So into the strait

Where his foes lie in wait,

Gallant King Olaf

Sails to his fate!

![]()

NIGHT FELL, and the band of the 2nd Infantry struck up “The Star-Spangled Banner.” Almost on cue, General Shafter’s invasion fleet lit up like a galaxy, spangling the dark sea from one horizon to the other. Lieutenant Colonel Roosevelt stood with bared head on the bridge of the Yucatán, while soldierly emotions surged in his breast. He had no idea where he was being sent—it might not be Cuba at all, merely Puerto Rico—nor what he would be ordered to do when he got there; yet he believed “that the nearing future held … many chances of death, of honor and renown.” If he failed, he would “share the fate of all who fail.” But if he succeeded, he would help “score the first great triumph of a mighty world-movement.”1

Roosevelt supposed that his fellow Rough Riders could dimly feel what he was feeling, but found that only one of them had enough “soul and imagination” to articulate such thoughts. This was Captain “Bucky” O’Neill, the prematurely grizzled, chain-smokingex-Mayor of Prescott, Arizona, and a sheriff “whose name was a byword of terror to every wrong-doer, white or red.” O’Neill was capable of “discussing Aryan word-roots … and then sliding off into a review of the novels of Balzac.” He could demonstrate Apache signs which reminded Roosevelt curiously of those used by the Sioux and Mandans in Dakota.2 He was, in short, a kindred soul, a man to contemplate the night sky with.

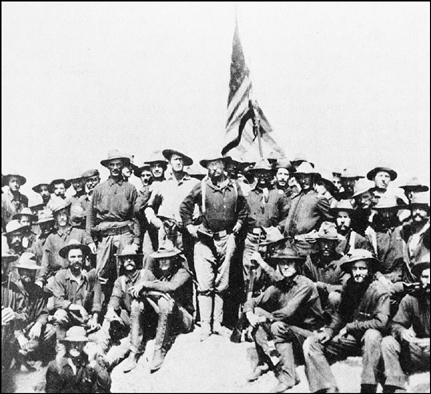

“He led these men in one of the noblest fights of the century.”

Colonel Roosevelt and his Rough Riders atop San Juan Heights, Cuba. (Illustration 25.1)

“Who would not risk his life for a star?” asked Bucky, as the two officers leaned against the railings and searched for the Southern Cross. The metaphor made up in sincerity what it lacked in originality, and it was duly recorded for quotation in Roosevelt’s war memoirs.3

For six days the armada steamed southeast across a glassy ocean, under cloudless skies. Its leisurely pace, never more than seven knots, and frequently only four, was caused by the drag of two giant landing-scows and a tank-ship filled with drinking water. Since the thirty-one transport ships varied greatly in power, from big modern liners to iron paddle steamers of Civil War vintage, they straggled farther and farther apart, until the formation was over twenty-five miles long. On one occasion the rear guard lost touch with the vanguard for fourteen hours. Periodically General Shafter would call a halt, while his aides nervously counted ships coming over the horizon astern. Only when the number corresponded with those missing was the expedition allowed to proceed.4

The foreign attachés aboard U.S.S. Segurança did not know whether to be alarmed or amused at the general’s magnificent disdain for enemy torpedo-boats, especially at night. “Had any of these made an attack on the fleet spread over an enormous area, each ship a blaze of lights and with the bands playing at times, a smart Spanish officer could not have failed to inflict a very serious loss,” wrote Captain Alfred W. Paget of the British Navy.5 The American Navy was equally concerned, and the fleet’s warship escort made plain its annoyance by megaphone and semaphore; but Shafter spread over an enormous area himself, and was content to let his fleet do the same.

For officers like Roosevelt, who had airy first-class accommodations and wicker easy chairs, “it was very pleasant sailing southward through the tropic seas.”6 But for the men jammed below deck in splintery wooden bunks, breathing the same air as horses and mules—not to mention the effluvia of compacting layers of manure—things were rather less tolerable. There was a chorus of cheers on the morning of 20 June, when the fleet swung suddenly southwest “and we all knew that our destination was Santiago.”7

A blue line of mountains rose near the Yucatán’s starboard bow, looming ever higher as the ship steamed within ten miles of shore. Some peaks rose six thousand feet sheer. Their silent massiveness gave the more thoughtful Rough Riders pause. “Our dreams turned to questions of an immediate concern—what was the enemy like? Would he show much resistance? How good was he in battle?”8 But the mountains gave off no lethal bursts of smoke, and the fleet continued its coastal cruise across water “smooth as a mill pond.” Apprehension changed slowly to bravado: soon the troops were shouting war-cries across the water, and waiting for echoes to roll back.9

At noon the fleet came to a halt about twenty miles east of Morro Castle, and a captain from the U.S. Navy blockade squadron (still holding nine Spanish warships in Santiago Harbor) came on board the Segurança to escort General Shafter to a rendezvous with Admiral Sampson. It was rumored that the two commanders, after reviewing several possible landing sites nearer the city, would be rowed ashore for a secret council of war with General Calixto García, head of the insurrectos.10

The Segurança steamed off alone, leaving the transport ships to wallow placidly behind at anchor. Hours passed while the invaders gazed their fill upon Cuba, “Pearl of the Antilles,” the most beautiful island within reach of the American continent.11 “Every feature of the landscape,” wrote Richard Harding Davis, “was painted in high lights; there was no shading, it was all brilliant, gorgeous, and glaring. The sea was an indigo blue, like the blue in a washtub; the green of the mountains was the green of corroded copper; the scarlet trees were the red of a Tommy’s jacket, and the sun was like a lime-light in its fierceness.”12

Meanwhile, in a palm-thatched hut somewhere along the coast,13 Shafter, Sampson, and García were perfecting a tripartite plan for the Santiago campaign. It was agreed that the debarkation of troops would be made on the morning of the twenty-second at Daiquirí, eighteen miles east of Santiago. Daiquirí was a mere village, but it had a beach, and a pier of sorts, which should be able to handle Shafter’s lifeboats and scows. Starting at dawn, the Navy would bombard the village, as well as several other neighboring seaside settlements, in order to confuse the Spaniards as to which landing point the Army had chosen.14

Once the Fifth Corps was safely ashore at Daiquirí, plans called for Shafter to capture the fishing port of Siboney, seven miles farther west, then to march directly up the Camino Real over the hills to Santiago, twelve miles north. This would be the most difficult and dangerous part of the expedition, for enemy defenses were known to be concentrated in those hills. One ridge in particular—known as San Juan Heights—was regarded as almost insuperable,15 so heavy were its fortifications, and so determined was Spain’s General Linares to hold it as the last wall protecting Santiago. If he could keep Shafter’s men off at cannon-point for a few weeks, his two most powerful allies—yellow fever and dysentery—would surely lay low all those still standing. But if the yanquis by some miracle broke through, Santiago, and Cuba, and the war, and the Western Hemisphere would be theirs.

![]()

NOT UNTIL THE EVENING of the following day were battle orders broadcast among the thirty-one transport ships. When the news reached Roosevelt, he entertained the Rough Riders with his patented war-dance, evolved from years of prancing around the carcasses of large game animals. Hand on hip, hat waving in the air, he sang:

“Shout hurrah for Erin-go-Bragh,

And all the Yankee nation!”16

Aboard the Yucatán a macabre toast was drunk: “To the Officers—may they get killed, wounded or promoted!”17 Only Roosevelt, presumably, could relish such sentiments to the full. That night, in darkened dormitories that rolled and pitched uneasily in a rising sea, the Rough Riders prepared themselves for invasion. The solemnity of what was about to happen, the likelihood that some soldiers would never sleep again (three hundred Spanish troops were said to be entrenched on the heights above Daiquirí, with heavy guns),18 made the hours before reveille increasingly suspenseful.

