Sing me a song divine

With a sword in every line!

![]()

ON 28 MARCH 1887, New York newspapers headlined the return of Theodore Roosevelt and his “charming young wife” to the United States, after a fifteen-week tour of England, France, and Italy.1 Every reporter commented on how well Roosevelt looked, in contrast to the drained and defeated mayoral candidate of last fall. His face was “bronzed,” even “handsome,” and he gave off “a rich glow of health” as he strode down the gangplank of the Etruria. A certain bearish heaviness was noticeable in his physique (he had put on considerable weight in European restaurants), and several friends were seen to wince as he exuberantly hugged them tight.2

Edith’s health was rather more delicate than her husband’s. In Paris, about halfway through their trip, she had begun to feel “the reverse of brightly,” and Theodore had hinted in his next letter home that a honeymoon baby was on its way.3 This had not stopped them accepting a flood of fashionable invitations during their last weeks in London. There had been Parliamentary visits with members of both Houses (Roosevelt remarking sourly, of some Irish Parnellites, that he had met them before—“in the New York legislature”); lunches, dinners, and teas with a variety of British intellectuals; supper with the Prime Minister, Lord Salisbury; and, by way of climax, a sumptuous weekend at Wroxton Abbey in Warwickshire, where the honeymooners slept in the Duke of Clarence’s bed and were waited on by powder-wigged servants.4

“A longing for nobler game soon overwhelmed him.”

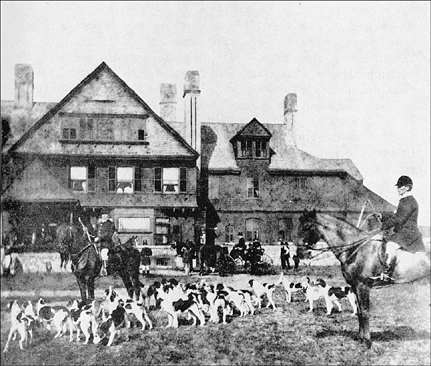

The Meadowbrook Hunt meeting at Sagamore Hill in the 1880s. (Illustration 15.1)

“I have had a roaring good time,” Roosevelt told the New York press. Pacing up and down, and tugging excitedly at his pince-nez, he said how glad he was, nevertheless, to be home. Having met “all the great political leaders,” and made “as complete a study as I could of English politics,” he was convinced that the American governmental system was superior. “Why, Mr. Roosevelt?” asked a Herald reporter. “Because a written constitution is better than an unwritten one. Their whole system seemed clumsy. It might do well enough for a social club, but not for a great legislative body.”

In answer to the inevitable questions about his political plans, Roosevelt said he had none—at present. “I intend to divide my time between literature and ranching.”5

![]()

HAD HE OPENED HIS MAIL from Medora before talking to the press that afternoon, he might well have dropped the latter option. Vague news of the Dakota blizzards had reached him in Europe, but the true extent of the devastation had become apparent only during his return voyage. Even now, with the spring thaw still going on, Merrifield and Ferris were unable to tell him how many cattle had been lost. They urged him to hurry West and judge the situation for himself.

Roosevelt was plainly anxious to leave right away, but he had to spend at least a week in New York with his wife and sister and “sweet Baby Lee.” It was a period of difficult adjustment among them. The decision had been made in Europe that Bamie might not, after all, keep her adored foster daughter.6 Before remarrying, Theodore had more than once reassured Bamie that the child would stay with her, “I of course paying the expenses.”7 But when Edith heard about the arrangement, she had reacted with surprising vehemence. Little Alice was her child now, she insisted, and would live at Sagamore Hill, where she belonged. In a rare display of helplessness, Roosevelt had thrown up his hands. “We can decide it all when we meet.”8

What was decided, in those waning days of March, was that to ease the pain of parting, Baby Lee would remain with Bamie for another month. Meanwhile her father would go West, and Edith visit relatives in Philadelphia. Upon their return to New York at the end of April, they would take over Bamie’s new house at 689 Madison Avenue, while its mistress went South for a short vacation. By the time she got back in late May the Roosevelts would have opened Sagamore Hill, and they could all move out there for the summer. Together they would spend June and July supervising the delicate task of transferring the child’s affections from aunt to stepmother.9 Not until August, therefore, need Bamie face the prospect of resuming her lonely spinster life.

Bamie accepted that Edith’s instinct was the right one—she had never felt entirely secure in her surrogate role—but relations between the two women would never be the same now that they were sisters-in-law. For all their determined sweetness to each other, neither could forget that Bamie had nursed little Alice through her first years of life,10 and that Bamie had been the first mistress of Sagamore Hill. Corinne, too, was to learn that she now had a formidable rival to her brother’s affections and that access to him would henceforth be strictly controlled.11 It was an ironic reversal for someone who, not so long ago, had served as duenna between Edith and the teenage Theodore.

Two welcome guests at 689 helped smooth things over while negotiations over Baby Lee went on: Congressman Henry Cabot Lodge and “Springy” Spring Rice, now Secretary of the British Legation in Washington. Roosevelt seized on their masculine company with some relief, and lost no time in returning Spring Rice’s hospitality of the previous November. The Englishman became an honorary member of the Century Club, which he found as intellectually exclusive as the Savile, and was introduced to an enormous circle of Rooseveltian acquaintances. One morning Whitelaw Reid, the immensely rich and influential owner of the New York Tribune, invited the three friends to a political breakfast in his mansion. There, in a magnificent dining hall, paneled with inlaid wood and embossed leather, Roosevelt, Lodge, and Reid gravely discussed whether or not James G. Blaine should again be nominated for the Presidency in 1888. Spring Rice listened in utter fascination. “It was the first real piece of political wire-pulling I had come across,” he wrote home afterward. “I am getting quite excited over it.”12

Not until 4 April was Roosevelt free to go West and find out exactly how poor he was.

