Then forth from the chamber in anger he fled

And the wooden stairway shook with his tread.

![]()

IN ADDRESSING HIMSELF to Mrs. Bellamy Storer rather than Mr. Bellamy Storer, Roosevelt flatteringly acknowledged that lady’s superior political muscle. He had known her since his early Washington days,1 and had plenty of opportunity to see her in action as a lobbyist for the Roman Catholic Church. Mrs. Storer was a wealthy and formidable matron whose eyes burned with religious fervor, and whose jaw brooked no opposition from anybody—least of all William McKinley, whom she considered to be in her debt. The Presidential candidate had gratefully accepted $10,000 of Storer funds in 1893, when threatened with financial and political ruin. Mrs. Storer was now, three years later, expecting to recoup this investment in the form of various appointments for her near and dear.2

Roosevelt knew that she was fond of him, in an amused, motherly sort of way. She tended (like Edith) to treat him as if he were one of her own children. Years later, when events had conspired to embitter her toward him, she wrote that the “peculiar attraction and fascination” of the young Theodore Roosevelt “lay in the fact that he was like a child; with a child’s spontaneous outbursts of affection, of fun, and of anger; and with the brilliant brain and fancy of a child.”3

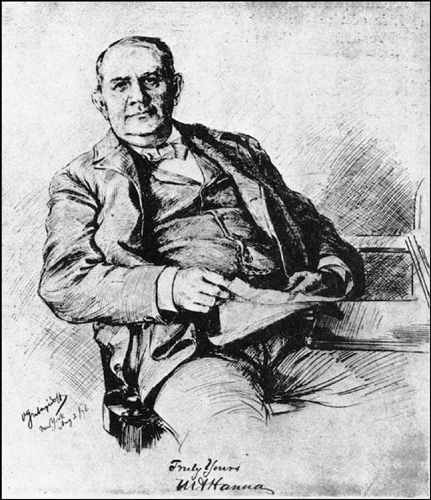

“A good-natured, well-meaning, coarse man, shrewd and hardheaded.”

Mark Hanna, sketched the day Theodore Roosevelt went boating with Mrs. Bellamy Storer. (Illustration 21.1)

Shrewdly playing upon her maternal sympathies in 1896, he said that his political unpopularity in New York was now so great that the future security of the Roosevelt “bunnies” depended on his getting a high-level post in Washington. Should he fail to negotiate one—or should McKinley (God forbid!) fail to win election, “I shall be the melancholy spectacle … of an idle father, writing books that do not sell!”

Mrs. Storer told him that she was “sure” something could be arranged; she and her husband would speak to McKinley in due course.4 Roosevelt, overjoyed, promised in return to work up support on the Republican National Committee for Bellamy Storer as a Cabinet officer, or Ambassador. The atmosphere in the rowboat grew increasingly cozy, and for the rest of her visit Mrs. Storer basked in Roosevelt’s good humor:

One never knew what he would say next. He was certainly very witty in himself, and he valued wit in others. He used during this period to get on the warpath over Sienkiewicz’s novels—The Deluge and Fire and the Sword—and when he was quite sated with slaughter his face would be radiant and he would shout aloud with delight. He seemed as innocent as Toddy in Helen’s Babies, who wanted everything to be “bluggy”.… His vituperation was extremely amusing, and he had a most extraordinary vocabulary … Never in our lives have we laughed so often as when Theodore Roosevelt of those days was our host.5

![]()

FOR ALL THE OPTIMISM flowing out of Sagamore Hill that summer weekend, Roosevelt and the Storers were uncomfortably aware of the proximity, in New York’s Waldorf Hotel, of a Cleveland millionaire who could turn their hopes to dust if he felt like it. Marcus Alonzo Hanna was more than McKinley’s manager and closest political adviser; he was now the party Chairman as well. In this double role he stood confirmed as the first countrywide political boss in American history.6 Cynical Democrats were saying that Hanna, not McKinley, had been nominated at St. Louis; cartoonists depicted the candidate as a limp puppet hanging out of his pocket.

Roosevelt, reacting as usual with electric speed to any new political stimulus, had already been to see Hanna twice. On 28 July, the same day the Chairman arrived in town to set up Republican National Headquarters, he visited him at the Waldorf. In the evening he had returned to dine privately with him and two members of the Executive Committee.7 A letter to Lodge, dated 30 July, shows how quickly and accurately he summed Hanna up: “He is a good-natured, well-meaning, coarse man, shrewd and hard-headed, but neither very farsighted nor very broad-minded, and as he has a resolute and imperious mind, he will have to be handled with some care.”8

Roosevelt does not seem to have told the Storers about these two previous meetings with Hanna. Possibly he wished them to follow an independent line with McKinley. At any rate he visited the Chairman again on Monday evening, 3 August, and fulfilled his part of the weekend bargain.9 Whether he did so quite as forcefully as he afterward implied to Mrs. Storer (“I spoke of Bellamy as the man for the Cabinet, either for War or Navy, or else go to France”)10 is doubtful, since Hanna was tired, and in no mood to discuss anything other than ways and means of winning in November. Roosevelt “thought it wise not to pursue the matter further.”11