At 3:30 A.M. bugles sounded below decks. In the shadows, men rose whispering, dressed, and donned their bulky equipment: blanket rolls, full canteens, hundred-round ammunition belts, and haversacks stuffed with three days’ rations.19

Daiquirí was just visible when they emerged on deck in the chill predawn light. It was little more than a notch in the cliffs, with a clutch of corrugated-zinc huts surrounding an old ironworks and a railhead lined with ore-cars. The village appeared to be deserted, but as the Rough Riders looked, a great column of flame leaped up from the ironworks. Evidently the Spaniards intended to destroy Daiquirí’s only industrial resource before the norteamericanos arrived to exploit it.

Debarkation did not begin for several hours, for the sea was choppy and soldiers had considerable difficulty dropping into boats which rose and sank with the speed of elevators. At about 9:40 A.M. the thunder of naval bombardment was heard from Siboney, seven miles west. One by one the warships along the coast opened fire, until the air was shaking with noise and the zinc roofs were fluttering above Daiquirí like leaves blown in a storm. The flames spread along the ore-cars to the shacks, and bands aboard the truck-cars struck up the expedition’s most-requested number: “There’ll Be a Hot Time in the Old Town Tonight.”20

Not until 10:10 A.M. did Shafter silence the guns and order the first landing parties ashore. Some boats headed for the wooden pier, where even greater difficulties arose: now it was like jumping out of an elevator onto a passing floor. The fact that the pier was rotting, and slimy, did not help matters. The soldiers had to wait until high waves lifted them above dock level before leaping, in the knowledge that they would be crushed and ground to pieces if they fell between the boat and the barnacled pilings. Other boats raced for the beach, through tumbling surf, and deposited their passengers on the shingle, some head over heels and cursing.21

The problem of getting horses and mules ashore was solved in typical Shafter fashion: they were simply shoved into the sea and left to find the beach for themselves. Some hysterical animals chose to swim instead for Haiti, until a bugler on the beach thoughtfully blew a cavalry call. The horses, according to one witness, “came round to the right and made for the beach like ships answering their helms.”22

Meanwhile, Roosevelt was supervising the unloading of his two horses, Rain-in-the-Face and Texas. Out of respect to their eminent owner, sailors winched them into the water on booms; but a huge breaker engulfed Rain-in-the-Face, and drowned her before she could be released from harness. Roosevelt, “snorting like a bull, split the air with one blasphemy after another,” wrote Albert Smith, the Vitagraph cameraman. The terrified sailors took such care with Texas that she seemed to hang in the air indefinitely, until Roosevelt, losing his temper again, bellowed, “Stop that goddamned animal torture!” This time there was no mishap, and the little horse splashed safely to shore.23

According to general orders, the Rough Riders were not due to land until much later in the day, after most of the regulars, but it was soon apparent to Roosevelt that “the go-as-you-please” principle applied to men as well as horses. As luck would have it, his old aide from the Navy Department, Lieutenant Sharp, steamed by in a converted yacht, and offered to pilot the Yucatán within a few hundred yards of shore. From this privileged position the Rough Riders landed well in advance of the other cavalry regiments.24 TheYucatán thereupon steamed away, taking large quantities of personal effects with her before any attempt was made to unload them. Roosevelt was left standing on the sand with nothing but a yellow mackintosh and a toothbrush. Fortunately his most essential items of baggage were inside his Rough Rider hat: several extra pairs of spectacles, sewn into the lining.25 If he was to meet his fate in Cuba, he wished to see it in clear focus.

More than six thousand troops were on Cuban soil by sunset. Not one shot had been fired in Daiquirí’s defense; the ruined village was occupied only by a few insurrectos, rather the worse for bombardment.

As dusk fell, campfires began to glow along the beach and in the little valley where the Rough Riders were lying on ponchos. At intervals there were shrieks and laughter, as red ants or crabs disturbed their rest;26 but the tropical air was balmy, the sky filled with comforting stars, and soon everybody except the guards was asleep.

![]()

POLITICAL RIVALRY, that most ubiquitous of social weeds, thrives just as fast on tropical islands as in the smoke-filled rooms of northern capitals. By the time the Rough Riders awoke on the morning of 23 June, two generals were already locked in contention for the honor of leading the march upon Santiago.

According to invasion orders, Major General Joseph (“Fighting Joe”) Wheeler, commander of the Cavalry Division, was supposed to follow Brigadier General H. W. Lawton of the 2nd Infantry Division to Siboney and remain there to supervise the rest of the landing operation while Lawton established himself farther inland on the Camino Real, or Santiago road. But not for nothing had Fighting Joe earned his nickname, and his reputation of “never staying still in one place long enough for the Almighty to put a finger on him.”27 The fact that Lawton was tall, and had fought for the Union in the Civil War, while Wheeler was five foot two, and had been the leader of the Confederate cavalry, only intensified the latter’s ambition to be first to encounter “the Yankees—dammit, I mean the Spaniards.”28 Needless to say, this attitude endeared him to the Rough Riders. “A regular game-cock,”29 was Roosevelt’s opinion of the bristling little general.

Lawton, whose division landed first on the twenty-second, had left for Siboney the same afternoon. Marching at a leisurely pace, he encamped en route and completed his journey next morning. The port (which had been so hastily vacated that tortillas were still steaming over breakfast coals) was reported “captured” at 9:20 A.M., much to Wheeler’s chagrin. Only then did he receive the longed-for permission to bring his men on to Siboney.30

Doubtless General Shafter expected the cavalry to proceed west at the same comfortable pace as the infantry had the day before. From the moment the bugles sounded “March” in Daiquirí at 3:43 P.M., 23 June,31 it was plain that Wheeler wanted the Rough Riders in Siboney by nightfall.

Seven miles did not look far on the map, but paper was flat and the Cuban coastline was not. The hard coral road ran up and down precipitous hills, and the heat was blinding enough to incapacitate men in loincloths, let alone military uniform and the heavy accouterments of war. Even when the road leveled off to wind through coconut groves, the entrapped humidity and clouds of insects buzzing over rotten fruit made the exposed slopes seem almost preferable. Soon blanket rolls, cans of food, coats, and even underwear were littering the trail, to be picked up by delighted Cubans.32

“I shall never forget that terrible march to Siboney,” wrote Edward Marshall of the New York Journal. Unlike “Dandy Dick” Davis of the Herald (impeccable as usual in a tropical suit and white helmet), Marshall was unable to ride with the officers. He had lost his horse during the debarkation, and had generously offered his saddle to Roosevelt, who had little Texas, but nothing in the way of harness.33 Roosevelt accepted the gift, but refused to ride “while my men are walking.”34 All the way to Siboney he tramped along in his yellow mackintosh, streaming with perspiration and earning the affectionate respect of his troopers.