![]()

HE ALREADY HAD a fairly accurate idea. Or rather, Edith had. That level-headed lady knew that her husband, whatever his other talents, was a financial imbecile.13 Soon after the wedding she had gone over his affairs with him and discovered that, on the basis of last year’s figures alone, they should “think very seriously of closing Sagamore Hill.” Then had come the first reports of Dakota blizzards, followed by her attacks of morning sickness. Clearly, if they were to rear their family at Oyster Bay, they would have to “cut down tremendously along the whole line.”14 Roosevelt must learn to live within his income for a change, and begin to pay off his debts. He must sell his enormously expensive hunting-horse, grow his own crops and fodder (for Sagamore Hill was a potentially profitable farm), and stop running the house as a summer resort for friends with large appetites, and thirsts to match.15

As to his cattle business, the winter’s toll was still a matter of guesswork. Roosevelt could only hope that enough cows would survive to produce at least a token number of healthy calves. In the years ahead he would sell as many beeves as possible for whatever price he could get, and so slowly reduce his losses. Given enough time—and no more freak weather—he might be able to dispose of his entire stock and save most of his $85,000 investment.

But now, as he rode once more out of Medora into the devastated Badlands, all such optimism vanished. “The land was a mere barren waste; not a green thing could be seen; the dead grass eaten off till the country looked as if it had been shaved with a razor.” Occasionally, in some sheltered spot, he would come across “a band of gaunt, hollow-flanked cattle feebly cropping the sparse, dry pasturage, too listless to move out of the way.” Blackened carcasses lay piled up against the bluffs: he counted twenty-three in a single patch of brushwood. Here and there a dead cow perched grotesquely in the branches of a cottonwood tree, the high snow upon which it once stood having melted away.16

Of the once-teeming Elkhorn and Maltese Cross herds, only “a skinny sorry-looking crew” of some few hundred seemed to have survived.17 He could not find out exactly how many had died until after the spring roundup.

But the roundup was never held. The Little Missouri Stockmen’s Association, meeting on 16 April with Roosevelt in the chair, decided that losses were too heavy to merit a general mobilization. There were so few cattle left on the range, ranchers might as well sort them out individually. One search party was dispatched to Standing Rock, in the hope that some thousands of cattle may have migrated south, and returned after three weeks, with exactly two steers.18

No official figures, therefore, survive as to the effect of the winter of 1886–87 on the Badlands cattle industry as a whole, nor on Roosevelt in particular. Estimates of the average loss sustained by local ranchers range from 75 percent to 85 percent.19 Gregor Lang, who began the winter with three thousand head, ended it with less than four hundred. Thanks to the thickly wooded bottoms on both of Roosevelt’s properties, his loss was probably about 65 percent. Even so, it was catastrophic.20 “I am bluer than indigo about the cattle,” he wrote Bamie from Medora. “It is even worse than I feared. I wish I was sure I would lose no more than half the money ($80,000) I invested here.21 I am planning to get out of it.” And on 20 April, after attending another gloomy stockmen’s meeting in Montana, he wrote Lodge, “The losses are crippling. For the first time I have been utterly unable to enjoy a visit to my ranch. I shall be glad to get home.”22

![]()

THE SPRING AIR WAS WARM, and blades of grass had begun to stipple the bare hills, when Roosevelt left Medora a few days later. But an air of wintry lifelessness still hung over the little cow-town. Already most of its citizens had departed to seek their fortunes elsewhere. Arthur Packard had abandoned the Bad Lands Cowboy, and his office was now a fire-blackened ruin. E. G. Paddock had moved to Dickinson, taking the old Pyramid Park Hotel with him on a flat-car. “Blood-Raw John” Warns offered no more “choice Western cuisine” in his Oyster Grotto, and Genial Jim’s Billiard Bar had run dry of Conversation Juice. Sad clouds of steam still floated out of Yach Wah’s Chinese Laundry, but he, too, would soon pack up his washboards and go.23

Most symbolic of all was the shuttered-up bulk of the Marquis de Morès’s slaughterhouse. Its doors had closed in November 1886, never to reopen. Even when Medora was booming, the Marquis had been unable to run his giant scheme at a profit. The supply of local steers was simply insufficient, and rangy, refrigerated beef had never appealed to the Eastern consumer.24 Impatiently shrugging off an estimated loss of $1 million, de Morès had gone off to dig a goldmine in Montana. When last seen—heading East as Roosevelt came West—he had been planning to build a railroad across China.25

In less than two years, Medora would become a ghost town, while Dickinson flourished, and a checkerboard of small, fenced-in ranches spread west across the prairie.26 Roosevelt had foreseen the destruction of Dakota’s open-range cattle industry in Hunting Trips of a Ranchman,27 but he had not expected it to come so soon, nor that Nature would conspire to accelerate the process.

Although his Dakota venture had impoverished him, he was nevertheless rich in nonmonetary dividends. He had gone West sickly, foppish, and racked with personal despair; during his time there he had built a massive body, repaired his soul, and learned to live on equal terms with men poorer and rougher than himself. He had broken horses with Hashknife Simpson, joined in discordant choruses to the accompaniment of Fiddlin’ Joe’s violin, discussed homicidal techniques with Bat Masterson, shared greasy blankets with Modesty Carter, shown Bronco Charlie Miller how to “gentle” a horse, and told Hell-Roaring Bill Jones to shut his foul mouth.28 These men, in turn, had found him to be the leader they craved in that lawless land, a superior being, who, paradoxically, did not make them feel inferior.29 They loved him so much they would follow him anywhere, to death if necessary—as some eventually did.30 They and their kind, multiplied seven millionfold across the country, became his natural constituency.31 “If it had not been for my years in North Dakota,” he said long afterward, “I never would have become President of the United States.”32

![]()

ROOSEVELT’S ASSERTION, on stepping off the S.S. Etruria, that he had no political plans “at present” impressed nobody. Yet for once the protestation was true. With a Democratic President in Washington, a Democratic Governor in Albany, and a Democratic Mayor in New York, his prospects for any kind of office were nil, at least through the election of 1888. And there was no guarantee that the Republican party would fare any better then than it had in 1884.

Every day saw a further strengthening of the opposition’s grip upon every lever of government.33 Quietly, ruthlessly, the Civil Service was being purged. Cleveland had promised, upon assuming office, that only those Republicans who were “offensive, indolent, and corrupt” would be dismissed. But the President’s aides saw fit to interpret such adjectives loosely: already two-thirds of the entire federal bureaucracy had been replaced.34

Although Cleveland was as stiff as ever in public, and openly contemptuous of the press, he had to a certain degree become popular. Labor respected him as the most industrious Chief Executive in living memory. Often as not his was the last light burning on Pennsylvania Avenue, as many a night watchman could testify. Capital admired his conservative attitude to all legislation, from multimillion-dollar appropriations to private pension bills; every Cleveland veto (and there were literally hundreds)35 meant more wealth in the nation’s coffers. Meanwhile that largest and most powerful voting bloc in America, Parlor Sentiment, had canonized the President for his sudden marriage to a pretty debutante half his age—and about one-third of his weight.36 Mrs. Cleveland was now the country’s sweetheart, and would undoubtedly prove a formidable campaign asset in 1888.