Hanna’s exhaustion was nervous as well as physical. After nearly two years of working with full-time devotion to secure the nomination of McKinley—at a personal cost of $100,000—he wanted nothing so much as to take a long cruise up the New England coast, and let other Republicans manage the fall campaign. But a certain phenomenon, occurring in Chicago on 10 July, had “changed everything,” in his opinion. Alarming predictions of class war, communism, and even anarchy were coming in daily from the West: the political future suddenly seemed fraught with doom.12 Now was the time for all good men to come to the aid of the party, and Hanna bent his stout body to the task. Word went out from headquarters that he needed all the money and all the stump speakers he could get. Roosevelt, having little of the former, promptly volunteered to be one of the latter.13

The phenomenon in Chicago was that of William Jennings Bryan, an obscure thirty-six-year-old ex-Congressman from Nebraska, who by making one speech to the Democratic National Convention had created something akin to an emotional earthquake. Rising to speak on a currency resolution, Bryan had pleaded inspiringly for those rural poor to whom questions of high finance were of less importance than food and shelter. As a result, he was now the Democratic candidate for President, on a ticket so extremely radical as to cause large numbers of his party to bolt. Yet nobody, and certainly not Mark Hanna, discounted the threat he posed to William McKinley. For Bryan had that most potent of all political weapons: a sumptuous, sonorous voice, upon which he played like an open diapason. He also had a natural constituency—the farmers and field-hands of the South, Midwest, and West—not to mention those disadvantaged millions (Riis’s “Other Half”) who labored in farms and mines, or begged for work at factory doors, and lined up for soup in filthy municipal kitchens. Such people were ravished by his promises of dollars—more dollars for everybody, unlimited silver dollars which could be produced by the simple method of minting them freely and cheaply at a ratio of 16 to 1. The much more expensive gold dollars which McKinley proposed to keep in circulation were just too few to go around—or so Bryan seemed to be saying. His listeners might not quite grasp why one ratio was preferable to another, and phrases like “international agreement for bimetallism” meant little to cornhuskers who had never seen more than a few square miles of Iowa; but they thought they could understand his magnificently vague metaphors, particularly the one with which he had turned Chicago’s Coliseum into a howling madhouse:

You shall not press down upon the brow of labor this crown of thorns, you shall not crucify mankind upon a cross of gold!14

This was the phenomenon with which Mark Hanna had to deal in August 1896, and it is no wonder that he cut Roosevelt short on the subject of a Bellamy Storer. But he accepted his visitor’s offer of campaign help (perhaps the Chairman, in the back of his mind,recalled that other Chicago Convention when he and McKinley had seen this same young man briefly, raspingly capture the attention of seven thousand delegates).15

Roosevelt liked Hanna.16 There was something engagingly piglike about the man, with his snouty nostrils, thick pink skin, and short, trotting steps. His very business was in pig iron, and he had a grunting disdain for fine food and polite conversation. When he laughed (which was often), he snorted, and his language reeked of the farmyard. Yet Hanna’s very fleshiness, his love of reaching out and touching, was attractive to someone as physical as Roosevelt. Hanna had none of old Tom Platt’s dry secretiveness: he was blunt, honest, friendly, and unassuming, shamelessly addicted to sweets, which he would suck all day in his large loose mouth. But for all his naturalness, the Chairman was obviously a man of calculating intelligence. “X-Rays,” wrote one who met him at this time, “are not more penetrating than Hanna’s glance.”17

Surprisingly, for someone with so much power, the Chairman was not corrupt.18 He had no desire for Cabinet office; his ambition, as he reminded Roosevelt, was to elect McKinley. His love for that placid politician was as frank as it was naive: “He is the best man I ever knew!” Or: “McKinley is a saint.”19 As for the millions he had set out to raise, Hanna was too rich to want anything for himself. He treated campaign contributions much as he did iron ore in his Cleveland foundry—as raw material to be amassed in great quantities for the smelting of something solid. And indeed McKinley had an amusingly metallic quality, with his expressionless, perfectly cast features.20 Hanna had no doubt that in forging him he had created an ideal President, a man of steel to symbolize the new Industrial Age. The idea of William Jennings Bryan bringing back the Age of Agriculture was more than regressive: it was revolutionary.

Roosevelt could not help but be affected by the Chairman’s worried mood. Before their meeting on 3 August he had been confident of a Republican victory in November, but after it he wrote gloomily to Cecil Spring Rice, “If Bryan wins, we have before us some years of social misery, not markedly different from that of any South American republic … Bryan closely resembles Thomas Jefferson, whose accession to the Presidency was a terrible blow to this nation.”21

With that characteristic thrust, he braced himself for the biggest administrative challenge of his career as Commissioner: Bryan’s imminent arrival in Manhattan. The Democratic candidate had chosen Madison Square Garden—of all places—to open his campaign on 12 August, and Roosevelt, as president of the Board of Police, would be responsible for protecting his Jeffersonian person.

![]()

IT WOULD BE UNFAIR to accuse Roosevelt of deliberately allowing the Bryan meeting to degenerate into a noisy, embarrassing shambles. However, he was conspicuous by his absence from the Garden that night, and supervision of the crowd was left in the hands of a Republican inspector. The police proved remarkably adept at allowing gate-crashers in, and keeping ticket-holders out.22 Next morning the Sun and News excoriated “Teddy’s Recruits” for gross incompetence and inefficiency, and even The Times agreed that the job was “very bunglingly done.”23

Bryan, however, was the real culprit of the evening. No degree of police efficiency could have altered the fact that he was a stupendous disappointment. For once his oratorical gifts deserted him. Intimidated by the size of his audience, he merely read a prepared text on silver, which dragged on for two hours, to a steady tramp of exiting feet and calls of “Good night, Billy!”24

