On the deck stands Olaf the King,

Around him whistle and sing

The spears that the foemen fling,

And the stones that they hurl with their hands.

![]()

WASHINGTON, D.C., IN THE SPRING of 1889 was, for those who could afford to live there, one of the most delightful places in the world.1 Seen from various carefully-selected angles, it was a beautiful city, with its broad, black, spotless streets, its marble buildings and sixty-five thousand trees, its vistas of “the silvery Potomac” by day and the illuminated Capitol by night. A visiting Englishman remarked on its air “of comfort, of leisure, of space to spare, of stateliness … it looks the sort of place where nobody has to work for his living, or, at any rate, not hard.”2

This was true above a certain bureaucratic level. Senior clerks and Cabinet officers alike breakfasted at eight or nine, lunched with all deliberate speed, and laid down their pens at four.3 They then had several hours of daylight left for strolling, shopping, drinking, or philandering (Washington was reputed to be “the wickedest city in the nation”)—hours which lengthened steadily as the warm weather approached, and Government prepared to shut down for the summer.

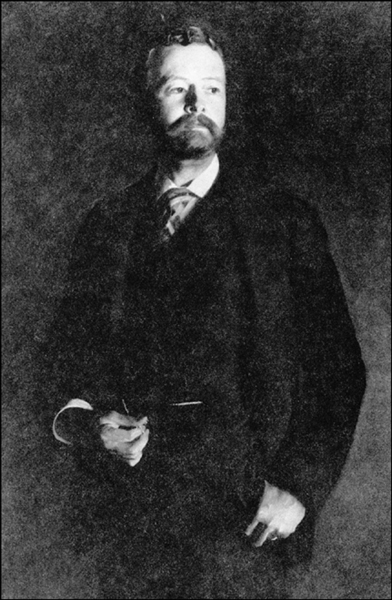

“Rich and talented people crowded Adams’s salon.”

Congressman Henry Cabot Lodge, by John Singer Sargent, 1890. (Illustration 16.1)

While peaceful, the capital was by no means provincial. Indeed, the decade just ending had seen its transformation from rather shabby respectability to the heights of social splendor. People who spent their summers at Newport and Saratoga were spending their winters in Washington.4 Some had been drawn by the magnetism of Mrs. Cleveland, now regrettably departed (although imitations of her famous smile lingered on a thousand homelier faces, reminding one correspondent of so many cats chewing wax).5 Most of Washington’s fashionable newcomers, however, were drawn by the desire to be at the power center of an increasingly powerful country. Power, not breeding, was the basis of protocol in this democratic town: there was something wickedly exciting about it. Knickerbockers and Brahmins vied for the company of Western Senators at dinner, laughing at their filthy stories and tolerating their squirts of tobacco-juice; debutantes and newsboys swayed side by side in the horsecars with Supreme Court Justices; the President of the United States could often be seen, a small, bearded, buttoned-up figure, sipping soda in a corner drugstore.6

Another significant difference between Washington and most major American cities was the apparent contentment of its working class—particularly now the party of Lincoln was back in control. A thriving demimonde offered blacks opportunities for advancement in such government-related industries as prostitution, vote-selling, and land speculation. Here, indeed, were to be found the nation’s wealthiest black entrepreneurs, and “colored girls more luscious than any women ever painted by Peter Paul Rubens.” They could be seen on a Saturday afternoon strolling in silks and sealskins on the White House lawn, to promenade music by Professor Sousa’s Marine Band.7

Apart from the several thousands of shanty-dwellers, whose slums could be smelled, if not seen, in the vacant lots behind the great federal buildings, Washington society was prosperous, and graded more by occupation than color. Its unique feature was an ephemeral upper class which turned over every four years, according to the vagaries of politics. Hardly any member of this class, be he diplomat, Congressman, or Civil Service Commissioner, expected to settle permanently in the capital; sooner or later his government would recall him, or his campaign for reelection fail, or a whim of the President leave him jobless overnight.

Servicing the upper class was a middle-to-lower class of realtors, caterers, couturiers, landladies, and servants—all determined to profit by the constant comings and goings of their clients. After every Congressional election, prices rose; after every change of Administration, they soared. But federal pay scales remained fixed at levels set in the 1870s. By 1889 the city had grown so expensive that anybody accepting a fairly senior government job had to have independent means to survive.8 On the Sunday before Roosevelt’s arrival, eight-room houses in the obligatory Northwest sector were being advertised for sale at around $6,500, almost twice a Commissioner’s salary. But this was nothing: a thirteen-room house on Pennsylvania Avenue near Nineteenth was $12,500; something more the size of Sagamore Hill, albeit with a much smaller garden, was available on Vermont Avenue for $125,000.9 Rents were proportionately exorbitant; the pokiest little furnished house would cost him $2,400 a year.10 Allowing a conservative $1,000 for food, $300 for servants, and $200 for fuel, he could spend every cent of his salary without so much as buying a new suit.11 On top of that there was Sagamore Hill to maintain, and Edith was pregnant again.

The baby was not due for another five months, but it served as an excuse to keep his family at Oyster Bay at least through November. Meanwhile he could lead a cheap bachelor life in Washington—rent-free, as the vacationing Lodges had placed their house on Connecticut Avenue at his disposal.12

So when Roosevelt arrived in town on the morning of Monday, 13 May 1889, he was alone, just like thousands of other hopeful newcomers in the early days of the Harrison Administration. Unlike them, however, he had a desk waiting for him, and a commission, signed by the President of the United States, lying upon it.13

![]()

IT WAS NOT YET ten o’clock, but the sun was bright and strong. A cool breeze blowing off the Potomac tempered the seventy-degree heat. All Washington sparkled, thanks to torrential rainstorms over the weekend. Fallen locust-blossoms carpeted the sidewalks, rotting sweetly as pedestrians sauntered to and fro. Straw hats and silk bonnets were out in force: summer, evidently, was considered to be a fait accompli in the nation’s capital, regardless of what the calendar said.14

Roosevelt found the Civil Service Commission impressively located in the west wing of City Hall, at the south end of Judiciary Square. Tall Ionic columns rose above a flight of seventeen stone steps, which he could not resist taking at a run.15 By the time he had crossed the portico and burst into the office beyond, his adrenaline was already flowing.

“I am the new Civil Service Commissioner, Theodore Roosevelt of New York,” he announced to the first clerk he saw. “Have you a telephone? Call up the Ebbit House. I have an engagement with Archbishop Ireland. Say that I will be there at ten o’clock.”

His clear voice sounded “peculiarly pleasant” as it broke the bureaucratic stillness. Yet it had an incisive edge to it that made the clerk jump to his feet.16

Within minutes Roosevelt had taken the oath, and moved into the largest and sunniest of the three Commissioners’ offices.17 Although his gray-haired colleagues, Charles Lyman (Republican) and ex-Governor Hugh S. Thompson of South Carolina (Democrat), were nominally senior to him, he seems to have been accepted, de ipse, as leader from the start.18 Lyman’s subsequent election as president of the Commission in no way affected this arrangement. Roosevelt liked both of them, as he did everyone at first, then lost patience with them, as he did with most people sooner or later. Lyman turned out to be “the most intolerably slow of all men who ever adored red tape,”19 while Thompson was “a nice old boy,” but not much else.20 However Roosevelt managed to keep these opinions private, and the professional harmony among the three was such that some members of Harrison’s Cabinet began to worry about it. The last thing they needed, as they began to hand out appointments for services rendered, was an active Civil Service Commission.

![]()

IT IS DIFFICULT for Americans living in the first quarter of the twenty-first century to understand the emotions which Civil Service Reform aroused in the last quarter of the nineteenth. The movement’s literature has about it all the faded ludicrousness of Moral Rearmament. How could intellectuals, politicians, socialites, churchmen, and editors campaign so fervently on behalf of customs clerks, Indian school superintendents, and Fourth-Class postmasters? How could they wax so lyrical about quotas, certifications, political assessments, and lists of eligibles? How, indeed, could one reformer entitle his memoirs The Romance of the Merit System?21

The fact remains that thousands, even millions, lined up behind the banner, and they were as evangelical (and as strenuously resisted) as any crusaders in history. To them Civil Service Reform was “a dream at first, and then a passionate cause which the ethical would not let sleep.”22 Men and women of the highest quality devoted whole careers to it, and died triumphant in the knowledge that, due to their personal efforts, the classified departmental service had been extended by so many dozen places in Buffalo, or that algebraic equations had been deleted from the examination papers of cattle inspectors in Arizona.