Indeed, at this midway point in Cleveland’s Administration, the Democratic party seemed assured of another six years in power. For an impatient and idealistic young Republican like Roosevelt, the spring of 1887 was a time of complete frustration.

The message was clear: he must once again forget about politics and seek surcease in literature. For the foreseeable future, he would have to earn a living with his pen.

![]()

ONE FINAL POLITICAL HURRAH was permitted him, at Delmonico’s Restaurant on 11 May, and he made the most of it. The occasion was the Inaugural Banquet of the New York Federal Club. This organization had been founded in the New Year by some of Roosevelt’s mayoral campaign supporters, with the object of keeping Reform Republicanism alive. Its membership consisted largely of young “dudes” from his old brownstone district.37 They were men he had, on the whole, grown away from, but he could not ignore their support, nor their invitation to be guest of honor.

Originally the dinner was planned as a semiprivate affair of some fifty covers, but when it was announced in the papers an unusual number of ticket applications poured in from Republicans all over the state. The event, remarked The New York Times, “bade fair to assume as wide political significance as any this year.”38 A limit was set at 150 admissions, but when Roosevelt arrived at Delmonico’s he found over 200 guests sitting at six lavishly appointed tables. The company was, in the words of a Sun reporter, “brilliant and distinguished enough to have been a compliment to a veteran statesman.”39

Roosevelt was introduced after the coffee and cigars as “the man who, had the Republicans stood to their guns last fall, would now be the Mayor of this city.” Loud cheers greeted him as he stood up—looking, as he always did when preparing to speak, grim, resolute, tense as a bundle of wire.40 The knowledge that Edith was watching from the Ladies’ Gallery no doubt made him extra conscious of his dignity.

If his fellow diners expected a relaxed and humorous speech—for Charles Delmonico had not stinted on the champagne, and they were in a convivial mood—Roosevelt soon disillusioned them. He began by remarking sardonically that during the mayoralty campaign he had been praised as a party faithful; now, however, he was regarded as a member “of the extreme left.” (Here there was some uneasy laughter among senior Republicans.) He proceeded to attack such a wide variety of targets that his listeners must have wondered if there was anything in the State of the Union that he approved of. President Cleveland was castigated for his clumsy English and “sheer hypocrisy” in the cause of Civil Service Reform;41 the Independent press for its “thoroughly feminine” waywardness and “high-pitched screechings”; the Immigration Department for its unrestricted admission of “moral paupers and lunatics”; the Anti-Poverty Society for being “about as effective as an Anti-Gravitation Society”; anarchists and socialists for inciting labor demonstrators to violence (“there is but one answer to be made to the dynamite bomb, and that can best be made by the Winchester rifle”). For nearly an hour Roosevelt’s voice grated through the cigar-smoke. Again and again he hurled insults at the “hysterical and mendacious party of mugwumps,” even managing, somewhat anachronistically, to include Presidents Tyler and Johnson in that number “—and they were the most contemptible Presidents we have ever had.”

He sat down to considerable applause, although the faces of his listeners registered rather more shock than approval—as if they had been witnessing a bloody prizefight, and were relieved the punishment was over. For all the savagery of Roosevelt’s language, his personal force awed the gathering. Chauncey Depew rose to make some flattering follow-up remarks. “Buffalo Bill said to me in the utmost confidence, ‘Theodore Roosevelt is the only New York dude that has got the making of a man in him.’ ” Depew waggishly announced that the evening’s other scheduled speakers had all submitted their manuscripts to Roosevelt for checking, “so that when he runs for President no case of Burchard will interfere.”42 This was a reference to the unfortunate preacher whose gaffe had cost James G. Blaine the 1884 election.

Waggish or not, Depew was the first person ever to suggest in public that Roosevelt might be harboring presidential ambitions.43 The young man’s speech made nationwide headlines, and the question of his future was taken up seriously by several Republican newspapers. The Harrisburg Telegraph recommended him for Vice-President in 1888, on a ticket headed by Governor Foraker of Ohio;44 the Baltimore American went so far as to nominate him for President. “Mr. ROOSEVELT,” the paper commented, “has a stainless reputation and great personal magnetism. He is a tireless worker, an advocate of real reform in politics, and his speech before the Federal Club fairly reflects his ability to handle the political puzzles with which both parties must deal next year. It may be that the Federal Club have builded wiser than they intended by thus prominently drawing the attention of the country to this vigorous young Republican.”45

Few out-of-town editors, evidently, realized that Roosevelt was still only twenty-eight, and constitutionally debarred from the greatness they would thrust upon him. The New York Sun felt obliged to point out that, “owing to circumstances beyond his control, he will not be able to take the office of President of the United States before 1897.”46

Major newspapers, of course, paid no attention to such preposterous endorsements. They were (with the single exception of Whitelaw Reid’s Tribune) harshly disapproving of Roosevelt’s “vehement chatter.”47 He was “an immature and poorly posted thinker,” wasting “a good deal of breath which he may want someday” on “strained criticism” of the government.48 Even the Times, hitherto his most fervent supporter, admitted the speech had been “most unfortunate and disagreeable.”49 E. L. Godkin of the Post wrote that the Republican party no longer had any use for Theodore Roosevelt. “It was a mistake ever to take him seriously as a politician.”50 And on 25 May, Puck published a final valedictory:

Be happy, Mr. Roosevelt, be happy while you may. You are young—yours is the time of roses—the time of illusions … You have heard of Pitt, of Alexander Hamilton, of Randolph Churchill, and of other men who were young and yet who, so to speak, got there just the same. Bright visions float before your eyes of what the Party can and may do for you. We wish you a gradual and gentle awakening … You are not the timber of which Presidents are made.