“Bryan fell with a bang,” Roosevelt crowed to Bamie. “He was so utter a failure that he dared not continue his eastern trip, and cancelled his Maine and Vermont engagements … I believe that the tide has begun to flow against him.”25

When Bourke Cockran, another celebrated speaker, took over the Garden on 19 August to put the case of gold, Roosevelt was there to prevent any repetition of the previous week’s fiasco. He personally supervised all security arrangements, and the evening went off smoothly. It was agreed next morning that the police had “retrieved their reputations.”26

![]()

WITH SEVERAL WEEKS to spare before plunging into his agreed schedule of speaking engagements, Roosevelt decided to go West for his first hunting vacation in two years. But first he was determined to settle once and for all the vexed question of Brooks and McCullagh. Commissioner Parker was still boycotting promotion meetings, and using a variety of other tactics to perpetuate the deadlock. The Mayor’s continued reluctance to announce a verdict on the trial charges (Strong hated confrontations, and feebly hoped that Parker had “learned his lesson”)27 made it imperative that something be done.

On the morning after the Cockran meeting Parker happened to be at Police Headquarters, and Roosevelt promptly announced a special session of the Board “for the purpose of acting on the Inspectorship question.” Hoping to force Parker into at least a statement of his still-secret objections to the two acting inspectors, Andrews called for a vote on their immediate promotion. He, Roosevelt, and Grant voted aye. Parker, instead of voting, began a monologue of ambiguous dissent, whereupon Roosevelt lost his temper. Andrews quit the meeting in disgust, and even Grant showed signs of vague irritation as the two rivals leaped to their feet and began shaking their fists at each other. Eventually Roosevelt, thinking he had made a point, pounded the table and roared, “Case closed!” Although it manifestly was not, he stormed out of the room. “My, how you frighten me!” Parker called after him, then leaned back in his chair, tilted his head to the ceiling, and laughed for a long time.28

The following morning Roosevelt left for North Dakota, clutching in his hand a “new small-bore, smokeless powder Winchester, a 30-166 with a half-jacketed bullet, the front or point of naked lead, the butt plated with hard metal.”29

![]()

DURING THE NEXT THREE WEEKS he grew burly and tanned from sleeping all night in the open and riding all day across the prairie. The Winchester gave him “the greatest satisfaction,” he wrote to Bamie. “Certainly it was as wicked-shooting a weapon as I ever handled, and knocked the bucks over with a sledge-hammer.”30

With his belly full of antelope meat, and the oily perfume of sage in his nostrils, he rejoiced in rediscovering his other self, that almost-forgotten Doppelgänger who haunted the plains while Commissioner Roosevelt patrolled the streets of Manhattan. For thethousandth time he pondered the dynamic interdependence of East and West. No force of nature surely, not even the anarchistic Bryan, with his talk of grass growing in the streets of cities,31 could sunder those two poles, nor for that matter bring them any closer together. American energy lay in their mutual repulsion and mutual attraction. The money men of the East would vote for McKinley, of course. Bryan had already seen he could make no headway there; it was here in the West that the battle between Gold and Silver, Capitalism and Populism, Industry and Agriculture must be fought out.

From talking to his cowboys, and to friends he met in the depot in St. Paul, and to the staff of party headquarters in Chicago, Roosevelt returned to New York on 10 September convinced that “the drift is our way.”32 He serenely articulated his thoughts to anEvening Post reporter: “The battle is going to be decided in our favor because the hundreds and thousands of farmers, workingmen, and merchants all through the West have been making up their minds that the battle should be waged on moral issues … It is in the West that as a nation we shall ultimately work out our highest destiny.”33

![]()

BUT HIS SURGE OF CONFIDENCE did not last long. By mid-September the “battle” initiative was clearly with the Democrats. A campaign map of the United States showed the frightening smallness of McKinley’s constituency (New England, New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, and Ohio) as opposed to the vast spread of states loyal to Bryan (the whole South plus Texas, and all of the mountain states). The Democratic candidate seemed to be everywhere, his big body tireless and his melodious voice unfailing. Republican planners, attempting to plot his every whistle-stop, stippled the Midwest with as many as twenty-four new dots a day; in some areas the concentration was so dense as to shade the paper gray.34 Now the dots were beginning to creep ominously across the Mississippi, into the traditionally Republican plains states, every one of which had been reclassified as doubtful.35

Roosevelt, like Hanna, began to feel pangs of real dread. He was “appalled” at Bryan’s ability “to inflame with bitter rancor towards the well-off those … who, whether through misfortune or through misconduct, have failed in life.”36 Remarks like this suggest that Roosevelt, for all his public attacks upon “the predatory rich,” for all his night-walks through the Lower East Side, was congenitally unable to understand the poor. People who lacked wealth, even through “misfortune,” had “failed in life.”37

Their votes, however, mattered, so he threw himself ardently into the campaign. Taking advantage of some space in Review of Reviews, which he was supposed to fill with an article on the Vice-Presidency, Roosevelt assailed the Populists (Bryan’s third-party backers on the extreme Left) to witty effect:

Refinement and comfort they are apt to consider quite as objectionable as immorality. That a man should change his clothes in the evening, that he should dine at any other hour than noon, impress these good people as being symptoms of depravity instead of merely trivial. A taste for learning and cultivated friends, and a tendency to bathe frequently, cause them the deepest suspicion … Senator Tillman’s brother has been frequently elected to Congress upon the issue that he wore neither an overcoat nor an undershirt.38