“Wood’s Weary Walkers”—never had the name seemed more apt—caught up with General Lawton’s rear guard, a mile or so above Siboney, just as dusk fell. Without slackening pace, they marched on down the valley. Burr McIntosh of Leslie’s Magazineasked the commander of the rear guard, Brigadier General J. C. Bates, where they were going. “I don’t know,” said Bates, peering after them in the dim light. “They have not had any orders to go on beyond us.”35

If not, they very soon had. Wood encamped his men in a coconut grove well north of Siboney, then rode into the squalid village for a council of war with General Wheeler and his own immediate superior, Brigadier General S.B.M. Young. He learned that Wheeler had made a personal reconnaissance of the Camino Real that afternoon, and had found that the first line of enemy defenses was four miles up-country, at a point where the road crested a spur in the mountains. Fighting Joe’s orders were “to hit the Spaniards … as soon after daybreak as possible.”36

![]()

WHILE WOOD, WHEELER, and Young discussed tactics at headquarters, Roosevelt stayed with the men in camp, eating hardtack and pork and drinking fire-boiled coffee. Rain began to fall. He sat for a couple of hours in his yellow slicker, not bothering to seek shelter. It was at times like this, when lack of seniority excluded him from the decision-making process, that he had leisure to reflect on what he had missed by turning down the offer of the colonelcy. But war had its opportunities.…

The sky cleared eventually, and new fires began to blaze as the soldiers stripped off their sweat-drenched, rain-sodden clothes and held them up to dry. Roosevelt strolled over to L Troop, where two of the biggest men in the regiment, Captain Allyn Capron and Sergeant Hamilton Fish, were standing talking. He caught himself admiring their splendid bodies in the flickering glare. “Their frames seemed of steel, to withstand all fatigue; they were flushed with health; in their eyes shone high resolve and fiery desire.” Like himself, they were “filled with eager longing to show their mettle.”37

![]()

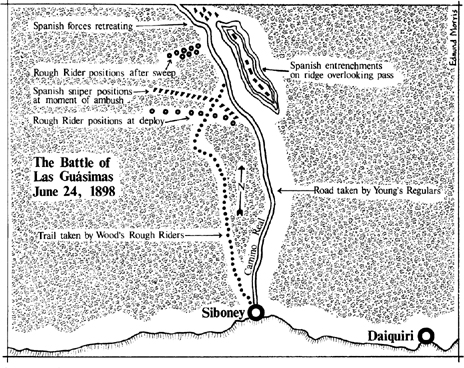

THE PASS OVER THE mountains where the Spanish lay in wait was locally known as Las Guásimas, after a clump of guácima, or hog-nut trees that grew there. Cuban informants, aware that Americans would have difficulty recognizing these trees in the surrounding jungle, gave General Wheeler a more macabre landmark to search out. There was an approach in the vicinity, scouts said, where the body of a dead guerrilla lay across the trail. Discovery of that body would indicate that the enemy was somewhere in the vicinity38—perhaps only a hundred yards ahead.

This was hardly the most sophisticated reconnaissance briefing, but it was good enough for Fighting Joe. Shortly before dawn the next morning, 24 June, his dismounted cavalrymen began a two-column advance upon Las Guásimas. The right thrust, on the west, was undertaken by General Young and about 470 Regulars, marching directly up the Camino Real. The left thrust, up a high but roughly parallel trail half a mile to the west, was undertaken by Wood and 500 Rough Riders. If Cuban information was correct, trail and road would meet about where the dead guerrilla lay, enabling Young and Wood to deploy, touch flanks, then lead their thousand men against the enemy-held ridge together. Spanish forces were estimated at about 2,000.39

Climbing quickly out of the valley at 6:00 A.M., the Rough Riders took their last look at Siboney, seven hundred feet below. Gilded by the sun, half-shrouded in early morning mist, the squalid little port looked almost pretty. It gave off faint sounds, “like blasts from faery trumpets.”40 Evidently Lawton’s men were at last waking up.

From this viewpoint the trail led northwest along a forest ridge, the vegetation growing ever taller and thicker until it closed overhead. The Rough Riders found themselves irradiated with chlorophyllic half-light; its effect would have been eerily charming had thetropical warmth not made it sinister. “The jungle had a kind of hot, sullen beauty,” one trooper remembered. “We had the feeling that it resented our intrusion—that, if we penetrated too far, it would rise up in anger, and smother us.”41 From time to time a cooing of wood-doves, and the call of a tropical cuckoo, strange to Roosevelt’s ears, sounded in the trees,42 although the birds themselves were never seen.

The Rough Riders advanced like Indians, behind a “point” tipped by those two steely giants, Sergeant Fish and Captain Capron. After them came Wood, flanked by three aides, and Roosevelt, flanked by his two favorite reporters, Richard Harding Davis of theHerald and Edward Marshall of the Journal. Both men had reported favorably, in the past, on his exploits as Police Commissioner; he now relied on them to glorify him as a warrior, and cultivated them accordingly. Stephen Crane of the World, whom Roosevelt did not like at all,43 was left to bring up the extreme rear.

Half a mile west and two or three hundred feet lower, on the valley road, General Young’s infantrymen were marching in a roughly parallel direction. But the intervening vegetation was so dense that they could be neither seen nor heard, save for a bugle-call now and then.44

After about an hour’s march, Captain Capron came back through the trees to announce that his scout had discovered the body of the dead guerrilla. Wood turned to Roosevelt. “Pass the word back to keep silence in the ranks.”45 Then he disappeared up the trail with Capron, leaving Roosevelt and Marshall to discuss coolly—and disobediently—a lunch they had once had with William Randolph Hearst at the Astor House. Meanwhile the men relaxed on the ground, chewing blades of grass and fanning the stagnant air with their hats.46

As Roosevelt talked, his glance fell on some barbed wire curling from a fence to the left of the trail. He reached for a strand, gazed at it with the expert eye of a ranchman, and started. “My God! This wire has been cut today.”

“What makes you think so?” asked Marshall.

“The end is bright, and there has been enough dew, even since sunrise, to put a light rust on it …”47

Just as he spoke, the regimental surgeon came up from behind, riding noisily on a mule. Roosevelt leaped to silence him. Then, as the Rough Riders held their breath, a terrifying sound came winging through the bushes.48

![]()

MARSHALL, WHO WAS to hear the sound endlessly repeated that day, and would find himself paralyzed from the waist down by it, described it as a z-z-z-z-z-eu, rising to a shrill crescendo, then sinking with a moan on the eu. It was the trajectory of a high-speed Mauser bullet, standard equipment with Spanish snipers. Bloodcurdling though the sound was, with the concomitant ping and zip of perforated leaves (enabling a man to judge its approach velocity, and the utter impossibility of getting out of the way in time), the worst moment came when the z-eu was followed by a loud chug, indicating that the bullet had hit flesh. The force of impact on a man’s outstretched arm was enough to spin him around before he thumped in a flaccid heap on the ground. Often as not, a man so struck would rise again after a few minutes, none the worse but for a tiny, cauterized hole; the flaccidity was merely a shock reaction, common to all Mauser victims.49 But other men lay where they dropped.

The first soldier to be killed by these first rifleshots of the Spanish-American War was Sergeant Hamilton Fish, who fell at the feet of Captain Capron. Then another Mauser took Capron in the heart. So much for their “frames of steel.”50 Six more Rough Riders died in the hail of fire that followed—the most intense, according to one scholarly major, in the history of warfare.51 Thirty-four men were wounded, many of them repeatedly. Private Isbell of L Troop was hit three times in the neck, twice in the left hand, once in the right hand, and finally in the head.52 Roosevelt, literally jumping up and down with excitement53 as he awaited Wood’s order to deploy, made no effort to run for cover; somehow the bullets missed him, although one did smack into a tree inches from his cheek, and filled his eyes with splinters of bark.54

Wood, whose casual confidence under fire earned him the nickname “Old Icebox,” asked Roosevelt to take three troops into the jungle on the right, while three other troops fanned out on the left. Marshall remained behind, idly curious to see how the Lieutenant Colonel comported himself in battle.