For all its dated aspects, Civil Service Reform was an honorable cause, and of real social consequence. It sought to restore to government three fundamental principles of American democracy: first, that opportunity be made equal to all citizens; second, that the meritorious only be appointed; third, that no public servants should suffer for their political beliefs. The movement’s power base—admittedly a rickety one—was the Pendleton Act of 1883, which guaranteed that at least a quarter of all federal jobs were available to the best qualified applicant, irrespective of party, and that those jobs would remain secure, irrespective of changes in Administration.23

Few converts believed in the above principles more sincerely than Theodore Roosevelt. He had become fascinated with Civil Service Reform shortly after leaving college, and, as an Assemblyman, had helped bring about the first state Civil Service law in the country, closely based on the Pendleton Act. He had joined Civil Service Reform clubs, subscribed to Civil Service Reform journals, and preached the doctrine of Civil Service Reform to numerous audiences. His acceptance of the Commissionership, therefore, seemed natural and inevitable to his colleagues in the movement, although many believed he had sacrificed his political future by doing so.24 There would be times, during the next six years, when he was tempted to agree with them.

![]()

ON THE MORNING after taking his oath of office, Roosevelt went to pay his respects to the President. He was prepared not to like him, for the little general was famously repellent in manner. With his fat cheeks, weak stoop, and small, suspicious eyes, Benjamin Harrison reminded one visitor of “a pig blinking in a cold wind.”25 It was hard to believe that this sour, silent Hoosier possessed the finest legal mind in the history of the White House, or that he was capable of reducing large audiences to tears with the beauty of his oratory.26 It was even harder to believe the old friend who assured the press, “When he’s on a fishing trip, Ben takes his drink of whiskey in the morning, just like anyone else … spits on his worm for luck, and cusses when the fish get away.”27

But during Roosevelt’s visit, Harrison made a less dyspeptic impression than usual. He had just returned from a cruise down the Potomac, and looked ruddy and clear-eyed.28 The President must have given his new Commissioner assurances of support, for Roosevelt was ebullient when he burst out of the Executive Office. He nearly collided with the only other member of the Administration whose personal impetus matched his own: big, bustling, baby-faced John Wanamaker, the Philadelphia retail millionaire and new Postmaster General. Roosevelt recognized him, and the two men exchanged hearty greetings.

Other Cabinet officers were arriving to meet with the President, and Wanamaker introduced Roosevelt all around. There were jokes about the young man’s presumed authority over federal jobs. “You haven’t any power over my place, anyway,” said the Secretary of the Navy, in mock relief. “If I had to pass a civil-service examination for mine,” Roosevelt answered, “I would never have been appointed.” “I’m glad you realize that,” growled the Secretary of Agriculture.29

Laughing loudly, the Cabinet filed into Harrison’s office, leaving Roosevelt alone with his thoughts. He was aware (as was an unobtrusive reporter) that much cold hostility lurked behind the warm handshakes he had received. John Wanamaker, undoubtedly, would be his major opponent in the fight to enforce Civil Service rules. Wanamaker was a man of charm, pious habits, and magnificent administrative ability; he was also a Republican of the old school, and a staunch defender of the spoils system.30 The President had rewarded him for his lavish campaign contributions, and Wanamaker believed that all loyal Republicans, great or humble, who had given time and money to the party were entitled to similar recognition. As such he had emerged as the leading “spoilsman” in the Cabinet and a benign foe of all “Snivel Service Reformers.”

Roosevelt was already too late to prevent the wholesale looting of Postal Service jobs which had taken place in the first six weeks of the new Republican Administration. (Some said that Harrison had purposely delayed his appointment to allow the Postmaster General a free hand.) The scramble for office was, according to one horrified reformer, “universal and almost unbelievable.”31 Wanamaker’s assistant, James S. Clarkson, had been replacing Democratic Fourth-Class postmasters at the rate of one every five minutes. Thousands of newspaper editors who had supported Harrison were put on the government payroll. Even ex-jailbirds whose services had been of the “dirty tricks” variety were rewarded with minor positions. Other Cabinet officers, caught up in the fever, also dispensed largesse. Attorney General William H. Miller was reported to have announced that any aspirant to a federal job must be “first a good man, second a good Republican.”32

An extension of the Civil Service Law on 1 May—ordered by Cleveland and executed by Harrison—had slowed the pace of looting, but only in the classified quarter of the service. Over the other three-quarters, comprising some 112,000 jobs, Roosevelt had no power whatsoever. His Commission’s mandate extended to a mere 28,000 subordinate positions in the departmental, customs, postal, railway mail, and Indian services.33 Its powers, moreover, were slight. A Commissioner might personally investigate cases of examination fraud in Kansas, or political blackmail in Maine (providing he could find enough money in the budget to get there), but even if the evidence uncovered was flagrant, he could do little more than recommend prosecution to the Cabinet officer responsible. And if that officer were a Wanamaker or a Miller, he might as well save his breath.

Such, at least, had been the attitude of Roosevelt’s eight predecessors, who had all been sedentary bureaucrats, content to supervise the marking of countless examination papers. The Civil Service Commission was a pleasant place to drowse, with its large, quiet offices and views of lawns and trees; there was an excellent fried-oyster restaurant across Louisiana Avenue; and if one did not offend any political bigwigs, one was invited to some decent receptions.34

Roosevelt would have none of this laissez-faire policy. From the moment he returned from the White House on 14 May, he became a blur of high-speed activity. He mastered the Commission’s complex operations within days, throwing off a wealth of new ideas, devouring documents at the rate of a page a glance, dictating hundreds of letters with such hissing emphasis that the stenographer did not need to ask for punctuation marks. Staff and visitors alike were dazed by his energy, exuberance, and ruthless outmaneuvering. “He is a wonderful man,” said one caller. “When I went to see him, he got up, shook hands with me, and said, ‘So glad to see you. Delighted. Good day, sir, good day.’ Then he ushered me to the door. I wonder what I wanted to see him about.”35

The new Commissioner was not interested in audiences of one. Experience had taught him that he had in abundance the power of mass publicity,36 that it could be as effective, if not more so, than regular political clout. He intended so to dramatize the good gray cause of Civil Service Reform that the electorate would be forced to take notice of it—and if of himself as well, why, so much the better.

As a preliminary attention-getting exercise, Roosevelt went on 20 May to New York, where the press knew him, to check some recent examinations in the Custom House. He found that various questions had been leaked to favored candidates, at $50 a head, and issued a fiery report accusing the local examinations board of “great laxity and negligence,” “positive fraud,” and mismanagement for “personal, political, or pecuniary” reasons. The report called for the dismissal of three officials and the criminal prosecution of at least one of them. “This report astonished the spoilsmen,” wrote one prominent reformer. “It was the first emphatic notice that the Civil Service Act was a real law and was to be enforced.”37

Roosevelt returned to the capital and pondered his next move. The Eastern press was watching him now; it was time to get Western newspapers to do the same. On 17 June, therefore, he set off on an investigatory tour of some Great Lakes post offices with Commissioners Lyman and Thompson. Their first scheduled stop, he innocently announced, would be Indianapolis, where there were rumors of incompetence and partisanship involving the local postmaster, William Wallace. It did not take reporters long to realize that Wallace was the close personal friend, and Indianapolis the home city, of the President of the United States.38

![]()

LUCIUS BURRIE SWIFT, Indianapolis editor of the Civil Service Chronicle, was walking downtown on the morning of 18 June when “I saw Theodore Roosevelt coming towards me, his smile of recognition visible half a block away.”39 The two men knew each other well: it had been Swift who originally asked the Civil Service Commission to investigate Postmaster Wallace. While Roosevelt completed his postbreakfast “constitutional,” Swift went over the main facts of the case again. Three venal ex-employees of the Post Office, fired some years before by Wallace’s Democratic predecessor, had been given their jobs back simply because they were Republicans. One was rumored to be the operator of an illegal gambling den—clearly not the sort of civil servant the Commission should favor.40

The investigation, held that afternoon in the Indianapolis Post Office, confirmed the truth of Swift’s allegations. “These men must be removed today,” Roosevelt exclaimed. Wallace strenuously objected, but Commissioners Lyman and Thompson backed their young colleague up. The postmaster had no choice but to capitulate. He agreed to dismiss the offending employees, and promised that in future he would scrupulously observe the Civil Service law.41

Later, when Roosevelt was celebrating at Swift’s house, Wallace visited Lyman and Thompson at their hotel. He asked if he might produce “new evidence” exonerating himself before they wrote their final report. The Commissioners agreed, much to Roosevelt’s irritation, for he considered Wallace “a well-meaning, weak old fellow,” and suspected that he was merely stalling.42 The evidence, in any case, proved to be worthless. Postmaster Wallace’s humiliation was duly headlined in the Indianapolis and Washington newspapers. “We stirred things up well,” Roosevelt boasted to Lodge. As for President Harrison, “we have administered a galvanic shock that will reinforce his virtue for the future.”43 Whether Harrison would relish this shock remained to be seen.

