From the contending crowd, a shout,

A mingled sound of triumph and of wailing.

![]()

IT WAS MONDAY, 15 August 1898. All morning the crowd scattered across the sands of Montauk Point grew larger, as the troopship Miami wallowed at anchor three miles out to sea. Soldiers and civilians, women and children, reporters and Red Cross staff squinted over the water, wondering when the Rough Riders would be allowed to disembark. While they waited, a westerly breeze snapped the sails of yachts in the harbor, and swished through the pines of Whithemard Headland.1 It was this prevailing wind that had determined the selection of Montauk Point as the mustering-out camp for General Shafter’s army. Presumably it would blow away whatever yellow-fever bacilli lingered among the troops—wafting them somewhere in the direction of Spain.

Not until nearly noon did the tugs bring Miami in, and nudge her sideways against the pier. The crowd peered eagerly at the deep rows of soldiers on board, searching in vain for a hero to recognize. Presently two spectacle-lenses flashed like prisms at the end of the bridge, and “a big bronzed-faced man in a light brown uniform”2 was seen waving his campaign hat. A hundred voices delightedly roared “Roosevelt! Roosevelt! Hurrah for Teddy and the Rough Riders!” Beside him somebody made out a whiskery little general in blue. “Hurrah for Fighting Joe!”3

“I shall never forget the lustre that shone about him.”

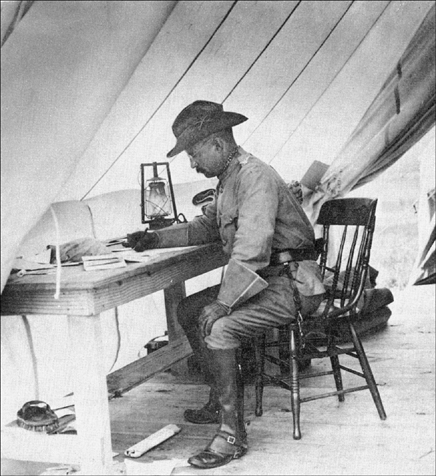

Colonel Roosevelt preparing to muster out at Camp Wikoff, Montauk, L.I. (Illustration 26.1)

While sailors made the ship fast, an officer on the pier shouted, “How are you, Colonel Roosevelt?” The reply came back in a voice audible half a mile away: “I am feeling disgracefully well!”

There was a pause while Roosevelt allowed the crowd to study the dozens of emaciated faces elsewhere on deck. “I feel positively ashamed of my appearance,” he went on, “when I see how badly off some of my brave fellows are.” Another pause. Then: “Oh, but we have had a bully fight!”4

Laughter and cheers spread from ship to shore and back again.

![]()

A QUARTER OF AN HOUR LATER General Wheeler stepped onto the soil of Long Island, toting a Spanish sword so long and heavy its scabbard dragged on the ground. He received a tumultuous welcome, but, to quote Edward Marshall, “when ‘Teddy and his teeth’ came down the gangplank, the last ultimate climax of the possibility of cheering was reached.”5

Roosevelt’s appearance at close range showed that his claims of rude health were not exaggerated. Three months of hunger, thirst, heat, mud, and execrable food—not to mention that most arduous of human activities, infantry fighting—had not thinned him; if anything, he looked thicker and stronger than when he entrained for San Antonio. He wore a fresh uniform with gaiters and scuffed boots. A cartridge belt encircled his waist, and a heavy revolver thumped against his hip as he “fairly ran” the last few steps onto the dock.6

Roosevelt was courteous to the official welcoming party—doffing his hat and bowing to the women on line—but out of the corner of his eye he caught sight of a group of newspapermen, and soon made his way over to them.

“Will you be our next Governor?” a voice cried.

“None of that … All I’ll talk about is the regiment. It’s the finest regiment that ever was, and I’m proud to command it.”7

While he talked, the Rough Riders were disembarking. To the horror and sympathy of the crowd, they appeared barely able to line up on the dock, let alone march over the hill to Camp Wikoff, a mile or so inland. Their ranks were pitifully decimated. “My God,” said one witness, “there are not half of the men there that left.”8

Roosevelt was enjoying his conversation with the press so much that he paid little attention to the movement of soldiers behind him. His face radiated happiness as he described the feats of the Army’s “cracker-jack” regiment, and of himself as its Colonel. “This is a pistol with a history,” he said, fondling his revolver affectionately. “It was taken from the wreck of the Maine. When I took it to Cuba I made a vow to kill at least one Spaniard with it, and I did.…”9

![]()

WELL MIGHT HE be happy. Theodore Roosevelt had come home to find himself the most famous man in America—more famous even than Dewey, whose victory at Manila had been eclipsed (if temporarily) by the successive glories of Las Guásimas, San Juan, Santiago, and the round-robin which “brought our boys back home.”10 The news that the United States and Spain had just signed a peace initiative came as a crowning satisfaction. Intent as Roosevelt might be to parry questions about his gubernatorial ambitions—thereby strengthening rumors that he had already decided to run—his days as a soldier were numbered.11 It remained only to spend five days in quarantine, and a few weeks supervising the demobilization of his regiment, before returning to civilian life and claiming the superb inheritance he had earned in Cuba.12

Shortly before two o’clock the Colonel strode onto the beach, where the Cavalry Division had formed in double file, and mounted a horse beside General Wheeler. Color Sergeant Wright hoisted the ragged regimental flag, the band crashed out a march, and the Rough Riders trooped off to detention.13

![]()

MEANWHILE, AT THE OPPOSITE end of Long Island, the man whose power it was to nominate, or not to nominate, Roosevelt for Governor sat pondering the state political situation. Senator Thomas Collier Platt was taking his annual vacation at the Oriental Hotel on Sheepshead Bay.14 He had been aware since at least 20 July that various groups of Republicans were working up a “Roosevelt boom,” but not until yesterday, 14 August, had two trusted lieutenants approached him formally on the subject. These men were Lemuel Ely Quigg, Roosevelt’s backer for Mayor in 1894, and Benjamin B. Odell, Jr., chairman of the Republican State Committee. Since Quigg was, in turn, chairman of the New York County Committee, and as forceful as Odell was stubborn, Platt had no choice but to listen while they pleaded the cause of the man he still regarded as “a perfect bull in a china shop.”15