This, and a fiery New York speech criticizing the Democratic platform’s bias in favor of unrestricted job action (“It is fitting that with the demand for free silver should go the demand for free riot!”)39 so delighted Republican headquarters that he was sent to barnstorm upstate with Henry Cabot Lodge. In a five-day swing from Utica to Buffalo the two friends spoke to packed, respectful houses, and were encouraged by a general “intent desire to listen to full explanations of the questions at issue.”40

Before returning to New York and Boston they paid a brief call on William McKinley at his home in Canton, Ohio. Here the Republican candidate was conducting a “front-porch” campaign eminently suited to his sedentary personality. Owing to the convenient ill-health of Mrs. McKinley, he had announced early on that he would eschew the stump. “It was arranged, consequently,” writes a contemporary historian, “that inasmuch as McKinley could not go to the people, the people must come to McKinley.”41 The rail-roads, having much to gain by his election, were glad to cooperate with cheap group excursion rates from all over the country. Every day except Sunday several trainloads of party faithful would arrive in Canton and march up North Market Street to the beat of brass bands. Passing under a giant plaster arch adorned with McKinley’s portrait, they would break ranks outside his white frame house and crowd onto the front lawn. The candidate would then appear and listen benignly to a speech of salutation which he had himself edited in advance. In reply, McKinley would read a speech of welcome, then make himself available for handshakes on the porch steps. Occasionally he would invite some favored guests to stay for lunch or dinner.42

It is unlikely that Roosevelt and Lodge were granted this privilege. McKinley could hardly forget that they had supported Reed against him for the Speakership in 1890, and for the Presidential nomination earlier that year. “He was entirely pleasant with us,” Roosevelt reported to Bamie, “though we are not among his favorites.”43

![]()

ROOSEVELT SPENT the first full week of October on the hustings in New York City, expounding the merits of gold to all and sundry, and trying to persuade a rich uncle to lunch with Mark Hanna. He was amused by the old gentleman’s horrified refusal; it was the traditional Knickerbocker disdain for “dirty” politicians.44 Nouveau riche millionaires like James J. Hill and John D. Rockefeller had no such scruples, and the Chairman made the most of their huge contributions. Some 120 million books, pamphlets, posters, and preset newspaper articles poured out of Republican headquarters into all the “doubtful” states, while fourteen hundred speakers, including such luminaries as ex-President Harrison, Speaker Reed, and Carl Schurz, made expense-paid trips into every corner of the country. Masterful, tireless, and increasingly optimistic as this “educational campaign” caught fire, Mark Hanna supervised every itinerary and checked every invoice.45

One of the Chairman’s tactical decisions was to cancel a plan to send Roosevelt into Maryland and West Virginia. Instead, he was put on Bryan’s trail in Illinois, Michigan, and Minnesota during the second and third weeks of the month.46 Hanna obviously believed him to be an ideal foil to the Democratic candidate: an Easterner whom Westerners revered, an intellectual who could explain the complexities of the Gold Standard in terms a cowboy could understand.

Roosevelt more than justified his faith. Oversimplifying brilliantly, as he sped from whistle-stop to whistle-stop, he spoke in parables and brandished an array of homely visual symbols, including gold and silver coins and odd-sized loaves of bread. (“See this big one. This is an eight-cent loaf when the cents count on a gold basis. Now look at this small one … on a silver basis it would sell for over nine cents …”)47 En route he discovered that audiences enjoyed his natural gifts of vituperation as much, if not more, than financial argument, so day by day the pejoratives flowed more freely. He scored his biggest success on 15 October in the Chicago Coliseum, where three months before Bryan had made the famous “cross of gold” speech. An audience of thirteen thousand rejoiced as “Teddy”—the name was all but universal now—went about his familiar business of emasculating the opposition.

It is not merely schoolgirls that have hysterics; very vicious mob-leaders have them at times, and so do well-meaning demagogues when their minds are turned by the applause of men of little intelligence.…48

Warming to this theme, he compared Bryan and various other prominent free silverites and Populists to “the leaders of the Terror of France in mental and moral attitude.” But he added reassuringly that such men lacked the revolutionary power of Marat, Barère, and Robespierre. Bryan, who sought to benefit one class by stealing the wealth of another, wished to negate the Eighth Commandment, while Governor Altgeld of Illinois, having recently pardoned the Haymarket rioters (“those foulest of criminals, the men whose crimes take the form of assassination”), was clearly in violation of the Sixth. Aware that his audience contained a large proportion of college boys, he warned against the seductions of “the visionary social reformer … the being who reads Tolstoy, or, if he possessesless intellect, Bellamy and Henry George, who studies Karl Marx and Proudhon, and believes that at this stage of the world’s progress it is possible to make everyone happy by an immense social revolution, just as other enthusiasts of a similar mental caliber believe in the possibility of constructing a perpetual-motion machine.”49

As always, the harshness of Roosevelt’s words was softened by his beaming fervor, the sophomoric relish with which he pronounced his insults. For two hours he talked on, juggling his coins and loaves, grinning, grimacing, breathing sincerity from every pore, while the son of Abraham Lincoln sat behind him applauding, and the great hall resounded with cheers.50 Next morning the Chicago Tribune awarded him lead status on its front page, and printed his entire seven-thousand-word speech verbatim, running to almost seven full columns of type. “In many respects,” the paper remarked, “it was the most remarkable political gathering of the campaign in this city.”51