![]()

THE SPRING OF 1887 settled down on Oyster Bay. Bloodroot and mayflower whitened the slopes around Cove Neck; on Sagamore Hill, the saplings were feathery green against the sky, noticeably taller than last year. Two woolly horses began to plow the fields behind the house.51

Inside, Theodore and Edith unhooked shutters, pulled dust-sheets off beds and sofas, and distributed the latest batch of hunting-trophies from Dakota (already the walls were forested with antlers, and snarling bear-jaws caught the unwary foot). They crammed some very big pieces of oak furniture into the very small dining room, and Edith, insisting that at least one corner of the house should be allowed to look feminine, arranged some rather more delicate furniture in the west parlor.52

Theodore’s own retreat, which none could visit without his permission,53 was a pleasantly cluttered room on the top floor, full of guns and sporting books and photographs of his ranches. There was a desk rammed against a blind wall, so that when he sat down to work he would not be distracted by the sight of Long Island Sound brimming blue in the window. Here, sometime early in June, he dipped a steel pen into an inkwell and began to write his fourth book. By the time the nib needed recharging he was already 135 years back in the past, in the New York City of his forebears—

a thriving little trading town, whose people in summer suffered much from the mosquitoes that came back with the cows when they were driven home at nightfall for milking; while from the locusts and water-beeches that lined the pleasant, quiet streets, the tree-frogs sang so shrilly through the long, hot evenings that a man in speaking could hardly make himself heard.54

![]()

GOUVERNEUR MORRIS, WHICH Roosevelt worked on steadily throughout the summer of 1887, was a companion biography to his Thomas Hart Benton in the American Statesmen series. The critical success of the earlier book had prompted Houghton Mifflin to commission another study of a neglected historical figure. Only one life of Morris had hitherto been published—a ponderous tome now half a century out of date. It was time, the editors felt, for their breezy young author to blow the dust off Morris’s letters and diaries, and subject the great New Yorker to a fresh scrutiny.55

With his powdered wig and peg-leg, his coruscating wit and picaresque adventures, Morris (1752–1816) was a biographer’s dream. There was about him, Roosevelt remarked, “that ‘touch of the purple’ which is always so strongly attractive.”56 Well-born, well-bred, charming, literate, and widely traveled, he had been a strong believer in centralized government, an aggressive moralist, and a passionate patriot. All these characteristics were shared, to varying degrees, by Roosevelt himself. Yet, as with Benton, there were enough antipathetic elements to keep the portrait objective.

Unfortunately a major obstacle loomed early in Roosevelt’s research. “The Morrises won’t let me see the old gentleman’s papers at any price,” he complained to Cabot Lodge. “I am in rather a quandary.”57 Being in no position to pay back his advance, he resolved to make what he could of public documents. Fortunately these were copious,58 and the complete manuscript was ready for the printer by 4 September.59

![]()

AS HISTORY, the first five chapters of Gouverneur Morris are adequate but unrewarding; as biography they are tedious. Roosevelt’s lack of family material forces him to weave the thread of Morris’s early life (1752–86) into a general tapestry of the Revolutionary period. The resultant cloth is drab, for he seems determined, as in The Naval War of 1812, to avoid any hint of romantic color. Only a couple of pages devoted to Morris as the founder of the national coinage are worth reading for their lucid treatment of a complex subject.60 Matters become more interesting in chapter 6, “The Formation of the National Constitution.” Now the author has access to official transcripts, and can ponder the actual speeches of Washington, Franklin, Hamilton, Madison, and the two Morrises (Gouverneur and Robert). “Rarely in the world’s history,” he concludes, “has there been a deliberative body which contained so many remarkable men.”61

Morris is presented as the Constitution’s most brilliant intellect, as well as its dominant conservative force. Yet the narrative clearly shows why he was doomed never to rise to the first rank of statesmen:

His keen, masterful mind, his far-sightedness, and the force and subtlety of his reasoning were all marred by his incurable cynicism and deep-rooted distrust of all mankind. He throughout appears as advocatus diaboli; he puts the lowest interpretation upon every act, and frankly avows his disbelief in all generous and unselfish motives … Morris championed a strong national government, wherein he was right; but he also championed a system of class representation, leaning toward aristocracy, wherein he was wrong.62

Nevertheless Morris is commended for his “thoroughgoing nationalism,” and for his prophecy of an emergent America whose glories would make the grandest empire of Europe seem “but a bauble” in comparison. Roosevelt also praises his early espousal of the doctrine of emancipation. There are flashes of dry humor, as in the following explanation of Morris’s acquisitiveness: “He considered the preservation of property as being the distinguishing object of civilization, as liberty was sufficiently guaranteed even by savagery.”63

The book comes brilliantly to life in its penultimate section, describing Morris’s ten years in London and Paris, 1789–98, and his not-so-neutral participation in the major events of the French Revolution. Roosevelt was doubtless inspired by his own recent stays in those same cities, and his prose sparkles with true Gallic éclat. Chapters 7 through 11 are the best stretch of pure biography he ever wrote. Morris’s courtly flirtations with Mmes. de Staël, de Flahant, and the Duchesse d’Orléans; his plot to smuggle Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette out of Paris after the fall of the Bastille; the bloody riots of 10 August 1792, when he was the only foreign diplomat left in Paris, and gave sanctuary to veterans of the War of American Independence—all these episodes read like Dumas. Only the occasional jarring reference to municipal corruption in New York City, and sideswipes at the “helpless” Jefferson and that “filthy little atheist” Thomas Paine remind us of the true identity of the writer.64

The biography ends with two brief chapters tracing Morris’s decline into cantankerous old age. There are hints of certain “treasonous” tendencies during these “discreditable and unworthy” last years (Morris had been part of a Federalist group contemplating secession from the Union in 1812). Yet, in a final-page summary of the whole life, Roosevelt is willing to bestow his highest praise upon Gouverneur Morris. “He was essentially a strong man, and he was American through and through.”65

![]()

REVIEWS WERE NEGATIVE when Morris came out the following spring. The Book Buyer felt that there had been insufficient character analysis, and complained of some “rather dry” stretches of prose. The New York Times commented, “Mr. Roosevelt has no style as style is understood,” but allowed that “his meaning is never to be mistaken.” The Dial, while praising him for “an exceedingly interesting narrative, artistic in its selection, forcible in its pungent expression,” called his scholarship “rather more brilliant than sound,” and said that his irreverent treatment of the American Revolution, not to mention certain “slurs” upon eminent men of the past, were “beneath the gravity of historical writing.”66 It was generally agreed that Gouverneur Morris was clever, patchy, and superficial—a verdict which posterity can only endorse.