The Easy Boss knew that something drastic would have to be done to prevent the renomination, at the State Republican Convention in September, of Frank S. Black, New York’s present Governor. Black was a faithful protégé whose record victory in 1896 had covered Platt with glory; but he was also anathema to Republican Independents, who accused him, rather unjustly, of gross spoilsmanship in office.16 This negative reputation might be counterbalanced by positive support for Black in upstate rural areas, were it not for a new scandal which redounded to the Governor’s discredit. On 4 August a special investigative committee had reported on “improper expenditures” of at least a million dollars in the state’s stalled Erie Canal Improvement project.17 With the entire multimillion-dollar appropriation already spent, and less than two-thirds of the canal deepened, Platt was severely embarrassed. If he supported Black’s bid for reelection he would lay himself and the party open to charges of cynicism and irresponsibility—even though the Governor had not been personally involved in the scandal. If, on the other hand, Platt dropped Black, it would be tantamount to admitting that there had been high-level corruption.18

Platt weighed his alternatives, and chose the second, seeing it as the only way he might avoid a Democratic landslide in November. He agreed to let Quigg sound Roosevelt out, but made it clear that the Rough Rider was not his preference for the nomination. “If he becomes Governor of New York, sooner or later, with his personality, he will have to be President of the United States … I am afraid to start that thing going.”19

![]()

QUIGG, HOWEVER, was not the first kingmaker to visit Roosevelt at Montauk. On Thursday, 18 August, John Jay Chapman, one of the Independent party’s fiercest and brightest idealists, walked up Camp Wikoff’s Rough Rider Street in search of the Colonel.20

Tall, hook-nosed, flamboyantly scarfed even in the hottest weather, Chapman was a man of near-manic passions, both romantic and intellectual. As testimony to the former, he would brandish the stump of a missing left hand, which he had deliberately burned to a cinder as self-punishment during a stormy love affair.21 Like Theodore Roosevelt, his friend of many years, he was well-born, Harvard-educated, and drawn equally to politics and literature (his Emerson and Other Essays had won the high praises of Henry James).22 But there the resemblance ended. Chapman could neither compromise, nor join, nor lead; he was a savage loner, fated to work outside the party, a thinker whose pure ideology was unsmirched by practical considerations. Normally Roosevelt despised such people, but Chapman, four years his junior, had such courage and charm as to be permitted the supreme familiarity of “Teddy.”23

It so happened that in August 1898 Chapman was for the first and only time in his life on the verge of real political power—if he could only persuade Roosevelt to run for Governor on an Independent ticket. The Colonel’s popularity, he reasoned, was so great as to seduce large numbers of Republican voters, and would force Boss Platt to nominate him as well, in order to keep those voters within the party. Roosevelt would thus head two tickets, followed on the one by a list of “decent, young Independents” and on the other by machine Republicans. The majority of the electorate, given such a choice, would surely prefer to send Roosevelt to Albany in virtuous company.24

It was a beautiful plan, at least in Chapman’s enthusiastic opinion. Roosevelt would be almost assured the Governorship, with all voters who were not Democrats united in his favor; the Independents would at one stroke broaden their narrow power base (at present confined largely to the Citizens’ Union and Good Government Clubs in New York City) to encompass the whole state; and most important of all, Boss Platt’s machine would be destroyed.25

Chapman was so sure of himself he allowed Roosevelt “a week to think it over.”26 The Colonel, who had everything to gain as a gubernatorial prospect by remaining silent, accepted this offer with the equanimity of one of his favorite fictional characters, Uncle Remus’s Tar Baby.

![]()

THE FOLLOWING DAY Lemuel Quigg arrived.27 Sleek, suave, prematurely gray on either side of his center parting, he made a noticeable contrast to his Independent rival. Yet the language he spoke was equally sweet to Roosevelt’s ears.

Quigg “earnestly” hoped to see the Colonel nominated, “and believed that the great body of Republican voters so desired.” He and Odell were “pestering” Senator Platt to that effect, but before they pestered further they would have to have “a plain statement” as to whether or not Roosevelt wanted the nomination.28

Roosevelt said that he did. But, in view of the fact that Quigg had made no formal offer, this should not be considered a formal reply. He promised, nevertheless, that once in power he would not “make war on Mr. Platt or anybody else if war could be avoided.” As a Republican Governor, he would naturally work with the Republican machine, “in the sincere hope that there might always result harmony of opinion and purpose.” He reserved the right, however, to consult with whom he pleased, and “act finally as my own judgment and conscience dictated.”

Quigg replied that he had expected just such an answer, and would transmit it to Senator Platt.29

![]()

HAVING THUS AUTHORIZED two secret nomination campaigns (and given tacit approval to the manufacture of ten thousand “Our Teddy for Our Governor” buttons), Roosevelt was free to leave Camp Wikoff on 20 August for a five-day reunion with his family.30 He smilingly refused to discuss his future with reporters. “Now stop it. I will not say a word about myself, but I will talk about the regiment forever.”31 As a result of this strategy he kept himself in the headlines, while avoiding all political complications. “He is playing the game of a pretty foxy man,” said a worried Democratic campaign official.32

His trip to Oyster Bay was carefully timed to coincide with the Republican State Committee meeting in Manhattan. This preconvention assemblage enabled Senator Platt to weigh the relative strengths of Black, Roosevelt, and other potential candidates for the nomination. According to Quigg, the Easy Boss was impressed by reports of Roosevelt enthusiasm in Buffalo and Erie County, which traditionally acted as a pivot between Democratic New York City and the Republican remainder of the state. Informal polls of the thirty-four committeemen showed a large majority in favor of the Colonel.33 Platt was noncommittal after the meeting, but reporters were quick to infer that Roosevelt would be the party’s eventual choice.

