,” “not a purty rider, but a hell of a good rider,” and (highest praise of all) “a fearless bugger.”44

Roosevelt accepted such compliments graciously, while being careful “to avoid the familiarity which would assuredly breed contempt.”45 Somehow he managed to preserve his gentlemanly status without offending democratic sensibilities—a trick the Marquis de Morès must have envied. Bill Merrifield and Sylvane Ferris thought nothing of moving their mattresses to the loft of the Maltese Cross cabin whenever he came to stay: it was understood that “the boss” liked to sleep alone downstairs.46 Sewall and Dow were allowed to sit in their shirt-sleeves at the Elkhorn table, but they were expected to address him always as “Mr. Roosevelt.” So, for that matter, were his fellow ranchers, some of whom were wealthy enough to consider themselves his social equal. “[Howard] Eaton called him ‘Roosevelt’ once,” Merrifield remembered, “and he turned round and said, ‘What did you say.’ You bet Eaton never did again.”47 Nobody, of course, dared call him “Teddy,” a word which since the death of Alice had become anathema to him. “That was absolutely wrong.”48

During the spring roundup, which was even more arduous than that of 1885 (five thousand cattle and five hundred horses were involved), Roosevelt put in his fair share of twenty-four-hour days, although he was distracted periodically by Benton.49 The conflict between mind and body which Thayer had forecast had already begun. But Roosevelt insisted that he was having “great fun” and felt “strong as a bear.” On 19 June he wrote Bamie: “I should say this free open air life, without any worry, was perfection. I write steadily three or four days, then hunt (I killed two elk and some antelope recently) or ride on the round-up for many more.” Although he was wistful for Sagamore Hill, and missed Baby Lee “dreadfully,” he decided to remain West all summer.50

![]()

BENTON, INCREDIBLY, was reported to be complete “all but about thirty pages” by the end of June.51 It will be remembered that Roosevelt had only just finished chapter 1 before setting off on his boat-chase on 30 March. A month’s hiatus followed: after returning from Dickinson he had been so busy with cattle-politics and hunting that he did not take up his pen again until 30 April. During the next three weeks he must have written the bulk of the 83,000-word volume, for on 21 May he left to join the roundup.52 From time to time after that, when there was a lull in activity on the range, he would ride into Medora and put in a day or two of literary labor in his room over Joe Ferris’s store. Ferris remembered the sound of his footsteps upstairs, as Roosevelt paced up and down, wrestling with obstinate sentences far into the night.53 “Writing is horribly hard work to me,” he complained.54 On 7 June, when the roundup was at its height, he sent a wry appeal to Henry Cabot Lodge:

I have pretty nearly finished Benton, mainly evolving him from my inner consciousness; but when he leaves the Senate in 1850 I have nothing whatever to go by; and, being by nature a timid and, on occasions, by choice a truthful man, I would prefer to have some foundation of fact, no matter how slender, on which to build the airy and arabesque superstructure of my fancy, especially as I am writing a history. Now I hesitate to give him a wholly fictitious date of death and to invent all the work of his later years. Would it be too infernal a nuisance for you to hire one of your minions on the Advertiser (of course at my expense) to look up his life after he left the Senate in 1850?55

Lodge agreed to help, but he begged the fanciful author to check his entire text in a library. As will be seen, Roosevelt did revise the manuscript thoroughly before publication. By then he was sick of it, and doubtful as to its literary value. “I hope it is decent … I have been troubled by dreadful misgivings.”56

![]()

HIS MISGIVINGS WERE ONLY partly justified. Thomas Hart Benton (Houghton Mifflin, 1887) became Roosevelt’s third book in a row to achieve “standard” status, and was considered the definitive biography for nearly two decades.57 However it did not sell well. Contemporary critics, while generally praising it, had some harsh things to say about the author’s “muscular Christianity minus the Christian part.”58 Today the book is dismissed as historical hackwork.