Perhaps a dozen of Roosevelt’s men had passed into the thicket before he did. Then he stepped across the wire himself, and, from that instant, became the most magnificent soldier I have ever seen. It was as if that barbed-wire strand had formed a dividing line in his life, and that when he stepped across it he left behind him in the bridle path all those unadmirable and conspicuous traits which have so often caused him to be justly criticized in civic life, and found on the other side of it, in that Cuban thicket, the coolness, the calm judgment, the towering heroism, which made him, perhaps, the most admired and best beloved of all Americans in Cuba.55

Where the shots were coming from even Roosevelt, with his acute hearing, could not tell; he knew only that the snipers were distant and highly placed. Evidently the Spanish, trained in guerrilla tactics by three years of fighting the Cubans, knew exactly where the trail was; but how, since the Rough Riders were camouflaged by trees, did they know where to shoot? Much later it transpired that the strange cooing and cuckoo-calls he had heard earlier came from lookouts posted in the jungle, tracking the regiment’s progress to the point of ambush.56

All at once the trees parted and Roosevelt found himself gazing out over the Santiago road to a razorback ridge on the opposite side of the valley. General Young’s men were stationed below, under heavy fire themselves by the sound of it; but thanks to the enemy’s smokeless powder he still could not see the entrenchments. It took a newspaperman to point the Spaniards out to him. “There they are, Colonel,” cried Richard Harding Davis, “look over there; I can see their hats near that glade.” Roosevelt focused his binoculars, estimated the range, and ordered his troops to “rapid fire.” Davis joined in with a carbine he had picked up somewhere.57 The woods, according to Stephen Crane, “became aglow with fighting.” In three minutes, nine men were lying on their backs in Roosevelt’s immediate vicinity.58 But the Rough Riders fired back with such blistering accuracy that the Spaniards soon quit their trenches and took refuge in the jungle farther up the ridge.

Unable to pursue them for an impenetrable wall of vines, Roosevelt ordered his men back to the main trail, where the Mausers were whining as viciously as ever. Although he did not fully realize it, he had succeeded brilliantly in his first military skirmish. By engaging and driving back the enemy’s foremost flank, he had exposed troops holding the top of the ridge to cross-fire from the entire line of Rough Riders, and frontal attack from General Young’s regulars.59 The way was now open for a final grand charge by all the American forces, with Roosevelt commanding the extreme left, Wood commanding the center, and the regulars on the right advancing under orders from General Wheeler himself. About nine hundred men broke out into the open and ran up the valley (Roosevelt stopping to pick up three Mauser cartridges as souvenirs for his children),60 their rifle-cracks drowned in the booming of four Hotchkiss mountain-guns. Like ants shaken from a biscuit, some fifteen hundred Spaniards leaped from their rock-forts along the ridge and scattered in the direction of Santiago. “We’ve got the damn Yankees on the run!” roared Fighting Joe.61

By 9:20 A.M. the Battle of Las Guásimas was over. An exhausted major looked at his watch, shook it incredulously, and held it up to his ear. He was sure that the engagement had lasted at least six hours.62 Actually it had been only two.

A few minutes later the first of General Lawton’s infantrymen arrived and found that their services were not needed. Lawton was furious. According to one report he accused Wheeler of deliberately stealing a march on him. “I was given command of the advance, and I want you to know that I propose to keep it, by God, even if I have to put a guard to keep other troops in the rear!”63 Fighting Joe was philosophical, for he received in due time the congratulations of General Shafter. As long as that leisurely officer remained on board the Segurança, Wheeler, not Lawton, was the senior general ashore, and he could issue and interpret orders as he saw fit. For the moment he was satisfied. He had driven back the Spaniards; his bandy-legged cavalry had outmarched the infantry; best of all, hehad avenged Appomattox. Such triumph was cheap at a cost of sixteen Americans dead and fifty-two wounded, to Spain’s figures of ten and eight.64 Others, gazing at the sightless eyes of Hamilton Fish, or the shattered spine of Edward Marshall (writhing in agony as he dictated his dispatch to Stephen Crane),65 might wonder if the Battle of Las Guásimas had been really worth it.

![]()

“ONE OBJECT AT LEAST was accomplished,” wrote Leslie’s correspondent Burr McIntosh, whom Roosevelt had also left behind at Siboney. “The names of several men were in the newspapers before the names of several others, and a number of newspaper men, who were sure to write things in the proper spirit, were given the necessary ‘tip’.”66 Also the necessary flattery: Roosevelt was quick to cite Richard Harding Davis in his official report, and even tried to get the Associated Press to mention Davis’s gallantry while the battle was still going on.67 Davis, who tended to treat friends as they treated him, responded with laudatory accounts of the battle, earning praise for “Roosevelt’s Rough Riders” as its only apparent heroes. In Washington there was talk of promoting Roosevelt to the rank of brigadier general, and in New York a coalition of independent Republicans announced that they intended to nominate him for Governor in September.68

Whether the praise was deserved or not, Roosevelt’s personal views of his role in the Las Guásimas victory were modest, and remained so always. He liked to joke about his inability to see the enemy, his difficulty running with a sword swinging between his legs, and his policy of firing at any target that was not a tree. However, “as throughout the morning I had preserved a specious aspect of wisdom, and had commanded first one wing and then the other wing, the fight really was a capital thing for me, for practically all the men had served under my actual command, and thenceforth felt enthusiastic belief that I would lead them aright.”69

![]()

IN HIS SPEECH to the Naval War College a year before, Roosevelt had urged America to prepare for “blood, sweat, and tears” when war came. The Battle of Las Guásimas gave the Rough Riders ample opportunity to wallow in all three. Regimental surgeon Bob Church looked, that evening, “like a kid who had gotten his hands and arms into a bucket of thick red paint.”70 Gouts of blood trembled on the leaves along the trail, and plastered whole sheaves of grass together. Fresh blood flowed as Church snipped open Mauser holes in order to dress them. Wherever a casualty lay, the predators of Cuba collected in rings: huge land-crabs shredding corpses with their clattering claws, vultures tearing off lips and eyelids, then the eyeballs, and finally whole faces.71 But the most despised predators were Cubans themselves, who invariably materialized from the jungle to strip the dead of clothing, equipment, and jewelry, and rummage around for jettisoned food-cans. Was it for these squat, dull-eyed peasants that the flower of America had died?