At eight o’clock that evening, just as New Yorkers were reading the first reports of Platt’s conference, Roosevelt arrived in Oyster Bay amid such bedlam as the little village had never known in its two and a half centuries of existence. Church bells pealed, rockets shot up, cannons and musketry exploded in salute as his train pulled into the station with whistle wide open. The war hero hung out of his window waving his Rough Rider hat, grinning and glowing in the light of a celebratory bonfire. A red, white, and blue banner slung across Audrey Avenue proclaimed the words WELCOME, COLONEL! and fifteen hundred people yelled greetings to “Teddy.”34

When Roosevelt stepped out onto the platform he was seen to be accompanied by his wife. Edith had gone to Montauk to greet him privately beforehand, and she stood flinching now as the crowd surged forward. This coarse grabbing and grasping, these howls of the detested nickname, presaged ill for whatever hopes she may have had for a quiet return to domestic life at Sagamore Hill. Like it or not, she had to accept that Theodore was now public property. Dreadful as the prospect might have seemed to her, she braced herself for it with all her considerable strength. Smiling and outwardly calm, she followed the Rough Rider as he fought toward their waiting two-seater. Not a few admiring glances followed her. For the rest of his life Roosevelt would have to suffer a ritual greeting whenever he returned to Oyster Bay: “Teddy, how’s your ’oman?”35

![]()

HE SPENT THE NEXT FEW DAYS enjoying the forgotten delights of civilization: cool summer clothes, good food, the conversation of women and children, hot water, clean sheets, green lawns, birdsong. Every night he changed into a tuxedo for dinner and joined his family and guests on the piazza overlooking Long Island Sound. Toying with a glass of Edith’s old Madeira, he gazed at the passing lights of pleasure craft and Fall River steamers, and told over and over again to all who would listen the stories of Las Guásimas and San Juan Hill.36

A particularly interested auditor was Robert Bridges, editor of Scribner’s. Four months before, when the Rough Riders were still organizing at San Antonio, Roosevelt had offered Bridges “first chance,” ahead of Century and Atlantic, for the publication of his war memoirs. He suggested that this “permanent historical work” should appear first as a six-part magazine series, beginning in the New Year of 1899.37 Bridges had accepted with alacrity. Now the editor was pleased to discover that Roosevelt already had the book “blocked out.” Not a line had been written, but the Colonel’s diary contained scraps of choice dialogue, and the stories he was telling on the piazza were obviously being tested for popular appeal. Bridges expressed concern that politics might delay Roosevelt’s reentry into literature, but the author was supremely confident. “Not at all—you shall have the various chapters at the time promised.”38

On the morning of 24 August, Roosevelt’s last before returning to Camp Wikoff, he was waited upon a second time by John Jay Chapman. The Independent leader, who was accompanied by Isaac Klein of the Citizens’ Union, requested an answer to his proposal of 18 August. Roosevelt, feeling his power, said he would run as a party regular or not at all. But if the Republicans did honor him with their nomination on 27 September, he would be happy to accept that of the Independents afterward as an “endorsement.” He had no objections to the Independents making a preliminary announcement of his acceptance, as long as it was accompanied by a statement of his own making clear the stipulations involved.39

This, of course, was all that Chapman and Klein wanted. They happily returned to New York to begin work on a provisional ticket. Chapman had always admired Roosevelt, in the way thinkers follow doers, but now the admiration deepened into reverence. “I shall never forget the lustre that shone about him … my companion accused me of being in love with him, and indeed I was. I never before nor since have felt that glorious touch of hero worship.… Lo, there, it says, Behold the way! You have only to worship, trust, and support him.”40

Every day brought new indications that Roosevelt was the coming man of Republican politics, not only in New York State, but across the country as well. National committeemen, Senators, and representatives of far-flung party organizations urged him to run for Governor, and begged his services as a campaign speaker.41 An envelope adorned with nothing but a crude sketch of him in military uniform was delivered to Oyster Bay, along with sackfuls of other mail.42 In Chicago several Union Leaguers announced the formation of the “Roosevelt 1904 Club,” proclaiming him as the natural successor to President McKinley when that popular executive stepped down after another term. There were some who whispered that he might run, and win, against the President in 1900.43

Roosevelt, perhaps remembering his too-rapid boom in the New York mayoralty campaign, announced that he would return to Montauk twelve hours early, on 25 August. He was still an Army officer, not a politician, and “I feel that my place is with the boys.”44

There followed a week of silence and secrecy while the Colonel nursed his regiment back to health and strength, and Boss Platt’s pollsters sounded out opinions on Roosevelt v. Black. One of these pollsters was Isaac Hunt, the gangling reformer of Roosevelt’s Assembly days. He reported that only one Republican delegate in three would vote for Black. “Ike,” said Platt, “I have sent men all over this state; your report and theirs correspond.”45

On 1 September, the Easy Boss allowed the first news leaks indicating that he personally favored Roosevelt’s nomination. E. L. Godkin of the Post chortled over the prospect of two such ill-matched bedfellows coyly climbing into their pajamas. “The humorous possibilities of such a situation are infinite.”46

Chapman and Klein hurried to Montauk for reassurances that Roosevelt would not “take our nomination and then later throw us down by withdrawing from the ticket.” The Colonel’s response appears to have been guarded, yet positive enough for Chapman towrite on Sunday, 4 September: “We expect to put Roosevelt in the field [soon] at the head of a straight Independent ticket.”47

![]()

ON THE SAME DAY at Camp Wikoff there occurred a symbolic incident highly pleasing, no doubt, to the Roosevelt 1904 Club. President McKinley arrived at Montauk railroad station on a mission of thanks to Shafter’s victorious army. As he settled into his carriage with Secretary Alger, he caught sight of a mounted man grinning at him some twenty yards away. “Why, there’s Colonel Roosevelt,” exclaimed McKinley, and called out, “Colonel! I’m glad to see you!”

Secretary Alger manifestly was not, but this did not prevent the President from making an extraordinary public gesture. He jumped out of the carriage and walked toward Roosevelt, who simultaneously tumbled off his horse with the ease of a cowboy. In the words of one observer:

The President held out his hand; Col. Roosevelt struggled to pull off his right glove. He yanked at it desperately and finally inserted the ends of his fingers in his teeth and gave a mighty tug. Off came the glove and a beatific smile came over the Colonel’s face as he grasped the President’s hand. The crowd which had watched the performance tittered audibly. Nothing more cordial than the greeting between the President and Col. Roosevelt could be imagined. The President just grinned all over.