There were one or two column-inches of space left over after Roosevelt’s peroration, and into this the editors inserted a filler, reporting an address, elsewhere in the city on the same evening, by an ex-Harvard professor, now head of the Department of Political Economy at the University of Chicago. One wonders with what feelings J. Laurence Laughlin read of the triumph of his former pupil, whom seventeen years before he had advised to go into politics.52

![]()

ON HIS WAY HOME across Michigan, Roosevelt traveled so closely behind the campaign train of William Jennings Bryan that he was able to gauge local reactions to him at first hand.53 In one town he actually caught up with Bryan, and stood incognito in the crowd listening to him speak. Although there was no denying the beauty of the voice, nor the power of the eagle eye and big, confident body, he sensed that the average voter was curious rather than impressed. Bryan, he remarked on returning to New York, represented only “that type of farmer whose gate hangs on one hinge, whose old hat supplies the place of a missing window-pane, and who is more likely to be found at the cross-roads grocery store than behind the plough.”54 Yet in spite of encouraging reports of a McKinley swing in the Midwest, “we cannot help feeling uneasy until the victory is actually won.”55

The last ten days in October saw him hurrying from meeting to meeting in New York, New Jersey, Delaware, and Maryland. In between times he geared the police force to ensure a rigorously honest election. Worn out and apprehensive as 3 November approached, he tried to convince himself that triumph was at hand, that he had done his part to avert “the greatest crisis in our national fate, save only the Civil War.”56

![]()

WILLIAM MCKINLEY was elected President by an overwhelming plurality of 600,000 votes. His electoral college majority was 95; the total amount of votes cast was nearly 14 million. “We have submitted the issue to the American people,” telegraphed William Jennings Bryan, “and their will is law.”57 The Democratic candidate could afford to be magnanimous, having racked up some impressive statistics of his own. He had traveled 18,000 miles, addressed an estimated 5 million people, and was rewarded with the biggest Democratic vote in history.58 When Henry Cabot Lodge wondered if Bryan’s party would hesitate before nominating him again, Mark Hanna had a typically vulgar retort. “Does a dog hesitate for a marriage license?”59

Hanna was now unquestionably the second most powerful man in America,60 and Roosevelt, celebrating with him at a “Capuan” victory luncheon on 10 November, felt a sudden twinge of revulsion at the part money and marketing had played in the campaign. “He has advertised McKinley as if he were a patent medicine!”61 Looking around the room, he realized that at least half the guests were money men. The Chairman might be easy in their company, but he, Roosevelt, was not. “I felt as if I was personally realizing all of Brooks Adams’s gloomy anticipations of our gold-ridden, capitalist-bestridden, usurer-mastered future.”62

But such scruples faded as he basked in the general glow of Republican triumph. McKinley was hailed as “the advance agent of prosperity.” Out of a magically cleared sky, the Gold Dollar shone down, promising fair economic weather for the last four years of the nineteenth century.

Roosevelt felt more hopeful than after any election since that of 1888. Then, as now, his party had swept all three Houses of the federal government, and piled up luxurious pluralities in state legislatures. Then, as now, he had campaigned hard for the Presidentelect, knowing that his efforts would be rewarded. And so he waited with joyful anticipation for news of his appointment as Assistant Secretary of the Navy. It would probably come soon: before November was out, Henry Cabot Lodge and the “dear Storers” traveled separately to Canton to negotiate it.63

![]()

LODGE GOT THERE FIRST, on 29 November, and lunched with McKinley the next day. He reported the conversation to Roosevelt with some delicacy:

He spoke of you with great regard for your character and your services and he would like to have you in Washington. The only question he asked me was this, which I give you: “I hope he has no preconceived plans which he would wish to drive through the moment he got in.” I replied that he need not give himself the slightest uneasiness on that score.…64

Only Cabot Lodge, presumably, could make such an assurance with such a straight face. McKinley took it cordially enough, then changed the subject. Lodge felt cautiously optimistic at the end of the interview, “but after all I’m not one of his old supporters and the person to whom I look now, having shot my own bolt, is Storer.”65

What the latter said to McKinley a day or two later is not of record. It could not have been much, for Storer was understandably more interested in an office for himself. However, his forceful wife, who seems to have already looked beyond the McKinley Administration to some future Roosevelt Administration, was as good as her word. Buttonholing the President-elect after dinner, she pleaded Roosevelt’s cause.

McKinley studied her quizzically. “I want peace,” he said, “and I am told that your friend Theodore—whom I know only slightly—is always getting into rows with everybody. I am afraid he is too pugnacious.”

“Give him a chance,” Mrs. Storer replied, “to prove that he can be peaceful.”66

McKinley received this solicitation as smoothly as he had Lodge’s.67 He had the politician’s gift of sending people away imagining that their requests would be granted, and Mrs. Storer, too, sent an optimistic letter to New York.68 She suggested that Roosevelt now visit McKinley himself, to clinch the appointment. But desperately as he wanted it, pride would not let him:

I don’t wish to go to Canton unless McKinley sends for me. I don’t think there is any need of it. He saw me when I went there during the campaign; and if he thinks I am hot-headed and harum-scarum, I don’t think he will change his mind now … Moreover, I don’t wish to appear as a supplicant, for I am not a supplicant. I feel I could do good work as Assistant Secretary, but if we had proper police laws I could do better work here and would not leave; and somewhere or other I’ll find work to do.69

On 9 December a letter from McKinley arrived on his desk. But it contained nothing more than a polite acknowledgment of the recommendation he had written for Bellamy Storer.70

![]()