Compassion, never one of Theodore Roosevelt’s outstanding characteristics, was notably absent from his written accounts of Las Guásimas and its aftermath—unless the perfunctory phrase “poor Capron and Ham Fish”72 can be counted to mean anything. His only recorded emotion as the Rough Riders buried seven of their dead next morning, in a common grave darkened with the shadows of circling buzzards, was pride in its all-American variety: “—Indian and cowboy, miner, packer, and college athlete, the man of unknown ancestry from the lonely Western plains, and the man who carried on his watch the crest of the Stuyvesants and the Fishes.” When Bucky O’Neill turned to him and asked, “Colonel, isn’t it Whitman who says of the vultures that ‘they pluck the eyes of princes, and tear the flesh of kings’?” Roosevelt answered coldly that he could not place the quotation.73

His duty, as he saw it, lay with those who were still standing and able to fight. Since landing in Cuba, his men had had nothing to eat or drink but hardtack, bacon, and sugarless coffee. What was left of these heavy comestibles had been dumped during their two forced marches, and due to General Shafter’s “maddening” mismanagement of the unloading operation (still in process at Siboney), no fresh supplies were expected for several days. Soon the Rough Riders were forced to scrounge, like Cubans, in the bags of dead Spanish mules.74

On the morning of 26 June, Roosevelt got wind of a stockpile of beans on the beach, and marched a squad of men hastily down to investigate. There were, indeed, at least eleven hundred pounds of beans available, so he went into the commissary and demanded the full amount for his regiment. The commissar reached for a book of regulations and showed him that “under sub-section B of section C of article 4, or something like that,” beans were available only to officers. Roosevelt had learned enough during his six years as Civil Service Commissioner not to protest this attitude. He merely went outside for a moment, then returned and demanded eleven hundred pounds of beans “for the officer’s mess.”

|

COMMISSAR |

But your officers cannot eat eleven hundred pounds of beans. |

|

ROOSEVELT |

You don’t know what appetites my officers have. |

|

COMMISSAR |

(wavering) I’ll have to send the requisition to Washington. |

|

ROOSEVELT |

All right, only give me the beans. |

|

COMMISSAR |

I’m afraid they’ll take it out of your salary. |

|

ROOSEVELT |

That will be all right, only give me the beans.75 |

So the Rough Riders got their beans, and the requisition went to Washington. “Oh! what a feast we had, and how we enjoyed it!”76

![]()

“THE AVERAGE HEIGHT among the Americans,” reported a Barcelona newspaper, “is 5 feet 2 inches. This is due to their living almost entirely upon vegetables as they ship all their beef out of the country, so eager are they to make money. There is no doubt that one full-grown Spaniard can defeat any three men in America.”77

![]()

FOR THE LAST SIX DAYS of June the Rough Riders camped in a little Eden on the westward slope of the ridge of Las Guásimas. They washed their bloody uniforms in a stream gushing out of the jungle, learned how to fry mangoes and, when tobacco ran out at a black-market price of $2 a plug, how to smoke dried grass, roots, and manure. The Cubans, if useless for all else, were at least good for rum: a can of Army beef (vintage 1894, according to the label) was enough to fill one’s canteen, and a whole squad could get drunk on the proceeds of one Rough Rider blanket.78

Fifth Corps staff, meanwhile, had solved the complicated logistical problem of getting General Shafter finally onshore and bringing him up the Camino Real in a sagging buckboard. Like all obese people, the general felt the heat badly; in addition his gout was worse, and he had contracted a scalp condition which necessitated constant scratching by aides.79 Not until the morning of 30 June did he venture down from the ridge to explore the terrain still separating his forces from Santiago.80

The best vantage point was a hill named El Pozo, to the left of the road where it crossed the river—or, to be more precise, where the river crossed the road. Ascending this hill on the Army’s stoutest mule, Shafter gazed across a landscape which the Rough Riders, from their camp in the rear, already knew by heart.

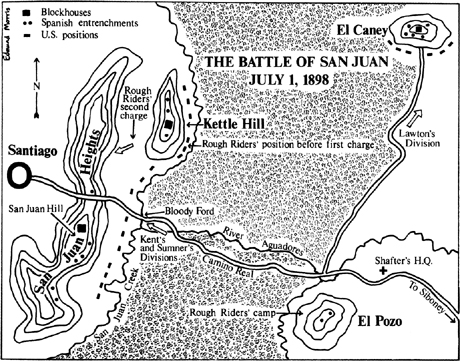

Dense jungle filled the basin in front of him. There were hills to the right and hills to the left—the latter crowned by a fortified village named El Caney. Another ridge of hills rose on the far side of the basin, about a mile and a half away, walling off Santiago in another basin, much wider and lower to the west. The peaks undulated enticingly, exposing whitewashed triangles of the city to view, but their steep facing slopes, and in particular the heavy entrenchments visible all the way along the crest, made it obvious at a glance that they would be, as García had warned, General Linares’s last line of defense. These were the San Juan Heights, and that dominant central outcrop, crowned with a blockhouse, was San Juan Hill itself. Since the Camino Real snaked over the range slightly to the right of it, capture of the hill meant possession of the road. Shafter would then be able to mount a land siege of Santiago while Admiral Sampson continued his siege by sea. It would be a matter of time until starvation forced the surrender of the city.

If General Shafter noticed a smaller hill in front of San Juan Heights, cutting off his view of some of the road, he did not consider it worthy of inclusion in his hand-drawn map.81

![]()

A COUNCIL OF WAR was called in command headquarters early in the afternoon. Shafter looked ill and exhausted by his ascent of El Pozo—obviously being at the front did not agree with him—but he had a definite plan of campaign worked out, and announced it in peremptory tones. The Fifth Corps would begin the advance upon Santiago immediately, that very evening. (Eight thousand enemy troops were reported to be on their way from another part of the province, to supplement the twelve thousand already in and around Santiago: clearly not a moment must be lost.) The divisions would move along the Camino Real under cover of dusk, and spread out in the vicinity of El Pozo. While Brigadier General J. F. Kent’s 1st Infantry and General Wheeler’s Cavalry encamped on the flanks of the hill, General Lawton’s 2nd Infantry would swing right and march toward El Caney, and bivouac somewhere en route. All forces would then be poised for a big battle which would inevitably begin next morning.82

Sitting vast and rumpled in shirt-sleeves and suspenders, his gouty foot wrapped in burlap,83 Shafter detailed the swift, simple maneuvers he would like to see, or at least hear about, during the day. At dawn General Lawton would assault El Caney and take the fort there, cutting off the northern supply route to Santiago. This should take only about three hours. Meanwhile the other two divisions would launch their own attack upon San Juan Hill, moving through the jungle along Camino Real, and deploying as they approached the foothills. Lawton was to join them on the right as soon as he was free, and the day’s action would climax in a massive onslaught on the Heights, plainly inspired by the final charge at Las Guásimas.84

The council of war was barely over when a staff officer rode over to Rough Rider headquarters and announced that Generals Wheeler and Young had been felled by fever. Command of the Cavalry Division therefore devolved upon Brigadier General Samuel S. Sumner, and that of Young’s 2nd Brigade upon Leonard Wood; “while to my intense delight,” wrote Theodore Roosevelt, “I got my regiment.”85 His long-postponed colonelcy had come just in time for the decisive engagement of the Spanish-American War.

![]()

ONE SMALL DETAIL which had apparently escaped General Shafter’s attention was that mobilization of some sixteen thousand men along a road ten feet wide would cause certain problems, especially as he had ordered the entire Fifth Corps to start marching at 4:00 P.M. A violent rainstorm at 3:30 did not help matters, for it converted the Camino Real into a ditch which squished deeper under every fresh line of boots.86

“Darkness came and still we marched,” one Rough Rider remembered. “The tropical moon rose. You could almost envy the ease with which this orange ball crossed the sky. It was all we could do to lift our muddy shoes.”87 At last, at about eight o’clock, the dark silhouette of El Pozo loomed up through the trees, and the regiment clambered halfway up its eastern slope. Leaving his men to sleep where they chose, Roosevelt strolled over the brow of the hill and found Wood establishing temporary headquarters in an abandoned sugar factory. Brigadier General and Colonel now, they gazed across at San Juan Heights, and the refracted glow of Santiago’s street lights.88 Then they curled up in their yellow slickers on a bed of saddle blankets and went to sleep.