![]()

ROOSEVELT’S “STRAITENED FINANCES” made the summer of 1887 an uneventful one.67 He was kept from being too restless by the intensity of his work on Morris (the 92,000-word manuscript was researched and written in little over three months). Sometimes he took a day off to row his pregnant wife to a secluded spot in the marshes, where they would picnic and read to each other.68 For other recreation, he chopped wood, played tennis (winning the local doubles championship and promptly splurging his share of the “cup” on a new Winchester), taught himself the rudiments of polo, and now and then allowed his hunting-horse to “hop sedately over a small fence.” There were many wild romps on the piazza with Baby Lee, who was now an enchantingly pretty little girl of three. His letters are full of fond anecdotes about “the blue-eyed offspring” and “yellow-haired darling.”69

The only recorded houseguests to Sagamore Hill in 1887 were Bamie, the Douglas Robinsons, and Cecil Spring Rice. Roosevelt’s happiness in being remarried and settled at last en famille warmed them all, and sent them away glowing. Spring Rice went back to Washington vowing that he liked Theodore “better every day I see him.”70

By late summer Roosevelt had worked himself into a state of such nervous excitement over Morris, and Edith’s approaching confinement, that he was felled by a surprise recurrence of asthma. The arrival of an eight-and-a-half-pound baby on 13 September seems to have shocked him back into health. Later that day, in a letter announcing the birth, he proudly added the word “Senior” to his signature.71

In October the hunting season got under way. Roosevelt pounded energetically after Long Island fox, but a longing for nobler game soon overwhelmed him. It had been more than a year since he had killed anything substantial. His herds in Dakota offered a convenient pretext for another trip West. Early in November, therefore, he set off with a cousin and a friend for five weeks’ ranching and shooting in the Badlands.72

Ten days of “rough work” on the range were enough for his two companions, who hurried back to New York on 14 November. He was not sorry to see them go. “As you know,” he wrote Bamie, “I really prefer to be alone while on a hunting trip.”73 Little is known about his wanderings during the next three weeks. One can only speculate, but during that solitary period some shock seems to have awakened a long-dormant instinct in Theodore Roosevelt—prompting him to take certain actions immediately after returning East.

The speculation is that as he rode farther and farther afield, he found the Badlands virtually denuded of big game—although he did manage, by an extraordinary fluke, to kill two black-tailed deer with one bullet.74 Even in 1883 he had been hard put to find any buffalo this side of Montana; a year later the elk and grizzly were gone. In 1885 he had complained that bighorn and pronghorn were becoming scarcer, and in 1886 noticed that some varieties of migratory birds had failed to return to the Little Missouri Valley.75 All this was due to the white man’s guns and bricks and fences. Roosevelt had regretted the loss of local wildlife, but he took the conventional attitude that some dislocation of the environment must occur when civilization enters a wilderness. One day, perhaps, a new balance of nature would be worked out.…

Now, in November 1887, it was frighteningly obvious that both the flora and the fauna of the Badlands were facing destruction. There were so few beavers left, after a decade of remorseless trapping, that no new dams had been built, and the old ones were letting go; wherever this happened, ponds full of fish and wildfowl degenerated into dry, crack-bottomed creeks. Last summer’s overstocking, together with desperate foraging during the blizzards, had eroded the rich carpet of grass that once held the soil in place. Sour deposits of cow-dung had poisoned the roots of wild-plum bushes, so that they no longer bore fruit; clear springs had been trampled into filthy sloughs; large tracts of land threatened to become desert.76 What had once been a teeming natural paradise, loud with snorts and splashings and drumming hooves,77 was now a waste of naked hills and silent ravines.

It would be hard to imagine a sight more melancholy to Roosevelt, who professed to love the animals he killed. For the first time he realized the true plight of the native American quadrupeds, fleeing ever westward, in ever smaller numbers, from men like himself. Ironically, he had always been at heart a conservationist. At nine years old he was “sorry the trees have been cut down,”78 and his juvenile hobby of taxidermy, though bloody, was in its way a passionate sort of preservation. His teenage slaughter of birds had been scientifically motivated; only as a young adult had he learned to kill for the “strong eager pleasure” of it.79 Even then he always insisted that a certain amount of hunting by responsible sportsmen was necessary to keep fecund species from multiplying at the expense of others.80 But by 1887 the ravages of “swinish game-butchers” (and could he, in all conscience, exclude himself from that category?) were plain to see; the only thriving species in Western Dakota were wolves and coyotes.81 Roosevelt was now in his twenty-ninth year, and the father of a small son; if only for young Ted’s sake, he must do something to preserve the great game animals from extinction.

![]()

HE ARRIVED BACK in New York on 8 December, and lost no time in inviting a dozen wealthy and influential animal-lovers to dine with him at 689 Madison Avenue. Chief among these was George Bird Grinnell, editor of Forest and Stream, and a crusader against the wanton killing of wildlife on the frontier. He had become Roosevelt’s close friend after printing a complimentary review of Hunting Trips of a Ranchman; the two men had already spent many evenings together discussing “in a vague way” the threat to various American species. But, as Grinnell afterward explained, “We did not comprehend its imminence and the impending completeness of the extermination … those who were concerned to protect native life were still uncertainly trying to find out what they could most effectively do, how they could do it, and what dangers it was necessary to fight first.”82

Roosevelt now decisively answered these questions. His twelve dinner guests must join him in the establishment of an association of amateur riflemen who, notwithstanding their devotion to “manly sport with the rifle,” would “work for the preservation of the large game of this country, further legislation for that purpose, and assist in enforcing existing laws.”83 The club would be named after Daniel Boone and Davy Crockett, two of Roosevelt’s personal heroes, and would encourage further explorations of the American wilderness in their honor. Other objectives would be “inquiry into and the recording of observations on the natural history of wild animals,” and “the preservation of forest regions … as nurseries and reservations for woodland creatures which else would die out before the march of settlement.”84 From time to time the club would publish books and articles to propagate its ideals.

