With his own hand fearless

Steered he the Long Serpent,

Strained the creaking cordage,

Bent each boom and gaff.

![]()

THEODORE ROOSEVELT’S WELLSPRINGS of nostalgia for boyhood and youth tended always to surge and spill in moments of self-fulfillment. So, as he prepared to take office as Assistant Secretary of the Navy on 19 April 1897, memories flooded back of his revered uncle James Bulloch, builder of the Confederate warship Alabama, and of his mother, who used “to talk to me as a little shaver about ships, ships, ships, and fighting of ships, till they sank into the depths of my soul.” Allowing the stream of consciousness to flow unchecked, he recalled how as a Harvard senior he had dreamed of writing The Naval War of 1812: “when the professor thought I ought to be on mathematics and the languages, my mind was running to ships that were fighting each other.”1

The past was still much in his thoughts when he searched for a suitable desk in the Navy Department’s storage room. He selected the massive piece of mahogany used by Assistant Secretary Gustavus Fox, another juvenile hero, during the Civil War. Especiallypleasing, to Roosevelt’s eye, were two beautifully carved monitors which bulged out of each side-panel, trailing rudders and anchors, and a group of wooden cannons protecting the wooden Stars and Stripes, about where his belly would be when he leaned forward to write.2 The desk was dusted and polished and carried up to his freshly painted office. When Roosevelt sat down behind it, he could swivel in his chair and gaze through the window at the White House lawns and gardens—a view equally as good as that enjoyed by the Secretary of the Navy himself.3

“No triumph of peace is quite so great as the supreme triumphs of war.”

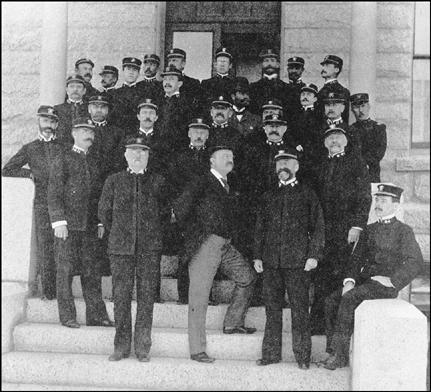

Assistant Secretary of the Navy Roosevelt at the Naval War College, 2 June 1897. (Illustration 22.1)

![]()

“BEST MAN FOR THE JOB,” John D. Long wrote in his diary after his first formal meeting with Roosevelt. Whatever misgivings he may have had about him earlier soon changed to avuncular fondness. The young New Yorker was polite, charming, and seemed to be sincere in promising to be “entirely loyal and subordinate.”4 Long concluded that Roosevelt would be an ideal working partner, amply compensating for his own lack of naval expertise, yet unlikely, on the grounds of immaturity, to usurp full authority.

Certainly the Secretary was everything the Assistant Secretary was not. Small, soft, plump, and white-haired, Long looked and acted like a Dickensian grandfather, although he was in fact only fifty-eight.5 Nobody would want to hurt, or bewilder, such a “perfect dear”—to use Roosevelt’s own affectionate phrase.6 The mild eyes beamed with kindness rather than intelligence, and they clouded quickly with boredom when naval conversation became too technical. Abstruse ordnance specifications and blueprints for dry-dock construction were best left to specialists, in Long’s opinion; he saw no reason to tax his brain unnecessarily.7 Fortunately Roosevelt had a gargantuan appetite for such data, and could safely be entrusted with them. Long was by nature indolent: his gestures were few and tranquil, and there was a slowness in his gait which regular visits to the corn doctor did little to improve. From time to time he would indulge in bursts of hard, efficient work, but always felt the need to “rest up” afterward. On the whole he was content to watch the Department function according to the principles of laissez-faire.8

Roosevelt had no objection to this policy. The less work Long wanted to do, the more power he could arrogate to himself. His own job was so loosely defined by Congress that it could expand to embrace any duties “as may be prescribed by the Secretary of the Navy.” All he had to do was win Long’s confidence, while unobtrusively relieving him of more and more responsibility. By summer, with luck, he would be so much in control that Long might amble off to Massachusetts for a full two months, leaving him to push through his own private plans as Acting Secretary. But no matter how calculating this strategy, there was nothing insincere about Roosevelt’s frequently voiced praises of John D. Long. “My chief … is one of the most high-minded, honorable, and upright gentlemen I have ever had the good fortune to serve under.”9

The American press was largely optimistic about Long and Roosevelt as a team. “Nearly everybody in Washington is glad that Theodore Roosevelt [has come] back to the capital,” reported the Chicago Times-Herald correspondent. “He is by long odds one of the most interesting of the younger men seen here in recent years.” The Washington Post looked forward to lots of hot copy, now the famous headliner was back in town. “Of course he will bring with him … all that machinery of disturbance and upheaval which is as much a part of his entourage as the very air he breathes, but who knows that the [Navy Department] will not be the better for a little dislocation and readjustment?”10

Overseas newspapers, such as the London Times, took rather less pleasure in the “menacing” prospect of Roosevelt influencing America’s naval policy. With Cuba and Hawaii ripe for conquest and annexation, “what now seems ominous is his extreme jingoism.”11

Roosevelt knew that President McKinley and Chairman (now Senator) Hanna shared this nervousness, and he was at pains to reassure them, as well as Long, that he intended to be a quiet, obedient servant of the Administration. “I am sedate now,” he laughingly told a Tribune reporter. All the same he could not resist inserting four separate warnings of possible “trouble with Cuba” into a memorandum on fleet preparedness requested by President McKinley on 26 April. The document, which was written and delivered that same day, could not otherwise be faulted for its effortless sorting out of disparate facts of marine dynamics, repair and maintenance schedules, geography and current affairs. Roosevelt had been at his desk for just one week.12

“He is one hell of a Secretary,” Congressman W. I. Guffin remarked to Senator Shelby Cullom, unconsciously dropping the qualifier in Roosevelt’s title.13

![]()

SEDATE AS HIS OFFICIAL image may have been in the early spring of 1897, his private activities more than justified foreign dread of his appointment. Quickly, efficiently, and unobtrusively, he established himself as the Administration’s most ardent expansionist. A new spirit of intrigue affected his behavior, quite at odds with his usual policy of operating “in the full glare of public opinion.” Never more than a casual clubman, he began to lunch and dine almost daily at the Metropolitan Club, assembling within its exclusive confines a coterie much more influential than the old Hay-Adams circle, now broken up.14 It consisted of Senators and Representatives, Navy and Army officers, writers, socialites, lawyers, and scientists—men linked as much by Roosevelt’s motley personality as by their common political belief, namely, that Manifest Destiny called for the United States to free Cuba, annex Hawaii, and raise the American flag supreme over the Western Hemisphere.