“INDEED, I DO NOT THINK the Assistant Secretaryship in the least below what I ought to have,” he wrote fretfully to Lodge.71 His friend had perceived another obstacle in the way of his appointment, and suspected that it, rather than Roosevelt’s belligerency, might be the real reason for McKinley’s hesitation. This was the probable reelection, early in the New Year, of Thomas C. Platt to the United States Senate. If Platt won, he would take his old seat in the Capitol on the same day McKinley entered the White House; and since the Republican majority in the Senate hinged on that very seat, McKinley would not dare to offend the Easy Boss by appointing any New Yorker he disapproved of. Lodge had already asked Platt what he thought about Roosevelt as Assistant Secretary, and gotten a negative reaction. “He did not feel ready to say that he would support you, if you intended to go into the Navy Department and make war on him—or, as he put it, on the organization.”72

It followed, therefore, that if Roosevelt would not ingratiate himself with McKinley, he must ingratiate himself with Platt. One way or another the unhappy Commissioner must eat humble pie. “I shall write Platt at once, to get an appointment to see him,” he replied.73

The meeting was “exceedingly polite,”74 but inconclusive. Platt’s nomination for the Senate would not come up for another month, so there was no question of a premature deal. The old man was also waiting cruelly to see if Roosevelt would give active support to the nomination. His only rival was Joseph H. Choate,75 a distinguished liberal Republican who also happened to be Roosevelt’s oldest political confidant. At Harvard young Theodore had sought Choate’s counsel as a substitute father; Choate had been one of the eminent citizens who backed his first campaign for the Assembly, and had even offered to pay his expenses; after winning, Roosevelt had told Choate, “I feel that I owe both my nomination and my election more to you than to any other one man.”76

Platt did not have to wait long for enlightenment. A day or two later Choate’s aides asked the Police Commissioner to speak for their candidate, and were flatly turned down. On 16 December 1896, when organization men gathered at No. 4 Fifth Avenue to endorse the Easy Boss, Roosevelt was prominently present, and seated at Platt’s table.77

![]()

THE APPROACH OF THE festive season brought deep snow and zero temperatures, cooling the hot flush of politics. Roosevelt retired to Sagamore Hill to chop trees with his children (little Ted, at nine years old, was capable of bringing down a sixty-foot oak, and, though undersized, bore up “wonderfully” during ten-mile tramps). On Christmas Eve the family sleighed down “in patriarchal style” to Cove School, where Roosevelt played Santa Claus and distributed toys to the village children.78

He returned to Mulberry Street on 30 December for the year’s final Board meeting, and found Commissioner Parker as tricky and obstructive as ever. After adjournment Roosevelt was moved to an admission of weary respect: “Parker, I feel to you as Tommy Atkins did toward Fuzzy-Wuzzy in Kipling’s poem … ‘To fight ’im ’arf an hour will last me ’arf a year.’ I’m going out of town tonight, but I suppose we’ll have another row next Wednesday.” Parker laughed. “I’ll be glad to see you when you get back, Roosevelt.”79

![]()

IN THE NEW YEAR, Roosevelt’s longing to be appointed Assistant Secretary was spurred by renewed press criticism of the deadlock at Police Headquarters. Most complaints were directed at Parker, but they also reflected unfavorably on the president of the Board. Editors of all political persuasions agreed that the quarreling between Commissioners was “a discredit” to the department, and “a detriment to public welfare.” It was enough, remarked the Herald, to make citizens nostalgic for the corrupt but superefficient force of yesteryear. “The simple fact is that this much-heralded ‘Reform Board’ has proved a public disappointment and a failure.”80 The Society for the Prevention of Crime, which had strongly supported Roosevelt in the past, condemned the Commissioners for “lack of executive vigor” and “indignity of demeanor,” while the Rev. Charles H. Parkhurst, in a clear reference to Roosevelt’s courtship of Boss Platt, scorned “those who consent, spaniel-like, to lick the hand of their master.”81

Afraid that some of this publicity would reach the ears of the President-elect, Roosevelt announced on 8 January, “I shall hereafter refuse to take part in any wranglings or bickerings on this Board. They are not only unseemly, but detrimental to the discipline of the force.”82 Commissioner Parker affably agreed to do the same, and a measure of peace returned to Mulberry Street.

Thomas Collier Platt was nominated for the Senate on 14 January 1897, by a Republican caucus vote of 147 to 7. His first reaction, on hearing the news, was to ask for a list of the seven Choate supporters and put it in his pocket. This suggests that Roosevelt had been prudent, if nothing else, in deserting Choate the month before.83 Platt was duly elected on 20 January, and immediately became a major, if inscrutable factor in Roosevelt’s campaign for office.

The Police Commissioner, meanwhile, optimistically prepared himself for his future responsibilities, inviting Alfred Thayer Mahan back to Sagamore Hill, addressing the U.S. Naval Academy on 23 January, and working with concentrated speed on a revised version of his Naval War of 1812.84 The manuscript had been commissioned by Sir William Laird Clowes, naval correspondent of the London Times and editor of the official history of the British Navy, then in preparation.85 Roosevelt inserted “a pretty strong plea for a powerful navy” into his text.86

February came and went, with no encouraging news—McKinley was preoccupied with Cabinet appointments and pre-Inaugural arrangements, and Platt remained silent—but Roosevelt continued to hope. “I shall probably take it,” he told Bamie, “because I am intensely interested in our navy, and know a good deal about it, and it would mean four years work.” He did not see himself surviving a year in his present job, even if obliged to remain.87