“Col. Roosevelt,” he said, “I’m glad indeed to see you looking so well.”

Before McKinley reentered the carriage Roosevelt made him promise to visit “my boys.”48

![]()

THE COLONEL CONTINUED to juggle, expertly but dangerously, with the two balls tossed him by Chapman and Quigg. When, on 10 September, the former publicly praised Roosevelt as one “who in his person represents independence and reform,” Roosevelt himself announced, by proxy, that he was “a Republican in the broadest sense of the word.” He confirmed for the first time that he would accept, but not seek, nomination by his regular party colleagues. Any subsequent nomination by the Independents would of course be “most flattering and gratifying.”49

To make his position doubly clear, at least to himself, he wrote two letters on 12 September, one to Quigg defining the conditions on which he would accept nomination, the other to the Citizens’ Union saying that a new statement that he was still available as an Independent candidate was “all right.” The warmth and length of the first letter (thirty-six lines) compared with the curt brevity (two lines) of the second left no doubt as to where his true hopes and sympathies lay.50 However neither recipient could make this comparison at the time, and both continued to work for Roosevelt’s nomination.

![]()

THE FOLLOWING DAY, Tuesday, 13 September, was a poignant one for Roosevelt. Demobilization work was complete, and the Rough Riders prepared to muster out, troop by troop. Although the regiment’s life had been short—a mere 133 days from formation to dissolution—its rise had been meteoric, leaving an incandescent glow in the hearts of its nine hundred surviving members. Civilian life seemed a dull, even dismal prospect to those who had clerkships and ranch jobs and law school to return to. Yet the glory had to come to an end. At one o’clock bugles rang through the grassy streets of Camp Wikoff, summoning the Rough Riders to their last assembly.51

Roosevelt, writing in his tent, was surprised to hear his men lining up outside. He had not expected the mustering out to begin until a little later in the afternoon. But now a group of deferential troopers ducked in out of the sunshine and requested his attendance at a short open-air ceremony.

Emerging, the Colonel found his entire regiment arranged in a square on the plain, around a table shrouded with a lumpy blanket. Nine hundred arms snapped in salute as he stood with brown face flushing. He looked around him and saw tears starting in many eyes; his own dimmed too.52 Then Private Murphy of M Troop stepped forward and announced in a choking voice that the 1st Volunteer Cavalry wished to present their commanding officer with “a very slight token of admiration, love, and esteem.” Murphy struggled to summarize the “glorious deeds accomplished and hardships endured” by the Rough Riders under Roosevelt, while the sound of sobbing grew louder on all sides of the square. “In conclusion allow me to say that one and all, from the highest to the lowest … will carry back to their hearths a pleasant remembrance of all your acts, for they have always been of the kindest.”53

The blanket was whipped away to disclose a bronze bronco-buster, sculpted by Frederic Remington. From thumping hooves to insolently waving sombrero, it was the solid remembrance of a sight seen thousands of times in camp at San Antonio and Tampa, again in Cuba when there were native horses to be rustled, and yet again in Wikoff for the benefit of visitors and envious infantrymen. Roosevelt was so overcome he could only step forward and pat the bronco’s coldly gleaming mane.54 He found his voice with difficulty, forcing the words out:

Officers and men, I really do not know what to say. Nothing could possibly happen that would touch and please me as this has … I would have been most deeply touched if the officers had given me this testimonial, but coming from you, my men, I appreciate it tenfold. It comes to me from you who shared the hardships of the campaign with me, who gave me a piece of your hardtack when I had none, and who gave me your blankets when I had none to lie upon. To have such a gift come from this peculiarly American regiment touches me more than I can say. This is something I shall hand down to my children, and I shall value it more than the weapons I carried through the campaign.55

“Three cheers for the next Governor of New York,” yelled a voice.

“Wish we could vote for him,” came the answering shout.

Roosevelt asked the men to come forward and shake his hand. “I want to say goodbye to each one of you in person.”

Company ranks were formed, and the Rough Riders began to pass by their Colonel in single file. Many cried openly as they walked away.56 “He was the only man I ever came in contact with,” confessed one private, “that when bidding farewell, I felt a handshake was but poor expression. I wanted to hug him.”57 Roosevelt had a compliment, joke, recognition, or a ready identification for every man. As he shook the slender fingers of Ivy Leaguers, the rough paws of Idaho lumberjacks, the heavy dark hands of Indian cowpunchers, Roosevelt doubtless reflected, for the umpteenth time, what a microcosm of America this regiment was—or, to use the World’s metaphor, what “an elaborate photograph of the character of its founder.”58 Here were game, bristling Micah Jenkins, “on whom danger acted like wine”; Ben Daniels of Dodge City, with half an ear bitten off; languid Woodbury Kane, looking somehow elegant in battle-stained khaki; poker-faced Pollock the Pawnee, smiling for the first and only time in the history of the regiment; and Rockpicker Smith, who had stood up in the trenches outside Santiago and bombarded “them —— Spaniels” with stones. Here, too, were dozens of troopers whom Roosevelt knew only by their contradictory nicknames: “Metropolitan Bill” the frontiersman, “Nigger” the near-albino, “Pork Chop” the Jew, jocular “Weeping Dutchman,” foul-mouthed “Prayerful James,” and “Rubber Shoe Andy,” the noisiest scout in Cuba.59

After the last tearful good-bye and promise of everlasting comradeship, Roosevelt’s Rough Riders marched off to be paid $77 apiece and discharged. By early evening the first of them were trooping into New York with wild cowboy yells. Within twenty-four hours the 1st U.S. Volunteer Cavalry was dissolved. “So all things pass away,” Roosevelt sighed to his old friend Jacob Riis. “But they were beautiful days.”60

![]()

ON SATURDAY, 17 SEPTEMBER, the Colonel (as he would continue to be called throughout his life as a private citizen) braced himself for a prenomination meeting with Senator Platt. Confident as he might be of his new political powers, it was noted that he, not Platt, crossed the gulf between them, namely the East River of Manhattan. He sneaked into the Fifth Avenue Hotel via the ladies’ entrance, shortly before three o’clock in the afternoon, looking somber in black and gray, but wearing a defiantly military hat.61

Advance word of the meeting had been leaked to the press, along with rumors that Platt was mistrustful of Roosevelt’s continued flirtation with the Independents; consequently the hotel’s main lobby was thronged with excited politicians and reporters. Anticipation rose as two hours ticked by with no word from the Amen Corner. Some pundits guessed that Platt would insist Roosevelt run as a Republican only, and that Roosevelt would agree, for the very good reason that Platt controlled some 700 of the convention’s 971 votes.62 Others said that the Colonel’s boom was already so great that Platt’s survival as party boss depended on his favor. Betting on Roosevelt v. Black ran $50 to $20 against the Governor.63

A few minutes after five o’clock Roosevelt appeared alone at the top of the grand stairway, hesitating with his habitual sense of drama until the crowd saw him and surged across the intervening space. “I had a very pleasant conversation,” he began to say, “with Senator Platt and Mr. Odell—”

An impatient voice interrupted him. “Will you accept the nomination for Governor?”