![]()

THE FIRST OF JULY, 1898, which Roosevelt ever afterward called “the great day of my life,” dawned to a fugato of bugles, phrase echoing phrase as reveille sounded in the various camps.89 The morning was Elysian, with a pink sky lightening rapidly to pale, cloudless blue. Mists filled the basin below El Pozo, evaporating quickly as the air warmed, exposing first the crowns of royal palms, then the lower green of deciduous trees and vines. Hills rippled around the horizon to east, west, and north, like a violet backdrop. As the vapor burned away, the effect to Roosevelt was of shimmering curtains rising to disclose “an amphitheatre for the battle.”90

While his men got up he walked about calmly lathering his face, reassuring the many who had woken afraid.91 He wore a dark blue shirt with yellow suspenders, fastened with silver leaves, and—in the apparent belief that people might otherwise mistake him for a Regular—a stand-up collar emblazoned with the Volunteer insignia.92 Breakfast was frugal: a handful of beans, the invariable slabs of fat bacon and hardtack, washed down with bitter coffee. Then the regiment fell in, along with others of Wood’s brigade, to await marching orders. Four big guns of the 1st Artillery were hauled up El Pozo and wedged into position. A staff officer came by with the predictable news that General Shafter had been taken ill during the night, and would have to command the battle from his cot.93Roosevelt probably paid little attention: he was waiting for the first detonation of Lawton’s battery.

It came at 6:30, a sullen roar that rolled over the still-sleeping jungle and sent clouds of birds into the air. Almost immediately the El Pozo battery followed suit, and Roosevelt and Wood became conscious of a white plume of gunsmoke hanging motionless over their heads. Wood barely had time to say “he wished our brigade could be moved somewhere else” when there was a whistling rush from the direction of San Juan Hill, and something exploded in the midst of the white plume. Another shell, another and another: the second explosion raised a shrapnel bump on Roosevelt’s wrist, wounded four Rough Riders, and blew the leg off a Regular. The fourth killed and maimed “a good many” Cubans, and perforated the lungs of Wood’s horse. Evidently Spanish gunners were as deadly accurate as Spanish riflemen. Roosevelt waited no longer, and hustled his regiment downhill into jungle cover.94

About 8:45 the enemy cannonade ceased for no apparent reason—tortilla time?—and General Sumner ordered the Cavalry Division to hurry en masse along Camino Real toward San Juan. About where the jungle thinned out, a creek, also called San Juan, crossed the road at right angles; here the Rough Riders were to deploy to the right, and await further orders before moving up the Heights. Shafter’s original battle plan had been for them to link up with the 1st Infantry, as soon as General Lawton returned in triumph from El Caney; but the continual booming of guns from that quarter indicated that the fort was holding up much better than anticipated.95 For strategic purposes, Lawton’s aid could now be discounted.

The freshness of the early morning had long since evaporated when Roosevelt, riding on Texas, led his men up the road. But last night’s mud was still thick and the jungle gave off insufferable clouds of dank moisture.96 The heat rose steadily to 100 degrees Fahrenheit, and the sun drilled down with blistering force on sweaty arms and shoulders. Roosevelt’s neck, at least, was protected. He had ingeniously attached his blue polka-dot scarf—the unofficial insignia of a Rough Rider—in a semicircular screen dangling from the rim of his sombrero. It fluttered bravely as he trotted along,97 like the plumes of Alexander the Great; later in the day it would serve him to flamboyant effect.

By now the familiar z-z-z-z-eu of Mauser bullets could be heard overhead. They sang louder and louder “in a steady deathly static”98 as Kent’s 1st Regular Brigade, marching just ahead of Roosevelt, approached San Juan Creek. The trees thinned, and suddenly so many thousands of bullets came down, ripping in sheets through grass and reeds and human bodies, that the mud of the crossing turned red, and the water flowing over it ran purple. The Rough Riders wavered, then halted, horrified at the pile-up of bodies in front of them. Ever afterward, this point of deploy was known as Bloody Ford.99

As if to improve still further the marksmanship of the Spanish snipers (many of whom were hidden in the high crests of royal palms, completely camouflaged with green uniforms and smokeless powder), an irresistible target was towed down Camino Real: the observation balloon of the Signal Corps. Glistening and wobbling in the sun, it stayed aloft long enough to reconnoiter another crossing five hundred yards to the left, relieving the gruesome bottleneck at Bloody Ford, and gave the cannons on San Juan Heights a precise indication of the position of the advance column.100

Plunging frantically across the creek, before the riddled balloon sank and smothered them, the Rough Riders found themselves crouching in a field full of waist-high grass. San Juan Hill rose up directly ahead, its blockhouse and breastworks clearly visible, as were the conical straw hats of entrenched soldiers. Roosevelt’s orders were to march to the right, along the bank of the creek, and establish himself at the foot of the little hill that Shafter had overlooked the day before.101 He, however, had not, and saw at once that it represented the nearest and most dangerous holdout of the enemy. Already it was breathing fire at its crest, like a miniature volcano about to erupt, and spitting showers of Mausers. The bullets came whisking through the grass with vicious effectiveness as the Rough Riders crawled nearer. Every now and again a trooper would leap involuntarily into the air, then crumple into a nerveless heap.102 Roosevelt remained obstinately on horseback, determined to set an example of courage to his men. Now began the worst part of the battle. While the Rough Riders took what cover they could, in bushes and banks below the hill, and in the mosquito-bogs at the edge of the creek, other cavalry regiments fought their way slowly into specified positions to left and right and—humiliatingly—in front of them. The truth was that Roosevelt and his men were being held in reserve by General Sumner,103 and the new Colonel did not like it one bit. The 1st, 3rd, 6th, and even the black 9th had prior claim to this hill, while General Kent’s Infantry Division was awarded the supreme prize of San Juan Hill, now half a mile away on the left front. Orders were orders; Roosevelt could only scrawl an angry note to the (very senior) colonel of his immediate neighbors, the 10th Cavalry. “There is too much firing. Colonel Wood directs that there be no more shooting unless there is an advance.…”104 It is doubtful Wood said any such thing.

Mere spleen could not last through the one and a half hours of military torture that followed. General Sumner was waiting for orders to advance from General Shafter, but General Shafter assumed that any damn fool capable of leading a division would know when to do so without authority. Until this slight misunderstanding was cleared up, the cavalry regiments had to lie in stifling heat and try to stop as few Mausers as possible.105 Morale sagged as the shrieking projectiles chugged into groins, hearts, lungs, limbs, and eyes.106 Even Roosevelt found it prudent, in this killing hailstorm, to get off his horse and lie low; but Bucky O’Neill insisted on strolling up and down in front of his troop, smoking his perpetual cigarette, as if he were still walking along the sidewalk in Prescott, Arizona. “Sergeant,” he said to a protester, “the Spanish bullet isn’t made that will kill me.” He had hardly exhaled a laughing cloud of smoke before a Mauser shot went z-z-z-z-eu into his mouth, and burst out the back of his head. “The biggest, handsomest, laziest officer in the regiment” was dead by the time he hit the ground.107

It was now well past noon, and the insect-like figures of General Kent’s infantry could be seen beginning a slow, toiling ascent of San Juan Hill. Roosevelt sent messenger after messenger to General Sumner, imploring permission to attack his own hill, and was just about to do so unilaterally when the welcome message arrived: “Move forward and support the regulars in the assault on the hills in front.”108 It was not the total advancement he had been hoping for, but it was enough. “The instant I received the order I sprang on my horse, and then my ‘crowded hour’ began.”109

![]()

SOLDIERS ARE APT TO recollect their wartime actions, as poets do emotions, in tranquillity, imposing order and reason upon a dreamlike tumult. Roosevelt was honest enough to admit, even when minutely describing his charge up the hill, that at the time he was aware of very little that was going on outside the orbit of his ears and sweat-fogged spectacles.110 It was as if some primeval force drove him. “All men who feel any power of joy in battle,” he wrote, “know what it is like when the wolf rises in the heart.”111

Yet enough original images, visual and auditory, survive in Roosevelt’s written account of the battle to give a sense of the rush, the roar, the pounce of that vulpine movement.112 To begin with, there was the sound of his own voice rasping and swearing as he cajoled terrified soldiers to follow him. “Are you afraid to stand up when I am on horseback?” Then the sight of a Rough Rider at his feet being drilled lengthwise with a bullet intended for himself. Next, line after line of cavalry parting before his advance, like waves under a Viking’s prow. The puzzled face of a captain refusing to go farther without permission from some senior colonel, who could not be found.