This expansionist lobby was not entirely Roosevelt’s creation. Its original members had begun to work together in the last months of the Harrison Administration, as America’s last frontier fell and Hawaii simultaneously floated into the national consciousness. But their organization had remained loose, and their foreign policy uncoordinated, all through the Cleveland Administration, partly due to the President’s own ambivalent attitudes to Hawaii on the one hand and Venezuela on the other. Not until William McKinley took office, amid reports of Japanese ambitions in the Pacific and increased Spanish repression in the Caribbean, did the expansionists begin to close ranks, and cast about for a natural leader.15

Whether they chose to follow Roosevelt, or Roosevelt chose to lead them, is a Tolstoyan question of no great consequence given the group’s unanimity of purpose. Examples of how he used Captain Alfred Thayer Mahan and Commodore George Dewey to advance his own interest, while also advancing their own, merit separate consideration. Other members of the lobby included Senators Henry Cabot Lodge, William E. Chandler, W. P. Frye, and “Don” Cameron, all powers on the Hill; Commander Charles H. Davis, Chief of Naval Intelligence; the philosopher Brooks Adams, shyer, more intense, and to some minds more brilliant than his older brother, Henry; Clarence King, whose desire to liberate Cuba was not lessened by his lust for mulatto women; and jolly Judge William H. Taft of the Sixth Circuit, the most popular man in town. Charles A. Dana, editor of the Sun, and John Hay, now Ambassador to the Court of St. James, represented the Roosevelt point of view in New York and London.16 Many other men of more or less consequence cooperated with these in the effort to make America a world power before the turn of the century, and they looked increasingly to Theodore Roosevelt for inspiration as 1897 wore on.17

![]()

THE ASSISTANT SECRETARY of the Navy worked quietly and unobtrusively for over seven weeks before making his first public address, at the Naval War College in Newport, Rhode Island, on 2 June.18 It turned out to be the first great speech of his career, a fanfare call to arms which echoed all the more resoundingly for the pause that had preceded it. He chose as his theme a maxim by George Washington: “To be prepared for war is the most effectual means to promote peace.” This, to Roosevelt’s mind, could signify only one thing in 1897: an immediate, rapid buildup of the American Navy.

He dismissed the suggestion that such a program would tempt the United States into unnecessary war. On the contrary, it would promote peace, by keeping foreign navies out of the Western Hemisphere. Should any power be so foolhardy as to attempt invasion, why, that would mean necessary war, which was a fine and healthy thing. “All the great masterful races have been fighting races; and the minute that a race loses the hard fighting virtues, then … it has lost its proud right to stand as the equal of the best.” Roosevelt did not have to remind his listeners that the Japanese, fresh from last year’s victory over the Chinese, were in full possession of those virtues, and were even now patrolling Hawaiian waters with an armored cruiser.19 “Cowardice in a race, as in an individual,” he declared, “is the unpardonable sin.” During the last two years alone, various “timid” European rulers had ignored the massacre of millions of Armenians by the Turks in order to preserve “peace” in their own lands. Again, Roosevelt did not have to mention Cuba, where Spain’s infamous Governor-General Weyler was currently slaughtering the insurrectos, to make a point. “Better a thousand times err on the side of over-readiness to fight, than to err on the side of tame submission to injury, or cold-blooded indifference to the misery of the oppressed.”

Intoxicated with his theme, Roosevelt continued:

No triumph of peace is quite so great as the supreme triumphs of war … It may be that at some time in the dim future of the race the need for war will vanish; but that time is yet ages distant. As yet no nation can hold its place in the world, or can do any work really worth doing, unless it stands ready to guard its rights with an armed hand.20

Aware that his audience consisted largely of naval academics devoted to the theory, rather than the practice, of war, Roosevelt praised teachers, scientists, writers, and artists as vital members of a civilized society, but warned against the dangers of too much “doctrinaire” thinking in formulating national policy. “There are educated men in whom education merely serves to soften the fiber.” Only those “who have dared greatly in war, or the work which is akin to war,” deserved the best of their country.

By now the Assistant Secretary was using the word “war” approximately once a minute. He was to repeat it sixty-two times before he sat down.

Roosevelt cited fact after historical fact to prove that “it is too late to prepare for war when the time for peace has passed.” He poured scorn on Jefferson for seeking to “protect” the American coastline with small defensive gunboats, instead of building a fleet of aggressive battleships which might have prevented the War of 1812. He pointed out that the nation’s present vulnerability, with Britain, Germany, Japan, and Spain engaged in a naval arms race, was more alarming than it had been at the beginning of the century. Then, at least, a man-of-war could be built in a matter of weeks; now, naval technology was so complicated that no battleship could be finished inside two years. Cruisers took almost as long; even the light, lethal, torpedo-boat (which he had already made a special priority item in the department)21 needed ninety days to put into first-class shape. As for munitions, America’s current supply was so meager, and so obsolete, that if war broke out tomorrow “we should have to build, not merely the weapons we need, but the plant with which to make them in any large quantity.”

Roosevelt chillingly demonstrated that it would be six months before the United States could parry any sudden attack, and a further eighteen months before she could “begin” to return it. “Since the change in military conditions in modern times, there has never been an instance in which a war between two nations has lasted more than about two years. In most recent wars the operations of the first ninety days have decided the results of the conflict.” It was essential, therefore, that Congress move at once to build more ships and bigger ships, “whose business it is to fight and not to run.” Line personnel must be subjected to the highest standards of recruitment and training, while staff officers “must have as perfect weapons ready to their hands as can be found in the civilized world.” This new Navy would be more to America’s international advantage than the most brilliant corps of ambassadors. “Diplomacy,” Roosevelt insisted, “is utterly useless when there is no force behind it; the diplomat is the servant, not the master of the soldier.”22

Moving into his peroration, he anticipated another great war speech by forty-three years in a eulogy to “the blood and sweat and tears” which heroes must sacrifice for the cause of freedom. He begged his audience to remember that

there are higher things in this life than the soft and easy enjoyment of material comfort. It is through strife, or the readiness for strife, that a nation must win greatness. We ask for a great navy, partly because we feel that no national life is worth having if the nation is not willing, when the need shall arise, to stake everything on the supreme arbitrament of war, and to pour out its blood, its treasure, and its tears like water, rather than submit to the loss of honor and renown.