“Of course I will! What do you think I am here for?”64

![]()

THUS DID ROOSEVELT proclaim himself both a gubernatorial candidate and an orthodox Republican willing to compromise with, if not actually obey, the Easy Boss. He denied that he had been asked to withdraw from the non-partisan ticket, and the Independents bravely insisted he was still their man, but few doubted that John Jay Chapman would soon receive a “Dear Jack” letter. Sure enough, Roosevelt waited only until the mails reopened on Monday morning.

I do not see how I can accept the Independent nomination and keep good faith with the other men on my ticket. It has been a thing that has worried me greatly; not because of its result on the election; but because it seems so difficult for men whom I very heartily respect as I do you, to see the impossible position in which they are putting me.65

Chapman simply refused to believe that the hero of San Juan Hill could write anything so petulant as the last words of this letter. “I know that you are the least astute of men,” he shot back. “… I am satisfied, however, that you misapprehend the situation and that you never will decline.”66

On 22 September, Roosevelt sat down to write an icily formal reply. “Dear Mr. Chapman … It seems to me that I would not be acting in good faith toward my fellow candidates if I permitted my name to head a ticket designed for their overthrow, a ticket moreover which cannot be put up because of objections to the fitness of character of any candidates, inasmuch as no candidates have yet been nominated.”67

Was it lingering wistfulness for his own youthful idealism, mingled perhaps with sympathy for the non-partisan workers frantically canvassing upstate in his behalf, that caused him to pigeonhole this letter for three days?68 Or did he withhold it because he wished to take on as many Independent voters as possible before nudging Chapman overboard? Lack of documentation makes a definite answer impossible. Unpleasant as the latter alternative may be, it is by far the more likely. Wistfulness and sympathy were not characteristics of Roosevelt the politician; a fierce hunger for power was. Clearly, every day he could seem to cling to both nominations increased his potential strength at the convention and in the election; the longer he kept Chapman guessing, the less chance the Independents had of finding an adequate replacement.69

Whatever his motive, he patiently suffered the abuse of Chapman, Klein, and other desperate Independents. They called him a “broken-backed half-good man,” a “dough-face,” and—publicly, when he remained obdurate—the puppet of Senator Platt and “standard-bearer of corruption” in New York State. During one meeting, he allegedly “cried like a baby” and “could hardly walk when he left.”70

Chapman’s final argument with Roosevelt, at Sagamore Hill on the afternoon of 24 September, was so violent that the Colonel accused his one-armed aggressor of provoking “an able-bodied man who could not hit back.” Chapman stormed out of the house, but returned sheepishly half an hour later to say that the last train for New York had already left Oyster Bay Station. Roosevelt, amused, let him stay for the night and supplied a conciliatory toothbrush. “We shook hands the next morning at parting,” wrote Chapman, “and avoided each other for twenty years.”71

![]()

NO SOONER HAD ROOSEVELT decided that he was strong enough to run for Governor on one ticket, than a sensational private revelation threatened to destroy his candidacy overnight. On 24 September headlines in all major newspapers shouted the story:

ROOSEVELT NOT A CITIZEN OF THIS STATE

This Is the Bomb That Gov. Black and His Friends

Are Ready to Throw Into the Saratoga

Convention72

The gunpowder in Black’s bomb was an affidavit Assistant Secretary of the Navy Roosevelt had executed just six months before, at the height of his tax problems and worries about his ailing family. It stated that he had been a legal resident of Washington, D.C., since 1 October 1897, when his lease of a Manhattan town house (actually Bamie’s place at 689 Madison Avenue) came to an end. This had effectively disqualified him as a New York State taxpayer, saving him from a personalty assessment of $50,000. But it also appeared to disqualify him from the governorship of New York, since the constitution required that all candidates must be “continuous” residents of the state for at least five years prior to nomination.73

With only three days to go before the opening of the convention, Boss Platt and Chairman Odell swung into rapid, ruthless action. The party’s most eminent lawyers, including Joseph H. Choate and Elihu Root, were called in to analyze the problem. Roosevelt was ordered to stay at home and say nothing to reporters.74

The more Choate and Root looked into the case the less they liked it. Not only had Roosevelt declared himself a Washingtonian to escape taxes in New York, he had previously declared himself a New Yorker to escape taxes at Oyster Bay.75 Cynics might justifiably wonder if the Colonel had since established a residence in Santiago, in order to avoid paying any taxes anywhere.

Choate, perhaps recollecting Roosevelt’s disloyalty during his Senatorial bid in 1896, refused to “put himself on record” as to the candidate’s fitness for office.76 Root, too, was “extremely anxious and dubious” about the evidence, until Chairman Odell reminded him that Roosevelt, if elected, would almost certainly bring in a Republican Attorney General on his coattails. There would then be no risk of proceedings in quo warranto, and Roosevelt’s defense, however flimsy, would stand inviolate.77

This was the sort of reasoning that Senator Platt understood. He said that it was the best legal opinion he had heard so far.78 Roosevelt’s nomination would go forward as planned. Root must research, and if necessary invent, enough scholarly argument to reassure the Saratoga Convention that they were in fact voting for a citizen of New York State. Meanwhile he, Platt, would see to it that Root got a delegate’s seat, and be recognized as a speaker in advance of the first roll call.79

Root philosophically set to work on Roosevelt’s affidavits and covering correspondence. Analysis of the latter showed that the candidate was more sinned against than sinning; he had received foolish advice from family lawyers and accountants, despite repeated pleas to them to protect his voting rights. But the cold evidence was embarrassing. Roosevelt had definitely declared himself a resident of another state during the required period of eligibility. Root decided to prepare a brief on varying interpretations of the wordresident, mixing many “dry details” with sympathetic extracts from Roosevelt’s letters, plus a lot of patriotic “ballyhoo” calculated both to obfuscate and inspire.80

According to at least two accounts, Roosevelt was nevertheless so depressed about the tax scandal that he went to Platt and suggested that he withdraw his candidacy. “Is the hero of San Juan Hill a coward?” sneered the old man.