This reputation is not fair. Benton may be unread, but it is not unreadable. Certainly there are long stretches of rather dogged narrative, such as the chapters devoted to the politics of nullification and redistribution of federal surplus funds. One can read the volume from cover to cover without finding out what its subject looked like. Secondary characters, such as Andrew Jackson and Daniel Webster, are merely referred to, like names in an encyclopedia. The only personality whose lusty presence stamps every page is that of Theodore Roosevelt. Herein lies the book’s main appeal, for its scholarship is so dated as to be spurious now. Roosevelt gleefully discovers many points of common identity with his subject, and in describing them, describes himself. As a testament to his developing political philosophy and theory of statesmanship, Benton is sometimes humorous, often entertaining, and, in its great climactic chapter on America’s “Manifest Destiny,” even inspiring.

The book begins with three brief chapters which explain, in prose hard and clear as glass, the evolution of “a peculiar and characteristically American type” in the West of Benton’s boyhood. Since these “tall, gaunt men, with strongly marked faces and saturnine, resolute eyes” were the recent ancestors of his own cowboys, he is able to describe them with unsentimental accuracy.

They had narrow, bitter prejudices and dislikes; the hard and dangerous lives they had led had run their character into a stern and almost forbidding mould … They felt an intense, although perhaps ignorant pride in and love for their country, and looked upon all the lands hemming in the United States as territory which they or their children should one day inherit; for they were a race of masterful spirit, and accustomed to regard with easy tolerance any but the most flagrant violations of law. They prized highly such qualities as courage, loyalty, truth and patriotism, but they were, as a whole, poor, and not over-scrupulous of the rights of others.… Their passions, once roused, were intense … There was little that was soft or outwardly attractive in their character: it was stern, rude, and hard, like the lives they led, but it was the character of those who were every inch men, and were Americans through to the very heart’s core.59

When young Senator Benton emerges as the spokesman for these people, the parallels between his own and Roosevelt’s character grow clear. They are both politicians born to articulate the longings of the inarticulate; scholars able to interpret current events in the light of ancient and Biographies & Memoirs; men of “peculiar uprightness,” of “abounding vitality and marvelous memory,” who stick to their policies with “all the tenacity of a snapping turtle.”60 Yet there are enough psychological dissimilarities between author and subject to keep the tone of the biography healthily critical. Benton is mocked for his humorlessness and pomposity, and sharply reprimanded (along with Thomas Jefferson) for hypocrisy on questions of color. “Like his fellow statesmen he failed to see the curious absurdity of supporting black slavery, and yet claiming universal suffrage for whites as a divine right, not as a mere matter of expediency … He had not learned that the majority in a democracy has no more right to tyrannize over a minority than, under a different system, the latter would to oppress the former.”61

Whenever Roosevelt, in the course of tracing Benton’s thirty years in Congress, comes upon one of his own bêtes noires, the text fairly crackles with verbal fireworks. Some of these pop-pop harmlessly, as when he castigates President Jefferson as a “scholarly, timid, and shifty doctrinaire,” and President Tyler as “a politician of monumental littleness.” Others, however, are (or were) genuinely explosive, for example his assertion that “there is no more ‘natural right’ why a man over twenty-one should vote than there is why a negro woman under eighteen should not.”62

The most controversial chapter of the book is that devoted to Benton’s doctrine of westward expansion, which Roosevelt defines as “our manifest destiny to swallow up the land of all adjoining nations who were too weak to withstand us.”63 The “Oregon” of the 1840s—an enormous wilderness stretching west from the Rockies, and north from California to Alaska—was a prize that both the United States and Britain were entitled to share. But the “arrogant attitude” of Senator Benton, in claiming most of it, “was more than justified by the destiny of the great Republic; and it would have been well for all America if we had insisted even more than we did upon the extension northward of our boundaries.” Warming to his theme, Roosevelt declares that “Columbia, Saskatchewan, and Manitoba would, as States of the American Union, hold positions incomparably more important, grander and more dignified than … as provincial dependencies of a foreign power … No foot of soil to which we had any title in the Northwest should have been given up; we were the people who could use it best, and we ought to have taken it all.”64

Roosevelt acknowledged, with an almost audible sigh, that the concept of an American Pacifica stretching from Baja California to the Bering Straits was academic in 1886. But this did not detract from Benton’s visionary greatness. In attempting to summarize it, the twenty-seven-year-old author became something of a visionary too. He could have been writing about himself, as future President of the United States, rather than the long-dead Senator from Missouri:

Many of his expressions, when talking of the greatness of our country … not only were grandiloquent in manner, but also seemed exaggerated and overwrought even as regards matter. But when we think of the interests for which he contended, as they were to become, and not as they at the moment were, the appearance of exaggeration is lost, and the intense feeling of his speeches no longer seems out of place or disproportionate … While sometimes prone to attribute to his country a greatness she was not to possess for two or three generations to come, he, nevertheless, had engrained in his very marrow and fiber the knowledge that inevitably and beyond all doubt, the coming years were to be hers. He knew that, while other nations held the past, and shared with his own the present, yet that to her belonged the still formless and unshaped future. More clearly than almost any other statesman he beheld the grandeur of the nation loom up, vast and shadowy, through the advancing years.65

![]()

ROOSEVELT PENNED THE LAST pages of Benton at Elkhorn between 29 June and 2 July 1886. He rose every day at dawn, and would stand for a moment or two on the piazza, watching the sun rise through a filter of glossy cottonwood leaves.66 Then he sat down at his desk, writing as fast as he could while the morning was still cool.67 By noon the log-cabin was too stuffy to bear, for a crippling heat-wave had struck Dakota. The grass outside, weakened by the late frosts of spring, turned prematurely brown. Mrs. Sewall’s vegetable garden began to wilt, despite frantic watering. On 4 July the temperature reached 125 degrees Fahrenheit, and an oven-like wind blew through the Badlands, killing every green thing except for a few riverside trees.68

Roosevelt was not on his ranch that morning. Along with half the cowboy population of Billings County, he “jumped” the early freight-train out of Medora, and sped east across the prairie to Dickinson.69 The little town was celebrating the 110th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence, and he had been chosen as Orator of the Day.

As he neared his destination, he could see people converging upon it from all points of the compass, on foot, on horseback, and in white-topped wagons. The streets of Dickinson itself were filled with “the largest crowd ever assembled in Stark County,” most of whom were already very drunk.70

At ten o’clock the parade got under way. So many spectators decided to join in that the sidewalks were soon deserted. The Declaration was read aloud in the public square, followed by mass singing of “My Country ‘Tis of Thee.” The crowd then adjourned to Town Hall for a free lunch. When every cowboy had eaten his considerable fill, the master of ceremonies, Dr. Stickney, introduced the afternoon’s speakers. “The Honorable Theodore Roosevelt” stood up last, looking surprisingly awkward and nervous.71

With all his boyish soul, he loved and revered the Fourth of July. The flags, the floats, the brass bands—even Thomas Jefferson’s prose somehow thrilled him. This particular Independence Day (the first ever held in Western Dakota) found him feeling especially patriotic. He was filled, not only with the spirit of Manifest Destiny, but with “the real and healthy democracy of the round-up.” The completion of another book, the modest success of his two ranches, his fame as the captor of Redhead Finnegan, the joyful thought of his impending remarriage, all conspired further to elevate his mood. These things, plus the sight of hundreds of serious, sunburned faces turned his way, brought out the best and the worst in him—his genuine love for America and Americans, and his vainglorious tendency to preach. To one sophisticated member of the audience, Roosevelt’s oration was a cliché-ridden “failure”; yet the majority of those present were profoundly affected by it. Regular roars of applause bolstered the straining, squeaky rhetoric:

Like all Americans, I like big things; big prairies, big forests and mountains, big wheat-fields, railroads, and herds of cattle too, big factories, steamboats, and everything else. But we must keep steadily in mind that no people were ever yet benefitted by riches if their prosperity corrupted their virtue … each one must do his part if we wish to show that the nation is worthy of its good fortune. Here we are not ruled over by others, as is the case in Europe; here we rule ourselves.…

Arthur Packard, who was listening intently, noticed that Roosevelt’s high voice became almost a shriek as passion took him.72