![]()

ROOSEVELT’S SPEECH WAS PRINTED in full in all major newspapers and caused a nationwide sensation. From Boston to San Francisco, from Chicago to New Orleans, expansionist editors and correspondents praised it, and agreed that a new, defiantly original spirit had entered into the conduct of American affairs.23 “Well done, nobly spoken!” exclaimed the Washington Post. “Theodore Roosevelt, you have found your place at last!” The Sun called his words “manly, patriotic, intelligent, and convincing.” TheHeraldrecommended that readers study this “lofty” speech “from its opening sentence to its close,” while the New Orleans Daily Picayune said that it “undoubtedly voices the sentiments of the great majority of thinking people.” Even such anti-expansionist journals asHarper’s Weekly found the address “very eloquent and forcible,” although the commentator, Carl Schurz, logically demolished Roosevelt’s main argument. If too much peace led to softening of the national fiber, Schurz argued, and war led to vigor and love of country, it followed that prevention of war would only be debilitating. “Ergo, the building up of a great war fleet will effect that which promotes effeminacy and languishing unpatriotism.”24

Schurz should have left his syllogism there, for it was unanswerable, but he went on to argue dreamily that the United States was so protected by foreign balances of power that no nation dare attack it. This made him sound like one of the naive doctrinaires Roosevelt had criticized in his speech, and served only to justify the Assistant Secretary’s warnings. “I suspect that Roosevelt is right,” President McKinley sighed to Lemuel Ely Quigg, “and the only difference between him and me is that mine is the greater responsibility.”25

This startling admission by a Chief Executive personally committed to a policy of non-aggression suggests that Roosevelt had more than mere headlines in mind when he spoke to the Naval War College that June afternoon.26 His words were obviously intended to create, rather than just influence, national foreign policy. In both timing and targeting, the speech was accurate as a karate chop, for Hawaii and Cuba were the issues of the hour, and the Naval War College was the nerve center of American strategic planning.27The isolationists in the Cabinet never quite recovered from Roosevelt’s blow, and its shock effects were felt in every extremity of the Administration.

Traditionally, the Naval War College had been founded to give officers advanced instruction in science and history of marine warfare. But during the course of nearly a decade of domination by Alfred Thayer Mahan, it had also become the prime source of war plans for the government.28 These documents, drawn up by brilliant young Mahanites ambitious to thrust the American Navy into the twentieth century, were submitted for consideration by the Office of Naval Intelligence in Washington, whence they went to the Secretary of the Navy for approval or rejection. Under the conservative Administration of President Cleveland, the Office of Naval Intelligence had acted as a foil to the Naval War College, toning down its more strident proposals, and Secretary Herbert saw to it that such war plans were pigeonholed before they had any effect on national defense policy. Herbert, indeed, was so suspicious of the War College that he had organized a senior board, consisting mainly of Old Guard officers, to keep both it and the Office of Naval Intelligence safely under control.29

With the accession of President McKinley, however, the composition of the Board changed radically. A few days after Roosevelt’s arrival in the Navy Department, it was ordered to exhume two of the most recent war plans and to produce a new strategy in the light of recent developments in the Pacific and Caribbean. Captain Caspar F. Goodrich, president of the Naval War College, was just beginning to work on this document when Roosevelt chose to deliver his bellicose address to the Staff and Class of ’97. There could not possibly have been a stronger hint as to what kind of thinking the new war plan should contain. Roosevelt had, in fact, already sent Captain Goodrich a “Special Confidential Problem” for academic deliberation:

Japan makes demands on Hawaiian Islands.

This country intervenes.

What force will be necessary to uphold the intervention, and how should it be employed?

Keeping in mind possible complications with another Power on the Atlantic Coast (Cuba).30

Such a problem would never exist, he privately informed Captain Mahan, “if I had my way.” In an undisguised fantasy of himself as Commander-in-Chief, Roosevelt continued that he “would annex those islands tomorrow. If that was impossible I would establish a protectorate over them. I believe we should build the Nicaraguan Canal at once, and in the meantime that we should build a dozen new battleships, half of them on the Pacific Coast.… I would send the Oregon and, if necessary, also the Monterey … to Hawaii, and would hoist our flag over the island, leaving all details for after action.” He acknowledged that there were “big problems” in the West Indies, but until Spain was turned out of Cuba (“and if I had my way,” he repeated, “that would be done tomorrow”), the United States would always be plagued by trouble there. “We should acquire the Danish Islands.… I do not fear England; Canada is hostage for her good behavior …”

In the midst of his flow of dictation, recorded at the Navy Department, Roosevelt seems to have noticed that his stenographer’s neck was flushing. “I need not say,” he hastily went on, “that this letter must be strictly private … to no one else excepting Lodge do I speak like this.”31

It would appear, nevertheless, that he expressed himself almost as strongly to Assistant Secretary of State William R. Day, at least on the subject of Hawaii. So, too, did Lodge and other members of the expansionist lobby. Bypassing Day’s senile superior, John Sherman, they persuaded President McKinley to approve a treaty of annexation on 16 June 1897.32 The treaty was forwarded to the Senate, where Lodge triumphantly undertook to secure its ratification, and Roosevelt rejoiced. It is fair to assume that champagne was drunk in the Metropolitan Club that evening. At last America had joined the other great powers of the world in the race for empire.33

![]()

THE NEXT MORNING Secretary Long, who was beginning to feel the heat of approaching summer, left town for two weeks’ vacation, preparatory to taking his main vacation. Roosevelt was relieved to be alone for a while, since the Secretary had not been at all pleased with his War College speech,34 and was already resisting pleas for a buildup of the Navy. Beneath the kindly exterior he sensed an old man’s obstinacy which gave him “the most profound concern.” It would hardly do to have the pace of naval construction slow just as the expansion movement was accelerating. “I feel that you ought to write to him,” Roosevelt told Mahan, “—not immediately, but some time not far in the future, explaining to him the vital need for more battleships.… Make the plea that this is a measure of peace and not war.”35