“By Gad! I’ll run.”81

![]()

ROOSEVELT SPENT SUNDAY, 25 September, relaxing with his family at Oyster Bay, and let it be known that he intended to stay at home through the convention. He was too tired to write more than a few lines to Henry Cabot Lodge: “I have, literally, hardly been able to eat or sleep during the last week, because of the pressure on me.”82

Conscious of his dignity as a candidate by request, he made no attempt to establish telephone or telegraph connections with the village. He lounged casually in a white flannel suit, napped after lunch, and went for a twilight stroll with Edith. Shortly after sunset the couple changed into evening dress and dined with their children. Then they adjourned to the library, where a fire was crackling, and sat waiting for the first news to come up the hill.83

![]()

AT 8:30 A MESSENGER BOY arrived on a bicycle and handed Roosevelt a telegram. It was signed by his personal representative at Saratoga.

READING BY ROOT OF TAX CORRESPONDENCE PRODUCED PROFOUND SENSATION AND WILD ENTHUSIASM. C. H. T. COLLIS

Brave, brilliant Elihu! What had the man said? But other telegrams were coming thick and fast now:

LAUTERBACH FOLLOWS ROOT AND MOST GRATEFULLY TAKES IT BACK. C. H. T. COLLIS

YOU ARE NOMINATED FOR GOVERNOR. OUR HEARTS ARE WITH YOU. CONGRATULATIONS. ISAAC HUNT—WILLIAM O’NEIL

Ike and Billy! “These two fellows,” said Roosevelt, dazedly passing the message to a reporter, “were my right and left bowers when I was in the Legislature.” He read the next telegram without comment: it came from his future running mate.

ACCEPT MY SINCERE CONGRATULATIONS UPON YOUR NOMINATION FOR GOVERNOR. MAY YOUR MARCH TO THE CAPITOL BE AS TRIUMPHANT AS YOUR VICTORIOUS CHARGE UP SAN JUAN HILL. TIMOTHY L. WOODRUFF.84

Roosevelt’s vote had been an overwhelming 753 to Black’s 218. What was more, he had won the approval of all types of constituency, whereas Black attracted mainly urban support. All this bode well for the Colonel as a popular candidate, if not for Republicans in general. He wisely did not exaggerate his chances of election. “There is great enthusiasm for me, but it may prove to be mere froth, and the drift of events is against the party in New York this year.…”85

![]()

ON 4 OCTOBER a committee featuring all the major figures in the state Republican party—with one conspicuous exception—waited upon Roosevelt at Sagamore Hill and formally notified him of his nomination. Senator Thomas C. Platt sent his regrets, saying that he was “indisposed.”86 Arthritic or not, the Easy Boss had no desire to travel as a pilgrim to the Rooseveltian shrine. Candidate and committee were to remember that the party’s spiritual center remained the Amen Corner of the Fifth Avenue Hotel.

Roosevelt, for his part, was as determined to assert his own independence. He stood grim and motionless on the piazza as Chauncey M. Depew made the customary flowery address. In reply he read from a typewritten sheet, emphasizing some phrases with particular clarity: “If elected I shall strive so to administer the duties of this high office that the interests of the people as a whole shall be conserved … I shall feel that I owe my position to the people, and to the people I shall hold myself accountable.”87

Meanwhile, in Brooklyn, another committee was notifying Judge Augustus van Wyck that he had been selected to run as the Democratic candidate for Governor.88 Although van Wyck was as obscure as Roosevelt was famous, he boasted an equally clean record, and had the added advantage of belonging to the out-of-power party in a time of corrupt status quo. Boss Richard Croker of Tammany Hall had engineered his nomination, much as Boss Platt had Roosevelt’s, yet the Democrat’s integrity could not be questioned.89By close of business that afternoon, the bookies of Broadway were offering van Wyck at 3 to 5 and finding plenty of takers; one gambler plunked down $18,000 against $30,000 on the judge.90 The only even odds, as some wag remarked, were that the next Governor would be a Dutchman.

![]()

ONE OF THE FIRST OUTSIDERS to congratulate Roosevelt was William McKinley, who sent a handwritten expression of unqualified good wishes. This letter, said party pundits, “disposed of the rumor that the President regards Colonel Roosevelt as a possible rival two years hence.”91 Yet McKinley could hardly have been reassured by Roosevelt’s first campaign speech, in Carnegie Hall on 5 October. It sounded more like the oratory of a Commander-in-Chief than plain gubernatorial rhetoric:

There comes a time in the life of a nation, as in the life of an individual, when it must face great responsibilities, whether it will or no. We have now reached that time. We cannot avoid facing the fact that we occupy a new place among the people of the world, and have entered upon a new career.… The guns of our warships in the tropic seas of the West and the remote East have awakened us to the knowledge of new duties. Our flag is a proud flag, and it stands for liberty and civilization. Where it has once floated, there must be no return to tyranny or savagery …92

“He really believes he is the American flag,” John Jay Chapman remarked in disgust.93 Senator Platt, who had strongly opposed the Spanish-American War, did not like Roosevelt’s imperialistic overtones at all. Neither did any other local party leaders. They noticed an ominous tendency of the candidate to surround himself with khaki-clad veterans, several of whom seemed determined to stump the state with him. Chairman Odell felt that a “Rough Rider campaign” would be undignified and dangerous.94 Perhaps Roosevelt should go home to Oyster Bay and let Platt’s tame newspapers conduct the election.