His truce with “cunning, unscrupulous, shifty”88 Parker lasted less than five weeks, and by the end of February he was complaining of “almost intolerable difficulty” at Mulberry Street.89 Commissioner Grant was now firmly allied with Parker, and Roosevelt paused, in a moment of bitter humor, to wonder how so great a general could have produced so lumpish a son. “Grant is one of the most interesting studies that I know of, from the point of view of atavism. I am sure his brain must reproduce that of some long-lost arboreal ancestor.”90

By 4 March, when William McKinley was inaugurated, the situation at Police Headquarters had become an open scandal. Newspapers that day carried reports of an almost total breakdown of discipline in the force, new outbreaks of corruption, tearful threats of resignation by Chief Conlin, and rabid partisan squabbles between Democratic and Republican officers—echoing those among the four Commissioners, who seemed scarcely able to stand the sight of one another anymore.91

“I am very sorry that I ever appointed Andrew D. Parker,” Mayor Strong commented sadly. “I am just as sorry that it is beyond my power to remove him from office.”92 A reporter pointed out that he had, nevertheless, the power to find Parker guilty of the charges leveled against him last summer. Strong hesitated for two weeks, then at last, on 17 March, dismissed Parker for proven neglect of duty.93 But the sentence was subject to gubernatorial approval; so in the meantime Parker smilingly stayed on.

![]()

DURING THE REST OF MARCH, and on through the first five days of April, a cast of some twenty-five characters lobbied, fought, bartered, bullied, and pleaded for and against Roosevelt’s appointment as Assistant Secretary of the Navy. Lodge acted as coordinator of the pro-Roosevelt group, whose ranks included John Hay, Speaker Reed, Secretary of the Interior Cornelius Bliss, Judge William Howard Taft of Ohio, and even Vice-President Hobart. Mrs. Storer haughtily withdrew when McKinley, who disliked being beholden to anybody, gave her husband the second-rate ambassadorship to Belgium. Mark Hanna was reported favorable to Roosevelt’s nomination immediately after the Inauguration, but was so plagued by other rivals for McKinley’s favor that Lodge hesitated to approach him.94 The Chairman had been seen slinging a pebble at a skunk in a Georgetown garden and growling, “By God, he looks like an office-seeker!”95

Lodge was at a loss to explain the delay in appointing his deserving young friend. “The only, absolutely the only thing I can hear adverse,” he wrote, “is that there is a fear that you will want to fight somebody at once.”96

This, indeed, was the essence of the problem. In all the welter of contradictory reports, rumors, and ambiguous memoirs surrounding the Navy Department negotiations, one rock constantly breaks the surface: McKinley’s belief that once Roosevelt came to Washington he would seek to involve the United States in war. The President wanted nothing so much as four years of peace and stability, so that the corporate interests he represented could continue their growth. He was by nature a small-town son of the Middle West, who shied away from large schemes and foreign entanglements. (The French Ambassador in Washington found him defensively aware of his own provincialism, “ignorant of the wide world.”)97 But as a Civil War veteran, he had a genuine horror of bloodshed. On the eve of his Inauguration he had told Grover Cleveland that if he could avert the “terrible calamity” of war while in office, he would be “the happiest man in the world.” Mark Hanna felt the same. “The United States must not have any damn trouble with anybody.”98

Roosevelt’s response was to send sweet assurances via Lodge to the Secretary of the Navy, that if appointed, he would faithfully execute Administration policies. What was more, “I shall stay in Washington, hot weather or any other weather, whenever he wants me to stay there …”99 No message could have been more shrewdly calculated to appeal to the Secretary, especially the heavy hint about looking after the department in summer. John D. Long, whom Roosevelt knew well from Civil Service Commission days, was a comfortable old Yankee, mildly hypochondriac, who liked nothing so much as to potter around his country home in Hingham Harbor, Massachusetts, and write little books of poetry with titles like At the Fireside and Bites of a Cherry.100 Long had been reported nervous about Roosevelt’s appointment. “If he becomes Assistant Secretary of the Navy he will dominate the Department within six months!” But now he told Lodge that he would be happy to have the young man aboard, and the pressure on McKinley redoubled.101

Senator Platt capitulated in early April, when he was persuaded by his lieutenants that Roosevelt in Washington would be much less of a nuisance to the organization than Roosevelt in New York. The Easy Boss grudgingly told McKinley to go ahead with the appointment, as long as nobody thought that he had suggested it. “He hates Roosevelt like poison,” remarked a Presidential aide.102

And so, on 6 April 1897, Theodore Roosevelt was nominated as Assistant Secretary of the Navy, at a salary of $4,500 a year. Moved almost to tears by the loyalty of his friends, he telegraphed congratulations:

HON. H. C. LODGE, 1765 MASS AVE., WASHINGTON D.C.