Roosevelt’s easy recourse to the world’s ranking naval authority, now and on many subsequent occasions in his career as Assistant Secretary, makes it worthwhile to examine their complex relationship or, more accurately, reexamine it, in the light of the enduring belief that the younger man’s naval philosophy was inherited from the older. Facts recently uncovered suggest the reverse.36 In 1881, when the twenty-two-year-old Roosevelt sat writing The Naval War of 1812 in New York’s Astor Library, Mahan had been an obscure, forty-year-old career officer of no particular accomplishment, literary or otherwise. He did not publish his own first book, a workmanlike history of Gulf operations in the Civil War, until two years later, by which time Roosevelt’s prodigiously detailed volume was required reading on all U.S. Navy vessels, and had exerted at least a peripheral influence on the decision of Congress to build a fleet of modern warships. Mahan, indeed, was still so unlettered in world naval history that in 1884, when offered an instructorship at the new Naval War College, he asked for a year’s leave to study for it. Most of 1885 was spent in the Astor Library, reading the same tomes Roosevelt had already devoured. This research was the basis of Mahan’s lecture course at the War College, which in turn became The Influence of Sea Power upon History (1890).37 Long before this masterpiece appeared, however, he had familiarized himself with Roosevelt’s theories, to the extent of discussing them with him personally. At least one of the other instructors at the War College, Professor J. Russell Soley, was an enthusiastic Rooseveltian; so, too, was the institution’s founder, Admiral Stephen B. Luce. “Your book must be our textbook,” Luce told the young author.38

Roosevelt’s next two histories, Gouverneur Morris and Thomas Hart Benton, were replete with arguments for a strong Navy and mercantile marine, while The Winning of the West propounded visions of Anglo-Saxon world conquest as heady as anything Mahan ever wrote. All of these works predated The Influence of Sea Power upon History.

The relative academic prestige of Roosevelt and Mahan altered drastically in the latter’s favor after Sea Power came out. As has been seen, Roosevelt enthusiastically welcomed the book, reviewing it—and all Mahan’s subsequent volumes—with a generosity that could not fail to endear him to the austere, reclusive scholar.39 During his early years in Washington, he worked to save Mahan from sea duty (which the captain detested) and to increase his backing in government circles.40

It is not surprising, therefore, that when the new Assistant Secretary sought to advance his own ambitions in the spring of 1897, he could call upon Mahan in confidence. The fact that their naval philosophies were identical at this point only increased the willingness of one man to help the other.41

![]()

FINDING HIMSELF IN full, if temporary control of the Navy Department, Roosevelt worked energetically but cautiously, not wanting to jeopardize his chances of being Acting Secretary through most of the summer. He signed with pleasure a letter of permission for general maneuvers by the North Atlantic Squadron in August or September, and told its commanding officer that he would “particularly like to be aboard for a day or two” during gun practice.42 He continued to dig up Secretary Herbert’s suppressed reports, on the grounds that those most deeply buried might yield the most interesting information,43 ordered an investigation of the management of the Brooklyn Navy Yard,44 and proposed that some of the great names in American naval history be revived on future warships. He suggested the installation of rapid-fire weaponry throughout the fleet. Horrified when an elderly, bureaucratic admiral boasted about being able to account for every single bottle of red and black ink supplied to ships around the world, Roosevelt initiated a massive campaign to reduce the department’s paperwork. Soothingly, he wrote to Long, “There isn’t the slightest necessity of your returning.”45

Undismayed by strong Japanese protest regarding the Hawaii treaty, Roosevelt set his expansionist lobby to work on the subject of Cuba, “this hideous welter of misery on our doorsteps.” On 18 June he invited several key Senators to dine at the Metropolitan Club with an envoy recently returned from the island.46

Elsewhere on the propaganda front, he played off two publishers—Harpers and G. P. Putnam’s Sons—in competition for a volume of “politico-social” essays covering the whole of his career as a speaker and man of letters. Articles on “The Manly Virtues” and “True Americanism” were prominent among them, along with his most ambitious reviews, “National Life and Character,” “Social Evolution,” and “The Law of Civilization and Decay.” For good measure he added his recent address to the Naval War College. “I am rather pleased with them myself,” he told Putnam’s, the successful bidder.47 Less robust tastes were repelled by a cumulative impression of jingoism, militarism, and self-righteousness, when the essays came out under the title American Ideals.48 “If there is one thing more than another for which I admire you, Theodore,” said Thomas B. Reed, “it is your original discovery of the Ten Commandments.”49

Henry James, reviewing the volume for a British periodical, expressed mock alarm. “Mr. Theodore Roosevelt appears to propose … to tighten the screws of the national consciousness as they have never been tightened before.… It is ‘purely as an American,’ he constantly reminds us, that each of us must live and breathe. Breathing, indeed, is a trifle; it is purely as Americans that we must think, and all that is wanting to the author’s demonstration is that he shall give us a receipt for the process.” James granted thatRoosevelt had “a happy touch” when he eschewed questions of doctrine for accounts of his own political experiences. “These pages give an impression of high competence.… But his value is impaired for intelligible precept by the puerility of his simplifications.”50

Such criticism, of course, was only to be expected from “white-livered” expatriates, and Roosevelt took no notice of James’s remarks, if he even bothered to read them. From now on he would pour out a swelling flood of patriotic speeches and articles, aided by such other expansionists as Mahan, Brooks Adams, and Albert Shaw, until the last remaining dikes of isolationism burst under the pressure.51

![]()

THE NAVY DEPARTMENT’S new war plan was ready on 30 June, three days before Secretary Long returned from vacation. Roosevelt had no authority to approve it, but it was a document that gladdened his eyes nevertheless. All the more aggressive features of the earlier plans had been restored, and the weaker ones eliminated; in addition there were some new, flagrantly expansionist proposals which proved prophetic to a degree.52

In brief, the plan postulated a war with Spain for the liberation of Cuba. Hostilities would take place mainly in the Caribbean, but the U.S. Navy would also attack the Philippines, and even the Mediterranean shores of Europe, if necessary. The Caribbean strategy called for a naval blockade of Cuba, combined with invasion by a small Army force. No permanent occupation of Cuba was suggested, but the plan proceeded to discuss the Philippines, in tones hardly calculated to reassure Republican Conservatives: “we could probably have a controlling voice, as to what should become of the islands when a final settlement [with Filipino rebels] was made.”53

![]()

ROOSEVELT’S METROPOLITAN CLUB CIRCLE widened in the early days of summer to include two new associates—Captain Leonard Wood, the President’s Assistant Attending Surgeon, and Commodore George Dewey, president of the Board of Inspection and Survey. He met the former at a dinner party early in June.54 When he met the latter is not known, but the name “Dewey” appears in his correspondence for the first time on 28 June.55 Both men were to play major roles in his life, and he in theirs.