As a result the Colonel found himself closeted at Sagamore Hill for a period of “absolute sloth” while his managers debated how to proceed through 7 November. The news from upstate was not good.95 Voters were reported to be apathetic, as well they might be, considering the dullness of the issues. Apart from Democratic accusations of “thievery and jobbery” by Republican canal commissioners, there was little to excite the electorate one way or another. State control of excise rates and licensing fees, state management of the National Guard, state supervision of municipal election bureaus—these were not the sort of subjects to distract a fishmonger’s attention from the sporting pages.96 Indiscreet and irrelevant as Roosevelt’s Carnegie Hall address had been, it had at least drummed up a certain amount of enthusiasm. Odell began to regret silencing the candidate so hastily.

On 9 October, Governor Black suggested, in an apparently conciliatory gesture, that Roosevelt be sent to speak in Rensselaer, his own home town. Odell was tempted to agree for the sake of party unity, but hesitated until the evening of the thirteenth, when a second urgent telephone invitation came in from the coordinator of the Rensselaer County Fair. If Roosevelt paid a visit the following morning, said the caller, he would be sure of “a tremendous crowd.”97

Odell hesitated no longer. He relayed the invitation to Sagamore Hill and received a rather testy message of acceptance. It would be “inconvenient,” but Roosevelt would take the early-morning train into town.98

So began a day of the drizzly, hopeless kind all political candidates dread.99 The Colonel arose at dawn and reached New York City at eight. District Attorney William J. Youngs was waiting at Grand Central to escort him north to Albany, where Governor Black expressed the utmost surprise to see them. No advance warning of the visit had been sent, Black insisted. Due to pressure of other engagements, he unfortunately would not be able to accompany them to the fair.

Pausing only to growl that when he next came back to Rensselaer County, it would be as his own campaign manager, Roosevelt returned to the station. As his train rocked and swayed eastward to Troy, he tried to eat a few slippery oysters in the dining car. Six officials in four open carriages were waiting in the rain at Brookside Park Station. The fairground was just far enough away to ensure that Roosevelt was thoroughly soaked en route; when he arrived in front of the main grandstand he found less than three hundred persons idly leaning against the railings.

The candidate did not even deign to step down from his carriage. Five minutes after entering the fairground he left it again, and returned to the station, only to find that his train had disappeared.

![]()

NEXT MORNING, SATURDAY, as New Yorkers hooted over Roosevelt’s “wild goose chase” (Democratic newspapers saw it as a vengeful prank by Governor Black), the candidate brushed aside Odell’s apologies. With little more than three weeks to go before the election, and van Wyck gaining strength daily, it was plain that Republican strategy was not working. The campaign needed drama, and it needed an issue; he, Roosevelt, would supply both.100

Sometime during his damp peregrinations the day before, he had read a newspaper interview with Richard Croker in which the Tammany boss had made some amazingly arrogant remarks about the state judiciary. Croker said, for example, that Supreme Court Justice Daly, a respected Democrat with twenty-eight years on the bench, would be opposed by the machine in his bid for reelection. This was because he had recently refused to reappoint a Croker henchman to his staff. Tammany Hall would not endorse any judge who failed to show “proper consideration” for favors received.101

Here, in Roosevelt’s opinion, was the issue of the campaign. He knew from his youthful experiences with Jay Gould and Judge Westbrook how strongly New Yorkers felt about the corruption of the judiciary. Starting immediately, he intended to stump the state as it had never been stumped before, attacking not van Wyck, but Boss Croker, as a defiler of white ermine.102

To make sure he was seen and heard at every whistle-stop, he would take along a party of six Rough Riders in full uniform, including Color Sergeant Albert Wright as flag-waver, Bugler Emil Cassi as herald, and Sergeant “Buck” Taylor, the most garrulous man in the regiment, in case he lost his voice.103

Faced with such resolution, Odell could only agree. By the time Roosevelt’s twin-unit Special left Weehawken, New Jersey, at 10:02 on Monday morning, 17 October, his party had been enlarged to include several other aspirants to high state offices, and half a dozen newspaper correspondents.104

![]()

THE COLONEL MADE seventeen stops that day along 212 miles of the Hudson Valley. Crowds, summoned by blasts from Cassi’s bugle, were encouragingly large and enthusiastic, amounting to some twenty thousand in under twelve hours. As he leaned again and again over the rear platform of his private car, he harped on Croker’s desire to corrupt the judiciary, mixed in a few stirring calls to Empire, and made some emphatically vague promises to investigate the canal scandal. He soon found that any remark to do with the Rough Riders stimulated applause from old and young, male and female. The citizens of Newburgh were duly reminded of his volunteer status in the war; those of Albany thrilled to the story of San Juan Hill; hecklers at Glens Falls were accused of making more noise than the guerrillas of Las Guásimas.105 Back in New York, the bookies of Broadway improved their odds in Roosevelt’s favor, typically offering $25,000 at 10 to 7, and $5,000 at 5 to 3. Knowledgeable punters said that the market had yet to settle.106

During the next two days, 18 and 19 October, the Special steamed around the Adirondacks as far north as Ogdensburg on the St. Lawrence River, then curved south again via Carthage.107 Roosevelt tailored his speeches (never more than ten minutes long, and seldom repeated) to his audiences with unfailing accuracy. He spoke jerkily and harshly, squinting as though his eyes hurt, yet he radiated a strange, mesmeric power, well described by Billy O’Neil:

Wednesday it rained all day and in spite of it there were immense gatherings of enthusiastic people at every stopping place. At Carthage, in Jeff. County, there were three thousand people standing in the mud and rain. He spoke about ten minutes—the speech was nothing, but the man’s presence was everything. It was electrical, magnetic. I looked in the faces of hundreds and saw only pleasure and satisfaction. When the train moved away, scores of men and women ran after [it], waving hats and handkerchiefs and cheering, trying to keep him in sight as long as possible.