Roosevelt: “Then I am the ranking officer here and I give the order to charge.” Another refusal. Roosevelt: “Then let my men through, sir.” Grinning white faces behind him; black men throwing down a barbed wire fence before him. A wave of his hat and flapping blue neckerchief. The sound of shouting and cheering. The sound of bullets “like the ripping of a silk dress.” Little Texas splashing bravely across a stream, galloping on, and on, up, up, up. Another wire fence, forty yards from the top, stopping her in her tracks. A bullet grazing his elbow. Jumping off, wriggling through, and running. Spaniards fleeing from the hacienda above. Only one man with him now: his orderly, Bardshar, shooting and killing two of the enemy. And then suddenly a revolver salvaged from theMaine leaping into his own hand and firing: a Spaniard not ten yards away doubling over “neatly as a jackrabbit.” At last the summit of the hill—his and Bardshar’s alone for one breathless moment before the other Rough Riders and cavalrymen swarmed up to join them. One final incongruous image: “a huge iron kettle, or something of the kind, probably used for sugar-refining.”113

![]()

AS HIS HEAD CLEARED and his lungs stopped heaving, Roosevelt found that Kettle Hill commanded an excellent view of Kent’s attack on San Juan Hill, still in progress across the valley about seven hundred yards away. The toiling figures seemed pitifully few. “Obviously the proper thing to do was help them.”114 For the next ten minutes he supervised a continuous volley-fire at the heads of Spaniards in the San Juan blockhouse, until powerful Gatlings took over from somewhere down below, and the infantry on the left began their final rush.115 At this the wolf rose again in Roosevelt’s heart. Leaping over rolls of wire, he started down the hill to join them, but forgot to give the order to follow, and found that he had only five companions. Two were shot down while he ran back and roared imprecations at his regiment. “What, are you cowards?” “We’re waiting for the command.” “Forward MARCH!”116 The Rough Riders willingly obeyed, as well as members of the 1st and 10th Cavalry. Again Roosevelt pounded over lower ground under heavy fire; again he surged up grassy slopes, and again he saw Spaniards deserting their high fortifications. To left and right, all along the crested line of San Juan Heights, other regiments were doing the same. “When we reached these crests we found ourselves overlooking Santiago.”117

![]()

UNTIL NIGHT FELL, Roosevelt was more interested in looking at the carnage behind him than ahead at the prize city. The trenches were filled with corpses in light blue and white uniforms, most of them with “little holes in their heads from which their brains were oozing”118—proof of the killing accuracy of Rough Rider volleys from the top of Kettle Hill. “Look at all these damned Spanish dead!” he exulted to Trooper Bob Ferguson, an old family friend.119

Official tallies revealed a fair score of American casualties—656 according to one count, 1,071 according to another. The Rough Riders contributed 89, but this only increased Roosevelt’s sense of pride; he noted that it was “the heaviest loss suffered by any regiment in the cavalry division.”120

“No hunting trip so far has ever equalled it in Theodore’s eyes,” Bob Ferguson wrote to Edith. “It makes up for the omissions of many past years … T. was just revelling in victory and gore.”121

Roosevelt’s exhilaration at finding himself a hero (already there was talk of a Medal of Honor)122 and, by virtue of his two charges, senior officer in command of the highest crest and the extreme front of the American line, was so great that he could not sit, let alone lie down, even in the midst of a surprise bombardment at 3:00 A.M. A shell landed right next to him, besmirching his skin with powder, and killing several nearby soldiers; but he continued to strut up and down, “snuffing the fragrant air of combat,”123silhouetted against the flares like a black lion rampant.

“I really believe firmly now they can’t kill him,” wrote Ferguson.124

![]()

SO BEGAN THE SIEGE of Santiago. It was not accomplished without considerable further bloodshed, for the Spanish were found to have retreated only half a mile, albeit downhill, and their retaliatory shells did much damage during the next few days. The city proper was stiffly fortified, with five thousand troops and a seemingly inexhaustible stock of heavy ammunition. Meanwhile the thin blue and khaki line cresting San Juan Heights grew thinner as wounds, malarial fever, and dysentery reduced more and more men to shivering incapacity, and often death. It took less than forty-eight hours for Roosevelt to become desperate should Shafter decide to withdraw for lack of personnel and supplies. Siboney was still clogged with unlisted crates, and each day’s rain made it more difficult to haul wagons along the Camino Real. “Tell the President for Heaven’s sake to send us every regiment and above all every battery possible,” he scribbled to Henry Cabot Lodge. “We are within measurable distance of a terrible military disaster.”125

On the same day Shafter, blustering out of sheer panic, sent a warning to General José Toral, of the city garrison:

I shall be obliged, unless you surrender, to shell Santiago de Cuba. Please inform the citizens of foreign countries, and all women and children, that they should leave the city before 10 o’clock tomorrow morning.126

Toral’s response was to admit a further 3,600 Spanish troops who had somehow managed to elude a watch force of insurrectos to the north of the city. That afternoon, while the U.S. Army sweated and sickened in its muddy trenches along the Heights, hostilities suddenly broke out in Santiago Harbor. Admiral Cervera’s imprisoned ironclads attempted to rush Admiral Sampson’s blockade, with suicidal results. By 10:00 P.M. Shafter was able to inform Washington, “The Spanish fleet … is reported practically destroyed.” He promptly demanded surrender of the city. Toral replied that a truce might be possible.127

There followed a week of uneasy cease-fire as delicate negotiations went on, designed to ensure the capitulation of Santiago at no harm to Spanish honor. On 4 July, bands along the Heights tried to enliven matters with a selection of patriotic tunes (the Rough Riders ensemble contributing “Fair Harvard”), but the music had no charms for men sitting in mud, and it soon died away on the still morning air.128

General Toral’s dignity was saved by an ingenious compromise worked out on 15 July. The Santiago garrison would surrender in two days if His Excellency, the Commander in Chief of the American forces, would kindly bombard the city (shooting at a safe height above the houses), until all Spanish soldiers had handed in their arms. They might thus be truthfully said to have capitulated under fire.129 That night the air shook convincingly all over Santiago, and on Sunday, 17 July, the Stars and Stripes was hauled up the palace flagpole, just as church bells rang in the hour of noon.130 It was time for Spain to begin her withdrawal from Cuba, after four centuries of imperial dominion in the New World. But first, lunch, wine, and siesta.