Wood was a doctor by profession and a soldier by choice; he excelled in both capacities. His looks were noble, his physical presence splendid as a Viking’s.56 Tall, fair, lithe, and powerfully muscled, he walked with the slightly pigeon-toed stride of a born athlete, and was forever compulsively kicking a football around an empty lot, the leather thudding nearly flat as he drove it against the wall.

Roosevelt, who as Civil Service Commissioner had won fame as the most strenuous pedestrian in Washington,57 was impressed to discover that this newcomer could outpace and outclimb him with no signs of fatigue. “He walked me off my legs,” the Assistant Secretary told Lodge, with some surprise.58 Ever the boy, he hero-worshiped Wood (although the doctor was two years his junior) as a fighter of Apaches and a vanquisher of Geronimo. Wood’s personality was clear, forceful, honest, and unassuming. Best of all, he was an ardent expansionist, and could not stop talking about Cuba as a wound on the national conscience. Roosevelt decided that this quiet, charming man with excellent military connections (Wood was married to the niece of U.S. Army Commanding General Nelson A. Miles) must needs be cultivated.

Little old Commodore Dewey was a total contrast.59 Nut-brown, wiry, and vain, he was in his sixtieth year when Roosevelt befriended him, but the size of his personal ambition was in inverse proportion to his age and height. Over three decades of undistinguished peacetime service had not quenched his lust for battle, kindled as a lieutenant under Farragut in the Civil War. Now, with retirement only three years off, Dewey was forced to accept the fact that glory might never be his.60 Yet the Commodore still bore himself with fierce pride, immaculate in tailored uniform and polished, high-instepped boots. He was without doubt the smartest dresser in the Navy. “It was said of him,” wrote one reporter, “that the creases of his trousers were as well-defined as his views on naval warfare.”61 With his beaky nose and restless, caged strut, Dewey looked like a resplendent killer falcon, ready to bite through wire, if necessary, to get at a likely prey.

The Commodore had attracted Roosevelt’s admiring attention as long ago as the Chilean crisis of 1891, when he voluntarily bought coal for his ship instead of waiting for official battle orders.62 Any officer whose instinct was to stoke up before a crisis—at his own expense—could be trusted in wartime. Like Wood, Dewey was a dedicated expansionist,63 lunching and dining daily at the Metropolitan Club; like Wood, he was a man of action rather than thought. Roosevelt began to muse ways of giving him command of the Asiatic Squadron when Rear-Admiral Fred V. McNair retired later in the year.64

In the meantime, their friendship ripened. Often, on a sunny afternoon after work, they could be seen riding in Rock Creek Park together.65

![]()

AT THE BEGINNING OF JULY it was the Assistant Secretary’s turn to take a brief vacation. He headed north for a reunion with Edith—pregnant, now, with his sixth child. Distracted as he was with naval affairs and plans for the coming war (whose certainty he never questioned), Roosevelt allowed himself ten days of quiet domesticity at Oyster Bay. The white marble city on the Potomac was all very well, he told Bamie, but “permanently, nothing could be lovelier than Sagamore.”66

And nothing could be more satisfying than to see his own progeny growing sturdy and sunburned in his own fields. Roosevelt confessed to Cecil Spring Rice that “the diminishing rate of increase” in America’s population worried him in contrast to the fecundity of the Slav. Looking around Sagamore Hill, he gave thanks that his own family, at least, had shown valor in “the warfare of the cradle.” With various cousins who had come to stay, there were “sixteen small Roosevelts” in his house.67 Edith, watching him crawling through tunnels in the hay-barn in pursuit of squealing boys and girls, was inclined to put the number one higher.

The eldest cousin was a good-looking lad of fifteen from Groton, named Franklin. He had been invited to Oyster Bay earlier in the year, after a lecture by Roosevelt to his schoolmates on life as a Police Commissioner of New York City. The talk, which kept the boys in stitches of laughter, impressed young Franklin as “splendid.” From this summer on he deliberately modeled his career on that of “Cousin Theodore,” whom he would always describe as the greatest man he ever knew.68

On 11 July, Roosevelt enjoyed one of the privileges of his new job by cruising from Oyster Bay to Newport in a torpedo-boat.69 The swiftness and responsiveness of the little vessel delighted him. “Like riding a high-mettled horse,” he wrote. He did not, like some critics, find its thin-shelled vulnerability a tactical disadvantage: “with these torpedo boats … frailty is part of the very essence of their being.”70 Such comments suggest that Roosevelt was not altogether a landlubber, although in general he did prefer the abstract flow of arrows on paper to the heaving, splashing realities of naval movement.

After witnessing some trials at Newport he set off for a tour of the Great Lakes Naval Militia stations in Mackinac, Detroit, Chicago, and Sandusky.71 His speech to the latter establishment, on 23 July, contained a violent reply to Japan’s protest against the annexation of Hawaii. “The United States,” Roosevelt thundered, “is not in a position which requires her to ask Japan, or any other foreign Power, what territory it shall or shall not acquire.” The Tribune called his outburst a “distinct impropriety” and suggested that he “leave to the Department of State the declaration of the foreign policy of this government.”72

John D. Long, who was a man of delicate nervous constitution,73 had barely recovered from his subordinate’s previous speech to the Naval War College before the news from Sandusky came in. “The headlines … nearly threw the Secretary into a fit,” Roosevelt told Lodge, “and he gave me as heavy a wigging as his invariable courtesy and kindness would permit.”74

Abject apologies smoothed the incident over, but Long must have had some scruples about putting Roosevelt in charge of the Department through Labor Day as planned. However the need to resume his vacation was paramount, and on 2 August, Roosevelt found himself installed as “the hot weather Secretary.”75

![]()

HE NOW ENTERED UPON one of those periods of near-incredible industry which always characterized his assumption of new responsibility—whether it be the management of a ranch, the researching of a book, or, as in this case, the administration of the most difficult department in the United States Government.76 Quite apart from its complex structure, with seven bureaus issuing streams of documents on such subjects as naval law, steam engineering, diplomacy, finance, strategy, education, science, astronomy, and hydrography, there was the huge extra dimension of the Navy itself—a proud, hierarchical institution, traditionally resistant to change and contemptuous of civilian authority.77 The multiple task of reconciling the various bureaus with one another, and the department with the fleet, while simultaneously dealing with Congress, the White House, the press, and countless industrial contractors was enough to frustrate anybody but a Roosevelt. “I perfectly revel in this work,” he exulted to Long. For the first time in his life he had real power in full measure. As Acting Secretary he was answerable only to his chief and President McKinley, both of whom were away from town for at least six weeks. Praying that the latter would come back a few days before the former—since he wished to have a private talk with him—Roosevelt abandoned himself to the drug of hyperactivity. “I am having immense fun running the Navy,” he told Bellamy Storer on 19 August.78