… Perhaps I measured others by my own feelings, for as the train faded away I saw him smiling, and waving his hat at the people, and they in turn giving abundant evidence of their enthusiastic affection, my eyes filled with tears. I couldn’t help it though I am ordinarily a cold-blooded fish not easily stirred like that.108

The Colonel returned to New York that evening. During the next thirty-six hours he addressed seven major meetings. His histrionic gifts were everywhere in evidence, particularly when timing his entrances. “Out of the woods came a hero,” some warm-up speaker would declaim, and infallibly Roosevelt would sweep onto the platform, waving his military hat to wild cheers.109 Or he would burst unexpectedly into a German-American Versammlung while the chairman barked, “Herr Roosevelt is here!”110 Wherever he went, Color Sergeant Wright led the way and other Rough Riders brought up the rear, as if Roosevelt were still advancing through the jungles of Cuba.111 The candidate regaled every audience with a war story or two, discreetly rearranging the facts for rhetorical effect. For example, Bucky O’Neill’s celestial musings on the bridge of the Yucatán became his “last words” at the foot of Kettle Hill, and acquired expansionist overtones: “Who wouldn’t risk his life to add a new star to the flag?”112

District leaders meeting with Roosevelt on 21 October discovered that behind the showman lurked a coldly efficient campaign strategist. He was “too strong a man to be susceptible to flattery,” asking not for “rosy” forecasts but facts as to where his campaign was weak and what could be done to strengthen it. The district leaders left Republican headquarters “enthusiastic, not so much over the Colonel’s personality as his capacity for details. He revealed himself a political fighter very much as he did in the charge of San Juan.”113

![]()

THE ROOSEVELT SPECIAL set off again that Friday afternoon on a quick swing up the Hudson and Mohawk valleys, followed on Monday by a six-day tour of central and western New York State. It was noticed that the candidate had reduced his Rough Rider escort to two—Sergeant Buck Taylor and Private Sherman Bell of Cripple Creek, Colorado—and had dressed them in mufti, possibly to avoid offending the conservative sensibilities of rural voters.114 If so, such scruples were groundless. Buck Taylor was listened to with the greatest deference en route, even at Port Jervis, when he pronounced the most resounding faux pas of the campaign:

I want to talk to you about mah Colonel. He kept ev’y promise he made to us and he will to you.… He told us we might meet wounds and death and we done it, but he was thar in the midst of us, and when it came to the great day he led us up San Juan Hill like sheep to the slaughter and so will he lead you.

“This hardly seemed a tribute to my military skill,” Roosevelt said afterward, “but it delighted the crowd, and as far as I could tell did me nothing but good.”115

Depot by depot, valley by valley, the little train toiled on through the misty countryside. Roosevelt made sixteen formal speeches that first day, nineteen the second, fourteen the third, fifteen the fourth, eleven the fifth, and fifteen the sixth, plus twelve other impromptu speeches here and there—a total of 102 in all. He hurled them out against the din of brass bands, screaming hecklers, steam whistles, fireworks, and, most deafening of all, hundreds of boot soles clapped together by employees of a shoe factory. Choking cannon fumes greeted him at Lockport and Spencerport, sooty rain sprayed into his face at Tonawanda, and the sulfurous smoke of red flares at Rome made him cough, shout, and cough again until his voice gave out entirely. He pumped the dry hands of tinkers, the greasy hands of cooks, the bandaged hands of stevedores, the sweaty hands of foundry workers. He stood patiently through countless performances of “There’ll Be a Hot Time in the Old Town Tonight” (in Middletown, two bands, one black and one white, attempted to play it in counterpoint). He suffered the traditional humiliation of having the train pull out just as he was beginning to speak. He fought off drunks and had war-bereaved mothers cry on his shoulder.116 In short, he enjoyed himself, as only the true political animal can.

And by all accounts his audiences enjoyed him. During the course of this long tour, Roosevelt so perfected his oratory that he was able at Phoenix to accomplish the most difficult trick in the actor’s book, namely, wordless persuasion. Two hundred dour farmers sat on their hands until he stopped in midspeech, leaned over the brake-handle and simply stared at them, wrinkling his face quizzically. “The first man he looked at laughed,” reported the Sun, “and the next, and the one afterward, and so on, [until] the Colonel and everyone in the crowd was laughing.”117

At Syracuse, on 27 October, Theodore Roosevelt turned forty.

![]()

TWO MORE TRAIN TOURS, of Long Island and southwestern New York, kept him raw-throated through the last hours of election eve, 7 November. Not until midnight could the candidate relax over a copy of Die Studien des Polybius as his Pullman rocked homeward.118 He felt that he had made “a corking campaign,” and if the memory of it was tarnished by rumors of $60,000 in last-minute bribes at headquarters, his own image, at least, shone brightly. “There is no denying,” the Troy Times said, “that Theodore Roosevelt has grown mightily in the public estimation since he appeared in person in the campaign.”119

The day just beginning would disclose that he had won the governorship of New York State by 17,794 votes—a narrow margin but a decisive one, given the odds of four weeks before.120 In the opinion of Chauncey Depew, who accompanied him on his six-day sweep, his victory was a triumph of sheer personality over discouraging conditions. Even Boss Platt would admit that Roosevelt was “the only man” who could have saved the party that year. Roosevelt himself was inclined in later life to ascribe his success to the decision to attack not his opponent, but the boss of his opponent.121 Yet in the first flush of victory he could only invoke fortune. “I have played it with bull luck this summer,” he wrote Cecil Spring Rice. “First, to get into the war; then to get out of it; then to get elected. I have worked hard all my life, and have never been particularly lucky, but this summer I was lucky, and I am enjoying it to the full. I know perfectly well that the luck will not continue, and it is not necessary that it should. I am more than contented to be Governor of New York, and shall not care if I never hold another office.…”122

As the last leaves fell around Sagamore Hill he began to dictate his war memoirs, inevitably called The Rough Riders. At $1,000 per serial installment (with the prospect of rich book royalties afterward), the work was the most profitable he had ever undertaken. He had also, before Christmas, to deliver eight Lowell lectures at Harvard, for a fee of $1,600; then in the New Year he could start drawing a state salary of $10,000.123 Affluence stared him in the face. All that was lacking to complete his happiness was “that Medal of Honor,” but no doubt it would be forthcoming.

“During the year preceding the outbreak of the Spanish War,” Roosevelt intoned, “I was Assistant Secretary of the Navy.”124 Eleven more times before his stenographer reached the end of her first page, he proudly repeated the words I, my, me.