![]()

TWO DAYS LATER the Commissioners were in Milwaukee, where the evidence of Post Office corruption was so overwhelming as to make Indianapolis seem trivial. Roosevelt got off the train convinced, on the basis of advance information, that Postmaster George H. Paul was “guilty beyond all reasonable doubt,”44 and as soon as he laid eyes on the man his suspicions were confirmed. “About as thorough-paced a scoundrel as I ever saw,” Roosevelt declared. “An oily-Gammon, churchgoing specimen.”45

The principal testimony against Paul was supplied that afternoon by Hamilton Shidy, a Post Office superintendent and secretary of the Milwaukee Civil Service Board. Before taking the stand, Shidy said he was a poor man, entirely dependent on his job for support. He asked for a promise of protection, which Roosevelt promptly—and rashly—gave.46 Shidy then went on to describe how Paul had for years “appointed whomsoever he chose” to lucrative Post Office positions. After every such appointment, Shidy was told to “torture” the lists of eligibles so as to make it seem that Paul’s men had won their jobs in open examination. On one occasion the postmaster had actually stood looking over his shoulder while Shidy re-marked an examination paper downward. To substantiate his charges, Shidy handed over a sheaf of illegal orders in Paul’s own handwriting.47

Next morning Roosevelt confronted the fat little postmaster with Shidy’s evidence. “Mr. Paul, these are very grave charges, and we should like to hear any explanation you have to make.” As he handed them over, item by item, Paul (examining each one disdainfully through his glasses, at arm’s length) protested he did not know, or could not remember. “Shidy was the man who was doing all that—you will have to see Shidy.” “We are not talking of Shidy,” said Roosevelt, “but of what you did. Why did you make this appointment? Why did you make that appointment?” “You must ask Shidy,” was the nonchalant reply.48

The Commissioners did not bother to question Paul at length, for they had more than enough hard evidence to prove his guilt. It would give President Harrison no alternative but to fire him upon their recommendation. A dramatic, high-level dismissal, followed if possible by criminal prosecution, was just the sort of publicity coup Roosevelt wanted in the Midwest. But then Paul blandly announced that his letter of appointment, signed by President Cleveland four years before, had expired. “My term is out. I am simply waiting for my successor to qualify.”49

At this there was nothing for the Commissioners to do but leave town on the next train. On the way back to Washington they drafted an impotent report. Not until after they had returned, and sent it in, did they discover that Postmaster Paul was a liar. His term of office still had several months to run. A supplemental report was accordingly rushed to the White House—and to the Associated Press.50 Although the document bore three signatures, its language was unmistakably Rooseveltian.

For Mr. Paul to plead innocent is equivalent to his pleading imbecility … Mr. Paul alone benefitted from the crookedness of the certifications, for he alone had the appointing power … He has grossly and habitually violated the law, and has done it in a peculiarly revolting and underhanded manner. His conduct merits the severest punishment … and we recommend his immediate removal.51

![]()

“I HAVE MADE this Commission a living force,” Roosevelt rejoiced on 23 June.52 He was in tremendous spirits, as always after battling the ungodly. There was, as yet, no official reaction to his “slam among the post offices.” Some rumblings of displeasure over the Indianapolis affair had been heard down Pennsylvania Avenue, but he doubted the President was really upset. “It is to Harrison’s credit, all we are doing in enforcing the law. I am part of the Administration; if I do good work it redounds to the credit of the Administration.”53

This cheerful optimism was not shared by his Republican friends, nor by Postmaster General Wanamaker, who was reported “enraged” by the press coverage enjoyed by Roosevelt on tour.54 To investigate discreetly was one thing; to cross-examine senior Post Office executives in public, and express his contempt for them afterward, at dictating speed, was another. Even the loyal Cabot Lodge warned him to keep out of the headlines until he was more settled in his job. “I cry peccavi,” Roosevelt replied, “and will assume a statesmanlike reserve of manner whenever reporters come near me.”55

Reserved or not, he could not quell his bubbling good humor. Things were going particularly well for that other Roosevelt, the man of letters. Volumes One and Two of The Winning of the West had been published during his absence, to panegyrical newspaper reviews. “No book published for many years,” remarked the Tribune, “has shown a closer grasp of its subject, a more thorough fitness in the writer, or more honest and careful methods of treatment. Nor must the literary ability and skill displayed throughout be overlooked. Many episodes … are written with remarkable dramatic and narrative power. The Winning of the West is, in short, an admirable and deeply interesting book, and will take its place with the most valuable and indispensable works in the library of American history.”56

He would have to wait for several months for more learned opinions, but in the meantime he could cherish a complimentary letter from the great Parkman himself. “I am much pleased you like the book,” Roosevelt wrote in acknowledgment. “I have always intended to devote myself to essentially American work; and literature must be my mistress perforce, for although I enjoy politics I appreciate perfectly the exceedingly short nature of my tenure.”57

If John Wanamaker had had his way, Roosevelt’s tenure would have been the shortest in the history of the Civil Service Commission. The Postmaster General was reluctant—and the President even more so—to fire Postmaster Paul for abuse of the merit system, even though that individual was a Democratic holdover. The precedent thus established would mean that Roosevelt, in future, could demand the dismissal of Republican postmasters for the same reason. In any case, Wanamaker did not like being told what to do in his own department by a junior member of the Administration. His chance for revenge came at the beginning of July, when Roosevelt came to him in great agitation to report that Paul had dismissed Hamilton Shidy for treachery and insubordination. Wanamaker curtly refused to intervene.58

This placed Roosevelt in a highly embarrassing position. As Shidy’s promised protector, he was in honor bound to find him another federal job. But as Civil Service Commissioner, he was in honor bound to enforce the law. How could he give patronage to a confessed falsifier of government records? How could he, in all conscience, not do so? Wanamaker, of course, understood his dilemma, and knew that the best way out was for him to resign. “That hypocritical haberdasher!” Roosevelt exploded. “He is an ill-constitutioned creature, oily, with bristles sticking up through the oil.”59

On 10 July a telegram summoned the three Commissioners to the White House. Roosevelt may have wondered if he was about to go the same way as Shidy, but he was pleasantly surprised by Harrison’s attitude. “The old boy is with us,” he told Lodge. “The Indianapolis business gave him an awful wrench, but he has swallowed the medicine, and in his talk with us today did not express the least dissatisfaction with any of our deeds or utterances.”60

Fortified by these signs of Presidential approval, Roosevelt was able to persuade the Superintendent of the Census to find a place for Hamilton Shidy in his bureau.61 Wanamaker philosophically agreed to the transfer, and Roosevelt, feeling that he had settled a gentlemanly debt, doubtless thought no more about it.

![]()

DAILY THE SUN GREW hotter, softening the asphalt in the streets and glaring on marble and whitewash. Slum dwellers began to sweep out their shanties, filling the air with acrid dust. Pleasure-boats on the Potomac hoarsely encouraged office-workers to play hooky. Every evening millions of mosquitoes left the marshes south of the White House and fanned out in search of human blood. As August approached, the city’s population decreased by almost one-third, and the tempo of government business slowed almost to a standstill.62

Roosevelt was unable to prevent the Civil Service Commission from lapsing into what he called “innocuous desuetude.” The evidence is he did not try very hard, for his own duties were light. “It is pretty dreary to sizzle here, day after day, doing routine work that the good Lyman is quite competent to attend to himself.” He tried to begin his history of New York, but found he could not write. He spent $1.50 on a new volume of Swinburne, read a few voluptuous lines, then threw it away in disgust. “My life,” he mourned, “seems to grow more and more sedentary, and I am rapidly sinking into fat and lazy middle age.”63

Clearly he was in need of his annual vacation in the West. If President Harrison would only hurry up and announce the dismissal of Postmaster Paul, he could take the next train out of town “with a light heart and a clear conscience.”64 But the White House preserved an enigmatic silence. Then, as Roosevelt chafed at his desk, a thunderbolt struck him.