His industry during that first month confirms Henry Adams’s remark, “Theodore Roosevelt … was pure act.”79 In just twenty-two days of official duty he managed to write a report of his tour of the Naval Militia; inspect a fleet of first- and second-class battleships off Sandy Hook; expedite a stalled order for diagonal-armor supplies; devise a public-relations plan for press coverage of the forthcoming North Atlantic Squadron exercises; set up a board to investigate ways of relieving the chronic dry-dock shortage; introduce a new post-tradership system; weigh and pronounce verdict upon the Brooklyn Navy Yard probe; surreptitiously backdate a Bureau of Navigation employment form in order to favor a protégé of Senator Cushman Davis; extend his anti-red-tape reforms to cover battleships and cruisers; eliminate the department’s backlog of unfilled appointments; draw up an elaborate cruising schedule for the new torpedo-boat flotilla; settle a row between the Bureaus of Ordnance and Construction; review the relative work programs in various navy yards; draft a naval personnel reform bill, and fire all Navy Department employees who rated a sub-70 mark in the semiannual fitness reports—all the while making regular reports to the vacationing Secretary, in tones calculated both to soothe and flatter. “I shan’t send you anything, unless it is really important,” Roosevelt wrote. “You must be tired, and you ought to have an entire rest.” He begged Long not to answer his letters, “for I don’t want you bothered at all.” As for coming back after Labor Day, there was “not the slightest earthly reason” to return before the end of September.80

Long, happily pottering about his garden, was more than content to remain away.81 Ensconced as he was in rural Massachusetts, he probably did not see a lengthy analysis, in the New York Sun of 23 August, of European reaction to the expansionist movement in the United States. One paragraph read:

The liveliest spot in Washington at present is the Navy Department. The decks are cleared for action. Acting Secretary Roosevelt, in the absence of Governor Long, has the whole Navy bordering on a war footing. It remains only to sand down the decks and pipe to quarters for action.

“Yes, indeed,” Roosevelt was writing, “I wish I could be with you for just a little while and see the lovely hill farm to which your grandfather came over ninety years ago.… Now, stay there just exactly as long as you want to.”82

![]()

IN HIS “SPARE HOURS,” as he put it, Roosevelt amused himself by writing and editing another volume of Boone & Crockett Club big-game lore, dictating one of his enormous, prophetic letters to Cecil Spring Rice (“If Russia chooses to develop purely on her own line and resist the growth of liberalism … she will sometime experience a red terror that will make the French Revolution pale”),83 and assembling a series of quotations by various Presidents on the subject of an aggressive Navy. As he read his anthology through, it struck him as a powerful piece of propaganda, and he determined to publish it, after first mailing the text to Long for approval.84

The Secretary saw no harm in it, providing that Roosevelt inserted the words “in my opinion” somewhere in the Introduction, to show that it was not an official statement of policy by the Navy Department.85 An advance copy was sent to President McKinley on 30 August, and in early September the Government Printing Office issued it under the title The Naval Policy of America as Outlined in Messages of the Presidents of the United States from the Beginning to the Present Day.86 It drew admiring comment in most newspapers, “timely” being the adjective most frequently used. Besides being a miniature history of the U.S. Navy, the pamphlet showed a striking similarity of thought between Presidents Washington, Jackson, Lincoln, and Grant on the one hand, and Assistant Secretary of the Navy Roosevelt on the other. No quotations by Thomas Jefferson were deemed worthy of inclusion.87

![]()

ABOUT THIS TIME Roosevelt added yet another influential voice to his expansionist propaganda machine.88 William Allen White was not yet thirty, but he was proprietor and editor of a powerful Midwestern newspaper, the Emporia Gazette, and had won a national following in 1896 with a diatribe against the Populists, “What’s the Matter with Kansas?” Printed first as an editorial in his own paper, then reprinted and distributed in millions of copies by Mark Hanna, the piece had been the single most effective broadsheet of McKinley’s campaign.89 Roosevelt had read the famous editorial with interest. Here was the natural Republican antidote to William Jennings Bryan, and a much better metaphorist to boot. If he could take White in hand and teach him the gospel of expansionism, he would enlarge his own sphere of influence by thousands of readers and thousands of square miles. Roosevelt did not care who propounded Rooseveltian views, even if they won glory by doing so: what mattered was that the message got through. When he heard that White was in Washington on a patronage mission, he asked for him to be sent down to the Navy Department.90

Blond, red-faced, and pudgy, White looked the typical corn-fed “hick” journalist, yet his intelligence was acute, and his language rich and rolling as the Midwest itself. Their meeting was casual—little more than a handshake and an agreement to have lunch next day—but Roosevelt was so radiant with newfound power that White was unable to sit down for excitement afterward. “I was afire with the splendor of the personality that I had met.”91

The little Kansan was still “stepping on air” the following afternoon, when Roosevelt escorted him to the Metropolitan Club and signaled for the menu.92 Both men were compulsive eaters and compulsive talkers, and for the next hour they awarded each other equal time, greed alternating with rhetoric. In old age White fondly recalled “double mutton chops … seas of speculation … excursions of delight, into books and men and manners, poetry and philosophy.”93

Roosevelt spoke with shocking frankness about the leaders of the government, expressing “scorn” for McKinley and “disgust” for the “deep and damnable alliance between business and politics” that Mark Hanna was constructing. White, whose worship of the Gold Dollar amounted to religion, flinched at this blasphemy, yet within another hour he was converted:

I have never known such a man as he, and never shall again. He overcame me … he poured into my heart such visions, such ideals, such hopes, such a new attitude toward life and patriotism and the meaning of things, as I never dreamed men had … So strong was this young Roosevelt—hard-muscled, hard-voiced even when the voice cracked infalsetto, with hard, wriggling jaw muscles, and snapping teeth, even when he cackled in raucous glee, so completely did the personality of this man overcome me that I made no protest and accepted his dictum as my creed.94

Later they strolled for a while under the elms of F Street, and when they parted “I was his man.” Years later White tried to analyze the elements of Roosevelt’s conquering ability. It was not social superiority, he decided, nor political eminence, nor erudition; it was something vaguer and more spiritual, “the undefinable equation of his identity, body, mind, emotion, the soul of him … It was youth and the new order calling youth away from the old order. It was the inexorable coming of change into life, the passing of the old into the new.”95

![]()

WHEN ACTING SECRETARY Roosevelt boarded the battleship Iowa on Tuesday, 7 September, the Virginia Capes had long since slipped below the horizon.96 Apart from a forlorn speck of color floating some twenty-five-hundred yards off—the target for today’s gunnery exercises—the world consisted of little but blue sky and glassy water, in which seven white ships of the North Atlantic Squadron sat with the solidity of buildings. Biggest and most sophisticated by far was the eleven-thousand-ton Iowa, a masterpiece of naval engineering, and the equal of any German or British battleship. She was so new that she had not yet engaged in target practice, and many of her crew had never even heard her guns fired.