The proposal was approved, and in January 1888 the Boone & Crockett Club was formally organized with Theodore Roosevelt as its president. It was the first such club in the United States, and, according to Grinnell, “perhaps in any country.” Membership rapidly grew to a total of ninety, including some of the nation’s most eminent scientists, lawyers, and politicians. Through them Roosevelt (who remained club president until 1894) was able to wield considerable influence in Congress.85

Among his first acts was to appoint a Committee on Parks, which was instrumental in the creation of the National Zoo in Washington. He ordered another committee to work with the Secretary of the Interior “to promote useful and proper legislation towards the enlargement and better government of the Yellowstone National Park”—then a sick environment swarming with commercial parasites. The resultant Park Protection Act of 1894 saved Yellowstone from ecological destruction. Still other Boone & Crockett committees helped establish zoological gardens in New York, protect sequoia groves in California, and create an Alaskan island reserve “for the propagation of seals, salmon, and sea birds.”86

When he was not working on these committees himself, Roosevelt joined forces with Grinnell in editing and publishing three fat volumes of wilderness lore, written by club members. American Big-Game Hunting (1893), Hunting in Many Lands (1895), andTrail and Camp-Fire (1897) won acclaim on both sides of the Atlantic, and prompted the establishment of Boone & Crockett-type clubs in England and various parts of the British Empire.87 A glance at Roosevelt’s own contributions as an author shows that he by no means lost his relish for blood sports. It remained strong in him through old age, although an apologist claims “he then no longer spoke of hunting as a pleasure, rather an undertaking in the interest of science.”88 Roosevelt was a complex man, and, as will be seen, his complexity grew apace during the middle years of his life. But as founder and president of the Boone & Crockett Club, he was the prime motivational force behind its conservation efforts.89

The most significant, from his own point of view as well as the nation’s, was to do not with animals but with forestry. Roosevelt had a profound, almost Indian veneration for trees, particularly the giant conifers he had encountered in the Rockies.90 Walking on silent, moccasined feet down a luminous nave of pines, listening to invisible choirs of birds, he came close to religious rapture, as many passages in his books and letters attest. Hence, when the American Forestry Association began its struggle to halt the rapid attrition of Western woodlands, Roosevelt threw the full weight of his organization behind it. Thanks to the club’s determined lobbying on Capitol Hill, in concert with other environmental groups, the Forest Reserve Act became law in March 1891. It empowered the President to set aside at will any wooded or partly wooded country, “whether of commercial value or not.”91 The time would come when Theodore Roosevelt joyfully inherited this very power as President of the United States. One wonders if he ever paused, while signing millions of green acres into perpetuity, to acknowledge his debt to the youthful president of the Boone & Crockett Club.

![]()

ABOUT THE SAME TIME that Roosevelt sat discussing big-game preservation with his dozen dinner guests, President Cleveland dumbfounded Congress with the first Annual Message ever devoted to one subject. The tariff bulked even larger than Civil Service Reform as a political issue in those last days of 1887; as will be seen, the two major parties were diametrically opposed in their attitudes toward it. To provoke a similar division of opinion in the electorate, as Cleveland did by publicly coming out against the tariff, was in effect to decide the result of the next national election, still eleven months off. Republicans reading the text of his message reacted with incredulous joy, while Democrats wondered privately if the Big One had gone mad.92

Simply described, the tariff was a system of laws, hallowed for decades by successive Republican administrations, which levied high duties on imported goods in order to protect American industry and provide revenues for the federal government. So vast were these revenues (about two-thirds of the nation’s income) that a surplus had been building up in the Treasury every year since 1879. It now waxed enormous,93 and President Cleveland believed that it posed a malignant threat to the economy. To spend excessive money was wasteful; yet to hoard it, when it could have been in healthy circulation, was even more so. Cleveland, having silently pondered American tariff schedules for two years, decided that they were “vicious, inequitable and illogical.” Congress was instructed to reduce most rates, and abolish others altogether: wool, for example, should be allowed to come in free. The tariff, wrote Cleveland, would be “for revenue only” and not for protection.94

By his unfortunate use of the word “free” the President thus laid himself open to charges that he was a Free Trader, while by attacking Protection he identified that comfortable doctrine with the Republican party. “There’s one more President for us in Protection,” crowed James G. Blaine,95 leaving few observers in doubt as to which President he had in mind. A wave of optimism spread through the party as bells across the country rang in another election year.96

But Roosevelt remained in the pessimistic minority. His political instinct told him the tariff was too complex an issue to divide the electorate neatly.97 He had to admit that Blaine was a certainty for renomination, and stood at least an even chance of being elected. This made Roosevelt’s own hopes for appointive office even more forlorn than they had been the previous spring. President Blaine would be no more likely to favor him than President Cleveland. The Plumed Knight was a man of long memory: he would not forget the rejection of his advances in the mayoral campaign of 1886.

“I shall probably never be in politics again,” Roosevelt wrote sadly to an old Assembly friend. “My literary work occupies a good deal of my time; and I have on the whole done fairly well at it; I should like to write some book that would really take rank in the very first class, but I suppose this is a mere dream.”

![]()

THUS, IN A CRYPTIC CONFESSION dated 15 January 1888,98 did Roosevelt give his first hint that he was musing the major work of scholarship that would preoccupy him for the next seven years. Four volumes, perhaps eight, would be required to do the subject justice: his theme was enormous but vague. Within its blurry parameters (conforming roughly with the shape of the United States), he began to see heroic figures fighting, moving, pointing in one general direction.