![]()

FRANK HATTON, editor of the Washington Post, was an ex–Postmaster General and an enemy of Civil Service Reform.65 He was also a shrewd promoter who knew the value of a running fight in boosting circulation. On 28 July he suddenly decided to launch an attack on Roosevelt. His lead editorial derided the Commissioner as “this young ‘banged’ (and still to be banged more) disciple of counterfeit reform.” He accused Roosevelt of personally condoning many violations of the Civil Service Law, and of misappropriating—or misspending—large sums of federal money. Without being specific as to any recent crimes, Hatton said that “the Fifth Avenue sport” had bribed his way into the New York mayoralty campaign, and made “disreputable” deals with machine politicians.66

Nostrils dilated, Roosevelt rushed to the podium to deny these “falsehoods.” He was tempted, he said, to use “a still stronger and shorter word.”67 Hatton’s reply, published the following day, shrewdly played upon that temptation.

THE POST regrets that this spangled and glittering reformer, if he is bound to get mad, should not do so in more classic style. You are not a ranchman now, Mr. Theodore Roosevelt … Banish your cowboy manners until the end of your trip, which the evening papers announce you are to take in a few days. And, by the way … have you made the proper application for a leave of absence, or have you ordered yourself West, that you may have the Government pay your ‘legitimate’ travelling expenses?

THE POST had an idea that it would bring to the raw the surface of the callow Roosevelt … For you to say that the [Civil Service] law has not been violated is to advertise yourself as a classical ignoramus, and the sooner you hie yourself West to your reservation, where you can rest your overworked brain, the more considerate you will be to yourself.

Now, Mr. Commissioner Roosevelt, you can mount your broncho and be off. Personally, THE POST wishes you well. It enjoys you.

On the same day this editorial appeared, Roosevelt bumped into President Harrison, who had doubtless read it with amusement over breakfast. Psychologically the moment was unsuitable for a speech in Western dialect, but Roosevelt, hoping he could persuade Harrison not to take Wanamaker’s side in the Paul case, made one anyhow. He quoted the prayer of a backwoodsman battling a grizzly: “Oh Lord, help me kill that b’ar, and if you don’t help me, oh Lord, don’t help the b’ar.”68 But Harrison reserved the Almighty’s right of no reply, and walked on, leaving Roosevelt no wiser than before.

July ended, and August began, with the offending postmaster still in office. Roosevelt vented his frustration in an interview with the New York Sun, accusing “a certain Cabinet officer” of working against the cause of Civil Service Reform.69 Hatton reprinted his words in the Post, and commented that if this charge by “the High, Joint, Silver-Plated Reform Commissioner” was true, it reflected upon the entire Cabinet, and upon President Harrison himself. “It is all very well for this powdered and perfumed dude to be interviewed every day, but what the public would like to know is whom he meant, what Cabinet officer he referred to, when he said that the Civil Service law was being evaded … This is a very serious charge for you, Mr. Commissioner Roosevelt, to make against the Administration.”70

Hatton sent a squad of reporters to ask all the Cabinet members whom they thought Roosevelt was accusing. “I would have to be a mind-reader to guess,” said John Wanamaker smoothly.71

On 5 August Roosevelt was summoned to the White House and told that God had decided in favor of the grizzly. Rather than dismiss Postmaster Paul outright, Harrison had merely accepted a letter of resignation. “It was a golden chance to take a good stand; and it had been lost,” Roosevelt wrote bitterly.72

That night he headed West to clear his mind and recondition his body. With unconscious symbolism, he proclaimed himself “especially hot for bear.”73

![]()

JUST AS THE SUN sank behind the Rockies, and dusk crept down into the Montana foothills, he came across a brook in a clearing carpeted with moss and kinni-kinic berries.74 He spread his buffalo-bag across a bed of pine needles, dragged up a few dry logs, and then strolled off, rifle on shoulder, to see if he could pick up a grouse for supper.

Walking quickly and silently through the August twilight, he came to the crest of a ridge and peeped over it. There, in the valley below, was his grizzly. It was ambling along with its huge head down—a perfect shot at sixty yards. Roosevelt fired. His bullet entered the flank, ranging forward into the lungs. There was a moaning roar, and the bear galloped heavily into a thicket of laurel. He raced down the hill in pursuit, but the grizzly disappeared before he could cut it off. A peculiar savage whining told him it had not gone far. Unwilling to risk death by following, he began to tiptoe around the thicket, straining for a glimpse of fur through the glossy leaves. Suddenly they parted, and man and bear encountered each other.

He turned his head stiffly toward me; scarlet strings of froth hung from his lips; his eyes burned like embers in the gloom. I held true, aiming behind the shoulder, and my bullet shattered the point or lower end of his heart, taking out a big nick. Instantly the great bear turned with a harsh roar of fury and challenge, blowing the bloody foam from his mouth, so that I saw the gleam of his white fangs; and then he charged straight at me, crashing and bounding through the laurel bushes so that it was hard to aim. I waited till he came to a fallen tree, raking him as he topped it with a ball, which entered his chest and went through the cavity of his body, but he neither swerved nor flinched, and at that moment I did not know that I had struck him. He came steadily on, and in another second was almost upon me. I fired for his forehead, but my bullet went low, entering his open mouth, smashing his lower jaw and going into the neck. I leaped to one side almost as I pulled the trigger; and through the hanging smoke the first thing I saw was his paw as he made a vicious side blow at me. The rush of his charge carried him past. As he struck he lurched forward, leaving a pool of bright blood where his muzzle hit the ground; but he recovered himself and made two or three jumps onward … his muscles seemed suddenly to give way, his head drooped, and he rolled over and over like a shot rabbit.75

Next morning Roosevelt laboriously hacked off the grizzly’s head and hide. Somehow, en route back to Oyster Bay, he lost the skull, and had to replace it with a plaster one before proudly laying the pelt at Edith’s feet. Of all his encounters with dangerous game, this had been his most nearly fatal; of all his trophies, this—with the possible exception of his Dakota buffalo—was the one he loved best.76

![]()

ROOSEVELT FOUND HIMSELF something of a literary celebrity in the fall of 1889. His Winning of the West was not only a bestseller (the first edition disappeared in little more than a month)77 but a succès d’estime on both sides of the Atlantic. In Britain, where it rated full-page notices in such periodicals as the Spectator and Saturday Review, Roosevelt was hailed as a historian of model impartiality; the Athenaeum went as far as to call him George Bancroft’s successor.78 In America, scholars of the caliber of Fredrick Jackson Turner and William F. Poole praised The Winning of the West as a work of originality, scope, and power. Turner called it “a wonderful story, most entertainingly told.” He commended the author for his “breadth of view, capacity for studying local history in the light of world history, and in knowledge of the critical use of material.”79 Dr. Poole, representing the older generation of historians, wrote a rather more balanced criticism in The Atlantic Monthly:

The Winning of the West will find many appreciative readers. Mr. Roosevelt’s style is natural, simple, and picturesque, without any attempt at fine writing, and he does not hesitate to use Western words which have not yet found a place in the dictionary. He has not taken the old story as he finds it printed in Western books, but has sought for new materials in manuscript collections … Few writers of American history have covered a wider or better field of research, or are more in sympathy with the best modern method of studying history from original sources; and yet … we have a feeling that he might profitably have spent more time in consulting and collating the rich materials to which he had access.…

It is evident from these volumes that Mr. Roosevelt is a man of ability and of great industry. He has struck out fresh and original thoughts, has opened new lines of investigation, and has written paragraphs, and some chapters, of singular felicity … Mr. Roosevelt, in writing so good a work, has clearly shown that he could make a better one, if he would take more time in doing it.80