Captain William Sampson welcomed Roosevelt aboard and escorted him to the bridge amid a terrific clamor of gongs. The decks were cleared for action, breakables stowed away, and porthole-panes left to swing idly as sailors scampered to their stations. Roosevelt, who had just been lunching with the Admiral, looked placid and happy. Word went around that he wanted to see how quickly the “enemy” could be demolished.

The jangling of the gongs gave way to silence, broken only by a general hum of automatic machinery. (It was the constructor’s boast that almost nothing on the Iowa was done by hand “except the opening and closing of throttles and pressing of electric buttons.”)97 A surgeon distributed ear-plugs to the Acting Secretary and his party.98 “Open your mouth, stand on your toes, and let your frame hang loosely,” he advised.

“Two thousand yards,” called a cadet monitoring the ship’s course. A few seconds later there was a silent flash of fire and smoke from the 8-inch guns, followed by a thunderous report that shook the Iowa from stem to stern. Plumes of spray indicated that the shells were fifty yards short of target. A second salvo landed on range, but slightly to one side. Bugles announced that the Iowa’s main battery of 12-inch guns was now being aimed at the floating speck. There was an apprehensive pause, followed by such vast concussions of air, metal, and water that a lifeboat was stove in, and several locked steel doors burst their hinges. Two members of Roosevelt’s party, who had forgotten to assume the necessary simian stance, were jerked into the air, and landed clasping each other wordlessly. They were escorted below for ear ointment, while Roosevelt continued to squint at the target through smoke-begrimed spectacles. Had it been a Spanish battleship, and not a shattered frame of wood and canvas, it would now be sinking.

The exercises lasted another two days, and Roosevelt returned to Washington profoundly moved by what he had seen. “Oh, Lord! If only the people who are ignorant about our Navy could see those great warships in all their majesty and beauty, and could realize how well they are handled, and how well fitted to uphold the honor of America.”99

![]()

THE HOT WEATHER CONTINUED until mid-September, and Roosevelt, showing concern for the Secretary’s health, suggested that he extend his vacation through the beginning of October. This, however, even John D. Long was unprepared to do, and he sent word that he would be back on 28 September. Roosevelt took the news philosophically, for by then he had realized his ambition to consult with the President as Acting Secretary—not once, but three times.100

Hitherto their meetings had been pleasantly impersonal, but now, for some reason, McKinley seemed anxious to flatter him. On 14 September he requested Roosevelt’s company for an afternoon drive.101 He confessed that he had not looked at the Naval Policy of the Presidents pamphlet until he saw what press interest it aroused, whereupon he “read every word of it,” and was “exceedingly glad” it had been published. McKinley then made the astonishing remark that Roosevelt had been “quite right” to criticize Japan’s Hawaiian policy at Sandusky. Finally, he congratulated him on his management of the Navy Department during the past seven weeks. Roosevelt took all this praise with a pinch of salt (“the President,” he told Lodge, “is a bit of a jollier”), but he detected nevertheless a “substratum of satisfaction.”

Swaying gently against the cushions of the Presidential carriage, relaxed after a day of stiff formalities, William McKinley appeared to best advantage. Locomotion quickened his inert body and statuesque head, and the play of light and shade through the window made his masklike face seem mobile and expressive. Roosevelt could forget about the too-short legs and pulpy handshake, and concentrate on the bronzed, magnificent profile. From the neck up, at least, McKinley was every inch a President—or for that matter, an emperor, with his high brow, finely chiseled mouth, and Roman nose. “He does not like to be told that it looks like the nose of Napoleon,” the columnist Frank Carpenter once wrote. “It is a watchful nose, and it watches out for McKinley.”102

Not until the President turned, and gazed directly at his interlocutor, was the personal force which dominated Mark Hanna fully felt. His stare was intimidating in its blackness and steadiness. The pupils, indeed, were at times so dilated as to fuel suspicions that he was privy to Mrs. McKinley’s drug cabinet. Only very perceptive observers were aware that there was no real power behind the gaze: McKinley stared in order to concentrate a sluggish, wandering mind.103

Taking advantage of the President’s affable mood, Roosevelt touched delicately on the possibility of war with Spain and Japan. McKinley agreed that there might be “trouble” on either front. Roosevelt made it clear that he intended to enlist in the Army the moment hostilities began. The President asked what Mrs. Roosevelt would think of such action, and Roosevelt replied, “this was one case” where he would consult neither her nor Cabot Lodge. Laughing, McKinley promised him the opportunity to serve “if war by any chance arose.”104

Three days later Roosevelt received an invitation to dine at the White House, and three days after that went for another drive in the Presidential carriage. This time he made so bold as to present McKinley with a Cuban war plan of his own devising. It proposed a two-stage naval offensive, first with a flying squadron of cruisers, then with a fleet of battleships—all dispatched from Key West within forty-eight hours of a formal declaration. If the Army followed up quickly with a small landing force, he doubted that “acute” hostilities would last more than six weeks. “Meanwhile, our Asiatic Squadron should blockade, and if possible take Manila.”105

![]()

BY 17 SEPTEMBER, Roosevelt was beginning to feel guilty about “dear” Secretary Long rusticating in New England, especially when the Boston Herald printed a mocking story about his desire to replace the old man altogether. He wrote to Long in quick self-defense, protesting his loyalty and subservience rather too vehemently, and ending with a rueful “There! Qui s’excuse s’accuse.”106 But the Secretary took no offense, and proclaimed his entire satisfaction with Roosevelt at a dinner of the Massachusetts Club in Boston. “His enthusiasm and my conservatism make a good combination,” Long said, adding with a twinkle, “It is a liberal education to work with him.”107

Had Long known what Roosevelt was up to on the eve of his return to Washington, he might have employed stronger terminology. On Monday, 27 September,108 the Acting Secretary intercepted a letter from Senator William E. Chandler to Long, recommending that Commodore John A. Howell be appointed commander in chief of the Asiatic Station—the very post Roosevelt wanted for Dewey.109 Howell, though senior, was in his opinion “irresolute” and “extremely afraid of responsibility”;110 the prospect of such an officer leading an attack upon Manila was too depressing to contemplate. With Long due back the following morning, rapid action was necessary.