SINDBAD HAS EVIDENTLY LANDED THE OLD MAN OF THE SEA

Two days later the Senate confirmed the appointment. Senator Platt was a noticeable absentee from the floor when the vote was called.103

![]()

ANDREW D. PARKER was greatly amused when news of Roosevelt’s imminent departure circulated through Headquarters. “What a glorious retreat!” he exclaimed, and laughed for a long time.104 Contemptuous to the last, he stayed away from Roosevelt’s last Board meeting on Saturday, 17 April. So, too, did Grant, leaving only Avery Andrews to stare across the big table and express polite regrets on behalf of the Police Department. Since there was no quorum, a resolution thanking Roosevelt for his services could not be entered into the minutes. They waited until noon, and then, as Headquarters began to close down for the half-holiday, Roosevelt declared the meeting adjourned. “I am sorry,” he said wistfully. “There were matters of importance which I wished to bring up.” He shook a few hands, then went into his office to pack up his papers.105 Chief Conlin did not come in to say good-bye. Later, when Roosevelt walked down the main corridor for the last time, a guard on duty outside Conlin’s office threw the door open for him. “No,” said Roosevelt, with a gesture of disgust, “I am not going in there.” The guard hesitated. “Well, good-bye, Mr. President.” “Good-bye,” Roosevelt responded, taking his hand. Then, apparently as an afterthought: “I shall be sorry for you when I am gone.”106

![]()

ALTHOUGH THE WORLD CLAIMED, with possible truth, that New Yorkers were pleased to see Roosevelt go,107 few could deny that his record as Commissioner was impressive. “The service he has rendered to the city is second to that of none,” commented The New York Times, “and considering the conditions surrounding it, it is in our judgment unequaled.”108 He had proved that it was possible to enforce an unpopular law, and, by enforcing it, had taught the doctrine of respect for the law. He had given New York City its first honest election in living memory. In less than two years, Roosevelt had depoliticized and deethnicized the force, making it once more a neutral arm of government. He had broken its connections with the underworld, toughened the police-trial system, and largely eliminated corruption in the ranks. The attrition rate of venal officers had tripled during his presidency of the Board, while the hiring of new recruits had quadrupled—in spite of Roosevelt’s decisions to raise physical admission standards above those of the U.S. Army, lower the maximum-age requirement, and apply the rules of Civil Service Reform to written examinations. As a result, the average New York patrolman was now bigger, younger, and smarter.109 He was also much more honest, since badges were no longer for sale, and more soldierlike (the military ideal having been a particular feature of the departing commissioner’s philosophy). Between May 1895 and April 1897, Roosevelt had added sixteen hundred such men to the force.110

Those officers he managed to promote before the deadlock began in March 1896 were, with one or two exceptions, men of good quality. They had brought about such an improvement in discipline that even when morale sank to its low ebb a year later, the force was still operating with a fair degree of efficiency. Crime and vice rates were down; order was being kept throughout the city; and police courtesy—a particular obsession of Roosevelt’s—had noticeably improved. During the reform Board’s administration, he had personally brought about the closure of a hundred of the worst tenement slums seen on his famous night patrols. Patrol-wagon response was quicker; many new station-houses had been built, and other ones modernized; marksmanship scores (thanks to the adoption of the standardized .32 Colt) were climbing; and the “bicycle squad,” first of its kind in the world, was being imitated all over the United States and in Europe.111

Unfortunately Roosevelt’s genius for moral warfare obscured his more practical achievements as Commissioner, both during his tenure and for some time after he left Mulberry Street. An inescapable aura of defeat clouded his resignation.112 He was the first among his colleagues to quit, having served less than one-third of a six-year term. No matter what he said about “an honorable way out of this beastly job,”113 the fact remained that he was leaving a position of supreme responsibility for a subservient one. Perhaps that is why Commissioner Parker found his retreat so funny.

Others found it sad—particularly the stoop-sitters of No. 303, who missed him more and more as life on Mulberry Street returned slowly to normal. The next president of the Police Board, Frank Moss, was an ardent reformer who insisted on continuing Roosevelt’s policies, but his teeth inspired no metaphors, and his ascent of the front steps of Police Headquarters lacked spectator interest. Board meetings were held twice weekly as usual, but with no “boss leader of men” to blow up at Parker’s taunts they were anticlimactic. As the Harper’s Weekly man remarked, the Roosevelt Commissionership “was never in the least dull.” It had been “one long elegant shindy” from the day he took office to the day he resigned.114

Ironically, Parker’s power began to wane in the months following Roosevelt’s departure.115 His partnership with Frederick D. Grant broke up in June, when the latter resigned in order to rejoin the Army, and was replaced by a Commissioner who naturally sided with Moss and Andrews. On 12 July, Governor Frank S. Black denied Mayor Strong’s attempt to oust Parker, saying that the evidence against him was patently “trivial.”116 But this proved a Pyrrhic victory, for the resignation of Chief Conlin on 24 July left Parker without an ally at Headquarters. He was unable to prevent the promotion—at last—of Roosevelt’s protégés, Brooks and McCullagh, along with a large number of other worthy officers whose rise had been blocked beneath them. Inspector McCullagh subsequently became Chief, to Roosevelt’s great delight.117 Mayor Strong did not run for reelection in November. As Boss Richard Croker had predicted, the people grew weary of reform, and voted for a return of the old Democracy. By the end of the year it was business as usual at Tammany Hall.118

![]()

WHAT HAPPENED TO Andrew D. Parker in the years that followed is not known. He vanishes from history as he entered it, a handsome, smiling enigma. The stoop-sitters were never able to agree as to the reason for his poisonous hostility to Theodore Roosevelt. Riis suggested pure “spite,” Steffens the more abstract pleasure of a man who “liked to sit back and pull wires, just to see the puppets jump.”119 Other theories were advanced, of greater and less complexity, but never, it seems, the most fundamental of all: that Parker simply hated Roosevelt and wished to do him ill. Those who loved Roosevelt were so many, and so ardent, that they found it hard to believe that a certain minority always detested him. Parker was of this ilk. He was also, as it happened, the only associate whom Roosevelt never managed to bend to his own will, and, significantly, the only adversary from whom that happy warrior ever ran away.