When we thus rule ourselves, we have the responsibilities of sovereigns, not of subjects. We must never exercise our rights either wickedly or thoughtlessly; we can continue to preserve them in but one possible way, by making the proper use of them. In a new portion of the country, especially here in the Far West, it is peculiarly important to do so … I am, myself, at heart as much a Westerner as an Easterner; I am proud, indeed, to be considered one of yourselves, and I address you in this rather solemn strain today, only because of my pride in you, and because your welfare, moral as well as material, is so near my heart.73

He sat down to a voluntary from the brass band. The audience cheered heartily, but briefly. Everybody was anxious to adjourn to the racecourse and watch the Cowboys take on the Indians.74

![]()

MUCH LATER THAT DAY Roosevelt and Arthur Packard sat rocking on the westbound freight to Medora, while fireworks popped in the darkening sky behind them. For a while they discussed the speech, which had greatly inspired Packard, and Roosevelt confessed his longings to return to public life. “It was during this talk,” Packard said years afterward, “that I first realized the potential bigness of the man. One could not help believing he was in deadly earnest in his consecration to the highest ideals of citizenship.”

Roosevelt told Packard that he was thinking of accepting a minor appointment which had been offered him in New York—the presidency of the Board of Health. Henry Cabot Lodge thought the job infra dig, but he was not so sure: he felt he could do his best work “in a public and political way.”

The young editor’s reaction was immediate. “Then you will become President of the United States.”75

Roosevelt did not seem in the least surprised by this remark. Indeed, Packard got the impression that he had already thought the matter over and come to the same conclusion. “If your prophecy comes true,” he said at last, “I will do my part to make a good one.”76

![]()

THREE DAYS LATER, Roosevelt left unexpectedly for New York. If he hoped to find the Board of Health job open to him, he was disappointed: the incumbent had simply refused to resign, despite an indictment for official corruption.77 Clearly little had changed for the better in municipal politics.

He spent three weeks checking the manuscript of Benton in the Astor Library, then—yet again—kissed “cunning little yellow headed Baby Lee” good-bye, and headed back to the Badlands in a mood of restless melancholy.78 It was ironic that at this time of resurgent political ambition he could see “nothing whatever ahead.”79 The city of his birth, his child, his home, his future wife, all lay behind him, pulling his thoughts back East, even as the train hauled him West. Much as he loved Dakota, he knew now that his destiny lay elsewhere: it must have been difficult to escape the feeling that he was traveling in altogether the wrong direction.

Arriving at Medora on 5 August, he found letters from Edith confirming a December wedding in London.80 From now on he could only count the days that separated him from her.

![]()

THE CRIES OF A NEWBORN BABY greeted Roosevelt at Elkhorn next day. Mrs. Sewall had just presented her husband with a son. Mrs. Dow, not to be outdone, produced a son of her own less than a week later.81 “The population of my ranch,” Roosevelt informed Bamie, “is increasing in a rather alarming manner.”82 The squalling of these two new arrivals, not to mention the jam-smeared face of little Kitty Sewall, and Elkhorn’s growing air of alien domesticity, seemed to emphasize his bachelor status and growing sense of misplacement. It was as if the house were no longer his own, and he merely the guest of his social inferiors.

Still restless, he hurried off to Mandan, where he witnessed the conviction and sentencing to three years in prison of Redhead Finnegan and the half-breed Burnsted. He withdrew his charge against Pfaffenbach, saying “he did not have enough sense to do anything good or bad.” The old man expressed fervent gratitude, and Roosevelt said that was the first time he had ever been thanked for calling somebody a fool.83

Notwithstanding his legal triumph, Roosevelt seemed to be under considerable nervous strain during the several days he spent in Mandan. A reporter from the Bismarck Tribune remarked on his “facial contortions and rapid succession of squints and gestures.”84His hosts were surprised to hear him pacing the floor of his room and groaning over and over again, “I have no constancy! I have no constancy!”85 Evidently Edith’s recent letter had evoked once again the guilty memory of Alice Lee.