But the review which, paradoxically, gave Roosevelt the most satisfaction was a vituperative and error-filled notice in the New York Sun. Its pseudonymous author accused him of plagiarism and fraud: Theodore Roosevelt could not have written The Winning of the West alone. “It would have been simply impossible for him to do what he claims to have done in the time that was at his disposal.” Another scholar, at least, must be responsible for the book’s voluminous footnotes and appendices.81

Roosevelt had no difficulty in guessing the critic behind the pseudonym: James R. Gilmore, a popular historian whose own works had been rendered obsolete by The Winning of the West.82 He sent the Sun a long and humiliating rebuttal, identifying Gilmore by name and demolishing his charges, one by one, with ease. In conclusion he offered a thousand dollars to anybody who could prove he had a collaborator. “The original manuscript is still in the hands of the publishers, the Messrs Putnams, 27 West 23rd Street, New York; a glance at it will be sufficient to show that from the first chapter to the last the text and notes are by the same hand and written at the same time.”83

Gilmore was forced to issue an answer over his own signature.84 Unable to substantiate any of his charges, or refute any of Roosevelt’s answers, he desperately accused the latter of pirating certain “facts” hitherto published only by himself. Roosevelt annihilated him in a letter too long and too scholarly to quote here—unfortunately, for it is a classic example of that perilous literary genre, the Author’s Reply. He begged Mr. Gilmore to identify the “facts,” if any, that he had unwittingly plagiarized from him, for he did not wish The Winning of the West to contain any fiction. In passing he noted that the critic had not taken up his challenge to examine the manuscript. “It makes one almost ashamed to be in a controversy with him. There is a half-pleasurable excitement in facing an equal foe; but there is none whatever in trampling on a weakling.”85

![]()

ROOSEVELT HAD NO SOONER blotted the last line of this letter, in his Washington office on 10 October, than a telegram from Oyster Bay announced the premature birth of his second son, Kermit.86 He left at once for Sagamore Hill, chartering a special train in order to be at Edith’s bedside that night. For the next two weeks he stayed home while she “convalesced,” reading to her and trying to conceal his renewed worries about money.87 The time for their general move to Washington was approaching; how he would finance it he simply did not know.

What was worse, for the first time he felt really insecure in his job. A “scream for his removal”88 was gathering in the capital. Inevitably, word had gotten out that he had found a favored place for Hamilton Shidy, the Milwaukee informer. Frank Hatton of thePost was going to demand a House investigation; the majority of spoilsmen would undoubtedly agree; it was not farfetched to imagine himself being humiliated in a Congressional witness-box just when his wife arrived in town and began to receive Washington society.

Roosevelt put all his faith in the Annual Report of the Civil Service Commission, which would soon become due. It must be so incisive, so powerfully worded, that President Harrison dare not find fault with it; it must serve notice on Congress that Theodore Roosevelt was no mere publicist, but a solid, authoritative Commissioner.

He spent the last days of his thirtieth year working on the report at Sagamore Hill. There was no attempt to consult his colleagues on the Civil Service Commission: he “hardly dare trust” nice, dim Hugh Thompson with such work, and “as for Lyman, he is utterly useless … I wish to Heaven he were off.”89 One can almost hear Henry Cabot Lodge sigh as he read those words. After only five months on the Civil Service Commission, Theodore’s hunger for absolute power was already asserting itself.

At the end of October, Roosevelt returned to Washington and rented the nearest thing to a decent house he could afford. It was about one-tenth the size of Sagamore Hill, but that could not be helped. At least the location was good—at 1820 Jefferson Place, off Connecticut Avenue. The Lodges, who were at last back in town, lived only a stone’s throw away. Until Edith joined him at the end of the year, they would see that he did not starve.

He sent his report to the White House on 14 November,90 and plunged into the final rounds of a political battle which had involved him, on and off, since early summer. Two formidable rivals—Thomas B. Reed of Maine and William McKinley of Ohio—were fighting for the Speakership of the House. Roosevelt campaigned for the former, having assured the latter he would one day vote for him as President of the United States.91 McKinley “was as pleasant as possible—probably because he considered my support worthless.”92 When Congress convened on 2 December, Roosevelt had the satisfaction of seeing Reed elected. In the event of a House investigation, he could now count on the support of the most powerful man on Capitol Hill. A few days later, President Harrison added to his sense of security by approving his report and recommending that the Civil Service Commission’s budget be increased.93

Christmas found Roosevelt at Sagamore Hill with “Edie and the blessed Bunnies,” wondering, as he unwrapped his presents, if Bamie was going to give him Motley’s Letters or Laing’s Heimskringla.94 After the holiday he brought his excited family to Washington, installed them at Jefferson Place, and on 30 December read a paper on “Certain Phases of the Westward Movement in the Revolutionary War” to the American Historical Association.

What funnily varied lives we do lead, Cabot! We touch two or three little worlds, each profoundly ignorant of the others. Our literary friends have but vague knowledge of our actual political work; and a goodly number of our sporting and social acquaintances know us only as men of good family, one of whom rides to hounds, while the other hunts big game in the Rockies.…95

![]()

BENJAMIN HARRISON’S HANDSHAKE was, in the words of one recipient, “so like a wilted petunia”96 that only a Roosevelt could react warmly to it. The Civil Service Commissioner was noticeably the most ebullient guest at the White House reception on 1 January 1890. He crushed the petunia heartily, and insisted, at some length, that his Chief have a Happy New Year.97

Sincere or not, Roosevelt’s wishes came true. 1890 was indeed a year of honeyed contentment for the President and his Administration. Republicans were firmly in control of Congress, and thousands of party workers had swarmed, despite frantic net-waving by the Civil Service Commission, back into the federal beehive. The Union was richer by four new states (North Dakota, South Dakota, Montana, and Washington), and two more would soon be admitted (Wyoming and Idaho). All six were firmly committed to the GOP. Political prospects could not be more favorable—at least through the November elections—and as for economic indicators, they were almost too good to be true. “Our country’s cornucopious bounty seemed to overflow,” sighed one Washington matron forty years later. “Never again shall any of us see such abundance and cheapness, such luxurious well-being, as prosperous Americans then enjoyed.”98

The new social season, beginning with the President’s reception, was correspondingly brilliant and lavish. Roosevelt was already popular enough (even among those Cabinet officers who were his sworn enemies politically) to take his pick of invitations. Delighted to have a young and attractive wife to squire around town, he dined out at least five times a week, going on to all the best suppers and balls. Browsing at random through names dropped in his weekly letters to Bamie, one finds those of the Vice President, the Secretaries of State, War, Navy, and Agriculture, ministers from Great Britain and Germany, a Supreme Court Justice, the Speaker of the House, numerous Senators and Congressmen, the president of the American Historical Association, and two “inoffensive” English peers. While crowding such persons into his own little dining room, Roosevelt was embarrassed at not being able to afford champagne,99 but nobody, so far as he could see, seemed to mind very much. He and Edith calculated their guest-lists “pretty carefully,” trying to maintain the right admixture of power, brains, and breeding.100

Gradually, as the season progressed, a group of favored friends began to form. Roosevelt was not so much the leader of this group as its most gregarious member, equally at ease with all.101 Towering—literally—above the others was Speaker Reed, all six feet two inches and three hundred pounds of him, a vast, blubbery whale of a man, poised on two flipper-like feet. Reed was the cleverest politician in Washington, and the most domineering: his gong-like voice, which filled every corner of the House with ease, could reduce even Roosevelt to silence. Indeed, there was little to be said when the big man had the floor, for he gave off such waves of authority that few men dared contradict him.102 That February he had already established himself as one of the great Speakers of the House, having just made his historic ruling against members who refused to stand up and be counted. (“The Chair is making a statement of fact that the gentleman is present. Does the gentleman deny it?”103) His wit was brilliant and usually cruel. “They never open their mouths,” he complained of two House colleagues, “without subtracting from the sum of human knowledge.” Asked to attend the funeral of a political enemy, he refused, “but that does not mean to say I do not heartily approve of it.”104 Sooner or later Reed, who kept a diary in French and owned the finest private library in Maine, made his political associates aware of their intellectual ordinariness, but by the same token few questioned his leadership. “He does what he likes,” wrote Cecil Spring Rice, “without consulting the Administration, which he detests, or his followers, whom he despises.”105

Tom Reed came again and again to the tiny house on Jefferson Place, usually with Congressman Henry Cabot Lodge on his arm. Lodge, in turn, escorted Roosevelt as frequently to Lafayette Square, where two small, rich, bearded men lived side by side in a pair of red Richardson mansions. John Hay and Henry Adams were both fifty-two, and both were completing massive works of American history. They were famous for the excellence of their connections, the brilliance of their conversation, and the quality of the guests they invited to dinner. To be entertained by either (or both, for they were virtually inseparable, and liked to call each other “Only Heart”) was to count among the intellectual and social elite of Washington.106 Roosevelt’s references gained him instant access to this charmed circle.