The process of literary inspiration does not admit of much analysis. Writers themselves are often at a loss to say just when or why a given idea takes possession of them. Roosevelt, certainly, never indulged in such speculation.99 Yet it is possible to mention at least some of the fertilizing influences upon what he proudly called “my magnum opus.”100 In those first weeks of 1888 he happened to be checking through a batch of page proofs from England, comprising several chapters of The American Commonweath, by James Bryce, M.P., whom he had met in London the previous winter. Bryce wanted his expert opinion on various passages dealing with municipal corruption. As Roosevelt read the proofs through, he realized that he held a masterpiece in his hands. It was, he decided, the most epochal study of American institutions since that of de Tocqueville; it made his own Gouverneur Morris (whose galleys also lay upon his desk) seem pathetically trivial in comparison.101 Bryce’s reference to him, in a footnote, as “one of the ablest and most vivacious of the younger generation of American politicians” was flattering but ironic, given the present stagnation of his political career; it only served to increase his yearning to write a work “in the very first class,” which would earn him similar respect as an American historian.102

Back of this immediate ambition swirled a mass of past influences, with little in common except their general geographic orientation. Among them were his years in the West, living with the sons and grandsons of pioneers; his belief, inherited from Thomas Hart Benton, that America’s Manifest Destiny was to sweep Westward at the expense of weaker nations; his fascination with the racial variety of the West, and its forging of a characteristic frontier “type,” never seen in the Old World; his wide readings in Western history; his efforts, through the Boone & Crockett Club, to save Western wildlife and promote Western exploration—all these combined into one mighty concept which (the more he pondered it) he saw he might handle more authoritatively than anyone else. It was nothing less than the history of the spread of the United States across the American continent, from the day Daniel Boone first crossed the Alleghenies in 1774 to the day Davy Crockett died at the Alamo in 1836.103 He decided to call this grand work The Winning of the West.

His first act was to dedicate the book to the ailing Francis Parkman.104 Like most well-read men of his class, Roosevelt had been brought up on that writer’s majestic, seven-volume History of France and England in North America. Parkman was a scholar who combined faultless research with the narrative powers of a novelist. With that other sickly, half-blind recluse, William H. Prescott, he wrote sweeping sagas full of color and movement, in which men of overwhelming force bent nations to their will. Roosevelt set out to follow this example. Not for him the maunderings of the “institutional” historians, with their obsessive analyses of treaties and committee reports. He wanted his readers to smell the bitter smoke of campfires, see the sunset reddening the Mississippi, hear the tomahawk thud into bone. While reveling in such detail (which he would meticulously annotate, lest any pedant accuse him of fictionalizing), he would strive for Parkman’s epic vision, the ability to show vast international forces at work, whole empires contending for a continent.105

![]()

BY MID-MARCH he had a contract from Putnam’s—committing him rather ambitiously to deliver his first two volumes in the spring of 1889106—and he plunged at once into the somewhat rodent-like life of a professional historian. He burrowed through piles of ancient letters, diaries, and newspapers in Tennessee, and unearthed many long-forgotten documents in Kentucky, including six volumes of Spanish government dispatches, and some misspelled but priceless pioneer autobiographies; he inquisitively searched some two or three hundred folios of Revolutionary manuscripts in Washington, and ferreted out thousands of letters by Jefferson, Madison, and Monroe, untouched by previous scholars; he devoured the published papers of the Federal, Virginia, and Georgia governments in New York, and pestered private collectors as far away as Wisconsin and California to send him their papers.107 By the end of April he had amassed the bulk of his source material, and began the actual writing of The Winning of the West on 1 May, at Sagamore Hill.108

As always, he found it difficult to marshal his superabundant thoughts on paper. A perusal of the manuscript of Volume One shows what agonies its magnificent opening chapter, “The Spread of the English-Speaking Peoples,” cost him. A veritable thicket of verbal debris—interlineations, erasures, blots, and balloons—clogs every page: only the clearest prose is allowed to filter through.109

![]()

DURING ALL THE SPRING and summer of 1888 Roosevelt complained about the slowness of his progress on The Winning of the West: “it seems impossible to write more than a page or two a day.”110 As if from another land, another century, he heard distant shouts that General Benjamin Harrison of Indiana had been nominated by the Republicans for the Presidency—James G. Blaine having withdrawn on the grounds that a once-defeated candidate might, after all, be a burden to the party. Other shouts, even more distant, told him that Grover Cleveland had been renominated by the Democrats. But he paid little attention, and hunched closer over his desk. “After all,” he told a friend, “I’m a literary feller, not a politician these days.”111

To maintain the Sagamore household and bolster Edith’s constant sense of financial insecurity, Roosevelt had to earn at least $4,000 in fees and royalties that year.112 This meant a considerable amount of hackwork over and above his labors on The Winning of the West. Scarcely a month, accordingly, passed without at least one book or article from his pen. Although some of these had been written before—or published in a different form—merely to edit and proofread them made heavy inroads upon his time.

A survey of their various titles justifies his growing reputation as a Renaissance man. In February the North American printed his “Remarks on Copyright and Balloting,” while Century put out the first of six splendid essays on ranch life in the West. This series, which included his long-delayed account of the capture of Redhead Finnegan, continued through March, April, May (a month which also saw the publication of his Gouverneur Morris), and June. The essays attracted the admiring attention of Walt Whitman, who wrote, “There is something alluring in the subject and the way it is handled: Roosevelt seems to have realized its character—its shape and size—to have honestly imbibed some of the spirit of that wild Western life.”113

Roosevelt was silent in July and August, but came back resoundingly in September with “A Reply to Some Recent Criticism of America” in Murray’s Magazine. The piece was a brilliant and erudite attack upon Matthew Arnold and Lord Wolseley (“that flatulent conqueror of half-armed savages”) and became the talk of Washington and London. In October, Putnam’s put out his Essays in Practical Politics, being a reissue, in book form, of two long polemics on legislative and municipal corruption, “Phases of State Legislation” (1884) and “Machine Politics in New York City” (1886). Finally, in December, his six Century articles were revised and republished as Ranch Life and the Hunting Trail, in a deluxe gift edition, illustrated by Frederic Remington. It was greeted with enthusiastic reviews.114

![]()

ROOSEVELT’S NONLITERARY ACTIVITIES through 1888 can be briefly summarized. The family man played host to Cecil Spring Rice and “delicious Cabotty,” piggybacked little Alice downstairs to breakfast every day, and noted approvingly that young Ted “plays more vigorously than any one I ever saw.” He worried sporadically about his brother Elliott, whose health was beginning to deteriorate from too much hard drinking and hard riding with the “fast” Meadowbrook set.115

The end of August found Roosevelt the hunter in Idaho’s Kootenai country. He spent most of September in the mountains, sleeping above the snow-line without a jacket and feasting lustily on bear-meat. Returning East via Medora, Roosevelt the rancher was able to make some respectable sales of his remaining cattle. But Roosevelt the author was still so hard pressed for money that he rashly accepted an invitation to write a history of New York City for a British publisher. He begged for “a little lee-way … to finish up some matters which I must get through first.”116

This referred to The Winning of the West. Its text was beginning to drag alarmingly: with six months to go on his contract, he had written only half of Volume One. Vowing to “fall to … with redoubled energy,” he returned to Sagamore Hill on 5 October117—but Roosevelt the politician would not let him sit down at his desk.