![]()

ON MONDAY, 18 JULY, Colonel Theodore Roosevelt—the title was official now131—marched with the Cavalry Division over San Juan Hill to a camping ground on the foothills west of El Caney. The move away from the stinking, mosquito-filled trenches was deemed essential because of yellow fever. Already more than half the Rough Riders were, in Roosevelt’s words, “dead or disabled by wounds and sickness.” But the mosquitoes inland were just as poisonous as those nearer the coast, and his sick list lengthened.132

Although mildly diverted by the “curious” fact that “the colored troops seemed to suffer as heavily as the white,”133 he did not leave the problem to medics or the commissariat. His men must eat and build up their strength for another possible campaign in PuertoRico. Accordingly he sent a pack-train into Santiago with instructions to buy, at his expense, whatever “simple delicacies” they could find to supplement the nauseating rations in camp. One Rough Rider claimed that Roosevelt spent $5,000 in personal funds during the next few weeks—an exaggeration no doubt, but it at least indicates the extent of his generosity and concern.134

As for himself, he remained healthy and strong as ever—so much so that he proposed to swim in the Caribbean one day with Lieutenant Jack Greenway.135 The two officers had been invited to Morro Castle by General Fitzhugh Lee, and Roosevelt’s attention was drawn to the wreck of the Merrimac, some three hundred yards out to sea. It would be fun, he said, pulling off his clothes, to go out and inspect her.

What a colonel suggested, a lieutenant was bound to obey, and Greenway reluctantly agreed to accompany Roosevelt into the water.

We weren’t out more than a dozen strokes before Lee, who had clambered up on the parapet of Fort Morro, began to yell.

“Can you make out what he’s trying to say,” the old man asked, punctuating his words with long, overhand strokes.

“Sharks,” says I, wishing I were back on shore.

“Sharks,” says the colonel, blowing out a mouthful of water, “they” stroke “won’t” stroke “bite.” Stroke. “I’ve been” stroke “studying them” stroke “all my life” stroke “and I never” stroke “heard of one” stroke “bothering a swimmer.” Stroke. “It’s all” stroke “poppy cock.”

Just then a big fellow, probably not more than ten or twelve feet long, but looking as big as a battleship to me, showed up alongside us. Then came another, till we had quite a group. The colonel didn’t pay the least attention.…

Meantime the old general was doing a war dance up on the parapet, shouting and standing first on one foot and then on the other, and working his arms like he was doing something on a bet.

Finally we reached the wreck and I felt better. The colonel, of course, got busy looking things over. I had to pretend I was interested, but I was thinking of the sharks and getting back to shore. I didn’t hurry the colonel in his inspection either.

After a while he had seen enough, and we went over the side again. Soon the sharks were all about us again, sort of pacing us in, as they had paced us out, while the old general did the second part of his war dance. He felt a whole lot better when we landed, and so did I.136

![]()

ON 20 JULY, Roosevelt found himself in command of the whole 2nd Brigade. This elevation was due to medical attrition in the higher ranks, rather than his heroism at San Juan, but it was flattering nevertheless. So, too, was the growing flood of letters and telegrams from New York, urging him to consider running for the governorship in the fall. He replied politely that he would not think of quitting his present position—“even for so great an office”—at least “not while the war is on.”137 With preparations for a peace treaty already well under way, the implication of acceptance was obvious, and plots were laid by various Republican groups to entrap him the moment he stepped ashore in the United States.138

![]()

AT THIS POINT Roosevelt’s old genius for political publicity reasserted itself. On or about the last day of July, General Shafter called a conference of all division and brigade commanders to discuss the health situation. All agreed that it was critical, and that the War Department’s apparent unwillingness to evacuate the Army was inexcusable. Somebody must write a formal letter stating that in the unanimous opinion of the Fifth Corps staff, a further stay in Cuba would be to the “absolute and objectless ruin” of the fighting forces.139

Having reached this agreement, the Regular officers hesitated. None wished to sacrifice his career by offending Secretary Alger or President McKinley. As the conference’s junior officer and a Volunteer, Roosevelt was nudged, or more probably leaped, into the breach. The result was a “round-robin” letter, drafted by himself, and signed by all present, dated 3 August 1898, and handed to the Associated Press.140

We, the undersigned officers … are of the unanimous opinion that this Army should be at once taken out of the island of Cuba and sent to some point on the Northern seacoast of the United States … that the army is disabled by malarial fever to the extent that its efficiency is destroyed, and that it is in a condition to be practically entirely destroyed by an epidemic of yellow fever, which is sure to come in the near future.…

This army must be moved at once, or perish. As the army can be safely moved now, the persons responsible for preventing such a move will be responsible for the unnecessary loss of many thousands of lives.141

The document, accompanied by a long and even stronger letter of complaint signed by Roosevelt alone, was published next morning. As predicted, Secretary Alger was enraged. So, too, was the President, whose first inkling of the round-robin came when he opened his morning papers.142 There were muttered threats in the War Department of court-martialing Roosevelt. Alger vengefully published an earlier letter from Roosevelt to himself, bragging that “the Rough Riders … are as good as any regulars, and three times as good as any State troops.”143

This was a telling blow to any aspiring Governor of New York State. An instant storm of criticism blew up in the press. The Journal accused Roosevelt of “irresistible self-assertion and egotism,” ill-suited to his “really admirable services in the field.” ThePhiladelphia Press remarked that in view of “intense indignation” among the militia, it was unlikely that the New York Republican party could now nominate Theodore Roosevelt for Governor. But many newspapers found equal fault with Secretary Alger, and charged him with treachery in publishing a private letter. The Colonel could surely be excused his overweening pride in his regiment, commented the Baltimore American; after all, “he led these men in one of the noblest fights of the century.”144

Within three days Shafter’s army was ordered to Montauk, Long Island.145

The Rough Riders sailed out of Santiago Harbor on 8 August, leaving Leonard Wood behind as Military Governor of the city. They were not sorry to see Cuba sink into the sea behind them. In seven weeks of sweaty, sickly acquaintance with it, they had seen it transformed from a tropical Garden of Eden to a hell of denuded trees, cindery fields, and staring shells of houses.146 The island’s bugs were in their veins, the smell of its dead in their nostrils, the taste of its horse meat and fecal water in their mouths. It would be days before the Atlantic breezes, cooling and freshening as they steamed north, swept away this sense of defilement.

Yet the farther Cuba dropped away, the brighter shone the memory of their two great battles—in particular that rush up Kettle Hill behind the man with the flying blue neckerchief. They had done something which orthodox military strategists considered impossible, namely, stormed and captured a high redoubt over open ground, using weapons inferior to, and fewer than, those of a securely entrenched enemy.147 In doing so they had been the first to break the Spanish defenses; charging on, they had been first to take and hold the final crest overlooking Santiago.

For Roosevelt himself, the “crowded hour” atop San Juan Heights had been one of absolute fulfillment. “I would rather have led that charge … than served three terms in the U.S. Senate.” And he would rather die from yellow fever as a result than never to have charged at all. “Should the worst come to the worst I am quite content to go now and to leave my children at least an honorable name,” he told Henry Cabot Lodge. “And old man, if I do go, I do wish you would get that Medal of Honor for me anyhow, as I should awfully like the children to have it, and I think I earned it.”148

With fulfillment came purgation. Bellicose poisons had been breeding in him since infancy. During recent years the strain had grown virulent, clouding his mind and souring the natural sweetness of his temperament. But at last he had had his bloodletting. He had fought a war and killed a man. He had “driven the Spaniard from the New World.” Theodore Roosevelt was at last, incongruously but wholeheartedly, a man of peace.