Hay, of course, was an old family friend. Two decades had passed since that windy September night when little Teedie Roosevelt first shook his hand; Hay had subsequently distinguished himself as a diplomat, editor, poet, and Assistant Secretary of State under President Hayes. Now he was parlaying his youthful experiences as secretary to Abraham Lincoln into a ten-volume biography clearly destined for classic status.107 Ill-born but well-married, John Hay was a spectacularly fortunate man.108 Ruddy with reflected glory, sleek with inherited wealth, he was enough of a personality in his own right to escape censure. No man, with the possible exception of Henry Adams, wrote better letters; not even Chauncey Depew could match his after-dinner wit; no chargé d’affaires bent more gracefully over a lady’s hand, or murmured endearments through such immaculate whiskers. If Hay’s hidden lips never quite touched flesh, if he winced when slapped on the back, few were offended, for he associated only with those who understood delicacy and nuance. The son of Mittie Roosevelt understood these things very well, and was therefore cordially received.

Henry Adams was rather more formidable. Flap-eared, balding, wizened, secretive, and shy, he looked not unlike one of his own Oriental monkey-carvings. There was also something simian about his behavior, which alternated between bursts of chattering effusiveness and sudden, cataleptic withdrawal. Yet even when sunk nerveless in the depths of a leather armchair, Adams was listening, watching out of the corner of his eye every flicker of activity in his vast drawing room.

It was, perhaps, the most privileged space in the United States, this book-lined chamber with its three huge windows overlooking Lafayette Square. Whichever window one stood at, the White House floated serenely in center frame, as if to remind one that the grandfather and great-grandfather of the little man in the chair had once lived there. Adams himself rarely bothered to glance at the view; he preferred to sit gazing at the marble slabs around his fireplace: “onyx of a sea-green translucency so exquisite as to make my soul yearn …”109 It would be lèse-majesté to suggest that he cross the square and pay his respects. Presidents, on the other hand, were welcome to visit him—assuming they could contribute something worthwhile to the conversation. If, like Rutherford B. Hayes, they could not, Adams merely ignored them until they went away.110

It was difficult not to be intimidated by Henry Adams. Not only was his blood the bluest in the land, his wisdom was so profound, and his education (a word he loved to use) so universal, that artists, geologists, poets, politicians, historians, and philosophers deferred to him in their respective fields. Roosevelt had only to glance at the proofs of his nine-volume History of the United States of America, 1801–1817, which Adams was then checking, to see that here was learning, grace, and fluidity to which he could not hope to aspire. The Winning of the West seemed amateurish in comparison. Insofar as a coarse intellect can comprehend a fine one, he had to acknowledge his own inferiority, while preserving a healthy contempt for the older man’s vein of “satirical cynicism.”111His own robust masculinity sensed a certain feminine reticence, a distaste for action and rough involvement, which rescued him from awe. Years after, he would write of Henry Adams and that other “little emasculated mass of inanity,”112 Henry James, that they were “charming men, but exceedingly undesirable companions for any man not of strong nature.”113

Adams, for his part, found Roosevelt repulsively fascinating.114 The young commissioner’s vitality was indecent, his finances ridiculous, and he was about as subtle, culturally speaking, as a bull moose; yet there was no denying his originality, and his extraordinary ability to translate thought into deed—with such blinding rapidity, sometimes, that the two seemed to fuse. Roosevelt had “that singular primitive quality that belongs to ultimate matter—the quality that medieval theology assigned to God—he was pure act.”115 He came flying up the steps of 1603 H Street at such a rate that one could sense, as one shrank into one’s armchair, the power that drove him. This young man was equally at home on Adams’s Oriental hearthrug, the spit-streaked stairway of the Senate, or the sod floor of a cowboy cabin. His self-assurance, as he paced up and down blustering about the “white-livered weaklings” who ran the government, was both amusing and frightening. Adams was to spend the next eleven years waiting for the inevitable moment when Roosevelt moved into the house of his ancestors, marvelling at the momentum, “silent and awful like the Chicago express … of Teddy’s luck.”116

The other regular visitors to No. 1603 included Cecil Spring Rice, Clarence King, an eccentric, globe-trotting geologist whose conversation was as coruscating as the specimens clinking in his pockets, and John La Farge—tall, sickly, saturnine, a genius in thedifficult art of stained glass, and in the even more difficult art of writing about it. Equally brilliant, though taciturn and absent-minded, was the sculptor Augustus Saint-Gaudens. He was then at work on his masterpiece, the memorial to Mrs. Henry Adams in Rock Creek Cemetery.117 Senator James Donald Cameron, beetle-browed and gruff, stopped by often, unaware that he was welcome mainly on account of his young wife, Elizabeth, the most beautiful woman in Washington. (Adams was secretly in love with her; so, to a lesser extent, were Hay and Spring Rice; the three men vied with one another in writing sonnets to her charms.) “Nannie” Cabot Lodge was almost as beautiful as Mrs. Cameron, with her sculptured profile and violet eyes. Famous for her tact, she spent much of her time placating those whom her supercilious husband had offended. Many other rich and talented people crowded Adams’s salon for good food, good champagne, and good talk—the best, perhaps, that has ever been heard in Washington.118

During the season of 1890, Roosevelt’s position in this “pleasant gang,” as John Hay liked to call it, was distinctly that of junior member. He received more in the way of ideas and entertainment than he could possibly bestow. It may be wondered why he was so immediately popular. Perhaps the clue lies in a remark made by one who did not quite make it into the Adams circle: “There was a vital radiance about the man—a glowing, unfeigned cordiality towards those he liked that was irresistible.” Men of essentially cold blood, like Reed and Adams and Lodge, grew dependent upon his warmth, as lizards crave the sun.119

Roosevelt’s ascent into the stratosphere of Washington society was not accompanied by any easing of his difficulties as Civil Service Commissioner. If anything, they were worse now Congress was in session, for spoilsmen formed a majority in both Houses.120President Harrison’s request for more money for the Commission met with determined opposition and delay. Meanwhile the agency was so short of clerks it had fallen three months behind in the marking of examination papers. “No department of the Government is run with such absolutely insufficient means as ours,” Roosevelt complained to a Congressman, “and I may say also that no officers of corresponding rank to that of the Civil Service Commissioners are so insufficiently paid.”121 But the House was more interested in Frank Hatton’s now almost daily editorials charging the Commissioners with inefficiency, corruption, and abuse of the law. While trumpeting the Roosevelt/Shidy affair as evidence of gross favoritism, Hatton also accused Commissioner Lyman of employing a relative who trafficked in stolen examination questions. Clearly something had to be done, and on 27 January Congress ordered a full investigation by the House Committee on Reform in the Civil Service. A prominent spoilsman, Representative Hamilton G. Ewart of South Carolina, was appointed prosecutor, and Frank Hatton chosen to assist him.122

![]()

AS ALWAYS WHEN CONFRONTED with a challenge, Roosevelt instantly took the offensive. He intended so to dominate the hearings that he would be entirely vindicated, and confirmed in the public mind as leader of a just and effective agency. At the preliminary hearing he insisted that any charges against him be separate from those involving Commissioner Lyman. While assuring the committee—repeatedly—that he was “dee-lighted” to be investigated, he “did not want to be tried for other people’s faults.”123 This was hardly a compliment to his senior colleagues, but instinct told him that Lyman’s case was more embarrassing than his own. Frank Hatton, coming face to face with Roosevelt for the first time, was clearly overawed by his pugnacious gestures and snapping teeth. Afterward the editor announced that he had nothing against Roosevelt personally; he merely wished to expose the weaknesses of the Civil Service Commission as presently constituted. Should the agency be reorganized with only one man at its head, “he would be very glad to see Mr. Roosevelt appointed.”124

The hearings proper began on 19 February, with a reading of twelve charges indicting the Civil Service Commission of various faults of management and failure to uphold the law. The fourth alleged

… that Theodore Roosevelt, a member of the Commission, secured the appointment of one Hamilton Shidy to a place in the Census Bureau, when it was notoriously known to the said Roosevelt that the said Shidy … had persistently and repeatedly violated his oath of office in making false certifications and in not reporting violations of the Civil Service law by the postmaster at Milwaukee to the Commission at Washington.125

Thanks to a prolonged examination of the charge against Commissioner Lyman, which Roosevelt listened to looking as if he had a bad smell under his nose,126 his own case did not come up for another week. Finally, on the afternoon of Friday, 28 February, Hamilton Shidy was sworn in.