About this time Roosevelt heard reports of a border clash with Mexico which, in his fertile imagination, seemed likely to lead to major hostilities.86 Instantly he conceived the idea of raising “an entire regiment of cowboys,” and wrote to Secretary of War William C. Endicott notifying him that he was “at the service of the government.” From Mandan he beseeched Lodge: “Will you tell me at once if war becomes inevitable? Out here things are so much behind hand that I might not hear the news for a week … as my chance of doing anything in the future worth doing seems to grow continually smaller I intend to grasp at every opportunity that turns up.” But Secretary Endicott decided to settle the dispute diplomatically, to Roosevelt’s obvious disappointment. “If a war had come off,” he mused wistfully, “I would surely have had behind me as utterly reckless a set of desperadoes as ever sat in the saddle.”87

![]()

THE HOT AUGUST DAYS dragged on. Plagued by a recurrent “caged wolf feeling,” Roosevelt also began to worry about Dakota’s continuing drought. It happened to coincide with record new immigrations of cattle, which his Stockmen’s Association had tried in vain to prevent. Three years before, when he first came West, the range had been overgrassed and undergrazed; now the situation was reversed.88 He began to wonder if Sewall’s forebodings about the Badlands as “not much of a cattle country” might have been justified.

Between 21 August and 18 September, Roosevelt went with Bill Merrifield on a shooting expedition to the Coeur d’Alene mountains of northern Idaho. His prey this time was “problematic bear and visionary white goat.”89 Although he managed to kill two of the latter—America’s rarest and most difficult game—he confessed that he “never felt less enthusiastic over a hunting trip.”90

On returning to Medora, Roosevelt was “savagely irritated” to read newspaper gossip that he was engaged to Edith Carow. How the secret got out is to this day a mystery. He was forced to write an embarrassed letter of confirmation to Bamie. “I am engaged toEdith and before Christmas I shall cross the ocean and marry her. You are the first person to whom I have breathed a word on this subject … I utterly disbelieve in and disapprove of second marriages; I have always considered that they argued weakness in a man’s character. You could not reproach me one half as bitterly for my inconstancy and unfaithfulness as I reproach myself. Were I sure there was a heaven my one prayer would be I might never go there, lest I should meet those I loved on earth who are dead.”91

![]()

HE WAS ANXIOUS NOW to hurry East and console Bamie, who was in agony over the prospect of losing her surrogate daughter. But an urgent matter at Elkhorn detained him. Sewall and Dow had decided, in his absence, that they wanted to terminate their contract and go back to Maine. They had been unable to sell the fall shipment of beeves profitably: the best price Chicago would offer was ten dollars less than the cost of raising and transporting each animal. Both men felt that they were “throwing away his money,” and that “the quicker he got out of there the less he would lose.”92

Roosevelt, as it happened, had reached much the same conclusion. Although he was no businessman, simple figuring told him that his $85,000 investment in the Badlands was eroding away as inexorably as the grass on the range. In any case, he was fast losing his enthusiasm for ranching. Bill Merrifield and Sylvane Ferris could take the Elkhorn herd over; in future he would use the ranch house only as a stopover when checking on his cattle, or as a hunting base. His reaction to Sewall’s ultimatum, therefore, was mild. “How soon can you go?”93

While the three friends sat squaring their accounts that last week of September, a strange, soft haze settled over the Badlands, reducing trees and cattle to pale blue silhouettes.94 Weathermen dismissed the haze as an accumulation of fumes from the grass-fires that had smoldered all summer on the tinder-dry plains. Yet its strangeness made cowboys and animals uneasy. Although the heat was still tremendous, old-timers began to lay in six months’ supply of winter provisions, muttering that “nature was fixin’ up her folks for hard times.”95 Beavers worked double shifts cutting and storing their lengths of willow brush; muskrats grew extra-thick coats and built their reed houses twice the usual height. Roosevelt, casting his ornithologist’s eye out of the window, noticed that the wild geese and songsters were hurrying south weeks earlier than usual. He may have heard rumors that the white Arctic owl had been seen in Montana, but only the Indians knew what that sign portended.96

![]()

SEWALL AND DOW were not ready to move their wives, babies, and baggage out of the ranch before 9 October. By then their impatient boss had already departed for the East. It was left to Sewall to close up the great log cabin and slam the door on what even he, in later life, would recall as “the happiest time that any of us have ever known.”97

And so silence returned to the Elkhorn bottom, broken only by the worried chomping of beavers down by the river.