Roosevelt sent an urgent appeal to Chandler. “Before you commit yourself definitely to Commodore Howell I wish very much you would let me have a chance to talk to you … I shall of course give your letter at once to the Secretary upon his return.”111

Presumably Senator Chandler could not be persuaded, for he withdrew neither his recommendation nor his letter. Throwing all caution to the winds, Roosevelt called in Dewey. “Do you know any Senators?” The Commodore mentioned Redfield Proctor. Roosevelt was delighted, for Proctor had expansionist tendencies and was known to be influential with the President. Dewey must enlist his services at once.112

Senator Proctor obligingly went over to the White House and spoke to McKinley in behalf of the little Commodore. He might have made discreet reference to the fact that Roosevelt also favored Dewey. The President, who took little interest in naval affairs, accepted his advice without question and wrote a memorandum to Secretary Long requesting the appointment.113

Long returned to the Navy Department on 28 September and was greatly annoyed to find what political intrigues had been going on in his absence. Tradition required that he appoint the senior officer, and besides he personally favored Howell. But McKinley’s memo could not be ignored; and so, to quote the sonorous words of Theodore Roosevelt, “in a fortunate hour for the Nation, Dewey was given command of the Asiatic Squadron.”114

The Secretary was still in an irritable mood when Dewey called to thank him and apologize for using the influence of Senator Proctor. It had been necessary, Dewey explained, to counteract Senator Chandler’s recommendation of Howell. “You are in error, Commodore,” snapped Long. “No influence has been brought to bear on behalf of anyone else.”

A few hours later Long, in turn, sent apologies to Dewey. It appeared that Senator Chandler had indeed recommended his rival, but the letter “had arrived while he was absent from the office and while Mr. Roosevelt was Acting Secretary and had only just been brought to his attention.”

The culprit was serenely unrepentant about his delay in forwarding Senator Chandler’s letter, and saw nothing wrong in Dewey’s enlistment of senatorial aid. “A large leniency,” Roosevelt wrote, “should be observed toward the man who uses influence only to get himself a place … near the flashing of the guns.”115

![]()

BY 30 SEPTEMBER, Roosevelt was free to go north for a fortnight’s rest at Sagamore Hill. Before leaving he asked the Secretary’s permission “to talk to him very seriously about the need for an increase in the Navy.” He proceeded to urge the instant construction of six battleships, six large cruisers, seventy-five torpedo-boats, and four dry docks, together with the modernization of ninety-five guns to rapid fire, the laying in of nine thousand armor-piercing projectiles, and the purchase of two million pounds of smokeless powder.

Long could only suggest that Roosevelt list these demands in a memorandum. The Assistant Secretary was eventually persuaded to settle for one battleship.116

![]()

ROOSEVELT WAS BACK in Washington on 15 October, accompanied by his wife and family. Installing them at 1810 N Street, “a very nice house, just opposite the British Embassy,” he set off almost immediately on the campaign trail, stumping in Massachusetts for local candidates, and in Ohio for Senator Hanna.117 On 27 October he turned thirty-nine.

With November came the familiar, seasonal quickening of his activity, as the days shortened and crisp winds stimulated his blood. The ground of Rock Creek Park grew hard under his hobnailed boots, as he and Leonard Wood strolled their endless visionary miles, talking of Cuba, Cuba, Cuba.118

Roosevelt’s duties as Assistant Secretary were not numerous enough to divert him, and he began to show signs of intellectual restlessness. He plotted four more volumes of The Winning of the West, took Frederic Remington to task for rendering badgers “too long and thin,” and yearned for a war with Spain “within the next month.”119 Long sympathetically appointed him president of a board investigating the Navy’s most chronic ailment: friction between line and staff personnel.120 The resultant work load was heavy, yet Roosevelt now toyed with the idea of writing “a historical article on the Mongol Terror, the domination of the Tartar tribes over half of Europe during the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Centuries.”121

Early in the morning of 19 November he sent joyful news to Bamie: “Very unexpectedly Quentin Roosevelt appeared just two hours ago.” Pausing only to enter the boy for Groton, he marched off to work and dictated his most bellicose letter yet, to Lt. Comdr. W. W. Kimball, author of the department’s original war plan.122 “To speak with a frankness which our timid friends would call brutal, I would regard a war with Spain from two standpoints: first, the advisability on the grounds both of humanity and self-interest of interfering on behalf of the Cubans … second … the benefit done our military forces by trying both the Navy and Army in actual practice.”123

On 8 December, he heard that Dewey had sailed for the Far East, but by now he was so busy writing the report of his Personnel Board that he paid little attention. The eight-thousand-word document, submitted the following day, proposed a bill for the prompt amalgamation of line and staff, on the grounds that engineers, in an industrial age, could no longer be held separate from or inferior to officers above deck. Roosevelt inserted one of his typical historical parallels, showing how in the mid-seventeenth century sailormen and sea-soldiers had to unite and resolve their differences in much the same way. “We are not making a revolution,” he wrote, “we are merely recognizing and giving shape to an evolution.”124

Secretary Long complimented him highly on the report,125 as did many naval academics and newspaper editors. The New York Evening Post expressed “admiration” for his “grasp and breadth of view” of highly complicated material. “If profound study, evident freedom from bias, and command of the subject could place a report above criticism … nothing would be left to do but the enactment by Congress of the proposed bill.”126

Shortly before Christmas the mammalogist C. Hart Merriam announced that a new species of Olympic Mountain elk had been named Cervus Roosevelti in honor of the founder of the Boone & Crockett Club. “It is fitting that the noblest deer of America should perpetuate the name of one who, in the midst of a busy public career, has found time to study our larger mammals in their native haunts and has written the best accounts we have ever had of their habits and chase.”127

And so the year ended with a crescendo of praise for Assistant Secretary Theodore Roosevelt, who was now recognized to be one of the best-informed and most influential men in Washington.128 He was also, as the Boston Sunday Globe pointed out, by far the most entertaining performer in “the great theater of our national life.” But “it would never do … to permit such a man to get into the Presidency. He would produce national insomnia.”129

“From the neck up, at least, McKinley was every inch a President.”

President William McKinley at the time of the Spanish-American War. (Illustration 22.2)