The hapless clerk confirmed that Roosevelt had promised him protection in exchange for testimony against Postmaster Paul in June 1889. Subsequently “I obtained a position in the Census Office … Mr. Roosevelt being particularly friendly and kindly to me in that respect.”127 Sniggers were heard in various parts of the room. Hatton, cross-examining the witness, tricked him into admitting that if he was again asked by a corrupt superior to falsify government records, he would again do so. This was a blow to Roosevelt, who had hoped that Shidy’s moral character would stand up to scrutiny. “I do not care to talk to you any more,” he told him afterward. “You have cut your own throat.”128

Hatton made the most of Roosevelt’s discomfiture in huge, front-page headlines next morning:

SHIDY PROVES TO BE BOTH A SCOUNDREL

AND A FOOL—

And Roosevelt, knowing his Infamous Character, Forced him into an Important Position

THE MOST SHAMEFUL TESTIMONY EVER OFFERED

Even Roosevelt Hung his Head in Shame

As the Disgraceful Story was Unfolded.129

When the hearings resumed on 1 March, Robert B. Porter, Superintendent of the Census, took the stand. In response to questioning by Prosecutor Ewart, he testified that Roosevelt had once approached him on behalf of a Milwaukee man who had been “unjustly dismissed” for helping the Civil Service Commission with their work, “and he asked if I could find a place in my office for such a man.”130 But Roosevelt had not said a word about Shidy’s misdeeds.

|

EWART |

If Mr. Roosevelt had told you that this man had persistently violated the law, had stuffed the lists of eligibles, had mutilated the records and made false certifications, would you have appointed him in your bureau? |

|

PORTER |

I certainly should not. |

|

EWART |

I know you would not! |

Aware that things were not going too well, Roosevelt jumped to his feet.

|

ROOSEVELT |

You knew I had made a report on the subject? |

|

PORTER |

I knew that— |

|

ROOSEVELT |

And that Shidy and Paul were implicated in that report, and the report was public and that the Postmaster-General had in writing indicated to you his approval of Shidy’s transfer, he having known all about my report and having acted upon it? |

|

PORTER |

That is true, I think.131 |

There was a stir in the room. Roosevelt was clearly willing to drag John Wanamaker into the proceedings. Porter, thoroughly alarmed now, refused to say anything more that might offend the Civil Service Commissioner.

Roosevelt replaced him on the stand and launched into “a brief statement.” The next four pages of the printed transcript, hitherto well splotched with white space, are a solid gray mass of impassioned speech. Speaking with such explosive vigor his spectacles seemed in constant danger of falling off, the Commissioner declared that Shidy had been protected only “because he had done right in trying to atone for his wrongdoing.” Both Porter and Wanamaker had agreed to the transfer, and both must have been aware of Shidy’s record, since the Milwaukee report “had been spread—broadcast—through the press.” As for himself, said Roosevelt, his conscience was clear. “The Government must protect its witnesses who are being persecuted for telling the truth.”132

In an openly hostile cross-examination, Ewart harped on the undeniable fact that Roosevelt had glossed over Shidy’s background when negotiating his transfer. The witness grew flustered.

|

EWART |

When a man commits perjury … and when he confesses he has made false certifications and has persistently and repeatedly violated the law, is it your belief as a Civil Service Reformer … that he should be reinstated in office? |

|

ROOSEVELT |

Do you mean in the same position? |

|

EWART |

The same position, or any position in Government. |

|

ROOSEVELT |

That would depend on the circumstances of the case. |

|

EWART |

Take the circumstances of the Shidy case. |

|

ROOSEVELT |

I mean to say my action was right in the Shidy case … (to the committee, gesticulating) Mr. Ewart is evidently wishing me to state that if these circumstances arose I would not act as I did then, giving the impression that I was sorry for what I had done. On the contrary, I think I was precisely right, and I am glad I took that stand.133 |

This last declaration, with its rhythmic use of the personal pronoun, has a familiar ring to students of the later Roosevelt. Many times, as he grew older and more set in his ways, he would protest the moral rightness of his decisions; justice was justice “because I did it.”134

![]()

THE CROSS-EXAMINATION continued. How did Roosevelt know the Postmaster General had been familiar with his report? “I did not read it aloud to him,” Roosevelt replied sarcastically, “but he had acted upon it, and the presumption is fair that he had read it.” Commissioner Thompson stood up to make a statement of full support for Roosevelt’s actions. But before the old man could say much, the door of the hearing room flew open and in strode John Wanamaker.135

The Postmaster General was hurriedly sworn. Although wreathed in smiles as usual, he did not relish being implicated in Roosevelt’s testimony, and wished to make it clear that he had been an innocent party to the transfer. Roosevelt had spoken so glowingly of Shidy that he had been happy to agree. “I always express myself as pleased if employment is given to a person that Roosevelt might recommend.”136 If he had only known the truth about Shidy, of course …

Stung, Roosevelt leaped to the attack.

|

ROOSEVELT |

All these facts … are in a report that we made to the President of the United States on this matter. You had that report, and had acted upon it, had you not? |

|

WANAMAKER |

We had the report. |

|

ROOSEVELT |

And you had acted upon it, had you not? |

|

WANAMAKER |

How do you mean, “acted upon it”? |

|

ROOSEVELT |

You referred to it … in your letter notifying Mr. Paul that you had accepted his resignation. If there is any doubt in your mind, you can produce the letter, I presume? |

|

WANAMAKER |

I cannot say how much influence the Civil Service report had upon me … |

|

ROOSEVELT |

Would you send a copy of the letter? … My memory is very clear that in that letter you referred to this report. |

|

WANAMAKER |

I will furnish it with pleasure.137 |

The letter was duly furnished, but with little pleasure, for it proved the accuracy of Roosevelt’s memory, as opposed to Wanamaker’s convenient amnesia.

Although the hearings dragged on for another week, neither Hatton nor Ewart was able to uncover any evidence of maladministration by the Civil Service Commission. There was a series of interminable examinations by Roosevelt of George H. Paul, who hadbeen brought in from Milwaukee especially for that purpose. The humiliated ex-postmaster sat for three days in his chair, helpless as a trussed turkey, while Roosevelt determinedly pulled out his feathers, one by one. Squawks of protest—that Paul had given all this testimony before and had already suffered amply for it—went unheeded. Roosevelt seemed determined to show the committee what an angry Civil Service Commissioner looked like in action. Not until late in the afternoon of Friday, 7 March, did the chairman tactfully suggest that enough was enough.138

![]()

EVEN BEFORE the committee filed its formal report, it was plain that Roosevelt had scored a personal triumph. He had dominated the hearings from the first day to the last, and had somehow managed to arouse sympathy for his patronage of “Shady Shidy,” as that gentleman was now known. His prestige as Civil Service Commissioner had been greatly enhanced, at the expense of the discredited Lyman and the reticent Thompson. The committee was rumored to be in favor of recommending the creation of a single-headed Commission, with himself the obvious choice as chief, but Roosevelt, surprisingly, opposed this idea, saying that it was attractive but premature. To put a Republican in sole control, he argued, would compromise the Commission’s non-partisan image and make it vulnerable to changing majorities in Congress.139 This was true enough, but sophisticated observers could detect signs of a larger, more long-term ambition in Roosevelt’s modesty. He already had all the power the inadequate Civil Service Law allowed him; killing two colleagues off would not increase it. At thirty-one, he could afford to wait a few more years for real power.