The presidential campaign was well under way, and with Cleveland crippled by the tariff controversy, there seemed to be a real chance of a Republican victory. Duty required that he make at least a token appearance for Benjamin Harrison. Actually Roosevelt was more than willing, for he considered the little general an excellent candidate.118 Despite a total lack of charisma, Harrison was a magnificent orator, capable of enthralling thousands—as long as he did not shake any hands afterward. It was said that every voter who touched his icy flesh walked away a Democrat.119 Party strategy, therefore, called for maximum public exposure, minimum personal contact, and support appearances by fiery young Republicans like Roosevelt, who could be guaranteed to thaw anybody Harrison had frozen.

On 7 October, after only one day at home, Roosevelt answered the call. Jumping back onto the Chicago Limited, he set off on a speaking tour of Illinois, Michigan, and Minnesota. The sight of crowds and bunting worked its usual magic on him, and he canvassed with great zest. His performance was good enough to establish him, within a week, as one of the campaign’s most effective speakers. “I can’t help thinking,” he wrote Lodge, “that this time we have our foes on the hip.”120

On 27 October, Theodore Roosevelt turned thirty. Nine days later he heard that his party had won not only the Presidency but the Senate and House of Representatives as well. “I am as happy as a king,” he told Cecil Spring Rice, “—to use a Republican simile.”121

![]()

AT LAST, as winter settled down on Sagamore Hill, a measure of tranquillity returned to Roosevelt’s life. The sight of snow tumbling past his study window, and the sound of logs crackling in the grate, combined to produce that sense of calm seclusion a writer most prizes—when the pen seems to move across the paper almost of its own accord, and the words flow steadily down the nib, drying into whorls and curlicues that please the eye; when sentences have just the right rhythmic cadence, paragraphs fall naturally into place, and the pages pile up satisfyingly … Roosevelt’s characteristic interlineations and scratchings-out grew fewer and fewer as the pace of his narrative increased, and inspiration grew.122

He worked steadily all though December, finishing Volume One before Christmas.123 Early in the New Year he moved his family to 689 Madison Avenue. (Bamie, who was traveling in Europe, had placed her house at Edith’s disposal.)124 Seeking refuge from the children, Roosevelt set up a desk at Putnam’s, on West Twenty-third Street. For some reason the publishers were in a hurry to get the book out by the middle of June. Chapters of Volume Two were sent upstairs to the composing room as fast as Roosevelt could write them. Meanwhile Volume One was printed and bound on the topmost floors. Later, stacks of both volumes would be cranked downstairs for sale in the retail department at street level—permitting George Haven Putnam to boast that The Winning of the Westhad been in large part written, produced, and marketed under one roof.125

Roosevelt scrawled his last line of text on 1 April 1889, and spent the next couple of weeks blearily checking the galleys. With a touch of sadness he wondered “if I have or have not properly expressed all the ideas that seethed vaguely in my soul as I wrote it.”126But he had little leisure to indulge in self-doubts, for on 27 April Cabot Lodge came up from Washington127 with a message from the White House.

![]()

ONLY A FEW DAYS BEFORE, Roosevelt had written, “I do hope the President will appoint good Civil Service Commissioners.”128 Lodge fully understood the plaintive tone of that remark. Since the beginning of the year he had been trying to get his friend a place in the incoming Administration. Roosevelt had affected nonchalance at first, yet while still engaged on the final chapters of The Winning of the West, confessed, “I would like above all things to go into politics.”129 Lodge had tried to persuade Harrison’s new Secretary of State—who was none other than James G. Blaine—to appoint Roosevelt as Assistant Secretary, but the Plumed Knight gracefully demurred. In words that proved prophetic, he wrote:

My real trouble in regard to Mr. Roosevelt is that I fear he lacks the repose and patient endurance required in an Assistant Secretary. Mr. Roosevelt is amazingly quick in apprehension. Is there not danger that he might be too quick in execution? I do somehow fear that my sleep at Augusta or Bar Harbor would not be quite so easy and refreshing if so brilliant and aggressive a man had hold of the helm. Matters are constantly occurring which require the most thoughtful concentration and the most stubborn inaction. Do you think that Mr. T.R.’s temperament would give guaranty of that course?130

Lodge had reported only the polite parts of this rejection. “I hope you will tell Blaine how much I appreciate his kind expressions,” Roosevelt replied.131

Lodge had then begun to negotiate directly with the President, urging him to appoint Roosevelt to some federal position, no matter how minor, in recognition of his help during the campaign. Several influential Republicans advised the same. Harrison was “by no means eager.”132 Perhaps he remembered the screeching, strawhatted young delegate at Chicago in 1884, and winced at the idea of having him within earshot of the White House. Eventually he thought of a dusty sinecure that paid little, and promised less in terms of real political power. Ambitious men invariably turned it down; if Roosevelt was crazy enough to want it, he might be crazy enough to make something of it.

Lodge hurried to New York, and, amid the din of the U.S. Government Centennial celebrations,133 told Roosevelt that Harrison was willing to appoint him Civil Service Commissioner, at a salary of $3,500 per annum. He doubted, however, that his friend would want the post. Such a pittance could only plunge him deeper into financial difficulties; bureaucratic entanglements would interfere with his upcoming book contracts; besides, the work was bound to make him unpopular, for everybody in Washington was heartily sick of the subject of Civil Service Reform.

Roosevelt accepted at once.

![]()

A COUPLE OF DAYS LATER the Centennial came to an end with the biggest banquet in American history, held at the Metropolitan Opera House. About eleven o’clock, after the speeches were over, and $16,000 worth of wine had been drunk, the guests filed out into the crisp spring night. Most were tired and satiated, but one young man seemed anxious to dawdle and talk. His high, eager voice, as he stood on the sidewalk with a group of friends and pointed at the sky, sounded “quite charming” to a passerby, although he occasionally squeaked into falsetto. “It was young Roosevelt,” reported the observer. “He was introducing some fellows to the stars.”134