Roosevelt himself admitted, later in life, that it was about this time that he began to cast thoughtful eyes upon 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue. “I used to walk by the White House, and my heart would beat a little faster as the thought came to me that possibly—possibly—I would some day occupy it as President.”140 Jeremiah Curtin, the translator of Sienkiewicz, happened to catch him in the act one day, during a visit to the White House with Representative Frederick T. Greenhalge of the House Civil Service Committee.“That man,” said Curtin, “looks precisely as if he had examined the building and, finding it to his liking, had made up his mind to inhabit it.” “I must make you acquainted with him,” replied Green-halge. “But first listen to a prophecy: when he wants this house he will get it. He will yet live here as President.”141

![]()

MARCH MERGED INTO APRIL, April into May, but the committee, plagued by absenteeism, kept postponing its report. Roosevelt grew impatient and nervous. “It is very important that the present Commission be given an absolutely clean bill of health … a verdict against us is a verdict against the reform and against decency.”142 Frank Hatton, too, seemed bothered by the suspense; his editorial attacks on Roosevelt grew hysterical. “This scion of ‘better blood,’ ” he raged, “this pampered pink of inherited wealth … this seven months’ child of conceited imbecility [is] a sham, a pretender and a fraud as a reformer and a failure as a business man.” Eventually the flow of vituperation ceased. “The Post … having passed the pestiferous Roosevelt between its thumb-nails, drops him and awaits the report of the investigating committee.”143

As usual in times of stress, Roosevelt distracted himself with literature, and worked doggedly on his long-postponed history of New York City. “How I regret ever having undertaken it!” By way of relaxation he wrote three or four hunting pieces for Century, and, by way of duty, some very dull articles on Civil Service Reform. He apologized to George Haven Putnam for having to abandon—temporarily—Volumes Three and Four of his magnum opus. “I half wish I was out of this Civil Service Commission work, for I can’t do satisfactorily with The Winning of the West until I am; but I suppose I ought really to stand by it for at least a couple of years.”144

![]()

HE SPENT ONE of the most important weekends of his life on 10 and 11 May, reading from cover to cover Alfred Thayer Mahan’s new book, The Influence of Sea Power upon History.145 Since the publication of his own Naval War of 1812 he had considered himself an expert on this very subject, and had argued, passionately but vaguely, that modernization of the fleet must keep pace with the industrialization of the economy. But he had never questioned America’s traditional naval strategy, based on a combination of coastal defense and commercial raiding. Now Mahan extended and clarified his vision, showing that real national security—and international greatness—could only be attained by building more and bigger ships and deploying them farther abroad. While advocating the constant growth of the American Navy, Mahan paradoxically insisted that its power be concentrated at various “pressure points” which controlled the circulation of global commerce. By striking quickly and sharply at any of these nerve centers, the United States could paralyze whole oceans. Mahan supported his thesis with brilliant analyses of the strategies of Nelson and Napoleon, proving that navies could be more effective than armies in determining the relative strength of nations. He also explained the intricate relationships between political power and sea power, warfare and economics, geography and technology. Roosevelt flipped the book shut a changed man. So, as it happened, did Kaiser Wilhelm II of Germany, when he read it—not to mention various Lords of the British and Japanese Admiralties, and officials throughout the Navy Department of the United States. More than any other strategic philosopher, Alfred Thayer Mahan was responsible for the naval buildup which preoccupied these four nations at the turn of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries; more than any other world leader of the period, Theodore Roosevelt would glory in The Influence of Sea Power upon History, both as a title and as a fact.146

![]()

THE REPORT OF the House committee’s investigation, filed 13 June 1890, stated that “the public service has been greatly benefited, and the law, on the whole, well-executed” by all three Commissioners. Charles Lyman was mildly censured for a certain “laxity of discipline” in administrative affairs, while his colleagues received unqualified praise. “We find that Commissioners Roosevelt and Thompson have discharged their duties with entire fidelity and integrity,” the document stated.147 “WHITEWASH!” screamed theWashington Post, but most press comment was approving. The New York Times and Evening Post went so far as to criticize President Harrison and Postmaster General Wanamaker for not supporting the Civil Service Commission. Roosevelt returned with some relief to bureaucratic work.148 During his first year in office he had attracted a greater glare of publicity than his eight predecessors put together. It was time to retire temporarily to the wings before he was accused of hogging the footlights. Already theSaturday Globe was warning: “There is, perhaps, no man in the country more ambitious than this young New York politician.”149

Once again Washington began to drowse in summer heat. Edith and the children returned to Sagamore Hill; Cecil Spring Rice fled for the cool shores of Massachusetts; Henry Adams prepared to depart for the South Seas. Congress remained in session, with Speaker Reed presiding over the House in flannels and canvas shoes, a yellow scarf around his enormous waist.150 Roosevelt went to Oyster Bay as often as he could, but pressure of work (for the Commission was still backlogged) continually drew him back. He managed to finish his “very commonplace little book” on New York by the beginning of August, and spent the next three weeks feverishly trying to clear his desk. Another Western trip was in the offing, this time to Yellowstone, which he wished to inspect on behalf of the Boone & Crockett Club, but administrative difficulties nearly made him cancel it. “Oh, Heaven, if the President had a little backbone, and if the Senators did not have flannel legs!”151

The first of September found Roosevelt in a large family party, including his wife and two sisters, heading West to Medora and the Rockies. Impressed as he was by the splendors of Yellowstone, he reserved his most admiring adjectives for Edith. The sight of that demure, book-loving lady cantering across the prairie on a wiry horse seemed to have shocked him into a renewed awareness of her charms. “She looks just as well and young and pretty as she did four years ago when I married her … she is as healthy as possible, and so young-looking and slender to be the mother of those two sturdy little scamps, Ted and Kermit.”152

![]()

WASHINGTON WAS STILL deserted when he got back there in early October. Benjamin Harrison was at home, however, so Roosevelt paid a friendly call. Harrison, who had gotten into the habit of drumming his fingers nervously during their interviews, gave him a frigid reception. Evidently the White House wanted to have nothing further to do with Civil Service Reform. “Damn the President! He is a cold-blooded, narrow-minded, prejudiced, obstinate, timid old psalm-singing Indianapolis politician.”153

The November Congressional elections were disastrous for the Republican party, due mainly to an unpopular tariff measure which William McKinley had pushed into law at the end of the last session. With prices on manufactured goods rising daily, voters threw the culprit out of office—severely damaging his presidential prospects—and filled the House with the largest Democratic majority in history.154 Roosevelt, who had never liked the McKinley bill, began to mutter dire predictions about Cleveland recapturing the White House in 1892. But with his family reinstalled in town, and Henry Cabot Lodge by great luck returned to Congress, he found it impossible to be gloomy. Indeed, Roosevelt was conspicuously the most cheerful Republican in Washington that winter. “He continues to wear the nattiest and most stylish grey trousers, and the most boyish hat he can buy,” reported a local correspondent, “and he whistles jovially as he legs it down to the rooms of the Civil Service Commission.”155

Christmas was spent at 1820 Jefferson Place, and Roosevelt rejoiced in the event as much as any of his children:

Such nice stockings, with such an entrancing way of revealing in their bulging outline the promise of what was inside! They burrowed into them with their eager, chubby little hands, and hailed each new treasure with shouts of delight. Then after breakfast we all walked into the room where the big toys, so many of them! were, on the tables; and I suppose Alice and Ted came as near to realizing the feelings of those who enter Paradise as they ever will on this earth.156

That, according to his old friend Mrs. Winthrop Chanler, was the essence of Theodore Roosevelt, at least during his early years in Washington. “Life was the unpacking of an endless Christmas stocking.”157

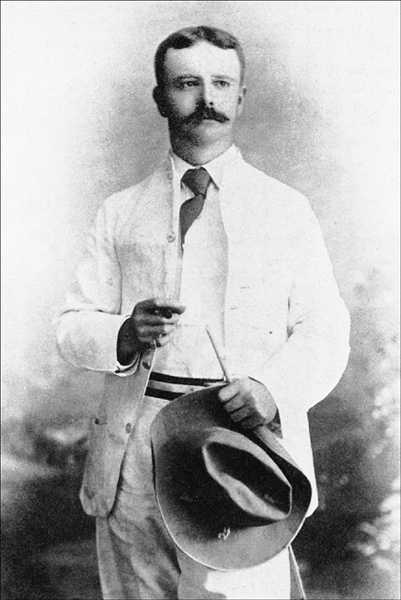

“He is evidently a maniac morally no less than mentally.”

Elliott Roosevelt about the time of his marriage to Anna Hall. (Illustration 16.2)